Images for Orchestra

These Images are Debussy’s last concerthall orchestral works, followed only by Jeux, which was designed for dancing. They began as piano music, however—a third installment in Debussy’s sets of Images for piano. Debussy planned them in 1905, the same year he completed La mer and the second set of piano Images. His original idea was to compose this new set for two pianos; he even proposed titles to Jacques Durand, his publisher: Gigues tristes, Ibéria, and Valses—portraits in sound of three different countries.

But Debussy eventually changed his mind about two of his titles and one of his subjects—leaving, as it were, the waltz idea to Ravel—and decided to score the pieces not for two pianos but for large orchestra. (The 1905 piano Images had already required three staves on each page to accommodate the rich textures and complexity of Debussy’s ideas.) In the end, it would be another eight years before these Images were finished and played together.

Debussy’s new project began well enough; in a letter to Durand dated July 7, 1906, he said that Ibéria would be finished “next week” and that the other two would follow by the end of the month. But the next year, when none of them were done, he attempted to explain to Durand why the Images were such slow going:

I’m trying to write “something different”—realities, in a manner of speaking—what imbeciles call “impressionism,” a term employed with the utmost inaccuracy, especially by art critics, who use it as a label to stick on Turner, the finest creator of mystery in the whole of art!

With important, groundbreaking works such as La mer and Pelleas and Melisande behind him, and with these Images still on the drafting table, Debussy was struggling to articulate—both to understand and to define—the continually evolving “newness” of his work. He wrote to Durand that same year: “I feel more and more that music, by its very essence, is not something

COMPOSED

Gigues: 1909–12

Rondes de printemps: 1905–09

Ibéria: 1908–09

FIRST PERFORMANCE

Gigues: January 26, 1913, Paris

Rondes de printemps: March 2, 1910, Paris. The composer conducting

Ibéria: February 20, 1910, Paris

INSTRUMENTATION

3 flutes and 2 piccolos, 2 oboes, oboe d’amore (in Gigues only) and english horn, 3 clarinets and bass clarinet (in Gigues only), three bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba (in Ibéria only), timpani, percussion (cymbals, snare drum, xylophone, castanets, tambourine, bells, triangle), 2 harps, celesta, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 35 minutes

from top: Claude Debussy, ca. 1908, as photographed by Gaspard-Félix “Nadar” Tournachon (1820–1910). Atelier Nadar, Paris, France. Gallica Digital Library, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Claude Debussy and Erik Satie (1866–1925) as photographed by Igor Stravinsky (1882–1971) in the library of Debussy’s Paris home, ca. 1910–11. API/Gamma-Rapho Collection via Getty Images

that can flow inside a rigorous, traditional form. It consists of colors and of rhythmicized time.”

Of the three pieces, only Ibéria was composed relatively quickly and without serious interruption or flagging interest. It was finished on Christmas Day 1908, and, although the other two pieces were completed in short score within a matter of days, neither one reached its final form for many months. For one thing, Debussy got sidetracked by the idea of turning Poe’s The Fall of the House of Usher into an opera. (He worked on it off and on until he died.) But this was also an unsettled and difficult time for Debussy—his productivity was compromised by the messy details of divorce and remarriage, and by the first symptoms of the colon cancer that would later kill him. In 1908–09, Debussy posed for the Parisian photographer Nadar (the Richard Avedon or Annie Liebovitz of the day), who had captured all the reigning celebrities from Rossini to Delacroix. Debussy wore an expensive but ill-fitting suit, and as his close friend René Peter noted, “Our Claude, still so young and eager, has taken on a sort of patina and no longer looks himself.” That same year, when the first French biography of the composer was published, Debussy seemed uncomfortable with the attention (“I am not sure of being absolutely all that you say I am,” he wrote to the author, Louis Laloy).

Eventually Debussy finished the remaining Images, though not without effort and growing apathy—Léon Vallas, the composer’s biographer, was the first to claim that the orchestration of Gigues was completed by André Caplet. Of the three pieces, premiered piecemeal, only Ibéria enjoyed an enthusiastic reception. The other two have never achieved the popularity of Ibéria, and the set as a whole is not regularly performed. Still, from the beginning, these Images have had important champions—Gustav Mahler gave the U.S. premieres of Rondes de printemps and Ibéria (in 1910 and 1911, respectively) with the New York Philharmonic, and Frederick Stock led the American premiere of Gigues with the Chicago Symphony in November 1914, less than two years after Debussy conducted the first performance in Paris.

Gigues

Debussy originally called this piece Gigues tristes (Sad jigs), and even though he dropped the adjective, the music is haunted and melancholy. As in Rondes de printemps, Debussy quotes folk song to help provide local color—in this case, it’s a Scottish tune mournfully sung by the oboe d’amore, which makes its only appearance in Images for just this purpose. (The bassoons also suggest “The Keel Row.”) What drives the music forward is the interplay of two distinct worlds—the leisurely folk tune

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

November 18 and 19, 1910, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting (Rondes de printemps)

November 10 and 11, 1911, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting (Ibéria)

November 13 and 14, 1914, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting (Gigues) (U.S. premiere)

January 19, 20, and 12, 1967, Orchestra Hall. Jean Martinon conducting

July 13, 1943, Ravinia Festival. Pierre Monteux conducting (Ibéria)

July 14, 1951, Ravinia Festival. Pierre Monteux conducting (Rondes de printemps and Gigues)

July 2, 1981, Ravinia Festival. James Levine conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

April 12 and 13, 2012, Orchestra Hall. Charles Dutoit conducting

March 31, April 1, and 2, 2016, Orchestra Hall. Susanna Mälkki conducting (Gigues)

June 6, 7, 8, and 11, 2024, Orchestra Hall. Stéphane Denève conducting (Ibéria)

July 1, 1990, Ravinia Festival. James Levine conducting

August 5, 2022, Ravinia Festival. Carlos Miguel Prieto conducting (Ibéria)

CSO RECORDING

1957. Fritz Reiner conducting. RCA (Ibéria)

1967. Jean Martinon conducting. CSO (From the Archives, vol. 12: A Tribute to Jean Martinon)

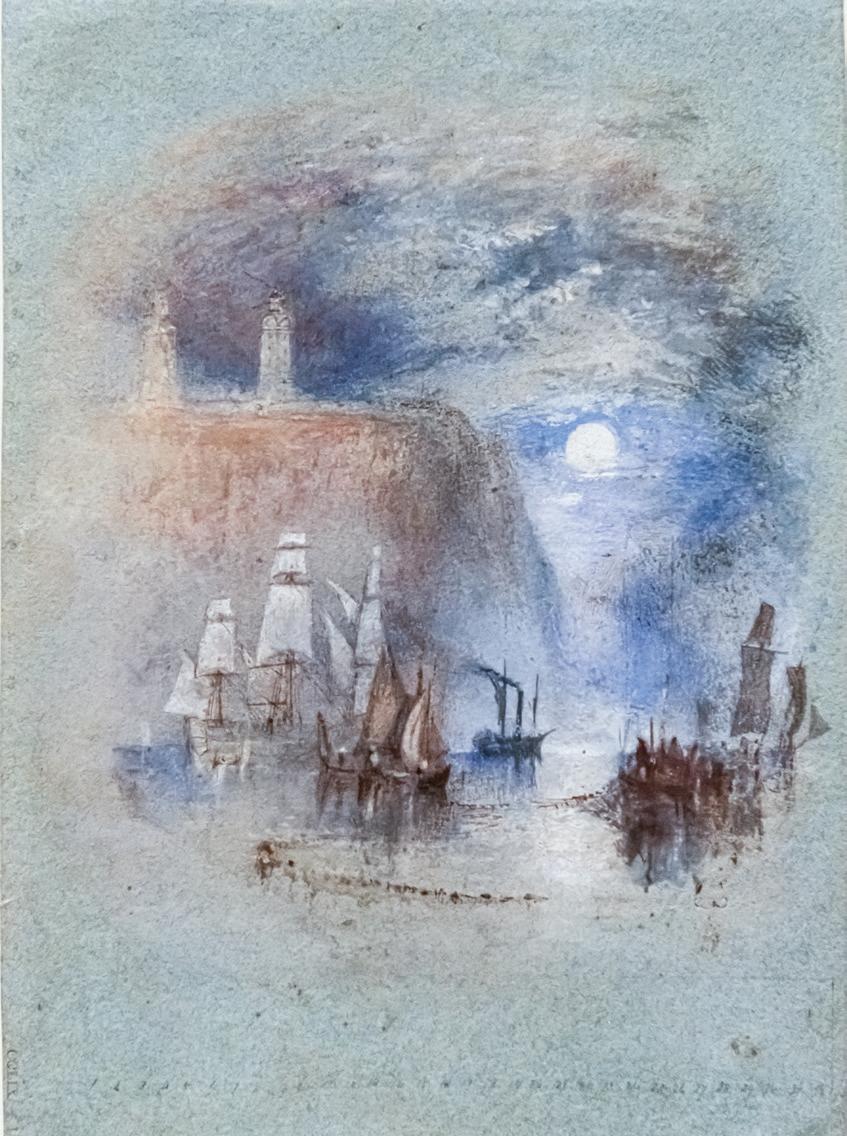

opposite page: Light-Towers of la Hève (Vignette), gouache and watercolor on paper by J.M.W. Turner (1775–1851), ca. 1832. Turner Bequest 1856, Tate Britain Collection, London, England

and a jaunty dotted rhythmic figure. (Caplet, who is credited with carrying out Debussy’s wishes in orchestrating Gigues and who clearly wanted to hear it as program music, detected a battle between “a wounded soul” and a “grotesque marionette.”) They collide, overlap, and intersect, lending the piece a sense of the unpredictable and giving it a complexity quite at odds with its supposed folk roots.

Rondes de printemps (Spring Rounds)

This is the only one of the Images prefaced by a motto: “Long live May! Welcome May with its rustic banner.” Debussy quotes a fifteenth-century Italian poet, but he transplants the setting from Tuscany to his own France. He further underlines the French connection with several passing references to a children’s song, “Nous n’irons plus au bois” (We’ll go to the woods no more), which he had used three times before, most recently in the piano piece Jardins sous la pluie (Gardens in the rain). The song itself is

never quoted, but reflected as if from a distant source, each time from a slightly different angle. The music is limpid and highly fluid—Debussy often writes five beats to the bar, much as in Fêtes, the second of his orchestral nocturnes— and Ravel noted its “vivid charm and exquisite freshness.”

Ibéria

Debussy spent only a single afternoon in Spain. He went to San Sebastián, just over the French border, to catch a bullfight, and was back in Saint-Jean-de-Luz in time for bed. But Debussy was haunted by the spirit of the place—“a country where the roadside stones burn one’s eyes with their brilliant light, where the mule drivers sing so passionately from the depths of their hearts,” as he later wrote. In 1903, he wrote his first Spanish piece, Night in Granada for piano, which Manuel de Falla found to be “nothing less than miraculous when we consider that this music was written by a foreigner guided almost entirely by his visionary genius.” But Ibéria is Debussy’s greatest achievement evoking a Spain he scarcely knew—“truth without authenticity,” as Falla put it.

Ibéria itself is a triptych, with two richly detailed and vigorous movements (the first, In the Streets and Byways, is set against a snappy, virtually ever-present rhythm) framing a voluptuously textured nocturne. All three are remarkably vivid and suggestive, without ever succumbing to tone painting. Debussy himself saw a watermelon vendor and heard children whistling in the third piece, though he truly grasped its essential quality when he remarked that “it sounds like music that has not been written down—the whole feeling of rising, of people and nature waking.”

Ravel (along with a number of composers including Stravinsky), who was present at the premiere of Ibéria in 1910, was moved to tears by “this novel, delicate, harmonic beauty, this profound musical sensitiveness.” Falla felt that Debussy had perfectly re-created his afternoon in San Sebastián—“the light in the bullring, particularly the violent contrast between the

one half of the ring flooded with sunlight and the other half deep in shade.” But Debussy’s accomplishment, despite the clarity of his memory and his powers of evocation, lies much deeper, in the substance of the music itself.

Debussy makes free use of local color, calling for tambourine and castanets and borrowing the rhythms and melodic ideas of Spanish folk music. But his imaginative and thoroughly individual treatment of the material recalls what he himself said of Albéniz: “He does not exactly quote folk tunes, but he is so imbued with them and has heard so many that they have passed into his music and become impossible to distinguish

GABRIELLA SMITH

Born December 26, 1991; Berkeley, California

from his own inventions.” The middle movement, the Fragrance of Night, suggesting the sensuousness of a southern night, is the most subtly Spanish of the three pieces, with its fluid melodies freely unfolding over a languid habanera rhythm. Debussy himself was particularly proud of the way he moves from that music to the third movement, Morning of the Festival Day, allowing the sounds of the day to gradually overtake the night—not the blaring dawn of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung and Strauss’s Zarathustra, but the elusive moment of awakening we know from the paintings by the great British painter J.M.W. Turner he so loved.

Lost Coast, Concerto for Cello and Orchestra

On her website, Gabriella Smith says she grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area “playing and writing music, hiking, backpacking, and volunteering on a songbird research project.” It’s an unconventional resumé, but it says a lot about the sources of Smith’s creativity and the kinds of music she writes. Her first orchestral commission, Tumblebird Contrails, in 2014, was inspired by listening to the “hallucinatory sounds” of the Pacific as she sat in the sand at the edge of the ocean at Point Reyes along the Marin County coast, which is also the site of the bird-banding station where she volunteered for five years, beginning at the age of twelve. By then, she had already begun to study piano and violin and to secretly write music of her own. Smith’s passion for nature and for music did not intersect until she began to study at the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia. “I was so homesick,” she later told the New York Times, “that it sort of forced me to reckon with not only who I was as a composer, but as a person. I infused all that into the music, and that’s when my music started to sound like me.” The composer John Adams, who became something of a mentor for Smith, has said that the way her sensitivity to

COMPOSED

2023, revised 2024

FIRST PERFORMANCE

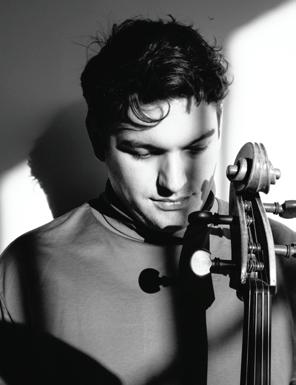

May 25, 2023; Los Angeles, California. Gabriel Cabezas as soloist

INSTRUMENTATION

solo cello (amplified), 2 flutes (2nd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes, 2 clarinets (2nd doubling bass clarinet), 2 bassoons, 2 horns, 2 trumpets, 2 trombones, percussion, strings

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME 26 minutes

These are the first Chicago Symphony Orchestra performances.

this page: Gabriella Smith, photo by Kate Smith

opposite page: Gabriella Smith and Gabriel Cabezas perform at the Philharmonie de Paris, 2022. Photo by Benjamin Millepied

the natural world inhabits her music has its roots as far back as Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony.

Smith met Gabriel Cabezas on her first day at Curtis, and they quickly became friends. In 2014 she wrote an early version of Lost Coast for him, for cello solo with electronics. The next year, it was reworked as a concerto, and over the following decade it has gone through many iterations. (One version, which layers Cabezas’s playing with Smith’s singing, was recorded in 2021.) As it grew into the concerto that is performed this week, much of its transformation was inspired by Cabezas himself. In sections that are improved, Smith admits, he is in fact her co-composer. “I always like to think about my music as being for a person rather than an instrument,” Smith has said. “It’s for a person who happens to play that instrument rather than the instrument.”

like a bad-but-extremelyenthusiastic fiddler”).

Lost Coast is part of Smith’s growing catalog of works devoted to the issues of our environment and climate change. Keep Going (2023), written for the Kronos Quartet’s fiftieth anniversary, weaves music for amplified string quartet and electronics with narratives by people working on climate solutions. Smith’s reach has become global: In 2023

Esa-Pekka Salonen led Tumblebird Contrails in the Nobel Prize Concert that honored, among others, the Norwegian writer Jon Fosse, whose works “give voice to the unsayable.”

Gabriella Smith on Lost Coast

LAs her title, Lost Coast, implies, Smith is deeply troubled by environmental destruction. The score, in each of its variants, suggests the magnificent California landscape—its beauty, wildness, and uncertain future. From the opening, for cello alone—ppp and continuously growing, with “very light bow pressure, airy, almost pitchless”—Smith’s musical language commands an astonishingly wide array of sounds. The large percussion battery includes cymbals “with white-noise oceanic sound” and an assortment of metal objects of varying timbres and resonances (including, for example, kitchen pans and utensils, machine parts, water bottles, tin cans). It is a sound world that could, in fact, only be duplicated by the natural world itself. Yet for all its wildness and nontraditional techniques, Lost Coast is governed throughout by Smith’s impeccable and nuanced instructions, like the explicit directions of a seasoned theater director (“even more bow pressure,” she tells the strings at one point, “scratchy, rough, raw, raucous, wild,

ost Coast is inspired by a five-day solo backpacking trip I took on the Lost Coast Trail, a surprisingly remote section of northern California coastline. It’s a wild and dramatic landscape of jagged precipices and stomach-turning drops overlooking ferocious, pounding surf. The area is so rugged, the Pacific Coast Highway had to be diverted 100 miles inland because the land was too riddled with cliffs to build on. Trail conditions were dubious, with washouts and sections so overgrown I had to fight my way through the coastal scrub. Some sections were so steep I had to grab hold of the coyote bush to pull myself up short slopes. In five days, I only encountered two other people on the trail.

With the climate crisis becoming an increasing part of our daily lives and little to no progress slowing the emissions of greenhouse gases, the title Lost Coast has taken on a secondary meaning for me. The piece is a raw emotional expression of the grief, loss, rage, and fear experienced as a result of climate change—as well as the joy, beauty, and wonder I have felt in the world’s last wild places and the joy and hope in getting to work on climate solutions.

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

La mer (Three Symphonic Sketches)

Although Debussy’s parents once planned for him to become a sailor, La mer, subtitled Three Symphonic Sketches, proved to be his greatest seafaring adventure. Debussy’s childhood summers at Cannes left him with vivid memories of the sea, worth more than reality, as he put it at the time he was composing La mer some thirty years later.

As an adult, Debussy seldom got his feet wet, preferring the seascapes available in painting and literature; La mer was written in the mountains, where his “old friend the sea, always innumerable and beautiful,” was no closer than a memory.

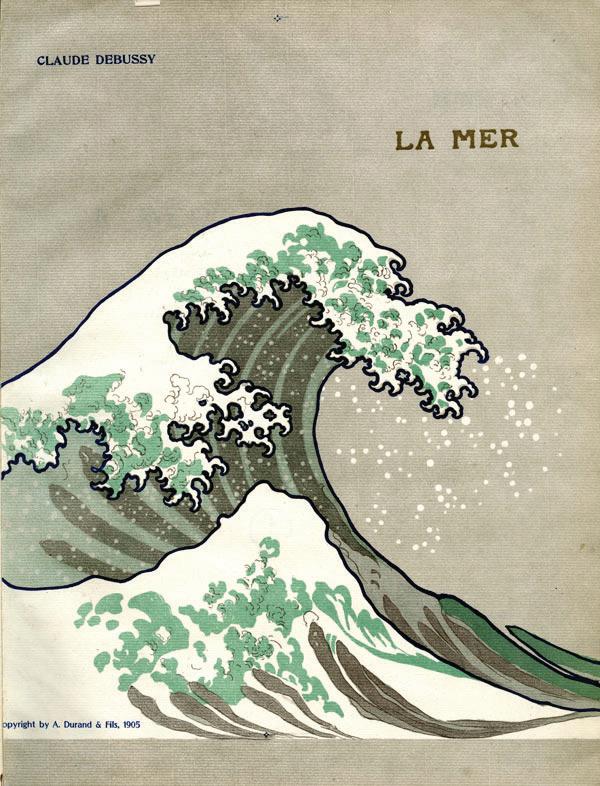

Like J.M.W. Turner, who stared at the sea for hours and then went inside to paint, Debussy worked from memory, occasionally turning for inspiration to a few other sources. He first mentioned his new work in a letter dated September 12, 1903; the title he proposed for the first of the three symphonic sketches, “Calm Sea around the Sanguinary Islands,” was borrowed from a short story by Camille Mauclair published during the 1890s. When Debussy’s own score was printed, he insisted that the cover include a detail from The Great Wave off Kanagawa, the most celebrated print by the Japanese artist Hokusai, then enormously popular in France. (Its popularity has only grown: in November the woodblock print sold at a Sotheby’s auction for $2.8 million, a record-breaking price three times its high estimate.)

COMPOSED 1903–March 1905

FIRST PERFORMANCE

October 15, 1905; Paris, France

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes and piccolo, 2 oboes and english horn, 2 clarinets, 3 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets and 2 cornets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (cymbals, tam-tam, triangle, glockenspiel, bass drum), 2 harps, celesta, strings

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME 26 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

January 29 and 30, 1909, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting

July 8, 1937, Ravinia Festival. Ernest Ansermet conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

June 1, 2, 3, and 6, 2023, Orchestra Hall. David Afkham conducting August 9, 2025, Ravinia Festival. Lidiya Yankovskaya conducting

CSO RECORDINGS

1960. Fritz Reiner conducting. RCA

1976. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

1978. Erich Leinsdorf conducting.

CSO (From the Archives, vol. 5: Guests in the House)

1991. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

2000. Daniel Barenboim conducting. Teldec

from top: Claude Debussy, ca. 1890–1910, Atelier Nadar (studio of GaspardFélix “Nadar” Tournachon). From Reference Album of Atelier Nadar, vol. 13. Gallica Digital Library, Bibliothèque nationale de France | Cover of the first edition of Debussy’s full score of La mer, published by Durand in 1905 and bearing a detail of the famous reproduction of The Great Wave off Kanagawa, a woodcut by Katsushika Hokusai (1760–1849), created ca. 1831

2001. Daniel Barenboim conducting. EuroArts (video)

We also know that Debussy greatly admired Turner’s work. His richly atmospheric seascapes recorded the daily weather, the time of day, and even the most fleeting effects of wind and light in ways utterly new to painting, and they spoke directly to Debussy. (In 1902, when Debussy went to London, where he saw a number of Turner’s paintings, he enjoyed the trip but hated actually crossing the channel.) The name Debussy finally gave to the first section of La mer, From Dawn to Noon on the Sea, might easily be that of a painting by Turner made sixty years earlier, for the two shared not only a love of subject but also of long, specific, evocative titles.

There’s something in Debussy’s first symphonic sketch very like a Turner painting of the sun rising over the sea. They both reveal, in their vastly different media, those magical moments when sunlight begins to glow in near darkness, when familiar objects emerge from the shadows. This was Turner’s favorite image—he even owned several houses from which he could watch, with undying fascination, the sun pierce the line separating sea and sky. Debussy’s achievement, though decades later than Turner’s, is no less radical, for it uses familiar language in truly fresh ways. From Dawn to Noon on the Sea can’t be heard as traditional program music, for it doesn’t tell a tale along a standard timeline (although Debussy’s friend Eric Satie reported that he “particularly liked the bit at a quarter to eleven”). Nor can it be read as a piece of symphonic discourse, for it is organized without regard for conventional theme and development. Debussy’s audiences, like Turner’s before him, were baffled by a work that takes as its subject matter color, texture, and nuance.

Lemminkäinen the Disruptor

Debussy’s second sketch, too, is all suggestion and shimmering surface, fascinated with sound for its own sake. Melodic line, rhythmic regularity, and the use of standard harmonic progressions are all shattered, gently but decisively, by the fluid play of the waves. The final Dialogue of the Wind and the Sea (another title so like Turner’s) captures the violence of two elements, air and water, as they collide. At the end, the sun breaks through the clouds. La mer repeatedly resists traditional analysis. “We must agree,” Debussy writes, “that the beauty of a work of art will always remain a mystery, in other words, we can never be absolutely sure ‘how it’s made’.”

La mer was controversial even during rehearsals, when, as Debussy told Stravinsky, the violinists tied handkerchiefs to the tips of their bows in protest. The response at the premiere was mixed, though largely unfriendly. It is hard now to separate the reaction to this novel and challenging music from the current Parisian view of the composer himself, for during the two years he worked on La mer, Debussy moved in with Emma Bardac, the wife of a local banker, leaving behind his wife Lily, who attempted suicide. Two weeks after the premiere of La mer, Bardac gave birth to Debussy’s child, Claude-Emma, later known as Chou-Chou. Debussy married Emma Bardac on January 20, 1908. The night before, he conducted an orchestra for the first time in public, in a program that included La mer. This time, it was a spectacular success, though many of his friends still wouldn’t speak to him.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

Directly after the concert on February 21, join Professor Thomas Dubois for a presentation and audience Q&A about the story and artistic influences of the fabled folk hero Lemminkäinen on Sibelius’s composition. This event is open to all ticket holders and will take place in Grainger Ballroom with limited seating.

SCAN TO LEARN MORE

Let music resound

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association gratefully acknowledges the Helen Zell Contemporary Music Fund for its leadership support of the presentation of contemporary music in the CSO’s 2025–26 season.

Major support is also provided by Sally Mead Hands Foundation, The Irving Harris Foundation, and Lori Julian for the Julian Family Foundation

Sep 25–28

PÉPIN Les Eaux célestes

Oct 3–4

SIMON Fate Now Conquers MUSGRAVE Piccolo Play

Dec 18–20

WIDMANN Con brio CHIN subito con forza

Feb 5–7

SMITH Lost Coast

Feb 12–15

THOMPSON To See the Sky

Apr 2–4

TÜÜR Prophecy

May 7–9

LIEBERSON Neruda Songs

May 21–23

CLYNE Sound and Fury

FORMER MEAD COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE

June 18–21

MONTGOMERY Banner

FORMER MEAD COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE

Contemporary music remains a vital thread in the CSO’s artistic legacy, and this generous support ensures that bold, innovative repertoire continues to resonate with audiences today. We are proud to carry forward this tradition by featuring compelling new works throughout the 2025–26 concert season.

Ksenija Sidorova (Apr 2–4)

Edward Gardner (May 7–9)

Joyce DiDonato (May 7–9)

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra—consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 135th season in 2025–26. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027. In July 2025, Donald Palumbo became the third director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is the CSO’s Artist-in-Residence for the 2025–26 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007— have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

Civic Orchestra of Chicago

Ken-David Masur, Conductor

Musicians from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Students from the Percussion Scholarship Program

Jeremy Liu, piano

Ana Everling and Leah Dexter, vocals and more

Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Joyce DiDonato Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler

Chair, endowed by an

anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor*

Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C.

Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu*

Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Gabriela Lara

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin

Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky §

Wendy Koons Meir

Ronald Satkiewicz ‡

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith

Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Paolo Dara

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

CELLOS

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen

Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak §

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Olivia Jakyoung Huh

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton

Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton

Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson § Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M.

Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer

Assistant Principal

The Gilchrist Foundation, Jocelyn Gilchrist Chair

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh

Assistant Principal

The Governing

Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman

Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich ‡

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Timothy Higgins Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin

Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority. ‡ On sabbatical § On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. The Louise H. Benton Wagner chair is currently unoccupied.

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos

Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Ariel Seunghyun Lee Violin

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.

Discover more about the musicians, concerts, and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association online, at cso.org.

Find articles and program notes, listen to CSOradio, and watch CSOtv at Experience CSO.

cso.org/experience

Get involved with our many volunteer and affiliate groups.

cso.org/getinvolved

Connect with us on social @chicagosymphony

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Board of Trustees

OFFICERS

Mary Louise Gorno Chair

Chester A. Gougis Vice Chair

Steven Shebik Vice Chair

Helen Zell Vice Chair

Renée Metcalf Treasurer

Jeff Alexander President

Kristine Stassen Secretary of the Board

Stacie M. Frank Assistant Treasurer

Dale Hedding Vice President for Development

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Administration

SENIOR LEADERSHIP

Jeff Alexander President

Stacie M. Frank Vice President & Chief Financial Officer, Finance and Administration

Dale Hedding Vice President, Development

Ryan Lewis Vice President, Sales and Marketing

Vanessa Moss Vice President, Orchestra and Building Operations

Cristina Rocca Vice President, Artistic Administration

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

Eileen Chambers Director, Institutional Communications

Jonathan McCormick Managing Director, Negaunee Music Institute at the CSO

Visit cso.org/csoa to view a complete listing of the CSOA Board of Trustees and Administration.

For complete listings of our generous supporters, please visit the Richard and Helen Thomas Donor Gallery.

cso.org/donorgallery