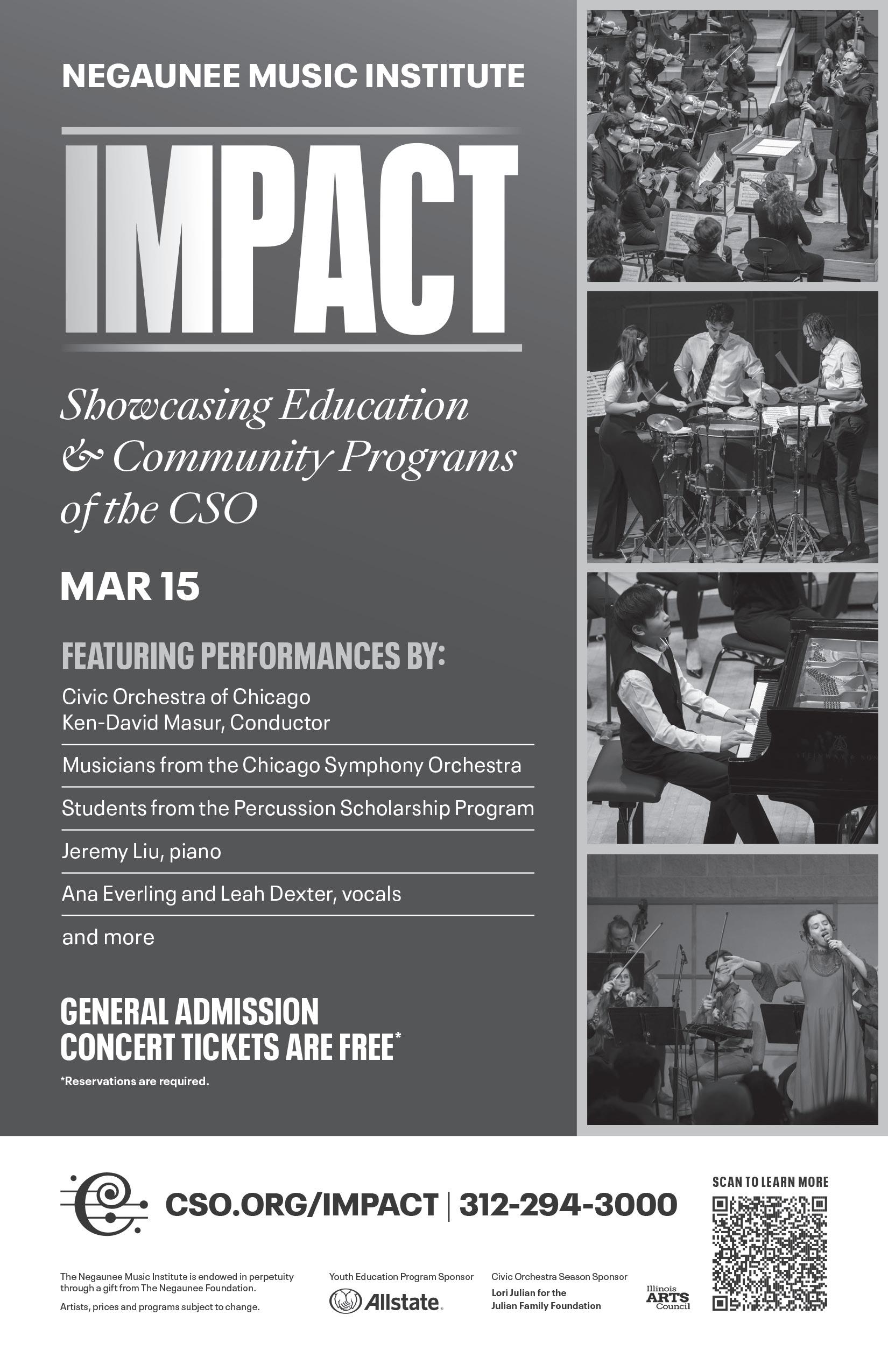

CIVIC PLAYS ESMAIL, ELGAR & LUTOSŁAWSKI

FEB 2 | 7:30

The 2025–26 Civic Orchestra season is generously sponsored by Lori Julian for the Julian Family Foundation, which also provides major funding for the Civic Fellowship program.

ONE HUNDRED SEVENTH SEASON

CIVIC ORCHESTRA OF CHICAGO

KEN-DAVID MASUR Principal Conductor

The Robert Kohl and Clark Pellett Principal Conductor Chair

Monday, February 2, 2026, at 7:30

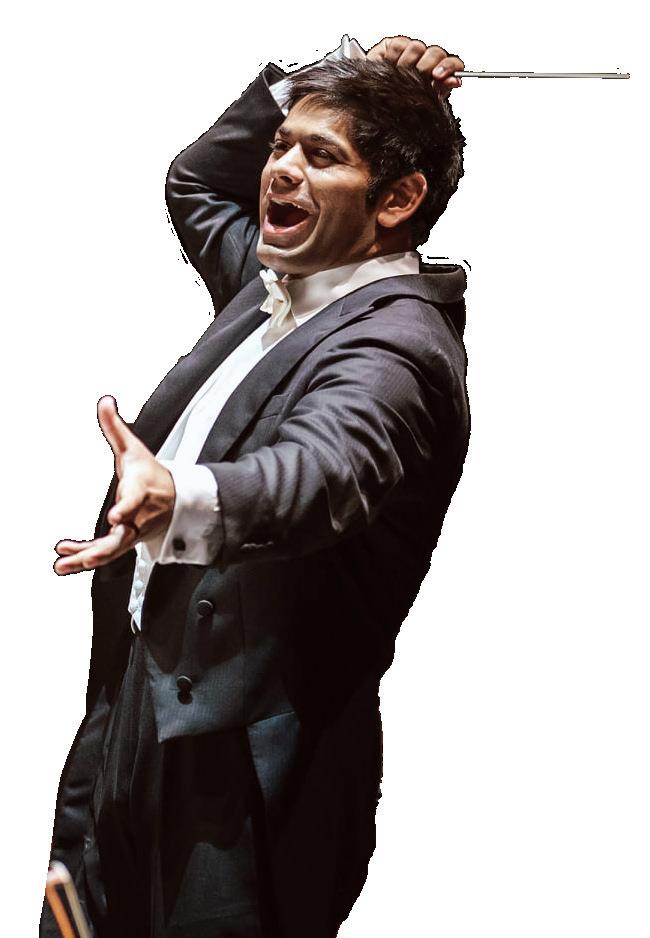

Alpesh Chauhan Conductor

ESMAIL Black Iris

ELGAR In the South (Alassio), Op. 50

INTERMISSION

LUTOSŁAWSKI Concerto for Orchestra Intrada

Capriccio, Notturno, and Arioso Passacaglia, Toccata, and Chorale

The 2025–26 Civic Orchestra season is generously sponsored by Lori Julian for the Julian Family Foundation, which also provides major funding for the Civic Fellowship program.

The Civic Orchestra of Chicago acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

COMMENTS

REENA ESMAIL

Born February 11, 1983; Chicago, Illinois

Black Iris

COMPOSED 2017

FIRST PERFORMANCE

March 11, 2018; Wentz Auditorium, Naperville, Illinois. Chicago Sinfonietta, Mei-Ann Chen conducting

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes and piccolo, 2 oboes and english horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, triangle, snare drum, cymbals, glockenspiel, vibraphone, orchestral chimes, marimba, celesta, harp, piano, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME

13 minutes

Indian American composer Reena Esmail works between the worlds of Indian and Western classical music, bringing communities together through the creation of equitable musical spaces.

Esmail’s life and music were profiled on season 3 of PBS’s Great Performances series, “Now Hear This,” as well as on the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s podcast Frame of Mind.

Esmail divides her attention evenly between orchestral, chamber, and choral work. She has written

above: Reena Esmail, photo courtesy of the artist

commissions for ensembles including the Los Angeles Master Chorale, Seattle Symphony, Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, and Kronos Quartet, and her music has been featured on multiple Grammy-nominated albums, including The Singing Guitar by Conspirare, Bruits by Imani Winds, and Healing Modes by Brooklyn Rider. Many of her choral works are published by Oxford University Press.

Esmail was the Los Angeles Master Chorale’s 2020–25 Swan Family artist-in-residence and was Seattle Symphony’s 2020–21 composer-inresidence. She has been in residence with the Tanglewood Music Center and Spoleto Festival. She holds awards and fellowships from the United States Artists, the S&R Foundation, American Academy of Arts and Letters, and the Kennedy Center.

Esmail holds degrees in composition from the Juilliard School and the Yale School of Music. Her primary teachers have included Susan Botti, Aaron Jay Kernis, Christopher Theofanidis, Christopher Rouse, and Samuel Adler. She received a Fulbright-Nehru grant to study Hindustani music in India. Her doctoral thesis, titled “Finding Common Ground: Uniting Practices in Hindustani and Western Art

Musicians,” explores the methods and challenges of the collaborative process between Hindustani musicians and Western composers.

Esmail is currently an artistic director of Shastra, a non-profit organization that promotes cross-cultural music connecting music traditions of India and the West.

Reena Esmail on Black Iris

MeToo bears the title of the social movement that has been exploding across our country during the time I was writing this piece. The movement, created by Tarana Burke as a way to provide safe spaces for young women of color, has grown into a movement that has allowed so many women to speak out, contextualize one another’s experiences, and begin to heal.

I always get asked why there aren’t more women composers. This piece is one response—of many hundreds of responses—to that question. So many of us decide to become composers when we are young women because we fall deeply in love with individual pieces of music. We listen to them incessantly, we memorize every note of them, we live our lives through the lens of that music. And then, at some point, for some of us, as we engage with that music, something devastating happens to us—often by the very person who has introduced

us to that music. We hate ourselves, we blame ourselves, we bury it deep within our psyche—until we hear that piece of music again. It could be at a concert, it could be in a theory class, it could be on the radio. We are powerless to fend off that tidal wave of sensory memory. The very music we once loved becomes a trigger that slowly destroys our love for our art. Of course, I’m speaking about myself, but I’m also speaking about so many other women I know. That experience is what this piece is about.

I was so filled with rage while I was writing this work. The rage of seeing the injustices that plagued even the strongest, most powerful women among us, the rage of having to relive the worst moments of my own life over and over again, every time I checked Facebook or turned on the news. The rage that, as women, some of the strongest bonds we share are forged from the most devastating and corrosive experiences.

Every day, even as my rage simmers, I have to ask: what is the endgame here? What does a healthy society look like? And how can we put systems in place that truly allow men to address these underlying issues, so that we can create stronger bonds with one another and build stronger communities with higher standards of accountability to each other? I look forward to imagining and creating that world together.

—reenaesmail.com

COMMENTS

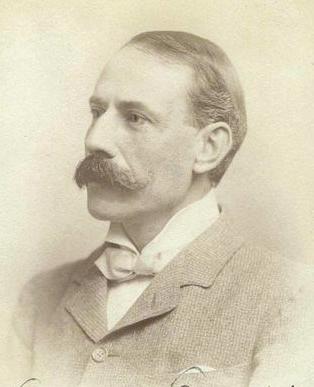

EDWARD ELGAR

Born June 2, 1857; Broadheath, near Worcester, England

Died February 23, 1934; Worcester, England

In the South (Alassio), Op. 50

COMPOSED

1903–04

FIRST PERFORMANCE

March 16, 1904; London. The composer conducting

INSTRUMENTATION

3 flutes and piccolo, 2 oboes and english horn, 2 clarinets and bass clarinet, 2 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, bass drum, cymbals, snare drum, triangle, glockenspiel, 2 harps, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME

22 minutes

Elgar had gone to Italy in December 1903 not to escape the damp and cold of an English winter, but to regain his strength and inspiration after the exhausting work of finishing The Apostles and to begin his first symphony. He failed on all counts. Several days into their stay in Alassio, his wife Alice wrote in her diary, “Still cold and grey and windy—E. and A. much depressed at these conditions and wondering if they will not pack up and go home. E. feeling no inspiration for writing.” Edward himself wrote to his dear friend Alfred Jaeger (immortalized in the magnificent and moving

“Nimrod” music in the Enigma Variations): “This visit has been, is, artistically a complete failure, and I can do nothing. The symphony will not be written in this sunny (?) land.”

But the essence of Italian life affected Elgar, despite the cold and the gales and swarms of mosquitoes as annoying as the tourist crowds. In Alassio, he began a concert overture, in place of the promised symphony, that is perhaps his sunniest and most energized work. It depicts the Italian holiday that largely eluded him, and it is music that Elgar never would have written at home in England, for even a dispiriting stay in Italy offered glimpses of life’s greatest pleasures. In his manuscript, he wrote this passage from Tennyson’s The Daisy:

What hours were thine and mine

In lands of palm and southern pine

In lands of palm, of orange blossom

Of olive, aloe, and maise and vine

And from Byron’s Childe Harold: . . . a land

Which was the mightiest in its old command

And is the loveliest . . .

Wherein were cast . . . . . . the men of Rome!

Thou art the garden of the world.

Although Elgar called In the South a concert overture, it’s really a tone poem—his largest orchestral movement at the time—of weighty dimensions and electric colors. Elgar may have sidestepped that term to avoid comparison with the new tone poems by Richard Strauss (at the time of the premiere, he asked that the program notes not mention Strauss’s name), for much about Elgar’s overture recalls the style, substance, and sheer orchestral splendor of Strauss. These two composers were kindred spirits in many ways, and their artistic outlooks were never more closely aligned than in the early years of the twentieth century. When Strauss heard a performance of Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius in 1902, he proposed a toast to “the first English progressivist, Meister Edward Elgar” and remained Elgar’s friend for life. In the South begins with a rapid unfurling of a large orchestral chord, very like the opening of Strauss’s Don Juan (which Elgar admired), followed by the kind of dancing horns Strauss had already made famous.

The precise idea for In the South came to Elgar during an afternoon stroll near Alassio. “I was by the side of an old Roman way. A peasant stood by an old ruin, and in a flash it all came to me—the conflict of armies in that very spot long ago, where now I stood—the contrast of the ruin and the shepherd.” In a letter to Percy Pitt, who wrote the program

note for the premiere, Elgar marked his initial theme “Joy of Life (wine and macaroni),” but, in fact, it’s an idea he had sketched several years before, depicting Dan, a friend’s bulldog, “triumphant (after a fight).” (Dan is officially memorialized in the eleventh of the Enigma Variations, when he falls into the river Wye, paddles upstream, and reaches the shore with a victorious bark.) The rest of In the South, however, leaves England far behind, beginning with the reflective shepherd’s music that soon follows, with, as the composer told Pitt, “romance creeping into the picture.” Elgar lingers in this relaxed and genial mood for some time until the music moves into a forceful and determined passage marked grandioso. There, he writes two more lines from Tennyson into his manuscript:

What Roman strength Turbia show’d In ruin, by the mountain road.

Here, and in the uncharacteristically dissonant pages that follow, Elgar recalls “the strife and wars, the ‘drums and tramplings’ of a later time.” This gives way to a delicate canto populare, first sung by the solo viola—an unidentified popular song that Elgar eventually confessed he had written himself. He later turned this lovely music into a real song, taking words from a poem by Shelley, “An Ariette for Music” (he begins at the line, “As the moon’s soft splendour”). With this little song,

opposite page: Edward Elgar, portrait, ca. 1904, Russell & Sons Photographers, London, England

COMMENTS

titled “In Moonlight,” Elgar returns to the shores of the Mediterranean, for it was there, on the curving coast not far from Alassio, that Shelley spent the last months of his short life. When Henry James made his pilgrimage to Shelley’s house, he wrote, “I can fancy

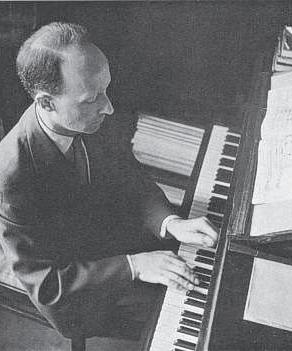

WITOLD LUTOSŁAWSKI

Born January 25, 1913; Warsaw, Poland

Died February 7, 1994; Warsaw, Poland

Concerto for Orchestra

COMPOSED

1950–54

FIRST PERFORMANCE

November 26, 1954; Warsaw, Poland

INSTRUMENTATION

3 flutes with 2 piccolos, 3 oboes with english horn, 3 clarinets with bass clarinet, 3 bassoons with contrabassoon, 4 horns, 4 trumpets, 4 trombones, tuba, timpani, snare drum, side drums, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals, tam-tam, tambourine, xylophone, bells, celesta, 2 harps, piano, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME

30 minutes

Witold Lutosławski’s was the first important concerto for orchestra composed in the shadow of Bartók’s great work, but that appears to have inspired rather than intimidated him—Bartók served as

a great lyric poet sitting on the terrace of a warm evening and feeling very far from England.” Elgar’s own final pages say the same thing, in music of warmly melodic and life-loving exuberance.

—Phillip Huscher

a touchstone, a reminder of what could be done within a certain style and with a specific aim. For Lutosławski, as for Bartók, the concerto for orchestra was intended as a reflection of the unprecedented virtuosity of the modern orchestra. The hallmarks of Bartók’s masterwork are here as well—the arch form of the first movement; the broad chorale of the last; a certain similarity of gesture, tone, and language that’s easy to hear, although less simple to pinpoint in the score—and yet Lutosławski’s score is entirely his own. (Lutosławski’s Musique funèbre, written four years later, was dedicated to Bartók’s memory.) Still another composer links Bartók’s and Lutosławski’s concertos. In the fourth movement of his work, Bartók parodies the battle music from Dmitri Shostakovich’s Leningrad Symphony. In the toccata section of his finale, Lutosławski inscribes Shostakovich’s well-known musical

monogram—DSCH, or D, E-flat, C, B-natural, as translated into musical notation. But the references are quite different. Bartók intended a sly comment about artistic merit. For Lutosławski, Shostakovich represented a major composer responding through his music to a political crisis—a concern he understood only too well. In 1948 Lutosławski’s First Symphony was banned by the Polish government; the music written during the next years, culminating in this Concerto for Orchestra, was his response. In 1988 Lutosławski talked with Allan Kozinn of the New York Times about this period:

The government stopped interfering with our musical life very early, probably because they decided that music is not an offensive art. It’s not semantic. It doesn’t carry meaning in the same way literature, poetry, theater, and film do. So they are not interested in it. I have never felt any pressure to write a certain way. But after my First Symphony, I realized that I was writing in a style that was not leading me anywhere. So I decided to begin again—to work from scratch on my sound language. Obviously, I could not immediately begin writing concert works, so I wrote functional music—children’s music, easy piano pieces, and small-ensemble works. I did it with pleasure, because Poland was devastated after the war, and this educational music was necessary.

opposite page: Witold Lutosławski, ca. 1952–53

Eventually, I developed a style that combined functional music with elements of folk music, and occasionally with nontonal counterpoints and harmonies.

The Concerto for Orchestra was the climax of this nationalistic, folk-based music—a work that not only spoke to politically defeated people at the time, but also continues to touch musicians of many lands today. Shortly after writing the concerto, Lutosławski changed his sound language again. In 1960 he heard part of a radio broadcast of John Cage’s Piano Concerto, a work that leaves much to chance and is, therefore, different at every performance. Lutosławski remembered that “those few minutes were to change my life decisively. It was a strange moment . . . I suddenly realized that I could compose music differently from that of my past. . . .”

And so the rest of his career, including the Third Symphony commissioned by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, was spent exploring and perfecting this new language, one that is based on the juxtaposition of ad-lib passages with strictly controlled music.

In an interview given in 1973, Lutosławski expressed surprise at the continuing interest in his early Concerto for Orchestra, calling it “the only serious piece among the folk-inspired works” of the period immediately following the war. On another occasion, he said, “I wrote as I was able, since I

could not yet write as I wished.” His dismissive attitude recalls Bartók, who kept reassigning opus numbers to his scores, each time excluding the earliest works that no longer pleased him.

In this respect, the concertos for orchestra by Bartók and Lutosławski differ. Bartók’s came very late in his career—it is, technically, the last music he finished, although the Third Piano Concerto was nearly complete at his death—and found him at the summit, commanding the language in a way that only years of work and understanding make possible. Lutosławski’s early Concerto for Orchestra in no way suggests the direction his music would take.

Borrowing Bartók’s favored arch form, the first movement begins and ends with imitative writing set against repeated F-sharps—pounding drums in the beginning, the tinkling celesta at the end. (Structurally, the movement is most closely modeled on the opening of Bartók’s Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta.)

Midway, the music reaches several big, engulfing climaxes, punctuated by screaming brass. At least two themes are based on Polish folk songs, although Lutosławski, unlike Bartók, treats them like raw material rather than cultural artifacts.

The middle movement captures something of Bartók’s famous Night Music, although for Lutosławski night is a time of furtive activity rather than mysterious calm. Again, the form is symmetrical, with quickly moving music for strings and winds framing a slower section for brass. This central Arioso, sung first by the trumpets, brings the movement to a terrifying climax. From there, the music flickers and dies—the final bars are a duet for tenor drum and bass drum, ppp.

The harps and double basses quietly launch the finale, eventually stating the passacaglia theme (based on a folk song) that will serve as the foundation for fifteen variations, all carefully dovetailed and growing in intensity and activity until the last, which recedes into silence. Lutosławski then launches a powerful, bustling toccata. The music finally dissolves to reveal a solemn chorale intoned by the winds—the ghost of Bartók again (the resemblance to the chorale in the second movement of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra is clearly intentional)—before the music turns lively and sweeps to its conclusion.

—Phillip Huscher

Phillip Huscher is the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

PROFILES

Alpesh Chauhan Conductor

British conductor Alpesh Chauhan is principal guest conductor of the Düsseldorf Symphony Orchestra, music director of Birmingham Opera Company, and principal conductor and musical advisor for the National Youth Orchestra of Great Britain.

He works regularly with the City of Birmingham Symphony, Hallé Orchestra, Adelaide Symphony, Oslo Philharmonic, and the Antwerp, Stavanger, Vancouver, and Detroit symphony orchestras.

Recent highlights include appearances with the Los Angeles Philharmonic, National Symphony, Toronto Symphony, Philharmonia, BBC Symphony, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, RAI Torino, and London Philharmonic. Chauhan regularly collaborates with esteemed soloists, including Karen Cargill, Sir Stephen Hough, Hilary Hahn, Johannes Moser, Pablo Ferrández, Benjamin Grosvenor, Pavel Kolesnikov, Simone Lamsma, and Simon Höfele.

Following his debut in 2015, he was appointed principal conductor of the Filarmonica Arturo Toscanini in Parma, a position he held until 2020.

As music director of the Birmingham Opera Company, Chauhan champions a unique approach to bringing opera to the wider community of

Birmingham, following his mentorship by the company’s founder, the late Sir Graham Vick.

Alpesh Chauhan is widely renowned for his interpretations of late romantic and twentieth-century music. Repertoire highlights of the season include Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde and Bruckner’s late symphonies, coinciding with the composer’s anniversary year.

An advocate of music education for young people, Chauhan is a patron of Young Sounds UK, a charity supporting talented young people from disadvantaged backgrounds on their musical journeys. He has collaborated with ensembles including the National Youth Orchestra of Scotland and symphony orchestras of the UK conservatoires. He was the conductor of the 2015 BBC Ten Pieces film, which brought the world of classical music into secondary schools across the United Kingdom and received a distinguished BAFTA Award.

Born in Birmingham, Alpesh Chauhan studied cello at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester before continuing at the RNCM to pursue the prestigious master’s conducting course. He was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in the 2022 New Year’s Honors of Queen Elizabeth II for Services to the Arts and was conferred an Honorary Fellow of the RNCM in 2024. In 2022 he received the conductor award from the Italian National Association of Music Critics for Best Conductor.

PHOTO BY BENJAMIN EALOVEGA

Civic Orchestra of Chicago

The Civic Orchestra of Chicago is a training program of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s Negaunee Music Institute that prepares young professionals for careers in orchestral music. It was founded during the 1919–20 season by Frederick Stock, the CSO’s second music director, as the Civic Music Student Orchestra, and for over a century, its members have gone on to secure positions in orchestras across the world, including over 160 Civic players who have joined the CSO. Each season, Civic members are given numerous performance opportunities and participate in rigorous orchestral training with its principal conductor, Ken-David Masur, distinguished guest conductors, and a faculty of coaches consisting of CSO members. Civic Orchestra musicians develop as exceptional orchestral players and engaged artists, cultivating their ability to succeed in the rapidly evolving music world.

The Civic Orchestra serves the community through its commitment to present free or low-cost concerts of the highest quality at Symphony

Center and in venues across Greater Chicago, including annual concerts at the South Shore Cultural Center and Fourth Presbyterian Church. The Civic Orchestra also performs at the annual Crain-Maling Foundation CSO Young Artists Competition and Chicago Youth in Music Festival. Many Civic concerts can be heard locally on WFMT (98.7 FM), in addition to concert clips and smaller ensemble performances available on CSOtv and YouTube. Civic musicians expand their creative, professional, and artistic boundaries and reach diverse audiences through educational performances at Chicago public schools and a series of chamber concerts at various locations throughout the city.

To further expand its musician training, the Civic Orchestra launched the Civic Fellowship program in the 2013–14 season. Each year, up to twelve Civic members are designated as Civic Fellows and participate in intensive leadership training designed to build and diversify their creative and professional skills. The program’s curriculum has four modules: artistic planning, music education, social justice, and project management. A gift to the Civic Orchestra of Chicago supports the rigorous training that members receive throughout the season, which includes coaching from musicians of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and world-class conductors. Your gift today ensures that the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association will continue to enrich, inspire, and transform lives through music.

Civic Orchestra of Chicago

Ken-David Masur Principal Conductor

The Robert Kohl and Clark Pellett Principal Conductor Chair

VIOLINS

Alba Layana Izurieta

Tricia Park

Kimberly Bill+ Natalie Boberg

Carlos Chacon

Morgan Chan

Jenny Choi*

Kaylin Chung

Naomi Folwick

Pavlo Kyryliuk

June Lee

Oliver Leitner

Mona Mierxiati

Mia Smith

Abigail Yoon

Hobart Shi

Ebedit Fonseca

Maria Paula Bernal

Adam Davis

Alyssa Goh

Charles Hamilton

Evan Harper

Hojung Christina Lee

Lara Madden Hughes

Nelson Mendoza+ Matthew Musachio

Sean Qin

Justine Jing Xin Teo*

Lorena Uquillas

VIOLAS

Darren Carter

Sava Velkoff*

Lucie Boyd

Eugene Chin

Jacob Davis

August DuBeau

Elena Galentas

Roslyn Green+ Matthew Nowlan**

Yat Chun Justin Pou

Teddy Schenkman+

Mason Spencer*

CELLOS

David Caplan

Nick Reeves

Krystian Chiu

Grant Estes

Miquel Fuentes

J Holzen*

Henry Lin

Buianto Lkhasaranov

Ashley Ryoo

Andrew Shinn

BASSES

Jonathon Piccolo

Albert Daschle

Walker Dean

Bennett Norris

Jared Prokop

Tony Sanfilippo Jr.

Alexander Wallack

Hanna Wilson-Smith

FLUTES

Cierra Hall

Daniel Fletcher

Isabel Evernham

PICCOLOS

Isabel Evernham

Cierra Hall

OBOES

Orlando Salazar*

Will Stevens

Guillermo Ulloa

ENGLISH HORN

Guillermo Ulloa

CLARINETS

Henry Lazzaro

Max Reese

Daniel Spielman

BASS CLARINET

Daniel Spielman

BASSOONS

Jason Huang

William George

Hannah Dickerson

Civic Orchestra Fellow **NMI Arts Administration Fellow +Civic Orchestra Alum

CONTRABASSOON

Hannah Dickerson

HORNS

Eden Stargardt*

Erin Harrigan

Micah Northam

Layan Atieh

Emmett Conway

TRUMPETS

Sean-David Whitworth

Abner Wong

Hamed Barbarji*

Maria Merlo

TROMBONES

Dustin Nguyen

Arlo Hollander

Ellie Abbott

BASS TROMBONE

Timothy Warner

TUBA

Chrisjovan Masso

TIMPANI

Kyle Scully

PERCUSSION

Alex Chao

Adriana Harrison

Amy Lee

Cameron Marquez*

Tae McLoughlin

HARPS

Kari Novilla*

Zora Evangeline Dickson

PIANO

Daniel Szefer

CELESTA

Daniel Szefer

Wenlin Cheng

LIBRARIAN

Andrew Wunrow

NEGAUNEE MUSIC INSTITUTE AT THE CSO

The Negaunee Music Institute connects people to the extraordinary musical resources of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Institute programs educate audiences, train young musicians, and serve diverse communities across Chicago and around the world.

Current Negaunee Music Institute programs include an extensive series of CSO School and Family Concerts and open rehearsals; more than seventy-five in-depth school partnerships; online learning resources; the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, a prestigious ensemble for earlycareer musicians; intensive training and performance opportunities for youth, including the Percussion Scholarship Program, Chicago Youth in Music Festival, Crain-Maling Foundation CSO Young Artists Competition, and Young Composers Initiative; social impact initiatives, such as collaborations with Chicago Refugee Coalition and Notes for Peace for families who have lost loved ones to gun violence; and music education activities during CSO domestic and international tours.

the board of the negaunee music institute

Leslie Burns Chair

Steve Shebik Vice Chair

John Aalbregtse

David Arch

James Borkman

Jacqui Cheng

Ricardo Cifuentes

Richard Colburn

Charles Emmons

Judy Feldman

Toni-Marie Montgomery

Rumi Morales

Mimi Murley

Margo Oberman

Gerald Pauling

Kate Protextor Drehkoff

Harper Reed

Melissa Root

Amanda Sonneborn

Eugene Stark

Dan Sullivan

Paul Watford

Ex Officio Members

Jeff Alexander

Jonathan McCormick

Vanessa Moss

negaunee music institute administration

Jonathan McCormick Managing Director

Katy Clusen Associate Director, CSO for Kids

Katherine Eaton Coordinator, School Partnerships

Carol Kelleher Assistant, CSO for Kids

Anna Perkins Orchestra Manager, Civic Orchestra of Chicago

Zhiqian Wu Operations Coordinator, Civic Orchestra of Chicago

Rachael Cohen Program Manager

Charles Jones Program Assistant

Kevin Gupana Associate Director, Education & Community Engagement Giving

Frances Atkins Director of Publications and Institutional Content

Kristin Tobin Designer & Print Production Manager

Petya Kaltchev Editor

civic orchestra artistic leadership

Ken-David Masur Principal Conductor

The Robert Kohl and Clark Pellett Principal Conductor Chair

Coaches from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

Baird Dodge Principal Second Violin

Teng Li Principal Viola

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Brant Taylor Cello

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

Alexander Horton Assistant Principal Bass

William Welter Principal Oboe

Stephen Williamson Principal Clarinet

Keith Buncke Principal Bassoon

William Buchman Assistant Principal Bassoon

Mark Almond Principal Horn

Esteban Batallán Principal Trumpet

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

Michael Mulcahy Trombone

Charles Vernon Bass Trombone

Gene Pokorny Principal Tuba

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

David Herbert Principal Timpani

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Cynthia Yeh Principal Percussion

Justin Vibbard Principal Librarian

CIVIC ORCHESTRA OF CHICAGO SCHOLARSHIPS

Members of the Civic Orchestra receive an annual stipend to offset some of their living expenses during their training. The following donors have generously helped to support these stipends for the 2025–26 season.

Ten Civic members participate in the Civic Fellowship program, a rigorous artistic and professional development curriculum that supplements their membership in the full orchestra. Major funding for this program is generously provided by Lori Julian for the Julian Family Foundation

Nancy Abshire

Darren Carter, viola

Dr. & Mrs. Bernard H. Adelson Fund

Elena Galentas, viola

Robert & Isabelle Bass Foundation, Inc.

Timothy Warner, bass trombone

Rosalind Britton^ Ashley Ryoo, cello

Leslie and John Burns**

Matthew Nowlan, viola

Robert and Joanne Crown Fund

Alyssa Goh, violin

John Heo, violin

Pavlo Kyryliuk, violin

Buianto Lkhasaranov, cello

Matthew Musachio, violin

Mr.† & Mrs.† David Donovan

Chrisjovan Masso, tuba

Charles and Carol Emmons^

Will Stevens, oboe

Mr. & Mrs. David S. Fox^ Daniel Fletcher, flute

Paul † and Ellen Gignilliat

Naomi Powers, violin

Joseph and Madeleine Glossberg

Adam Davis, violin

Richard and Alice Godfrey

Ben Koenig, violin

Jennifer Amler Goldstein Fund, in memory of Thomas M. Goldstein

Alex Chao, percussion

Chester Gougis and Shelley Ochab

Tony Sanfilippo, Jr., bass

Mary Green

Walker Dean, bass

Jane Redmond Haliday Chair

Mona Mierxiati, violin

Lori Julian for the Julian Family Foundation

David Caplan, cello

Orlando Salazar,* oboe

Lester B. Knight Trust

Tricia Park, violin

Jonathon Piccolo, bass

Brandon Xu, cello

Shun-Ming Yang, cello

The League of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Kari Novilla,* harp

Leslie Fund, Inc.

Cameron Marquez,* percussion

Phil Lumpkin and William Tedford

Mason Spencer,* viola

Glenn Madeja and Janet Steidl

Erin Harrigan, horn

Maval Foundation

Arlo Hollander, trombone

Dustin Nguyen, trombone

Sean-David Whitworth, trumpet

Judy and Scott McCue and the Fry Foundation

Cierra Hall, flute

Leo and Catherine † Miserendino

Sava Velkoff,* viola

Ms. Susan Norvich

Yulia Watanabe-Price, violin

Margo and Mike Oberman

Hamed Barbarji,* trumpet

Julian Oettinger and Gail Waits, in memory of R. Lee Waits

Kyle Scully, timpani

Bruce Oltman and Bonnie McGrath†^

Alexander Wallack, bass

Earl† and Sandra Rusnak

Ebedit Fonseca, violin

Barbara and Barre Seid Foundation

Emmett Conway, horn

Micah Northam, horn

The George L. Shields Foundation, Inc.

Yat Chun Justin Pou, viola

Guillermo Ulloa, oboe

Abigail Yoon, violin

Dr. & Mrs. R. J. Solaro ^

Lara Madden Hughes, violin

David W. and Lucille G. Stotter Chair

Mia Smith, violin

Ruth Miner Swislow Charitable Fund

Rose Haselhorst, violin

Ms. Liisa Thomas and Mr. Stephen Pratt

Nick Reeves, cello

Peter and Ksenia Turula

Abner Wong, trumpet

Lois and James Vrhel

Endowment Fund

Albert Daschle, double bass

Paul and Lisa Wiggin

Layan Atieh, horn

Eden Stargardt,* horn

Marylou Witz

Justine Jing Xin Teo,* violin

Women’s Board of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association

Elizabeth Kapitaniuk, clarinet

Anonymous J Holzen,* cello

Anonymous^

Carlos Chacon, violin

Anonymous^

Hojung Christina Lee, violin

Anonymous^

Judy Huang, viola