25 26 SEASON

We’ve

25 26 SEASON

We’ve

We’re honored they’ve done the same for us.

Ranked

We believe the connection between you and your advisor is everything. It starts with a handshake and a simple conversation, then grows as your advisor takes the time to learn what matters most–your needs, your concerns, your life’s ambitions. By investing in relationships, Raymond James has built a firm where simple beginnings can lead to boundless potential.

ONE HUNDRED THIRTY-FIFTH SEASON

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

KLAUS MÄKELÄ Zell Music Director Designate | RICCARDO MUTI Music Director Emeritus for Life

Thursday, December 11, 2025, at 7:30 Friday, December 12, 2025, at 1:30 Saturday, December 13, 2025, at 7:30

Gianandrea Noseda Conductor

James Ehnes Violin

DEBUSSY Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun

BRITTEN Violin Concerto, Op. 15

Moderato con moto— Vivace— Passacaglia: Andante lento (un poco meno mosso)

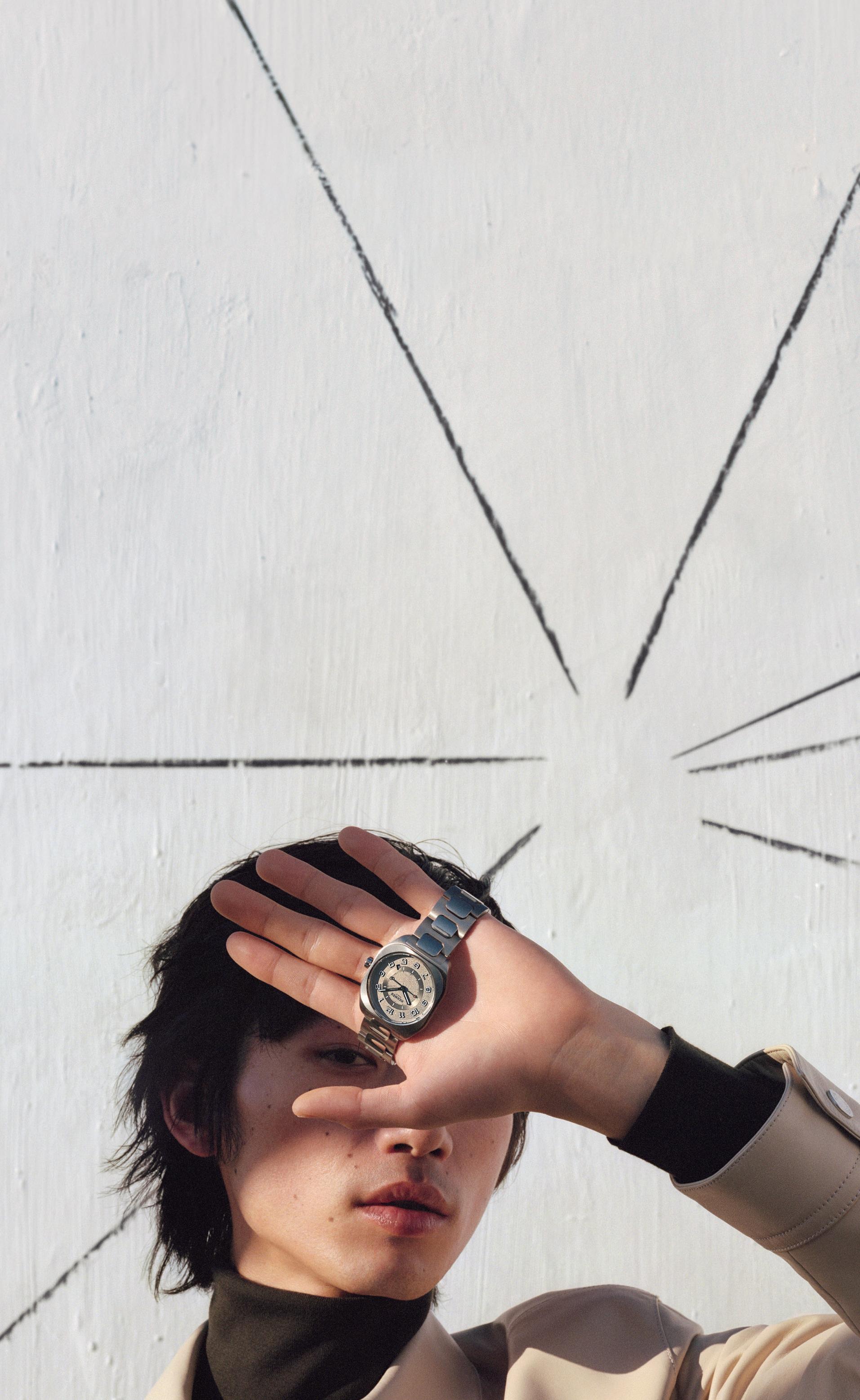

JAMES EHNES

INTERMISSION

PROKOFIEV

Symphony No. 4 in C Major, Op. 112

Andante—Allegro eroico

Andante tranquillo

Moderato, quasi allegretto Allegro risoluto

These concerts are generously sponsored by United Airlines.

The appearance of Gianandrea Noseda is made possible by the Juli Plant Grainger Fund for Artistic Excellence.

The appearance of James Ehnes is made possible by the Grainger Fund for Excellence.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra thanks United Airlines for sponsoring these performances.

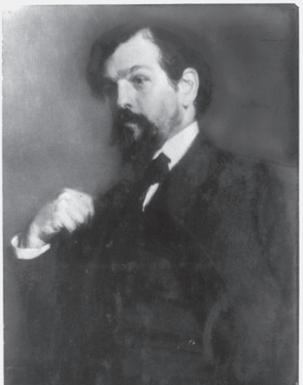

CLAUDE DEBUSSY

Born August 22, 1862; Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

Died March 25, 1918; Paris, France

The year Debussy returned to Paris from Rome—where he unhappily served time as the upshot of winning the coveted Prix de Rome—he bought a copy of Stéphane Mallarmé’s The Afternoon of a Faun to give to his friend Paul Dukas, who didn’t get beyond the preliminary round of the competition. Eventually Dukas would establish his credentials with The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, but by then Debussy was already famous for his Prelude to The Afternoon of a Faun.

By 1887 Stéphane Mallarmé had begun hosting his famous gatherings every Tuesday evening in his apartment, where his daughter Geneviève served the punch. Debussy sometimes dropped in at 89, rue de Rome (an unfortunate reminder of a city he had happily left) to partake of the punch and the lively exchange of ideas, and in time he and Mallarmé became friends. In 1898 he was among those first notified of the poet’s death.

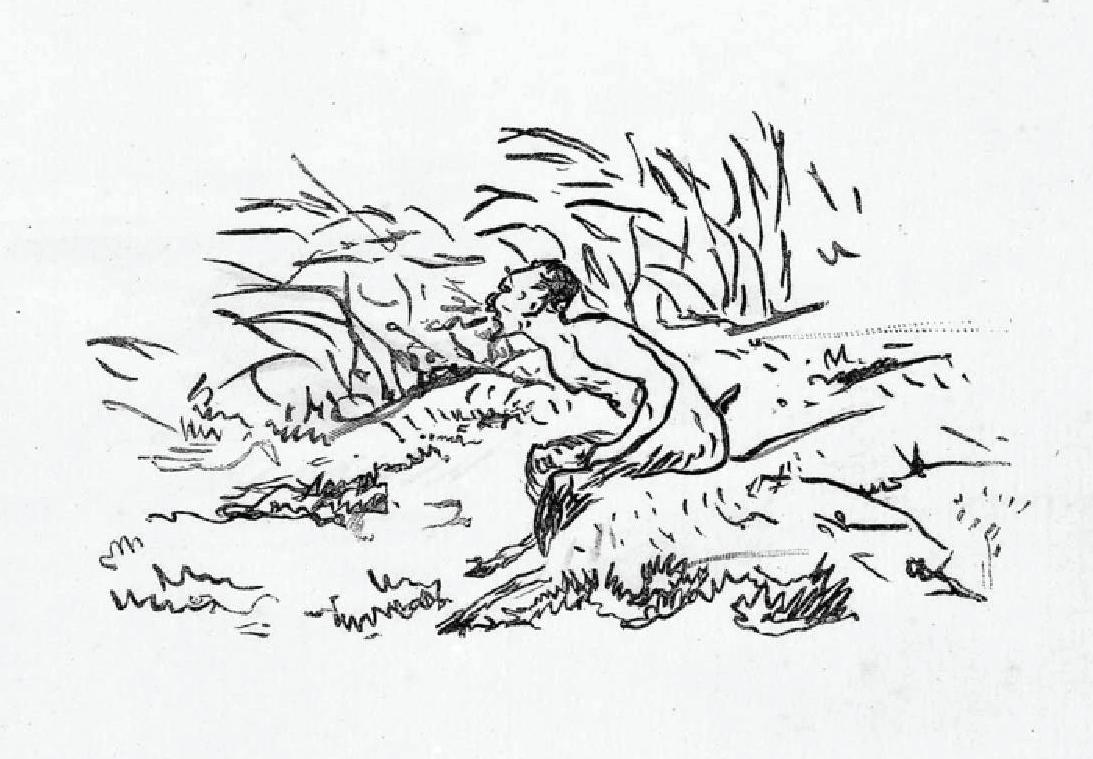

Mallarmé’s poem, The Afternoon of a Faun, was published in 1876, in a slim, elegantly bound volume with a line drawing by Édouard Manet on the cover. We don’t know when Debussy first thought of interpreting Mallarmé’s faun and his dreams of conquering nymphs, nor to what degree he and Mallarmé

COMPOSED

1892–October 23, 1894

FIRST PERFORMANCE

December 22, 1894; Paris, France

INSTRUMENTATION

3 flutes, 2 oboes and english horn, 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 2 harps, cymbals, strings

APPROXIMATE PERFORMANCE TIME 10 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

November 23 and 24, 1906, Orchestra Hall. Frederick Stock conducting

July 5, 1936, Ravinia Festival. Ernest Ansermet conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

July 21, 2013, Ravinia Festival. James Conlon conducting

March 2, 4, and 7, 2017, Orchestra Hall. Esa-Pekka Salonen conducting

CSO RECORDINGS

1976. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

1990. Sir Georg Solti conducting. London

this page, from top : Claude Debussy, portrait by Jacques-Émile Blanche (1861–1942), ca. 1907–10, as photographed by Émile Arthur Crevaux, Paris, France

Frontispiece for the poem The Afternoon of a Faun by Stéphane Mallarmé (1842–1898), published as a deluxe limited-edition pamphlet. Wood engraving by Édouard Manet (1832–1883), 1876

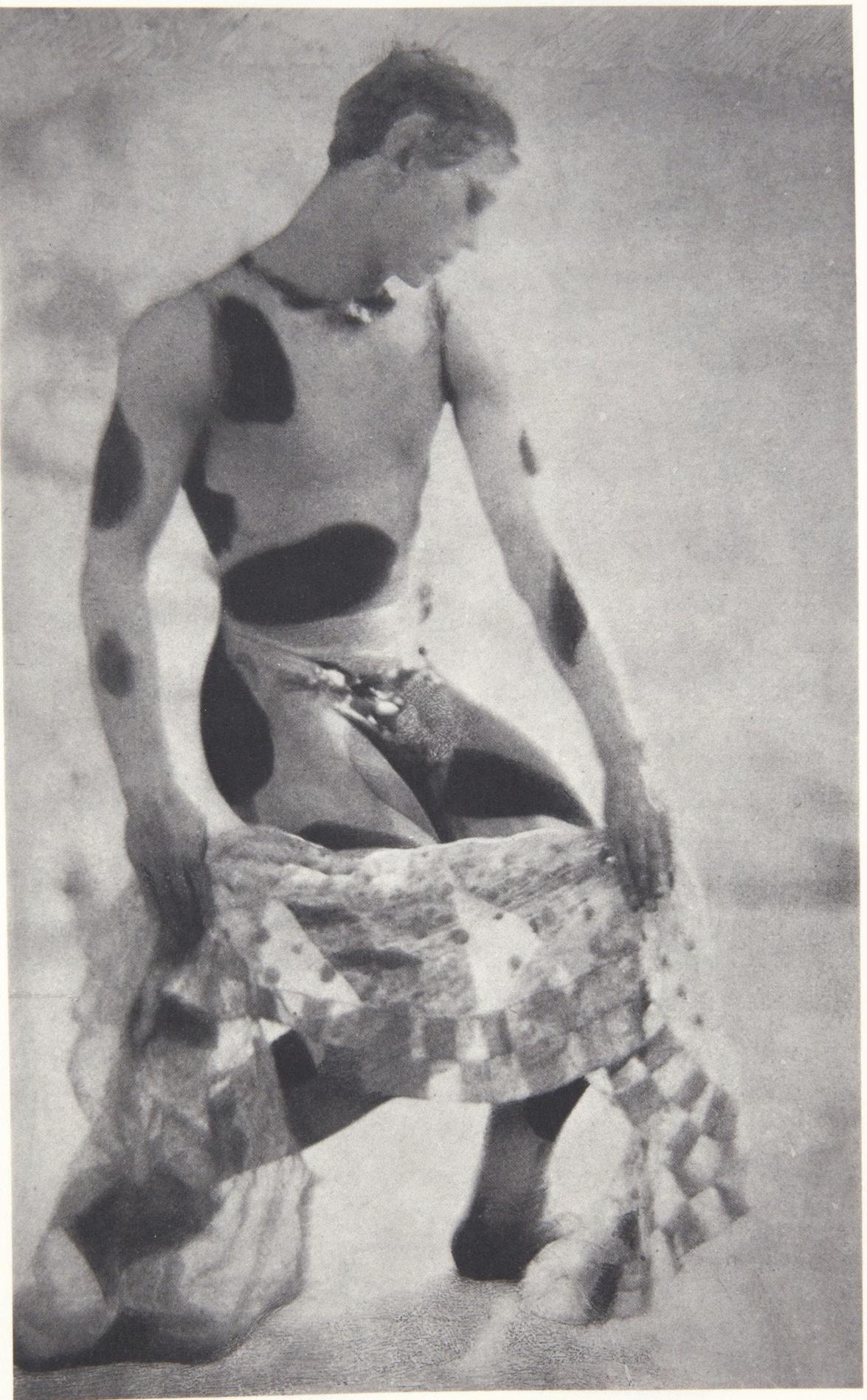

next page : Vaslav Nijinsky (1889–1950) in profile, holding a veil retrieved from an escaping nymph, in the premiere of The Afternoon of a Faun, as photographed by Adolph de Meyer (1868–1946), May 29, 1912

discussed the prospect. As late as 1891, Mallarmé was still contemplating some kind of dramatized reading of his text, and perhaps Debussy was meant to fit into that scheme. Debussy began sketching his music in 1892. In 1893, and again in 1894, announcements promised “Prélude, interludes et paraphrase finale” for The Afternoon of a Faun, but the full orchestral score Debussy finished on October 23, 1894, contained only the prelude.

Mallarmé first heard this music in Debussy’s apartment, where the composer played his score at the piano. “I didn’t expect anything like this,” Mallarmé said. “This music prolongs the emotion of my poem and sets its scene more vividly than color.” The first orchestral performance, on December 22, was an immediate success (despite poor horn playing), and an encore was

demanded. Mallarmé was there; he later said that Debussy’s music “presents no dissonance with my text: rather, it goes further into the nostalgia and light with subtlety, malaise, and richness.

Revolutionary works of art are seldom granted such instant, easy success. Inevitably, there was some question about the score’s programmatic intentions, to which Debussy responded at once: “It is a general impression of the poem, for if music were to follow more closely it would run out of breath, like a dray horse competing for the grand prize with a thoroughbred.”

The music itself seems to have ruffled few feathers, despite the way it quietly, yet systematically, overturns tradition and opens new frontiers in musical language. Camille SaintSaëns was one of the few detractors, yet even his put down—“It’s as much a piece of music as the palette a painter has worked from is a painting”— suggests an understanding that Debussy was constructing a piece of music in a radical way. (Saint-Saëns’s words recall Mallarmé’s own famous, often misunderstood mission “to paint not the thing but the effect it produces.”) Toward the end of his life, Maurice Ravel remembered that “it was [upon] hearing this work, so many years ago, that I first understood what real music was.” Pierre Boulez would later date the awakening of modern music to Debussy’s score.

Saint-Saëns might well have noted how the now-famous opening flute melody, all sinuous curves and slippery rhythms, resembles the most popular melody he would ever write, “Mon coeur s’ouvre a ta voix” (known in English as “My Heart at Thy Sweet Voice”) from Samson and Dalilah. But where Dalilah’s aria is rooted in D-flat major and common time, Debussy’s portrait of the faun eludes our attempts to tap our feet or to establish a key; its insistence on the interval from C-sharp to G-natural argues repeatedly against the E major key signature printed on the page.

The whole of the Prelude can be considered a series of variations on a single theme, and we can simply listen to the ways it changes, almost imperceptibly, and grows. There’s a more conventional middle section in D-flat, urgently

lyrical and more fully scored, which raises the music to fortissimo for the only time in the piece and then sinks down again with the sounds of the flute melody.

Debussy uses the orchestra with extraordinary finesse, drawing such rich and provocative sounds from his winds (including three flutes, an english horn, and four horns) that we scarcely notice the absence of trumpets, trombones, and timpani. The only percussion instruments necessary are two antique cymbals, each allotted

just five notes apiece—a triumph of artistry over cost-efficiency.

In 1912 Sergei Diaghilev, who would soon create a notorious scandal with Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, produced a ballet from Debussy’s music. It was danced and choreographed by the celebrated Nijinsky, who claimed never to have read Mallarmé’s text, and who caused a sensation by foisting heavy-duty eroticism on Debussy’s delicate score.

Born November 22, 1913; Lowestoft, Sussex, England

Died December 4, 1976; Aldeburgh, Suffolk, England

Benjamin Britten was in the Barcelona audience on the historic night Alban Berg’s Violin Concerto received its posthumous premiere in April 1936. Britten and the Spanish violinist Antonio Brosa had gone to Barcelona to perform Britten’s Suite for Violin and Piano, which had been chosen for the ISCM festival. The International Society for Contemporary Music festival, held in a different city every two years, was a major event on the contemporary-music calendar. Britten had been invited once before, to the 1934 festival in Florence, Italy, where, despite the honor, he found much of the music “pretty poor.” He had a far better time in Barcelona, taking in everything from the cathedral (he was intoxicated by the “sensuous beauty of darkness and incense”) and the restaurants (“where the food was taken seriously,” as he recalled once back in cuisine-challenged Britain) to the disorienting red-light district, with “sexual temptations of every kind at each corner.”

But it was Berg’s dark and elegiac violin concerto that made the strongest impression on him. Britten had already discovered the power of Berg’s music—a 1933 diary entry mentions the “imagination and intense emotion” of the Lyric Suite, and after hearing the orchestral fragments from Wozzeck, he said that Strauss’s Death and Transfiguration seemed dull and banal.

above: Benjamin Britten, ca. 1940s

COMPOSED

1938–39

FIRST PERFORMANCE

March 28, 1940, New York City

INSTRUMENTATION

solo violin, 3 flutes (2nd and 3rd doubling piccolo), 2 oboes (2nd doubling english horn), 2 clarinets, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, timpani, percussion (glockenspiel, triangle, snare drum, tenor drum, bass drum, cymbals), harp, strings

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

June 9, 10, and 11, 2005, Orchestra Hall. Frank Peter Zimmermann as soloist, Manfred Honeck conducting July 17, 2013, Ravinia Festival. Maxim Vengerov as soloist, James Conlon conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

June 5, 6, 7, and 8, 2014, Orchestra Hall. Simone Lamsma as soloist, Jaap van Zweden conducting

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME

32 minutes

For a while, Britten had even contemplated going to Vienna to study with Berg. (He was discouraged by the director of the Royal College of Music in London, where he was studying, for fear of musical corruption.) Now with Berg dead less than six months, Britten found the experience of listening to his last finished work, the great Violin Concerto, “just shattering—very simple and touching.” It’s no coincidence that in another two years Britten would begin his own violin concerto, designed for his Barcelona companion and performing partner, Antonio Brosa.

Britten began the concerto in November 1938. When his friends W.H. Auden and Christopher Isherwood left England for the United States early in 1939, Britten decided to follow, hoping to find a climate more accepting of his left-wing politics and pacifist stance, his artistic beliefs, and his homosexuality. Britten was obviously at a crossroads in his life and in his career—he later called himself “a discouraged young composer—muddled, fed-up, and looking for work, longing to be used”—and he believed that the change of scene would do him good.

In April 1939 he set off for North America with Peter Pears, the tenor who would become his great interpreter and lifelong companion. They stopped first in Montreal, and from there crossed over to the United States, staying in Grand Rapids, Michigan, for ten days and then settling in New York City. Over the next two and a half years, Britten wrote little music, but he came of age as a composer nevertheless. Although America wasn’t quite what he expected—he hated the noise and dirt of New York, froze in Chicago, and found Hollywood “really horrible”— it offered Britten a neutral setting in which to address both personal and artistic issues. When he returned to England in March 1942, he took with him a book of poems by George Crabbe that he had bought in a Los Angeles bookstore, and he was already plotting the opera Peter Grimes, based on Crabbe’s The Borough, that would soon make him the most celebrated composer in England since Henry Purcell.

The Violin Concerto was one of two unfinished scores Britten brought with him to the United States (the other was the song cycle Les illuminations, a setting of poems by Rimbaud). He resumed work on the concerto in Amityville, New York, over the summer and finished it on September 29 in Saint Jovite, Quebec. Although Les illuminations was performed first (in London in January 1940, while the composer was still in the States), the Violin Concerto is Britten’s first “American” work—the first work he completed here and the first to get a high-profile New York premiere, on March 28, 1940, in Carnegie Hall. Although Britten was still trying to shake the “vile cold and flu” he caught in Chicago, he rallied once Brosa arrived in New York to prepare for the performance. The concerto was well received, and even “the N.Y. Times’s old critic (who is the snarkiest [sic] and most coveted here),” Britten wrote, “was won over, so that was fine.” Britten was quick to notify his publisher, Ralph Hawkes: “So far it is without question my best piece.”

Years after playing the premiere, Brosa told a radio interviewer that the snappy figure in the timpani that opens the concerto was a “Spanish” rhythm—a reference to the violinist’s nationality and perhaps to the Barcelona collaboration that set this piece in motion. A violin concerto that begins with the solo timpani followed by a high-flying melody for the soloist automatically evokes the celebrating opening of Beethoven’s great score, and like Beethoven’s famous motto, Britten’s rhythmic pattern later returns as a signpost throughout his work.

Britten writes three movements, turning the traditional fast-slow-fast pattern inside out, so that the concerto begins and ends with expansive, contemplative music. The first movement switches between dreamy, luminous music, over which the violin lingers and soars, and more energized Spanish dance rhythms. There’s a particularly haunting passage near the end for lush high strings accompanied by the pizzicato rhythms of the solo violin—followed immediately

by the reverse, with a lyrical solo song over plucked string chords.

The central scherzo is demonic and driven. Again, Britten demonstrates his ear for unexpected colors, including an astonishing passage for two piccolos and tuba over string tremolos. A brilliant cadenza, which recalls the Spanish rhythms of the opening, moves directly into the finale. This is the first of Britten’s grand passacaglias, a set of variations over a repeating bass line. (There’s a particularly spectacular one in

Born April 23, 1892; Sontsovka, Ukraine

Died March 5, 1953; Moscow, Russia

Peter Grimes.) It’s the trombones, making their first appearance in the piece, who get to deliver the passacaglia theme, an arresting progression of whole and half steps moving up the scale and then back down. In the nine variations that follow, each different in color and character, the theme moves from orchestra to solo and back. The final variation, consisting of nothing but slow chords and a stuttering, pleading violin line, is as eloquent and moving as anything Britten ever wrote.

There are two Fourth symphonies by Prokofiev, composed some seventeen years apart. The first was written during the winter of 1929–30, on the coattails of Prokofiev’s final ballet for Diaghilev, The Prodigal Son. The second—the one performed this week—began simply enough, as a revision of a symphony that had never quite satisfied the composer, but it turned into a work so different in scale and impact that it could almost stand on its own as a new symphony. Prokofiev didn’t give it a new number, of course—it is too clearly a reworking of an earlier piece rather than a new composition altogether. But he did republish it with a new opus number—112—which places it directly after his Sixth Symphony in the chronology of his output. (Returning to the same subject matter again and again, as Böcklin did in The Isle of the Dead, a commonplace in the visual arts, is relatively rare in music.)

This tale of two symphonies begins with a commission from the Boston Symphony Orchestra to celebrate its fiftieth

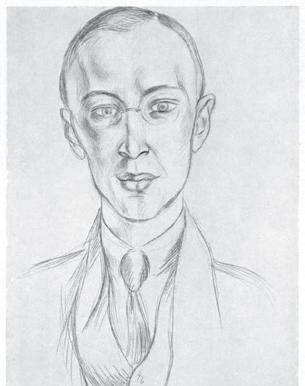

this page : Sergei Prokofiev, drawing by Henri Matisse (1869–1954), April 25, 1921, published in the program for the fourteenth season of the Ballets Russes at the Théâtre de la Gaîté-Lyrique, Paris, where the composer’s ballet Chout was premiered on May 17. Bibliothèque nationale de France | next page : Prokofiev performing his Third Piano Concerto, February 1936, with the Brussels Symphony Orchestra under Désiré Defauw at the Palais de Beaux-Arts, Brussels, Belgium. Drawing by Hilda Wiener (1877–1940), autographed by the composer

COMPOSED

1929–30, revised in 1947

FIRST PERFORMANCE

November 14, 1930; Boston, Massachusetts

Revised version: January 5, 1957; Moscow, Soviet Union

INSTRUMENTATION

2 flutes and piccolo, 2 oboes and english horn, 2 clarinets, E-flat clarinet and bass clarinet, 2 bassoons and contrabassoon, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones, tuba, percussion (triangle, woodblock, tambourine, side drum, bass drum, cymbals), harp, piano, strings

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

August 12, 1976, Ravinia Festival. Lawrence Foster conducting December 17, 18, and 19, 1987, Orchestra Hall. Neeme Järvi conducting

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

March 25, 27, and 30, 2010, Orchestra Hall. Vladimir Jurowski conducting

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME

34 minutes

anniversary in 1930. Perhaps Prokofiev wasn’t yet in the mood to compose a new symphony—his Third was less than a year old at the time—but he was insulted by the offer from Boston music director Serge Koussevitzky, who had already become one of the composer’s most generous champions. “For one thousand dollars,” Prokofiev responded, “you can order a symphony from Lazar or Tansman, but I find it awkward to accept such a commission. Prokofiev is paid three to five thousand dollars for a symphony, or even for the right to announce that ‘we’ve commissioned it from him’.” Prokofiev was unmoved by the news that Stravinsky had accepted the same sum (for the work that would turn out to be his landmark Symphony of Psalms). Why didn’t the orchestra just play his latest work, the Sinfonietta, instead, he asked—or buy the manuscript of a new piece for one thousand dollars instead of commissioning it. Finally, Koussevitzky lost patience:

States on a long concert tour, he and Koussevitzky continued their discussions, both parties finally agreeing to the original conditions, and Prokofiev eventually began his new symphony, often writing aboard the trains that took him from one city to another. He appeared with the Chicago Symphony twice that February, playing his First and Second piano concertos (he had made his debut with the Orchestra in 1918 in the U.S. premiere of the First and returned in 1921 to give the world premiere of the Third Piano Concerto). He also gave five concerts with the Boston Symphony that winter, so he and Koussevitzky either had already patched up their differences or chose to work them out making music together. Prokofiev returned to Paris in time for summer, and he finished the Fourth Symphony there, just before retreating to the French countryside for the month of August.

I must tell you that in spite of all my propaganda during these last five years, your name is not so popular as that of Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, nor so popular that I can transport my orchestra to New York to give a Prokofiev festival. This doesn’t mean that festivals should be given only to honor the dead—I hope that I will live to a time when a festival will be given in your honor—but we must be patient and not allow any silly little things, any pleasant nonentities, like your Sinfonietta, to be performed.

During the winter of 1929–30, as Prokofiev gradually worked his way across the United

When he wrote his previous symphony, the Third, Prokofiev discovered a collage-like way of composing, which allowed him to incorporate whole chunks of his opera The Flaming Angel into an entirely new work. Now, in his Fourth Symphony, he developed the process further, drawing upon themes and material from his recent ballet, The Prodigal Son, Diaghilev’s last production with the Ballets Russes before his sudden death in August 1929. Although the ballet had been a success, with choreography by Balanchine and designs by Georges Rouault, Prokofiev evidently felt that his music deserved a symphonic framework. When Koussevitzky expressed his concern that Prokofiev was again raiding his theater work for the concert hall, Prokofiev argued that Beethoven had done the same thing when he based the finale of his

Eroica Symphony on his ballet music for The Creatures of Prometheus. (Haydn, too, had reused entire movements from his incidental music for Il distrato in his sixtieth symphony that now uses the play’s name as its subtitle.) Later, Prokofiev also said that his new symphony incorporated a significant amount of music originally written for The Prodigal Son but never included in the ballet.

The Boston premiere of Prokofiev’s Fourth Symphony in November 1930 was indifferently received, to the composer’s surprise—the following year, clearly piqued by the public’s response, he told a French reporter that he thought his most recent works were his best, singling out both The Prodigal Son and the Fourth Symphony. For the next fourteen years, Prokofiev avoided the form of the symphony altogether. Then, in the mid-1940s, he composed two—the heroic Fifth, in 1944, and the Sixth, a wartime lament, in 1945–46. It was then that he decided to rethink the Fourth and began the process of turning a modest symphony into a large and imposing score that matched the scale of the two new symphonies.

The revised Fourth Symphony is half again as long as the original. Some of it is entirely new, such as the forceful introduction that now precedes the quiet opening of the earlier score. Some of it expands on what was already there, such as the elaborate first-movement development section, which is four times as long (and manages to weave the new introduction into the interplay of older material). Some of it is simply redecorating—a few measures here, a new transition there. Many passages remain unchanged or just slightly reorchestrated. (Prokofiev’s 1947 orchestra is marginally larger than the one he called for seventeen years earlier—there is now

an E-flat clarinet, for example, as well as a third trumpet, harp, and piano.) The entire first movement is a characteristic Prokofiev landscape, with ardent lyricism giving way to bracing, highly charged music (originally given to the Prodigal Son’s false friends, who fleece him when they get their chance).

The slow movement grew out of music Prokofiev wrote to accompany the Prodigal’s return home, where he is taken in by his forgiving father. It features one of the big expressive tunes at which Prokofiev excelled—“I have become simpler and more melodic,” he told the critic Olin Downes in 1930, saying that he was tired of being pigeonholed as the enfant terrible who wrote abrasive, dissonant works.

The third movement began life as the dance for the Beautiful Maiden who seduces the Prodigal Son (this, a departure from the biblical story, was added to the ballet scenario for its dance opportunities and, well, sex appeal). Both versions of this movement borrow this graceful, sensual music, almost unchanged, from the ballet score. In 1947 Prokofiev added a wonderful coda.

“The finale was the most difficult part,” Prokofiev later said. Of the four movements, this is one that was most substantially rewritten in 1947. It is based on music originally composed to express the Prodigal’s eagerness to escape his home and family, and to give a sense of his youth and passion. For Prokofiev, who had left his own homeland in his twenties only to return some two decades later, it is also, in part, a self-portrait.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

February 25, 26, 27, and March 2, 2010, Orchestra Hall. Saariaho’s Orion, Beethoven’s Piano Concerto no. 3 with Radu Lupu, and Rachmaninov’s Symphony no. 1

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES

February 17, 18, and 19, 2011, Orchestra Hall. Stravinsky’s Divertimento, Suite from The Fairy’s Kiss; Borodin’s Polovtsian Dances from Prince Igor; and Brahms’s Piano Concerto no. 2 with Leif Ove Andsnes

August 2, 2012, Ravinia Festival. Rachmaninov’s Vocalise with Nicole Cabell, Piano Concerto no. 4 with Sean Botkin, and Symphonic Dances

Gianandrea Noseda is one of the world’s most soughtafter conductors, equally recognized for his artistry in both the concert hall and opera house. The 2025–26 season marks his ninth as music director of the National Symphony Orchestra at the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts in Washington (D.C.).

Under Noseda’s artistic direction, the National Symphony has experienced a notable resurgence in both critical and public acclaim. His tenure has ushered in a new era of creative energy and excellence, and the orchestra’s heightened visibility has been bolstered through digital streaming initiatives and a dedicated recording label distributed by LSO Live. These releases often feature Noseda himself, who also is principal guest conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra.

Noseda’s discography encompasses more than eighty recordings that reflect the breadth of his musical curiosity and command over a wide repertoire. His albums, released on such prominent labels as Deutsche Grammophon, Chandos, and LSO Live, have earned consistent critical praise.

In 2021 Noseda took on the role of general music director of the Zurich Opera House. In

May 2024 he reached a significant milestone by conducting two critically praised Ring cycles in a new production by director Andreas Homoki. His interpretation of Wagner’s monumental work contributed to his recognition by the jury of the German OPER! AWARDS as Best Conductor in 2023.

Noseda previously served as music director of Teatro Regio Torino from 2007 to 2018, a period widely regarded as a golden era for the opera company. Over the course of his career, he has held influential positions with many of the world’s leading ensembles, including the BBC Philharmonic, Israel Philharmonic Orchestra, Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, Orchestra Sinfonica Nazionale della RAI, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, and the Stresa Festival in Italy.

Committed to nurturing the next generation of musicians, Noseda is also deeply involved in educational and youth orchestra initiatives. Last summer, he led a tour of Asia with the National Youth Orchestra USA, which began with a performance at Carnegie Hall and continued with concerts in Osaka, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Beijing, Shanghai, and Seoul.

Noseda’s commitment to global music education is also evident in his role as founding music director of the Tsinandali Festival and the Pan-Caucasian Youth Orchestra, established in 2019 in the village of Tsinandali, Georgia.

A native of Milan, Italy, Gianandrea Noseda has been honored with the title of Commendatore al Merito della Repubblica Italiana, recognizing his contributions to Italy’s cultural heritage. Other accolades include being named Conductor of the Year by Musical America (2015), International Opera Awards Conductor of the Year (2016), and a recipient of the Puccini Award (2023).

On December 7, 2024, Noseda received the Certificate of Civic Merit from Giuseppe Sala, mayor of Milan, as part of the city’s distinguished Ambrogino d’Oro awards, honoring his enduring contributions to the arts both in Italy and abroad.

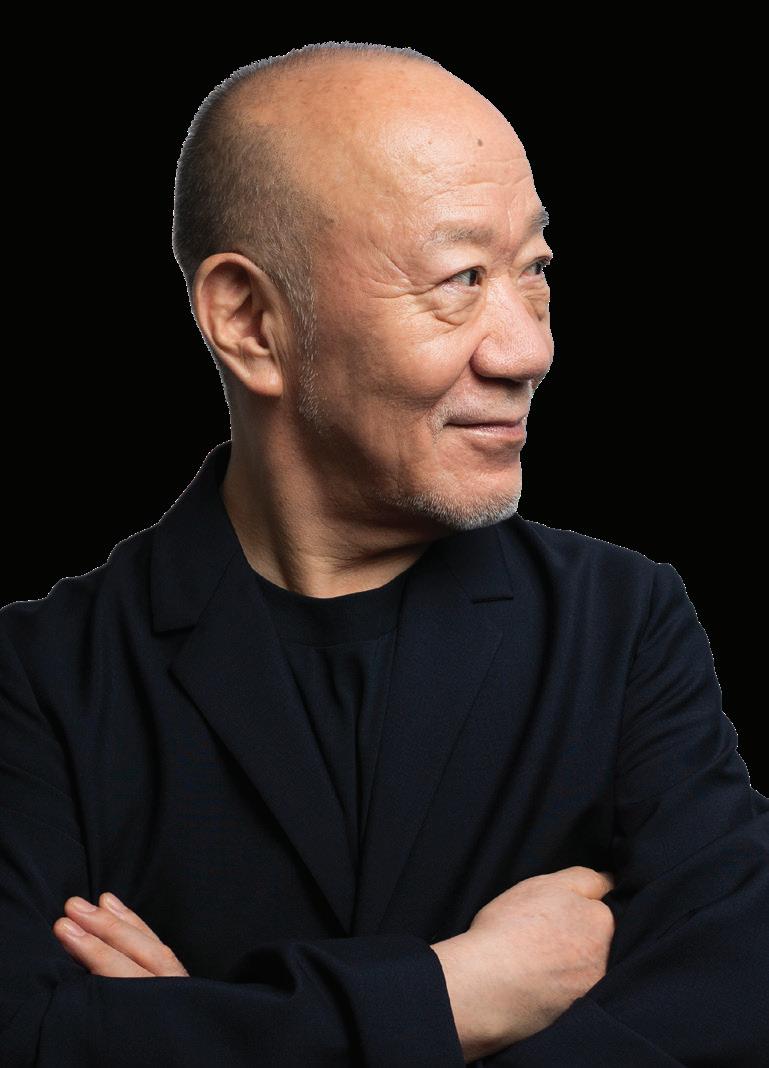

PHOTO BY STEFANO PASQUALETTI

James Ehnes Violin

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

July 20, 1997, Ravinia Festival. Lalo’s Symphonie espagnole, Erich Kunzel conducting

April 27, 28, 29, and May 2, 2006, Orchestra Hall. Weill’s Concerto for Violin and Wind Orchestra, David Robertson conducting

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES

October 26 and 27, 2017, Orchestra Hall; October 28, 2017, Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Barber’s Violin Concerto, James Gaffigan conducting

August 10, 2024, Ravinia Festival. Mozart’s Violin Concerto no. 5, James Conlon conducting

James Ehnes has established himself as one of the most sought-after musicians on the international stage. Gifted with a rare combination of stunning virtuosity, serene lyricism, and unfaltering musicality, he is a favorite guest at the world’s most celebrated concert halls.

Recent and upcoming orchestral highlights include engagements with the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra Amsterdam, TonhalleOrchester Zürich, NDR Elbphilharmonie Orchestra, London Philharmonic Orchestra, NHK Symphony Tokyo, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Boston Symphony Orchestra, and the Cleveland Orchestra.

A devoted chamber musician, Ehnes is artistic director of the Seattle Chamber Music Society and leader of the Ehnes Quartet. As a recitalist, he performs regularly at Wigmore Hall in London, Carnegie Hall in New York, the Royal Concertgebouw, Verbier Festival, Dresden

Music Festival, and the Aix-en-Provence Easter Festival.

This season, Ehnes embarks on his fiftieth birthday recital tour in his native Canada, with performances in every province and territory.

Ehnes holds an extensive discography and has won many distinctions for his recordings, including two Grammy, three Gramophone, and twelve Junos awards, the most of any classical musician.

In 2021 he received the coveted Artist of the Year Award at the 2021 Gramophone Awards, which celebrated his recent contributions to the recording industry, including the launch of an online recital series, Recitals from Home, released in 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Ehnes recorded Bach’s six sonatas and partitas and Ysaÿe’s six sonatas from his home and released six episodes over the period of two months. These recordings have received great critical acclaim by audiences worldwide.

Ehnes began violin studies at the age of five, became a protégé of noted Canadian violinist Francis Chaplin at nine, and made his orchestral debut at thirteen with the Orchestre symphonique de Montréal. He continued his studies with Sally Thomas at the Meadowmount School of Music and the Juilliard School, winning the Peter Mennin Prize for Outstanding Achievement and Leadership in Music on his graduation in 1997. He is a member of the Order of Canada and the Order of Manitoba, a fellow of the Royal Society of Canada, and an honorary fellow and visiting professor at the Royal Academy of Music in London. Since 2024 he has been professor of violin at the Jacobs School of Music at Indiana University Bloomington.

He plays the “Marsick” Stradivarius of 1715. Intermusica represents James Ehnes worldwide.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association gratefully acknowledges the Helen Zell Contemporary Music Fund for its leadership support of the presentation of contemporary music in the CSO’s 2025–26 season.

Major support is also provided by Sally Mead Hands Foundation, The Irving Harris Foundation, and Lori Julian for the Julian Family Foundation.

Sep 25–28

PÉPIN Les Eaux célestes

Oct 3–4

SIMON Fate Now Conquers MUSGRAVE Piccolo Play

Dec 18–20

WIDMANN Con brio CHIN subito con forza

Feb 5–7

SMITH Lost Coast

Feb 12–15

THOMPSON To See the Sky

Apr 2–4

TÜÜR Prophecy

May 7–9

LIEBERSON Neruda Songs

May 21–23

CLYNE Sound and Fury

FORMER MEAD COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE

June 18–21

MONTGOMERY Banner

FORMER MEAD COMPOSER-IN-RESIDENCE

Contemporary music remains a vital thread in the CSO’s artistic legacy, and this generous support ensures that bold, innovative repertoire continues to resonate with audiences today. We are proud to carry forward this tradition by featuring compelling new works throughout the 2025–26 concert season.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra—consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 135th season in 2025–26. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027. In July 2025, Donald Palumbo became the third director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is the CSO’s Artist-in-Residence for the 2025–26 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007— have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

Tax-deductible donations do more than support the concerts you love — they impact more than 200,000 people through education and community engagement programs each year. Thanks to a generous matching grant, all gifts to the CSOA will be doubled. Make a difference with your gift today.

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Joyce DiDonato Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler

Chair, endowed by an

anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor*

Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C.

Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu*

Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Gabriela Lara

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin

Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky §

Wendy Koons Meir

Ronald Satkiewicz ‡

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen

Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak §

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Olivia Jakyoung Huh

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton

Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton

Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson § Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M.

Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer

Assistant Principal

The Gilchrist Foundation,

Jocelyn Gilchrist Chair

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for Life

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh

Assistant Principal

The Governing

Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman

Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich ‡

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Timothy Higgins Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin

Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority. ‡ On sabbatical § On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. The Louise H. Benton Wagner chair is currently unoccupied.

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos

Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Ariel Seunghyun Lee Violin

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis

Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.

Discover more about the musicians, concerts, and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association online, at cso.org.

Find articles and program notes, listen to CSOradio, and watch CSOtv at Experience CSO.

cso.org/experience

Get involved with our many volunteer and affiliate groups.

cso.org/getinvolved

Connect with us on social @chicagosymphony

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Board of Trustees

OFFICERS

Mary Louise Gorno Chair

Chester A. Gougis Vice Chair

Steven Shebik Vice Chair

Helen Zell Vice Chair

Renée Metcalf Treasurer

Jeff Alexander President

Kristine Stassen Secretary of the Board

Stacie M. Frank Assistant Treasurer

Dale Hedding Vice President for Development

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Administration

SENIOR LEADERSHIP

Jeff Alexander President

Stacie M. Frank Vice President & Chief Financial Officer, Finance and Administration

Dale Hedding Vice President, Development

Ryan Lewis Vice President, Sales and Marketing

Vanessa Moss Vice President, Orchestra and Building Operations

Cristina Rocca Vice President, Artistic Administration

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

Eileen Chambers Director, Institutional Communications

Jonathan McCormick Managing Director, Negaunee Music Institute at the CSO

Visit cso.org/csoa to view a complete listing of the CSOA Board of Trustees and Administration.

For complete listings of our generous supporters, please visit the Richard and Helen Thomas Donor Gallery.

cso.org/donorgallery

MAR 5-6

Mäkelä Conducts The Rite of Spring

APR 16-18

Evgeny Kissin with the CSO

APR 23-26

Hisaishi Conducts Hisaishi

MAY 12

Samara Joy & the CSO

JUNE 23