NINETY-FIFTH SEASON

Sunday, November 16, 2025, at 3:00

Piano Series

HAYATO SUMINO

J.S. BACH Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C Major from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, BWV 870

J.S. BACH Partita No. 2 in C Minor, BWV 826

Sinfonia

Allemande

Courante

Sarabande

Rondeau

Capriccio

CHOPIN Nocturne in C Minor, Op. 48, No. 1

Scherzo in B Minor, Op. 20, No. 1

INTERMISSION

GULDA Prelude and Fugue

SUMINO New Birth (after Chopin)

Recollection (after Chopin)

KAPUSTIN Selections from Eight Concert Etudes, Op. 40

No. 1. Prelude: Allegro assai

No. 2. Reverie: Moderato

No. 3. Toccatina: Allegro

No. 7. Intermezzo: Allegretto

No. 8. Finale: Prestissimo

SUMINO Three Nocturnes

Nocturne No. 1 (Pre Rain)

Nocturne No. 2 (After Dawn)

Nocturne No. 3 (Once in a Blue Moon)

RAVEL Boléro (arr. Sumino)

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

COMMENTS by Richard E. Rodda

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

Born March 21, 1685; Eisenach, Germany

Died July 28, 1750; Leipzig, Germany

Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C Major from The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book 2, BWV 870

COMPOSED around 1740

“For the use and profit of the musical youth desirous for learning, as well as for the pleasure of those already skilled in this study” was the heading on the manuscript of the twenty-four preludes and fugues that Bach composed during his tenure as music director at the court of Anhalt-Cöthen from 1717 to 1723. The pieces were originally intended as study material for his sons Wilhelm Friedemann and Carl Philipp Emanuel, and he made a copy of the volume for each of them (Friedemann was thirteen in 1723; Emanuel was nine), but he also used Das Wohltemperierte Klavier The Well-Tempered Clavier—as teaching material for his students when he joined the faculty of the Thomasschule in Leipzig after leaving Cöthen. Between 1739 and 1744, Bach created a second set of twenty-four

such pieces for his youngest child, Johann Christian (born in 1735). Each of the two books of The Well-Tempered Clavier comprises twenty-four paired preludes and fugues, one in each of the major and minor keys, arranged in ascending order (C major, C minor, C-sharp major, C-sharp minor, etc.).

The Prelude no. 1 in C major that opens book 2, BWV 870, is grand and spacious, a fitting portal to the peerless masterworks that follow. Wanda Landowska, the eminent harpsichordist whose performances and recordings of The Well-Tempered Clavier were prime movers in the revival of interest in baroque music in the 1940s and ’50s, wrote that the companion C major fugue “is of an extreme simplicity. It contains none of the devices we might expect after the magnificence and refinement of the prelude, but its dynamism is extraordinary, its gait vehement, and yet not feverish. The close repetitions of the subject drive us along.”

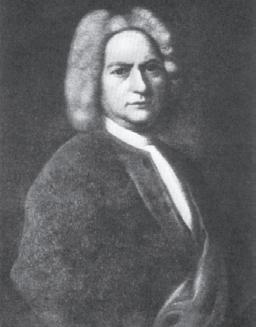

this page: Johann Sebastian Bach, holding a copy of the six-part canon, BWV 1076. Portrait in oil by Elias Gottlob Haussmann (1695–1774), 1748. Bach-Archiv, Leipzig, Germany | opposite page: Bach, circa 1720, from the painting by Johann Jakob Ihle in the Bach Museum, Eisenach, Germany

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH

Partita No. 2 in C Minor, BWV 826

COMPOSED around 1730

Much of Bach’s early activity after arriving in Leipzig in 1723 as the music director for the city’s churches was carried out under the shadow of the memory of his predecessor, Johann Kuhnau, a respected musician and scholar who had published masterly translations of Greek and Hebrew, practiced as a lawyer in the city, and won wide fame for his keyboard music. In 1726, probably the earliest date allowed by the enormous demands of his official position for new sacred vocal music, Bach began a series of keyboard suites that were apparently intended to compete with those of Kuhnau. In addition to helping establish his reputation in Leipzig, these pieces would also provide useful teaching material for the private students he was beginning to draw from among the local university’s scholars.

The Partita no. 1 in B-flat major, BWV 825, issued in 1726, was the first of his compositions to be published, with the exception of two cantatas written during his short tenure in Mühlhausen many years before (1707–08). Bach funded the venture himself, and he even engraved the plates to save money. Bach published an additional partita every

year or so until 1731, when he gathered together the six works and issued them collectively in a volume titled ClavierÜbung (Keyboard Practice), a term he borrowed from the name of Kuhnau’s keyboard suites published in 1689 and 1692. Bach continued his series of Clavier-Übung with three further volumes of vastly different nature: part 2 (1735) contains the Italian Concerto and an Overture in the French Manner; part 3 (1739), for organ, the Catechism Chorale Preludes, several short canonic pieces, and the St. Anne Prelude and Fugue; and part 4 (1742), the incomparable Goldberg Variations.

The term partita was originally applied to pieces in variations form in Italy during the sixteenth century, and the word survived in that context into Bach’s time. The keyboard partitas of the Clavier-Übung, however, are not variations but suites of dances, a form that in France occasionally bore the title of partie, meaning either a movement in a larger work or a musical piece for entertainment. The French term was taken over into German practice in the late seventeenth century as parthie to indicate an instrumental suite, and Bach’s partita seems to have been a corruption of that usage.

The sinfonia that opens the Partita no. 2 in C minor comprises three continuous sections: a slow introductory passage whose pompous dotted

rhythms are borrowed from the French overture, an austere two-voice exercise of sweeping scales supported by a walking bass, and a lively fugue in two parts. The next two movements follow the old custom of pairing a slow dance with a fast one: an allemande (here marked by swiftly flowing rhythms and active

FRÉDÉRIC CHOPIN

dialogue among the voices) is complemented by a courante, a dance type originally including jumping motions. The stately sarabande that follows is balanced by a quick rondeau based on a leaping theme and a closing capriccio whose brilliance rivals some of Bach’s concerto movements.

Born February 22, 1810; Żelazowa-Wola (near Warsaw), Poland

Died October 17, 1849; Paris, France

Nocturne in C Minor, Op. 48, No. 1

COMPOSED 1841

Contemporary accounts of Chopin’s piano playing invariably refer to the extreme delicacy of his touch, the beauty of his tone, and the poetic quality of his expression. These characteristics are faithfully reflected in the twenty-one nocturnes he created between 1827 and 1846. Chopin derived the name and general style for these works from the nocturnes of John Field, the Irish composer-pianist who spent most of his life in Moscow and Paris. Both composers were influenced in the rich harmonies and long melodic lines of their nocturnes by the bel canto

operatic style that was popular at the time, though Chopin’s examples exhibit a greater depth of expression and a wider range of keyboard technique than do those of Field. The introspective moods of the nocturnes pierced to the heart of the romantic sensibility and, along with the waltzes, were Chopin’s most popular works during his lifetime.

The two nocturnes of op. 48 were products of 1841, the time of Chopin’s greatest happiness with George Sand, when he was at the height of his creative powers. They were published in Paris later that year and in Leipzig soon thereafter, with a dedication to Laura Duperré, who inspired the following beguiling description in the memoirs of the composer’s friend Wilhelm von Lenz:

this page: Frédéric Chopin, detail from an unfinished double portrait with George Sand by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), 1838 | opposite page: Chopin, watercolor and ink drawing by fiancée Maria Wodzińska (1819–1896), 1836. National Museum, Warsaw, Poland

I always made my appearance [at Chopin’s apartment] long before the hour of my appointment and waited. Ladies came out, one after another, each more beautiful than the others. On one occasion, there was Mlle Laura Duperré, daughter of Admiral Victor-Guy Duperré [commander of the French forces at the siege of Algiers in 1830], whom Chopin accompanied to the head of the stairs. She was the most beautiful of all and as slender as a palm tree. To her, Chopin dedicated two of his most important

FRÉDÉRIC

CHOPIN

nocturnes [op. 48]; she was his favorite pupil at the time.

Chopin’s high regard for Laura could have found no more fitting vehicle than the Nocturne in C minor, op. 48, no. 1, which musicologist Herbert Weinstock called “Chopin’s major effort in that genre. Here is one of his compositional triumphs.” The work’s breadth, range and intensity of emotion, and peerless control of form and figuration make it one of the supreme masterpieces of the romantic keyboard literature.

Scherzo in B Minor, Op. 20, No. 1

COMPOSED 1830–31

Twenty-year-old

Frédéric Chopin departed Warsaw in November 1830 for his second visit to Vienna, hoping to further his career as a virtuoso pianist by building on the success he had enjoyed in that city a year earlier. His hope was in vain. The Viennese were fickle in their musical tastes, and Chopin had expended his novelty value on his first foray, so he found little response there to his attempts to produce more concerts for himself.

Chopin’s difficulties were exacerbated by the Polish insurrection against Russian oppression that erupted only days after he arrived in Vienna. Conservative Austria was troubled by the anti-monarchial unrest to its north and feared that the czar might petition it for help against the uprising. Polish nationals in Austria were therefore thrown into an uncomfortable situation, and Chopin took considerable care in expressing his patriotic sympathies too openly. He was also worried for the safety of his family and friends in Warsaw and sorely missed a sweetheart for whom he had hatched a passion shortly before leaving. He vacillated about returning home to join the cause, and actually started out on one

occasion, but quickly changed his mind and retreated to Vienna. (Years later, his companion George Sand said that “Chopin is always leaving—tomorrow.”)

On Christmas Day 1830, he wrote to Jan Matuszyński that he was cheered by visiting friends, “but on coming home I vent my rage on the piano. . . . I have a good cry, read, look at things, have a laugh, get into bed, blow out my candle, and dream always about all of you.” In addition, he was earning no money and became depressed enough to write, “To live or die—it is all the same to me.” He wallowed in indecision for another six months, unsure whether to head for London or Munich or Milan, but finally settled on Paris, where he arrived in September 1831. Within a year, he was among the most acclaimed musicians in France.

FRIEDRICH GULDA

Born May 16, 1930; Vienna, Austria

Though Chopin composed little during his difficult time in Vienna in 1830–31, he did write the first of his scherzos, a work of strong, almost violent emotions that may well reflect some of his frustrations of those months. The scherzo, as perfected by Beethoven, has about it an air of humor, or at least joie de vivre, that is reflected in its name, which, in both German and Italian, means joke. There is, however, little lighthearted sentiment in the outer sections of Chopin’s Scherzo no. 1 in B minor (“How is gravity to clothe itself, if jest goes about in dark veils?” Robert Schumann wondered), but the central portions of the piece turn to sweeter thoughts by presenting a lyrical theme derived from the old Polish Christmas song “Sleep, Baby Jesus.”

Died January 27, 2000; Weissenbach am Attersee, Austria

Prelude and Fugue

The “terrorist pianist,” he was called—a title he proudly claimed—though the prodigious life and career of Friedrich Gulda were unconventional and all-embracing rather than simply anarchistic. Gulda studied at the

Grossmann Conservatory as a youngster before entering the Vienna Music Academy in 1942. While he was immersing himself in the classical repertory from Bach to Ravel during his formal studies, he spent evenings with friends playing jazz, defying the prohibition on such music. (A 2007 documentary about his life was titled So What?) Gulda won first prize at the Geneva International Music Competition in 1946 and quickly

established himself as one of the leading virtuosos of his generation, especially renowned for his interpretations of Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Debussy. He made his American debut at Carnegie Hall in 1950 and devoted himself primarily to his international concert career for the following decade, though he increasingly embraced other musical genres as well. During a return to New York for another Carnegie Hall recital in 1956, he made his American jazz debut at the famous Broadway club Birdland and then went to the Newport Jazz Festival. He founded a jazz combo and a big band in the 1960s, initiated a modern jazz competition in Vienna in 1966, established a school for improvisation in 1968 at the International Musikforum in Ossiach, Austria, collaborated regularly with jazz great Chick Corea (including a recording together of Mozart’s Concerto for Two Pianos), and often mixed jazz improvisations with classical repertory in his recitals.

In his playing, teaching, and composing, Gulda continued to range widely across the musical world, counting Martha Argerich and conductor Claudio Abbado among his students while incorporating classical, jazz, folk, rock, techno, and other influences into his original works. Gulda was known as much for his wit as for his iconoclasm, and those characteristics led to the remarkable circumstance of his dying—twice. In March 1999 he

issued a press release announcing his own death. When that news turned out to be somewhat premature, he used the publicity to promote his upcoming concert in Vienna, which he then labeled Resurrection Party. It was sold out. (He explained that he wanted to see how he would be remembered after he was gone. “People have thrown so much muck at me while I’m alive, I don’t want them to chuck it into my grave as well.”)

The real thing happened, from a heart attack, on January 27, 2000, the anniversary of Mozart’s birth.

The music of Johann Sebastian Bach was a focus for Gulda throughout his parallel careers as performer, historical scholar, and composer. He programmed Bach regularly, recorded both books of The Well-Tempered Clavier (including several on the tiny-voiced clavichord, Bach’s second favorite instrument after organ, whose keys directly connect the player’s finger to the string with no mechanical enhancement of the sound), and incorporated technical and formal elements from it into his works. The prelude and fugue of 1965 was Gulda’s tribute to the forty-eight such works comprising Bach’s monumental Well-Tempered Clavier, though Gulda filtered the improvisatory character of the prelude and the gnarly double fugue through the rhythms, harmonies, and character of his own jazz style, even allowing the performer freedom to improvise the work’s ending.

opposite page: Photograph of Friedrich Gulda by Franz Hubmann, 1967. Getty Images

HAYATO SUMINO

Born July 14, 1995; Chiba, Japan

New Birth (after Chopin)

Recollection (after Chopin)

COMPOSED 2022

New Birth was inspired by Chopin’s Etude in C major, op. 10, no. 1, adopting its glittering

NIKOLAI KAPUSTIN

figuration to accompany Sumino’s own broad melody.

Recollection is adapted from Chopin’s Ballade no. 2 in F major, op. 38, transforming its peaceful, pastoral character into something dreamy and ethereal, but retaining a contrasting episode at its center.

Born November 22, 1937; Gorlovka, Donetsk Province, Ukraine

Died July 2, 2020; Moscow, Russia

Selections from Eight Concert Etudes, Op. 40

COMPOSED 1984

The fusion of jazz and classical styles that was seeded in 1924 by George Gershwin’s epochal Rhapsody in Blue is usually thought to be a Western phenomenon, but Russian composer and pianist Nikolai Kapustin proved that such a cross-genre musical view has had a far wider influence. Kapustin

began playing piano at age seven and composing at thirteen, and he attended the Moscow Conservatory as a piano student of the eminent Alexander Goldenweiser, who grounded him thoroughly in the Russian classical traditions. Kapustin studied jazz along with the classics while in school, and made his formal debut in 1957 at the Sixth International Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow, playing his own concertino, op. 1, which he called “a very jazzy piece.” For the next three decades,

from top: Hayato Sumino, photo by Dario Acosta | Nikolai Kapustin, photo by Peter Anderson, Schott-Music

he performed, toured, and recorded with several leading Russian big bands and light-music orchestras as well as with his own quintet while composing in a manner he described as “a fusion between classical forms and a jazzy idiom.”

In the mid-1980s, when he gave up playing in public, Kapustin lived modestly in a Moscow flat, composing steadily and traveling little but frequently recording his own music. His works—fifteen piano sonatas; concertos for piano, trumpet, saxophone, double bass, cello, and violin; orchestra and big band pieces; chamber music; many compositions for solo piano—were almost unknown outside Russia until British pianist Steven Osborne released a recording of the first two sonatas and 24 Preludes in Jazz Style in 2000; Marc-André Hamelin’s 2004 CD was the first of an increasing number of subsequent recordings now available in the West, several of them by Kapustin himself. Eckart Runge, cellist of Germany’s Artemis String Quartet, which performed Kapustin’s 1989 String Quartet internationally, noted that the composer wrote in an

alluring, somewhat disturbing and uniquely genuine musical language: a complex, virtuosic blend of rhythmic and harmonic elements of jazz, blues, soul, rock, and popular music with an almost contradictory conservatism in the choice of classical forms, suffused with expression ranging from lighthearted to biting humor as well as a deep, dark Russian ambience.

Kapustin’s Eight Concert Etudes of 1984 encompass a broad range of styles and expressive states that all provide formidable technical challenges for the performer. In his liner notes for MarcAndré Hamelin’s Hyperion recording of Kapustin’s piano music, award-winning composer, jazz and classical pianist, and producer Jed Distler wrote that the Etude no. 1 (Prelude), “transports us to the crowded streets of Rio de Janeiro at the height of Carnival season. Yet for all the music’s giddy groove and melodic uplift, its tempestuous, Chopinesque figurations never relent.”

Reverie (no. 2) is wistful and evanescent, with ceaselessly fluttering figurations that lend the music a certain urgency, notably in its central episode.

The toccata was an eighteenthcentury genre that demonstrated a keyboardist’s virtuosity (the name comes from toccare, Italian for “to touch,” suggesting the fleet movement of the fingers across the keys), and Kapustin’s Toccatina (no. 3, Little Toccata) is a showpiece of digital dexterity that serves to create the impression of swift, muscular movement and big-city energy.

The Intermezzo (no. 7) starts out in an easy swing style before moving onto a driving stride passage featuring long chains of parallel notes in sweet intervals of a third. Swing and stride both take a quick bow in the closing pages.

Finale (no. 8) closes the etudes with a scintillating display of piano virtuosity.

Three Nocturnes

COMPOSED 2024

In the liner notes for his 2024 CD Human Universe (Sony Classical), Hayato Sumino wrote,

[The] Three Nocturnes are based on my improvisations in different

MAURICE RAVEL

Born March 7, 1875; Ciboure, France

Died December 28, 1937; Paris, France

cities around the world: “Pre Rain” was composed in South Korea in winter—it was very cold, half snowing, half raining, so the piece is kind of like that. “After Dawn” comes from my hometown in Japan, where I saw the sun rising while I was jet-lagged. I improvised “Once in a Blue Moon” in the South of France, in the deep countryside.

Boléro (Arranged by Hayato Sumino)

COMPOSED 1928

Ravel originated what he once called his “danse lascive” at the suggestion of Ida Rubinstein, the famed ballerina who also inspired works from Debussy, Honegger, and Stravinsky. Rubinstein’s balletic interpretation of Boléro, set in a rustic Spanish tavern, portrayed a voluptuous dancer whose stomps and whirls atop a table incite the men in the bar to mounting fervor. With growing intensity, they join in her dance

until, in a brilliant coup de théâtre, knives are drawn and violence flares onstage at the moment near the end where the music modulates, breathtakingly, from the key of C to the key of E. So stirring was the music and the ballerina’s suggestive dancing at the premiere that a near-riot ensued between audience and performers, and Miss Rubinstein narrowly escaped injury. Ravel wrote,

Boléro constitutes an experiment in a very special and limited direction. It consists wholly of one long, very gradual crescendo. There are no

contrasts, there is practically no invention except the plan and the manner of execution. The themes are altogether impersonal . . . folk tunes of the usual Spanish-Arabian kind, and (whatever may have been said to the contrary) the writing is simple and straightforward throughout, without the slightest attempt at virtuosity.

Hayato Sumino scored his arrangement of Ravel’s Boléro for both grand and upright pianos, with felt placed between some of the upright’s strings and hammers to modify their sound. Sumino, who holds a degree in science and engineering from the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Information Science and Technology, and also studied music information processing technology and artificial intelligence in Paris at IRCAM (French Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music), wrote of his arrangement of Boléro,

As a scientific researcher, you’re always surveying what people have done before and trying to find something new. And now that I am a musician, my mind is influenced by what I experienced when I was a researcher, trying to find something new based on work from the past. For me, when I express music, I always think about how I can express something more than just ordinary human feelings.”

Richard E. Rodda, a former faculty member at Case Western Reserve University and the Cleveland Institute of Music, provides program notes for many American orchestras, concert series, and festivals.

opposite page, from top: Hayato Sumino, photo by Dario Acosta | Maurice Ravel, portrait, ca. 1925. Bibliothèque nationale de France | this page: Mme Ida Rubinstein, painting by Léon Bakst (1866–1924), 1917. The Chester Dale Collection, Bequest of Chester Dale, 1962, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City