25 26 SEASON

We’ve

25 26 SEASON

We’ve

We’re honored they’ve done the same for us.

Ranked

We believe the connection between you and your advisor is everything. It starts with a handshake and a simple conversation, then grows as your advisor takes the time to learn what matters most–your needs, your concerns, your life’s ambitions. By investing in relationships, Raymond James has built a firm where simple beginnings can lead to boundless potential.

CHICAGO SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA

KLAUS MÄKELÄ Zell Music Director Designate | RICCARDO MUTI Music Director Emeritus for Life

Thursday, November 13, 2025, at 7:30

Friday, November 14, 2025, at 7:30

Saturday, November 15, 2025, at 7:30

Robert Chen Leader and Violin

MOZART Divertimento in B-flat Major, K. 137

Andante

Allegro di molto

Allegro assai

ROBERT CHEN

BEETHOVEN String Quartet in F Minor, Op. 95 (Serioso) (orch. Mahler)

Allegro con brio

Allegretto ma non troppo

Allegro assai vivace ma serioso

Larghetto espressivo—Allegretto agitato

ROBERT CHEN

INTERMISSION

VIVALDI The Four Seasons

Concerto in E Major (Spring)

Allegro

Largo e pianissimo

Allegro

Concerto in G Minor (Summer)

Allegro ma non molto

Adagio

Presto

Concerto in F Major (Autumn)

Allegro

Adagio molto

Allegro

Concerto in F Minor (Winter)

Allegro non molto

Largo

Allegro

ROBERT CHEN

These performances are generously sponsored by the Randy L. and Melvin R. Berlin Family Fund for the Canon.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association acknowledges support from the Illinois Arts Council.

These performances are generously sponsored by the Randy L. and Melvin R. Berlin Family Fund for the Canon.

COMMENTS by Phillip Huscher

WOLFGANG

MOZART

Born January 27, 1756; Salzburg, Austria

Died December 5, 1791; Vienna, Austria

After returning to Salzburg from his extraordinarily successful, career-changing first tour of Italy, the young Mozart was barely home for five months before he and his father set off for Milan late in the summer of 1771. Italy had a wonderful effect on Wolfgang. He was introduced to new musical styles and exposed to new ideas— and, in the manner of a prodigy destined to fulfill his youthful promise, he absorbed them and made them his own. He received much of his musical education abroad and many of his early works were written on the road. By the time Mozart arrived back in Salzburg in December 1771, after his second Italian adventure, he had already begun to make his mark in the fields of opera, oratorio, symphony, and sonata, and

COMPOSED 1772

FIRST PERFORMANCE unknown

INSTRUMENTATION strings

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME 12 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

January 27, 28, 29, and February 1, 2011. Mitsuko Uchida conductor and piano

he was poised to transform the piano concerto. And he was just fifteen years old.

Within a few weeks of his return to Salzburg, which seemed more provincial each time he came home, Mozart composed three works for stringed instruments. The autographs are titled divertimentos, but the handwriting isn’t Mozart’s. It is possible that Mozart was thinking of just one player to a part, which would make these delightful scores early efforts at writing string quartets. (Mozart’s first “official” string quartets were composed a few months later, as a cycle of six works.) Nevertheless, because of their divertimento designation and their scoring for violins, violas, and basses, rather than the cellos of conventional string quartet makeup, they have most often been played by string orchestras.

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN

Born December 16, 1770; Bonn, Germany

Died March 26, 1827; Vienna, Austria

The Divertimento in B-flat major—the second in the set—has three movements, but in an unusual arrangement, with the slowest movement, a lovely andante, placed before two faster ones. A typically Italian grace and charm pervade the entire piece, suggesting that the ideas for this music came to Mozart—if they weren’t in fact written down—while he was still in Milan.

It is possible that this is one of the quartets Leopold unsuccessfully peddled to the publishing house of Breitkopf and Härtel in February 1772. The prestigious Viennese company’s lack of interest in an unknown teenage composer is hardly surprising. In fact, during Mozart’s lifetime, only some 130 of the 626 works in Köchel’s catalog were printed and sold.

Beethoven was Mahler’s passport to the Vienna Conservatory (he played the Les adieux Sonata at his audition) and years later, when he was one of the leading composer-conductors of the day, Mahler claimed that Beethoven and Wagner were his only idols—“after them, nobody,” he said. But in our authenticity-conscious age today, when total fidelity to the score is the favored stance, the way that Mahler showed his esteem for their music is sometimes hard to swallow. When he conducted

COMPOSED

1810, for string quartet; 1898, arranged by Mahler for string orchestra

FIRST PERFORMANCE

January 15, 1899; Vienna, Austria. The composer conducting.

APPROXIMATE

PERFORMANCE TIME

26 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

November 28, 29, 30, and December 2, 1997, Orchestra Hall. Pinchas Zukerman conducting

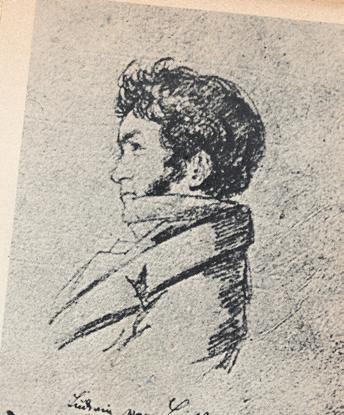

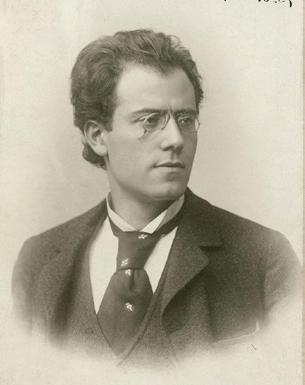

previous page, from top : Wolfgang Mozart, miniature portrait on ivory attributed to Austrian Italian artist Martin Knoller (1725–1804), 1773 | View of the Naviglio and the Church of San Marco in Milan. Painting in oil by Angelo Inganni (1807–1880), 1835. While in Italy in 1771, Mozart and his father were provided lodging at the Monastery of San Marco at the invitation of the Augustinian monks of Salzburg. | this page, from left : Ludwig van Beethoven, pencil sketch by Ludwig Ferdinand Schnorr von Carolsfeld (1788–1853), ca. 1808–09 | Gustav Mahler, cabinet photograph by Leonhard Berlin-Bieber (1841–1931), 1893. Berlin, Germany

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony, for example, he sometimes added pounding timpani to the famous opening and asked for an extra piccolo and an E-flat clarinet in the finale. For a performance of the Ninth in 1895, he composed a brand-new horn part for the trio.

Even then, Mahler was occasionally criticized for his unscrupulous dealings with Beethoven’s music—one critic referred to a performance of the Ninth as a “transcription”—and he ultimately felt compelled to issue a statement defending himself. Above all, he claimed, he was “determined not to sacrifice one iota of what the Master demands and did not allow any particle to become lost in the welter of sound.” Listeners then, as today, often failed to understand that Mahler retouched Beethoven’s scores with extraordinary care and after long thought, and only out of his intense passion for clarity of sound.

The issue came to a head when, on his concert with the Vienna Philharmonic scheduled for January 15, 1899, Mahler decided to include Beethoven’s F minor string quartet (known as Serioso) played by the orchestra’s full string section. Writing in the newspaper two days after the concert, the influential critic Eduard Hanslick quoted Mahler on his intentions:

Chamber music by definition is intended for performance in a domestic setting. It is really only enjoyed by the performers. Once it is transferred to the concert hall, the intimacy is lost; but more still is lost: in a large space the four parts are weakened and do not reach the listener with the strength intended by the composer.

Mahler was convinced that “the sound volume of a work must be adapted to the dimensions of the hall in which it is to be given,” and he even went so far as to insist that in a small theater he would present Wagner’s Ring cycle with a reduced orchestra, “just as in an enormous theater I would reinforce it.”

Mahler knew that his rendition of the Beethoven quartet would be controversial.

Before the concert, he told Hanslick, “Today I am fully prepared for a fight; you’ll see that all the philistines will rise up as one man against this performance of the quartet instead of being curious and pleased at hearing it like this for once.” In fact, the booing began before the orchestra played a note. According to the composer’s friend Natalie Bauer-Lechner, the first movement, which passed “like a tempest,” was greeted with deathly silence. The second movement brought both applause and boos, and finally Mahler sent one of the musicians into the audience to ask two particularly disruptive men to leave. At the end of the performance the audience reaction was decidedly cool—the public “refused to accept this offering from two giants, one dead and one alive,” as Natalie put it.

It is hard to quibble with Mahler’s choice, for the F minor string quartet is among Beethoven’s finest achievements, truly symphonic in the rigor and intensity of its language. This is one of the few works to which Beethoven himself gave a name, and his title, Serioso, only underlines the work’s substance and significance. The entire quartet is remarkably concentrated and tightly packed. Beethoven composed it in 1810, shortly after the Emperor Concerto and at the same time he was working on the music for Goethe’s Egmont. In this work, as in few others, we see a Beethoven who seems possessed to a degree that was unexpected in music then. This was to be his last quartet for twelve years—until 1822, when he began his extraordinary final five, the so-called late quartets.

The first movement is unusually explosive and driven, with quicksilver shifts of mood and tempo—from fortissimo scales to gently singing melodies, and from unexpected silence to fierce outbursts. The second movement offers neither rest nor relaxation from the first; it is not a real slow movement in tempo or function. Beethoven’s marking for the third movement— Allegro assai vivace ma serioso (quick, but serious)—ensures that this is no frivolous scherzo; even the trio, which normally offers some relief, sounds uneasy and restless. The pace slackens at last in the slow introduction to the finale,

but the mood remains intense throughout. Then, in the dazzling and exhilarating coda, Beethoven seems almost desperate to flee, to

Born March 4, 1678; Venice, Italy

Died July 28, 1741; Vienna, Austria

Concerto in E Major, RV 269 (Spring)

Concerto in G Minor, RV 315 (Summer)

Concerto in F Major, RV 293 (Autumn)

Concerto in F Minor, RV 297 (Winter)

leave the dark and troubled world of the quartet behind. The effect, sudden and unexpected, is extraordinary.

COMPOSED ca. early 1720s

FIRST PERFORMANCE date unknown

INSTRUMENTATION

solo violin with harpsichord and strings

At these performances, Mark Shuldiner plays harpsichord.

APPROXIMATE

The Four Seasons, one of the most familiar works of classical music today, was almost unknown when Louis Kaufman, a Portland-born violinist, recorded these four concertos in Carnegie Hall during the last two days of 1947—finishing up before midnight on New Year’s Eve in order to avoid a musicians’ strike. The concertmaster for more than four hundred soundtrack recordings, including Gone with the Wind and Casablanca, Kaufman had a knack for getting in on the ground floor of popular trends: two decades earlier, he was the first person to buy a painting by American master Milton Avery—he paid just $25. Kaufman’s recording of The Four Seasons, which quickly became a best seller, coincided with a renewed interest in Vivaldi in scholarly circles as well: the Italian publishing house of Ricordi launched the complete edition of Vivaldi’s instrumental works in 1947; Marc Pincherle’s definitive study was published the next year. Soon, just as Avery’s paintings had begun to command big prices, the Vivaldi revival was in full swing. (The Chicago Symphony Orchestra programmed The Four Seasons for the first time in 1955.)

The Four Seasons eventually became the most frequently recorded piece of music in the repertory, as well as a ubiquitous background presence in upscale hotel lobbies, gourmet food shops, and coffee bars; and a ridiculously overplayed selection in soundtracks for movies (Pretty Woman; I, Tonya) and TV series (The Sopranos, The Crown). For a work that has so thoroughly infiltrated the public consciousness, however, we know surprisingly little about its origins.

PERFORMANCE TIME 39 minutes

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

November 3 and 4, 1955, Orchestra Hall. John Weicher as soloist, Carlo Maria Giulini conducting July 23, 2000, Ravinia Festival. Itzhak Perlman conducting from the violin (Summer)

July 13, 2003, Ravinia Festival. Pekka Kuusisto, Jimmy Bosch, and Jimmy Bosch’s Salsa Dura as soloists; Nicholas McGegan conducting (arranged by Jeff Lederer)

MOST RECENT

CSO PERFORMANCES

August 12, 2016, Ravinia Festival. Joshua Bell conducting from the violin (Spring and Summer)

October 17, 18, 19, and 20, 2019, Orchestra Hall. Julian Rachlin conducting from the violin

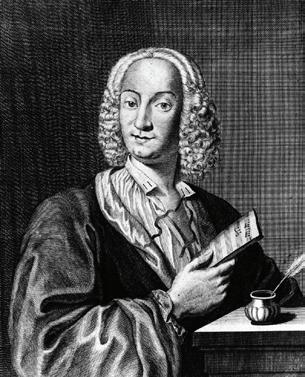

this page : Antonio Vivaldi, engraving, 1725, by François Morellon de la Cave (1696–1768)

opposite page : Detail from The Four Seasons by Marc Chagall (1887–1985), a mosaic composed of six scenes representing the city of Chicago through the cycle of the four seasons. A gift to the City of Chicago from the Prince Charitable Trusts, dedicated in 1974. Chase Tower Plaza in the Loop

The four violin concertos we know as The Four Seasons were first published in Amsterdam in 1725, in a collection of twelve concertos entitled II cimento dell’armonia e dell’inventione (The contest between harmony and invention), which was Vivaldi’s op. 8. But apparently The Four Seasons wasn’t new: in his dedication to Count Wenzel Morzin, Vivaldi explains that he has included these four concertos, which “found generous favor with Your Illustrious Lordship quite a long time ago,” in an improved version, complete with illustrative sonnets. It’s unclear when Vivaldi wrote the concertos, and whether it was he who played them for Morzin originally. The 1725 edition includes not only four sonnets, one per season, that were most likely written by Vivaldi himself but also cue letters and descriptive captions printed directly in the score that link lines of the poems with their musical realization.

It is the scene painting in these concertos that has caused the most comment in our time, as it surely must have in Vivaldi’s. Although there is a strong tradition of Italian program music before Vivaldi, The Four Seasons stands alone in the abundance, brilliance, and ingenuity of

its pictorial writing: birds chirp, leaves rustle, thunder rattles, a dog barks, winds howl. There is nothing quite like it in music again until Beethoven’s nightingale, quail, and cuckoo begin to sing in the Pastoral Symphony. As Beethoven says, writing nearly a century later, “Even without description one will recognize the whole,” although in Vivaldi’s concertos, there is a strict correspondence between the explanatory poems and the music; each sonnet is a blow-by-blow summary of the action—the first few lines outlining the first movement, as little as a single line setting the scene for the slow movement, and the rest of the poem describing the finale. Vivaldi’s sonnets, are, in essence, the first true program notes in the history of music—a hundred years before the ever-innovative Berlioz couldn’t make up his mind whether listeners needed to read his commentary on the Symphonie fantastique. Vivaldi wasn’t ambivalent: he wanted Count Morzin to read the sonnets and listen to his music.

Phillip Huscher has been the program annotator for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra since 1987.

Spring has arrived merrily.

The birds hail her with happy song. And, meanwhile, at the breath of the Zephyrs, The streams flow with a sweet murmur:

Thunder and lightning, chosen to proclaim her, Come covering the sky with a black mantle, And then, when these fall silent, the little birds Return once more to their melodious incantation:

And so, on the pleasant, flowery meadow, To the welcome murmuring of fronds and trees, The goatherd sleeps with his trusty dog beside him.

To the festive sound of a shepherd’s bagpipe, Nymphs and shepherds dance beneath the beloved roof

At the joyful appearance of spring.

Beneath the harsh season inflamed by the sun, Man languishes, the flock languishes, and the pine tree burns;

The cuckoo unleashes its voice and, so soon as it is heard,

The turtle dove sings and the goldfinch too. Sweet Zephyrus blows, but Boreas suddenly Opens a dispute with his neighbor, And the shepherd weeps, for he fears A fierce storm looming—and his destiny; The fear of lightning and fierce thunder And the furious swarm of flies and blowflies Deprives his weary limbs of repose. Oh alas! His fears are only too true.

The sky thunders, flares, and with hailstones Severs the heads of the proud grain crops.

The peasant celebrates in dance and song

The sweet pleasure of the rich harvest And, fired by Bacchus’s liquor, Many end their enjoyment in slumber.

The air, which fresher now, lends contentment, And the season which invites so many

To the great pleasure of sweetest slumber, Make each one abandon dance and song.

At the new dawn the hunters set out on the hunt

With horns, guns, and dogs.

The wild beast flees, and they follow its track; Already bewildered, and wearied by the great noise

Of the guns and dogs, wounded, It threatens weakly to escape, but, overwhelmed, dies.

To shiver, frozen, amid icy snows, At the harsh wind’s chill breath;

To run, stamping one’s feet at every moment; With one’s teeth chattering on account of the excessive cold;

To pass the days of calm and contentment by the fireside

While the rain outside drenches a hundred others;

To walk on the ice, and with slow steps

To move about cautiously for fear of falling;

To go fast, slip, fall to the ground; To go on the ice again and run fast

Until the ice cracks and breaks open; To hear, as they sally forth through the ironclad gates, Sirocco, Boreas, and all the winds at war. This is winter, but of a kind to bring joy.

Paul Everett, Vivaldi: The Four Seasons and Other Concertos, Op. 8. English language translation, Cambridge University Press, 1996

Program Annotator Phillip Huscher talks with Robert Chen about this week’s program, in which he is both soloist and conductor.

As concertmaster of this orchestra for more than twenty-five years, you have often played important solos with it, but do you recall how you felt when you conducted the Orchestra for the first time?

Nervous. I was very hesitant to “conduct” my colleagues, since I had only known them from the perspective of being their leader. What I realized is that music making is a group effort and the experience was actually quite empowering for all of us. I have Cristina Rocca to thank for her persistence in not taking no for an answer. She must have asked me to do this type of program at least ten times before I said yes.

How do you balance attention to your solo line, which is virtuosic and demanding, with all the interpretive choices it takes to bring the score to life for the whole ensemble?

I lean on my colleagues. It’s a group of musicians very familiar and dear to me. I trust them to contribute to the endeavor.

You know Beethoven’s score from playing it as a string quartet. How different is Mahler’s arrangement?

It has basses added to reinforce the cello line. This and a full string section creates a much richer sonority in the score.

Because of the scale of Mahler’s arrangement, do you need to make different tempo choices than you would if you were playing the original quartet?

Of course, it’s like driving a bus versus driving a race car. Certain corners require a slower speed for safety. This will be my first time doing this piece with any orchestra. Ideally, I would like to keep the same character and tension without sacrificing too much on tempo choices.

I lean on my colleagues. It’s a group of musicians very familiar and dear to me. I trust them to contribute to the endeavor.”

The Four Seasons has become one of music’s most popular works in the past few decades. What was your introduction to the piece?

When I was growing up in Taiwan, it was very widespread in popular culture. I remember bits and pieces of it being used for TV commercials, and of course, the requisite elevator music. The first time I played it was as part of the Orpheus Chamber Orchestra with Gil Shaham as soloist on tour in Japan. The first time I performed it as soloist was with the Northbrook Symphony Orchestra here in Chicago. That’s actually the only time I’ve played the entire Four Seasons.

The violin you play was made just a few years before Vivaldi wrote The Four Seasons. Are you concerned about trying to get near to the sound one might have heard in Vivaldi’s own day?

I don’t know. I wasn’t there. While I enjoy historically informed performances, we are in a completely different era both instrumentally and acoustically. Orchestra Hall is a rather large space, and we have to take that into account when making interpretive decisions. The United States of America wasn’t even a country yet. I will experiment with different sounds, articulations, and ornamentation in the spirit of the 1700s.

ORCHESTRA

Fabio Biondi, conductor/violin

Gina DiBello, violin

Concertos by the Italian master, those he inspired, and those who inspired him.

NORTH SHORE CENTER SKOKIE

SUNDAY, APR 12, 7:30PM

HARRIS THEATER CHICAGO

MONDAY, APR 13, 7:30PM

FIRST CSO PERFORMANCES

June 25, 2000, Ravinia Festival. Saint-Saëns’s La muse et le poète with Yo-Yo Ma, Christoph Eschenbach conducting

November 30, December 1, 2, and 3, 2000, Orchestra Hall. Mozart’s Violin Concerto no. 4, Daniel Barenboim conducting

MOST RECENT CSO PERFORMANCES

August 7, 2021, Ravinia Festival. Eryximachus (third movement) from Bernstein’s Serenade, Teddy Abrams conducting

March 28, 29, and April 2, 2024, Orchestra Hall. J.S. Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto no. 3, Violin Concerto no. 2, Concerto for Oboe and Violin in C Minor with William Welter, and Orchestral Suite no. 1; and C.P.E. Bach’s Sinfonia in E-flat major; conducting from the violin

Robert Chen celebrates his twenty-sixth season as concertmaster of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra. During his tenure, he has been featured as soloist with many world-renowned conductors, including Riccardo Muti, Daniel Barenboim, Pierre Boulez, and Bernard Haitink. He gave the CSO premiere of György Ligeti’s Violin Concerto, Elliott Carter’s Violin Concerto, and Witold Lutosławski’s Chain Two, as well as the world

premiere of Augusta Read Thomas’s Astral Canticle. In addition to his duties as concertmaster, Chen enjoys a solo career that takes him around the world. Most recently, he toured Europe as soloist-conductor with the National Taiwan Symphony Orchestra. In addition, Chen has been an artistic partner of the Northbrook Symphony Orchestra since 2019.

An avid chamber musician, Chen has partnered with many of the most important musicians of our time. He is a past participant in the Marlboro Music Festival and a member of the Chen Quartet. Prior to joining the CSO, Robert Chen won first prize in the Hanover International Violin Competition. He consequently recorded Tchaikovsky’s violin works with the NDR Orchestra of Hanover for the Berlin Classics label.

Robert Chen began his violin studies in Taiwan at the age of seven and continued them with Robert Lipsett when his family immigrated to Los Angeles in 1979. While in Los Angeles, he participated in Jascha Heifetz’s master classes. Chen received bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the Juilliard School, where he was a student of Dorothy DeLay and Masao Kawasaki.

The Chen Quartet, composed of the Chen family, is an integral part of his musical activity outside the CSO. They serve many of the Chicago area’s retirement communities as well as casual and formal performance venues. The Chen Quartet is featured regularly on Live from WFMT and at Bargemusic.

Discover the benefits of making a legacy gift to your Chicago Symphony Orchestra

“The symphony is a major part of my life, and I want to see it continue for generations so that others may enjoy the beauty of classical music and hear the best orchestra in the world.”

— Merle Jacob

Named in honor of the founding music director of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, the Theodore Thomas Society recognizes individuals who have included the Chicago Symphony Orchestra in their will, trust or beneficiary designation.

Contact Karen Bippus at 312-294-3150 or visit cso.org/PlannedGiving for more information.

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra—consistently hailed as one of the world’s best—marks its 135th season in 2025–26. The ensemble’s history began in 1889, when Theodore Thomas, the leading conductor in America and a recognized music pioneer, was invited by Chicago businessman Charles Norman Fay to establish a symphony orchestra. Thomas’s aim to build a permanent orchestra of the highest quality was realized at the first concerts in October 1891 in the Auditorium Theatre. Thomas served as music director until his death in January 1905, just three weeks after the dedication of Orchestra Hall, the Orchestra’s permanent home designed by Daniel Burnham.

Frederick Stock, recruited by Thomas to the viola section in 1895, became assistant conductor in 1899 and succeeded the Orchestra’s founder. His tenure lasted thirty-seven years, from 1905 to 1942—the longest of the Orchestra’s music directors. Stock founded the Civic Orchestra of Chicago— the first training orchestra in the U.S. affiliated with a major orchestra—in 1919, established youth auditions, organized the first subscription concerts especially for children, and began a series of popular concerts.

Three conductors headed the Orchestra during the following decade: Désiré Defauw was music director from 1943 to 1947, Artur Rodzinski in 1947–48, and Rafael Kubelík from 1950 to 1953. The next ten years belonged to Fritz Reiner, whose recordings with the CSO are still considered hallmarks. Reiner invited Margaret Hillis to form the Chicago Symphony Chorus in 1957. For five seasons from 1963 to 1968, Jean Martinon held the position of music director.

Sir Georg Solti, the Orchestra’s eighth music director, served from 1969 until 1991. His arrival launched one of the most successful musical partnerships of our time. The CSO made its first overseas tour to Europe in 1971 under his direction and released numerous award-winning recordings. Beginning in 1991, Solti held the title of music director laureate and returned to conduct the Orchestra each season until his death in September 1997.

Daniel Barenboim became ninth music director in 1991, a position he held until 2006. His tenure was distinguished by the opening of Symphony Center in 1997, appearances with the Orchestra in the dual role of pianist and conductor, and twenty-one international tours. Appointed by Barenboim in 1994 as the Chorus’s second director, Duain Wolfe served until his retirement in 2022.

In 2010, Riccardo Muti became the Orchestra’s tenth music director. During his tenure, the Orchestra deepened its engagement with the Chicago community, nurtured its legacy while supporting a new generation of musicians and composers, and collaborated with visionary artists. In September 2023, Muti became music director emeritus for life.

In April 2024, Finnish conductor Klaus Mäkelä was announced as the Orchestra’s eleventh music director and will begin an initial five-year tenure as Zell Music Director in September 2027. In July 2025, Donald Palumbo became the third director of the Chicago Symphony Chorus.

Carlo Maria Giulini was named the Orchestra’s first principal guest conductor in 1969, serving until 1972; Claudio Abbado held the position from 1982 to 1985. Pierre Boulez was appointed as principal guest conductor in 1995 and was named Helen Regenstein Conductor Emeritus in 2006, a position he held until his death in January 2016. From 2006 to 2010, Bernard Haitink was the Orchestra’s first principal conductor.

Mezzo-soprano Joyce DiDonato is the CSO’s Artist-in-Residence for the 2025–26 season.

The Orchestra first performed at Ravinia Park in 1905 and appeared frequently through August 1931, after which the park was closed for most of the Great Depression. In August 1936, the Orchestra helped to inaugurate the first season of the Ravinia Festival, and it has been in residence nearly every summer since.

Since 1916, recording has been a significant part of the Orchestra’s activities. Recordings by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Chorus— including recent releases on CSO Resound, the Orchestra’s recording label launched in 2007— have earned sixty-five Grammy awards from the Recording Academy.

Discover more about the musicians, concerts, and generous supporters of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association online, at cso.org.

Find articles and program notes, listen to CSOradio, and watch CSOtv at Experience CSO.

cso.org/experience

Get involved with our many volunteer and affiliate groups.

cso.org/getinvolved

Connect with us on social @chicagosymphony

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Board of Trustees

OFFICERS

Mary Louise Gorno Chair

Chester A. Gougis Vice Chair

Steven Shebik Vice Chair

Helen Zell Vice Chair

Renée Metcalf Treasurer

Jeff Alexander President

Kristine Stassen Secretary of the Board

Stacie M. Frank Assistant Treasurer

Dale Hedding Vice President for Development

Chicago Symphony Orchestra Association Administration

SENIOR LEADERSHIP

Jeff Alexander President

Stacie M. Frank Vice President & Chief Financial Officer, Finance and Administration

Dale Hedding Vice President, Development

Ryan Lewis Vice President, Sales and Marketing

Vanessa Moss Vice President, Orchestra and Building Operations

Cristina Rocca Vice President, Artistic Administration

The Richard and Mary L. Gray Chair

Eileen Chambers Director, Institutional Communications

Jonathan McCormick Managing Director, Negaunee Music Institute at the CSO

Visit cso.org/csoa to view a complete listing of the CSOA Board of Trustees and Administration.

For complete listings of our generous supporters, please visit the Richard and Helen Thomas Donor Gallery.

cso.org/donorgallery

Klaus Mäkelä Zell Music Director Designate

Joyce DiDonato Artist-in-Residence

VIOLINS

Robert Chen Concertmaster

The Louis C. Sudler

Chair, endowed by an

anonymous benefactor

Stephanie Jeong

Associate Concertmaster

The Cathy and Bill Osborn Chair

David Taylor*

Assistant Concertmaster

The Ling Z. and Michael C.

Markovitz Chair

Yuan-Qing Yu*

Assistant Concertmaster

So Young Bae

Cornelius Chiu

Gina DiBello

Kozue Funakoshi

Russell Hershow

Qing Hou

Gabriela Lara

Matous Michal

Simon Michal

Sando Shia

Susan Synnestvedt

Rong-Yan Tang

Baird Dodge Principal

Danny Yehun Jin

Assistant Principal

Lei Hou

Ni Mei

Hermine Gagné

Rachel Goldstein

Mihaela Ionescu

Melanie Kupchynsky §

Wendy Koons Meir

Ronald Satkiewicz ‡

Florence Schwartz

VIOLAS

Teng Li Principal

The Paul Hindemith Principal Viola Chair

Catherine Brubaker

Youming Chen

Sunghee Choi

Wei-Ting Kuo

Danny Lai

Weijing Michal

Diane Mues

Lawrence Neuman

Max Raimi

John Sharp Principal

The Eloise W. Martin Chair

Kenneth Olsen

Assistant Principal

The Adele Gidwitz Chair

Karen Basrak §

The Joseph A. and Cecile Renaud Gorno Chair

Richard Hirschl

Olivia Jakyoung Huh

Daniel Katz

Katinka Kleijn

Brant Taylor

The Ann Blickensderfer and Roger Blickensderfer Chair

BASSES

Alexander Hanna Principal

The David and Mary Winton

Green Principal Bass Chair

Alexander Horton

Assistant Principal

Daniel Carson

Ian Hallas

Robert Kassinger

Mark Kraemer

Stephen Lester

Bradley Opland

Andrew Sommer

FLUTES

Stefán Ragnar Höskuldsson § Principal

The Erika and Dietrich M.

Gross Principal Flute Chair

Emma Gerstein

Jennifer Gunn

PICCOLO

Jennifer Gunn

The Dora and John Aalbregtse Piccolo Chair

OBOES

William Welter Principal

Lora Schaefer

Assistant Principal

The Gilchrist Foundation,

Jocelyn Gilchrist Chair

Scott Hostetler

ENGLISH HORN

Scott Hostetler

Riccardo Muti Music Director Emeritus for Life

CLARINETS

Stephen Williamson Principal

John Bruce Yeh

Assistant Principal

The Governing

Members Chair

Gregory Smith

E-FLAT CLARINET

John Bruce Yeh

BASSOONS

Keith Buncke Principal

William Buchman

Assistant Principal

Miles Maner

HORNS

Mark Almond Principal

James Smelser

David Griffin

Oto Carrillo

Susanna Gaunt

Daniel Gingrich ‡

TRUMPETS

Esteban Batallán Principal

The Adolph Herseth Principal Trumpet Chair, endowed by an anonymous benefactor

John Hagstrom

The Bleck Family Chair

Tage Larsen

TROMBONES

Timothy Higgins Principal

The Lisa and Paul Wiggin

Principal Trombone Chair

Michael Mulcahy

Charles Vernon

BASS TROMBONE

Charles Vernon

TUBA

Gene Pokorny Principal

The Arnold Jacobs Principal Tuba Chair, endowed by Christine Querfeld

* Assistant concertmasters are listed by seniority. ‡ On sabbatical § On leave

The CSO’s music director position is endowed in perpetuity by a generous gift from the Zell Family Foundation. The Louise H. Benton Wagner chair is currently unoccupied.

TIMPANI

David Herbert Principal

The Clinton Family Fund Chair

Vadim Karpinos

Assistant Principal

PERCUSSION

Cynthia Yeh Principal

Patricia Dash

Vadim Karpinos

LIBRARIANS

Justin Vibbard Principal

Carole Keller

Mark Swanson

CSO FELLOWS

Ariel Seunghyun Lee Violin

Jesús Linárez Violin

The Michael and Kathleen Elliott Fellow

ORCHESTRA PERSONNEL

John Deverman Director

Anne MacQuarrie Manager, CSO Auditions and Orchestra Personnel

STAGE TECHNICIANS

Christopher Lewis

Stage Manager

Blair Carlson

Paul Christopher

Chris Grannen

Ryan Hartge

Peter Landry

Joshua Mondie

The Chicago Symphony Orchestra string sections utilize revolving seating. Players behind the first desk (first two desks in the violins) change seats systematically every two weeks and are listed alphabetically. Section percussionists also are listed alphabetically.