MAKING SENSE of it ALL HIDDEN HEROES

REVOLUTIONARY Side EFFECTS

MAKING SENSE of it ALL HIDDEN HEROES

REVOLUTIONARY Side EFFECTS

Investors Served:

OPENING FEBRUARY 28, 2026

This exhibition, made possible through the generosity of Don and Elaine Bogus, will be on view in the Henry H. Weldon Gallery.

In 2026, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation celebrates its one hundredth anniversary. A new exhibition, C Colonial Williamsburg: The First 100 Years, will explore the origins and evolution of the nonprofit educational institution that operates the world’s largest U.S. history museum.

Visitors to the exhibition will be able to follow this fascinating story through the decades, discovering the people, events, and progress that has advanced Colonial Williamsburg to where we are today.

"That the Future May Learn From the Past" — as true today as it was in 1926.

Visit the exhibition “Colonial Williamsburg: The First 100 Years” – Opening February 28, 2026

4 BUILDING ON A FOUNDATION

6 ON THE WEB

8 CHANGING OF THE GUARD

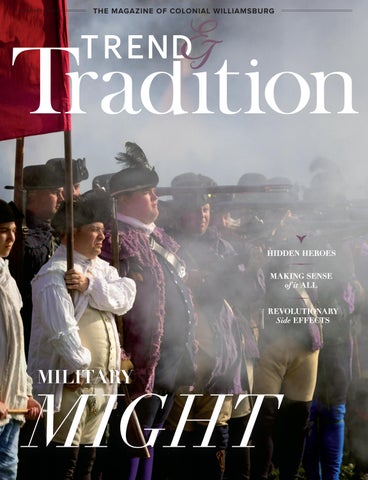

New military programs debut By Paul Aron

13 2026 CALENDAR

Highlights of upcoming events

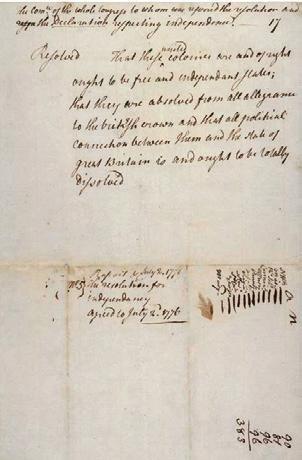

14 DISSECTING THE DECLARATION

Explore the declaration through objects on exhibit

20 PHILANTHROPY AT WORK

Unseen hands make it happen By

Ben Swenson

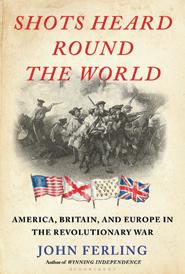

26 ALL THAT’S FIT TO PRINT

How the 18th century was the dawn of Virginia’s printing age By Rivi Feinsilber

27 MODERN HISTORY

32 CHRONICLES OF THE COLLECTION

A shoulder plate shows a soldier’s loyalty to the Crown By Paul Aron

34 FORGED IN AMERICA

New collaboration focuses on bedding By Pete Van Vleet

37 AT THE MUSEUMS

Martha Washington and Abigail Adams

Jeanne Abrams

Common

Cathy Hellier

A

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION TRUSTEES

Carly Fiorina, Chair, Mason Neck, Va.

Cliff Fleet, President and CEO, Williamsburg, Va.

Kendrick F. Ashton Jr., Arlington, Va.

Frank Batten Jr., Norfolk, Va.

Geoff Bennett, Fairfax, Va.

Catharine Broderick, Lake Wales, Fla.

William Casperson, Scottsdale, Ariz.

Mark A. Coblitz, Wayne, Pa.

Ted Decker, Atlanta, Ga.

Walter B. Edgar, Columbia, S.C.

Neil M. Gorsuch, Washington, D.C.

Conrad Mercer Hall, Norfolk, Va.

Antonia Hernandez, Pasadena, Calif.

John A. Luke Jr., Richmond, Va.

Walfrido J. Martinez, New York, N.Y.

Leslie A. Miller, Philadelphia, Pa.

Steven L. Miller, Houston, Texas

Joseph W. Montgomery, Williamsburg, Va.

Steve Netzley, Carlsbad, Calif.

Walter S. Robertson III, Richmond, Va.

Gerald L. Shaheen, Scottsdale, Ariz.

Larry W. Sonsini, Palo Alto, Calif.

Sheldon M. Stone, Los Angeles, Calif.

Y. Ping Sun, Houston, Texas

Hon. John Charles Thomas, Richmond, Va.

Jeffrey B. Trammell, Washington, D.C.

Alex Wallace, New York, N.Y.

CHAIRS EMERITI

Thurston R. Moore, Richmond, Va.

Richard G. Tilghman, Richmond, Va.

Henry C. Wolf, Williamsburg, Va.

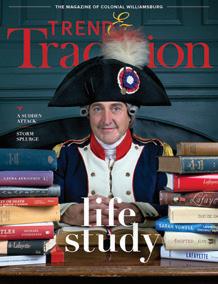

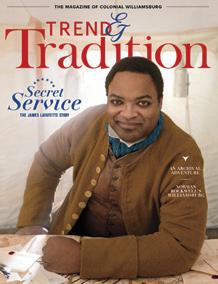

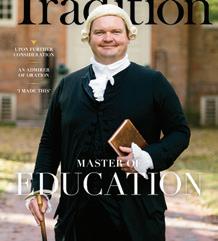

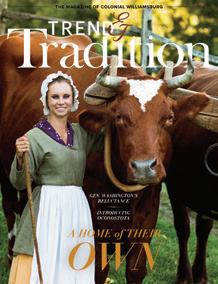

TREND & TRADITION

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

Catherine Whittenburg

CREATIVE DIRECTOR

Katie Roy

DESIGNERS

Katherine Jordan

Lauren Metzger

PHOTOGRAPHER

Brian Newson

EDITORIAL MANAGER

Pete Van Vleet

CONTRIBUTING EDITORS

Paul Aron, Ronald L. Hurst, Eve Otmar, Rachel West

COPY EDITORS

Patricia Carroll, Amy Watson

MEDIA COLLECTIONS

PRODUCTION MANAGER

Angela C. Taormina

PUBLICATIONS

COORDINATOR

Grenda Greene

Tracey Gulden, Jenna Simpson, Brendan Sostak

RESEARCH

Erin Lopater, Marianne Martin, Douglas Mayo

DONORS Please address all donor correspondence, address changes and requests for our current financial statement to: Signe Foerster, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, P.O. Box 1776, Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776 or email sfoerster@cwf.org, telephone 888-293-1776.

Donations support the programs and preservation efforts of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, a not-for-profit, tax-exempt corporation organized under the laws of the Commonwealth of Virginia, with principal offices in Williamsburg, Virginia.

Address changes & subscription questions: gifts@cwf.org or 888-293-1776

Editorial inquiries: editor@cwf.org

Advertising: magazineadsales@cwf.org

Trend & Tradition: The Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg (ISSN 2470-198X) is published quarterly in winter, spring, summer and autumn by the not-for-profit Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 301 First Street, Williamsburg, VA 23185. A one-year subscription is available to Foundation donors of $50 a year or more, of which $14 is reserved for a subscription. Periodical postage paid at Williamsburg, VA, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Trend & Tradition: The Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg, Attn: Signe Foerster, P.O. Box 1776, Williamsburg, VA 23187-1776. © 2026 The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. All rights reserved.

NOTE Advertising in Trend & Tradition does not imply endorsement of products or services by The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

History guided the Founders in forming the nation and continues to serve as a beacon today

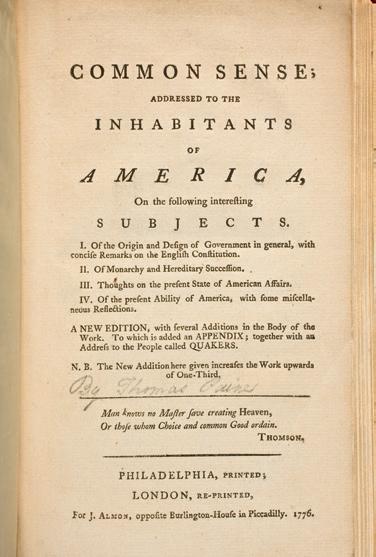

The closer we draw to July 4, 2026, when we will lead the nation in commemorating the 250th anniversary of American independence, the more I find myself returning to the documents that shaped our republic. Few are more passionate than Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, which you will read more about in this issue of Trend & Tradition. And few are more visionary than Virginia’s Declaration of Rights or more inspiring than the Declaration of Independence. On the eve of our nation’s semiquincentennial, these documents occupy top slots on many reading lists, including mine. But I confess that lately, the Federalist Papers of 1787-1788 have reclaimed my attention. For while the 250th anniversary of their publication may be more than a decade hence, they speak with remarkable clarity to the historical origins and enduring importance of representative self-government.

Writing under the pseudonym “Publius,” a triumvirate of 18th-century statesmen Alexander Hamilton and John Jay of New York and James Madison of Virginia published 85 essays that would become known as the Federalist Papers. Their goal: to convince the public to adopt the Constitution, which would strengthen and reorganize the central government into three distinct branches. At the end of a contentious convention, on Sept. 17, 1787, a majority of state delegates signed the Constitution. But, for this bold and innovative constitutional framework to supplant the Articles of Confederation, the states themselves at least nine of them would have to ratify it.

Thus, the debate between the Constitution’s supporters and its opponents continued. In arguing for ratification, the authors of the Federalist Papers illuminated the arc of political ideology that had led to this moment from the ancient Greco-Roman models of self-rule to the ideas and principles that had caught fire during the Enlightenment about natural rights. The Constitution did win the states’ approval, of course, ultimately becoming the world’s longest-surviving national constitution, an extraordinary feat. The longevity of the document likely exceeded even the expectations of the authors of the Federalist Papers, which legal scholars have cited through the ages as a key reference for interpreting the Constitution’s original intent.

But you may be wondering why, with the semiquincentennial of American independence nearly here, am I dwelling on this set of later essays? In a word: history. The Federalist Papers illustrate the enormous role that the study of history had in building this nation. Publius had reflected deeply on how various governments had operated through the centuries and why some failed while others succeeded. It is an exercise that bears repeating. Now as then, we cannot know, much less successfully govern, ourselves if we have no real sense of the work that has come before us. If we fail to grasp the how and the why that have propelled us through the centuries to this moment, how can we chart our way through the future?

This year, the U.S. semiquincentennial brings a oncein-a-generation opportunity to unite an anxious nation through the power of history. It is an opportunity we sorely need. Test after test starkly shows the undereducation of most Americans about our past and our structure and forms of government. Lacking that understanding, too many have lost touch with the work we inherited from America’s founding generation to continue building a more perfect union. Rather than feel united in our shared civic responsibility, too many of us feel divided from one another.

We need the guiding light of history so that we may learn from and build upon it. It was in this belief that John D. Rockefeller Jr. and the Reverend W.A.R. Goodwin created Colonial Williamsburg, which today operates the world’s largest U.S. history museum. Our purpose is simple: to ensure that the future may learn from the past. Nearly 100 years after the Foundation’s own founding, this mission drives everything that we do.

Over the last several years, the Foundation has taken the nation on a journey through the extraordinary events that led to our nation’s founding. Time and again, these milestones have reinforced the central role of Virginia and especially that of Williamsburg to our nation’s formation. It was here that the colony’s lawmakers met in 1773 at the Raleigh Tavern and issued the first call for intercolonial cooperation. In 1774, Virginians gathered here at the Capitol to choose Virginia’s delegates to the First Continental

Congress. And in 1775, soon after Patrick Henry shook the walls of St. John’s Church in Richmond with his “Liberty or Death” speech, it was here that Lord Dunmore removed the colonists’ gunpowder from the Magazine. Within months he would flee the Governor’s Palace and issue his famous offer of freedom to those enslaved by Revolutionary Virginians if they joined the British forces. And it was here, on June 12, 1776, that the Fifth Virginia Convention adopted the Declaration of Rights, which deeply influenced the Declaration of Independence and later the Bill of Rights. And it was also here where the final victory at Yorktown secured the birth of our nascent nation.

Our nation’s formative years were certainly raucous with great debates about the course to set. Yet in studying them I find myself returning to three straightforward themes. First, America’s Founders remained devoted students of history. These men were neither perfect nor omniscient, but they drew key lessons from past cultures, philosophies and governing systems across the centuries. As a result, they were able to design a resilient new constitutional order that could safeguard liberty while also enabling effective governance.

The second theme is the foundational importance of the concept of natural rights. Rooted in classical philosophy and refined by Enlightenment thinkers like Locke and Montesquieu, the concept was a radical idea that flipped centuries of political tradition: Government was no longer the source of rights, but their protector. That the Founders embraced this concept, but applied it to only a selective few, remains a paradox with which we continue to wrestle. But their generation’s struggle in the name of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness set our nation on a continuing course of expanding freedom and opportunity in America and around the globe.

The third theme is that many of these leaders understood human nature. They certainly were not psychologists, but in their writings, Jefferson, Madison, Mason, Washington and others reveal a deep awareness of human flaws and passions. James Madison’s reflections on factionalism, for example, show a nuanced grasp of how liberty and selfinterest interact: “Liberty is to faction what air is to fire.... It could never be more truly said than of the first remedy, that it was worse than the disease.” Such insights remind us that disagreement, dissent and even deep division are nothing new for our nation. They are inherent to a system built to protect freedom.

Here at the Foundation, we believe that history is the most essential discipline and we are in a uniquely pow-

erful position to share it because Colonial Williamsburg preserves the physical spaces where our nation began. We house the nation’s oldest known school for Black students and the very structure where George Wythe taught law to Thomas Jefferson and John Marshall. We are host to the nation’s first hospital for people with mental disorders, one of the nation’s earliest Black churches and the room where Phi Beta Kappa began. It was at the Capitol and Raleigh Tavern where debates occurred that would define a new nation and where lawmakers in May 1776 decided that Virginia should lead the way by proposing in Congress that all 13 colonies declare independence together.

Thanks to your support, we have long been preparing for this historic year in our nation’s history. We have dramatically expanded our research and preservation efforts, which have revealed new chapters of history and enabled us to open more historic spaces. We have vastly increased our reach digitally, as well as through the media, to share the Foundation’s educational resources with many millions more people. We have hosted three national planning meetings to prepare for America’s 250th and partnered with William & Mary and the Omohundro Institute to create important new learning opportunities. Now we are bringing forth an entire year of compelling new programs, exhibitions and commemorations including a truly spectacular July Fourth celebration. You can read much more online about our plans at colonialwilliamsburg.org/2026, and we invite you to join us throughout this entire exciting year.

Two hundred and fifty years ago, the Founders knew their life’s work remained unfinished, leaving issues for future generations to address. As we reflect on our past and look toward the future, let us remember this: History is not just about what happened. It is about who we are and what we do. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation is committed to using history the way our Founders envisioned: to educate, to inspire and to use its lessons to continue the work of building a more perfect union.

Sincerely,

Cliff Fleet President & CEO

Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Distinguished Presidential Chair

Explore how Elizabeth Hayes helped seal the deal for Colonial Williamsburg’s restoration. colonialwilliamsburg.org/ hayesnotebook

Not just places to eat and sleep, taverns were a place to exchange and explore ideas. colonialwilliamsburg.org/taverns

The Wythe House served future presidents and helped win the Revolutionary War. colonialwilliamsburg.org/wythe

EXPLORE COLONIAL SITES AND HISTORY . PEEK BEHIND THE SCENES . PURSUE AND PLAN

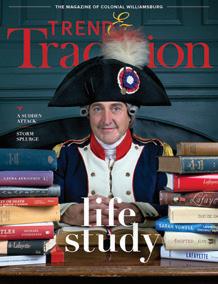

BY PAUL ARON · PHOTOGRAPHY BY BRIAN NEWSON

Colonial Williamsburg is renowned for showing how so many of the ideas that inspired the American Revolution came out of Virginia’s early capital. But the new nation was the result of battles as well as ideas, and a new initiative aims to tell those stories.

Though Williamsburg was not the site of a major battle during the Revolutionary War, new regiments of soldiers gathered, trained and were clothed and equipped in town before marching off to war. One unit, the 2nd Virginia Regiment, was in Williamsburg from 1775 until early 1777.

“This is a site that saw a consistent military presence until the capital moved to Richmond in 1780,” said Sam McGinty, supervisor of military programs. “By thinking about who was here in Williamsburg day by day, we can tell a thoughtful story of Virginians during the Revolution.”

As with all Foundation programs, military ones are based on extensive research using primary documents, including correspondence and pension records. One key source is the orderly book of the 2nd Virginia Regiment, which served as the daily log of the orders and actions of the unit while they trained in Williamsburg.

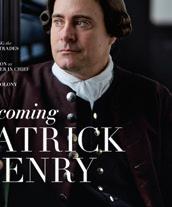

(Opposite) Supervisor of Military Programs Sam McGinty donned a purple hunting shirt for a special program in November, just as members of the 2nd Virginia Regiment did in 1775. (Above) Senior Manager ofTrades and Skills Davis Tierney (second from left) led a detachment of the recreated 2nd Virginia Regiment.

(Clockwise from top)

The recreated 2nd Virginia assembled in formation during drills. Military programs staff took delivery of an iron 3-pounder from the wheelwrights and moved it into position. Journeyman Weaver Joseph Wixted dyed shirts “of a purple Coulour.”

Also valuable are records of Virginia’s Public Store, a statewide warehouse and supply system established in Williamsburg in 1775 to equip Virginia forces.

“The surviving records of the Public Store tell the robust story of the challenges of building and forming an American army, and the shifting aesthetics of a new American identity,” said McGinty. “They provide us with a road map for re-creating that army 250 years later.”

Many military programs take place near the town’s iconic Magazine, which is currently being restored to its 18thcentury appearance. Others utilize the adjacent Guardhouse, which was reconstructed in 1935. According to the

orderly book, the Guardhouse was used as a “laboratory,” a military term used at the time for a place where ammunition was produced.

“The Guardhouse offers a unique opportunity to explore this important, and perhaps first, patriot laboratory and its contribution to the American war effort,” said McGinty. Guests will be able to participate in hands-on activities such as cartridge rolling and mock gunpowder pouring. Guests will also encounter military interpreters exploring the many duties and skills of Revolutionary soldiers, including maintaining and repairing weapons, manufacturing cartridge boxes and other equipment, sewing uniforms, cooking and drilling.

A special event highlighting the formation of the 2nd Virginia Regiment in Williamsburg 250 years ago took place Nov. 1–2 and welcomed more than 60 reenactors to help illustrate how Williamsburg prepared for war.

The orderly book called for “Officers and Soldiers to Spend one hour to day in Learning the Usual Exorcise and Evolutions.” So, in the mornings guests of all ages heeded the call to arms and joined the 2nd Virginia Regiment. They were briefed on the war and then trained to march and drill before being inspected by Capt. William Taliaferro, portrayed by McGinty.

At noon, guests experienced the heavy weight of liberty in the form of artillery. In 1775, Capt. James Innes trained recruits to use these “great guns,” and in November guests joined interpreters as they hauled the guns into position on the Courthouse green. Guests also learned about loading

and firing a cannon, followed by a firing demonstration.

Still drawing from the orderly book, which called for “Officers and Soldiers to Spend three hours in learning the Discipline of Woods fighting . . . as the most Likely method to make the Troops formidable to their Ennemies,” afternoon programs offered training in this tactic influenced by Indigenous American warfare of the 18th century. And just as the orderly book recorded that men “are always to fall in upon the Parade at Revelle Beating and Retreat Beating with their Arms & Ammunition,” the days concluded with a formal ceremony, followed by a march back toward their historic camp at William & Mary.

The 2nd Virginia wore hunting shirts, a uniquely American garment that was more like a jacket. The orderly book contains an order from Oct. 27, 1775, for the soldiers to dye their hunting shirts “of a purple Coulour,” presumably in an effort to give the soldiers a more uniform appearance. With that order in mind, Colonial Williamsburg’s weavers dyed hunting shirts purple for the military programs staff.

“We don’t know why purple,” McGinty said. “Maybe it was because brazilwood, a dyestuff used to make purple, was available and cheap. Or perhaps William Woodford, who commanded the 2nd, just really liked purple. Unfortunately, the reason seems to have been lost to history.”

The special event, called “Williamsburg Dy’d of a Purple Coulour,” included specialized work from many historic trades: The wheelwrights delivered a freshly painted cannon carriage, the foundry staff delivered freshly cast bullets, the printers delivered enlistment papers, the cooks explored differences between meals within the army

“We are telling a broader story than just guys with guns.”

-Sam McGinty

to compare class and rank, and the farmers delivered fresh provisions to the soldiers.

“This multifaceted approach to telling the story of Williamsburg at war in 1775, utilizing our incredibly knowledgeable trades and skills, provided guests with a unique and dynamic look into the town’s past,” said Davis Tierney, senior manager of Historic Trades and Skills.

The

In 2026, military programs will highlight the two rifle companies of the 7th Virginia Regiment, which were composed of Virginia frontiersmen commanded by Capts. Joseph Crockett and Thomas Posey. Unlike British officers, whose commands were purchased and therefore tied to wealth and status, Virginia officers, like Crockett and Posey, rose through the ranks based on merit and skill.

Those portraying the riflemen of the 7th Virginia will be dressed in a mix of conventional military dress and clothing influenced by their frontier background. The riflemen of the 7th saw action at the battles of Brandywine, Germantown and Saratoga.

Both Tierney and McGinty have extensive experience interpreting mili-

tary history. They both were military interpreters for Colonial Williamsburg before leaving to work at other museums. McGinty returned to Colonial Williamsburg in 2024, followed by Tierney in 2025, to rebuild the Foundation’s military programming and to help organize special events tied to the 250th anniversary of the American Revolution.

“We are telling a broader story than just guys with guns,” McGinty said. “We have tried to be thoughtful of the humanity of the people we’re representing, rather than thinking of them as model soldiers on a board.”

The next special event, scheduled for the first weekend of May, will highlight the arrival of Crockett and Posey. Other events tied to pivotal moments in Virginia’s Revolutionary past will follow.

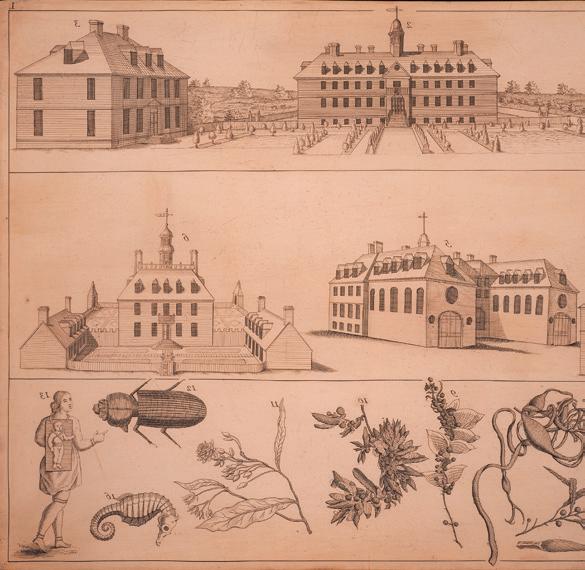

“ Colonial Williamsburg: The First 100 Years” Opens at The Art Museums of Colonial WIlliamsburg

Feb. 28

Centennial Exhibition opens, celebrating a century of discovery, interpretation and preservation of America’s colonial capital.

Colin G. and Nancy N. Campbell Archaeology Center Weekend

April 25–26

This weekend celebration marks the debut of a state-of-the-art facility dedicated to advancing archaeological research and deepening public engagement with Williamsburg’s rich history.

Flame of Revolution: Commemorating the Fifth Virginia Convention

May 15–16

On May 15, 1776, all eyes were on Williamsburg at the Fifth Virginia Convention. The nation held its breath in anticipation as the issue of declaring independence was debated. Follow the journey and discover why Williamsburg stood as the crucible for a new nation.

250th Anniversary of the First Virginia Declaration of Rights

June 12–14

Commemorate this landmark document, which established a framework for protecting individual liberties and limiting government power. Hear from the author on what inspired the document and its enduring impact on the foundation of the country.

Independence Day Weekend

July 2–5

Celebrate the 250th anniversary of our

nation’s birth in the place where it all began: Williamsburg.

African Baptist Meeting House and Burial Ground Dedication

Oct. 9 –10

Join the Let Freedom Ring Foundation, the Historic First Baptist Church of Williamsburg and The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation to commemorate the reconstruction of the African Baptist Meeting House at the site of the original permanent location of the First Baptist Church, one of the earliest African American congregations in the United States.

For more information on 2026 programs and events, please visit colonialwilliamsburg .org/2026

Colonial Williamsburg 100th Anniversary Event America’s 250th Anniversary Event

A guided tour that explores the Declaration of Independence through objects on exhibit at the Art Museums and in the collections

“We hold these truths to be selfevident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

These powerful words are perhaps the ones people remember most when they think of the Declaration of Independence. Or maybe it is these words:

“When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another...”

But what about the rest of the document? While these introductory words are inspirational and important, the real substance is in the body of the text the list of reasons for breaking away from Britain. It wasn’t just about taxes.

“The history of the present King of Great Britain is a history of repeated injuries and usurpations, all having in direct object the establishment of an absolute Tyranny over these States.”

The Declaration of Independence lists 27 specific grievances directed at King George III. These grievances reveal the depth of colonial frustration from political interference to economic restrictions and denial of self-governance.

FROM THE DECLARATION

“He has forbidden his Governors to pass Laws of immediate and pressing importance, unless suspended in their operation till his Assent should be obtained; and when so suspended, he has utterly neglected to attend to them.”

Governor’s Chair

ca. 1750

Royal governors had the authority to suspend or dismiss elected colonial governments. In Virginia, Gov. Francis Fauquier dissolved the House of Burgesses in 1765 after it passed resolutions against the Stamp Act. In 1769, the governor, Lord Botetourt, dismissed the burgesses when they protested taxes on imported goods. The governor, Lord Dunmore, dissolved the group in 1774 after it condemned Parliament’s closure of the port of Boston. These dissolutions silenced colonial voices and reinforced the belief that Britain sought to strip the colonies of their right to self-government.

FROM THE DECLARATION

“He has refused his Assent to Laws, the most wholesome and necessary for the public good.”

Portrait of George III

ca. 1770

The first grievance accuses King George III of rejecting laws that were essential for the well-being of the colonies. Colonial assemblies often passed measures to address local needs, but these laws required royal approval. When the king, and often Parliament, vetoed them, it deepened colonial frustration. This grievance highlights the lack of self-governance and the growing belief among the colonies that they needed independence to enact laws for their own public good.

FROM THE DECLARATION

“He has obstructed the Administration of Justice, by refusing his Assent to Laws for establishing Judiciary powers.”

“The Royal Family of Great Britain” Handkerchief ca. 1775

The colonists were frustrated with British interference in legal systems. By controlling judicial appointments, the king and Parliament ensured that judges were loyal to the Crown rather than to the colonists. This lack of judicial independence undermined trust in the legal system and fueled resentment; fair justice was impossible under a system where courts served royal interests instead of protecting colonial rights.

FROM THE DECLARATION

“He has refused for a long time, after such dissolutions, to cause others to be elected; whereby the Legislative powers, incapable of Annihilation, have returned to the People at large for their exercise; the State remaining in the mean time exposed to all the dangers of invasion from without, and convulsions within.”

Tower Clock Movement

From the Capitol ca. 1750

By refusing to restore representative government, the king left the colonies vulnerable to external threats and internal unrest. The phrase “incapable of Annihilation” underscored the Founders’ belief that government derives its legitimacy from the people. When that trust is broken, the people have the right to create a new system, a concept highlighted in the Declaration’s introduction: “It is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government.”

FROM THE DECLARATION

“He has kept among us, in times of peace, Standing Armies without the Consent of our legislature.”

Pattern 1742 Land Service Musket

ca. 1742–1750

Following the French and Indian War, Britain stationed 10,000 soldiers in North America a military force controlled by the Crown rather than by elected representatives. Maintaining these troops was costly, and Britain’s war debt led to increased taxes at home and on American colonists. The removal of the French threat raised questions for the colonists. Why did Britain need an army in peacetime? Why were taxes rising without representation? These frustrations fueled a growing belief that British policies were unjust and oppressive.

FROM THE DECLARATION

“For cutting off our Trade with all parts of the world.”

“A Plan of the Town and Harbour of Boston” ca. 1775

This grievance highlights Britain’s restrictions on colonial trade. Originating in the 1660s Navigation Acts, these rules were only loosely enforced under a policy known as salutary neglect. In the 1760s, Britain tightened enforcement of them to raise revenue, increasing costs, limiting markets and hurting colonial prosperity. Punitive laws like the 1774 Boston Port Act closed Boston Harbor. For colonists, these measures symbolized Britain’s attempt to control and exploit their economy, fueling the push for independence.

FROM THE DECLARATION

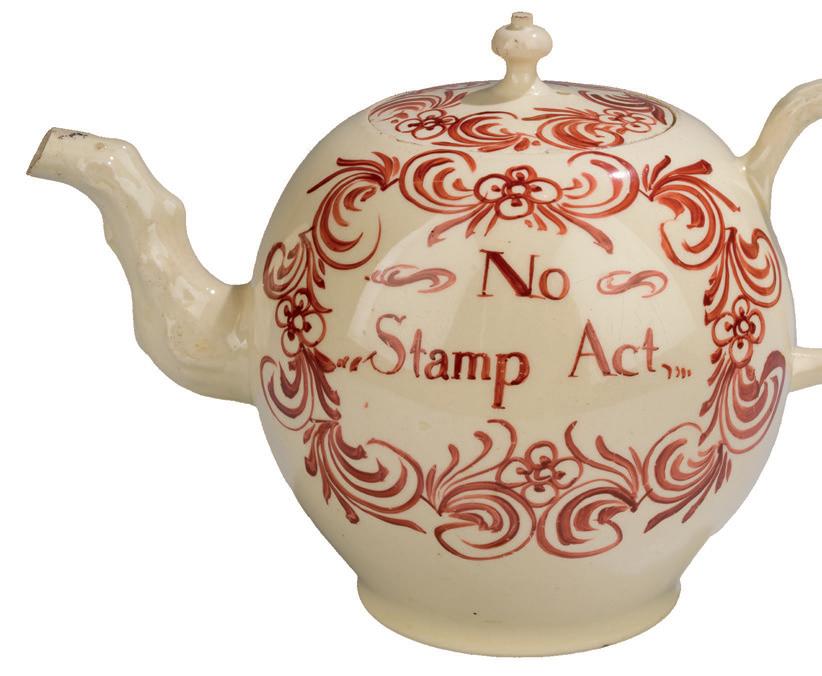

“For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent.”

Teapot ca. 1766–1770

This principle is captured in the phrase “No taxation without representation,” which asserts that a government cannot legitimately impose taxes unless citizens have a voice in the decisions. Rooted in the English Bill of Rights (1689), this idea became a major grievance for American colonists, who argued they should not be taxed by a Parliament where they had no representation.

FROM

THE DECLARATION

“For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences.”

Needlework Picture of Sailing Ship ca. 1865–1900

Parliament was determined to assert its authority over the colonies and, as such, the 1774 Intolerable Acts targeting Massachusetts allowed anyone accused of crimes against officials enforcing the king’s laws to be transported, at the government’s discretion, to another colony or even England for trial. Many opposed the measure, viewing it as retaliation against Massachusetts.

FROM THE DECLARATION

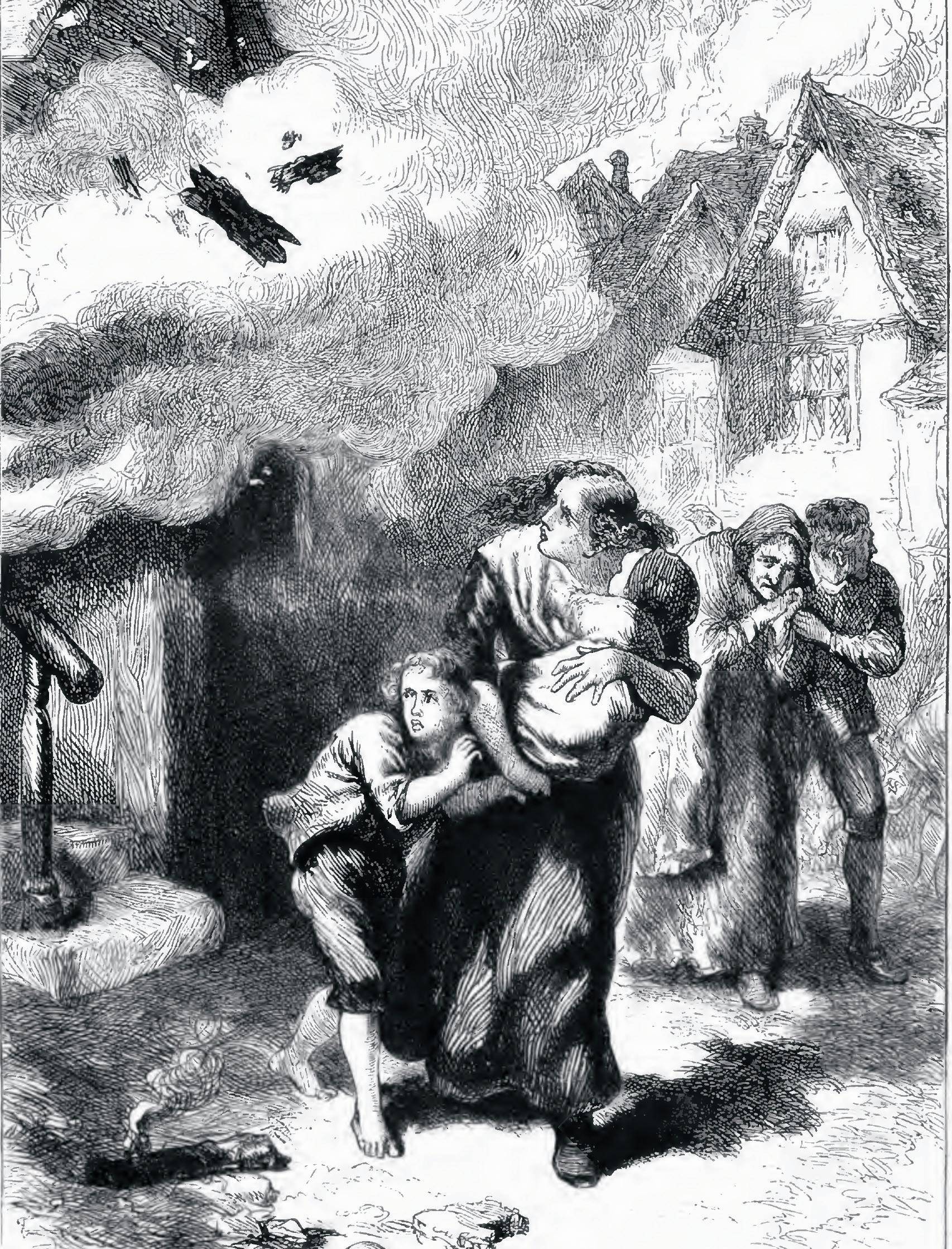

“He has plundered our

seas,

ravaged our Coasts, burnt our towns, and destroyed the lives of our people.”

Porcelain Plate With the Dunmore Family Coat of Arms

ca. 1755

With British troops burning American towns acts meant to suppress what Britain saw as rebellion King George III had effectively declared war on the colonies. But Americans viewed their true authority as the colonial legislatures and town meetings, which Britain had shut down and attacked. In late 1775 and early 1776, Lord Dunmore, the king’s last representative in Virginia, raised a small force and launched assaults along the colony’s coast and rivers, intensifying the conflict.

FROM THE DECLARATION

“He is at this time transporting large Armies of foreign Mercenaries to compleat the works of death, desolation and tyranny, already begun with circumstances of Cruelty & perfidy scarcely paralleled in the most barbarous ages, and totally unworthy the Head of a civilized nation.”

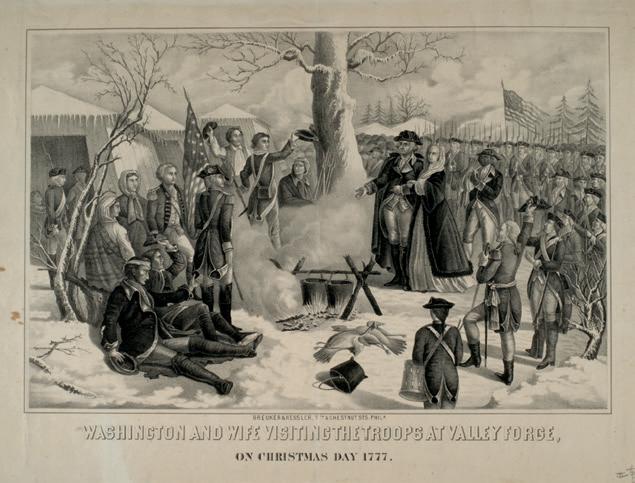

Portrait of Gen. George Washington

ca. 1780

Hiring foreign troops was common in Europe, but American colonists saw it as shocking and threatening. To them, it meant the king was willing to use not only British forces but also foreign mercenaries against his own subjects. This act symbolized tyranny and a violation of colonial rights, reinforcing the belief that Britain sought total domination.

By Ben Swenson

Sprawling over more than 300 acres and containing 89 original 18th-century buildings, the Historic Area presents a sweeping view of a generation that changed the course of human events. Guests can step inside buildings that stood during the thunder of revolution, trace the footsteps of the nation’s Founders through restored gardens and examine artifacts that defined the colonists’ life and culture.

Those vignettes and many more are the public face of an enormous endeavor to bring the past to life and share the stories of America’s founding, made possible by the generous support of donors. But beneath the surface of this immersive experience lies a diverse and largely out-of-sight body of profes-

sionals who support this extraordinary venture.

Those vignettes and many more are the public face of an enormous endeavor to bring the past to life and share the stories of America’s founding. Donor support allows The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation to keep these lessons of history alive through groundbreaking preservation work, primary source research and innovative educational programming.

But beneath the surface of this immersive experience lies a diverse and largely out-of-sight body of professionals who support this extraordinary venture.

The Department of Historical Clothing and Dress

(Opposite) Repairing and refurbishing buildings in the Historic Area are never-ending tasks, including installing siding on the Williamsburg Bray School.

occupies the Costume Design Center on the edge of Colonial Williamsburg’s Bruton Heights Center campus. Inside, sewing machines, scissors and patterns occupy broad tables. Period clothing hangs on racks that stretch the length of the workspace. Here, a crew of roughly a dozen assembles an entire wardrobe, from head to toe, for each of the Historic Area’s 400 costumed staff a number that increases during the busier summer months and when there are special events.

Jenna Hallett, a cutter/ draper and head of the shop, said that each day the team conducts three to six wardrobe fittings, each of which might take as little as 15 minutes or up to three hours for specialty clothing. When they are not

measuring colleagues, they are snipping and stitching attractive, comfortable clothing that supports Colonial Williamsburg’s faithful interpretation of the Revolutionary era.

“We try our best to represent the period as accurately as possible using the tools at our disposal,” Hallett said.

Michael Ramsey, who is the lead accessories craftsperson for the department, said that the team’s job is nonstop and, at times, imposing. There are specialty costumes to make as well as outfitting new hires. Beyond that the team is continually mending clothes for normal wear and tear and make adjustments for

size changes especially for the adolescents of the Fifes and Drums.

“Even though the task at hand is hard, every person in this building does their work with a great deal of passion and goodwill,” he said.

Guests to the Historic Area meet men and women who work in Historic Trades, such as weavers, printers and blacksmiths, but the institution also relies heavily on modern tradespeople who make up the Building Trades team. They are experts in carpentry, millwork, masonry, painting and sign making.

Department manager

(Clockwise from top left) Workers at the Department of Historical Clothing and Dress are responsible for outfitting more than 400 staff and volunteers. That includes detail work on the coat worn by the interpreter portraying Patrick Henry. Workers at the Building Trades millwork shop inspect and repair boxes used in the Historic Garden.

Kenny Gulden said that the architecture in the Historic Area buildings and secondary structures such as wells and fences is on a seven-year rotation for painting. Each year, between 80 and 100 separate structures get repainted, work that is preceded by any necessary repairs. This regular attention provides a vital layer of protection not only for the 89 original buildings but also for the reconstructed homes and shops, some of which are more than 70 years old. The structures’ interiors demand as much time and attention as their exteriors.

The team also prioritizes emergency repairs,

which, Gulden said, are needed frequently as glass breaks, handrails shake loose, and tree roots and underground critters create tripping hazards on brick walkways.

The Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg offer the opportunity to glance back in time through paintings and portraits, fine furniture, musical instruments and the everyday items that enriched people’s lives.

Rick Hadley, director of exhibition design and production, said that well over 50 individuals have a hand in bringing a single exhibition to life. “We know who they are but, by and large, the public does not,” he said.

Behind any museum gallery stand curatorial and conservation teams that are responsible for preserving and protecting Colonial Williamsburg’s peerless collections. In addition to the items on display in the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum and the Abby Aldrich Rockefeller Folk Art Museum, Colonial Williamsburg keeps more than 70,000 objects in secure and tightly controlled storage. Each one is photographed and cataloged so that staff know its location, condition and other

important data points at any given moment.

Designers and tradespeople determine how best to show an artifact to the public. Other professionals also have a hand in bringing an exhibition to life, among them museum educators and administrators, budgeting and finance professionals, operations staff, and even the hospitality team. “There’s not one department that doesn’t have a hand in these projects,” Hadley said.

The original and reconstructed buildings are only part of the snapshot of 18th-century life. Green space also whispers through the centuries, in

(Below) Creating exhibitions falls to the museum design and operations staff, who take into consideration flow, lighting and sight lines.

the catalpa tree-lined Palace Green, for instance, and the gardens found throughout the Historic Area.

Joanne Chapman, director of landscape services, said that a multidisciplinary team with a range of specialties, such as horticulture, arboriculture and plant propagation, tends Colonial Williamsburg’s grounds.

The crew keeps open space trimmed and mowed as well as historically accurate and replaces plants that are reaching the end of their life cycles. Their work also involves security and control of unwanted growth. Crews remove limbs that pose risks to people or buildings. Chapman and her

colleagues are always trying to rein in invasive species and diseases such as boxwood blight.

Landscaping projects incorporate subtle designs that fold in modern best practices such as erosion control and irrigation to ensure the long-term integrity of the work. According to Chapman, “When we undertake these projects, we are doing them with sustainability in mind.”

Colonial Williamsburg’s research historians lie at the heart of every interaction that guests have. Whether it is in person or online, historians serve as a link between the academy and the public, according to Peter Inker, director of historical research.

Academic historians worldwide continually shine new light on facets of the past that have been

unexplored, but their work is sometimes hard to approach. On the other hand, the public has a flood of information available at the click of a mouse, but much of it may be inaccurate or biased. Colonial Williamsburg renders the scholarly accessible, Inker said, offering new and accurate historical revelations in a way that is engaging and enjoyable.

“We ensure that the public history we produce has integrity and that our guests can trust us,” Inker said.

The research historians’ work spans a wide range of tasks providing information and documentation for interpretive staff, supporting new programming and long-term projects, writing articles, working externally with other scholars and the public, and, of course, poring over historical resources

(Left) Landscaping crews are experts in horticulture, arboriculture and plant propagation. (Above) Visitors interact not only with costumed interpreters but also with staff historians and museum directors.

to discover and interpret new findings.

Research historians and the staff they support stand on the cusp of an exciting and challenging new era, Inker said. Digitization of more primary sources and artificial intelligence are reshaping the work of public history. But Inker is confident that his team can muster these new opportunities to make Colonial Williamsburg stronger as it prepares to embark on its second century of operation.

Supporters of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation help us advance this important work of illuminating the past and preserving this powerful place. The impact of our generous donors can be seen across

all facets of the work we do here.

To contribute, visit colonialwilliamsburg.org/ TT. For more information on how to give to support these programs and more, email campaign@cwf.org .

Charitable gift annuities allow you to support The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation and receive fixed lifetime payments plus tax benefits. Now you can fund these gifts with your IRA, in addition to cash and securities. And if you have required minimum distributions, using your IRA for a gift annuity is a revolutionary way to make history for you and generations to come. To learn more, contact the Office of Gift Planning at 1-888-293-1776 or legacy@cwf.org today or reply with the attached card to get started.

New exhibition explores the history and evolution of the printed word in Virginia

BY RIVI FEINSILBER

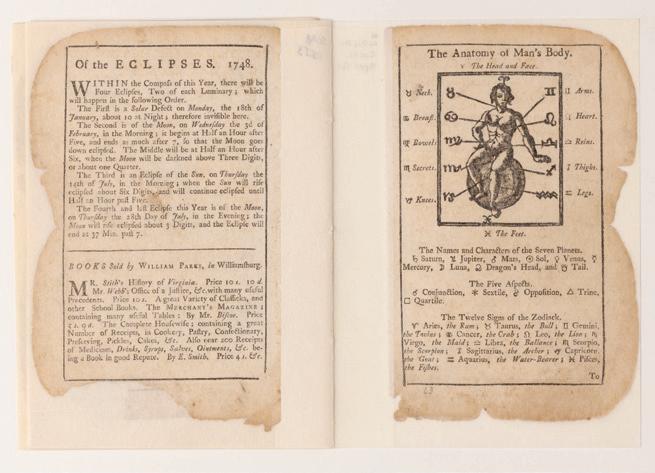

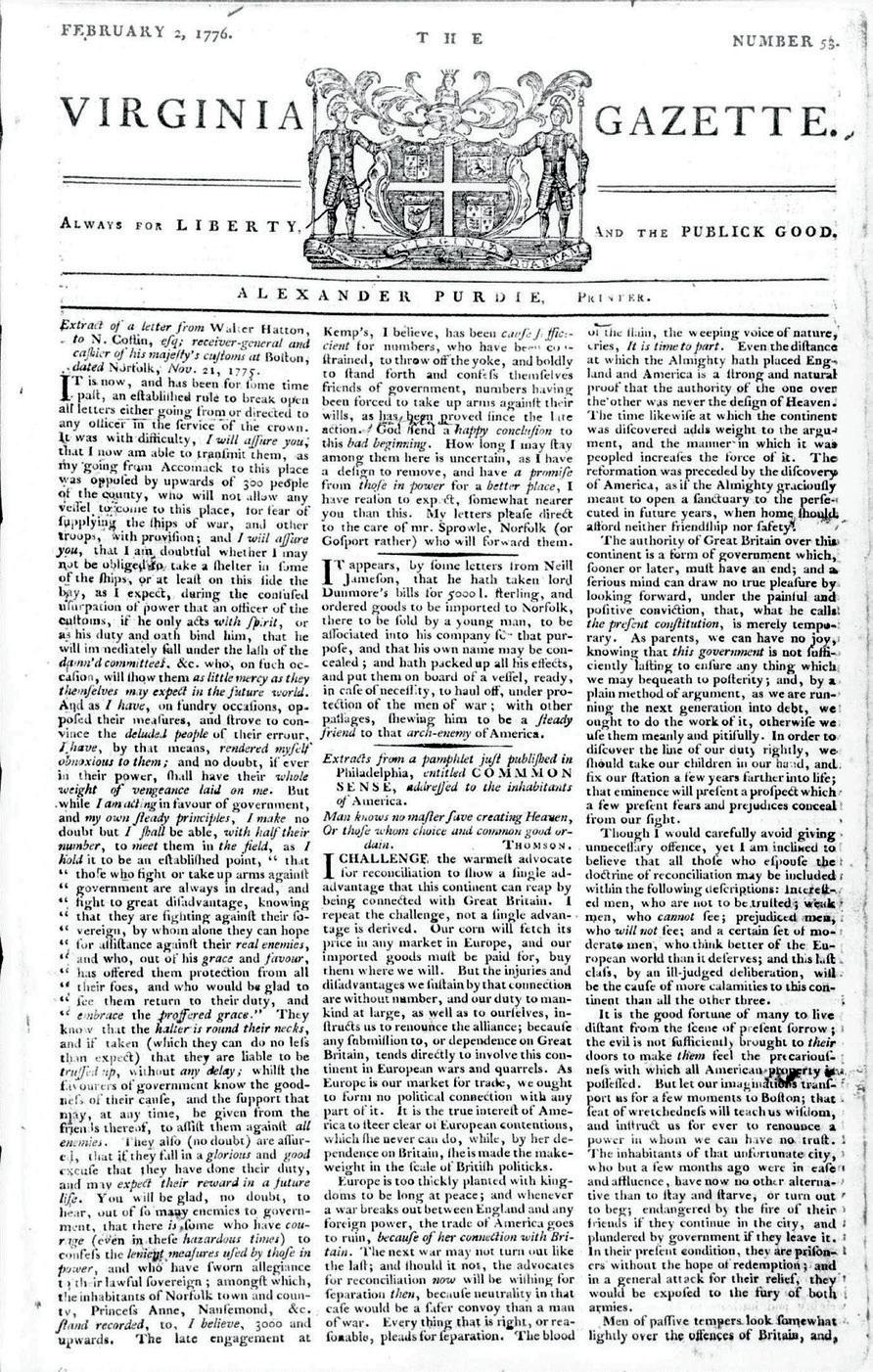

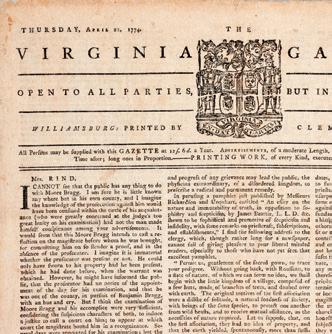

Centuries before social media, the printed word carried the news of current events from near and far, as well as the laws of the land and ideas in general. By Authority: The Printed Word in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg , on display at the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library through March, chronicles the colony’s development toward freedom and independence through an integral medium: the press.

William Parks ran Virginia’s first authorized printing shop when, in 1728, the government hired him to print the colony’s laws. He soon opened up printing to the people when he was allowed to print nongovernment commissions. The exhibition explores his work and others’ through four types of printing: periodicals (newspapers and almanacs), job printing, books and pamphlets, and government printing.

The periodicals and the books and pamphlets in the exhibition represent vital avenues that printers used to stay afloat financially and that the population relied on to stay abreast of the news, laws, literature and opportunities. The surviving ephemera also provides a glimpse of colonial life

in Williamsburg with its routine daily activities and life-changing turmoil. Chief among them is the almanac, which was so integral to colonial life that it sat in many homes where the only other book was the Bible. The almanac contained a plethora of information, including, but not limited to, weather predictions, court dates, road distances and celestial events. The Virginia Almanack, for the Year of Our Lord God, 1748,

printed by William Parks is on display, opened to pages that contain the zodiac’s relation to the anatomy of man (then a belief that each astrological zodiac sign influenced a specific part of the body) and an astronomy story that accurately predicts four eclipses that year. (The dates listed are from the Julian calendar, so they do not align with records corresponding to the current Gregorian calendar.)

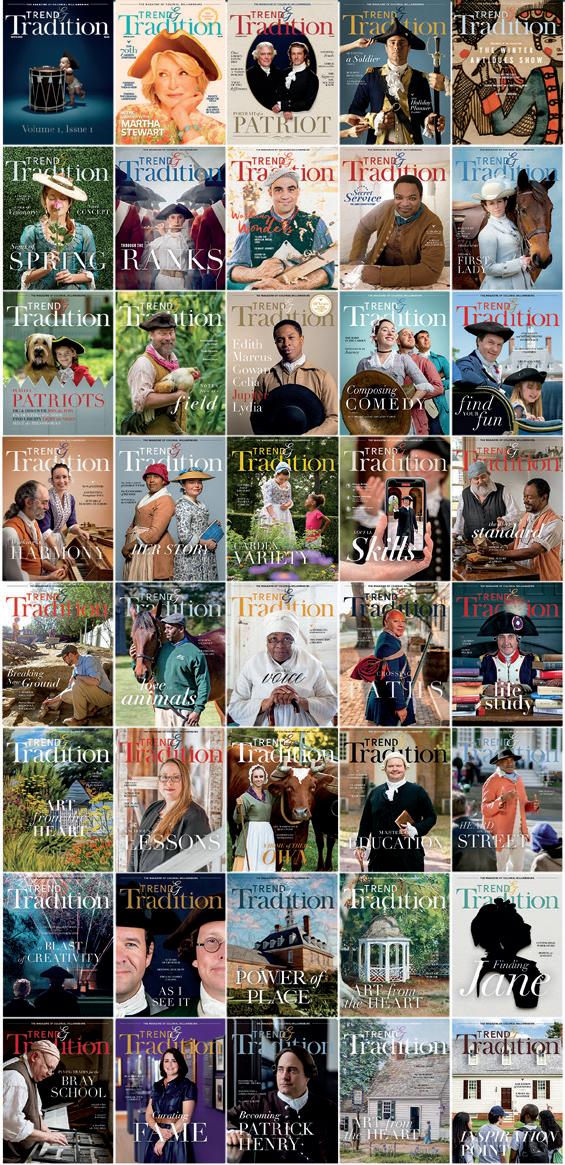

We’re 10!

AMID THE ANNIVERSARIES OF NOTE in 2026 the 250th of the Declaration of Independence and the 100th of Colonial Williamsburg there is one more worth celebrating. This issue of Trend & Tradition: The Magazine of Colonial Williamsburg comes 10 years after the publication of our first issue in Winter 2016.

We continue to strive to live up to the name of the magazine. That means keeping you informed about new perspectives and time-honored traditions. It means bringing you a mix of stories, including news about the Foundation’s discoveries and programs and original works by historians on colonial and Revolutionary history. And we continue to strive to live up to the motto that John D. Rockefeller Jr. chose for Colonial Williamsburg: That the future may learn from the past.

Those other anniversaries of 2026 will give us plenty to write about during the year. We are grateful for your support of Colonial Williamsburg and we look forward to serving you during our anniversary year and the years to come.

Work is slated to be done by April

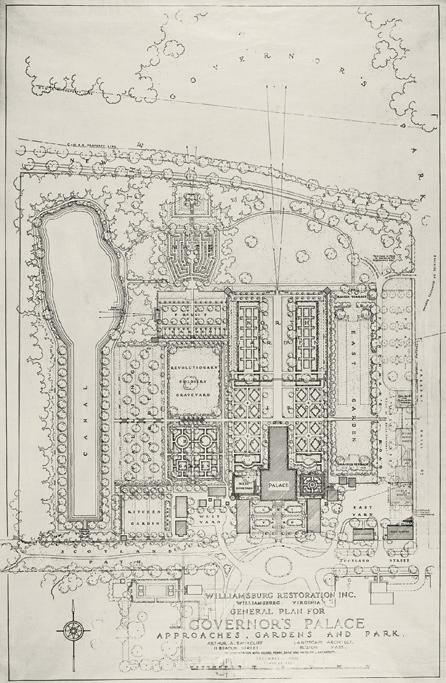

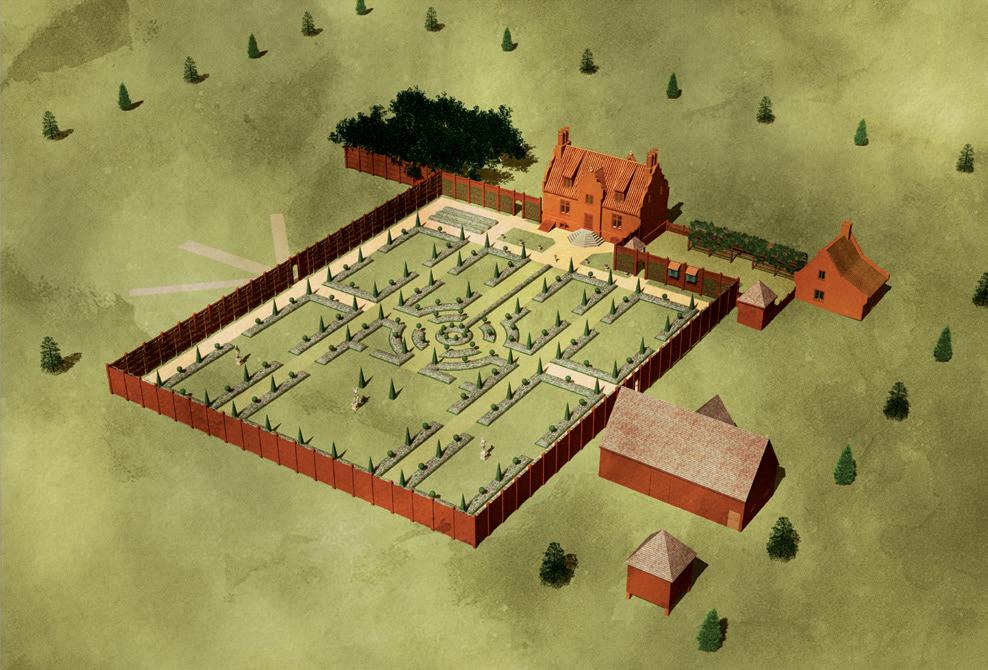

The Governor’s Palace gardens, renowned for precise layouts, rigid symmetry and, of course, beauty, have been much admired and imitated since they were restored nearly 100 years ago. Those restored gardens have inevitably aged.

The gardens are now again being restored: Vegetation has been removed from the banks of the canal, and the canal will be dredged and the banks restored to their original grades. The terraces surrounding the canal will also be restored. New, blight-resistant vegetation will be added to a former boxwood garden. A boxwood hedge suffering from blight will be removed from a Revolution-

ary War cemetery, allowing people to again honor the 156 Continental soldiers and two women who were buried there when the Palace served as a hospital.

The new restoration utilizes plans prepared by Arthur Shurcliff, the chief landscape architect of the original restoration. “We have gone back to Shurcliff’s plan,” said Jack Gary, the Foundation’s associate vice president of historic resources. “The Palace garden is a shining example of the colonial revival movement and an iconic garden.”

The restoration work is scheduled to be completed by April 2026, in time for Historic Garden Week.

James Murray Jr. recently presented to the John D. Rockefeller Jr. Library three private collections of books, journals and catalogs related to art and antiques and early American history. Two of these collections were owned by Robert E. Crawford and Marshall Goodman, Richmond-based art and antiques dealers, and served for many years as reference libraries. The third collection was Murray’s own personal library

Crawford, a devoted scholar whose tenacity in researching objects is evidenced by the many dog-eared pages of his books, established Robert Crawford Fine Art and Antiques in 1972. Strong in works on American folk art and American and European decorative arts, his collection includes over 1,000 titles. The library of Goodman, a published scholar and prominent antiques dealer for over 50 years, includes hundreds of titles on African American art, Southern decorative arts, firearms and more.

Emily Guthrie, executive director of the library, said the gift of 4,600 items enhances and complements the library’s existing holdings and will be of great relevance to the library’s community of researchers, collectors and general material cultures.

“Mr. Murray’s gift rounds out the collection with difficult-to-source reference material on art, antiques and Virginia history,” she said.

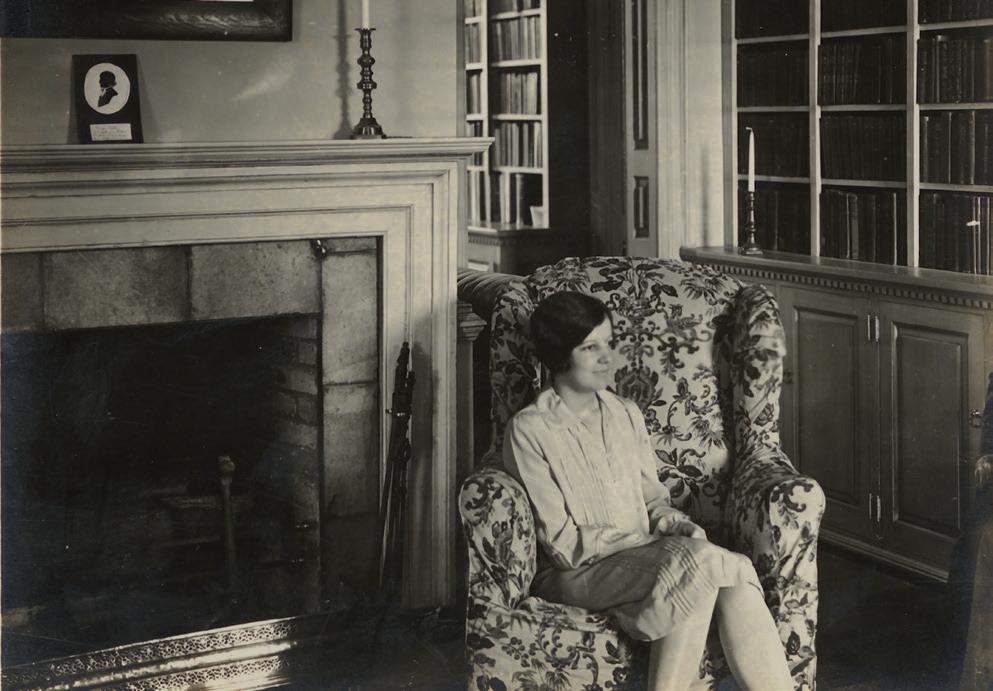

Bassett Hall, the 18th-century house which John D. Rockefeller Jr. and Abby Aldrich Rockefeller acquired in 1927 and lived in during the early years of the restoration of Williamsburg, reopened in October. The house was closed during the pandemic because its public spaces were too small to allow social distancing. It remained closed until new staff and volunteers were in place.

The house was thoroughly and accurately restored and furnished in 2003 with a gift from Abby O’Neill, the Rockefellers’ granddaughter, and her husband, George O’Neill.

“Bassett Hall has the most accurate historic interiors of any building of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation,” said Ron Hurst, the Foundation’s chief mission officer. “Virtually everything in the house is just as Abby Aldrich Rockefeller left it at her death in 1948.”

Investigation Declaration lets teens discover the ideas behind the Revolution

Investigation Declaration, an online game created by Colonial Williamsburg and iCivics, earned the prestigious 2025 GEE! Learning Game Award in the formal learning category. The game shows middle school and high school students how the Declaration of Independence captured the ideas of the Enlightenment and inspired movements toward freedom and democracy.

The game takes place in an alternate time and place where an international crime conglomerate has hacked the fictional Bureau of Ideas, corrupting every file related to

freedom, democracy and individual rights. As players restore corrupted files, they discover how ideas of natural rights, state sovereignty and the social contract spread throughout the Atlantic world following the signing of the Declaration.

“Colonial Williamsburg is always looking for new ways to bring our unique brand of history education to as many students as possible,” said Mia Nagawiecki, the Foundation’s senior vice president of education.

“Thanks to our partnership with iCivics, we have extended our reach beyond our physical location and even our significant web presence to reach kids where they are and through a medium that excites them.”

iCivics is a nonpartisan organization dedicated to furthering the teaching of civics. It was founded by Sandra Day O’Connor, who served as associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court and as a trustee of The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Colonial Williamsburg and iCivics also collaborated on Uncovering Loyalties, an online game for elementary school students. That game is set on the eve of the Revolution and lets kids choose to be patriots or loyalists.

Colonial Williamsburg is taking part in a statewide initiative to encourage people to commemorate America’s 250th birthday by engaging with 70 of Virginia’s foremost historic sites. The Virginia 250 Passport, which will be available for free at select sites, will offer prizes and discounts to sites and museums.

“Colonial Williamsburg is ready to meet these historic moments our own centennial and our nation’s 250th anniversary and we invite all of America and the world to join us,” said Cliff Fleet, the Foundation’s president and CEO.

The program runs from Nov. 11, 2025, to Dec. 31, 2026. For more information, go to VirginiaHistory.org/250Passport

CUSTIS GARDEN

Colonial Williamsburg has released its conceptual plan for the Custis Garden restoration along Nassau Street. John Custis IV said his was “a garden inferior to few in Virginia.” The timetable for its construction has not been set.

MAKER possibly Thomas Coram

DATE ca. 1780

PLACE Charleston, South Carolina

MEDIUM Silver

DIMENSIONS Height: 2 1 4 inches; Width: 1 3 ⁄4 inches; Weight: 0.6 ounces

BY PAUL ARON PHOTOGRAPHY BY JASON COPES

Precisely how many Americans remained loyal to England during the Revolution is difficult to know (most historians estimate 15% to 20% of the population), but loyalist sentiments were especially prevalent in parts of South Carolina. One measure of those sentiments was the nearly 5,000 men who fought for the British. One of these men, as an officer of the regiment known as the South Carolina Royalists, wore this small shoulder belt plate.

The South Carolina Royalists were formed in 1778 in Florida, where many loyalists from the Carolinas and Georgia had taken refuge. Loyalist forces played key roles when the British captured Savannah, Georgia, in December 1778, and Charleston, South Carolina, in May 1780. The South Carolina Royalists were present when Charleston fell and helped hold Savannah and the South Carolina town with the unusual name of Ninety Six. (The history of the name is not clear.)

“Efforts [were] made to raise other provincial units during the British occupation of South Carolina,” wrote historian Robert Stansbury Lambert, “but only the Royalists attained anything like its authorized strength for an extended period while the war lasted.”

After the war, some, like many other loyalists, moved to Canada.

The plate is the only known Southern example dating from the Revolutionary War. It was used as a buckle either on an officer’s bayonet belt or on a shoulder carriage for a sword. It is not known which officer it belonged to.

Engraved in an exquisite style in the middle of the piece is the Latin motto “sub rege florescit,” which translates to “Under the king it flourishes.” Around the edge is the Anglo-Norman maxim “honi soit qui mal y pense,” which means “Shame on anyone who thinks evil of it.” That phrase is also the motto of the British Order of the Garter, the most senior order of knighthood in Britain.

“It is the only known piece of Southern-made military silver from the Revolutionary War,” said Erik Goldstein, Colonial Williamsburg’s senior curator of mechanical arts, metals and numismatics, “and the motto and sapling pine tree under the royal crown are a perfect metaphor for the Southern loyalist movement.”

Previous owners of the plate did not realize its value. Before being listed in an online auction and acquired by Colonial Williamsburg, it was sold at a garage sale for just a few dollars.

Thomas Coram was an engraver who worked in Charleston when the British occupied the city. He was known to have sought the business of military officers. In an advertisement in Charleston’s Royal Gazette, Coram offered “all kinds of engraved regimental and fancy buttons.”

NEW COLLABORATIONS FOCUS ON COLONIAL CRAFTSMANSHIP

by PETE VAN VLEET

By spring 1769, Virginians had had enough. Britain’s Navigation Acts had mandated that colonists could receive European goods only via England. Earlier, the Townshend Acts of 1767 included taxes on imported lead, paints, glass, paper and tea.

In response, members of the House of Burgesses, meeting at the Raleigh Tavern, created the Virginia Association. Those who signed pledged not just to “discourage all Manner of Luxury and Extravagance” but also to “promote and encourage Industry” within the colonies. In short: Live frugally and, when necessary, buy only what was made in America.

The association, like others up and down the colonies, helped break the bonds with England while also fostering a sense of pride in the expert craftsmanship at home.

Today, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation is continuing that sentiment with two new retail collaborations: Roseland, which is based out of New York and features home furnishings, and Red Land Cotton, which has its headquarters in Alabama and specializes in bedding, bath and apparel.

“Colonial Williamsburg is thrilled to collaborate with Red Land Cotton and Roseland, both of which are part of a new generation carrying the torch for Made in USA craftsmanship,” said Noreen O’Rourke, contract creative director, Williamsburg Brand.

Starting and maintaining a company that produces and relies only on items made in America is no easy task. Beyond the ingenuity and persistence required to produce domestically, there is also the complex puzzle of finding American supply chains, some of which have either dried up or moved overseas.

Both companies are family-owned and operated, and each has worked hard to find manufacturers around the country that share their passion and produce goods they believe people will pass down from generation to generation.

“Roseland started because we have a love of American craftsmanship and history,” said Luke Sherwin, who runs the company with his wife, Clare de Boer.

Choosing to work with U.S.-based manufacturers, he explained, was a no-brainer: “There’s something wonderful about being able to talk to a person who owns a business in the same time zone and have that talk in the same room, ideally, and build a relationship where the stakes are high for both businesses. Symbiotic growth is far more exciting to me.”

He and his wife have a deep affinity for Colonial Williamsburg. He said they “couldn’t get enough” of the buildings, furnishings and artistry in the Historic Area.

“What Colonial Williamsburg and Roseland have in common is celebration of craftsmanship and the American home,” Sherwin said.

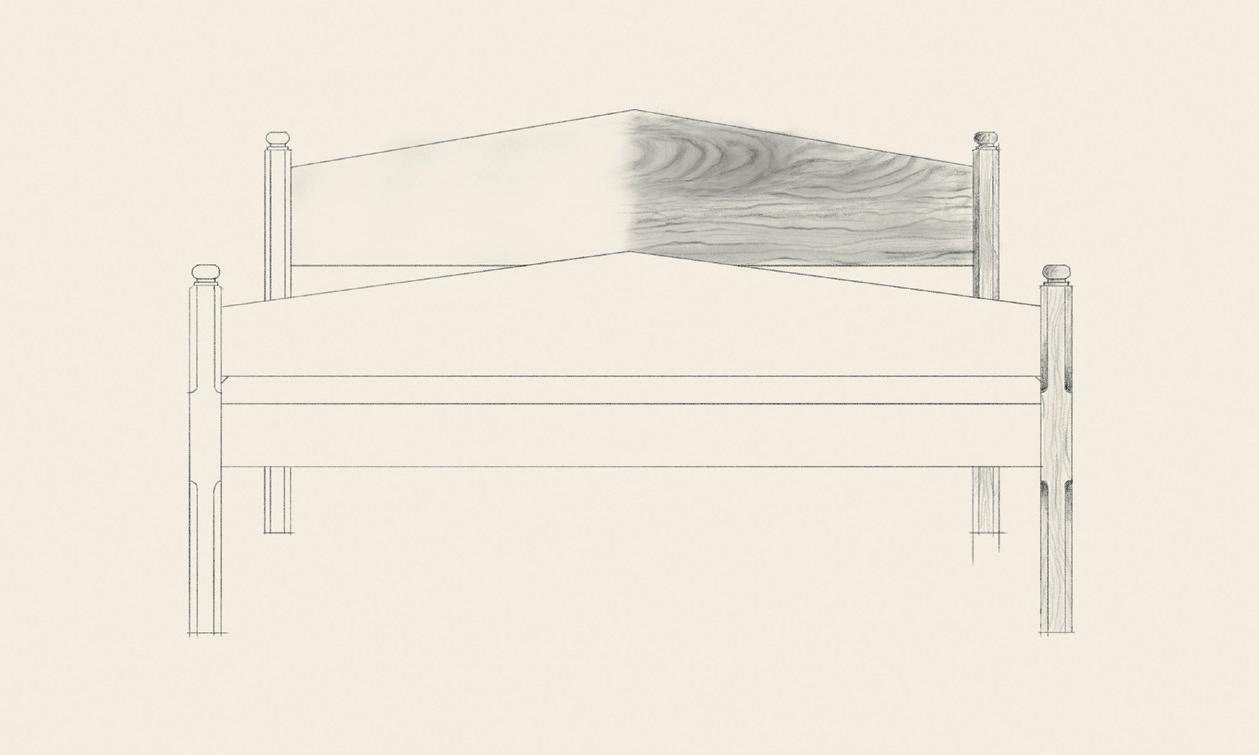

The company is excited to be working on a new bed frame design inspired by the couple’s explorations in the Historic Area, he said.

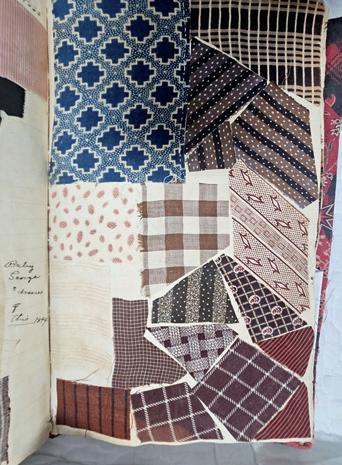

Likewise, some of what Red Land Cotton offers is based on what co-founder Anna Brakefield saw when she visited. Colonial Williamsburg’s archives and detailing at the Governor’s Palace influenced new designs and products.

She hopes that, beyond a quality product, she is also passing along to the customer a sense of pride in America and a bit of knowledge about how things were made here and continue to be made here.

“It’s about education and teaching

(Opposite top) A sketch shows a bed frame designed by Roseland, inspired by visits to the Historic Area. (Opposite below) Samples from Red Land Cotton’s Governor’s coverlet collection sits in the Governor’s Palace. (Above) Red Land Cotton co-founder Anna Brakefield displays the company’s Tavern Gingham blanket and Archival Vine duvet set.

people why there is value here,” Brakefield said. “The educational aspect Colonial Williamsburg brings is an inspiration to us all. In a similar way, Red Land Cotton is trying to reeducate the customer on how things were made. So we are also investing in that education as well.”

Brakefield acknowledges that a driving factor for her and her family is to help the American textile industry thrive.

She sees similarities between the situation the industry is in now and the situation the country was in as the Revolution approached.

“I think 250 years later that it is just as necessary to make your goods at home,” she said. “We are a driving force initiating that for the U.S. And not just bring it back, but bring it back well. It’s just funny how history repeats itself.”

“I made this...”: The Work of Black American Artists and Artisans

Art Museums of Colonial

Williamsburg

“Every Article... suitable for this Country”: Furnishing Early Williamsburg

Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg

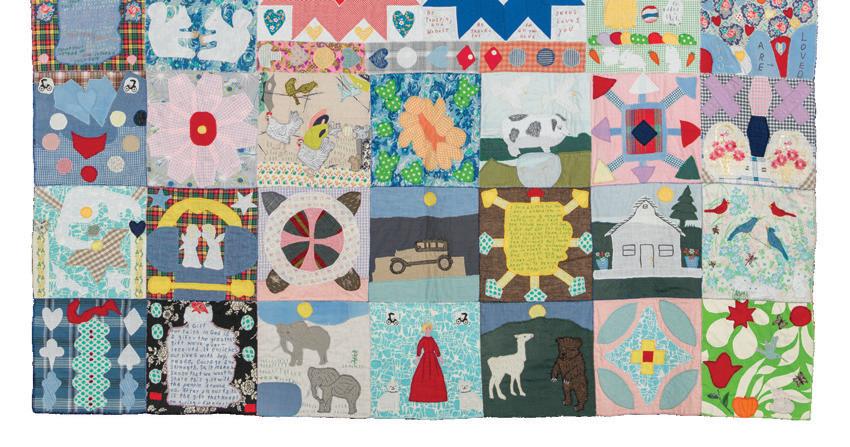

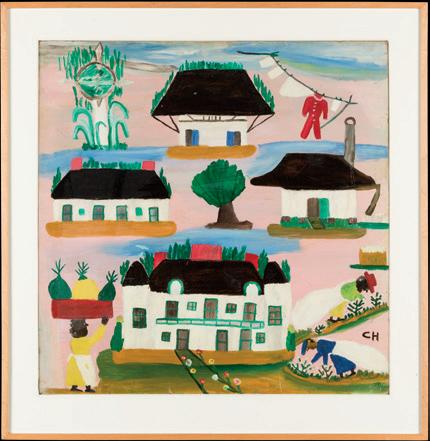

(Left) This quilt by Helen Fleenor is filled with not just colorful scenes but also heartfelt sayings, including “You Are Loved.” (Below) This scrap of wallpaper shows the pattern that decorated the best bedchamber in the Thomas Everard House. (Lower left) Artist Clementine Hunter was known to explore the use of color, which is evident in this painting of the buildings at Melrose Plantation in Louisiana.

The museums have plenty on display to break through the dreariness of winter

PHOTOGRAPHY BY JASON COPES

The dark days of winter are a good time to seek out color and brightness. One piece that is a particularly good example is a quilt on view in Art of the Quilter The piece literally reminds viewers to “Be Happy” and “Be Kind.” Helen Fleenor embroidered these uplifting sentiments on her quilt made up of 56 blocks. Filled with imaginative, colorful designs, the blocks incorporate scenes and animals from the artist’s rural environment in Hamblen County, Tennessee. She included everything from angels based on window decals in her farmhouse to flowers like those in her garden. Fleenor began quilting later in life and made about 20 quilts before her death in 2001.

Another artist who explored the use of color was Clementine Hunter. Born in 1887, Hunter spent most of her life working as a farmhand and cook at Melrose Plantation in Natchitoches Parish, Louisiana. She began painting in her late 50s. Her colorful images record everyday life and the people in her community. Hunter’s painting of Melrose, recently acquired, is on view in “I made this... ”:

The Work of Black American Artists and Artisans . The picture depicts several of the buildings from the estate as well as tasks that Hunter was involved in, such as harvesting crops and doing laundry. Of particular importance to Hunter’s story is African House, pictured at the top of her painting. African House was built around 1815. In the summer of 1955, Hunter spent seven weeks painting autobiographical murals throughout the entire second floor. It is tempting to think of the use of color and pattern as a more modern aesthetic, but the 18th century had its share of both as evidenced in textiles and home furnishings. In “Every Article... suitable for this Country”: Furnishing Early Williamsburg , two small samples of wallpaper found at the Thomas Everard House are on display. Enough of the material survived to reconstruct the full pattern and original color. Everard’s best bedchamber featured the blue wallpaper, while his dining room walls featured the yellow-patterned paper. He likely purchased the wallpaper between 1768 and 1776, when he sent several orders to London.

An outspoken member of the British Parliament and a keen political satirist, John Wilkes was widely known for his opinions on the need for parliamentary reform and the right of free speech. He was also a vocal opponent of Britain’s war against the American colonies, earning widespread popularity across the Atlantic. From 1762 to 1763, Wilkes published a radical weekly newspaper called The North Briton, which attacked the policies of the prime minister at the time, the Earl of Bute The 45th issue of the paper became a lightning rod when it personally attacked King George III, leading to Wilkes’ arrest on a charge of seditious libel. The negative reactions of the king and Parliament garnered Wilkes even more public support, which was reflected in the production of commemorative prints, tokens, glass and ceramics, such as this rare British delft plate.

Made in Liverpool about 1763, the plate is inscribed “Wilkes . And . Liberty . N 0.45.” The likeness of Wilkes copies a 1763 print issued by Johann Sebastian Müller. The object will appear in Colonial Williamsburg: The First 100 Years , an exhibition opening at the Art Museums in February 2026.

The purchase of this plate was funded by Pamela J. and James D. Penny, Ann Berry, Linda Baumgarten, Leslie Grigsby, Liza and Wallace Gusler, Ron and Mary Jean Hurst, Kim Ivey, Martha KatzHyman, Angelika Kuettner, Joseph and Judith LaRosa, Bruce and Barbara McRitchie, Janine Skerry and Ed Moreno, Merry Outlaw, and Tom Savage in memory of John C. Austin, the Foundation’s first curator of ceramics and an internationally known expert on the subject of British delft.

NATION BUILDER KURT SMITH PORTRAYS THOMAS JEFFERSON, AUTHOR OF THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE.

he had

Thomas Jefferson, who would become the third president of the United States, was only 33 years old when he penned the Declaration of Independence. Now, 250 years later, we honor the ideals he shared in that founding document which shaped our nation and the world. To learn more about how to financially support the very place where America’s story began, contact our team at 1-888-293-1776, visit us online or scan the QR code below.

www.colonialwilliamsburg.org/donate

CHALLENGE YOUR PERCEPTIONS . DISCOVER FOOD FRESH FROM THE GARDEN . GET TO THE ART OF IT

First ladies

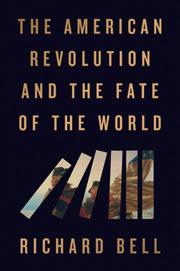

HOW THE REVOLUTIONARY WAR LED TO THE by RICHARD BELL

William Murray, a smooth-talking shoplifter with a taste for gold and silver, usually got away with it. He would stroll into London’s grandest shops dressed like a gentleman, all polished shoes and well-cut coat. By the time clerks realized what had vanished — buckles, earrings, even the contents of the cash box — Murray was long gone. He practiced theft as performance, refining his script until, one day in 1773, when a jeweler recognized him on the street. This time, the law caught up with him.

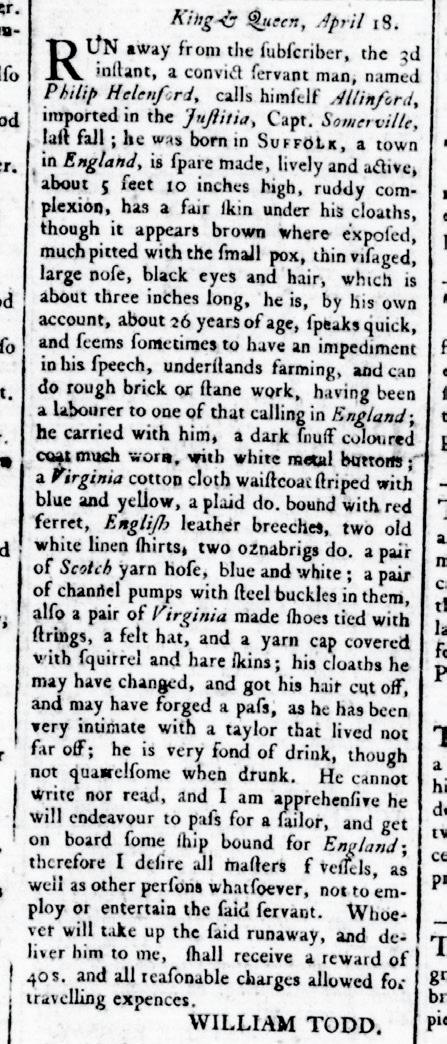

He was sentenced to 14 years of hard labor across the Atlantic, a form of banishment called “transportation.” Shackled aboard the Justitia, Murray was one of 170 felons crammed into the ship’s hold on its voyage to Virginia. He was one of nearly 50,000 convicts shipped to America in the decades before the Revolution.

One woman sentenced to hard labor in the American colonies in 1771 had stolen nothing more than a basin of soup.

(Previous spread) A 1779 drawing shows a chain gang of convicts being loaded onto a ship in London. The practice, called “transportation,” sent criminals to the colonies to serve sentences as indentured servants. (Opposite) Notorious English criminal John “Jack” Shepherd became a cult hero for his ability to escape from jail. Before he was hanged, several prominent members of society asked the king to commute his sentence to transportation so he could avoid death and serve his sentence overseas.

Convict labor was central to Britain’s empire. European powers had long used felons as tools of colonization, from the Portuguese in Ceuta in North Africa to the Spanish in the Caribbean. England was no exception. As Richard Hakluyt had argued in an influential pamphlet back in 1584, why not put “pety theves” to work building forts and felling timber? By the early 1700s, thousands of them had already been banished across the Atlantic, their labor feeding Britain’s navy, mines and tobacco fields.

The practice grew after Parliament’s Transportation Act of 1718, which made exile to America the default punishment for crimes from poaching to forgery. Within a generation, transportation accounted for two-thirds of sentences at London’s Old Bailey. Most of those shipped out were young and poor. Some were serial offenders like William Murray, but the bulk were destitute strivers who had committed crimes of necessity.

When the Justitia reached the Rappahannock River at the southern end of the Chesapeake Bay in March 1774, the captain and crew scrubbed the human cargo and advertised them for sale in the local press. Prospective buyers turned out in droves to poke and prod them and to pepper them with questions about their skills and strength. “They search us there as the dealers in horses do those animals in this country, by looking at our teeth, viewing our limbs, to see if they are sound and fit for their labour,” one remembered. Another recalled being asked “what vile Fact had brought Me to this Shore.”

All this scrutiny revealed potential purchasers’ ravenous appetite for convict labor, their insatiable demand a reflection of the fact that felons filled a crucial niche in the Chesapeake labor market. A convict like Murray cost about 25% more than an indentured servant. But his length of service was likely twice as long, and he cost just a third of the price of an enslaved man. They were long term, cheap and plentiful at a time when deliveries of indentured servants and captive Africans were often inconsistent and unreliable. Contrary to myth, it was not Georgia but Virginia and Maryland that absorbed nearly 90% of Britain’s transported

criminals. In Maryland, they accounted for nearly four in 10 new arrivals. A visitor to next-door Virginia in 1765 called their numbers there “amazing.” Buyers simply could not get enough. Even George Washington bought convicts, hiring them to marbleize Mount Vernon’s columns and renting others to till his fields. Male convicts became indispensable on farms and in forges and foundries, while women labored in domestic service.

However, if many planters valued the convicts’ labor, a vocal chorus of other colonists despised their presence. Colonial critics of the convict trade charged that Britain was turning America into a dumping ground. Benjamin Franklin called them “human serpents” and suggested shipping rattlesnakes back in return. William Byrd II, never one to mince words, called them “Banditti” and begged correspondents in London “to hang up all your Felons at home, and not send them abroad to discredit their country in this manner.”

Byrd was not alone in worrying about crime or rebellion. Governors blamed arson and theft on “transported villains,” and Virginia’s assembly moved to tighten restrictions, barring convicts from land grants, stripping voting rights and eventually attaching hereditary servitude to children born during a convict mother’s term. That 1769 law, a transparent attempt to maximize the value of the woman’s labor contract by blurring the line between convict and slave, decreed that if “any convict servant woman shall be delivered of a bastard child, during the time of her service,” the convict’s master is “intitled to the service of such child, if a male until he shall arrive to the age of twenty-one years, if a female until she shall arrive to the age of eighteen years.”

By the 1760s and 1770s, opposition to transportation had become part of the broader quarrel with Britain. Franklin, John Dickinson and others denounced the practice as corrupting and insulting. Landon Carter, a planter who lived on the banks of the Rappahannock, complained of gaol fever, now known as typhus, spreading from ships.

Pamphleteers lumped in convicts with enslaved Africans as “glorious Importations of Corruption and Slavery.” Local assemblies tried to require ship captains to post bonds as security to allow convicts on shore and imposed various other restrictions. But London blocked every attempt, dismissing each effort as the usual colonial grumbling. For the Crown, transportation was humane, efficient and profitable. Samuel Johnson, a nationalistic English essayist, sneered that Americans were “a race of convicts” who should be grateful for anything short of the noose. The convicts themselves were, of course, caught in the middle. Scorned and feared by some Chesapeake elites but readily bought and exploited by others, they complained of rations as meager as enslaved Africans’ and punishments just as severe. “I was very much discontented,” recalled Jesse Walden, sentenced to seven years of unpaid toil in Virginia. Robert Perkins, another transportee, said his work came with “all the Hardships that the Negro Slaves endured.”

No wonder so many ran. Newspapers were filled with runaway ads describing the scars, accents and trades of those who had taken to their heels. Most fugitives were young men, but women, too, slipped away. Some tried for river ports, hoping to stow away on ships bound for home across the Atlantic. One owner reported that a woman named Mary Davis was “often

Benjamin Franklin CALLED THEM “human serpents” AND suggested shipping rattlesnakes back IN return.

inquiring whether many Vessels lay” at the Rappahannock.

Few escapees succeeded, and most who were caught paid dearly. A Maryland convict, William Green, explained the rule: “If we run away and are again taken, for every hour’s absence, we must serve [an extra] twenty-four, for a day, [we must serve an extra] week, for a week, [we must serve an extra] month, for a month, [we must serve an extra] year.”

Yet, true to form, William Murray, the silver-tongued jewelry thief, managed to beat the odds. In 1775, he slipped back to London after only 18 months abroad, having acquired an American accent and passed himself off as a loyalist refugee under the name William Jefferson. Soon he was back to his old tricks, stealing jewels and riding around town in a fine carriage. Justice again caught up with him in February 1776, however, when he was arrested for a second time, this time on suspicion of stealing a diamond ring. Prosecutors quickly discovered his true identity, and the judge convicted Murray both for the theft and for violating his original sentence. He faced the usual penalty: banishment and hard labor. Ordinarily he would have been sent back across

the Atlantic, but the blockades and embargoes in place since the outbreak of the Revolutionary War had closed the colonies to Britain’s felons. Instead of being banished, Murray was confined to Newgate, London’s already jam-packed central jail.

The American war abruptly severed the transportation system. Britain had relied on its Chesapeake colonies to absorb tens of thousands of convicts. Without them, the jails soon overflowed. Government ministers, reluctant to build new prisons, decided to improvise. They passed the Hulks Act of 1776, a piece of legislation that turned old, abandoned cargo ships languishing in Britain’s rivers and ports into floating jails.

Duncan Campbell, a London merchant who had once shipped thousands of convicts to Virginia and Maryland, now took the contract to manage hulks moored on the Thames including the now wornout Justitia, which had taken William Murray to the Rappahannock only three years earlier.

The conditions aboard these zombie ships were horrific. Prisoners slept chained in fetid hulls, rising each morning to haul and heave in the naval dockyards only to be chained back below decks each night. Disease cholera, dysentery, smallpox soon cut through their ranks. A quarter of the 2,000 men aboard Campbell’s hulks perished, their bodies cast into common graves at the river’s edge.

While Murray and others toiled in fullto-bursting jails and prison hulks, Britain was buckling under the strain of waging its great war in America. Trade collapsed, food prices soared and soldiers returned home to find no work. Petty thefts spiked,

and the courts answered with gallows justice: Hangings in London quadrupled after 1780.

In June of that year, riots convulsed the city. Crowds of angry, unemployed Londoners torched Parliament and besieged Newgate, freeing the prisoners inside. One of them was William Murray, who would remain at large for nine days before being caught again.

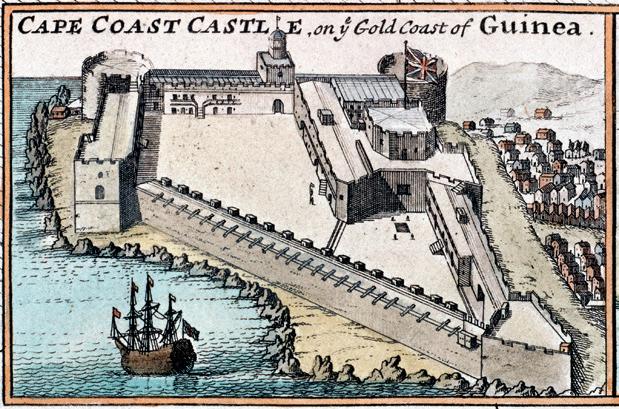

Increasingly desperate, the British government tried all manner of stopgap schemes to restore public order. They even shipped some of the convicts, including William Murray, to West Africa to stand guard over Britain’s 13 undermanned slave forts. But sending Murray to Africa turned out to be a great mistake. Instead of knuckling down to guard duty, Murray talked his way into a command and then turned his garrison into a gang. Ultimately, his insubordination was so flagrant that the fort’s commanding officer ordered his execution.

Murray’s death symbolized the collapse of Britain’s bizarre convict-soldier experiment in Africa and hinted at its failures across the board. By now, the hulks in the Thames River were full and the jails were overflowing. Efforts to restart convict transportation to the Chesapeake in 1783 and 1784 were humiliatingly rebuffed. Everything the ministry tried failed, often spectacularly. By the mid-1780s, government ministers were frantic. “We are the only nation on earth,” one colonial agent in London lamented, “who seem not to know How to dispose of our Criminals.”

Lord Sydney, Britain’s home secretary, was at his wit’s end. With nowhere left to send convicts, on Aug. 18, 1786, he persuaded his fellow cabinet members to select a site in eastern Australia, recon-

noitered by Capt. James Cook back in 1770, to host a brand-new penal colony. Lord Sydney’s plan was simple: Empty the hulks, quiet the streets and banish the problem to the ends of the earth.

The First Fleet sailed in 1787 carrying 1,500 people, the majority of them petty criminals such as a boy caught stealing clothes, a woman who had nabbed bacon and raisins, and a man who had stolen cucumber plants.

The voyage marked the beginning of an 80-year experiment that would send more than 162,000 prisoners to Australia. The convicts once sold into Chesapeake fields and workshops now laid the foundations of another continent’s colonial history.

After the war, Congress barred further imports of British and Irish felons to the newly united states, denouncing the “injury [that] hath been done to the morals, as well as the health” of the country’s citizens. The Virginia legislature eagerly complied. And yet Virginia and other newly independent state legislatures subsequently moved to quietly adapt the logic of penal exile to punish enslaved rebels, deporting Black freedom fighters to Haiti or West Africa or selling them into the Deep South in the decades prior to the Civil War.

Over time, the practice was largely forgotten, barely a footnote in history. Despite that, the fact remains that tens of thousands of Britain’s criminals helped build the colonial Chesapeake. Forgotten, too, is how the sudden end of their forced migration helped give rise to Australia.

To tell the story of William Murray and his contemporaries is to recognize that such marginalized people were central actors in the story of empire and nation allowing for a better understanding of the intertwined origins of America and Australia and the effect the Revolutionary War had on the entire world.

professor

at the University of Maryland, College Park. He received a doctorate from Harvard University. His latest book is The American Revolution and the Fate of the World.

by JEANNE ABRAMS

Martha Washington,

here by

Huntington, has often been portrayed one-dimensionally, but in truth she led a much more politically motivated and complicated life.

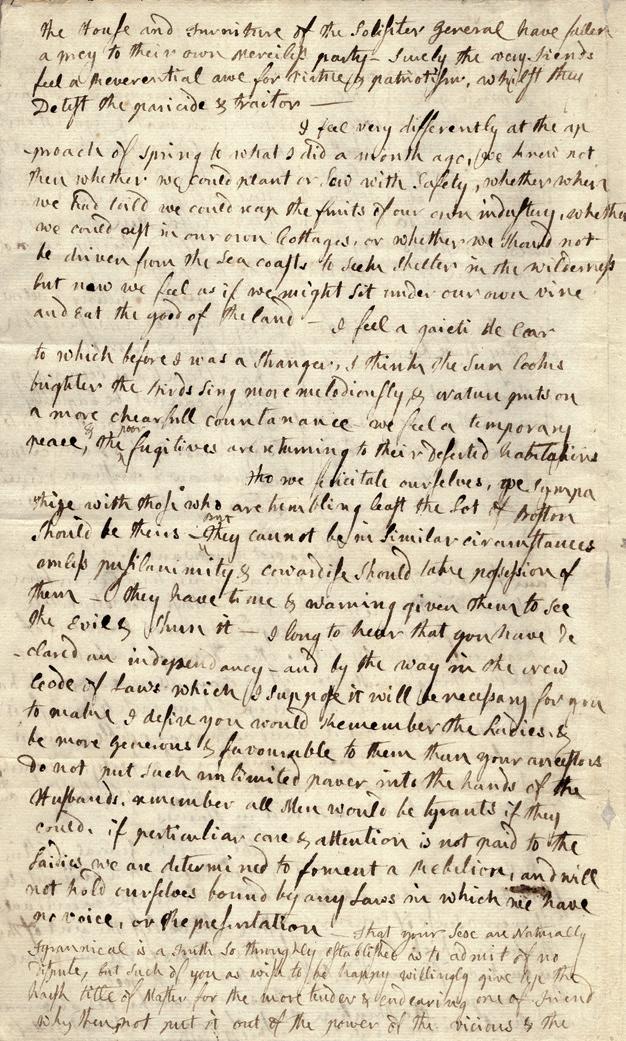

Support for the American Revolution was often a family affair. Long before Martha Washington and Abigail Adams became the first and second first ladies of the United States, they were active participants in the Revolutionary War. Even though women could not vote, hold office or fight, they could transcend boundaries between the public and private spheres and exert influence on the war and the fledgling republic.

The exigencies of war disrupted many normal patterns of settled domestic life, blurring some of the lines that had demarcated appropriate female and male behavior, at times allowing women like Washington and Adams to breach the barrier that had excluded them from the realm of politics.

While Washington and Adams would come to be seen as opposites when it came to the duties, roles and expectations of women, their complicated, sometimes contradictory views demonstrated the complexity of their involvement in the political realm.