Gustave Moreau and Ingres

byPETER COOKE

GUSTAVE MOREAU’S DEBT to Eugène Delacroix has been recognised ever since his first Salon, in 1852, when Théophile Gautier asserted that ‘M. Moreau’s true master is Delacroix’.1 Indeed, until the end of his life Moreau remained haunted by the latter’s sense of expressive colour. The influence of Théodore Chassériau is also well recorded. It was before Chassériau’s fine mural paintings at the Cour des Comptes, in the now demolished Palais d’Orsay, Paris, that he declared to his father his fundamental ambition to ‘create an epic art that is not academic’.2 The remarkable ascendancy that Chassériau held over Moreau for two or three years has been confirmed by the recent discovery of notebooks containing drawings by Moreau executed in a style that cannot easily be distinguished from his mentor’s.3 Although the young artist soon abandoned his infatuated imitation of the latter’s style, he remained faithful to Chassériau’s memory until the end of his life.4

Yet, if Moreau retained his admiration for Chassériau, in his maturity he turned completely against Delacroix, in whose art he then saw a ‘theatrical and falsely, materially overexcited imagination’ and a ‘complete absence of the laws that make the arabesque speak to the eyes’.5 He attacked Delacroix’s drawing and colour as examples of modern decadence, in the nefarious tradition of the Carracci.6 To his ‘insipid rhetoric’, and to the ‘foolishness’of his system of complementary colours, Moreau opposed ‘the Flemish and our good Italian Primitives’.7 For, after his emulation of Delacroix and Chassériau, Moreau had, in the words of Henri Focillon, been ‘touched by the Pre-Raphaelite grace’.8 His conversion to this archaising spiritualist aesthetic helps to account for the low esteem in which he held most of the artists of his time, who, tainted by materialism, had failed to ‘go back upstream to find the true, the beautiful tradition’.9 Thus, in the naturalistic figure painting of‘M., G. and C.’ (almost certainly Meissonier, Gérôme and Cabanel), Moreau saw ‘the complete negation of the only qualities worthy of admiration in an artist: imagination,

1 T. Gautier: ‘Salon de 1852’, La Presse (4th May 1852): ‘Le véritable maître de M. Moreau est Delacroix. Il en procède directement’.

2 A. Brisson: ‘L’ami du peintre’, Le Temps (2nd December 1899), (declaration recalled by Moreau’s friend Henri Rupp): ‘Je rêve de créer un art épique qui ne soit pas un art d’école’. Jean Paladilhe, following an oral tradition, states that Moreau pronounced these words before Chassériau’s decor at the Cour des Comptes; J. Paladilhe and J. Pierre: Gustave Moreau, Paris 1980, p.10.

3 See E. Brugerolles et al., eds.: exh. cat. Quand Moreau signait Chassériau, Paris (Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts) 2005.

4 See S. Patrie: ‘“Ma fidélité au souvenir de Chassériau” (Gustave Moreau)’, Mélanges en hommage à Dominique Brachlianoff, Cahiers du musée des Beaux-Arts de Lyon, special issue (2003), pp.86–91.

5 P. Cooke, ed.: Ecrits sur l’art par Gustave Moreau, Fontfroide 2002, II, p.315: ‘De l’imagination théâtrale et faussement, matériellement surexcitée’; ‘Absence complète des lois qui font parler aux yeux l’arabesque’(hereafter cited as Cooke 2002)

6 Cooke 2002, II, p.316: ‘Toute cette décadence rhétoricienne en dessin et en couleur est, depuis les Carrache, devenue notre seule école d’art’

7 Cooke 2002, II, p.316: ‘une rhétorique insipide’; ‘Ce système de complémentaires, quelle niaiserie! Où sont nos Flamands et nos bons primitifs italiens?’.

8 H. Focillon: La Peinture aux XIXe et XXe siècles, Paris 1991 (1st ed. 1928), II, p.88: ‘il fut touché de la grâce préraphaélite au cours d’un séjour en Italie’.

9 Cooke 2002,I, p.171: ‘remonter les courants pour retrouver la vraie, la belle tradition’.

10 Cooke 2002, II, p.319: ‘Est-ce une illusion? Est-ce une erreur de penser qu’il n’y a pas

caprice and feeling’.10 Paul Baudry’s decorations in the Opéra Garnier (completed in 1874) were characterised by Moreau as ‘the last blow dealt to what is called painting of style’ and as ‘a joke presented seriously’,11 while in his friend Eugène Fromentin’s posthumous exhibition, held at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in 1877, Moreau found ‘a bouillabaisse of Old Masters’ and ‘the triumph of chic’.12 He told his pupil Henri Evenepoel that Manet had ‘a very fine eye’, but ‘a total absence of style’ and ‘detestable matter’,13 while, in a private note, he wrote that Rodin produced hideous ‘gargoyles’, although he recognised in the sculptor ‘a lot of talent, but spoilt by an enormous amount of charlatanism’.14 In Odilon Redon Moreau saw ‘a far from banal brain’, but considered the resulting art ‘sad’.15 These dismissive and sardonic comments by an idealistic painter at odds with the aesthetic trends of his time stand in contrast to Moreau’s more respectful, nuanced and ambivalent attitude towards Ingres. Indeed, Moreau engaged constantly with Ingres’s art, throughout his mature career.

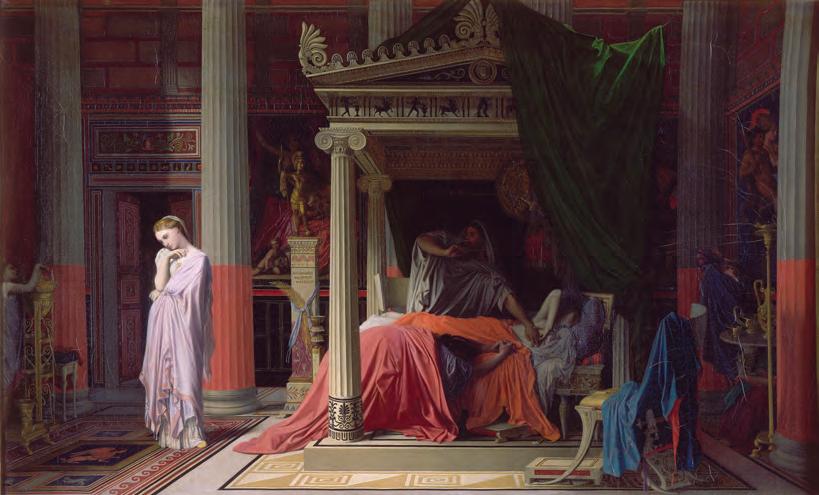

Although commentators have emphasised Moreau’s early debt to Delacroix’s expressive colourism, ‘Monsieur’ Ingres was by far the most important French artist for Moreau and his generation. Ingres’s retrospective at the Exposition Universelle of 1855 had decisively established his pre-eminence.16 Henceforth, he was, as Léon Lagrange put it, ‘the mute champion of the principles of Beauty’.17 Jon Whiteley has explored the contrasting significance that Ingres held for the two most prominent teaching studios of the 1840s, those of Charles Gleyre (who had inherited some students from Paul Delaroche) and François Edouard Picot, under whom Moreau trained.18 While Gleyre’s studio – from which emerged Jean-Léon Gérôme, Gustave Boulanger and other néo-grec painters – was fascinated by Ingres’s Antiochus and Stratonice of 1840 (Fig.10), which offered an exciting new way of conceiving antique subjects, Picot’s studio was enthralled by Ingres’s female nudes, especially Venus Anadyomene (1807–48; Musée Condé, Chantilly) and La Source (Fig.11). Whereas the

d’art, pas de don naturel, rien qui puisse être admiré et qui se puisse juger favorablement dans ces œuvres de M., G., C. et tutti quanti? / On en est arrivé avec cette prétendue conscience dans l’imitation de la nature, dans le genre, l’histoire, le paysage, on en est arrivé à cette négation complète des seules qualités qui soient dignes d’être admirées chez l’artiste: l’imagination, le caprice, le sentiment’.

11 Cooke 2002, II, p.324: ‘le dernier coup porté à la peinture dite de style’; ‘une drôlerie sérieusement présentée’.

12 Cooke 2002, II, p.325: ‘bouillabaisse de maîtres’; ‘le triomphe du chic’.

13 H. Evenepoel: Lettres à mon père, ed. D. Derrey-Capon, Brussels 1994, I, p.320: ‘Manet avait un œil d’une finesse très grande, mais chez lui, absence totale de style et la matière en est détestable!’.

14 Cooke 2002,II, p.332: ‘Gargouilles. [. . .] et avec cela du talent, beaucoup de talent, mais gâché par énormément de charlatanisme’.

15 Evenepoel, op. cit. (note 13), I, p.312 (21st April 1894): ‘Je vois des gens doux et bons comme Mr Redon qui est un sincère, et dans lequel il y a certes le développement d’un cerveau peu banal, mais enfin, quel triste résultat’.

16 See A. Carrington Shelton: Ingres and his Critics, Cambridge 2005, chapter 5.

17 L. Lagrange: ‘La Mort de M. Ingres’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts (1st February 1867), ‘Bulletin mensuel’, p.206, cited in P. Mainardi: ‘The Death of History Painting in France, 1867’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 6/100 (1982), p.219: ‘champion muet des principes du Beau’.

18 J. Whiteley: ‘The Revivalin Paintingof Themes Inspired by Antiquity in MidNineteenth-Century France’, unpublished D.Phil. diss. (University of Oxford, 1972).

young néo-grecs found in Stratonice a colourful vision of antique decor, informed by contemporary archaeology, Picot’s students, who included Bouguereau, Cabanel, Baudry and Lefebvre, sought in Ingres’s nudes models for the perfection of style. Indeed, le style –with which Ingres had become synonymous –was the watchword for high art under the Second Empire.19 As a student of Picot, Moreau remained faithful, throughout his career, to the ideal of le style, and it is only natural that he should have taken a great interest in Ingres’s art. This interest found expression both in Moreau’s writings and in some of his most important paintings. It will be helpful to begin with the former.

Moreau’s esteem for Ingres is evident from an undated note in which he mentions him in the same breath as Poussin and the old masters and the composer Rossini, as an example of an artist reproached with ‘subservience to tradition’ in times of ‘artistic decadence and critical stupidity’.20 Moreau certainly admired Ingres’s drawing, citing him as a master of the ‘epic’ style,21 and, most importantly, he considered him to be a ‘merveilleux érudit, un profond savant en matière de plastique’ – a ‘marvellously erudite artist, profoundly knowledgeable in matters of plastic form’.22

The word plastique, which was a key term in mid-nineteenth century art theory, is crucial to our understanding of Moreau’s interest in Ingres. By plastique Moreau meant artistic form, which, in common with other students of Picot, he saw as one of the essential qualities of painting, as well as sculpture. La plastique found expression both in the individual figure and in the composition as a whole, and is closely allied to the word

19 See, for example, C. Blanc: ‘Du Style et de M. Ingres’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 1/14 (1863), pp.5–23.

20 Cooke 2002, II, p.220: ‘Ce reproche de pastiche, d’imitation, d’absence d’originalité, de servitude pour la tradition, d’attardement et de vieillesse, est adressé, c’est une règle générale, à tout ce qui est vraiment fort et vraiment grand aux époques de décadence artistique et d’hébétement critique. / Voyez Poussin, Ingres, Rossini, et chez les vieux maîtres: tous passent à l’état de fossile et de vieil imbécile aussitôt qu’apparaît une audace nouvelle, vraie ou fausse’.

21 Cooke 2002, II, p.255.

22 Cooke 2002, II, p.313.

23 Cooke 2002, I, p.57: ‘l’évocation de la pensée par la ligne, l’arabesque et les moyens plastiques, voilà mon but’.

24 Marginal annotations by G. Moreau in E. Chesneau: La Peinture au dix-neuvième siècle. Les chefs d’école, Paris 1862, p.272 (Musée Gustave Moreau; inv. no.13388):

10. Antiochus and Stratonice, by Jean-AugusteDominique Ingres.1840. Canvas, 57 by 98 cm. (Musée Condé, Chantilly).

‘arabesque’, which is another key term in Moreau’s aesthetic. Thus, for example, in one of his most important utterances, he claimed that his aim was ‘the evocation of thought through line, the arabesque and plastic means’.23 In crossed-out marginal annotations in a copy of Ernest Chesneau’s Les Chefs d’école, Moreau reacted against Chesneau’s claim that Ingres had abandoned the elevated aims of history painting in order to become a mere ‘chercheur d’arabesques’ with the following comments:

The arabesque, the most [illegible word] part and the most difficult for a painter to attain, the only <most beautiful> means that he has of speaking to the viewer’s imagination and mind. But there is arabesque and arabesque.24

Chesneau’s accusation belonged to a polemic over Ingres’s status as a history painter: was he a great inheritor of the tradition, as his admirers claimed, or had he betrayed the humanist ut pictura poesis ideal in the sterile aestheticising pursuit of what Théophile Silvestre called ‘l’absolu plastique’?25 We do not know which side Moreau took in this debate, but, in his own art, he attempted to combine what he called ‘l’amour pur de l’arabesque’ with allegorisation, art pur with art philosophique 26

In Moreau’s eyes, Ingres –a great master of drawing and la plastique –was bereft of two essential qualities: spirituality and the love of matière. In a note on La Source (Fig.11), which Moreau considered a mere ‘académie (vieux style)’, and in implicit contrast to himself, he stated that Ingres lacked – and indeed never even suspected the existence of – ‘this abstract beyond that transports

‘L’arabesque, la partie la plus [illegible word] et la plus difficile à atteindre chez le peintre, le seul <le plus beau> moyen qu’il ait de parler à l’imagination et à l’esprit du spectateur. Mais il y a arabesque et arabesque’.

25 T. Silvestre: Les Artistes français, Paris 1926 (1st ed. 1856), II, p.18: ‘M. Ingres, ne croyant qu’à la forme, fait de la peinture une voluptueuse et stérile contemplation de la matière brute, professe une indifférence complète pour les destinées de l’homme, pour les secrets de la création, et poursuit au moyen de lignes droites et de lignes courbes, l’absolu plastique’. Moreau possessed a copy of the 1861 edition of Les Artistes français

26 Cooke 2002, II, p.249: ‘L’art est mort le jour où, dans la composition, la combinaison raisonnable de l’esprit et du bon sens est venue remplacer chez l’artiste la conception imaginative presque purement plastique, en un mot l’amour pur de l’arabesque. / Il est bien entendu qu’il est question ici des principes de l’art et de ses bases fondamentales. / Il faudrait croire que sur cet amour de la pure plastique et de l’arabesque peuvent se greffer les plus nobles aspirations de l’âme et les formes les plus variées de la pensée’. On this question, see P. Cooke:

the mind and the soul into the rare and sacred domains of the imagination’.27 This ‘abstract beyond’ was the mystical realm of the sublime that raised art to the level of great poetry and that could only be reached through the imagination. Ingres’s other essential defect, in Moreau’s view, was his ‘mépris profond de la matière’ – his profound contempt for pictorial matter, a fault that he considered ‘essentially French’.28 Ingres’s painting, with its impersonal, uniform, enamelled facture, was bereft of ‘amorous dreamed work’, whereas, in contrast, ‘every corner of a picture by a true master is interesting to the highest degree in terms of the paintbrush’s caress’.29 In this, Ingres was ‘always academic’;30 his ‘impotence of execution’ was, in Moreau’s opinion, a ‘radical vice that must necessarily prevent your work from living’.31 The master’s execution was too facile, Moreau believed, and revealed the absence of ‘this worry before the glimpsed but floating ideal’ that great artists ‘pursue and that preoccupies them even in their execution of details’.32 It is clear, once more, that the implicit contrast here is between Ingres and Moreau himself.

It is evident from the above remarks that Moreau defined his own ambitions as an artist both in comparison and in contrast to his great predecessor. To Ingres’s unrivalled mastery of drawing, la plastique and le style, Moreau wished to add an intensity of execution, a more inspired manipulation of matière, and, above all, the imaginative suggestion of the ‘abstract beyond’. To the romanticisation of Ingres’s style cultivated by Moreau’s former mentor Chassériau, who had sought to combine his master’s sculptural and arabesque drawing with the warmth of colour and exoticism attained by his rival Delacroix, Moreau wished to add another, superior dimension – that of spirituality – while at the same time revelling in the materiality of his art. He put these paradoxical intentions into practice in a series of major works stretching from the 1860s to the 1890s.

Moreau’s manifesto painting Oedipus and the sphinx (Fig.12), exhibited at the Salon of 1864, presented a direct and unmistakable challenge to Ingres, who had treated the same subject over half a century earlier in a celebrated picture (Fig.13). Moreau’s knowledge of Ingres’s painting is confirmed by a small pencil sketch of the picture in one of his books.33 Whereas his companions from Picot’s studio, Cabanel and Baudry, had challenged Ingres in the domain of the female nude with two pictures that dominated the Salon of 1863, The birth of Venus (Musée d’Orsay, Paris) and The pearl and the wave (Museo del Prado, Madrid), significantly, Moreau preferred to launch his challenge on the terrain of narrative history painting; he wished both to establish himself as a renovator of le grand art and to react against the predominance of the mythological female nude at the Salon. The most striking contrast between the two versions of the subject of Oedipus answering the riddle posed by the sphinx lies in the realm of style. The archaism created by the lack of tonal

‘Gustave Moreau entre art philosophique et art pur’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 6/134 (1999), pp.225–36; and idem: Gustave Moreau et les arts jumeaux. Peinture et littérature au dix-neuvième siècle, Berne 2003, pp.62–75 and 90–104.

27 Cooke 2002, II, p.313: ‘Une académie (vieux style) en un mot, exécutée par un merveilleux érudit, un profond savant en matière de plastique. / Mais n’y a-t-il donc rien de plus dans l’art ? Si fait – il y a cet au-delà abstrait qui transporte l’esprit et l’âme dans les domaines rares et sacrés de l’imagination où les génies purs savent et peuvent seuls vous conduire. / Cet idéal-là, Ingres ne l’a jamais connu, il ne l’a même jamais soupçonné’.

28 Cooke 2002, II, p.314: ‘Mépris profond de la matière, défaut essentiellement français’.

29 Cooke 2002, II, p.314: ‘Pas de travail amoureux, rêvé’; ‘Tous les coins d’un tableau de vrai maître sont intéressants au plus haut degré comme caresse d’outil’.

30 Cooke 2002, II, p.314: ‘Académique toujours’.

31 Cooke 2002, II, p.314: ‘votre impuissance dans l’exécution est un vice radical qui doit fata-

11. La Source, by JeanAuguste-Dominique Ingres and pupils. 1856. Canvas, 163 by 80 cm. (Musée d’Orsay, Paris).

modelling that had struck Ingres’s contemporaries when his painting was first exhibited in Paris, in 1808, had been forgotten (and no doubt partly lost when Ingres later reworked the canvas) by the time the picture was rediscovered by Moreau’s generation at the Exposition Universelle of 1855, where it was deemed a work of uncompromising antique style.34 In contrast, all the critics were struck by the quattrocento-inspired archaism of Moreau’s Oedipus and the sphinx, which made its author seem, in the words of Gautier, a ‘posthumous pupil of Mantegna’.35 Thus, for Francis Aubert, ‘M. Ingres’s Oedipus is an antique creation [. . .]M. Moreau’s work is that of an artist of the fifteenth century’.36 This ‘Pre-Raphaelitism’, which puzzled Moreau’s contemporaries in an antique subject, carried religious connotations that indicated the painter’s desire to endow history painting with a sacred dimension, in opposition to the paganism perceived in Ingres and his emulators.37 In terms of the composition, Moreau, no doubt inspired by an antique gemstone, has gone even further than Ingres in binding the two figures together into a sculptural unit, depicting the sphinx actually clinging onto Oedipus’ chest with

lement empêcher de vivre votre œuvre’.

32 Cooke 2002, II, p.314: ‘Rien de ce que les grands artistes ont toujours eu: cette inquiétude devant cet idéal entrevu, mais flottant, qu’ils poursuivent et qui les préoccupe même dans leur exécution de détail’.

33 See G. Lacambre: Gustave Moreau. Maître sorcier, Paris 1997, p.45.

34 See, for example, T. Gautier: Les Beaux-Arts en Europe, Paris 1855, II, pp.149−50.

35 Idem: ‘Salon de 1864’, Le Moniteur universel (27th May 1864): ‘Il a vieilli son style et semble, à plusieurs siècles d’intervalle, un élève posthume de Mantegna’.

36 F. Aubert: ‘Salon de 1864’, Le Pays (13th June 1864): ‘L’Œdipe de M. Ingres est une page antique [. . .], l’œuvre de M. Moreau est celle d’un artiste du quinzième siècle’.

37 See P. Cooke: ‘Gustave Moreau’s “Oedipus and the sphinx”: Archaism, Temptation and the Nude at the Salon of 1864’, THEBURLINGTONMAGAZINE 146 (2004), pp.609–15.

her lion’s claws.38 At the same time, by increasing the proximity of the figures to the maximum, Moreau has enhanced the drama of the encounter, which takes place, above all, in the electric duel of the two gazes. Whereas, in the words of Robert Rosenblum, the ‘radiant wisdom and noble body’ of Ingres’s Oedipus ‘assert the power of reason and beauty over unreason and ugliness’,39 Moreau’s hero opposes the sphinx with the power of his will, manifest in his firm mouth and unwavering gaze.

Most significantly, Moreau has engaged with Ingres’s static composition, in keeping with one of the most important tenets of his own anti-theatrical aesthetic, formulated suggestively in the expression ‘the contemplative immobility of the human body’.40 In this he was building on what Susan Siegfried has termed Ingres’s ‘post-narrative’ strategy, that is to say his eschewal of the traditional techniques of history painting in pictures such as Oedipus explaining the riddle of the sphinx (Fig.13) in favour of a blend of the narrative and the allegorical, created by the ‘rejection of narrative action

38 See M. Halm-Tisserand: ‘La Sphinx amoureuse. Un schéma grec dans l’œuvre de G. Moreau’, Revue des archéologues et historiens d’art du Louvain 14 (1981), pp.30–70.

39 R. Rosenblum: Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, London 1990, p.68.

40 Cooke 2002, I, p.54: ‘l’immobilité contemplative du corps humain’.

41 S.L. Siegfried: Ingres. Painting Reimagined, New Haven and London 2009, p.35.

42 H. Dorra: ‘The Guesser Guessed: Gustave Moreau’s “Oedipus”’, Gazette des Beaux-Arts 6/81 (1973), pp.129–40, esp. p.134.

43 J. Kaplan: The Art of Gustave Moreau. Theory, Style and Content, Ann Arbor 1982, pp.40–41.

44 For a more detailed discussion of this picture, see P. Cooke: ‘Gustave Moreau’s “Salome”: the Poetics and Politics of History Painting’, THEBURLINGTONMAGAZINE

13. Oedipus explaining the riddle of the sphinx, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. 1808. Canvas, 189 by 144 cm. (Musée du Louvre, Paris).

and emotional drama’ and the creation of a ‘suspended action of the moment depicted on the canvas’ that ‘allows multiple interpretations to be projected on the image’.41 Moreau’s Oedipus intensifies this strategy through the incongruity created by the extreme physical proximity of the encounter and the impassive immobility of the two figures. By evoking a sense of oneiric unreality, this incongruity in turn draws attention to the symbolic character of the composition. The latter aspect has been emphasised by the inclusion of emblematic details which comment on the frozen ‘action’. These have been interpreted plausibly by Henri Dorra and Julius Kaplan, although Moreau’s contemporaries proved less adept at reading them. The laurus nobili, or bay, behind Oedipus (the tree sacred to Apollo, symbolising man’s highest achievements) is opposed to the fig tree behind the sphinx –a traditional symbol of lust. In the artefacts in the foreground belonging to the victims of the sphinx, Dorra sees emblems of political power (the crown and purple cloth) and official academic honours (the golden bay), and he considers the jewellery worn by the sphinx to symbolise material wealth. In

149 (2007), pp.528–36.

45 On the new generation of history painters at the Salon in the 1870s, see P. Sérié: Joseph Blanc (1846–1904), peintre d’histoire et décorateur, Paris 2008.

46 Cooke 2002, II, p.341.

47 Cooke 2002, II, p.341: ‘Ces faisceaux de plis superbes, ces nobles et ingénieuses combinaisons dans le jet d’ensemble des draperies, ces beautés de toutes sortes, sans parler des gestes et des nus, cette architecture même qui, malgré un peu de sécheresse et de dureté dans l’exécution . . .’.

48 Cooke 2002, II, p.314: ‘Mais quand vous faites un intérieur réel comme celui de la Stratonice, du Raphaël et la Fornarina, votre ingrisme ou votre impuissance dans l’exécution est un vice radical qui doit fatalement empêcher de vivre votre œuvre’.

49 Cooke 2002, II, p.341: ‘cette architecture [. . .] donne par l’intensité du sentiment et de la

other words, the details signify worldly temptations.42 In the snake crawling up the polychrome column supporting a cinerary urn and the butterfly fluttering above it, Kaplan sees symbols, respectively, of death and the soul, commenting that ‘the escape of the butterfly from the snake echoes the victory symbolized by the laurel’.43 Of course the snake – the biblical serpent – is also a symbol of temptation and sin. All in all, then, it is clear that Moreau sought to surpass Ingres in both the psychological drama and the moral seriousness with which he managed the same subject, while also seeking to spiritualise mythological painting through stylistic allusions to early Renaissance art. It should be added that the intense ‘Venetian’ colour and the rich and varied facture of Moreau’s Oedipus and the sphinx also contrast sharply with Ingres’s style.

Over a decade later, when Moreau returned to exhibit at the Salon in 1876 after an absence of six years, it was with two pictures, a mythological subject, Hercules and the Lernean hydra (Art Institute of Chicago), and a New Testament subject, Salome (Fig.14).44 In the latter painting Moreau once more engaged closely with Ingres, as well as presenting a challenge to the up-and-coming colourist history painters, whose posthumous leader was Henri Regnault.45 This time Moreau situated himself in relation to the tradition of antique interiors that had been revitalised for his generation by Ingres’s Stratonice (Fig.10). Years later, in his reception speech at the Institut de France delivered in November 1890, Moreau expressed admiration for certain aspects of this picture, mentioned in the context of the influence it exerted on his generation, for which it ‘opened new horizons’.46 He praised the ‘bundles of superb folds’, the ‘noble and ingenious combinations in the ensemble of the draperies’, the gestures and the nudes, and ‘even this architecture’, which he criticised for ‘a little dryness and hardness in the execution’.47 In private, he was much harsher in this criticism, mentioning the interior of Stratonice as an example of Ingres’s ‘impotence in execution’.48 Nevertheless, in a very revealing phrase, he found that Ingres’s architecture ‘gives, through the intensity and the passion with which it is treated, as through the chosen tonalities, the sacred impression of antique interiors in almost legendary and fabulous epochs’.49 This is the very impression that Moreau himself had sought to create in his Salome. It is clear that Moreau valued Stratonice more as a creation of the poetic imagination than as an attempt at archaeological reconstruction, thereby assimilating it to his own art. In the same reception speech of 1890, delivered in commemoration of his predecessor at the Académie des Beaux-Arts, the mediocre néo-grec and Orientalist painter Gustave Boulanger, Moreau made an important statement of faith in relation to the question of antique decor and costume. While professing to praise the ‘charm’ and ‘ingenuity’ of Boulanger’s reconstructions of ancient Roman life,50 he objected – in implicit contrast to his praise of Ingres’s Stratonice – that, ‘in the restitution of distant epochs’, the latter had ‘not quite taken sufficiently into account the differences in civilisations, regarding moral habits as also the basis of mores, representing for example a scene from the

passion avec lesquels elle est traitée comme par les tonalité choisies, l’impression sacrée des intérieurs antiques aux époques quasi fabuleuses et légendaires’.

50 Cooke 2002, II, p.344: ‘C’est de 1869 à 1874 que Gustave Boulanger expose plusieurs toiles charmantes d’une grande ingéniosité, des plus piquantes dans les intentions, dans la mise en scène si vivante et si colorée: la Via Appia au temps d’Auguste; la Promenade sur la voie des Tombeaux à Pompéï’.

51 Cooke 2002, II, p.344: ‘il semblerait peut-être que dans les restitutions d’époques éloignées, Boulanger n’a pas tenu tout à fait assez compte de la différence des civilisations, en ce qui touche les habitudes morales comme aussi le fond des mœurs, représentant par exemple une scène au temps de la Rome des Césars, comme il aurait pu traduire un sujet plus rapproché de nous, et

time of the Rome of the Caesars as he could have depicted a scene closer to us in time, despite the scrupulous and learned exactitude of his archaeology’.51 Moreau then proceeded to formulate his own principle of ‘archaeology of feeling, of the imagination’: And yet, it would seem quite simple and natural, at first sight, that historical epochs, which have become almost legendary through their distance in time, can only be represented on condition that poetic feeling alone reconstructs them and gives them a new life.

This archaeology of feeling, of the imagination, was that of Rembrandt, very little in conformity with tradition, inadequate, no doubt, but, despite that, so profoundly true, so Orientaland so biblical.52

It is through this ‘archaeology of feeling, of the imagination’, inspired by Rembrandt, whom Moreau venerated as ‘the poet par excellence’,53 that he reworked in Salome the antique interior

cela, malgré toute l’exactitude si scrupuleuse, si savante de son archéologie’.

52 Cooke 2002, II, p.344: ‘Et pourtant, il paraîtrait assez simple et assez naturel, au premier abord, que des époques historiques, devenues presque légendaires par l’éloignement des temps, ne puissent être traduites qu’à la condition que le sentiment poétique seul les reconstitue et leur donne une vie nouvelle. / Cette archéologie de sentiment, d’imagination, était celle de Rembrandt, très peu conforme à la tradition, il faut en convenir, insuffisante sans doute, mais, malgré cela, si profondément vraie, si orientale et si biblique’.

53 Moreau, quoted in Evenepoel, op. cit. (note 13), I, p.254: ‘Rembrandt! Le divin Rembrandt, le poète par excellence, celui qui a su mettre tant de mystère, de poésie, d’inconnu, d’inattendu et de rareté dans ses œuvres’ (13th January 1894).

15. Study for The daughters of Thespius, by Gustave Moreau. Undated. Graphite on paper, 23.8 by 15.5 cm. (Musée Gustave Moreau, Paris; des.4114).

that had been exemplified for his generation by Ingres’s Stratonice In this, he was participating in a continuing aesthetic debate on the influence of modern archaeology on contemporary art. If, for the néo-grecs and their supporters, the riches of erudition afforded a captivating means of renewal by recreating couleur locale in antique subjects, for more conservative artists and critics the ‘manie archéologique’54 risked destroying the fundamental principles of serious history painting by undermining universality and distracting attention from – or simply omitting – the moral message that the genre was traditionally supposed to convey.55 As Scott Allan has emphasised, instead of reverting to the antique generalisations of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Moreau manipulated architectural and decorative erudition in a novel way, placing it at the service, not of archaeological reconstruction, but of imaginative poetry.56 Moreau thereby created what Victor Segalen aptly called ‘la civilisation Moréenne’.57 Thus, whereas Ingres in Stratonice, and his néo-grec emulators in their antique subjects, had created decor by reference to a uniform style – that of Pompeii and Herculaneum – Moreau assembled the interior of Salome through an extreme form of

54 C. Lenormant: ‘La “Stratonice”de M. Ingres’, in idem: Beaux-Arts et voyages, Paris 1861, p.361.

55 See S. Allan: ‘Gustave Moreau’s “Archaeological Allegory”’, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide (Autumn 2009), see www.19thc-artworldwide.org., accessed 25th February 2014.

56 Ibid

57 V. Segalen: Gustave Moreau, maître imagier de l’Orphisme, ed. E. Formentelli, Fontfroide 1984, p.62.

58 Paris, Musée Gustavee Moreau archives, MS GM 541; cited by G. Lacambre in

eclecticism. Wishing to create what he called a ‘palais fantastique’,58 he drew freely upon his vast visual documentation (conserved in the Musée Gustave Moreau),59 gathering together and fusing a collection of architectural and decorative elements drawn from reproductions of monuments as disparate as Hagia Sophia in Constantinople, the Alhambra of Granada, the Great Mosque of Cordoba and various medieval cathedrals. Historians have also identified motifs from Etruscan, Roman, Egyptian, Indian and Chinese art.60 These very diverse elements have been amalgamated into a coherent style by Moreau’s application of heady colour harmonies, Rembrandtesque chiaroscuro and nervous paint handling. Indeed, the facture of Salome, with its eccentric grattages and numerous flecks of impasto, is Moreau’s riposte to the ‘dry’, ‘hard’ and ‘lifeless’ execution for which he reproached Ingres. At the same time he no doubt sought to surpass Regnault’s bravura colour and facture. Salome’s costume also contrasts with Stratonice’s antique drapery, whose folds Moreau so greatly admired: rejecting the ‘old classical Greek rags’ that had become so outmoded and academic, he put together an extraordinarily rich and eclectic costume, dripping with jewels and decorative and symbolic motifs, which was designed, he explained, to create the effect of a ‘reliquary’, in order to evoke the ‘figure of a sibyl and religious enchantress with a mysterious character’.61 Thus, the eclectic decor, with its multiple borrowings from religious architecture, the sacerdotal costume worn by Salome, the hieratic poses of the figures and the references to the composition of Italian quattrocento altarpieces combine to endow Salome with a mysterious sacred atmosphere.62

Whereas Moreau rejected Ingres’s uniformity of architectural style in favour of this extreme eclecticism, from Stratonice he borrowed – while taking it to far greater lengths – an important technique, the integration of symbolic motifs into the decorative ensemble. For, although at first sight the spectator’s gaze is occupied with the overall impression created by the proliferation of polychrome details in Ingres’s picture, closer inspection reveals the presence of important emblematic elements, notably the sphinx on the mosaic at Stratonice’s feet and the picture of Venus and Cupid behind her, the picture of Hercules behind the group of male figures, and the Gorgon’s head on the shield hanging above the bed. While these motifs play a predominantly narrative and psychological role in Ingres’s picture, underscoring the story of forbidden love (which enjoys a happy ending, it should be noted, as King Seleucis ends up giving Stratonice in marriage to his son Antiochus), Moreau, as has been recognised, has invested his subject with an insistent moral dimension by saturating it with symbols of lust.63 These include a black panther, a multi-breasted statue of Diana of Ephesus, several winged female sphinxes, two statues of Ahriman (the Persian god of evil), peacock feathers, and, at the far left of the picture, a large intaglio engraved with an image of the sphinx holding in its claws the body of a male victim. But, no doubt in reaction to the widespread criticism provoked by his inclusion of ‘symbolic baubles’ in some of his Salon pictures of the 1860s,64 in Salome Moreau has successfully disguised their presence

idemet al.:exh. cat. Gustave Moreau 1826–98, Paris (Grand Palais), Chicago (Art Institute) and New York (Metropolitan Museum of Art) 1998–99, p.148, no.63.

59 For a good discussion of Moreau’s use of visual documentation, see G. Lacambre: ‘Documentation et création: l’exemple de Gustave Moreau’, in S. Michaud, J.-Y. Mollier and N. Savy, eds.: Usages de l’image au XIXe siècle, Paris 1992, pp.79–92.

60 See Kaplan, op. cit. (note 43), pp.59–66; G. Lacambre et al.:exh. cat. L’Inde de Gustave Moreau, Paris (Musée Cernuschi) and Lorient (Musée de la Compagnie des Indes) 1997, pp.108–14; M.-L. de Contenson: ‘Le Moyen Age recréé par Gustave

among the plethora of ornamental details, thereby reserving their discovery to the patience of the committed viewer.

Moreau’s Salome engages with Ingres’s Stratonice not only on the level of the aesthetics of antique interiors and costumes, but also in relation to the theme of the femme fatale and the aesthetics of theatricality and anti-theatricality. Ingres’s demure Stratonice is indeed a femme fatale who has unwittingly cast a charm on the young prince Antiochus, who lies bedridden, dying of his forbidden love for her.65 Like Stratonice, Salome stands upright with modestly lowered eyes. Yet, in contrast to the passivity of Ingres’s figure, Moreau’s protagonist has adopted the powerful gesture of David’s oath-taking Horatii, thereby usurping a sign of male power.66 Her rigid pose, with her head presented in strict profile, is fully hieratic. But, whereas in Ingres’s picture Stratonice’s passive immobility contrasts strongly with the theatrical gestures of the emotional male figures, in Moreau’s all the figures are immobile and impassive, Salome’s rigid and dramatic gesture alone contrasting with the surrounding stasis. A dramatic – but enigmatic – gesture is thereby incorporated into the poetics of anti-theatricality.

On every level, Salome reworks aspects of Ingres’s masterpiece. In opposition to the essentially anecdotal character of Ingres’s

Moreau’, in Lacambre et al., op. cit. (note 58), p.29; and idem: ‘Réminiscences romaines dans l’œuvre de Gustave Moreau’, in ‘L’Invention de l’art roman au XIXe siècle. L’époque romane vue par le XIXesiècle’, Revue de l’Auvergne 553 (1999), pp.231–50, esp. pp.234 and 242.

61 Cooke 2002, I, p.99: ‘Je suis obligé de tout inventer, ne voulant sous aucun prétexte me servir de la vieille friperie grecque classique. [. . .] Ainsi, dans ma Salomé, je voulais rendre une figure de sibylle et d’enchanteresse religieuse avec un caractère de mystère. J’ai alors conçu le costume qui est comme une châsse’.

62 See Cooke, op. cit. (note 44).

antique subject, Moreau has developed to the extreme the spiritualand moral dimensions of his own biblical subject, placing eclecticism at the service of generalisation by creating a poetic nowhere, saturating the decor with moralising symbolic motifs, and underscoring the sacred nature of the New Testament story through hieratic poses and religious architecture.

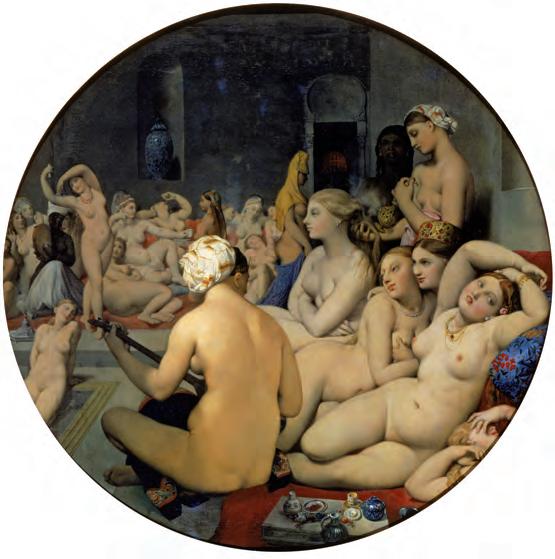

It was not until Moreau’s last Salon that he engaged publicly with Ingres’s female nudes. It is interesting, however, to discuss

63 P.-L. Mathieu: Gustave Moreau. Complete Edition of the Finished Paintings, Watercolours and Drawings, transl. J. Emmons, Oxford 1977, p.124; and Kaplan, op. cit. (note 43), p.60.

64 Thoré-Bürger: ‘Salon de 1865’, Salons de W. Bürger 1861 à 1868, Paris 1870, II, p.204: ‘brimborions symboliques’. On this aspect of Moreau’s critical reception, see Cooke 2003, op. cit. (note 26), pp.62–69.

65 For a good recent interpretation of Ingres’s painting, see Siegfried, op. cit. (note 41), pp.214–35.

66 See Cooke, op. cit. (note 44).

one striking instance of influence prior to that moment, exerted by the culminating expression of Ingres’s lifelong obsession with the female nude, The Turkish bath (Fig.18). A preparatory drawing for Moreau’s second version of The daughters of Thespius (Fig.15) – a disturbing composition in which Moreau has replaced the merely implicit presence of the male gaze in Ingres’s painting with an intrusive and dominating male presence – shows clearly that the painter had studied the arabesque contours of Ingres’s voluptuous nudes. The figure on the far right, in particular, is reminiscent of the figure occupying the same position in The Turkish bath, which Moreau could have seen in Paris at the Khalil Bey sale, in January 1868. In the painted version – a mere esquisse – the Ingresque character of the female nudes is still marked, but the borrowings from The Turkish bath are less evident.67 Galatea (Fig.16), exhibited, together with Helen (current whereabouts unknown), at the Salon of 1880, displays a similar concern for Ingresque contours in the female nude. Here the specific influence is surely derived from one of Ingres’s less well-known paintings, Jupiter and Antiope (Fig.17), a small picture presented at the Exposition Universelle of 1855. Moreau has borrowed from Ingres not only the rounded contours of the nude, presented frontally, while the face is shown in profile, but also the contrast between the dark tones of the alert and desiring male body, gazing through the

67 G. Lacambre: Peintures, cartons, aquarelles, etc. exposés dans les galeries du Musée Gustave Moreau, Paris 1990, no.82. For a discussion of this picture and the earlier version of The daughters of Thespius (or Thestius, to use Moreau’s spelling), see P. Cooke: ‘“Les filles de Thestius” (1853–1897) de Gustave Moreau: “gynécée cyclopéen” ou bordel philosophique’, Revue du Louvre. La revue des musées de France, 4 (1998), pp.64–72.

opening to a cave, and the pallor of the sleeping and desired female body. Yet, whereas Ingres’s picture belongs to the antique and Renaissance tradition of erotic subjects from les amours des dieux, Moreau’s mythological subject, taken from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (XIII, 738–897), has a sinister dramatic edge. Unlike Ingres’s serene Jupiter, Moreau’s grim and staring Polyphemus is a deeply menacing figure. Moreover we know from Ovid that, in his jealousy, the spurned Cyclops will kill Galatea’s lover, Acis, by crushing him under a rock. Whereas Jupiter and Antiope contains no moral dimension, Galatea, with its iconographical allusions to the subject of Susanna and the Elders, can be read on one level as an allegory of lust, a theme expressed with remarkable intensity by the Cylops’ staring eye. Once more, in contrast to Ingres’s smooth uniform facture and limited palette, Moreau has created an extraordinary display of diverse surface effects, with bold passages of grattage juxtaposed with glazes and elegant arabesques of filigree impasto, together with extremely rich colour harmonies.

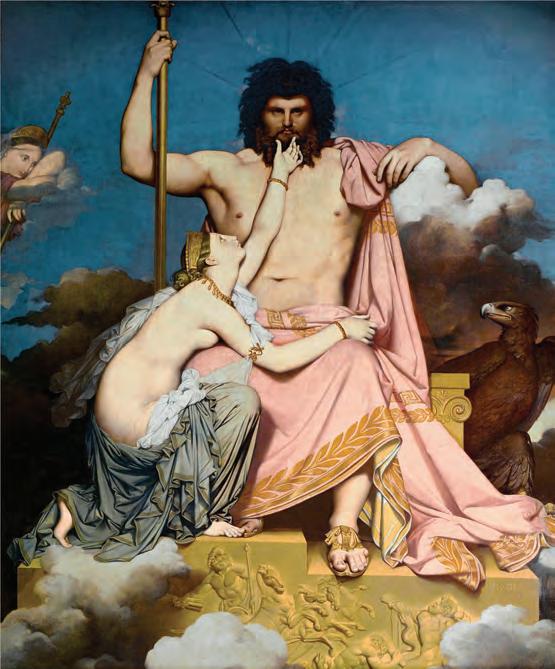

The final example of an individual painting by Ingres with which Moreau engaged directly is Jupiter and Thetis (Fig.19), which Moreau could have seen in 1867, in Ingres’s posthumous exhibition, held at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, and again in 1889, at the Centennale de l’art français (part of the Exposition Universelle).68 Moreau’s first borrowing from this extraordinary picture is superficial: in a delicate watercolour study for The muses leave Apollo, their father, to go forth and enlighten the world (Fig.20) Moreau has adopted the gesture of Thetis caressing Jupiter’s beard and applied it to one of the muses, who is stroking Apollo’s chin, although he has not retained the remarkable form of Thetis’s hand, which Kenneth Clark so aptly describes as ‘half octopus, half tropical flower’.69 In the canvas version, dated 1868, this intimate gesture, which detracts from the solemnity of the scene, has been eliminated.70 Twenty years later, when working on Jupiter and Semele (Fig.21), his last finished masterpiece, Moreau turned once more to Ingres’s Jupiter and Thetis for inspiration.71 Moreau’s debt to Ingres’s composition is evident in the contrast in scale between the frontal, enthroned monumentality of Jupiter and the much smaller, curvaceous form of Semele, draped over his knee. One can see why Ingres’s fantasy of supreme masculine power contrasting with quintessential femininity appealed to Moreau. But whereas, according to the Iliad, Ingres’s Jupiter will yield to the charms of the supplicating and seductive nereid, Moreau’s Jupiter is oblivious to the Ingresque beauty of Semele. According to Ovid in the Metamorphoses (III, 259–315), the beautiful mortal Semele, pregnant with Jupiter’s offspring Bacchus, is tricked by the jealous Juno into forcing her lover, by a binding oath, to reveal himself to her in the splendour of his divine form. Whereupon, although Jupiter takes up his mildest thunderbolts, Semele is destroyed. Jupiter then takes up the foetus of Bacchus and sews it into his own thigh. Using the myth as a mere starting point for a highly original composition, Moreau has turned it into a mystical transfiguration (inspired perhaps by Edouard Schuré’s Les Grands Initiés of 1889),72 in which purified human mortality is transformed into divine essence. In Moreau’s words: ‘Semele, regenerated, purified

68 For a particularly illuminating discussion of Ingres’s painting, see Siegfried, op. cit. (note 41), pp.149–72.

69 K. Clark: The Nude, London 1973 (1st ed. 1956), p.143.

70 See Lacambre, op. cit. (note 67), no.23; and P.L. Mathieu: Tout l’œuvre peint de Gustave Moreau, Paris 1991, no.132, pl.XI.

71 For more detailed analyses of Jupiter and Semele, see J. Kaplan: ‘Gustave Moreau’s “Jupiter and Semele”’, Art Quarterly 33 (1970), pp.393–414; Lacambre, op. cit. (note 67), pp.214–17, no.118; and P. Cooke: ‘Text and Image, Allegory and Symbol in

Study for

by this fire, by this contact, this coronation, penetrated by the divine current, dies thunderstruck in an ineffable and supreme embrace, and with her the spirit of the senses, goat-footed animal and earthly love’.73 Moreau’s spiritualist interpretation of the myth is underscored inconographically by the allusion to the format of the medieval altarpiece. Geneviève Lacambre has in fact shown that the depiction of the enthroned Jupiter with Semele was inspired by the central panel of the Flemish master Jean Bellegambe’s Anchin polyptych (Musée de la Chartreuse, Anchin), representing the Holy Trinity.74 But this allusion to Christian iconography is integrated into a highly syncretic amalgam: the ornate style of Moreau’s Jupiter is distinctly Indian, while his frontal pose is that of a medieval Christ Pantocrator. His left hand rests on Apollo’s lyre, while in his right hand he holds a white lotus flower. An Egyptian lotus adorns his abdomen, just above an Egyptian winged scarab, while his right foot is resting on a coiled serpent. At the foot of his highly ornate throne (once again, distinctly Indian in style) is a lingam, before which sits Jupiter’s eagle.75 The picture contains numerous other mythological and symbolic figures and motifs. Once more, Moreau has taken important elements from Ingres, only to rework them in an infinitely richer and more mystical composition. Stylistically, Jupiter and Semele represents the culmination of Moreau’s experi-

Gustave Moreau’s “Jupiter et Sémélé”’, in P. McGuiness, ed.: Symbolism, Decadence and Fin de Siècle: French and European Perspectives, Exeter 2000, pp.122–43.

72 Kaplan, op. cit. (note 43), p.87.

73 Cooke 2002, I, p.145: ‘Sémélé, régénérée, purifiée par ce feu, par ce contact, ce sacre, pénétrée des effluves divins, meurt foudroyée (dans un ineffable [et mer] suprême embrassement), et avec elle le génie des sens, de l’amour animal et terrestre, aux pieds de bouc . . .’.

21. Jupiter and Semele, by Gustave Moreau. 1889–95. Canvas, 212 by 118 cm. (Musée Gustave Moreau, Paris; cat. no.91).

ments with facture and colour, with its ‘nocturnal’ harmonies dominated by saturated blues, greens and reds, and its highly varied paint surface, enamelled, impasted, and tirelessly worked over.

As we have seen, Ingres was an important point of reference for Moreau. Not only did Moreau find in the art of his predecessor anti-naturalistic models for la plastique, but he was also fascinated by his iconography, especially his depictions of erotic confrontations between male and female figures. But Moreau’s ambition was to surpass Ingres by cultivating – to the extreme –those aspects that the latter had neglected, or rather that were foreign to his nature: the varied materiality of paint handling and the spiritual dimension of the ‘abstract beyond’. At the same time, Moreau intensified the theme of confrontation between the sexes, which he reworked in his own highly charged psychodramas. Ultimately, despite their obvious differences, both painters held in common a quality that Moreau admired in Ingres: audacity.76 They had the courage to develop their own inherent tendencies to the utmost, even when this took them into territory that was so idiosyncratic as to seem weird.

74 G. Lacambre: ‘Un Modèle pour Gustave Moreau: le polyptyque d’Anchin de Jean Bellegambe’, in P. Rosenberg et al., eds.: Hommage à Michel Laclotte. Etudes sur la peinture du Moyen Age et de la Renaissance, Milan and Paris 1994, pp.599–606.

75 For a full iconographical analysis of the picture, see Kaplan, op. cit. (note 71).

76 Cooke 2002,II, p.314: ‘La plus belle qualité de M. Ingres c’est son audace. C’est la vraie qualité qui sauvera son œuvre’.