As we send this issue to print, the Brown University community is reeling from a tragic act of gun violence. Two of our classmates, MukhammadAziz Umurzokov and Ella Cook, were murdered, and nine others were hospitalized. Gun violence is always reprehensible, but to have it happen at our school has shattered any illusion that College Hill is insulated from the violence that has become so common elsewhere. As the Brown community begins the process of healing, we are grateful for the care, energy, and conviction every member of BPR brings to this publication. We hope that this issue offers a moment of reflection—or reprieve—as our community recovers.

In this issue’s special feature, we explore the connection between fiction and politics. Throughout history, humans have created fiction. Myths—spread orally through hunter-gatherer bands—helped early humans explain and understand their world. Epic poems, from The Epic of Gilgamesh to Homer’s The Odyssey articulated cultural values, helped explain what it means to be a human, and provided a framework for different visions of morality. Shakespeare and Cervantes helped people critique politics. From classic literature to science fiction, propaganda posters to online memes, fiction influences our understanding of the world around us and, in turn, shapes the political environment.

A vodou ceremony that took place at Bois Caïman in Haiti in 1791 has served as a foundational myth for when the colony’s subjugated Black population decided to rebel against their French enslavers. As Keyes Sumner describes in “Spirit of Revolution,” this event was harnessed by televangelist Pat Robertson in 2010 to blame an earthquake in Haiti as an act of celestial revenge. The mythical events of 1791 have been turned into a fiction used to ascribe divine rationales for Haiti’s current political treatment.

In the 2015 film Sicario, the United States designates the fictional “Sonora Cartel” as a foreign terrorist organization, authorizing lethal military force to combat the drug trade.

In “Narco Nightmares,” Nicholas Freund traces how the film prophesizes President Trump’s war on drugs nearly a decade later. As the President embraces a more militarized approach, Freund suggests that there may be some lessons in the fictional plot of Sicario about the challenges that lie ahead.

Diella, Albania’s newest cabinet member, is an AI system. Prime Minister Edi Rama has tasked it with automating government services and fighting corruption. While the very concept of an AI minister may seem fictional, Ben Hader argues in “ChatGPT, Fix My Government” that Diella’s anti-corruption

efforts are also fictional. Hader contends that Diella will reinforce the power of Rama while limiting public accountability. Making trust in government a fact, rather than a fiction, requires more than a gimmicky new AI minister.

In “Stolen Vows,” Mitsuki Jiang argues that Kyrgyzstan’s bride kidnapping “tradition” is not as ancient as it seems. While seemingly common, Jiang explores how a fictitious historical narrative about bride kidnapping—known as ala kachuu—normalizes coercion and perpetuates oppression against women. By exposing this fiction, Kyrgyzstan may be able to create space to finally dismantle the practice.

Orbiting self-sustaining space cities may seem like science fiction, but in “Stateless in Space,” Asher Patel argues that increasing space exploration necessitates new legal frameworks for sovereignty in space. Rather than being governed by the terrestrial states that launch the cities into space, Patel makes the case for why these communities must be self-governing.

Today, as journalists and politicians increasingly blur the lines between fiction and facts, we implore you to reflect on the impact of fiction in politics. What do we do when fact becomes indistinguishable from fiction?

EDITORS IN CHIEF

Amina Fayaz

Elliot Smith

CHIEFS OF STAFF

Jordan Lac

Grace Leclerc

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICERS

John Lee

Manav Musunuru

MANAGING EDITORS

Ashton Higgins

Mitsuki Jiang

Sofie Zeruto

CHIEF COPY EDITORS

Tiffany Eddy

Renee Kuo

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Ariella Reynolds

Benjamin Stern

DATA DIRECTORS

Nikhil Das

Tiziano Pardo

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Bath Hernández

Natalie Ho

Fah Prayottavekit

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTOR

Solomon (Solly)

Goluboff-Schragger

WEB DIRECTOR

Armaan Patankar

DIVERSITY OFFICER

Michael Shui

Zander Blitzer

Alexandros Diplas

Allison Meakem

Gabriel Merkel

Tiffany Pai

Hannah Severyns

Mathilda Silbiger

DIVERSITY OFFICER

Michael Shui

DIVERSITY ASSOCIATE

Jiayi Wu

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Ariella Reynolds

Benjamin Stern

DEPUTY INTERVIEWS

DIRECTORS

Ciara Leonard

Eiffel Sunga

Matthew Kotcher

Charlotte Peterson

INTERVIEWS ASSOCIATES

Aleksandra Pakhomova

Amish Jindal

Anita Sosa

Aurna Mukherjee

Charles Lebwohl

Christina Li

Gabriella Miranda

Jack DiPrimio

Maria Mooraj

Matteo Papadopoulos

Michael Lau

Michele Togbe

Nava Litt

Raghav Ramgopal

Rishabh Rao

Riyana Srihari

Rutva Brahmbhatt

Sarik Gupta

Sofia Segarra Wilber Anteroladata

DATA DIRECTORS

Nikhil Das Tiziano Pardo

DATA ASSOCIATES

Aavin Mangalmurti

Amy Qiao

Anna Wong

Brandon Yu

Breanna Villarreal

Ishaan Jain

Jeffrey Gao

Joshua Reed

Reina Jo

Romilly Thomson

Wesley Horn

Zoe Weissman

Fanny Vavrovsky

DATA DESIGNERS

Carys Lam Yeonjai Song

WEB DIRECTOR

Armaan Patankar

WEB DEVELOPERS

Hao Wen

Jaideep Naik

Joanne Ding

Nitin Sudarsanam

Shafiul Haque

WEB DESIGNERS

Casey Gao

Hyelim Lee

Zairan Liu

PUZZLE DIRECTOR

Matthew DaSilva

PUZZLE DESIGNERS

Ana Vissicchio

Lucy Bryce

Marissa Scott

CHIEF COPY

EDITORS

Tiffany Eddy

Renee Kuo

MANAGING COPY

EDITORS

Nicholas Clampitt

Vivian Chute

COPY EDITORS

Aditya Krishnan

Annika Melwani

Charlotte Peterson

Christina Li

Damiana Harper

Daniel Shin

Eva Dillon

Isabela Perez-Sanchez

Jason Hwang

Kaylee Gilbert

Leah Freedman

Lillian Castrillon

Michaela Hanson

Natalie Tse

Nate Barkow

Rachel Loeb

Rachel Sang

Ryan Choo

Shant Ispendjian

Shiela Phoha

Vanya Shah

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTOR

Solomon (Solly)

Goluboff-Schragger

MULTIMEDIA PRODUCERS

Audrey Gmerek

Becky Montes

Chompoonek (Chicha)

Nimitpornsuko

Christina Charie

Clara Baisinger-Rosen

Danielle Deculus

Ella Podurigiel

Ellie Wu

Erin Ozyurek

Josué Morales

Leyad Zavriyev

Lucas Da Silva

Lucy Previn

Lynn Nguyen

Maison Teixeira

Miranda Mason

Nava Litt

Oona O’Brien

Romi Bhatia

Sophie Mueller

Thomas Foley

Xavier Colon

Zarah Hillman

PODCAST DIRECTOR

Caroline Cordts

BUSINESS DIRECTORS

John Lee

Manav Musunuru

BUSINESS ASSOCIATES

Elina Coutlakis-Hixson

Lizzie Duong

Mariana Copeland Celaya

Neve O’Neil

Jack DiPrimio

Becky Montes

Arjun Puri

Remi Takahashi

MANAGING EDITORS

Ashton Higgins

Mitsuki Jiang

Sofie Zeruto

SENIOR EDITORS

Aman Vora

Brynn Manke

Julianna Muzyczyszyn

Keyes Sumner

Steve Robinson

Tess Naquet-Radiguet

EDITORS

Allan Wang

Annabel Williams

Ava Rahman

Chris Donnelly

Daphne Dluzniewski

Emily Feil

Fabiana Conway

Faith Li

Gus LaFave

Isabella Xu

Joshua Stearns

Kenneth Kalu

Madeleine Connery

Mateo Navarro

Meruka Vyas

Nicolaas Schmid

Rohan Leveille

Sara Amir

HIGH SCHOOL

PROGRAM LEAD

Brynn Manke

Tess Naquet-Radiguet

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Bath Hernández

Natalie Ho

Fah Prayottavekit

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Jiabao Wu

EDITORIAL DESIGNERS

Anna Wang

Dongha Kwak

Jay Moon

Marie You

Sheeon Chang

Tiffany Tsan

PUBLIC RELATIONS

DESIGNERS

Kyuwon Park

Jordan Kinley

ART DIRECTORS

Angela Xu

Burcu Koleli

Larisa Kachko

Leslie Mateus

COVER ARTIST

Sarah Naidich

STAFF WRITERS

Aaditya Das Narayan

Alexia Lara

Alina Calix-Martinez

Andrea Fuentes

Arjun Puri

Asher Patel

Audrey Gmerek

Ben Hader

Charlie Getman

Chiupong Huang

Christina Charie

David Macario

Emily Pan

Emily Schreiber

Emma Phan

Fanny Vavrovsky

George Weiler

Gui Sequeira

Isabella Collins

Kayla Morrison

Kimaya Balendra

Lauren Kozmor

Lev Kotler-Berkowitz

Matthew MacKay

Mia Reyn

Michaela Hanson

Nainika Sompallie

Nate Barkow

Napintakorn (Pin) Kasemsri

Natalia Baños Delgado

Remi Takahashi

Riya Singh

Sabine Cladis

Siyuan (Michael) Shui

Shane Vandevelde

Shant Ispendjian

Sonya Rashkovan

Will Thomas

Samdol Lhamo Sichoe

Zern Hee Chua

ILLUSTRATORS

Airien Ludin

Amelia Jeoung

Angelina So

Anneke Beth

Awele Chukwumah

Christina Xu

Cora Zeng

Elizabeth Chew

Ellie Lin

Emily Chao

Emily McShane

Haley Maka

Jiwon Lim

Kexin Huang

Lily Engblom-Stryker

LuJia Liao

Lydia Smithey

Mia Cheng

Mot Tuman

Oli Bartsch

Orla Maxwell

Paul Li

Ranran Ma

Rokia Whitehouse

Shay Salmon

Sofia Schreiber

Wanxin Li

York Mgbejume

Kyuwon Park

On College Hill, visibility is built on the erasure of those who once lived here

by Isabella Xu ’28, an International and Public Affairs and Sociology concentrator and Editor for BPR

illustrations by Amelia Jeoung ’26, an Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

Sunlight pours through sliding glass doors, pooling across the leaves of a fiddle-leaf fig and the gentle curves of a midcentury modern chair. On days like these, the doors are left open so that the sprawl of The RealReal-scouring students, artists, and professionals can sip their lattes out on the sidewalk and take in the view: an entire neighborhood of similarly decorated, similarly inhabited cafés, coworking spaces, and bookstores.

In recent years, gathering spaces like these have emerged in nearly every city, becoming key sites for in-person community-building in our isolated digital age.

College Hill has no shortage of these spaces. Ceremony and Madrid Bakery’s soaring glass walls dissolve the boundary between interior and street, flooding the space with natural light and autumnal hues.

Pass by India Point Park, 195 District Park, or even the Michael Van Leesten Pedestrian Bridge on a summer weekend, and you will find crowds practicing outdoor yoga in full view of passersby.

“Coffee Exchange was established after a huge community made up of primarily Cape Verdean immigrant families was displaced from their homes along Wickenden Street.”

These bodies, stretched in a downward dog backlit by Narragansett Bay, are a living tableau of wellness and leisure.

These public parks are what urban scholars call “third places,” meant to be freely occupied when not at home (the “first place”) or work (the “second place”). But in urban planning, nothing really comes free. Their occupants are those who can afford to live nearby. They have the aspirational lives that park and urban architecture are designed to center.

In philosopher Michel Foucault’s conception of the panopticon, visibility is a tool of control. The prison guard’s tower commands a view of every cell; the inmates, never sure when they are being watched, internalize this surveillance and discipline themselves.

But the design of College Hill’s gathering spaces inverts this logic entirely. Passersby do not monitor the people inside sipping matcha lattes and typing on MacBooks—they desire to

join them. The glass walls are oversized vitrines, flaunting the café as a breathing exhibition of yuppie intellectualism. To be seen is the whole point. To be visible in these spaces is to signal that you belong to a particular class of people. You are creative, leisurely, and culturally fluent. Not every community gets to be visible without consequence. In fact, many of today’s third places sit on land once home to Black and brown neighborhoods later erased through midcentury urban renewal due to implicit, heavily racialized understandings of spatial capital.

In 1946, Rhode Island passed the Community Redevelopment Act, forming the Providence Redevelopment Agency (PRA), one of the first of its kind in the United States. Four years later, the Slum Clearance and Redevelopment Act gave the PRA the right to acquire private homes through eminent domain in “blighted areas.” Many of College Hill’s most popular spaces were built on this displacement. India Point Park and the 195

District Park were the direct outputs of the “traumatic” I-195 relocation project, which displaced over 80 businesses and six residences.

Coffee Exchange was established after a huge community made up of primarily Cape Verdean immigrant families was displaced from their homes along Wickenden Street. Brown Bee’s mahogany-paneled walls warm Benefit Street only after government-accelerated gentrification. While the dominant narrative is that these communities were priced out by student housing, the upcharge on Fox Point homes actually began as a direct response to the threat of the PRA razing down the neighborhood for urban redevelopment. Affluent College Hill residents formed the Providence Preservation Society (PPS) to designate Fox Point as “historic.” This designation piqued the interest of private and public buyers, who bought out the neighborhood and reintroduced it to the market at unprecedented high prices.

Even the lesser-known Oak Bakeshop, about a 25-minute walk past Andrews Commons, is a testament to the racial undercurrents dictating which neighborhoods are considered “blighted.” The bakery, popular for Jewish pastries served on antique china, sits in the former Lippitt Hill area where residents were vacated following a 1962 development proposal.

To the then-residents, Lippitt Hill felt vibrant and livable. In a 2017 community oral history, former resident Deborah Tunstall reminisced, “We had a fish man, oil man, rag man, fruit man, and an ice cream man…We were poor but we didn’t know we were poor,” to the agreement of her former neighbors. It housed the rare sense of community that 20-somethings flock to Manhattan’s East Village in search of. The entire neighborhood was a third place.

So where did the residents of Lippitt Hill go? In St. Louis, Baltimore, Chicago, and even our comparably pint-sized Providence, residents were forcibly relocated into public housing projects—colloquially known as “the projects.”

Armed with new construction technologies, 1950s urban architects constructed brick highrises with the intention of shielding occupants from the sight of passersby. Fluorescent lights, flickering from chronic disinvestment, replaced bay windows. The towering design isolated residents vertically, stacking families to make spontaneous sidewalk conversations and front-porch socializing impossible. Access was funneled through limited entry points, each checkpoint a potential surveillance site, while police circled the perimeter. Public housing residents become transparent to the state while simultaneously opaque to the public.

According to American University professor Derek Hyra’s Slow and Sudden Violence, architectural concealment of Black residents was an explicit strategy to combat white suburban flight and incentivize downtown business investment. The logic is painfully simple: White people perceive Black people gathered together as a threat. Lippitt Hill’s amenities would have been celebrated as walkable, diverse, and vibrant if

“Public housing residents become transparent to the state while simultaneously opaque to the public.”

occupied by white bodies. As it was, 650 homes were destroyed for not being “wholesome.”

Their residents were moved into public housing projects like Hartford Park. Featuring four 10-story high-rises, Hartford Park was a public marvel when it opened in 1953 as America’s first public housing project with an elevator. However, due to neglect and disinvestment, conditions grew unlivable by the 1970s. Other public housing around the city, like Manton Heights, the Chad Brown Apartments, Admiral Terrace, Codding Court, and Sunset Village, suffered the same fate.

Gradually, the harms of this architectural strategy were recognized. In 1968, Congress prohibited the construction of new high-rise public housing. An applaudable initiative began: to renovate the projects into liveable, centralized communities.

In Providence, the neighboring Chad Brown and Admiral Terrace apartments underwent a $16.5 million renovation from 1986 to 1989, constructing a park between the two apartments for

its residents’ use. Complete with picnic tables, lawns, and two recently installed playgrounds, the complex seemingly lives up to its self-proclaimed title of “A Family Community.”

While the restructuring of low-income housing from vertically stacked to suburban and walkable is a definite improvement, a closer examination of Chad Brown’s layout reveals the limits of its liberatory promise.

The renovated courtyard design realizes Foucault’s panopticon even more literally than earlier high-rises. The apartments are arranged around a central gathering space, creating the exact architectural formation Foucault describes. Residents gathering in the courtyard are observable from surrounding management windows and security stations positioned to overlook the space. Visibility flows inward.

Unlike Ceremony’s glass walls, these courtyard gathering spaces remain architecturally opaque to passersby. They are sandwiched between public housing buildings, visible only to other tenants. The renovations created spaces for

the congregation, yes, but only for those already contained within the project boundaries.

Geographical location reinforces architectural containment. Chad Brown, Codding Court, Hartford Park, and Manton Heights remain tucked away from College Hill life. They are spatially segregated from the city’s most aspirational, trafficked areas.

The PRA cannot erase the haunts of 1950sera displacement. Photos plastered on its website of Hartford Park feature all the iconography of suburbia; mature trees, quaint green signage, two-story buildings, and even a silver SUV. But the original, ten-story Hartford Park still stands. It towers over its 1980s successors as a reminder that our government hid congregation done by Black and brown bodies. Back on College Hill, the highly visible architecture of our most beloved gathering spaces highlights the paradox that we, unlike College Hill’s displaced residents, get to be seen.

by Chris Donnelly ’28, an Applied MathematicsEconomics concentrator and Editor for BPR

illustrations by Carys Lam ’29, an Architecture major at RISD and Data Designer for BPR

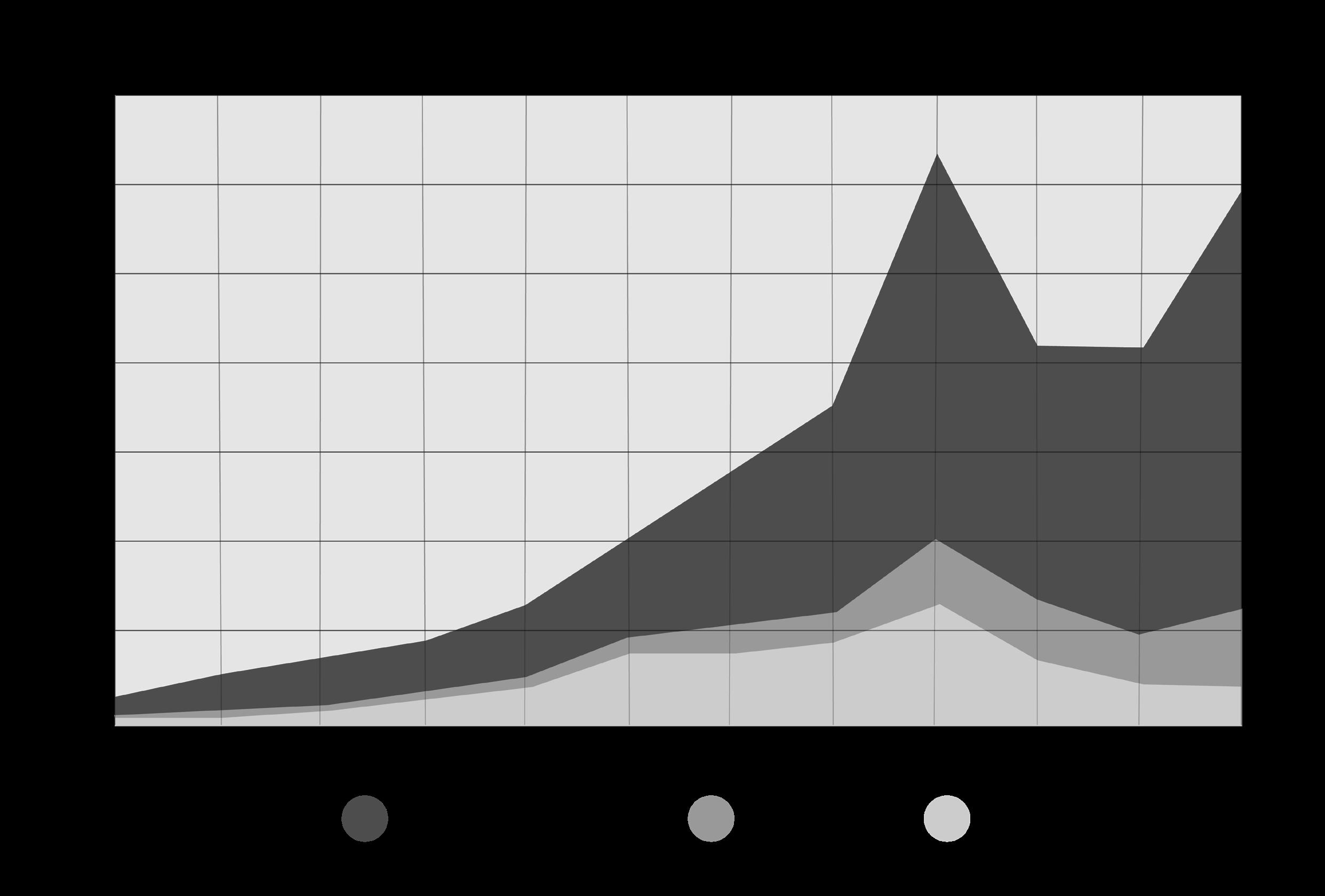

The AI wave rippling through the US economy has raised both excitement and alarm. As an immense amount of capital changes hands between companies in the industry and investments in AI make up an increasing share of US GDP growth, some analysts now predict an AI bubble. While there have previously been disruptive paradigm shifts like cloud computing and cryptocurrency, what distinguishes this paradigm shift is the way in which AI investment has become an industry-sanctioned band-aid on an otherwise bleeding US economy. Despite bubble speculation and potential overvaluation, AI has emerged as a flawed but essential driver of innovation and economic renewal in a country that desperately needs it.

To understand the implications of AI’s recession-cushioning capabilities, it is important to analyze the American economy more broadly. Since taking office in January 2025, President Donald Trump has announced double-digit, country-specific tariffs on America’s top trade partners alongside an array of sector-wide policies, including a declared 100 percent tariff on patented pharmaceutical products from companies that do not rely on US manufacturing. The administration has also toyed with, adjusted, and rolled back promises to use tariffs to coerce Mexico and Canada into strengthening border security earlier this year.

“The disproportionate role of AI growth in the GDP growth has elicited both skepticism and conviction from the investors and individuals spearheading the AI movement. ”

At the same time, the US job market has experienced a recent slowdown, with the unemployment rate reaching 4.4 percent in September: the highest since October 2021. The Federal Reserve System has even tried to ward off an employment crisis through cuts to the federal funds rate. Volatile tariffs, combined with the Fed’s passive “wait-and-see” approach to the unemployment landscape, have brought the future of the US economy into question.

US economic growth, however, does not show signs of stagnation. The S&P 500 has grown 16 percent from January through October 2025, nearly 6 percent above average returns over the past 70 years. The political factors that should be creating shortfalls within the US economy are outweighed by a dominant force: AI spending.

In 2024, well before this year’s mega-deals between leading tech companies, the US private AI investment market alone was valued at $109.1 billion. Only a year later, Nvidia, the chipmaker

powering much of the AI ecosystem, is valued at nearly a third of US GDP growth this year.

The disproportionate role of AI growth in the GDP growth has elicited both skepticism and conviction from the investors and individuals spearheading the AI movement. Deutsche Bank reported that the AI boom could produce an $800 billion separation between revenues and investments that would plunge the economy into a deep recession. OpenAI CEO Sam Altman also explained in August that he believes investors are “overexcited about AI,” which can lead to recession-inducing bubbles. Others, however, believe the opposite, with investor Michael Pecoraro arguing that leading AI companies are creating “actual demand” by generating “real revenue” through long-term contracts with customers.

Despite concerns about overvaluation, there is a general sense of hope for AI’s role in the future. Altman explained that “AI is the most important thing to happen for a very long time,” and he’s right. On even the least developed end of AI, the fact that individuals have created a system capable of learning, understanding, and developing new ideas independent of human guidance makes it commensurate with the invention of the wheel or the discovery of the double helix. In this sense, even if the current AI products are overvalued, the tidal wave of investment will provide essential scaffolding for a technology that could mark the next chapter of human civilization. Beyond AI’s social implications, even a potential bubble creates meaningful economic benefits. Venture capitalist Hemant Taneja asserted that

although such a bubble could create economic upheaval, it would distill the AI landscape to the companies innovative and resilient enough to survive and change the world.

Considering its social and economic significance, our understanding of AI’s economic impact needs to be reframed. While the current landscape may resemble a bubble, any suspicion of overvaluation can only be confirmed if such a bubble bursts. Until then, discussions surrounding AI should revolve around its clear promises for the future instead of the current market frenzy. Not only does the technology serve as an economic catalyst for growth and a beacon of innovation in an otherwise stagnant US economy, but it could also represent a new chapter in human progress.

Interview by Sofia Segarra ’29

Illustration by Kaitlyn Stanton ’26

Brown University Professor Emeritus Peter Howitt, co-architect of the theory of sustained economic growth through creative destruction and co-recipient of the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, discusses the journey that led him from sorting wool in Ontario to reshaping the global landscape of economic thought. With long-time collaborator Philippe Aghion, Howitt developed a mathematical framework that helps to explain the ways innovation fuels growth while rendering older industries obsolete. Howitt discusses the intricacies between technological progress and social disruption, and why creativity, educational innovation, and competition policy are essential for equitable productivity in a highly globalized, AI-driven period. His story invites us to imagine systems where innovation uplifts rather than excludes—a lesson that extends beyond economic or academic thought into everyday life.

Sofia Segarra: You earned degrees in both political science and economics, yet macroeconomics has remained your central inspiration. What led you to pursue a dual degree and make macroeconomics your primary focus?

Peter Howitt: I became interested in economics in high school while working for a wool importer in my hometown of Guelph, Ontario. I was captivated by the constant price changes coming in on his teletype from places like Buenos Aires and Australia. He told me if I wanted to understand those movements, I needed to study economics—so I did. At McGill University, an honors degree in economics required pairing it with another field, so I chose political science, which made sense because economics and politics are so hard to separate. My interest shifted to macroeconomics in my final year at McGill after a course on Keynes’ General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money. That interest deepened when pursuing my master’s at Western University, where Joel Freed introduced me to Bob Clower’s Keynesian work. My path in growth theory solidified when I met Philippe Aghion, my future co-author and fellow Nobel laureate. He brought microeconomics, I brought macroeconomics, and our collaboration clicked from the start, lasting 35 years.

SS: You’ve expressed frustration with older economists resisting new developments in macroeconomic theory and empirical research. Do you think those early experiences shaped how you teach, mentor, and stay open to new thinking?

PH: It taught me what I didn’t want to become. The economic theory I worked on, which is fairly mathematical, is a young person’s field. People can make good contributions, but beyond the age of about 70, they don’t appreciate what happens at the frontier. Thinking about creative destruction reinforced this: Young innovators naturally challenge the older ideas that established previous generations’ reputations, and it’s easy for older scholars to dismiss that “new-fangled nonsense.”

were less creative than their US peers. Creativity is essential today, and these strengths help explain why the United States continues to lead in cutting-edge technology.

A third important policy for maintaining our leading edge is competition policy. Industries shouldn’t be dominated by technological leaders who were once disruptive upstarts but are now doing things that block the next generation of disruptive upstarts. We need incentives to ensure today’s leaders innovate to stay ahead rather than to block the next generation of competitors.

“Technological change always devalues some jobs but boosts productivity in others. Policy can incentivize firms to adopt technologies that enhance workers rather than replace them.”

SS: You began collaborating with Philippe Aghion in 1987. How did that close partnership shape your joint theory of creative destruction, and how did it influence your path as a leading researcher in economic growth?

PH: I have done all of this work with Philippe. Our skills and personalities complemented each other very well. His encouragement kept me grounded in focusing on growth theory as my curiosity pulled me in many directions; without that, I might have never accomplished what I did.

SS: ‘Creative destruction’ describes how innovation brings creation and loss, as advancements render older industries obsolete, impacting workers and entrepreneurs. How can policies be restructured to help individuals thrive within these cycles of creative destruction, especially in such a globalized world?

PH: In regard to labor market policy, a useful model for it is the flexicurity system, combining a strong social safety net with retraining programs, so workers displaced by innovation can transition efficiently into emerging industries, allowing them to benefit from technological advancement. Technological change always devalues some jobs but boosts productivity in others. Policy can incentivize firms to adopt technologies that enhance

SS: You’ve emphasized that technological change—especially with artificial intelligence—should enhance work and productivity rather than replace labor. How can we achieve this when AI often risks reducing productivity, livelihoods, and even creative thinking?

PH: We don’t know what AI’s full impact will be. As a general-purpose technology, it can transform many industries. Some predict it will cause mass unemployment, but history shows that new technologies often create new occupations and can benefit labor as much as capital. There’s no guarantee this will happen, but I hope AI will complement workers instead of replacing them. Early on, these technologies don’t raise productivity because there’s a long shakeout period—heavy investment with little immediate output. It may take decades to see who truly benefits. Technologies that seem poised to replace skilled workers often end up making them more productive. For example, AI tools in medicine can summarize research and suggest treatments to enhance the work of doctors.

SS: How can we foster an atmosphere between universities, private industries, and government institutions that ensures that technological innovation drives economic growth and addresses broader sociocultural and political challenges?

“In advanced economies like the United States, Europe, and Canada—where growth relies on leading-edge innovation—you need creative thinkers. Brown successfully fosters this way of thinking; its students were among the most creative I taught.”

workers rather than replace them, which is done in some European countries, and makes it harder to fire long-time workers, pushing firms toward productivity-enhancing innovations instead of labor-replacing ones. There are many ways to steer technology toward benefiting workers and minimizing losses so we all benefit in the end.

Regarding education policy, it depends on the country. In advanced economies like the United States, Europe, and Canada—where growth relies on leading-edge innovation—you need creative thinkers. Brown successfully fosters this way of thinking; its students were among the most creative I taught. Although the United States scores lower on international tests, many top-performing international students I taught

PH: In the United States, progress has often come from the government spearheading coordination and setting standards, like the Department of Agriculture’s work with land-grant universities, which drove major productivity gains, or the Department of Defense’s role in funding early computer research during the IT revolution in the 20th century. Universities and businesses need to collaborate, although there’s always a risk when academia gets too close to industry. Still, working on real-world problems can lead to breakthroughs, as shown by Bell Labs’ partnerships with academic researchers, which led to Nobel Prizes. This is the best path forward.

Edited for length and clarity.

by Nate Barkow ’29, an International and Public Affairs and Education Studies concentrator and a Staff Writer and Copy Editor for BPR

illustrations by Oli Bartsch ’26, an Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

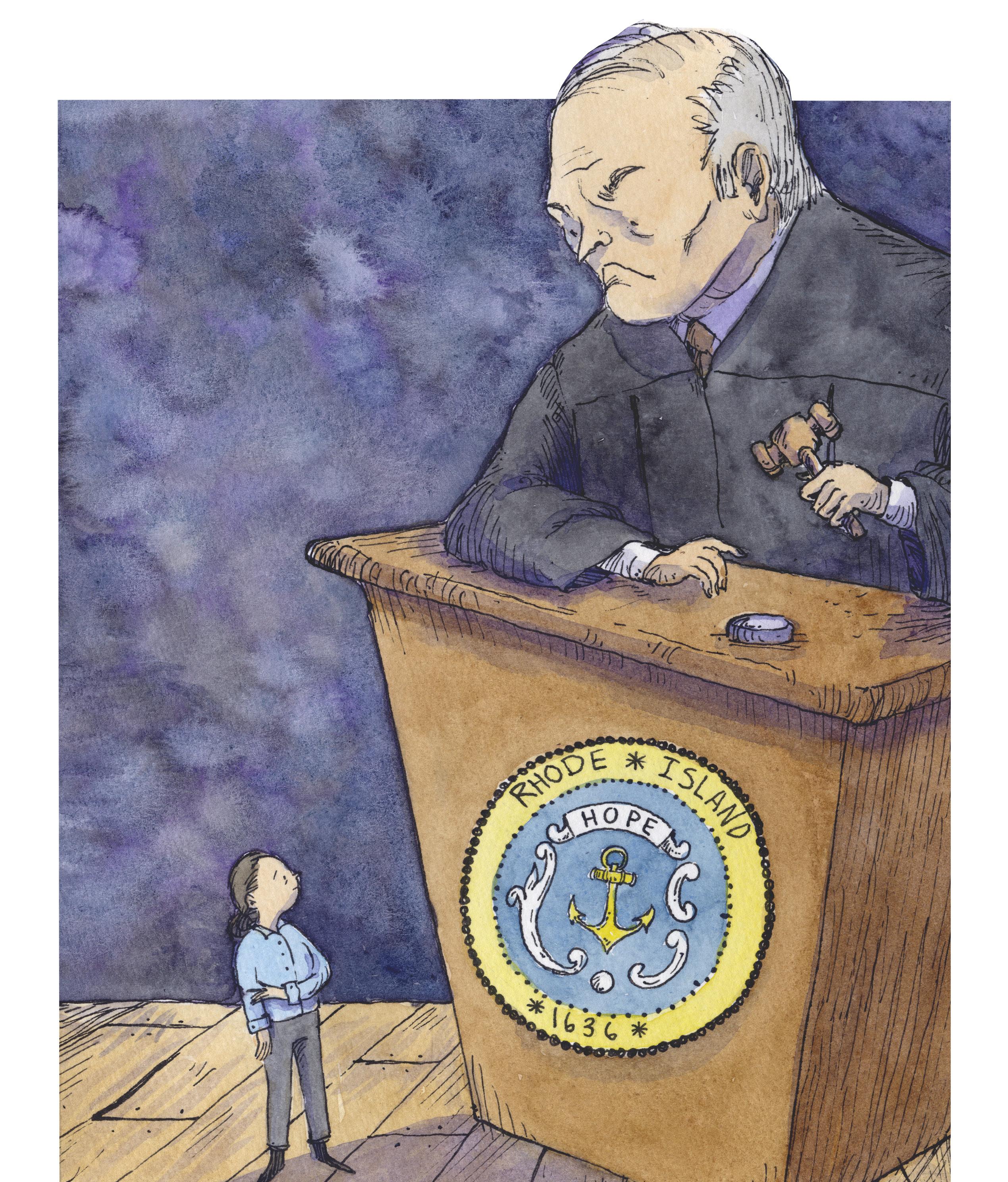

If you experience domestic violence, a victims’ compensation fund should defray the medical and legal costs of victimization. If you are deemed the wrong kind of person, however, Rhode Island’s victim compensation fund will turn you away. Rhode Island is one of only seven states that ban people with criminal records from receiving assistance from victim compensation funds, alongside Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, and Ohio. Despite its reputation as a progressive state, Rhode Island is out of step with other liberal states when it comes to helping victims of crime who may themselves have a criminal record. For a state whose motto is “Hope,” denying compensation based on criminal history is unacceptable. Reforming these policies is crucial for all victims to receive the help they need.

Victim compensation funds exist in all 50 states and are important sources of relief for people who have experienced the trauma of a crime. The federal government supports 75 percent of the funding, and states provide the remaining funds, typically through fines and fees levied on criminal defendants. Victim compensation funds commonly provide relief for often

“Rhode Island’s victim compensation system equates a person’s past mistakes with present guilt, effectively blaming victims for their past and not allowing them room to grow after subsequently facing harm themselves.”

substantial medical and burial expenses that are not otherwise covered by a victim’s insurance. Victim compensation funds do not just help current victims: They may also stop cycles of violence and prevent the creation of new victims in the future. A report from the Center for American Progress notes that people are less likely to commit harm against others if they receive the support they need to heal from their own victimization.

However, the process of obtaining victim compensation is challenging. According to a 2022 poll conducted by the Alliance for Safety and Justice, 96 percent of victims of violent crimes across the United States were not given support from victim compensation funds. Fewer

than 50 percent of crime victims and survivors submit reports to law enforcement about what happened to them, precluding their ability to obtain compensation in most states. Many are unaware that victim compensation funds are an option for them; even if they are aware, many lack the necessary resources to apply for the funds because the application requests an abundance of often difficult-to-find information. In fact, just over 6 percent of people who were victims of crime actually applied for compensation in 2023.

The distribution of victim compensation is often based on subjective views of law enforcement about who deserves help rather than the objective strength of a case of victim need. The

“Restrictions on fund access based on prior convictions are especially unforgiving for victims of genderbased violence.”

many hurdles to obtaining relief exacerbate the obstacles victims already face in recovering from their trauma. A state committed to recognizing and legitimizing the experience of victims must ensure that it provides compensation without needless bans or so many impediments to relief that victims do not bother with the process of applying.

Despite being known as a relatively progressive state, Rhode Island has some of the nation’s most restrictive rules for people seeking assistance after being victimized. Regardless of the nature of the crime that they have suffered from, victims must report it to the police within 15 days. Those with a violent conviction in the past five years, or any criminal record at all, may be denied relief. The legislature of Rhode Island

even rejected a proposal to have the state cover funeral costs for victims, whether they had a criminal record or not.

Restrictions on fund access based on prior convictions are especially unforgiving for victims of gender-based violence. Victims of gender-based violence often delay contacting police because reporting their experience can lead to escalated violence in their relationship. If this delay exceeds 15 days, Rhode Island will deny compensation. People—especially women—in abusive intimate relationships may be coerced into aiding and abetting their abusers’ crimes, thereby obtaining a criminal record. Of the 24 percent of relationships that involve violence, almost half involve reciprocal violence, where both parties might find themselves with criminal

records, but the relationship is characterized by a power imbalance where one of the parties is driving the abuse. If those coerced partners or the vulnerable party in a reciprocally violent relationship seek compensation for the violence they have experienced, they will not receive aid from Rhode Island’s fund.

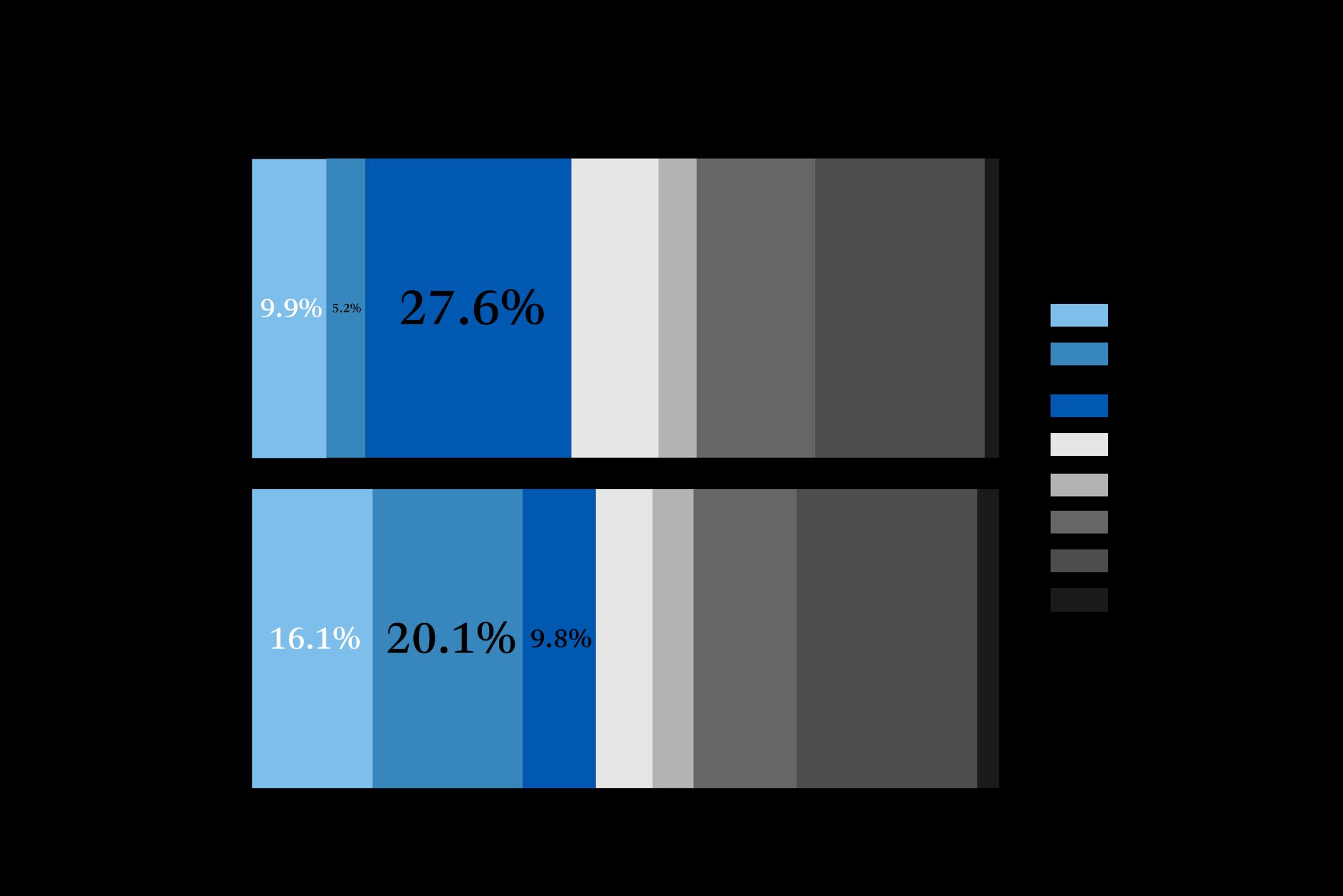

These bans also disproportionately harm Black communities. Black Rhode Islanders may have an augmented number of prior records because of structural barriers to employment, housing, transportation, education, and healthcare, coupled with discriminatory policing practices that target their communities to a higher degree than others. Despite making up 14 percent of the population and being equally likely to use drugs when compared with white

people, Black people make up one in four of those who are arrested for drug-related crimes. Black Americans are 5.9 times more likely to be incarcerated than white Americans. In Rhode Island, Black people make up 15.3 percent of the population, but they accounted for 33 percent of all arrests in 2019. A ban on people with criminal records thus ends up targeting people of color, compounding existing inequities.

Rhode Island’s victim compensation system equates a person’s past mistakes with present guilt, effectively blaming victims for their past and not allowing them room to grow after subsequently facing harm themselves. It is time for Rhode Island to join states like Illinois, Maryland, and New York that have

reformed their victim compensation regimes in the last four years. Maryland and New York no longer require victims to make a police report to receive compensation. A referral from a social service provider to the victim compensation fund can be sufficient, thus helping those victims (especially those who have experienced intimate partner violence) who are reluctant to go to the police. As a state that prides itself on progressive values, Rhode Island should be joining the states that are leading on this issue because it is also a matter of racial and sexual justice.

Rhode Island should reconsider its ban on individuals with criminal records, allow victims to report their harms to service providers

other than the police, and make sure its victim compensation application process is userfriendly. Enacting these measures will help break cycles of violence and harm.

When it comes to providing relief for victims, Rhode Island unfortunately stands out as one of the few states to punish crime victims for their past. Rhode Island should reform its compensation regime and join other states that are leading the way by compensating victims regardless of their criminal records. In doing so, they would recognize that even those with past convictions can suffer victimization and should receive help.

“There will be no West if this continues,” professed Elon Musk on X in September 2025. The crisis in question was none of the usual suspects—climate change, nuclear war, autocracy—but rather dropping fertility rates. Musk, to his credit, has personally endeavored to solve this problem one kid at a time: He is believed to have fathered 14 children. Unfortunately for the United States, his abundance of offspring remains an anomaly; the total fertility rate (TFR) in the United States sits at 1.6, significantly below the requisite replacement rate of 2.08 at which populations can sustain themselves.

Musk’s concern is valid. Failing to address this problem will burden government finances and stall economic growth. Consider the already-struggling Social Security program: Assuming the TFR holds at 1.6, the 2099 annual balance (the difference between revenue and expenditure as a percent of taxable income) will be -7.39 percent. Using the present-day 12.4 percent tax as a baseline, at the current TFR, Social Security taxes would have to rise by 59 percent just to maintain current benefits. At replacement TFR, taxes would still rise but by only 28 percent. That is just one program: Over the next century, an economic downturn driven by a falling population will exacerbate government debt

obligations and increase the burden of an aging population. While this population-driven economic crisis might be alleviated through immigration, massive demographic shifts will likely generate backlash.

As such, President Donald Trump has advocated for pronatalist policies designed to increase birth rates. Options on the table have included $5,000 baby bonuses to parents or the establishment of $1,000 “Trump accounts” for each baby born between 2025 and 2028.

by

Aman Vora ’27, an Applied MathematicsEconomics and Computational Biology concentrator and Senior Editor for BPR

illustrations by Mot Tuman ’26, an Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

Intuitively, these policies make sense: We should be making it easier for people to have kids. But the policies proposed by Trump are unlikely to change the behavior of those choosing not to have children and will redirect money away from true cost-saving initiatives. It costs nearly $400,000 for a middle-class family to raise a child in the United States; $5,000 is little more than a distraction masking sky-high childcare and education costs. Even Hungary, which spends a staggering 5.5 percent of its annual GDP on pronatalist transfer payments, has seen birth rates fall after initially rising.

In the United States, many lower- and middleclass women (whose reduction in child-bearing has led to most of the recent decline in TFR) simply do not want more kids, making a TFR rebound nearly impossible despite incentives. Much of the reduction in TFR has resulted from a 23 percent fall in unplanned pregnancies since 1993. Likewise, the number of pregnancies per 1,000 females aged 15–17 has fallen from 75 in 1989 to just 11 in 2020. In this context, the only cost-effective means of raising fertility is social regression: banning abortions and reducing access to sex education and contraceptives. Baby incentives will fail as long as their proponents misunderstand the scale of the

problem. We can look back to the 18th century to find a similar dilemma. Back then, English economist Thomas Malthus predicted that population growth would far surpass food production, resulting in mass starvation and death. No such die-off occurred, despite the exponential population growth observed across the 19th and 20th centuries. Although our current problem is of an opposite nature, we can find a solution in the same mechanisms that prevented Malthus’ mass die-off.

Ultimately, it was technology that prevented the prophesied Malthusian hellscape. New technologies allowed us to industrialize food production to keep up with population growth. From agronomist Norman Borlaug’s ‘Green Revolution’ to the Internet, technology has improved productivity and, by extension, the consumption per capita measure of wellbeing.

“Worrying about a suboptimal population catastrophe decades away is simply not pragmatic, and, as such, learning to live with an aging population may be the optimal strategy.”

However, even if AI ends up influencing the world no more than other recent technological innovations like laptops or smartphones, the current breed of pronatalist policies will still offer limited returns. Governments will be better off investing in cheaper healthcare (especially at the end of life) and better support for the elderly. Medicare, for example, highlights that variations in healthcare costs render any fertility-sensitivity considerations null. For a fertility bump of 0.1, the 75-year deficit decreases by just $425 billion. If healthcare costs grow 1 percent faster than expected? An incomprehensible $15.99 trillion will be added to the 75-year deficit, dwarfing the Social Security fertility sensitivity considered earlier. Preventative health care, emphasis on primary care networks, and reduced drug costs will all go far in preventing such additions to the deficit.

Scholars have long recognized this overstated problem: In 2022, Norwegian demographist Vegard Skirbekk wrote that if we appropriately reassign capital investment to educating a slimmer workforce and invest in women’s labor force participation, “we can decline and prosper.” Likewise, Professor David Weil wrote that “much of the worry about sub-replacement fertility is overstated. Quantitatively, the net effect of even a large fertility reduction on the US economy would be a relatively small decline in the standard of living.” Even with fertility drops, students will continue to gain advanced degrees at similar rates, preserving the majority of innovation and growth along the technology frontier.

In the 21st century, technological advances— chiefly AI—will drive overall economic growth, preventing dependency- and debt ratio-driven spending crises. Suppose AI does indeed achieve the potential efficiency increases ascribed to a $5 trillion Nvidia valuation. In this case, labor will become significantly more productive, possibly mitigating any economic decline associated with a reduced labor force. McKinsey and Goldman Sachs both estimate that AI will add between 0.5 and 3.4 percentage points to productivity growth by 2075. The Wharton School estimates that AI will raise living standards by 3.7 percent by then. If the median estimates hold true, a decreased fertility rate will no longer be the problem it is currently made out to be.

Historically, economic growth has been a product of both pushing the technological frontier and an increasing population. The US labor force, though projected to continue growing through 2060, must recognize that overall growth will not keep pace with historical trends, but so long as debt is kept in check, standards of living will. GDP per capita, not GDP alone, is what matters. Some economic theory even suggests that “slower population growth can be expected to increase the ratio of capital to labor, which in turn will increase the level of per capita income.” In essence, a smaller, more equal population may, in the short run, be able to leverage an excess in capital per capita for more education and more well-being.

Worrying about a suboptimal population catastrophe decades away is simply not pragmatic, and, as such, learning to live with an aging population may be the optimal strategy. A focus on balanced budgets, affordable childcare, quality education, and reduced healthcare costs—while keeping an eye on the supposed “AI revolution”—will be best. Even if your definition of the purpose of humanity is to be fruitful and multiply, ultimately, a leaner, more efficient human population might be the one better adept at managing climate change or preserving social cohesion as AI becomes more widespread, maximizing human utility in the long run.

In the latter half of 2024, the US public was introduced to the acronym ‘Make America Healthy Again’ (MAHA), a play on President Donald Trump’s ‘Make America Great Again’ (MAGA) slogan. Far from a gimmick, MAHA has become a powerful political movement, encompassing a diverse coalition of weight-loss influencers, Joe Rogan listeners, and “crunchy moms,” shaping both public health policy and parenting discourse. To achieve this mainstream recognition, MAHA elevated mothers to the forefront of the movement, exploiting gendered myths about maternal instinct to bolster its legitimacy.

MAHA originated with Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s endorsement of then-presidential candidate Trump in 2024. With this move, Kennedy, the black sheep of the most prominent Democratic political dynasty in the United States, brought his base of health-conscious anti-establishmentarians into the MAGA faithful. To many who recognized the harms perpetuated by the current food and drug industries, this union seemed bizarre but perhaps suggested bipartisan hope. Yet mainstream coverage of Kennedy’s eccentricities overshadowed a troubling, decades-long commitment to furthering unsubstantiated vaccine skepticism, which undeniably lies at the root of his critiques of the scientific establishment and takes precedence over meaningful systemic reform efforts.

Kennedy’s first foray into health policy was his 2005 Rolling Stone article “Deadly Immunity.” In the now-retracted article, Kennedy alleged collusion between “Big Pharma” and the

by Emma Phan ’28, an International and Public Affairs and Economics concentrator and Staff Writer for BPR

illustrations by Lydia Smithey ’27, an Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

Centers

and Prevention (CDC) to cover up a supposedly causal link between vaccines and autism. From 2015 to 2023, Kennedy chaired Children’s Health Defense, a health misinformation and anti-vaccine advocacy group that has attempted to link chronic childhood conditions to vaccination, water fluoridation, and wireless communications, among other “toxins.” He also penned the 2021 bestseller, The Real Anthony Fauci, which, alongside vaccine denialism, promotes HIV/AIDS denialism and Covid-19 conspiracies.

Despite opposition from a coalition of over 75 Nobel Laureates, 17,000 doctors, and 87 civil society organizations, Kennedy was confirmed as the US Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) in February 2025. On the day Kennedy was confirmed, Trump issued an executive order establishing the MAHA Commission, with Kennedy as its chair. The commission was tasked with examining the potential dangers of prescription medications as well as researching the origins of childhood diseases and mental disorders.

As the MAHA Commission and HHS began to focus on children’s health, women became more prominent members of the movement.

Core to the appeal of the “MAHA Moms,” as these women have become known, are deeply entrenched societal beliefs about the essential goodness, intuitiveness, and protectiveness of women and mothers, which transcend political parties. The idea that mothers have a gut instinct is practically ubiquitous—think of the stories of mothers sensing that their children are in danger, only to be proven correct soon after.

The myth of maternal intuition frames a mother’s subjective perceptions as inherently trustworthy, ignoring social, cultural, and emotional factors that may lead to incorrect judgments. This phenomenon is employed throughout the MAHA movement to amplify unscientific and conspiratorial beliefs. Mothers are convinced that their anxieties about omnipresent risks to their children are valid because they are mothers with special maternal instincts.

Take our culture’s unfounded suspicion of “chemicals”—a term many use to refer to artificial, man-made substances. The MAHA movement exploits and expands this fear of “chemicals,” dubbed chemonoia, to convince mothers that poisons—such as fluoride in drinking water—are everywhere in their children’s daily lives. To MAHA proponents, good mothers can sense that “chemicals” are unnatural and

therefore dangerous for their children.

Even when scientists and doctors reassure them otherwise, MAHA moms must not relent, as their biological wisdom trumps the medical establishment.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, researchers studying the proliferation of anti-vaccine content on social media found that narratives of good motherhood were strategically employed to encourage vaccine refusal. Those pushing anti-vaccine rhetoric employed three interrelated tropes of motherhood, which the researchers identified as the “‘intuitive mother,’ the ‘protective mother,’ and the ‘doting mother.’” In

“Core to the appeal of the “MAHA Moms,” as these women have become known, are deeply entrenched societal beliefs about the essential goodness, intuitiveness, and protectiveness of women and mothers, which transcend political parties. ”

employing the trope of the intuitive mother, anti-vaccine activists covet maternal intuition “an innate form of wisdom,” over the professional knowledge of medical experts, who are framed as the unintuitive scientific elite.

Yet the myth of maternal intuition is actually a product of heteropatriarchal family systems that entrust mothers with primary authority over their children. The myth stems from the overarching belief that mothers are innately suited to handle the majority of childcare—a social construct that upholds the current gendered division of labor. The idea that mothers have a preternatural understanding of their children legitimizes this notion, upholding the expectation that women should bear the majority of the child-rearing burden as they “naturally” understand their children better than traditional science.

Mothers, who make approximately 80 percent of health care decisions for their children, are forced to shoulder a crushing burden. When their children fall ill, they are disproportionately likely to be their primary caregivers. Within this patriarchal framework—bolstered by the myth of maternal intuition—mothers are isolated within the home and forced to make sacrifices in silence, increasing their anxiety and making them more vulnerable to misinformation. This devastating status quo has long-term health implications for both mothers and their children, as well as our overall public health.

An article in The New York Times describes the way that the proliferation of fearmongering about chemicals by MAHA proponents has infected day-to-day parenting discourse. Convinced of the dangers of omnipresent toxic chemicals, mothers are guilt-tripped into purchasing more expensive “organic” goods and are sold numerous products to purify their water, detox their livers, and boost their immune system’s ability to fight toxins. Mothers in both conservative and liberal circles described a

sudden push within their communities toward drinking raw milk, shirking traditional childhood vaccine schedules, and adopting hypervigilance against microplastics, ultra-processed foods, and seed oils. The lifestyle of a perfect MAHA mom is unsustainable and unaffordable for most families, yet mothers are told that if they fail to guard their children from toxic chemicals, they are essentially poisoning them and dooming them to a life of chronic disease and mental illness.

In addition to creating unnecessary anxiety based on faulty evidence, the MAHA ideology advocates for explicitly dangerous decisions. Overriding scientific consensus, the CDC website now claims that “studies have not ruled out the possibility that infant vaccines cause autism,” parroting the anti-vaccine rhetoric that has led to the resurgence of many nearly eliminated diseases and caused preventable deaths and hospitalizations. In 2000, measles was declared eliminated from the United States. From 1997 to 2013, no more than 220 cases of measles were reported in any given year. So far, in 2025, more than 1,700 cases of measles have been reported, 92 percent of which have been in unvaccinated individuals or those with unknown vaccination status. So far, in 2025, three people have died from measles, more than in the past 25 years. The products that MAHA encourages people to consume can also be dangerous; raw milk, hawked by MAHA proponents, can carry harmful germs such as Salmonella and Listeria, which can, in extreme cases, lead to death.

Dismantling the influence of the MAHA conspiracy on motherhood and parenting requires more than just debunking, however. We must deconstruct the myth of maternal intuition and demand change to the current gendered division of labor. We must also recognize the legitimate, evidence-based threats to public health posed by climate change, corporate capture, and gross wealth disparities. Only then can we truly make America healthy.

Space law must evolve to recognize the sovereignty of future orbiting city-stations

by Asher Patel ’28, an International and Public Affairs and Applied MathematicsEconomics concentrator and Staff Writer for BPR

Fast forward 500 years: Humans have founded research colonies on the Moon and Mars, scientists are working on how to land on Jupiter, and the dream of reaching Saturn is on the table. While this expansive vision of space progress is exciting, one needs to look no further than our dear planet Earth to realize that the modern international legal regime is not yet equipped to handle future space exploration. Since the rate and direction of space sector development remain uncertain, it is critical to examine policy holes in the current legal regime and develop preliminary solutions.

Instead of setting up camp on more distant celestial bodies, some theorists envision a future with city-sized orbiting bases that could remain in low Earth orbit, approximately 1,000 miles above the planet’s surface. Such city-sized bases, as depicted in popular media like the Interstellar movie, are often envisioned as donut-shaped vessels capable of accommodating all components of a modern economy and city, sustaining thousands of people. Further, while initial orbiting cities may require consistent resupply missions from Earth, any realistic plan ought to strive for long-run self-sufficiency.

Indeed, these stations would likely contain everything required to sustain a functioning society, including farmland, waste management systems, doctors, lawyers, schools, jails, hair salons, a monetary system, and the means to conduct any necessary repairs or routine maintenance. To sustain a population for generations, reproduction would have to be possible, a problem eased by the ship’s constant rotation, which would create artificial gravity, a critical condition for successful gestation and birth.

While achieving this self-sustaining reality is a problem for engineers and scientists, even if a city population were to live, reproduce, and die autonomously on an orbiting station, one critical question remains: Who should govern?

As defined by the United Nations’ 1967 Outer Space Treaty, any space object remains under the jurisdiction of the terrestrial state that launched it. In this document and subsequent UN space treaties, space is treated as a global commons, yet the physical structures built and launched into orbit are legally tethered to terrestrial authority. More recently, the International Space Station (ISS), operational since 2000, is managed under a jointownership framework, where each international partner has jurisdiction over the portion they developed—take Japan’s experiment module or the European Space Agency’s Columbus Research Laboratory, for example— and is entitled to utilization rights for the other sections of the station.

While the above system of state authority over domestically developed space assets works efficiently in the modern era, some key assumptions grounding this model break down in the context of a future self-sustaining city-orbiter. For one, the Outer Space Treaty was written at a time when space habitation was still speculative, and the ISS Intergovernmental Agreement governs a station with normal crew sizes of seven and usual mission durations of about six months. In addition, modern astronauts are selected, trained by, and eventually return to their home country, making them naturally deeply connected to Earth’s geopolitical order. These assumptions quickly fail when considering a self-sustaining station on which thousands of passengers would be born and would die, having lived their entire lifetime there. Thus, instead of the modern system of terrestrial government control, if a self-sustaining orbiting city station is achieved, the people of that station should be independently sovereign and not tied to the international governing structure.

While calling for a new sovereign people seems radical on the surface, the rationale for this view is predicated on three intuitive assumptions: Enforcement from a terrestrial body would be nearly impossible; the culture and people of the citystation would be unrecognizable compared to those on Earth; and efficient decision-making would be necessary to keep the station alive. Following the logic of these assumptions, the natural conclusion is that it is most practical for people who can survive the absence of terrestrial help to govern themselves accordingly.

First, given a self-sustaining orbiting city, consistent trade with Earth or any other form of contact (except mutually beneficial collision prevention) would be purely elective for the orbiting city. It is also unlikely that station inhabitants would have Earth-tied assets after multiple generations on the station. Thus, absent the option to use missile technology to attack the orbiting city directly, terrestrial states or organizations would have limited leverage to sway in-orbit decision-making toward a policy the station deemed unfavorable. Even the countries that helped build the station will have to accept that any such arrangements made during the station’s development are effectively void after multiple generations.

Arguably more important than the coercive power that terrestrial states might attempt to yield is the willingness of station residents to be politically ruled by these states. After generations, normal genetic variation combined with lifestyle differences will yield a genetically unique population in the closed-system station. Moreover, increased exposure to radiation will lead to additional divergence from terrestrial humans. As seen from NASA’s comparison of astronaut Scott Kelly to his on-Earth twin brother after one year on the ISS, differences in gene expression, the gut microbiome, protein pathways, and more arise after only a short time in space.

“While achieving this self-sustaining reality is a problem for engineers and scientists, even if

a city population were to live, reproduce, and die autonomously on an orbiting station, one critical question remains: Who should govern?”

“If a self-sustaining orbiting city station is achieved, the people of that station should be independently sovereign and not tied to the international governing structure.”

In addition to biological changes, after living and reproducing in a unique environment with different challenges, living conditions, and hierarchies, the station’s population will likely develop a distinct culture. As time progresses, the difference between the composition and customs of the station’s first inhabitants and its current residents will only grow, making the perceived legitimacy of the terrestrial government ever more tenuous.

Finally, from a pragmatic view, the space domain is exceptionally unforgiving. In the event of an expected oxygen or food shortage, necessary repairs, or an increased risk of radiation, effective decision-making and on-station policy implementation will be crucial to sustaining the orbiting city. Furthermore, such problems are likely to recur, making them easier to solve as the population gains experience and divides into specialized expertise. Not only does this process not require oversight from a terrestrial body that knows less about the situation, but the inhabitants may also be practically worse off if they rely on slow communication for clearance in an emergency. Of course, things like ground-based monitoring and tracking data might be very useful in disaster mitigation. Still, this level of data sharing is consistent with how sovereign states share data today. As such, there is no clear pragmatic advantage to having terrestrial-based leadership.

Tying the three assumptions together, the argument for a sovereign orbiting city is satisfactory when considering its ability to assert its sovereignty, the will of its population, and the pragmatic utility of independence in decision-making. While this result is intuitive, its

significance should not be underestimated. Although the last space-focused UN treaty entered into force over 40 years ago in 1984, the space sector has continued to scale and progress exponentially, a trend fueled by ever-falling launch costs and $393 billion invested across over 2,000 space companies. Even if it is unclear whether sustained human habitation will be achieved within the next few hundred years, rapid development in the space sector is imminent. When a technology becomes feasible, we face rapid changes without much warning, which necessitates the creation of new policy ahead of time. For example, in 2019, there were only about 2,000 satellites in orbit, but by 2023, the number increased to over 9,000, sparking a US effort to reevaluate its space debris mitigation policy—a difficult task due to limited prior research.

Under the constant uncertainty of what the space sector could yield, it is paramount that our leaders consider space law edge cases and prepare modifiable policies for use when a breakthrough technology is reached. Even if an orbital habitat exists in fiction today, exploring its legal implications ensures that when science catches up to our imagination, our institutions will not be decades behind.

“After generations, normal genetic variation combined with lifestyle differences will yield a genetically unique population in the closed-system station.”

The 2015 film Sicario by French-Canadian director Denis Villeneuve features US strikes and troop deployments to combat Latin American “narcoterrorist” drug cartels across the Southern border. After FBI agents raid a cartel safe house and discover dozens of bodies murdered by the fictional “Sonora Cartel,” the American president designates a number of Mexican criminal cartels as foreign terrorist organizations (FTOs) and authorizes the US military to deploy lethal force against them. US troops enter Mexico, but their plan soon devolves into a vicious gunfight at a border crossing, and security cooperation between Mexico and the United States breaks down. Though the US government prevents the events from reaching the press, it nearly becomes an international diplomatic catastrophe.

Although Sicario is fictional, it draws many parallels to President Donald Trump’s current regime change and anti-cartel ambitions. Because of these similarities, Sicario offers a compelling idea of how US intervention in Venezuela, Mexico, or another nation may not go as Trump hopes.

In our current reality, powerful criminal syndicates in Mexico, Central America, Colombia, Venezuela, and the Caribbean engage in violent drug trafficking. Drugs sent to the United States cause tens of thousands of overdose deaths every year. Drug-trafficking groups like the Sinaloa Cartel and Jalisco New Generation Cartel (CJNG) are so powerful that they operate as a shadow state in many areas of Mexico, committing terrorist attacks and influencing politicians.

In February 2025, President Trump designated eight cartels as FTOs. Since then, he has unilaterally struck 22 alleged drug-smuggling vessels, killing at least 80 people. Claiming that Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro is the leader of a “narco-terrorist” network, Trump announced a $50 million bounty for his arrest and authorized CIA agents to operate inside Venezuela. Additionally, he has stationed 10,000 American troops and 10 F-35 fighter jets in Puerto Rico, and sent the USS Gerald R. Ford, the most expensive warship ever built, on its way to Venezuela.

Trump and his advisors, Secretary of State Marco Rubio and Secretary of War Pete Hegseth, maintain that the recent US moves against Maduro are purely to curb alleged drug trafficking by the Cartel de los Soles—a criminal terrorist organization embedded, according to Trump, within the Venezuelan military and political brass. However, Trump’s true motive is broadly understood to be regime change in Caracas. When asked by a reporter if he is bent on regime change, Trump said that “Maduro’s days are numbered.”

Maduro is not backing down from confrontation. He has already mobilized the Venezuelan air force and Bolivarian militia, mass conscripting 4.5 million people. In a post-Maduro Venezuela, it would be challenging for the US to ensure stability and prevent a similar politician from filling the power vacuum. Perhaps the pro-American, persecuted opposition leader María Corina Machado would take power, but the mechanisms for installing her in Caracas are not clear. Both Trump’s alleged mission of stopping drug trafficking and his likely goal of ousting Maduro are more easily said than done, and no long-term stability will be achieved without

by Nicholas Freund ’28, a History concentrator illustration by Bath Hernández ’26, an Illustration major at RISD and Art Director for BPR

“In a country whose most violent areas are also some of its poorest, decades of neglect and corruption have only made the problem worse—two factors that cannot be rooted out with rifles.”

an improvement in the material conditions of Venezuela’s citizens. As The Washington Post recently declared, “Maduro braces for a U.S. attack; Venezuelans worry more about dinner.” Both Trump and Rubio have also floated the idea of US drone strikes or troop deployments against Mexican cartels and the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC), a socialist paramilitary group now primarily engaged in drug trafficking, despite Mexico’s objections.

If Mexico’s recent history is any indication, criminal cartels are not easily defeated through force. In 2006, after a series of cartel terror attacks in Michoacán, former President Felipe Calderón declared a war against drug trafficking in Mexico. Since then, almost 200,000 people have been killed across the country. This high cost has done little to curb drug trafficking. In fact, Mexican cartels are more profitable and powerful than ever, soliciting favors from the highest levels of government, boasting military-grade weapons, and bringing in $40 billion annually from their vast illicit trade networks that include fentanyl sourced from China. In a country whose most violent areas are also some of its poorest, decades of neglect and corruption have only made the problem worse—two factors that cannot be rooted out with rifles.

Apart from the fact that an armed intervention in Mexico is unlikely to eradicate drug trafficking, any military action would also bring suffering for the most vulnerable populations. In addition to the combatant lives lost, anti-narcotic operations against the FARC in Colombia, the cartels of Michoacán in Mexico, and President Nayib Bukele’s gang crackdown in El Salvador have all led to the collateral detainment and death of innocent civilians. Villeneuve illustrates this human cost of anti-narcotic operations viscerally on screen in Sicario, where action scenes in war-torn Ciudad Juárez are interspersed with scenes of children playing soccer and families going about their days mere yards from hailstorms of bullets.

While Trump believes that solving the US drug crisis means looking abroad, many state governments across the Union are also working to prevent drug overdose deaths in their jurisdictions, showing that domestic drug reform must also be part of the equation. Trump’s fight against the cartels may beat back some of their influence, but the truth is that Americans will continue to die from drug overdoses regardless of who their dealer is. This is perhaps Sicario’s most important message: A truly effective war on drugs is far more difficult than dropping bombs.

Diella, Albania’s AI government official, will not fix a decades-long corruption battle

by Ben Hader ’ 28, an International and Public Affairs and History concentrator and Staff Writer for BPR

Albania’s newest cabinet member is pregnant…with 83 babies. But do not worry, she is not human. Meet Diella, Albania’s “AI minister.”

Diella was “born” on January 19, 2025, with the job of managing Albania’s ‘e-Albania’ platform, which digitally provides over 1,200 public services to Albanian citizens. From completing school registration to filling out job applications, Diella can help. Since her inception, Diella has stamped 36,000 documents, increasing the accessibility of bureaucratic services.

On September 11, 2025, Prime Minister Edi Rama formally appointed Diella to a new role—AI minister. Her promotion makes Diella responsible for Albania’s billion-dollar public procurement process, in which Albania’s government purchases goods and services from the private sector. Public procurement is a hotbed for governmental corruption in Albania: the country scored a 42 out of 100 on the 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index, which scores countries on their public sector corruption. By evaluating each tender, assessing its merit, and deciding whether or not to award a contract to the private firm seeking the tender, Diella will supposedly prevent public procurement corruption, an issue that has plagued Rama’s government.

For Rama, Diella’s “incorruptibility” is a key mechanism to joining the EU by 2030—a major campaign promise of Rama’s that has been impeded by Albania’s decades-long struggle with corruption. In recent years, Albania has grown closer to accession into the EU, only needing to meet one final cluster of policy criteria—fundamentals—which includes public procurement forms.

The use of Diella as an anticorruption measure by Rama has been marketed as a groundbreaking innovation. After all, Diella is the first AI system to serve in any country’s cabinet. However, while Diella’s professed purpose is to win EU favor by eliminating corruption and advancing technology’s role in government, her appointment acts more as a propaganda tool for Rama’s administration. As Diella’s parliamentary presence proliferates with the announcement of her babies, Rama risks creating an unchecked political entity that can sway government policies. Diella’s lack of oversight, dependence on American technology firms, and undemocratic ties to Rama’s Socialist Party instead threaten to compromise Albania’s path to EU accession and jeopardize the country’s long-term democratic development.

Diella, meaning “sun” or “sunshine” in Albanian, is depicted as a young woman in traditional Albanian wear— propagandizing the party’s desire to “eliminate corruption” as a national duty. Rama embeds Albanian nationalism within Diella’s visual display to signal a unified, traditional Albanian identity that predates globalization—all while paradoxically achieving this through a novel usage of artificial intelligence.

Diella is presented as an accountabilityproviding force for Albania’s government but no political mechanisms hold her accountable. She cannot be impeached; she is not real. Therefore, what happens if she makes a harmful decision? AI models, too, feature bias based on their decision-making data, and Diella’s data is undisclosed. Diella’s model is designed by Albania’s National Agency for Information Society (AKSHI), which reports directly to Rama. Biased training data and other design choices, as well as the lack of transparency, shape Diella into a political device that will likely decrease accountability for Rama and his Socialist Party allies rather than providing a source of neutrality as an independent actor. With AI in charge, any blame for corruption in public procurement can be shifted away from Rama’s administration and onto Diella.

While Diella brings data privacy concerns and obscures political neutrality, what is known is that her model is built using foreign technology—another challenge to holding Diella accountable. Diella runs on Microsoft Azure with OpenAI models, both of which are US platforms. While AKSHI provides Albanian government data, Diella’s decisionmaking is determined by US technology, rendering her dependent on the United States to appropriately protect sensitive information. The Albanian government cannot monitor the decisions of these US tech firms in the way that it can monitor Albanian companies, since US technology companies remain largely outside the purview of the Albanian government.

Although Diella has been championed as an effective method of decreasing corruption for EU accession, she does so by shirking the EU’s own AI guidelines. The EU’s 2024 AI Act outlines AI-related regulations that Albania currently does not follow, including the requirement to provide a summary of what content is being used to train Diella. Because Diella provides access to critical infrastructure, she is considered a “high-risk” system and must receive oversight by an independent “national competent authority” that Albania has yet to instate.

Furthermore, Diella’s newly announced “babies” are a domestic threat to effective democracy because they privilege Rama’s Socialist Party. Diella’s 83 “children” will serve as assistants, recording legislative sessions and offering policy suggestions. But only the Socialist Party’s 83 parliamentarians can access them, marking a clear partisan divide in which government officials can benefit from Diella’s assistance. As Diella becomes a minister—and thus increasingly important in the government— gatekeeping access to her becomes democratically problematic. If Rama’s technology-forward vision excludes many of the politicians that Albanians elected, it dangerously skews the country’s political system in favor of the Socialist Party.

“As Diella’s

parliamentary presence proliferates with the announcement of her babies, Rama risks creating an unchecked political entity that can sway government policies.”