Rituals come in many forms—religious ceremonies, national holidays, family celebrations, and daily habits. Rituals unite people, providing a powerful form of shared experience They mold our identity, signifying our membership in a collective. But rituals can also be weaponized to achieve political objectives or perpetuate injustice. Rituals are everchanging—and new rituals can introduce new challenges. In this special feature, we explore how rituals shape politics in ways both small and large.

In Nepal, Chhaupadi, a type of menstrual exile, is a life-threat ening reality for countless girls and women. Attempts to curb the practice by activist groups, international organizations, and the federal government have largely fallen flat—ineffective especially in Nepal’s rural villages. In “Period Power,” Remi Takahashi con tends that effective campaigns against Chhaupadi must consider it as not only a human rights violation, but a ritual—reckoning with its cultural place and significance.

Russia has weaponized the memory of World War II to jus tify silencing dissent and invading Ukraine. In “Don’t Rain on My Parade,” Alice Miller explores how Russia has transformed the collective memory of its fight against facism in WWII into a powerful tool to achieve the government’s political objectives. Through remembrance rituals, Putin links the fascist crimes committed during WWII with the activities of modern dissidents and pro-Western governments.

Standing for the Pledge of Allegiance is a daily ritual for millions of K-12 students in the United States. Does this ritual foster patriotism? Sabine Gladis argues in “One Nation, Under Who?” that reciting The Pledge generates a superficial, rigid form of mandated patriotism. She contends that authentic civic engagement—embodied through the rituals of activism, protest, and community service—offers a better benchmark for patriotism among young Americans. By embracing civic engagement, students can redefine patriotism on their own terms.

The internet has transformed the rituals of dating for Gen Z. In “@pavlov liked your story,” Ashton Higgins discusses the way courtship has been redefined into a series of online rituals: swiping right, liking a story, and commenting on posts. These abstract

the smallest of interactions, emphasizing short-term gratification rather than long-term commitment. According to Higgins, these new rituals exacerbate the youth mental health crisis and make it harder to find love.

Saree runs have proliferated in South Asia—enabling women, who have historically faced cultural barriers to exercise—to live an active lifestyle. However, by centering a garment that has a complex colonial history, and engaging only minimally with a broader vision of women’s rights, their potential has been limited. In “Saree Strides,” Zern Hee Chua explores this new ritual, probing its complex role in advancing women’s empowerment.

As you read through this issue, we hope you reflect on the rituals you participate in. How do they shape your life, your beliefs, and your politics? How can we determine which rituals are worth preserving—and which ones need to be revised? Amina

EDITORS IN CHIEF

Amina Fayaz

Elliot Smith

CHIEFS OF STAFF

Grace Leclerc

Jordan Lac

CHIEF OPERATING OFFICERS

John Lee

Manav Musunuru

MANAGING EDITORS

Ashton Higgins

Mitsuki Jiang

Sofie Zeruto

CHIEF COPY EDITORS

Renee Kuo

Tiffany Eddy

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Ariella Reynolds

Benjamin Stern

DATA DIRECTORS

Nikhil Das

Tiziano Pardo

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Bath Hernández

Fah Prayottavekit

Natalie Ho

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTOR

Solomon (Solly)

Goloboff-Schragger

WEB DIRECTOR

Armaan Patankar

DIVERSITY OFFICER

Michael Shui

Alexandros Diplas

Allison Meakem

Gabriel Merkel

Hannah Severyns

Mathilda Silbiger

Tiffany Pai

Zander Blitzer

DIVERSITY OFFICER

Michael Shui

DIVERSITY ASSOCIATE

Jiayi Wu

INTERVIEWS DIRECTORS

Ariella Reynolds

Benjamin Stern

DEPUTY INTERVIEWS

DIRECTORS

Ciara Leonard

Eiffel Sunga

Matthew Kotcher

Charlotte Peterson

INTERVIEWS ASSOCIATES

Aleksandra Pakhomova

Amish Jindal

Anita Sosa

Aurna Mukherjee

Charles Lebwohl

Christina Li

Gabriella Miranda

Jack DiPrimio

Maria Mooraj

Matteo Papadopoulos

Michael Lau

Michele Togbe

Nava Litt

Raghav Ramgopal

Rishabh Rao

Riyana Srihari

Rutva Brahmbhatt

Sarik Gupta

Sofia Segarra Wilber Anteroladata

DATA DIRECTORS

Nikhil Das Tiziano Pardo

DATA ASSOCIATES

Aavin Mangalmurti

Amy Qiao

Anna Wong

Brandon Yu

Breanna Villarreal

Fanny Vavrovsky

Ishaan Jain

Jeffrey Gao

Joshua Reed

Reina Jo

Romilly Thomson

Wesley Horn

Zoe Weissman

DATA DESIGNERS

Carys Lam Yeonjai Song

WEB DIRECTOR

Armaan Patankar

WEB DEVELOPERS

Hao Wen

Jaideep Naik

Joanne Ding

Nitin Sudarsanam

Shafiul Haque

WEB DESIGNERS

Casey Gao

Hyelim Lee

Zairan Liu

PUZZLE DIRECTOR

Matthew DaSilva

PUZZLE DESIGNERS

Ana Vissicchio

Lucy Bryce

Marissa Scott

CHIEF COPY

EDITORS

Renee Kuo

Tiffany Eddy

MANAGING COPY

EDITORS

Nicholas Clampitt

Vivian Chute

COPY EDITORS

Aditya Krishnan

Annika Melwani

Charlotte Peterson

Christina Li

Damiana Harper

Daniel Shin

Eva Dillon

Isabela Perez-Sanchez

Jason Hwang

Kaylee Gilbert

Leah Freedman

Lillian Castrillon

Michaela Hanson

Natalie Tse

Nate Barkow

Rachel Loeb

Rachel Sang

Ryan Choo

Shant Ispendjian

Shiela Phoha

Tanvi Mittal

Vanya Shah

MULTIMEDIA DIRECTOR

Solomon (Solly)

Goloboff-Schragger

MULTIMEDIA PRODUCERS

Audrey Gmerek

Becky Montes

Chompoonek (Chicha)

Nimitpornsuko

Christina Charie

Clara Baisinger-Rosen

Danielle Deculus

Ella Podurigiel

Ellie Wu

Erin Ozyurek

Josué Morales

Leyad Zavriyev

Lucas Da Silva

Lucy Previn

Lynn Nguyen

Maison Teixeira

Miranda Mason

Nava Litt

Oona O’Brien

Romi Bhatia

Sophie Mueller

Thomas Foley

Xavier Colon

Zarah Hillman

PODCAST DIRECTOR

Caroline Cordts

BUSINESS DIRECTORS

John Lee

Manav Musunuru

BUSINESS ASSOCIATES

Arjun Puri

Becky Montes

Elina Coutlakis-Hixson

Jack DiPrimio

Lizzie Duong

Mariana Copeland Celaya

Neve O’Neil

Remi Takahashi

MANAGING EDITORS

Ashton Higgins

Mitsuki Jiang

Sofie Zeruto

SENIOR EDITORS

Aman Vora

Brynn Manke

Julianna Muzyczyszyn

Keyes Sumner

Steve Robinson

Tess Naquet-Radiguet

EDITORS

Allan Wang

Annabel Williams

Ava Rahman

Chris Donnelly

Daphne Dluzniewski

Emily Feil

Fabiana Conway

Faith Li

Gus LaFave

Isabella Xu

Joshua Stearns

Kenneth Kalu

Madeleine Connery

Mateo Navarro

Meruka Vyas

Nicolaas Schmid

Rohan Leveille

Sara Amir

HIGH SCHOOL PROGRAM LEAD

Brynn Manke Tess Naquet-Radiguet

CREATIVE DIRECTORS

Bath Hernández

Natalie Ho

Fah Prayottavekit

DESIGN DIRECTOR

Jiabao Wu

EDITORIAL DESIGNERS

Anna Wang

Dongha Kwak

Jay Moon

Marie You

Sheeon Chang

Tiffany Tsan

PUBLIC RELATIONS

DESIGNERS

Jordan Kinley

Kyuwon Park

ART DIRECTORS

Angela Xu

Burcu Koleli

Larisa Kachko

Leslie Mateus

COVER ARTIST

Sarah Naidich

STAFF WRITERS

Aaditya Das Narayan

Alexia Lara

Alina Calix-Martinez

Andrea Fuentes

Arjun Puri

Asher Patel

Audrey Gmerek

Ben Hader

Charlie Getman

Chiupong Huang

Christina Charie

David Macario

Emily Pan

Emily Schreiber

Emma Phan

Fanny Vavrovsky

George Weiler

Gui Sequeira

Isabella Collins

Kayla Morrison

Kimaya Balendra

Lauren Kozmor

Lev Kotler-Berkowitz

Matthew MacKay

Mia Reyn

Michaela Hanson

Nainika Sompallie

Nate Barkow

Napintakorn (Pin) Kasemsri

Natalia Baños Delgado

Remi Takahashi

Riya Singh

Sabine Cladis

Siyuan (Michael) Shui

Shane Vandevelde

Shant Ispendjian

Sonya Rashkovan

Will Thomas

Samdol Lhamo Sichoe

Zern Hee Chua

ILLUSTRATORS

Airien Ludin

Amelia Jeoung

Angelina So

Anneke Beth

Awele Chukwumah

Christina Xu

Cora Zeng

Elizabeth Chew

Ellie Lin

Emily Chao

Emily McShane

Haley Maka

Jiwon Lim

Kexin Huang

Kyuwon Park

Lily Engblom-Stryker

LuJia Liao

Lydia Smithey

Mia Cheng

Mot Tuman

Oli Bartsch

Orla Maxwell

Paul Li

Ranran Ma

Rokia Whitehouse

Shay Salmon

Sofia Schreiber

Wanxin Li

York Mgbejume

Free staters are attempting to take over New Hampshire

by Joshua Stearns ’28

, a Political Science concentrator and Editor for BPR illustrations by Haley Maka ’26, an Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

Croydon, New Hampshire—a town of about 800 nestled amongst rolling hills and pristine ponds, where an 18th-century one-room schoolhouse still operates—lies just miles from American playwright Thornton Wilder’s fictional Grover’s Corners. Croydon’s idyllic atmosphere was shattered in 2022, however, when a group of ultra-libertarians, members of the Free State Project (FSP), hijacked the annual town meeting and voted to halve the town’s school budget, a cut which would have effectively abolished in-person education for Croydon students. In an amazing rally of unity, the townspeople fought back. After going on what one school board member described as a “witch-hunt” for Free Staters and calling an unprecedented second annual town meeting, the townspeople overwhelmingly voted to restore the school budget.

Imagine if your neighbors moved to your state with a hidden agenda: to destroy it from the bottom up. It may sound like fiction, but this has been unfolding across New Hampshire for over a decade. Despite less open organizing and increased public awareness of the FSP since the events in Croydon, the project’s threat has grown to unprecedented heights. Now, operating silently through the State Legislature, the movement’s agenda is hidden in complex legislation, allowing its vision to inch ever closer to realization. Alarmingly, few seem to notice.

“Imagine if your neighbors moved to your state with a hidden agenda: to destroy it from the bottom up. It may sound like fiction, but this has been unfolding across New Hampshire for over a decade.”

The FSP was founded in 2001 by Jason Sorens, a doctoral student at Yale who theorized that if a group as small as even 20,000 people dedicated itself to infiltrating and dismantling state government and moved to a low-population state, a paradise of anarcho-capitalism could be born in America. In 2003, New Hampshire, where Independents outnumber both major political parties, was selected by several thousand initial Free Staters as the ideal state because of its size and small-government culture (“Live Free or Die” is the state’s motto). After the selection, many Granite Staters, including then-Governor Craig Benson, welcomed them. By 2023, about 10,000 Free Staters had followed through and migrated to New Hampshire, though more than 20,000 have signed a pledge to move. Free Staters, importantly, do not want to merely pass a slew of budget cuts: Their goal is to extremify the state’s freedom-loving culture, eliminate all government, and establish a “libertopia” where all property is privatized.

You might wonder: How dangerous can a group of just 10,000 ideologues be to a state of 1.4 million? The answer: extremely. The initial plan seemed to be to establish “colonies” of Free Staters in small communities of several hundred, like Croydon, to seize control of local governments. However, after the events in Croydon and previous missteps around the state (for example, Grafton, New Hampshire, was taken over by black bears in large part thanks to the Free Staters’ belief that nobody could stop them from feeding boxes of donuts to local bears), many Granite Staters became wary of the movement. Numerous Free Staters, however, have managed to remain undetected, even in the State House.

A common joke about New Hampshire’s state legislature—the third largest in the Anglophone world—is that whoever wants to

be a legislator can be. This also means that it is ripe for Free Stater infiltration. Since Croydon, the FSP has shifted from a simple, idealistic migratory movement to a state-by-state funnel for national donors to platform libertarian values. While the share of representatives openly identifying as Free Staters when last counted in 2018 was just 17 out of 400, the effort to create a Free Stater-dominated legislature has not waned. In 2024, big oil political action committees like Make Liberty Win and Americans for Prosperity donated over one million dollars to fund at least 130 FSP-aligned New Hampshire House candidates.

Alongside the growth of the FSP-affiliated bloc, the Free State agenda has increasingly appeared in legislation. In the 2025 legislative session, the House-approved budget (later revised in conference with the state Senate) included provisions to slash funding for most state departments, services, and councils. Republican House Majority Leader Jason Osborne (R-NH), a Free Stater, was behind perhaps the most dangerous provision of the House Budget, which would have imposed a budget cap on school districts. In many cases, legislation championed by Free Staters is not even written by Free Staters but by the American Legislative Exchange Council, a libertarian think tank with financial ties to Project 2025.

Outside of the legislature, Free Staters’ focus now lies on repealing local zoning laws that slow their migration. Sorens authored a 2021 study of land-use regulations, in which he explains the need to amend local zoning ordinances in New Hampshire to increase the availability of affordable housing. He specifically advocates for zoning changes in the Monadnock region to allow a large tract of land to be filled with mobile homes, explaining that the development is needed because it would cause a “substantial

“The FSP is a cancer on New Hampshire’s ideals of personal liberty, as it works insidiously to bend Granite Staters’ lives and freedoms to its will.”

growth in the tax base” to fund local public schools and reverse falling enrollment.

However, if Sorens truly did care about affordable housing for the sake of Granite Staters, he would not argue that it would reverse falling enrollment in local schools while simultaneously orchestrating a movement that works to defund public education. Sorens’s aim is for affordable housing projects, like the one in the Monadnock region, to be filled by Free Staters, many of whom are then encouraged to run for local office.

Free Staters’ hypocrisy does not end there. Sorens defended President Donald Trump’s mass deportations in a recent article, arguing that it is better to over-deport immigrants because some are “terrorist sympathizers” eager to destroy our country than to not deport enough and fail to capture them all. He writes that “terrorist sympathizers… will vote away our freedoms when they get a chance” and that voting away others’ freedoms “is a form of aggression;” thus, “voting is not like free speech—it necessarily affects the rights and interests of others.” Therefore, “you have a duty not to vote if your vote would be incompetent or unjust.”

Based on Sorens’s own logic, by moving to a state with the intent of eliminating public schooling for other people’s children and changing zoning laws to move in more members of their dangerous ideological movement, Free Staters are waging a war of “aggression” on Granite Staters. The Free Staters who carry out this malevolent mission even describe themselves as part of a “mass migration.” On their website, they also offer advice on navigating the process of immigrating to New Hampshire from overseas. Unlike most migrants, though, Free Staters move solely based on their desire to radically change the political nature of their new home. The Free Staters, of course, justify their actions by ignoring this inconsistency. Anyone who criticizes them, they say, is discriminating against them, but they also have a track record of silencing critics with violent threats.

Granite Staters take the issue of personal liberty seriously: New Hampshire is the only state where wearing a seatbelt is not legally mandated. The FSP is a cancer on New Hampshire’s ideals of personal liberty, as it works insidiously to bend Granite Staters’ lives and freedoms to its will. Importantly, Free Staters seem to recognize that what they are doing is deeply unpopular: They operate covertly, waiting for the perfect moment to strike (like an underattended annual town meeting) and implement plans with disastrous consequences. Most Granite Staters seem not to realize the immediacy of the sustained threat posed by the FSP. After Croydon, the gloves are off in the fight for liberty in New Hampshire. Granite Staters should fight like hell to preserve their freedoms.

by Charlie Getman ’28, an International and Public Affairs concentrator and Staff Writer for BPR

by Carys Lam ’29, an Architecture major at RISD and Data Designer for BPR

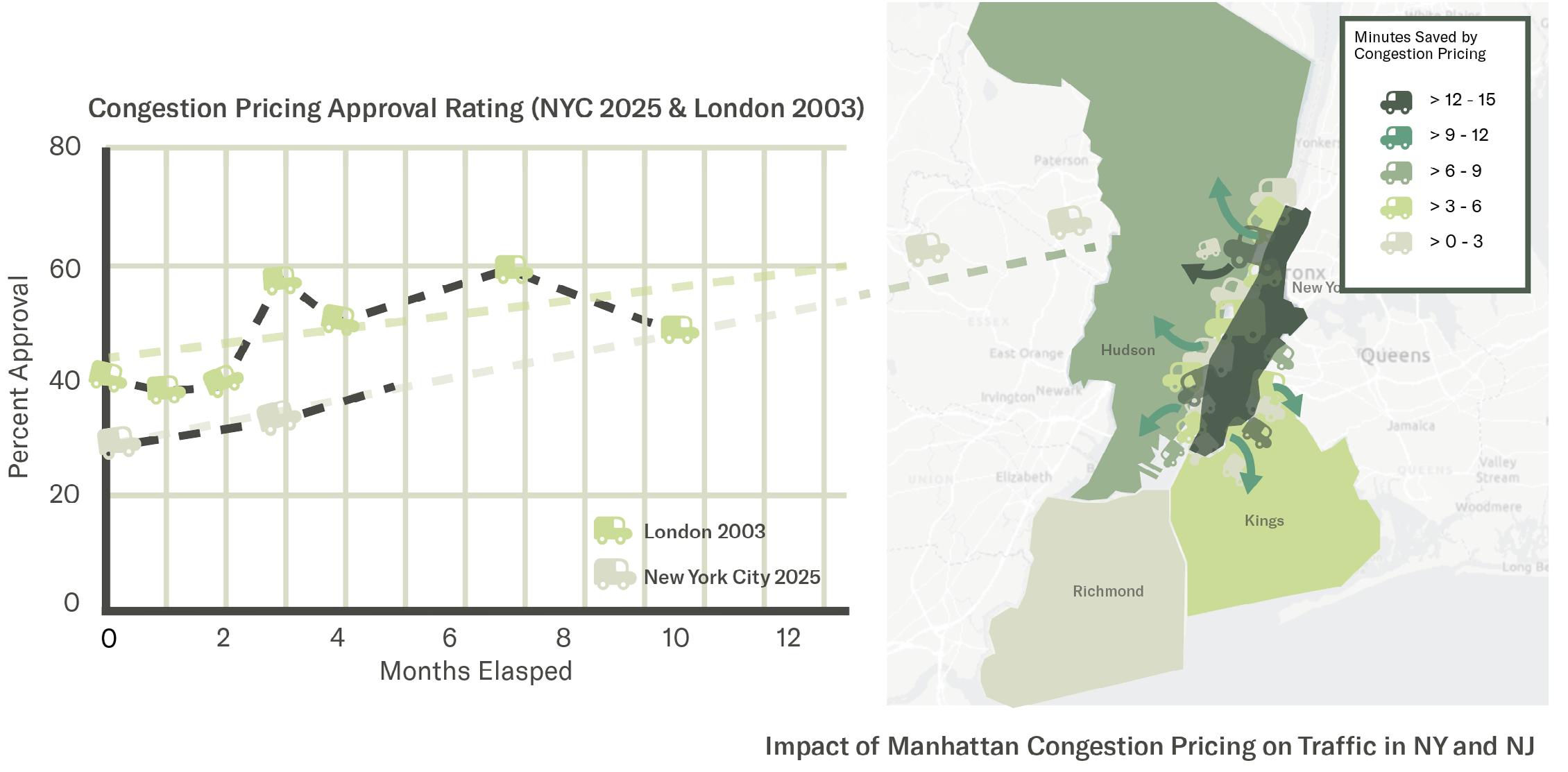

When New York City’s congestion pricing plan launched on January 5, 2025, the sky did not fall—but traffic did. After months of political struggle and years of public debate, the policy delivered what its advocates promised: Vehicle entries south of 60th Street have decreased by 11 percent, delays by 25 percent, and revenue generated for the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA) from the program is set to reach the predicted $500 million this year. Despite this success, just nine months later, 41 percent of New Yorkers think the policy should not remain. In contrast, when London implemented its own congestion pricing plan in 2003, public approval rose to 50–60 percent within months; New York’s rollout seems to be delivering London-style results but not London-style acceptance. In a political culture where trust in government is at an all-time low, congestion pricing will continue to be viewed as an outrageous fine unless it is paired with tangible, near-term improvements in infrastructure and an administrative structure New Yorkers trust.

Here is how congestion pricing works: Most vehicles entering Manhattan south of 60th Street now pay a nine-dollar toll once per day—a policy meant to cut traffic, noise, and emissions while funding transit and infrastructure improvements. But suburban commuters, especially those traveling across state lines, have fueled a major political pushback. New Jersey sued to delay implementation, and the Trump administration even sought to revoke federal approval before the program began.

This policy, while novel for the United States, is not unique on the global stage—cities like London, Stockholm, Singapore, and Milan have

upheld similar programs for decades. With such a wealth of historical precedents, proponents of the New York model should look to their international counterparts for inspiration. Understanding how London moved from skepticism to normalization offers New York a roadmap for turning technical success into political acceptance.

In 2003, then-Mayor Ken Livingstone spearheaded London’s congestion pricing program, staking his political future on a controversial attempt to reduce London’s recordhigh pollution and traffic. Despite low popularity, on February 17, 2003, London began the fivepound (£) charge. At its inception, only 40 percent of Londoners supported the program, and Livingstone’s policy brainchild seemed more like political suicide than infrastructure ingenuity. Within a year, central London saw a 15 percent reduction in traffic and a 30 percent reduction in travel delays. Following its promising rollout, public approval rose 10–20 percentage points, and the program was deemed a success. New York’s story reads similarly—until the ending.

“New York’s congestion pricing implementation was hobbled from the start by fractured governance.”

New York’s congestion pricing implementation was hobbled from the start by fractured governance. The program was authorized by the state legislature in 2019, with a new state Traffic Mobility Review Board setting the tolls and exemptions. The MTA, a public benefit corporation of New York State, built the system itself—gantries, cameras, billing—subject to the board’s sign-off. Because federal funds had been used on some of the roads, the plan also required the US Department of Transportation’s approval before the governor gave the final sign-off. In other words, nearly every level of government touched the plan, except for the municipal government and the New Yorkers who ended up footing the bill. This confusing and stalled rollout gave New Yorkers ample reason to doubt the program’s sincerity.

Although London’s congestion pricing was unpopular at the outset, its implementation felt uniquely honest. The program had a singular champion in Livingstone, who had staked his political career on the risky policy. Notably absent was the federalist nightmare that permeated the New York case. Practically all of the details were handled by Transport for London (TfL), and both Livingstone and TfL conducted an extensive 18-month public consultation process before launching the program. It was undoubtedly easier for Londoners to trust the program when they could point to a singular figure leading the charge, while being comforted by a consultation process that provided the representation that many New Yorkers feel they were not given. While New York also went through the motions of public consultation, it was so poorly received that the state was sued for excluding outer-borough

residents from the conversation. New York’s arguably anti-democratic rollout shows how its approval gap with London stems from a lack of trust.

Trust came not just from how London governed the program but also from how it spent the money. In London, Livingstone ensured that hundreds of new buses hit the streets before the charge even began. Routes were extended, headways shortened, and the improvements were unmistakable: pay the fee, ride a better bus. In New York, every dollar of congestion pricing revenue is legally earmarked to fill a $15 billion hole in the MTA’s capital plan. The resulting funds would finance projects such as subway station accessibility or new electric buses. However, the problem is timing: These projects will take years, leaving New Yorkers feeling like their tolls vanish into budget sheets rather than fund improvements. London’s decision to frontload direct upgrades helped stabilize public support, while New York’s choice to funnel revenue into a capital plan has left the toll louder than the improvements it funds.

“These projects will take years, leaving New Yorkers feeling like their tolls vanish into budget sheets rather than fund improvements.”

New York cannot rewrite its governance structure overnight, nor can it untangle toll revenue from the MTA’s capital plan. It can, however, still make congestion pricing feel less like a bill and more like a bargain. This process needs to center the New York riders who were left out of congestion pricing’s rollout, restoring public confidence. Creating an independent oversight body that includes representation from both individual riders and borough leadership would give the program visible stewards and a localized focus. This oversight body would rebuild trust through annual public hearings that focus on riders from all five boroughs— something the city’s earlier public consultation process failed to do. Public trust could be strengthened by implementing participatory budgeting—something New York already utilizes to allow communities to direct how some of their district’s capital discretionary funds are used. Participatory budgeting would leverage localized expertise to turn an abstract toll into visible neighborhood improvements, countering the fear that state bureaucrats are wasting the revenue generated by congestion pricing. If trust is the price of progress, participatory budgeting is how New York begins to earn it.

Initiating these changes would not erase the toll’s unpopularity, but it would give New Yorkers proof that the toll is both accountable and worth the cost. London’s lesson is clear: Technical success is meaningless without political trust. To endure, congestion pricing must make New Yorkers feel like their tolls buy something real— because it is trust, not traffic, that will decide its future.

“Although London’s congestion pricing was unpopular at the outset, its implementation felt uniquely honest.”

Steven Brown has served as the Executive Director of the Rhode Island American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) for more than three decades. In today’s political climate—one in which new legal challenges constantly emerge—Brown works to ensure that the promises of civil rights are not just theoretical ideals but also lived realities for the people of Rhode Island.

Ciara Leonard: Now that there is a new understanding of the Civil Rights Act being pushed and enforced under the new administration, when deciding which cases to defend, will the ACLU’s priorities shift moving forward?

Steven Brown: I don’t think it’s so much a shifting of priorities as much as it is focusing on issues now arising under the Trump administration that we haven’t had to deal with before. An example is a lawsuit that we filed against the National Endowment for the Arts (NEA). The Trump administration issued an executive order requiring all federal agencies to not fund any projects that “promote gender ideology.” We then heard from local arts groups

who wanted to apply for grants but were afraid what they were applying for might run afoul of this executive order. In order to even apply for a grant, the artists had to certify they did not “promote gender ideology,” so we filed a lawsuit on their behalf. The NEA quickly got rid of the certification requirement but are still not saying that they won’t judge applications on this gender ideology scale. There’s really no limit right now on how many civil liberties battles we are going to face from the Trump administration, but the issues themselves are not new. It’s just applying basic civil liberties principles to these attempts to roll back civil rights.

CL: With so many organizations now falling under scrutiny, there will be a lot more waiting on decisions to be made. What are the consequences of being in this limbo state?

SB: A goal of many of Trump’s executive orders is to confuse people. That’s true of diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) orders, eliminating funding for projects involving DEI without ever really explaining what is covered. We also have this confusion in terms of immigrants—not just undocumented immigrants, but seeing actions taken against people who are lawfully in this country. It’s, to some extent, a scare tactic and an intimidation attempt. And, unfortunately, it’s working to a large extent. When you don’t know what the rules are or even whether the administration itself may break the rules, it puts people in a lot of fear and uncertainty. That’s one of the most troubling aspects of what’s going on right now.

CL: Since Trump has taken office, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Department of Homeland Security agents have been active across Rhode Island. Could you give an overview of the current state of immigration protections in Rhode Island?

SB: Since the first Trump administration, the ACLU has encouraged localities to adopt immigrant protection ordinances. One of the provisions in the model ordinance would prevent local police departments from entering into agreements, known as 287(g) agreements, that specifically authorize collaboration with ICE on immigration raids.

There are also a number of bills pending in the state legislature designed to provide some protections to immigrants. One of the outstanding requests comes from the Immigrant Coalition of Rhode Island, who sent a letter to the chief justice of the Rhode Island Supreme Court asking him to prevent ICE agents from arresting people at courthouses. This has an incredibly chilling effect on immigrants wanting to make use of the judicial system, whether they’re parties to a lawsuit or witnesses. There’s a very real sense of danger in making use of the court system if people think ICE agents may be prowling the halls looking for individuals to pick up.

“When you don’t know what the rules are or even whether the administration itself may break the rules, it puts people in a lot of fear and uncertainty.”

CL: Back in January, Providence officials moved to add language to a preexisting ordinance on Providence’s status as a sanctuary city. It was then reported that the passing of the ordinance was delayed by Providence officials to consider whether the amendments could have the opposite effect of their intentions; that is, ICE doubling down on Providence if the city seeks to codify protections for those lacking legal status. Is that a true unintended consequence?

SB: I understand the concern, but I think it would be a mistake to give in to it. The Trump administration is targeting anybody they can, and it would be a mistake to think that if you lie low, nothing will happen. The most important thing that municipalities can do is indicate they’re not going to back down. I mean, states can’t do anything and everything—ICE has certain powers that no state or municipality can reject. But to the extent federal law does not prohibit steps to protect immigrants, states need to fully move forward.

CL: The ACLU is currently pushing for the 364 Day Misdemeanor Bill at the Rhode Island State House. This bill is now in its fifth year of being proposed. What would its passing mean for immigrants in Rhode Island?

SB: The 364 Day Bill deals with a gap in state and federal law. In Rhode Island, a misdemeanor is a crime that carries a sentence of up to one year. Federal immigration law says that if you commit certain crimes, like felonies, that carry a potential sentence of one year or more, you can be subject to automatic deportation. Because federal immigration law talks about one year or more, it captures minor offenses in Rhode Island.

This bill changes the definition of misdemeanor in Rhode Island from a year to 364 days. By making that one-day change, you can protect immigrants from this automatic deportation law under the federal immigration statute. That’s something we and immigrant rights advocates have been pushing for a number of years now, and it’s become so much more important this year in light of what the Trump administration is doing.

CL: These are most definitely trying times. How are you able to keep sustaining a fight for fundamental rights?

SB: This is an administration that is throwing everything against the wall and seeing what sticks. It is draining and exhausting, but there needs to be a consistent and constant response to these really extraordinary efforts to take away civil liberties from a wide variety of individuals and organizations in ways that we think are deeply anathematic to what the Constitution and Bill of Rights are all about.

by Audrey Gmerek ’28, an Economics and International and Public Affairs concentrator and a Staff Writer and Multimedia Photojournalist for BPR illustrations by Shay Salmon ’27, an Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

That Facebook message may be more than a simple request from an old friend pushing you to try a new skincare product. It could be an entry point into far-right radicalization.

From the outburst of Tupperware parties in the 1960s to the widespread sale of supplements and essential oils on antivaccine Facebook groups in the last decade, multi-level marketing (MLM) has become embedded in American culture. These businesses draw upon American principles of personal entrepreneurship, self-reliance, and upward mobility, operating through a top-down structure that hands the responsibility of sales to individuals while offering incentives to recruit others into the business. By promising to reward their members for selling products and recruiting new distributors, multi-level marketing strategies indoctrinate people into a business model of social networking and female entrepreneurship. However, MLM schemes have faced scrutiny for failing to uphold their promises, leaving many participants misled, in debt, and jobless.

Through both relational and ideological recruitment strategies, MLMs have created a framework for modern conservative womanhood and far-right community building. MLMs and political conservatives have a shared desire to uphold free market capitalism and traditional gender roles. Moreover, despite legal and ethical concerns, MLMs continue to thrive in large part due to protection from conservative politicians. President Donald Trump’s previous Secretary of Education, Betsy DeVos, whose family owns Amway, one of the largest MLMs in the United States, has leveraged her influence to keep MLMs out of the teeth of the Federal Trade Commission.

By offering an illusion of economic freedom through a “side hustle,” MLMs provide a supposed escape from the paternalism that comes

with a corporate 9 to 5. The flexible work they offer appeals especially to stay-at-home moms, solidifying traditional gender roles despite offering the illusion of empowerment. Additionally, MLMs promote their sales groups as supportive communities where women can socialize, turning sisterhood and friendship into a tool for recruitment. In doing so, MLMs exploit stereotypical feminine characteristics such as approachability and emotional appeal that are believed to make women better recruiters and salespeople.

“Through both relational and ideological recruitment strategies, MLMs have created a framework for modern conservative womanhood and far-right community building.”

Recruitment rarely happens through direct sales pitches but rather through subtle social pressure. “Hey girl!” messages from acquaintances sharing their “life-changing” opportunities flood women’s inboxes.

Offline, pitches frequently take place in familiar, trusted settings such as churches, where people share testimonies about how their business strengthened their relationship with God. This personalization and trust-building can frame MLMs as a community rather than a purely economic venture, making it easier to indoctrinate and recruit others. The sense of intimate community also helps with retention, as women fear losing their friends, not just their income, if they leave.

While the rhetoric of entrepreneurial empowerment may appeal to liberal-leaning feminists, MLMs are often more widespread in religious social circles that have historically upheld more conservative ideals. In American communities that maintain strong traditional roles, such as Mormon and Evangelical circles, MLMs tend to proliferate. Deborah Whitehead, an associate professor of religious studies at the University of Colorado Boulder, stated that “missionary training translates well into direct sales” and that “[Mormon] communities tend

to be tight-knit and close, so when somebody is passionate about a product, it will be easier to go into these circles and sell it.” Similarly, the Christian appeal of MLMs is rooted in the teachings of the Prosperity Gospel, a theological belief that wealth is God’s recognition of faithfulness. The presentation of an MLM as an alternative to corporate paternalism aligns with the anti-establishment conviction that has gained traction within the populist MAGA movement. During the pandemic, anti-vaccine misinformation was used to promote MLM wellness products. Many wellness influencers took to social media to criticize the Biden administration’s “paternalistic” Covid-19 restrictions while promoting certain MLM products, such as Patriot Wellness Boxes, that supposedly offer an alternative to “woke” medicine. By pushing women to engage in political discourse through sales pitches, these

frameworks for MLM recruitment allow for the implicit dissemination of far-right beliefs. Sociologist Gina Marie Longo described the phenomenon as “Pastel QAnon Indoctrination,” where radical ideologies are introduced through a softer, feminine-coded approach.

While not all MLMs push extreme conservatism on participants, they do create close-knit networks of women that can be more easily influenced by such narratives. What begins as a friendly sales pitch or an invitation to a product event could be a pipeline to persuasion, using these extensive social networks to sell QAnon beliefs.

“What begins as a friendly sales pitch or an invitation to a product event could be a pipeline to persuasion, using these extensive social networks to sell QAnon beliefs.”

by Tess Naquet-Radiguet ’ 27, a Behavioral Decision Sciences and Political Science concentrator and Senior Editor for BPR

visualization by Carys Lam ’29, an Architecture major at RISD and Data Designer for BPR

Leaves burst into a dizzying array of colors, softly alighting on the ground with each new gust of wind. Rain rivulets stream down a foggy window pane as embers crackle in the enchanting glow of a fireplace. For some, autumn descends in these details, in little drops of joy that stall the impending chill of winter. But for most, fall arrives on one opportune moment in August: the day Starbucks releases the Pumpkin Spice Latte (PSL).

Although the PSL might have once been relegated to young white women, it has persisted as a staple of American culture for over two decades and is now beloved across generations. Pumpkin spice products quickly expanded from coffee—to snacks, scented candles, body butter, and deodorant—to such an extent that it is now the seasonal flavor consumers anticipate most. In just three months each year, pumpkin spice products generate over half a billion dollars in revenue, with demand continuing to rise. We pay an average of 7.4 percent (and up to 161 percent) more for pumpkin spice products compared to non-pumpkin alternatives, yet we are not deterred from purchasing these products. The remarkable popularity of this distinctive blend of spices highlights how our shared zeal for little luxuries has turned into something deeper than a simple craving for seasonal products. As a form of consumption largely insulated from political maneuvering and economic volatility, little luxuries transcend social divisions, uniting us under a shared consumer identity. In today’s increasingly pluralistic society—in which traditional sources of national identity such as religion, ethnicity, or class have become less central—these small indulgences have allowed us to cultivate our individual and social identities through their consumption.

Little luxuries empower us to develop a sense of self through our consumer choices, embodying the ethos of individualism that pervades American society. In the midst of economic uncertainty and societal turmoil, maintaining a feeling of control over our decision-making aids our “long-term emotional regulation.” The psychological stability we derive in turn fosters greater self-cohesion. While Millennials and Gen Z are the two generations most likely to partake in the ritual of an autumnal pumpkin spice latte, the tendency to splurge on little luxuries is not new. Recession-driven consumption often trends toward these kinds of products, as cost-prohibitive goods like a car or a house feel increasingly unattainable. The philosopher Herbert Marcuse suggested that people “recognise themselves in their commodities,” and in the absence of these larger identity-defining purchases, routinely buying little luxuries can provide a “manageable form of self-expression.” Being a “person who drinks pumpkin spice lattes” becomes an identity anchor we can hold onto, and as we navigate an increasingly unpredictable world, what harm is there in allowing ourselves that comforting indulgence?

Some might contend that these purchases are financially irresponsible—that it would be wiser to save money to eventually buy a car or a house. This reasoning is naive. The median down payment for a home in 2025 is above $50,000; the average price for used cars hovers around $25,000. Abstaining from pumpkin spice would, on average, save $45 a month for Gen Z and $64 a month for Millennials. Neither of these figures is anywhere near high enough for the savings to compound into an amount that would allow us to invest in capital-intensive goods.

“As a form of consumption largely insulated from political maneuvering and economic volatility, little luxuries transcend social divisions, uniting us under a shared consumer identity.”

Instead of decrying them, we should appreciate how consuming little luxuries has become a prosocial activity that bolsters our sense of communal identity. These goods are mass-produced commercial items marketed across social strata as seasonal necessities. They are neither exclusive nor hard to come by, and therein lies their appeal. Through their accessibility, little luxuries become a relational element around which broader communities can coalesce. Our consumer habits signal group membership, and as fall breezes in, the wafting aroma of pumpkin spice draws hordes of friends to coffee shops, giddy in anticipation of sipping a whimsical seasonal coffee. They savor its warmth, revel in the nostalgia it elicits, and delight in bonding with others who similarly appreciate the little luxury. As we interact with people who share kindred purchasing habits, the practice of consumption itself becomes a unifying force that bolsters our sense of belonging, while the consumer space becomes a third place in which to cultivate connections. It has been shown that “very socially embedded practices and feelings can be the most powerful of all,” and as pumpkin spice continues to promote a culture of taste, we integrate into both our individual and collective identity, we can only benefit from the social cohesion that arises.

While there are certainly legitimate critiques of consumerism, it is worth examining its

aesthetic and moral judgments more closely— judgments that focus on “not how much we consume, but what we consume.” Such critiques frame our penchant for pumpkin spice as a moral defect—an impractical purchase preventing us from engaging in more “upstanding” forms of consumerism. However, such judgment “veers dangerously close, or even into, outright snobbery,” echoing historical “elite disdain” for working-class consumption habits.

If we look beyond these stereotypical views of “little treat culture,” it becomes clear that such indulgences serve an important purpose: They democratize desire beyond mere consumer need, embodying the myth of American equality—a cornerstone of our national identity. No longer are indulgences or a sense of luxury prescribed to the wealthy. Consumers are able to partake in superficial spending on a scale that would not have been possible decades ago, allowing the appeal of little luxuries to straddle socioeconomic strata, captivating most consumers with disposable income. Today, the PSL is available in most coffee shops from September to November and costs an average of $6.50. While one could argue this price point is still extravagant, it is not cost-prohibitive for the average American—who spends over $40 per month on coffee. Given this, a weekly seasonal drink does not seem to be a disproportionate purchase for the average consumer, especially when the PSL fosters a sense

“In just three months each year, pumpkin spice products generate over half a billion dollars in revenue.”

of symbolic belonging—a cultural universality that reflects and sustains the American ideal of equal opportunity.

By transcending socioeconomic divisions, consuming little luxuries becomes an identity broad enough to empower our sense of self, bolster our social cohesion, and sustain our cultural horizon of democracy. It is an identity that stems not from any inherent ideological or value-based characteristic but from our most basic craving for connection and stability. So, if the process of buying little luxuries bolsters these feelings, why deny ourselves that joy? We should instead take comfort in the fact that, despite political contentions, economic uncertainty, and social turmoil, we can continue to turn toward consumerism. And what better way to luxuriate in that reality than with a pumpkin spice latte, sitting back and watching as leaves burst into a dizzying array of colors?

The abundance movement must build a coalition to achieve its goals

by Ava Rahman ’27, a Political Science and English concentrator and Editor for BPR illustrations by Ellie Lin ’27, an Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

At a DC conference this September, a coalition of politicians, Yes In My Back Yard (YIMBY) activists, investors, academics, and 2000s-era policy wonk bloggers-turned Substack writers rallied behind a common cause: the ‘Abundance Agenda.’ The guest list had more than tripled from last year, with a waitlist of over 300, according to an internal email. Featured speakers included Ezra Klein, Utah Governor Spencer Cox, and Nvidia policy director Levi Patterson. Attendees discussed pathways to energy, housing, technology, and finance abundance. They cycled through the Grand Ballroom for lunch and enjoyed Happy Hour on the lawn. There was a sense of momentum, of putting the pedal to the metal and steering toward shared goals. Earlier in the year, Open Philanthropy announced their $120 million Abundance and Growth Fund and House Democrats formed a Build America caucus. But as the event drew to a close, Abundance thinkers were left with the same question facing any burgeoning movement: How do ideas scale across ideological divides, both across the partisan aisle and within the Democratic Party itself? In other words, how big is the tent?

The Abundance Agenda was popularized by Ezra Klein and Derek Thompson’s best-selling book in May 2025, but the grist of these ideas has circled in academia and California’s YIMBY affordable housing movement since the 2008 financial crisis. “Abundits” look under the hood of America’s broken infrastructural system to understand why government—particularly in liberal states—struggles to meet demand for essential public goods ranging from housing to healthcare. Why has California fallen years behind countries like Japan, France, and China in building high-speed rail? Why does it cost twice as much to build multifamily housing in California than in Texas? According to Klein and Thompson, the problem is not a lack of resources or political will—it is the process. In the 1970s, good intentions led to unforeseen consequences when progressive reformers built regulatory and oversight mechanisms to thwart corrupt centralized power. In doing so, they hamstrung the government’s ability to act effectively. Rules and regulations bog down infrastructural advancements in layers of bureaucratic procedure while “vetocracy-style” governance allows local interests to stymie attempts to build more housing, transit, and renewable energy. The Agenda

“The Abundance Agenda is less of a fixed ideology than an emerging policy framework that should harness coalition-building toward greater ends.”

advocates for a robust government that can get out of its own way to achieve its goals, steering innovation and stepping in when markets fail to deliver.

Abundance’s critique of status quo liberal governance has polarized Democratic factions, with left-leaning critics dismissing it as a neoliberal Trojan horse that diverts attention from welfarist programs. However, political infighting is not inevitable. Abundance cannot yet aspire to big-tent politics because parts of its theory are still nebulous. Much of its discourse centers on output and technical process while failing to reconcile larger issues of political division. As a result, the Abundance Agenda is less of a fixed ideology than an emerging policy framework that should harness coalition-building toward greater ends.

Many progressives have already recognized Abundance’s potential. At a rally, then-NYC mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani called for “[delivering] an agenda of abundance that puts the 99 percent over the 1 percent.” On a podcast with Derek Thompson, he acknowledged the importance of an effective and efficient government to manifest affordability and “public excellence.” He interpreted Abundance policies as narrow reforms to state capacity. However, it is unclear whether the left and center have the same understanding of what inefficiency means in the real world. For instance, when discussing the ballooning costs of the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Long Island Rail Road Project, the two reached an impasse: Mamdani critiqued utility corporations while Thompson pointed to costly union regulations.

“For better or for worse, politics is about coalitions: congressional bargaining, legislative carve-outs, and a process of give and take between political factions.”

A look at several failed infrastructural projects reveals that Abundance’s diagnosis of overzealous regulation aligns with the left’s framing of the “oligarchy problem.” Take the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment (BEAD) Program, former president Joe Biden’s recent effort to fill in gaps of high-speed internet access in rural areas. On the Jon Stewart show, Klein explained what went wrong, rattling off the endless steps of the federal grant applications that resulted in severe delays. “My hair was dark when we started this process,” Stewart joked at the end. The clip went viral, inciting outrage from progressive journalists like Ryan Grimm, as well as Former Deputy Director of the

National Economic Council Bharat Ramamurti, who pointed out that Republican senators and telecom behemoths had worked to enervate key provisions of the bill. Both stories are true. Biden envisioned internet access as a public good and aspired to the top-down efficiency of former president Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Rural Electrification Program. However, congressional politics and waning trust in government chipped away at federal control of the policy. Leveraging Congress’s overcaution and federal agency disorganization, large telecom companies challenged internet affordability requirements, mapping inaccuracies, and existing bids in an attempt to push out smaller or public competitors.

The resulting delays in implementing BEAD were therefore partly caused and exacerbated by corporate creep. Senate Republicans now condemn BEAD’s overrgulation, but their criticism is a caricature of Abundance. A sounder approach from the Biden administration would have borrowed progressive antitrust tactics, such as common-carrier regulations or a federally administered bidding process, to enable more efficient coordination.

The BEAD example shows that Abundance must contend with political power dynamics. Brown research fellow Marc Dunkelman, who spoke at the recent Abundance conference and published his book Why Nothing Works this year,

expands the reformist agenda into a broader theory of power. More than bureaucratic process, his version of Abundance criticizes the creation of an overcautious government tiptoeing around the interests of various non-government actors: Sometimes the problem is corporations, sometimes it is unions, and sometimes it is local home owners. The greater issue is how interest group politics have captured the production of goods. That does not mean government should bulldoze through the concerns of local populations and usurp union bargaining in the name of efficiency. Rather, a more intentional balance must be found in every government endeavor between catering to local demands and putting boots on the ground to see projects to fruition. As Dunkelman argues, it is about contending with two strands of progressivism: Hamiltonian topdown control and Jeffersonian localized leadership. Through this lens, Abundance need not incite a battle within the left but should promote a thoughtful and interwoven dynamic between centralized and decentralized leadership.

In reality, however, managing these two tendencies requires looking beyond technocratic prescriptions—which nitpick the machinery of policies—to confront political trade-offs. In

California, Governor Gavin Newsom was forced to alter provisions of his Abundance-esque affordable housing bill after union advocates protested its wage requirements in budget hearings. This example reveals a current shortcoming of the Abundance agenda: While it diagnoses the traffic jam of competing interest groups, it does not propose a solution for resolving those cross-coalition rifts. At its worst, some Abundance followers resort to blaming unions as part of the problem. Klein and Thompson avoid this political quagmire by asserting that union interests can coexist with Abundance policies, pointing to how European countries carry out cheaper and faster infrastructural projects with high unionization. But they do not address the crucial gap in this argument: Europe’s political economy is fundamentally different from our own. The welfare state means worker wages do not have to shoulder the burden of healthcare and general high living costs. Competing interests of government, employers, and workers are mediated through tripartite agreements, a centralized decision-making process contrasting collective bargaining in the United States. American unions have adapted to political conditions where lobbying instrumentalizes

self-interest and low union membership fuels a destructive insider-outsider competition between members and non-members over who gets the share of jobs. It does not have to be this way. Progressive thinkers have an opportunity to build on this gap in Abundance theory. Even modest deregulatory reforms require a powerful realignment of interests, revealing the need for deeper remedies to current structural flaws that embolden self-interest at the expense of the common good.

The Abundance Agenda emerges in a fraught political moment as Trump hacks away at the federal government and the Democratic Party finds itself rudderless in the right-drifting tide of the electorate. For better or for worse, politics is about coalitions: congressional bargaining, legislative carve-outs, and a process of give and take between political factions. Klein, Thompson, and Dunkelman’s analysis of late-20th century Progressivism reveals how movements are shaped by unforeseen consequences as ideas adapt to policies, and policies gain a life of their own. Now, Abundance is in its theoretical, public-comment stage. To see the movement’s actualization, we need to put shovels in the ground.

“Rules and regulations bog down infrastructural advancements in layers of bureaucratic procedure while vetocracystyle governance allows local interests to stymie attempts to build more housing, transit, and renewable energy.”

Digital technology has reshaped Gen Z’s dating rituals

by

Ashton Higgins ’26, an Anthropology concentrator and Managing Magazine Editor for BPR illustration by LuJia Liao ’26, an Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

Pavlov’s process of classical conditioning is pretty simple: If he rang a bell every time he gave his dog a treat, the dog would begin to salivate at just the sound of the bell. Now, imagine that instead of a dog, it is everyone aged 15–30. Instead of ringing a bell, it is tapping a heart-shaped button on an Instagram story. And instead of a treat, it is sex. The routinization of romance on digital interfaces has done away with the ambiguities of inperson flirting. We can now receive a ‘like’ on our Instagram story and suspect that that person is into us. The art of relationship building that comes from learning someone’s personality, tics, and communication style is disappearing in our inept search for clarity via conditioned digital behavior.

This conditioning of digital gestures has generated a new set of romantic rituals: liking Instagram stories or dating app profiles to show interest in someone; texting, commenting on their posts, and sending them reels once you start hooking up; posting with them and deleting dating apps once things are serious. These behaviors have become so standardized among young people that they serve as widely understood signals of intimacy and celebrations of different levels of commitment.

Standardizing our signifiers of romantic interest and relationship status has not eliminated as much ambiguity as we might think. True, it now seems easier to tell if someone likes us, but how many other guys is he matching with? Does her liking my story mean she wants to date or just have sex? It seems obvious when some people are hooking up and some people are dating. But he also commented the same emojis on her post, although he claims they are just friends… Is he hooking up with both of us? She did not post for ‘National Boyfriend Day’ this year—does that mean I can ask her out?

“Abstracted indicators of interest not only oversimplify human interaction but also condition users to read into the smallest of interactions.”

Opening up new modes of interaction and communication also opens up new avenues of confusion. We are grappling with the illusion of a clear and standardized digital semiotic system. What liking a post means to one person might mean something else to another, despite our best attempts to assimilate everyone into a universal romance language.

We cannot reconstruct the Tower of Babel—a sanctuary where everyone speaks the same language—because flaws in human communication are unavoidable. It is impossible to express our complex internal thoughts and feelings perfectly. It is impossible to understand someone else fully. It is even more impossible to attempt either of these goals using abstracted buttons on screens rather than complex human languages, body language, pheromones, touch, and other facets of in-person human communication.

Abstracted indicators of interest not only oversimplify human interaction but also condition users to read into the smallest of interactions. The hyper-analysis of micro-interactions online, such as liking stories,

“How are we meant to emotionally mature into adulthood if we run away from our problems, drowning our anxiety in instant gratification?”

of options while also potentially deluding us into setting expectations for partners that are beyond reason, feeding a rejection mindset that restricts us from ever finding a romantic interest outside the internet.

For some people, digital romance is enough. Texting people on dating apps, getting likes on their posts, and knowing that there are tons of hot people out there is gratifying enough that they do not pursue relationships or sex. However, as much as the internet may satiate some people’s sexual desires, the ongoing mental health crisis points to another cause of less sex among young people: despite hyper-sexuality online, more young people are anxious and depressed than ever before. Some people might have a roster but are too anxious to do anything about it offline. Other people may have had such bad experiences with digital romance that they are swearing off relationships and sex altogether. The mental health crisis and increased isolation will only further preclude Gen Z from finding love.

has led to a dating landscape that traces “connections” across so many incremental stages of commitment that it is difficult to tell what is allowed and when. The complex and ever-changing rules of modern dating, coupled with the oversimplified nature of the digital language tools at our disposal, are bad news for any of our parents hoping to see a wedding or grandchildren anytime soon.

Beyond modes of communication, shorter attention spans may be undermining our ability to foster monogamous relationships. We are less capable of deep introspection; when we sense tension in a relationship, we are more likely to run away from the discomfort and self-soothe by swiping on Tinder or posting a thirst trap to see who it. Instant gratification has conditioned us to expect constant entertainment and dopamine release: If a relationship starts to get tough or boring, we are psychologically conditioned to end it and find pleasure elsewhere. We cultivate “rosters” of romantic interests to turn to at the slightest inconvenience as a defense mechanism against sitting in difficult emotions. We are becoming worse at thinking through our own problems and sticking around through someone else’s. This phenomenon is stunting per sonal development: How are we meant to emotionally mature into adulthood if we run away from our problems, drowning our anxiety in instant gratification?

As a consolation, at least we can expect that young people are gaining more sexual experience than previous generations, right? Wrong. Studies show young people today are having less sex than previous generations. “Rosters” of Tinder and Hinge matches and loyal “story-likers” not only disincentivize commitment to serious rela tionships; they also disincentivize doing anything multiple options can overwhelm and paralyze us from acting on anyone. Having multiple lines of communication open at once means no one ends up texting back in time to actually coordinate a date. And the swarm of hot, algorithm-picked “micro-celebrities” on our feeds increases the illusion

More than anything, streamlining and “simplifying” communication sacrifices the bedrock of intimacy and developing chemistry—the excitement and intrigue inherent to real-world interactions. Going up to the hot guy at the bar in a burst of spontaneity, the serendipity of asking out the pretty girl on the train, not knowing if that person wants to get coffee as a date or just platonically… In the real world, there are no buttons, and we cannot swipe. The only way to find out if someone can be a connection is to engage in a real, face-to-face conversation that, while also ambiguous in some ways, is more informative than we give it credit for. Body language, tone, eye contact, and pheromones all help foster an understanding of intimacy that is inaccessible online. Going through the motions of preset micro-stages of intimacy is inhuman. We should not classically condition ourselves into relationships with the right ding of a notification bell.

by Remi Takahashi ’28, an International and Public Affairs and Gender and Sexuality Studies concentrator and Staff Writer and Business Associate for BPR

illustration by Airien Ludin ’26, an Illustration master’s student at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

When a girl gets her period in parts of rural Nepal, she is whisked away to a small shed outside of her village and exiled until she stops bleeding. She is quarantined—cut off from her family, denied nutritious foods, and prohibited from bathing or sharing the village’s water. Going to school or any public place is impossible because menstruating girls are considered “impure.” This isolating ritual, known as Chhaupadi, is a monthly reality for countless Nepali girls and women.

In addition to the social exclusion inherent to the practice, it is also responsible for the death or illness of numerous women due to the denial of food and water. These indignities and tragedies have led to a durable pressure campaign from domestic and international activists aimed at banning and penalizing the ritual. Yet, despite legal bans and international campaigns, Chhaupadi persists in many rural communities of Nepal. Why? Lackluster state enforcement, geographic isolation, and the deep cultural resonance of the practice are important—but they only tell a part of the story.

Outlawed rituals such as Chhaupadi persist not only because of cultural entrenchment and weak enforcement but also because the majority of eradication originates from external campaigns and stakeholders that are met with community resistance. Subsequently, most campaigns against Chhaupadi have been misguided, inattentive to local contextualization and

the symbolic and communal value of the ritual. Effective change requires approaches that engage with, rather than erase, the ritual’s social and cultural significance.

The practice of Chhaupadi is rooted in the belief that menstruation is a curse on women from Indra, the Hindu god of weather. While menstrual taboos in Hindu regions are not uncommon, they take different forms. In urban Nepal, for example, menstruating women are restricted from entering sacred and public spaces but are not typically forced into exile. A practice as extreme as Chhaupadi only takes place in specific rural areas of Western Nepal, where social change seems to be relatively slow.

Exposed to the elements and deprived of nutrients, several women are killed each year because of Chhaupadi rituals, and many more are harmed. While many cases go unreported, 16 women and children were reported to have died in 2019 alone due to Chhaupadi from causes such as suffocation, snakebites, and smoke inhalation during their quarantine. After three highly publicized deaths among women and girls practicing Chhaupadi, the Nepali Parliament further strengthened its ban on the ritual by imposing a fine and/or a three-month jail sentence for anyone forcing a woman to follow the custom. Yet these legal efforts have floundered in its aim of eliminating those that practice Chhaupadi, in part because of the deeply

“Effective change requires approaches that engage with, rather than erase, the ritual’s social and cultural significance.”

entrenched menstrual taboos that are associated with the ritual and the communal value it possesses.

Both men and women play a role in continuing Chhaupadi and its rituals. Mothers teach the practice to their daughters, linking generations of women to an inherited tradition of silence and shared suffering. At the same time, male community leaders take on the duty of traditional norms by reinforcing conformity, justifying the practice with ideas of cleansing and family sanctity. Beyond the communal aspects, both women and men continue to pass on these rituals because of their fear of divine retribution or other punishment.

Despite the failure of the legal system to end Chhaupadi, the opposition movement has continued apace. Activist groups, the state, and international organizations have stepped in to pursue the eradication of Chhaupadi as a human rights violation. A well-intended social change campaign led primarily by government officials, district police officials, and nongovernmental organizations began physically destroying menstrual sheds, which are known locally as Chhau goth, in an attempt to render certain villages

“Chhaupadi-free.” However, these efforts often backfired. Birati Rokaya, from a remote village in West Nepal, expressed, “‘The police demolished our chhau goth, only adding to our hardships… when a group of women gets their periods, we stay out in the fields. It’s difficult but we have to observe Chhaupadi anyhow. It is our custom.’” Rather than eliminating this ritual, these interventions have left women even more vulnerable and led villagers to secretly rebuild the shelters soon after their destruction. The efforts to physically destroy the practice of Chhaupadi failed to eradicate its ideology in the minds of its practitioners. It is not enough to destroy the physical vehicles of Chhaupadi; rather, the beliefs that form the roots of the practice must be transformed.

Educational interventions have been used to address the broader menstrual taboos that are foundational to Chhaupadi. However, these efforts have their own flaws. Local communities are reluctant to abandon regressive menstrual practices, and women who have stopped practicing Chhaupadi have faced discrimination and punishment within their communities. The depth of this ingrained tradition is further illustrated by local leaders themselves. Village council member Nirmala Bista, who organizes public awareness campaigns against “harmful practices,” ironically still follows Chhaupadi in Bajhang, Nepal. She says, “‘My father-in-law and mother-in-law fall sick if I don’t practice the tradition.’” Her words highlight a striking paradox—representatives of women and even rights activists are also bound by this ritual and communal pressure due to their spiritual beliefs. Thus, misguided efforts such as demolishing sheds and demystification initiatives by government bodies and international and national organizations fall short of eradication.

“It is not enough to destroy the physical vehicles of Chhaupadi; rather, the beliefs that form the roots of the practice must be transformed.”

These contradictions raise fundamental questions about the effectiveness of interventions designed by outside entities, such as the central government and nongovernmental organizations. Programs that do not account for cultural and religious implications, or the dignity and sovereignty of local people, often fail to take root. While activists emphasize the unhygienic practices and dangers of Chhaupadi, many villagers view these same rituals as essential to maintaining divine order. Campaigns that fail to engage local leaders, mothers, and elders risk being dismissed as outside interference rather than accepted as collective progress. This tension between external intervention and community agency highlights why Chhaupadi eradication efforts have been so flawed. Is it right for external forces to step in and eradicate a communal ritual in the name of human rights and universal law? Or does such action risk becoming another form of cultural domination and misunderstanding cloaked in the Western hegemonic language of human rights?

If we consider Chhaupadi not only as a harmful practice but also as a symbolic ritual, it becomes clear that any effort to end it must provide an alternative source of meaning and cohesion. Rituals, after all, are not easily abandoned: They help communities navigate uncertainty, fear, and identity. For many families, Chhaupadi has served as a ritualized way of managing the anxieties surrounding purity and divine retribution. Simply removing these rituals risks leaving a cultural void—one that communities may instinctively resist. The question, then, is not just how to erase Chhaupadi but also how to nurture new rituals that affirm women’s dignity and are reflective of local traditions rather than imposed by outsiders. Such approaches could include shifting the meaning of the ritual toward empowerment, all while maintaining the independence of these communities.

The question of whether external forces should intervene in practices

Chhaupadi does not have a simple answer. On one hand, the ritual endangers women’s health, safety, and equality, making intervention appear not only justified but also necessary. On the other hand, external resolutions and laws without genuine dialogue risk silencing the voices of the very communities they claim to protect, sparking backlash and stifling discourse. The challenge, then, lies not in choosing between human rights and cultural autonomy but in seeking ways to bridge them with alternatives that carry symbolic meaning and foster change from within.

Civic engagement, not rituals, should define patriotism

by Sabine Cladis ’29, a Political Science and English concentrator and Staff Writer for BPR illustration by Emily McShane ’29, a Film, Animation and Video major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR

Students across the United States engage in mundane forms of patriotism every day. In acts of civic participation—attending protests and marches, registering voters, volunteering at clinics, and building campus coalitions—students demonstrate their dedication to democratic engagement. However, there is a disconnect between student participation in patriotism and the ritualistic performances of patriotism expected of them by their government. Rather than being embraced as fully formed participants in democracy, students are treated as subjects in need of explicit guidance. Of these performances, none is more striking than the Pledge of Allegiance. The Pledge was designed as a reactionary ritual responding to anti-immigrant sentiment with a nativist assertion of national identity: “One Country! One Language! One Flag!” In the 21st century, the Pledge and other mandated rituals ring hollow and performative; the contrast between government-imposed patriotism and students’ active engagement demonstrates that authentic patriotism emerges from civic participation, not ritual repetition.

Schools have again become sites for nationalistic displays and curriculum restriction, with conservative policies such as the Promoting American Patriotism in Our Schools Act (H.R. 1351) seeking to promote patriotism through ritual mandates. This bill would not only institute the Pledge as mandatory for students and staff alike (minus religious exemptions) but would also shape and restrict school curricula. In other words, this bill would enable the state to dictate the content and form of a mandated nationalist education. This narrowing of classroom discourse enforces a vision of patriotism embodied by conformity rather than expressions of individual liberty and engagement in politics.

Yet, despite these mandates, classrooms remain one of the most poignant spaces to cultivate a deeper, more democratic patriotism. As a study on students’ attitudes toward patriotism in the classroom indicated, “students’ critiques did not exist in parallel or in contradiction to their patriotic commitments. Rather the two were integrated.” Candid

“When students express patriotism through authentic activism, they reclaim its purpose by demonstrating that genuine civic engagement must not be mandated but fostered collaboratively.”

discussions about injustice serve to foster community and encourage the kind of “critical democratic patriotism” that students themselves advocate for in and out of the classroom. Honest and critical teaching and learning enable accountability, productive discourse, and authentic national commitments. In contrast, the restrictive and ritualistic policies that the Trump administration intends to pursue polarize individuals and suppress the democratic principles fought for by the original patriots.

Recent civic engagement—most notably the widely covered proPalestinian student protests across college campuses—embodies student-driven, authentic patriotism. These expressions are labeled by the Trump administration as uniformly violent, destructive, and antiAmerican. However, peaceful demonstrations have a long history in

the United States. Take, for instance, the student protests against the Vietnam War during the Cold War era. At Kent State University, the Ohio National Guard was deployed, fully armed, and killed four students. This harsh response against student speech echoes the current government crackdown on domestic and international students protesting for peace in the Middle East. The insistence on quashing criticism and public outcry exposes a national hypocrisy: in an effort to preserve a placid image of democracy, the state suppresses the expression of democratic principles.

The contrast between student engagement and mandated rituals highlights the waning significance of the Pledge in modern life. This ritual no longer carries the weight its architects intended—what was meant to cultivate national devotion has become performative, a recitation that feels empty and persists only due to precedent. For positive American patriotism to hold sincere meaning, it must diverge from compulsion and rote repetition. This is not to say that all rituals that manifest in the form of patriotic traditions are ineffective, but when rituals are co-opted and manipulated by the state—imposed as instruments of control and indoctrination within the education system for ideological purposes—they become meaningless and even

destructive to the very patriotic and democratic principles they are marketed as instilling. What was designed to inspire civic virtue has now morphed into a mandate that fosters resentment and a distorted understanding of patriotism as unquestioning compliance. When students express patriotism through authentic activism, they reclaim its purpose by demonstrating that genuine civic engagement must not be mandated but fostered collaboratively.

The Pledge, historically envisioned as an exclusionary nationbuilding oath, now reveals a fundamental tension: policymakers cling to patriotic ritual as students increasingly reject it. Politicians must change how they understand patriotism among young Americans. Patriotism cannot exist as mandated by the state and enforced through policy. Instead, to encourage civic pride among young people, we must trade ritualistic rigidity for dynamic inclusion and active participation within our communities. In rejecting this rigidity, young people— who are so often dismissed as apathetic—demonstrate their ability to redefine patriotism on their own terms and leave behind a legacy of participation rather than performance.

Russia weaponizes remembrance to justify its imperial aggression

by

Alice Miller ’28, a Political Science concentrator

illustrations by Lily Engblom-Stryker ’26

Illustration major at RISD and Illustrator for BPR