TAKING THE REINS

SHORT SECURITY LINES • QUICK BAGGAGE CLAIM • FREE PARKING

BY K E V I N K LI N T WO R T H

Once every fall on a certain Friday night, Oklahoma State decorates the floor of Gallagher-Iba Arena with orange lights, a stage, video screens and plenty of food and drink. The doors open, and several hundred fans of the Cowboys and Cowgirls join the party.

They enjoy their meal, mix and mingle with other OSU faithful, take photos, and then the fun really starts.

They listen and watch history come to life.

The annual Hall of Honor induction ceremony and banquet have become one of the favorite nights of the athletic year — among OSU Athletics sta members as well as those in attendance at an event that is a true celebration of the greatest in the history of the university.

In September, the Hall inducted six new members: Arlen Clark of men’s basketball, Alex Dieringer and Earl McCready from wrestling, Jaime Foutch from softball, Viktor Hovland from men’s golf and Hart Lee Dykes from Cowboy Football.

An evening spent watching induction videos of the honorees, and listening to the emotional speeches of the most legendary figures in the annals of OSU Athletics is a treat that cannot be duplicated.

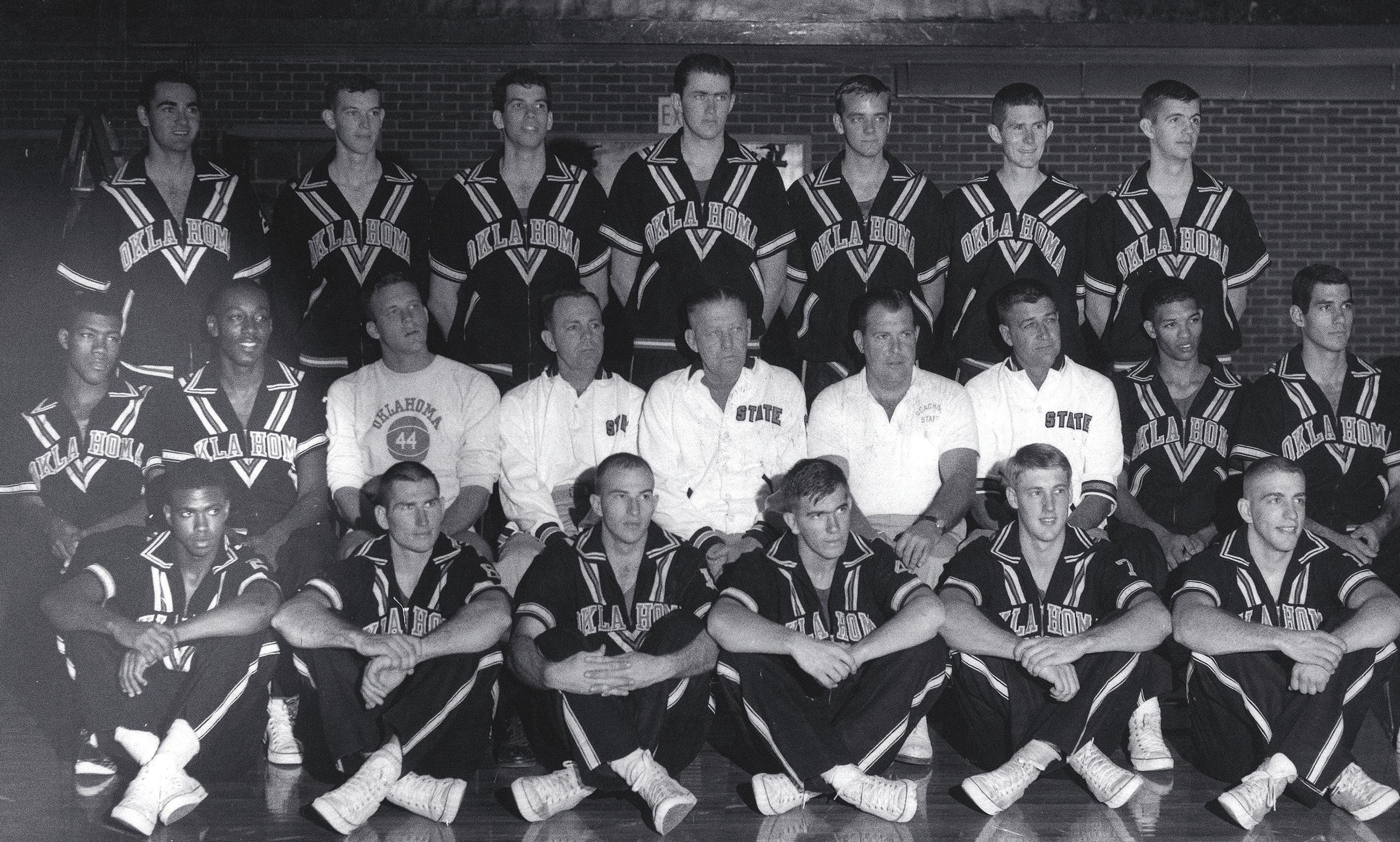

The late Earl McCready, a bruising heavyweight wrestler, is truly one of the concrete blocks on which Cowboy Wrestling was founded. The first threetime NCAA individual champion in the history of the sport originally learned wrestling from a book.

Dieringer, a three-time individual champion in his own right, might have been the best wrestler of the John Smith era. He finished with a career record of 133-4. It’s

the second-best win total in school history — behind only Smith.

Jaime Foutch was a dominating o ensive force in college softball in an era that was mostly silenced by pitching stars. She was the first three-time All-American in program history and ended her career as the Cowgirl record holder in virtually every o ensive category.

Viktor Hovland was unable to attend his induction. He was a tad busy participating in the Ryder Cup for the third time. He is one of the youngest inductees in the history of the Hall of Honor.

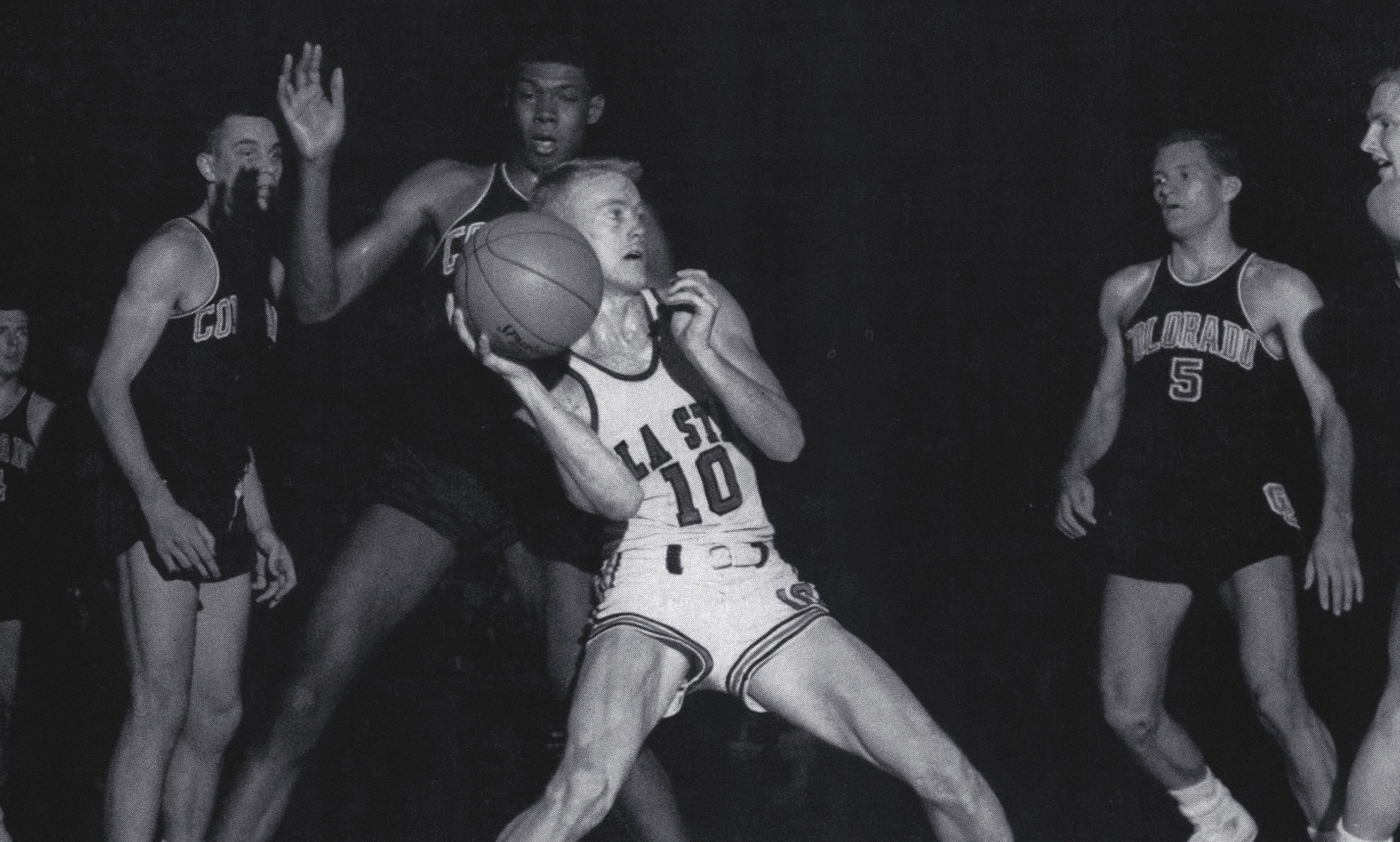

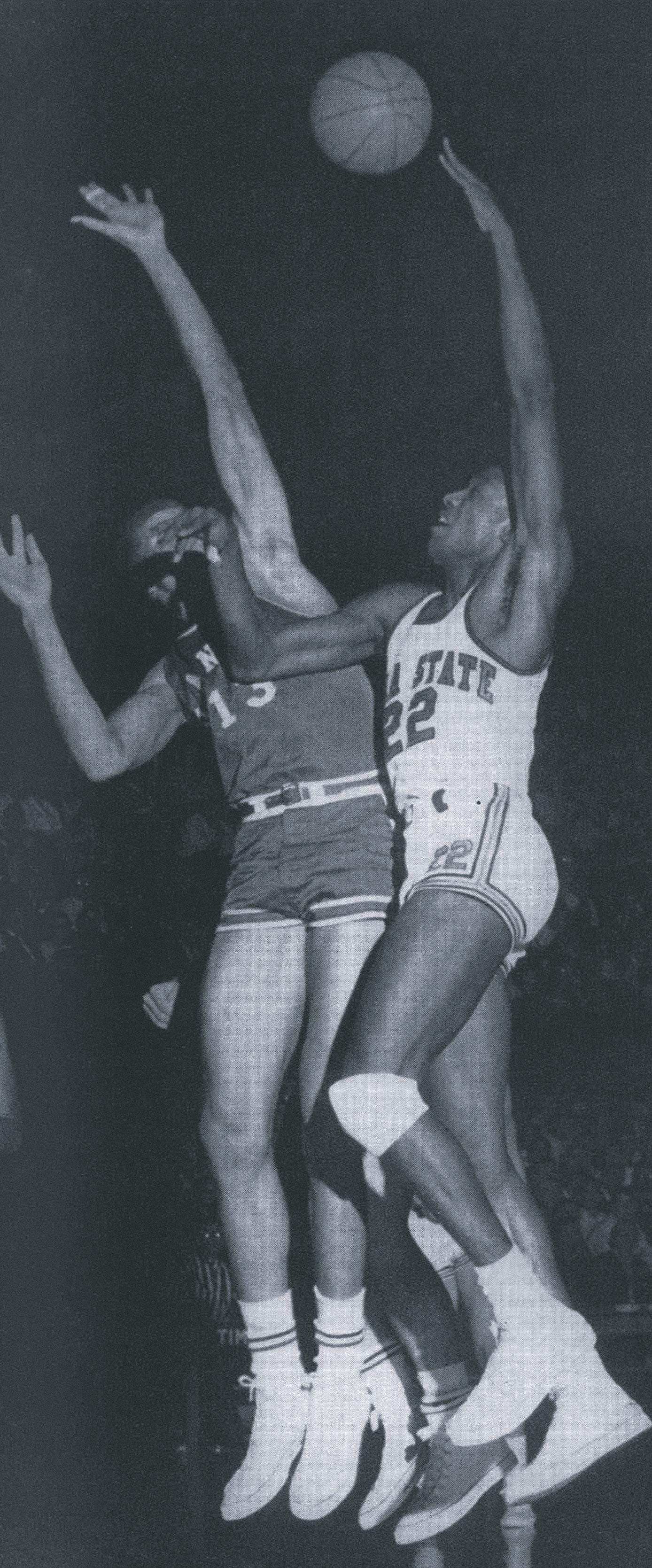

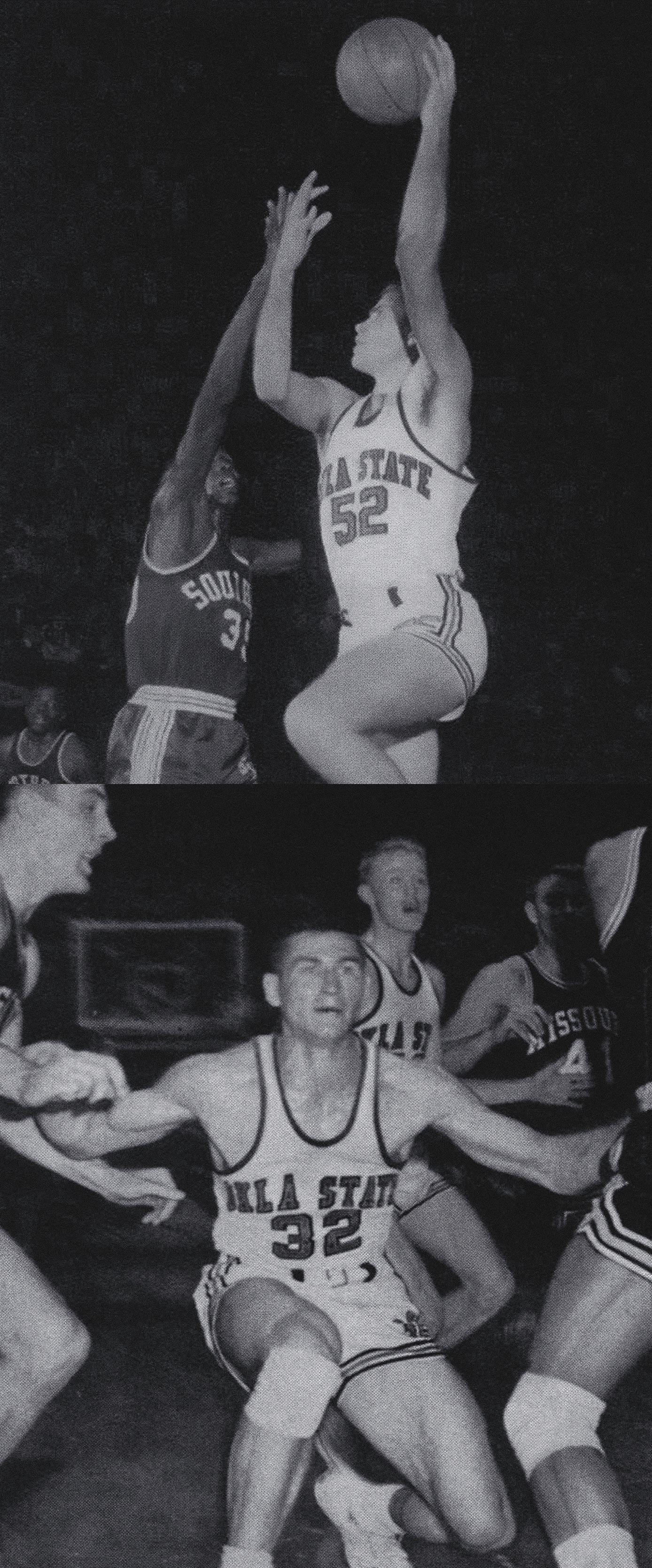

Arlen Clark is a legendary name in the history of Cowboy Basketball. He was one of the most productive big men during Mr. Iba’s long tenure, and he still ranks as one of the best free throw shooters in the history of college basketball, holding a national record with his 24-for-24 game at the line.

Each year, the Hall of Honor night brings the emotion, as inductees at times are both overwhelmed and humbled by their selection but also grateful for those family members, youth and high school coaches, and teachers who helped them along the way.

One of the more emotional inductions in recent history took place this year when Cowboy All-America receiver Hart Lee Dykes took his place among the greatest student-athletes in Oklahoma State history. He had multiple OSU teammates looking on, including Barry Sanders

Dykes, a former national high school football player of the year, lived up to the hype in four glorious seasons as part of two of the greatest o enses in school history.

The football program went through some tough times on the heels of Dykes’ (and others’) recruitment. But as master of ceremonies Larry Reece said on induction night, those mistakes were not made by the 17-year-old prospects, they were made by the grownups.

For six former recruits turned studentathletes-turned legends, the circle was complete when the 2025 class joined the hall. And next year we will have the honor and pleasure of another emotional celebration on the old hardwood of Gallagher-Iba Arena with the induction of the 2026 class.

In an era in which one ever knows what tomorrow will bring, it sure is fun looking back

E RIC MORRIS TAKES THE REINS OF C OW BOY F OOTBALL

COWBOY BASEBALL’S AIDAN MEOLA BATTLES BACK ONCE AGAIN

HOW OSU’S SPIRIT SQUAD SERVES AS AMBASSADORS

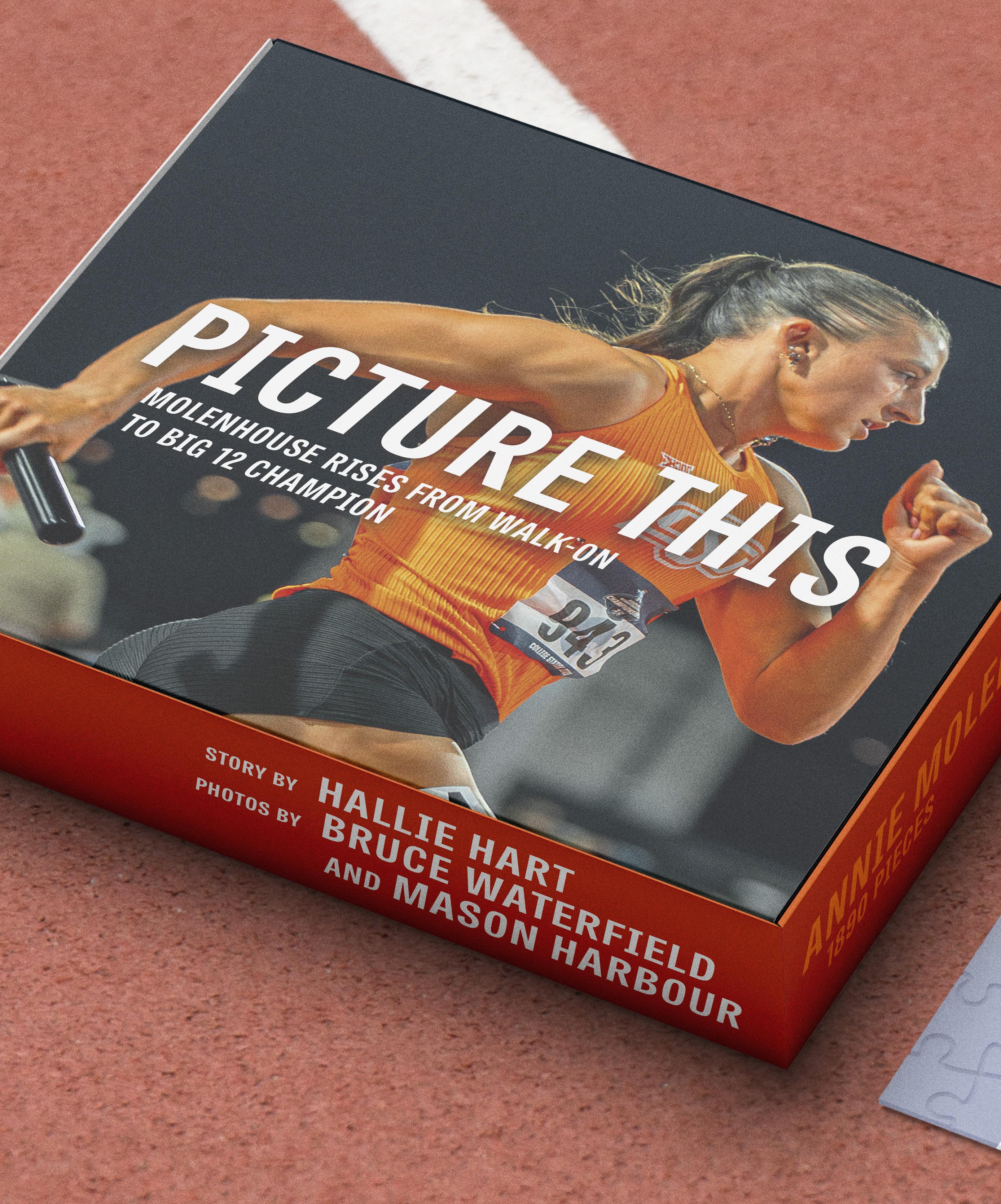

ANNIE MOLENHOUSE PUTS ALL THE PIECES TOGETHER

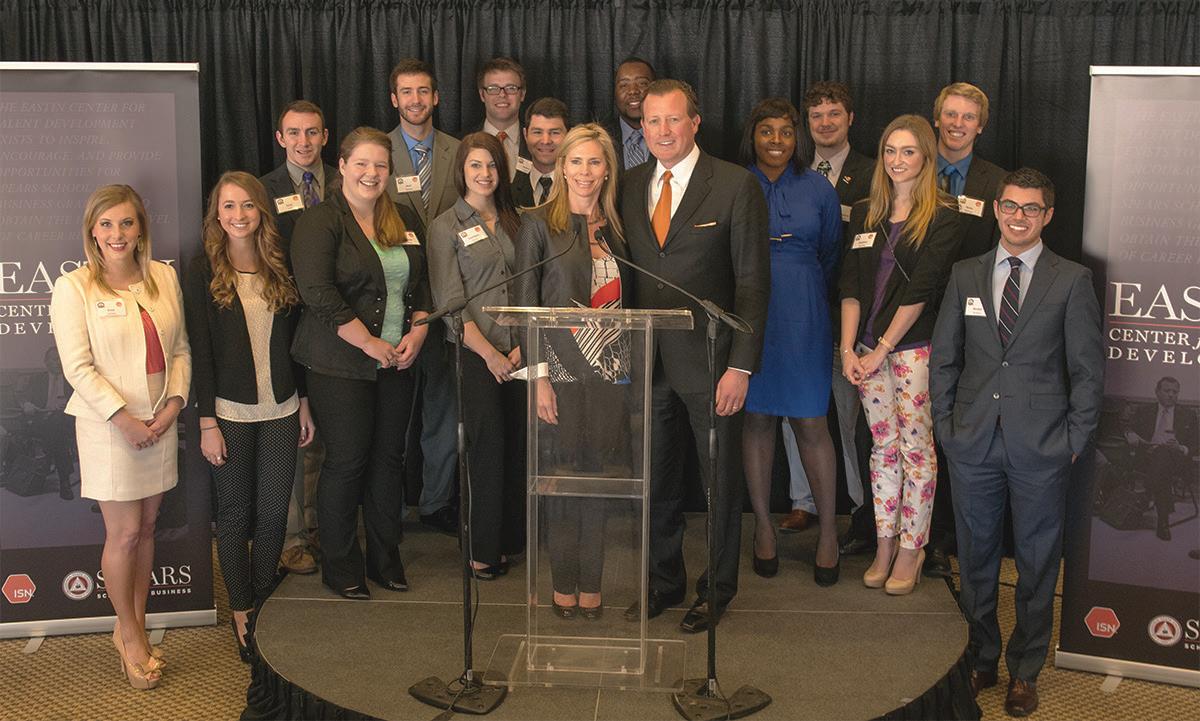

JOE EASTIN’S GREATEST STRENGTH IS BUILDING LASTING CONNECTIONS

Cowgirl captain Ellie DuPuis rode "Squid" to victory in the Fences competition as OSU notched a 13-6 win over Baylor at the Pedigo-Hull Equestrian Center.

POSSE Magazine Sta

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF / SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR KEVIN KLINTWORTH

SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR JESSE MARTIN

ART DIRECTOR / DESIGNER JORDAN SMITH

PHOTOGRAPHER / PRODUCTION ASSISTANT BRUCE WATERFIELD

ASSISTANT EDITOR CLAY BILLMAN

CONTRIBUTING PHOTOGRAPHERS DYLAN BAISDEN, NICK CHURCH, RAINE FARRAR, DEVIN FLORES, KYLIE GRANDELL, MASON HARBOUR, KATE HODGES, ROD HILL, MACKENZIE JANISH, RACHEL MCELYA, ERIC PRIDDY, PHIL SHOCKLEY, COLE WEIBERG

CONTRIBUTING WRITERS CLAY BILLMAN, HALLIE HART, GENE JOHNSON, KEVIN KLINTWORTH, WADE MCWHORTER, TYLER WALDREP

Development (POSSE) Sta

ASSOCIATE AD / ANNUAL GIVING ELLEN AYRES

PUBLICATIONS COORDINATOR CLAY BILLMAN

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT BRAKSTON BROCK

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT MATT GRANTHAM

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT DANIEL HEFLIN

SENIOR ASSOCIATE AD / EXTERNAL AFFAIRS JESSE MARTIN

SENIOR ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT LARRY REECE

ASSOCIATE AD / DEVELOPMENT SHAWN TAYLOR

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR OF ANNUAL GIVING ADDISON UFKES

ATHLETICS PROJECT MANAGER JEANA WALLER

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR / DONOR BENEFITS MORGYN WYNNE

OSU POSSE

102 ATHLETICS CENTER STILLWATER, OK 74078-5070

405.744.7301 P 405.744.9084 F OKSTATE.COM/POSSE POSSE@OKSTATE.EDU

ADVERTISING 405.744.7301

EDITORIAL 405.744.1706

At Oklahoma State University, compliance with NCAA, Big 12 and institutional rules is of the utmost importance. As a supporter of OSU, please remember that maintaining the integrity of the University and the Athletic Department is your first responsibility. As a donor, and therefore booster of OSU, NCAA rules apply to you. If you have any questions, feel free to call the OSU O ce of Athletic Compliance at 405-744-7862 Additional information can also be found by clicking on the Compliance tab of the Athletic Department web-site at okstate.com

Remember to always “Ask Before You Act.”

Respectfully,

BEN DYSON

SENIOR ASSOCIATE ATHLETIC DIRECTOR FOR COMPLIANCE

Know a student ready to rise? OSU’s scholarship opportunities fuel the fire of future Cowboys. By walking the Cowboy way, our students dare to think bigger and build what’s next, forging their character, passion and grit to achieve excellence.

For maximum scholarship consideration, encourage the high school senior you know to apply by Feb. 1.

Members of the Oklahoma State men's cross country team celebrate their decisive victory at the 2025 NCAA Cross Country Championships, held Nov. 22 at the Gans Creek course in Columbia, Mo. Running the 10K circuit in soggy, cool conditions, the Cowboys saw all five scorers finish as All-Americans (top 40 overall), including three scorers in the top six. The Pokes finished with a total of 57 points, defeating third-ranked New Mexico by 25 points and second-ranked Iowa State by 101 points. The title is the fifth under Director of Track & Field and Cross Country Dave Smith and the sixth overall for the storied program.

Two-time Biletniko winner and unanimous All-America selection Justin Blackmon was enshrined in the Boone Pickens Stadium Ring of Honor at halftime of the Kansas State game on Nov. 15. Blackmon was joined on the field by fellow Ring of Honor member Terry Miller and Athletic Director Chad Weiberg, along with family members. The Ardmore, Okla., native was unquestionably the best receiver in America in both 2010 and 2011. He finished his Cowboy career with 253 receptions for 3,564 receiving yards and 42 touchdowns.

Alignment. Fit. Our kind of people.

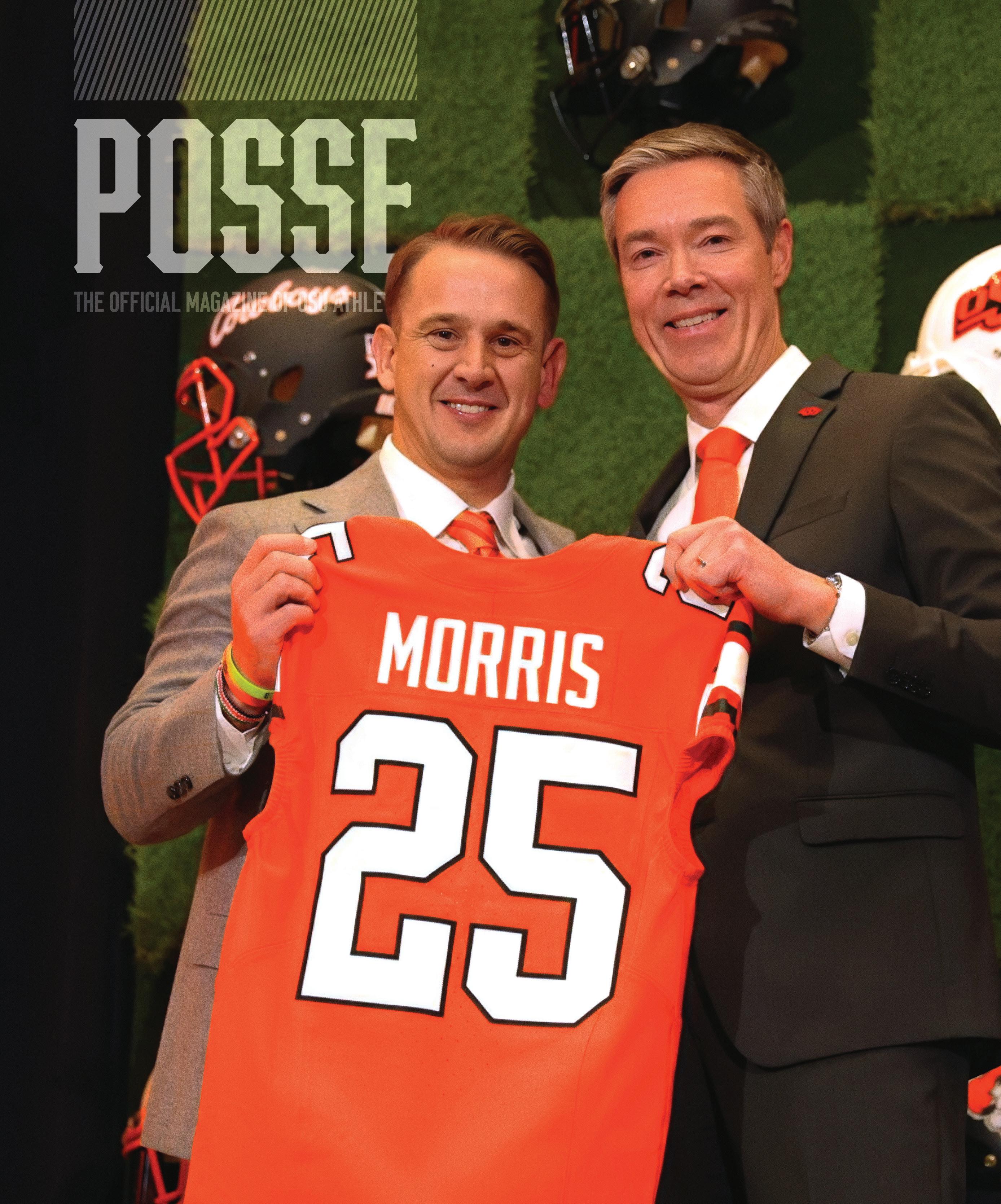

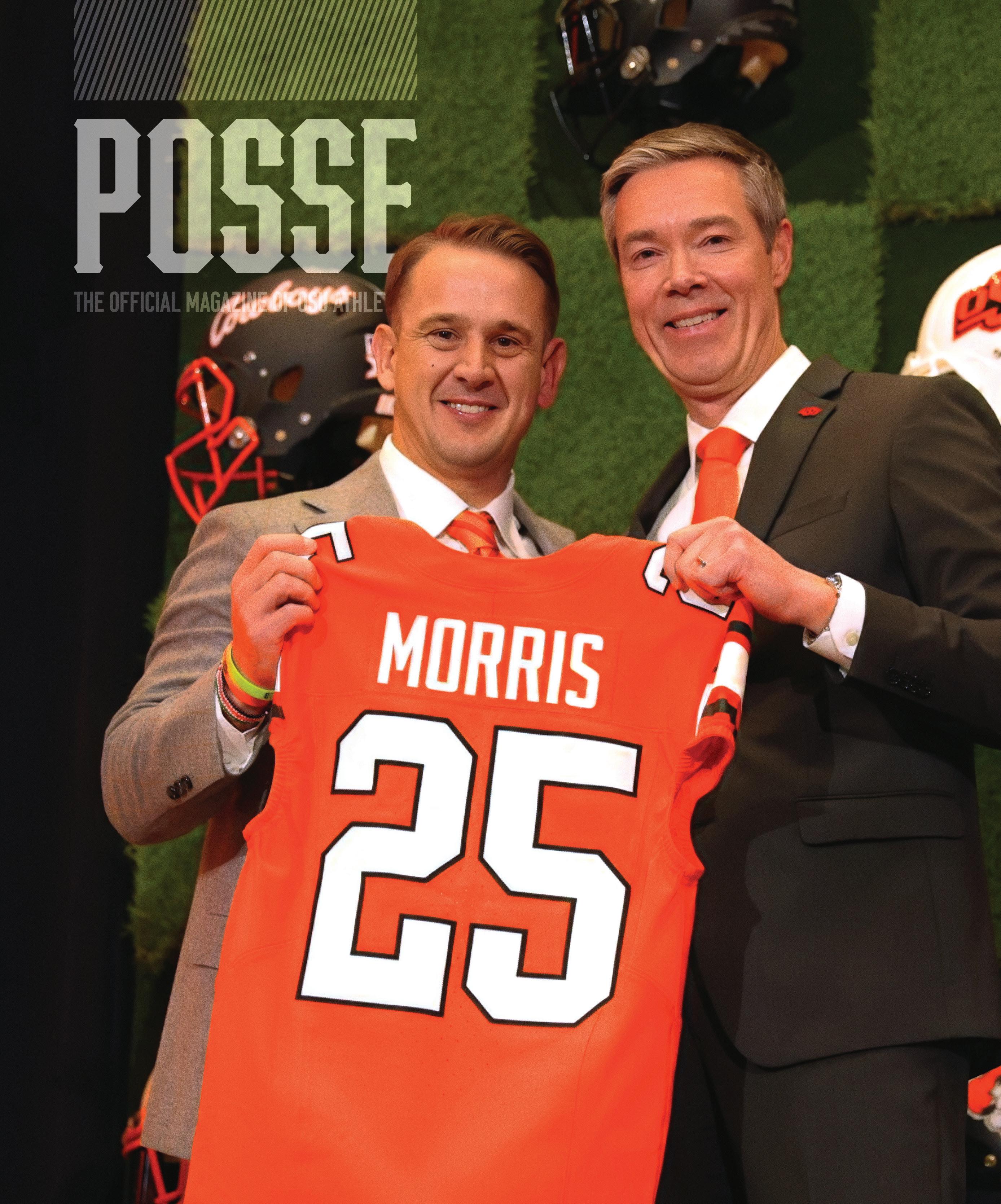

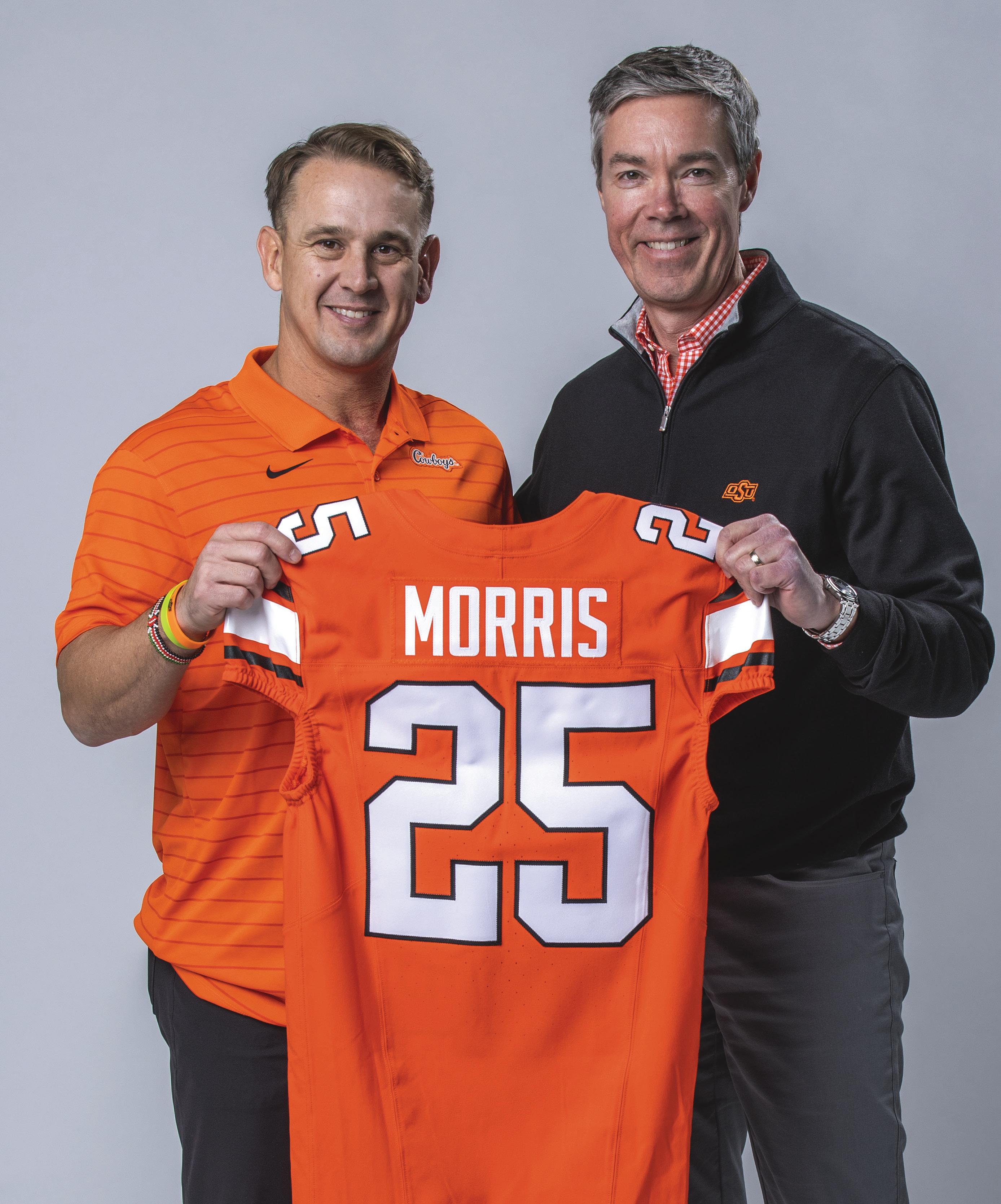

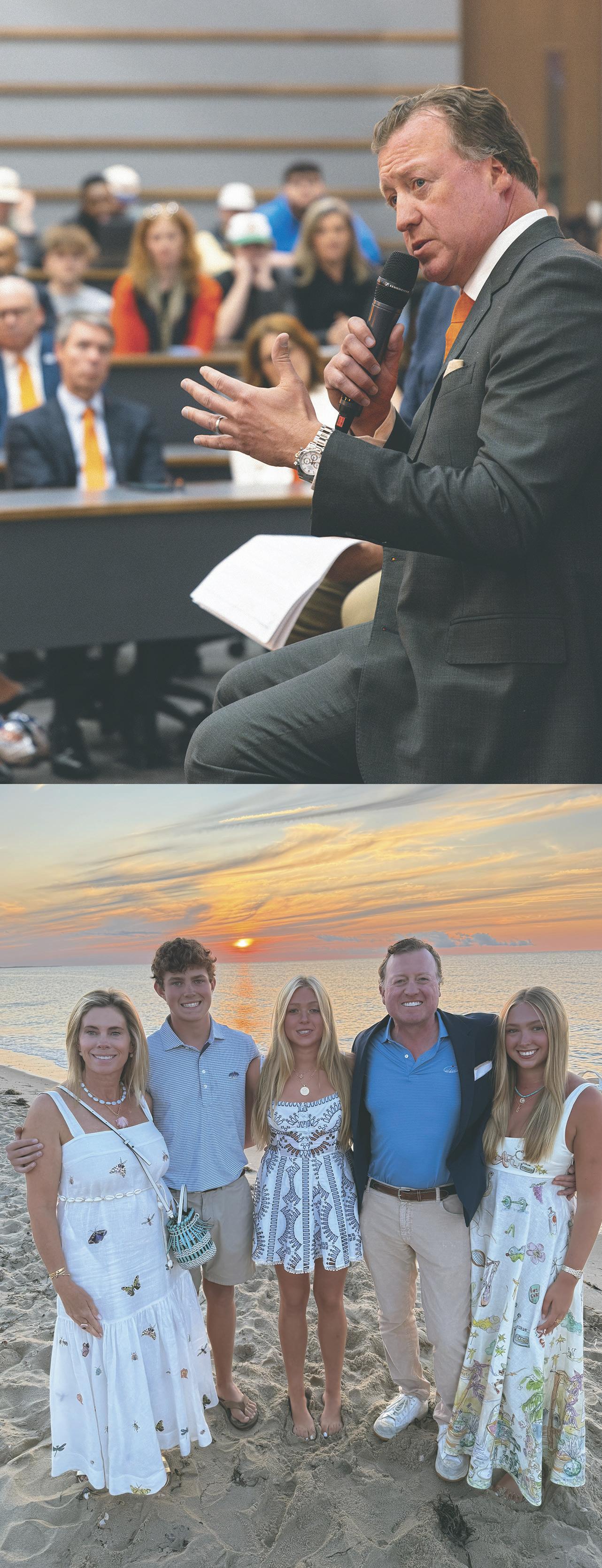

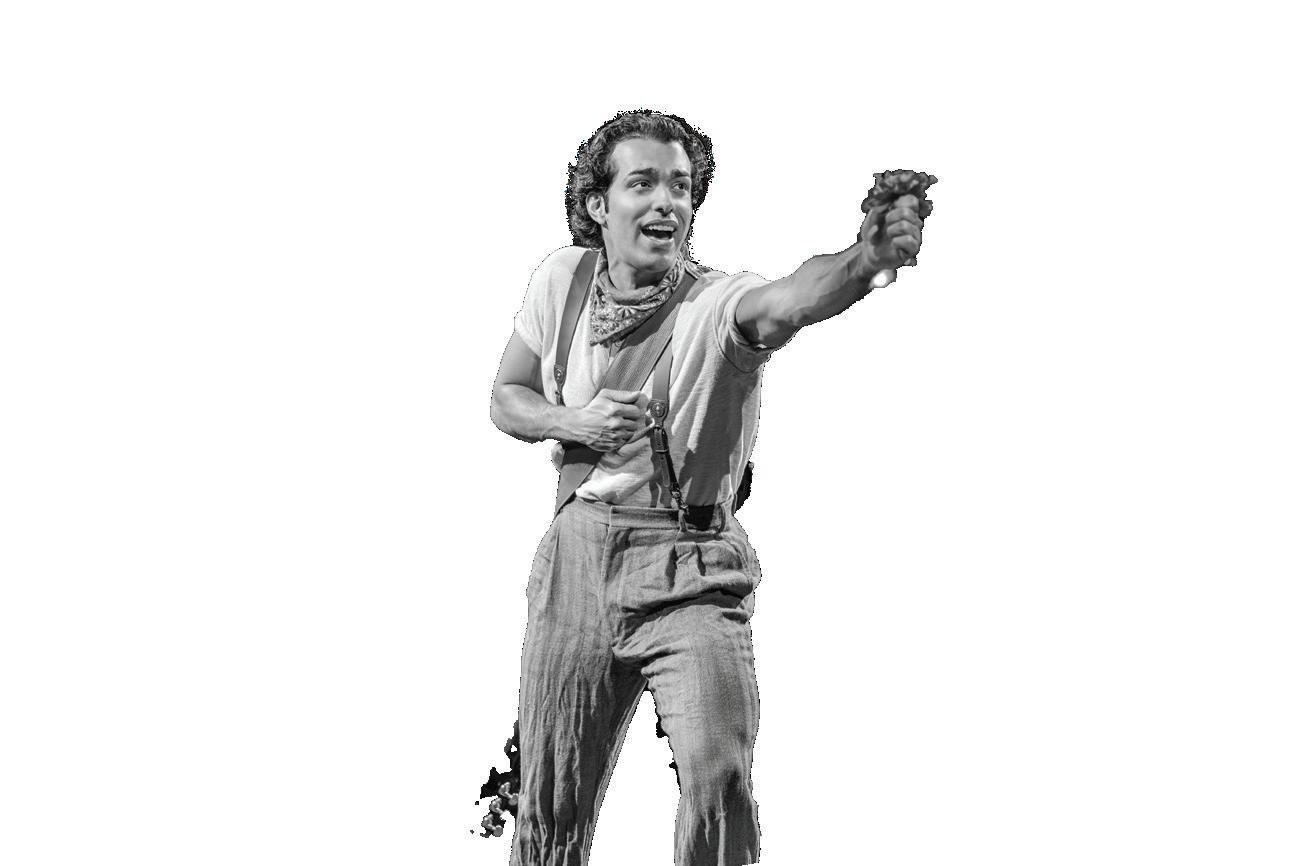

No matter how you phrase it, the meaning is clear. The announcement of Eric Morris as the 25th head football coach in Oklahoma State history seems to be the melding of two parties destined to find each other at some point in time. Morris, the person and coach, and Cowboy Football are just too much alike to be apart.

They align.

“We had a lot of good coaches who showed a strong interest in our football job,” said Athletic Director Chad Weiberg of OSU’s first legitimate football coaching search since the hiring of Les Miles. “What set Eric apart was the combination of his experience and the fit.”

Weiberg’s philosophy is valid and important. There is an old story that still floats around OSU Athletics about a new coach being hired. Upon accepting the job, this particular coach told the then-athletic director he and his family would like to live in Edmond for various reasons.

The old story happens to be true. The response from OSU was, naturally, how do you recruit someone to live in Stillwater when you don’t?

Stillwater is considered a small college town by most standards. Morris is from the even smaller Texas municipality of Shallowater (population 2,964), just northwest of Lubbock.

Call it the first sign of synchronization.

“Stillwater is the kind of place we want to raise our children,” he said repeatedly during a full day of media opportunities in December. “This is like a dream come true. We want to embrace ourselves in this community. My kids will be going to Stillwater Public Schools. It is something we believe in. My father was a public educator.

“We believe in small-town people. I’ve already had people reach out to me from the community, from the school system, already trying to help us out and make sure this transition is seamless for me and my family.”

The small-town belief system is also bolstered by the fact that the head coach’s wife, Maggie, is from Rector, Arkansas (population 1,977). Shallowater just happens to be six hours west of Stillwater. Six hours to the east of Stillwater is Rector.

It seems to be an interesting coincidence at the very least.

On the December Monday when Morris was o cially introduced to an overflow orange-saturated crowd at the ConocoPhillips OSU Alumni Center, he navigated his way through hours of interviews, handshakes, stranger- hugging and photo taking. At the end of that very long day, the new Cowboy coach had one simple request. He asked if he could trade his university-provided high-end luxury vehicle for a truck.

Now that seems like a fit.

Morris was a walk-on turned star receiver for Mike Leach at Texas Tech. He was still kicking around Lubbock as Kli Kingsbury’s o ensive coordinator when Weiberg served as Tech’s deputy AD. And while the crossing of paths at Tech may not have played a big role in Morris landing the job at OSU, it did provide Weiberg with a point of reference when he began looking for Mike Gundy’s replacement.

“The person we were talking to during our search was the same person I knew at Tech,” Weiberg said. “We weren’t seeing someone ‘perform’ during an interview. He was being himself — the person I knew him to be.”

Regardless of where the seed was planted, Morris was never terribly far down the deep list of coaching candidates for the OSU position based on his track record as a program builder, quarterback guru, o ensive thinker and family man.

“We talked to more than 15 coaches during the process, Weiberg said. “We had the luxury of time in this search and used it to thoroughly vet many potential candidates. We made a lot of calls, and we took a lot of calls. Coaches we thought we might have to make a pitch to regarding Oklahoma State, wound up making a pitch to us.

“But it is fair to say that Eric was at or very near the top of the list right from the start, and he stayed there throughout the process.”

OSU President Jim Hess called it the most dramafree search in college football, and in a year in which the air was thick with drama, the OSU process was seamless. During coaching searches Weiberg runs what he likes to call high-integrity searches. The translation to layman’s terms is don’t expect a lot of leaks during the process.

How buttoned-downed and streamlined was the OSU search? By the time Morris was o cially announced as OSU’s hire on Nov. 25, the school and Morris had already signed a contract several days earlier. And while rumors swirled around the country, with Morris linked to multiple jobs, things in Oklahoma had already moved from search mode to transition chores.

“Eric let us know very early in the process that he thought Oklahoma State was a particularly good fit for him and his family,” Weiberg said. “As you heard in his introduction, the Big 12 Conference is the league he was raised on. The negotiation with Eric and his agent was very professional and straightforward.

Seems Dr. Hess summed it up just right.

This is like a dream come true. We want to embrace ourselves in this community.” “ — ERIC MORRIS

For many reasons, including the kind of person he is and the lasting relationships he builds with his players, Coach Morris is the perfect fit as the next leader of Cowboy Football.” “

— CHAD WEIBERG

During the introduction of Eric Morris, the energy level in Click Hall was palpable as the OSU faithful seemed to quickly turn the page from what had been a tough two-year run on the heels of two decades of unprecedented success for the football program.

“I really don’t remember a time when our fan base has been more unified in their excitement for a head coaching hire,” said Larry Reece, OSU’s senior associate athletic director for development and the athletic department’s chief fundraiser. “I was still a student when we hired Eddie Sutton, but I think the Coach Morris hire is in that ballpark when you talk about igniting the fan base.”

The reasons for the interest are, of course, numerous. Aside from his familiarity with the Big 12 Conference, and OSU specifically, Morris has a proven track record of results.

“When you win at di erent levels, it shows me you are a problem solver,” Weiberg said in reference to the Morris building jobs at Incarnate Word and North Texas. “He never seemed concerned about what he didn’t have or what other people did have or what he was up against. And as he told the media, he especially likes being doubted. He likes rising to a challenge, and he likes proving people wrong.”

As a player at Texas Tech, Morris spent a year convincing Mike Leach to put him on scholarship. He then spent the rest of his career making Leach look good. His Red Raider career included nearly 2,000 career receiving yards, and he was a big part of some of the NCAA’s most prolific o enses.

His position coaches as a student-athlete were former OSU o ensive coordinator Dana Holgorsen, current Southern California head coach Lincoln Riley and current TCU coach Sonny Dykes, among others.

His first head coaching job came at Incarnate Word, an FCS school in San Antonio that did not even have mouthguards for its student-athletes when he arrived. (For those who may not know, mouthguards are used to keep teams from playing games with student-athletes who have no teeth remaining in their head.)

The year before Morris arrived at the San Antonio school, Incarnate Word won just one game. His first year as head coach the Cardinals went 6-5. His last team there won 10 games and advanced to the second round of the FCS playo s.

After a stint as o ensive coordinator at Washington State as part of a Mike Leach sta , Morris began another rebuild, this time in Denton.

The 2025 Mean Green, his third squad in Denton, reached the Associated Press top 25 for the first time since 1959 in what may have been the greatest season in North Texas history.

The landmark accomplishments, the fact that he has coached and developed the likes of Patrick Mahomes, Baker Mayfield and Cam Ward, likely makes Morris the most accomplished coach to ever accept the Oklahoma State position. He is the first sitting head coach hired by Oklahoma State since 1969 when Floyd Gass was hired from Austin College.

The short-term to-do list is immense. The new normal for college football means that first-year coaches not only have to fill out a primary sta of 10, but also the ever-growing support areas. At OSU that number at times has been north of 45 employees when including administrative help, recruiting sta and analysts, and o ensive and defensive analysts.

Then comes that pesky roster. Today’s college football culture means unrestricted, unregulated and unrehearsed free agency. Meteorologists are more accurate predicting the weather than anyone could possibly be predicting portal entries.

By rule (or due to a lack of rules), every member of every roster in North America is an unrestricted free agent at all times After putting pen to paper and doing the math, it appears Morris has the challenge of bringing to Stillwater, keeping in Stillwater, or recruiting to Stillwater, approximately 150 people in a relatively short amount of time. Relationships are always important and maybe never more so than now. And that’s good news for Oklahoma State fans.

“He's got a special place in my heart,” Cam Ward told the Tulsa World. Ward played quarterback for Morris at Incarnate Word and Washington State. He finished his career at Miami and was the No. 1 overall pick in the National Football League draft, being selected by the Tennessee Titans. Morris and his oldest son, Jack, were in the NFL green room on draft night with Ward.

On the day that Morris was introduced at OSU, he spent the evening in Fayetteville, Ark., as another one of his quarterbacks was named the best walk-on in the country.

If relationships matter at all, Oklahoma State is in good hands with Eric Morris.

He is our kind of people.

U.S. Navy Rear Admiral Gregory Slavonic, a 1971 OSU grad, led the crowd in the "Orange Power" chant prior to kicko versus Kansas State on Nov. 15. He served as Acting Under Secretary of the Navy as part of a distinguished 34-year career. Slavonic was one of four veteran "OP VIPs" recognized for their recent induction into the Oklahoma Military Heritage Foundation, including Major General Walter Starks, a decorated World War II veteran and Stillwater civic leader, represented by his daughter, Pam Schwenk ; Major Helen Holmes, the first Oklahoman in the Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps, represented by her son, William Holmes; and Major General Stephen Cortright , a Vietnam combat pilot and former Adjutant General of Oklahoma.

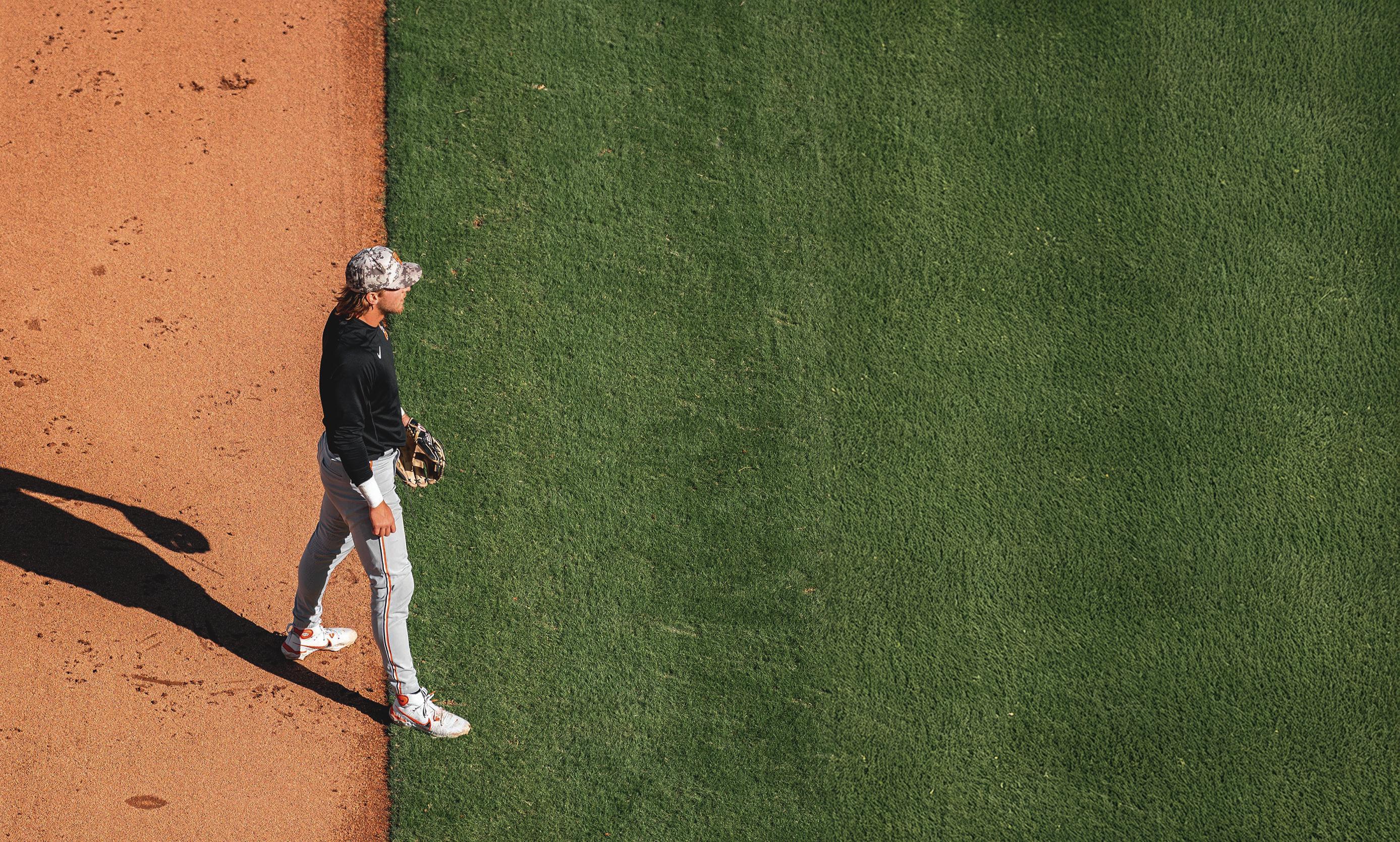

On a crisp fall afternoon at O’Brate Stadium, Aidan Meola stood at the hot corner fielding ground balls and grooving to the music blaring from the speakers when he suddenly cracked a smile and shouted across the diamond, “Bruegge (Colin Brueggemann), this is way better than having a real job!”

Truth is, Meola figured at this point in his life, he’d be a year or two into a professional baseball career.

But life, pun intended, has a funny way of throwing you curveballs. For Meola, it’s been an onslaught of curveballs since he arrived in Stillwater four years ago.

Instead of trying to make a name for himself in the minor leagues, Meola is a rarity these days — a college athlete in his fifth season in a program, the only program he’s ever been a part of.

His is a story of resilience and perseverance and an attitude that has remained positive and kept him going along the way.

“Aidan has grown into a guy that’s been able to look forward and overcome things, and he’s developed a lot of toughness along the way,” said OSU head coach Josh Holliday. “I think those are things he already had, but definitely things he had to tap into.

“He’s going to walk out of here as an Oklahoma State graduate. He’s going to walk out of here as a player who has a unique place in history, having five true seasons on this campus in this uniform. That’s just a rare, rare club. And he’s been a part of a lot of winning, a lot of great teammates. And I think he would probably tell you that, despite some of the ups and downs, he’s had a whole lot more positive things that he’s been able to take with him.”

Meola has always been an athlete. But baseball wasn’t always his first choice of sport — that would be soccer.

But that’s something to be expected when your dad is one of the most accomplished and decorated players in American soccer history.

Tony Meola, Aidan’s father, represented the United States Men’s National Team at three World Cups (1990, 1994 and 2002). He was an award-winning goalkeeper in Major League Soccer and was inducted into the National Soccer Hall of Fame in 2012.

Although Aidan was still quite young as his dad’s playing career wound down, it still made an impression on him.

“I remember always being in the locker room and growing up there,” Meola said. “I remember his days with the New York Red Bulls pretty well. For whatever reason, I remember being in that locker room a ton and going to that stadium to watch games.

Growing up in New Jersey, Aidan dreamed of following in his dad’s footsteps.

“I wanted to be a soccer player, and that was it. That was my favorite sport, and that’s what I wanted to play just because I grew up around it,” Meola said. “I thought I was going to play soccer up until high school, then when I got to high school I kind of realized that baseball was maybe going to be a better path.”

The reason for the change? The Meolas moved from New Jersey to Florida following Aidan’s sophomore year of high school. Instead of maintaining his status as a multi-sport athlete — soccer in the fall, basketball in the winter and baseball in the spring — he zeroed in on one.

“When I moved to Florida, I could finally play baseball year-round. So once I started training and getting after it all year baseball-wise, I think that’s when it kind of flipped that that’s what I wanted to do,” Meola said. “I just liked it the most, and I was probably the best at that out of the three, so that’s what I went with.

“Was it hard to give up soccer? Yeah, it was. But it was a little easier when I moved and it was 70 degrees all the time, and I could be outside and play baseball all year.

“But yeah, I still miss it. Soccer was really, really fun for me.”

As fate would have it, that move to Florida also played a pivotal role in Meola becoming a Cowboy.

One of Meola’s hitting mentors knew Matt Holliday and sent the former Major League Baseball star and then OSU volunteer assistant coach video of Aidan. That interaction sparked a budding friendship between Aidan, Matt and Matt’s son, Jackson, another aspiring teenaged baseball star.

The Hollidays convinced Aidan to take a recruiting trip to Stillwater — and the rest, as they say, is history.

At that time, the Cowboys still played in historic Allie P. Reynolds Stadium, but O’Brate Stadium was under construction. The vision of playing there, with Jackson as a teammate, was alluring, and Meola also quickly formed a bond with the OSU coaching sta .

“Just seeing the new stadium, and then it was just a real family feel, kind of felt like home, even though it’s not what I was used to scenery-wise,” Meola said. “I lived right by the beach in New Jersey and on the beach in Florida, so it was a little bit of a culture shock when I got here.

“But I learned to love it pretty fast — it kind of grew on me.”

So fast, in fact, that Meola committed to the Cowboys before leaving town.

“It was the first of five consecutive scheduled (college) visits that I had, but I cancelled all my other visits.”

Aidan is loyal to this program. He’s been loyal to his teammates. He’s been loyal to the people. And I think that’s because he has felt a lot of love coming back towards him.” “

Meola returned to the Oklahoma State campus as a freshman in the fall of 2021 ready to make a name for himself in the Cowboys’ lineup.

“He was already very strong and athletic and had the potential to be an even more athletic, powerful infielder with size, which is hard to find,” Holliday said. “The combination of his competitive makeup, his athletic background and already having good size — he was kind of your ideally built third baseman A really good profile, and he was already doing a lot of good things.”

Meola delivered a pinch-hit, two-RBI single in his first collegiate at-bat and drove in a run in his first start against Oklahoma in late March.

Then came a freak batting cage accident, with a baseball striking Meola in the head, leaving him with a concussion. It was actually his second concussion since arriving in Stillwater — he had su ered one during fall practice — and one of four times he was placed in concussion protocol during his freshman year.

Those injuries limited Meola to just 28 games that first season. But along with his early success, he showcased a penchant for clutch hitting when he returned to action late in the year and smacked a go-ahead, two-RBI single in the top of the 10th inning against Arkansas to help send the Pokes to the

NCAA Regional final.

Poised for a breakout sophomore season, Meola established himself as OSU’s starter at the hot corner over the first month of the 2023 season and was hitting .321 with 16 RBIs over his first 20 games.

But then the injury bug bit again as he tore two ligaments in his thumb during an at-bat, forcing surgery and putting him on the shelf for seven weeks.

Once again, Meola battled back and had a highlight moment, cranking a walk-o solo home run with one out in the ninth inning against Texas Tech to send OSU into the Big 12 Championship final

Meola consistently showed what he could do as a junior, playing in 43 games and earning All-Big 12 honorable mention status by hitting .329 with 10 home runs and 47 RBIs.

However, despite that success, the season was somewhat marred by injury as Meola admits he was never at full strength.

“I was healthy for the first two weeks, then had my first hamstring strain, and that nagged me the whole year,” Meola said.

“It ended up happening four or five times. By the end of the season, in the regional, I was basically playing on one leg and my hamstring was about torn. I didn’t practice all week, didn’t touch a ball, just played.”

Not only did he play, he performed at an elite level, hitting safely in all three games he played and batting .556 (5-for-9) with two doubles, a home run and five RBIs.

That set the stage for a senior season showcasing Meola as a centerpiece of the Cowboys’ lineup, and he entered the year “feeling great — my body felt the best it ever had.”

This time, it would take 13 games for disaster to strike — on March 7, Meola tore his labrum on a swing in a game against Illinois State.

Senior season over, and surgery a month later.

In an avalanche of injuries, that one nearly broke him, Meola admits.

“I was good until last year, but that one hit me really hard, especially because it was my senior year,” Meola said. “I had chosen to come back here for my senior year because I felt like I wanted to get a fully healthy year in and prove to people what I could do. And I turned down some pro opportunities after my junior year.

“So that one, that one hurt. And after that, there was a two- or three-week period where I was going to quit and be done because I just said to myself, ‘You work so hard and do this every day for the last however many years of your life, and it kind of just keeps beating you down.’

“I talked to Josh (Holliday) — I didn’t tell him I was thinking about being done, but I talked to my parents about it, my brother, my sister, some of my friends. They were all just like, the worst that can come out of this is you go back and you impact your teammates, whether you’re healthy or not. You could still be a good teammate, and you could still lead by example.

“And best-case scenario is you have a healthy year, and you go win a national championship at Oklahoma State, which is what I’ve wanted to do since I stepped on campus here. So once you kind of put it in perspective and realize that, that’s kind of where it flipped, where it’s like some good, or potentially a lot of good, can still come out of this.”

Once Meola decided to stick with the sport he loves and return to the Cowboys for the 2026 season, he showcased a commitment level that impressed his head coach.

“The resolve and quickness with which he shifted his focus to coming back this year and then the clarity with which he committed to being here for his fifth year and the way he spoke about it, I saw in him a very mature guy that learned to shift his focus immediately,” Holliday said. “He saw himself here in his fifth year, embraced the surgery, kicked the rehab circuit hard and got healthy. The way he shifted gears, the way he understood it as just another obstacle, he handled it like a very mature person

“A lot of adults don't handle adversity well, so I wouldn’t say he handled it like an adult. I would say he handled it like

“

All I can do is build my body up, become as strong as I can and put myself in a great spot to succeed.”

— AIDAN MEOLA

just a very mature person. I don’t think there will be much of anything he encounters moving forward that he doesn’t have a game plan of how he’s going to overcome it. And that probably is the one thing that sticks out most to me, is just watching him deal with the disappointment of a year ago — the personal disappointment, the team disappointment and just overall disappointment for everyone involved — but then how well he handled it gave everybody else a sense of positivity. He turned a negative into a positive, and that’s just a great sign of maturity and perspective that he’s gained.”

For those inside the Cowboy Baseball program, it has been impressive to see the impact Meola has delivered the past four years, despite the rash of injuries that have kept him o the field more often than not.

His positive presence as a leader in the clubhouse and the dugout has never wavered, and even with the season-ending injury in 2025, he continued to make road trips and contribute in any way he could.

“I’m all about my teammates and all about winning, all about playing the right way,” Meola said. “I’ve kind of been a leader my whole life just naturally, I’ve never really had to force it. And if I’m not that way, I won’t play well. Like if I’m worried about me and only worried about me, I will not play a good brand of baseball. So I’m focused on the team and doing what it takes to win, whether I’m on the field or not, that’s the best version of me.

“So selfishly that’s another reason I do it. But it makes me feel good when I feel like I’m helping others or just doing what the team needs and doing whatever it takes to win.”

That mentality isn’t lost on his teammates.

“He’s definitely faced a lot of adversity with surgeries and concussions and stu like that, but it’s been really cool the way he’s handled it and found a way to persevere through every situation,” said OSU pitcher Drew Blake, who joined the program with Meola in 2022. “Even when he’s been hurt, he’s been a great resource for our team just by being a good teammate and a good, coachable person

“He really cares about Oklahoma State Baseball, and he’s a winner. And he’s definitely grown a bunch personally through all those experiences.”

Meola reflects back to his days growing up with a father who was a professional athlete as a big reason he has been able to maintain that positive presence in the face of adversity.

“He was hard on us when we were young, and I’m really glad that he was because I didn’t turn out soft. And I think if he wasn’t, I probably would have turned out soft,” Meola said. “I saw how other parents treated their kids, and they did turn out soft. So, yeah, he was hard on us when we were young, but it was always

about the right stu , like being a good teammate, don’t throw your stu when you get out, have a good attitude, play the game the right way whether you’re doing good or bad.

“Life lessons and little things like that, how you carry yourself, is where it really pays o having a dad that was an athlete at a high level.

“The biggest takeaway for me in my whole life has always been ‘Control what you can control.’ Stu like injuries happens — it sucks, but it happens. All I can do is build my body up, become as strong as I can and put myself in a great spot to succeed.”

Holliday echoes those sentiments.

“Aidan has tremendous parents; Colleen and Tony are awesome people. A lot of his perspective about the team and cheering for others and being a leader comes from the way they raised him and the life lessons that he learned from watching his dad be a famous world-class athlete and a mom who has amazing perspective herself,” Holliday said.

“Aidan’s a positive verbal leader, which is unique. It’s a cool thing nowadays to be quiet and shy, but that’s not real powerful in a field of play. Positive verbal leadership is a very valuable piece of a team sport, and he’s always done that since the day he got here. There’s been a lot of guys that have received a positive compliment from him over the last five years that I guarantee has brightened their day and made them feel more included and supported and believed in. I don’t think you can underestimate the value of that.”

Through all the ups and downs in his OSU career, another thing that sticks out about Meola is his devotion to the Cowboys and Oklahoma State University.

He is the epitome of Loyal & True

In a day and age in which leaving for supposedly greener pastures or looking for a fresh start somewhere else is in vogue, Meola has never wavered, never even considered the notion of not being a Poke.

And a big part of that stems from the family culture Holliday and his sta have created in Stillwater.

“Guys are leaving every year, and I know guys who have been to five di erent schools in five years or four di erent schools in four years,” Meola said. “But the way that this coaching sta has been with me, through all my injuries, they’ve stuck with me. I think part of it is because I do the right thing. But I know for a fact that you cannot find that everywhere, especially with how many things I’ve gone through.

“Josh and (Mark Ginther) and every coach I’ve ever had here, have been on my side and have never flipped when stu

has gone bad for me. That’s where my loyalty comes from. I love this university, and I’ve put so much into it that going somewhere else never has even been an option or crossed my mind.”

That makes Meola an easy player to root for in his final season, one that hopefully will provide Cowboy fans with a full season of a healthy and successful Aidan Meola — because if anybody deserves it, it’s him.

“Aidan is loyal to this program. He’s been loyal to his teammates. He’s been loyal to the people. And I think that’s because he has felt a lot of love coming back towards him,” Holliday said. “He knows the people here care about him. But it’s a two-way street. He cares and puts a lot in, and he gets that back from his people.

“And that’s the joy in coaching. Being a player, he’s going to have an alma mater. He’s going to have a place to go back to. He’s going to have five years of teammates and friendships and people that are going to be there for him forever.

“He should be celebrated. He should be celebrated as an athlete who stays true to their school, works their tail o towards graduation, leads their team, represents the school in a very classy fashion. When someone comes to Stillwater and lays five years down, it’s a pretty substantial investment by the athlete into the school. And I think there’s something that we all can really, really say to him.

“Thank you.”

Former teammates Barry Sanders and Hart Lee Dykes shared laughter and stories at a special POSSE VIP reception Sept. 26, prior to Dykes' induction into the OSU Athletics Hall of Honor. Emceed by Larry Reece, the event included remarks from former wide receivers coach Houston Nutt . As two-thirds of the famous "Triplets" (along with quarterback Mike Gundy), Dykes and Sanders made opposing defenses "pick their poison" to try and stop the Pokes. The 1988 Cowboys featured the nation's most exciting o ense, averaging 48.7 points and 530.4 yards of total o ense per game en route to a 10-2 record.

When Brayden Smith steps foot inside Gallagher-Iba Arena wearing the Pistol Pete head, he’s quickly barraged with cheers from some of his biggest and youngest fans.

“You’re cheering on the team, but at the same time, you know you’re putting smiles on everyone’s face,” Smith, a quantitative finance grad student from Altus, said. “And to me, that’s priceless.”

Smith said there are several children ranging in ages from 5-12 who are regulars at basketball games and wrestling duals. Many of them cheer for “Orange Pete” in reference to the orange bandana he wears in his back pocket, which sets him apart from his counterpart, who portrays Pistol Pete while wearing a white bandana.

Smith didn’t think those interactions could mean any more to him until last December when he discovered just how much the kids valued their time with “Orange Pete.”

“We do ‘Pic with Pete’ around Christmas time, like pictures with Santa Claus. I was sitting in a chair, and one of them comes up and asks me to stand,” Smith said. “I stand up, and she turns around, looks at the bandana, and then grabs a present from her mom and gives it to me.

“It was like a hot chocolate ball, a picture of me and these kids with me as Pistol Pete, some other goodies, and stu .

But it was just a good experience seeing on the card: ‘To Orange Pete from Peyton.’”

Athletic events are just one opportunity fans have to connect with Oklahoma State’s Spirit Squad (cheerleaders, pom and Pistol Petes).

The three groups collectively log nearly 1,000 volunteer hours annually representing OSU at more than 50 non-game functions. While that time includes Big 12 Media Days for football and basketball, those hours are heavily dominated by opportunities to give back to communities around the city and state.

“I feel like 80 percent of what we do is serve people,” pom member Jaselyn Rossman said, “which is why l love this team so much. It’s so special to us that we get to serve and dance, but they’re both very important.”

Rossman’s favorite use of her platform as a squad member is to give back by serving at the local Night to Shine, a national prom celebrating people with special needs in numerous communities nationwide. The event is sponsored by the Tim Tebow Foundation

Seeing their faces light up whenever they’re walking down the red carpet while we’re all just cheering them — I just love to make them feel special because they are,” Rossman said. “They’re amazing people, and they deserve their own prom.”

Rossman, an accounting major from Sapulpa, said she didn’t realize the impact the pom squad could have on people.

“People just light up, and you feel so cool,” Rossman said. “And (at Night to Shine), the joy on their face is indescribable.”

Pom captain Maggie Middlebrook grew up in Stillwater, so volunteering at the Special Olympics was nothing new for her. Yet, Middlebrook’s preconceptions for the impact she could have were shattered the first time she showed up representing OSU as a pom squad member.

“Being on the pom squad is this whole new platform that I had never experienced before,” Middlebrook said. “And yeah, just the way that people react — I think every time we see a kid and their face lights up because they see us, it’s the coolest experience in the world.”

A Stillwater grad currently pursuing a Master’s in marriage and family therapy, Middlebrook wasn’t the only one who identified the local Special Olympics as one of their favorite days of the year.

The other half of the Pistol Pete duo, Cooper Hamilton, an agribusiness senior from Latta, has volunteered for the games the past two years.

“The second time, it was my fourth event of the day, it was in the middle of the heat. I wasn’t quite looking forward to it as much,” he said. “And then I got out there, and I was like … this is why we do it

“This is why we become Pistol Pete, to give back to the community, to serve a purpose that’s greater than what we could ever dream of and giving back in a way that brings so much joy and happiness to families and kids. It definitely gives you the perspective on how much gets taken for granted. The opportunity to have done this was just so humbling and one that I’ll truly cherish.”

Hamilton said the energy he fed o in that atmosphere, especially from the competitors, was unmatched to anything he’s experienced.

It seems like most of the Spirit Squad members are wired the very same way. Cheerleader Marlie Armatta (a strategic communications senior from Sugar Land, Texas) gets a huge boost when children approach her. Often, they want things signed, which both surprised her and made her nervous initially. She didn’t want to ruin the kids’ stu .

“

Can you handle the weight of representing the university head on, head off?”

— COOPER HAMILTON PISTOL PETE

“A girl said, ‘I really want you to sign my Skechers,’” Armatta said, recounting one of her first autograph signings. “‘I go and practice cartwheels and stu in these shoes all the time. I want to know that a cheerleader signed them.’

“It’s really cool to know that signature means more than a thousand words to that little kid,” added Armatta. “And they’re going to take that and be like, ‘Oh, I want to be like her when I grow up. I’m going to work hard and stu .’ And it’s just really cool to know we are an inspiration to the younger generation.”

While service opportunities keep OSU’s Spirit Squad on the move, even that doesn’t begin to scratch the surface of how cheerleading, pom and Pistol Pete shape the students’ daily lives.

“Freshman year, it was very, very hard,” Middlebrook said. “It was very hard because, especially in our sororities and lives outside of this. I felt like it was a lot harder to build connections with people in those areas because we were spending a lot of time at pom.”

Pom squad members put in at least eight hours each week practicing and participating in mandatory workouts.

Cheerleaders put in a similar amount of time practicing and working out, but their average commitment each week falls somewhere between 10-20 hours due to the addition of voluntary stunt work, which helps prepare them for national competition in the spring.

With winter sports in full swing, the Spirit Squad can reasonably expect to perform at a minimum of two athletic events most weeks if not several more. Middlebrook said it’s not unheard of to have a week with so many home games that the pom squad is forced to start practice after a home basketball game on weeknights.

Those weeks make it even tougher to keep up a social life outside of the team, but Middlebrook said she’s learned how to maintain a connection with her larger support group over the last four years while still prioritizing the group that has given her so many incredible moments in college.

“Every single time that we do anything, or anytime that I put on a uniform, I realize every bit of that is worth it to me,” Middlebrook said. “Because I can be intentional with my friends (who aren’t on pom squad) and invite them to do something else sometime later on.”

The Petes have the hardest schedules to juggle. Between the two of them, they attend more than 500 non-athletic events per year, including birthday parties, weddings — and even funerals — among other functions.

“I’ve done four funerals and will never forget any of them,” Smith said. “First one I did, they brought me in as Pistol Pete beforehand to pray with the family, and then kind of lead them (into the service), and then I sat between the two youngest grandkids during the ceremony.

“And you know that one was one of those where, after you leave, you’re just kind of heartbroken.

“The next one I did was very gut-wrenching. They opened up the doors, bagpipes are blaring, and I walked down the aisle holding a bouquet of orange flowers, set them down on top of the casket, kneeled down for a prayer and then headed back out.”

Smith and Hamilton try to tailor Pete’s appearance to the specific requests, regardless of the event type, but that goes double for funerals. The two really want to ensure that they can o er the family the most support possible in a way that best suits their needs.

“You can still show sympathy, as Cooper, as Brayden, before and after the event. I want to be there, both as Pete and as myself to kind of mourn with them,” Hamilton said.

Unlike many mascots around the country, Pistol Petes are allowed to represent OSU as Pete and without the mascot head as well, if needed or requested.

“It’s not like a business interview,” Hamilton said of the Pistol Pete tryout process. “It’s a character interview, because that’s what is emphasized. Can you handle the weight of representing the university head on, head o ?”

Some days are easier than others, given the number of events that stack up. In October, Smith had a weekend in which he was booked for at least six events, including at least one wedding and a birthday party while Hamilton represented the Cowboys at the football game at Texas Tech.

Smith said his busiest day probably came in May of 2024 when he had a full day in Tulsa that included several graduation parties, one wedding and a birthday party.

Hamilton’s busiest day started at 7 a.m. with a Pistol Pete appearance for a 5K in Oklahoma City and ended at 11 p.m. at a wedding in Tulsa.

A lot goes into representing Oklahoma State University, and life on the Spirit Squad comes with more than its fair share of cool stories — including the Petes’ chance to be in the Nissan Heisman House ad campaign each of the last two years.

While shooting a commercial with Barry Sanders, Tim Tebow and Reggie Bush, the Pistol Petes were on the receiving end of encouragement, for a change.

“They all wanted to give us advice and encouragement to just keep doing what we’re doing. They know Pistol Pete takes a lot of our time and energy,” Hamilton said. “And they were excited to see us as Pistol Pete, because they know how much it takes.

“I’m a huge Tebow fan. That was the guy I was super pumped to meet,” he added. “I listen to his podcast, so I just walked up and said to him, ‘Hey, I just want to let you know you’ve helped me out immensely from all the podcasts.’ And he actually thanked me. That was probably the most rewarding. I’ll never forget that moment … how he was wanting to pour back into the next generation.”

Then, of course, the chance to meet an OSU legend was a reward in its own right.

“This year it was really cool whenever Barry arrived on scene, Smith said. “He made a point to come up to Cooper and me and gave us both signed Pistol Pete cards.”

Not many people can say they dumped water on Barry Sanders and Baker Mayfield, but Pistol Pete got to do just that in a Heisman House commercial airing this fall. The two Petes also got to see Sanders again when he came to campus for a football game.

With or without the legendary Cowboy, gamedays in Boone Pickens Stadium produce more than its fair share of highlightworthy moments for the students asked to set a tone for the fans from the sidelines.

“One of my favorite pictures is me running with a flag and looking up, just in awe of, like, what I got to do,” OSU cheerleader Cameron Carlson (management and marketing senior) said, recounting his first game at BPS.

The native of Littleton, Colo., estimates the largest crowd he cheered for in high school numbered somewhere around 1,100. Another way to picture that? Just imagine two percent of the people who show up to Boone Pickens Stadium on a fall Saturday.

Four years later, his voice still fills with awe at the thought of his first home football game, even though he had no connection to the university prior to his decision to leave his home state of Colorado for OSU Cheer.

Then of course, there’s the forever-memorable final Bedlam game, which saw the Cowboys come out on top 27-24 in 2023.

“I don’t even know how to describe it,” Rossman said. “I wish I could go relive that day over and over again, but it was an environment like I’d never seen before.”

She isn’t the only one. Armatta was on the sidelines cheering that night, but she still goes back to watch the highlights on YouTube just to recapture a piece of that night.

“Sometimes when OSU scored in our end zone, it felt like I scored with them,” she said. “Like I was just right there with them. It feels like we’re a part of the game.”

Armatta got plenty of photos of herself on the field during the madness that followed the Cowboy win to memorialize the moment, including one that she continues to use as her phone wallpaper.

Spirit coordinator and pom coach Beki Jackson believes some of the spirit group’s fondest memories years from now will come in the rare times the three groups of students get to come together in celebration for festivities at the beginning of the school year, the Christmas party and the Valentine’s Day party. She speaks from experience as a former pom member.

“What I remember from being on the team, more than anything else, more than stepping on the football field or on the basketball court, is I can tell you exactly where we were at the beginning of the year for the team dinner,” Jackson said.

Although the teams receive funding from the school, they rely on additional support from donors, which Jackson said continuously come through when needs arise.

“The check will be there the next day,” Jackson said. “I feel very fortunate to be in that OSU community that is so generous to our group.”

Perhaps the most important thing donors cover is the cheer competition at nationals, which Jackson said costs at least $50,000 each year. It’s a small price to pay for something that the team pretty much prepares for weekly, if not daily, for much of the year.

That team has a history of putting on quite the show. Head coach Lindsay Bracken’s group has won five national championships in the Advanced Large Coed Division, highlighted by consecutive titles in 2021 and 2022.

Carlson, who has served as an alternate at national competition for OSU before, said the emotion is overwhelming for everyone involved when the big moment finally comes.

“It doesn’t matter if everything hits, if everything falls, you are still just screaming,” Carlson said. “Because even if you’re not on the mat doing a routine, you’re at every practice. I’m nervous, excited for them, because I see how much work my teammates put in. And this team is a family.”

Armatta said she can barely remember the first time she competed at nationals due to the emotion of the moment. But she can vividly remember the moments right before.

“When I first stepped onto that band shell (where they compete), I remember having a single tear come out of my eye,” she said. “Because I finally just realized that all my hard work and dedication I have put into this sport has paid o , and I’m getting to represent the school that I truly love with all my heart.”

Facing a second-half deficit against Houston on Oct. 11, OSU fan Callista Bradford bet her brother ten bucks that he wouldn't go into an empty area of bleachers and take his shirt o . Trent Eaton took the bet, and his shirtless solo spirit caught the attention of the videoboard operator — and the nation. Looking for a spark of hope in a tough season, the Boone Pickens Stadium crowd cheered Eaton's e orts. Soon, another fan joined him in Sec. 231, t-shirts helicoptering in unison. Then two became four. And four became ... a movement. For the remainder of the 2025 season, the viral sensation continued at BPS and even spread to other college stadiums around the country.

The question still echoes in Annie Molenhouse’s mind.

“Do you ever picture yourself winning?” asked Kevin Andrews, an Oklahoma State University Athletics counselor, when he first met with the Cowgirl heptathlete.

Molenhouse couldn’t help but laugh. She initially hesitated to share her emotions, let alone entertain an idea she dismissed as far-fetched fiction.

Setting a personal record? Perhaps. Winning? No chance for someone who barely made it onto OSU’s track and field roster — even as a walk-on.

Yet, a few months later, Molenhouse grinned from ear to ear with a gold medal around her neck at the 2025 Big 12 Conference Outdoor Track and Field Championships in Lawrence, Kansas.

“It took me some reflection time,” the senior from North Aurora, Illinois, said. “At the moment, it was like, ‘Oh, my gosh, am I worthy of this? What just happened? How did I even get to this point?’ There was so much going through my head.”

Molenhouse shone as OSU’s first multi-event athlete to secure a Big 12 title and the third-highest heptathlon scorer in program history with 5,729 points. (The heptathlon is comprised of seven track and field events: 100 meter hurdles, high jump, shot put, 200 meters,

long jump, javelin throw and 800 meters.)

OSU associate head coach Josh Langley doesn’t see Cinderella stories every day.

“A lot of kids don’t get the fairy tale,” said Langley, who specializes in multi-events and vaults. “They get reality.”

Langley’s job requires him to give young athletes that dose of reality, even when it’s di cult. His email inbox is flooded with track meet highlights and cordial introductions from high school stars yearning for a shot at the Division I level.

OSU has limited roster spots and lofty standards. Most simply don’t make the team.

When an athlete from Rosary High School, a small Catholic preparatory school in the Chicago area, reached out to Langley in August 2020, he had to reply with rejection.

“I didn’t outright say no,” Langley said. “I told her, “Here’s what we have. Here’s what we are looking for. And, as you can see, you are a ways o — but stay in touch, and as you start approaching those times, maybe we can talk further. Most of the time, a kid never writes back or I never hear from them.”

That wasn’t the last time he heard from Annie Molenhouse.

Later in the recruiting process, Molenhouse’s high school athletic director even reached out to Langley, giving her a glowing recommendation any job applicant would envy, despite not having met OSU’s recruiting benchmarks. Although Langley again said no, he couldn’t help but consider Molenhouse and her unusual story

Growing up in a softball family, she didn’t run track until her freshman year of high school. She didn’t know how to hurdle until junior year, when she taught herself at home during the COVID-19 lockdown.

While lacking experience, she had undeniable persistence. Langley warned Molenhouse and her high school coach about the rigors of competing at OSU, figuring he could dissuade them from trying. Instead, the enthusiastic runner from Illinois was the one to persuade Langley.

“I started to think, ‘Dang, this kid wants to be here pretty bad, and I have done everything but tell her to go away,’” Langley recalled. “So I told her I’d give her a shot.”

In fall 2021, Molenhouse joined the Cowgirls as a freshman walk-on, competing for Langley and head coach Dave Smith

“I always like kids who have a passion for where they want to be and are willing to sacrifice,” Langley said. “I told her, ‘Hey, I’ll give you a chance, but I can’t promise you anything beyond a chance. You’re coming into a group that is extremely talented. You’re going to have to work really hard to even have a chance at competing.’”

For Molenhouse, the Cinderella cliché just doesn’t fit. There was no wave of a magic wand, no sudden transformation from blundering rookie into poised champion. At OSU, she faced setbacks, injuries and embarrassment. But even when she never expected herself to win, she wanted to get better.

Molenhouse couldn’t see the final picture because she was too busy putting together the puzzle

During chilly Chicago winters, a teenage Molenhouse and her father intently stared at a jumble of 1,000 paperboard pieces scattered across their bar table.

Rotate one piece. Move another.

Molenhouse and her dad, Pete, love solving jigsaw puzzles. At OSU, she persuaded her teammates to join in, giving their brains some exercise during down time at track meets.

Partially because of this cozy hobby, the Cowgirls know Molenhouse as “the grandmother of the group.”

She goes to bed at 9 p.m. She starts the morning quietly with a home-brewed cup of co ee in a dark room. She has worked as a nanny. Entering her fifth year at OSU, Molenhouse embraces her status as a team elder with the warm, wise persona to match.

The puzzle habit, however, isn’t all about living a grandmotherly lifestyle. The driven heptathlete chooses ambitious puzzles that can’t always be completed in one sitting and at first look like a confusing mess.

Molenhouse craves a good challenge.

That’s why she persevered through a rocky freshman year in Stillwater.

“I could tell she was lost, probably pretty homesick,” Langley said. “She’s really tight with her family.”

“

SHE HAS JUST SHOWN UP EVERY DAY TRYING TO GET BETTER. SEEING SOMEONE WHO HAD INVESTED SO MUCH OF HERSELF INTO THAT MOMENT, ACTUALLY GET THAT MOMENT — THAT’S PRETTY SPECIAL.”

— JOSH LANGLEY

The young walk-on formed new bonds with her OSU family, but they never coddled her. Molenhouse’s roommate, Olivija Vaitaityte, had been a multi-event athlete since representing her home country of Lithuania at age 13. Cowgirl teammate Bailey Golden was a seasoned All-American.

Molenhouse had a choice: rise to their level or get left in the dust.

“I just had to jump right into the fire, and they dragged me along with them,” Molenhouse said.

Molenhouse credits her teammates for showing her how to compete at OSU, but she also had to dig deep within herself. She had never been a heptathlete until college. Surrounded by experienced multi-event athletes, Molenhouse sometimes had to accept embarrassment.

“There is so much failure that comes before success in that kind of situation, but you can’t really let it get to you,” Molenhouse said. “If I were to let myself get upset about the progress that I had to make, then I would have never made the strides that I did. You’re going to fall on your face, and you’re going to bruise your legs and probably hurt yourself, and it’s just going to be how it is.”

Injuries threatened to thwart her progress. Dealing with stress reactions in her fibula and tibia, Molenhouse redshirted instead of competing during her first outdoor season.

The puzzle was in disarray. Then, she spent a crucial summer making it click.

Langley could nearly swear Molenhouse returned for her sophomore season taller than she was before.

Molenhouse laughingly said she doesn’t know about that, but she spent the summer of 2022 honing her skills to become a drastically di erent athlete.

At this point, Langley wasn’t just giving her a chance out of the kindness of his heart.

He saw true potential in Molenhouse.

“It wasn’t necessarily more work,” Molenhouse said. “It was more of the right work. I knew what to expect now. I knew what Josh expected of me. I knew what a workout looked like.”

Self-discipline guided her. She started summer mornings with a spin class at 5 a.m. and then, after her babysitting shifts, practiced on the track.

Injuries healed, and she gained strength. Then, during the 2023 outdoor season, Molenhouse competed in her first full heptathlon at the Jim Click Shootout in Arizona. She scored 4,878 points, about 400 more than Langley expected.

A pleasant surprise for coach and athlete alike, that breakout performance motivated Molenhouse to keep growing. At the 2023 Big 12 Outdoor Championships, she placed seventh in the heptathlon with 5,180 points, ranking fourth all-time in the Cowgirl record books.

With that milestone, she earned some scholarship money

Molenhouse pushed further, finishing seventh at the 2024 Big 12 Outdoor Championships with another personal record of 5,410 points. This year, she claimed her first All-Big 12 indoor honors, placing fifth in the pentathlon.

“I just always knew that there was more in the tank, and I wasn’t even reaching close to my full potential,” Molenhouse said. “It took my mind and my body a long time to get used to the level of training here. Once I got used to it, I knew if I just stuck it out that something good could come out of it.”

However, Molenhouse’s dreams had a ceiling. In her mind, she was still pursuing personal records, not chasing the Big 12’s best competitors. A championship just seemed too far away.

Molenhouse still needed to bring the mental picture into focus.

She had to believe in herself.

Molenhouse faced an uninvited foe in the heptathlon at the Big 12 Outdoor Championships last May.

A fierce Kansas headwind provided an extra challenge during the 100-meter hurdles on Day 1, and it persisted for the long jump on Day 2.

“It was so chaotic,” Molenhouse said. ‘Everybody was freaking out. And I was just like, ‘Well, whatever. We’re all jumping into a headwind.’”

Molenhouse carried that calm, nonchalant demeanor through all seven events, but steadiness hadn’t always come naturally to her. Entering the 2024-25 season, Molenhouse struggled with performance anxiety, so Langley encouraged her to see a team therapist.

Molenhouse was a little skeptical. She wasn’t particularly fond of therapy, but she listened to her coach and began regularly meeting with Andrews.

Now, she credits the counselor for helping her. With Andrews’ guidance, Molenhouse’s perspective of sports psychology — and her self-image — evolved.

“It actually started clicking,” Molenhouse said. “It was really interesting to see how if you just submit to it, it can make a di erence.”

Molenhouse figured out the mental game, but with the Big 12 outdoor meet approaching, she still avoided the three-letter word that starts with “w.” Instead of aiming for first place, she and Langley simply decided she would embrace the underdog mentality.

Molenhouse had to attack each heptathlon event as its own beast. After placing sixth in the 100-meter hurdles, she recorded her usual distance of 1.66 meters in the high jump, good for 10th.

Her best events followed. Molenhouse won the shot put with an attempt of 12.84 meters before placing first in the 200 meters, blazing through the race in 23.73 seconds. A personal-best time in her strongest event — combined with a large margin of victory — considerably improved her overall position.

Three events remained for the second day of competition. She finished sixth in the long jump with a distance of 5.65 meters. Despite a di cult warmup, Molenhouse recorded a 35.76-meter javelin throw, good for fifth. In the 800, the final event, Molenhouse clocked a time of 2:13.09 for a runner-up finish, gaining plenty of points to take the overall Big 12 title

“Her emotions stayed the same the entire time,” Langley said. “As a multi-event athlete, that’s exactly what you want. As a matter of fact, the only time I think I saw her show true emotion was after she won.”

After seven events, a huge smile broke across Molenhouse’s face.

Not so long ago, she expressed doubt in herself. When Andrews asked that powerful question — Do you ever picture yourself winning? — Molenhouse was forced to wrestle with her negative thoughts.

“I’m never going to win. I’m not in the position to win. I’m not that good.”

Molenhouse crushed those doubts when she accepted her medal as the first multi-event Big 12 champion in OSU history. Langley still gets emotional talking about it.

“She has just shown up every day trying to get better,” Langley said. “Seeing someone who had invested so much of herself into that moment, actually get that moment — that’s pretty special.”

Molenhouse treasures her memories of the whirlwind experience.

She remembers Smith, her head coach, confidently pumping his fist after her strong finish in the 200. Katie Chapman, her teammate, joyously tackled her on the ground after the 800. Immediately, Molenhouse wanted to find her family and celebrate.

She also remembers Langley greeting her with powerful words: “From walk-on to Big 12 champion.”

With one outdoor season left at OSU, Molenhouse is chasing her goals with elevated confidence. An MBA student and aspiring coach, she knows her story can inspire future athletes. If she ever needs a reminder, she can look back at photographs from that joyous championship, proof it wasn’t all in her imagination.

Annie Molenhouse can picture herself winning.

Annie Molenhouse has already won.

OSU freshman Simon McCroskey captured this captivating image from the rooftop of Boone Pickens Stadium during the Cowboys' Nov. 15 game vs. Kansas State. Shooting with a Sony A7RIII, the sports media major from Houston, Texas, used a special "tilt-shift" lens, which gives extra blur to out-of-focus areas. "Shooting from higher levels with a tilt-shift lens mimics how standard lenses and human eyes would see smaller objects, such as toy sets, which is what gives the photo a miniature e ect," McCroskey explained. McCroskey is one of 25 undergraduate creatives helping provide photography, videography and graphic design content for OSU Athletics.

A plate of food in his left hand, Joe Eastin makes his way from the bu et counter back to his midfield suite at Boone Pickens Stadium. Eastin needs his right hand free to shake hands as he navigates through a small, but upbeat, congregation that includes Oklahoma State University’s president among its familiar faces.

It’s almost halftime, and while the game versus Kansas State started promisingly for the Pokes, Eastin has missed most of it so far.

Sporting bright orange blazers, Eastin and his fellow executive board members of The Code Calls (OSU’s $2 billion comprehensive campaign) had been recognized on the football field during a first-quarter timeout. The winding trek from the turf back to the suite level meant more handshakes, quick chats and elevator encounters along the way.

Finally back in the suite, Eastin sets his plate on a co ee table, but he doesn’t sit down. He’s still engaged in conversations — with college deans, administrators, fraternity brothers, friends and family — giving each one his full attention in turn. Lunch will have to wait a little longer.

This is typical Joe Eastin.

He’s a connector. Of people. Companies. Causes.

you have less time. You always think you’re going to have more time. It’s actually the opposite. So it takes a little more focus, but I do my best to make others a priority.”

“Joe’s superpower, if that’s what you wanted to call it, is that he’s so genuine,” says OSU Athletic Director Chad Weiberg. “He genuinely cares about people. There’s a realness of who he is, and that’s what draws people to him and what allows him to connect. He’s got people gravitating to him, and he is able to make all those connections.

“Joe is just somebody that you want to be around.”

The youngest of four siblings, Eastin was born in Tulsa but raised near Adair in northeast Oklahoma.

“My dad is from the Owasso area and grew up in a farming family,” Eastin says. “He was the youngest of 12. My mother is from Colorado, and they met while my dad was in the Air Force. After his service concluded, they moved back to Oklahoma. I think he wanted to be back in a farm and ranching community, far enough away from everyone else. We didn’t have ties to Adair, but he bought a small farm in Mayes

Though humble, Eastin’s rural upbringing was idyllic, he says, instilling values that shaped his character.

“It was great. It was a wonderful way of life. Obviously, it teaches you hard work and discipline and responsibility. And I think in all these situations, you have to be a bit of a MacGyver to figure things out, because there’s no one else to call, especially back then.

“But it was great. And it helped me save some money and put myself through college, basically. Working there, working part time, plus scholarships and financial aid, I was able to go to OSU after high school.”

Elected senior class president, Eastin was one of 58 students in the Adair High School class of ’88.

“I was one of the captains of the football and basketball teams,” he recalls. “I was very involved in sports growing up. Loved football, loved basketball. I ran track because the coach made me run track for the other two sports.

“In a small town, you’re working, you’re going to school, you’re playing sports. That’s what our life centered around.”

Despite being a talented, multi-sport player for the Class 2A Warriors, collegiate athletics weren’t in the cards for Eastin.

“Everyone that’s a high school athlete has dreams of playing at the next level,” Eastin says. “My coach said, ‘You’re really good, but you run like a dry creek.’ We had a good time, though. It was great.”

The choice to attend Oklahoma State came late for Eastin, who came from an athletic family, but didn’t grow up with a particular rooting interest.

“My parents didn’t go to college. My oldest brother, David, played juco basketball and transferred to Tulsa where he played for a short time and finished his engineering degree there. My sister, Donna, won a girls’ basketball state championship at Adair. She was an education major at NSU (Northeastern State University) in Tahlequah. My second brother, Jim, could have played football at the next level and would have studied engineering, but chose not to.

“Just from a financial standpoint, I didn’t even think about going out of state at all. I was going to go to OSU or OU, one of the two public institutions, and got into both. The week before school started, I had to make a decision. I chose OSU … And I loved it.”

Eastin had only visited the campus once prior to the fall of 1988, but he quickly became immersed in college life as a freshman on the fourth floor of Willham South.

“I didn’t know the drill. I didn’t know the routine. But I moved in with a buddy of mine in the dorm, and we had a great first year. Obviously, that was a wonderful year for football in 1988, with Barry (Sanders) and the team. It was just so exciting going to those games as a freshman. I still remember the opening kicko when Texas A&M came to town. Barry ran it back for a touchdown. We were like, ‘Whoa! We may have something special here.’ So that was a super year.”

Sanders, who obliterated the record books on the way to winning the Heisman Trophy that season, was also a frequent pick-up basketball game player at the Colvin Center Annex — as was Eastin.

“It’s funny. I was talking to him earlier this season at one of the football games, and I said, ‘Barry, it’s great to see you again. You won’t remember, but the first time you and I met, you dunked on me in the Colvin — that’s a true story!’ Barry laughed and said, ‘I don’t think they would let studentathletes go do that stu now that we used to do all the time.’”

It was on those same courts where Eastin made some lifelong connections, meeting members of the Delta Tau Delta fraternity. They encouraged Joe to pledge the following year.

Meanwhile, Eastin was a fixture in the bleachers at Gallagher-Iba Arena.

“Basketball had some terrific athletes, but we weren’t going very far in the tournament. That following year is when Eddie Sutton showed up and turned things around on the basketball court.”

Eastin says he even made his own coaching memories on the venerated white maple floor.

“I’m 0-1 as a head coach at Gallagher-Iba Arena,” he grins.

“In 1991, I was the volunteer coach for the Theta house girls’ basketball intramurals. It was my second year of coaching the team. The first year, we got knocked out of the playo s, but in ’91, we won our entire side of the bracket all the way through.

On the other side of the bracket were the reigning champs, coached by a well-known Cowboy alumnus

“Bill Self was a new OSU assistant coach at the time, and he was volunteering his time to coach them. We met in the championship game at Gallagher-Iba Arena … and I’m loving it. The girls are warming up, Bill and I are standing out there with our arms crossed like coaches do, talking. My team had a few all-state basketball girls from typical, small towns in Oklahoma. Coach Self’s team had some amazing athletes. Some of them had definitely played at a higher level.

“We tipped-o , and by halftime, we were winning! Coach Self was not very happy. I can see why he’s had so much success today — he went in the locker room at halftime and restructured some things with those girls, and they came out and ended up beating us by 10 points.”

When reached for comment, Self replied: “To this day, the greatest sporting accomplishment in my life was to win that intramural championship,” tongue planted firmly in cheek.

The hall of fame coach added that, “Joe did a great job” … but the Thetas just didn’t have the athletes that Self’s team possessed. It was a friendly competition, and both squads made their way to Eskimo Joe’s for a postgame celebration.

“We had so much fun,” Eastin adds. “That’s my one-and-done coaching history.”

These days, Eastin can be found in the front row at most Cowboy Basketball games. With four seats across from the OSU bench, he often brings family and friends from Dallas to share the courtside experience.

“Maybe I’m reliving my younger days, but I just love being right there in the action,” he says. “I love it. I’m so grateful to have the opportunity to do that and be in the moment. You do have to watch yourself — and you have to watch your feet, so you don’t trip anybody — but I just really love getting absorbed into the game.

“In the last couple years, I had the opportunity to go to KU and to Duke, and I would put GIA up against those two venues. There’s not a bad seat in the house. It’s the same way for wrestling. You talk about an electric place when you have Cowboy Wrestling in Gallagher-Iba. The place is historic.”

Eastin earned a degree in business administration with a marketing emphasis from the OSU College of Business Administration (now Spears School of Business) in May of 1992.

“The job market wasn’t great at that time,” Eastin recalls. “I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do. I just knew I needed to get a job. Obviously, I had debt from school, so I was working at it and trying to figure it out.

Eastin says he considered O cer Candidate School and began the application process.

“That was a very serious thought, but then I landed a job right before I graduated and decided to go the business route. It started as a sales job in Tulsa, and eventually I worked my way into management.”

Early on in his career, Eastin was transferred to Austin.

“I lived there for three years and had a great experience. Then I lived back in Tulsa for a little bit, working for a software company. And then I took a job with Entergy, big power utility company based in New Orleans. I spent time in New Orleans and

and in Tampa, Florida, where they had another operation. From there, I moved to Dallas.”

Eastin says he “followed the corporate ladder” for about a decade before taking a leap of faith with a former colleague, William Addy

“Bill and I had worked together before, and we saw that there was an opportunity with the rapidly growing Internet,” he explains. “I had worked in technology, software and in the energy business — particularly the energy generation business. From there, ISN was started at the very end of 2000.”

Eastin says he and his partner went “all in” on the venture from the start.

“We quit our day jobs, and we went for it,” he says. “We sputtered around for about a year and finally landed some clients in the pipeline business. Bill and I would drive to Houston from Dallas every week and call on people and try to understand their needs, then work with our software engineers to develop a software platform. It was a lot.”

His modest background and cowboy grit served Eastin well in these uncertain circumstances.

“There were some scary moments, but it was fun,” he admits. “Bill and I would drive, because we couldn’t a ord to fly, and we’d split one hotel room and split meals just to try to make sure that we didn’t run out of our dry powder with two pots. And we didn’t have a lot of dry powder.”

Shortly after ISN was launched, Eastin took another leap of faith: He proposed to Monica Wiman. They married in 2004.

“Monica has been great all through the years and really trusted my judgment as we took these big risks. She’s been very supportive.”

Although Monica hails from the big city, Joe says she shares his land-grant values.

“My wife did not go to OSU, but she’s adopted OSU,” he says. “Monica was born in Fort Worth and grew up in Dallas. She put herself through college at the University of North Texas, so she has an appreciation for our similar backgrounds in that regard.”

Eastin is the Executive Chairman and Chairman of the Board at ISN Software Corporation, which he co-founded with Addy in 2001.

“I know it sounds crazy, but the Internet was still relatively new from a commercial enterprise usage, and especially with traditional assets, such as industrial or energy or manufacturing. We thought there might be a way to have a better tracking mechanism utilizing the Internet and the data that surrounds it.

“Like a lot of businesses, when you start something, you end up pivoting, and we pivoted and focused on the pipeline

industry. We were working with liquid and natural gas pipelines throughout the country as they were trying to meet some regulatory demands, particularly around their contractors and suppliers. And that’s where we came in … From there, we went into downstream, upstream, di erent parts of energy, and then into di erent parts of manufacturing. Steel, pulp and paper, food, automobile, all sorts of di erent manufacturing — really any capitalintensive company where there’s some level of risk that utilizes third parties, contractors, and suppliers. That’s our sweet spot.”

A very big sweet spot, it turns out.

“

He wants to know what he can do to help you. It’s never the other way around."

— CHAD WEIBERG