Connecting the divided

University Amsterdam University

Program MSc Architecture

Project Graduation project | Navvab Bazaarway

Study year 2024-2025

Student Yara (Fatemeh) Mahmoudyar

Committee Barend Koolhaas

Azadeh Arjomand Kermani

Wouter Kroeze

Connecting the divided

University Amsterdam University

Program MSc Architecture

Project Graduation project | Navvab Bazaarway

Study year 2024-2025

Student Yara (Fatemeh) Mahmoudyar

Committee Barend Koolhaas

Azadeh Arjomand Kermani

Wouter Kroeze

Connecting the city in the north-south direction, Navvab Highway stands as one of the main arteries of the city. It is impossible to reach the old city center without traversing this corridor. Despite its success in uniting the two poles of the city, experts often characterize it as a “polluted open-air tunnel.”

While residing in Tehran, even though I personally navigated through this infrastructure fewer times than I can count on my fingers, it genuinely felt like an overwhelming commuting experience. However, for residents living in the adjacent streets, the experience of this corridor would be entirely different.

I have chosen this topic for my graduation project to delve deeper into this urban project, aiming to comprehend why it was constructed initially, how it functions for both the city and its inhabitants, and what implications it may hold for the city’s future. To gain a more profound understanding of Navvab’s operation and its integration with the city, we must commence with a brief exploration of the modernization history of Tehran.

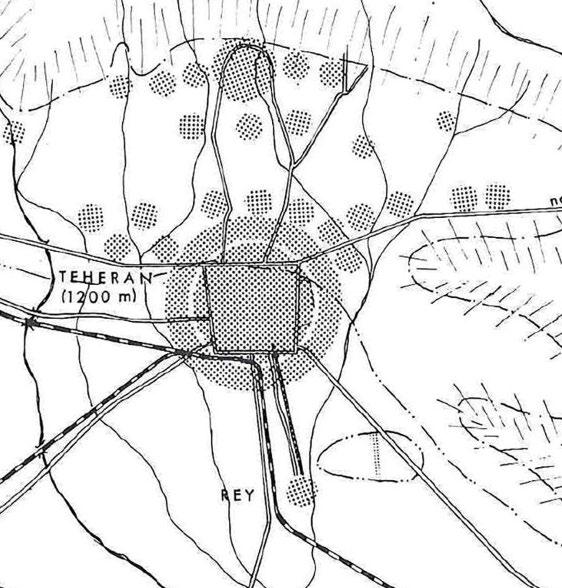

When Tehran was established as the capital of Iran, it housed only around 15,000 people and harbored no aspirations for modernization. In the subsequent years, the vision of modernity began to take shape, but the people and the city were not fully prepared for such transformation.

Reflecting on the history of modernity in Iran unveils four pivotal moments associated with four key figures who aspired to modernize the country, each guided by their distinct ideologies and perspectives influenced predominantly by the West.

Concurrently, driven by various factors, most notably the concentration of resources in the capital, the influx of migrants surged as individuals flocked to the city in pursuit of a better future. This unregulated expansion, coupled with dominant urban planning ideologies, has collectively shaped the city into the experience we witness today.

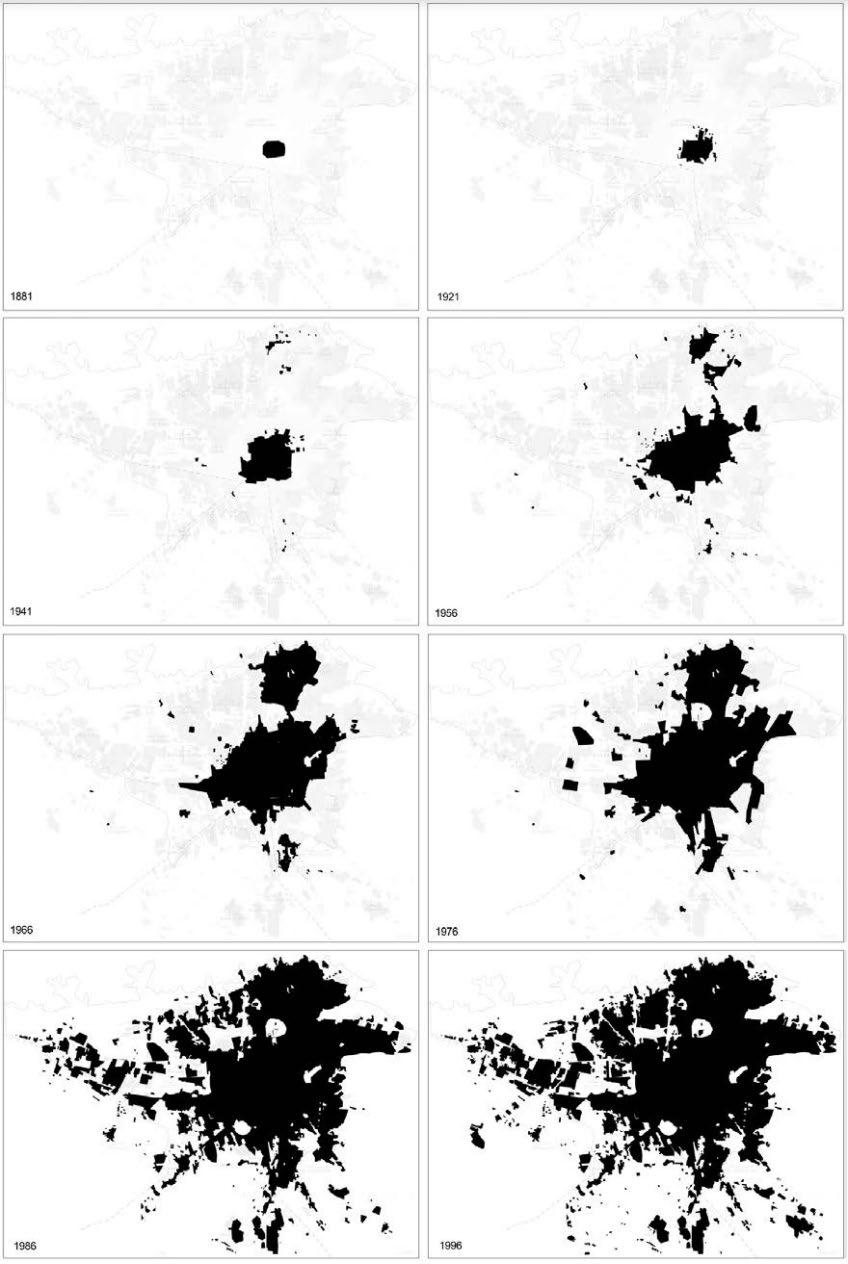

The formation and modernization of Tehran are marked by several key points. By charting these elements and tracing the city’s expansion over time, we gain insights into the crucial roles these factors played in shaping the city during that era.

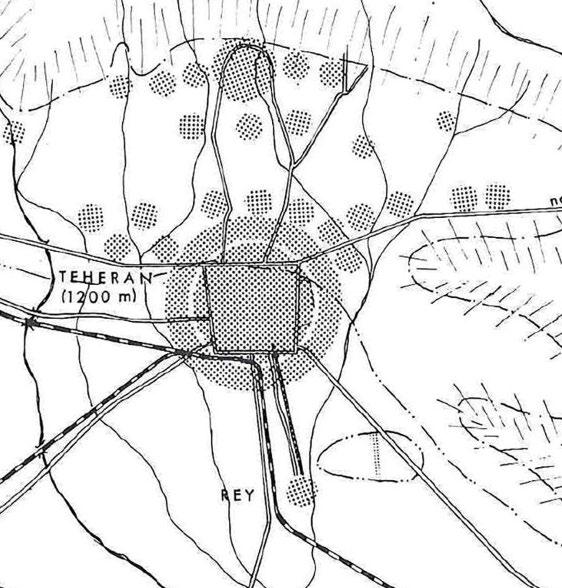

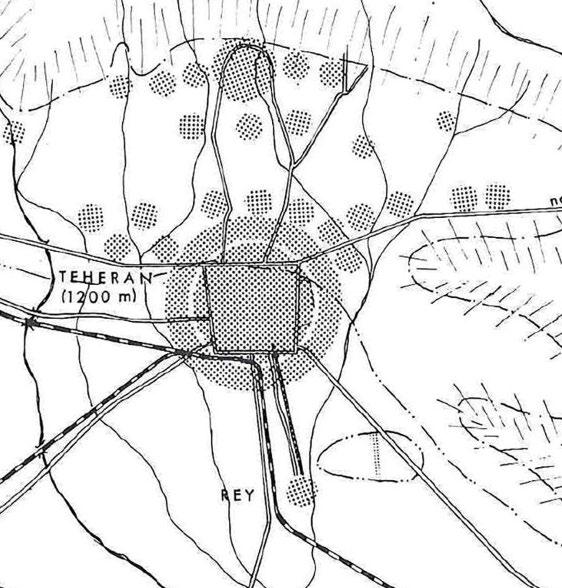

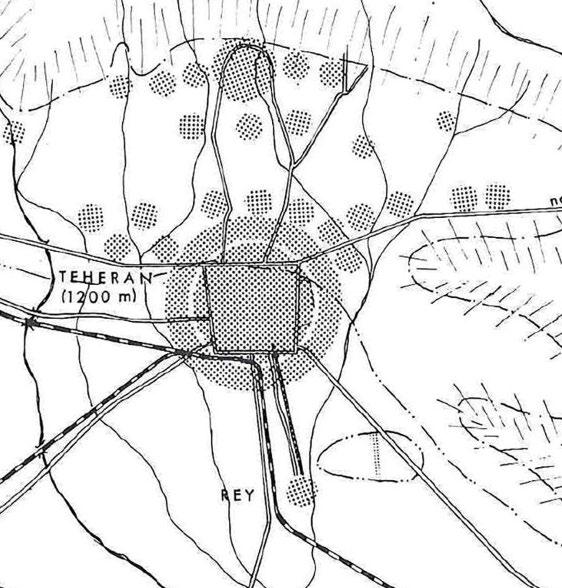

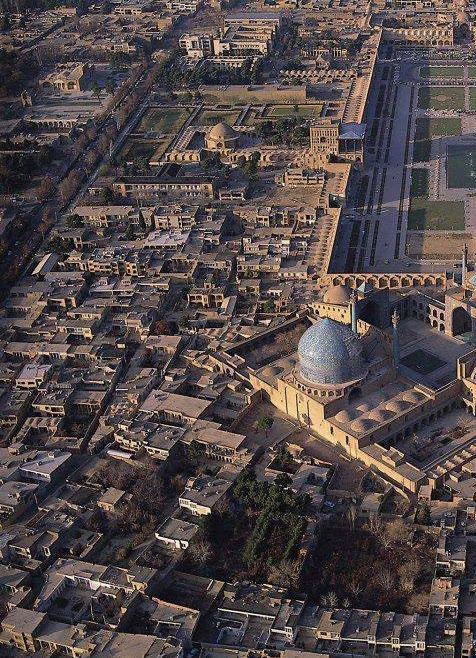

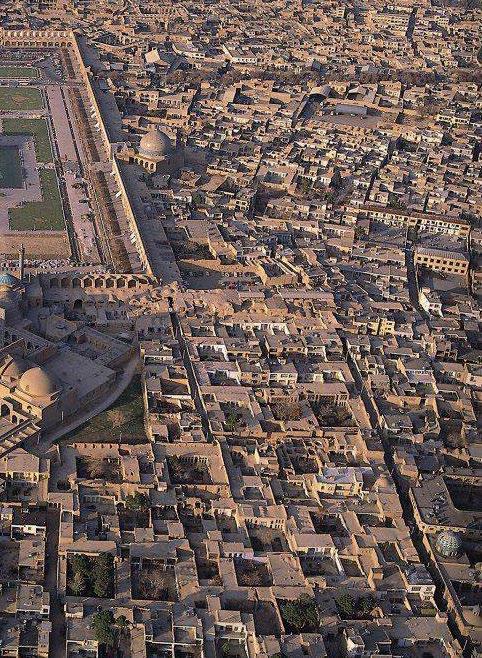

In 1796, Shah Agha Muhammad Khan, the founder of the Qajar dynasty, made a strategic decision to relocate the capital of Iran from Shiraz to an enclave nestled in the shadow of the Alborz Mountains. Despite a lack of clear and convincing reasons for choosing this particular location over the once glorious city of Isfahan during the Safavid dynasty, some scholars propose that geopolitical considerations, particularly threats from the east and north borders, prompted the move. The rugged terrain, with mountains providing an additional layer of defense, may have factored into this decision. The historical city was originally structured around three essential elements vital for its functioning: the bazaar, mosque, and royal court. The walled city, spanning 19 square kilometers, carried a Mahalleh system. Unlike a social class-based arrangement, the Mahalleh or quartier system organized residents along ethno-religious lines, bringing together people of the same ethnic or religious affiliations, regardless of wealth. This organizational framework persisted until Naser Eddin Shah’s expansion of the city walls and ditches in 1860.

Between the years 1797 and 1890, Tehran witnessed remarkable growth, evolving from a population of 15,000 to 250,000 in its first century as the capital.

As the population expanded, the city grappled with a shortage of space and land, exacerbated by infrastructure challenges. Influenced by intellectuals who had studied and traveled to Europe, gaining firsthand exposure to modernity, Nasereddin Shah of the Qajar dynasty directed the formulation of a new plan for Tehran. This plan aimed to address the growing population, integrate outsiders more effectively, and manage the frequent riots sparked by protests over bread shortages.

The plan characterized by an octagonal layout enclosed by moats and walls featuring fifty-eight bastions and twelve gates, drew significant inspiration from the concept of a ‘modern city,’ notably influenced by Baron Haussmann. Interestingly, this plan retained the Mahalleh system. In contrast to the organic narrow streets of the historical center, the new design incorporated iconic Parisian-style straight and wide streets, significantly expanding the city.

Haussmann introduced wide tree-lined boulevards and grand avenues, contributing to the aesthetic and functional transformation of the city. These new thoroughfares also served strategic and military purposes by making it difficult for barricades to be erected during periods of civil unrest. While not the predominant feature, this strategic element is indeed discernible in the expansion of the urban plan.

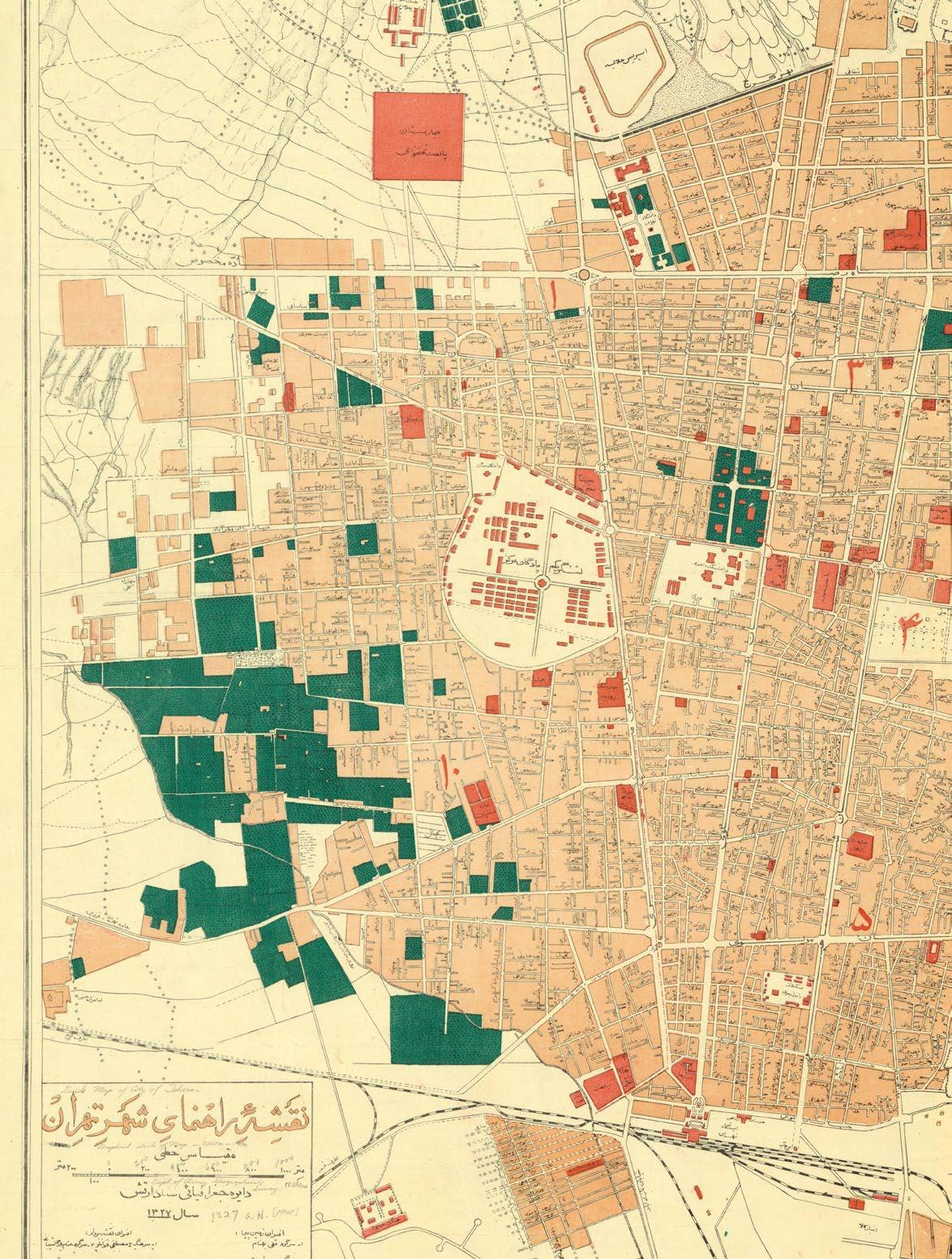

Modernizing under Reza Shah’s order in 1920

The next significant moment of urban modernity has to be the top-down cultural and sociopolitical reforms of Reza Shah (1921–1941).

By abolishing the immediate past’s legacy the city grew nearly three-fold, reaching an area of around 46 km2. When Reza Shah (the first of the Pahlavi dynasty) ascended to power, the city and its people were grappling with the aftermath of World War I and the constitutional revolution, resulting in governance complexities and chaos. He exhibited a rapid destruction-construction dialectic to compensate for the time lost to joining the modern reformations. This only lasted until the beginning of World War II.

Reza Shah’s vision for modernizing the nation revolved around constructing infrastructure to facilitate highefficiency trade in the region, industrializing the country to generate employment, and implementing a higher education system to educate experts. As a result, the city’s boundaries and expansion during his era were notably characterized by the strategic placement of the national train station and Tehran University.

University of Tehran the first higher education european style in Iran.

Tehran train station for The TransIranian Railway.

Expanding noth-ward via Pahlavi street; connecting to the northern villages and settelments.

Expanding east-west via Reza shah street.

The city walls were demolished once and for all in the 1930s, and attempts were made in the following decade to end the mahalleh system, through the adoption of a zoning pattern based largely on class segregation. A new urban model took shape, with modern buildings and boulevards designed by European and European-trained architects. Nevertheless, many aspects of the older urban structure and social organization persisted, now juxtaposed with the emerging realities of the city of petro-dollars.

Another important intention of the 1920-1940 urband development was to deviate the centrum away from the Bazaar and the cities masque. That is why an expansion of north and west ward is dominantly visible in the folowing years.

Modernizing under Mohammad Reza Shah’s order in 1941

Following a prolonged interruption in the modernization project due to World War II and a myriad of intricate political and geopolitical factors, power transitioned to Reza Shah’s successor, Mohammad Reza Shah, after a CIA-instigated coup. He successfully consolidated his power in 1953 and set forth an ambitious goal of creating a “Great Civilization,” representing the third attempt at the modernization of the nation.

After almost a decade of rapid population growth and unregulated city expansion, compounded by the absence of a robust government to govern effectively, the need for organization became increasingly apparent.

Area for unsupervised urban sprawl by 1956

In the aftermath of World War II, as the Cold War gained momentum, the United States sought to counter Soviet influence in various regions, including the Middle East. In 1949, President Truman’s policies aimed to maintain stability in developing countries, and the Middle East became a particular focus.

Under Truman’s policies, economic assistance was extended to Iran to bolster its post-war reconstruction efforts and reduce the risk of Communist influence. Point Four of Truman’s policies is particularly noteworthy in this context. Iran benefited from financial aid as a result of this policy, with international experts playing a crucial role in accelerating the pace of modernization in the country.

Simultaneously, after an extensive and prolonged struggle with the nationalization of the oil industry in Iran, liberating it from the direct colonial influence largely controlled by British interests, a significant turning point was reached. On March 17, 1951, under the leadership of Mohammad Mosaddegh, a member of the Majlis for the National Front and future prime minister of Iran, the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company (AIOC) was successfully nationalized.

The oil nationalization movement yielded two major outcomes: the establishment of a democratic government and the pursuit of Iranian national sovereignty. With the infusion of oil income, and all the resources channeled to the capital, Tehran was on the verge of witnessing a new era of modernization and development.

The area of the city reached 180 square kilometers in the mid-1960s, with a population of around 3 million. Under the direct influence of John. F. Kennedy’s presidency, Mohammad Reza Shah aimed to tackle the urban sprawl, with the preparation of the first master plan of Tehran. The Tehran Comprehensive Plan (TCP) was a grand moment of urban modernity in Tehran.

This time, a collaboration of foreign-trained Iranian architects with international architects and planners was on the agenda. Farmanfarmaian’s office was selected as the local architectural influence. Farmanfarmaian was the cousin of the head of the economic bureau and had graduated as an architect from the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and by 1975 became the biggest architecture/planning firm in Iran with four hundred architects.

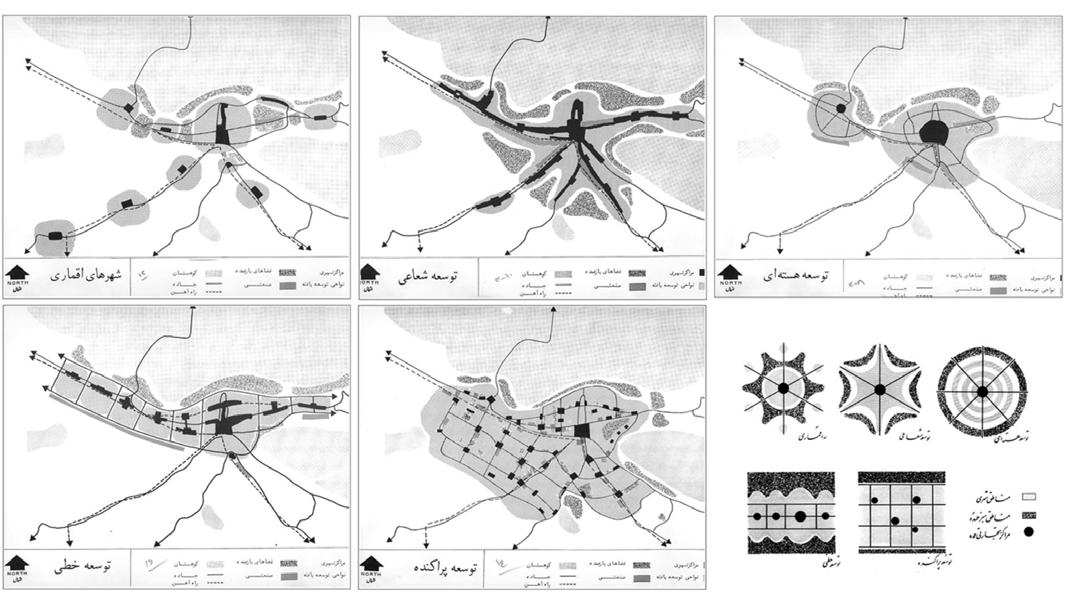

The Tehran Comprehensive Plan was designed to bring new order to the irregular urban expan- sion of the city and respond to the growing number of rural migrants and the congested city centre. The Tehran Comprehensive Plan (TCP) that was approved in 1966 entered the implementation phase in 1968. At the time, more than 30% of Iran’s urban population lived in Tehran.69 The TCP was inspired by a post-war modernist idea of planning that sought to create the ‘ideal city’ through ‘comprehensive’ development.70 The plan’s aim was to reduce the density of the city centre by proposing a series of centres to reorient growth and reorder social structures. Tehran’s growth is restricted by mountains to the north and the east and by desert to the south, making expansion in those directions physically and economically impractical. Instead, the TCP proposed a linear decentralization, stretching the city westward.

The TCP approach towards the future development of the city was similar to the American post- war planning debates, which focused on resolving urban problems through decentralization, and reorganization of the living space of cities using two key elements: the ‘neighbourhood unit’ and the ‘super-highway’.

The TCP envisioned that by 1991 Tehran would have 10 different regional centres, each supporting half a million inhabitants in an area of 150 ha, separated by large green areas and linked by a network of highways and rapid public transportation. Over 150 km of highways would enable the growth of the city west, with private automobiles as the pri- mary mode of transport. The optimism and utopian vision of Gruen and his Iranian partner to produce the ideal city for ‘modern living and modern transportation’ had a significant impact on the plan. Inspired by Clarence A. Perry notion of Neighbourhood Units and Ebenezer Howard’s Garden City, Gruen and Farmanfarmaian’s proposal introduces a range of neighbourhood units, with different densities for different income groups. As shown, neighbourhood units for lower, middle, and upper income groups varied in population from 3000 to 5000 resi- dents.75. These neighbourhoods were designed based on Perry’s units, organized around certain key planning principles, like the necessity for a school and playground within 500 m of each house, and neighbourhoods defined by major streets, with 10% of the land area dedicated to open spaces and community activities.

The ‘neighbourhood unit’ and the ‘super-highway’ schemes were designed to distribute facilities and services and create high-quality living space. The TCP envisioned the city as a city for the middle class with no poor population. The assumption was that Tehran would be socially mobile, and the visible life- style of the upper classes would motivate the city’s poorer residents to get better jobs to earn more. Ulti- mately, the new Tehran was imagined to be a utopia for the lower classes, as imagined their mobility to higher class levels regardless of the limitations of the parts of the city they inhabited.

The planning team working on the TCP in the Tehran office, 1968. Fereydoon Ghaffari, in the middle of the photo who has a pen in hand, presents the plan to the team.

Source: Fereydoon Ghaffari.

Five alternatives for Tehran’s urban pattern.

Source: Victor Gruen and Abdolaziz Farmanfarmaian, “The Comprehensive Plan of Tehran”.

Source: Victor Gruen and Abdolaziz Farmanfarmaian, “The Comprehensive Plan of Tehran”.

Source: Victor Gruen and Abdolaziz Farmanfarmaian, “The Comprehensive Plan of Tehran”.

Source: Victor Gruen and Abdolaziz Farmanfarmaian, “The Comprehensive Plan of Tehran”.

In truth, by the late 70s, one could hardly find a similarity between the reality of Tehran and the ‘ideal city’ image that was presented by the 1968 master plan. In a society where 46% of the population lives below the poverty line (as per the World Bank) and does not have access to clean water, Gruen and Farmanfarmaian’s report hardly suggests a solution for accommodating the impoverished in Tehran. Instead, it advocates for income-segregated ‘neighbourhood units’ in a city already marked by social divisions accentuating the existing socio-spatial polarisation of the city.

Coupled with other political and societal decisions made around that time, which neglected the needs of the poor and low-income class, and considering the clergy’s influence on the population, widespread discontent emerged. This culminated in massive demonstrations, with people demanding Shah’s removal from power and advocating for something called the revolution of the poor.

The revolution was indebted to the poor and working class in villages and the peripheries of big cities who were excluded from the benefits of the elitist development policies of the Pahlavi government. Upon his arrival in Tehran, Khomeini promised to ‘build homes for the poor all over the country... this Islamic Revolution is indebted to the effort of this class, the class of shanty dwellers’ (Athari, 2004:52)

In truth, none of the modernization ambitions, despite some notable achievements during this period, truly originated from the genuine needs and realities of society over the past 150 years. Because of the disparity between Iran and its global counterparts, each ruler swiftly closes the gap by using the latest technologies or methods. However, this approach often exacerbated the city’s fragmentation and division because the body of the society was not quite ready for the change. Above all, beneath these developments, construction and planning seemed to serve as a means for rulers to showcase and assert their authority and power, solidify their position, and gain acknowledgment.

In the wake of the Iranian Revolution, the TCP was largely abandoned due to its association with the deposed Shah, foreign influences, and the promotion of Western values and lifestyle – aspects that were criticized and rejected. However, we will soon discover that the post-revolution Islamic government strategically adopted certain aspects of Gruen’s ideas regarding the city’s future density and growth. This served as a way to market undeveloped land, effectively permitting private developers to independently carry on with the city’s construction.

The 1979 Revolution and the fall of the Pahlavi regime sparked intense nationalism in Iran, yet this sentiment was soon overshadowed by extreme Islamists during the early stages of stabilization. With Ayatollah Khomeini as their leader, the newly established Shia clerics leaders propagated an anti-Western ideology, distancing themselves from the previous regime and even foreign countries reshaping the country and its geopolitical relations. They believed foreign nations had intervened in the country’s internal and international affairs, and obstructed its progress and development.

These changes had a significant impact on various plans, including the Tehran Comprehensive Plan, which was associated with Westernization. Notably, Farmanfarmaian and other foreign architects in Tehran left due to this shift. It became clear that the religious-fanatical group was driving Iran’s swift changes, and if they had stayed, they would have been jailed or were executed by revolutionary forces.

Despite demonizing the TCP, it continues to be respected as one of the most comprehensive urban studies to this day.

In the years after the revolution and throughout the IranIraq war, not only 2.5 million war refugees poured to the city, but also over two million Afghan refugees fled to Iran by 1985 and Tehran’s growth pushed westward and southwestward resulting in temporary shelters in major urban areas. By 1988, when the war concluded, Tehran had developed an expansive urban landscape, which grappled with significant socio-cultural and environmental challenges. By 1990, Tehran, with a population of nearly seven million people, was polluted, overcrowded, spatially fragmented, and suffering from a lack of transport networks and municipal services. In the early 1989s the first presidency was elected and, Hashemi Rafsanjani’s body of government started to take shape mainly consisting of the revolutionists and technocrats.

The municipality of Tehran was led by Gholam Hossein Karbaschi, mayor of Tehran in 1990-1998. After the IranIraq war, the municipality was practically bankrupt. Not only Tehran’s urban regeneration was high on the agenda, but also revolutionist authorities had intended to set Tehran into an iconic example of the Islamic state’s developmental success to further stabilized their situation for the populace and internationally.

On top of everything, the municipality was banned from collecting land taxes, a move that would clash with the goals and ideology of the revolution. The working class and underprivileged citizens during the Pahlavi era were dissatisfied with wealth distribution. They rallied behind the revolution, which promised them decent housing and job prospects, not more authorities collecting money from them to invest in government projects, thus taxing them would have had political consequences. Upon his arrival in Tehran, Khomeini promised to ‘build homes for the poor all over the country... this Islamic Revolution is indebted to the effort of this class, the class of shanty dwellers’. (Athari, 2004:52)

So the municipality had to become cre ative in financing its projects. First, it introduced the “Municipal Fiscal Self-Sufficiency Act” in 1989 to economically decentralize municipalities and encourage local economic development and it was approved the same year. Second, Karbaschi claimed the right to Tehran’s skyline. The municipality would only collect fees and taxes from developers and investors who either wanted to go beyond the height limit or make modifications to the zoning regulations.

Throughout the 1980s, the only official plan for Tehran was the 1968 Tehran Comprehensive Plan. As there was nor enough time or funding to support a new comprehensive study for the city, TCP was adapted and modified to the liking of the post-revolutionary municipality and urban authorities. As a result, the combination of all the abovementioned policies led to an explosion of high-rise construction in different parts of the city, especially in the north, where profit rates were higher.

1996

Old Tehran: Historical Centrum

- organic shape

- narrow

- low-density neighborhoods

- society division based on religion and ethnicity

Tehran 1890

- influenced by Haussmann idea of the “ideal city”

- straight shape

- wide tree-lined boulevards

- society division based on religion and ethnicity

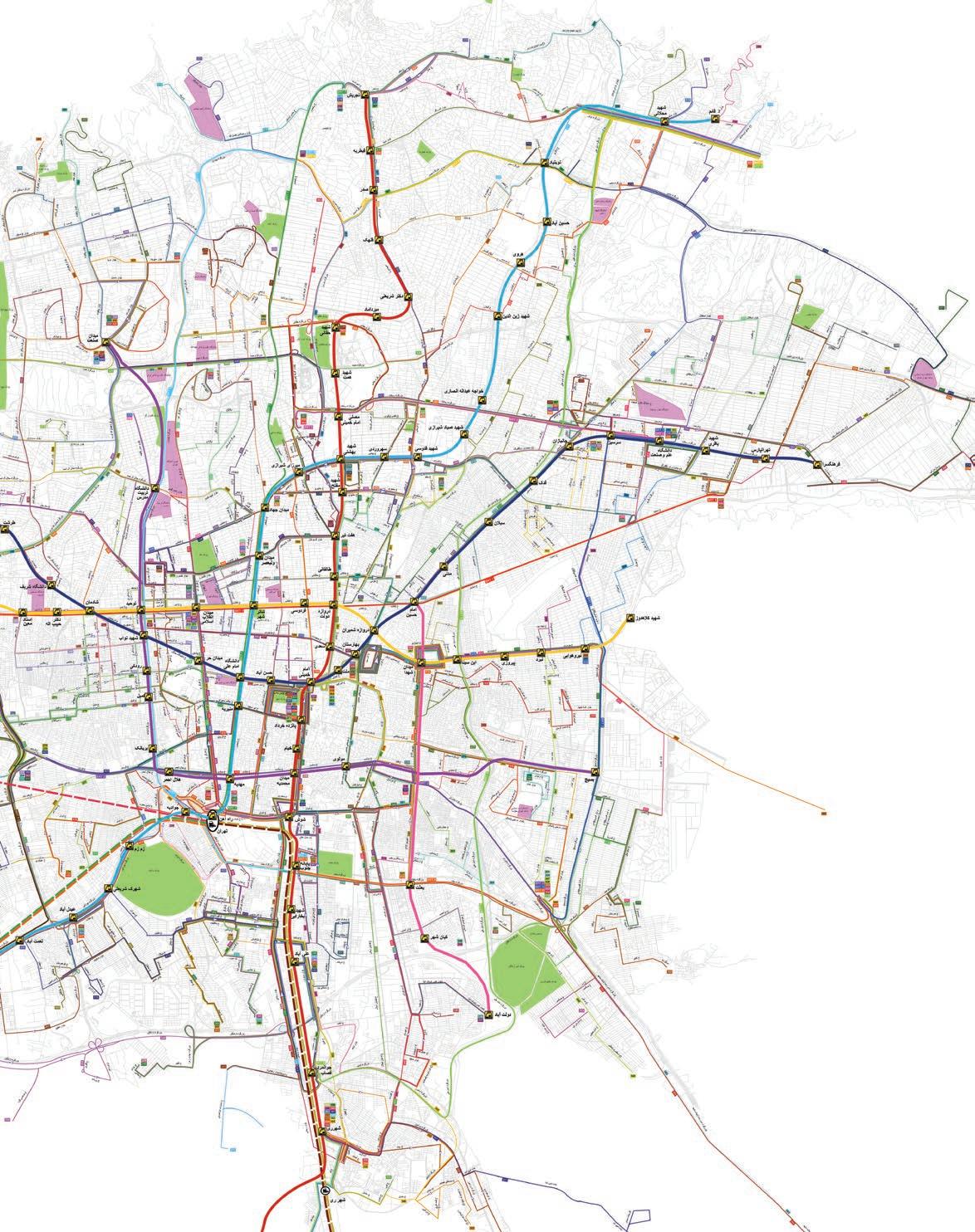

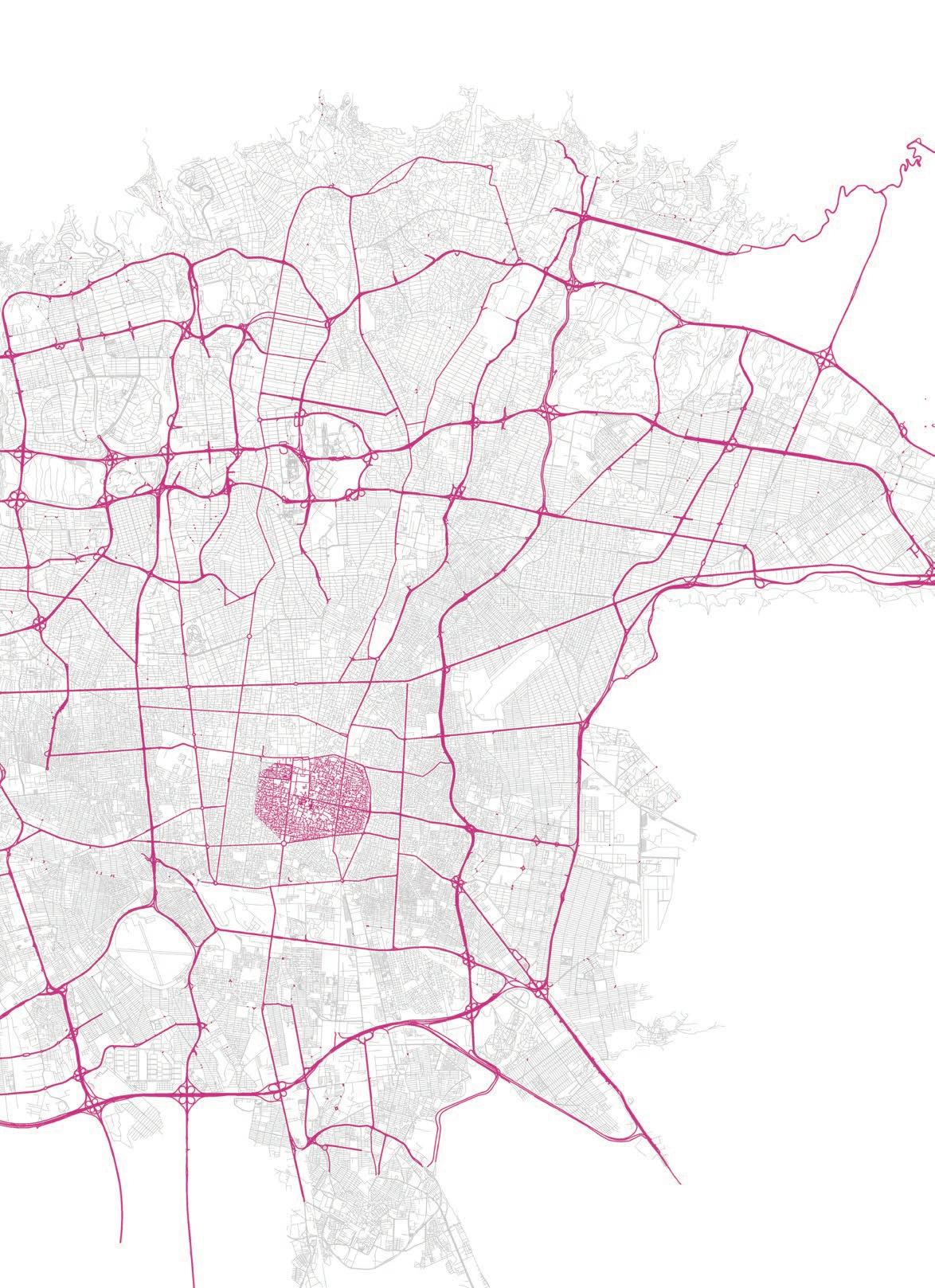

Characteristics of existing transportation networks in Tehran

Tehran 1930

- unregulated expansion

- introduction of highways

- rapid wide streets connecting distances

Tehran 1970

- modern living and modern transportation system

- based on “neighborhood units”, “super highway” and “garden city” schemes

- society division based on class - utopia for the lower classes

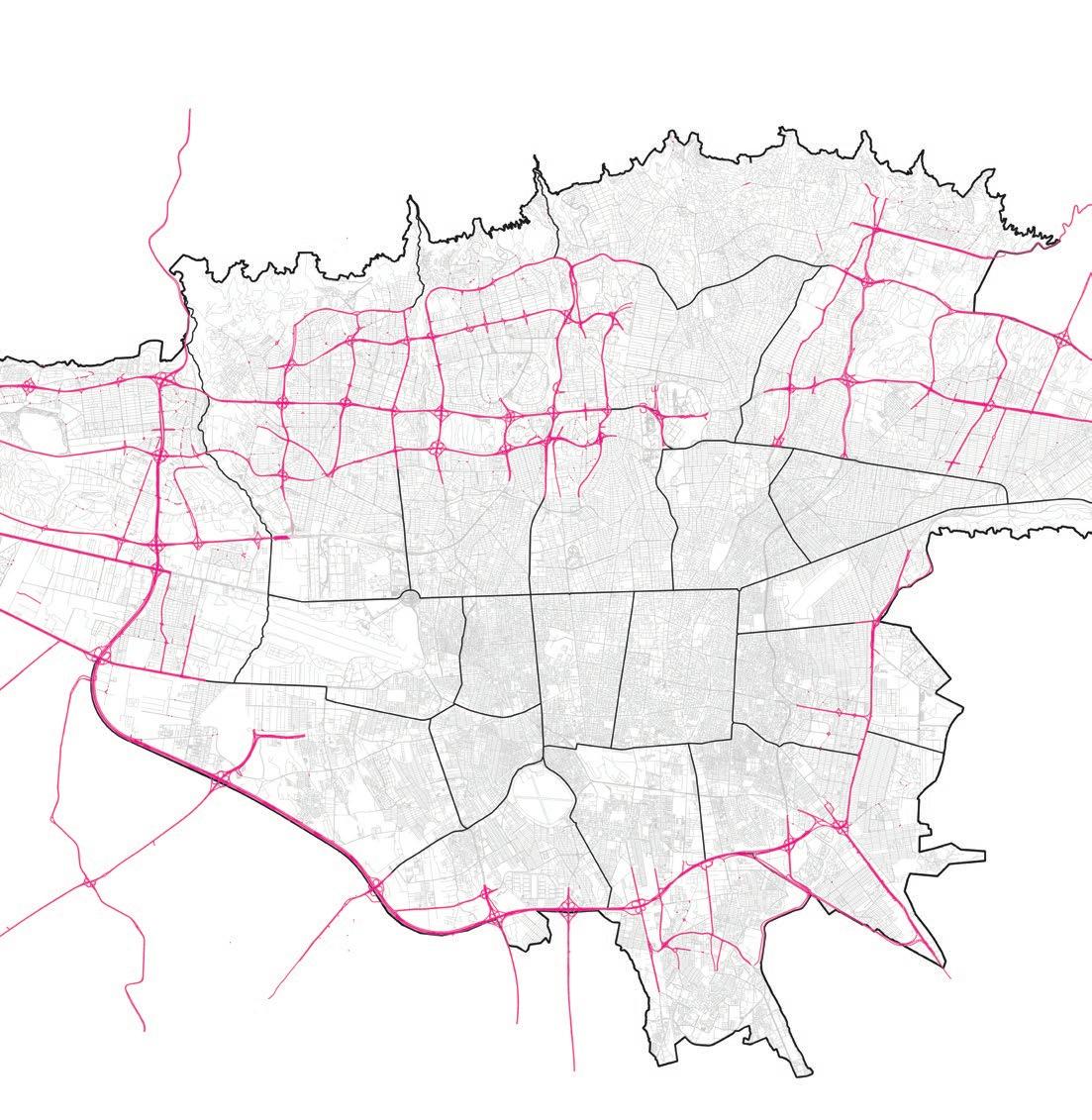

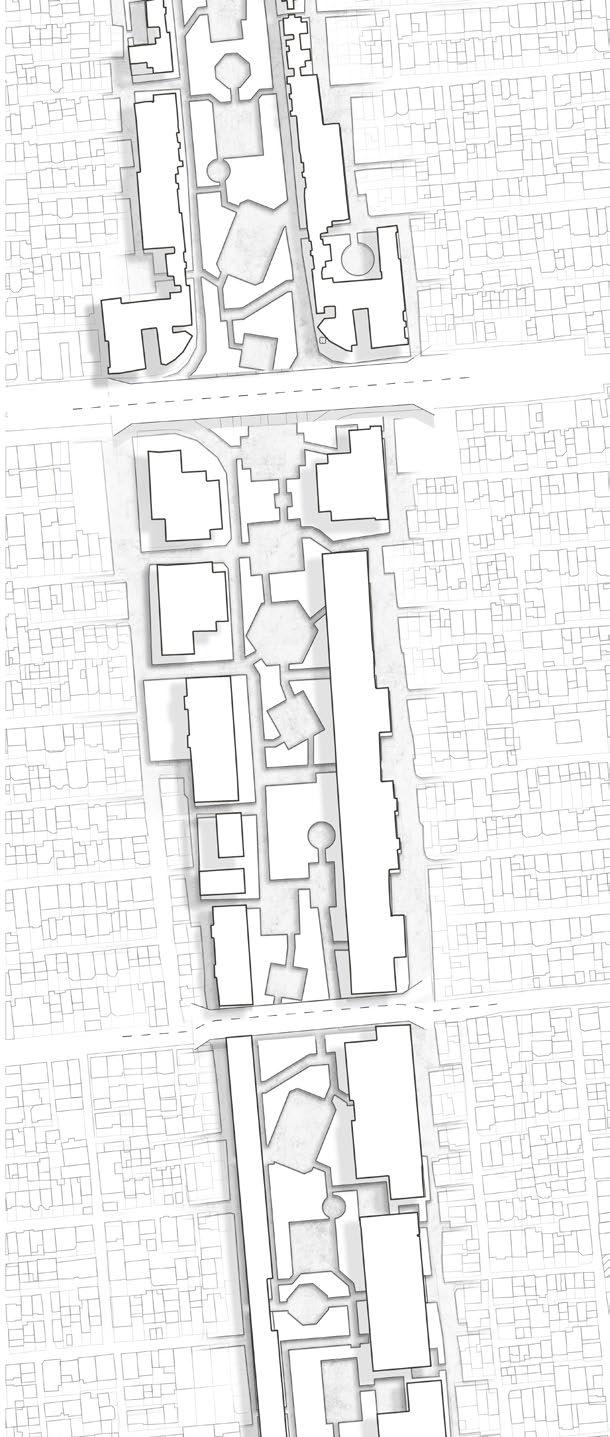

One of the symbolic examples of the municipality’s megadevelopment project is the Navab Highway, initially intended to bridge the north-south divide. Ironically, the highway itself has become a gap, with the impacted area still grappling with its repercussions – not just physically, but also socially.

Referred to by some locals as the “propaganda tunnel,” this passage links the heart of the city to the international airport. Over 7000 homes were demolished within a 50-meter span on each side of the planned 5.5-kilometer highway. The highway was intended to have rows of residential and often mixed-use highrises, designed by different architecture offices, lining its route. The Tehran municipality aimed to demonstrate urban modernization and prompt private sector involvement in the city’s regeneration.

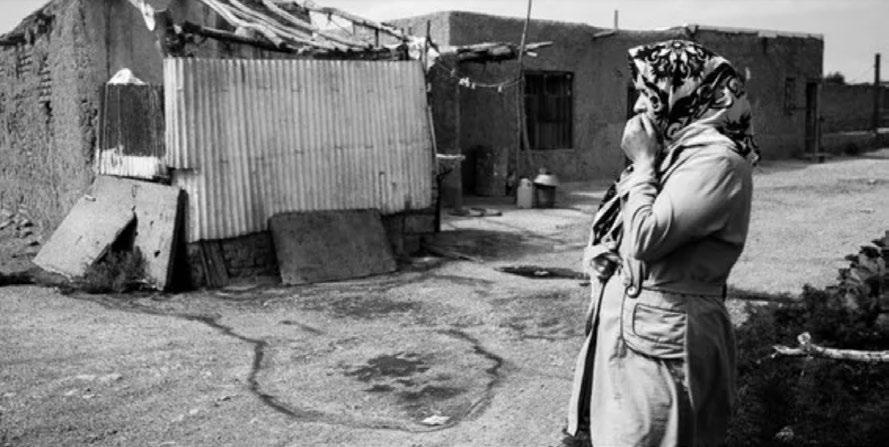

After over a decade of being criticized as Western and corrupt, the 1968 master plan became Tehran’s sole blueprint for urban development and a catalyst for market influences in the 1990s, including the Navvab project. However, deviations from the original plan happened, primarily driven by profit motives. Notably, two significant alterations were made: firstly, the 5-meter green buffer between the housing complex and the highway was replaced by slow roads; secondly, construction exceeding the height limits for residential areas was allowed next to the highway. According to “Evaluation of Navab Regeneration Project in Central Tehran, Iran” by Bahrainy and Aminzadeh: The total original neighborhood area was 800 hectares and included some twenty neighborhoods, with a population of 259,828 in 1996. The buildings were mostly 50 to 60 years old, representing the typical second Pahlavi architecture, built of masonry with 1 or 2 stories. The area was a cohesive social, physical, and cultural entity, consisting of several well-defined neighborhoods with strong family and social relations, a sense of belonging, and unity. As we will see, this well-defined social, physical, and functional organization of the neighborhoods has been destroyed by the Navab Regeneration Project.

Navvab’s close-knit neighborhood | 1990

demolition phase | 1994

completion | 2003

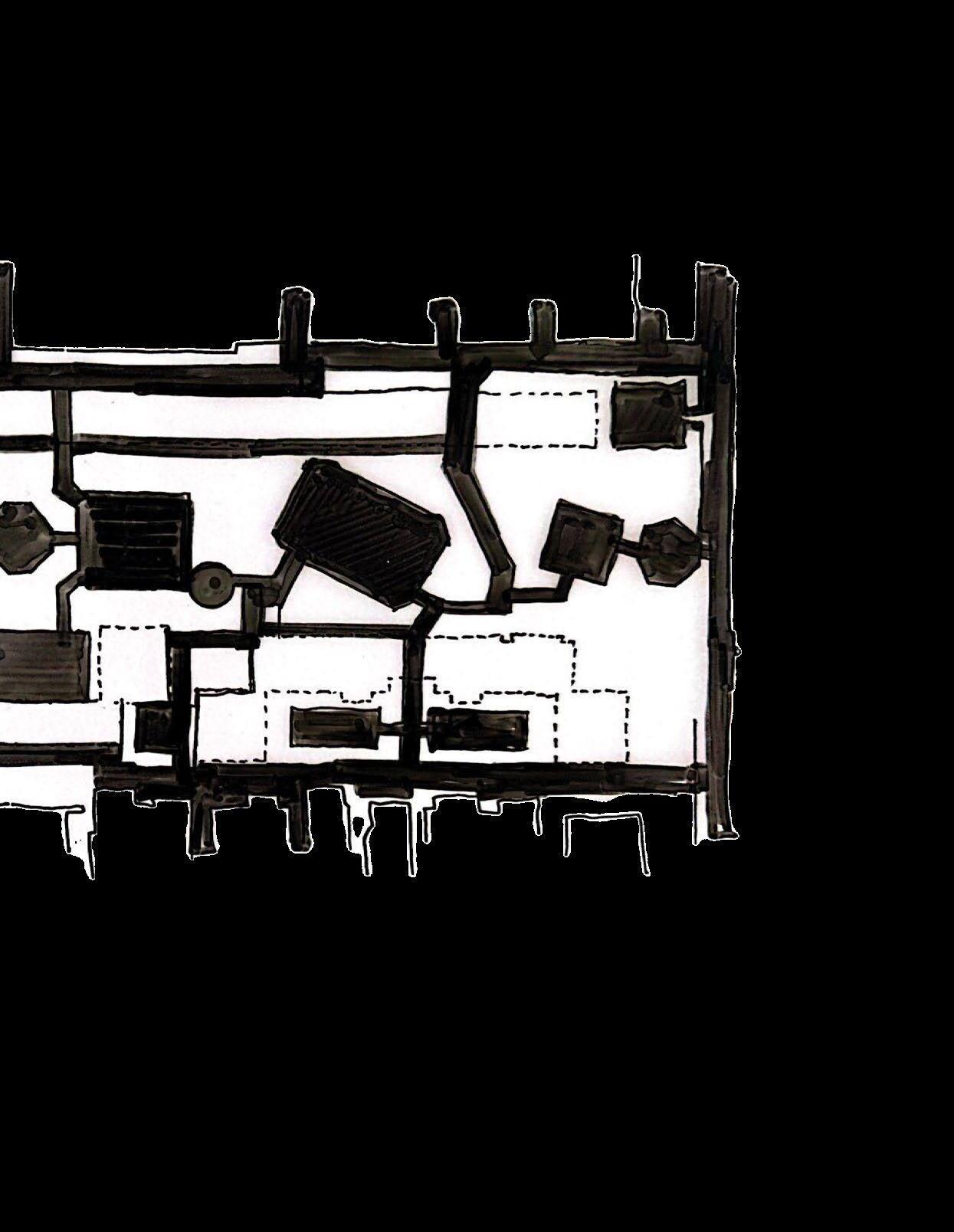

Actual implementation of the project started in 1994 and is expected to be completed in four years. The width of the constructed highway is between 50-60 m, and a depth of 10-30 m is considered for buildings on both sides of the highway. The project introduced more than 8500 new residential units to the area, most of which were below 75 square meters. The buildings, with a high density of up to 19 stories provide some 750,000 square meters of residential and 160,000 square meters of commercial and office spaces (Tehran Municipality, 1992b & 1996). These numbers show the extent of the intervention in the existing fabric of the city and the impact it has had and will continue to have, on the surroundings, the residents, and even the whole city.

Constructed from 1994 to 2003, the Navvab project earned recognition as the largest construction in the Middle East and garnered attention in neighboring countries’ newspapers. Despite this mega-project’s ambitious scope, its success was limited. It did establish swift highway links and nodes between opposite sides of the city, and introduced fresh commercial and office areas, along with a few parks in quieter lanes, yet the benefits largely halted there. In contrast, the negative consequences were considerable: the project divided a previously unified neighborhood, giving rise to numerous alleyways and obscured spots making it an ideal spot for illegal activities. Insufficient pedestrian crossings and problematic connectivity transformed the locale into an unsafe zone, especially for Weman. And the introduction of upscale buildings at higher prices led to the displacement of old residents who couldn’t return, ultimately causing gentrification.

What we now recognize as the Navvab Expressway originally began as a narrow local street, emerging during the urban expansion of the 1920s and 1930s. Initially dominated by housing, the area continued to prioritize residential structures compared to other programs. By 1970, the narrow street underwent expansion, transforming into a crucial northsouth connection, competing with the pre-existing wide street, Pahlavi Street.

In the 5-year plans outlined by the Tehran Construction and Planning Organization (TCP), there was a vision to elevate this street into a high-speed highway connecting the north and south. However, this proposal was not implemented until around 1990, involving modifications that included a 50-meter demolition and the eradication of housing to ensure the project’s financial viability.

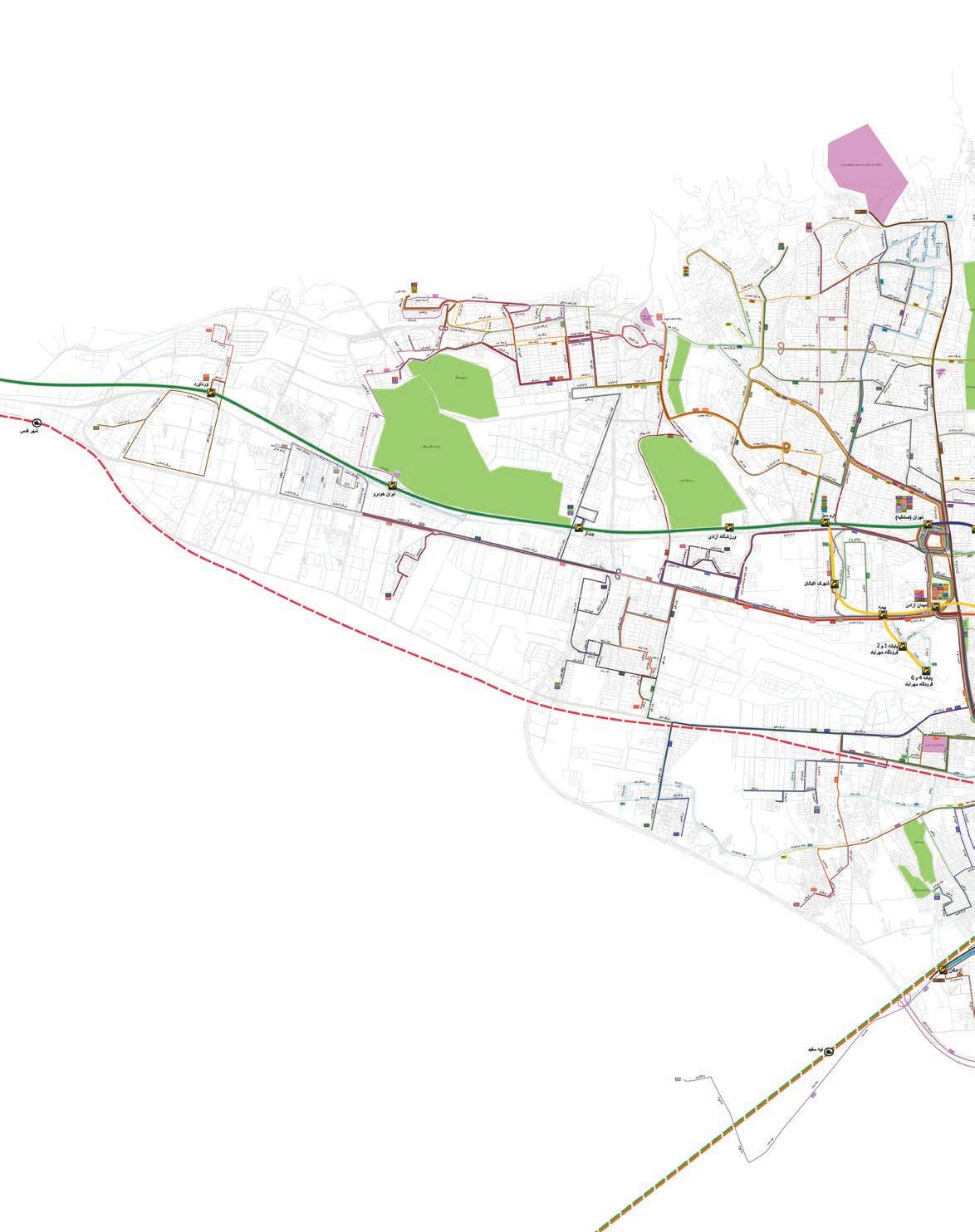

Today, the Navvab Expressway stands as a vital artery of the city, an unavoidable route to the city center, albeit dubbed by experts as an “open-air polluted tunnel.” Understanding the infrastructure’s context is facilitated by exploring key zones and buildings in its vicinity:

1. Enghelab Street: The Navvab Expressway is perceived as a perpendicular extension to the main east-west thoroughfare of the city, Enghelab Street, translating to “Revolution Street.” Enghelab Street has historically been a significant hub for arts, culture, and education. Its proximity to universities and important city buildings makes it a remarkable street where intellectuals gather, visit bookshops for the exchange of ideas, and contribute to the street’s distinctive character.

2. University of Tehran: One of the earliest developments in Reza Shah’s modernization approach was the establishment of the University of Tehran. This institution played a pivotal role in shaping the identity of Enghelab Street, emphasizing education and fostering bookshops in its vicinity.

3 & 4. Vicinity to Old Tehran: The Navvab Expressway’s proximity to old Tehran and the city’s history makes it a unique location, not only bringing out the worst traffic jams but also serving as a constant reminder of the city’s historical core. Despite attempts to relocate the city’s political and commercial center, it has largely remained in the same location.

5. Expansion of Enghelab Street and Tehran’s First International Airport: In the 1960s, as Enghelab Street expanded further west, plans were made to build Tehran’s first international airport. What was initially conceived as the city’s outskirts has now become an integral part of Tehran.

6. Since approximately 1950, and perhaps even earlier, a military base and airport were designated deep in the south of the city, likely situated at the outskirts during its inception. The proximity of this military installation to the direct northsouth access raises speculation that this adjacency was not a coincidence but rather a strategic decision intended to facilitate the control of the city in times of unrest or oppression. The deliberate choice of location suggests a purposeful consideration of logistical advantages for managing urban dynamics and potential disturbances within the city.

pedestrian bridge

expressway

local

automobil bridge

underground metro

block outlines

metro, bus or BRT station

pedestrian bridge

expressway

local lane

automobil bridge

underground metro

block outlines

metro, bus or BRT station

pedestrian bridge

underground metro

metro, bus or BRT station

pedestrian bridge

Tehran map | Navvab expressway highlited

Phase I

Phase II

Phase III

Phase IV

Phase V

Plannig and phahsing

Neighborhood impact

Inactive Ground Floors

North-south high-speed car access lane

East-west high-speed car access lane

Local lane

Boston’s Central Artery Highway | 1990

Amsterdam Museumplein | 1987

Amsterdam Museumplein | 2024

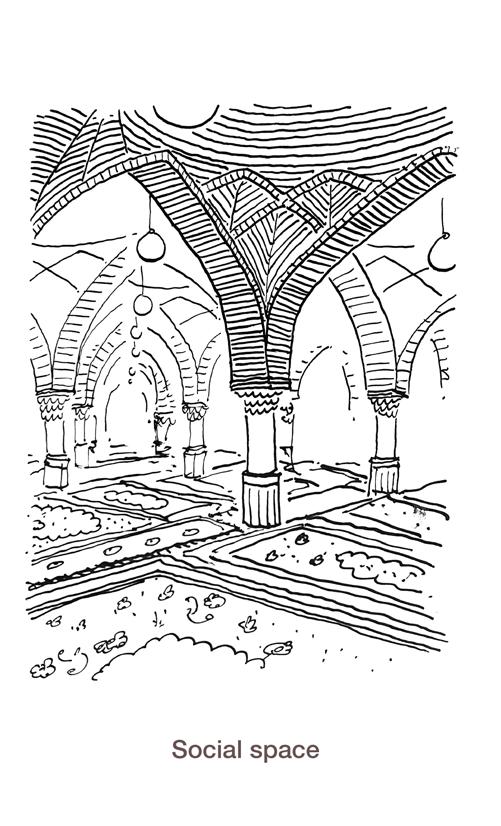

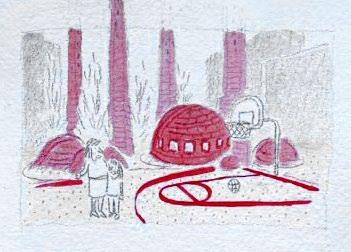

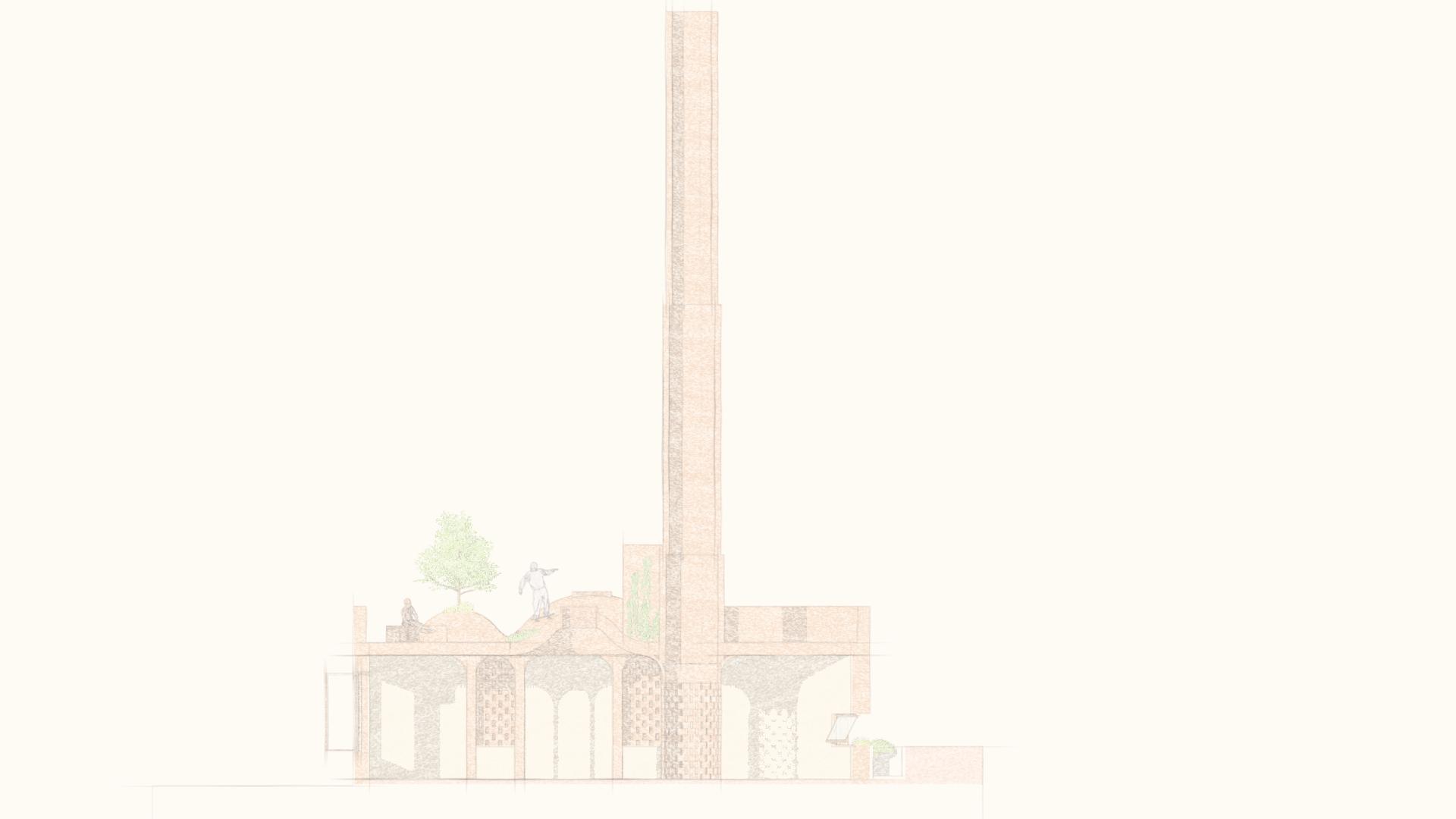

The spatial arrangement of Persian bazaars is based on a carefully woven network of corridors and courtyards that creates both continuity and hierarchy. Linear passageways form the main arteries, often aligned with the city’s central routes, while smaller side alleys branch off to more specialized sections. Along these corridors, courtyards and caravanserais act as larger nodes, offering spaces for rest, storage, and social interaction. Domed intersections mark important crossings, serving as focal points where multiple routes converge. This interplay of narrow passages and expansive courtyards generates a rhythm of compression and release, making the bazaar not just a marketplace but a layered urban network that balances movement, pause, and encounter.

Persian bazaars are defined by their strong spatial and visual qualities, where scale and rhythm guide both movement and experience. Long corridors are punctuated by domed intersections and caravanserais that create pauses and landmarks, while vaulted ceilings and patterned brickwork shape light and shadow into a dynamic visual language. Variations in height, proportion, and decoration not only enrich the atmosphere but also signal transitions between different sections. Through these spatial cues, the bazaar directs orientation and flow, turning commerce into an architectural journey.

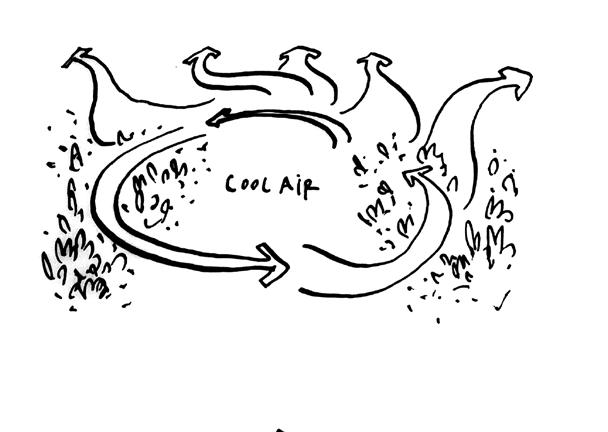

Skylights/Hotno

These bazaars are often covered with vaulted brick ceilings and domes that regulate temperature, providing coolness in the scorching summers and warmth in winters. Natural light filters through small openings, creating a rhythmic play of shadow that enhances both ambiance and energy efficiency. The spatial layout—linear passages, caravanserais, and courtyards—caters to trade, social interaction, and even religious practices, making the bazaar not just a marketplace but a cultural and civic hub. This blending of practical design and social function exemplifies how vernacular architecture shapes enduring urban

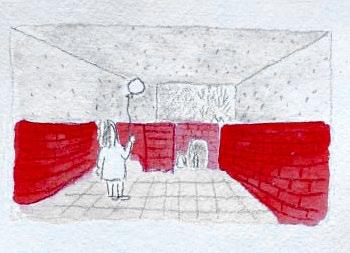

Entering the bazaar is possible through a series of entrances, penetrating the existing buildings and bridging over the leftover spaces, which will transform into pocket parks. This design creates an ideal crossover right next to a green, intimate-scale space.

Making the back street pedestrian-friendly.

Using the leftover space as an opportunity to create a seamless connection.

Using the leftover space as an opportunity to create a seamless connection and realizing green spaces.

Connecting through the existing building.

Navvab Bazaarway aims to create meaningful, calm urban spaces where neighborhoods can develop and flourish. Through layers of green spaces, considerate programming, and high-quality urban spaces, the project integrates passive cooling systems and creates a maze-like layout for the community to enjoy on a daily basis. Additionally, modernized versions of Persian motifs, with their repetitive patterns, have been incorporated to recreate or remind viewers of the traditional bazaars.

For centuries, Persian bazaars have withstood the test of time. They are more than marketplaces. They are living urban fabrics where program, form, sense of place, pedestrian life, and sustainability come together to create coherent, authentic spaces.

This is why bazaars are at the heart of the Navvab Bazaarway research. By learning from their spatial logic, vernacular resilience and combining it with modern planning and green mobility strategies, a meaningful alternative to the expressway can be achieved. One that repairs the broken fabric and respects the language of its place.