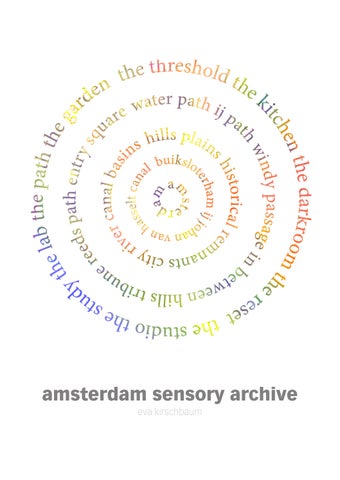

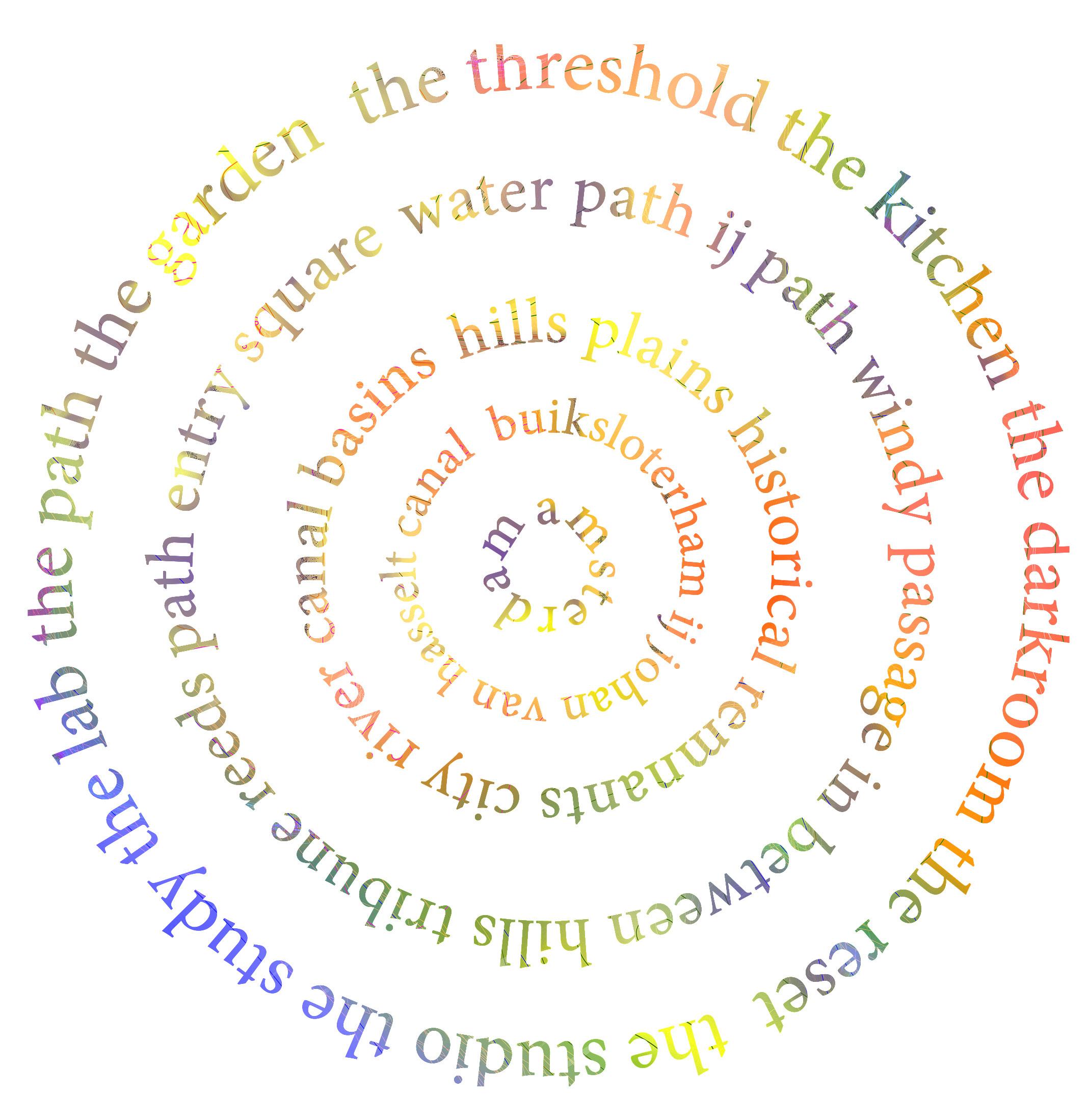

amsterdam sensory archive

eva kirschbaum

“Places are sensed not just with the eyes, but with the skin, the ears, the breath.”

after Jean-Luc Nancy

COLOPHON

University Amsterdam University of the Arts

Faculty Academy of Architecture

Department

Master of Architecture

Project Graduation thesis Study year 2024-2025

Graduation committee

Machiel Span (mentor) Brigitta van Weeren Lindsey van de Wetering

Additional members for the exam Jeroen van Mechelen Quita Schabracq

Student Eva Kirschbaum

Telephone number 06-27861108

Email evgeniakirschbaum@gmail.com

Published version 01 july 2025

manifesto in fragments & futures

This project begins where vision ends— in the language of materials, the weight of breath, the knowledge stored not in books, but in the body.

We do not archive the image of the city. We archive its feeling: the murmur of wood in spring, a warm doorhandle, the scent of rain in grass.

The city is not an object. It is rhythm. Memory. Stillness by water where no one watches, yet something unfamiliar becomes known.

Architecture must hold this— what we forget: the texture of a street, the echo in concrete like a second voice.

The Archive does not display. It listens. It gathers what’s usually unheard— not to freeze, but to let it live again, in other bodies, in other time.

Here, nothing is only for looking. Walls are for leaning, paths for wandering, doors for smelling the garden before you open them. There is no choreography—only invitation.

We design with what is already here: wind, slowness, traces of former use. We do not erase—we build with it.

The industrial past becomes a tactile present. Everyone belongs in this Archive— especially those left out of buildings that forget to be felt.

We believe knowledge lives beyond text. Perception is political. The city is not whole until all its senses are heard.

This building will not blaze. It will linger. It will breathe. And if you let it— it will remember you, too.

where it began

As a child, I often noticed details others overlooked: the sharpness of a sound, the discomfort of certain textures, the overwhelming pull of specific smells or lights. These sensations were intense but invisible to those around me. Quietly, I adapted — learning to navigate spaces that often felt overwhelming.

Over time, I’ve learned that I live with ADHD and sensory hypersensitivity — a realization that helped me make sense of my intense perception of the world. It also reshaped how I approach design. I began asking different questions: What does overstimulation feel like spatially? What kinds of architecture support people who experience the world differently?

My years as a professional sailor taught me to rely on full-body awareness. On the water, navigation isn’t just about sight — it’s about reading wind, balance, temperature, and rhythm. This embodied sensing shaped my understanding of space and place.

In contrast, I was struck by how architecture approaches design so differently. It often overlooks the other senses — focusing on how spaces look, rather than how they feel, sound, or smell. But what happens to space once vision is no longer central? Is there something beyond sight?

Working with experiences of people with visual impairments helped me confront this question directly. Their ways of navigating space through touch, sound, and spatial memory revealed just how much architecture excludes when it focuses solely on vision. It leads to uncomfortable spaces, overstimulation, and an unbalanced experience of the built environment.

Their insights challenged me to rethink my assumptions and explore what architecture could become if we designed through all the senses — not just for beauty, but for presence, orientation, comfort, and connection.

This project became both deeply personal and inherently collective — an exploration of sensory diversity’s potential to expand architecture, and a search for designs that don’t just display, but truly respond.

Image: Olafur Eliasson, Din blinde passager (2010), Tate Modern, photo by Anders Sune Berg

introduction

In today’s built environment, architecture is overwhelmingly visual—designed, represented, and experienced primarily through the eye. This ocular-centric approach limits spatial richness and excludes those who perceive the world differently. For example, people with visual impairments often navigate spaces never designed with their experience in mind. And yet, these same individuals frequently engage with space through heightened sensitivity to texture, sound, movement, temperature, rhythm, and scent—senses many of us have learned to overlook.

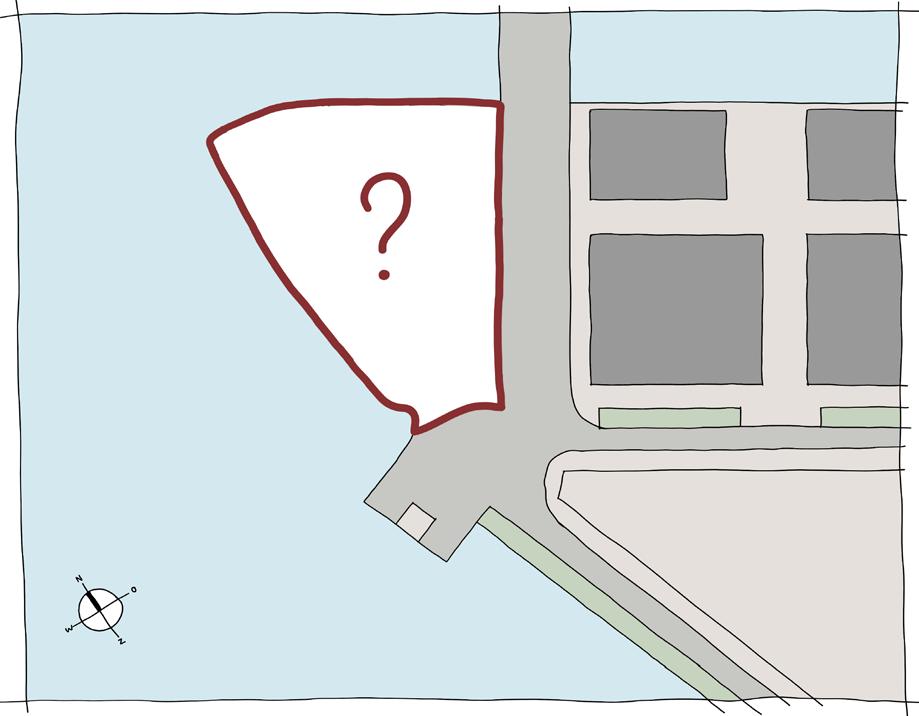

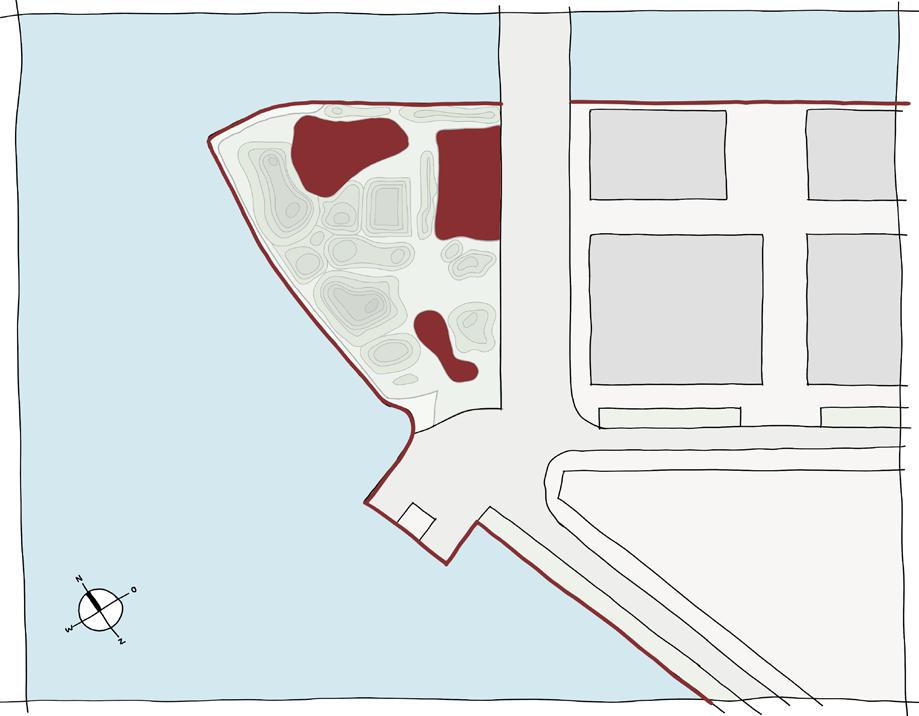

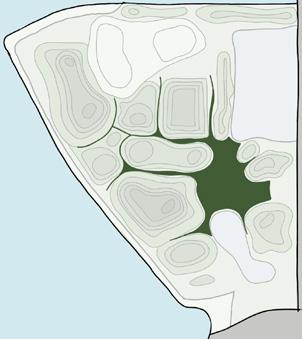

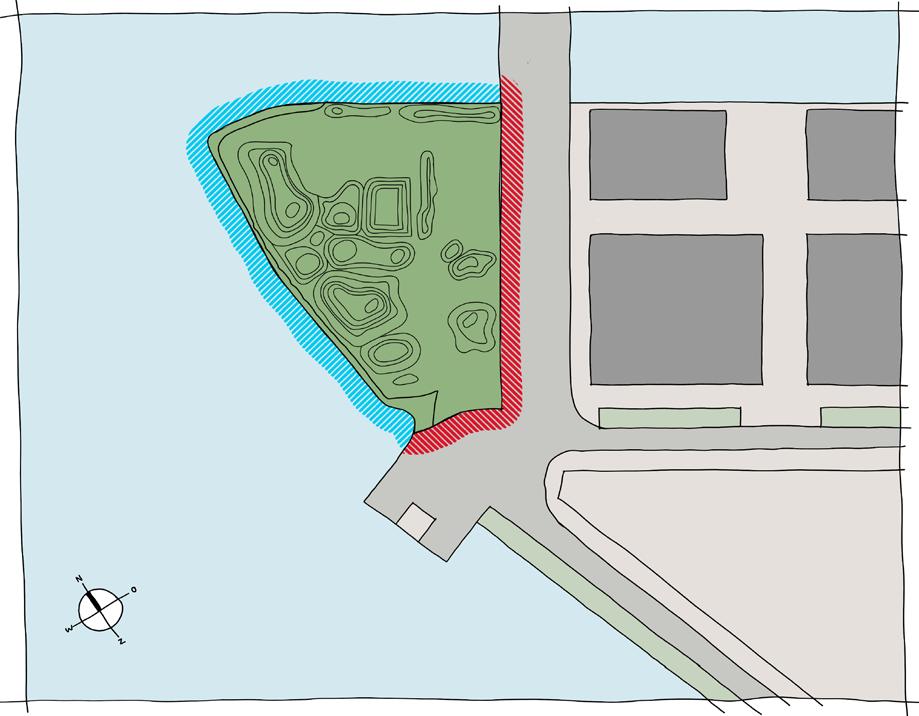

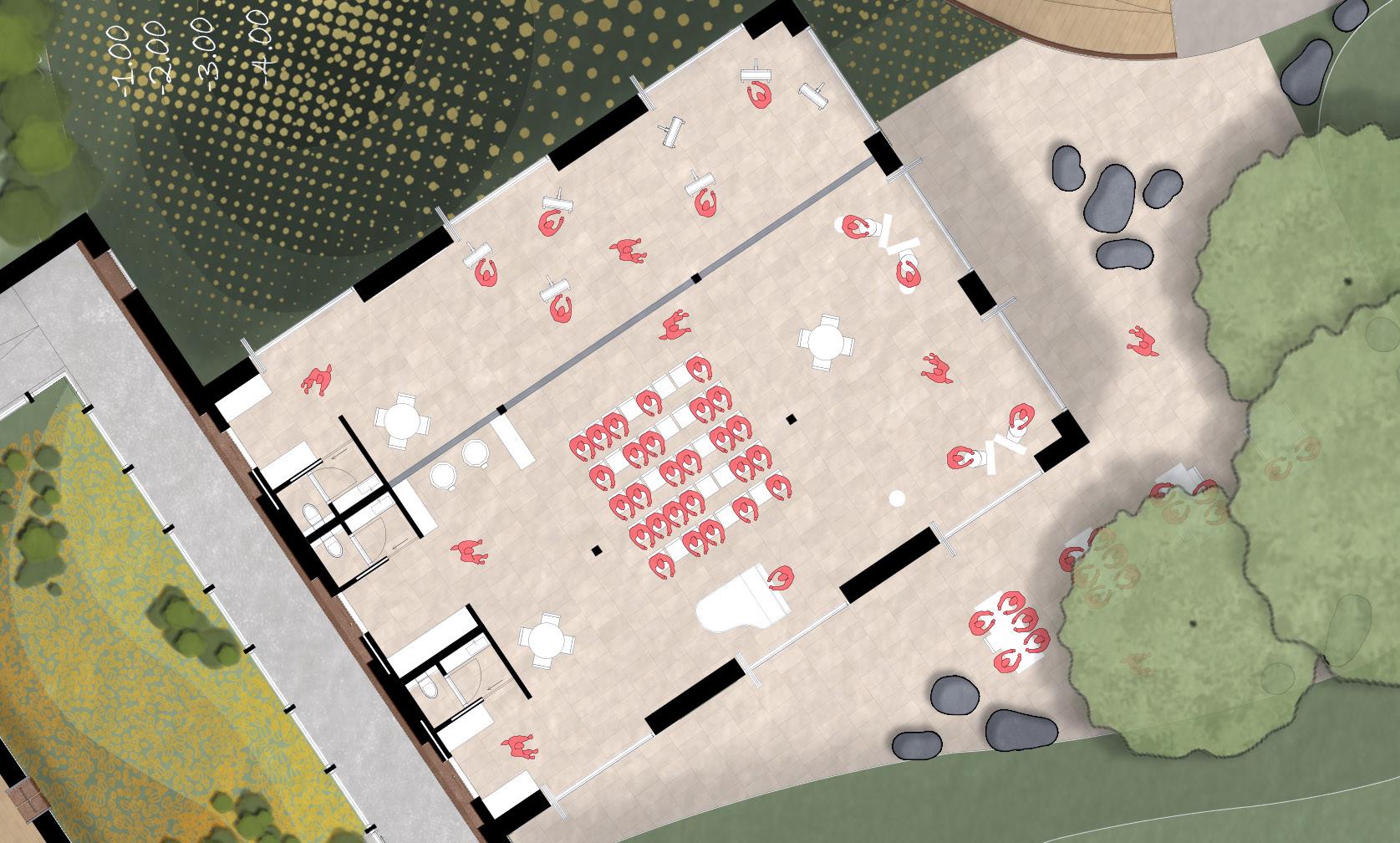

The Sensory Archive of Amsterdam challenges this imbalance. It is neither a conventional library, museum, nor archive, but a new civic typology built around multisensory experience. Informed by the lived expertise of those who sense space non-visually, it does not aim to compensate for a lack of sight, but to expand spatial perception for all. It offers a shared framework for learning, curiosity, and inclusion. Located in Buiksloterham—on a post-industrial peninsula between the IJ River and the Johan van Hasselt Canal—the project reclaims a site marked by pollution, disuse, and layered ground conditions. While the surrounding area is being redeveloped, this plot remains physically raw and ecologically complex. Rather than erase its history, the design builds upon it.

The Sensory Archive is composed of two interconnected parts:

• Archive Park, a new public landscape, serves as both threshold and spatial prologue. It includes the Entry Square, a winding IJ Path, the enclosed Wind Passage, a soft Reed Field with a Tribune, and a secluded space among the In-Between Hills. The planting strategy is seasonal and site-responsive—wild, tactile, aromatic, and inviting to both people and wildlife. The park does not follow the rigid axis of the city, but moves according to a sensorial logic.

• The Archive Building unfolds as a sequence of experiential zones, each defined by distinct materials, orientations, and dominant sensory qualities:

o The Threshold: a pavilion-like entry with a floating timber roof and basalt edge.

o The Kitchen: a greenhouse-inspired space for scent, taste, and seasonal growth.

o The Darkroom: a downward-sloping, enclosed space wrapped in charred timber, designed for tactile and proprioceptive awareness.

o The Reset: an open-air basalt room with a reflective water basin and polished bench—a space for pause and grounding.

o The Studio: a tall, filtered-light space for sound, listening, and subtle activity.

o The Study: a contemplative zone with river views, layered books, and gentle light reflections.

o The Lab: a semi-industrial workshop for experimentation, sensory documentation, and collective contribution.

o The Path: a continuous concrete floor with a tactile copper line for navigation and a Memory Wall for visitors to leave traces of their presence.

Each zone is curationally flexible, able to adapt to changing narratives, themes, and contributors. Together, they form an archive—not of static knowledge, but of memory, sensation, and lived experience.

In a time marked by overstimulation, disconnection, and exclusion, the Sensory Archive offers something else: a building that listens, remembers, invites, and welcomes difference. It does not dictate how it should be used—it asks how it might be sensed. It offers a new way of engaging with architecture, the city, and the fundamental act of feeling at home in space.

setting the stage

The first part of this book builds the foundation for the project. It begins with a manifesto that critiques the visual bias in architecture and asks what happens when other senses are brought to the forefront. Through theory, reflection, and method, it introduces the key themes of inclusivity, sensory access, and embodied design. These chapters frame the questions that shaped the archive.

beyond vision

challenging the ocular bias in architecture

For centuries, vision has been regarded as the most noble of the senses. From ancient Greek philosophers to contemporary thinkers, sight has been closely linked to reason, intelligence, and even the soul. Phrases like “seeing is believing” and “the light of reason” reveal just how deeply ingrained the dominance of vision is in our cultural understanding. In modern society, this ocular-centric worldview is amplified by technologies such as photography, television, and digital media. Our daily lives are inundated with images that are primarily visual, transforming sight into a passive, almost detached experience. We see the world, but how often do we truly feel it, touch it, or experience it through sound or smell?

In architecture, this prioritization of vision is similarly pervasive. Historically, many architectural philosophies, particularly modernist approaches, have celebrated the aesthetic beauty of buildings, focusing almost exclusively on the visual. Architects like Le Corbusier famously asserted that “I exist in life if only I can see,” underscoring the importance of vision in understanding the world around us. Even today, architects such as Philip Johnson continue to emphasize visual appeal, often to the detriment of other sensory experiences. A building’s visual identity is paramount, but what about the experiences that can’t be seen?

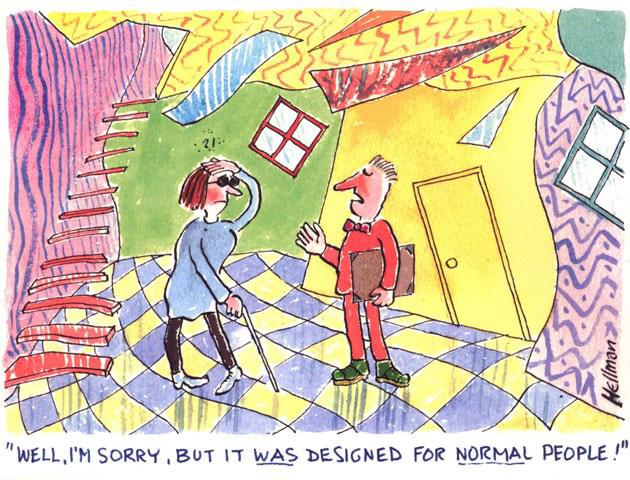

This overemphasis on vision is problematic when we consider people who experience the world differently, such as those with visual impairments. Architecture, with its heavy reliance on materials like glass, steel, and concrete, often fails to engage other senses like touch, sound, and smell—senses that are vital to those who navigate the world without sight. Take, for instance, the comparison between the Beurs van Berlage in Amsterdam and the Beeld en Geluid building in Hilversum. The Beurs van Berlage, with its rich tactile and auditory experiences, offers a multisensory space that invites exploration through more than just the eyes. In contrast, Beeld en Geluid, with its modern design, feels cold and uniform, disconnected from the senses that go beyond vision. This disparity highlights a broader issue: the failure of modern architecture to design for those who rely on senses other than sight, creating spaces that are less inclusive and, in some cases, isolating.

The exclusion of diverse sensory experiences is not only a matter of accessibility for people with disabilities; it also limits the potential richness of human experience in architectural spaces. When we focus exclusively on vision, we miss out on the full spectrum of sensory interaction that can deepen our connection with the built environment. We diminish the emotional depth and lived experience that can be felt through sound, texture, or scent. As a society, we’ve forgotten how to fully engage our senses in the way we move through and experience our surroundings. It is time to challenge this ocular-centric view of design.

This is where the Sensory Archive comes in. By rethinking the way we approach architecture, we can move beyond the limits of visual design and create spaces that engage the full range of human senses. My project seeks to explore how architecture can be designed not only for visual appeal but for an immersive multisensory experience that is inclusive of all people, regardless of their abilities. Through this project, I aim to promote a shift in architectural philosophy, one that considers the experiences of people who navigate the world differently and enriches the experience for everyone.

beyond access the role of inclusive design in architectural practice

The discourse around disability and architecture has evolved over time, with a growing emphasis on creating environments that are accessible to all. However, while the terms “inclusive,” “universal,” and “accessible” are often used interchangeably, they are not synonymous. It is crucial to understand the fundamental differences between these concepts to ensure that we are designing spaces that truly meet the needs of diverse populations, particularly those with disabilities.

Accessible design typically refers to meeting legal standards and ensuring that spaces are physically usable by individuals with disabilities. This includes features such as ramps, wide doorways, and accessible bathrooms. While essential, accessible design often focuses more on technical compliance than on creating a truly inclusive environment. It addresses the minimum requirements for people to safely navigate a space but may not take into account the broader needs of users, such as emotional comfort, social interaction, or sensory engagement.

In contrast, inclusive design goes beyond merely meeting physical requirements. It is an approach that seeks to integrate the needs, preferences, and perspectives of all people—regardless of their abilities—into the design process. Unlike accessible design, which primarily addresses the physical aspects of a space, inclusive design considers the social and emotional dimensions. It creates environments that are not only physically accessible but also welcoming, engaging, and empowering. This means designing spaces where people with disabilities do not just have access but are fully included in the experiences the space offers.

Inclusive design is not about creating a one-size-fits-all solution. Instead, it is an ongoing, iterative process that acknowledges the diversity of human experience and strives to eliminate barriers—whether physical, social, or psychological—that may prevent individuals from fully participating in society. This approach recognizes that a truly inclusive space is one that is constantly evolving, responding to the needs and experiences of those who interact with it.

One common misconception is that universal design is the same as inclusive design. While universal design strives to meet the needs of the greatest number of people, it often assumes a “one-size-fits-all” approach, which may not be adequate for everyone. For example, features like wide doorways or low countertops might work for many people, but they may not address the unique needs of people with specific disabilities or cultural backgrounds. Inclusive design, on the other hand, recognizes that solutions must be adaptable, flexible, and responsive to the diverse needs of the community.

As we design the Sensory Archive, it is crucial to embrace the principles of inclusive design. This project goes beyond physical accessibility, focusing on creating an environment that invites participation, fosters social connections, and engages all

the senses. The sensory zones within the archive, designed for people with and without visual impairments, are not just functional spaces but are integral to the experience of the space itself. Each zone is intentionally crafted to invite exploration through tactile, auditory, and olfactory experiences, reflecting the diverse ways people experience the world.

For example, in The Kitchen, visitors can interact with a sensory garden that emphasizes aromatic plants and flavors, encouraging them to experience nature beyond its visual qualities. In contrast, The Darkroom provides spaces that highlight texture, movement, and sound, offering opportunities for visitors to explore through touch and hearing. These zones are not only accessible; they are designed to foster a deeper understanding of how people experience space, creating an environment where all visitors can feel a sense of belonging, participation, and connection.

Inclusive design is not without its challenges. What works for one group may not work for another, and the tension between the needs of different users can sometimes lead to difficult design decisions. For instance, certain tactile paving may benefit people with visual impairments but may pose challenges for people with mobility issues. However, these challenges should not discourage us from striving for a more inclusive approach. Rather, they highlight the need for thoughtful, iterative design that continually adapts to the needs of its users.

In the case of the Sensory Archive, inclusive design is not a final destination but an ongoing process that values diverse perspectives and embraces complexity. The spaces are designed to evolve and adapt, ensuring that they serve not only the users they were originally intended for but also the wider community. Through this approach, the project aims to break down social barriers, challenge traditional design philosophies, and offer new ways of experiencing architecture—ultimately fostering a sense of belonging for everyone, regardless of ability.

designing for multisensory inclusion

insights from visual impairment experiences

This chapter draws from a series of conversations I had with individuals living with a range of visual impairments, including some with additional sensory disabilities. Through these interviews, I came to understand the nuanced ways in which people perceive, interpret, and navigate the built environment when vision is limited or absent. Their reflections offered powerful insights—not only into the barriers they face—but also into the strategies they use to orient themselves, connect with others, and find moments of comfort in everyday spaces.

What follows is a synthesis of these personal accounts. Rather than generalizing or simplifying, this chapter aims to translate their diverse experiences into clear, practical considerations for design. These insights form a crucial part of the conceptual framework for the Sensory Archive, informing a spatial approach that embraces difference, supports autonomy, and creates multisensory environments where all bodies and senses are welcomed.

• Navigating Social Spaces Through Sound and Touch

For many visually impaired individuals, social interaction presents a challenge not due to a lack of desire, but because of barriers in perceiving others nearby. Sound cues like footsteps and voices become vital for sensing the presence of people. However, materials such as carpet, often assumed to be comfortable, can dampen these cues, inadvertently increasing social isolation. Designing with acoustics in mind—ensuring that footsteps and voices carry clearly—can foster spontaneous encounters and a greater sense of community.

• Balancing Light and Contrast for Enhanced Perception

While vision may be limited or absent, many retain some ability to perceive light and shadow. Spaces that are overly bright can cause blinding glare and reduce the contrast needed to distinguish objects, while dimly lit areas obscure spatial cues altogether. Thoughtful lighting strategies that provide balanced illumination and emphasize contrast between architectural elements, furniture, and pathways are vital for safe, intuitive navigation.

• Harnessing the Power of Multisensory Cues

Visual information is only one part of spatial awareness. Aromas, sounds, textures, and even temperature shifts become powerful guides for orientation and wayfinding. The smell of fresh bread or spices, the hum of a bustling market, or the change in floor texture underfoot all contribute to an enriched sensory map. Designing environments that offer diverse, meaningful sensory signals can empower visually impaired users to explore spaces confidently and independently.

• Optimizing Social and Work Environments for Focus and Connection

Large, open-plan areas with excessive noise present challenges for concentration and communication. Smaller group settings with limited occupants and strategically chosen seating locations support better engagement and reduce sensory fatigue.

• Supporting Mobility and Service Animal Needs

Navigational aids such as canes and service dogs are essential companions, but their effectiveness depends on considerate environmental design. Surfaces like metal grates can be uncomfortable or unsafe for service animals, while narrow or cluttered pathways limit freedom of movement and increase stress. Creating stable, varied-texture flooring and sufficiently wide, unobstructed routes ensures safe and comfortable mobility for all users.

• Ensuring Safety Through Clear Spatial Logic

Unfamiliar spaces can pose safety risks without clear orientation aids. Predictable layouts with straight walls and corners provide a sense of direction, while curved or irregular shapes can cause confusion. Integrating tactile guiding lines, handrails, and verbal or tactile descriptions enhances spatial comprehension and reduces dependency on sighted assistance.

• Prioritizing Acoustic Comfort and Quiet Zones

Acoustic design is a critical, often overlooked component of accessibility. Loud, chaotic environments can overwhelm the auditory senses, which are heavily relied upon by visually impaired individuals. Quiet zones with good acoustics enable relaxed conversation and focus, providing essential respite from sensory overload.

• Utilizing Color Contrast Thoughtfully

For those with partial vision, high-contrast colors can make navigation easier and safer. However, a lack of contrast between walls, doors, and floors can obscure important features and create hazards. Thoughtful use of color contrast helps visually impaired users recognize key elements within a space, enhancing both accessibility and confidence.

By integrating these insights into the Sensory Archive’s design, the project moves beyond visual assumptions to embrace a holistic multisensory approach. This fosters environments where people with visual impairments can navigate independently, connect socially, and experience a rich tapestry of sensory information—true inclusion through design.

designing for all senses

strategies for multisensory and inclusive architecture

To design inclusively is to recognize that space is not experienced through vision alone. Our perception of architecture is shaped by an intricate web of senses — touch, hearing, smell, taste, temperature, balance, movement, and memory — which do not function independently, but in relation to one another. In this system, no single sense is dominant, and no body experiences space in exactly the same way.

This approach does not treat multisensory design as an aesthetic layer or added accessibility feature. Instead, it sees the senses as spatial tools — each one contributing uniquely to how we navigate, understand, and remember a place. More importantly, these senses form meaningful pairs or groupings:

- Touch is heightened by temperature

- Sound deepens awareness of distance and rhythm

- Smell anchors memory and spatial familiarity

- Taste and scent co-create atmosphere

- Proprioception and balance shape how we move through space

- And vision, while powerful, often follows what the body has already perceived

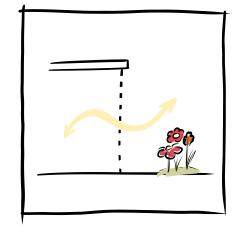

The diagram accompanying this text represents the relational field of perception: a network of interactions where sensory experience is not linear, but dynamic. It reflects a design methodology where space is not built around visual impressions, but through sensory layering, overlap, and rhythm. This method fosters environments that are more inclusive, more participatory, and more emotionally resonant.

For individuals who navigate the world differently — such as those with visual impairments — this intersensory model is not abstract. It is lived knowledge. These users may rely more on texture, echo, airflow, smell, or ground resistance to understand their surroundings. Rather than designing for a “universal” user, multisensory architecture recognizes the body as plural, shifting, and relational.

The aim is not to isolate each sense in a separate space, but to design experiences that unfold through combinations: touch with movement, smell with memory, sound with light. These sensory couplings create richer spatial narratives, support cognitive mapping, and encourage slower, more attentive inhabitation.

documenting the multisensory city

Contemporary urban archives are predominantly visual and textual, shaped by a long-standing bias that privileges sight and written record over embodied experience. Yet cities are not only seen and read—they are smelled, heard, touched, and felt. From the sound of tram bells and church chimes to the texture of cobbled streets, the aroma of industrial production, or the shifting microclimates of parks and canals, sensory experiences shape everyday urban life and memory in fundamental ways. As cities like Amsterdam undergo rapid transformation, these sensory markers—often ephemeral and difficult to document—are disappearing. A sensory archive offers a critical framework for preserving these intangible yet deeply meaningful aspects of urban experience.

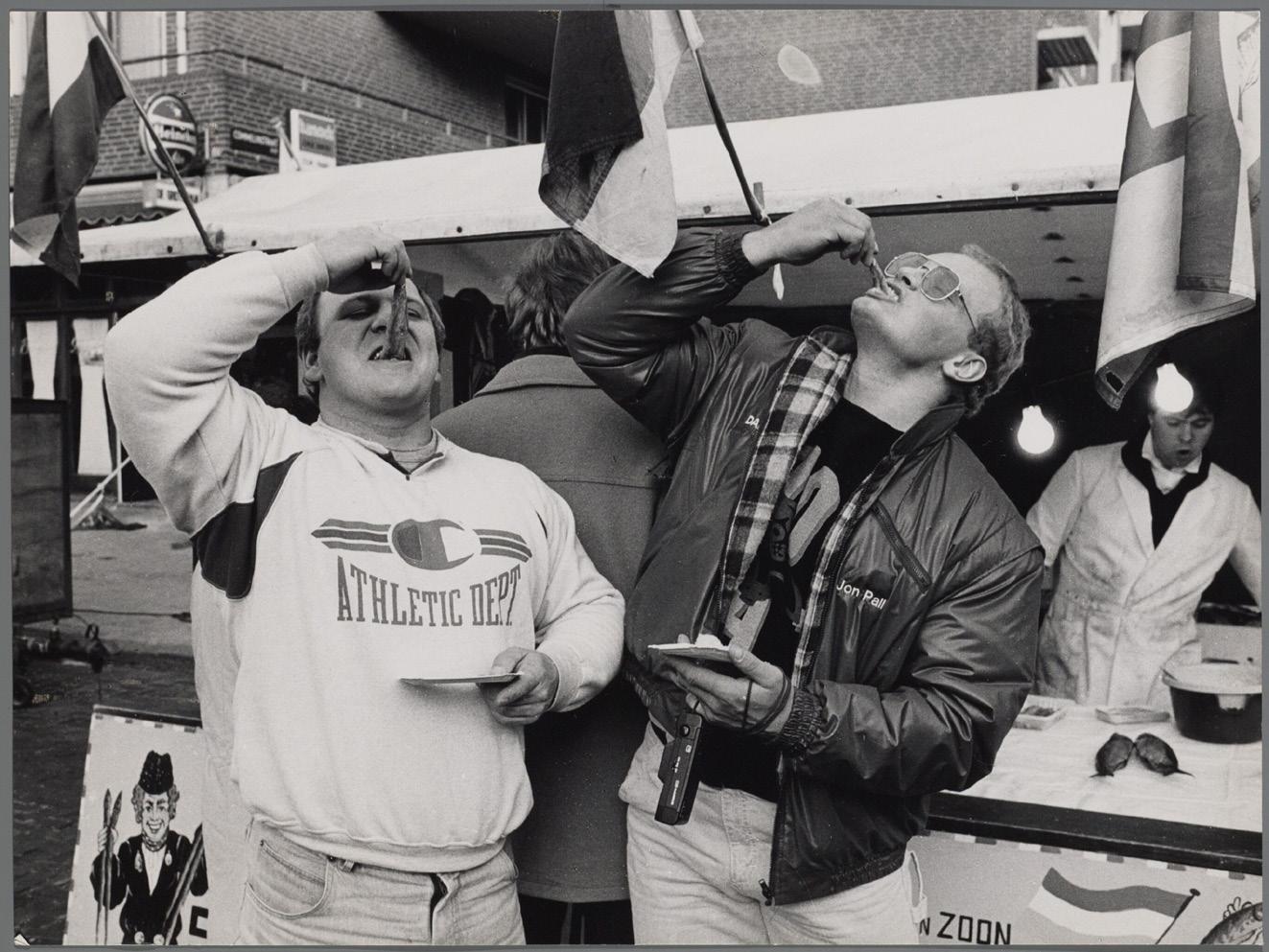

Urban memory is inherently multisensory. Anthropologist David Howes emphasizes that “the sensorium is a cultural formation,” shaped not only by individual perception but by shared practices, technologies, and spatial configurations that vary across time and place.This notion is particularly relevant in Amsterdam, where different neighborhoods historically offered distinct sensory environments. Industrial zones produced recognizable smells and mechanical rhythms; residential streets echoed with domestic activity; markets and festivals brought bursts of sound, scent, and motion. These layers of sensory input fostered both spatial orientation and emotional attachment to place.

The olfactory landscape of Amsterdam, for instance, once included the sweet scent of cocoa from the Blooker factory, the sharp tang of ammonia near the Westergasfabriek, or the earthy aroma of wet leaves in the Vondelpark. Similarly, the acoustic environment has changed dramatically—from the clatter of shipyards in the Eastern Docklands to the hum of electric trams replacing older, noisier transit modes.Tactile memories, too, persist in local consciousness: the smooth stone of canal bridges, the shifting gravel of alleyways, the cool metal of railings and fences that once marked industrial perimeters. Such multisensory experiences offer an embodied sense of time and place, and their disappearance erodes not only personal memory but collective identity.

Recent projects underscore the potential of sensory archives to preserve these dimensions. City Sniffers: A Smell Tour of Amsterdam’s Ecohistory, developed by Odeuropa, maps lost and lingering scents—from linden blossoms to canal odors—using a Rub’n’Sniff guide that activates sensory memory through smell.

Likewise, Mediamatic’s Olfactory History of Oosterdok investigates how scent has informed the economic and ecological evolution of the docklands, combining sensory walks with historical interpretation.Meanwhile, sound archives like Soundtrackcity collect everyday urban sounds—from pedestrian crossings to church bells—creating an evolving database of Amsterdam’s sonic atmosphere.

These initiatives show that sensory memory can be recorded, reactivated, and shared through interdisciplinary methods. The Sensory Archive of Amsterdam builds on these precedents to create a spatial, immersive archive—one that integrates architectural, landscape, and curatorial strategies to preserve and interpret the city’s sensory past and present. For example, aromatic gardens can echo historical smells of industry and nature; textured materials can simulate lost tactile environments; sound installations may reconstruct vanished acoustic ecologies. By connecting these elements, the archive becomes not a static repository, but a living, experiential interface between memory and place.

As planning practices trend toward homogenization and sensory standardization— muted materials, neutral lighting, and the erasure of noise and odor—the value of a multisensory archive becomes increasingly urgent. It resists the flattening of urban character and advocates for a richer, more inclusive understanding of urban heritage. Architect Juhani Pallasmaa argues that sensory design “reinforces the existential sense of being in the world,” enabling architecture to become not just seen, but truly inhabited. The sensory archive responds to this call, offering tools to preserve urban experience beyond the visible and textual, and to reimagine the city as a site of embodied knowledge.

sensory archive

a living structure of experience and memory

The Sensory Archive is a new typology — one that neither stores books, nor exhibits objects, but instead collects, curates, and activates sensory experience. It is a public building that does not serve a single function, but sits somewhere between an archive, a museum, and a library, while intentionally challenging the limitations of each.

Unlike a traditional archive, the Sensory Archive does not preserve physical documents or institutional memory. Instead, it focuses on subjective, embodied knowledge — how people remember space through scent, rhythm, texture, sound, and movement. It is an archive not of facts, but of perception.

Unlike a museum, it does not display curated artifacts for visual admiration. Here, the content is experienced directly, through immersion, interaction, and reflection. There are no exhibitions in a conventional sense, but rather a sequence of sensory situations — spaces that invite participation, rest, attention, or contribution.

And unlike a library, it does not rely on written language as its primary mode of access. Instead, the Sensory Archive prioritizes non-visual knowledge systems. Visitors can engage through tactile landscapes, soundscapes, olfactory cues, or spatial sequencing, making it accessible to people who navigate the world without sight, and enriching the experience for all bodies.

How It Functions?

The archive is curated — not through permanent exhibits, but through seasonal themes or rotating sensory focuses, shaped by a changing curator or team. Some spaces are designed to be flexible and reinterpreted, while others provide stable functions for research, experimentation, and rest. These include:

• A Sensory Lab for workshops, recordings, and hands-on investigation

• A Study for quiet reading, reflection, or sensory documentation

• A central garden that connects the building to the seasons and natural change

• A memory wall, where visitors can leave behind their own impressions, thoughts, or tactile traces

Rather than offering passive consumption, the archive encourages participation. Visitors are not simply spectators — they are contributing bodies, leaving behind not objects, but experiences: a remembered scent, a recorded walk, a mapped emotional response. The archive grows through this input, becoming a shared and evolving record of how we experience the world.

What Can Be Found Here?

Visitors to the Sensory Archive encounter a building that unfolds through the body, not through signage or display. They may discover:

• A wall that invites the hand before the eye

• A scent that recalls an unfamiliar memory

• A soft change in floor texture that shifts their pace

• A sound that reorients their position in the room

• A space of stillness that restores calm and attention

• A shared table where they can explore a material or story with others

What is offered is not a fixed collection, but an environment that prompts awareness — of the self, of others, of place. It is a space to learn not only about sensory design, but about how differently we all perceive, and how much that difference can teach us.

What Makes It Different?

The Sensory Archive proposes a shift in architectural values:

• From visual centrality to sensory plurality

• From static form to temporal unfolding

• From institutional hierarchy to shared authorship

• From consumption to contribution

It is not about designing for the senses as content — but designing with the senses as structure. Here, accessibility is not added on after the fact. It is the starting point. The experiences of people who perceive differently — especially those with visual impairments — form the foundation of the design process, offering new ways to shape space, sequence, and material.

In this way, the Sensory Archive becomes more than a building. It becomes a civic and perceptual tool: a place where sensory memory is valued as cultural knowledge, and where architecture is reclaimed as a practice of feeling, listening, and remembering — together.

from concept to construction

This section bridges the gap between conceptual thinking and spatial practice. It translates the ideas behind inclusive and sensory architecture into design strategies, spatial systems, and material choices. Before entering the archive itself, the following chapters offer a framework to understand how the building and landscape were shaped, who they serve, and how their sensory logic was constructed.

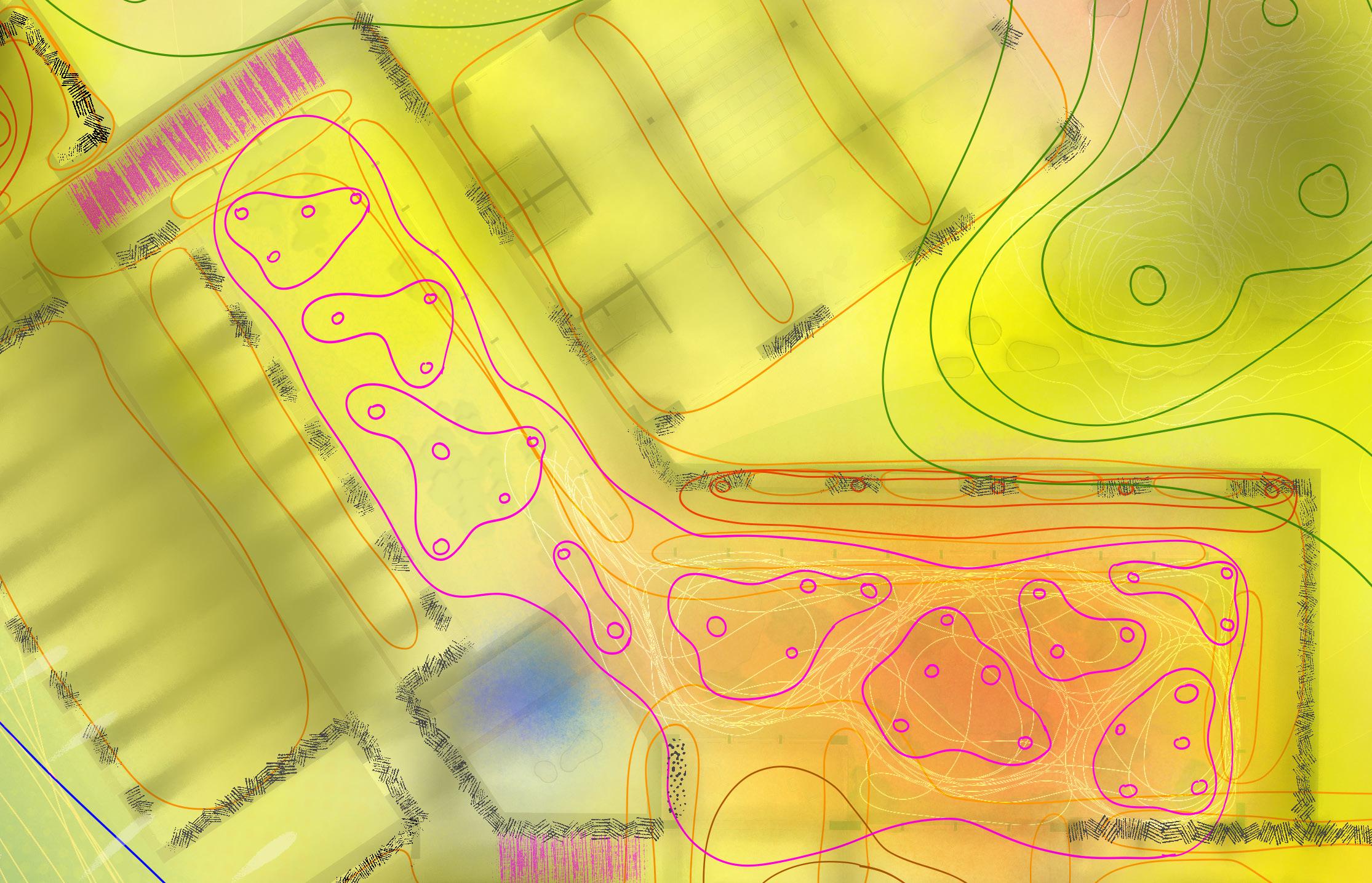

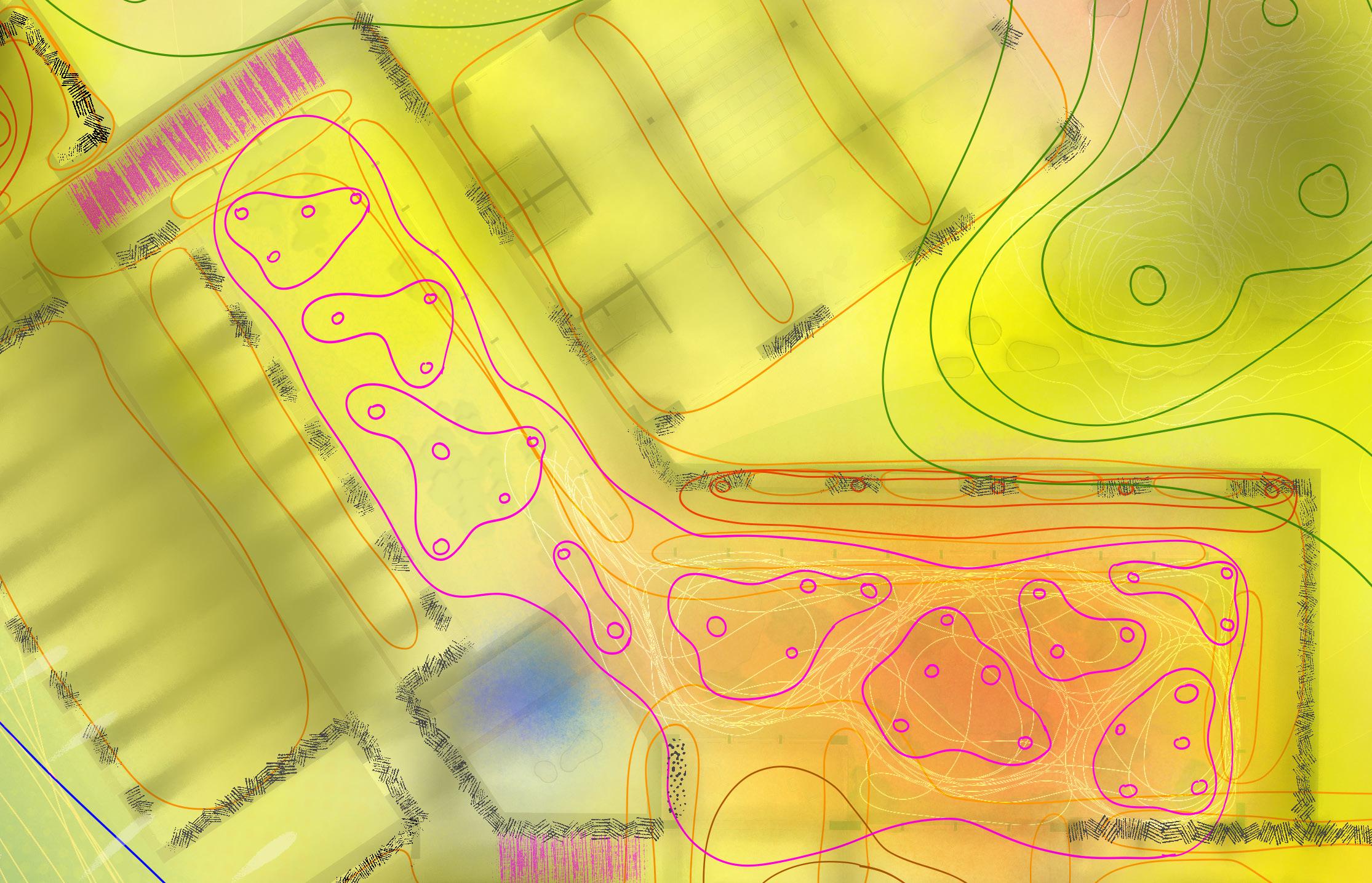

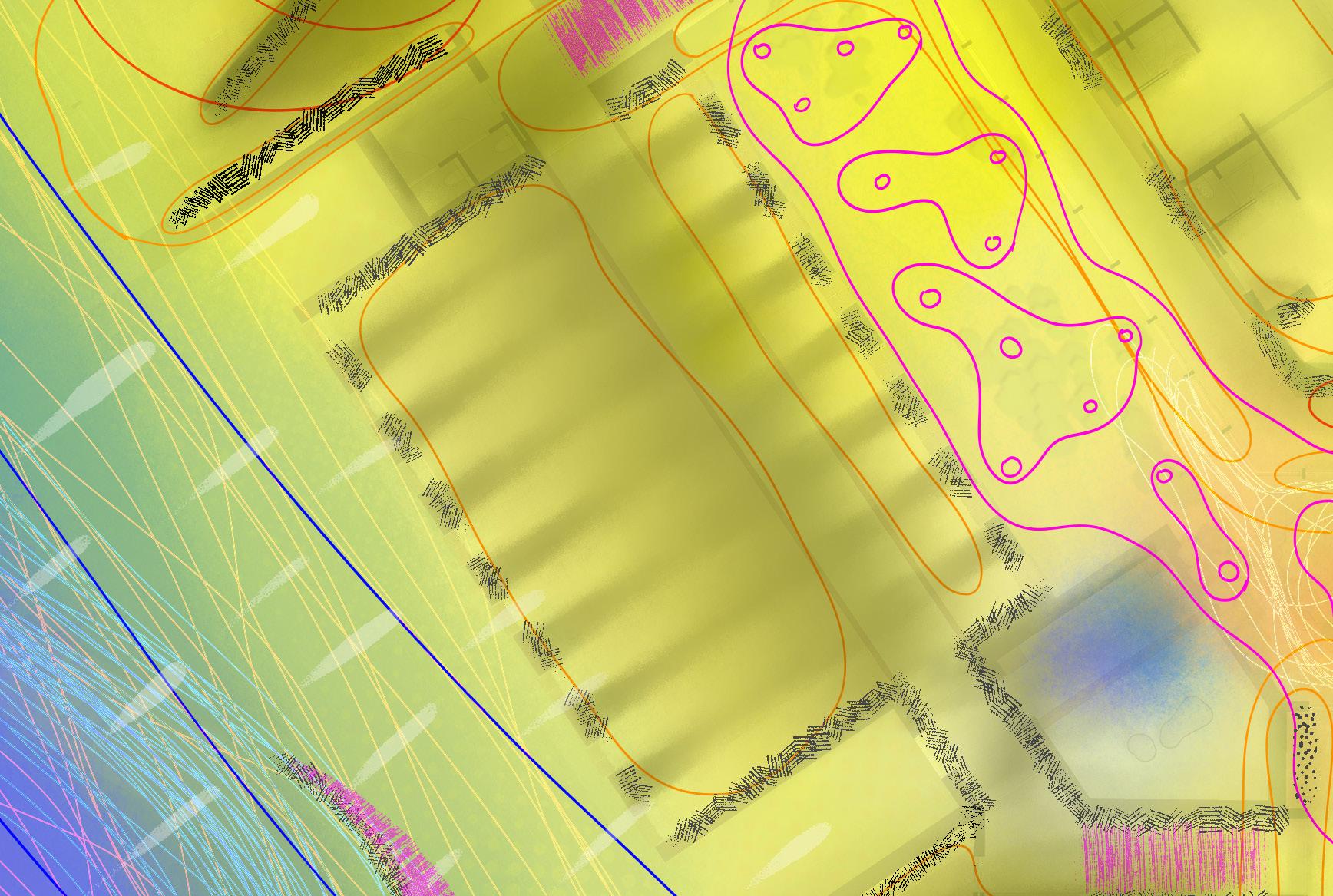

between water & memory

The chosen site lies at the edge of Buiksloterham — a former industrial peninsula in Amsterdam North, shaped by factories, freight infrastructure, and the presence of water. It is a landscape in flux, defined by layers of transition: between land and river, between industrial memory and future redevelopment, between rigid infrastructure and emergent ecologies.

Once home to the Electro Zuur- en Waterstoffenfabriek and the Nederlandsche Plantenboterfabriek, the plot still carries deep material traces of its industrial past. While most above-ground structures have been removed, the land remains marked by contamination and uneven topography. Remnants of the historical factory basements now collect rainwater, and the site’s use as a storage area for polluted soil has created a unique, dune-like terrain—organic, hilly, and highly distinct from the surrounding orthogonal developments.

The plot’s location is strategic yet quietly peripheral. It lies just outside the reach of Het Oeverpark, the city’s planned green corridor connecting the A’DAM Tower with Buiksloterdijk and Buiksloterbreek, and it sits near the cultural and creative hub of the NDSM Wharf, just across the water. These connections position the site between two types of public energy: the curated waterfront and the independent cultural fringe.

Its relative disconnection from the main route allows the design to unfold on its own terms — slower, softer, and more introspective. The decision not to extend land into the IJ respects the historic silhouette of the quay, preserving the peninsula’s form while inviting transformation at the water’s edge. A new, sloping shoreline replaces the hard industrial boundary, enabling both ecological restoration and public inhabitation without compromising the site’s raw character.

Rather than following the continuous line of Het Oeverpark, the project establishes its own rhythm — one that embraces the unfinished, the unclaimed, and the inbetween. The site becomes a space for experimentation: spatially, ecologically, and socially.

This plot is also deeply aligned with Amsterdam’s broader urban ambitions. Buiksloterham has been positioned as a testing ground for circular development, inclusive urbanism, and experimental architecture. The site’s unresolved identity — at the edge of the river, the park, and the city — offers an ideal setting for a project like the Sensory Archive, which itself proposes a new typology rooted in multisensory experience, embodied memory, and ecological participation.

Here, inclusion is not added onto a finished plan. It begins with the terrain itself.

site character & spatial qualities

The site of the Sensory Archive of Amsterdam holds a unique and layered character— marked by physical traces, industrial memory, and atmospheric nuance. It is defined as much by what is visible as by what remains concealed.

Shaped historically by industry, the plot has long been introverted and difficult to access. This sense of seclusion continues today: its terrain is ambiguous, its edges undefined, and its purpose unclear. Rather than correcting or erasing this character, the Sensory Archive embraces it—transforming the site’s latent stories into a spatial narrative of discovery.

Three distinct edges give the site a wide range of sensory conditions:

• On two sides, the plot is bordered by water. These waterways form soft boundaries, shifting in tone and intensity throughout the day and across the seasons. The water becomes a medium of reflection—visually, acoustically, and symbolically—enhancing the archive’s sensory depth.

• The interior of the site is shaped by subtle hills, slopes, and depressions— remnants of past use and gradual landscape change. These variations in ground level generate spatial moments of compression and openness, creating natural pockets for program and sensory events. The building volumes respond to these contours, embedding themselves into the terrain.

• The third edge meets the urban street, forming a porous threshold between the wider city and the quieter interior world of the archive. This boundary is transitional rather than abrupt—a space of arrival, pause, and connection.

Together, these conditions generate a landscape of contrast and continuity—urban and natural, remembered and reimagined, exposed and hidden. The architectural strategy responds not with a singular gesture, but through a distribution of building volumes across the site, connected by a winding path that mirrors the complexity of the landscape itself. The design turns ambiguity into a guide, and the site into a layered sensory journey.

remnants of the history

mysterious different experiences

design principles of the sensory archive and archive park

strategies for building through senses, scale, & site

The Sensory Archive of Amsterdam is not a singular building, but a spatial system that unfolds across terrain, material, and atmosphere. Shaped through dialogue with people with visual impairments and guided by inclusive, multisensory thinking, the project reconsiders what it means to design for perception rather than visual form alone.

This chapter outlines the core design principles that define both the archive and the surrounding park. They include the distribution of volumes, the importance of a narrative path, the zoning of spaces through sensory experience, and the use of material as memory. Together, these strategies create a framework for spatial inclusion—where architecture becomes an active participant in how people move, sense, and connect.

Each principle reflects a deliberate shift away from traditional form-making toward a process grounded in human scale, contextual memory, and the full range of sensory interaction.

archive as landscape & architecture

The Sensory Archive is not confined to a single building, but unfolds across a landscape. Architecture and park work together as one continuous system of perception. Informed by the experiences of people with visual impairments, the design moves beyond sight to embrace the full range of human senses.

fragmented volumes & narrative path

Instead of a single structure, the archive consists of multiple volumes connected by a curving path. This path organizes the experience, creating spatial rhythm, sensory contrast, and moments of pause, guiding visitors through a layered journey.

rooted in site & memory

The design responds to the industrial past and layered ground conditions of Buiksloterham. Former factory traces, shifting topography, and the presence of water inform orientation, texture, and scale—embedding memory into the spatial language.

material as sensory medium

Materials are chosen for their sensory presence: the warmth of wood, the hardness of basalt, the resonance of cork, the texture of charred timber, the contrast of copper. These surfaces shape how the archive is felt, heard, and remembered.

human scale & spatial diversity

All spaces are shaped to the scale of the body—inviting touch, slowing movement, and supporting different rhythms of use. From quiet alcoves to shared zones, the archive accommodates both solitude and interaction through varied volumes and atmospheres.

sensory zoning as design logic

Each zone is shaped by a dominant sense—touch, sound, smell, taste, or sight. This sensory logic defines materials, acoustics, lighting, and spatial proportion. The building becomes a curated sequence of sensory encounters.

visitors & sensory encounters

Archive Park and the Sensory Archive are designed not for a single audience, but for a range of visitors — each bringing different rhythms, needs, and ways of perceiving space. The project invites people to explore, stay, reflect, and return. It offers moments of connection between bodies, materials, memories, and landscapes, shaped by the archive’s layered sensory experience. Rather than designing for an average visitor, the spatial strategy is built around diverse sensory access, emotional variation, and non-linear movement. The park and building are connected not by a single path or program, but by a series of overlapping environments that adapt to their users.

• Local Residents

Living nearby, they use Archive Park as part of everyday life — walking dogs, passing through, or sitting by the water. The design remains open and welcoming, encouraging casual use without being over-prescribed. The building becomes familiar through repetition, entered slowly or in fragments over time.

• People with Visual Impairments

The project supports non-visual navigation through changes in material, acoustics, temperature, and scent. For these visitors, both park and building offer a sensory language that invites confidence, orientation, and exploration.

• School Groups and Children

The garden, Lab, and tactile spaces offer hands-on ways to learn through the body. Children are encouraged to move, listen, touch, smell, and collect — learning through play, not instruction.

• Researchers, Artists, and Archive Users

These visitors engage more deeply with the archive’s content and processes. They may come to document, reflect, experiment, or contribute. Archive Park becomes a space of observation and rest.

• Tourists and Passers-by

Arriving from the ferry or A’DAM Tower, these visitors encounter Archive Park as a moment of contrast — a slower, more intimate experience along the river. Some continue into the archive, others stay outside. Both are valid ways of engaging.

• People Seeking Rest or Isolation

The layout accommodates slower movement, avoidance of crowds, and sensory refuge. Quiet paths, shaded spaces, and minimal transitions allow for calm presence without pressure to interact.

• Non-Human Visitors

Birds, amphibians, insects, and wild plants also occupy the park. The softened shoreline acts as a shared threshold, not a barrier — allowing nature to inhabit and shape the archive alongside its human visitors.

the archive park

a natural threshold between landscape & memory

Archive Park forms the sensory landscape of the project — not an addition to the building, but an extension of its purpose. Together with the Sensory Archive, it offers a terrain shaped by movement, stillness, and perception. The park invites exploration, quiet presence, and layered experience, unfolding not through fixed routes but through spatial moments.

Unlike traditional city parks, Archive Park follows the logic of the wild and the local. The terrain is left uneven and unfixed, with native species — reeds, wildflowers, alder, and willow — growing freely. Grass is rarely cut, and sightlines shift with the seasons. The result is an immersive, living landscape — closer to a wetland than a manicured green.

The material palette mirrors that of the building. Basalt benches continue the archive’s stone language into the landscape. Corten steel edges mark transitions near water and boardwalks. The main path is stabilised light-grey sand — soft underfoot, warm in tone. Secondary routes of crushed shells and gravel lead to quieter entrances. Boardwalks along the water become Water Paths, letting visitors walk alongside — or nearly within — the IJ.

Rather than symmetry or centrality, the park is built from interconnected fragments, each with distinct moods and functions:

I The Wind Passage — a narrow corridor through a hill, framed by corten steel walls. It amplifies wind and sound, forming a sensory threshold.

II The IJ Path — tracing the water’s edge, it includes a swimming area where land and river blend for people and wildlife.

III The Reed Field and Tribune — seating among tall grasses, with shifting views and soundscapes.

IV The In-Between Hills — gentle mounds shaped by the site’s industrial past, offering shelter and microclimatic variation.

V The Entrance Square — a flat, open space where paths converge — a place to pause, meet, or move on.

VI The Water Path — a sunken boardwalk descending into a former basin, where the water rises to eye level — a quiet, reflective moment framed by stone and vegetation.

Throughout the park, boundaries between nature, infrastructure, and memory remain open. This is not an ornamental landscape, but an experiential one — a place of slow inhabitation, ecological continuity, and shared presence for both humans and wildlife.

contrast between park and garden ecology, perception,

and purpose in two landscapes

The planting in the Archive Park and the Inner Garden reflects two complementary strategies — one rooted in ecological restoration and sensory immersion, the other in cultivation, experimentation, and human interaction.

Archive Park

The park planting draws from native species and local ecologies, creating a landscape that is seasonal, untamed, and layered. Plants like reed (Phragmites australis), purple moor grass (Molinia), and dogwood (Cornus sanguinea) create structure and softness, while willows and alders support biodiversity along the water’s edge. These species help remediate soil, absorb runoff, and invite non-human visitors into the site. Grasses shift with the wind, moisture shapes scent and texture, and changes in sound and shadow guide movement. This planting strategy favors loose composition, ecological value, and slow discovery, aligning with the archive’s more atmospheric and reflective outdoor zones.

Inner Garden

In contrast, the Inner Garden is productive, tactile, and curated. It brings color, scent, and rhythm into human scale, inviting active engagement. Planting here includes lavender, sage, thyme, and borage, chosen not only for pollinators but for their aroma, texture, and use in workshops or tastings. Decorative and edible flowers such as sunflowers, nasturtiums, and calendula contribute to a vibrant, seasonal palette. Beds are loosely organized but legible—allowing visitors to gather, touch, observe, and experiment. Where the park favors natural succession, the garden emphasizes participation, harvest, and sensory education.

Together, these two landscapes form a continuum—from wild to tended, from soft to structured, from observation to action. Both contribute to the archive’s mission: to cultivate awareness of place, perception, and the more-than-human world.

the sensory archive

a building shaped by senses, memory & perception

The Sensory Archive is the spatial core of the project — not a static container, but a structure that extends the logic of the park into built form. Together with Archive Park, it creates a terrain shaped by sensation, memory, and encounter. The building invites movement and presence, unfolding not through fixed hierarchies but through atmospheres and perceptual transitions.

Unlike conventional museums or libraries, the Sensory Archive does not organize knowledge through objects or sight alone. Its architecture is guided by rhythm, material, and the senses. Surfaces are rough or smooth, spaces compressed or expanded, light absorbed or refracted. The result is not a linear sequence, but a field of sensory environments — a building experienced through the body as much as the eye.

The material language is drawn from the site and its history. Charred timber defines enclosed interiors; glass and steel open toward the terraces; basalt grounds the building into the soil. These choices echo the industrial past of the IJ while remaining tactile and elemental. The central circulation, The Path, is cast in polished concrete, its smoothness contrasting with the roughness of the Memory Wall, where visitors leave tactile traces. Rather than symmetry or monumentality, the archive is formed from distinct yet interconnected zones, each defined by a sensory condition:

1. The Threshold — a timber pavilion that frames the park and marks entry.

2. The Kitchen — a warm, glass-lined hall shaped by taste and smell, opening to terraces.

3. The Darkroom — a sunken, low-lit chamber of charred wood, focused on touch and proprioception.

4. The Reset — an open-air basalt courtyard for stillness and decompression.

5. The Studio — a high, acoustically tuned space for sound and filtered light.

6. The Study — a quiet room for reflection and listening to the river.

7. The Lab — a flexible hall for sensory research and collaborative work.

Throughout the archive, boundaries between function, sensation, and memory remain porous. This is not a building of display, but of experience — a perceptual landscape where space, material, and the senses converge.

how architecture guides experience details in transition

Materiality in the Amsterdam Sensory Archive is more than a finish — it is the archive’s narrative language. Every texture, seam, and joint is selected to make the building legible through the senses: guiding the foot before the eye, hinting at memory through the hand, softening echoes where quietness is needed, and revealing its history in layers of patina.

Positioned between the conceptual overview and the experiential narrative of “A Day in the Archive,” this chapter makes visible the decisions that shape that sensory journey. It is a translation of design intent into matter: how a threshold becomes a pause, how a surface carries time, how a line on the floor can orient an entire body.

The following sections explore each material in depth — from the anchoring stones at the water’s edge to the soft cork ceiling beneath the sawtooth roof — to reveal how the archive has been designed not as a static object, but as a living, tactile framework for memory and perception.

Vertical Basalt — Anchoring the Exterior

On the exterior, basalt is placed vertically as tall, slender slabs. This verticality recalls the corrugated metal panels that once wrapped the site’s factories, but here, in stone, it has a different weight: monumental, weather-resistant, and tactilely rich.

The vertical joints create a rhythm for both eye and hand — a slow, finger-width spacing that allows the facade to be read through touch when passing closely. In morning light, the edges cast sharp lines; in rain, water darkens the seams into a continuous surface. By night, the vertical basalt forms a dark silhouette that merges with the line of trees, turning the archive into a shadowed anchor in the park’s edge.

The surface is not polished: its micro-roughness is intentionally left intact to retain thermal expression — cool to the touch at dawn, holding warmth in the low sun of evening. In this way, the exterior basalt becomes both a boundary and a register: of time, of weather, of contact.

Horizontal Basalt — Grounding and Slowing Time

In the Reset space, the same material is reoriented: horizontal slabs run in deep courses along the walls and low plinths. Here, the effect is not one of vertical anchoring, but of slowing.

Grooves and subtle recesses in the horizontal basalt collect rainwater, guiding it in a controlled trickle that creates a steady, meditative soundscape. This acoustic cue marks the Reset as a place to pause: the rush of the park outside becomes a distant murmur; here, water takes its time.

The stone’s horizontal grain reinforces this atmosphere of stillness. Where the exterior basalt is about scale and boundary, the horizontal basalt is about duration and contact — a stone you lean on, sit against, feel beneath your hand while your attention recalibrates.

CLT — The Rhythmic Frame and Familiar Backbone

The entire structural system of the archive is made from cross-laminated timber (CLT). This decision was both environmental and experiential: it reduces embodied carbon and creates a warm, familiar rhythm that threads through the building.

The CLT panels are deliberately left exposed in corridors, thresholds, and high circulation spaces. Their modular joints register as a silent measure of movement — a kind of architectural pulse that repeats from entry to archive hall to garden edge. Visitors often experience it subconsciously: the gentle grain, the soft reflection of daylight, the sound of footsteps slightly softened compared to concrete or stone.

As a structure, CLT carries the archive. As a material, it sets the baseline tone: warm, structured, and legible — a timber skeleton that makes other materials feel like episodes within a larger, continuous narrative.

Wood – Thresholds, Modulation, and Seasonal Dialogue

Wood serves as the mediator between the archive’s heavier and harder materials. Its primary role is in framing transitions and modulating light. Deep 500 mm portals mark significant thresholds, their timber frames fitted with double doors whose copper handles shine at the point of grasp. Passing through these is a choreographed pause: the depth signals change, the material warmth balances the cooler CLT beyond.

In the Study, wood becomes more continuous — dark flooring and shelving that absorb noise and soften footsteps. Here, turning wooden lamellen (louvres) and window frames enable dynamic control: they can filter the industrial light from the river side or open wide to flood the room with brightness, shifting the space from introspective to outward-looking in a single gesture.

Along the garden path, shingles on the wooden roof create a responsive soundscape. Rainfall here is not muffled; it becomes an audible curtain that traces the weather’s passing.

Wood is a recorder: it dents, darkens, polishes over time. It offers a memory of touch more personal than stone or steel — the trace of a hand at a threshold, the patina of repeated turning of a louvre.

Copper – A Guiding Line with Light and Memory

Copper is the archive’s most active guiding element: a thin, continuous line inlaid in the concrete floor, copper-edged shelves, handles, and the welcoming counter at the entrance.

Unlike typical wayfinding strips, the copper line is recessed slightly below the floor level — not a trip hazard, but a tactile depression your foot can sense if you step directly on it. In some segments, the copper is lightly textured to catch glancing light, creating a subtle shimmer that shifts as one moves. In others, it is smooth and burnished, gradually polished by countless soles and wheels.

Copper also meets the hand: door handles with a warm, living patina; shelf edges that gleam at the finger’s sweep; a reception balie whose panels glow with diffuse reflection as light from the entrance filters over it.

Its role is continuity — a metallic thread that ties together diverse spaces: from the darker Study to the open Lab, from the Reset to the garden edge. Copper is deliberately placed where the body touches or moves — so that over years, it darkens, records, and reflects the collective memory of use.

Weathered Steel (Corten) — Industrial Edge and Time

Corten steel was chosen for its dialogue with time and industry. It is used where edges need both structural definition and narrative resonance: the Wind Passage walls, boardwalk edgings, and certain window surrounds.

Its surface begins bright orange, then deepens through exposure: a slow choreography of color that mirrors the site’s own evolution from working dock to cultural park. Tactilely, its matte roughness contrasts with copper’s sheen and basalt’s density, making edges legible to both eye and hand.

Placed between water and land, Corten is the material most exposed to change — and thus the one most aligned with the archive’s central theme: memory as a living, weathered layer.

Charred Wood – A Cloak for Shadow and Perception

The Darkroom is the most introspective space within the archive — a place where vision is intentionally subdued to allow other senses to come forward. To create this shift, the walls are lined with charred wood, treated using the traditional Japanese technique of shou sugi ban.

This burning process seals the surface, making it resistant to moisture and wear while leaving behind a deep, matte black texture. The char is not uniform: it carries faint striations, a subtle ridged grain that invites the fingertips to explore its unevenness. Under low light, these grooves break reflections, creating a surface that absorbs rather than bounces.

The scent of the material — faintly smoky, earthy — lingers as a reminder of its transformation: wood preserved by fire. This adds a quiet olfactory layer, almost imperceptible but present when one slows down. In this way, the Darkroom’s cladding is not just functional; it is a sensory veil, creating a cocooned interior that allows the visitor to recalibrate their perception — to listen more closely, to feel their own proximity, to be present in a space where light has retreated and texture speaks.

The Sensory Lab is both a workshop and a threshold to the landscape. Its design needed a material strategy that could accommodate experimentation, seasonal flux, and variable acoustic needs.

The flooring is composed of robust tiles — the same as those in the kitchen — creating a visual and physical continuity between inside and the large exterior terrace. Where hardness could become overwhelming, cork steps in as a soft vertical and overhead mediator. Panels line the walls and ceiling, forming a textured, porous surface that absorbs reverberation and modulates the generous daylight that enters through the three-part sawtooth roof. The cork’s muted tone reduces glare, its springy resilience dampens echo, and its natural pattern brings a subtle visual rhythm to the high volume.

For specific activities — tactile workshops, seated group sessions, barefoot sensory explorations — temporary cork mats can be introduced, rolling out a layer of compressible warmth over the tiled floor. This dual strategy — hard, durable base with soft, adaptable overlays — reflects the Lab’s ethos: not one fixed sensory condition, but a responsive field where materials collaborate to support changing modes of making, learning, and sensing.

Cork – Adaptive Softness Beneath the Sawtooth Roof

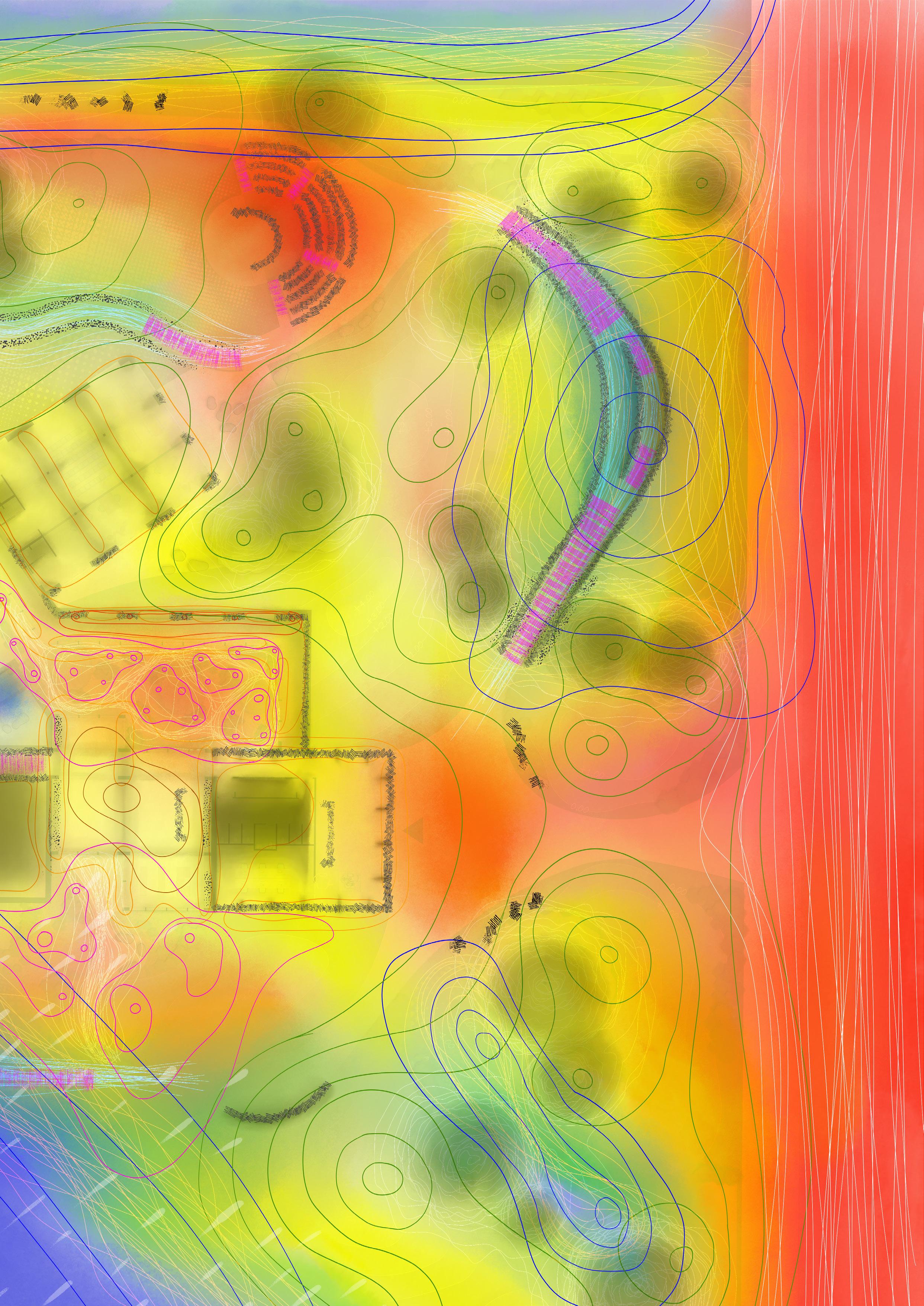

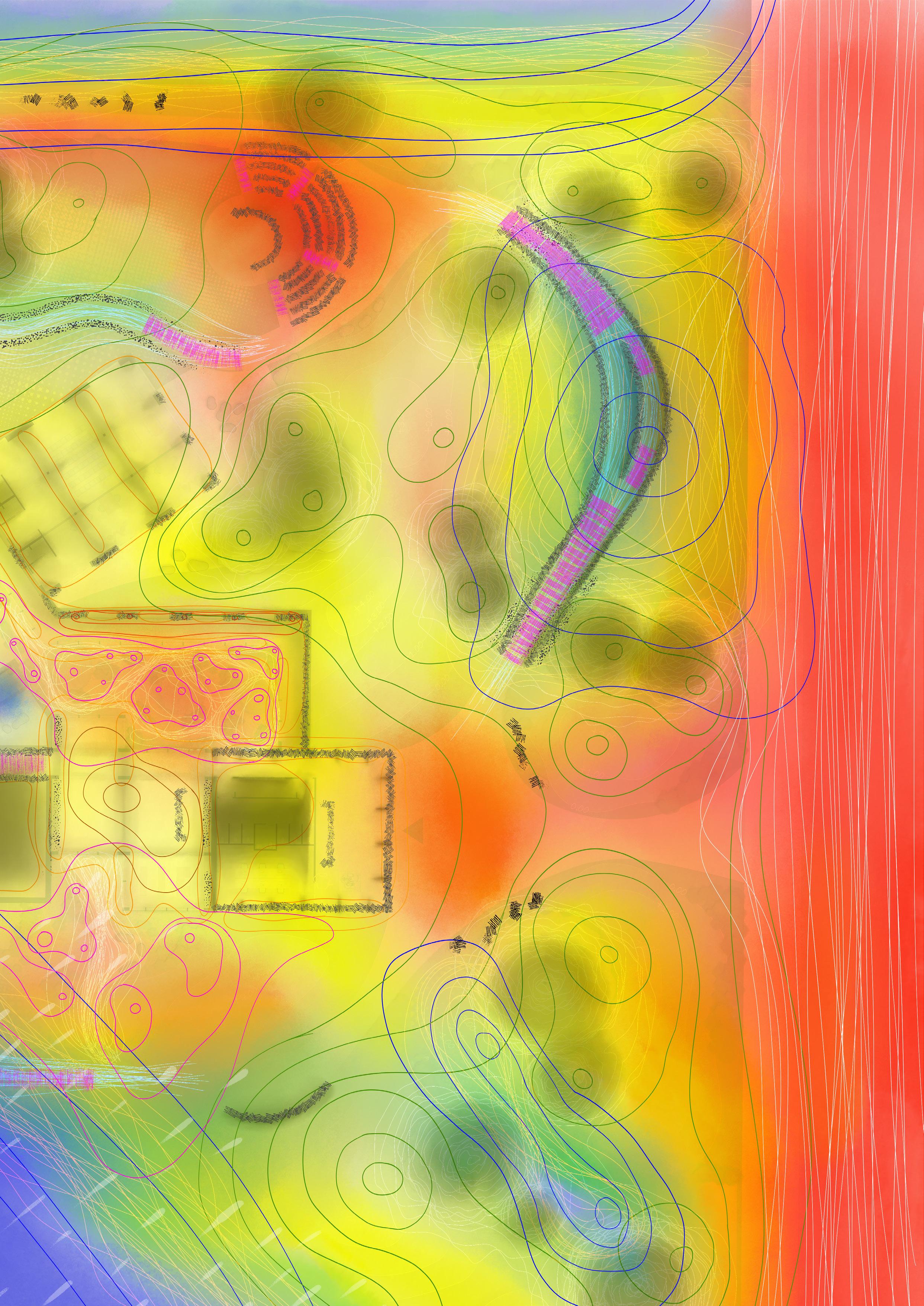

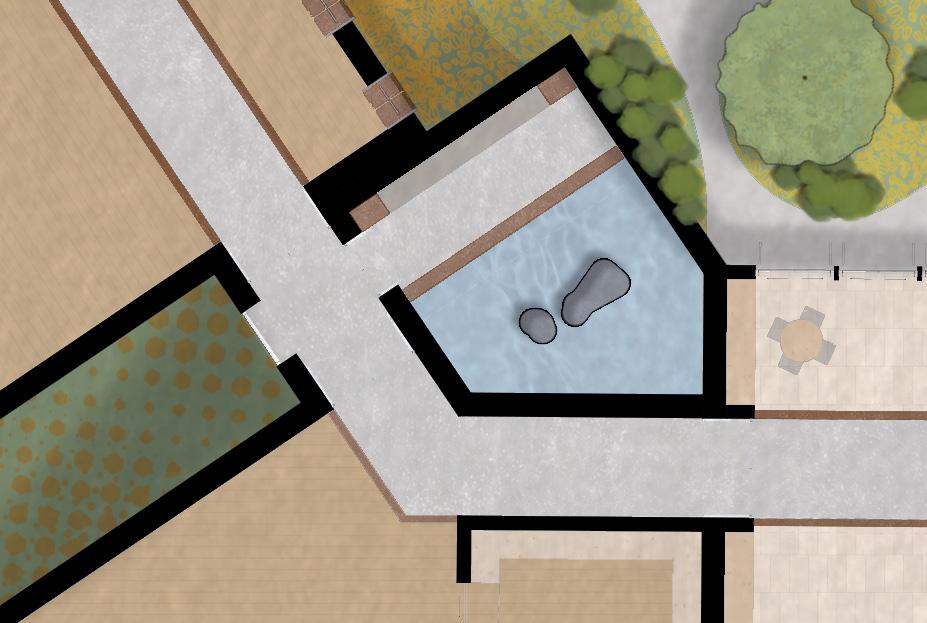

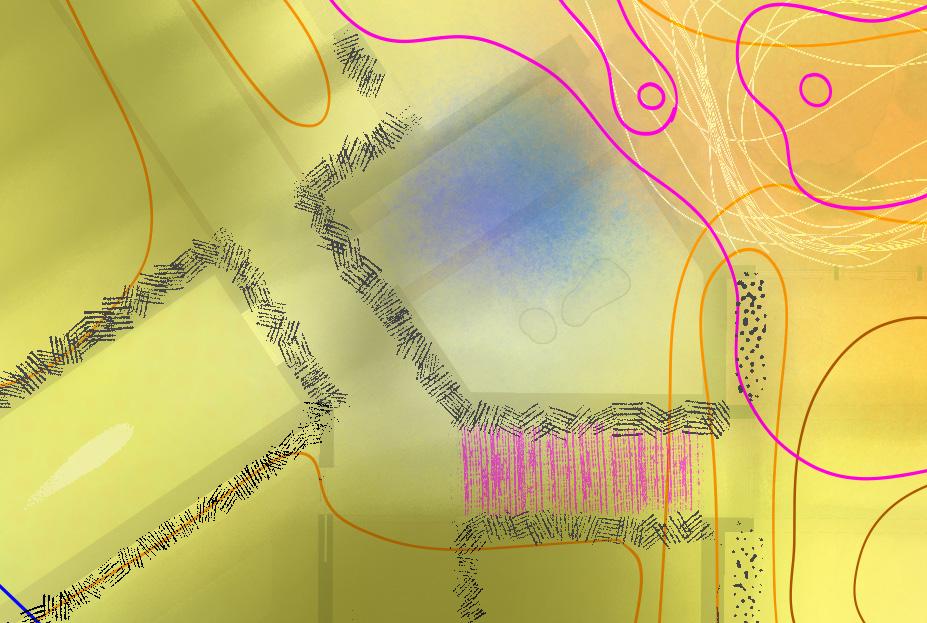

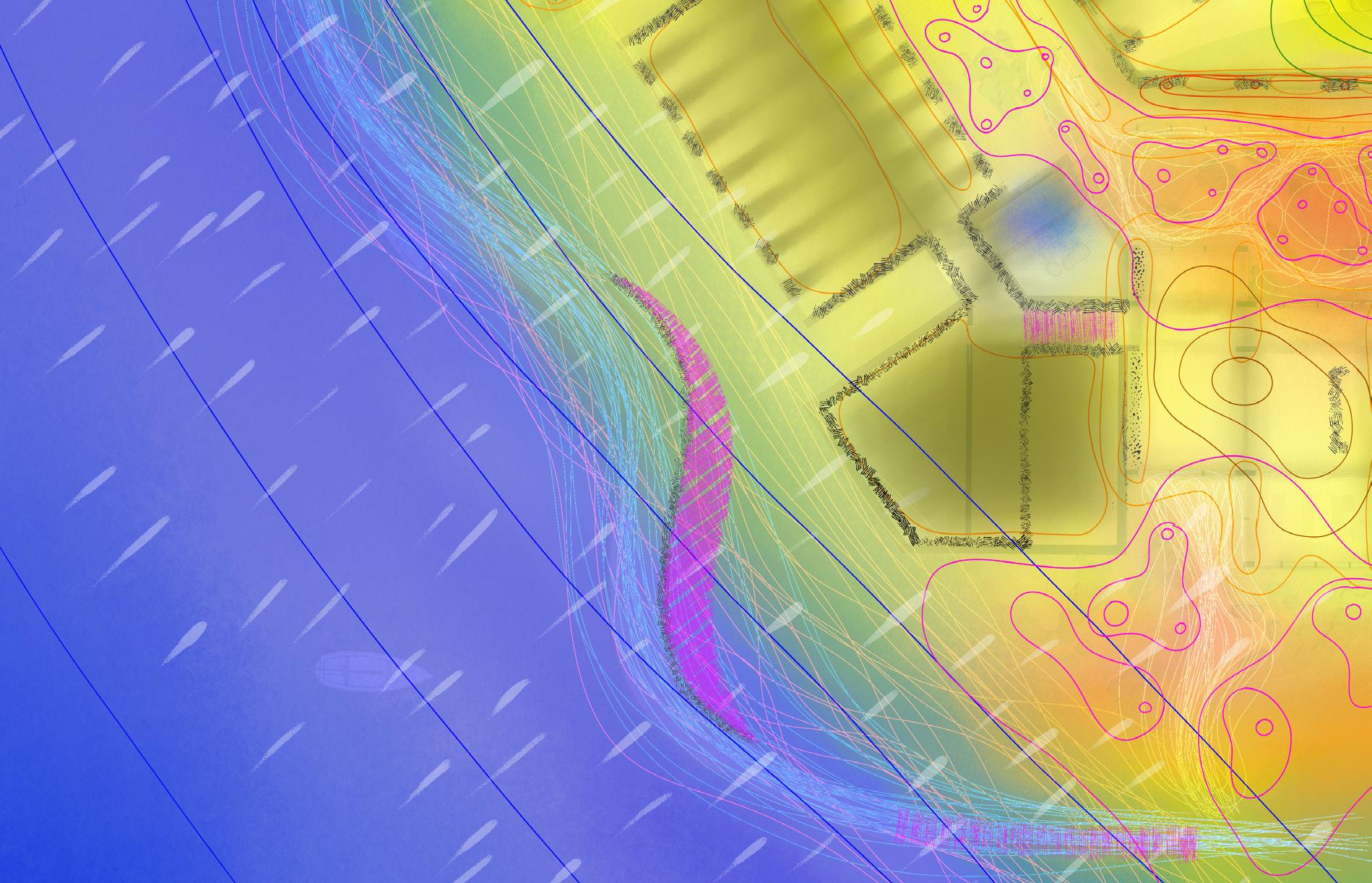

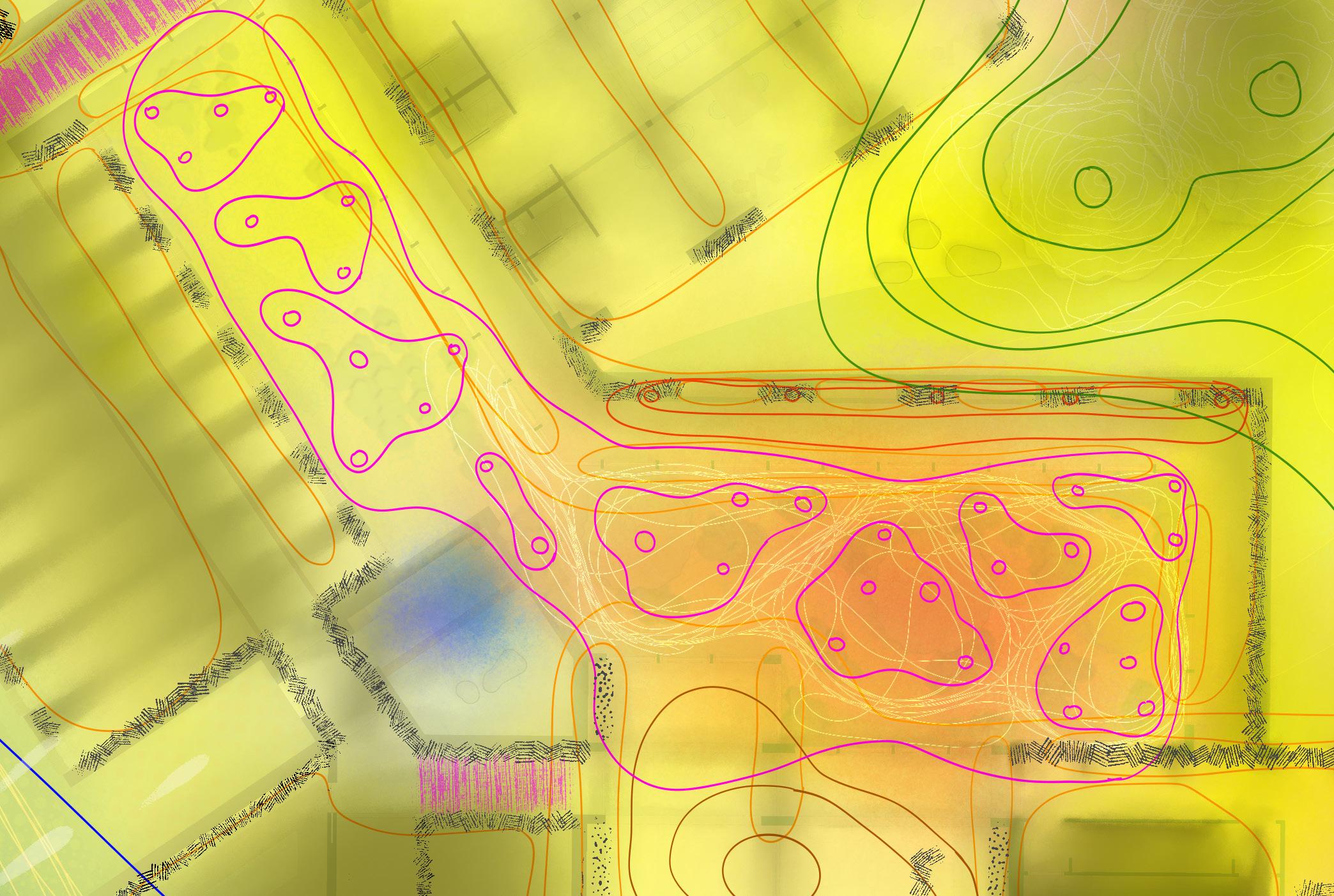

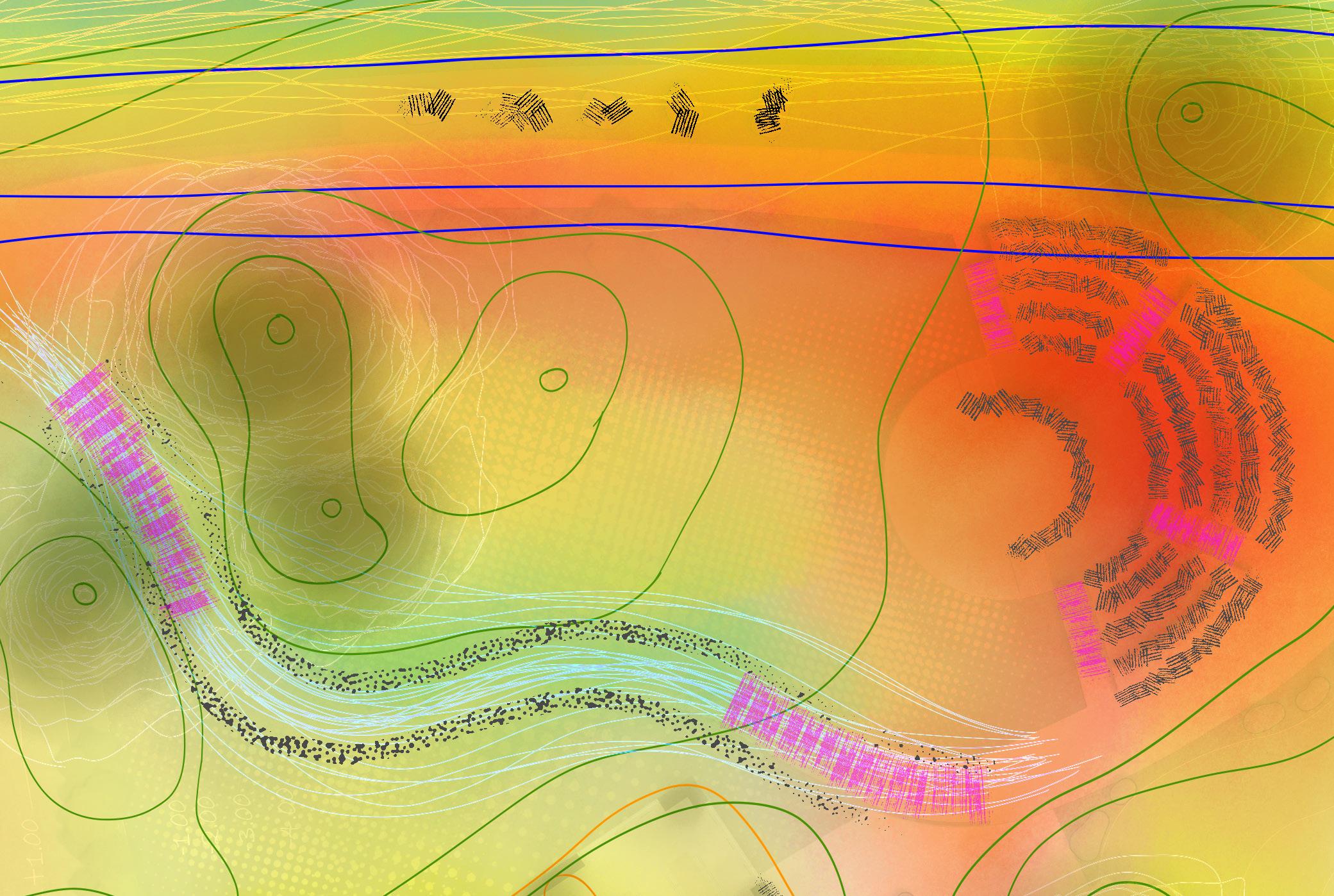

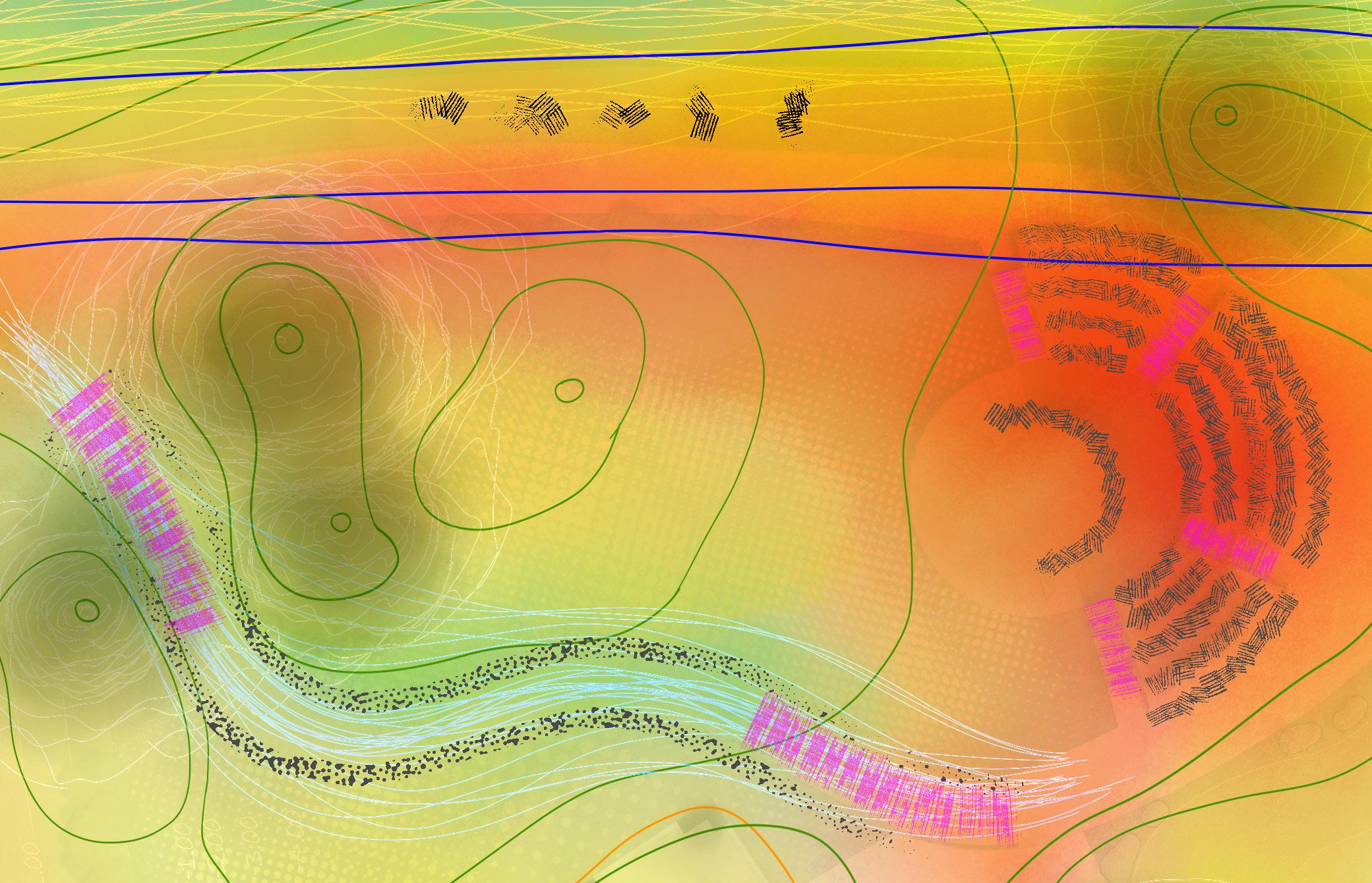

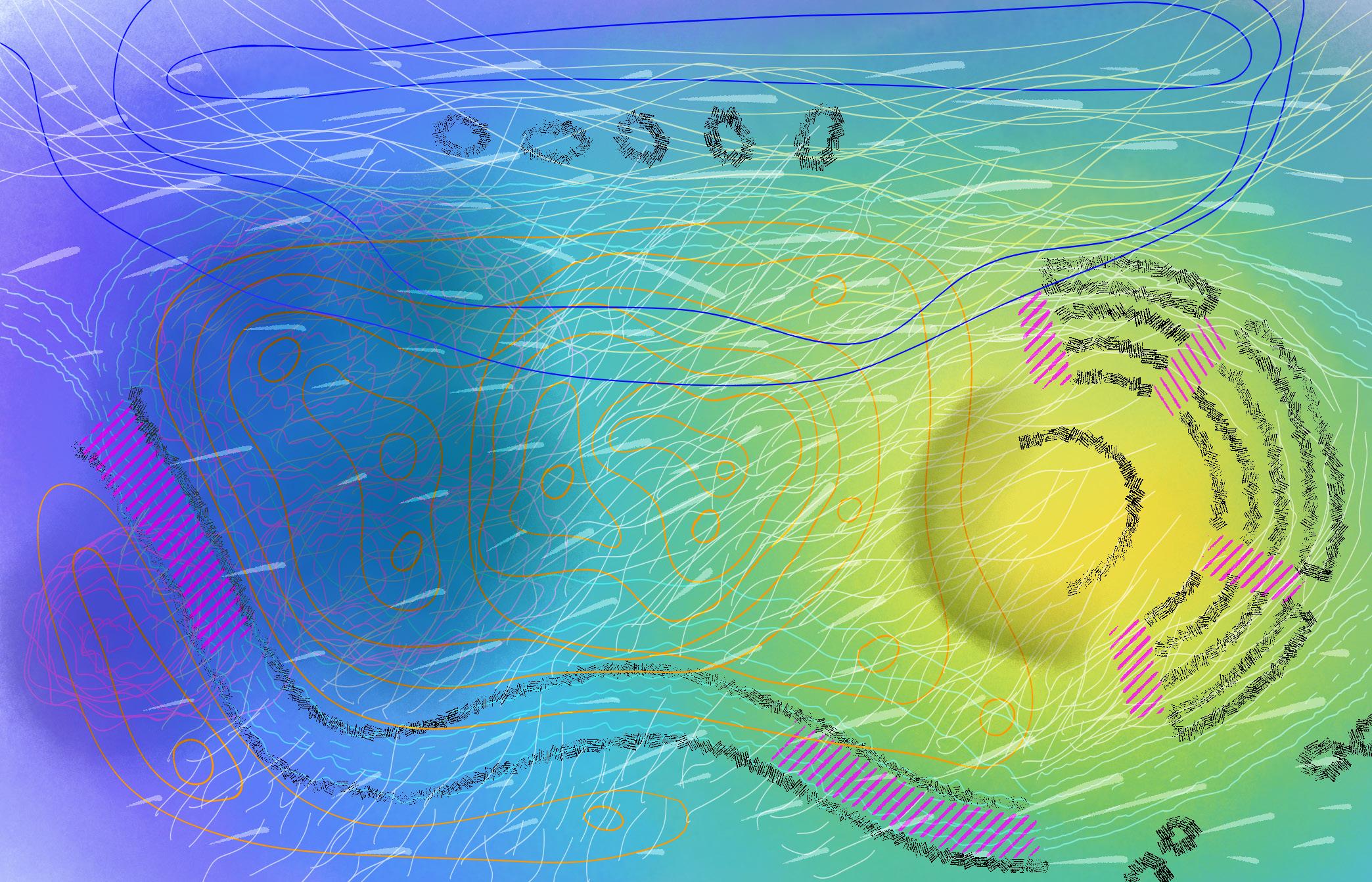

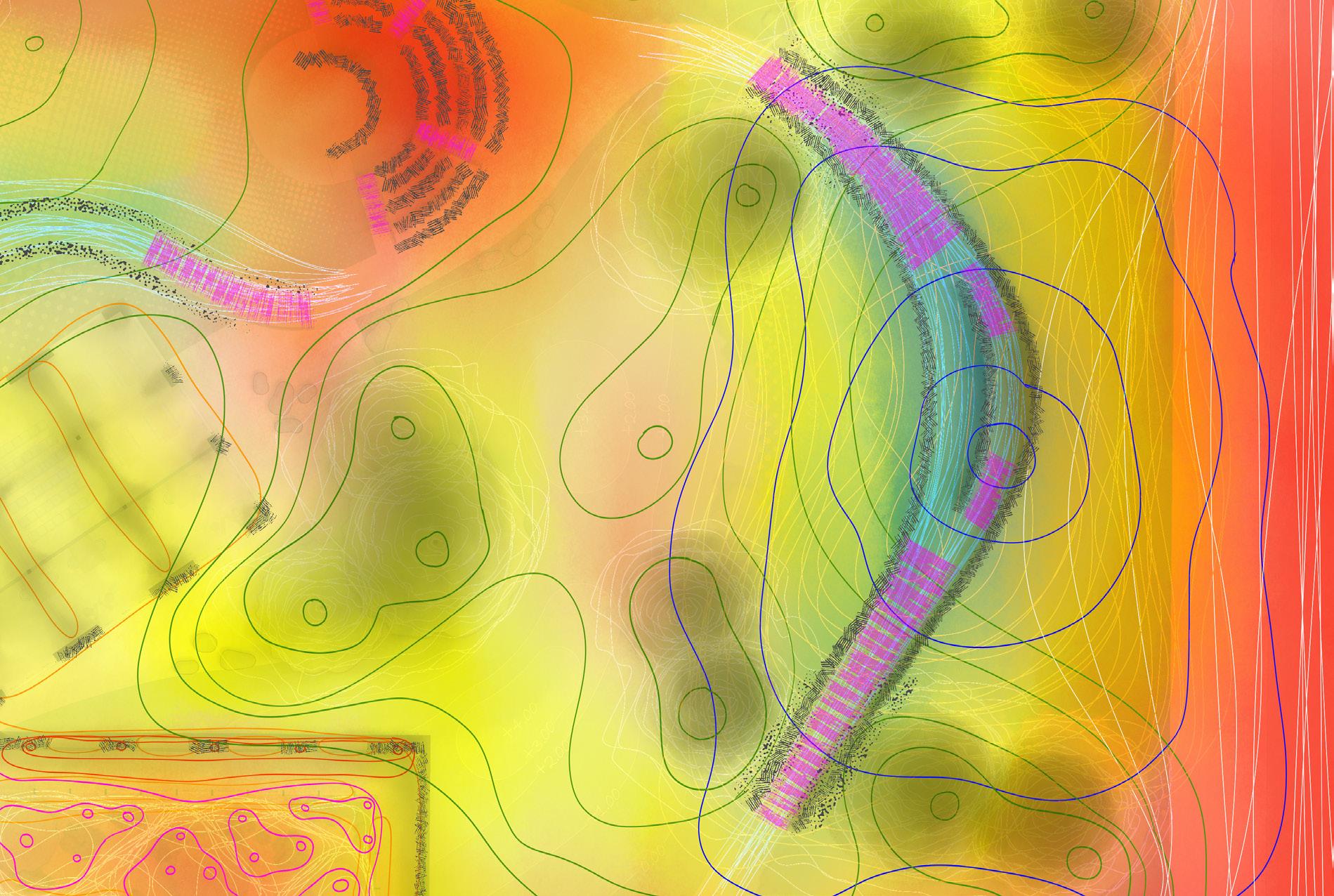

sensory map

visualizing the layered experience of space

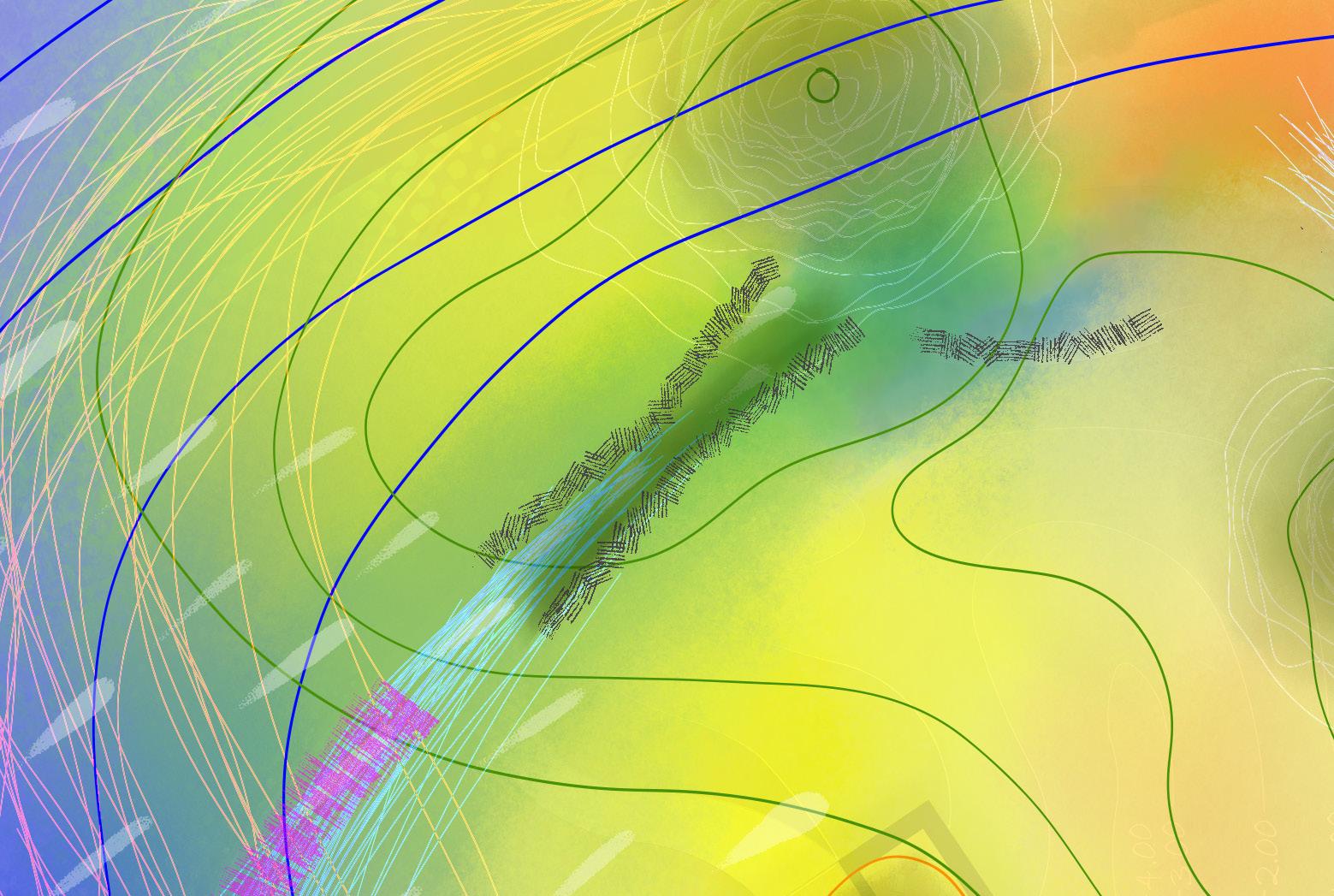

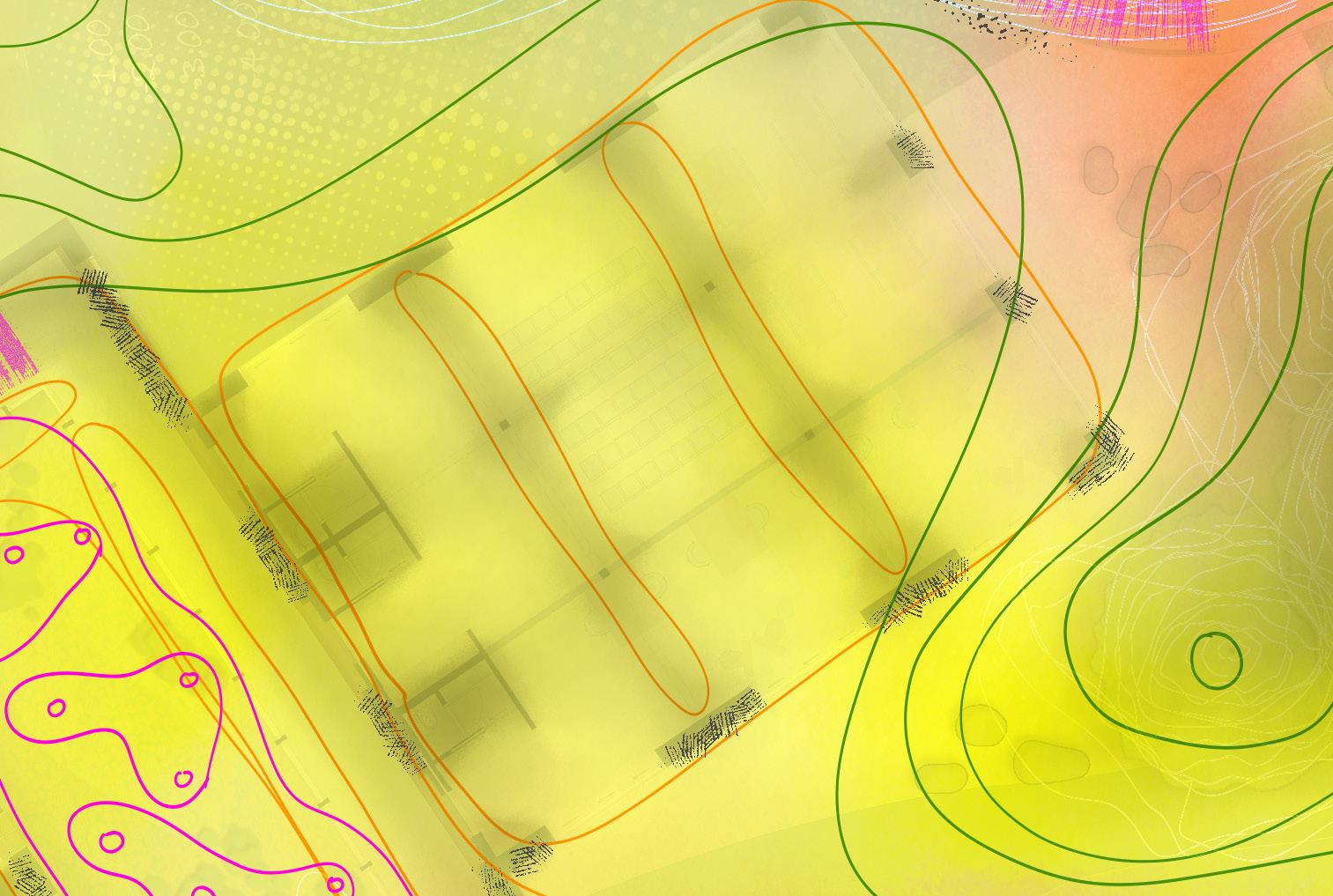

The sensory map was created to reveal how the Sensory Archive and Archive Park are experienced not just through form or function, but through the conditions that shape perception. While a traditional floor plan shows spatial layout—walls, doors, openings— this map adds another layer: how each space feels to move through.

It records average sensory conditions such as: – Temperature – Wind exposure – Sounds – Movement of the body (ascending & descending) – Smells – Shadows – Tactile qualities

By layering these elements, the sensory map begins to visualize the atmosphere of each space—whether natural or designed. It shows how sensory characteristics are distributed, how they transition, and where they concentrate. This includes both outdoor and indoor environments, connecting the archive to its landscape as a continuous sensory field.

The map is not technical, and it is not fixed. It does not attempt to define a space permanently, but to express its character at one point in time—a moment shaped by climate, material, orientation, and program. Like the archive itself, the sensory map is open-ended. It will change as the site evolves, as curations shift, or as different users bring their own presence to the spaces.

To the right, a visual breakdown shows how the map is constructed: each sensory layer is represented step-by-step—temperature, sound, wind, body movement, and so on—so that the reader can see how sensory experience is built up through multiple dimensions. This layering reveals a deeper logic behind the spatial design: not only where something is, but how it is sensed.

The map’s purpose is threefold:

• To show how sensory perception becomes part of architectural thinking

• To reflect the diversity of conditions that make each space unique

• And to invite readers, designers, and visitors to think beyond functionality, toward experience

In this way, the sensory map becomes part of the archive: a record of how a building can feel, not just how it is built.

temperature

sounds

position of the body (ascending & descending)

shadows

smells

tactile wind

reading the archive

reading space through states, senses, and actions

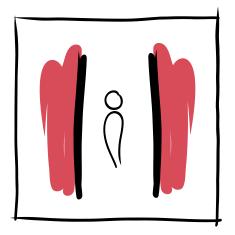

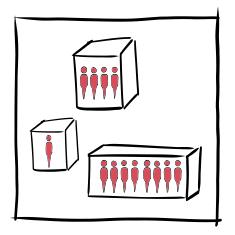

Each space in the Sensory Archive is shaped not only by its function, but by how it is meant to be felt, used, and moved through. To understand the emotional and perceptual landscape of the archive, this framework presents a set of diagrams and icons that describe the core characteristics of each zone—before they are explored in detail.

The aim is not to define the spaces rigidly, but to highlight the sensory logic and spatial intention behind their design. Each zone is represented through a consistent set of categories:

• State of Being — whether the space supports solitude, shared presence, or both

• Sensory Focus — the dominant sense(s) that shape the experience

• Types of Activity — such as reflection, exploration, creation, rest, or interaction

• Spatial Qualities — including enclosure, connection to the outdoors, light, sound, or movement

These diagrams offer a readable overview of how architecture guides experience—how materials, light, sound, and orientation are used to invite attention, shape memory, and support different forms of presence. The framework also supports curatorial flexibility, showing how each space can hold different meanings and functions over time.

Together, they form a navigational language for the archive—visual tools to understand how design can respond to bodies, senses, and diverse ways of being.

state of being alone

together

sensory focus

olfactory gustatory auditory tactile visual

proprioception motion temperature

activity

exploring creating resting information researching

spatial quality

full view light in between disconnected limited view half dark inside visually connected no view dark sloped physically connected hills water field / garden

a day in the archive

This final section offers an immersive journey through the Sensory Archive and Archive Park. Each element—indoor or outdoor— is introduced through the perspective of a visitor, narrated as a continuous day unfolding through sound, scent, light, texture, and movement. Following each narrative impression is a spread with drawings, materials, and design strategies, showing how experience and architecture intertwine. Together, these sequences bring the archive to life—not as a static building, but as a living, sensing structure of encounter and memory

once, I decided to visit the Amsterdam

I arrived on an overcast morning — the kind of light where the air feels like memory.

The ferry had just left behind its wake, and the wind curled gently across the water. I followed the curve of the quay, past reeds bending and the smell of wet stone, until the outline of the building came into view.

It didn’t call attention to itself. It didn’t need to.

It sat low in the landscape, part shelter, part silence — as if it had always been there.

The first thing I noticed wasn’t the architecture. It was the way the place slowed me down. Without realizing it, my exploration is already began.

the entry square

I stepped in from the street — no gate, no wall, just a clear space between two hills

The building was straight ahead. To the left, the path curved into the park. To the right, toward the water.

I paused for a second on the edge, then kept going.

entry square

a terrain-framed threshold between street & archive

The Entry Square is the first open moment after arriving from the city. It sits just beyond the street — a level, cleared space between two soft hills, where the park begins and the building comes into view. The square is neither closed nor crowded. It is defined not by built form, but by terrain, surface, and direction.

Visitors enter from the urban edge of Buiksloterham, where the traffic and ferry flows are still present. As soon as they step onto the stabilised sand of the square, the pace begins to shift. There are no trees, but the hills on either side create a subtle threshold — a sense of entering without enclosure.

Straight ahead, the glazed entrance of the archive sits quietly in view. To the left, a path curves toward the In-Between Hills and the river. To the right, a route leads toward the Water Path and one of the old basins. The square does not dictate direction, but invites decision. Its openness supports gathering, crossing, or waiting — whatever the visitor needs.

Along the edges, basalt benches appear like low, irregular rocks — informal, stable, and tactile. Their form mirrors the material language of the building and provides visual anchors within the minimal space.

The Entry Square is not monumental. Its strength comes from clarity and calm — the feeling of having arrived somewhere specific, but not yet stepped inside.

framework of experiences:

section

sensory section

the threshold

The door never really closed. I walked straight in — glass all around me, a floating roof above, the floor unchanged. It felt quiet, but not silent.

I could still hear the park behind me. The light was soft.

I stood still for a moment, then moved on.

the threshold

a pavilion of transition and openness

The Threshold marks the entry into the Sensory Archive. Rather than a closed door, it is designed as a lightweight pavilion — a transparent, welcoming space that signals arrival without interruption. Framed in timber with a high, floating roof, it sits between Archive Park and the archive interior, offering an extended moment of pause, orientation, and openness.

The space is defined by glass façades on three sides, allowing uninterrupted views across the park and a strong visual connection to the garden and landscape beyond. The roof appears almost detached — slightly lifted, creating a sense of breath and vertical lightness.

The floor is poured concrete, continuous with the main path outside, so that crossing into the building doesn’t feel like a hard threshold but a gentle continuation. Its surface is smooth but not polished, creating soft sound feedback for orientation and subtle temperature shifts underfoot. Along the perimeter, a low basalt frame at bench height outlines the space and provides places to sit or lean.

A reception element, made of copper, sits off to the side — not dominant, but clearly present. Natural light enters from all sides and above, and the acoustic character is open and balanced, allowing conversation and ambient sound from the park to mix.

The Threshold is not a destination in itself but a calm transition space — a moment of arrival that lets the pace of the city drop away before entering the more curated, internal world of the archive.

framework of experiences:

section

sensory section

the path

I followed the path — smooth concrete underfoot, a copper line beside me.

On the wall, someone had left a folded note. Next to it, a string, a shell, a worn piece of paper. It didn’t tell me where to go, but it reminded me I wasn’t the first one here.

the path

a sensory spine that connects without directing

The Path is the main circulation route of the Sensory Archive — a continuous, gently shifting floor that links all spaces without hierarchy. It is not a corridor but a spatial spine, designed to support multisensory orientation and calm navigation throughout the building.

Its surface is a smooth concrete floor, chosen for its subtle sound response — enough to register nearby footsteps without echoing. Along one edge runs a narrow inlaid copper strip, functioning as a quiet guide. This guiding line creates contrast in texture, temperature, and tone, helping visitors follow the path through touch, cane, or sight.

The Path does not force movement. It adapts to each zone — widening in some places, narrowing in others, always responding to light, view, or material. It opens toward gardens, intersects with spaces, and disappears into quiet corners.

Running alongside much of the route is the Memory Wall — a long, tactile surface designed for contribution and exchange. It invites visitors to leave behind small sensory objects, notes, or fragments. Some are temporary, others permanent. Over time, the wall becomes a living record of presence — not digital or catalogued, but felt, touched, and remembered.

The Path and the Memory Wall together create a quiet infrastructure for discovery — not directing movement, but supporting it. They form the backbone of the archive: calm, clear, and alive with small traces.

framework of experiences:

sensory map with average conditions

sensory map on an early quiet rainy autumn morning

the kitchen

The smell reached me before the doorway — something fresh, sharp, maybe citrus or soil.

Inside, someone was talking quietly. A few others gathered around the table.

The doors were open to the garden. I could hear a bird, the scrape of a chair.

It felt warm, alive, like something was always just starting.

the kitchen

a warm space of scent, taste, and seasonal change

The Kitchen is the most sensorially expressive space in the archive — a place where scent and taste form the primary architectural experience. It is designed not as a functional kitchen, but as a greenhouse-like space for edible plants, aromatic herbs, small workshops, and curated sensory events.

The space is enclosed in a glass and timber structure, open to light and to the surrounding garden. Its form recalls the greenhouses found across Amsterdam, but here adapted to slow occupation and multisensory presence. The air is warmer, slightly humid, and always carrying a smell — of mint, lemon balm, rosemary, or soil. Depending on the season, this atmosphere shifts in tone, strength, and color.

The floor is made of basalt tiles, which continue directly from the adjacent outdoor terraces, creating a seamless material connection with the garden. Windows and doors open wide to the outside, and activities often spill over into the garden itself. The transition between indoor and outdoor is deliberately loose, inviting the body to drift between planted ground and interior room.

Furniture is minimal — a long table, open shelves, and a work counter — but the space remains flexible: used for preparation, gathering, or pause. The acoustic character is soft, with sounds absorbed by greenery and wood, and light filtered through layered leaves.

This is not a space for spectacle, but for quiet sensory encounter. The Kitchen is meant to be touched, smelled, tasted, and remembered — not only through vision, but through the body and the air.

framework of experiences:

section

sensory section

the darkroom

I stepped down — just a meter, but enough to feel it.

The light faded slowly. The walls turned dark and textured.

I reached out, not because I had to, but because I wanted to. Everything here asked to be felt, not looked at.

And so I moved more carefully — but not less confidently.

the darkroom

an inward space for touch and orientation

The Darkroom is the most introverted zone in the archive — a space that intentionally reduces visual stimulation to shift focus toward touch, balance, body awareness, and atmosphere. It is designed as a slow, sensory passage that encourages the visitor to navigate through movement rather than vision.

To enter, one walks down a gentle slope, descending just over a meter. This shift in level subtly removes outside references, enhancing a sense of enclosure. The space is tall and narrow, with walls set at slight angles and horizontal windows positioned close to the ceiling. These openings allow in soft, indirect light but block views of the outside world.

The walls are lined with charred timber, creating a deep black surface with rich texture and subtle smell. The floor remains concrete, carrying a muted echo of footsteps. Corners are rounded, and edges softened, allowing the body to move with less fear of collision — offering comfort through tactile clarity.

The atmosphere is quiet. Acoustic absorption is increased through wall material and layout. Voices drop. Attention turns to surfaces, to weight, to where the foot lands. The space isn’t dark in the literal sense, but in character — a room to slow down and notice things usually missed.

The Darkroom is not an exhibit. It is a tool for recalibration — to shift from external orientation to internal sensing, from knowing where you are by seeing, to knowing it by being in it.

framework of experiences:

section

sensory section

the reset

The stone bench was just under a roof, dry and cool. In front of me, the other three walls opened to the sky.

Water slid quietly down the basalt into a shallow pool.

I didn’t need to name it or explain it. I just sat. And it was enough.

the reset

a still space for reflection and release

The Reset is a small, fully enclosed exterior room, designed to offer a quiet pause between the more immersive spaces of the archive. It is a place to decompress, sit in silence, and recalibrate the senses before moving on.

The room is surrounded by four walls. One side is partially roofed and contains a fixed basalt bench, polished and smooth to the touch, with corten steel edges marking its boundaries. The remaining three walls are open to the sky, constructed from horizontal basalt slabs stacked with narrow joints. When it rains, water slowly trickles down their surfaces into a shallow rectangular pool that reflects light and sound.

The space invites stillness. It is not programmed — there is nothing to do here but sit, breathe, and observe. The sound of moving water, footsteps outside, or distant wind becomes clearer in contrast to the space’s calm interior.

The floor is made of crushed shells and gravel, the same material used in the park’s secondary paths. Its muted tone and soft texture create a light acoustic dampening, slowing movement as one enters and exits. There is no glass, no technology, and no direct view out — only stone, water, metal, and sky.

The Reset offers no specific message, only space. It is a moment of openness framed by solidity, where the visitor is encouraged not to think, but simply to be.

framework of experiences:

sensory map with average conditions

sensory map on an early quiet rainy autumn morning

the studio

The air changed as I stepped in — taller, more focused.

Light filtered in from both sides, and I could hear soft movement across the room.

Someone adjusted a speaker. Another sat writing, headphones on.

It wasn’t silent — it was tuned. I didn’t speak, but I stayed — listening.

the studio

a vertical space tuned for sound and light

The Studio is a tall, calm space designed around sound and filtered light. Unlike other rooms in the archive that withdraw or blur boundaries, the Studio is more defined in shape and direction, offering a space that is structured, atmospheric, and receptive to subtle acoustic and visual shifts.

The room has a high ceiling and vertical proportions that emphasize echo, reflection, and tone. Tall, narrow windows line both long sides of the space — one facing the inner garden, the other the river IJ. These windows are fitted with turning louvres, allowing light and sound to be carefully modulated depending on time, activity, and orientation. The views are partial and controlled, letting light in while softening visual distraction.

The material palette is restrained and warm: a concrete floor, smooth and acoustically tuned; walls and window frames in timber, and subtle metal fixtures. The air is still, the lighting indirect, and the room’s form slightly resonant — not loud, but responsive.

The Studio is used for quiet workshops, sound experiments, listening sessions, or simply silent presence. Its spatial design makes it appropriate for group or solo use, offering a sense of focus without pressure. The windows allow connection without exposure, and the space holds sound gently, not flatly — making one aware of presence, breath, and movement.

framework of experiences:

section

sensory section

the study

I entered quietly.

One wall held shelves all the way to the ceiling. The other opened to the water.

The smell of books mixed with the river air. Light moved slowly across the table. I didn’t speak. I didn’t need to.

I just stayed, and listened to the room.

the study

The Study is a quiet, layered space for concentration, memory, and observation. Positioned along the water’s edge, it offers a place for reading, writing, listening, or sitting in silence — alone or with others. Its atmosphere is shaped by the constant presence of the river, whose sound, smell, and reflection animate the room in subtle ways.

The space is organized into two halves: One side holds a double-height wall of books and shelving — creating a dense vertical presence of memory and material. The other side opens toward the IJ, with terraced levels of tables and seating that descend gently to a water terrace outside. The threshold between inside and outside is soft, offering direct access to the air, light, and sounds of the river.