A COURSE FOR JAKARTA DETOX CULTURE

Urbanism as a method to manifest circular culture

Urbanism as a method to manifest circular culture

Urbanism as a method to manifest circular culture

A spatial and governance strategy that shows it is possible to stop subsidence and pollution in a way that benefits riverside kampung communities in Jakarta at the same time.

This pilot makes use of a new neighbourhood structure with which large scale residual waterand waste flows are managed locally within the urban environment.

It helps current recycling practices scale up in an attractive way to ultimately become a valuable part of Indonesian culture.

Hannah Mei Lan Liem hannahliem@gmail.com

Graduation project

Master Urbanism

Academy of Architecture, Amsterdam

May 28th 2025

Committee members

Jeroen de Willigen (Mentor)

Pauline van Roosmalen

Jossep Frederick William

Extended (external) committee members

Markus Appenzeller

Herman Zonderland

Head of Urbanism

Anna Gasco

* Alle afbeeldingen, tenzij anders aangegeven met (cijfer) in de ondertitel en bron in de bibliografie, zijn eigen werk en dienen vertrouwelijk te blijven.

Ze mogen niet worden gedeeld of gepubliceerd door enige persoon of entiteit, behalve voor het specifieke doel van de Academie van Bouwkunst.

Markets

Dear reader,

With this letter I would like to introduce my graduation project called ‘A Course for Jakarta DETOX culture’ In this project I connect a landscape regenerative water- and waste strategy to the growth of economical- and educational opportunity for (low income) communities in the inner-city riverside villages of Jakarta, called ‘Kampungs’. This is important not only for the communities themselves, but also for the urban metabolism of Jakarta.

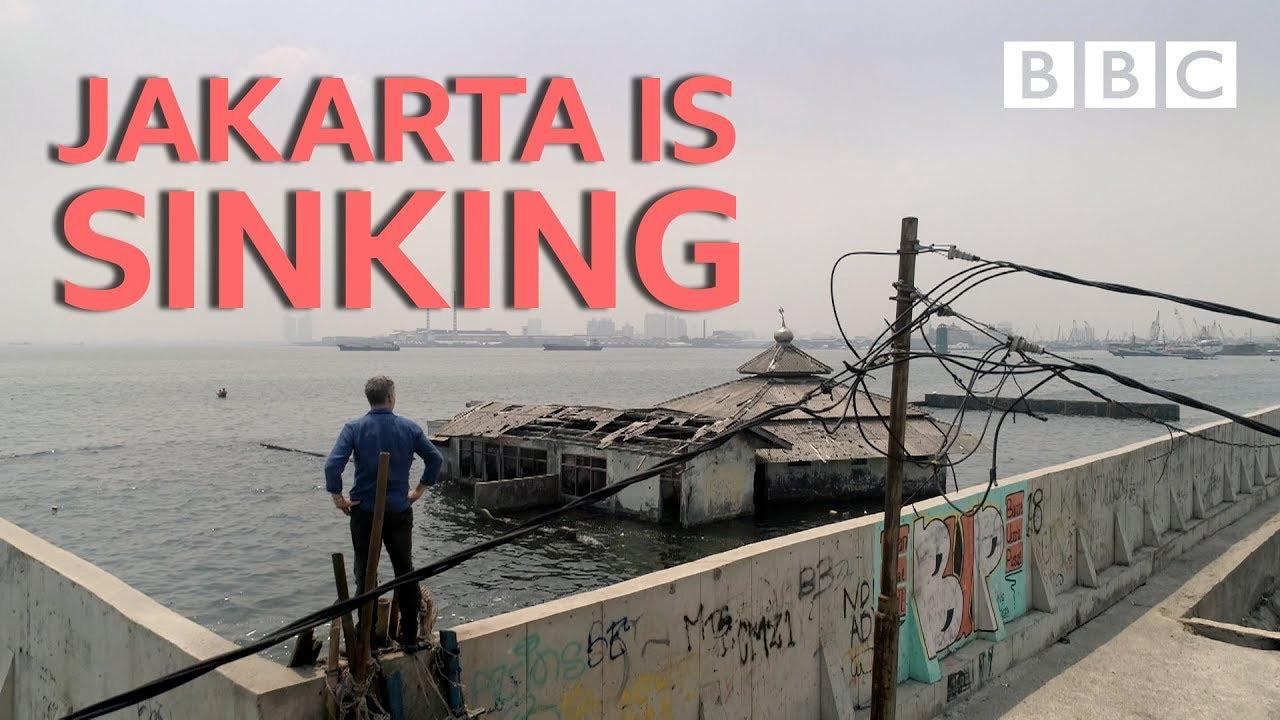

Jakarta is sinking, Jakarta floods, Jakarta has safe water scarcity, Jakarta was the most polluted city in the world in 2023 for a while, Jakarta is developing at a fast pace and the government seems to overlook long term social and environmental effects of these interventions.

There are three large scale developments that are endangering Jakarta’s working-class and lower-income communities of urban villages called ‘Kampungs’. My graduation research examines the social and governance structure of kampungs in general and their symbiosis with other urban structures in Jakarta. It answers the question of why these villages are under threat, what unique role they play in Jakarta and what their challenges are.

One of the three large scale developments threatens riverside communities (which are among the oldest of Jakarta). Namely: the flood mitigation method called ‘Normalisation’. It’s a term used to describe the widening of rivers and adding concrete encasement to riverbanks to increase the flowrate of rivers when a disastrous flood is predicted.

Normalisation is a suboptimal way to manage the flooding issue. It tries to battle the outcome of disastrous flooding, but doesn’t address the cause of it. The cause and answer to flooding lies in the management of waste and available water. There is an incredible amount of waste produced on a daily basis and it is insufficiently managed at the source, which causes people to dispose of their waste directly into the environment, for example by throwing it into rivers, thus creating severe flood problems. Because of normalisation inhabitants of riverbanks that depend on their surrounding community are evicted, the river dynamics are affected, causing soil erosion and damages downstream and the ability of the river to sustain a river ecosystem is destroyed. Another negative effect of normalisation is a type of fast-gentrification it sets in motion.

Normalisation is not only speeding up the river, but triggers the degradation of communities and the environment and it is exemplary for the way other large scale developments are handled and impact Jakarta. Which leads me to the following diagnosis: Jakarta is in a TOXIC spiral and is in desperate need to ‘DETOX’ its development and environment.

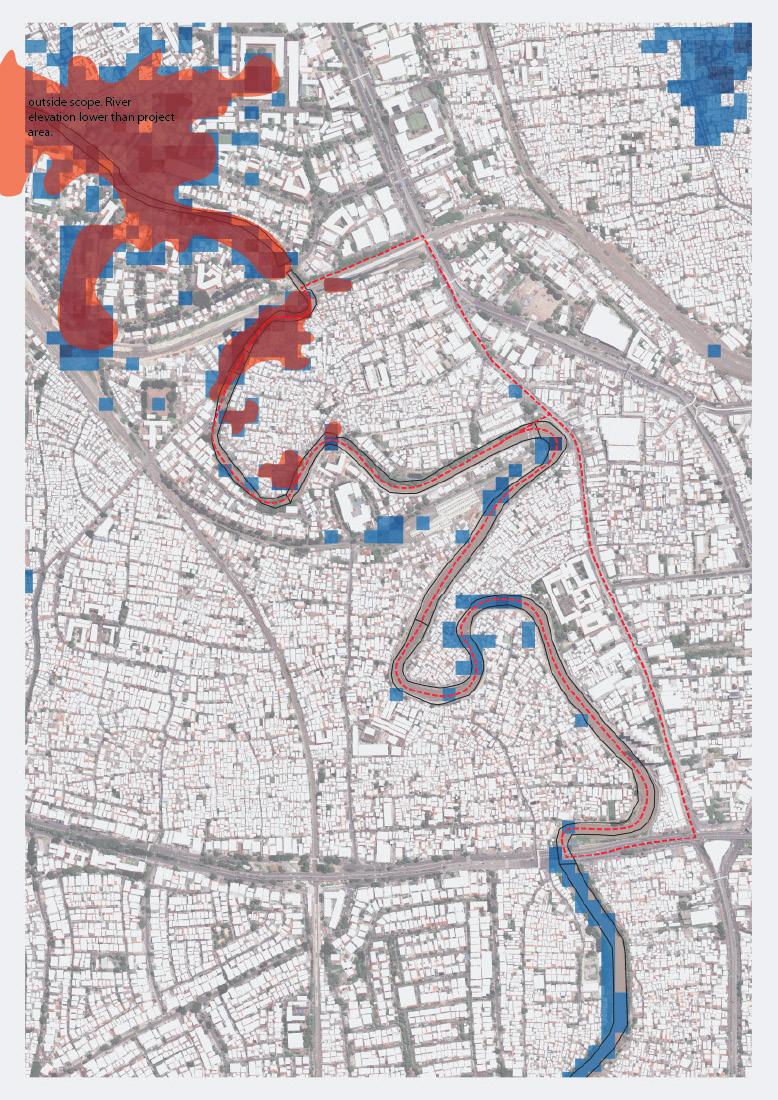

My design aims to DETOX current normalisation plans. It zooms in on one of the riverside villages that will be affected. The village is called Kampung Melayu. In my project I examine how this Kampung -which uncoincidentally is next in line to be ‘normalised’- can: (1) mitigate floods, (2) set a course to tackle Jakarta’s waste problem by stimulating the already existing recycling behaviour, (3) restore the river by making a by-pass, (4) create opportunity for its inhabitants by making space and means to add value to waste collectively, (5) empower community organisations to govern this new economy and (6) not trigger fast-gentrification by choice of governance, housing typology and limited car accessibility. For all of this, both a spatial design and governance strategy is made. Which I explain in 7 steps to DETOX.

My main design research question is:

With which spatial and governance water- and waste strategy can the current normalisation plan be adapted to stimulate recycling culture in Kampung Melayu, to stop groundwater extraction for household use, reduce pollution and empower its inhabitants?

To me the added challenge was to create such a pilot project that could inspire other inner-city developments and to imagine a way to integrate DETOX culture into Indonesian culture. The added question that I’ve tried to answer with my design, in context of the other two large scale developments is: “How can spatial design manifest DETOX culture in such a way that it becomes part of every-day-life and makes people connect to it on a personal level.“

I believe that in order for DETOX culture to integrate into any culture that everyone needs to want to be a part of it. And I believe I have created a project that could potentially do that. (And if my calculations are correct, it’s also proven quantitatively.)

So with this project I hope to show that it is possible to battle Jakarta’s many problems: sinking, disastrous flooding, safe water scarcity and inequality, through solutions that are Jakarta-style. It required careful examination of potentials in Jakarta and its people, through desk research, interviews and a month long trip to Indonesia with my dad. And ended up in a course that layers all explored potentials and empowers people and organisations, to ultimately integrate DETOX practices into culture through urbanism.

I wish you happy readings!

Best,

Hannah Liem Groningen, 2025-05-21

DEAR READER

INTRODUCTION

THE ICING ON A LAYERED SPICE CAKE - A JOURNEY THROUGH URBANISM

JAKARTA FACTS

JAKARTA’S GEOLOGICAL MAKE-UP JAKARTA FACTS JAKARTA GOVERNANCE

ANALYSES

OVERVIEW

1. JAKARTA IS DROWNING IN POLLUTED WATER AND WASTE

2. POTENTIAL POTABLE WATER COMES FALLING FROM THE SKY IN GREAT AMOUNTS BUT ISN’T PUT TO USE

3. JAKARTA SHOWS THE BEGINNING OF A RECYCLING CULTURE, BUT IT NEEDS SPACE AND ORGANISATION TO GROW

4. JAKARTA IS YOUNG AND FULL OF POTENTIAL

5. JAKARTA ROUGHLY CONSISTS OF TWO URBAN ENTITIES: THE KOTA AND THE KAMPUNG

6. THERE IS AN URBAN SYMBIOSIS BETWEEN KOTA AND KAMPUNG

7. COMMUNITY HAS AN URBAN FORM: THE KAMPUNG

8. JAKARTA HAS GREAT COMMUNITY ORGANISATIONS THAT CAN INNOVATE!

9. GOVERNMENTS ARE FOCUSED ON LARGE SCALE DEVELOPMENTS

10. THE FAST PACE DEVELOPMENTS FORM A THREAT TO KAMPUNG COMMUNITIES

THE DIAGNOSIS: JAKARTA IS TOXIC

JAKARTA HAS MANY INTERCONNECTED DIFFICULTIES

THE GOAL: DETOX JAKARTA

WHAT ARE THE GOALS AND METHODS OF DETOX-ING?

HOW TO DETOX DEVELOPMENTS COMMUNITY-STYLE?

DETOX GOALS AND STRATEGIES

METHODS

HOW TO DETOX

DEVELOPMENT BRIEFS

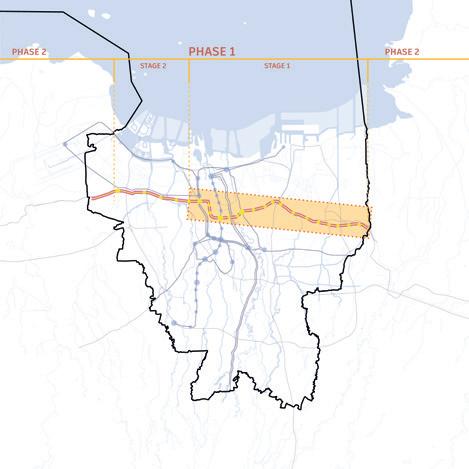

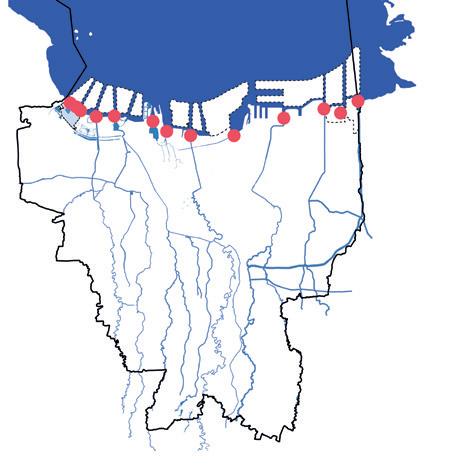

DEVELOPMENT 1: BRACKISH MANGROVE COAST

DEVELOPMENT 2: PRODUCTIVE RETENTION PARKS

DEVELOPMENT 3: RIVERSIDE DETOX COURSES

PILOT PROJECT

MAIN RESEARCH QUESTION

ANALYSES

THE DESIGN

7 STEPS TO DETOX

OVERVIEW

CHANGE THE GOALS OF THE CURRENT DEVELOPMENT

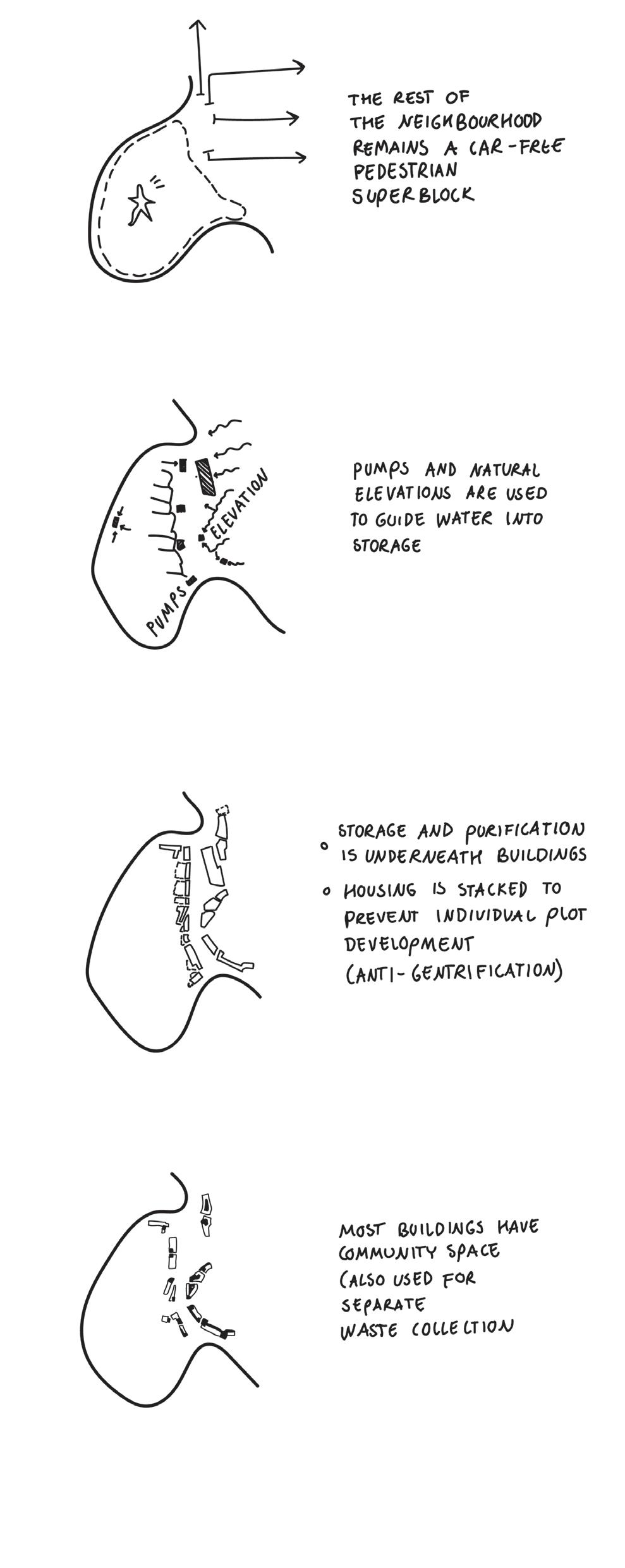

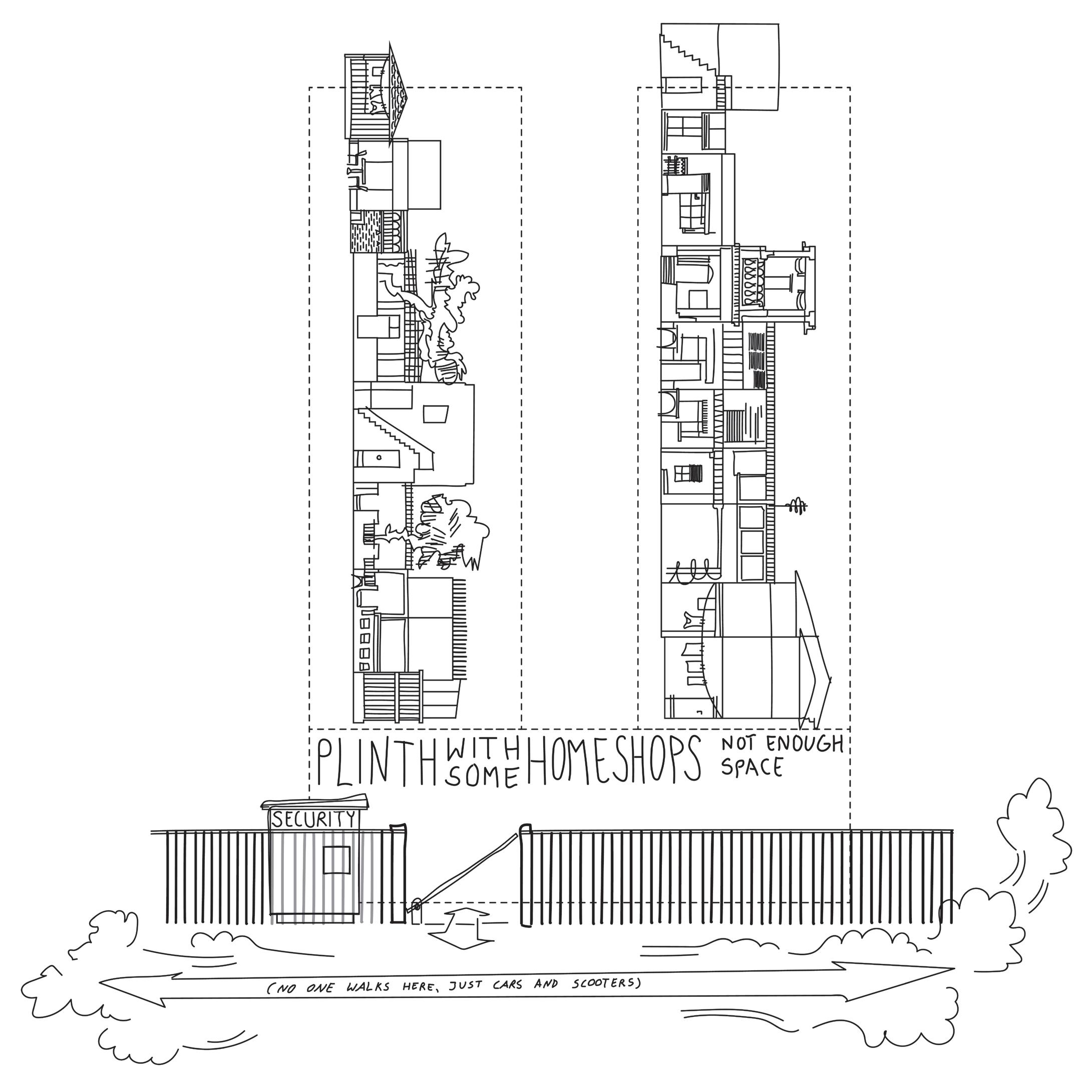

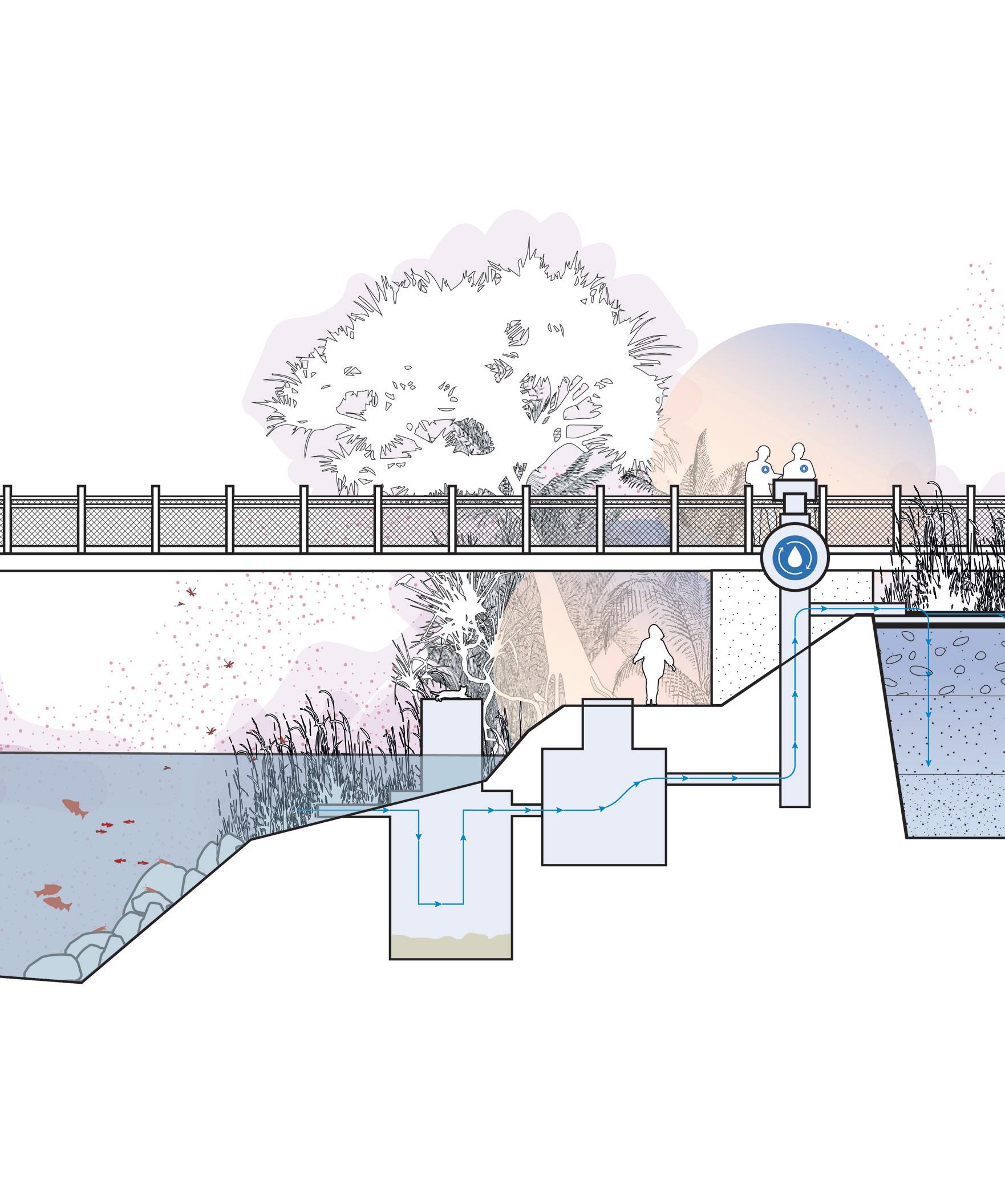

STEP 1: CHANGE THE COURSE OF NORMALISATION AND MAKE IT CLOSABLE

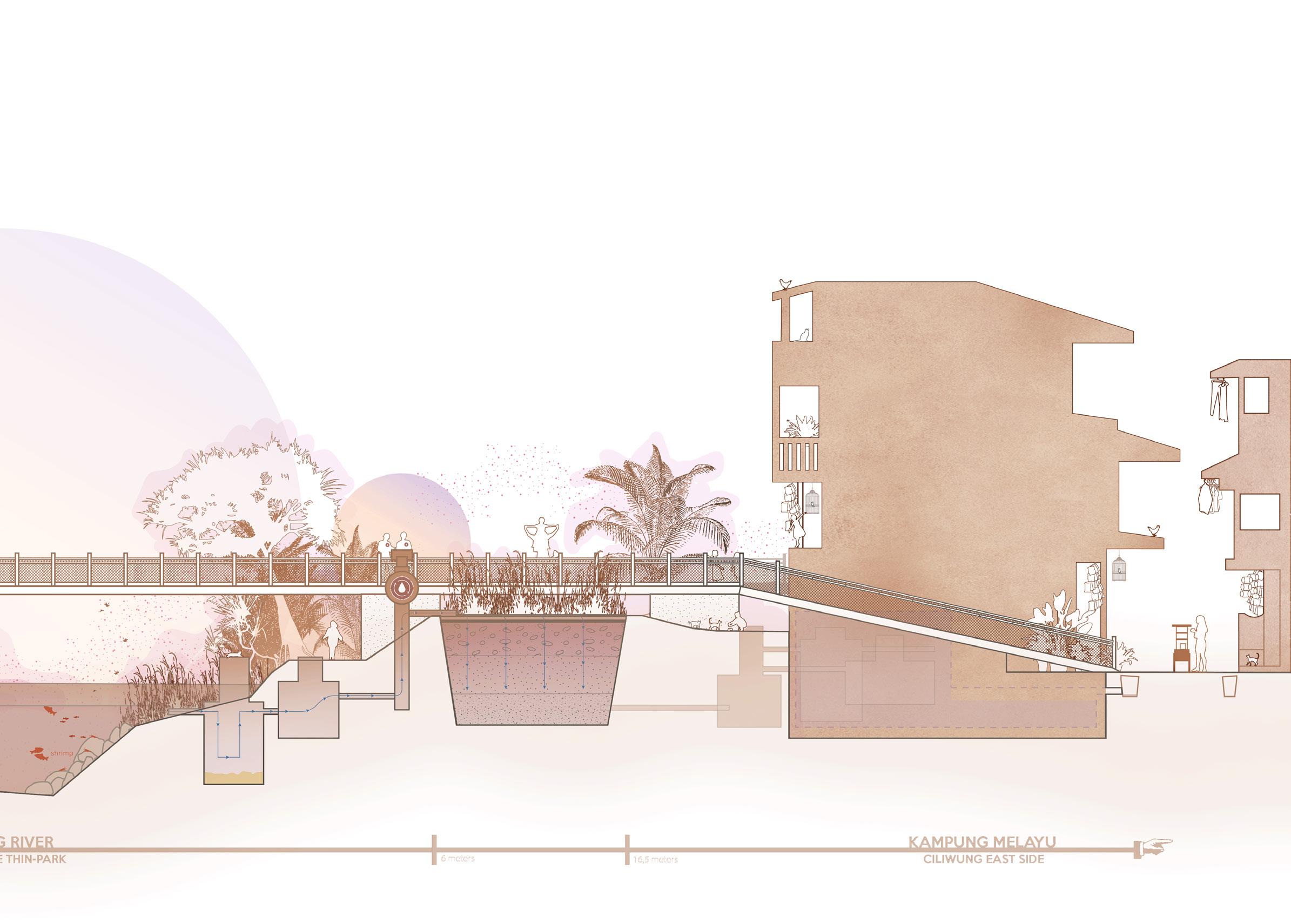

STEP 2: MAKE THE COURSE A CONNECTIVE SPACE BETWEEN NEIGHBOURHOODS

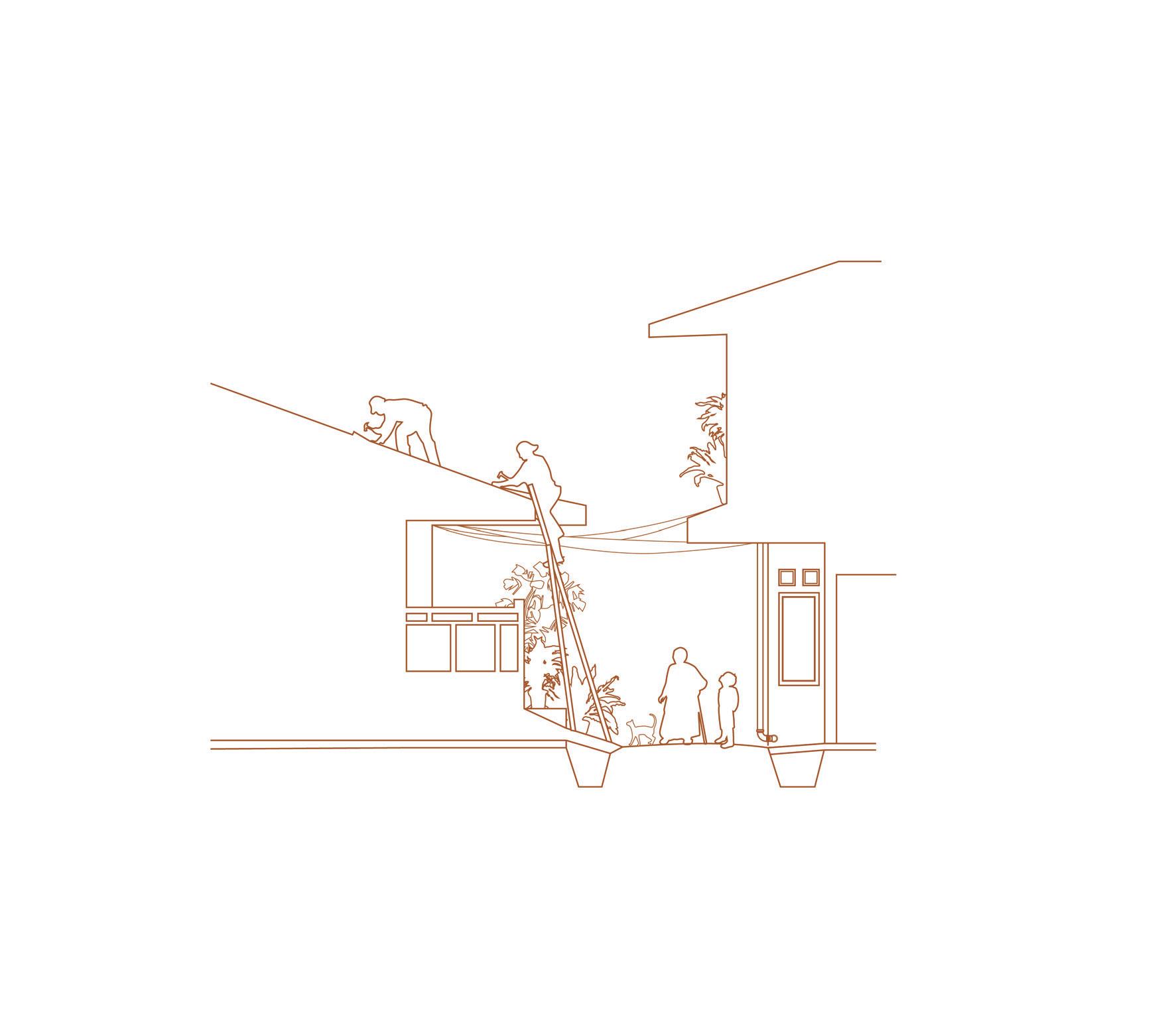

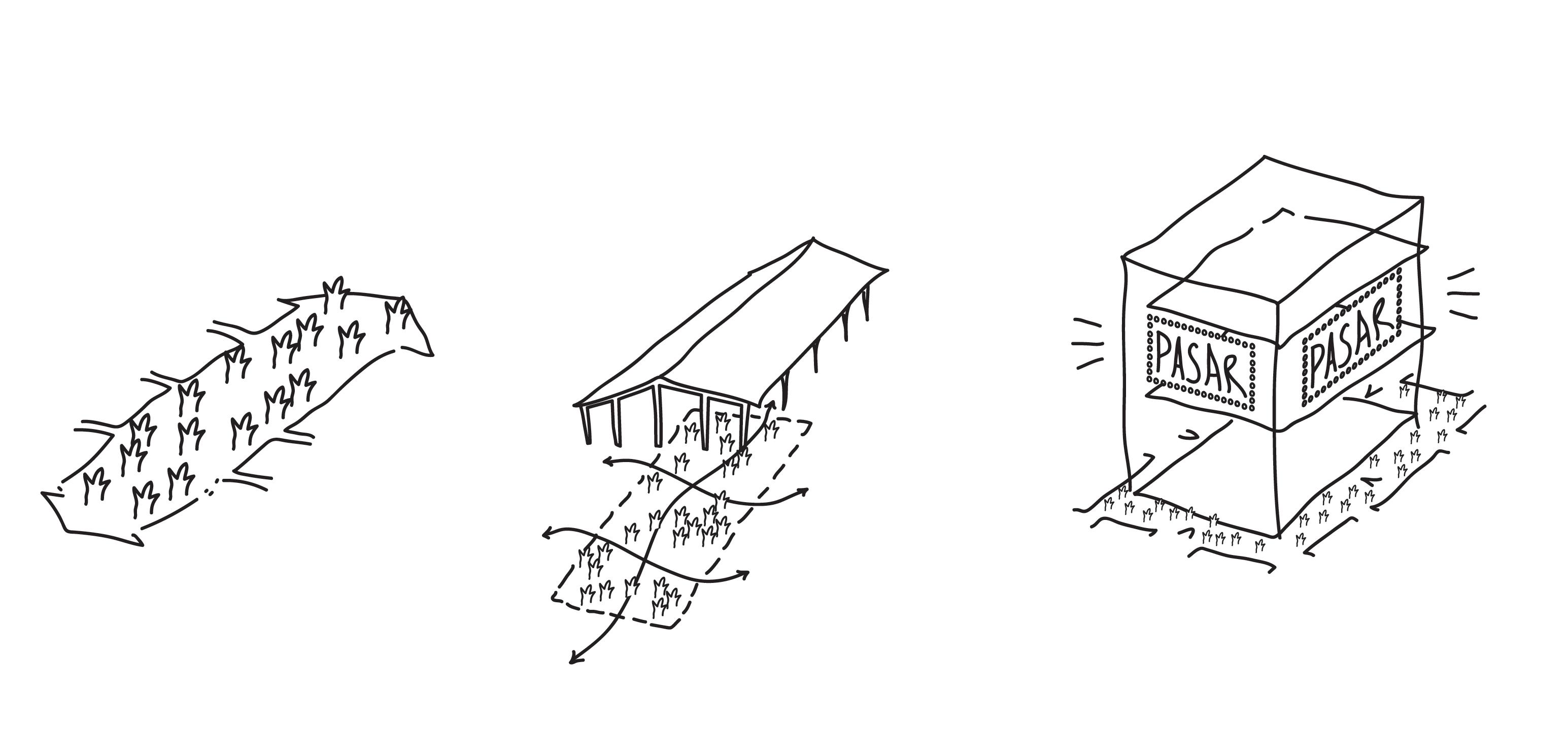

STEP 3: ADD A PIONEER BUILDING FOR COMMUNITY DETOX INITIATIVES AND A FACTORY: ‘PASAR DETOX’

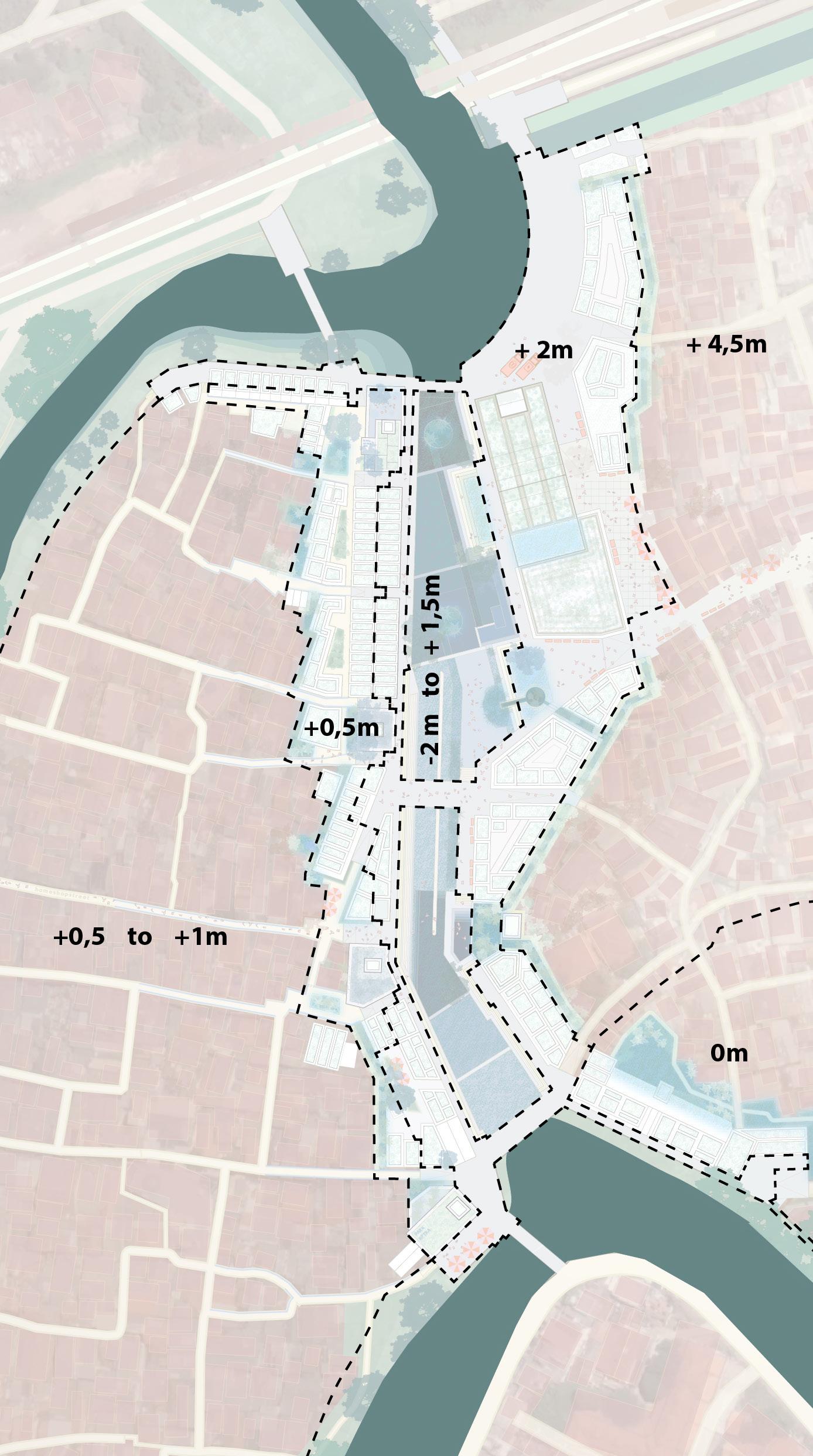

STEP 4: USE ELEVATIONS AND PUMPS TO GUIDE RAINWATER TO THE COURSE

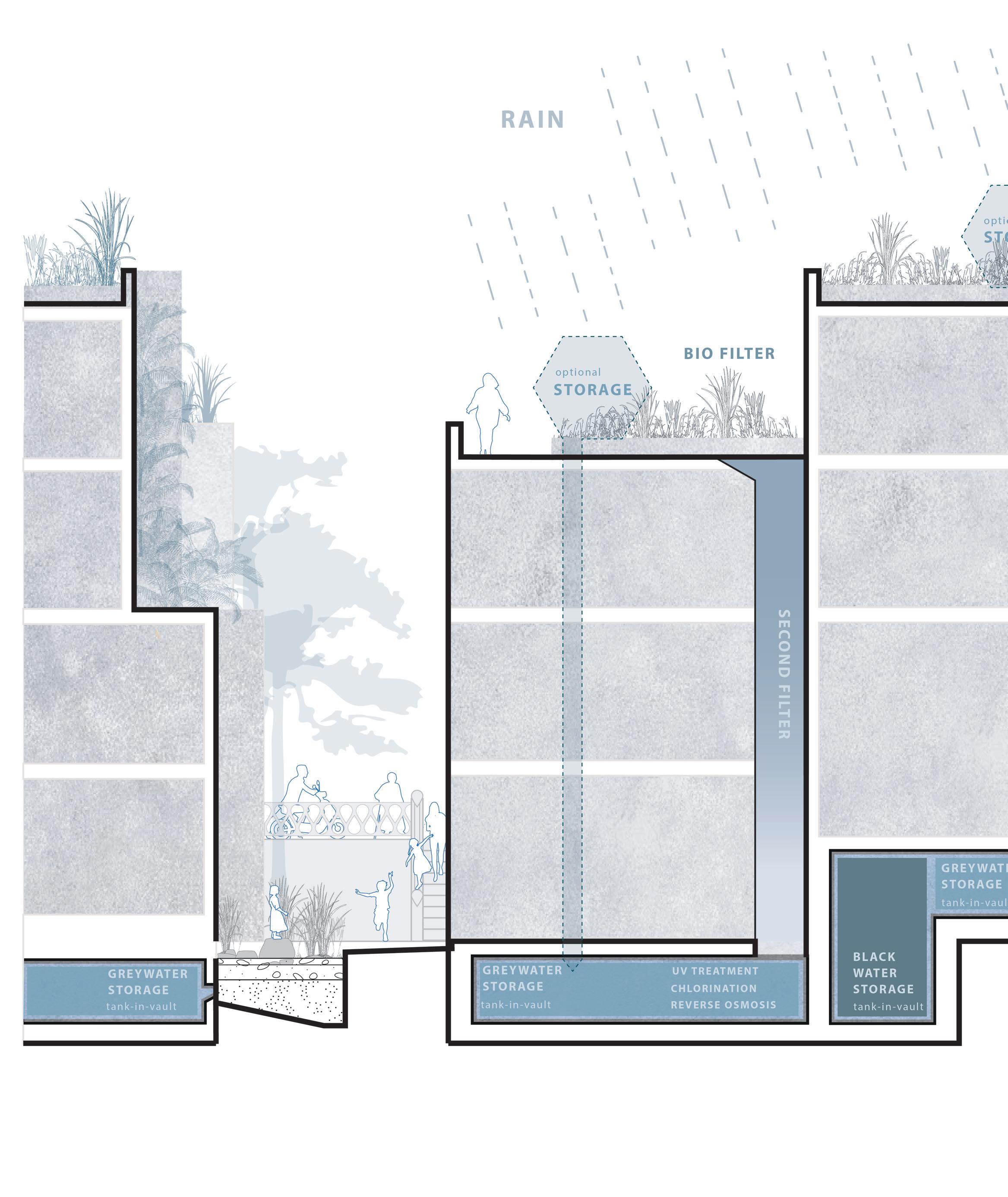

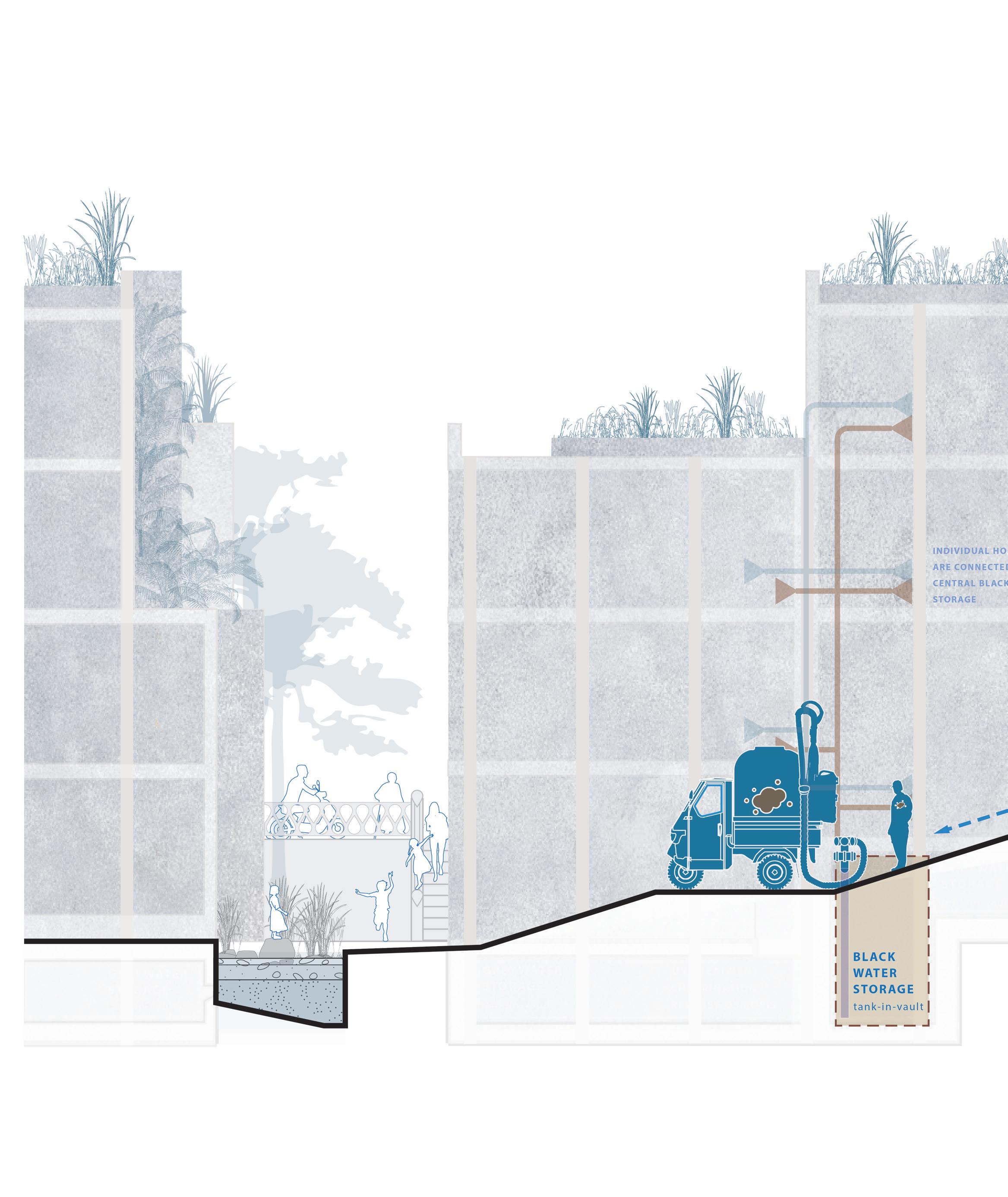

STEP 5: USE BUILDINGS TO HELP PURIFY AND STORE WATER FOR THE WHOLE PROJECT AREA

STEP 6: MAKE HOUSING EQUITABLE AND FIT FOR KAMPUNG COMMUNITIES

STEP 7: MAKE DETOX ARCHITECTURE BECOME PART OF EVERY-DAY-LIFE TO HELP IT BECOME CULTURE

SUMMARY OF THE PROJECT THE MAQUETTE THE DETOX COURSE

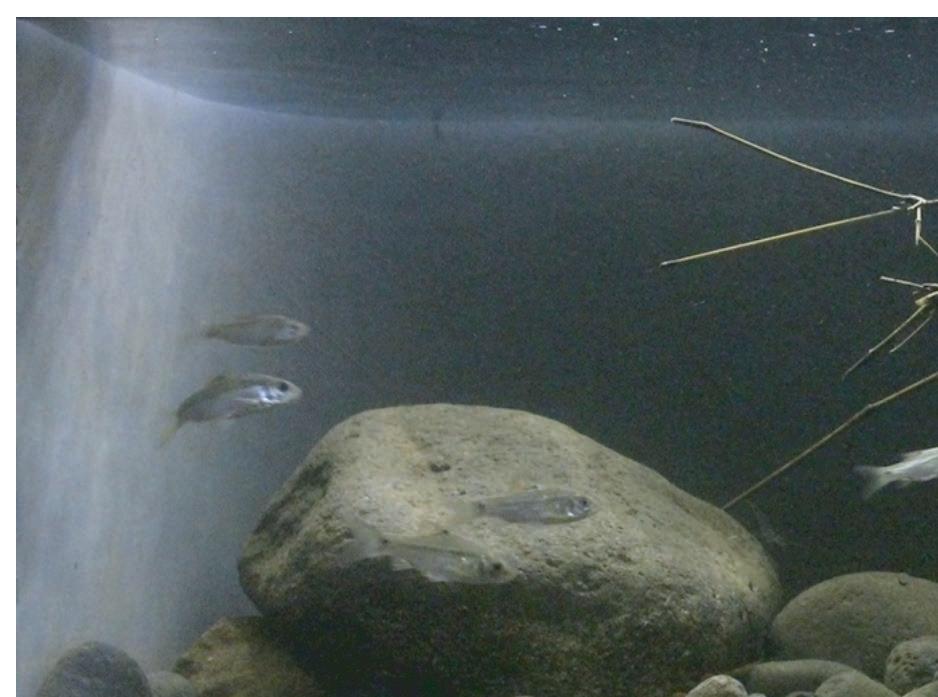

A HEALTHY CILIWUNG RIVER

MAINTAINING ‘FREE’ SPACE

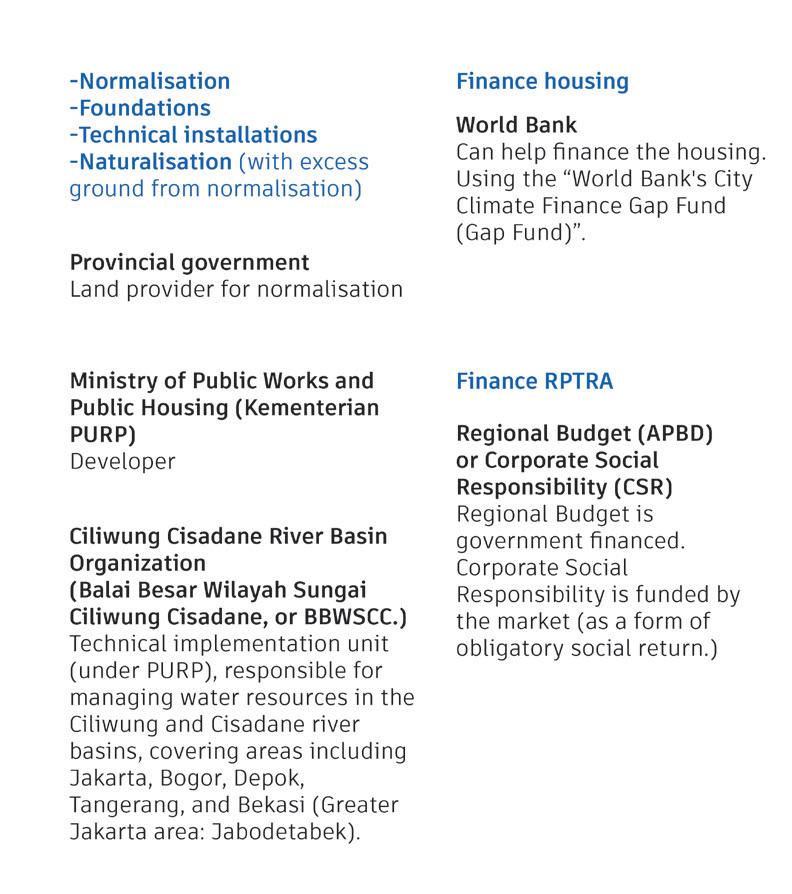

WHO DOES WHAT?

RESPONSIBILITY IN DEVELOPMENT

SHORTLIST OF LOCAL ARCHITECTS

CHECK ON THE NUMBERS IS THE PLAN PLAUSIBLE

LESSONS AND REFLECTION

OUR JOB AS DESIGNERS

LESSONS TO MANIFEST DETOX CULTURE

LESSONS ON SPATIAL INTERVENTIONS IN JAKARTA

EXTRA’S WATERCHARTS

FLOODCHARTS

PLANTS WITH BENEFITS AND WÁTER PURIFICATION

CASCADE OF DETOX ECONOMY

LESSONS ON SOCIAL DYNAMICS

SOURCE LIBRARY

A BACKGROUND, POSITIONING AS AN URBANIST, A PERSONAL MOTIVE AND GOAL

‘The icing on a layered spice cake’ was the title of my graduation proposal and is now the personal introduction of my graduation book. As this title suggests, I view my graduation project as the closing chapter of my time as a student at the Academy of Architecture Amsterdam. The spice cake or ‘spekkoek’ nods at the layers of themes, tools and methods I’ve learnt, fused together with part of my Chinese-Indonesian roots, while the icing or ‘kers’ promises a grand finale to my academic track. In preparation of graduating I asked myself what kind of designer I am, what I would like to learn from this last project and what I want to contribute to our field of work. To look forward, I will first look back at my time at the Academy.

SAME GOALS. CHANGING CONTEXT. CHANGED URBANISM.

I look back at three years of imagining hopeful futures beyond my lifespan. These futures each depict possible regenerative relationships between humanity and nature and amongst humans themselves. In the broadest sense I believe urbanism should aim for a restorative balance between humanity and the environment, design common ground between segregated communities and design for social resilience. Over the years this goal has had many different faces in my projects, corresponding with their potential to their surroundings and defining what this goal could mean spatially at different scales. I learnt early on that the context in which we design is becoming increasingly complex. It changes rapidly because of technological developments and short-term political decisions with long-term (even cultural) impact.

BLIND SIGHTED BY CLIMATE CHANGE.

Climate change demands different systemic transitions. The agriculture-, energy-, resources-, building-, water management- and mobility transitions all move in pillared systems. They each have spatial claims. At this rate in 2050 we would need about three planets to sustain our ways of living. Seeing as we only have one planet, this seems to be a bit of a problem. The sheer presence of these pressing matters seems to overshadow the importance of focusing on transitioning in an equitable way. Let alone that we could tap into the social sensitivity to foresee the long-term effect they and other technologies and trends have on our societies, on our culture, and in essence on ourselves: humans as social beings. Coming from a place close Groningen’s gas bubble, I have seen inequitable development in the name of fossil fuels, but sadly also in the name of cleaner ways to produce energy.

GENERATION REGENERATION.

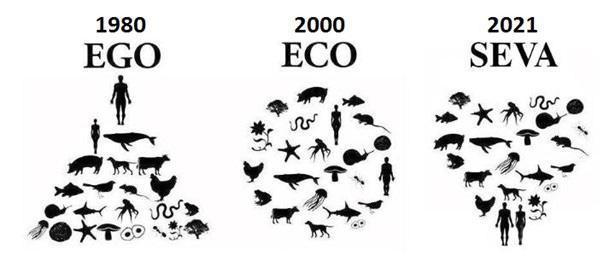

In the past three years I’ve tried to push the boundaries of urbanism. I aimed to find ways to connect systems of multiple pillared transitions to their geographical potential to spark a regenerative process. Through my designs I try to discover how people can benefit from necessary transitions, but also how I can strengthen our relationship to our surroundings and to one another by design, to invoke a cultural change and to add to a shared identity, which I fear humanity is losing in multiple parts of the world.

THE JOB OF THE URBANIST: BRIDGE

Urbanism should in my opinion always aim to surpass the physical goals of transitions (or if you prefer: transformations). We have to bridge the gap between the ‘Anthropocene’ and the regenerative future. We should imagine ways we can shift current toxic social dynamics towards regeneration, not only show a picture of what a preferred future could look like. If we confine ourselves to spatial goals, we might forget who it is we need to cross that bridge, in order to make the preferred future happen. The easy part is drawing a pretty picture. The difficult part is to align incentives and interests and persevere for realization. I strongly believe this type of systemic transitional design thinking must make a difference in the world today. We need to help regeneration become culture, by design.

IT’S REVOLUTION PLANET. NOT REVOLUTION GLOBAL NORTH.

To understand the method of ‘bridging’, you have to understand how people work. But in western society we seem to be far removed from what makes us human. This is probably why I’ve often found inspiration in stories, in art and technology of all ages and especially in far-awayplaces. But I had never actually designed for such a place myself. For my graduation project I decided it was time to do so, to see if I would be able to. With our previous Academy moto “Revolution Planet” in the back of my mind and curious as I am, I took this opportunity to set myself a new challenge to discover a part of the world in which the destructive effects of climate change and social conflicts are very much part of everyday life.

My project is based in Jakarta, which is currently the capital of Indonesia. It is uncoincidentally also a place of great personal significance. My dad is from Indonesia, from a city named Bandung 153 kilometers to the south east of Jakarta. I have many relatives living in both Bandung and Jakarta. My dad and I visited Indonesia together in November 2023 for my graduation research. This was my introduction to my family, my father’s place of heritage and the diversity in Indonesian culture. To me this was the real ‘kers op de taart’ and it influenced my understanding of space and people greatly. I hope my love and admiration for the country and its people shines through the chapters of this book.

With this final chapter of my academic track, I wish to unify the systemic world I’ve discovered with my background as a sculptor, to see how it could help manifest regeneration with urbanism.

I have always been fascinated by the way space influences people and it scaled up over time.

From teaching arts and sculpting -> to my dream of building my own house and starting a study in building and mechanics -> To a traineeship turned policy maker -> returned to design in urbanism, so I could figure out to which extent space could influence people. The research into impact of space on people has always been focused on sparking people’s ‘zelf-ontplooiing’ capacity (There is no good english word for this). Spatial design can be, both the solid base and the cherry on the cake in the lives of people. It can help to unlock individual potentials, spark creativity and imagination with each built environment, to bring opportunity to people’s lives. Space has its limits, but space can emphasize what is important. I will look for this emphasis.

WHAT IS JAKARTA’S GEOLOGICAL MAKE-UP JAKARTA FACTS

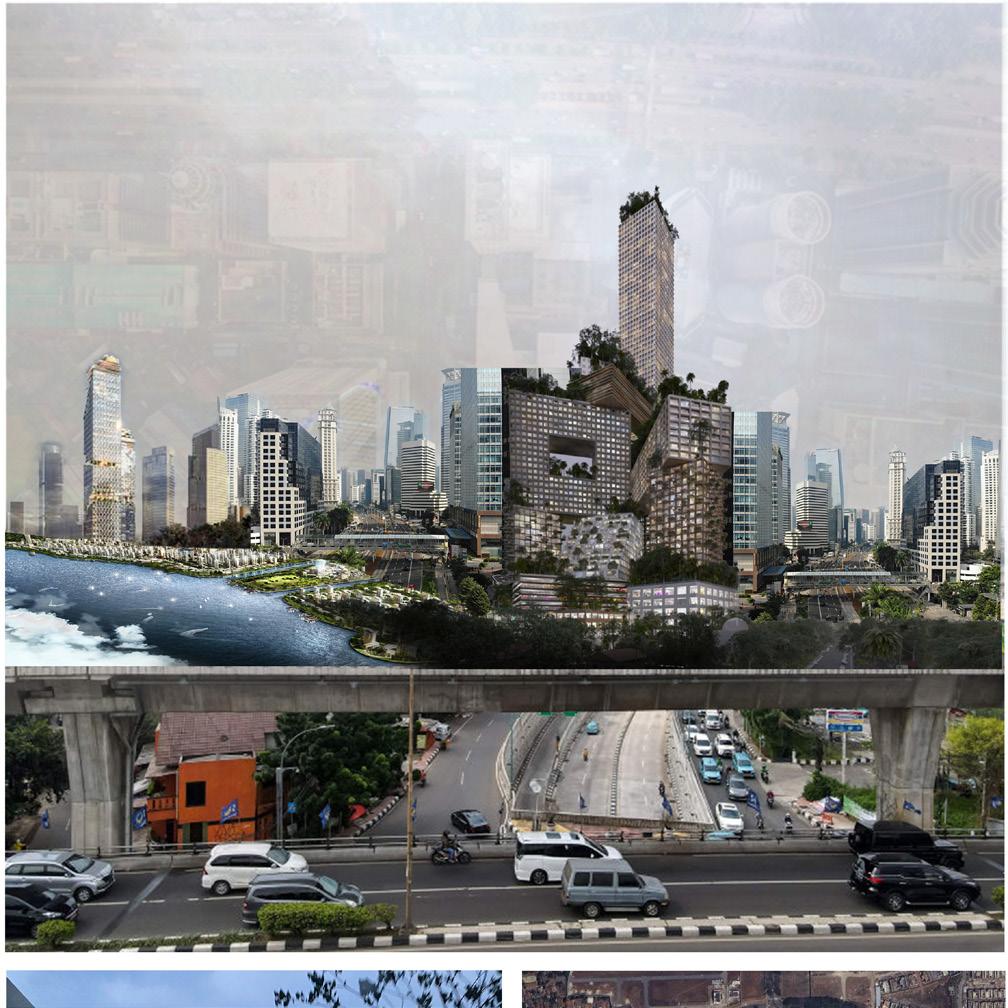

HOW IS JAKARTA DEVELOPING SPATIALLY?

WHAT IS JAKARTA’S GOVERNANCE STRUCTURE?

AN ALMOST FULLY URBANISED PROVINCE

Jakarta is an almost fully urbanized province located in West-Java, on Java island. It is 661,23 square kilometres in size and about 11,6 million people live within its provincial boundaries. It is the economic, cultural and political centre of Indonesia.

It is part of the metropolitan region ‘Jabodetabek’. Jabodetabek is 7076.31 square kilometres in size and houses about 34 milion people, making it the second largest urban area in the world. The only one bigger than it is the greater Tokyo area. It houses around 37,5 million people.

Volcanoes tothesouthofJakarta

The young landscapeformed10,000 -12,000years

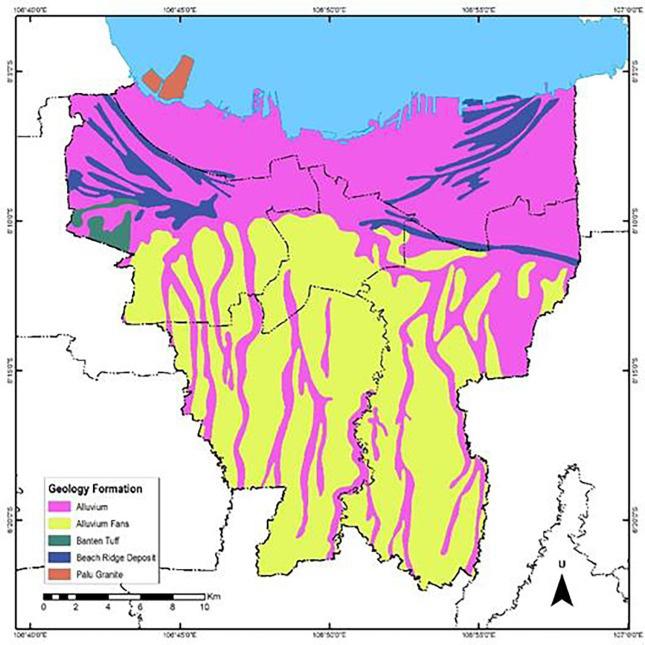

Jakarta’s geological structure is the result of its natural setting, tectonic history, and long-term sedimentation processes. Jakarta lies on the northern coastal plain of Java, a region shaped over millions of years by the combined forces of volcanic activity, rivers, and the sea. The land has formed gradually over thousands of years from layers of mud, sand, and soil transported by rivers from the volcanic mountains. These rivers carry material from the highlands south of Jakarta and spread it across the coastal plain. Over time, these layers built up and created the soft ground on which Jakarta developed. The main geological processes that shaped Jakarta are explained below.

The island of Java formed along the borders between IndoAustralian Plate and the the Eurasian Plate. The Indo Australian Plate subducted the Eurasian Plate and this tectonic interaction has created volcanic activity along central Java. most volcanoes are active and have erupted over time. The weathering of their rocks continues to supply sediment to the surrounding landscape. Volcanic ash, sand, and gravel are transported by rivers to the north, and this material forms the foundation of Jakarta’s surface geology. The most important volcanoes contributing to this process are Mount Gede and Mount Pangrango near Bogor, Mount Salak south of Bogor, and Mount Tangkuban Perahu near Bandung. Mount Papandayan and Mount Guntur, located farther southeast, are also part of the same volcanic system. Jakarta itself is not located near any major faults (fractures in earth’s crust), which is why the city rarely experiences strong earthquakes.

Source: Environmental profile West Java, 1986

Jakarta’s connection to the Java Sea has also shaped its geology. Fine sand and silt left behind by changing sea levels have created layers of marine sediment across the coastal plain. This mixture of river material and marine deposits makes the ground soft and saturated with water.

For thousands of years, rivers such as the Ciliwung, Cisadane, Krukut, and Bekasi have transported large amounts of eroded volcanic material toward the Java Sea. As these rivers slow near the coast, the sediment they carry settles and accumulates, forming thick layers of alluvial deposits. These deposits consist of unconsolidated mixtures of clay, silt, sand, and gravel. The result is a soft and relatively “young” surface geology that defines Jakarta today. The uppermost layers of the city’s geology are only thousands of years old, rather than millions, which is considered very young in geological terms.

The surface layers beneath Jakarta, composed mostly of river (alluvial) and coastal (deltaic) sediments, were deposited during the Quaternary period, the most recent chapter of Earth’s geological history. The Quaternary covers the last 2.6 million years, but most of Jakarta’s surface sediments were laid down during the Holocene, which encompasses the last 10,000 to 12,000 years. During this time, rivers continued to carry volcanic material from the highlands, and sea levels rose and fell repeatedly.

Source above images: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0048969708008164 (2024/02/11 18:59)

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/a-Geological-overview-of-Greater-Jakarta-b-Elevation-profiles-of-each-city-within_fig1_381927245 (2024/12/08 21:03)

11.6 million inhabitants 661,23 km²

34 million inhabitants 7076,31 km²

Expansion in a triangle

Jakarta’s economy: Manufacturing industry Food industry Seaport

Jakarta’s itself is 661,23 km² in size. Its metropolitan area covers 7076.31 km². The area has been developing in a triangular shape since the ‘80s, growing more land-inward, scattered along infrastructure and in between mountains.

From 2010 on, Jakarta’s development has sprawled considerably. Adjacent cities are growing towards Jakarta. Together they create the metropolitan area called: JABODETABEK. This metropolitan area includes the cities of Bogor, Depok, Tangerang and Bekasi.

The connection between DKI Jakarta and its surroundings is strengthened by many infrastructural projects, like the highspeed railway called the ‘Woosh’ as well as multiple new train and metro lines around the city.

In recent years elevated toll roads have been constructed to reduce travel time by car. Bus lanes and special motor lanes (and sometimes also cycling lanes) have been implemented on ground level.

THE JAKARTA PANCAKE

Jakarta consists mainly of dense low-rise neighbourhoods and has high-rise in the central business district, along axes that lead there and around commercial centres and destinations. Its low-rise density follows the main river structure, flood zones and historic centres.

Often commercial ‘third place’ destinations in or on the border of dense low-rise areas are of a larger scale and have multiple levels. I’ve come across some old markets or ‘pasars’, which developed from an open market area, into a multi-level department store. The streets surrounding these department store markets are often filled with similar small-scale shops and various market stalls. (Pasar Baru Bandung; Pasar Jantinegara Jakarta; Traditional market in Grogol/West-Jakarta)

HUMID CLIMATE ALL YEAR ROUND

Jakarta has a tropical monsoon climate. Which means it is hot and humid with year-round rainfall. There is little fluctuation in temperature throughout the year varying between 31 °C and 22 °C. Humidity in Jakarta varies between 61% to 95% and the average rainfall amounts to 218.4 millimetres (mm) per month. The “wet” season occurs between November and April. During this period as much as 388 mm rain can fall per month. Wet season counts 15 to 20 rainy days per month, with showers usually lasting 2 to 4 hours. June through September are typically dry. Dry season counts about 3 to 8 rainy days per month, with showers usually lasting less than 1 hour. Between 50mm and 150mm of rain falls per month.

The area is quite fertile for fruit and other horticulture, as most of the soil is of old volcanic origin.

Source: https://www.city-facts.com/jakarta-raya/population (2024/05/07 20:40)

‘Third place’ is defined as a social environment/destination that is separate from the place of living and the workplace. They are ankers of community life and facilitate a broad range of interactions. The third place is somewhere you go to relax, meet familiar faces as well as new ones. Ray Oldenburg introduced the term ‘third place’ in his book ‘The Great Good Place’ in 1989. Also describing the social significance of the third place for social engagement, democracy and creating a sense of place.

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1423886/indonesia-jakarta-population-by-gender-and-age/025/04/05 (2023/12/07 19:50)

Source: https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/netherlands-population (2023/12/07 21:05)

Sub-neighbourhood

Kampung Melayu (also) 11 717 inhabitants

Neighbourhood/Kelurahan

Kampung Melayu 23 260 inhabitants

District/Kecamatan

Kecamatan Jantinegara 263 706 inhabitants

City/Kota

Jakarta Timur 3 million inhabitants

Province/Provinci

DKI Jakarta 11.6 million inhabitants

By no means is this fragment aimed to give a full summary of historic events in Jakarta. Only a few necessary fragments are explained to give enough background information to understand the administrative levels in Jakarta and to later be able to give the location for my design project relevant context.

Jakarta is one of the oldest cities in Southeast Asia. In the fourth century a settlement established, called Sunda Kelapa in what is now known as Jakarta Bay. It became an important trading port for the Sunda Kingdom.

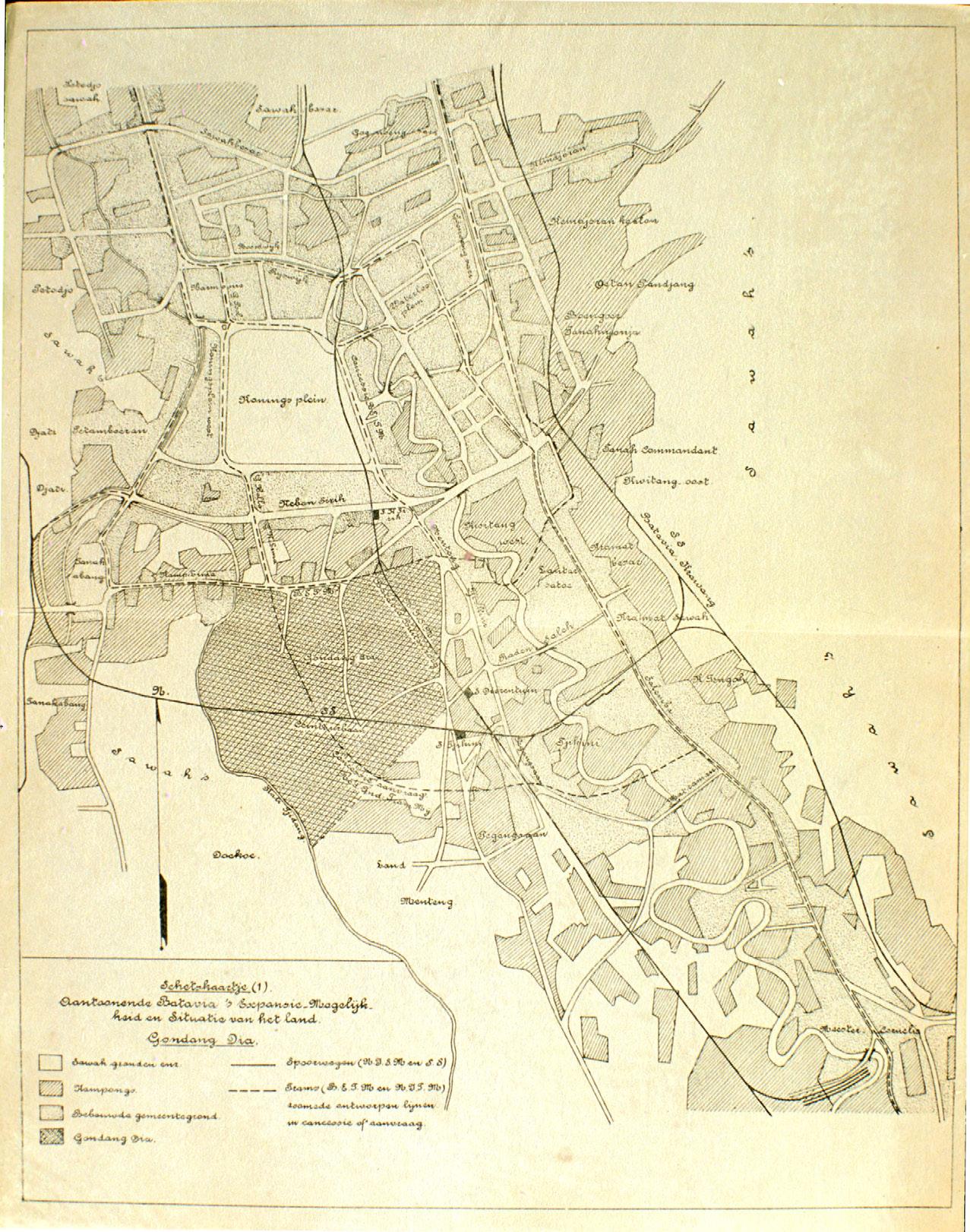

During the Dutch occupation it was renamed Batavia and became the capital of the Dutch East Indies. In 1949 when Indonesia achieved full independence, four years after declaring independence, Batavia was renamed Djakarta.

In 1960 Jakarta’s official status as a city transformed to province with a special autonomous status: capital district, or daerah khusus ibukota (DKI) Jakarta.

In 1999 the central governance in Jakarta decentralized into regional governance. Which meant that most functions of the government moved to the rural districts and municipalities. Two levels of regional government were enabled to make their own policies and local laws:

- Province (provinci) ADM1.

- Regencies (Kabupaten) and Municipalities (Kota)ADM2.

DKI Jakarta consists of 5 administrative cities and one regency: Jakarta Barat (west), Jakarta Utara (north), Jakarta Pusat (central), Jakarta Timur (east), Jakarta Selatan (south) and the thousand island regency in the Java Sea. These cities are divided in districts (kecamatan), which consist of neighbourhoods or villages called (kelurahan), of which the keluargha is the chief.

As a result of the ‘Orde Baru’, otherwise known as the ‘New Order’, which Suharto instated between 1966 and 1998, two supervised divisions in neighbourhood governance were established called Rukun Warga (RW), meaning ‘community unit’ and Rukun Tetangga (RT), meaning neighbourhood unit.

An RT typically consists of 10-20 households, while RW consists of 5 to 10 RTs. An RT could resemble a housing block community. These neighbourhood associations operate under government supervision and bring democratic community organisation into neighbourhoods. Members elect leaders, organize meetings and participate in bottom-up decision-making.

They are used to improve the daily lives of the community and fall into two categories (Hataya 1999): ‘life strategy oriented’ and ‘development strategy oriented’.

Trying to understand an almost fully urbanized province is an overwhelming task. In November 2023 I had the chance of a lifetime to travel through Jakarta with my dad. To grasp Jakarta’s urban dynamics and experience its culture I visited many places with our family. Our family kept us on our feet, not a day was spent without exploration. They made sure I saw every type of urban living environment in Jakarta.

Day five of our 30 day journey, and I’ve already seen most types of urban structures.

I’ve seen many inhabitants, from no- to low-income communities, to lower-middle, to middle to uppermiddle to upper income communities, to gated castle communities within golfc ourses..

Source: https://www.city-facts.com/jakarta-raya/population – City Facts: Jakarta Raya population (2024/05/07 20:40)

Source: van Reybrouck, D., Revolusi, 2022

Source: Interview with the lurah at community center Dwijaya

A projection of the future sealevel shows half of Jakarta under water.

Groundwater along the coast is undergoing salinisation.

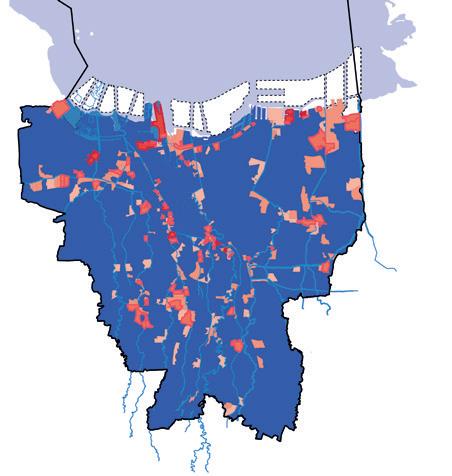

The potential to infiltrate rainwater and stimulate the growth of the deep underground aquifer is mainly found in the areas south of DKI Jakarta. South Jakarta and river areas show little to no infiltration potential (purple). Around Central Jakarta (light blue), the infiltration of water into the shallow aquifer could help reduce salinisation. (turquoise)

Industrial areas are mostly located in the north and east, near ports and major roads for easy transport. The city’s central and southern parts are mainly residential, commercial, and government areas. Smaller patches of industry are logically situated along roads and canals.

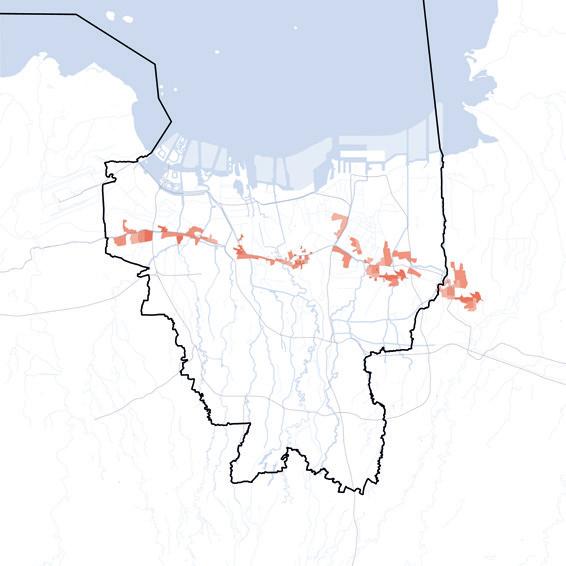

Informal settlements are mainly found in flood-prone northern and eastern areas, they are often located between formal roads and industrial zones.

MANY CONCLUSIONS!

OF WHICH 10 (OR 11) ARE EXPLAINED IN DETAIL

l y s e s

JAKARTA IS DROWNING IN WATER AND WASTE

JAKARTA IS SINKING FAST

JAKARTA’S WASTE SYSTEM ISN’T COPING

JAKARTA FLOODS FLOODS AREN’T ALWAYS CONSIDERED DANGEROUS

JAKARTA SHOWS THE BEGINNING OF A RECYCLING CULTURE. MAINLY IN NO-INCOME TO LOW-INCOME COMMUNITIES 1

WASTE PICKERS INPUT THE MOST INDIVIDUAL EFFORT, BUT PROFIT THE LEAST FROM RECYCLING

Groundwater IS A HEALTHRISK

3

RECYCLING EFFORTS CAN BE MORE PROLIFIC

POTENTIAL POTABLE WATER COMES FALLING FROM THE SKY IN GREAT AMOUNTS BUT ISN’T PUT TO USE

2

NO-INCOME AND LOWINCOME COMMUNITIES ARE SCATTERED ACCROSS JAKARTA AND CONTRIBUTE TO A CLEANER ENVIRONMENT

RECYCLING NEEDS SPACE AND ORGANISATION TO GROW

THERE IS UNEXPLORED POTENTIAL IN PEOPLE

JAKARTA ROUGHLY CONSISTS OF TWO URBAN ENTITIES: THE KOTA AND THE KAMPUNG

4

JAKARTA IS YOUNG, WITH AN AVERAGE AGE OF 28 YEARS OLD

THE NO-INCOME AND LOW-INCOME COMMUNITIES ARE RESOURCEFUL

THERE IS AN URBAN SYMBIOSIS BETWEEN KOTA AND KAMPUNG

JAKARTA HAS GREAT COMMUNITY ORGANISATIONS THAT CAN INNOVATE!

COMMUNITY HAS AN URBAN FORM: KAMPUNGS

6 5 9 8 7 10

FLOOD MITIGATION METHOD ‘NORMALISATION’ IS THE MOST IMPACTFUL THREAT

GOVERNMENTS ARE FOCUSED ON LARGE SCALE DEVELOPMENTS

LARGE SCALE FAST PACE DEVELOPMENTS FORM A THREAT TO KAMPUNG COMMUNITIES

FOCUS ON THE WORKINGCLASS AND IMPOVERISHED COMMUNITIES

COULD HELP CHANGE A HARMFUL SOCIAL DYNAMIC

11*

JAKARTA’S DEVELOPMENT IS TOXIC AND NEEDS TO DETOX

above: maps showing Kelurahan (village administration units) in which part of the village administration unit was reported to be inundated in the (a) 2007 and (b) 2013 floods. Below: Inundation simulations (using SOBEK model, hydrodynamic simulation tool) based on (c) 2007 schematization and a return period of 50 years, and (d) 2013 schematization and a return period of 25 years.

A return period of 50 years means a flood of that magnitude has a 1 in 50 (or 2%) chance of occurring in any given year.

A return period of 25 years means a flood of that magnitude has a 1 in 25 (or 4%) chance of occurring in any given year.

FLOODING IS A NATURAL OCCURENCE

Jakarta is situated in the natural catchment area of Jakarta Bay. which means it is part of its natural floodplain. Flooding is a natural occurrence in this area.

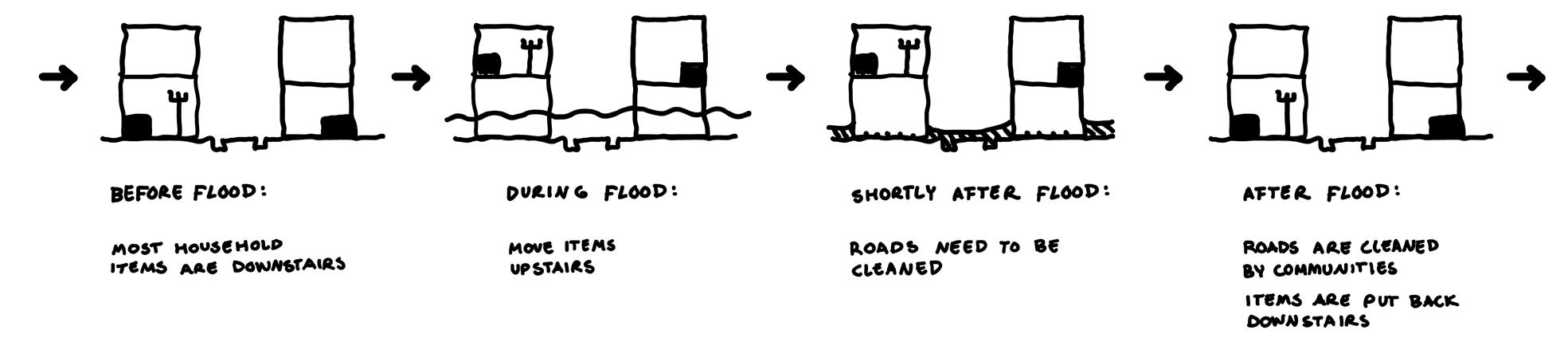

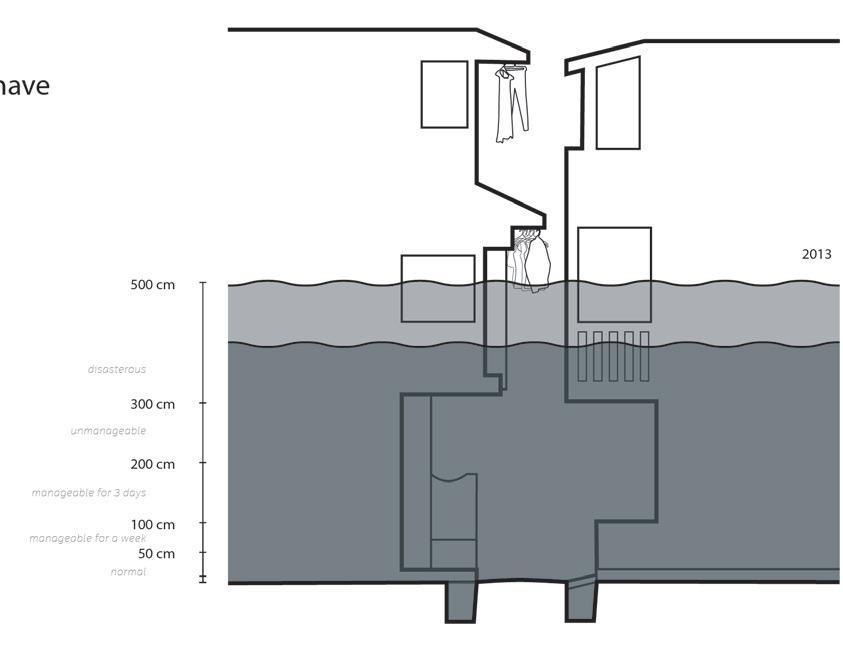

FLOODING IS BUSINESS AS USUAL

The level of ‘normality’ is visible in riverside communities that live in inner city villages, called ‘Kampungs’. These communities organize themselves in cases of flooding. When a flood is announced, personal belongings are transported from ground level to the first floor of dwellings. During the flood, usually the ground floor is affected. Debris from the river is scattered across the area, which usually means there is a lot of rubbish and silt in the direct living environment at ground level. When the flooding is over the community works together to clean up the neighbourhood. Belongings once again decorate the ground level of dwellings.

DANGEROUS FLOODINGS HAVE BECOME MORE FREQUENT

In recent decennia floods of over 4 meters have become more frequent. With this type of flooding the choreography as explained before will not help, because they also affect the first floor.

Floodings in 2002, 2007, 2013, 2020 have been disastrous.These types of flooding are predicted to occur once every 5 to 7 years during raining season. Flood levels are elevated because of urbanisation upstream. Urbanisation causes the landcover to become impermeable, which means rainwater can’t infiltrate into the ground.

In 2007 in a few days 400mm rain fell. Which couldn’t run off properly and caused flooding of 4m high all around the urban area. At least 340 000 people had to leave their homes.

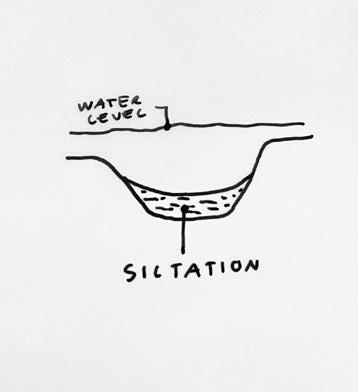

Another cause is poor waste management. The central waste collection services doesn’t cover all of Jakarta, so people either burn their waste, or discharge their waste in rivers. This way their waste is able to make its way to sea. Organic waste causes siltation of riverbeds. It forms a layer of sludge on the riverbed, which gradually makes rivers more superficial and reduces their discharge rate. Inorganic waste piles up and clogs rivers. These waste accumulations degrade the river ecosystem, preventing soil organisms from establishing themselves. The absence of these organisms obstruct the growth of vegetation that stabilizes riverbanks, making them more susceptible to erosion. This degradation initiates a downward spiral, where the affected ecosystem intensifies erosion and further deteriorates river health.

CHANGE OF BEHAVIOUR NECESSARY TO STOP FLOODING

A change of behaviour is necessary, but can only be stimulated by giving a good alternative to the root issue of a bad waste system. Without a good alternative to disposing waste in rivers or burning waste, people won’t be able to change this habit.

Notonlytrash,alsosanitarywaste. Ecolibacteria=publichealthissue

Source maps: National Disaster Management Office (BNPB) Source bottom image: 2252-3767-2-PB.pdf (utwente.nl) 2024/09/25 9:21

Streets that are otherwise dominated by cars or motorcycles and streetvendors turn into grand playgrounds

If only the water could be safe to play in.

One thing that struck me when I was visiting Jakarta is the way the environment changes because of theflood. for children The attraction of a vast open area toplay, is greater than the fear of becomingillfromfloodwater.

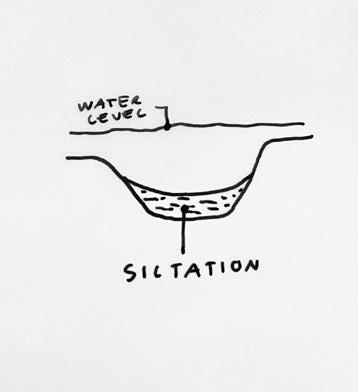

Research in riverside Kampung Melayu has shown that flooding happens frequent. In this research the manageability of floods is measured, based on their floodheight. They’re divided into normal floods, manageable floods, unmanageable floods and disastrous floods. A flood duration of 1 to 3 days with a waterlevel of 10cm to 50cm is considered normal. This type of flooding stays manageable even if the duration exceeds 7 days. A flood duration

of 1 day with a waterlevel of 51cm to 100cm is considered normal. They are considered manageable within a duration of 7 days. They become unmanageable when they last longer than a week. Floods between 101cm and 2 meters high are manageable to a duration up to 3 days. They become unmanageable if they exceed a duration of 3 days. Floods of 3 meters or higher are considered disastrous.

Image: This graph projects the results of multiple research papers and a survey held in Kampung Melayu in 2008. The survey adresses the level of manageability during flooding. An assumption I’m making is that the new outlet of riverwater from the ciliwung to cipinang and the eastern flood canal which was compleded between 2017 and 2021 has effect on flood levels in Kampung Melayu, Pulo, Bukit Duri and further downstream. I assume ‘it won’t get any worse’.

Once every 5 to 7 years a disastrous flood occurs.

Source information on scheme: Marschiavelli, M.I.C., Vulnerability assessment and coping mechanism related to floods in urban areas: A community-based case study in Kampung Melayu, Indonesia, Gadjah Mada University International Institute for GEO-information Schience and Earth Observation, 2008, p.p. 40-44

Source top image: Alamy stock image, Jakarta, Indonesia. 21st Feb, 2017.

Deep underground aquifer Recharges ver y slowly

Shallow underground aquifer

LACK OF ACCESS TO PIPED WATER SOURCE CREATES DEPENDENCY ON Groundwater

Unstable ground makes an underground piping system less effective, and can cause septic tanks to leak, which infects the groundwater supply.

SINKING WITH A SHRINKING AQUIFER

Jakarta is sinking aproximately 20 cm per year due to land subsidence, a process in which ground gradually collapses. This phenomenon is primarily driven by the depletion of Jakarta’s underground aquifer, caused by an inbalance between excessive groundwater extraction and the much slower process of natural aquifer recharge.

HOW TO REPLENISH THE AQUIFER?

There are two ways to help replenish the aquifer: increasing supply and reducing extraction.

Supply: Rainwater infiltration recharges the aquifer. Irrigation along the mountainous areas is particularly important, since these areas have high recharge capacity. Within the administrative boundaries of DKI Jakarta, however, there is little potential for recharge. Creating opportunities for water to infiltrate south of DKI Jakarta will help stimulate infiltration.

Demand reduction: Taking less water out of the ground is a more fitting strategy for DKI Jakarta itself. In the urban context—where there is little room for infiltration—replenishing the aquifer requires reducing groundwater extraction. This would directly mitigate subsidence. Of course, this is easier said than done, as most households rely on groundwater extraction.

THE RELIANCE ON GROUNDWATER

Jakarta consumes about 1.2 billion m3 of water per year. About 51% of which is extracted from the ground. Only about 49% is served by water utility companies. 60% of this amount is extracted for household use, while 40% is extracted for industrial use.

GROUNDWATER EXTRACTION IS BORN OUT OF NECESSITY

Groundwater extraction for household use is not a matter of choice, but a matter of void.

Firstly potable water can’t be extracted from surface water. Out of Jakarta’s 13 rivers, only the water from Krukut river is clean enough to purify into potable water, providing just 2.2 percent of Jakarta’s total clean water demand.

Secondly only 48% of Jakarta is connected to a piping system. The piping system is concentrated in the wealthier area of the city. This means a large part of the city relies on other ways to get water. Between 73% and 89% of Jakarta’s inhabitants use bottled water as their source of potable water and use groundwater for other purposes.

Thirdly current pipelines aren’t reliable. Residents are reluctant to use municipal water are because there is no guarantee on the quality, quantity and continuity of the piped water. The quality of the piped water is bad. The quantity during the dry season is very limited. And the supply continuity is irregular, particularly during the dry season.

Wells on the other hand never run out even during the dry season. And even though in recent times the government has announced the wish to connect every household to a reliable piping system by 2030, not every neighbourhood is able to connect to piping infrastructure because of ground instability.

Source: https://360info.org/how-jakarta-has-dug-itself-into-a-hole/ 2025/02/21:00

Source: https://theowp.org/why-is-jakarta-sinking/ 2025/02/16 22:24

Source: https://theaseanpost.com/article/managing-jakartas-water-related-risks 2025/02/16 22:45

Source: https://360info.org/jakarta-acts-to-stop-being-the-next-atlantis/ 2025/02/16 22:55

Source: Pemantauan Kualitas Lingkungan Air Tanah di Provinsi DKI JakartaTahun 2022, 2025/02/17 00:11

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/s0197397516306816 2025/01/12 12:11

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0197397516306816 2025/02/20 9:35

There is a shortage of about 600 million m³ water anually 622 million m³ water is supplied 51% of water used is

Groundwater extraction is difficult to stop, because it’s linked to necessary household use. Impoverished communities depend on groundwater.

4720 reported illegal wells in 2018

Urban development decreases rainwater infiltration

If pumping exceeds the rate of the aquifer’s flow, then a depression cone occurs.

This possibly has impact on groundwaterpumps. In this case the pump can’t reach the water anymore.

GROUNDWATER IS INCREASINGLY POLLUTED

45–90% of Jakarta’s shallow groundwater is contaminated by E-coli from wastewater. The degree of contamination of water from shallow wells varies according to the depth of well and the distance from septic tanks (Kosasih, Samsuhadi, & Astuty, 2009). The quality of shallow groundwater varies because of subsurface pollution and saline intrusion. Both pollution and salinity make shallow groundwater unusable for most uses, especially further north and closer to the sea (Delinom, 2008, Delinom, 2016). An added effect of subsidence is unreliable piping system and sanitation units. septic tanks are damaged because of subsidence, causing their contents to leak into the groundwater source.

THE JAKARTA SEWERAGE SYSTEM ONLY SERVES ABOUT 4% OF JAKARTA

It’s recently estimated that approximately 96% of Jakarta’s population lacks access to a centralized sewerage system, relying instead on alternatives like septic tanks or direct discharge into water bodies. The widespread use of septic tanks, many of which are poorly maintained or leaking, contributes to groundwater contamination and the degradation of river ecosystems. Without proper sanitation infrastructure groundwater is polluted, causing it to become unsafe for household purposes, even after purification methods like filtering and boiling.

Jakarta has initiated the Jakarta Sewerage System (JSS) project, aiming to divide the city into 15 zones for phased development of sewerage infrastructure. For example, zone 5 is planned to covers around 3,4ha and serves approximately 800,000 residents in North and Central Jakarta. But areas along the river edges are excluded from this strategy, because of ground instability.

A non-spatial solution can come from law enforcement. If the government enforces extraction restrictions, like the Japanese government did in Tokyo in the 1960s, subsidence can stop. Regulating illegal groundwater extraction is however not without consequence. Big industry can be regulated, but it would create a significant financial burden for individual households, forcing people to rely on -more expensive- bottled water. Enforcement is another challenge. In 2018 alone, authorities identified 4,720 illegal wells—raising the question of how many civil workers would be needed to monitor and regulate groundwater use effectively.

Instead of restrictive policies for household groundwater extraction, a more viable approach could be to develop alternative water sources and infrastructure that reduce dependence on groundwater.

The important lesson is that without addressing the root causes of water scarcity, limiting extraction alone will not be a sustainable solution.

Tokyo faced fast subsidence in the 1960s, when industries carried out uncontrolled groundwater extraction, resulting in cumulative land sinking of up to 4.5 meters in certain areas. Within a decade of declined groundwater pumping, the rate of sinking slowed dramatically and was permanently halted by the government in most areas. The water table rose even in the most affected areas and the rate of subsidence slowed to about one centimeter per year in five years.

Source: Article: “Some Jakartans denied clean piped water for decades”, Jakarta Post, 2024/05/1

Source: e3s-conferences.org 2025/05/17 9:50

Source: https://invest.jakarta.go.id/potential-projects/114/jakarta-sewerage 2025/05/17 10:23

1 person makes a total of 0,7kg waste per day.

11,6 million people make 8,12 million kg waste per day.

Household waste = 61% of Jakarta’s total waste

514 meters high pile of food waste

produce biogas produce compost

HOUSEHOLDS ARE THE LARGEST CONTRIBUTOR OF WASTE

With a waste generation rate of 0.7 kg/capita/day (Baqiroh, 2019), it is predicted that by 2035, the volume of waste in Jakarta will reach more than 9,000 tonnes per day (BPS, 2021). Municipal waste from households in Indonesia is the largest stream at 61%. The lack of overall public awareness in waste reduction efforts aggravates the situation.

The majority of waste isn’t separated at the source and a substantial amount of waste is directly dumped into open dumps or landfills. The main type of the waste generated in Jakarta is organic wastes with 53,01% (SIPSN, 2020).

Waste management in DKI Jakarta largely relies on collection, transportation, and disposal activities in a landfill. This landfill is called TPST Bantar Gebang in Bekasi. 8900 tons of unsorted waste is transported to Bantar Gebang on a daily basis. Waste management is carried out by local governments under the Environmental Agency (DLH). Temporary storage sites are established locally to reduce hauling distances for the collection trucks. This lowers transportation costs.

There are 1,006 temporary storage sites available in Jakarta (Putra, 2020). There is no waste treatment at these temporary storage sites. Waste is transported to waste trucks at the temporary storage sites. Next the waste is transported to intermediate treatment facilities (ITFs), waste banks, composting centres, or a landfill called Bantar Gebang.

Bantar Gebang is the second largest open air landfill in the world. It’s between 100ha and 104ha in size and between 45m and 50m high (Tempo, 2019). Picture a 15 storey building, which has the surface area of 200 football fields.

Living near open landfills is a significant health risks due to exposure to various pollutants and hazardous substances. Landfills emit harmful gases such as methane and hydrogen sulphide, which lead to respiratory issues, including asthma and bronchitis, and neurological effects like headaches and dizziness.

Residents living close to landfills have higher incidences of sore throats, eye irritation, and fatigue. Residents who live around the landfill are offered only 800 000 Rp (40 euro) per three months in compensation for having to live in proximity to the landfill.

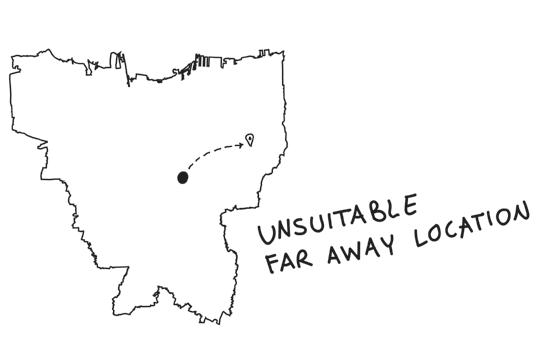

Bantar Gebang is reaching its maximum capacity, which is why the government is opening up a second landfill site in the near future. This new waste plant is planned in North Jakarta. It is communicated as a waste to energy plant. Refuse-derived fuel (RDF) is an alternative to fossil fuels. The Jakarta RDF Plant is the second attempt by the provincial government to convert waste into alternative fuel. A similar facility opened up at the Bantar Gebang TPST in 2023. The construction of the project is funded by the Regional Budget (APBD) 2024, and it is projected to become operational by 2025. This is the start of the city’s ambition to address the waste problem, reduce the tipping fees for Bekasi, and manage waste sustainably. It is feared that this new site will turn into a landfill like Bantar Gebang, which will spread pollution and affect nearby neighbourhoods. Attempts to adopt sanitary landfilling techniques have been unsuccessful, partly due to inappropriate designs and poor operational management (Shekdar, 2009). Governments are confronted with the need to reorganise the current system for the treatment and management of solid waste.

A new programme called Plastic Smart Cities (PSC) Programme WWF-Indonesia aims to reduce plastic leakage in nature by 30% by the end of 2025. This is done by building a large belt system in or near Bantar Gebang to sort waste. I interviewed Silvia de Vaan, co-founder of SweepSmart about the plans. From this interview I can conclude that a strategy for waste separation at the source is still missing, and won’t be focused on in the future. We talked about that waste should be treated at the source before transportation, to minimize its effect on the environment. The question is, how? And how to make it durable? What leads can I find that could influence waste at the source?

Source: https://www.kompas.id/baca/english/2024/05/13/en-kelola-2500-ton-sampah-per-hari-rdf-plant-rorotan-ditargetkan-selesai-akhir-2024

Source: https://en.tempo.co/read/1867125/jakarta-launches-rdf-plant-project-in-rorotan 2024/09/07 16:13

Source: https://www.thejakartapost.com/paper/2022/06/28/the-struggle-of-waste-banks-to-recycle-and-repurpose-trash.html 2024/09/07 17:05

Source: https://scholarhub.ui.ac.id/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1154&context=jessd 13:27 - 2024/02/04

Bantar Gebang is massive.

The current landfill lies between villages, covers an area of more than 200 football fields, and is over 45 meters high. The image on the left shows a scale comparison.

POTENTIAL POTABLE WATER COMES FALLING FROM THE SKY IN GREAT AMOUNTS BUT ISN’T PUT TO USE 2

Jakarta receives an average of 1755mm rainfall per year, or 143mm per month. It has a tropical monsoon climate, which means it rains most of the year.

On average there are 130 days per year with more than 0.1 mm (0.004 in) of rainfall (precipitation) or 10.8 days with a quantity of rain, per month. In comparison: In Amsterdam it only rains 850 mm per year.

Precipitation numbers vary throughout the year with an average rainfall of 67mm in August and 388 mm in Januari. 1mm rain, means 1 liter of water falls on a surface of 1 square meter.

A total of ≈ 1,162,389,150 m³/year (≈ 1.162 × 10⁹ m³) falls on Jakarta soil on average.

Rainwater in Jakarta is a good source for producing potable water, because it contains less dissolved salts, heavy metals, and chemical pollutants than surface or groundwater. Most of its impurities come from contact with the atmosphere or collection surfaces, which can be removed with simple, low-cost treatment.

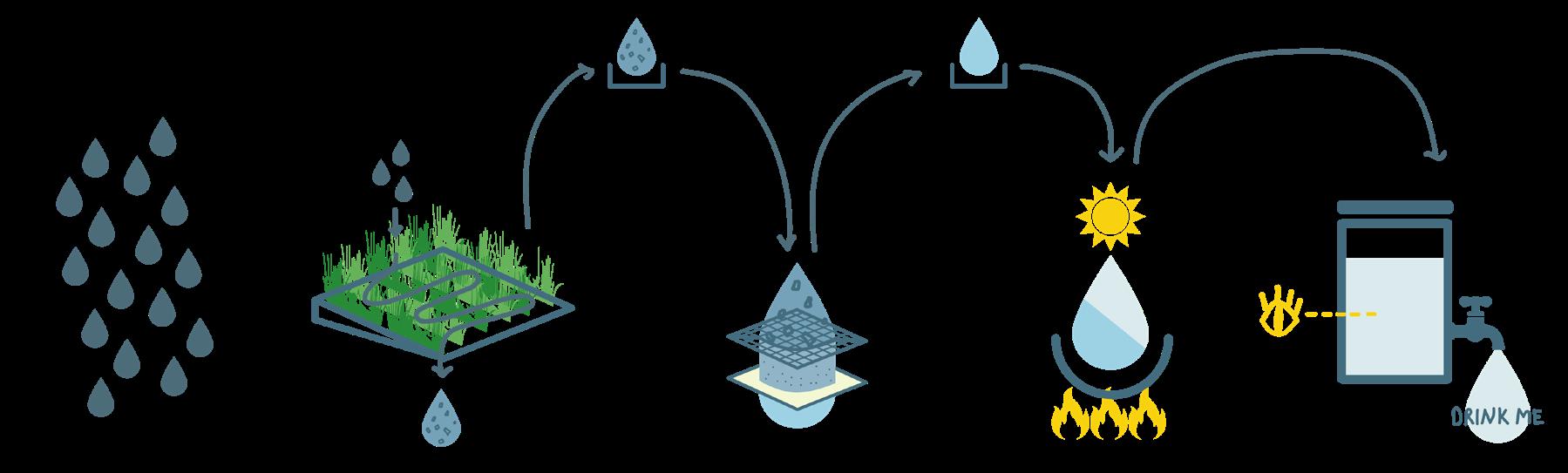

A natural and effective approach is the use of a helophyte filter system. First the initial runoff is diverted to prevent dust and debris from entering the system. The water is then allowed to pass through layers of sand, gravel, and charcoal. Particles and organic matter are filtered out and microorganisms are reduced by biological activity. Next exposing water to sunlight or ultraviolet light helps disinfect it and eliminate remaining pathogens. By combining these natural techniques, rainwater can be purified efficiently and affordably into safe drinking water suitable for Jakarta’s context.

Yes, collecting and purifying rainwater could potentially solve Jakarta’s drinking water problem, but not in all scenarios. With small-scale collection (5% catchment), rainwater only covers 7–13% of daily needs, so around 88–93 L/day would still need to come from other sources. With moderate collection (20% catchment), coverage rises to 30–50%, leaving about 49–71 L/day unmet. In the most ambitious scenario (50% catchment with typical or optimistic efficiency), rainwater can fully meet or even exceed daily needs. This is an exciting goal, but it may be unnecessary, since Jakarta can already provide roughly half of total household water demand through their piping system.

Source: https://www.climate.top/indonesia/jakarta/precipitation 2023/09/11 12:15

Source: https://www.knmi.nl/over-het-knmi/nieuws/de-hoofdmoot-van-de-jaarneerslag 2023/09/11 15:15

JAKARTA

THE BEGINNING OF A RECYCLING CULTURE, BUT IT NEEDS SPACE AND ORGANISATION TO GROW

RECYCLING IS PICKED UP BY LOW-INCOME COMMUNITIES ALL OVER JAKARTA

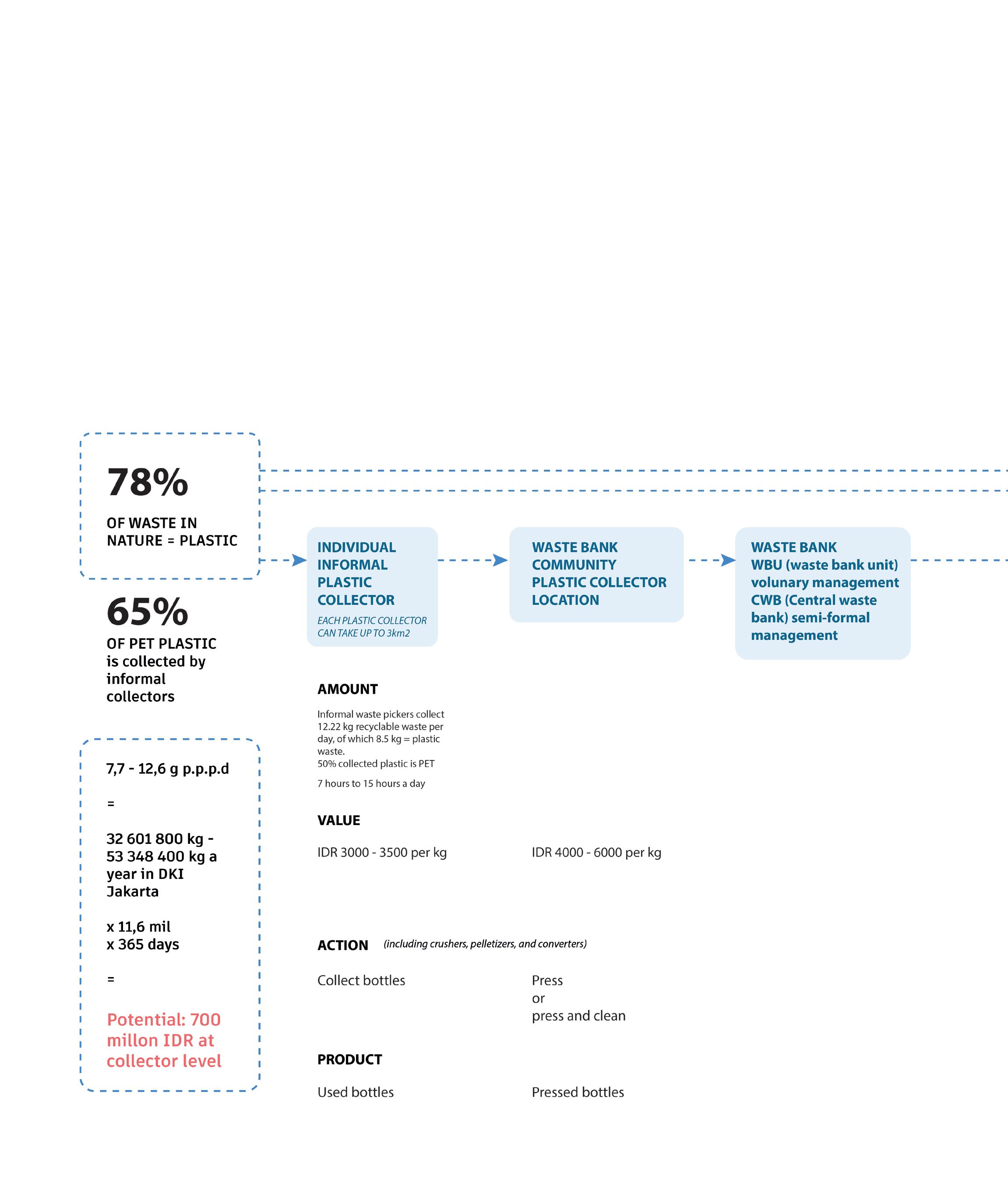

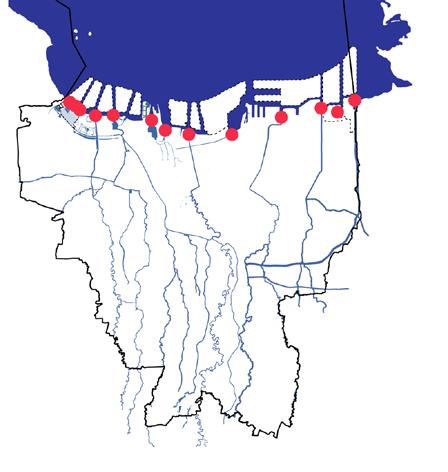

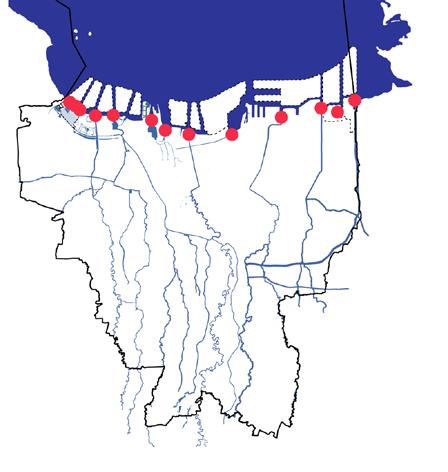

Right now only ‘valuable’ waste is collected to recycle. It is collected by individual waste pickers. Waste pickers, or ‘Permulung’ are the first step in a large recycling process. They have an action radius of about 3km, they search daily. Waste pickers are most likely to live in slums and flood zones. A map of the distribution of what are considered slums shows that waste pickers are spread across Jakarta.

During our time in Jakarta, my relative Holy took us to visit Mr. Yosef, a former household assistant of a family member who sadly passed away recently. Mr. Yosef lives in a tiny house of about 8 to 12 m². He shares it with his wife and daughter, located on a cul-de-sac alleyway between houses, adjacent to a pondok. Both he and his wife are ‘pemulung’ and earn a living by collecting PET plastic.

Circular initiatives need space and empowerment to grow.

The Ministry of Environment and Forestry (KLHK) introduced a Waste Bank system called Bank Sampah in Indonesia. The Waste Bank actively involves citizens in waste separation at the source and engages them in the recovery of materials for remanufacturing or recycling.

Under this system, community members (customers) separate their waste at source and deposit any recyclable materials at the waste banks in the community. Transactions are recorded in a bank note held by customers or in lists kept by the respective waste banks.

The waste banks sell the collected materials to intermediate recycling collectors or a central waste bank, when sufficient volume has accumulated for transportation. The customers are paid after they pay a contribution of 15% for operational costs.

According to KLHK, about 11,556 waste banks have been set up in 34 provinces covering 336 regencies or cities in Indonesia. These community waste banks have contributed to reducing the amount of waste sent to landfills by 2.7% at the national level

Although a great initiative, Waste Bank organisations struggle to keep them open. They would benefit from various spatial and organisational adaptations. The recycling process could benefit

3. Increase in the variety of sorting and processing waste

5. Collaboration with NGOs, waste initiatives and schools to

7. Digital platform

REDUCE, REUSE, RECYCLE ..AND REWARD!

With the right impulse in social branding of waste management to reduce waste, teaching people how to do the 3R’s (reduce, reuse and recycle) they can have the skill to manage their waste well. The next step is to investigate the opportunity to add a 4th R: Repay/regain/remunerate/reward to add an extra incentive and to create economic opportunity for the urban poor.

The lessons learnt are:

- A system at the community or decentralised level that separates waste is necessary.

- People can be motivated to change their lifestyles towards better resource management through the practice of sharing, reuse and repairing. REWARD!

- The Waste Bank shows potential.

Source: https://ccet.jp/projects/waste-bank

Source: City Without Slum, 2017; Statistics Indonesia, 2017

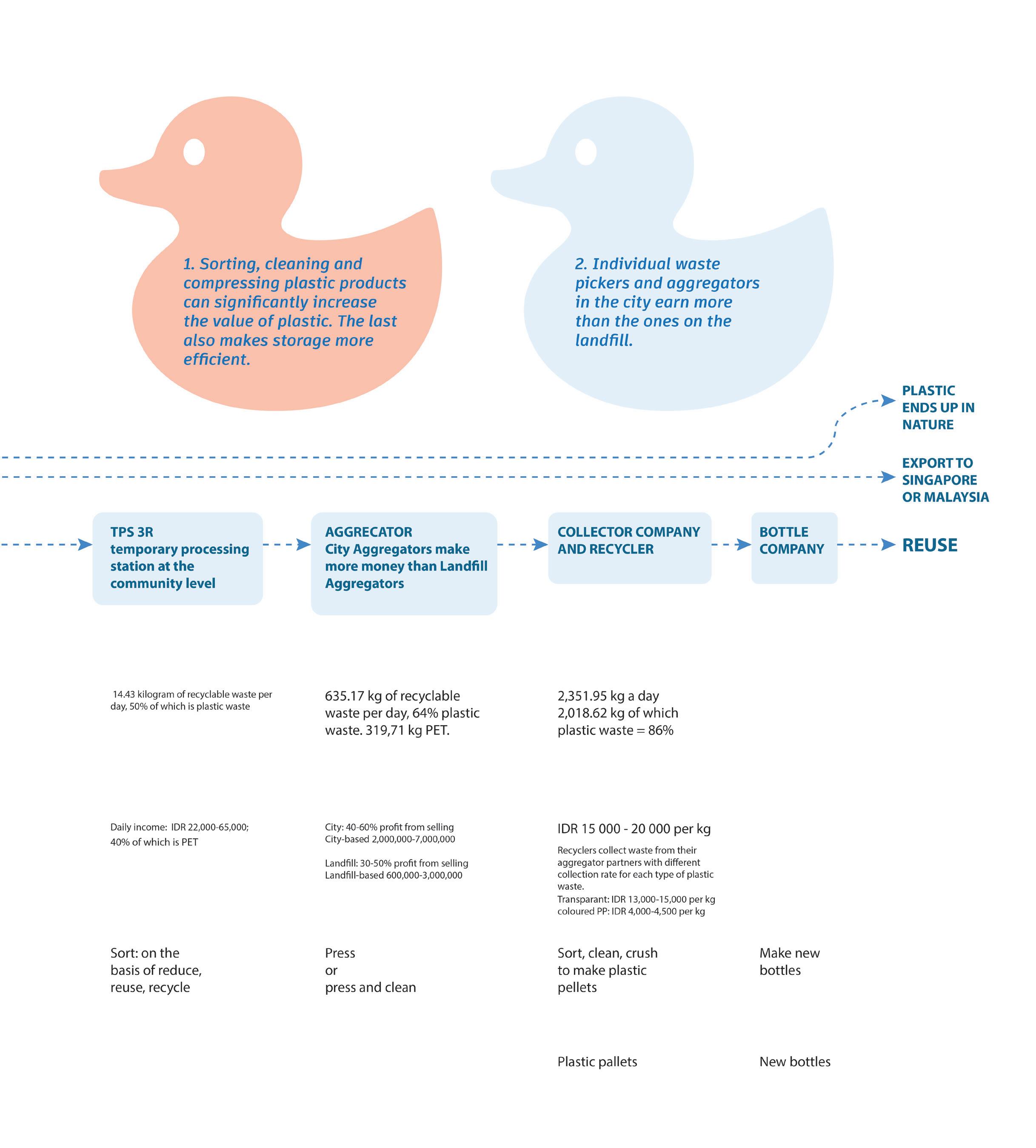

EVERY STEP IN THE PROCESS ADDS VALUE TO THE WASTE PRODUCT.

Waste pickers and waste banks are at the start of the recycling value chain. Which means individual waste pickers profit the least but contribute the most of their individual time.

The lesson learnt:

- If waste pickers could process their waste collectively, they would make more money and would have more free time to spend on other aspects of life. The question is: How can we scale this up even more, so recycling will generate more income over time?

Source: Advancing The Potential Of Pet And Pp-Based Beverage Packaging To Support Circular Economy, D. Trisyanti, 2022/12, Journal of Environmental Science and Sustainable Development, p.p. 381-395

Source:

70% age 15-64 7%age1-14 23%age65+

AVERAGE AGE = 28 YEARS OLD

MANY PEOPLE = GREAT POTENTIAL

JAKARTA IS A VERY YOUNG CITY

Jakarta is so young that the average age is about 28 years old (2015), which is under the estimated national average of 30,4 years old.

Generally a potential labour force consists of people between 15 years and 65 years of age. The potential labour force in Jakarta is 4,33 million people.

The unemployment rate is 6,03%. Among age groups, the youth unemployment rate (ages 15-24) remained the highest at 17,32 %. nearly 66% of Jakarta’s workforce works in the informal sector.

LOST POTENTIAL: SECONDARY SCHOOL DROP-OUTS

Right now 98,44% of children finish primary education, only 60,81% finish secondary education and a small 6,52% of people pursue higher education. An alternative route of learning is stimulated in policy.

FOCUS ON VOCATIONAL EDUCATION

Jakarta has been prioritizing the expansion of vocational schools (SMK) to equip youth with technical and practical skills that are in high demand in industries like manufacturing, IT, hospitality, and automotive sectors. This focus aims to reduce youth unemployment by providing alternatives to university education and meeting the labour market’s needs.

TACKLE EXTREME POVERTY

Nationwide Indonesia has set itself the goal since January 2025 to tackle the extreme poverty (of 3.1 million people). Of Jakarta’s inhabitants, 4,14% lives in poverty. This amounts to 480 240 inhabitants.

MANY PEOPLE LIVE IN KAMPUNGS

Of the total amount of inhabitants living in Jakarta, 60% live in kampungs or informal settlements, This means the labour force of kampungs or living in informal settlements is between 2,08 and 2,6 million people. Of which between 457000 and 629000 people squat illegally along riverbanks. There is great potential in this group of people, as they fulfil an important role in Jakarta’s urban metabolism.

1000 INFORMAL WAYS TO EARN A LIVING

I’ve seen firsthand and read about the many ways impoverished inhabitants fill up voids left by the government. They are quite resourceful and entrepreneurial. A few examples are given on pages 78 and 79. Community organisations and democratic Kampung communities seem te be able to scale up their impact on their community.

The resourcefulness of Indonesian people, the high unemployment rate, and the potential of high school dropouts— combined with the fact that this applies to a large portion of the population— lead me to believe that Jakarta’s people hold great untapped potential.

This is especially true in close-knit communities living in kampungs and informal settlements, as they also have the ability to organize themselves. The current, relatively balanced distribution of kampung structures that include ‘slums’ in Jakarta creates opportunities on a province-wide scale.

The heat in Jakarta can be paralyzing due to the very humid sea air and the scarcity of porous spaces or heat sinks in urban environments. The difference between air-conditioned buildings and the outside environment is stark. Creating comfortable environmental conditions will have a direct impact on people’s productivity and well-being.

Source: www.cityfacts.com/jakarta-raya/population 2025/01/12 11:32

Source: UN-Habitat (2003) Global Report on Human Settlements 2003, The Challenge of Slums, Earthscan, London; Part IV: ‘Summary of City Case Studies’, pp195-228.

Source: https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/jakarta-population 20240220 07:16

Source: https://www.city-facts.com/jakarta-raya/population

Source: https://jakartaglobe.id/business/bps-unemployment-rate-drop-signals-recovery-male-earn-28-more-than-females

Source: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1423886/indonesia-jakarta-population-by-gender-and-age/025/04/05

Resourcefulness leads to many odd-jobs People in Jakarta tend to make a living out of tasks that the government isn’t arranging.

Macet-director (trafficjam-director): They direct traffic during the many traffic jams. They are payed by the drivers they let pass.

Road-Jockeys: They get payed to sit on the backseat as car-filler. This is because the government instated a ‘carpool-rule’ to reduce macet.

BantarAyam:

On top of the landfill a salesman thought it was a good idea to start selling roasted chicken to waste pickers. Waste pickers generally don’t leave the landfill during the day while they’re working. So the salesman was right.

Trash ‘tipper’:

They get paid to turn a blind eye to illegal waste tipping.

Banjir director:

They have a walkytalky that pick-up radio messages from flood managers. They know when a flood wil occur because they listened in.

Community group savings:

Communities can have a joint savingsystem. As a group they save for a goal of one inhabitant. This way the goal will be met quite soon.

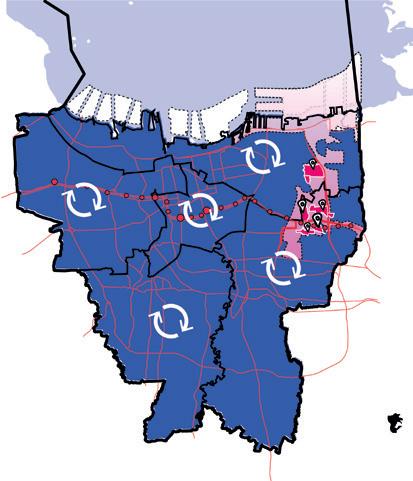

During my visit I came across two main urban entities that divide Jakarta in roughly two types of urban settlements: The Kota and the Kampung.

Both types vary in shape and size and are scattered throughout Jakarta, but their role in urban dynamics is quite distinct. These entities are interconnected, they serve different purposes and depend on each other.

The Kota represents the modern, commercial, and business areas of the city. They are the city’s economic and political centres and are often developed on a large scale by public-privatepartnerships. These areas have better infrastructure, public services, and economic opportunities than other areas in the city.

THE KAMPUNG

Kampungs are typically dense low-rise neighbourhoods. Kampungs are naturally diverse when it comes to mixing housing for different income classes in one neighbourhood. They offer space for (mostly landed) formal housing and informal housing. Kampungs can house squatter communities, but also contain housing for middle class inhabitants. Development of kampungs is mostly plot oriented.

THE URBAN DYNAMICS OF THE KOTA AND THE KAMPUNG Kampungs, in general, are an important part of metropolitan cities. The Kota leads in some aspects, such as the economy and politics, while Kampungs lead in others, including social relationships, democratic culture, and community cohesion. Both historically and today, there is a mutually beneficial relationship between the Kota and the Kampung. Kampung residents need work, but kampungs lack provisions for employment, whereas the Kota has them. Conversely, the Kota needs a workforce, which the Kampung can provide. This relationship and mutual dependence remain unchanged. However, the spatial balance has shifted over the past few decades. A decrease in Kampung living environments not only affects the neighbourhoods themselves but also impacts Jakarta’s entire urban metabolism.

- Governor Ali Sadikin

He served as Jakarta’s governor from 1966 to 1977 and is renowned for his pragmatic and compassionate approach to urban development, particularly concerning the city’s kampungs.

KAMPUNGS IN JAKARTA

Kampungs in Jakarta are inner-city village structures. They are dense, low-rise residential neighbourhoods with narrow streets and often lack green or porous areas. Homes can include a small economic space within or in front of them.

KAMPUNGS ARE STIGMATIZED

There is something paradoxical about Kampungs. On the one hand Kampung structures are stigmatized as ‘disordered’, or ‘slum-like’ environments, while on the other hand Kampungs are seen as important structures in Indonesian society. This reflects a broader social bias that associates urban modernity with formal planning and disregards the social and spatial richness of these communities.

From what I’ve read on this topic, due to the colonial legacy, administrations treat Kampungs as unplanned and unhealthy. After independence in 1947, the dense, informal, low-rise neighbourhoods were seen as incompatible with ‘modern’ Jakarta. An example of how the government has not shed its ‘colonial-gaze’.

Planners and politicians treat kampungs as obstacles, especially regarding flood protection along riversides and coastal area. In

the media, Kampungs are frequently depicted as sites of poverty, chaos, and risk, reinforcing their stigma. Meanwhile, NGOs, activists, and urban scholars view them as urban villages full of resourcefulness, creativity, and democracy.

THE BEAUTY OF KAMPUNGS: “GOTONG ROYONG”

Kampungs are described as ‘the place where people learn to be Indonesian.’ This is explained through the comprehensive term Gotong Royong, which embodies the core values of Indonesian culture. It resembles the Dutch naboarschap or English neighbourliness, but goes beyond them.

Gotong Royong is a cornerstone of Indonesian social values. It refers to mutual cooperation, communal work, and collective responsibility, and can be seen as a form of social solidarity. Community members come together to help each other, often without expecting financial compensation.

The key aspects of Gotong Royong include mutual assistance, community spirit, and volunteer work to benefit the community in the long term. This can take shape in activities such as building a house, cleaning the environment, or providing disaster relief. Gotong Royong emphasizes working together for the common

good, putting individual interests aside for the benefit of the wider community. This is why Kampungs are considered ‘the place where people learn what it is to be Indonesian.’

GOTONG ROYONG IN NEIGHBOURHOOD DEMOCRACY

Neighbourhood associations (Rukun Tetangga and Rukun Warga) allow residents to cooperate in maintaining security, cleanliness, and other local issues. Volunteer activities include environmental cleanups and supporting local schools.

THE OPPORTUNITY IN SELF-ORGANISATION (MUTUAL ASSISTANCE)

Kampungs are places where community engagement and social connection are part of everyday life. The dynamics within Kampungs rely on collective reliance among all parties involved. This reliance makes the community resilient in times of trouble and enables the community to create opportunities by working together.

FLOOD/CRISIS MANAGEMENT (DISASTER RELIEF)

One form of cooperation is the civil crisis management system that riverside communities put in place to manage floods. In Jakarta, most floods are considered routine. When central crisis control is lacking, the neighbourhood organizes flood management themselves. Typically, one or more community members receive information from those controlling the floodgates and inform the residents about the upcoming flood and its severity.

KAMPUNG SAVINGS (MUTUAL ASSISTANCE)

Within Kampungs, there are various forms of organisation. In some Kampungs, neighbourhood groups operate a joint saving system. Each member contributes the same amount of rupiah toward the goal of one member. When enough rupiah is collected to reach the goal, the group sets the next target for a different member.

Source: Rivers as municipal infrastructure: Demand for environmental services in informal settlements along an Indonesian river, Vollmer, D., Grêt-Regamey, A., EHT Zurich, Singapore, 2023/10/02

Source: van Voorst, R., De beste plek ter wereld, Uitgeverij Brandt, Amsterdam 2016

Source: Jakarta’s Kampung Dwellers as Equity Partners in Slum Alleviation Planning, F. Winharsih, WUR, Wageningen, 2021/02/25

The empty marketstreet

This place was very lively earlier in the morning. This is a bit later in the day. The rhythm of life is completely different from what I’m used to. Early mornings are the busiest times.

Public space is full of fruit

There are many nooks and crannies in Jakarta that have fruittrees or other types of urban agriculture.

How narrow can streets be?

This is the street in Jakarta West, where my dad’s aunt used to live. The neighbourhood recently recieved an open drainage system for rain. Open canals run on both sides of the pedestrian path. They are about 50 to 75cm deep and smell like fresh laundry.

People generally love plants It is quite noticable that everywhere you go in Jakarta people seem to love plants. The many pots in front of homes remind me of some parts of Amsterdam.

Small homeshopstreet in Jakarta West

This street leads directly from a metro line to the main commercial road and market area in the neighbourhood. Inhabitants benefit from this direct route, by adding a small shop to their home.

for children

Children have little space to move around, Playgrounds, day-cares and schools are often surrounded by fences. I noticed Kampungs miss different scales in public space , that can add more texture to one’s day.

WASTE PICKING IS A REAL JOB

This is where Mr. Yosef lives. I mentioned him on page 69. His indoor living space is tiny, but life happens mostly outside. Laundry hangs in the narrow streets and the pondok around the corner provides an area for neighbours to meet outside their homes. Life in Kampungs is a lot less private than in the Netherlands.

RAIN DRAINS ARE OFTEN PAVED OVER

The street probably wasn’t designed or built to be closed off like this, but I can imagine this is why I’ve heard that many drains in the city clog over time. People pave over the storm drains, and the lack of access makes them impossible to maintain.

This street connects to a busy road. But the traffic isn’t noticable from inside the kampung. I love how noise pollution from traffic is barely able to reach into the kampung living environment.

KAMPUNG SETTLEMENTS ARE GREAT PLACES TO WANDER AROUND IN

On our way to visit Mr. Yosef to talk about his job as a waste picker, we walked through the narrow streets of his neighborhood. These streets are full of surprises, and I can’t help but wonder whether streets like this would suit the Dutch context. In form, they probably resemble medieval city structures most closely.

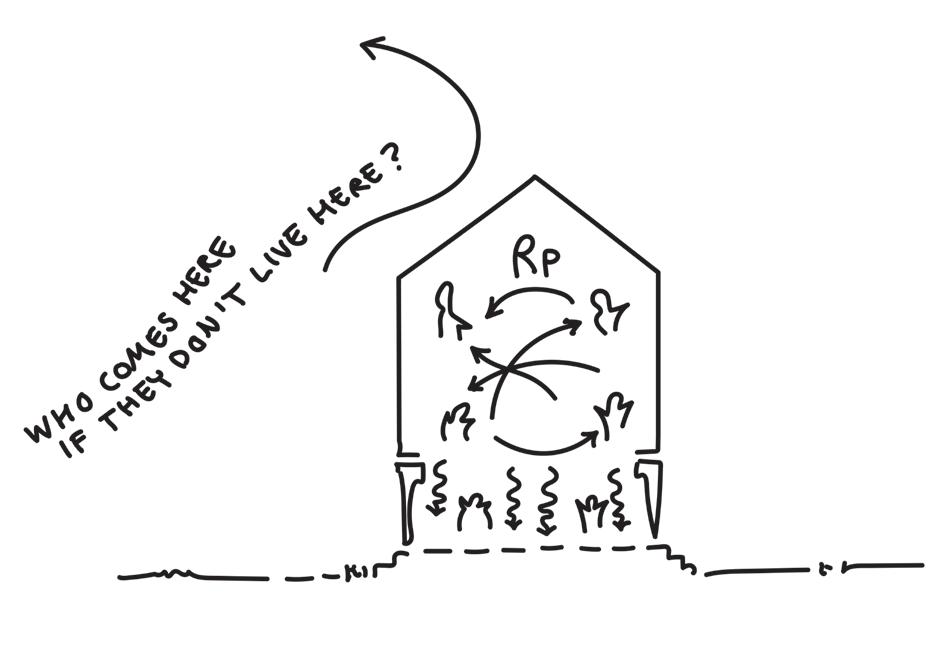

JAKARTA HAS GREAT COMMUNITY ORGANISATIONS THAT CAN INNOVATE!

Jakarta has ‘RPTRA’ community organisations, that empower people and experiment with ways to uplift impoverished community members. They supervise RPTRA parks, that were built to create more public space in Jakarta. RPTRA organisations create a great base for innovation. Their ability to organise can even lead to profitable community businesses. This means there is opportunity in the existing power to self-organise, these organisations just need more space.

The ratio of open spaces in Jakarta is only about 9-10% of the total area, which is far below the Indonesia’s minimum requirements of at least 30%. In 2015 the Jakarta City Provincial Government published a policy on child-friendly integrated public spaces (RPTRA) to guide the development of small public urban green spaces.

RPTRA parks are built in densely populated areas, with an aim to help people, particularly women and children, minimize the stressful living conditions of living in such areas.

Unlike the common neighbourhood parks that exist in Jakarta, the goal of RPTRA is not to only provide places for recreation, but has larger objectives to provide accessible places that integrate various public functions and activities, like playing and learning for children, social interaction for citizens, family consultations and information centres, evacuation areas, and economic activity spaces managed by Family Welfare Movement (PKK) groups. By 2017 the government already developed about 184 RPTRA in Jakarta. The rapid development was made possible by the funds from the Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) allocation of private sector companies and the City Government.

The criteria for RPTRA are similar to the criteria of “Taman RT” and “Taman RW set by the Ministry of Public Service No 05/ PRT/M/2008, that it has to be: a small urban public green space sized about 500-5000m2, located within a minimum radius of 300m to a maximum radius of 1000m of a locality (broadly visited destination), and comprise at least 70%-80% vegetation. This definition is similar to the definition of small public urban green spaces (SPUGS) in Copenhagen and the definition of small public urban open spaces (SPUOS) in Hong Kong.

KALI BARU HUB, North Jakarta: Scale up recycling initiatives to recycling community!

Kalibaru HUB is a great example of how community organisations can create the path to a regenerative future. Kali Baru HUB is a kampung neighbourhood in Jakarta North. It has started to recycle shell waste into marketable products. The community collaborates with educational institutions and create awareness about the value of shells for water purification.

RPTRA DWIJAYA, South Jakarta.

This RPTRA in Jakarta South is very active. It has great innovative experiments to help impoverished community members like using hydroponics for urban agriculture. It partakes in various initiatives, like the 1000 tree planting movement in 2023.

The RPTRA is quite confined within its urban context and the Lurah (neighbourhood chief) explained that he would like to expand the hydroponic system to create more impact. He pointed to adjacent informal housing, saying this is where he would like to expand to.

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384402620_Exploring_the_inclusivity_of_Jakarta%27s_child-friendly_integrated_public_spaces_RPTRA_through_qualitative_ analysis_of_google_map_reviews (2024/11/05 12:01)

Source: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Eka-Permanasari/publication/346090910_Implementation_of_Participatory_Design_Approach_in_Jakarta_Community_Center_RPTRA/ links/632778c40a708521500373ee/Implementation-of-Participatory-Design-Approach-in-Jakarta-Community-Center-RPTRA.pdf (2024/12/18 20:22)

Source: https://uclg-aspac.org/kalibaru-hub-project-green-light-to-take-further-actions-to-support-community/ (2024/08/31 21:54)

Jakarta’s fast pace development focuses on middle and upper income level households, flood mitigation and infrastructure. The main developments in and around the province are expanding inequality/segregate society. An overview is given below to illustrate this research conclusion.

The most recent idea is to try to move the capital to Kalimantan. The city will be called Nusantara, which translated to “other islands”. This is not the first time, it was also planned in the fifties, nineties and around 2010. In one of these plans infrastructure was laid out, but the capital never moved. This time they are building the capital in east Kalimantan.

The new capital is promoted as a way to solve all of Jakarta’s problems. But this doesn’t actually solve the problem of pollution. It moves the problem to a different place and without changes made in the management of water and waste, the city will gradually attract the same problems as Jakarta.

The construction of the capital is progressing, but it hasn’t had the amount of foreign investors the government aimed to attract.

Islands are under construction on the coastline. Their programming is directed to attract the upper-middle income households and upper income households. This development is called Pantai Indah Kapok, PIK for short. A new business district, leisure district and both landed and high-rise apartment buildings are constructed. An elevated toll road links PIK directly to Jakarta’s main infrastructure and is connected to the airport. Another plan that keeps reappearing is the construction of a ‘giant sea wall’ to keep out the rising sea water. These development put pressure on the livelihood of fishing communities on the coastline. Fishing communities are also under threat by the degradation of the coastal ecosystem, due to pollution.

Jakarta works to prevent disastrous flooding. Jakarta is implementing different types of infrastructure to manage water levels to reduce flooding. Around 1910-1920 two big flood canals were constructed to mitigate flooding. Many strategies followed afterwards: wells, normalisation, naturalisation, islands, a dam. These strategies are mainly focused on water defence. They do not usually consider social justice or include biodiversity. This is also the case in the large scale programme to normalise riverbanks in Jakarta.

A small scale wasteful behaviour I encountered is the construction of McMansions It seems like higher income level households prefer newbuilds over older houses. This is noticeable in some upper income level neighbourhoods we visited. Houses are fully stripped and adapted to the new owner’s wishes.

Source: https://partners.wsj.com/bkpm/bridge-to-the-future/nusantara-indonesias-new-capital-city-spearheads-quest-for-sustainable-and-inclusive-development/ (23/09/01 19:05)

Source: https://setkab.go.id/en/govt-resumes-river-normalization-to-tackle-jakarta-floods/ (2023/10/15 19:11)

Source: https://www.kompas.id/artikel/en-agar-efektief-normalisasi-ciliwung-difokuskan-ke-sejumlah-segmen – Kompas (2025/05/19 15:02)

Source: https://www.futurarc.com/project/jakarta-jaya-the-green-manhattan/ 2023-09-17 12:29

GATED SATELLITE COMMUNITIES

Guarded satellite neighbourhoods are built on the edges of Jakarta and in adjacent provinces, like Gading Serpong in South Tangerang.

Much like is happening in other megacities like São Paolo, In Jakarta gated communities with mainly a large supply of landed houses are built for specific income levels. They are both being built in vacant green areas within the province, and larger scale projects are built in the metropolitan region around DKI Jakarta in areas like Tangerang and Tangerang Selatan in Bantan. Gated communities have several negative effects on society and the environment, some of which are mentioned below.

ENVIRONMENTAL EFFECTS

This type of urban expansion reduces surface area for nature. By reducing permeable surface area, it elevates the chance and the severity of flood events.

This type of sprawl also stimulates individual car use instead of the more environmentally friendly public transportation that is in development within the province of Jakarta. To accommodate this, extensive road infrastructure —often four to five lanes wide— are constructed.

ECONOMIC SEGREGATION

Gated communities contribute to economic segregation by creating a boundary and distance between different income groups. This is particularly concerning, as research suggests that reducing physical distance between income groups can enhance the economy through increased upward socioeconomic mobility and stronger social cohesion in communities (Chetty & Hendren, 2018). Moreover, economic inequality plays a significant role in shaping the future prospects of younger generations and their potential for socioeconomic advancement (Kearney & Levine, 2016). In the context of Jakarta, such inequality is largely driven by patterns of economic segregation. The bottom line is: neighbourhoods affect the quality of intergenerational mobility in the future.

DISPUTABLE SPATIAL QUALITY

It would have been somewhat comforting if these developments created exceptional living quality. Sadly this doesn’t seem the case. In some gated communities the quality of the living environment is disputable. An example is housing in Gading Serpong in Tangerang Selatan. At first glance houses are quite nice. But I noticed that skylights in these houses are made out of plexiglass. I’ve experienced heavy rain in Jakarta before, but the plexiglass skylight turns space into a giant drum during a downpour, making it difficult to hold a conversation at the kitchen table.

Source: https://academic.oup.com/qje/article-abstract/133/3/1107/4850660, Chetty R., Henderson N., 2018 (2023/12/11 21:01)

Source: https://scholar.undip.ac.id/en/publications/measuring-the-scale-of-sustainability-of-new-town-development-bas (2023/10/15 20:33)

INHABITANTS ARE SEPARATED FROM THEIR SOCIAL NETWORK

A HOME IS ALSO A LIVELYHOOD. DISPLACEMENT IS ECONOMICALLY DEBILITATING