Arctic Yearbook 2025

Heininen, L., J. Barnes & H. Exner-Pirot, (eds.). (2025). Arctic Yearbook 2025 – War and Peace in the Arctic. Akureyri, Iceland: Arctic Portal. Available from https://arcticyearbook.com

ISSN 2298–2418

This is an open access volume distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY NC-4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial.

Editor

Lassi Heininen| lassi.heininen@ulapland.fi

Managing Editors

Justin Barnes | jbarnes@balsillieschool.ca

Heather Exner-Pirot | exnerpirot@gmail.com

Communications Manager

Tiia Manninen | tiiamanninenfin@gmail.com

Editorial Board

Dr. Daria Burnasheva (Senior Lecturer at Arctic State Institute of Culture and Arts, Sakha Republic)

Dr. Miya Christensen (Professor at University of Stockholm, Sweden)

Halldór Johannsson (Executive Director, Arctic Portal, Iceland)

Dr. Alexander Pelyasov (Russian Academy of Sciences; Director of the Center of Northern and Arctic Economics, Russia)

Dr. Ólafur Ragnar Grímsson (Former President of the Republic of Iceland, Chair of the Arctic Circle Assembly)

James Ross, (Gwich’in leader, Northwest Territories, Canada)

About Arctic Yearbook

The Arctic Yearbook is the outcome of the Northern Research Forum (NRF) and UArctic joint Thematic Network (TN) on Geopolitics and Security. The TN also organizes the annual Calotte Academy.

The Arctic Yearbook seeks to be the preeminent repository of critical analysis on the Arctic region, with a mandate to inform observers about the state of Arctic politics, governance and security. It is an international and interdisciplinary peer-reviewed publication, published online at [https://arcticyearbook.com] to ensure wide distribution and accessibility to a variety of stakeholders and observers

The authors of all articles, briefing notes and commentaries have worked independently. Publication does not imply endorsement by the Arctic Yearbook’s editorial team or its directors.

Cover artwork was created using Adobe Firefly with AI-assisted generation and edited by Tiia Manninen. No real persons, events, or military assets are depicted. The inclusion of this image reflects the transparent and responsible use of AI in visual publishing. Prompt and editing notes are documented and available upon request.

Arctic Yearbook material is obtained through a combination of invited contributions and an open call for papers. For more information on contributing to the Arctic Yearbook, or participating in the TN on Geopolitics and Security, contact the Editor, Lassi Heininen.

Acknowledgments

The Arctic Yearbook would like to acknowledge the Arctic Portal [https://arcticportal.org] for their generous technical and design support, especially Ævar Karl Karlsson. We would also like to thank our colleagues who provided peer review for the scholarly articles in this volume

Table of Contents

Introduction

War and Peace in the Arctic……………………………………………………………………1

Lassi Heininen, Heather Exner-Pirot & Justin Barnes

Commentary

Review of Tolstoy’s War and Peace 8

Hasan Akintug

I. Projecting Power in the Arctic

Kalaallit Nunaat as a Foreign and Security Policy Actor 12

Sara Olsvig & Ulrik Pram Gad

China, Russia, and the U.S. in the Bering Sea: Military Exercises and Great Power Politics……33

Erdem Lamazhapov & Andreas Østhagen

Balancing Alliance Commitments and Economic Dependence: Faroese-Russian Relations in an Era of Great Power Rivalry 53 Heini í Skorini & Tór Marni Weihe

Reassessing Arctic Security: Canada’s Policy Response to Geopolitical Shifts and Emerging Threats ...73

Karen Everett & Katharina Koch

The Evolution of Russia’s Arctic Strategy after the War in Ukraine 96 Angela Borozna

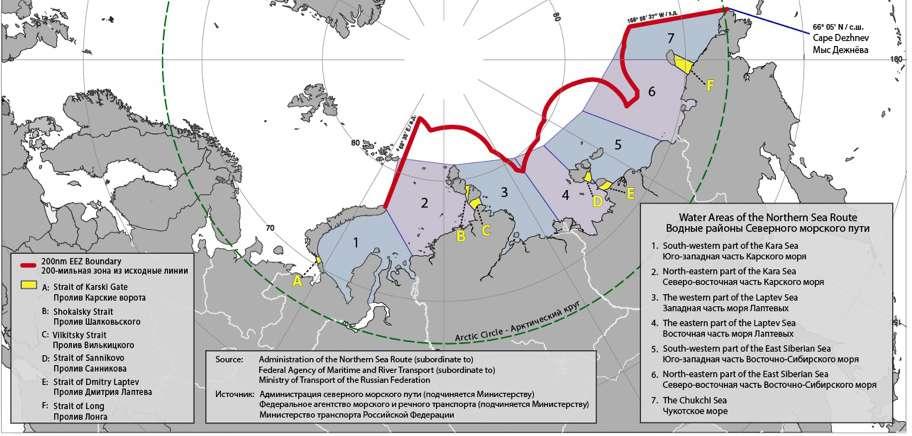

Russian Ambitions to Control Freedom of Navigation and Arctic Access: Refined Data Challenging Moscow’s Northern Sea Route Claims ..122

Troy Bouffard, Gennaro D’Angelo, Gabrielle F. Gundry, Travis R. Pitts, Stephen F. Price, & Andrew F. Roberts

Briefing Notes

Canada’s Arctic Foreign Policy: Somethings Old, Somethings New………………………….143 P. Whitney Lackenbauer

Impacts of Geopolitical Tensions: What Russia’s War in Ukraine Means for Cooperation and Scientific Programs in the Arctic 157

Margaret Williams & Loann Marquant

Feminist Peace for the Arctic: A Briefing on the Fourth Eurasian Women’s Forum, the BRICS Women’s Meeting, and “Peace, Nature and Cooperation in the Baltic and Arctic Seas” Conference in St. Petersburg, Russia in September 2024 164

Tamara Lorincz

II. NATO and Collective Defence in the Arctic

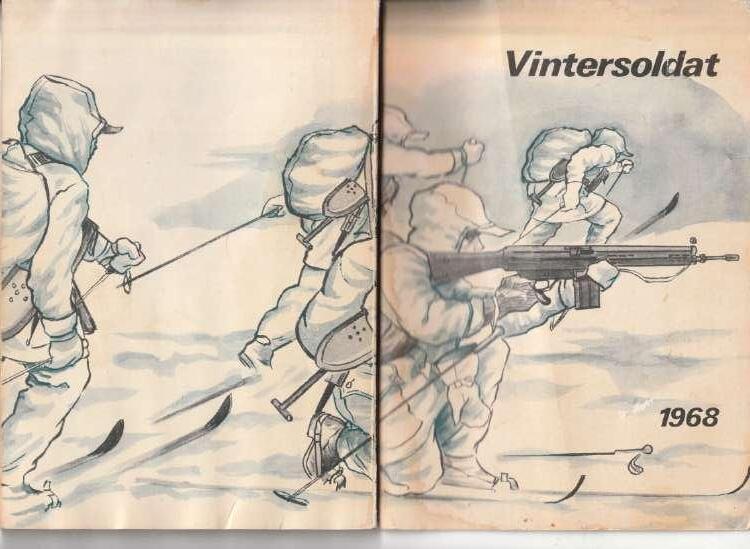

Changes in Sweden’s Security Policy Messaging in the Country’s Military and Civil Defense Publications During the Cold War Compared to Those After NATO Membership………….171

Robert Wheelersburg

NATO’s Arctic Narrative After 2022: Conferences as Promoters of Security or Drivers of Destabilization?……………………………………………………………………………....191

Marco Dordoni

Briefing Notes

NATO and the Arctic in the 2020s…………………………………………………………..217

Gabriella Gricius & Nicholas Glesby

The EU Mutual Defence Clause and Greenland: What Happens if Denmark asks for Help According to Article 42 (7) TEU?……………………………………………………………229

Stefan Brocza

The New Northern Flank in an Integrated Deterrence Concept……………………………...233

Paul Dickson

III. Resource Development and Geopolitics

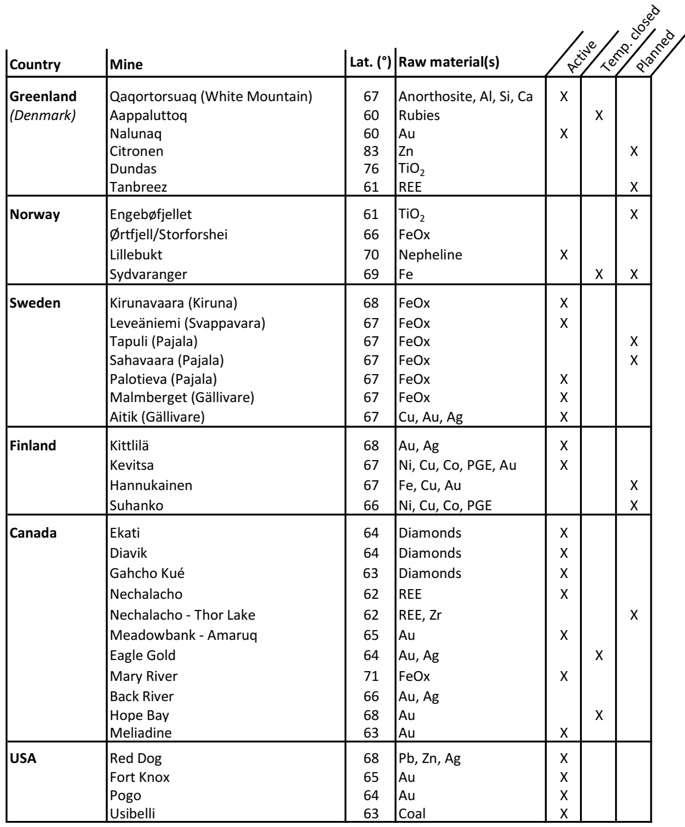

Responsible Mining in The Arctic: Management, Monitoring and Mitigation of Dust Emissions 240

Christian Juncher Jørgensen, Christian Zdanowich, Pavla Dagsson-Waldhauserova, Alexander Baklanov, Tuija Mononen, Yu Jia, Christian Frigaard Rasmussen, Hilkka Timonen, James King, Patrick L. Hayes, Christian Maurice and Outi Meinander

Decolonization in Greenland and Nunavut and Resource Exploitation for a Decarbonized World: What does an Arctic Century Mean?

Anna Soer

257

Energy and Critical Minerals in the Arctic: Can the US-Russia Rivalry Continue through Cooperation?………………………………………………………………………………...284

Tiziana Melchiorre

IV. Human and Environmental Security

The Implications of Climate Change on Community Ontological Security in the Arctic: A Review……………………………………………………………………………………….296

Michaela Coote & Yulia Zaika

Environmental Restorative Justice and the Green Transition: Examining Intergenerational Equity for Sámi Rights under the Norwegian Constitution 310

Sara Fusco

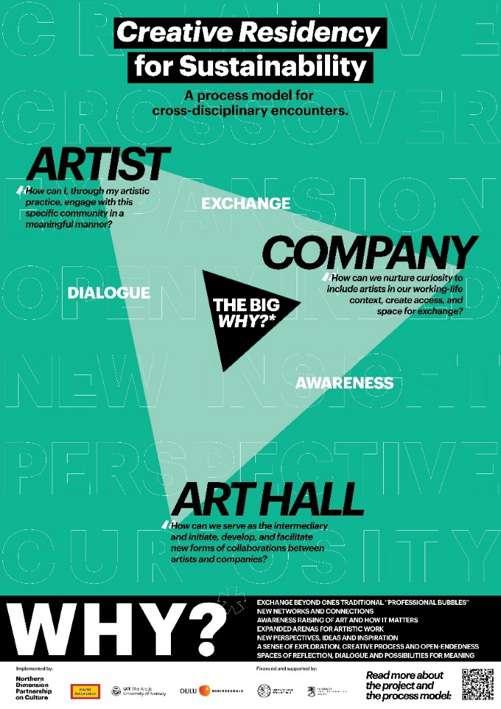

Art Intermediaries as Catalysts for Added Exchange and Sustainability in the Arctic………....332

Krista Petäjäjärvi & Maria Huhmarniemi

Negotiating Ethics and Methods: Knowledge Co-Production in the Russian Arctic in Uncertain Times 357

Karolina Sikora

Briefing Notes

Recent Canadian Northern Indigenous Peoples’ Sovereignty, Security, and Defence Strategies……………………………………………………………………………………..370

P. Whitney Lackenbauer, Zachary Zimmermann & Samuel Pallaq Huyer

Health and Environmental Security in a Warming Arctic…………………………………….385

Douglas Causey & Eric Bortz

Symposium for Early Career Researchers Working with Indigenous Issues at Mid Sweden University, 26-27 August 2025 394

Ekaterina Zmyvalova

Shared Roads, Shared Realities: Insights from the Calotte Academy’s Journey 2025………….396

Tatiana Petrova

V. Emerging Voices

Introducing Emerging Voices…………………………………………………………………..400

Tiia Manninen

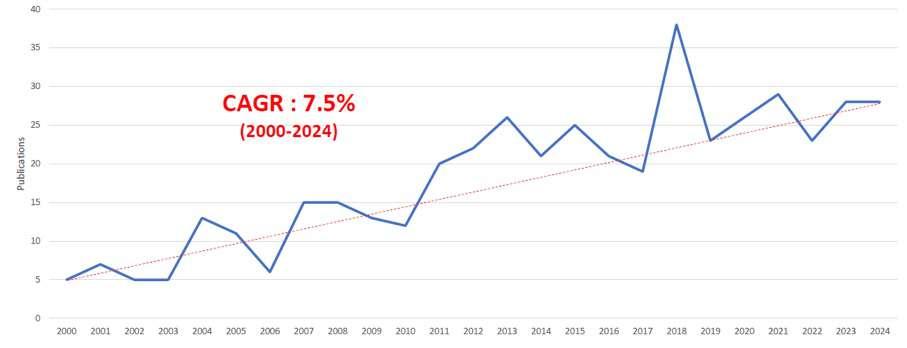

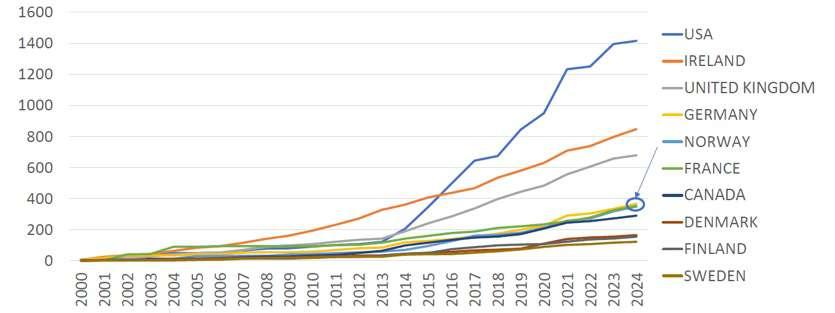

Ireland in Arctic Research: A Growing Scientific Presence…………………………………...402

Elena Kavanagh, Alina Kovalenko & Patrick Rigot-Muller

Getting Comfortable with Uncertainty: Lessons from an Arctic research station

Hanna Oosterveen

407

Compassion Resilience: A Perspective on War, Peace, and Community in the Arctic………...411

Charlene Miles

“It's Not Just About Economic Development”: Prioritising Climate-Vulnerable Regions in International Sustainable Development Policy The Arctic Case Study

Marta Koch

417

The (In)existence of a Portuguese Foreign Policy for the Arctic……………………………...425

Teresa Barros Cardoso

Economic and Political Arguments for NORAD Modernization in an Election Year 433

Vismay Buch

Introduction

War and Peace in the Arctic

Lassi Heininen, Heather Exner-Pirot,

and

Justin Barnes

In 1945, following the end of World War II, 49 sovereign nations declared their determination “to save succeeding generations from the scourge of war, which twice in our lifetime has brought untold sorrow to mankind”, by ratifying the United Nations Charter (see, Full text 2025; also Westing 1990). In 2025, despite the Charter and United Nations’ activities, whose ranks of member-states has swelled to 193, new generations have suffered from the scourge of wars and armed conflicts, as we are witnessing today in Gaza/Israel, Sudan, and Ukraine.

Whereas after the end of the Cold War international tensions and rivalries decreased for a while, armed conflicts and wars are “once again looking like an inescapable part of our future – though in changing forms that are confounding historians, military theorists and philosophers alike” (Mazower 2017), and in their wake, so are peace movements. “The recurrence of war is explained by the structure of the international system...War is normal” (Waltz 1989, 44).

In relations between different entities of a society, in relations between states, as well as in the entire international system, there is always cooperation and competition (indicating peace); sometimes tension, rivalry and conflicts (challenging peace); and every now and then armed conflicts and wars (breaking peace). If you consider international politics to be a spectrum, ‘peace’ would be on one end and ‘war’ on the other.

Competition, rivalry and conflict are interpreted as opposition, “contrasted with cooperation, the process by which social entities function in the service of one another”. While a society “can exist without violence and war... [but] cannot exist without competition and conflict”, it is questioned if conflict is naturally included alongside cooperation, and if it can ever be avoided as a disruptive manifestation of opposition. (Wright 1951, 321-323)

Yet it is worth asking if war is normal, or is this blunt explanation only determinism based on a structural, neorealist theory? As a matter of fact, isn’t peace more normal, or is that idealistic and wishful thinking?

Lassi Heininen, Heather Exner-Pirot, and Justin Barnes are the editors of the Arctic Yearbook

The Arctic Yearbook 2025, with the theme “War and Peace in the Arctic”, seeks to provide a collection of articles reflecting on this question, coming at a time when hot conflict, in the form of reflections of the war in Ukraine, has reached the Arctic region. The volume consists of 15 scholarly articles, 10 briefing notes and commentaries, and 6 emerging voices (as a new section), of timely and thoughtful analyses of Arctic military, security and diplomacy, as well as war and peace.

On war and peace

Discussions, discourses, debates on war and peace, as well as argumentation on behalf of war and peace, have been going on forever (see e.g. Akintug in this volume). Peace, even everlasting peace, is often stated by nations and leaders as an ultimate aim or objective to reach. Though still debated, modern anthropological research like for example, Douglas Fry criticizes the assumption that war is in our genes, and hence unavoidable based on human nature. Further, there are archaeological findings that warfare intensified when human beings transferred from hunting & gathering into agriculture (Virtanen 2007), based on anthropological studies on peaceful societies among Indigenous peoples from tropical rain forests to the Arctic tundra, such as the ‘Copper Eskimo’ in Northern Canada (Fabbro 1978); the implication is that war is not inherent, and it would be possible to prevent.

Sensible reasons and excuses for and against war, as well as various forms of knowledge about war, are constantly found. One of the most influential arguments is that “war as an instrument of national policy… is the continuation of politics by other means” by Carl von Clausewitz (Falk and Kim 1980, 7). Interestingly or strangely, in global politics of the 2020s, with the changing character of warfare and advanced studies on structural violence, the main idea of this early-1800s Prussian soldier and thinker - “that war is a form of social and political behavior” - is still vivid and quoted (e.g. Lamy et al. 2023, 256-258), and not widely debated.

Similarly accepted is the assumption that “The origins of hot war lie in cold wars, and the origins of cold wars are found in the anarchic ordering of the international arena… States continue to coexist in an anarchic order.” (Waltz 1989, 44, 48). By contrast, new realism argues that anarchy in the international system is much based on states, which also “recognize that the best path to peace is to accumulate more power than anyone else can make of it”, even if global hegemony is not possible (Lamy et al. 2023, 96-97). Indeed, “The chances of peace rise if states can achieve their most important ends without actively using force. War becomes less likely as the costs of war rise in relation to the possible gains.” (Waltz 1989, 48)

The roads to war are various, sometimes simple and sometimes complicated and complex, though seldom logical and never determinate. Furthermore, we seem to be experiencing less prevention of wars. An explanation for this trend is that war is a means to achieve power, emphasizing national interests. There are also other causes of war / armed conflicts, and behind them geographical and demographic factors followed by a claim of territory, for example to secure national security; economic factors followed by exploration of (natural) resources; political ones including a fight over values and ideologies; and the tendency of finding victims and / or those who are stated / manipulated to be guilty for something which is interpreted to be bad, even evil, for the society, as their religion, ideology, race or color is different.

Finally, there is misperception with many effects as a cause or road to war, including “inaccurate inferences, miscalculations of consequences, and misjudgments about how others will react to one’s policies” (Jervis 1989, 101), as well as mis- / disinformation spread and accelerated by the established and social media. Consequently, the binary nexus of war and peace deals with threat and enemy pictures – a psychological and sociological phenomenon – often based on misperceptions, and accelerated by religion, ideology or (established and social) media. These inferences could easily become interpreted as threats, i.e. requiring responses, and then real enemies, i.e. to defend from and fight against (e.g. Harle 1991).

There is always an alternative to war, starting with its absence. ‘Negative Peace’ provides the mainstream definition, focused on the absence of war but still structured in a society around military establishments and deterrence activities. ‘Positive Peace’, on the other hand, is centered around non-violent structures (in a society) and structured cooperation and confidence-building activities between nations as a precondition for peace.

Hence, it would be better to fulfill the comprehensive criteria of a ‘peaceful society’: “no wars fought on its territory… not involved in any [ones]… no international collective violence… or interpersonal physical [and] structural violence… [with] the capacity to undergo change peacefully; and … opportunity for idiosyncratic development” (Fabbro 1978).

If the above-mentioned are reasons enough for war, they might be prerequisites for peace. Models of / for peace, related with theories of international politics / relations, have been initiated, discussed and debated by thinkers and philosophers for centuries. These include Chinese Confucianism and Taoism; Socrates and Plato from the ancient Greek; European Dante and Pierre Dubois, as well as the Enlightenment philosophers Immanuel Kant and Jeremy Bentham; Gandhi in India, as well as Johan Galtung, a peace research theorist; and Nelson Mandela, a politician and practitioner who transferred civil war into peace. Not least, peace movements have been, though less so today, vocal and active, and peace research analytical.

In spite of the thesis of everlasting peace, that of democratic peace (based on liberal states), and other theories with their ultimate aims for peace, as well as the UN Charter aiming to end all wars, warfare and wars (or major / minor armed conflicts) proceed constantly. Consequently, people and the environment are suffering due to them, although historically less so in the Arctic region.

War and peace in the Arctic

To call the Arctic a “zone of peace”, as President Gorbachev (1987) did; or to describe the region as “peaceful, stable, prosperous, and cooperative” as the US National Strategy for the Arctic (T he White House 2022) does; or being ready to reaffirm “our commitment in maintaining peace, stability and cooperation in the Arctic”, as the eight Arctic states did in Arctic Council Ministerial in 2025 (Romssa – Tromsö Statement 2025), sound appealing in the world (in disorder, and with turbulence and ecological impacts) of 2025.

Nonetheless, these slogans / statements mean ‘negative peace’, ie. an absence of hot war; they imply neither ‘positive peace’, nor would they fulfill the criteria of a ‘peaceful society’.

This is in contrast to the Inuit Circumpolar Council’s Principles and Elements for Comprehensive Arctic Policy (ICC 1992, 25) explicitly includes a more holistic approach building and emphasizing relationships between human rights, peace and development (see, UN report on Relationship

between Disarmament and Development (1982), UN report on Common Security (1983)). It played an important foundation for further Arctic policies of ICC (e.g. Heininen et al. 2020, 169183).

The document states that “The Arctic policy should recognize that there is a profound relationship between human rights, peace, and development. None of these objectives are truly realizable in isolation from one another… In a global context, peace is much more than an absence of war. It is considered to entail a fair and democratic system of international relations, based on principles of mutual co-operation.”

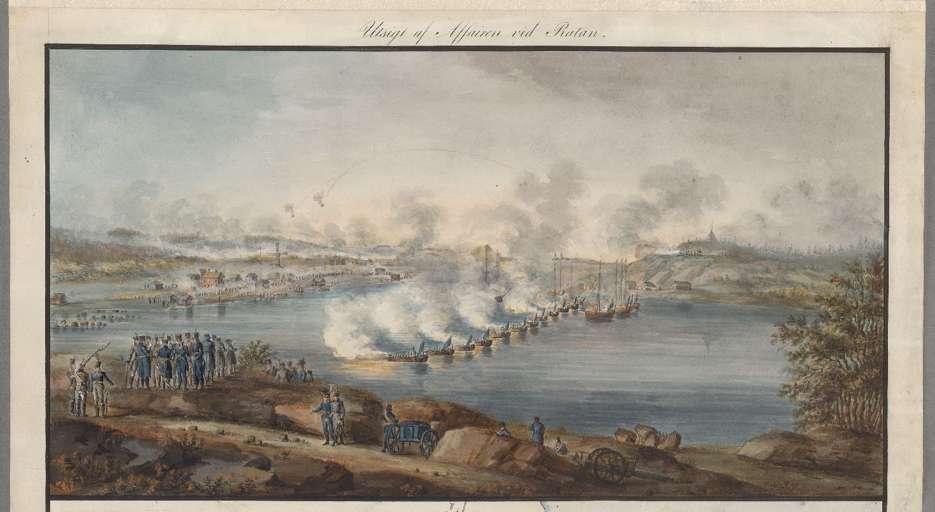

The Arctic region was not among the pivots of the World War II, although hot warfare took place in a few spots in the European Arctic. In the Pacific North, fighting was focused on the southernmost islands of the Aleutian, which Japan occupied for a short time, in 1942-1943.

The Norwegian and Barents Seas, as parts of the Atlantic Ocean, were real battle fields for maritime war, in particular submarine and anti-submarine warfare. The Allies transported military assets, including equipment and ammunition, as well as other material assistance, for the Soviet Union, and German submarines hunted these civilian cargo ships like wolves. “Escorts to Murmansk”, so named after the final destination on the northernmost coast of the Kola Peninsula, became one of the metaphors of the Arctic war front.

Interestingly, due to its ice-free coast, and the railway to St. Petersburg, Murmansk faced for a while hot warfare already in World War I, when British and Finnish troops were fighting with Russian white generals against the Soviet Russia.

It was not only about naval forces and fighting at sea, since in the European Arctic there were also constant air battles and fighting on the ground between Germany and Soviet Union. This contrasts with the fighting of the Winter and Continuous Wars between Finnish and Soviet troops, which mostly took place in southern fronts, except fighting over Petsamo in the Winter War. The German bombers bombed Murmansk and its harbors, and Soviet ones Kirkenes and other locations in northernmost Norway. After occupying Denmark and Norway in spring 1940, Nazi Germany had quickly entered into the coast of Barents Sea and the Soviet border, and received (almost) total control of the Nordic part of the European Arctic, including the northernmost part (almost half) of Finland, by allying with Finland after Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941.

Nonetheless, German troops never managed to conquer Murmansk, the Allies’ aid to Soviet Union continued to run, and the front was stuck in the Western part of the Kola Peninsula. The real turn started after Finland entered into a ceasefire with the Soviet Union, in September 1944, and had to push German troops out of its territory, which meant Finland’s third war within World War II. Germany paid back this revanche by destroying and burning the infrastructure of the entire Lapland, from small houses to big bridges and main roads, which pushed Lapland’s residents to be evacuated to Sweden.

A minor episode of the war, though a serious act, was when Great Britain “invaded and occupied Iceland” in May 1940, which the Icelandic Prime Minister described “as a precaution against possible German action against Iceland” after the Nazi Germany had occupied Denmark. Although “an occupied country [Iceland] had no to say in presence of British troops… by inviting U.S. troops to Iceland the government of Iceland was making a sovereign decision to accept U.S. military protection” (Petursson 2020, 34).

All in all, the World War II meant severe fighting and moving fronts, in 1941-1945, between Germany and Soviet Union in the European Arctic, in real Arctic climate conditions. Important geopolitical factors started to emerge: Firstly, the experience of warfare in cold conditions, and the revolution in military technology, manifested by the explosion of the atomic bombs in Japan; and secondly, the strategic implications of the shortest distance between the (new) superpowers, the Soviet Union and the USA, being over the Arctic Ocean; and thirdly, that certain strategic minerals, at the time nickel, played a more important role in the superpowers’ arms race and geopolitics in general.

More relevant in the long run is the legacy of the World War II that since then, there has neither been wars nor armed conflicts, nor disputes on sovereignty, in the entire region. That is until the Ukrainian drone strikes on Russian airport on the Kola Peninsula destroyed two strategic nuclear bombers (parked in open air due to START Treaty), an attack that could be interpreted, as many did, as a breaking of the peaceful state of Arctic security. In fact, according to the data by professionals, in particular the SIPRI Yearbook, it did not qualify as an armed conflict per se1, but yet was a damaging hit against the Russian nuclear triad which could have long-term consequences militarily and potentially affect the US-Russian arms control negotiations.

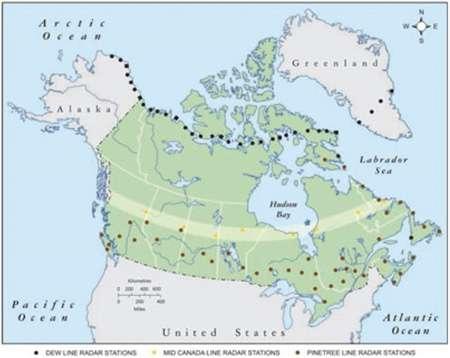

Correspondingly, the legacy of the Cold War in the Arctic, partly based on the legacy of World War II, could be interpreted to include among other things: firstly, two powers of the Allies, the Soviet Union and the USA, later becoming enemies, started to deploy heavyweight military structures, in particular nuclear weapon systems, in the Arctic: nuclear submarines patrolling in Arctic waters, radar stations searching for attacks by a potential enemy, and nuclear bombers in alert to reach the targets on the other side if needed; secondly, the original nature of Arctic military was, and is still, global “nuclear deterrence” with the capability of carrying out a second strike in retaliation if attacked, as the main premise of the nuclear weapon system (Heininen 2024); thirdly, the strategic military importance of the nuclear weapon systems makes the Arctic geostrategically important for the major nuclear weapons powers, and forces them to negotiate on nuclear arms control, if not disarmament, including to agree to extend the New START after its expiration of February 2026. Ironically, all this has supported the high geopolitical stability and peace in the region - one more Arctic paradox if you wish.

Finally and interestingly, the Cold War period also showed, even manifested, small northern states’ influence, punching above their weight, in the post-World War international rule-based order world system, as well as an importance of soft-power based on negotiations (though assisted by the USA and NATO membership) in the case of Iceland. Iceland unilaterally extended its Exclusive Economic Zone, EEZ to 12 nautical miles (in 1961), 50 nautical miles (in 1973), and 200 nautical miles (in 1976), although this was heavily opposed by European great powers. It took three socalled Cod Wars, in 1958-1976, between Britain and Iceland before Britain gave up and the 200 nautical miles EEZ became part of UNCLOS (e.g. Petursson 2020, 50-78).

Conclusions

Hot war and warfare in the Arctic region is a rare thing, limited even during World War II and occurring mostly in the European Arctic (northernmost part of Norway, Finnish Lapland, eastern parts of the Kola Peninsula). Interestingly, warfare in the Arctic has not occurred between two or more Arctic states, but between an Arctic state and an invader / aggressor from outside (British troops in World War I, Nazi Germany in World War II, Britain in the Cod Wars).

Most important geopolitically, and from the point of view of people(s), is the legacies of the World War II and the Cold War that since them, there has neither been wars or armed conflicts, nor conflicts over sovereignty, in the entire Arctic region. Although not much discussed today, the fact that the previous wars have fundamentally shaped Arctic geopolitics and Arctic security could be interpreted as a lesson from the past.

T his mostly manifested as an absence of hot war. Ongoing Arctic cooperation, based on the Arctic diplomatic model, still lends itself to, and has built a foundation for, positive peace

Note

1. An armed conflict is “where more than 1000 battle-related deaths have been incurred during the course of the conflict”, and war is defined to cause more than 1000 deaths during a year (Wallersteen & Axell 1994, p. 333).

References

Fabbro, D. (1978). Peaceful societies: An introduction. Journal of Peace Research, 15(1), 67–83.

Falk, R. A., & Kim, S. S. (1980). General introduction. In R. A. Falk & S. S. Kim (Eds.), The war system: An interdisciplinary approach (pp. 1–12). Westview Press.

Gorbachev, M. (1987, October 2). The speech of President Mikhail Gorbachev on October 2, in Murmansk. Pravda.

Harle, V. (1991). Hyvä, paha, ystävä, vihollinen (Rauhankirjallisuuden edistämisseura ry, Rauhan ja konfliktintutkimuslaitos, tutkimuksia, No. 44). Jyväskylä.

Heininen, L. (2024). Geopolitical features, common interests and the climate crisis: The case of the Arctic. Geneva Paper, 35/24. GCSP. https://www.gcsp.ch

Heininen, L., Everett, K., Padrtova, B., & Reissell, A. (2020). Arctic policies and strategies – Analysis, synthesis, and trends. IIASA & Ministry for Foreign Affairs of Finland. https://doi.org/10.22022/AFI/11-2019.16175

ICC. (1992). Principles and elements for comprehensive Arctic policy. McGill University, Centre for Northern Studies and Research.

Jervis, R. (1989). War and misperception. In R. Rotberg & T. Rabb (Eds.), The origin and prevention of major wars (pp. 101–126). Cambridge University Press.

Lamy, S. L., Masker, J. S., Baylis, J., Smith, S., & Owens, P. (2023). Introduction to global politics. Oxford University Press.

Mazower, M. (2017, April 15–16). War or peace? Financial Times Weekend, p. 8.

Petursson, G. (2020). The defence relationship of Iceland and the United States and the closure of Keflavik Base (Acta electronica Universitatis Lapponiensis 285). University of Lapland.

Romssa – Tromsø Statement. (2025). On the occasion of the Fourteenth Ministerial Meeting of the Arctic Council, 12 May 2025.

United Nations. (2025). Charter of the United Nations (Full text). https://www.un.org/en/aboutus/un-charter/full-text

Virtanen, H. (2007). Onko sota geeneissämme? Tieteessä tapahtuu, 3, 56–58.

Wallensteen, P., & Axell, K. (1994). Conflict resolution and the end of the Cold War, 1989–93. Journal of Peace Research, 31(3), 333–349.

Waltz, K. N. (1989). The origin of war in neorealist theory. In R. Rotberg & T. Rabb (Eds.), The origin and prevention of major wars (pp. 39–52). Cambridge University Press.

Westing, A. H. (1990). Towards eliminating war as an instrument of foreign policy. Bulletin of Peace Proposals, 21(1), 29–35.

The White House. (2022). National strategy for the Arctic region https://bidenwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/National-Strategyfor-the-Arctic-Region.pdf

Wright, Q. (1951). The nature of conflict. Western Political Quarterly, 4(2). (Reprinted with permission of the University of Utah and the author.)

Commentary

War and Peace: A Classic for the Times

Hasan Akintug

War and Peace by Leo Tolstoy truly is a mammoth of not only Russian literature, but also a world classic in its own right. Spanning over a thousand pages in most versions, the book depicts the Napoleonic wars from a Russian perspective Tolstoy utilizes several characters that belong to the upper classes of 19th century Russian society. These characters in turn drive the plot and Tolstoy shifts between the personal lives of these upper-class representatives, narratives of the war between Russia and France, and his own philosophical interpretations regarding human ontology and individual agency.

By no means is War and Peace an easy read. Published serially between 1865 and 1869, the shift between narration, description, and philosophizing may make reading the book somewhat disorienting to the unassuming reader. The sheer volume of named characters also contributes to the intensity of the reading experience. While most main characters are from the Russian aristocracy, Tolstoy portrays the tensions between them and the Russian peasantry throughout the book.

The five main families (Bezukhovs, Bolkonskys, Rostovs, Kuragins, and Drubetskoys) are fictional but historical characters, not least Alexander II and Napoleon, also make appearances within the novel. Through the tripartite split between relationships, war narratives, and philosophical exposition, Tolstoy offers something for readers interested in different aspects of the human experience. However, none of these three elements are portrayed in a straightforwardly approving manner, and a clear skepticism of the human condition permeates the entire book.

From Tolstoy’s use of his characters, fictional or historical, it becomes apparent that he held a critical view on what many call the “great man theory” of histor y. Meaning that he is critical of explaining political phenomenon primarily through the agency of great leaders. While largely left behind in modern historiography and political science, the analysis of “great” men has all too often taken a disproportionate place in academic and media analyses. In War and Peace, leaders like Alexander I and Napoleon are portrayed as pretentious and arrogant, but ultimately subject to

Hasan Akintug is a PhD Candidate at the Centre for Nordic Studies, University of Helsinki.

the elements outside of their control. The aristocrats are subject to their own vices and the conditions of war as much as the peasantry.

Pierre Bezukhov serves as a protagonist through War and Peace. Many literary critics claim his journey was largely based off Tolstoy’s own experiences and serves as a conduit for Tolstoy’s own inner voice. Pierre inherits wealth from his aristocratic father and navigates his way through the ways of high society, war, and relationships, seeking the ultimate truth in life. Pierre seeks meaning in life by seeking novelties and glory. He seeks heroism on the battlefield with the aim of killing Napoleon and he also joins a Freemason lodge seeking community. However, Pierre ultimately finds happiness and meaning through his marriage to Natasha and not in the pursuit of grandeur. In other words, he finds peace internally and not in external acquisitions.

Does this masterpiece have anything to say about contemporary affairs? Absolutely. Par ticularly in an era of increased militarism and antagonistic relationships between different blocks of states, the absolute lack of glory in, and the absolute absurdity of war is a much-needed breath of fresh air. Tolstoy writes from a Russian perspective, in that he analyses the Napoleonic wars as it pertains to the experience of Russia and does not attempt to portray the Russian side as valiant heroes at all. He portrays the hopelessness and vanity of human beings at war above all else and their submission to external circumstances and structures with undertones of religious (in his case Orthodox Christian) mysticism.

The interaction between individual agency against the structure has been a core debate with the discipline of political science and other social sciences. Tolstoy’s perspective clearly lands on the structuralist side which downplays the role of individuals in the broader machinery of society and the state. Nevertheless, in this work, he does have a pessimistic interpretation of human agency and calls for an introspection to recognize the unconscious dependencies we are subject to. Tolstoy wrote roughly a century before social constructivism became a substantial school of thought in the political sciences, but it would have been fascinating if he could have had the chance to interact with that body of theoretical literature which stresses the contingency of human knowledge. The second epilogue of the book is essential reading for those interested in the structure-agent discussions in history and social sciences.

As a participant of the Calotte Academy 2025, I could not help but consider the links between this year’s theme Europe between “militarization” and “the green transition” and Tolstoy’s classic. We live in a time where climate policy ambitions are being scaled back in favour of military expenditure to “reassure” populations that war will not come to their people. The policy framing is almost always put forward as an “inevitable” decision that “needs” to be taken for the “survival” of the group in question. For example, Finland, a country with a strong tradition of peace work and innovative climate policy, stopped allocating grants to peace organizations in 2024, and is considerating taxing electric vehicles.

Instead of contingent interpretations, we seem to have entered an era of essentialism where predecided conceptualizations of the “good” and the “evil” are hardened concepts and the only choice is to side with the “good” with no questioning as to what “good” actually means. Similarly, an excessive focus on the personality of contemporary leaders as opposed to broader underlying political causes of military conflict seems to be a problem that we still carry today.

Perhaps Tolstoy was right in asking for an introspection of the unconscious dependencies that human beings are subject to. If we want peace across societies and states, and peace between humanity and the climate, maybe it is time to accept our limitations and prepare for peace.

I. Pr ojecting Power in the Arctic

Kalaallit Nunaat as a foreign and security policy actor1

Sara Olsvig and Ulrik Pram Gad

The management of foreign and security policy within the Kingdom of Denmark has continually undergone a series of changes in response to shifting great-power dynamics and structural conditions. Not least, Kalaallit Nunaat’s Home Rule Government and later Self-Government has attained increased formal and substantive authority over aspects of foreign policy, as well as a distinct influence on the Realm’s security policy in the Arctic. Both the evolving geopolitical environment and the internal reconfigurations of the Realm generate new strategic challenges for the Kingdom as a whole, for its individual constituent parts, and for external powers. In this context, understanding Kalaallit Nunaat as a security-policy actor becomes essential.

This chapter first outlines the formal frameworks that constitute the Self-Government as an actor, along with the historical developments that produced them. It then characterizes Kalaallit Nunaat’s foreign-policy identity and the central goals and interests pursued on that basis. Finally, it examines the information and decision-making structures between Denmark and Kalaallit Nunaat and within the Self-Government, shaping how these goals and interests are pursued both proactively and reactively in practice. The chapter concludes by discussing how the boundary between “security policy,” on the one hand, and “ordinary” foreign policy withing legislative areas taken home by Kalaallit Nunaat on the other, emerges as the central challenge for both the realization of Kalaallit Nunaat’s long-term ambition for further self-determination and for its internal decisionmaking structures.

Introduction: Kalaallit Nunaat in foreign and security policy2

Increased attention and activity in the Arctic due to climate change and shifting global great power dynamics have created new strategic challenges for both the Kingdom of Denmark (hereafter the Realm) and its constituents namely Denmark, Kalaallit Nunaat (Greenland) and the Faroe Islands These challenges have highlighted significant shifts in the handling of foreign and security policy in the Realm: The Danish state can no longer exercise the same level of authority over Kalaallit Nunaat in foreign and security policy as it did when Kalaallit Nunaat was a colony. In contrast to most other non-sovereign countries and regions, Kalaallit Nunaat's paradiplomacy (Kuznetsov, 2014; Kristensen & Rahbek-Clemmensen, 2018) extends to parts of security policy. Since interests are not always seen as overlapping, the major political challenges continuously give rise to tensions between Nuuk (Kalaallit Nunaat) and Copenhagen (Denmark).

Dr. Sara Olsvig, research affiliate, Ilisimatusarfik - The University of Greenland

Dr. Ulrik Pram Gad, senior researcher, Danish Institute for International Studies

From a strictly Realist perspective, Kalaallit Nunaat 'disappears' as a foreign and security policy actor on the international stage in an analysis that focuses on military capabilities and economic might - much like Denmark would be unable to make much of a difference in the event of a war between great powers. However, reality is more complex. The US maintains an agreement with Denmark that facilitates its military actions in Kalaallit Nunaat - and in parallel, Denmark no longer conducts foreign and security policy without Kalaallit Nunaat's consent. Understanding this dynamic requires, that one consider international politics as more than pure power politics. It highlights a need for analyses that consider how international politics unfolds in a manner that creates opportunities for the participation of even the smallest actors. The current challenges and tensions thus pose two questions for our understanding of the Realm’s relationship with the outside world: First, how has Kalaallit Nunaat, as a relatively small actor, carved out a role for itself in international politics? Second, what are the underlying tensions within the Realm related to foreign and security policy?

To address the first question, this article provides an analysis of Kalaallit Nunaat’s gradual emergence in the international society, through the application of well-established sociological concepts of norms, roles, and legitimacy. Moreover, this analytical approach is useful in the way it provides a conceptual apparatus that can be used to answer the article’s second question. Specifically, the article conceptualises the ‘Realm’ as a ‘society’ where Kalaallit Nunaat and Denmark produce legitimacy in relation to a set of norms and roles. Finally, the same concepts allow the analysis to narrow its focus to how specific actors in the parliamentary system responsible for Kalaallit Nunaat’s foreign and security policy in order to examine how they engage in the processes In doing so, the article thus offers a better understanding of the tensions that increased great power interest in the Arctic have created in the Realm.

The analysis focuses on Kalaallit Nunaat's relationship with the United States, as this relationship has been pivotal for significant shifts in the norms governing Kalaallit Nunaat's role in its foreign and security policy. This focus is particularly relevant because the relationship has been unambiguously defined as security policy – and thus belongs in the part of foreign policy where the formalized norms afford the most restricted role to Kalaallit Nunaat

The following section introduces the sociological framework that underpins the analysis. T he main body of the article examines three social spaces - or 'societies' - that structure the analysis: the international community, the Realm and the parliamentary system. These analyses lead to the broader conclusions about the challenges facing the Realm as a community

The concluding discussion argues that the delineation of 'security policy' from 'ordinary' foreign policy and from international dimensions of domestic affairs constitutes an independent challenge to the two key objectives: Denmark’s ambition to let the Realm speak with one voice, and Kalaallit Nunaat's long-term ambition for increased self-determination. Together with fundamental Kalaallit-Danish conflicts of interest on the one hand and various concrete parliamentary and bureaucratic procedures on the other, the impossibility of delineating security policy puts the Realm under pressure.

Analytical framework: Norms, roles and legitimacy – three social spaces

The aim of this article is to present an analytical narrative that explains how Kalaallit Nunaat, even though a very small actor, has been able to play its part in international relations and how the

difficulties of advancing into this field can be understood. The article argues that the history of Kalaallit Nunaat in international relations can be understood with the concepts of norms, roles and legitimacy.

T his analysis rests on the premise that relations between states are not just a question of how much power they have. Rather, states build a society that can be described using concepts developed by sociology to understand human relations within a society.3 Like a group of children in a schoolyard, states will have different roles in relation to each other; and there are norms for how children and states ‘should’ behave (Finnemore 1996: 15). Some norms are formalized in the form of international law, but unlike in the schoolyard there are no adults watching the international society If a state does something ‘illegal’ or ‘inappropriate’, the result is rarely a concrete punishment –rather, the other states will adjust their expectations of how to deal with the state in question in the future. Even if the teacher has gone for coffee, there are consequences if you smash a ball in the face of a classmate – but norms and sanctions are unevenly distributed, depending on your role in the social structure If you are a small child who has been bullied by a classmate, direct payback might be acceptable to your peers. If you are a big-time bully who could easily beat up the smaller kids, several strategies become available. You can continue fighting and cement a position based on fear – or you can show care, and in this way gain legitimacy within the community. In this way, you may not have to fight all the time and can avoid others ganging up on you in the long run. Formally, we can define ‘norms’ as the expected, socially accepted behaviour; ‘roles’ as a collection of norms linked to a specific position in a society; and ‘legitimacy’ as the ‘license to act’ that comes with adhering to roles and norms associated with one’s position (Finnemore & Sikkink 1998).

The article is grounded in an analytical distinction between three spaces or ‘societies’ as conceptualised here. (1) The international society of states, (2) The Realm consisting of Denmark, Kalaallit Nunaat and the Faroe Islands, and (3) the parliamentary system responsible for managing Kalaallit Nunaat’s foreign and security policy, including the Danish Government and Parliament (Folketinget) together with the Government of Kalaallit Nunaat (Naalakkersuisut) and parliament (Inatsisartut). The three ‘societies’ differ notably in levels of formalisation: when a norm is written down as legislation, deviations become more visible. If there is a formal authority at the head of the table, it is expected that violations will be sanctioned. However, a more fundamental distinction among the three societies lies in the criteria determining who qualifies as legitimate actors.

The international society is fundamentally composed of sovereign states (Watson 1992). However, the concept of ‘society’ has evolved (1992: 278), in large part due to the concept of popular sovereignty (1992: 294-5) Once a European monarch could no longer legitimately say ‘the state is me’ but had to act as a representative of ‘their’ people, it became even more difficult to exclude colonized peoples from demanding their own state or separate rights precisely because the state was not their own (Watson 1997). Collective identities – states and peoples – are, of course, represented by concrete individuals, but it is precisely as a collective that one becomes a meaningful actor in the international society (Manning 1962: 101-3).4 When the Realm does not merely act as a (Danish) unitary state but a more complex ‘society’, this is – as we shall see – linked to the development of a number of norms in the international society regarding how one can best be a state and a people. More generally, sovereign states are the typical actors in international society, but an increasing number of other types of collectives are attaining (partial) recognition as legitimate actors.

As a society, the Realm is clearly delineated, and everything except its three parts is positioned outside of it.5 For mally, ‘Kalaallit Nunaat’ and ‘Denmark’ emerge at intervals as distinct collective actors, for instance, when a minister or authorized official signs a document 'on behalf' of either polity. In less formal contexts, it may be less clear how much of a representative a given individual is, when speaking on behalf of ’his’ or ‘her’ country. Often, prejudices about and observations of how ordinary Kalaallit or Danes behave lead to expectations about how Kalaallit Nunaat or Denmark will act in relation to different norms.

To grasp these ambiguities surrounding the norms that determine who can assume different roles in relation to representing Kalaallit Nunaat, Denmark, and the Realm, we must examine norms, roles, and legitimacy in the third social space: the parliamentary arena. In this context, only individuals appear as actors T here are, of course, formalized procedures that govern how individuals can assume roles - or, in other words, where they can legitimately act as representatives. Entry into this 'society's' hierarchy of roles is secured through election to parliament by the population, appointment as a minister by parliament, or employment as a civil servant to act 'on behalf of the minister'.6 However, as will be demonstrated, the lack of formalization of parliamentary norms in Kalaallit Nunaat can create ambiguity about the scope of representativity and legitimacy, even when a Prime Minister of Naalakkersuisut speaks on behalf of 'Kalaallit Nunaat'.

First space: Global norms and Kalaallit Nunaat's political identity

Before we delve into the specific review of the norms that Kalaallit Nunaat and the Realm have developed, it is necessary to provide an introduction to Kalaallit Nunaat’s integration into the Western state-based international society from 1721.7 In real terms, it began with the meeting between the Inuit and Hans Egede and the subsequent colonization project that followed During their first meetings with Christian missionaries, Inuit had an identity that was fundamentally different from that of the Norse People, European whalers, and other explorers. A distinct political identity towards the colonizing power – a self-understanding as an acting collective based on the island of Kalaallit Nunaat – emerged when encountering the Danish colonial power. This process unfolded partly in opposition to the Qallunaat (the white people) (Sørensen 1994: 109), and partly through interaction with the shifting norms introduced by colonizers regarding what it meant to be a People – or in other words; the norms that would allow Kalaallit as a collective identity within the world order the colonizers brought with them (Sørensen 1994: 168-9; Petersen 1991: 20; Gad 2017a: 45). European notions of their own racial superiority were, however, distinctly challenged by Inuit's obvious technological superiority under Arctic conditions (cf. Hastrup 2000:4), and for extended periods, the colonial project relied on maintaining cultural difference. In fact, the economic viability of the Danish colonial project was dependent on Inuit maintaining the part of their material culture that made seal hunting possible (Graugaard 2018). Hence, Denmark could–both towards Kalaallit Nunaat and externally – legitimize its supremacy by contrasting the continuation of Kalaallit identity with the miserable fate of “native” people elsewhere (Rink 1817).

Formal decolonization

This division of roles was rendered impossible by the new norms established by the United Nations in the aftermath of the Second World War. On the one hand, overt racial hierarchies were now delegitimized (Watsson 1992). On the other hand, the right of peoples to self-determination was extended to previously ‘non-self-governing territories’ (1992: 294-5). The UN Charter articulated

Kalaallit Nunaat as a foreign and security policy actor

several principles relating to the development and advancement of self-government, the establishment of free political institutions among colonized peoples, and the fostering of interethnic harmony and security (UN, 1945). In response to these emerging norms, the Danish state formally integrated Kalaallit Nunaat as an equal part of its Realm by the constitutional amendment in 1953 (Beukel et al 2010). Whether Kalaallit politicians and decision-makers at the time were fully informed about the range of options for decolonization processes discussed in the UN remains a matter of debate (Kleist 2019; Beukel et al. 2010). Nonetheless, the Kalaallit Nunaat public initially embraced this approach as part of a broader narrative of Kalaallit Nunaat's rise from poverty (Heinrich 2012).

1721 Hans Egede’s landing

1941 Kauffmann’s agreement with the U.S. on the defence of Kalaallit Nunaat

1951 Renewed agreement between Denmark and the U.S. on the defence of Kalaallit Nunaat

1953 Kalaallit Nunaat is absorbed into the Danish Constitution

1973 Kalaallit Nunaat becomes member of the European Community together with Denmark

1979 Home Rule Government is introduced

1982 Kalaallit Nunaat by referendum decides to leave the European Community

1985 Inatsisartut - the Parliament of Kalaallit Nunaat establishes its Foreign and Security Policy Committee

1991 The Home Rule Government takes over Kangerlussuaq airport and joins the Permanent Committee that oversees US military activities in Greenland

2003 The Itilleq Declaration on Kalaallit Nunaat’s participation in foreign and security policy decision-making is signed

2004 The Igaliku Agreement on Kalaallit Nunaat as a party to the Defence Agreement and the relation to the U.S. is signed

2005 The Authorization Act formalises the Itilleq Agreement

2009 Self-Government is introduced

2014 The base maintenance contract at T hule Air Base (now Pituffik Space Base) is awarded to an American company rather than to Greenland Resources, part-owned by the Government of Greenland

2020 The U.S. announces an ’aid-package’ and a new framework agreement on the base maintenance issue is signed

Figure 1. Timeline of the changes in Kalaallit Nunaat’s status in relation to foreign and security policy.

During the 1960s and 1970s, however, an increasingly broad segment of the Kalaallit population reacted to the stark contrast between the ever-increasing inf lux of Danes tasked with building the welfare state in Kalaallit Nunaat and the population that was to be modernized. The acute cultural contrast gave rise to a distinct nationalism (Dahl 1986), which over the decades culminated in

aspirations to realize the prevailing international norm of peoplehood: having one’s own state (Gad 2017a). The result was a political identity grounded in the norm of the nation as a community of destiny – Kalaallit Nunaat understood as a culturally conditioned collective, responsible for its own development (Thuesen 1988; Gad 2017a).

Home rule

Kalaallit Nunaat achieved Home Rule in 1979. The Home Rule Act established a separate parliament, Inatsisartut8 and executive Naalakkersuisut (The Prime Minister’s Office 1979). At the same time, a number of Kalaallit actors participated in building international cooperation among peoples who had been left behind by the wave of decolonization following the Second World War (Dahl 2012). Legally, these efforts culminated in the UN Declaration that Indigenous Peoples are peoples equal to other peoples with the right to self-determination, the right to self-identification, and the right to determine their own development (UN 2007). Alongside this formalized legal norm, a more diffuse, informal norm exists that gives parts of the international public an expectation that Indigenous Peoples are positioned as a minority either in opposition to or with special rights in relation to a ‘foreign’ state (Jacobsen & Gad 2017). Kalaallit Nunaat’s geographical separation from Denmark, however, made it evident for Kalaallit politicians that the obvious way forward would be pragmatically merging their identity as an Indigenous People with the desire for self-determination and the national project of establishing a state of their own. This pragmatic fusion gives Kalaallit Nunaat more leeway in international politics in certain contexts (Jacobsen & Gad 2017; Petersen 2006), just as this ‘constructive ambiguity’ provides a certain flexibility in relation to which contexts and from which angle Kalaallit Nunaat can approach foreign and security policy matters. Conversely, it can also cause outsiders to misread Kalaallit Nunaat's course if underpinned by outdated notions that associate ‘Indigenous’ with something primitive or traditionalist (Dahl 2012).

Self-government

In 2009, home r ule, again at Kalaallit Nunaat’s initiative, was transformed into self-government. While the two arrangements are broadly similar in their institutional structure, they differ significantly in terms of their relation to international law Specifically, the Self-Government Act affirms the recognition of the Kalaallit people under international law. Politically, the Act is not only regarded as the framework for expanding the competencies that began under home rule but also as an explicit pathway towards enhanced self-determination, with the ultimate goal of achieving full independence.9 Throughout the period of Home Rule and Self-Government, the pursuit of increased self-determination and, ultimately, independence have been a central driver in both the development of the legal framework and in relation to the specific goals pursued within and on the margins of the legal framework. While there may be disagreement about the speed and choice of path, the direction for Kalaallit Nunaat is focused on increased self-government, increased economic self-reliance, increased political independence internationally and ultimately statehood. There is broad agreement (Isbosethsen 2018) that economic self-reliance is a prerequisite for actual secession from Denmark, but this does not mean that economic self-reliance is a prerequisite for an independent voice internationally. When the path towards independence and self-reliance intersects with foreign and security policy, a grey zone arises within the Realm

Kalaallit Nunaat as a foreign and security policy actor

Second space: Formal and informal frameworks for the Government of Kalaallit Nunaat as a foreign and security policy actor

In the international society, the prevailing norm is that a state speaks with a single, unified voice. As described, however, Kalaallit Nunaat has - by virtue of international norms on decolonization - gradually gained an unusually significant space to manoeuvre despite not being a sovereign state Specifically, this has occurred because the Realm has gradually developed a number of internal norms that establish a framework for how Kalaallit Nunaat can act in foreign and security policy. Consequently, the Realm contains a constitutional ambiguity that can be difficult for outside actors to grasp. This section examines these norms and how Kalaallit Nunaat has fought for them, based on concrete experiences and needs, particularly in relation to the American military installations.

Official interpretations of Danish constitutional law continue to assert that what we know as the Realm is legally a unitary state (Gad 2020b; Harhoff 1993: 73; Spiermann 2007: 11). From this perspective, the competences of the g overnment of Kalaallit Nunaat – including in the foreign affairs area – are delegated from the Danish government (Gad 2020b). By contrast, legal scholars argue that the home rule and self-government arrangements have become a constitutional custom (above or alongside the written constitution expressed in the theConstitutional Act of Denmark, so to speak) that cannot be unilaterally revoked (Harhoff 1993; Spiermann 2007). Moreover, Kalaallit Nunaat – most recently in the preamble to the Self-Government Act – is now recognized as a subject under international law Because the Self-Government Act is based on an agreement between two subjects under international law, it cannot be unilaterally revoked by one party. T his recognition entails the right to independence – and Spiermann (2007: 120-3) argues that when one can ‘take home’ all sovereignty through independence, taking home parts of sovereignty, including, e.g., over foreign and security policy competences, must also be possible. Successive Danish prime ministers have responded ambiguously when formally questioned on the matter in parliament T hey have nonetheless tended to conclude that the Home Rule and Self-Government Acts constitute practically and morally binding agreements that should not be changed unilaterally by Folketinget (the Danish Parliament) without the consent of the authorities in Kalaallit Nunaat (Rasmussen, 2018). T he development of these formal and informal norms within the Realm has, in practice, pushed the international community's norm of the unitary state's monopoly on security policy into the background. Ultimately, the relationship is more political than legal: Denmark cannot rely on an outdated colonial interpretation of how foreign and security policy competencies are distributed because such an interpretation would propel Kalaallit Nunaat toward declaring independence.

Over the past decade, Denmark has sought to communicate more consistently when, in foreign policy contexts, there is a 'unity of the Realm' acting and when there is a 'community of the Realm', or - as previously referred to in, e.g. the Arctic Council, "Denmark, Greenland and the Faroe Islands" (Jacobsen 2019a). When U S Secretary of State Mike Pompeo spoke about his meeting with "the three ministers" from Kalaallit Nunaat, the Faroe Islands and Denmark during his visit to Denmark in 2020, it was important for the Danish Foreign Minister and in particular the Danish press to refer to the meeting as a meeting between two foreign ministers - the Danish and the American - with the participation of "representatives from Kalaallit Nunaat and the Faroe Islands" (Krog 2020). Kalaallit Nunaat has formally insisted on equality by using the English terms Minister and Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

International aspects of devolved competencies

The practical implementation of Home Rule involved Kalaallit Nunaat taking over legislative and executive powers in a wide range of areas. The Self-Government Act expanded the scope of areas devolvable to encompass virtually all the powers required for a nation to be considered selfgoverning. However, official Danish interpretation of constitutional law lists a series of core competencies that cannot be devolved because they are deemed crucial for the formation of a state as such. These include foreign affairs, security and defence affairs, citizenship, the Supreme Court, as well as currency and monetary policy (Naalakkersuisut 2008).10

On the one hand, foreign, security, and defence policy remain the prerogative of Copenhagen, and the Self-Government Act explicitly states that none of the devolved powers of the SelfGovernment formally constrain the constitutional responsibilities and powers of the Danish authorities in international affairs. On the other hand, Chapter 4 of the Act describes Kalaallit Nunaat’s powers in foreign affairs. These powers are largely a formalization of practices that were developed by Kalaallit Nunaat’s parliament and government, who demanded and gained influence before being formally ‘allowed’ to do so (Spiermann 2007:126-7; Gad 2017a). Denmark’s preferred role as a Nordic-style benevolent good participant in the international community (Ren et al. 2020; Gad 2016; Thisted 2014) further necessitates flexibility in the application of the international norm of state unity. The result is that Kalaallit Nunaat’s creative paradiplomatic practices have been institutionalised over the years as norms of the Realm

From Thule over Itilleq to Igaliku

The relationship between Kalaallit Nunaat and the United States has been a key driver in the expansion of the competencies of Kalaallit Nunaat in foreign and security policy during both the Home Rule and the Self-Government era. Notably, the one US military base in Kalaallit Nunaat that remains active today, Pituffik Space Base, produced – when it was still known as Thule Air Base - a series of controversies that makes it hard for Denmark to deny Kalaallit Nunaat’s demands for transparency and participation in decision-making. This challenge is further compounded by the fact that the establishment of the Defence Agreement with the U.S. in 1951 occurred under evidently colonial conditions, which sharply contrast with current global discourses on the right to self-determination of all peoples. In the final months before the extension of constitutionally enshrined civil rights to Kalaallit Nunaat in 1953, several hundred Inughuit were forcibly relocated to facilitate an expansion of the base (Brøsted & Fægteborg 1985). Later, in 1968, a B-52 bomber crashed on the ice-covered fjord by the base, making it clear that the Danish policy of not accepting nuclear weapons on its territory was not being adhered to in Kalaallit Nunaat (Amstrup 1997). Since then, concerns have emerged regarding pollution from the base and abandoned defence installations, particularly the nuclear-powered Camp Century, located beneath the inland ice sheet (Nielsen & Nielsen 2016), as well as occasional complaints about how the management of the base has obstructed economic development in the district (Gad 2017b). Based on findings from Danish archives (Brøsted & Fægteborg 1985) and supported by the Indigenous Peoples’ Organization Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC), a group called Hingitaq’53 [the displaced] obtained a court ruling affirming that the Inughuit’s relocation was indeed forced. In parallel, in 1995, a secret agreement from 1957 between Denmark and the U S was revealed This agreement allowed the U S to store nuclear weapons in Kalaallit Nunaat (Brink 1997), making Denmark more clearly responsible for the pollution from US defence activities. The revelations understandably spurred a distrust of

Denmark in Kalaallit Nunaat and became a clear incentive for Kalaallit Nunaat and Kalaallit to identify and show solidarity with the world's Indigenous and colonized Peoples. In particular, it was an incentive to insist on Kalaallit Nunaat’s involvement and full information Moreover, the revelations made Denmark vulnerable to being exposed as a hypocritical colonial power (Kristensen 2005).

Kalaallit Nunaat's involvement as a party in negotiations between the U.S. and Denmark was triggered by the U S government's plans to upgrade the base to incorporate it into its missile defence system (Kristensen 2004; Dragsdal 2005). Kalaallit Nunaat's primary concern was directed more towards participation and self-determination, rather than towards questions regarding what role it should play in relation to world peace and the militarization of the Arctic (Dragsdal 2005).

As an initial outcome of this process, a joint Kalaallit Nunaat-Danish declaration, named after the settlement Itilleq, formulated a number of basic norms in 2003, stating that it is "natural" that Kalaallit Nunaat is involved and has influence on foreign and security policy issues of importance to Kalaallit Nunaat, that "the natural starting point" is that the Government participates in international negotiations of special interest, just as it is "natural" that the Government can be a signatory to agreements binding under international law on behalf of the Realm (The Foreign Ministry of Denmark 2003).11

Building on the constitutional concession by the Danish state explicated in the Itilleq Declaration, tripartite negotiations were initiated with the Americans. These negotiations were held partly to modernize the 1951 defence agreement and partly to upgrade the radar at the base (Kristensen 2005; Jacobsen 2019b). The outcome was a series of agreements known as the Igaliku Agreement. Firstly, the defence agreement was supplemented with a new document, in which Kalaallit Nunaat, as a co-signatory, is recognized as a party. Central to the main text of the agreement are provisions on involvement which describe:

• How the U S is obligated to 'consult with and inform the Government of the Kingdom of Denmark, including the Greenland Home Rule Government, prior to the implementation of any significant changes to United States military operations or facilities in Greenland ' (The Foreign Ministry of Denmark 2004)

• How the parties ’shall consult without undue delay regarding any question which one of the Parties may raise concerning matters pertaining to the U.S. military presence in Greenland and Defense Agreement and [the Igaliku] Agreement' (The Foreign Ministry of Denmark 2004)

The agreement’s preamble also includes a provision oblig ating Denmark to “always consults and cooperates closely with the Home Rule Government of Greenland in affairs of state of particular importance to Greenland.”

A joint declaration on environmental protection further placed the mitigation of pollution from the base on the agenda of a new subcommittee of the Permanent Committee where the U S , Denmark, and - now also formally - Kalaallit Nunaat have been discussing practical matters regarding the base areas since 1991 (The Foreign Ministry of Denmark 1991). Moreover, a joint declaration on economic and technical cooperation established a so-called Joint Committee with the aim of creating a “broad technical and economic cooperation” between the U.S. and Kalaallit Nunaat Kalaallit politicians viewed the economic agreement between Kalaallit Nunaat and the

United States not only as a means to address and redress the historical subordination of Kalaallit Nunaat’s interests but also as an opportunity to secure revenue for the country - revenue that could, over time, reduce Kalaallit Nunaat's dependence on Danish subsidies. The entire agreement thus pointed both backward, toward the historical injustices committed against Indigenous Peoples under colonial conditions, and forward, toward greater independence of Kalaallit Nunaat, both politically and economically.

From Joint Committee over base maintenance contract to purchase offer

None of the forward-looking perspectives immediately fulfilled expectations, but the responsibility for this shortfall appears unevenly distributed In particular, the Joint Committee intended to foster economic and technical cooperation between Kalaallit Nunaat and the U.S. never clearly defined areas where American grants could address specific Kalaallit Nunaat’s needs beyond a scholarship here and a study tour there. Economically, the relationship with the U.S. reached a low point when, in 2014, the U S awarded the maintenance contract for the base to a U.S. company. This decision came about as the combined result of American bureaucratic sleep walking, the Danish Foreign Ministry's reluctance to engage, and bizarre mis-prioritizations on the part of the Government of Kalaallit Nunaat leadership (cf. Spiermann 2015), which deprived Kalaallit Nunaat of the threedigit million DKK income it had enjoyed for decades through co-ownership of the DanishKalaallit company that previously held the maintenance contract.

Soon, a renewed U.S. security policy focus on the Arctic took a more assertive stance, signalling a shift in the regional strategic environment. Trump’s 2019 offer to purchase was clearly out of step with the norms of the international community as well as those of the Realm but behind the scenes both the Pentagon and the U.S. State Department had been preparing concrete advances. However, Kalaallit Nunaat had “more birds on the roof than in its hand”: A U S Deputy Secretary of Defence stated that the U S was prepared to co-finance dual-use infrastructure in Kalaallit Nunaat (U.S. Embassy Denmark 2020b). T he situation was further complicated when Denmark effectively precluded Chinese involvement in Kalaallit Nunaat’s new airports by offering a lucrative financial package (Sørensen 2018), leaving the public uncertain about the specific contributions the U.S. intended to make. In October 2020, an agreement - acceptable to all parties - was reached concerning the terms for the next tender for the base maintenance contract which took effect in 2024. However, apart from the ‘aid package' of consultancy services announced by the Americans in April 2020 (U.S. Embassy Denmark 2020a), a direct benefit for the Kalaallit Nunaat’s treasury and society from the base maintenance contract itself was still uncertain (Rahbek-Clemmesen 2020b).

The Danish government has placed considerable emphasis on the inclusion of Kalaallit Nunaat, not least after Trump's first intervention. After the establishment of the U.S. consulate in Nuuk, some communication has bypassed Copenhagen. Even so, Copenhagen insists in principle on the right to decide when devolved issues are of such importance security-wise that they cannot be left to Nuuk – even though the Government of Denmark prefers dialogue and payment rather than pulling the constitutional handbrake. The Danish identification with the role of the benign (de)colonizer pushes the norm of the unitary state's monopoly on security policy into the background. However, as we shall now see, this shifts the pressure on the Realm to the practical bureaucratic and parliamentary norms in the daily management of foreign and security policy.

Third space: The information and decision-making structures between Denmark and Kalaallit Nunaat and internally within the Government of Kalaallit Nunaat

To recapitulate: international society is composed of collective actors, which are typically sovereign states. Similarly, the overall norms in the Realm describe the division of competencies between Denmark and Kalaallit Nunaat However, the Realm - formally involving the two collective subjects, namely Denmark and Kalaallit Nunaat - is in practice embodied in a number of specific individuals endowed with distinct authority, including particularly parliamentarians, government ministers, officials, and diplomats. Kalaallit Nunaat’s foreign and security policy is therefore conducted within a political system that includes individuals and institutions in both Copenhagen and Nuuk. T he following discussion is focused on the norms and roles that Kalaallit Nunaat has developed for conducting foreign policy, as well as on the implications of how Kalaallit Nunaat’s and Danish parliamentary and bureaucratic systems are linked.

Secure

communication

The need for meetings to take place and information to be exchanged and processed under strict confidentiality has grown substantially in recent years Secure rooms and communication channels in the Self-Government approved by the police intelligence service have only been established in recent years Prior to that, the usefulness of a phone call from a Danish minister to Kalaallit Nunaat’a minister (Kongstad and Maressa 2019) may have been severely limited. An increasing number of security-cleared Kalaallit officials therefore long commuted to the headquarters of the Danish Joint Arctic Command at the harbour in Nuuk, where meetings and conversations could take place in a secure room and where documents could be exchanged via secure email. These documents might include briefings from the Danish government, either intended exclusively for the Kalaallit Nunaat Government or to be read out to the Foreign and Security Policy Committee of Kalaallit Nunaat’s parliament

Parliamentary inequity and the Norm of Simultaneity

T he Danish Parliament has a constitutional guarantee that the Government ‘consults’ with its Foreign Policy Committee (Udenrigspolitisk Nævn, UPN) before making decisions regarding major foreign policy implications (Folketinget 1953; Krunke 2003). Naalakkersuisut’s obligations towards the Danish Foreign Policy Committee’s equivalent in Kalaallit Nunaat, the Foreign and Security Policy Committee (Nunanut Allanut Sillimaniarnermullu Ataatsimiititaliaq, NASA) of the Inatsisartut, is significantly looser: NASA is tasked with ‘dealing with foreign and security policy matters and presenting the questions and comments to which these matters give rise. It is the committee’s responsibility to keep itself closely abreast of developments within its field of expertise' (Inatsisartut 2010). The committee works under the same strict confidentiality as the Danish Foreign Policy Committee but does not have the same constitutionally guaranteed right to be consulted by the government. In practice, this inequality between UPN and NASA has demonstrably created an imbalance in the level of information given to members of the Danish Parliament vis-à-vis the parliament of Kalaallit Nunaat. Usually, bias is in UPN's favour. Nonetheless, when the initiative originates from Nuuk, the roles, as we shall see, may be reversed.

With respect to the obligations towards Inatsisartut on the part of the Government of Denmark and Naalakkersuisut, the Danish Minister of Foreign Affairs has stated that ‘according to mutual understanding between the Danish Government and Naalakkersuisut, [a] fixed practice has been

Olsvig & Gad

established that information on issues of particular importance for Kalaallit Nunaat is given simultaneously in the [Folketinget’s] Foreign Policy Committee and Inatsisartut’s Foreign and Security Policy Committee’ (The Foreign Ministry of Denmark 2018). NASA members often, nevertheless, experience learning first about crucial and important foreign and security policy developments through the press rather than by being informed about them in the committee (Inatsisartut, 2018, 2019, 2019a). For example, when considering Danish co-financing of airport expansions, NASA expressed concern about the lack of information regarding the security policy aspects of the airport facilities (Kristiansen, 2019; Inatsisartut, 2018, 2019). A key factor contributing to this inequity is that the lack of secure communication channels previously mentioned has a doubly negative impact at the parliamentary level. Parliamentarians of Kalaallit Nunaat meet only a few months a year, and committee meetings are therefore often held over the phone or online.

The Parallelism Norm and the South-to-North Norm

The official Kalaallit articulation of the ‘simultaneity principle’ states that ‘information to the Foreign Policy Committee of the Danish Parliament on matters of importance to Kalaallit Nunaat is communicated to the g overnment of Kalaallit Nunaat, so that to the greatest extent possible, the Foreign and Security Policy Committee can be informed simultaneously’ (Inatsisartut 2010). T his formulation highlights that, in addition to the norm of simultaneity, two further separate norms operate in parallel

First, the procedure is grounded in the norm that the Danish Parliament and Inatsisartut are two separate but parallel parliamentary systems: the Danish Government is responsible for involving the UPN, while Naalakkersuisut is responsible for involving the NASA. This norm implies that the Danish Government sends briefings to Naalakkersuisut, which are then read out loud to the NASA. This norm thus involves Naalakkersuisut members perhaps being compelled to read documents out loud, which they disagree with in terms of content.

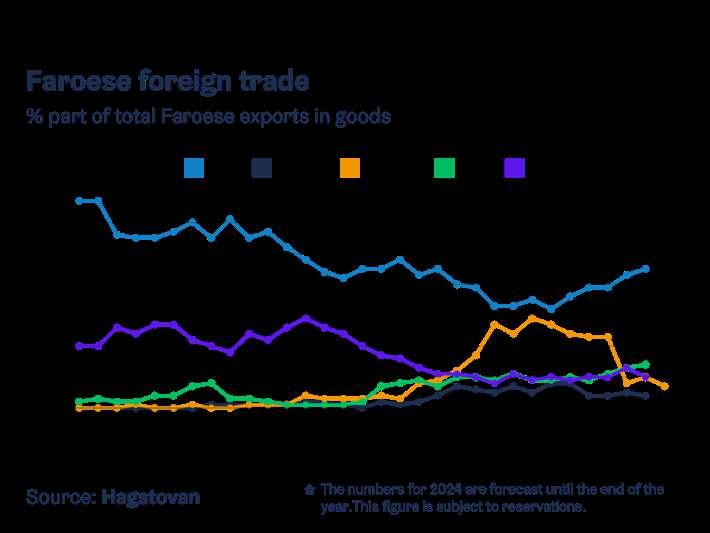

Second, the workflows established were designed to secure northbound information from Copenhagen to Nuuk: Basically, these workflows were established when the norm was for foreign, and especially security policy initiatives and information to come from Copenhagen. The primary purpose of the simultaneity procedure was to facilitate Kalaallit Nunaat's efforts to gain insight into security policy, thereby aligning with international norms for decolonization.