David Pagel

Sometimes a bicycle is just a bicycle—and not a symbol of anything more. But even when a bike is just a bike, it’s a pretty special thing. The most rudimentary two-wheeler gets you across town faster, more easily, and more efficiently than your feet can. And it does so less expensively, in the long run, than public transport or private vehicles—owned, leased, or rented. Plus, you never have to pay for parking, and you can park your bike just about anywhere, locking it to trees, street signs, parking meters—or other bikes, if you happen to travel in packs. Most important, any bike you ride gives you the freedom to create your own route as you spin through the city or ramble through the countryside, turning in any direction at any intersection or following any fork in the road, depending on traffic, stop lights, wind, hills, and whatever whims move you.

Some of the decisions that determine your route result from carefully thought-out plans, especially if you’re commuting or meeting someone at a certain time and place. At other times, though, these decisions—if they can even be called decisions—are more like impulses: raw, too-fast-to-think reactions that happen in an instant. Such seat-of-the-pants, shoot-from-the-hip responses occur in real time, or IRL, as you ride down the road or zigzag across streets and avenues, cutting from one lane to another as you slice through rows of slow-moving vehicles, each of which weighs about 200 times as much as your bicycle. The balance of power between bikes and cars is so crazily skewed toward motorized vehicles that all cyclists know, in their bones, what it’s like to be vulnerable—perhaps not quite powerless, but certainly on the low end of an uneven playing field.

Even so, being at the mercy of drivers and their behemoth vehicles doesn’t get in the way of the power and the pleasure of saddling up and heading out to wherever the road might take you. The feeling of unfettered freedom that comes with riding a bike is better than just about anything out there: It’s the sort of thing Thomas Jefferson might have had in mind when he penned those lines

in the Declaration of Independence about life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness—describing the nation the founding fathers wanted everyone, yes everyone, to live in. That freewheeling feeling of being unconstrained by your surroundings and uncontained by the rules that make business as usual nothing more than business as usual doesn’t just involve the feeling that anything is possible; it’s accompanied by the feeling that nothing is better than the current moment. Wherever you might be on your ride, the world, and your place in it, seem perfect.

That’s one of the beauties of bicycling: It lets you live in a world that’s part of the real one but is not overrun by the power relationships that define—and delimit—that reality. Riding a bike gives you access to a reality that unspools more swiftly than your brain can process your perceptions, much less send messages back to your torso and limbs so that you can react to whatever set of perceptions are coming at you. Bicycling lets you get out ahead of rationality, deliberation, and logical argumentation. It takes you to the edge of all that—and beyond—putting you in a time and a place that not only makes a virtue of improvisation (by making room for all manner of intuitions) but puts you in touch with impulses that link you to a reality that is bigger, better, and more thrilling than any inclinations in which egos—and the individuals that accompany them—dominate the ways we think about human identity and, generally, live our lives.

Jacob Hashimoto makes art that taps into those impulses. And he does it without requiring us to take our lives into our hands by setting off on journeys along roads anywhere around the globe where we’re forced to rub shoulders with cars, trucks, and buses—not to mention motorcycles and tractor-trailers. While standing still, in the comfort of a gallery, a museum, or your own home, Hashimoto invites us to embark on journeys filled with more intersections and forks in the road than just about any bike ride might include. The imaginative transport that his indescribably dense fields of fractured, infinitely rearrangeable pattern-fragments induce goes beyond anything you might experience on a bike, taking you, via your imagination, on even speedier trips, each filled with more rapid-fire turns and swift twists than can be had on the road. In addition to these thrilling, never-the-same-waytwice forays through time and space, Hashimoto’s works deliver more soul-expanding, scale-defying high jinks than can be had just about anywhere—whether on a bike (in real time, in real life) or in front of any other work of art (whether it was made recently or long ago).

To stand before any one of Hashimoto’s wall-mounted works and scan its multipart, multilayered surfaces is not to be lured into a complex web of myriad nooks-and-crannies so much as it is to be catapulted on a vertiginous, gravity-defying ride through a world of vivid, super-saturated colors and crisp, laser-sharp shapes, which are repeated in such a way that they allow you to see some patterns (defined, as patterns are, by repetition and regularity); to see what you imagine might be parts of other, larger patterns, infinite or otherwise; and to see something that might very well be chaos itself—a randomized mishmash of renegade shapes and colors, none settling into anything regular or repeated. It is kind of like pi or any other irrational number: unique to itself and impossible to quantify precisely or to translate accurately into another system—numerical or linguistic, measurable or representable.

But even those parts or portions of Hashimoto’s devilishly complex compositions make you feel that they might be arranged in ways that form patterns that you would be able to recognize if only your perceptions were a bit more acute, your cognitive capacities were a bit sharper, or your thinking was a bit more flexible. Or maybe if you could see them from another perspective (or two or eleven). Or if you could get a bit more distance from the immersive, intensely absorptive experience and take in a bird’s-eye—or surveillance drone’s—view of the whole. Experience and reflection dance around one another like nobody’s business, catching you in a whirlwind of synergy that might be impossible to explain but is also impossible to deny. Perception, purged of willfulness, leaves no room for manipulation: Without the chance to micromanage your experience, you’re left face-to-face with the onrush of reality. Neither in control of what comes at you nor overwhelmed by its power, you inhabit the sweet spot between acceptance and exuberance. That experience may not be miraculous, nor is it unique to bicycling, but once you’ve had it there’s no looking back: You’ll want to feel it again, and you’ll go to great lengths to do so.

That kind of mind-blowing beauty is Hashimoto’s bread and butter. What he does in the studio, and what his art does for viewers when it leaves the studio and goes out in the wider world, echoes the experience of riding a bike. You feel, simultaneously, both infinite possibility and instant perfection. Hashimoto serves up that experience in abundance, in works that are made of the simplest materials but that don’t fit into any of the categories we conventionally use to describe works of art, such

as paintings, sculptures, installations, drawings, prints, collages, or assemblages. His low-tech wall works, DIY misfits all the way through, make our eyes and minds move swiftly and fluidly, in hot pursuit of happiness, which happens upon us when we let go of the need to know—and control—what’s going on and instead go with the flow, getting lost in the process and finding ourselves somewhere else. We are not only down the road, but we are transformed; our identities are different from what they were when we began.

My own experience of Hashimoto’s art is tangled up with my love of riding bicycles. And my insights into what he has done as an artist probably would not exist if not for my lifelong passion for bikes and what they do for me. I also believe that what Hashimoto experiences on a bicycle and what he does in the studio are not only intimately linked, but that the former both informs and elucidates the latter. I believe that Hashimoto’s life on a bike and his life in the studio share poetic connections, especially in what he describes as “the immediacy, the pleasure, the delight, [and] the obliteration of the rest of the world for a moment”—consistently, mysteriously, and unlike just about anything else out there. That experience is life-defining. Even better is finding others who share it.

In a sense, Hashimoto’s uncategorizable works are both vehicles and landscapes. Structurally, they are a lot like bicycles. A bicycle is not a singular object, uniform all the way through. It’s an array of parts, clustered together, each designed to do one thing and one thing only: The seat is for sitting; the handlebars are for steering; the pedals are for turning the cranks; the chain is for transferring that energy to the rear wheel; the tires are for inflating and making your ride smoother, more efficient, and more comfortable whenever the rubber hits the road. As Philip Fisher points out in “Hand-Made Space,” chapter eight of Making and Effacing Art: Modern American Art in a Culture of Museums (New York: Oxford University Press, 1991), pp. 227-229, bicycles are unlike preindustrial objects because they are assembled, part by part, and not made—as a carpenter might craft a table, a blacksmith might forge a horseshoe, or a sculptor might carve a stone bust.

Fisher further distinguishes bicycles, noting their differences from other industrial objects, such as cars, trucks, refrigerators, and skyscrapers, whose distinct, constitutive parts are hidden beneath smooth, skin-like wrappings or sleek, minimalist-style surfaces. With bikes, every component is visible. Its form and function are there to see: transparent, as we say today. Plus, because bicycles are

assembled, their parts are interchangeable and easily replaced, whenever upgrades are desired or repairs are needed. This makes bicycles germane to discussions about identity and intersectionality, both literally and metaphorically. For example, no cyclist would think that changing a tube after a puncture or changing a tire after a few thousand miles would mean that they were suddenly riding a different bike. The same is true of replacing the brakes or upgrading the drive train. But at a certain point, things get confusing: Is a bike a different bike when it gets new wheels? A new cockpit? A new gruppo? Most cyclists, but not all, agree that a bike’s frame is integral to its identity but they also agree that the frame isn’t sufficient to entirely determine the bike’s identity. In any case, these questions about identity and the ways it drifts, clusters, and congeals are not unique to machines that are arrays of components. They also arise with other industrial and postindustrial objects, both functional and aesthetic.

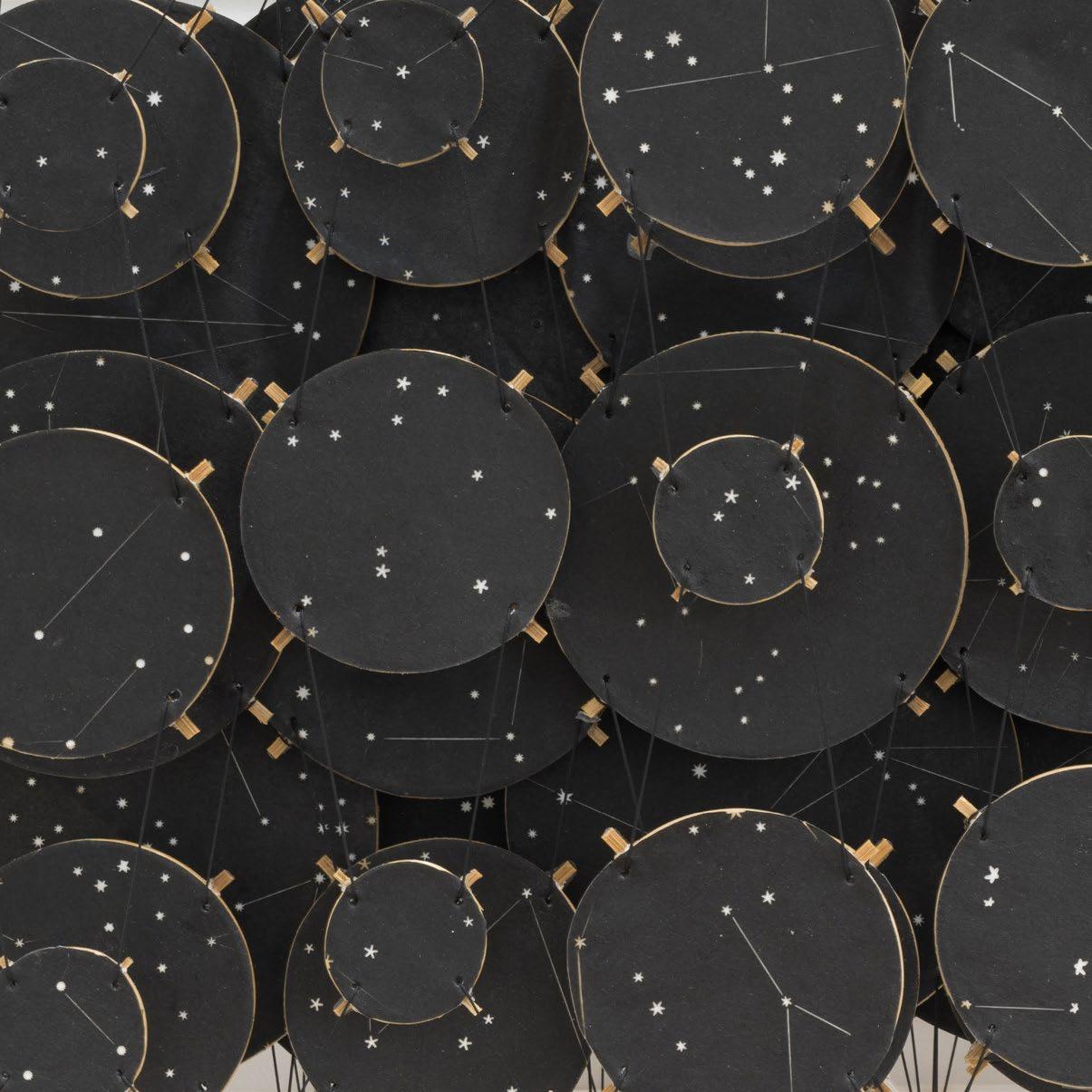

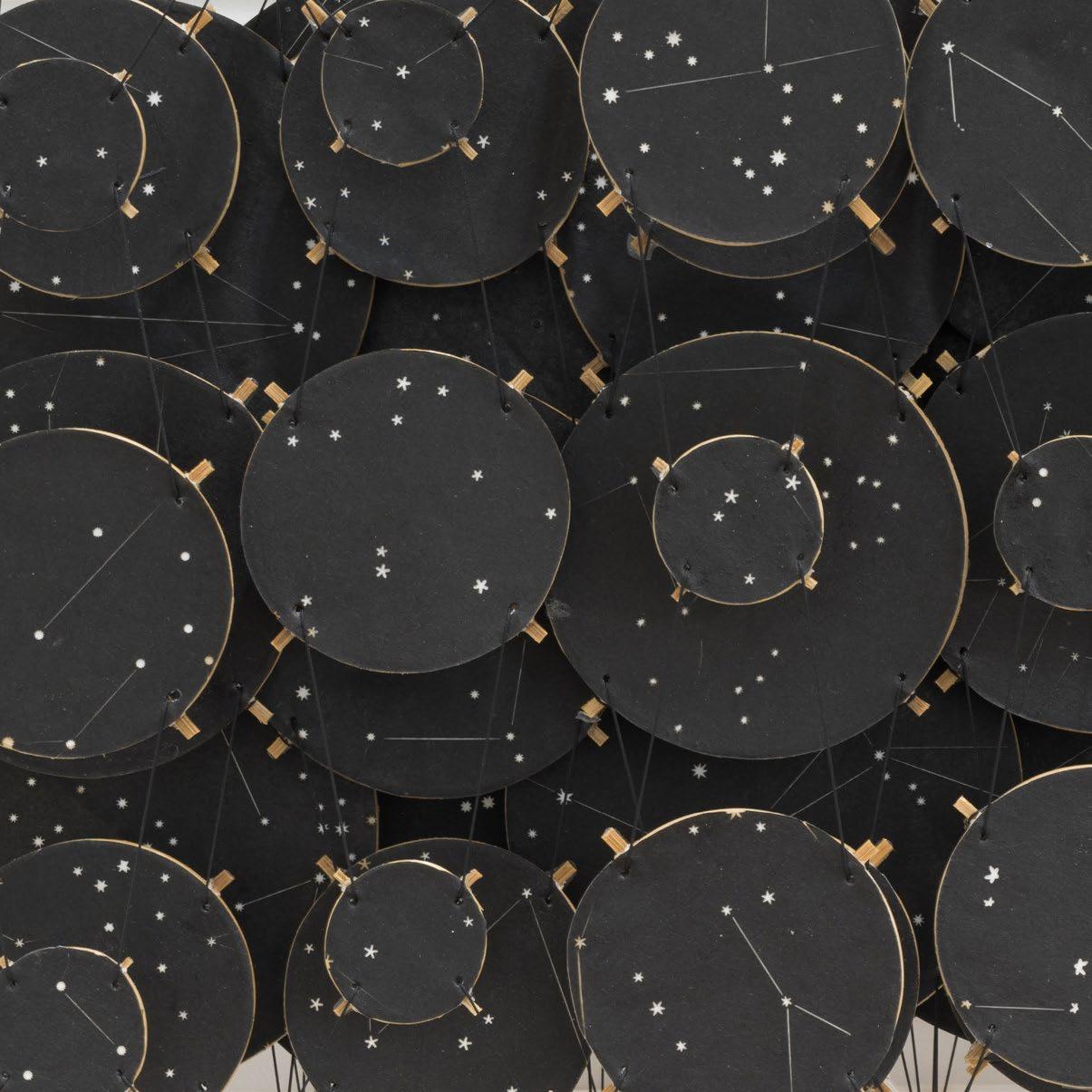

And they play an important role in Hashimoto’s art, which is built on the same principles as bicycles. All of his works, whether arranged in rectangles near a wall, like paintings, or hanging from the ceiling, like airborne installations that might be the descendants of mobiles, wind chimes, and kites, are arrays of components, each of which does one thing and one thing only: the ink delivering color and shape; the Dacron preventing those colors and shapes from fading or bleeding; the paper, cut in circles, functioning as idiosyncratic sketchbook pages; the string securing each piece of paper to its own bamboo frame, and also suspending that frame from other frames, all strung between two rows of stout wood dowels, one at the top and one at the bottom of Hashimoto’s labor-intensive array of insistently analog parts. Nothing is hidden. Everything is visible. And each carefully arranged constellation of components has been designed—and assembled—to drive your eye around the abstract composition.

Hashimoto has set up his works to create situations in which freedom happens by accident. You can’t help but go your own way when you are gazing at any one of his works. That’s because there’s too much going on for Hashimoto to control every relationship, whether between color and shape, size and placement, repetition and interruption, design and surprise. He has shattered and stacked the picture plane, transforming a person’s ordinarily unified field of vision into a stimulating expanse of eye-popping, pixel-style tondos: Each is a world unto itself—a member of a group of similarly tinted and configured components. Each is also a part of an even more expansive pattern, some of whose members may belong to the smaller group while others do not.

One of the best things about Hashimoto’s complex works is that they invite you to arrange, in your mind’s eye, different parts of his pieces into different wholes, and then to rearrange various parts of those wholes into other parts of other wholes. Schools of fish come to mind, swimming in unison as they whip through other schools of fish, not one single fish bumping into another. Hashimoto’s works also recall the improvised dances that take place on crowded sidewalks in urban centers all over the world: those unscripted moments when every individual manages, as if magically, to tap into the intuited rhythm and to flow around everyone else, fluidly and beautifully, without missing a step. That poetry of motion is even better—and more exciting—with bicycles. I experienced it in China, riding around the sprawling city of Tianjin amid throngs of other cyclists, our collective motion given form by the traffic lights and a myriad of motor vehicles, whose pace and power exceeded ours and added to the exhilarating beauty of the massive, ever-changing dance.

Hashimoto’s works are similarly charged landscapes. Whether you choose to zoom in on a particularly delicious detail, to follow a path or a pattern across a larger field of components, or to take everything in from a distance, surveying the whole as if it were an expanse of enlarged pixels, his art puts your eyes in motion. Your mind follows. As imaginative bike rides, his works take you through overpasses, tunnels, cloverleafs, exits, on-ramps, back alleys, side roads, and paths rarely traveled— everything, it seems, except one-way streets, cul-de-sacs, and dead ends. And the incessant left-toright, back-and-forth, and up-and-down movement his works generate is multiplied and intensified by the layers in which he has arranged the components of his works. You can’t see everything at the same time. It is always possible to peek around any part of any layer and see more. The point is that no single perspective lets you see all, much less know all. Contingency is built in. The same goes for the need to look again—and again, and again. Hashimoto describes his works as “jumbled portraits of my brain,” saying that “they are meaningful but not depictive—suggestive rather than narrative nor representational. They are about staying in motion, about not getting stuck.” For Hashimoto, repetition is generative: “I think of repetition,” he says, “as the physical component of thinking.” Doing something over again doesn’t mean that it comes out the same way each time. Even when you ride the same bike route, every ride is different.

Hashimoto’s love of bicycles goes back to his childhood, when he’d whoosh out of the driveway of his family’s home and head off on his own. As an adult, he bought an 8:30 a.m., a rare, aluminum-framed

bike designed and built by the legendary frame-builder Dario Pegoretti, of Verona, Italy, that was named after the time Pegoretti liked to start work every day. Frames, like bicycles, are arrays of components. There are always tubes, brackets, and stays. There are sometimes lugs. Although all bikes have forks, there is no consensus about whether forks are part of the frame. In any case, artisans like Pegoretti are referred to as frame-builders, not frame-makers, because of the industrial nature of what they do: They assemble diverse, single-purpose components into functional objects.

A few years after Hashimoto cracked the head tube of his 8:30 a.m., he flew to Verona to install an exhibition at Hélène de Franchis’s renowned gallery, Studio la Città. The preparator, Doriano Saturnia, met him at the airport, and during their two-hour drive to the gallery the two got to talking about bikes. Hashimoto learned that a frame builder had moved his shop into a building behind the gallery. Then he learned that the frame-builder was Pegoretti. Later that week, Hashimoto asked de Franchis to introduce him to Pegoretti. The two met, hit it off, and fell to talking about Hashimoto’s broken frame. Pegoretti suggested that he would build a frame and that, when he was finished, Hashimoto should come back and paint it. Pegoretti then upped the stakes, shifting from aluminum to stainless steel. Hashimoto came back to paint the frame. He worked with Pegoretti every day for a week, starting with coffee at 8 a.m. and continuing until the end of each day. Their collaboration initiated a friendship that lasted until Pegoretti’s sudden death in 2017, while they were working on another bike. The first one they produced turned out to be a breathtakingly beautiful masterpiece: Whether leaning against a wall or flying down the road, it looks magnificent, like a landscape within a landscape or a fleeting image of the earth and sky whooshing by. Their one-ofa-kind Responsorium has been exhibited around the world, and it now occupies pride of place in Hashimoto’s New York studio.

Riding a bike is as close to flight as an earthbound human can get. After all, when one is on a moving bike, the only point of contact with terra firma consists of a few square centimeters,

half in front and half in back, where the rubber meets the road. The physical sensation of graceful weightlessness that this delivers is angelic, perhaps divine. That same sense of soaring is configured and conveyed by Hashimoto’s works, which simultaneously tip their hats to the artist’s dad, Irvin Hashimoto, who flew tiny, homemade kites out his fourth-floor office window when he was finishing up his dissertation and teaching writing as a first-year faculty member at Idaho State University, in Pocatello, Idaho. To me, there’s something wonderful about flying a tiny kite out of an office window. It’s similar to taking a cigarette break on a fire-escape—a relaxing interlude for someone too busy to leave the building, find an open space, unspool some thread, and take a proper break. And kites, when aloft, connect the people holding the other end of the string to something big and invisible— the world and the wind. Without wind, whether gusting or steady, a kite goes nowhere. But when a kite takes off, it comes alive, tugging you upward, sometimes slightly, sometimes strongly, and always with a sense of joyous uplift. The extension of one’s self that follows is refreshing. It can also be transformative in the same way that riding a bicycle can be. And the fact that Hashimoto’s dad made and flew miniature kites sweetens the story. The elder Hashimoto’s pint-size kites, more like toys or dollhouse-size playthings than the kites used in competitions, emphasize the innocence at the heart of what he was up to: taking a break from business as usual to find a moment of grace, right outside his window.

His son brings similar impulses to his art and finds similar satisfactions in it. But unlike his dad, who was flying kites privately for personal pleasure, the younger Hashimoto flies kites publicly for viewers of all stripes to enjoy. To emphasize the public nature of his endeavor, Hashimoto flies hundreds of kites simultaneously, laying them out in neat rows and columns, and then stacking those rectangular arrays atop additional arrays. It doesn’t take a great leap to imagine that the sky is a traffic jam of kites, all waiting for your eyes to swoop and glide through them. The abundance of kites Hashimoto presents in a single, wall-mounted work does not compel viewers to dig like archaeologists beneath their beautiful, brightly colored, and elaborately patterned surfaces to get to the truth buried there. On the contrary, Hashimoto’s neatly arranged cornucopias of mini-kites are all about getting us going and keeping us in motion: joyously and freely, unburdened by the past or the future, simply and perfectly content with the fullness of the present.

None of us is so clueless as to think that history doesn’t figure into this or that the future doesn’t matter. It’s simply that the presence of the moments that made up the past and will make up the future do not diminish the power and the pleasure of the present. You can only go on one bike ride at a time. Likewise, you can only look at one Hashimoto—sometimes only one part of one Hashimoto—at a time. Knowing that others are out there doesn’t take anything away from your experience of the one you’re looking at. What’s in front of you is sufficient, precisely because its generous array of components has been brought together by Hashimoto in such a way that you want—even need—to rearrange those components in your mind’s eye, discovering patterns within patterns, worlds within worlds, thoughts within thoughts, and so on and so forth, with no end in sight. That’s just about as close to infinity as any human can get—with or without a bicycle.

David Pagel is an art critic, curator, and professor of art theory and history at Claremont Graduate University. His reviews and essays have appeared in the Los Angeles Times, Brooklyn Rail, Artforum, Art Issues., Flash Art, and Art in America. Recent publications include Broad Reminders: John Sonsini + David Pagel (Radius Books), Jim Shaw (Lund Humphries), and Talking Beauty: A Conversation Between Joseph Raffael and David Pagel about Art, Love, Death, and Creativity (Zero+). He is currently working on Moment’s Noticed: The Life and Art of Bret Price, to be published later this year. Pagel is a selftaught diorama builder, an avid cyclist, and a seven-time winner of the California Triple Crown.

No, No My Friends, We Will Not, 2025

72 x 60 x 8 1/4 inches

183 x 152 x 21 cm

72 x 60 x 8 1/4 inches

183 x 152 x 21 cm

72 x 60 x 8 1/4 inches

183 x 152 x 21 cm

Some truths are just not worth having, 2025

60 x 48 x 8 1/4 inches

152 x 122 x 21 cm

The bittersweet fall into actuality, 2025

60 x 48 x 8 1/4 inches

152 x 122 x 21 cm

What!? - I? Who?, 2025

60 x 48 x 8 1/4 inches

152 x 122 x 21 cm

Even if it was all a lie, 2025

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

I think I’m already forgetting, 2025

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

It was all possible until it wasn’t, 2025

paper, bamboo, wood, and Dacron

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

Maybe going back isn’t the right idea, 2025

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

The plot of one’s own destruction, 2025

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

problem with bubbles, 2025

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

There are other places, 2025

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

This exact language, 2025

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

Would it work? Not likely., 2025

32 x 26 x 8 1/4 inches

81 x 66 x 21 cm

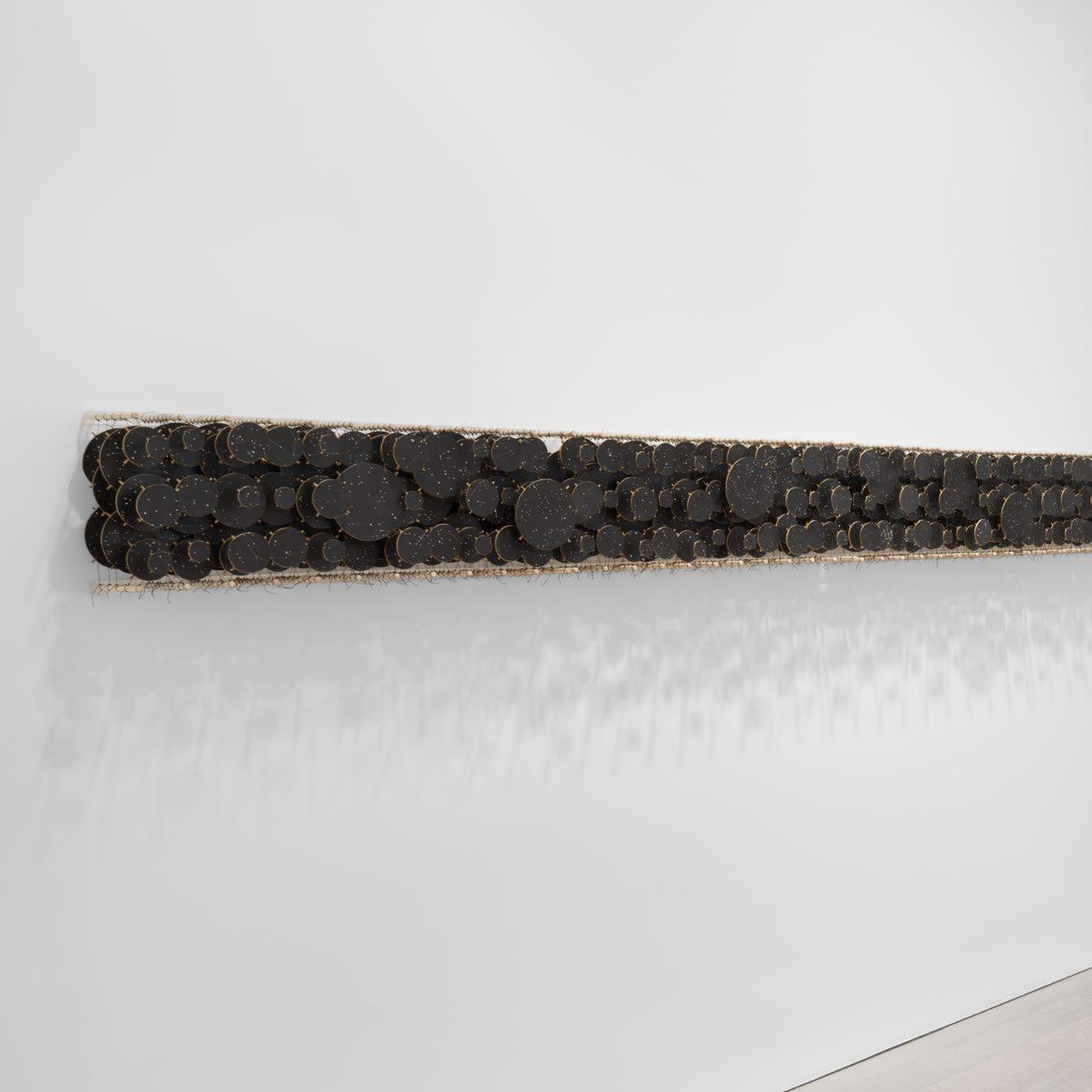

Steam engine time, 2025

13 x 281 x 7 inches

33 x 714 x 18 cm

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

30 October – 20 December 2025

Miles McEnery Gallery 515 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2025 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2025 David Pagel

Photo Credit: p. 9: Photo by Michele Alberto Sereni

Associate Director Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by

Christopher Burke Studios, New York, NY Dan Bradica, New York, NY

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-5666-1

Cover: What!? - I? Who?, (detail), 2025

Endsheets: Steam engine time, (detail), 2025