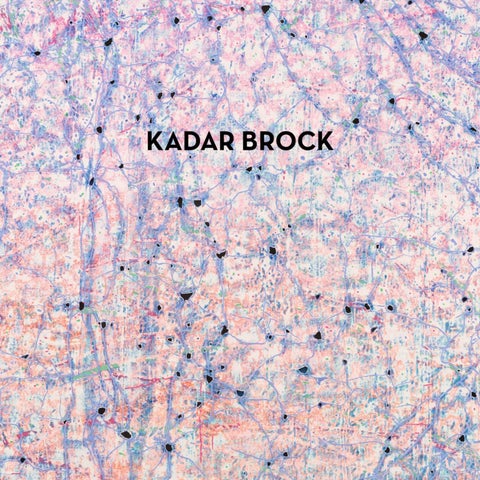

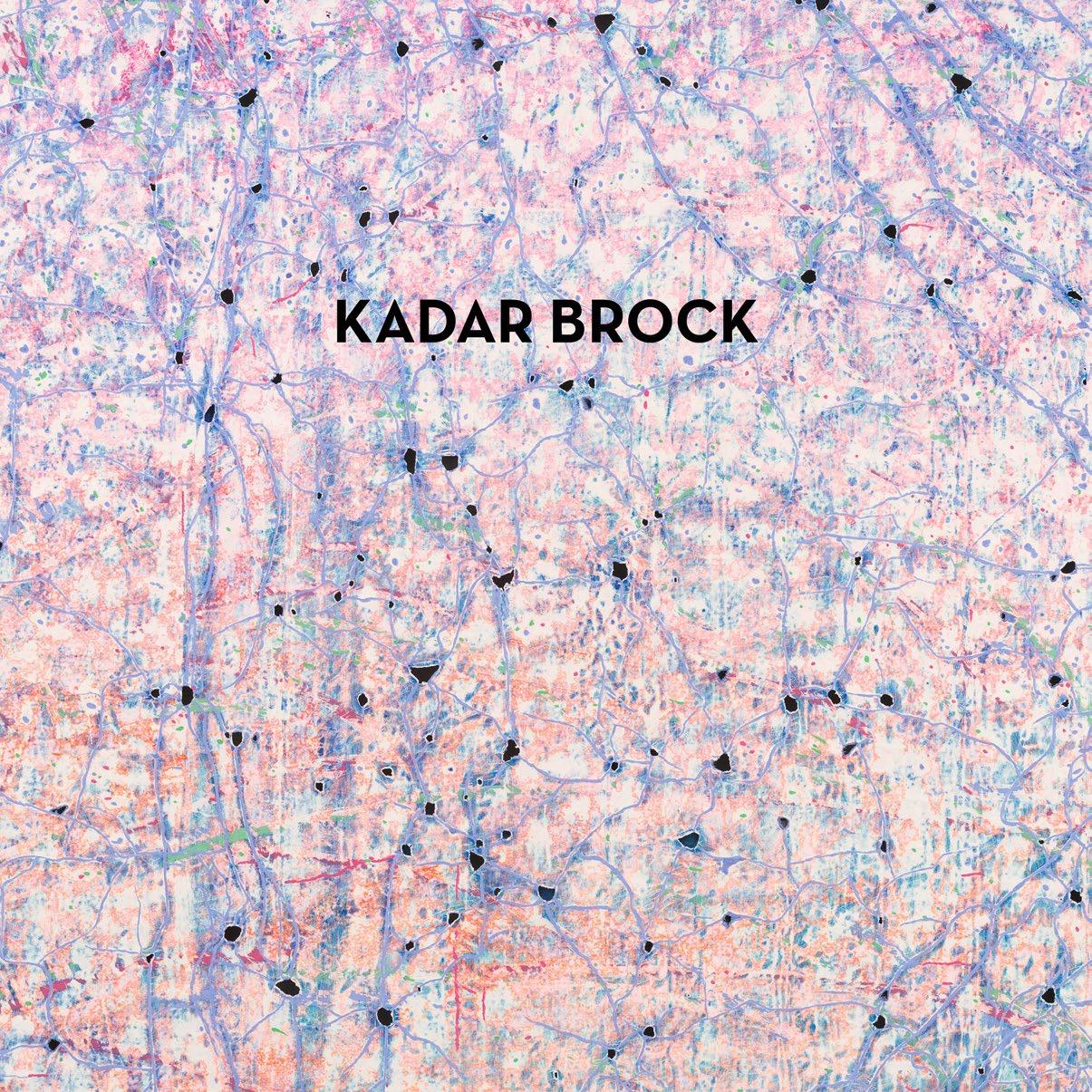

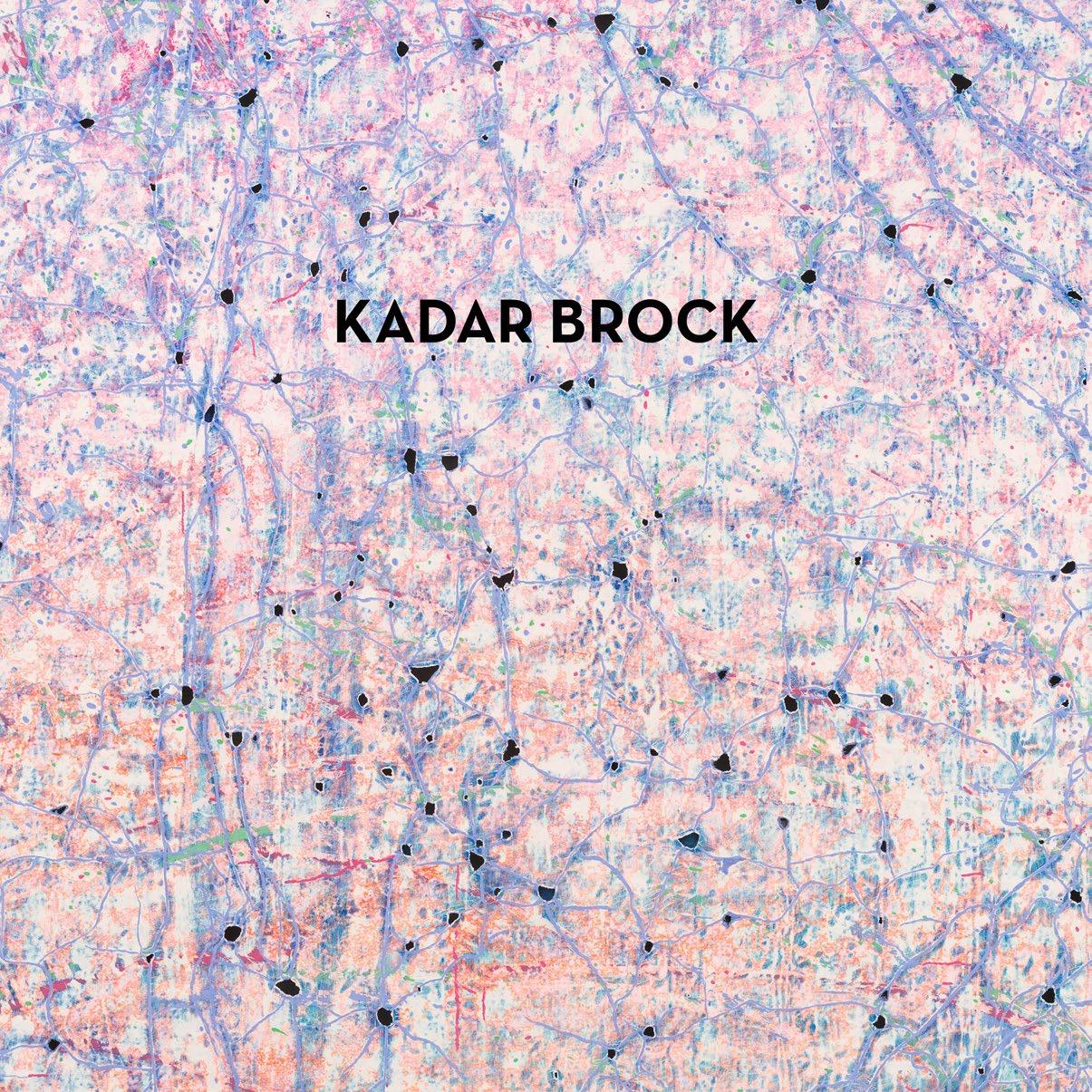

KADAR BROCK

KADAR BROCK AND THE RUINS OF PAINTING

Alex Bacon

If, as critics and historians periodically proclaim, painting “died” in the last century and a half, what is left of the venerable medium? Kadar Brock’s work suggests that perhaps what remains is a ruin, with paint on canvas now legible only as the remains of a once monumental expressive form. For more than a decade, Brock has pursued a complex, process-driven approach to making works that engage with both the history and future of painting. He embraces painting’s most familiar and unfamiliar forms alike: from the familiarity of a canvas, to the lack of familiarity with that same canvas’s offcuts.

Brock’s dehierarchized embrace of all elements of a studio practice, placing the elements in dialogue with one another, suggests that perhaps hauntology is at play, to use the philosopher Jacques Derrida’s term for an as-yet-unrealized possible future. The cultural theorist Mark Fisher pinpoints hauntology as emerging from postmodernism and neoliberalism’s evacuation of the resources needed to realize the future. Thus, the utopian aims of the historical avant-garde continue to lie in reserve. They can be visualized only through abstractions and erasures, like the promises of the spiritualist cults of the twentieth century, which dovetailed with those artistic aspirations. In his work, Brock takes on the legacy of both modernist painting and religious cults, seeing links between their different, but equally millenarian, desires for a better future—desires that have been frustrated since the 1960s by political and cultural developments.

Over the last few years, Brock has been engaged with material related to the nonprofit religious corporation the Movement of Spiritual Inner Awareness (MSIA). Brock’s parents were members of this organization, which many consider to be a cult. Brock has been exploring his upbringing

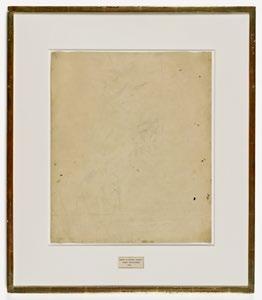

Robert Rauschenberg, Erased de Kooning Drawing, 1953, Traces of drawing media on paper with label and gilded frame, 25 1/4 x 21 3/4 x 1/2 inches (64.14 x 55.25 x 1.27 cm). San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, CA, Purchase through a gift of Phyllis C. Wattis.

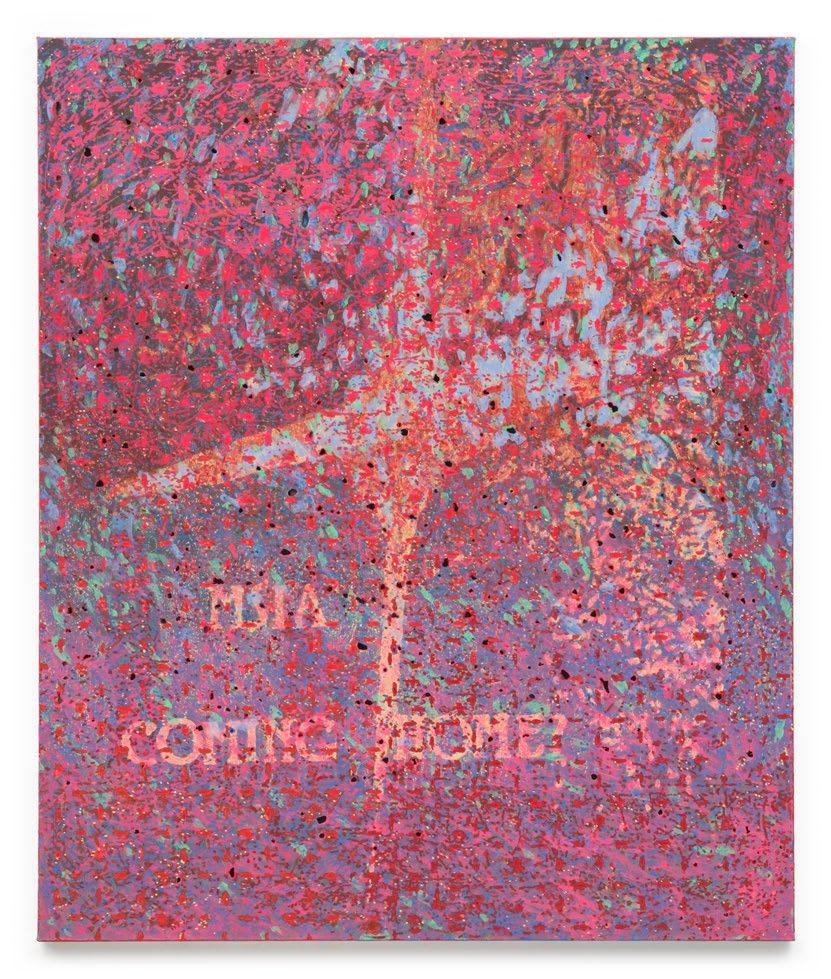

by researching materials produced by the group, such as newsletters and pamphlets. He has also been interviewing experts on cults in general, like David C. Lane, and people knowledgeable about MSIA specifically. Those research materials have appeared in some of the zines that Brock has made in conjunction with his exhibitions, and his recent paintings have often begun as painterly explorations of this imagery. Most strikingly, one of the paintings in this exhibition is haunted by the ghostly apparition of the cover of a MSIA pamphlet. The group’s name and an eerie evocation of the light that supposedly leads the subject out of limited forms of thinking occupy prominent positions in the center and lower left sections of the painting, respectively.

When Brock makes a painting, he first addresses the medium’s past. He starts by composing conventionally in oil paint. His composition may be abstract, figurative, or something in-between. Then Brock scrapes down the surface with a razor blade, window scraper, or palette scraper, removing most of his work’s original referents and content, as he physically deconstructs what he has painted. This is a materialist approach evocative of painting’s putative future. As Robert Rauschenberg’s famous Erased de Kooning Drawing announced in 1953, no erasure is ever definitive, and what is retained is perhaps more important than what is removed.

Brock’s painterly “ruin” draws out the work’s subconscious, as it were, suggesting an abstract complex of emotions that arise as we traverse the optically activated fields of color that Brock compresses when he sands a painting in its final stages. Sanding also gives rise to tactile topographies of ridges and ravines, while scraping between layers opens up the surface with gouge and puncture marks. As such, optical experiences of color and form are augmented by the simple workman-like gestures of scraping and sanding, which replace, and can even be understood to be violently redacting, what we typically understand as the “labor” of painting—the building up of form and narrative meaning. So, two different types of labor, which in our culture are attached to two very different value systems, come into play. Both can be understood as examples of the kinds of evacuated futures discussed by the likes of Fisher in regard to hauntology. Both modernist painting and spiritual cults are associated with charismatic men who suggest paths to transcend the mundane everyday through a dedicated focus on certain mental operations used to process aesthetic or spiritual experiences. With both art and cults, we implicitly rely on these patriarchs to guide us toward “enlightened” states.

This context, which links modernist painting with spiritual cults, suggests two analogues for the hauntology of Brock’s painterly ruins. Brock effectively connects the dots between them as two modes of experience and belief that feed a need for ritual and meaning in a world largely emptied of belief. Brock’s archaeological surfaces allow us to sense the power these forms once held, even as he has emptied them by effacing the very referents he conjures—only to redact and build atop them, making something new even while retaining echoes of the past.

Brock has always been drawn to the palimpsests of urban environments like New York City. He is interested in the ways that different people layer, elaborate, and occlude each other’s marks as they act out in, and occupy, public spaces. There is, for example, the way that public workers cover graffiti tags. But they are never quite able to match colors and thus are unable to fully block out the marks they’re trying to erase. The result is a collaboration of sorts. The rise of graffiti art in the last fifty years represents just one way that art has found fertile ground in the spontaneous

modes of expression that accrue in public urban spaces. It is one very visible example of how painting has become fully spatialized, dispersed, and integrated into the public sphere. Traditional forms of painting—i.e., pigment on a rectilinear support—have been perceived as being under attack as the field of possibility has expanded. They stubbornly persist, nonetheless.

With time, Brock has added (literal) layers and complexities to his process. Using oil paint, which was initially, at least in part, a practical way to reduce the toxicity of his materials, has resulted in more of a trace being left after the scraping and sanding. Further, rather than simply revealing the painting’s “subconscious,” Brock now responds to it by going back into the work after sanding it, painting in and along fractures and fissures in the work’s surface and allowing the unpredictable idiosyncrasies his process reveals in the work to direct how it arrives at its final state. That is itself a palimpsest, not unlike the graffitied streets that surround the artist’s studio.

The finished paintings have become more formal, with Brock’s process activating a color-driven optical play that a fellow artist has cannily termed “glitch pointillism.” This clever neologism sutures the familiar errors and breakdowns in contemporary digital technology to the technologically motivated painting techniques of the late nineteenth-century avant-garde. Both isolate the pixel or dot as their basic unit of imagistic information, and these constituent atoms become visible when the smooth reading of the content they are supposed to serve breaks down.

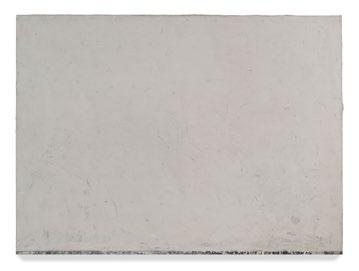

Brock has, in essence, brought his paintings (and the traditional function of painting as a device for the delivery of content) to the precipice of a breakdown of meaning. At this stage, the materiality of the work effectively overrides the image content, reversing the traditional hierarchy of viewing. Similarly, it confuses the received notion of materialist-oriented painting practices, such as those of Robert Ryman or Brice Marden, that emerged in the 1960s and emphasized a painting’s physicality. Instead, Brock’s works hover in a provocative in-between space, suggesting and alluding to content but ultimately withholding it. One could say that this is another example of hauntology. Brock implicitly aligns painting with digital devices as platforms for the consumption

Brice Marden, Return I, 1964–65, Oil on canvas, 50 1/4 x 68 1/4 inches (127.6 x 173.4 cm).

The Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY, Gift of Kathy and Richard S. Fuld, Jr.

of images, so we cannot help but think of the way that traditionally materialist painting practices like Ryman’s and Marden’s advocated a slowing down of vision, canceling images in favor of setting up contemplative situations where the viewer considers the presence of the work before them. By alluding to the material conditions of both painting and imagery, Brock’s works point to the impossibility of avoiding image consumption in our time. Brock refuses to either fully resist or fully feed into these interconnected impulses.

Another development in Brock’s recent work has been the use of textiles made by weaving together offcuts produced during his painting process. These include strips of canvas, paint rags, sanding discs, and plastic carrier bags. Brock will lay his unstretched paintings over these crude weavings and run a sander over it. The resulting application of pressure creates a textured matrix that closes the feedback loop of his studio’s ecology, returning what would otherwise be waste or detritus into his production process. Brock goes back over this fractured web with his paint brush in a reparative fashion that is suggestive of the Japanese practice of kintsugi, whereby ceramics are repaired with beautiful lacquer finishes that celebrate rather than hide the cracks and scars of use.

Brock’s textiles take on a further life when he uses them to cover the handmade furniture that he often produces for his exhibitions. This furniture is a way for him to bring the ecology of the

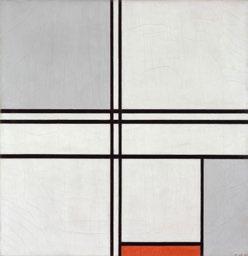

Piet Mondrian, Composition (No. 1) Gray-Red, 1935, Oil on canvas, 22 5/8 x 21 7/8 inches (57.5 x 55.6 cm). Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL, Gift of Mrs. Gilbert W. Chapman.

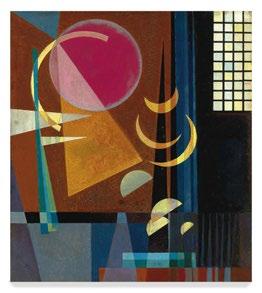

Wassily Kandinsky, Scharf-Ruhig (Sharp-Quiet), 1927, Oil on cardboard, 16 3/4 x 14 3/4 inches (42.5 x 37.5 cm). Private Collection.

studio into the exhibition space, as well as to underscore, and make possible, a slowed-down contemplation of the installed works. The deliberate obfuscation of the content encourages a measured pace of looking, with the works operating as repositories of information, but not necessarily ones that readily disclose their contents. This sort of archaeological reading resonates with Brock’s own acts of archiving and researching when he assembles and processes the materials that serve as the source material for his paintings.

Giving the work a specific content, not to mention something as charged as MSIA (and all that it brings up around religion, spirituality, and cult-like behavior) deepens the paintings’ subconscious. Just as, with time, colors have brightened and forms have started to surface, however fleetingly, the references to MSIA have given a bit more meat to Brock’s compositions. His work no longer refers only to painting itself. It helps as well that the MSIA references are personal to the artist. He has long circulated the ecology of the studio through his work and in exhibitions, by displaying multiple elements of his process, and reincorporating elements of it, such as the cast-off textiles that he uses to cover exhibition furniture. It is a more recent development, however, for Brock to introduce himself into this network. To do so is to complete the circle in a way,

by refusing to imagine that the artist is outside of the work. This gesture can also be read in the context of the art critic Isabelle Graw’s discussion of painting’s indelible link to the artist who made it. This vitiating force seems to animate even the most minimal works; we are unable to avoid imagining that a given painting channels something of the life force of its maker.

Graw’s argument about the integral nature of artists to their “products”—paintings—means that it makes sense for Brock to position himself through his research into MSIA as part of the network of relations embodied in the painting. But it also points outward, not only to others touched by that group (as well as by religion and cults in general) but also to the role that spirituality has long played in the production and consumption of art. Abstraction was initiated in the early twentieth century as, in large part, a spiritual exploration of “pure” form that is analogous to the meditative possibilities that art finds in geometry. Piet Mondrian, Wassily Kandinsky, and Hilma af Klint, for example, were adherents of the Theosophical Society, which was founded by the writer and mystic Helena Blavatsky. Brock’s evenhanded engagement with MSIA and the undeniably beautiful formal attributes of his paintings allow us to indulge in the spiritual possibilities of abstraction while retaining some criticality about the ends to which it might be put if it falls into the wrong hands. Brock’s painterly hauntology remains critical of a past embodied in things like the new age cults of the 1970s and ’80s and the masculinist abstract painting of the 1960s, even as it yearns for a better future—one that is an alternative to the techno utopias burgeoning in Silicon Valley.

Alex Bacon is currently a Visiting Scholar at Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland, New Zealand.

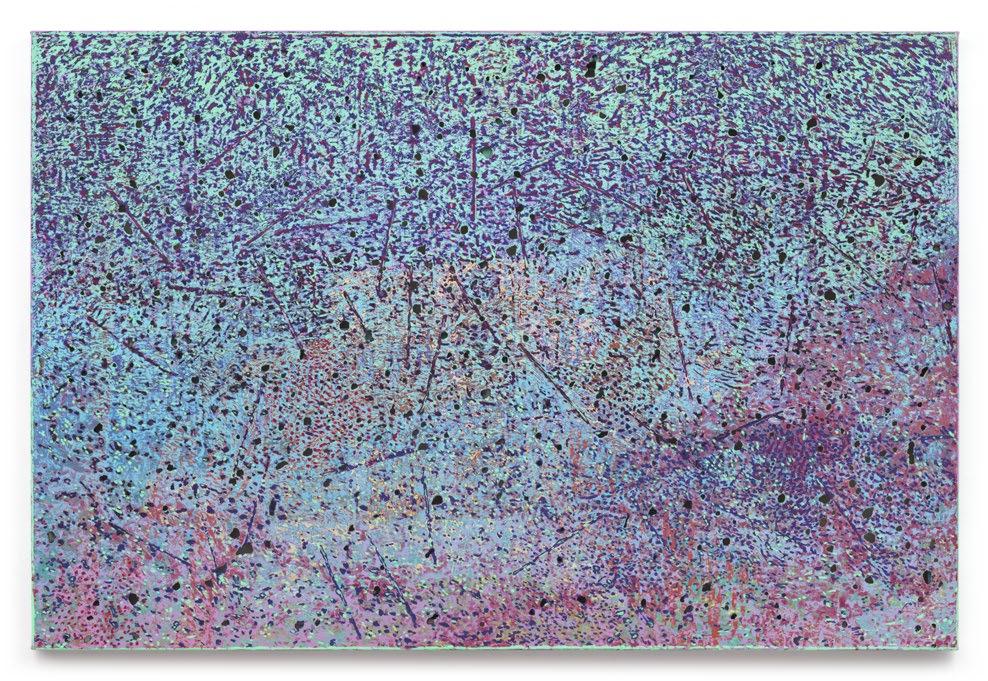

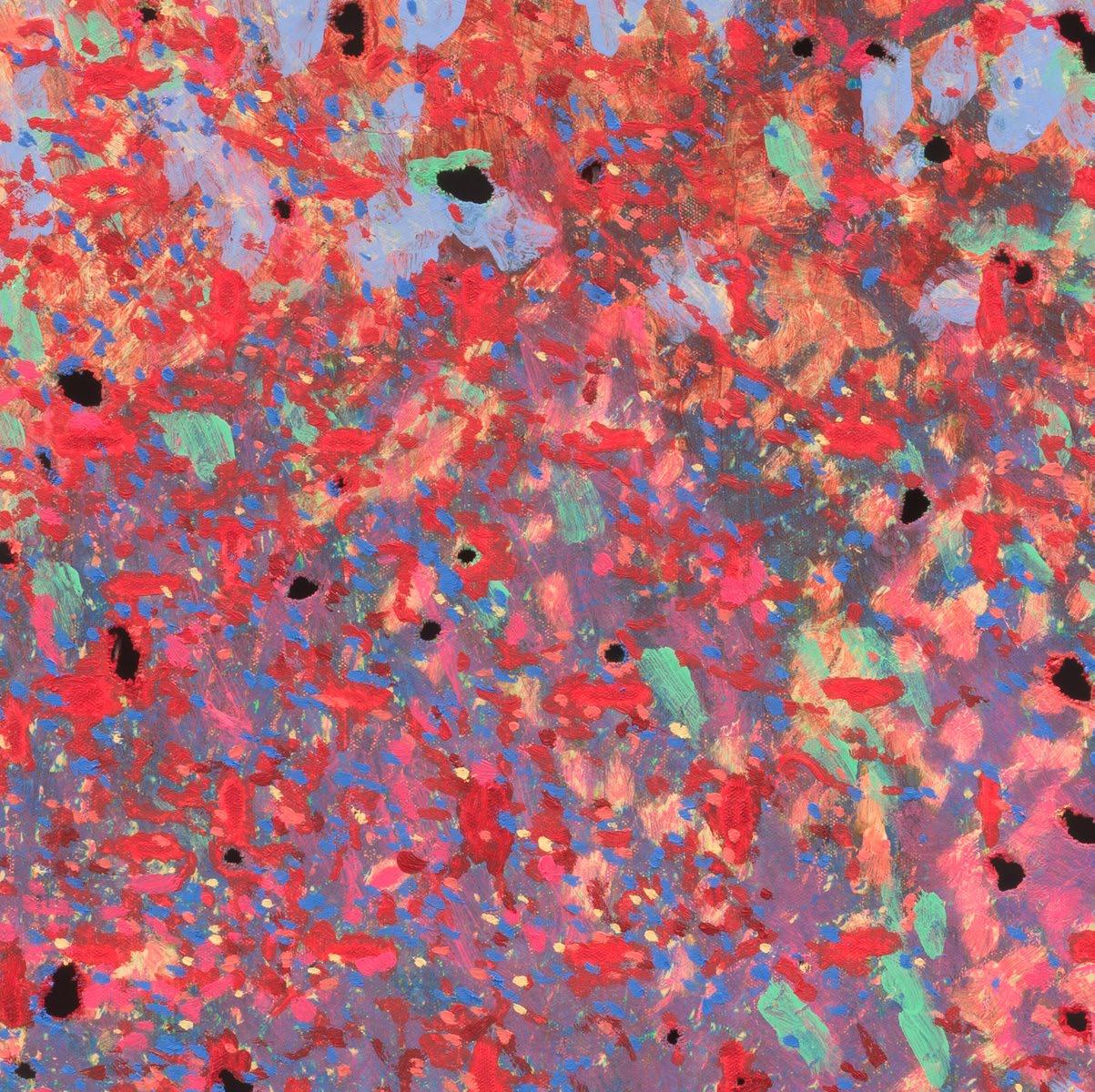

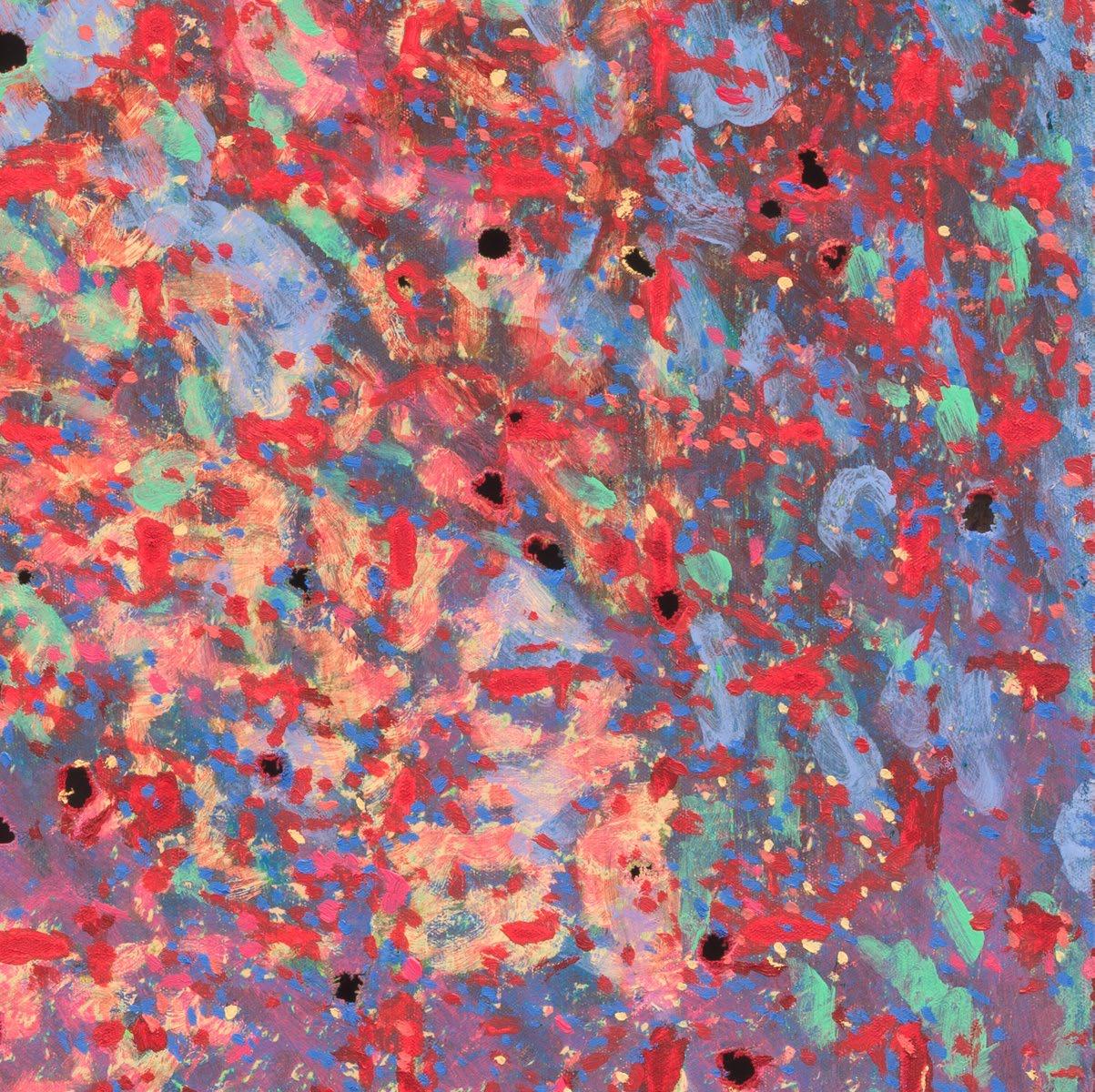

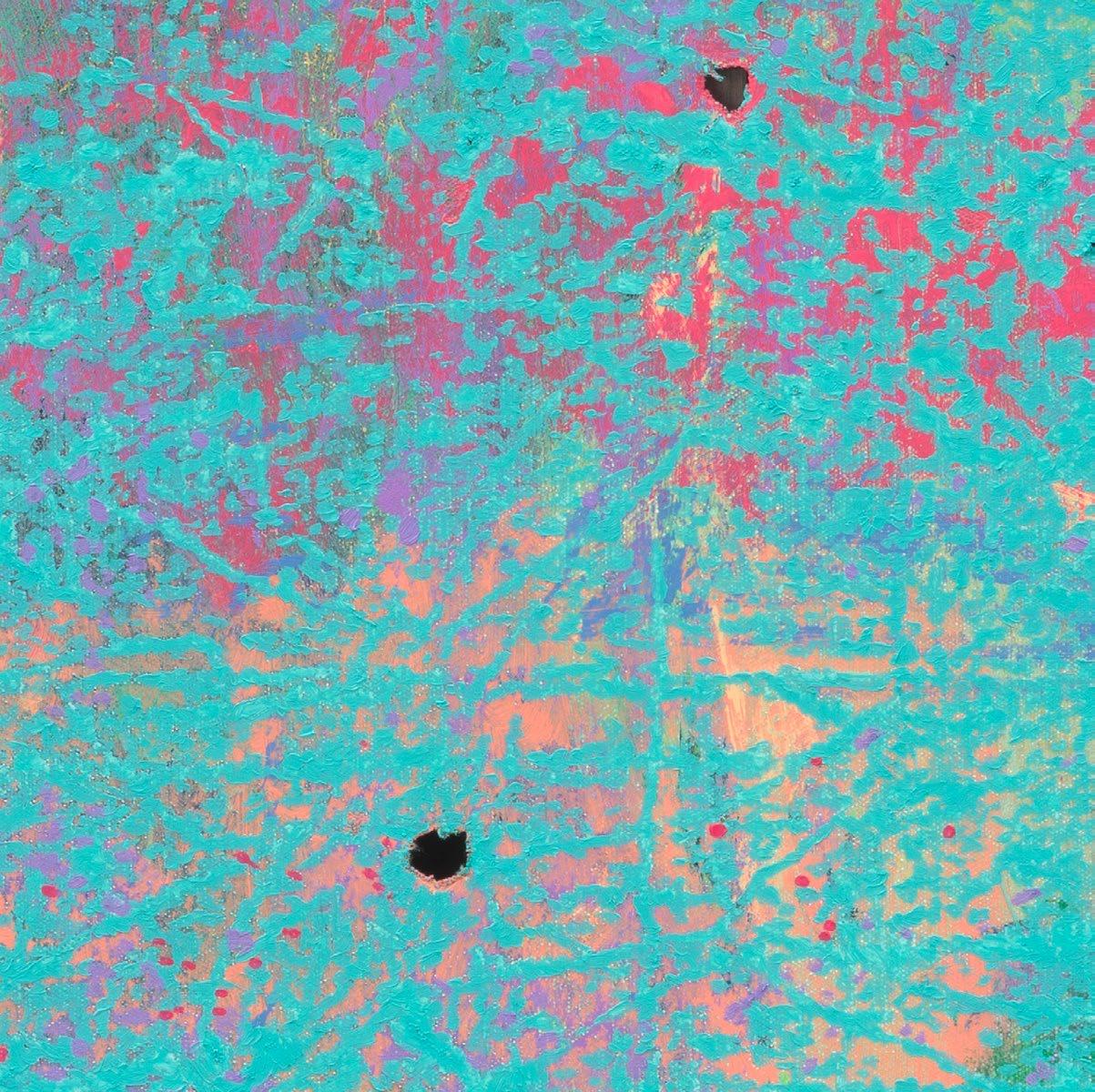

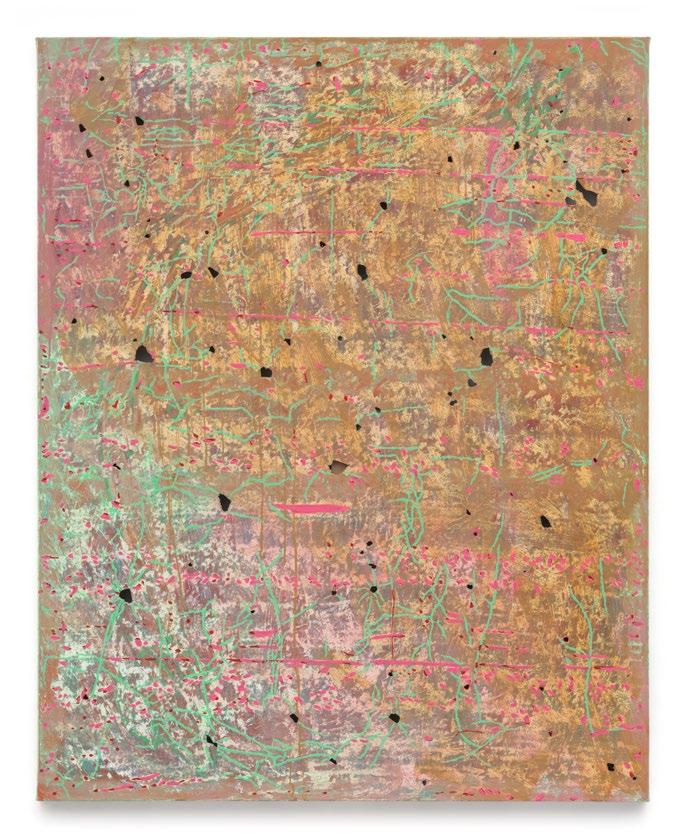

rains, prana is the movement’s ashram, rosemead high, the mutual store, 2020 - 2024

Oil on canvas

48 x 72 inches

122 x 183 cm

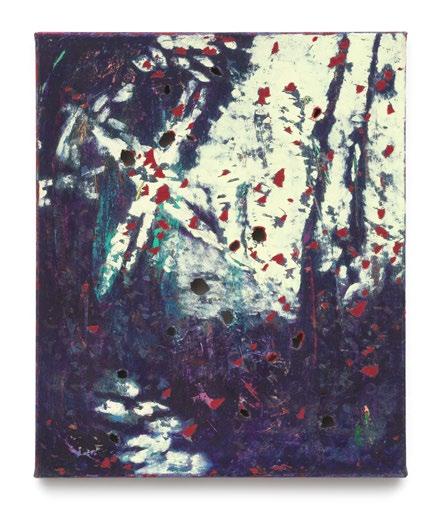

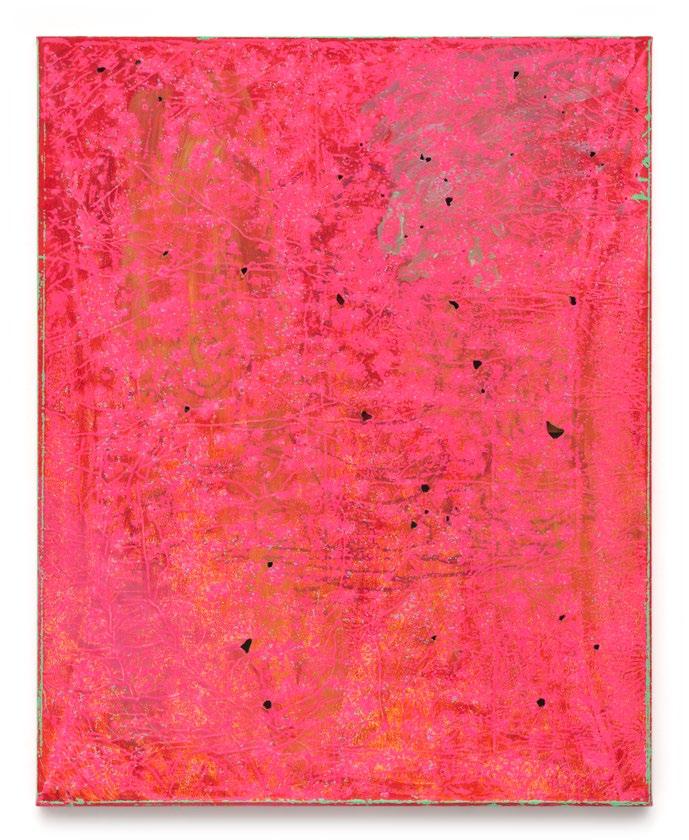

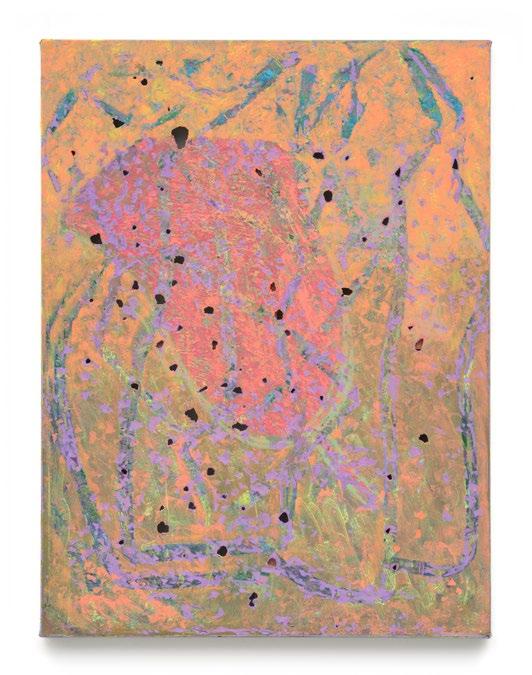

take a break, the movement is the beginning, 2023 - 2024

24 x 20 inches

61 x 51 cm

Oil on canvas

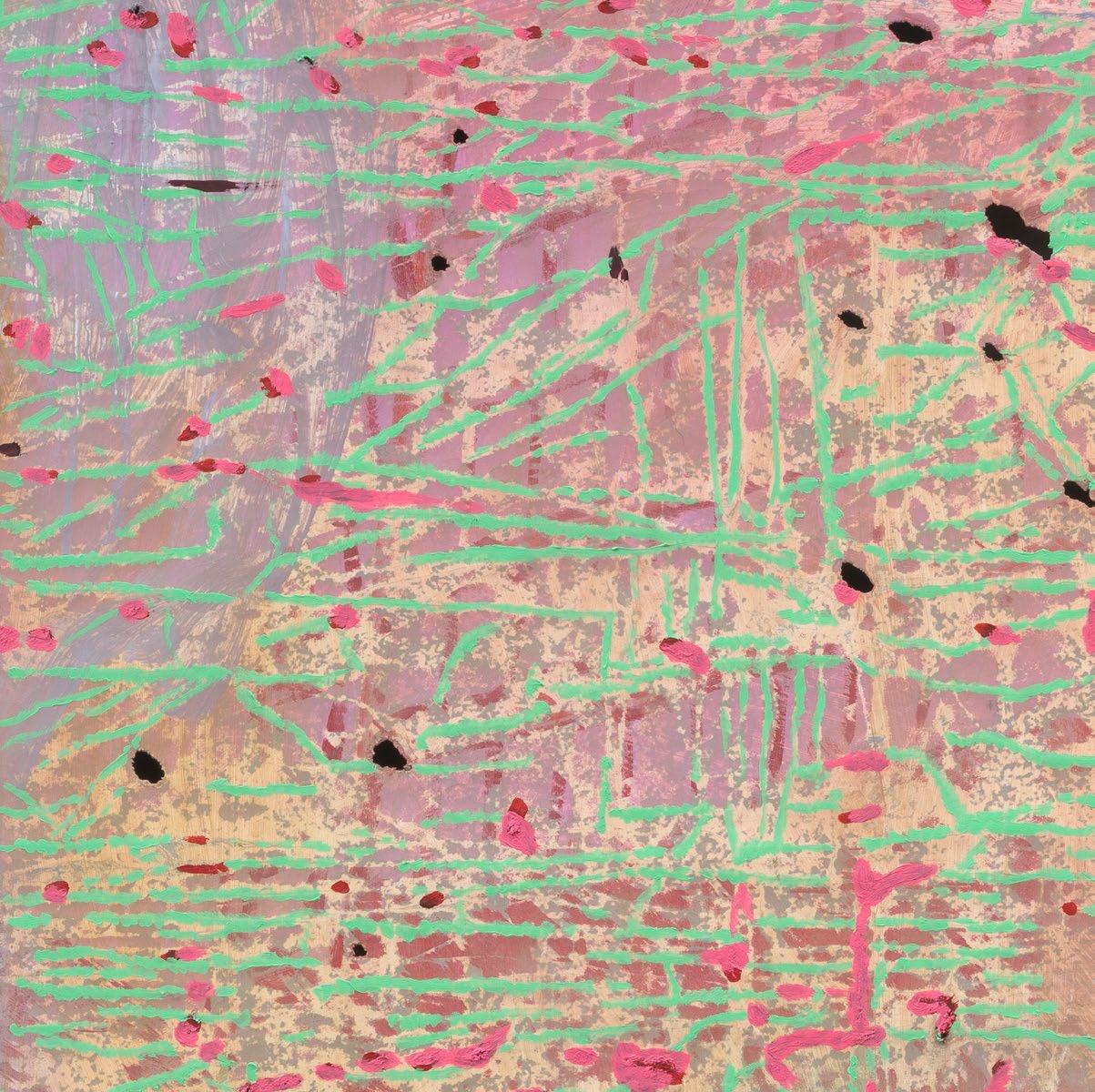

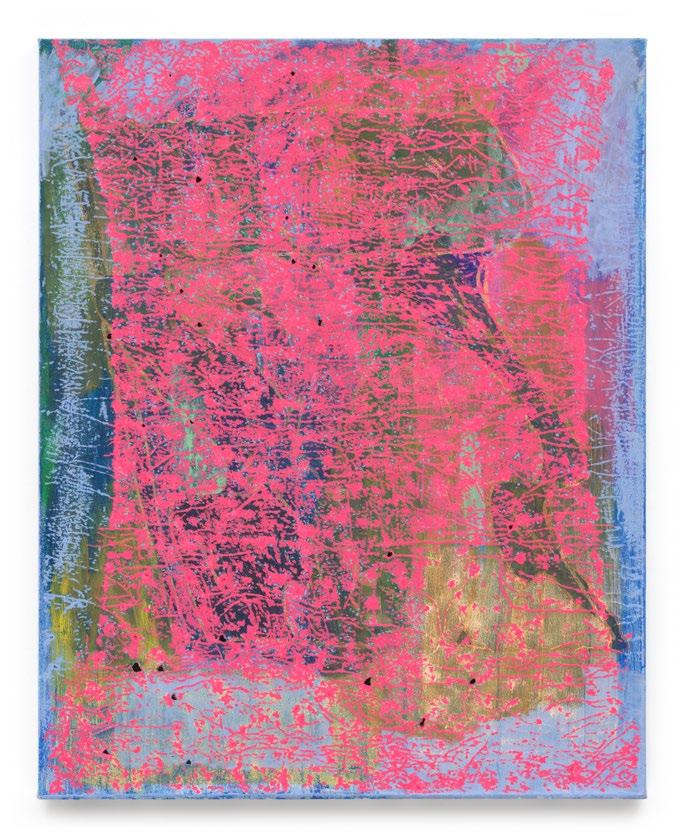

coming home, looking for a way home, 2023 - 2025

72 x 60 inches

183 x 152 cm

Oil on canvas

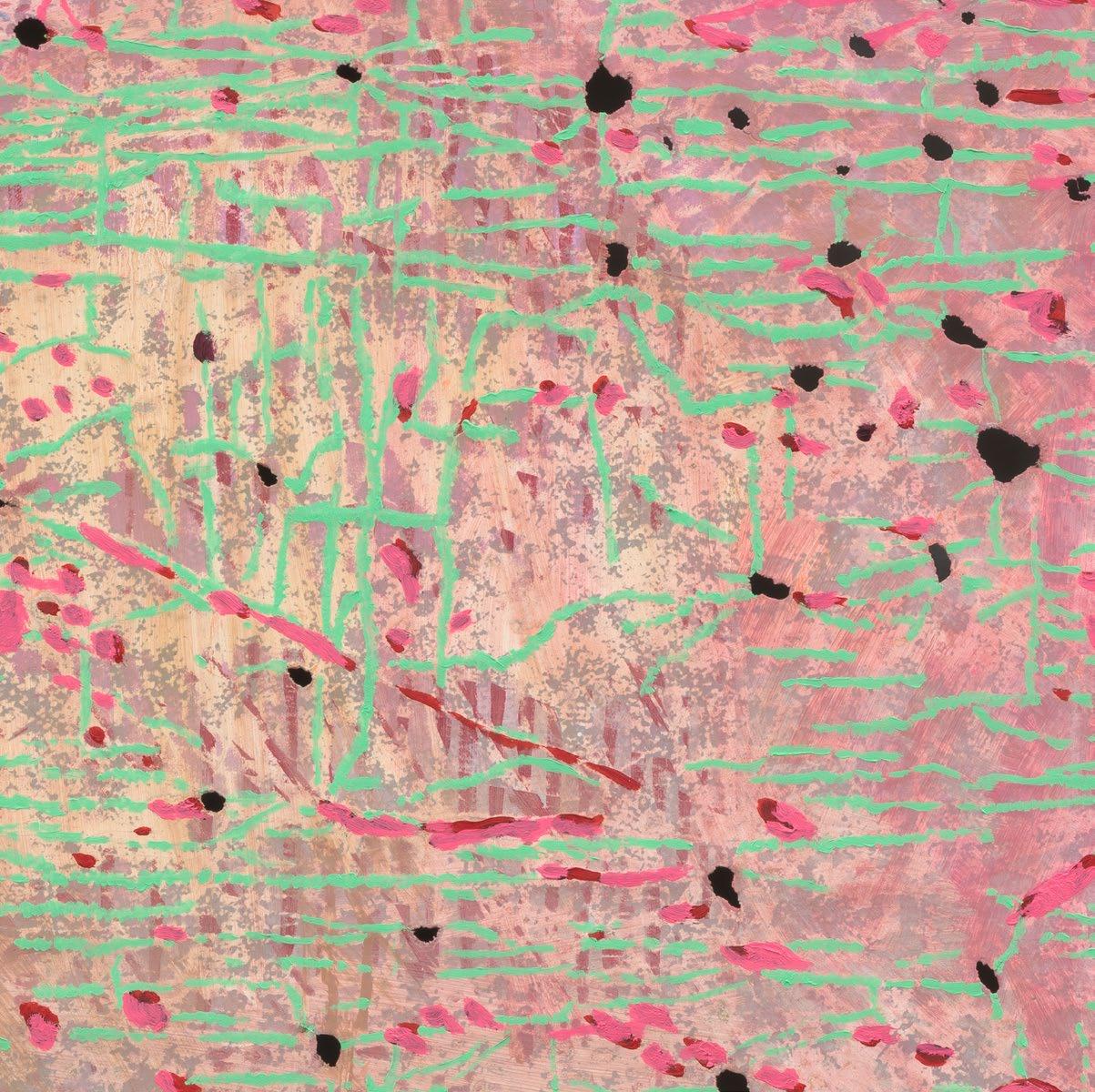

fantastic dreams, have your own day, 2023 - 2025

72 x 60 inches

183 x 152 cm

Oil on canvas

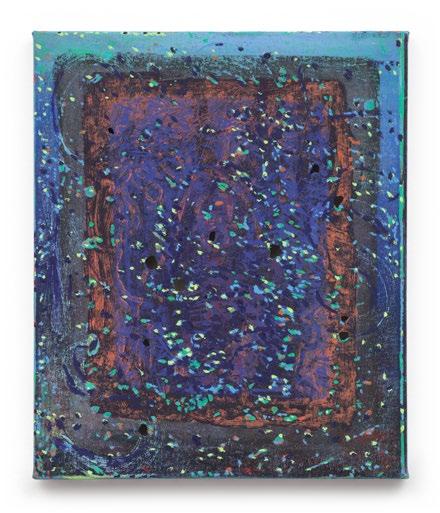

in a special way, three mes, openness, 2020 - 2025

24 x 20 inches

61 x 51 cm

Oil on canvas

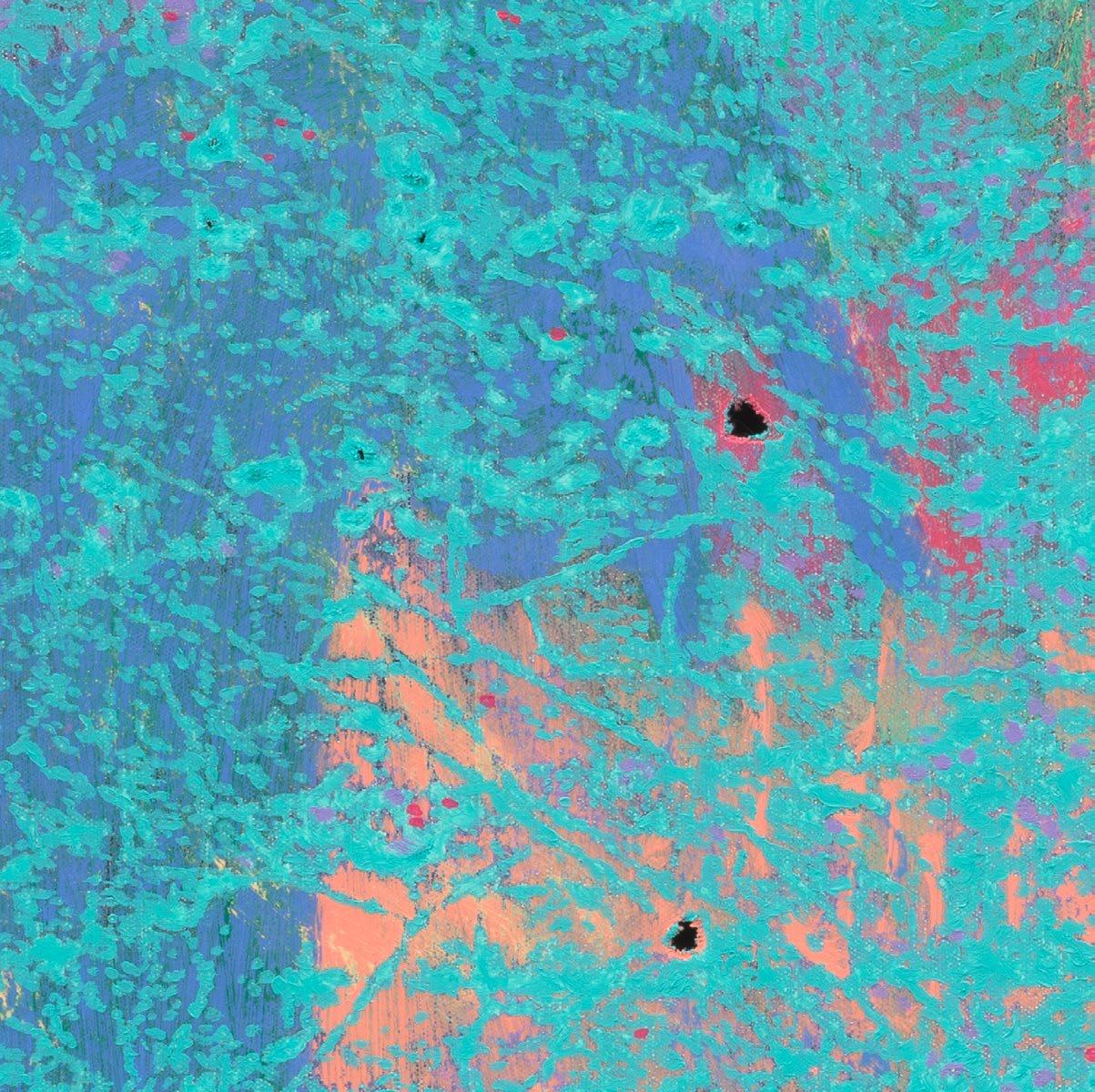

initiation site, the you that is me, the mine at rains, utah, 2020 – 2025

Acrylic, house paint, oil, and spray paint on canvas

60 x 48 inches

152 x 122 cm

it is here now, get back near it, soul flight, 2021 - 2025

house paint, oil, and spray paint on canvas

60 x 48 inches

152 x 122 cm

Acrylic,

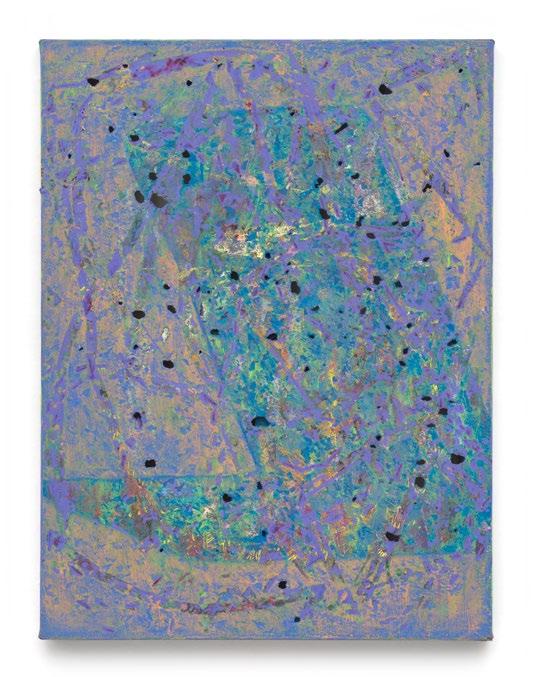

separate selves, 2023 - 2025

60 x 48 inches

152 x 122 cm

Oil on canvas

something you’re not, 2023 - 2025

60 x 48 inches

152 x 122 cm

Oil on canvas

went underground, the heavenly two, mana physics, 2021 - 2025

Oil on canvas

40 x 30 inches

102 x 76 cm

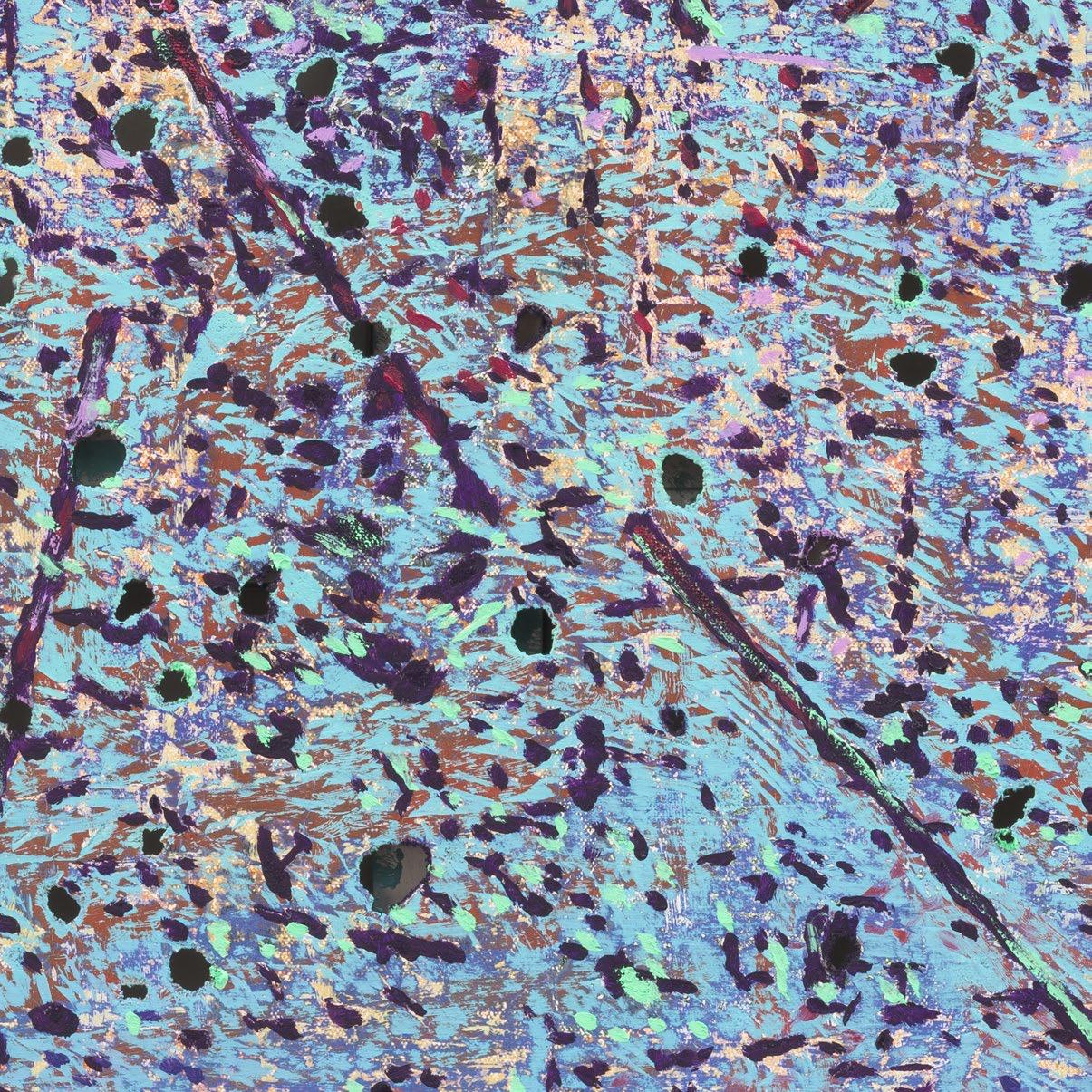

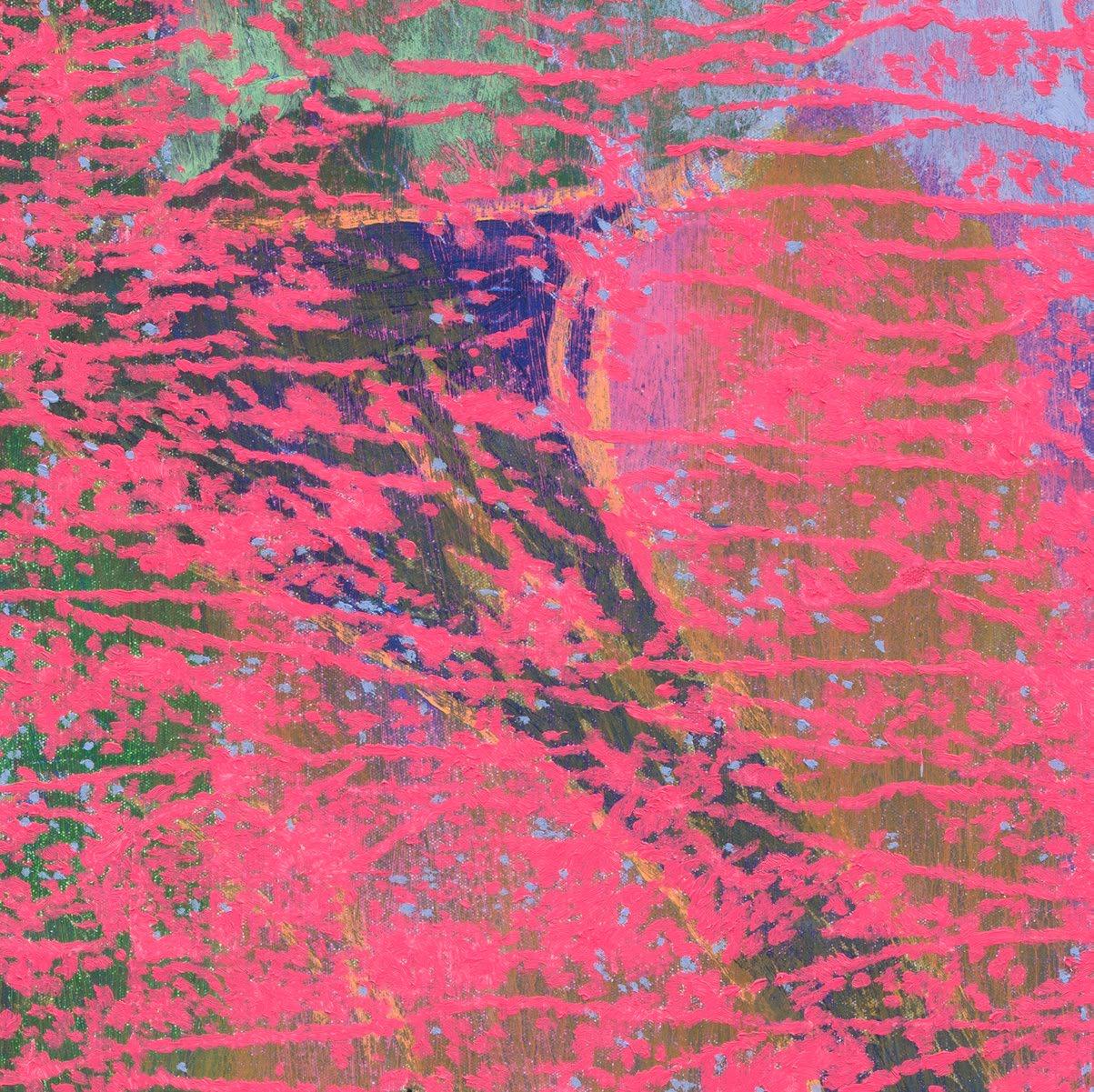

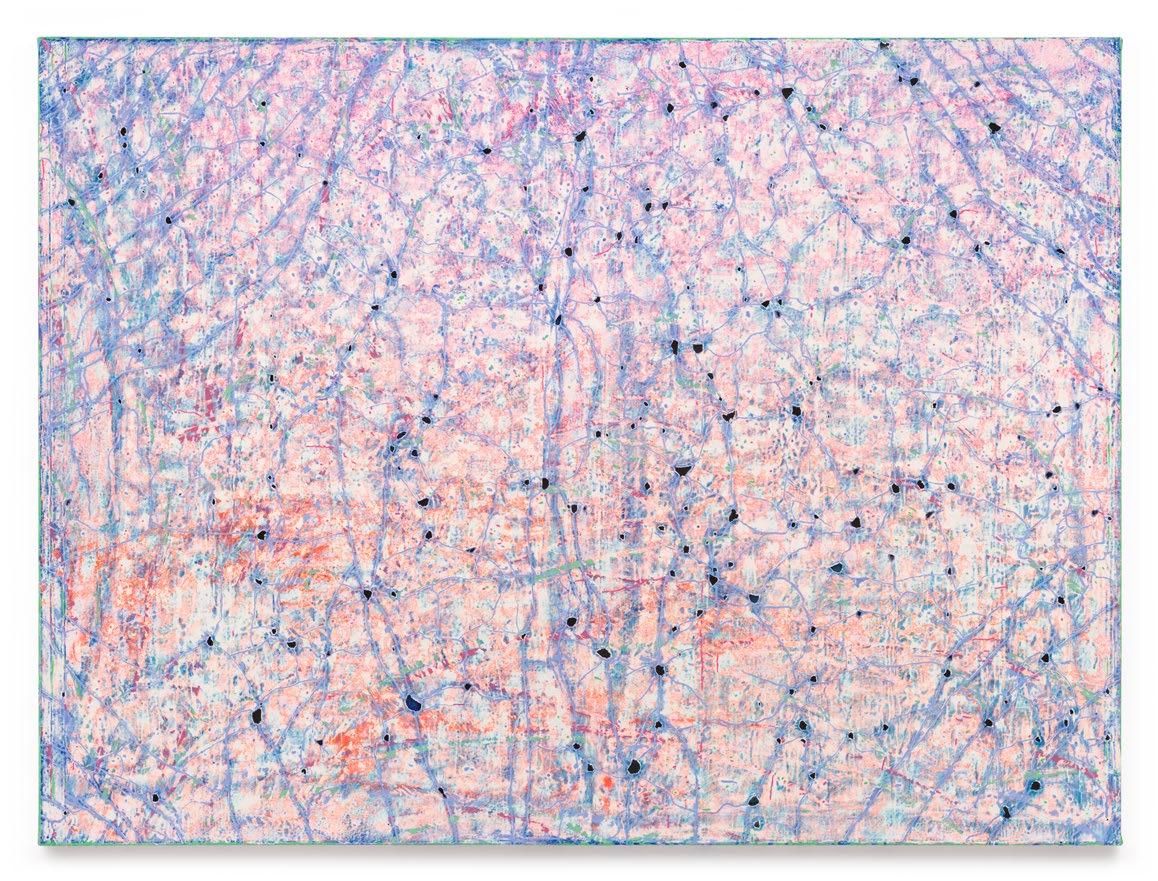

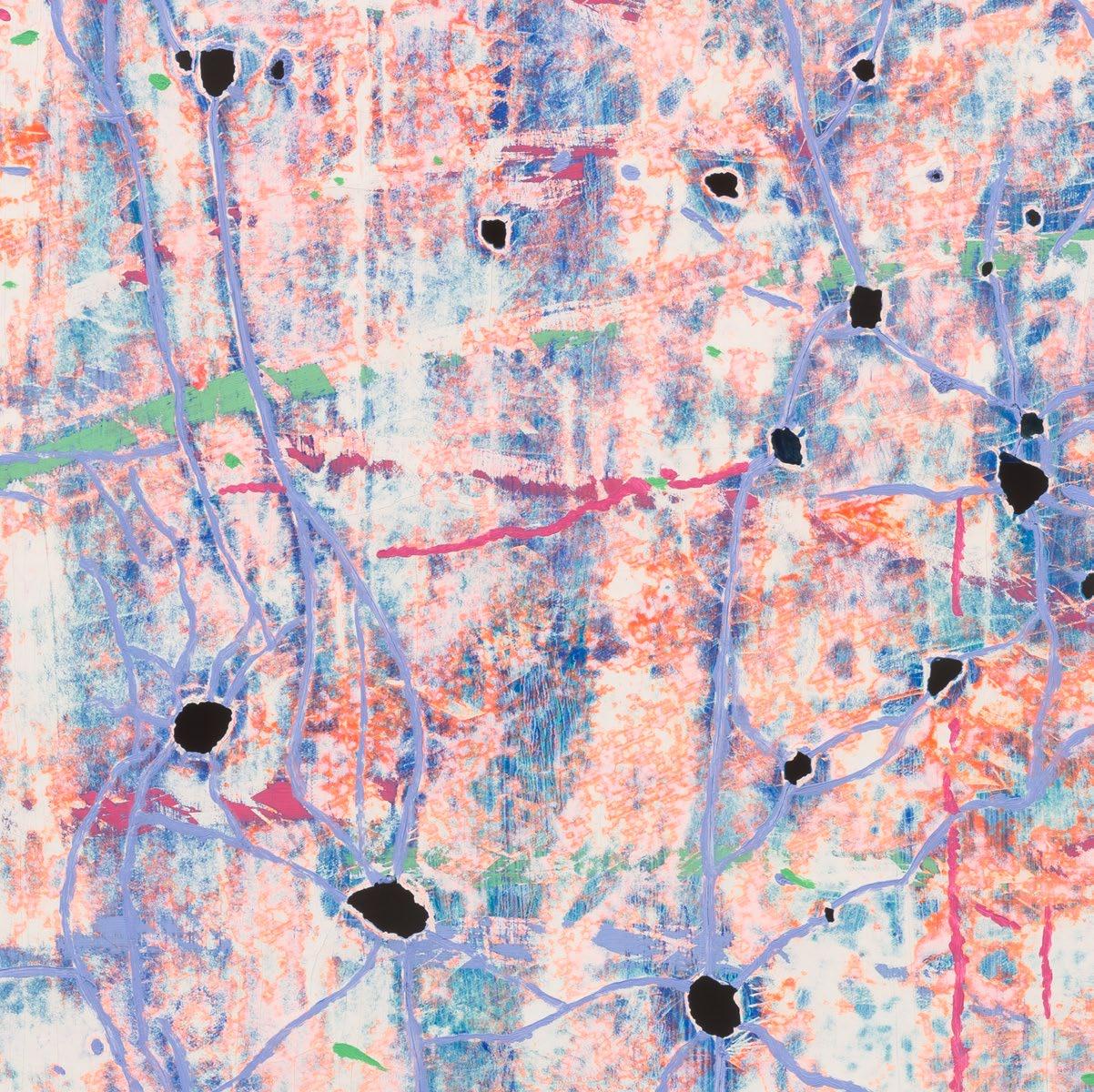

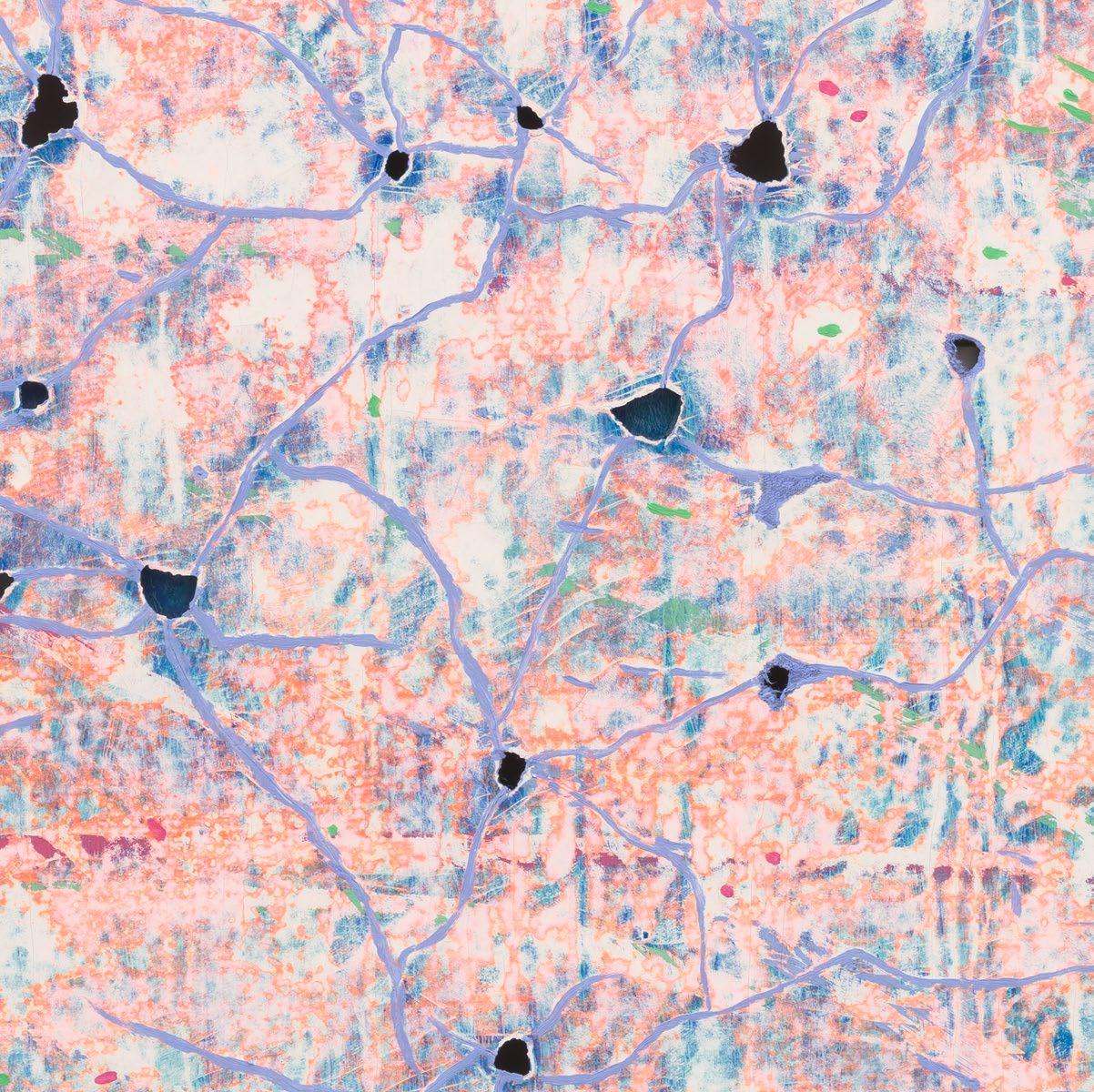

you can all love, 2017 - 2025

72 x 96 inches

183 x 244 cm

Acrylic, flashe, house paint, oil, and spray paint on canvas

you can always imagine, where we all began, light column, 2021 - 2025

Oil on canvas

40 x 30 inches

102 x 76 cm

Published on the occasion of the exhibition

KADAR BROCK

COMING HOME

4 September – 25 October 2025

Miles McEnery Gallery 515 West 22nd Street New York NY 10011

tel +1 212 445 0051 www.milesmcenery.com

Publication © 2025 Miles McEnery Gallery

All rights reserved

Essay © 2025 Alex Bacon

Photo Credits

p. 4: © 2025 Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / Photography by Ben Blackwell

p. 7: © 2025 Estate of Brice Marden / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

p. 8 (left): © 2025 The Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago, IL

p. 8 (right): © 2025 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York / HIP / Art Resource, New York, NY

Associate Director Julia Schlank, New York, NY

Photography by Dan Bradica, New York, NY

JSP Art Photography

Catalogue layout by Allison Leung

ISBN: 979-8-3507-5368-4

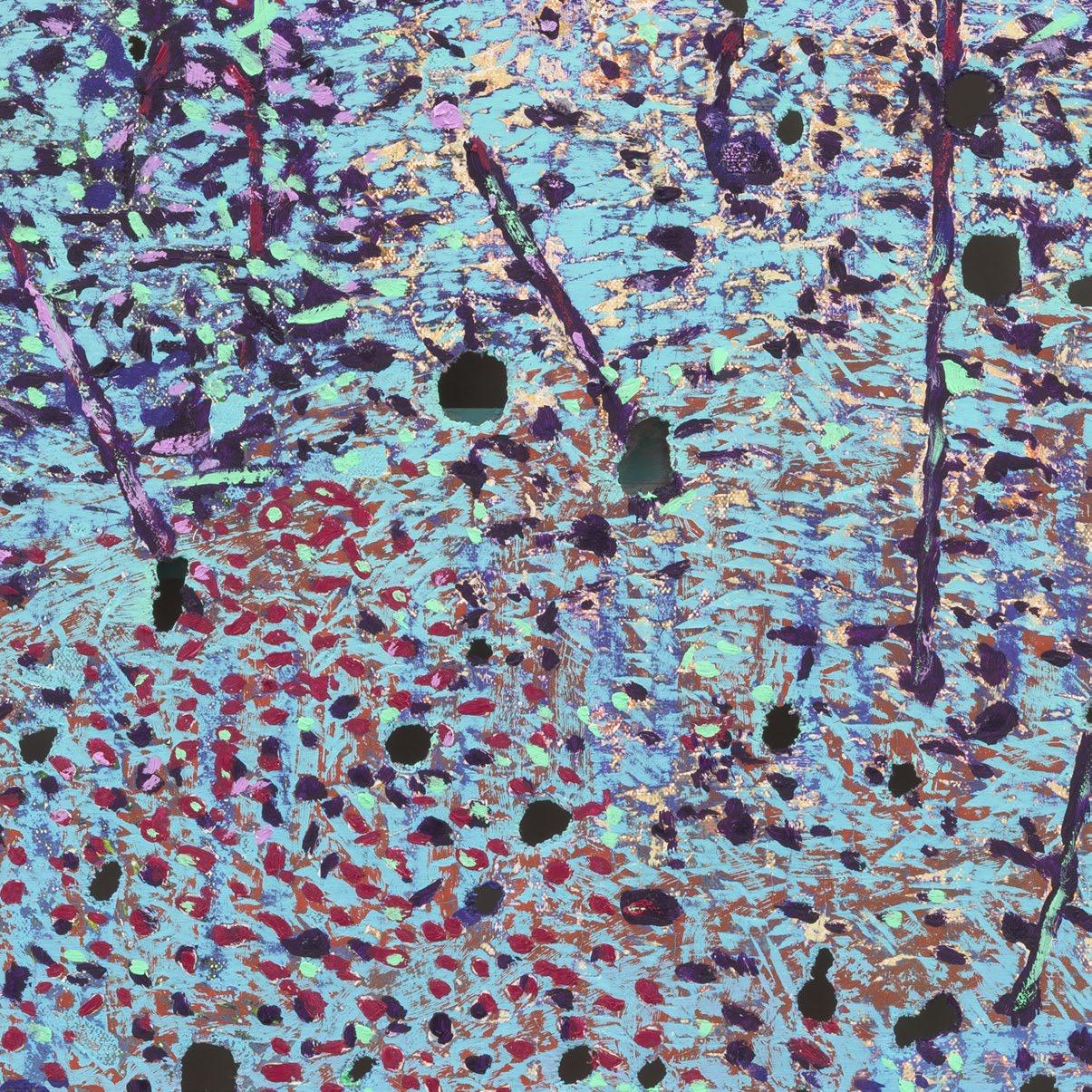

Cover: you can all love, (detail), 2017 - 2025