About AMJournal

Amsterdam Museum Journal (AMJournal) is a (diamond) open access, peer reviewed research journal that is published twice per year on the Amsterdam Museum website (AMJournal | Amsterdam Museum).

As the city museum of the eclectic capital of the Netherlands, the art and objects we show, the stories we host, and the societal issues that occupy us are complex by nature. This complexity requires a polyphonic approach; not one field or research can, or indeed should, tell the whole story. As such, rather than disciplinary, AMJournal is thematically oriented. Each calendar year, we publish editions that center on themes relevant to the cultural domain, public discourse and urban spaces, such as War, Conflict and the City (edition 1; October 2023), Deconstructing Gentrification (edition 2; Summer 2024), (Re)production (edition 3; Winter 2024), and Co-creating our Cities (edition 4; Summer 2025 – current edition).

Whilst AMJournal strictly publishes contributions that meet its high standards, the aim is to make research publications accessible for both readers and authors. AMJournal therefore publishes peer reviewed contributions by scholars in all stages of their research careers, from outstanding master students to the most lauded full professor (and anyone in between).

In addition, we publish essays and research papers by authors from all disciplines, from legal scholars to sociologists and from historians to economists. By centering on a theme rather than a discipline, complex issues are approached from various angles; demonstrating that it is through a polyphony of perspectives that we advance academic discourses. In short, multidisciplinary research is not merely encouraged, it is at the core of the Amsterdam Museum Journal.

To support scientific multivocality and offer a platform for various disciplines, AMJournal is modular, meaning each edition may include a combination of the following contribution types:

1. The Short Essays: short form texts in which authors succinctly defend topical thesis statements with proofs.

2. The Long Essays: long(er) texts in which authors defend topical thesis statements with proofs.

3. The Empirical Papers: qualitative and/or quantitative data analyses, or research papers.

4. The Dialogue: a conversation between the guest editor and another renowned scholar in their field on questions relevant to the edition theme.

5. The Polylogue: a thematic roundtable conversation with expert voices from various fields, from academic to artists, and from journalists to activists.

6. The Polyphonic Object: short complementary analyses by scholars from different disciplines of a single thematic object from the Amsterdam Museum collection.

7. The Visual Essay: a printed exhibition in which the analyses are based on images, which are then analyzed empirically and/ or by means of a theoretical framework.

All contributions are published in English and written according to strict author guidelines with the broader academic- and expert community in mind. Each AMJournal edition and each separate contribution is freely downloadable and shareable as a PDF-file (www.amsterdammuseum.nl/journals). To further aid accessibility, for both authors and readers, AMJournal does not charge readers any subscription- or access fees, nor does it charge authors Article Processing Charges (APCs).

Interventions Collecting the City

For the visual layer of the fourth edition of AMJournal, Co-creating our Cities, the editorial board has chosen to highlight a selection of collaborations from the Amsterdam Museum program line Collecting the City, a museological form of storytelling through co-creation. Collecting the City focusses on highlighting underrepresented narratives, allowing for a more inclusive approach to accounts of contemporary urban life. Through partnerships with the education department of the Amsterdam Museum, Amsterdam-based organizations and the

communities they represent play an active role in bringing their own voices and stories into the museum. The visual section of AMJournal #4 features excerpts from exhibitions that emerged from these cocreative processes.

All original pictures were commissioned by the Amsterdam Museum and taken by various photographers during openings or other events by the museum itself. For AMJournal #4, these pictures were edited by the journal's designer: Isabelle Vaverka.

Dear Readers,

We are proud to present the fourth edition of the Amsterdam Museum Journal (AMJournal), which is dedicated to the opportunities and complexities that come with ‘co-creating our cities’. Coexistence, coproduction, and cooperation are vital ingredients of (contemporary) cities. In fact, most of our urban experiences are born out of collaborations, which shape our environments.

AMJournal Edition #4 presents a diverse range of research that addresses the complexities of cocreating. It includes insights from various fields and domains, which are presented in the form of The Visual Essay, The Essays, The Empirical Papers, The Polyphonic Object (polyphonic object analyses), and The Polylogue (expert round table). From research papers on dynamic citizenship and collaborative argumentation to essays on co-creation in the practices of cultural institutions, this special issue examines equity, reciprocity, empowerment, and belonging as key aspects of co-creation projects and processes. By focusing on research from different disciplines and different places in the world, this AMJournal edition is able to study co-creation in different contexts and through different lenses.

As co-creation is not only a valuable field of study, but also a method employed in collaborative practices, this special issue includes a round table between various field experts and researchers on ‘how to define and

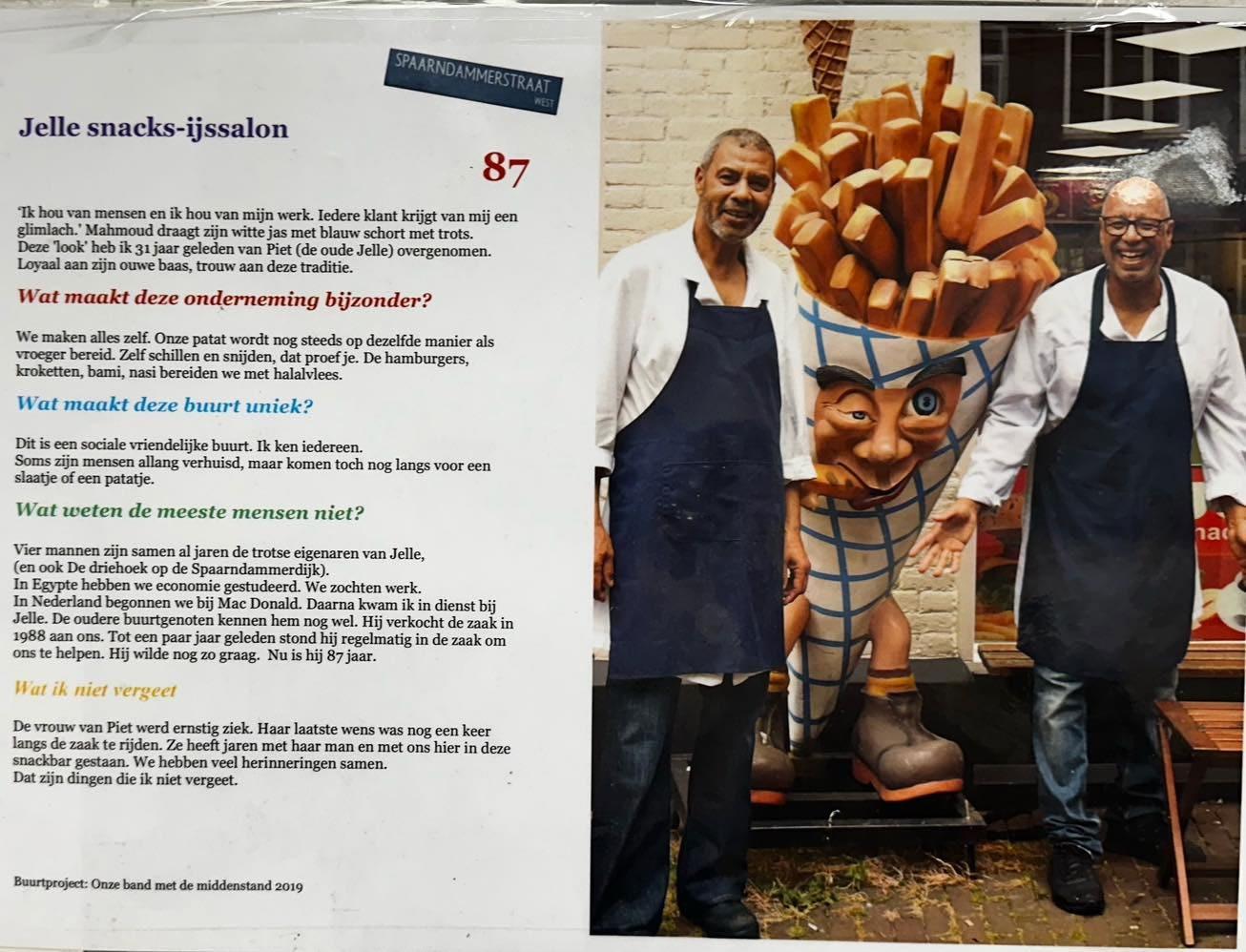

build a community’, ‘the importance of balancing different voices and power’, as well as ‘the impact of co-creation’ in their own research and practices. In addition, the insightful visual essay on AmsterdamEgyptian snackbars, which has won this edition's Best Paper Prize, highlights the importance of (migrant) communities in co-creating cities.

We would like to thank our contributors and readership for their engagement with this special issue. It is with your collaboration that we have been able to create such a comprehensive and layered edition on cocreation. We present an edition in which co-creation can be examined as a starting point for coexistence, as a practice for production, and as the result of communication.

Yours sincerely,

Dr. GL Hernandez

Edition Guest Editor

Dr. Vanessa

Vroon-Najem Edition Guest Editor

Dr. Emma van Bijnen

Editor-in-Chief

Homeless in the city: stories from the street 2025

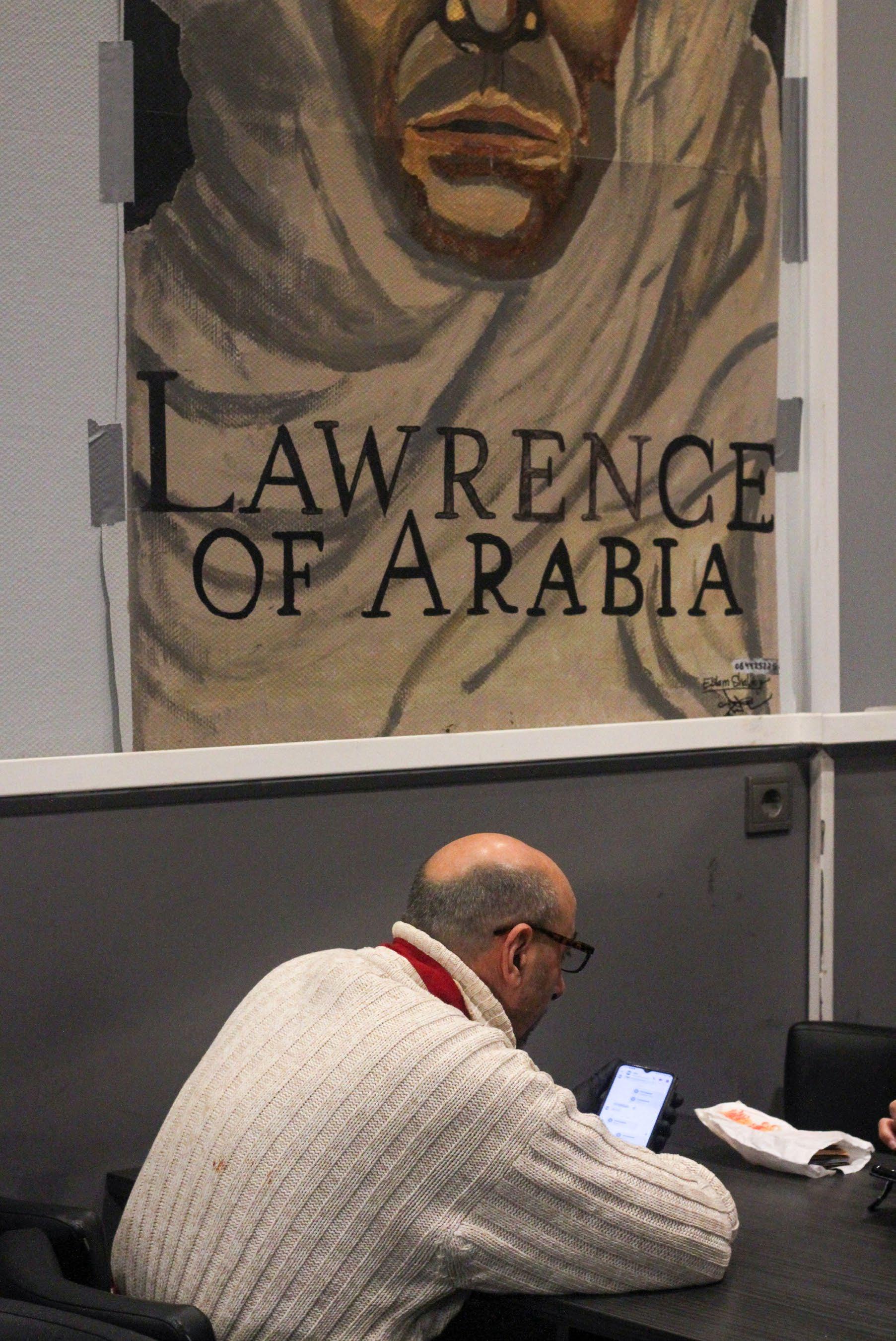

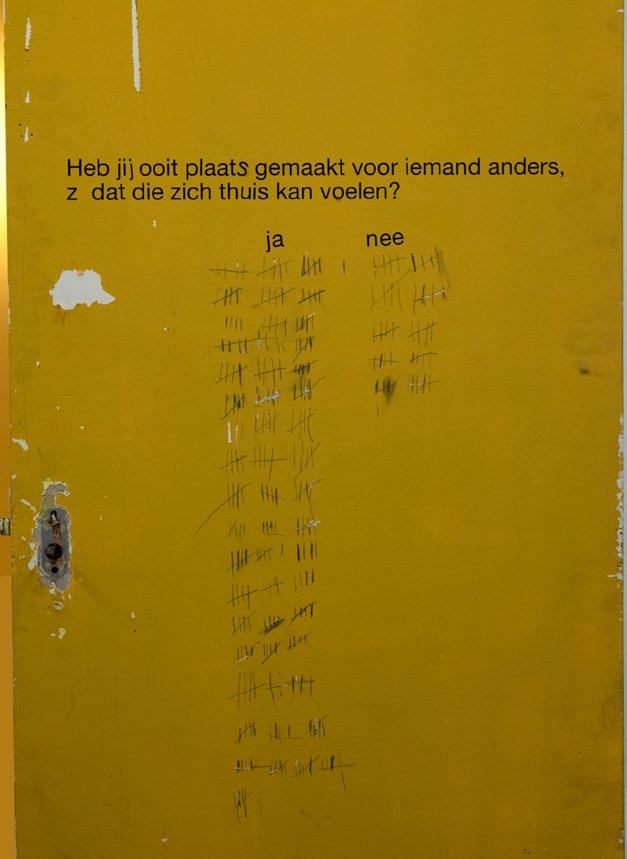

The exhibition Homeless in the city: Stories from the street (2025) focuses on homelessness in the city of Amsterdam. At the time of the exhibition, 17.000 Amsterdammers were homeless or itinerant. To present this topic in an appropriate manner, the museum worked in close collaboration with two organizations for homeless people: HVO Querido and De Regenbooggroep [translation: ‘The Rainbow Group’]. In addition to this collaboration, curators – Dorine Maat and Gonca Yalçiner –

worked with lived-experience experts through focus groups. This made for conversations that clarified what themes should be part of the exhibition and how these could be presented. The final exhibition included artworks made by such experts-by-experience, while also highlighting the complexities of the bureaucratic system that homeless people are forced to navigate. During the exhibition, special tours were organized to welcome people (formerly) experiencing homelessness in the museum.

The Essays

Experimental Co-Becoming

Dominika Mikołajczyk and Sarah Postema-Toews

Markus Balkenhol, Jessica Dikmoet, Danielle Kuijten and Jules Rijssen

Emily Schneider

Experimental Co-Becoming: Post-Commoning Practices in ACTA

Authors

Dominika Mikołajczyk and Sarah Postema-Toews

Discipline

Cultural Analysis

Keywords

Commons / Urban Space / Aesthetics / Precarity / Gentrification

Doi doi.org/10.61299/ki182HI

Abstract

This paper analyses ACTA, a former dentistry school in Amsterdam’s Nieuw-West repurposed into affordable student housing. The building embodies the ambivalence of urban life: it offers a communal refuge amidst a deepening housing crisis, while simultaneously commodifying bohemian aesthetics to legitimise substandard living conditions. We argue that ACTA exemplifies a mode of existence that catalyses commoning practices in conditions otherwise hostile to collectivity. Our analysis is conceptualised through ‘post-commoning’ – the practices of adaptation that appropriate both material and social structures in response to precarity. Repurposed classrooms and salvaged materials give ACTA its visual and ideological character, reflecting the efforts of early residents to create a self-managed, world-making space in the context of late capitalism. Methodologically, this paper draws on interviews with residents and photographs of its interiors. It puts into conversation the theoretical frameworks of Lauren Berlant’s commons, Henri Lefebvre’s ‘right to the city’, and Pierre Bourdieu’s ‘social space’ to unpack ACTA’s physical, social, and aesthetic complexities.

Introduction

In the Netherlands, the fate of so-called ‘free spaces’ (vrijeplaatsen), ‘breeding grounds’ (broedplaatsen), and squatted cultural venues reflects broader shifts in Amsterdam’s urban policy. Creativity has become “sutured to a mobile policy frame that has evidently been enabling, sustaining and normalizing a culturally tinged form of neoliberal urbanism” (Peck 464). Amid growing precarity, squatter initiatives are increasingly pressured to negotiate their survival through strategic concessions, often trading radical autonomy for institutional legitimacy (Uitermark 693). These forms of urban commoning – once positioned as resistance to the privatisation and commodification of city life under late capitalism (Harvey 87; De Angelis 10) – are now regularly co-opted (Martinez 51) or incorporated into municipal agendas (Uitermark 695). These energies are channelled into Amsterdam’s ‘creative city’ framework, which appropriates existing cultural histories and organisations in ways that render them marketable within a curated urban identity (Peck 472). Once rooted in housing struggles, these movements are increasingly redirected toward cultural programming, lending “progressive legitimacy to an increasingly business-oriented model of creative urban growth” (Peck 469). With little to no long-term security, this shift reflects the city’s unwillingness to support commoning practices grounded in shared living rather than cultural production.

This paper examines what happens when commoning emerges not before or outside of co-optation, but from within it. What forms of commoning become possible in spaces simultaneously enabled and constrained by institutional and corporate structures? In what follows, we explore this question, taking as its main case study the former ACTA building – a repurposed dental school in Amsterdam’s Nieuw-West now functioning as temporary student housing and artist studios. While scholarship has extensively covered vrijeplaatsen and broedplaatsen, ACTA occupies a distinct position between the urban commons and the private housing sector. Jointly owned by creative organisation Urban Resort and housing corporation De Alliantie, but shaped largely by its residents, the building reflects a new social terrain which we analyse through the concept of ‘post-commoning’, describing the collective practices that rework institutional infrastructures from within. Rather than seeking autonomy or resisting co-optation outright, ACTA’s residents navigate contradiction, reworking infrastructural constraints to forge common worlds afforded by, yet not reducible to, neoliberal urbanism.

A Few Words on ACTA

When the Academisch Centrum Tandheelkunde Amsterdam (ACTA) relocated to the Zuidas in 2010, its old building was left vacant, soon squatted by housing rights activists, and later acquired by De Alliantie to become ‘affordable’ student housing (operated by a company called Socius)2 and an artist ‘breeding ground’ run by Urban Resort. Today, the old ACTA building stands as a composite of 75 artists’ studios, a night club Radion, and TWA (Tijdelijk Wonen Amsterdam) – a temporary accommodation spread across 8 floors and 28 ‘hallways,’ or communal housing units, home to 460 students from different higher educational institutions in the Netherlands including Hogeschool institutes, Art Academies, and Universities. In this paper, our focus lies on the residential aspect of the building; TWA will be referred to as “ACTA” – the name commonly used by residents and visitors alike. But by using this term, we do not mean to encompass the artist studios or Radion, as those spaces function under different logics, and we do not have much insight into their practice. What we will refer to as ACTA is a set of relations and modes of living that exist specifically among the residents of the student housing – those who, by virtue of spending the most time in the building, have had the greatest opportunity to shape it as a shared environment.

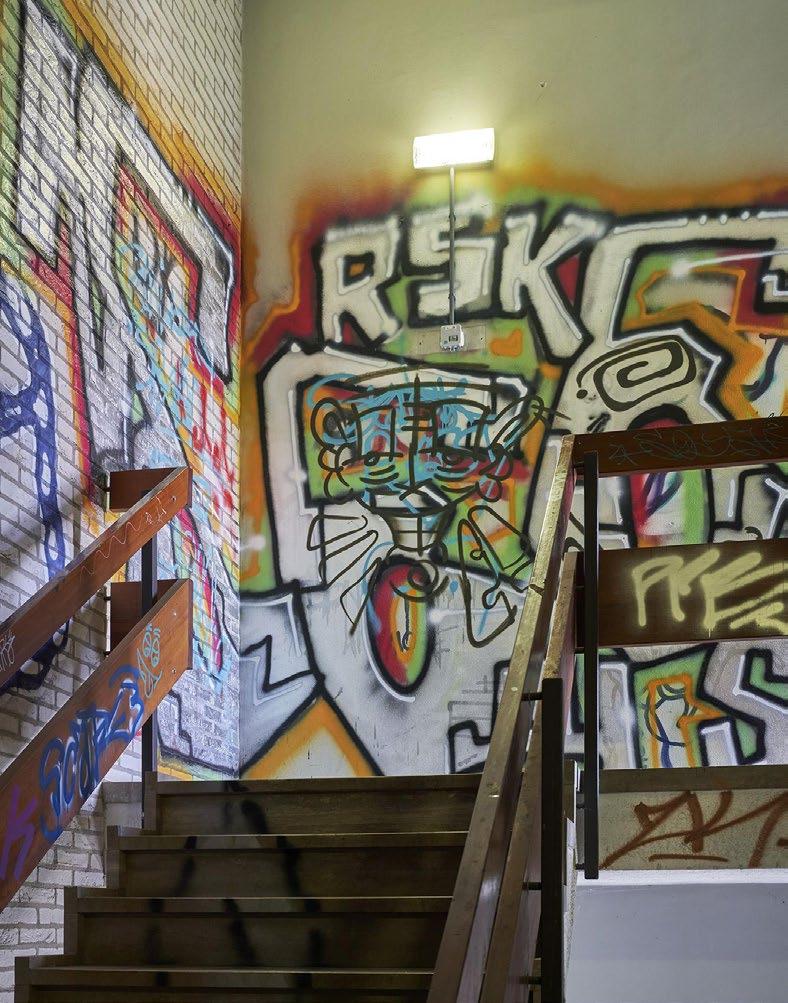

Experimental Co-Becoming

Our focus here is on what kinds of community, commons, or publics emerge in a housing solution that affords more agency in shaping its governance and everyday life than conventional residential buildings. At ACTA, residents can modify their spaces – they build additions to kitchens and bedrooms, paint murals on the walls, and choose housemates – creating a dense ecology of collective expression and co-becoming. Over the years, lecture halls became kitchens, classrooms were turned into bedrooms, and the sterile institutional architecture of the dentistry school gave way to a more layered and textured environment made out of mostly salvaged materials. Whilst a dedicated team of residents oversees larger operations, the day-to-day tasks are delegated to democratically chosen representatives of each flat. This does not come without internal tensions: residents often feel limited by what seem like arbitrary rules set by the TWA administration3. The space of agency also exists within a fraught lineage: the building, once squatted, is now privatised and owned by a corporation, exemplifying the ways Amsterdam’s activist-based housing solutions are being absorbed into the city’s corporate apparatus. At the same time, ACTA does not meet the official legal designation of an antikraak4 property, yet it exists within a broader framework of urban anti-squatting solutions. Distancing the building from a formal anti-squat can serve as a means to legitimise ACTA’s image as an alternative and socially progressive space whilst masking its contribution to the continued privatisation of non-commercial community spaces and affordable long-term housing.

Outline

As residents, our years of experience living in ACTA make us attentive to the conditions that shape it today. In what follows, we take a reflexive and situated approach to our analysis – one that foregrounds modes of relationality, negotiation, and world-building while also recognising how these dynamics are themselves implicated in larger politics of urban space. We argue that ACTA is an example of a mode of existence that catalyses commoning practices in conditions that are otherwise hostile to collectivity. This results in unexpected manifestations of growth, entanglement, and co-becoming that emerge within the cracks of housing infrastructures, ultimately not intended for these purposes. In Section 4, we explore how ACTA’s material and social infrastructures afford practices of collective life. This process unfolds through acts of repurposing on both macro and micro levels: ACTA itself is a repurposed institution, shaped by the appropriation of the very structures it seeks to resist (i.e. housing corporations, Dutch universities, and government programmes offering subsidised student housing). On a micro level, appropriation takes the form of everyday adaptations – supermarket shopping carts turned into makeshift transport or impromptu BBQ grills in the courtyard. These practices draw on the material and affective remnants of past commons to shape what we conceptualise as the post-commons: a social world forged within, rather than apart from, capitalist and institutional frameworks, reworking them without achieving autonomy from them.

The concept helps us account for the generative social forms at ACTA as modes of living and resisting that endure amid the precarity of late capitalist urbanism. While squats, squatted social centres, and ‘free spaces’ have historically nurtured similar forms of commoning, these practices are not limited to settings outside the law. Neither a squat nor a vrijeplaats, ACTA offers an instructive case, where the postcommoning potential does not reside in its structural features alone, but in how residents inhabit, repurpose, and socially organise within. In Section 5, we explore this ambivalence: ACTA’s postcommons, expressed through what we identify as an ‘aesthetic of appropriation’, offers a communal refuge amid a deepening housing crisis, yet one that simultaneously commodifies bohemian aesthetics to justify substandard conditions 5. Any creative or radical potential within ACTA, as we explore in this paper, does not stem from the building itself but from the residents who continuously choose to experiment, collaborate, and reimagine new forms of co-becoming. They do so despite the pressures of gentrification, rising living costs, threats to critical political speech and protest, and dwindling third spaces.

Experimental Co-Becoming

Theoretical Framework

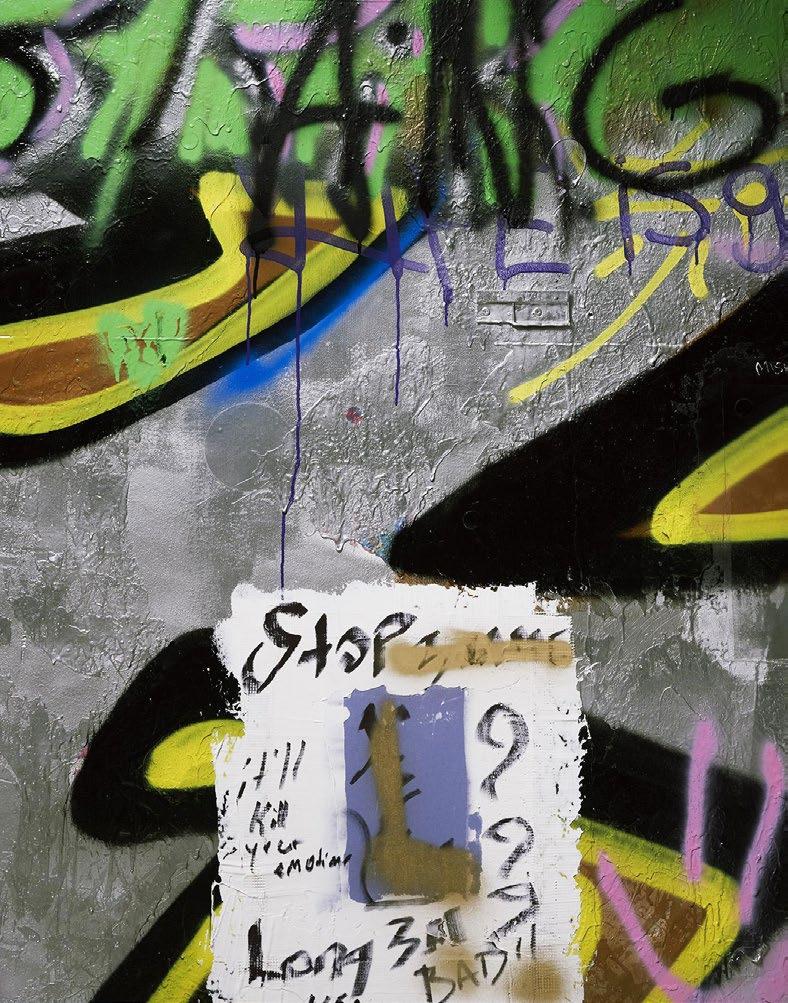

Social theorist Michael Warner understands ‘the public’ not as a configuration of individuals, but as an entity structured through discourse and textual forms – self-organised rather than dictated by an external authority (51). At ACTA, this manifests in the materiality of the space itself – graffiti-covered walls, political slogans, kitchen meetings, and the constantly evolving use of space do not merely reflect an aesthetic of resistance but function as a means of structuring life in common. This resonates with sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s concept of ‘habitus' – the relationship between sociality, space, and style. In his understanding, habitus is a mechanism through which one’s social position shapes how one interacts with the world. It marks collective identification through representational aesthetics, manifesting in both physical and social space. At ACTA, this becomes tangible through acts of decorating, dismantling, (re)building, and dialogue.

Drawing on philosopher Henri Lefebvre’s notion of the ‘right to the city’ – and its further elaboration by Alexander Vasudevan – we situate post-commoning practices at ACTA as responses to urban developments that constrain alternative imaginaries and forms of inhabiting the city under late capitalism. Historian Michel de Certeau’s distinction between strategy and tactic as distinct modes of engaging with urban space is relevant here: strategies are the mechanisms of power that structure the city, while tactics are the improvised, everyday manoeuvres through which people reclaim and reshape space (xix). We use this framework to understand ACTA’s ongoing existence and experimentation as reliant on tactics – on the ability to manoeuvre within dominant strategies, forging common worlds that elude, but are not entirely outside of, these systems.

In its ephemerality, the post-commons reveals something about the infrastructures of co-belonging that emerge when official structures fail –about how people assemble, make do, and create forms of collective life even in the remnants of what came before. We take as a starting point cultural theorist Lauren Berlant’s discussion of the commons, where they make a distinction between institutions, which congeal exclusionary power, and infrastructure, acting as a means through which “patterns, habits, norms, and scene of assemblage” happen (95). While institutions mainly build and facilitate infrastructure, infrastructure is not inherently institutional. This distinction is what our conception of the post-commons hinges on: the notion that the non-institutional commons is so easily co-opted by corporate forms of collectivity. The post-commons acknowledges the lack of infrastructure that non-corporate publics have access to and control over; at the

“This layering of objects and images creates a palimpsest – a layering of sedimented attachments written on the walls in which the material traces of new inhabitants and the pasts of previous tenants mingle, presenting a shared history through material sediment.”

same time, it retools pre-existing institutional infrastructure and adapts it, as Berlant puts it, “to invent alter-life from within life 6” (95).

Methodology

Our methodology is rooted in Cultural Analysis – an approach that emphasises the process of ‘concept work’ through close reading of texts, objects, and practices. It involves critically engaging with cultural artefacts to unpack their ideological, aesthetic, and social dimensions. In this paper, we treat the space of ACTA and interviews with its residents as a lens through which to think conceptually. In this way, our understanding of ACTA was shaped by lived experience, close reading, and ongoing concept work (with the post-commons as our primary theoretical tool). Drawing on Mieke Bal’s approach to Cultural Analysis7 and Donna Haraway’s call for situated knowledge 8, we grounded our analysis in partial, embodied perspectives that acknowledge the researcher’s positionality and embeddedness. This process was framed by questions such as: How does space shape behaviour? How do bodies move through and experience ACTA? How do aesthetics reflect and reinforce political ideologies? Rather than positioning our paper as an ethnography, the Cultural Analysis method offers a reflexive mode of knowledge production. The aim is not to provide a descriptive account of the community, but to develop theoretical insights through a process of conceptual engagement.

In an attempt to capture ACTA’s collectivity, our choices have been shaped by an endeavour to write with many voices9. As residents ourselves, we worked collaboratively, conducting interviews and shaping our reflections through ongoing conversations with hallmates and others (former and current residents) referred to us through our networks. Our inquiry began with a set of pressing questions – ones that shape the everyday conversations of residents while also situating the building within Amsterdam’s broader urban and social landscape. How does ACTA compare to a squat? How does it mobilise political action? What role does it play in fostering collective living? And how do its aesthetics shape the social lives of its residents? Guided by these conversations, our interview questions were organised around five general themes: General Experience, Space and Atmosphere, Aesthetics and Community, Positionality, and Ideology. All interviews were conducted in English 10, and we prioritised participants with different kinds of engagement in ACTA’s communal life, ensuring a range of backgrounds and perspectives, including a variety of ethnicities, sexualities, gender identities, and class backgrounds.

The interviews sparked nuanced conversations around ACTA’s role in gentrification, ideological echo chambers, mental health, drug exposure, and physical concerns about building safety, with varying degrees of criticism toward both the building and TWA’s responsibility. All but one (conducted online) took place in ACTA’s communal kitchens and residents’ rooms. Surrounded by personal objects, we pointed to posters, furniture, and belongings to prompt discussion and evoke memory. In this way, our object of analysis is not only the spoken word, but also the atmosphere, texture, and materiality of ACTA itself. While our selection inevitably leaves out many voices, it aims to capture key dynamics of ACTA’s commons while acknowledging the limits of representation. To further contextualise our work, we also invited a former resident, Simon Pillaud, to contribute in a different form. Instead of participating in an interview, he offered photographs of the building, adding another layer of interpretation to our paper.

Configuring Social Space

In what follows, we look at ACTA as a form of place-making that is improvised, reclaimed, and ever-evolving; a space not built from scratch but one (re)built, through acts of (re)construction and (re)imagination. This form of collaborative world-building occurs in the wake of the encroaching absorption of counter-culture into marketable forms. When the commons is subsumed, what emerges in its wake is the postcommons. This can be understood as a practice of adaptation: working with what is left behind and repurposing both material and social structures in response to precarity and instability. This process requires a constant state of negotiation, a pragmatic politics of inhabiting contradiction in order to survive. Postcommons spaces attempt to balance the threat of radical potential being flattened through its connection with institutional or corporate infrastructures, productive friction with institutional norms becomes essential to maintaining meaningful identity in these spaces. The following section’s analysis focuses on the everyday configurations of social space in ACTA: how continual rhythms of negotiation, stylistic expression, and affective accumulations constitute forms of post-commons practice.

The building filters the community into ‘halls’ – clusters of 12–21 residents who select each other through ‘hospiteeravonden’, informal gatherings where potential new hallmates are collectively chosen. This process creates distinct social ecologies within ACTA, with each hall developing its own collective personality shaped by shared beliefs, styles, and habits. The selection process is ambivalent: while it opens space for intentional community-building, it is also inherently exclusionary, with the potential

to foster overly homogenous groups and reproduce discriminatory biases. That said, ACTA currently hosts a remarkably diverse community, with residents from a wide range of international backgrounds, ethnicities, sexualities, gender identities, class positions, neurodiversity, religions, and ideological beliefs. The enclosure inherent to the ‘hospiteer’ system, then, serves as a mechanism to protect vulnerable groups, for instance, by rejecting candidates who misgender trans residents or display racial bias (Harvey 70). Still, ACTA’s position as one of the few remaining affordable living spaces is limited by its designation as a student building, inherently enforcing a form of class privilege afforded to those able to pursue full-time post-secondary education.11

Once selected, hallmates begin to build their shared lives in the spaces that bind them together. At the core of these micro-communities are the hall kitchens, which serve as both functional and symbolic spaces: sites of communal meals, collective decision-making, and the infamous ‘hall parties,’ where kitchens transform into makeshift clubs or music venues. The hall kitchens, then, are not just spaces of cohabitation but of world-building, where ACTA residents configure their social space through ongoing acts of curation and negotiation.

“On the surface level, it might look like a squat, but it helps to conceal the market forces that make its existence possible.”

Experiments in Stylistic Identification

In his interview, Santi describes that the layout of his kitchen directly influences how hallmates interact, shaping patterns of movement, conversation, and collective life within the space. In this way, ACTA’s interiors become material expressions of its paradoxical condition: fostering forms of self-organisation and alternative living, yet always within a structure that can, at any moment, be renewed. Even small changes in the kitchen’s layout shape hallmates’ interactions:

“Every now and then, there’s kind of a lull in how people are hanging out… and then a few people just out of nowhere get the spark to rearrange the kitchen… Maybe some new furniture gets added, and then people start gathering because it’s like, oh, nice new kitchen” (Santi).

This quote illustrates how rearranging the layout of the space can have a reinvigorating quality, leading to an immediate shift in how hallmates interact. It suggests that the arrangement of these kinds of collective spaces carries significance beyond function or aesthetics, becoming a configuration of the social space in physical form. As Bourdieu describes in his talk

“The building borrows the aesthetics of a squat but participates in redevelopment strategies, making the area appear more attractive, “creative,” and “bohemian” without challenging the logics of urban planning, property ownership, or capital investment.”

‘Physical Space, Social Space, and Habitus’, “social space is an invisible set of relationships which tends to retranslate itself, in a more or less direct manner, into physical space in the form of a definite distributional arrangement of agents and properties” (10). This configuring of social and physical space is also reflective of the affective undercurrents involved in negotiating the personal and the collective, that which make up co-becoming. In so doing, spaces like ACTA become a physical manifestation of post-commons collectivity – a conversation in the form of repurposed couches and strung-up photos.

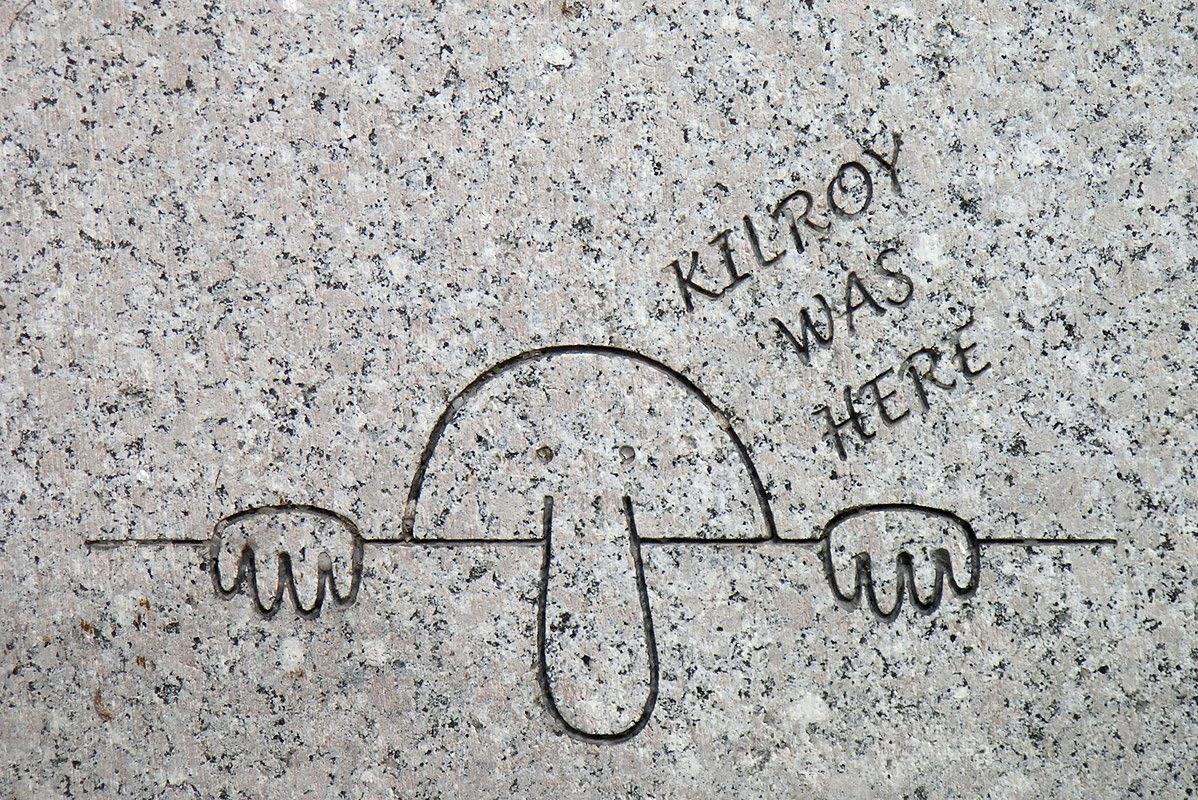

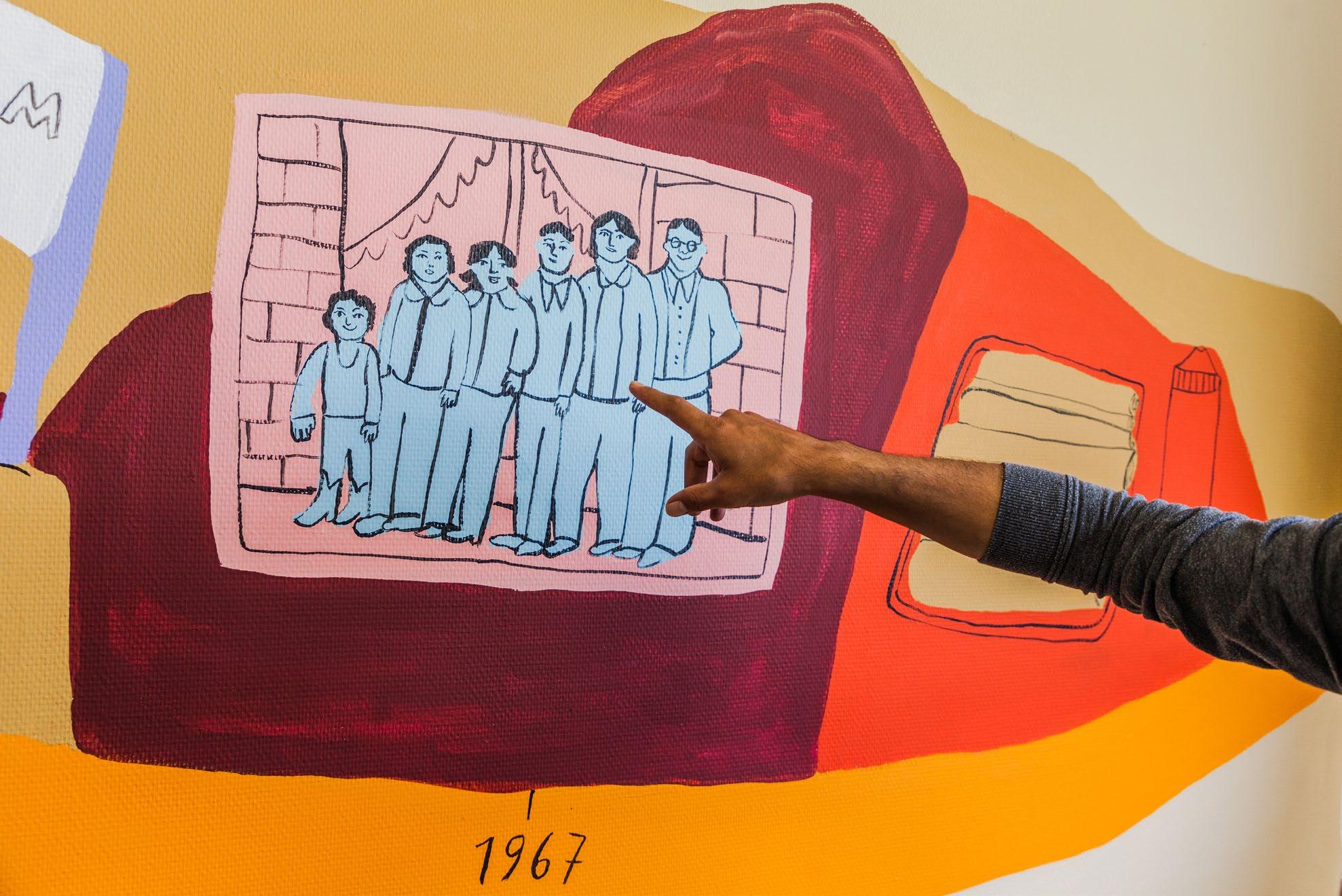

Another key part of the spatial set-up in the kitchens is cultivating a distinctive style that represents the hall. Cemre describes how his hallway kitchen’s walls serve as a living archive: “Filled with memories from the earliest residents to the newest – pictures, old dartboards, calendars… You see a history of what has been here and what hasn’t”. Over time, the style changes as new residents modify or remove decorations, leaving behind traces of the past. “You still see the corner pieces of torn-down posters”, Cemre notes, “a reflection of – okay, yeah, this was here, but also not, because now it’s a different type of hallway”. This layering of objects and images creates a palimpsest – a layering of sedimented attachments written on the walls in which the material traces of new inhabitants and the pasts of previous

tenants mingle, presenting a shared history through material sediment (Figure 5). This kind of use of space, through style and expression, acts as another form of configuration, creating a material embodiment of collective identity/personality through aesthetic impression.

The inclusion of decorations from residents' years past alongside current hallmates' contributions also creates an archival characteristic to the space. This throughline in decoration between residents across time, even after moving out, marks a persistent sense of belonging. The style of these collective spaces also marks signifiers of identity with all kinds of implications – aesthetically, socio-economically, ideologically, and politically. Anna12 reflects on how spatial configuration both facilitates sociality and reinforces a shared ethos:

“When it comes to the common spaces, you're also forced because you cannot make a decision by yourself, being like, oh, I would like to buy this huge IKEA table because I think it looks great. You're forced to also comply with whatever the legacy of the building is, as in how you run the spaces. I think we do follow the legacy of the building. I think these things have been decided way before we moved in. We follow how people live and then just continue on with this flow of reusing, refurbishing, not paying money” (Anna)

This ‘ACTA legacy’ describes a kind of social code exhibited materially and aesthetically. It constitutes a counter-script of what is considered acceptable in terms of furniture and decoration, one that contradicts the mainstream capitalist logic of following trends and continually purchasing new items. Here, the space articulates its form of cyclical style as its aesthetic seems to be rearticulated in similar ways, even when changes or modifications are made, such as patching furniture, creating decorations out of pre-existing items, or repurposing materials. ACTA's stylistic expression seems to try to exist outside of the mainstream economy as much as possible. It even manifests into a counter-economy of ACTA in which furniture cycles between halls through group chats and building-wide swaps and sales, as we’ll elaborate on further in the second section. “You don’t really buy things here”, Cemre explains. “You inherit them. You see something and think, ‘What can I do with this? How can I change it?’” This acts as one of the key practices within the post-commons mentality of ACTA, the continual repurposing of infrastructure on both macro and micro levels as a means of survival and expression outside of capitalist logic.

Habitus and Collective Aesthetics

Turning now to a broader scale of representational aesthetics in ACTA, the building leaves a distinctive stylistic impression on those who see the space. This impression marks a collective orientation toward particular stylised objects and modes of behaviour that make up and visually mark habitus, constituting a broader picture of what Anna called the ‘ACTA legacy’. Habitus (synonymous with disposition) is how a person’s social position subjectively informs the ways they see and interact with the world (Social Space and Symbolic Power 19). Bourdieu explicitly connects style and habitus, arguing, “One of the functions of the notion of habitus is to account for style unity, which unites both the practices and goods of a singular agent or a class of agents” (Physical Space… 13). This accounts for the recognisable aesthetic of ACTA as a social space, both physically and socially. The ability to choose one’s own hallmates and reconfigure spaces fosters a form of everyday world-building (both practical and symbolic). As Bourdieu writes, “Habitus are these generative and unifying principles which retranslate the intrinsic and relational characteristics of a position into a unitary life-style” (13). ACTA thus becomes a space for pockets of alternate forms of growth and collectivity within a precarious and often hostile housing system, this is the habitus ACTA cultivates. In turn, experiments in co-becoming, repurposing, and extra-capitalist logic become the rhythms through which the everyday is practised in this space.

Experimental Co-Becoming

Beyond having a collective style or interests and ideological beliefs in common, hallmates also circulate on an affective register through the intimacy of a shared home space built in collaboration with one another. This is another register of co-becoming, in which individual experiences of the everyday rhythms of life and emotion coalesce into collective impressions. Cemre offers one of these moments of collective emotion:

“This week or the past two weeks, good things have been happening to me. The past week, good things have been happening to another roommate. I noticed that at least for five or four people, easily they're all in good moods. And when you're in good moods, you sort of infect each other with that … What's going on? Are we collectively, you know, just having good news? So, yeah, definitely the mood affects each other significantly… And the same goes with bad moods.” (Cemre)

This kind of collective mood or atmosphere conveys the entangled social affect present in ACTA. Hallmates reinforce each other’s emotional states, creating a porous network of feeling that challenges ideas of individualised perspective. We believe this is in part related to the distinct collective aesthetic ACTA cultivates. In her influential paper ‘Happy Objects’, Sara Ahmed explores the idea that objects are ‘sticky’, meaning they can accumulate emotional and affective associations through our interactions with them (29). Ahmed argues that objects contribute to social cohesion, as shared judgments about certain objects help shape group identities and dynamics (35). If we view the common spaces in ACTA as collections of stylised objects, each with their own histories and potentials of identification, the accumulation of expression written on the walls acts as a physical manifestation of each hall’s particular social space.

In this case, aesthetic identification is closely tied to reinterpreting the building’s existing materials and histories. This creates spaces that hold contingent atmospheres of collective material expression. This collective aesthetic expression, defined in part through the post-commons practice of creatively repurposing pre-existing structures, also manifests in the rearticulation of emotion between residents. This constitutes an affective layer to what Bourdieu calls social space. Multifaceted collectivity allows the building to maintain anchor points of commonality for residents to attach to, despite the constantly shifting demographics as students move in and out. We share a home in common, we share a stylised history in common, and so we share a vision for living together in common. Being constantly

Experimental Co-Becoming

surrounded by this polyphony of co-constituency marks the residents of ACTA’s halls as a post-commons, bleeding into atmospheres of collective emotion and intersubjectivity.

Aesthetics of Appropriation

The residents’ ideological and political preferences reveal themselves through layers of overlapping visual markers that constitute a mode of address, or what Warner might describe as a ‘counterpublic’ – a public constituted through discourse that positions itself in opposition to dominant norms (81). Counterpublics suppose a social marking; those willing to participate in this kind of scene are never just ‘anyone.’ Ordinary people, Warner writes, “are presumed to not want to be mistaken for the kind of person who would participate in this kind of talk” (86). Furthermore, a counterpublic maintains, consciously or not, an awareness of its subordinate status (Ibid.). ACTA residents are not incidentally drawn to repurposed furniture or collective living arrangements; these reflect a conscious negotiation of their position as resistant to dominant economic and social norms. Their material practices are underpinned by a political understanding of precarity, exclusion, and refusal – an intentional alignment with a counterpublic logic, and not solely an aesthetic preference.

Co-becoming here is visual, emotional, and political; residents attract like-minded people while shaping and reinforcing shared values. Sabi reflects, “At the end, people get stuck with each other’s beliefs a lot... It attracts other more activist people of the like-minded type”. Over time, this produces a distinct ideological framework – what Titus calls a ‘bubble', where radical left-wing politics are the norm, and deviation can feel isolating. In what follows, we argue that ACTA’s mode of address is expressed through what we understand as an aesthetics of appropriation – a visual identity set by how residents repurpose, re-signify, and inhabit the remnants of pre-existing structures for anti-institutional agendas. Working across several scales and media, this aesthetic risks appropriating the visual language of squatting, even though residence is fully sanctioned and legally regulated. While ACTA offers the potential of alternative living by repurposing the building for for-profit purposes, it ultimately forecloses the possibility of more radical arrangements (e.g., rent-free squatting) being established there. On the surface level, it might look like a squat, but it helps to conceal the market forces that make its existence possible. This raises important

Experimental Co-Becoming

questions about what kinds of resistance are allowed to exist under capitalism, and how aesthetics once tied to radical autonomy become absorbed and rebranded within marketable bohemian imaginaries.

Counter-Economies as Urban Tactics

De Certeau’s distinction between ‘strategy’ and ‘tactics’ helps unearth a politics to ACTA’s postcommoning practices. Strategy, in de Certeau’s terms, is the logic of institutions, the calculated ordering of space that defines ownership, control, and long-term planning. Tactics, by contrast, are the fluid, opportunistic manoeuvres of those who do not have the luxury of long-term control. A tactic “insinuates itself into the other’s place, fragmentarily, without taking it over in its entirety” (xix). It is an act of creative survival within the precarity of an imposed system.

In Amsterdam, social interaction often comes with a price tag. “Hanging out with people is so expensive”, Sabi remarks,

“Like, you leave your house and any place to hang out costs money… I like that ACTA still has spaces for interaction, for hanging out and socialising, that are completely free. You can just sit in the kitchen with your hallmates, or in the courtyard, or if there’s a party, you can just go without paying to get into a club”. (Sabi)

ACTA functions as a rare sight in the city where social life unfolds outside the pressures of consumerism. “It’s a public space that exists outside of the economy”, Sabi continues. “Whichever definition of the commons you look at, sharing resources is always central – and ACTA is no exception” (Marta). During the COVID-19 pandemic, Marta recalls that this informal economy of favours and exchanges became even more pronounced.

“It’s like a marketplace where you can find anything you need for free or for a beer. I remember this one time our cat was sick, and we needed a syringe – either to feed it or to give it anaesthesia, I don’t remember. And somebody on the eighth floor just happened to be a veterinary student, so they had all the syringes we needed”. (Marta)

ACTA’s qualities for supporting postcommoning cannot be reduced to its function as student housing alone. When compared to more conventional student accommodations like Uilenstede, the contrast becomes sharper.

“ Uilenstede was just a bit… cleaner, you know? ” Santi notes, “ Like, it was physically cleaner, but also structured in a way that made it clear it was built for students. The colours, the organisation, the little gym and restaurants – it all felt designed and controlled. You were always aware that you were in a student city.” “Every time I see ACTA when I’m walking towards it, even from far away, it just represents a different way of doing things”, he continues, and this time, compares the building to a squatted artist community outside Amsterdam.

“Ruigoord is seen as a success story of a place that lives by its own rules. But I think ACTA is an even more relatable success story because it’s not so far outside the city. It’s not about rejecting the city’s rules – it’s about engaging with the city but still doing things our way.” (Santi)

Differently to Ruigoord, ACTA negotiates its existence within the city’s framework. Its aesthetic of appropriation – the swing and tables in the courtyard fashioned from old doors, the pop-up bars built from wooden pallets – is not just a response to the economic realities of Amsterdam, but also an intervention, where alternative urban realities co-exist within capitalist municipal agendas. “What is counted [by logics of strategy] is what is used, not the ways of using” (De Certeau 35), and use is precisely where ACTA’s significance lies. In a way, the aesthetic itself can be seen as a tactic.

Within the landscape of Amsterdam’s ‘creative city’ programmes as described by Peck, ACTA represents a pseudo-private space that enables a different trajectory. Its capacity to host communal life stems from a series of contradictory adaptations: a legally sanctioned but under-regulated building inhabited by a student population engaging in everyday acts of mutual aid, infrastructural improvisation, and informal governance. As such, ACTA’s post-commons demonstrates how collective autonomy survives by repurposing, not escaping, the constraints of institutional frameworks. In this way, the residents’ tactical practices function as an ‘alterlife’ – a life already recomposed by the molecular productions of capitalism; a life in the ruins of public infrastructure, where community can only flourish through a repurposing of hostile systems. Unlike the vrijeplaatsen or broedplaatsen, ACTA was never fully incorporated into Amsterdam’s municipal cultural policy. This structural ambiguity creates a grey zone where forms of collective world-making can persist. These practices neither defy nor comply with the city’s developmental logic; they instead navigate it from within, with appropriation serving as a tactic to navigate dominant urban planning strategies and make space for life otherwise.

“But ACTA is also a Ship of Theseus – its residents come and go and take along with them much of their energies to organise, build, and grow. As residents change over time, ACTA changes too, ebbing and flowing along with new visions of what the building should be.”

The Right to (Re)Build and to (Re)Imagine

Lefebvre’s conceptualisation of ‘the right to the city’ further contextualises the example of ACTA as a postcommons within the broader struggle over urban space. Lefebvre argues that cities are not merely built environments but ‘oeuvres’ – co-shaped by those who inhabit them in dialogue dictated by top-down forces of planning and capital (101). Yet, this dynamic is inherently unequal: institutions and other systems of governance (‘the far order’) impose their vision of urban life onto the everyday practices of residents (‘the near order’), prioritising exchange value over use (152). In response, Lefebvre calls for ‘a right to the city,’ a demand for participation, appropriation, and inhabitation beyond market-driven urbanism (154).

But ACTA does not simply claim a right to exist within the city – it embodies what Alexander Vasudevan calls ‘the right to a different city’. Extending Lefebvre’s argument, Vasudevan emphasises the need to reimagine urban life in ways that go beyond securing access to space (318). He argues that alternative urban realities must be actively produced through occupation and self-organisation, creating spaces that foster political, social, and cultural experiments outside dominant urban systems (316). ACTA exemplifies some characteristics of a space that exercises these rights: it provides affordable housing in a city where living costs continue to rise and functions as a collective site of experimentation in post-common forms. Yet, while “the ACTA legacy” still permeates its walls, the building exists in flux. It is not a squat nor a conventional rental property, but a negotiated space, deliberately positioned within legal and economic structures that prevent it from being reclaimed as an actual squat. In many ways, it serves to legitimise anti-squatting policies.

“I think you can't take this building without its history of squatting”, Cemre notes. “The reason why it ended up becoming like this is because they wanted to prevent people from actually squatting in the building. So they were like, ‘Okay, we should rent this out to some other company that ends up renting it out so that it can't be an anti-squat or that it can't be a squat place’”, Lefebvre’s notion of ‘the far order’ becomes evident here. The Dutch state, in alignment with property owners and real estate developers, has long sought to regulate and contain the practice of squatting13. ACTA, in this sense, is a symptom of the broader struggle between pro-squatting movements and anti-squatting policies in the Netherlands.

“The way that ACTA is built as a way of living space is a direct reflection of the neoliberal capitalist project that the anti-squat enables. Anti-squat is not there to care for us.

Anti-squat is not there to make affordable housing in the city, no matter how many times they have to write this on their project proposals to get the municipality to agree to it.

Anti-squat is there to ensure that big owners and land developers get to keep their properties for as long as they want before selling them for the highest price they can foresee without having to make them actually livable for people.” (Marta)14

This tension between appropriation as an act of urban resistance and the institutional frameworks that co-opt and neutralise its radical potential complicates ACTA’s position within the right to a different city. Vasudevan describes autonomous spaces as ones that operate outside dominant urban systems, generating alternative forms of living by occupying and re-imagining the city (321). ACTA embodies many of these characteristics, yet it remains legally sanctioned, bound to agreements that prevent it from fully becoming an autonomous zone. Berlant claims that the desire to have a public that is free to be an indeterminate space is integral to historical understandings of the commons (81). While ACTA’s aesthetics of appropriation evoke the image of an autonomous space, the building’s history exposes a contradiction. The building borrows the aesthetics of a squat but participates in redevelopment strategies, making the area appear more attractive, “creative,” and “bohemian” without challenging the logics of urban planning, property ownership, or capital investment. In doing so, it risks contributing to the city’s efforts to gentrify Nieuw-West, ultimately accelerating the displacement and exclusion of lower-income communities. This situation echoes Warner’s dialectic of circulation, where counterpublics embody a struggle between authenticity and commodification. He writes,

“To be hip is to fear the mass circulation that feeds on hipness and which, in turn, makes it possible; while to be normal (in the ‘mainstream’) is to have anxiety about the counterpublics that define themselves through performances so distinctively embodied that one cannot lasso them back into general circulation without risking the humiliating exposure of inauthenticity” (73).

Many scholars have highlighted that artists act as a ‘colonising arm’ (Ley qtd. in Mathews 665) or as ‘canaries' (Peck 467) for new urban economies, with cycles of gentrification beginning with artists and/or students settling neighbourhoods. This process acts as the inversion of post-commons appropriation, with capitalist institutions syphoning the energy and generative outputs of post-commoning practices. This flattens the ‘coolness’ of bohemian lifestyles into a commodifiable product, thus restarting cycles of precarity and dispossession that necessitate these tactics of appropriation in the first place. ACTA here operates as a mechanism that maintains the illusion of autonomy through a right to appropriate while preserving the city’s power to withdraw its support when convenient.

Conclusion: Is There Such a Thing as an Actan?

In times of increasing polarisation and exhaustion from the intensive individualism and competition that capitalist systems require, maintaining an authentic and non-commercial collective is difficult. The figure of the ‘acta resident’ is bound by tension between collectivity and rebellious individuality. But ACTA is also a Ship of Theseus – its residents come and go and take along with them much of their energies to organise, build, and grow. As residents change over time, ACTA changes too, ebbing and flowing along with new visions of what the building should be. As discussed in Section 4, traces of residents’ pasts leave material marks, influencing in turn the scripts or legacies of the building. There are ongoing debates around whether or not ACTA used to be more connected as a building, as Cemre puts it: “The relationship to the other sort of hallways you can see more clearly has definitely waned. I feel like hallways are more isolated nowadays”. There are disagreements about the term ‘Actan’ —in Titus’s interview, he rejected the term, suggesting it is a product of TWA management’s effort to designate a community in a top-down manner. This feeds into what Berlant describes as the “contemporary crisis of the ‘we’” (82), in maintaining a collective without the external power influences of institutions and corporations. What ACTA’s post-commons attempts at collectivity show us is constant negotiation, expressed materially in the space and in its particular modes of post-commons relation.

In Section 5, we delved into the aesthetics of appropriation, as well as post-commoning practices like repurposing, and how they create a distinctive impression of the building that many residents latch on to. “ACTA changed that horizon of possibility for me”, says Marta after having moved out for 2 years, “the possibility that this could be in Amsterdam allows you to dream and imagine and take action towards a lot of different worlds than

the one you are inhabiting”, she continues. Santi, too, reflects that ACTA “has made people a lot more conscious of how they would ideally like to live and I think that’s also maybe where the rebelliousness comes from a little bit, is just realising that this is possible somewhere and not wanting to give that up for living somewhere else”. The residents mark ACTA, but the building marks them too, prompting them to carry its post-common creative ethos into other contexts.

ACTA is constituted in part by its impermanence. Sabi remarked,

“I think it promotes a positive association with change and the feeling that nothing will last forever. And I really appreciate ACTA for that. The fact that I know it's not gonna last forever and everybody knows that and the fact that we are enjoying it and change will come and things will get demolished, but still it's cool right now”. (Sabi)

At the same time, even as the body of residents is constantly shifting and decorations and layouts evolve over time, a feeling of constancy also endures. ACTA lingers like the moss clinging and growing on pre-existing institutional structures, and the collective maintains its continuity by adjusting to constant change. Precarity necessitates this constant adaptation, a process that embodies the ambivalence of post-commons urban life, fueled by Amsterdam’s deepening housing crisis. The building’s identity is steeped in Amsterdam’s history of squatting and grassroots resistance, but it also reflects the strains of neoliberal urbanism that charge rent for impermanence. As Peck notes, "For their very credibility… creative-cities policies must tap into, and valorise, local sources of cultural edginess, conferring bit-part roles to creative workers as a badge of authenticity for the policies themselves” (468). The perceived freedom in expressive possibility of the post-commons comes with the flip side of chronic under-maintenance, masking substandard living conditions. The generative potential of the building exhibits in experimental collective expression often comes in spite of these structural deficiencies. We suggest the post-commons as a tactic for maintaining extra-capitalist collectivity, as its potentials and shortcomings hold relevance far beyond the walls of ACTA, suggesting new ways of co-becoming and fostering alter-life in contemporary urban life. Throughout this paper, we have argued that the residents of ACTA survive in an environment hostile to non-commercial collectivity by appropriating pre-existing infrastructure, using it for their own worldmaking needs and experiments in co-becoming. Despite the impermanence

“ACTA lingers like the moss clinging and growing on pre-existing institutional structures.”

of ACTA both in terms of looming threats of demolition and the constant cycle of change of residents, continuity remains in some form:

“This feeling of permanence is. I don't know, cancels out this temporary feeling… This thing is going to exist and persist even when you're gone. Even when I'm gone. You know, like when everyone's gone, it feels like this place will still remain or something…. People move out and then come back, they say, ‘oh, it's so similar in a way, or the feeling is the same’” (Cemre).

While ACTA is defined by constant experiments and changes, a continuous thread is maintained over time. This thread is carried through post-commoning practices of appropriation and renewal – processes ultimately necessary for the survival of common spaces in hostile capitalist ruins.

Acknowledgements

We would first like to thank our interviewees – Titus van der Valk, Anna (anonymous), Sabi Falgàs Ortega, Santiago Camara, Cemre Cengiz, and Marta Pagliuca Pelacani – for generously sharing their time, reflections, vulnerability, critique, and care. A special thanks to Marta, who joined us online to offer theoretical insights and reflect on our conceptualisation of this unique space. We are also grateful to Hannah Pezzack for her thoughtful edits and to Daan Wesselman for his valuable guidance on framing our methodologies and theoretical approach. And lastly, we would like to thank ACTA residents, past and present, for building, painting, sharing, compromising, and choosing to be together. This building would not have been the same without your efforts.

Experimental Co-Becoming

References

Ahmed, Sara. "Happy Objects." The Affect Theory Reader, edited by Melissa Gregg and Gregory J. Seigworth, Duke UP, 2010.

“Amsterdam: ‘Free’ Space and Squatting. No More Caged Chickens.” Squat.net. 2019. en.squat.net/2019/09/08/ amsterdam-free-space-and-squatting-no-morecaged-chickens/

Bal, Mieke (Maria Gertrudis), and Bryan Gonzales, editors. The Practice of Cultural Analysis : Exposing Interdisciplinary Interpretation. Stanford University Press, 1999.

Berlant, Lauren. “The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times.” Environment and Planning. D, Society & Space, vol. 34, no. 3, 2016, pp. 393–419, doi.org/10.1177/0263775816645989.

—. "The Commons: Infrastructures for Troubling Times." On the Inconvenience of Other People, Duke UP, 2022.

Boer, René, Marina Otero Verzier, and Katía Truijen, editors. Architecture of Appropriation: On Squatting as Spatial Practice. English ed., Het Nieuwe Instituut, 2019.

Bourdieu, Pierre. "Physical Space, Social Space and Habitus." Institute for Social Research, 1996, Uof Oslo Sociology Department. Lecture.—. "Social Space and Symbolic Power." Sociological Theory, vol. 7, no. 1, spring 1989.

"Broedplaatsenoverzicht" ["Breeding Ground Overview"]. Gemeente Amsterdam Onderwerpen, Gemeente Amsterdam, www.amsterdam.nl/kunst-cultuur/ ateliers-broedplaatsen/over-broedplaatsen/ broedplaatsenoverzicht/. Accessed 16 Feb. 2025.

Certeau, Michel de. Translated by Steven Rendall. The Practice of Everyday Life. University of California Press, 1988.

De Angelis, Massimo. Omnia Sunt Communia: On the Commons and the Transformation to Postcapitalism. Zed Books, 2017.

Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, 1988, pp. 575–99, doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

Harvey, David. Rebel Cities: From the Right to the City to the Urban Revolution. Verso, 2012.

Lefebvre, Henri. Writing on Cities. Translated and introduced by Eleonore Kofman and Elizabeth Lebas. Blackwell Publishing, 1996.

Martinez, Miguel A. Squatters in the Capitalist City: Housing, Justice, and Urban Politics. Polity Press, 2019.

Mathews, Vanessa. “Aestheticizing Space: Art, Gentrification and the City.” Geography Compass, vol.

4, no. 6, 2010, pp. 660–75, doi.org/10.1111/j.17498198.2010.00331.x.

Peck, Jamie. “Recreative City: Amsterdam, Vehicular Ideas and the Adaptive Spaces of Creativity Policy.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 36, no. 3, 2012, pp. 462–85, doi. org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2011.01071.x.

Robbe, Ksenia. “Forms of Implication in Post-Soviet and Post-Apartheid Fictions of Witnessing.” Netherlands Research School for Literary Studies- Forms of Post-Colonial and Post-Socialist Time, 8 Dec. 2024, University of Amsterdam. Lecture.

“TWA ” Socius, 2023. Available at: www.sociuswonen.nl/ locaties/twa/ (Accessed: 16 February 2025).

Vasudevan, Alexander. “The Autonomous City: Towards a Critical Geography of Occupation.” Progress in Human Geography, vol. 39, no. 3, 2015, pp. 316–37, doi.org/10.1177/0309132514531470

Endnotes

1. Broedplaatsen emerged in the 1990s as a result of the municipal government’s strategy to use derelict spaces for creative and community-driven pursuits until further developmental projects can be put to action. Broedplaatsen have since been spaces designed to incubate artistic and cultural production in Amsterdam, but their existence is temporary and oftentimes precarious (Gemeente Amsterdam). This policy reflects a larger shift the Amsterdam municipality made to regulate community spaces facilitated by squatter organisations via the Free Spaces Accord (vrijplaatsenakkoord), first introduced in 1999. This policy is controversial among squatting organisations, with some groups criticising the accord as a means of absorbing the cultural vibrancy of squatting without meaningfully supporting squatter organisations. The main criticism entails the transformation of Free Spaces into non-residential cultural hubs, pushing out local artists and other residents who rely on the affordable housing that squats provide (Squat.net).

2. The residential section of the former ACTA building is owned by housing corporation De Alliantie. It is operated by Socius Wonen, an organisation that manages temporary housing for young people across the Netherlands. This location, officially called TWA, provides student accommodation (“TWA,” Socius Wonen).

Experimental Co-Becoming

3. One such tension between TWA management and residents is the mechanism through which cleaning and fire safety measures are enforced: hallway managers are expected to fine residents for not finishing cleaning tasks on schedule and for not keeping their hallways free of clutter. While hallway managers are themselves residents of each hall and their management styles vary, this system also acts as internal policing and monetary punishment for an already financially vulnerable demographic.

4. Antikraak (in English: anti-squatting) refers to temporary housing arrangements in which tenants, often with limited rights, occupy vacant properties to deter squatting and vandalism. Though presented as flexible and affordable, such contracts typically lack tenant protections and allow property owners to avoid vacancy while retaining control over the space. See: Boer, René, Marina Otero Verzier, and Katía Truijen, editors. Architecture of Appropriation: On Squatting as Spatial Practice. English ed., Het Nieuwe Instituut, 2019.

5. Confer: Peck, Jamie. “Recreative City: Amsterdam, Vehicular Ideas and the Adaptive Spaces of Creativity Policy.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, vol. 36, no. 3, 2012, pp. 462–85.

6. Originally coined by Michelle Murphy, alterlife “names life already altered”, or life “recomposed by the molecular productions of capitalism” and “entangled within community, ecological, colonial, racial, gendered, military, and infrastructural histories that have profoundly shaped the susceptibilities and potentials of future life” (497). In revoking this concept in a different light, Berlant proposes that alterlife can be invented from within, reframing it as a process rather than a pre-existing condition.

7. Confer: Bal, Mieke (Maria Gertrudis), and Bryan Gonzales, editors. The Practice of Cultural Analysis: Exposing Interdisciplinary Interpretation. Stanford University Press, 1999.

8. Confer: Haraway, Donna. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies, vol. 14, no. 3, 1988, pp. 575–99.

9. Writing with ‘many voices’ as a focus on hearing others and an effort to democratise discourse often overlooks how those voices have been framed and organised (Robbe). We write with many voices, but

not with all, selectively including certain testimonies over others to explore a defined domain of inquiry – the (post)commons. This approach does not claim to provide a complete or more truthful account than others; rather, it represents an effort to engage meaningfully with the specific questions that shape and guide this research.

10. While all interviews were conducted in English, it is important to note that English was a second language for both us as researchers and for all participants. Titus and Cemre were the only interviewers whose native language is Dutch; One of the co-authors speaks Dutch as a second language. Despite the Dutch context, English has become the dominant language in ACTA. This wasn’t always the case, but over time, ACTA has shifted into a predominantly Englishspeaking community, shaped largely by the influx of international students. English now functions as the main language of everyday communication among residents.

11. This structure excludes many marginalised groups, including disabled individuals, those who cannot afford to study, and those excluded due to immigration status. A clear example of this is TWA’s recent decision to end eligibility for students pursuing secondary vocational education, thereby reinforcing societal biases against trade-based education.

12. One interviewee wished to remain anonymous; we will refer to her as ‘Anna’ throughout the paper.

13. Squatting was decriminalised in the 1970s but increasingly restricted through legal reforms, culminating in the 2010 ban.

14. The quote was edited to remove profanity at the request of the interviewee.

Herdenken en Helen in Amsterdam

Authors Markus Balkenhol, Jessica Dikmoet, Danielle Kuijten and Jules Rijssen

Discipline Anthropology and Heritage Studies

Keywords

Co-creation / Memory Culture / Slavery / Amsterdam / Intangible Heritage

Doi doi.org/10.61299/It141TR

Abstract

Through this essay we aim to contribute to a more nuanced and multifaceted understanding of co-creation. We present ‘Herdenken en Helen’ (to Commemorate and Heal), a 2023 project on the annual commemoration of slavery in Amsterdam, co-created with memory activists, heritage professionals and scholars. By bringing together our combined experiences, building on expertise in the field of participatory practices and the topic of this cocreative project, we provide a critical reading of the affordance of co-creation when aiming for multivocality, and offer some considerations on how to re-think ideas of co-creation. We argue that a focus on ‘community’ in co-creation risks glossing over existing differences and antagonisms. These ‘undercurrents of co-creation’ – the tidal push and pull beneath the surface –need to be brought into view. We propose to acknowledge that the undercurrents are part of the co-creative process, and to find ways to make them productive.

The Undercurrents of Co-Creation

Through this essay we aim to contribute to a more nuanced and multifaceted understanding of co-creation. We present Herdenken en Helen (to Commemorate and Heal), a 2023 project on the annual commemoration of slavery in Amsterdam, co-created with memory activists, heritage professionals and scholars. By bringing together our experiences, building on expertise in the field of participatory practices and the topic of this co-creative project, we would like to provide a critical reading of the affordance of co-creation when aiming for multivocality, and offer some considerations on how to re-think ideas of co-creation.

Within the art and museum field co-creation is increasingly popular as a way to address challenges institutions have been facing in recent decades. Institutions were pressured to rethink their relevance to wider audiences, and to become more diverse and inclusive both in terms of content and as an institution as such. Though part of a broader framework of participation, the idea of co-creation is often connected to theories of ‘community art’, a term used by British artists in the 1960s who wanted to ‘make “art” that would reach beyond the usual art world audiences. These artists wanted to make art not only for but with those they saw as excluded from the elite world of ‘high art’ (Crehan 2011, 13). In recent decades the idea of participatory work methods and theory have been adopted by museums and heritage institutions and are reflected in strategies and definitions of museum associations like ICOM. It is becoming incorporated into standard curatorial practice as a way of “involving people in the making of anything that those institutions can produce. This could be object interpretation, displays and exhibitions, educational resources, artworks, websites, tours, events or even festivals.”1

Co-creation and participation are concepts now used in such a widespread manner2 that doubts have been raised as to their “performativity” (Chirikure et al. 2010) promoted by the “box ticking expediencies associated with ideas about social inclusiveness” (Watson and Waterton 2010, 1). Stephen Welsh, for example, has recently raised concerns that in some cases co-creation might become a way of branding the museum as much as an emancipatory project (Welsh 2024). Pablo Alejandro Leal characterized participation as “a buzzword in the neoliberal era” (Leal 2007). In co-creative and participatory practice there seems to be a thin line between opening institutions for participation and multivocality, and conscripting the vernacular into the institution, thus potentially glossing over contrasts between multiple voices (Beeksma and De Cesari 2019).

The use of the term ‘community’ plays a central role in this tension between participation and conscription. From the early community art to present day applications in the framework of participation, the idea of community has been coupled to an idea of emancipation. The initial analysis of community artists was that the art world and museums have become elite institutions of ‘high’ art and culture with their own internal logic, language and laws. This was a highly exclusive world that was inaccessible to those without training at recognized institutions, or without the necessary networks in the art world. This situation reproduced racial, gender, and class inequalities, and thus marginalized, for instance, people of colour, women and people from lower-class backgrounds. The community artists wanted to change conventions and practices in the art and museum world by involving people who were marginalized. The emphasis, however, seems to have shifted from addressing exclusion and discrimination to a focus on ‘communities’. Increasingly, ‘community’ now appears as a stable and homogeneous group. Indeed, as Steve Watson and Emma Waterton have argued, “the very notion of ‘community’ seem[s] to have ossified into a set of assumptions and practices that were now rarely examined” (Watson and Waterton 2010, 1). In this view, the community acquires the characteristics of an individual: it is imagined to have a voice, an experience, self-awareness and feelings. It is also associated with attributes such as ‘oppressed’, ‘silenced’, or, conversely, ‘emancipated’.

Here a dilemma emerges. Striving for emancipation and representation is a political process that requires the formation of political subjectivity. That is, in the process of co-creation the ‘community’ must emerge as a subject, and this necessarily requires the selection of a representative body (a spokesperson, a committee, etc.) that speaks for the community.

The trouble is that political subjects are not homogeneous ‘groups’ (Beeksma and De Cesari 2019; Brubaker 2004), but the product of sociopolitical-juridical dynamics (Krause and Schramm 2011). Indeed, initiatives such as the Black Arts Movement or AfriCOBRA ought to be seen as efforts to create a sense of community and a claim to political subjectivity, rather than simply as expressions of an already existing, clearly delineated ‘group’. Moreover, experiences of oppression and exclusion work intersectionally (that is, intersecting divisions of gender, race and class), further complicating notions of community as a stable and bounded entity. This raises questions for central concepts of multivocality, equality, knowledge and empowerment in the co-creative process. Political subjectivity tends to absorb rather than foreground opposing positions within a group. For example, co-creative toolkits may include the step of selecting one partner

“In this view, the community acquires the characteristics of an individual: it is imagined to have a voice, an experience, self-awareness and feelings.”

The Undercurrents of Co-Creation

organization out of a range of “potential partners”.3 The selected partner will be representative of, for instance, the neighbourhood as a whole.

Our experience with Herdenken en Helen (both the research phase and the exhibition itself) shows that it is not possible to think of the people who have been involved in the commemoration of slavery as a ‘community’, let alone one that could be represented by one partner that speaks for all. Instead, as we will show, different, and sometimes opposing, positions exist with regards to commemorating slavery. Absorbing them into one position would not do them justice, and may even violate them. This is what Chantal Mouffe has called “agonistic pluralism”: an understanding of democracy that, in contrast to ‘deliberative democracy’, accepts the existence of an oppositional other, but it “presupposes that the ‘other’ is no longer seen as an enemy to be destroyed, but somebody with whose ideas we are going to struggle but whose right to defend those ideas we will not put into question” (Mouffe 1999, 755). We call this form of ‘agonistic’ dynamics the undercurrents of co-creation, to point to the need to bring into view the tidal push and pull beneath the surface. We propose to acknowledge that the undercurrents are part of the co-creative process, and to find ways to make them productive.

The exhibition Herdenken en Helen

The Dutch government designated the year from July 1, 2023 to July 1, 2024 as a ‘commemorative year for slavery’ (herdenkingsjaar slavernijverleden), and provided more than 12 million Euros for cultural, societal and educational activities. The year was inaugurated by King Willem Alexander’s apologies for the Royal House’s involvement in slavery. It generated heightened attention at transnational, national, and local levels, prompting joint reflection on the history of slavery and its lasting consequences, which many people continue to experience today. Next to the Royal apologies, activities included the launch of a ‘Black Canon’ focusing on the history of enslaved Africans and the rehabilitation of the Surinamese icon Anton de Kom and Curaçaoan resistance fighter Tula by the Dutch government.4 Amsterdam having been one of the most important players in trans-Atlantic slavery (Brandon et al. 2020), the City Council wished to stimulate initiatives addressing this past in the context of the commemorative year. One of these activities was an exhibition about the history of the commemoration of abolition in Amsterdam, Keti Koti (lit. ‘broken chains’). This exhibition was to emphasize the importance of the slavery past, thus giving it a more permanent place in the city’s historical canon. The Council also acted upon a promise made by Prime Minister Mark Rutte when he apologized for the Dutch government's role in trans-Atlantic slavery in December 2022.

The Undercurrents of Co-Creation

There he acknowledged that this apology constituted merely the starting point of a prolonged process of healing: “the most important thing now is that all of the steps we take, we really take together. In conversation, listening with the only intention being: doing justice to the past, healing in the present. A comma, not a full stop.”5 In keeping with this emphasis on healing, the Council wished for the exhibition not only to emphasize slavery’s afterlives in the present, but also wanted it to explore pathways towards healing.

The Council asked Imagine IC, a heritage organization in Amsterdam Zuidoost, to create this exhibition. For 25 years, Imagine IC has served as an open floor for contemporary heritage conversations. Operating out of Amsterdam Zuidoost, Imagine IC is dedicated to the practice of heritage democracy. The organization does this by collaboratively attributing multiple layers of meaning to objects and memories, involving as many different people as possible. Together with their network, Imagine IC reflects on the past in the present in order to imagine the future. Through ongoing conversations Imagine IC seeks to foster a more inclusive and democratic approach to the Amsterdam heritage collection. These conversations can lead to co-created exhibitions or public events as instruments to foster exchange. Over the years, Imagine IC has developed innovative methods, which they actively share with the heritage field at local, national, and international levels (Rana, Willemsen, and Dibbits 2017). It is due to their distinctive approach and accumulated experience that they were commissioned by the City of Amsterdam’s Department of Art & Culture to contribute to the celebration of Keti Koti.

Imagine IC proposed to develop the project in accordance with their own established working tradition, which is rooted in a combination of ethnographic and participatory action research. In order to create a multivocal representation, a working group was formed that could connect with various networks. Through a series of conversations and interviews with people from these networks involved in commemorating slavery the aim was to exchange and gather perspectives, to share the rituals and traditions connected to commemorating slavery, and bring them together in the exhibition. The selected interview approach is always to let the interviewee lead the way, to interfere as little as possible and not to steer the conversation too much.

This research was done by the authors of this essay. Jessica Dikmoet is a freelance journalist, guest editor at Imagine IC and herself involved in organizing the commemoration of slavery at Surinameplein (Amsterdam) on June 30 since the 1990s. Markus Balkenhol is an anthropologist working on colonial heritage and memory at the Meertens Institute. He was pre-