PEDRA PAPEL TESOURA

PEDRA, PAPEL, TESOURA E PÓ

Eu tenho mais recordações do que há em mil anos.

Uma cômoda imensa atulhada de planos, Versos, cartas de amor, romances, escrituras, Com grossos cachos de cabelo entre as faturas, Guarda menos segredos que o meu coração. Baudelaire. Spleen, 77 (tradução de Ivan Junqueira).

STONE, PAPER, SCISSORS AND DUST

I have more memories than if I'd lived a thousand years.

A heavy chest of drawers cluttered with balance-sheets, Processes, love-letters, verses, ballads, And heavy locks of hair enveloped in receipts, Hides fewer secrets than my gloomy brain. Baudelaire. Spleen, 77.

É possível que todos nós já tenhamos deparado, seja na legenda de uma imagem em um livro de história da arte, seja na etiqueta que acompanha uma obra em um museu, com uma datação dupla: costumeiramente, ela indica diferentes informações – pode ser uma estimativa de quando foi criada, a duração de tempo que consumiu, entre idas e vindas, ou ainda quando uma versão original precisou refeita (como, por exemplo, ocorre com alguns trabalhos dos concretistas brasileiros). Tal indicação, a princípio insólita na presente circunstância, serve-nos, contudo, de pretexto para refletirmos sobre as gravuras interferidas realizadas por Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira aqui apresentadas. Afinal, perguntar quando eles começam ou terminam – se faz sentido estabelecer essa diferença – nos contam as suas histórias.

A primeira delas remonta ao período de 1979 a 1989, quando Liliane, morando em Olinda, produz um conjunto de litografias na Oficina Guaianases de Gravura (oficina nascida no ateliê de litografia de João Câmara e que a viria a se tornar, até seu fim em 1995, uma importante experiência de organização

It's possible that we've all encountered, whether in the caption of an image in an art history book or on the label accompanying a work in a museum, a double date: usually, it indicates different information – it could be an estimate of when it was created, the amount of time it took to complete, including revisions, or even when an original version needed to be remade (as, for example, occurs with some works by Brazilian concretists). This indication, initially unusual in the present circumstance, serves, however, as a pretext to reflect on the interfered prints made by Liliane Dardot and Marcelo Silveira presented here. After all, asking when they begin or end – if it makes sense to establish this difference – tells us their stories.

The first of these dates back to the period from 1979 to 1989, when Liliane, living in Olinda, produced a series of lithographs at the Guaianases Engraving Workshop (a workshop born in João Câmara's lithography studio and which would become, until its end in 1995, an important experience of collective organization, promoting the art of engraving, as well as a space for meetings, debates and exchanges between artists). There she met and became friends with the then young artist Marcelo Silveira, also a participant

organização coletiva, promotora da arte da gravura, assim como um espaço de encontros, debates e trocas entre os artistas). Lá ela conhece e se torna amiga do então jovem artista Marcelo Silveira, também participante da Guaianases. Essas gravuras, revisitadas por ambos em 2024, se tornam a matriz de várias interferências executadas alternadamente por eles, resultando em novos trabalhos. O que, a princípio, poderíamos comparar com a gênese de Jump (1980), uma pintura tida como marco do pós-modernismo, fruto de uma inadvertida “colaboração” entre Julian Schnabel e David Salle, no qual uma obra do último é alvo de modificações do primeiro (Schnabel pinta sobre uma metade de um díptico de Salle, além de inverter a sequência dos painéis), ganha nuances: a primeira delas relaciona-se a autoria; se no caso norte-americano um artista se apropriou e se apossou da obra de outro, fazendo-a exclusivamente sua, transformandoa em uma segunda coisa, aqui temos uma diferença importante. As gravuras interferidas nunca deixaram de ser ou de preservar a evidência da obra de Liliane – porque a sua versão original continua presente e tem importância substancial na concepção dos novos trabalhos – e, ao agregarem a si as ações de Marcelo e outras tantas novas da artista, passam a ser outras três coisas e uma só ao mesmo tempo (a saber: o primeiro trabalho de Liliane; o segundo trabalho, resultante das respectivas interferências de Marcelo e dela e o terceiro trabalho que é a coautoria final de ambos).

A discussão sobre a(s) autoria(s) dos trabalhos é somente uma das questões e se, por si só, ela desperta nossa atenção, ao tentarmos decodificar a ação de cada um sobre as gravuras – algumas mais evidentes, que revertem os trabalhos para elementos mais próximos de suas linguagens individuais outras mais sutis, que vão de uma inversão da posição

participant in Guaianases. These engravings, revisited by both in 2024, became the matrix for several interventions executed alternately by them, resulting in new works. What we might initially compare to the genesis of Jump (1980), a painting considered a landmark of postmodernism, the result of an inadvertent "collaboration" between Julian Schnabel and David Salle, in which a work by the latter is modified by the former (Schnabel paints over half of a Salle diptych, in addition to reversing the sequence of the panels), takes on nuances: the first of these relates to authorship; if in the American case an artist appropriated and took possession of another's work, making it exclusively his own, transforming it into a second thing, here we have an important difference. The altered prints never ceased to be or preserve evidence of Liliane's work – because their original version remains present and has substantial importance in the conception of the new works – and, by incorporating Marcelo's actions and many other new ones by the artist, they become three things and one at the same time (namely: Liliane's first work; the second work, resulting from the respective interventions of Marcelo and her; and the third work, which is the final coauthorship of both).

The discussion about the authorship(s) of the works is only one of the issues, and while it alone captures our attention when we try to decode each artist's actions on the prints – some more evident, reversing the works to elements closer to their individual languages, others more subtle, ranging from an inversion of the image's position (from vertical to horizontal, for example) to colorized "retouches" (evoking the brushstroke used during the preparation of the matrix) or collages only identifiable when viewed very closely, such is the way they camouflage themselves –an equally intriguing point they raise is that of recoding an image born to exist in series as something unique.

posição da imagem (da vertical para a horizontal, por exemplo) a “retoques” colorizados (que evocam o tusche em pincel utilizado durante o preparo da matriz) ou colagens só identificáveis quando vistas de muito perto, tal o modo como se camuflam – um ponto igualmente instigante que suscitam é o de recodificar uma imagem nascida para existir em série como algo único.

Surgida no final do século XVIII e difundida universalmente nas décadas seguintes, a litografia (processo de impressão baseado no desenho realizado na superfície de uma pedra) representou uma revolução na indústria gráfica, ao viabilizar tiragens e escalas de imagens maiores do que as obtidas nos processos então correntes. A imagem que chega a nós –como sói na gravura – é desde sempre um fantasma (ela deriva de um desenho feito espelhado sobre a pedra matriz e que durante o processo de gravação primeiro “some” através da ação de ácidos e outras substâncias para depois reaparecer pela aplicação das tintas usadas na impressão). Assim, por excelência, na gravura o original é uma cópia (o que a faz ser um “original” é a sua tiragem), situação ratificada principalmente numa oficina coletiva (como era o caso) em que a necessidade de reaproveitamento da pedra, impõe o apagamento definitivo do desenho, que sobrevive apenas como o seu vestígio / reprodução.

Além disso, o que não é uma exclusividade da técnica, a impressão em cores faz com que, esse mesmo desenho possa resultar em obras variadas (quando se decide, à semelhança das viragens feitas outrora com ampliações de fotografia, imprimi-las em versões de diferentes cores: uma preto e branca, outra sépia, outra ciano e daí em diante), ou, ao contrário, que uma única gravura requisite várias matrizes em diferentes

Emerging at the end of the 18th century and spreading universally in the following decades, lithography (a printing process based on drawings made on the surface of a stone) represented a revolution in the graphic arts industry, enabling print runs and larger image scales than those obtained by thencurrent processes. The image that reaches us – as is typical in engraving – is always a phantom (it derives from a drawing mirrored onto the matrix stone, which during the engraving process first "disappears" through the action of acids and other substances, only to reappear with the application of the inks used in printing). Thus, par excellence, in engraving the original is a copy (what makes it an "original" is its print run), a situation ratified mainly in a collective workshop (as was the case) where the need to reuse the stone imposes the definitive erasure of the drawing, which survives only as its vestige/reproduction.

Furthermore, and this is not exclusive to the technique, color printing means that the same drawing can result in varied works (when, similar to the toning done in the past with photographic enlargements, it is decided to print them in different color versions: one black and white, another sepia, another cyan, and so on), or, conversely, that a single print requires several matrices on different stones (which is a combinatorial process, as in the collages obtained with current interfered prints), or, finally, there is also the possibility of printing the "negative" (that is, the inversion of the black and white tones), so that the drawing exists no less as an index – or, if we want to stay within the vocabulary of printmaking, but changing the connotation of the term, in several matrices – capable of continuously reinventing itself, an element equally recognizable in these recent works, given that the lithographs become matrices for those. The eventual repetition of the same print, cut and recombined, establishes a different approach to serial data, since it shifts from the existing image as

diferentes pedras (o que não deixa de ser um processo combinatório, como nas colagens obtidas com as atuais gravuras interferidas), ou, por fim, há também a possibilidade de se imprimir o “negativo” (isto é, a inversão dons tons de preto e branco), de modo que o desenho exista não menos como um índice – ou, se quisermos nos manter no vocabulário da gravura, mas mudando a conotação do termo, em várias matrizes – capaz de se reinventar continuamente, um elemento igualmente reconhecível nessas obras recentes, dado que as litografias se transformam em matrizes daquelas. A eventual repetição de uma mesma impressão, recortada e recombinada, estabelece uma outra abordagem sobre o dado serial, pois desloca-se da imagem existente como nascida para ser vista como reprodutível para outra que, usando a repetição como estrutura narrativa de uma obra única, cria uma nova dinâmica temporal nela (ou, quando a interferência não passa pelo recorte, mas pela inserção de cores, numa dualidade entre o reprodutível passar a conter em si também um caráter único de cada peça).

born to be seen as reproducible to another that, using repetition as the narrative structure of a unique work, creates a new temporal dynamic within it (or, when the interference does not involve cutting, but the insertion of colors, in a duality where the reproducible also comes to contain within itself a unique character of each piece). •••

“Eu trabalhei dois dias nele [no quadro]”. “Oh, dois dias! É pelo trabalho de dois dias, portanto, que você cobra 200 guineas?”

“Não. Eu as peço pelo conhecimento de uma vida inteira”. Esse diálogo do pintor norte-americano James McNeill Whistler com o advogado contratado pelo crítico John Ruskin, são parte de uma histórica batalha judicial travada entre ambos em 1877. O episódio em si não vem ao caso, sendo para nós preciosa a afirmação do “conhecimento de uma vida inteira” consumado em uma tela pintada em dois dias, se retivermos o argumento do quanto de tempo e experiência vivida há por trás de uma obra. Ao olharmos para a série das gravuras

“I worked on it [the painting] for two days.” “Oh, two days! So you charge 200 guineas for two days’ work?” “No. I ask for a lifetime’s worth of knowledge.” This dialogue between the American painter James McNeill Whistler and the lawyer hired by the critic John Ruskin is part of a historic legal battle fought between them in 1877. The episode itself is not relevant here; what is precious to us is the statement of “a lifetime’s worth of knowledge” accomplished in a canvas painted in two days, if we retain the argument of how much time and lived experience lies behind a work. Looking at the series of interfered engravings, it is not difficult to notice how Liliane and Marcelo freely play with such devices, even subjecting them to analogies with their respective poetics. And here we return to the initial metaphor about dating, given the multiple temporalities involved, if we consider not only when the current works "emerge" (without exaggerating with a "prophecy of the past," would it be between 1979 and 1989? Not because none of them imagined years later carrying out the interventions, but because the works that would potentially result from them "began" at the moment those lithographs materially came into existence?), as well as their revisiting and, no less importantly, the interval between one circumstance and another – which is, in fact, a significant period in the trajectory of both. There are different instances of memory that emerge, and the artists' choice of these works as the object of a collaboration attests

gravuras interferidas, não é difícil notar como Liliane e Marcelo jogam livremente com tais dispositivos, submetendoos, inclusive, a analogias com suas respectivas poéticas. E aqui retornamos a metáfora inicial acerca da datação, dadas as temporalidades múltiplas que os envolvem, se pensarmos não só quando os trabalhos atuais “surgem” (sem cometer o exagero de uma “profecia do passado”, seriam entre 1979 e 1989? Não porque nenhum deles imaginaria anos depois realizar as intervenções, mas porque as obras futuramente resultantes potencialmente “começaram” no momento em que aquelas litografias passam a materialmente existir?), bem como de sua revisitação e, não menos importante, do intervalo havido entre uma circunstância e outra – que é, na verdade, um período significativo da trajetória de ambos. Há diferentes instâncias de memória que emergem, e a escolha desses trabalhos pelos artistas comoobjeto de uma colaboração as atestam: uma primeira está na situação mesma de recolocar – reinventando e, de fato, recriando as obras, ao ponto delas renascerem na mesma proporção em que ressurgem sendo outras, ao saírem da mapoteca –aqueles trabalhos no presente, encarados sob o olhar das histórias primeiras que continham, quão latentes eles se insinuariam (ou não) ao que lhes seguiria, a reflexão sobre o tempo passado remontada nesse reencontro e revisão, instaurando-os novamente na e como atualidade; a segunda instância está no fato deles assimilarem isso através dos vários trabalhos posteriores (incorporando, pois, outras camadas), não só criando novas conexões – eles são alvo de uma nova intenção, ou, se pudermos dizer de outra maneira, são lidos à luz (não exclusivamente retrospectiva) de um vasto repertório de questões e temas que deram os contornos de suas respectivas produções desde então: é, por exemplo, a solidão, registrada em uma gravura original, ao reaparecer

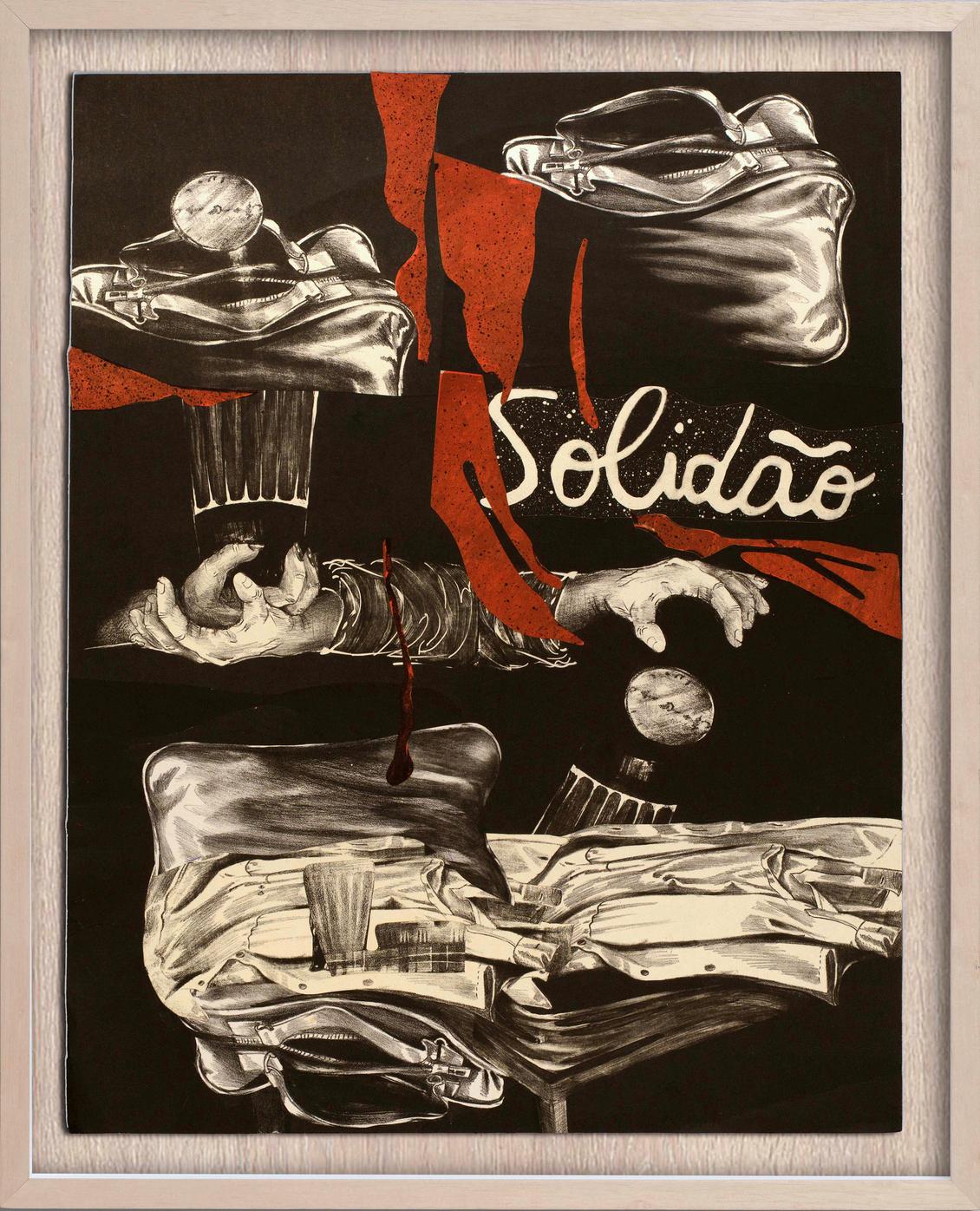

attests to them: a first instance lies in the very act of repositioning – reinventing and, in fact, recreating the works, to the point that they are reborn in the same proportion as they reappear as others, upon leaving the map collection – those works in the present, viewed through the lens of the original stories they contained, how latently they would insinuate themselves (or not) into what would follow them, the reflection on the past time reassembled in this re-encounter and revision, re-establishing them in and as present-day reality; The second instance lies in the fact that they assimilated this through various subsequent works (thus incorporating other layers), not only creating new connections – they are the target of a new intention, or, if we can say it another way, they are read in the light (not exclusively retrospective) of a vast repertoire of issues and themes that have shaped their respective productions since then: it is, for example, solitude, recorded in an original engraving, reappearing both in an interfered reinterpretation and in the "interval" between them, felt in the experience of mourning in Et erat nox (by Liliane) and Hotel Solidão, a book and installation by Marcelo made decades later. Memory, which was a necessary resource in lithography –because, as we have seen, the image temporarily disappears during its execution – transcends the limit of the "theme" and becomes more than a device, a (albeit immaterial) poetic matter that underpins the tone of the interventions. Or, to put it another way, the process of disappearance in lithography is reversed into one of appearances in the interfered works.

Another point of contact constructed a posteriori is revealed between the set of Accumulations of lithographs from the 1970s80s, whether with the visual vocabulary of Revista, by Marcelo, or with the superimpositions of glazes, redesigns and transparencies of the paintings and the series of drawings Mato Dentro, by Liliane (and also in the accumulation and repetition as structuring

reaparecer tanto em uma releitura interferida, quanto no “intervalo” entre elas, sentido na vivência do luto em Et erat nox (de Liliane) e Hotel Solidão, livro e instalação de autoria de Marcelo feitas décadas mais tarde. A memória, que era um recurso necessário na litografia – pois, como vimos, a imagem provisoriamente some durante sua execução – ultrapassa o limite do “tema” e se torna mais do que um dispositivo, uma matéria (conquanto imaterial) poética a revestir a tônica das intervenções. Ou, mudando os termos, o processo de desaparição na litografia se reverte em um de aparições nas obras interferidas.

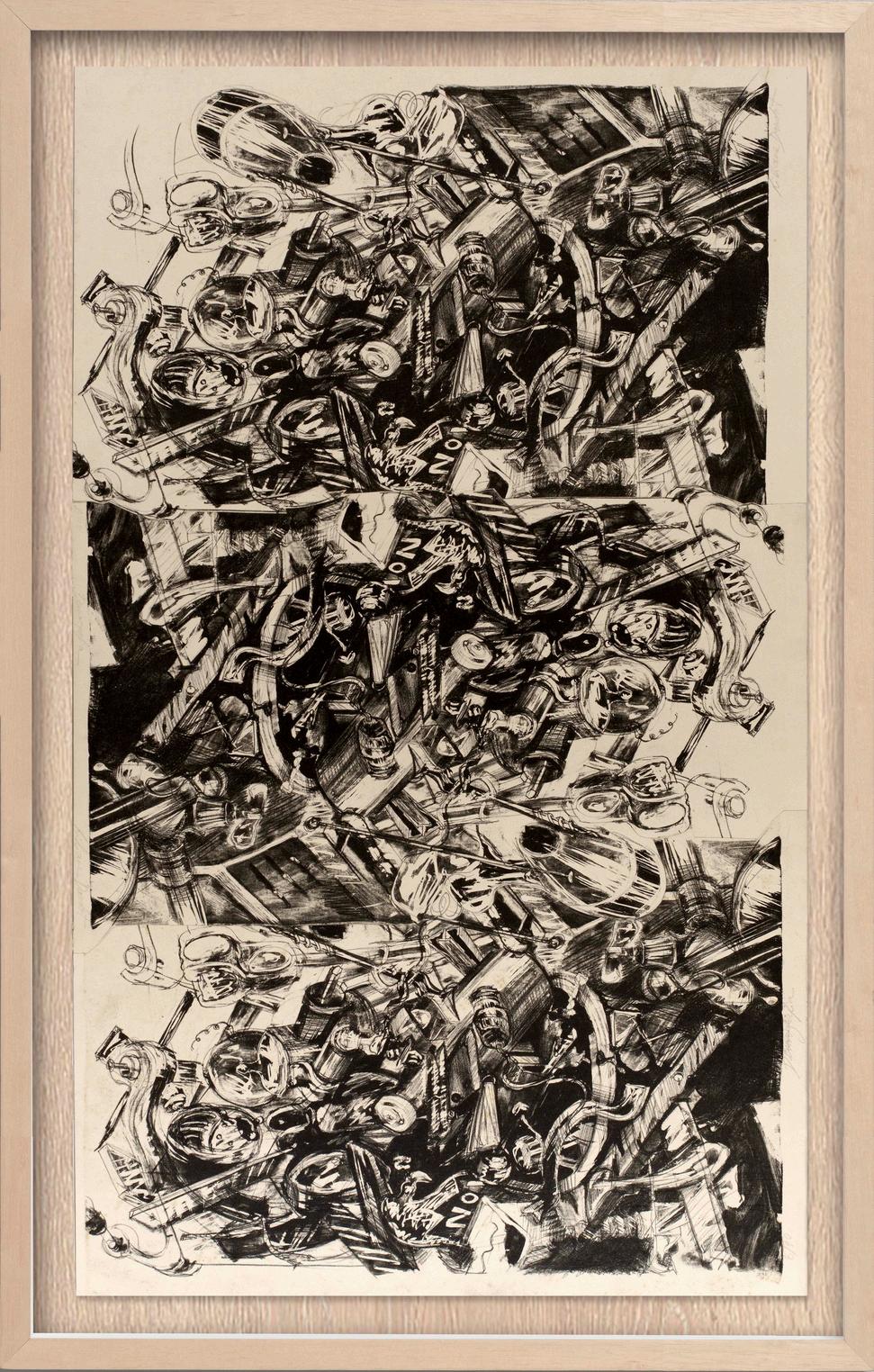

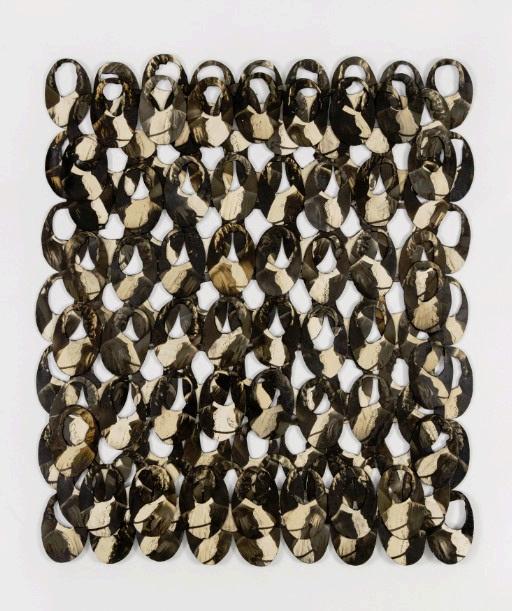

Outro ponto de contato construído a posteriori se revela entre o conjunto de Acumulações das litografias dos anos 1970-80 seja com o vocabulário visual de Revista, de Marcelo, seja com as sobreposições de veladuras, redesenhos e transparências das pinturas e da série de desenhos Mato Dentro, de Liliane (e ainda na acumulação e repetição como fatores estruturantes da escultura / instalação Mandruvá, também de sua autoria, ou o teor de litania inerente ao Manual de Liêdo, do primeiro) e, por fim, no retorno mesmo das acumulações em camadas das obras frutos das intervenções conjuntas (a título de analogia, pensemos quando um músico regrava uma canção sua ou um escritor escreve a sequência de um livro, ao serem situações nas quais a obra se posiciona em um ponto em que ela se torna outra sem renunciar ao que tinha dela mesma). A memória que opera o recorte e junção de fragmentos – que, nesse ponto difere em parte das litografias originais, em que as conexões se assemelhavam mais ao stream of conciousness advindo da simultaneidade do presente – se coloca em Catecismo e Irene, da Alegria a Glória (ambos de Marcelo) como a montagem calculada de uma narrativa que processa, c

structuring factors of the sculpture / installation Mandruvá, also by her, or the litany-like content inherent in the Manual de Liêdo, by the former) and, finally, in the very return of the layered accumulations of the works resulting from the joint interventions (by way of analogy, let us think of when a musician re-records one of his songs or a writer writes the sequel to a book, as these are situations in which the work is positioned at a point where it becomes something else without renouncing what it had of itself).

The memory that operates the cutting and joining of fragments –which, at this point, differs in part from the original lithographs, where the connections more closely resembled the stream of consciousness arising from the simultaneity of the present – is presented in Catechism and Irene, from Joy to Glory (both by Marcelo) as the calculated montage of a narrative that processes, stitches together with a thread a plot on the verge of being lost, ranging from a personal relationship (the religious manuals of the artist's mother) to the story of an anonymous figure and the city of Recife (with the material recovered in the second work). This dynamic of recovery as invention finds its parallel in the process by which the two artists focus on producing the series in co-authorship, which is also an accumulation, montage, and crossing of each artist's memories awakened by that original and the responses engendered therein, with all the evocations they carry with them. What could be seen as an act of hostility (one artist acting upon the work of another, as was often the case with Salle and Schnabel) reveals itself in our case as one of hospitality, considering the receptiveness and permeability of exchanges that unfold during this project, in which, to recall a statement by Lygia Clark, "making two into one multiplies laughter."

Guilherme Bueno

cerze com um fio uma trama à beira de ser perdida, que vai de uma relação pessoal (os manuais religiosos da mãe do artista) à história de uma figura anônima e da cidade de Recife (com o material resgatado no segundo trabalho). Essa dinâmica da recuperação como invenção encontra seu paralelo no processo segundo o qual os dois artistas se debruçam ao produzirem a série em coautoria, que não deixa de ser também uma acumulação, montagem e cruzamento das memórias de cada um despertadas por aquele original e as respostas dali engendradas com todas as evocações que trazem consigo. O que poderia ser um ato de certa hostilidade (um artista agindo sobre o trabalho de outro, como não deixava de acontecer com Salle e Schnabel) revela-se em nosso caso em um de hospitalidade, considerada a receptividade e porosidade de trocas que se desenrolam no transcurso dessa proposta, no qual, para lembrar uma afirmação de Lygia Clark, “fazer de dois um multiplica o rir”.

Guilherme

Bueno

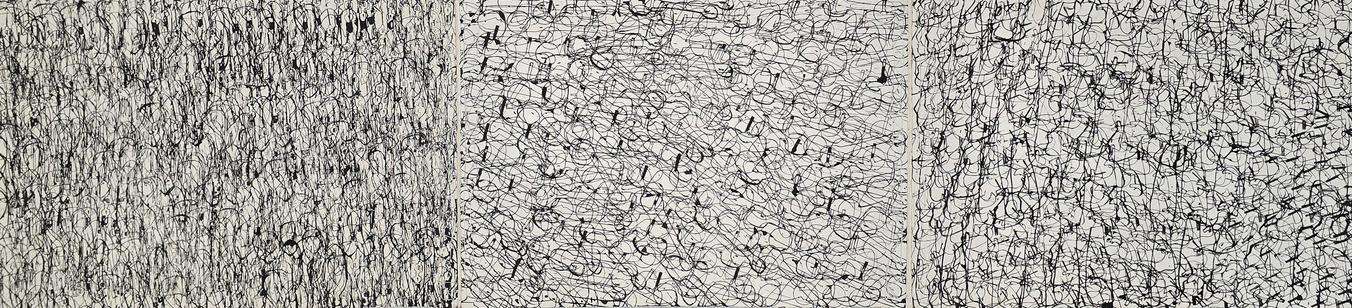

Marcelo Silveira. Irene da Alegria à Glória.

Papel, caneta esferográfica, madeira e CMC. 2 trípticos de 32 x 43 x 4 cm cada. 2017/2018.

Paper, ballpoint pen, wood and CMC. 2 triptychs, each measuring 32 x 43 x 4 cm. 2017/2018.

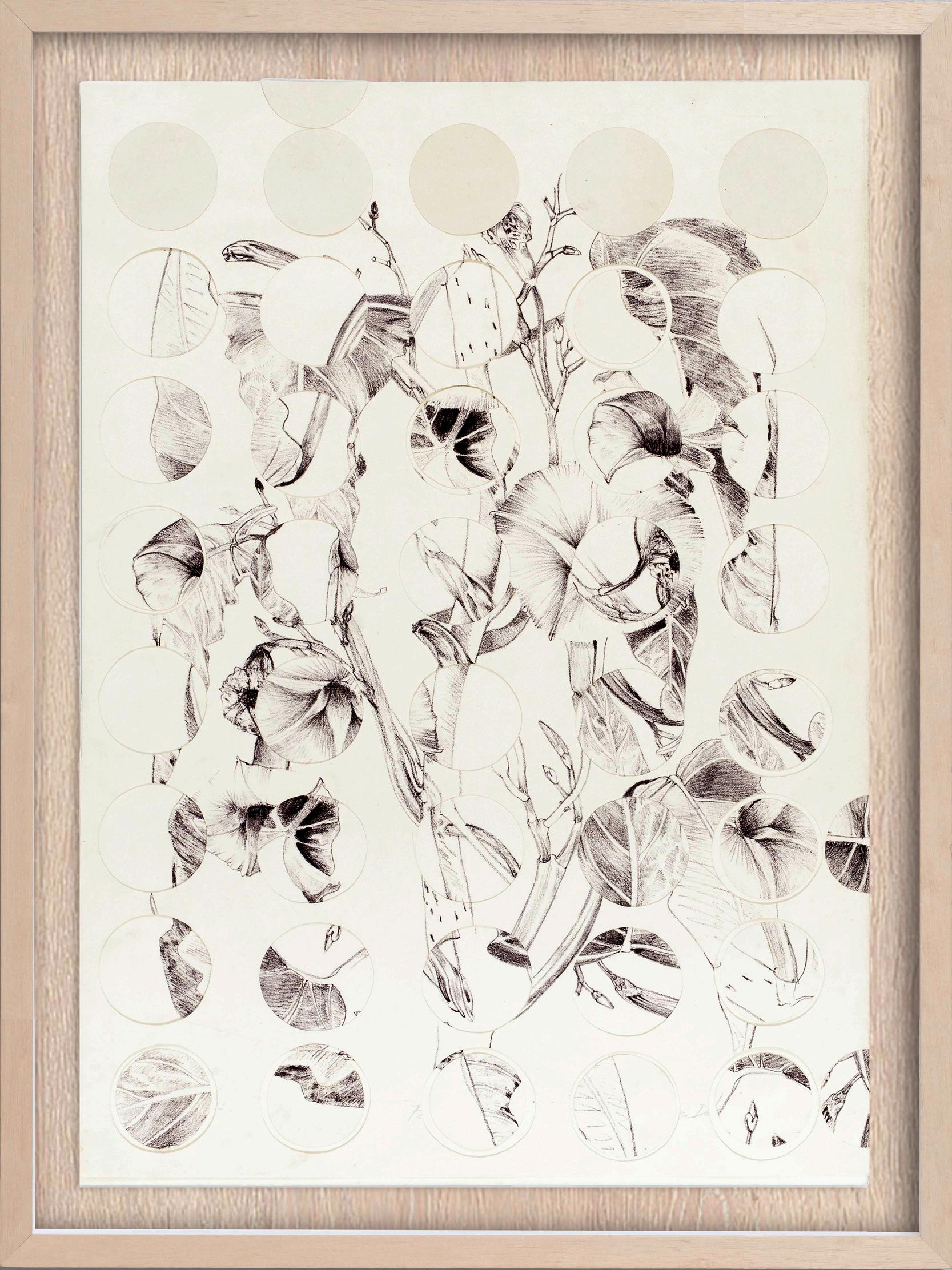

Liliane Dardot. Sem título.

Acrílica, sílica e pigmentos sobre tela. 140 x 220 cm. 2020.

Acrylic, silica and pigments on canvas. 140 x 220 cm. 2020.

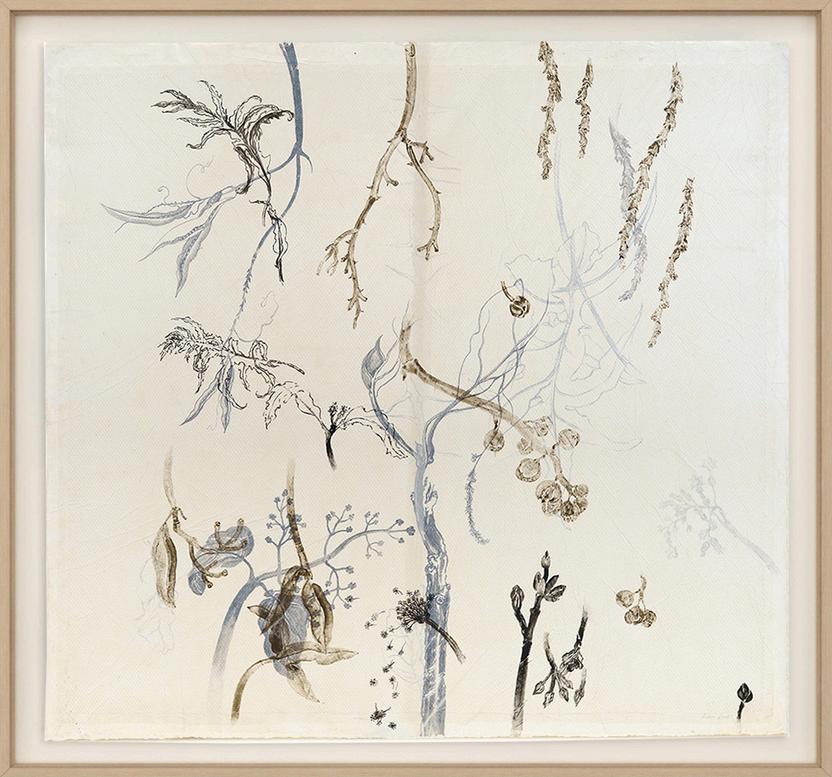

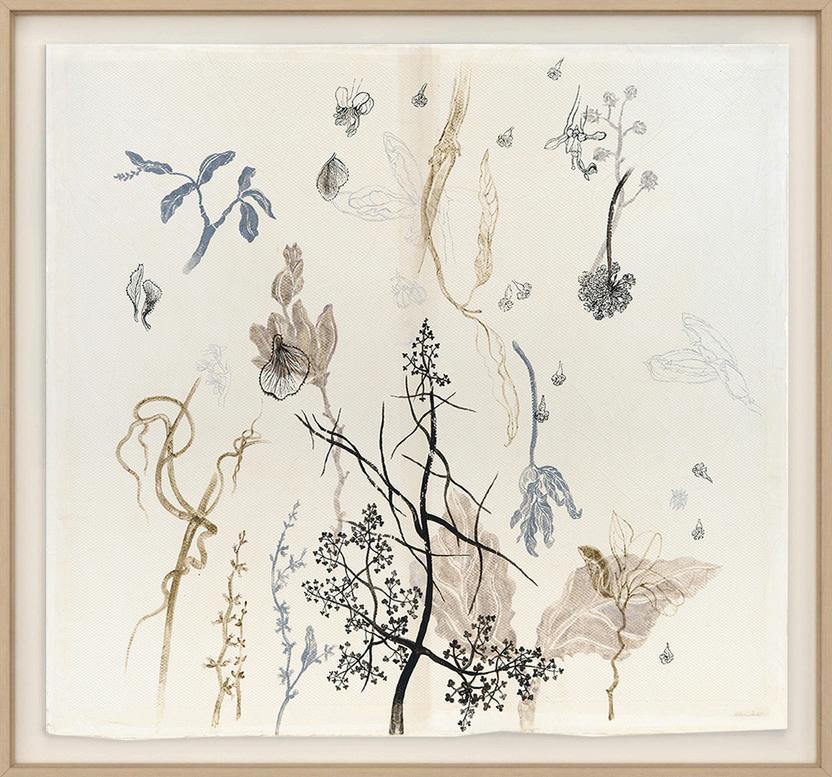

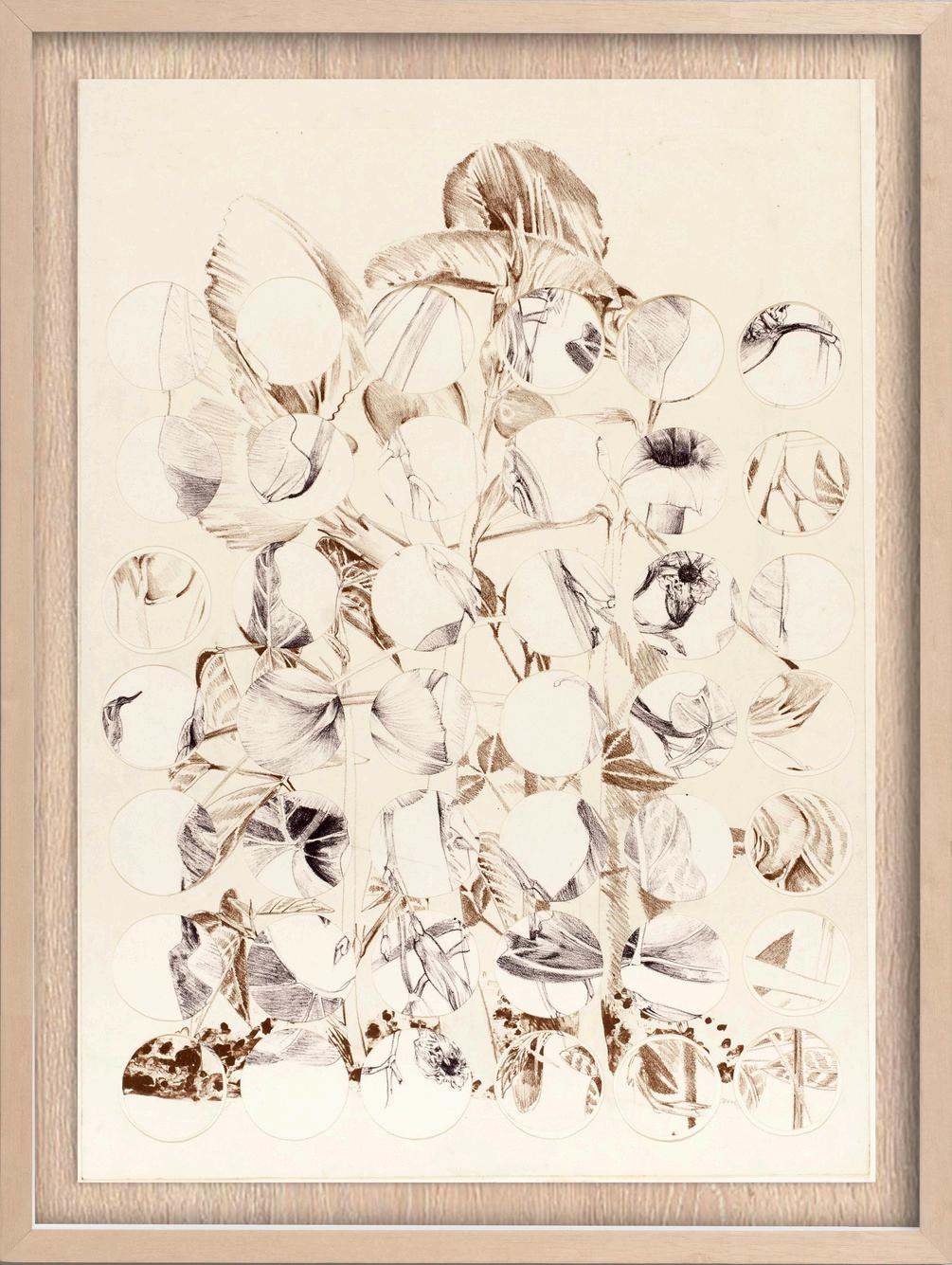

Liliane Dardot. Mato Dentro 4.

Desenhos sobrepostos e intercalados entre várias camadas de papel de seda sobre telinha de nylon, realizados com tinta à base de pigmentos e cinzas em médium acrílico. 134 x 144 cm. 2025.

Overlapping and interspersed drawings between several layers of tissue paper on nylon mesh, made with pigment- and ash-based ink on acrylic medium. 134 x 144 cm. 2025.

Página seguinte / Next page: Mato Dentro 6. Detalhe / Detail.

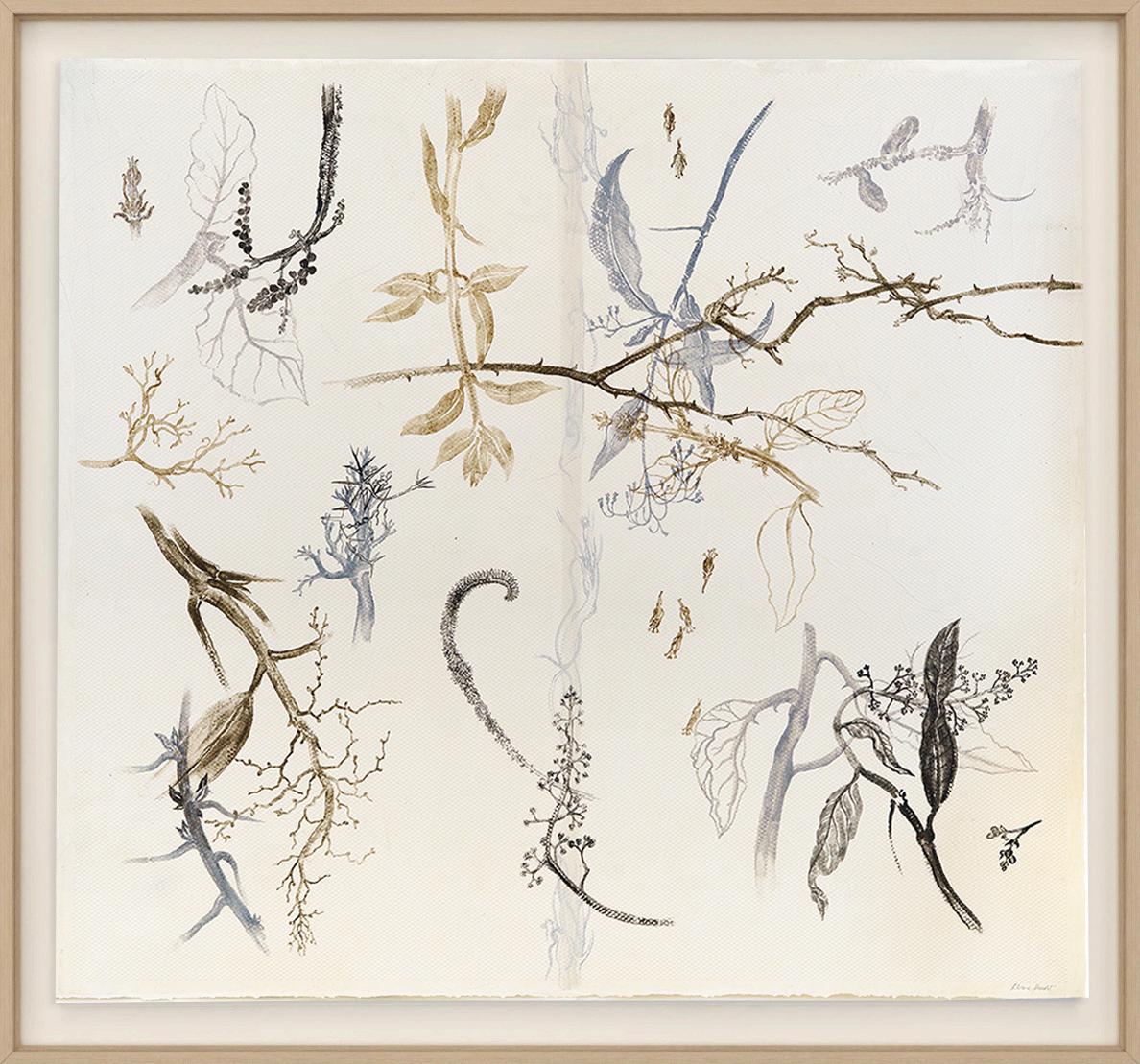

Liliane Dardot. Mato Dentro 2.

Desenhos sobrepostos e intercalados entre várias camadas de papel de seda sobre telinha de nylon, realizados com tinta à base de pigmentos e cinzas em médium acrílico. 134 x 144 cm. 2025.

Overlapping and interspersed drawings between several layers of tissue paper on nylon mesh, made with pigment- and ash-based ink on acrylic medium. 134 x 144 cm. 2025.

Página anterior / Previous page: Mato Dentro 3. Detalhe / Detail.

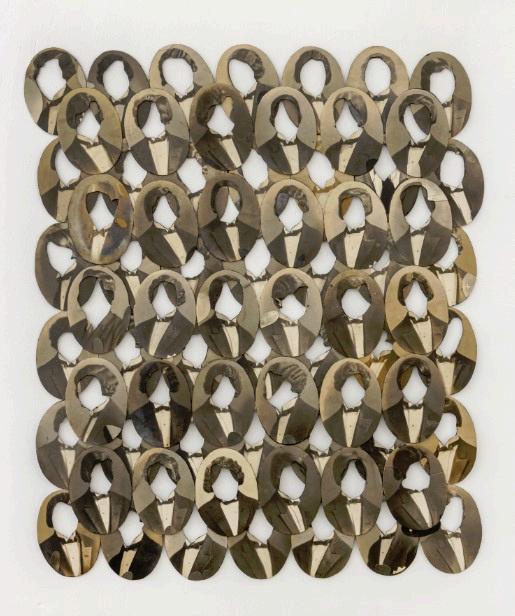

Marcelo Silveira. Catecismo 2. Impressão Fineart.184,5 x 171,5 cm (políptico). 2016.

Fine art print. 184.5 x 171.5 cm (polyptych). 2016.

Photo

x 60 cm. 2019 - 2021.

2019 - 2021.

Marcelo Silveira. Sobre alegria e esquecimento XIII. Colagem de fotografias. 71 x 60 cm.

collage. 71

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. no Bordado. Aplicação sobre litografia. 61 x 80 cm. 1981/2025. Application on lithography. 61 x 80 cm. 1981/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. no Lumiar. Litografia e colagem. 71,5 x 56 cm. 1982/2025. Lithograph and collage. 71.5 x 56 cm. 1982/2025.

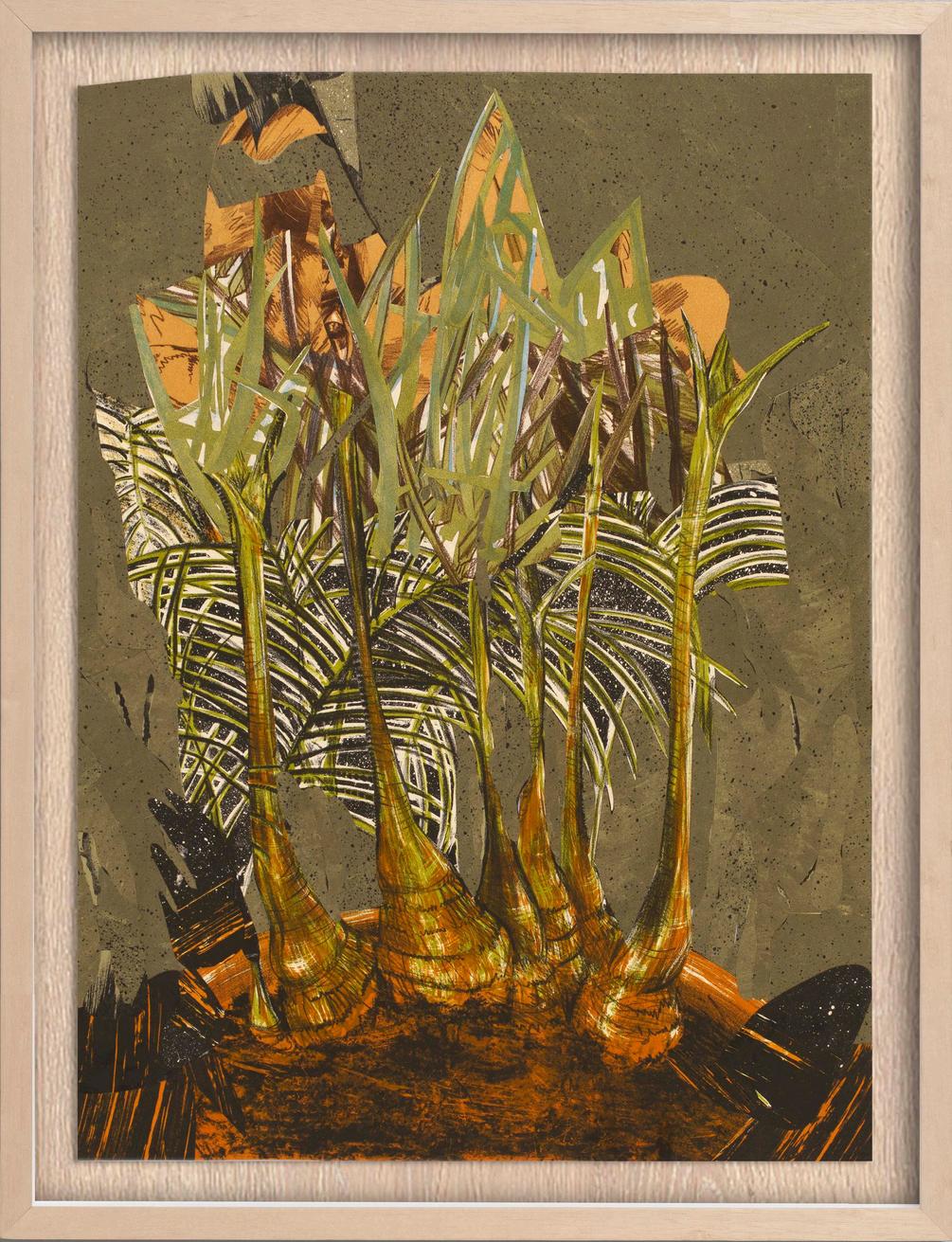

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. da Flor do mato em Secret life. Recorte e sobreposição de litografias. 80 x 61 cm. 1985/2025.

Cut and overlay of lithographs. 80 x 61 cm. 1985/2025

Página seguinte / Next page:

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. na Flor do mato. Detalhe / Detail.

Recorte e sobreposição de litografias. 79 x 60 cm. 1985/2025.

Cut and overlay of lithographs. 80 x 61 cm. 1985/2025

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. no Beijo. Aplicação sobre litografia. 61 x 83 cm. 1981/2025. Application on lithography. 61 x 83 cm. 1981/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. em Solidão. Litografia e colagem. 83 x 67 cm. 1982/2025. Lithograph and collage. 83 x 67 cm. 1982/2025.

73 cm. 1981/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. em Oferenda. Pigmento sobre litografia e colagem. 161 x 73 cm. 1981/2025. Pigment on lithography and collage. 161 x

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. em Arejar, Palmeira e Fiat lux. Litografia e colagem. 42,5 x 90 cm. 1982/2025. Lithograph and collage. 42.5 x 90 cm. 1982/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. no Elétrico e no fluxo do tempo.

Pigmento sobre litografia e colagem. 57 x 122 cm. 1983 e 1988/2025.

Pigment on lithography and collage. 57 x 122. 1983 and 1988/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. da Catemba. Litografia e colagem. 70 x 60 cm. 1986/2025. Lithography and collage. 70 x 60cm. 1986/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. em Corte e Reconstituição. Litografia e colagem. 86 x 99. 1981/2025. Lithograph and collage. 86 x 99. 1981/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. em Insegurança, nos Fragmentos. Litografia e colagem. 96 x 88 cm.1980/2025. Lithograph and collage. 96 x 88. 1980/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. no Terceiro turno. Pigmento sobre litografia. 37 x 52 cm cada (políptico). 1989/2025. Pigment on lithography. 37 x 52 cm each (polyptych). 1989/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. em Reconstituição.

Litografia e colagem. 64,8 x 71,9 cm. 1981/2025.

Lithograph and collage. 64.8 x 71.9 cm. 1981/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. ainda no fluxo do tempo 1.

Pigmento sobre litografia. 52 x 72 cm. 1989/2025.

Pigment on lithography and collage. 52 x 72 cm. 1989/2025.

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira. da Demografia e de Acumular. Litografia e colagem. 98 x 58 cm. 1979/2025.

Lithography and collage. 98 x 58 cm. 1979/2025.

60 x 51 cm. 2019-2021.

Photo collage. 60 x 51 cm. 2019 - 2021.

Marcelo Silveira. Sobre alegria e esquecimento XI. Colagem de fotografias.

Carimbos à nanquim e grafite sobre papéis costurados com linha de algodão. 35 x 150 cm. 2006.

Ink and graphite stamps on paper, stitched with cotton thread. 35 x 150 cm. 2006.

Marcelo Silveira. Caderno de Escritos I.

Marcelo Silveira. Manuais de Liêdo (lote VI).

Madeiras (Cajacatinga) marcadas à fogo. 130 x 220 x 60 cm. 2006

Wood (Cajacatinga) branded with fire. 130 x 220 x 60 cm. 2006

PEDRA PAPEL TESOURA E PÓ

Liliane Dardot e Marcelo Silveira

06 de Dezembro de 2025 a 31 de Janeiro de 2026

December 6, 2025 to January 31, 2026

Albuquerque Contemporânea

Rua Antônio de Albuquerque 885 - Savassi

30112-011, Belo Horizonte - Minas Gerais, Brasil albuquerquecontemporanea.com

ISBN:

Equipe • Team

Flavia Albuquerque

Lucas Albuquerque

Angelita Bauer

Carlos Donato

Cristina Rovesse

Jackson Cardoso

Jade Liz

Julia Zanon

Maria Silva

Raphaella Bauer

Sarah James

Washington Amador

Texto curatorial • Curatorial text: Guilherme Bueno

Fotografias • Photographs: Ícaro Moreno Ramos