Architecture & Modenism & Cinema

‘EL 4 A/B C/COR

‘EL 4 A/B C/COR

MARC6000/6010 Architecture and Total Art

EDITED BY Bo Wen

PROJECT SUPERVISED BY Felix McNamara

Architecture and Cinema

Bibliography

Introduction

This work centers on the theme of "the crisis, death and rebirth of modernism," delving into the complex relationship between architecture and cinema. Through the medium of film, it explores how cinematic language can interpret the overall composition of architecture, as well as how architecture, as both a medium and discipline, can engage in dialogue with the broader fields of art and cinema. Building on this research, the concept of "total art" is examined, emphasizing the multidimensional expression and artistry of architecture.

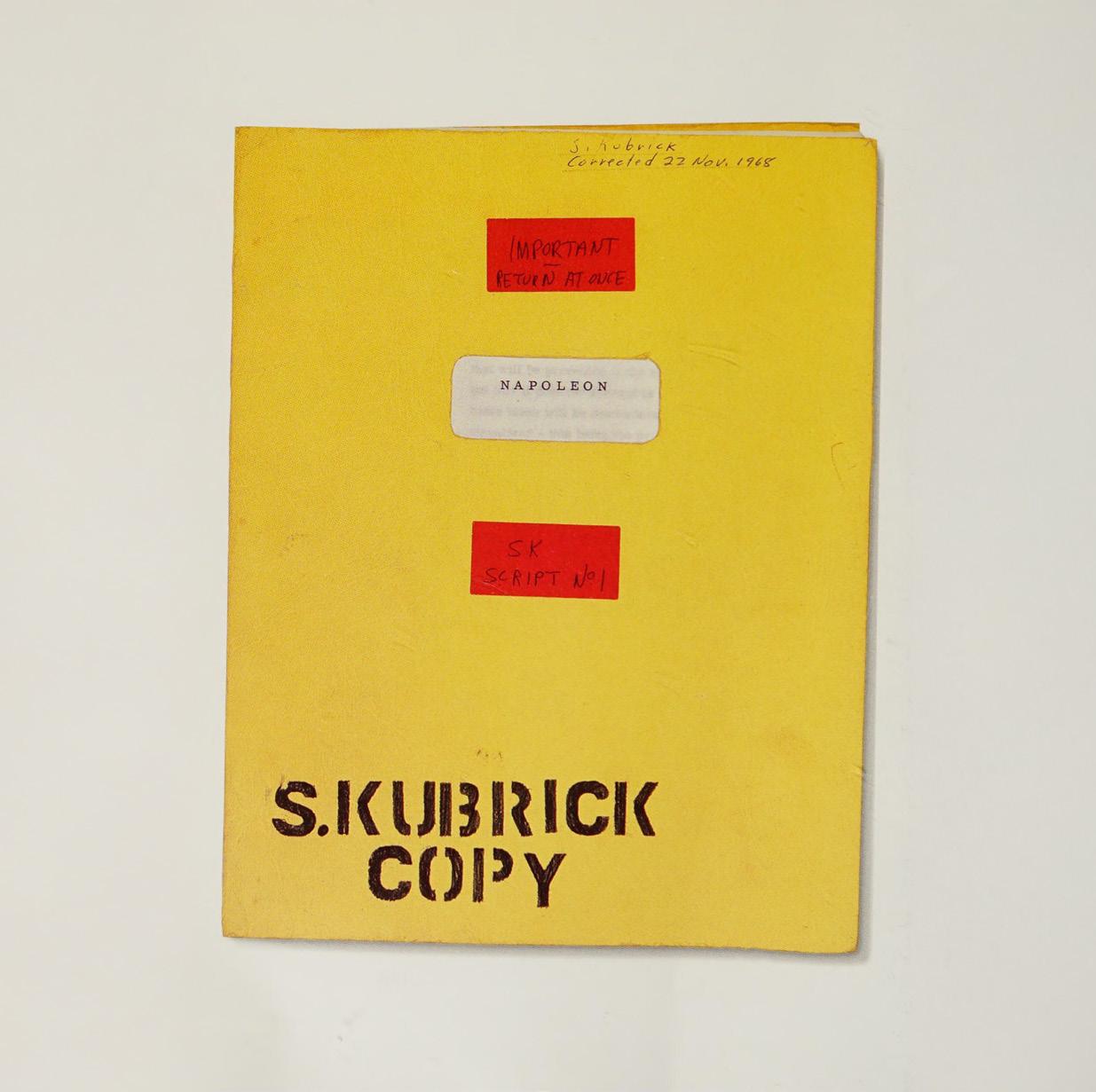

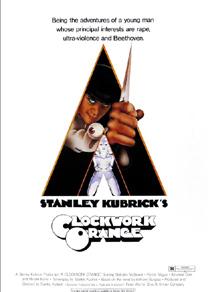

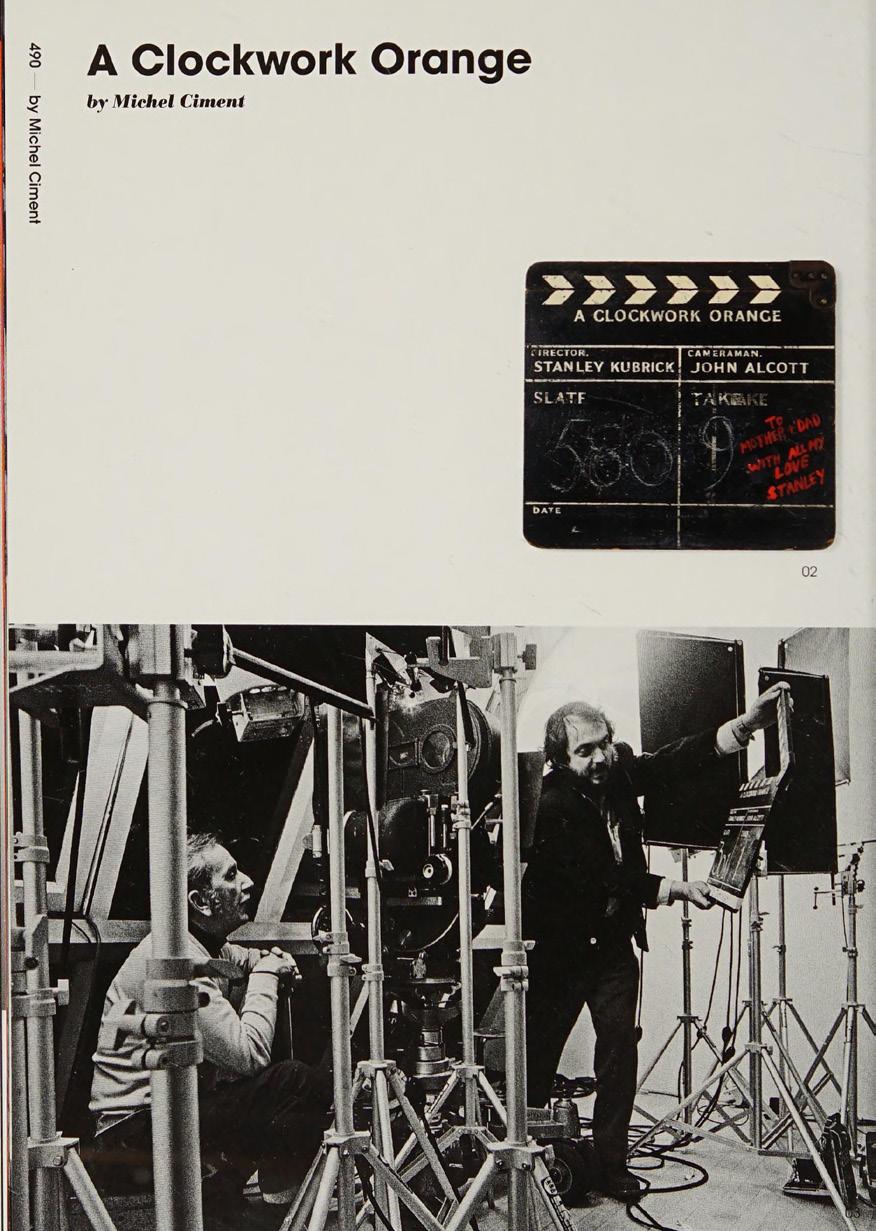

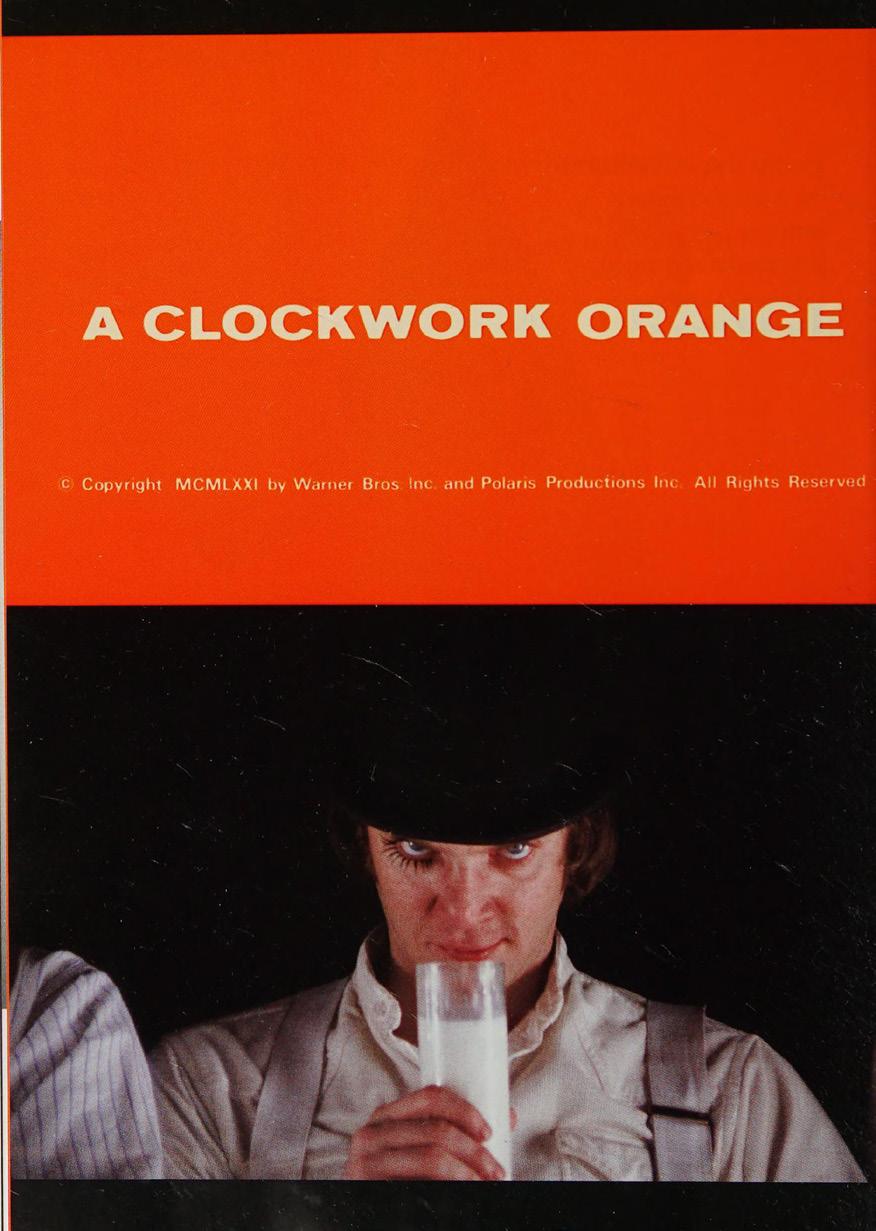

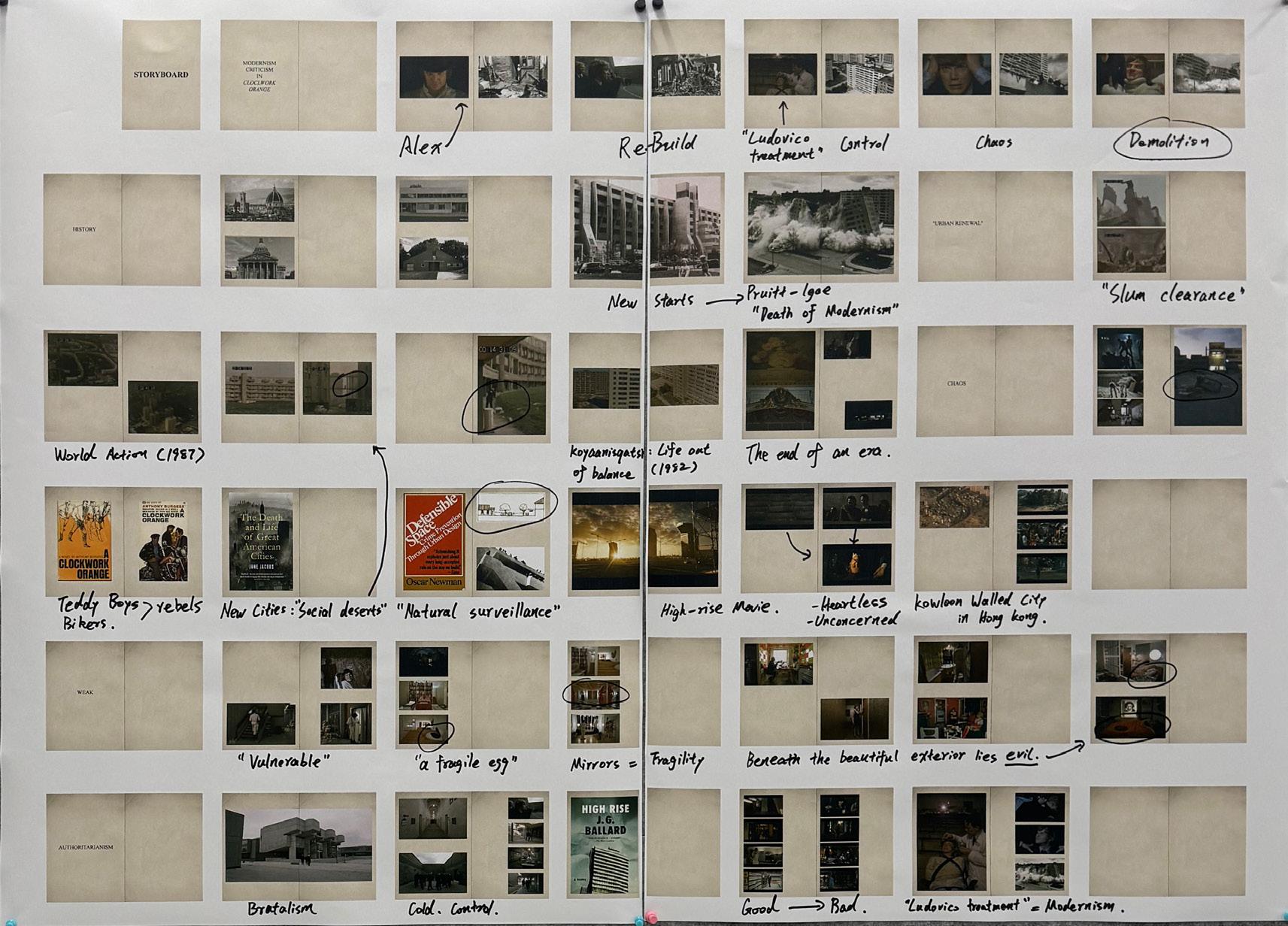

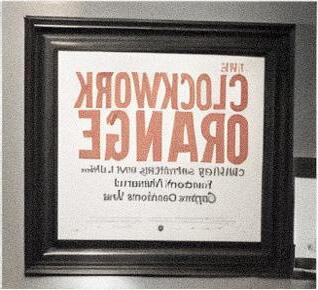

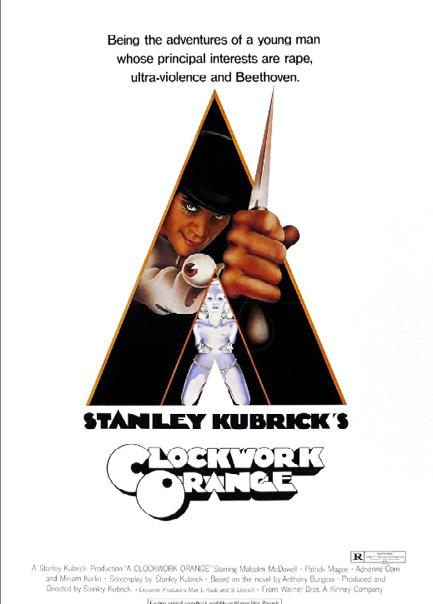

The project begins with an analysis of Stanley Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange. The film reveals social control within modernist architecture through the protagonist’s life experiences and critiques its decline. It serves as an inspiration for the project, which creates a new story by emulating Kubrick's cinematography and narrative style. The story focuses on Icarus’s interactions with architecture at different stages of his life, symbolically representing the rise, decline, and rebirth of modernism. This narrative is presented in the form of a film collage, further highlighting the narrative convergence of cinema and architecture.

The project culminates in a film that gradually diverges from Kubrick’s style during its creation, shifting from a purely critical perspective to a deeper exploration of architectural narratives. The film depicts Icarus’s experiences as a museum janitor, imbuing the architectural space with storytelling. The use of cinematic language extends architectural representation beyond traditional drawings and, through crossdisciplinary dialogue between architecture and film, investigates how cinematographic language can be transformed into architectural aesthetics, thus interpreting the ongoing evolution of modernism.

Overall, this film is not just a reflection on modernist architecture, but also an attempt to interpret its "crisis, death, and rebirth" through a novel perspective, considering it as an in-depth exploration of "total art."

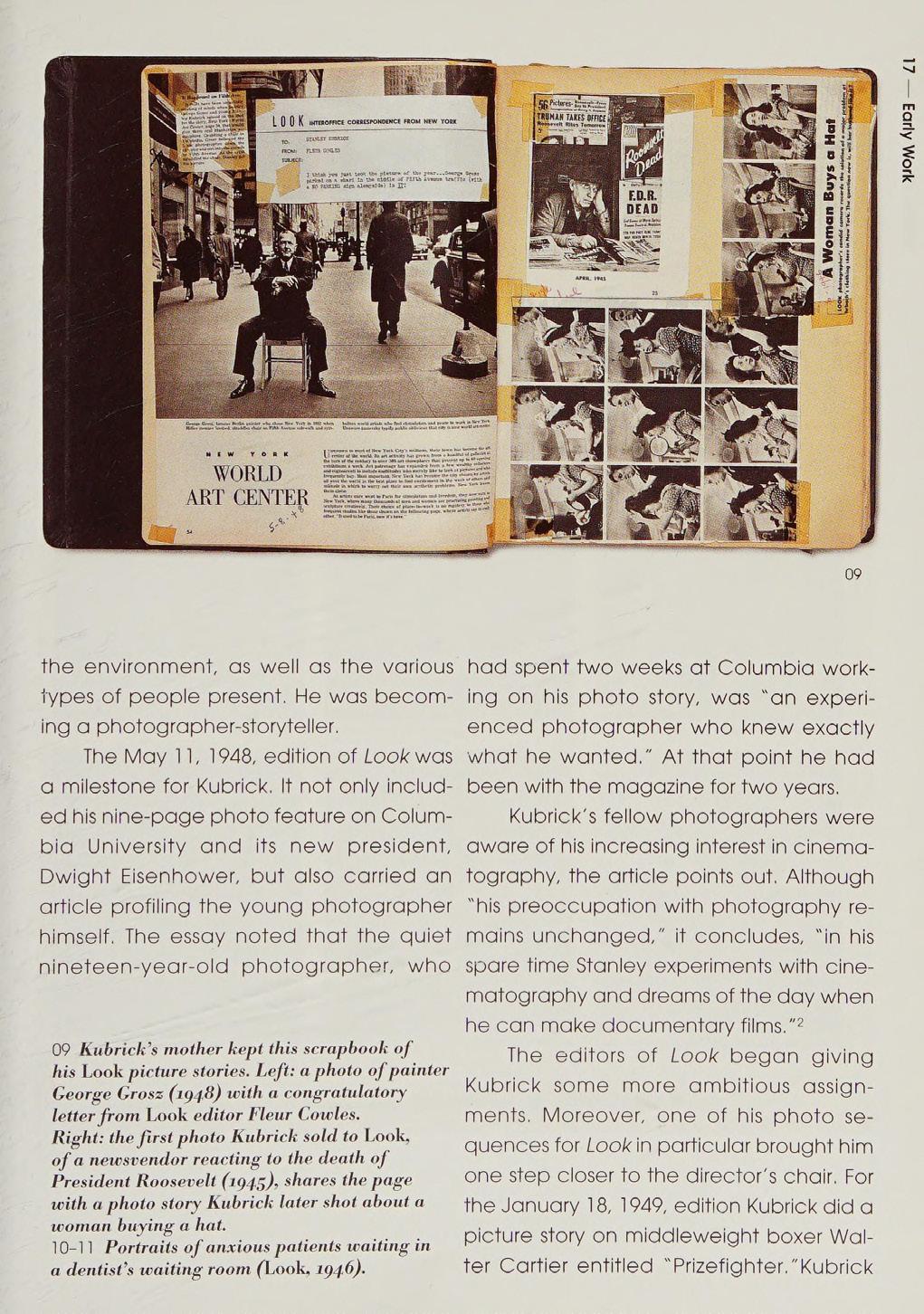

the environment, as well as the various types of people present. He was becoming a photographer-storyteller.

The May 11, 1948, edition of Look was a milestone for Kubrick. If not only included his nine-page photo feature on Columbia University and its new president, Dwight Eisenhower, but also carried an article profiling the young photographer himself. The essay noted that the quiet nineteen-year-old photographer, who

had spent two weeks at Columbia working on his photo story, was “an experienced photographer who knew exactly what he wanted.” At that point he had been with the magazine for two years.

Kubrick’s fellow photographers were aware of his increasing interest in cinematography, the article points out. Although “his preoccupation with photography remains unchanged,” it concludes, “in his spare time Stanley experiments with cinematography and dreams of the day when he can make documentary films. “2

Kubrick's early photography work had a significant influence on the composition of scenes in his later films, as well as his use of light and shadow. Additionally, his ability to convey complex emotions and stories through a single image and capture moments of emotion and dynamism is fully reflected in his film shots.

09 Kubrick’s mother kept this scrapbook of his Look picture stories. Left: a photo of painter George Grosz (1948) with a congratulatory letter from Look editor Fleur Cowles.

Right: the first photo Kubrick sold to Look, of a newsvendor reacting to the death of President Roosevelt (1945), shares the page with a photo story Kubrick later shot about a woman buying a hat.

10-11 Portraits ofanxious patients waiting in a dentist’s waiting room (Look, 1946).

The editors of Look began giving Kubrick some more ambitious assignments. Moreover, one of his photo sequences for Look in particular brought him one step closer to the director’s chair. For the January 18, 1949, edition Kubrick did a picture story on middleweight boxer Walter Cartier entitled “Prizefighter.” Kubrick

Kubrick was renowned for his extreme control and perfectionism in filmmaking, often requiring actors to do multiple retakes to achieve the desired effect. His films are known for their exquisite composition, complex narrative structures, and profound social commentary. Despite sometimes being controversial, his works are considered classics in the history of cinema and have had a profound influence on subsequent directors.

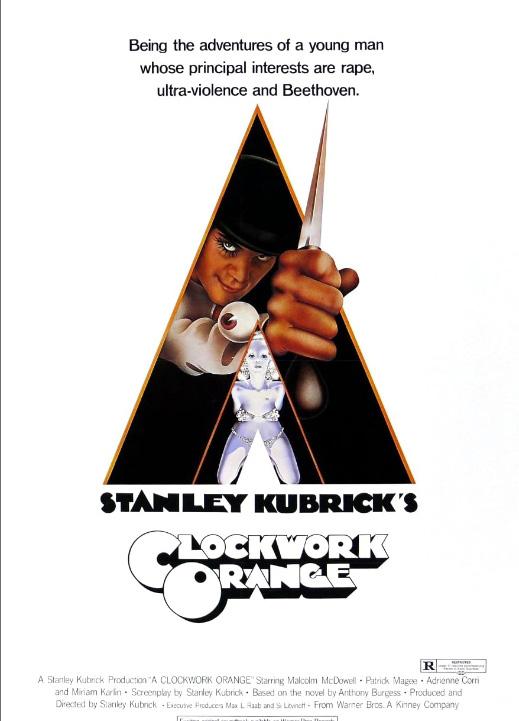

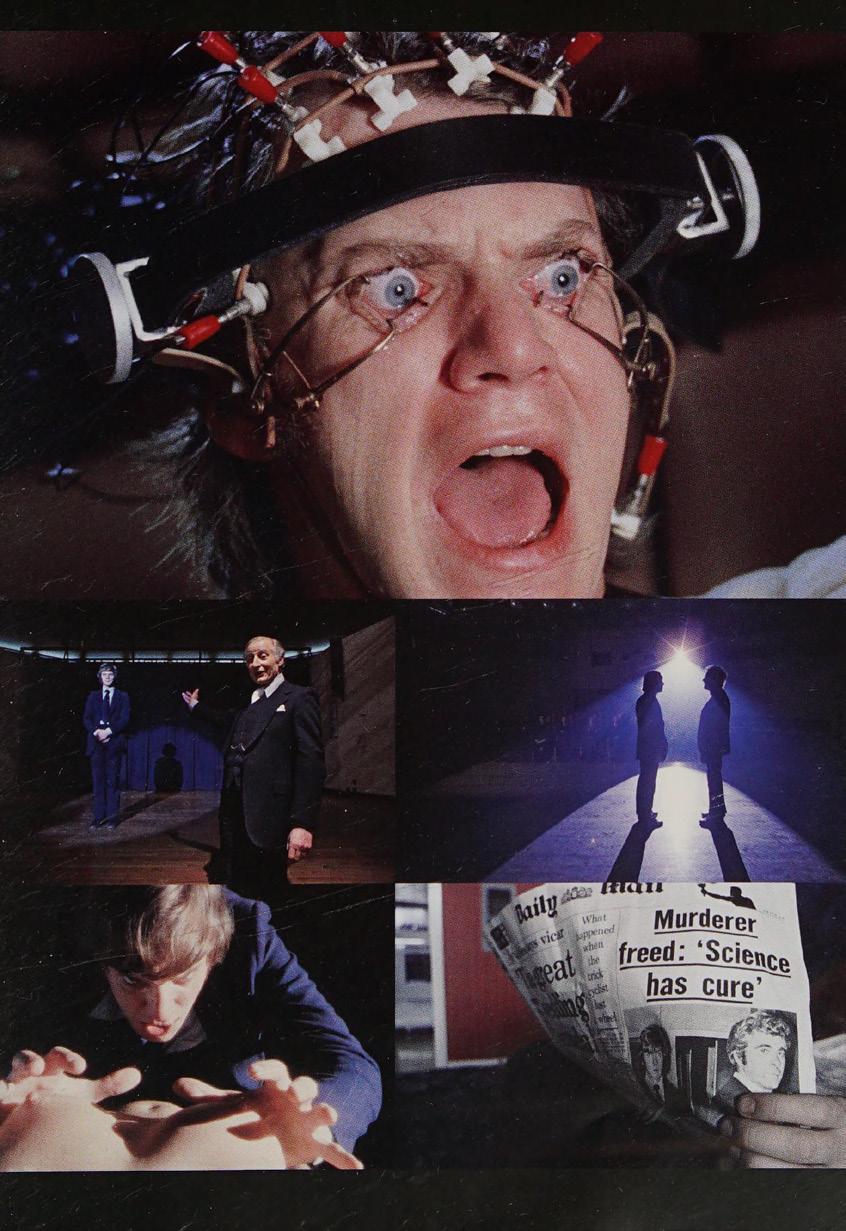

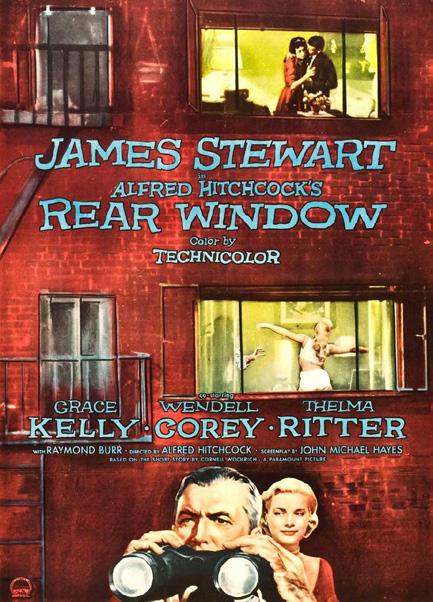

Clockwork Orange is a dystopian science fiction film directed by Stanley Kubrick, based on the novel of the same name by Anthony Burgess.

The film follows a young man named Alex who indulges in violence and crime but is forcibly rehabilitated through an experimental treatment called the "Ludovico Technique" after being captured. After the treatment was successful, he could no longer tolerate violence and music, but the hostility and repression from society did not lessen, ultimately leading him into deeper pain and predicament.

Figure: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stanley_Kubrick

1.4 CLOCKWORK ORANGE

The liberation of thought emphasizes individual value and potential, focuses on human reason and experiential exploration, and opposes the theological dominance of the Middle Ages.

Emphasizing reason and science, opposing superstition and despotism. Advocating for freedom and equality, promoting the ideas of democracy and the rule of law. Architectural style is simple and symmetrical.

To seek rapid post-war development and reconstruction, architecture pursued functionality and simplicity, utilizing new materials and technologies. It aimed for a globally unified architectural style, emphasizing practicality and universal applicability.

The world should be diverse, and ideologies should be decentralized. Opposing the uniformity of modernism, it emphasizes diversity and ornamentation, blending historical elements.

Figure 1: https://www.nannybag.com/zh/guides/florence/12-iconic-florence-landmarksbirthplace-of-the-renaissance

Figure 2: https://heytripster.com/tours/pantheon-paris/

Figure 3: https://forgemind.net/media/le-corbusier-villa-savoye

Figure 4: https://www.archdaily.com/62743/ad-classics-vanna-venturi-house-robert-venturi

Modernism is a product of its time, both an ideology and an artistic style. To efficiently rebuild a post-war society in disarray, it may have been the optimal solution within the context of the global environment at that time and an unavoidable stage of development.

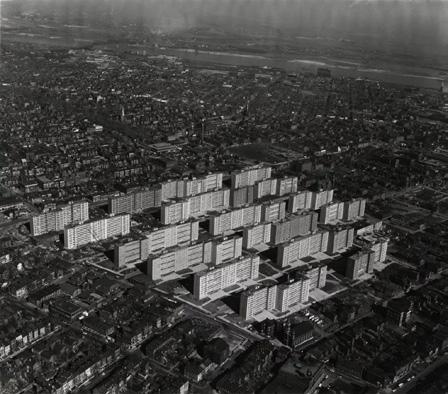

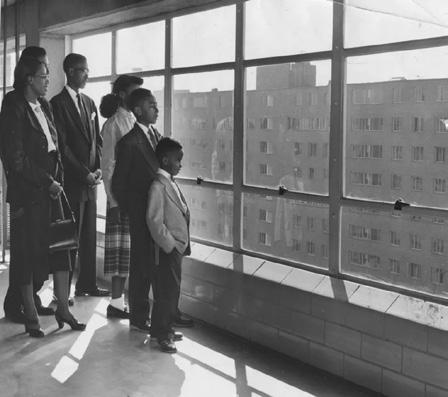

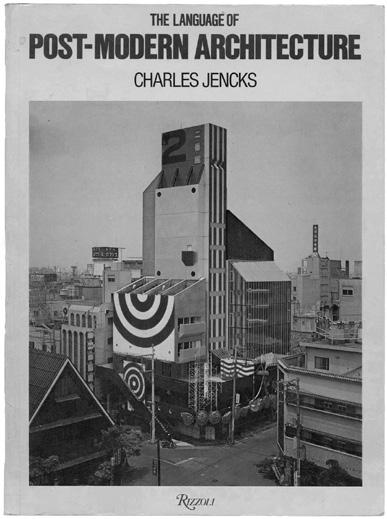

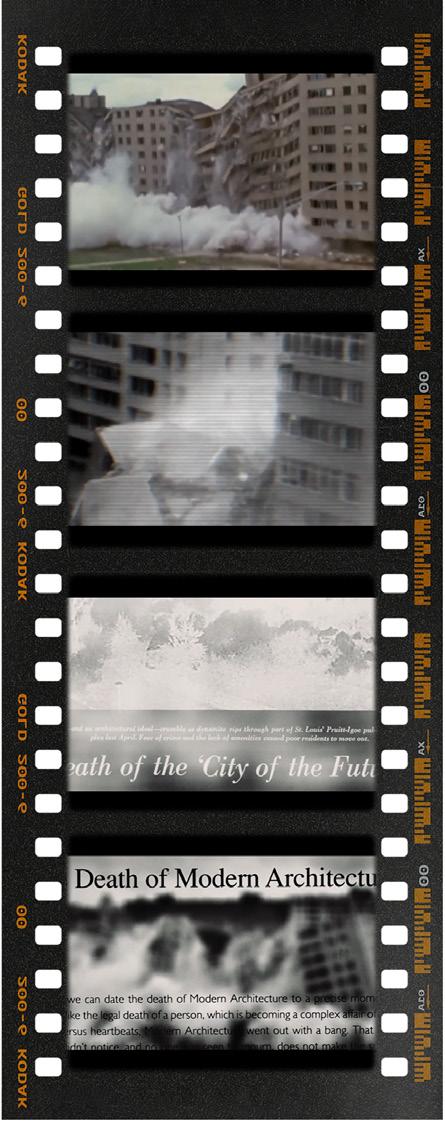

According to Jencks, "Modern architecture met its demise in St. Louis, Missouri, on July 15, 1972, at approximately 3:32 pm, when the infamous Pruitt-Igoe housing project, specifically several of its slab buildings, were finally brought down by dynamite."

The Pruitt-Igoe housing project was a public housing initiative in St. Louis, Missouri, built in 1954 to provide modern living environments for low-income families. The project adopted modernist design principles, including high-rise buildings, open spaces, and functional zoning. However, Pruitt-Igoe quickly encountered numerous problems, such as social isolation, rising crime rates, and insufficient maintenance. Ultimately, in 1972, the government decided to demolish the housing complex.

This project exposed the limitations of modernist architecture in addressing social and cultural complexities.

Figure 1: https://www.jencksfoundation.org/explore/text/writing-from-the-battlefield-charlesjencks-and-the-language-of-post-modern-architecture

Figure 2: https://www.dezeen.com/2022/07/15/modernisms-death-greatly-exaggerated-opinion/

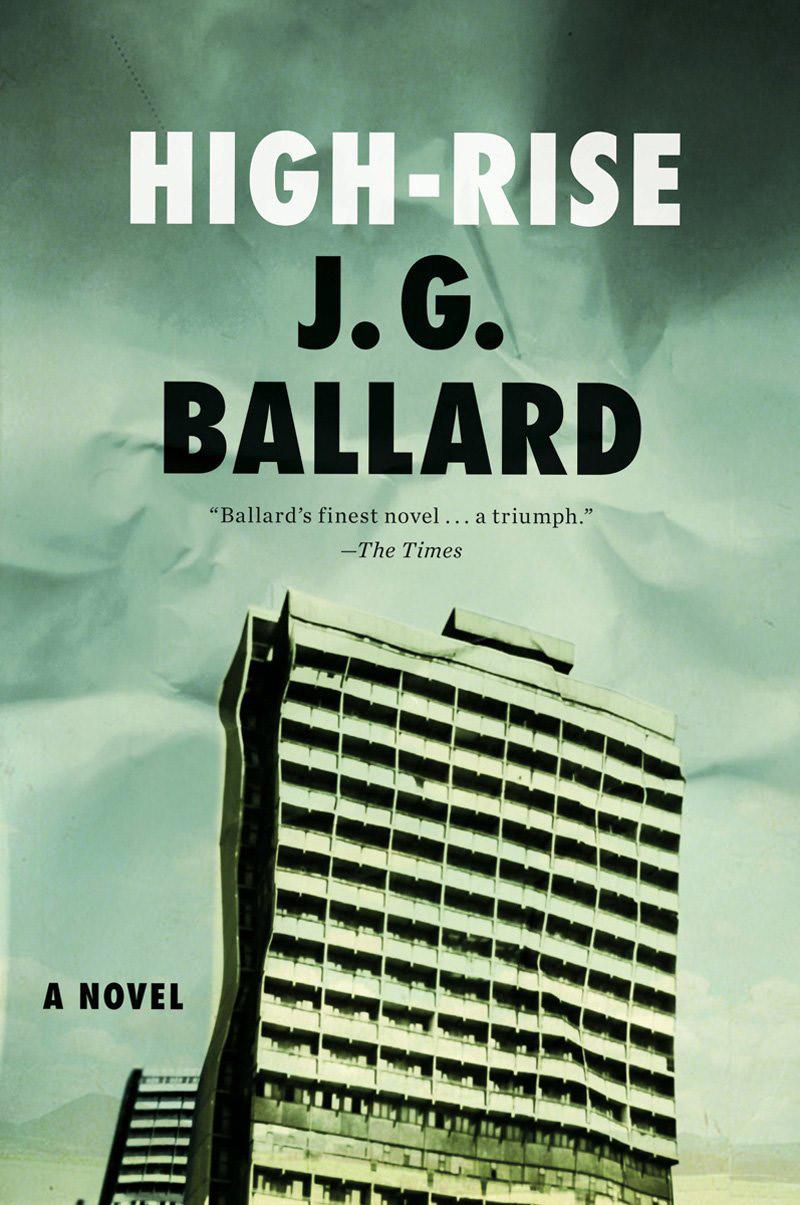

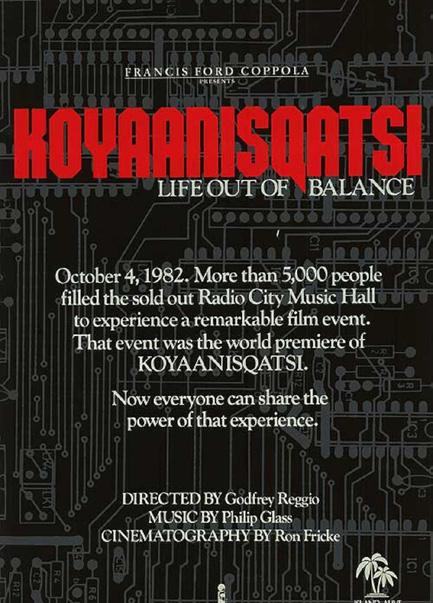

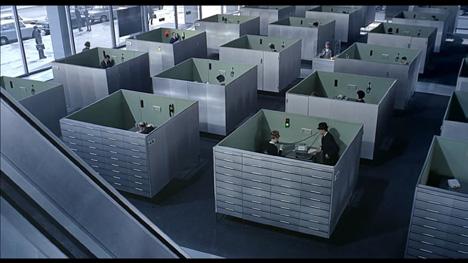

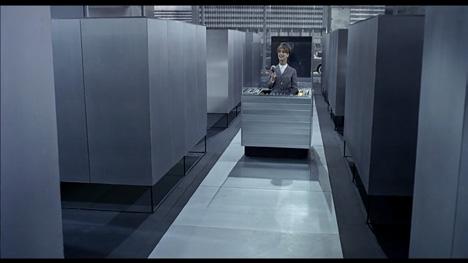

Modernist architecture was once heralded as a symbol of rationality and technological progress, embodying ideals of improved, efficient living through simple geometric forms and functional design. However, works like Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, J.G. Ballard’s High-Rise, and documentaries The World in Action and Koyaanisqatsi reveal how these architectural ideals can reflect tendencies toward social control and authoritarianism. By highlighting the detachment and alienation fostered by modernist spaces, these works critique how utopian ideals can, in reality, become breeding grounds for social decay and disconnection.

In A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick uses the stark, brutalist architecture—concrete facades and enclosed spaces—as symbols of oppression, demonstrating how modernist design can serve as a tool of control and alienation. High-Rise further explores this theme by showing social stratification and breakdown within high-rise living, revealing modernism's weaknesses in dealing with human complexity and social dynamics. Similarly, theories from Jane Jacobs and Oscar Newman expose how modernist architecture disrupts "natural surveillance," with high-rise buildings fostering a sense of alienation from communal spaces.

Through analysis of these films, literary works, and theoretical perspectives, this chapter will explore the complex relationships between modernist architecture, social control, individual freedom, and authoritarianism, exposing the disregard for human diversity and social needs beneath the facade of rational design.

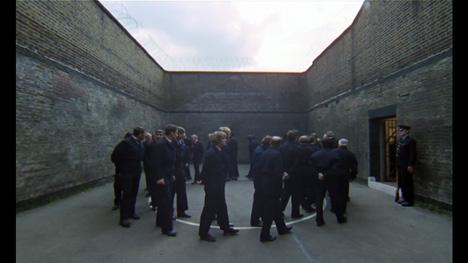

Alex symbolizes the contemporary mainstream perception of the old era: decay and chaos.

The prison’s control represents the post-war authoritarian state, which had the capacity to organize people on a large scale. During this time, architects and planners were granted immense power, and cities began to be managed and politicized like prisoners.

The special treatment Alex undergoes is akin to the process of modernization, attempting to transform the nature of a wicked person into goodness in a manner that is almost brutal and simplistic. This treatment reflects a utopian ideology— overly idealistic, much like modernism itself.

However, this simplistic and violent treatment does not normalize Alex’s life. The complexity of society and human nature leads Alex to a complete breakdown, which is one of the key reasons for modernism's failure. Modernism could not solve all societal problems, nor could it meet everyone’s needs. Its rationality, functionality, and simplicity proved inadequate when confronting real social issues.

In the end, the broken and battered Alex surrenders to authority, once again serving as a metaphor for modernism as a dictator—brutally reshaping the world according to its own perceived correctness.

It is evident that the utopian fantasies of modernism ultimately failed to materialize. A Clockwork Orange, as a dystopian art piece, presciently articulated this outcome. Kubrick, through the film's content and scenes, also showcased the social problems brought about by modernist architecture.

The "modernization" that Alex undergoes is most closely linked to the concept of "slum clearance." This idea was at the core of a 1964 urban renewal campaign in the UK, which aimed to demolish Victorian-era buildings and rebuild cities with modernist architecture. In practice, 1.48 million houses were destroyed, and 3.66 million people were displaced.

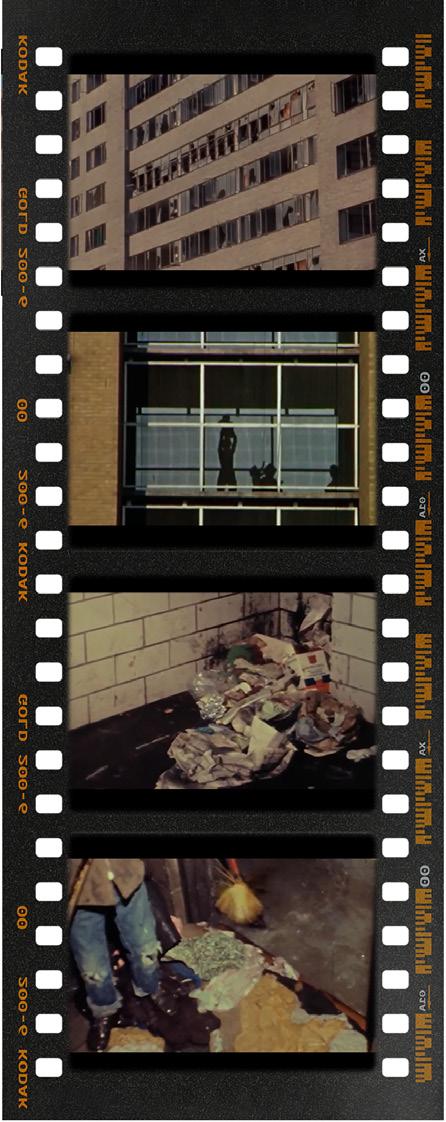

As depicted in the 1978 documentary The World in Action, these low-cost concrete blocks were placed on asphalt roads, where high-density housing replaced once poor but tightly-knit communities.

People were forced to live in vertical buildings, and the ground-level spaces no longer had any connection to them. This meant that sidewalks, tunnels, and streets were no longer under the watchful eyes of residents.

This transformation worsened the urban environment: deserted streets went unmanaged, trash accumulated everywhere, and the streets became breeding grounds for crime.

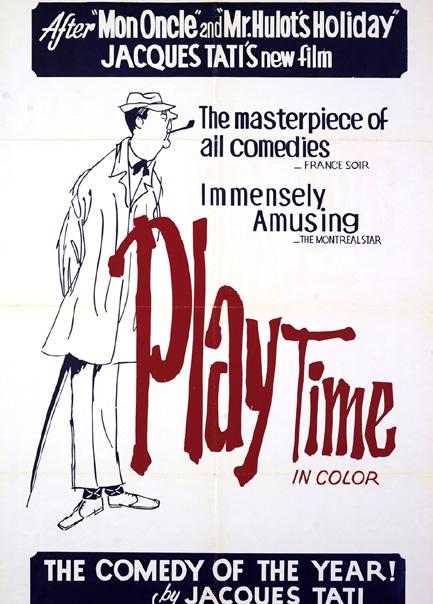

In the documentary Koyaanisqatsi: Life Out of Balance, the camera captures scenes of modernist buildings being destroyed. Through these devastating images, director Godfrey Reggio critiques the breakdown of the balance between modern society and nature, highlighting the negative impacts of urbanization and industrialization on the environment and society. The film uses slow-motion footage combined with music to convey the fragility and disorder of modern architecture, offering a reflection on modernism and suggesting humanity's disruption of the natural order.

In the film, an abandoned theater becomes a symbol of the decline of an older era. This building, which once housed high art, has now degenerated into a place for thugs to commit acts of rape and violence. In this world, the era of operatic art has been replaced by electronic entertainment within apartments—yet another instance of modernism's encroachment.

In the mid-20th century, modernist architecture’s idealized vision reshaped urban landscapes with a cold, rational design language. Initially, modernism sought to improve living conditions and social order through functional buildings and efficient urban planning. Over time, however, modernist cities evolved into "social deserts," with rising homelessness, crime, and unrest. Films like Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, High-Rise, and real-life examples like Kowloon Walled City expose the detachment of modernist planning, where residents in high-rise, closed environments lost natural surveillance and responsibility for public spaces, severing their connection to the urban environment.

Scholars such as Jane Jacobs and Oscar Newman criticized this trend in The Death and Life of Great American Cities and Defensible Space, respectively. Jacobs emphasized how a lack of interaction transformed streets into "social deserts," while Newman revealed the neglect of public spaces. In film, modernist architecture visually symbolizes oppression and control, becoming a backdrop that metaphorically embodies crime and alienation.

The cities created by modernist architecture are filled with decay and deterioration, where uncontrolled streets and tunnels have become gathering spots for street thugs and sites of crime. The city has drifted away from utopian fantasies, straying from the original ideals of modernism.

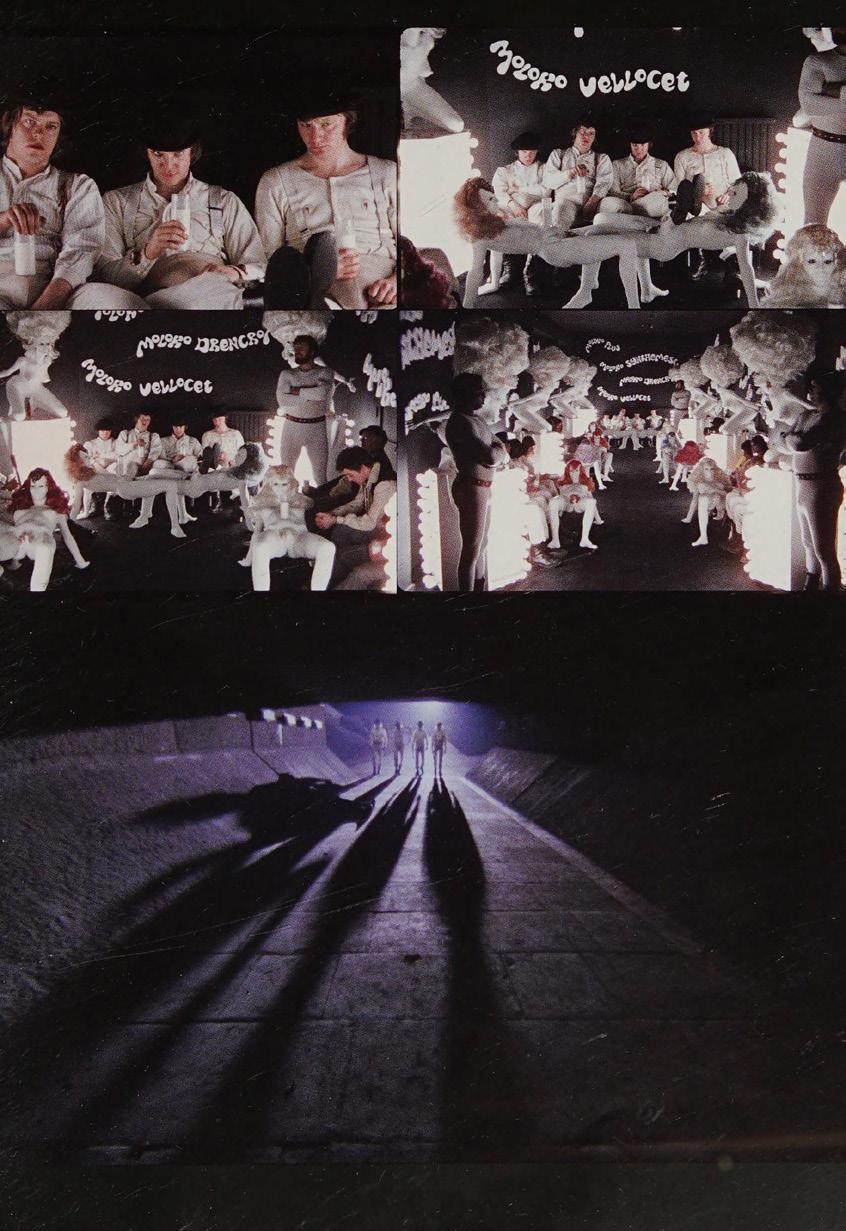

Young people living in these modernist landscapes are often the only ones daring to go out, as depicted in Clockwork Orange. These street thugs roam the streets, engaging in reckless and outrageous acts. One of the most iconic scenes in film history is when they brutally beat a homeless man in a tunnel, a moment that starkly illustrates the lawlessness and violence permeating these urban environments.

The youth culture of the time was rebellious and anti-government. The inspiration for Clockwork Orange is said to have come from the Teddy Boys, a group of street thugs with a menacing aura. Whether it was the Mods, the bikers, or other rebels, they eagerly took to the streets designed under modernist planning. While the rise of these criminals was more a result of the era, prevailing ideologies, and the political system, modernist cities inadvertently provided them with lawless spaces that became breeding grounds for crime. As people moved into high-rise buildings, the streets were left vacant, neglected, and unregulated.

Looking at the pre-release cover designs for A Clockwork Orange, a series of stylish depictions of urban thugs was created, capturing the essence of these downtown rebels.

In 1961, Jane Jacobs' The Death and Life of Great American Cities offered a profound critique of the impact of central planning on urban environments. Her research revealed that in areas without central planning, although there was often a bustling, noisy street life, there were always people present. In contrast, the newly planned cities gave rise to the phenomenon of "social deserts" devoid of pedestrians. These modernist cities witnessed citizens driving from one building to another. "When they need to shop, they drive to a shopping center and park," Jacobs wrote¹ .

The result was that urban streets were abandoned by the citizens, leaving them to vagrants, criminals, and troublemakers.

In 1971, Oscar Newman's Defensible Space, submitted to the U.S. Department of Housing, presented a darker perspective compared to The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Newman was similarly concerned with urban issues, observing that the spaces surrounding high-rise buildings were not like the private gardens of the past but were accessible to everyone rather than being assigned to specific buildings. As a result, residents felt little connection or responsibility toward these spaces, and their connection to public areas diminished as well¹

Residents of high-rise buildings seemed to live in an alienated environment where the streets did not belong to them—only their apartments did. Through vertical housing, modernist planners disrupted the primal territorial instincts of humans, often referred to as "natural surveillance." Consequently, these residents felt neither the right nor the obligation to exert control over the surrounding spaces. The outcome was that only authorities like the police and government had control over these areas, while residents chose to ignore or even become indifferent to them.

1. Newman 1972

Figure 1: https://www.udg.org.uk/publications/udlibrary/defensible-space-crime-prevention-through-urban-design

Figure 2: https://www.slideshare.net/slideshow/crime-prevention-through-environmental-design-1/167240315#17

Figure 3: https://www.ignant.com/2016/04/04/the-secret-history-of-londons-isokon-building/

The film High-Rise also portrays this indifference through its visual storytelling. When someone jumps to their death, the residents of the upper floors merely watch from above with a detached, almost voyeuristic curiosity. This aloof behavior reflects their belief that what happens on the ground below is not their concern but rather the responsibility of the police, since the ground is outside their natural surveillance range. The film uses its imagery to magnify the physical isolation created by modernist architecture, heightening the sense of anxiety over defensible space.

In the 2024 gangster film Twilight of the Warriors: Walled In, directed by Soi Cheang, the infamous British colonial-era architecture of Kowloon Walled City in Hong Kong serves as the backdrop, depicting the dark social realities of 1980s Hong Kong. These buildings became breeding grounds for crime, a lawless area beyond the reach of the police. The modernist architecture in these films acts like a protective shield for evil, erecting a wall of darkness. It’s evident that modernist architecture has become an indispensable "background" for portraying crime in many films, serving as a director’s most direct tool for illustrating evil.

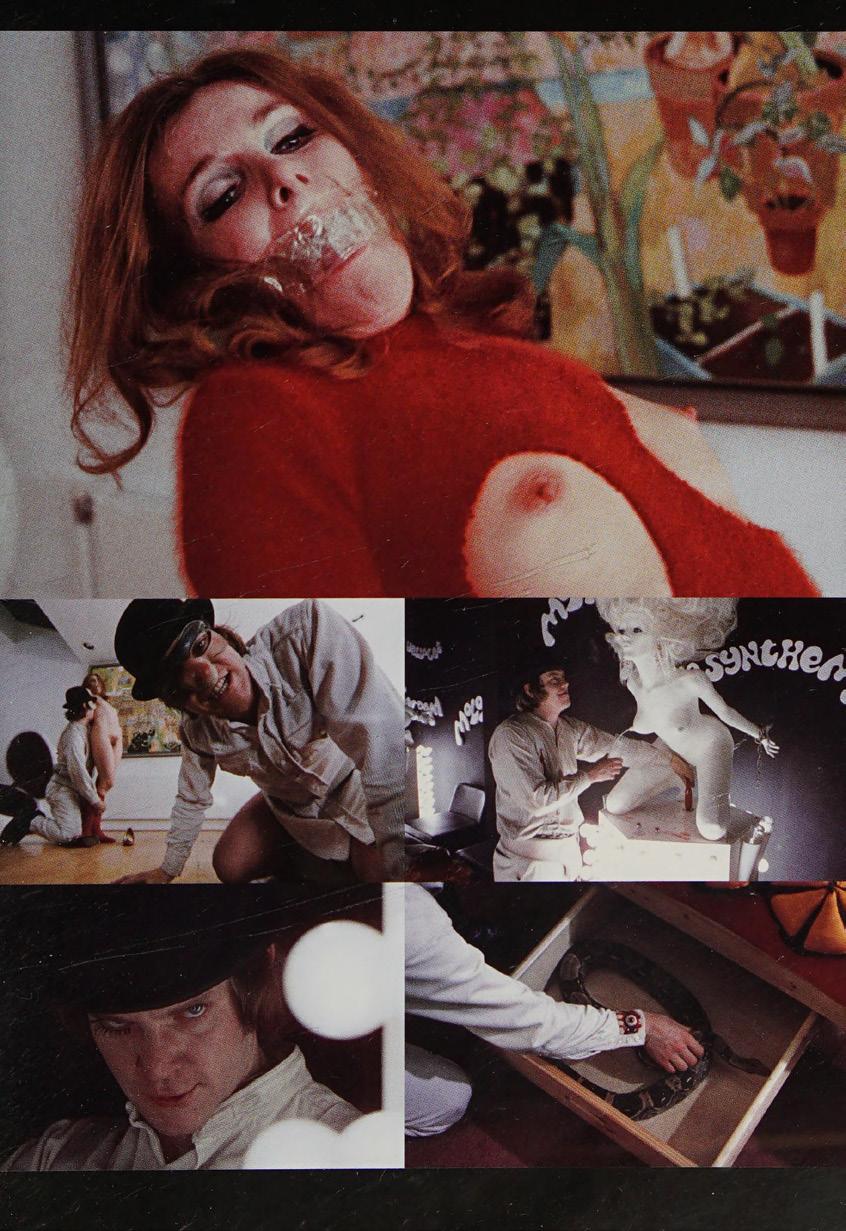

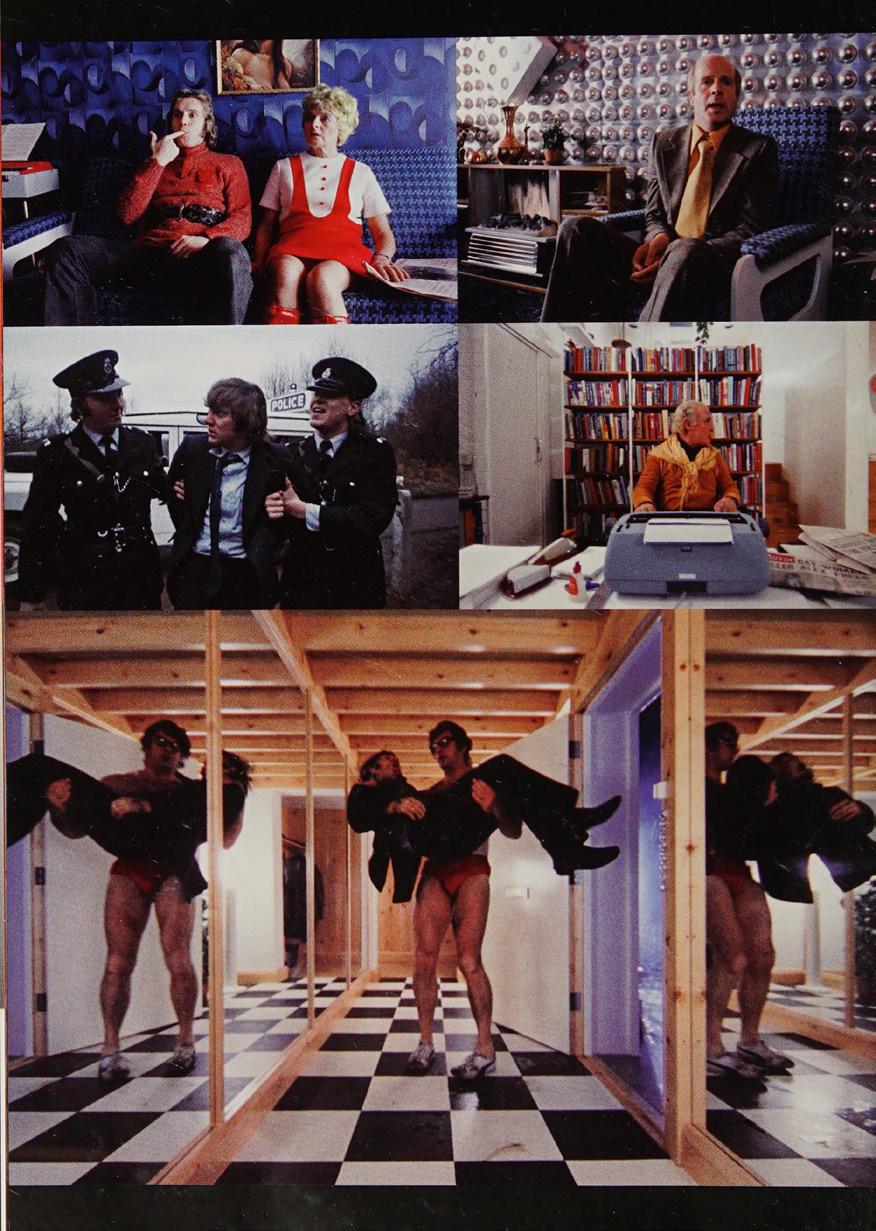

In modernist architectural theory, order and rationality were seen as keys to creating a better society. However, Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange reveals the fragility of this ideal. Through visual details and spatial setups, the film highlights contradictions between the apparent solidity of buildings and their inner weakness. Scenes of vandalized public spaces and defaced murals suggest modernism’s failure to protect human freedom and dignity. Kubrick’s use of contrasting visuals underscores the helplessness of modernist spaces against violence, exposing the limitations of modernism when faced with social complexity.

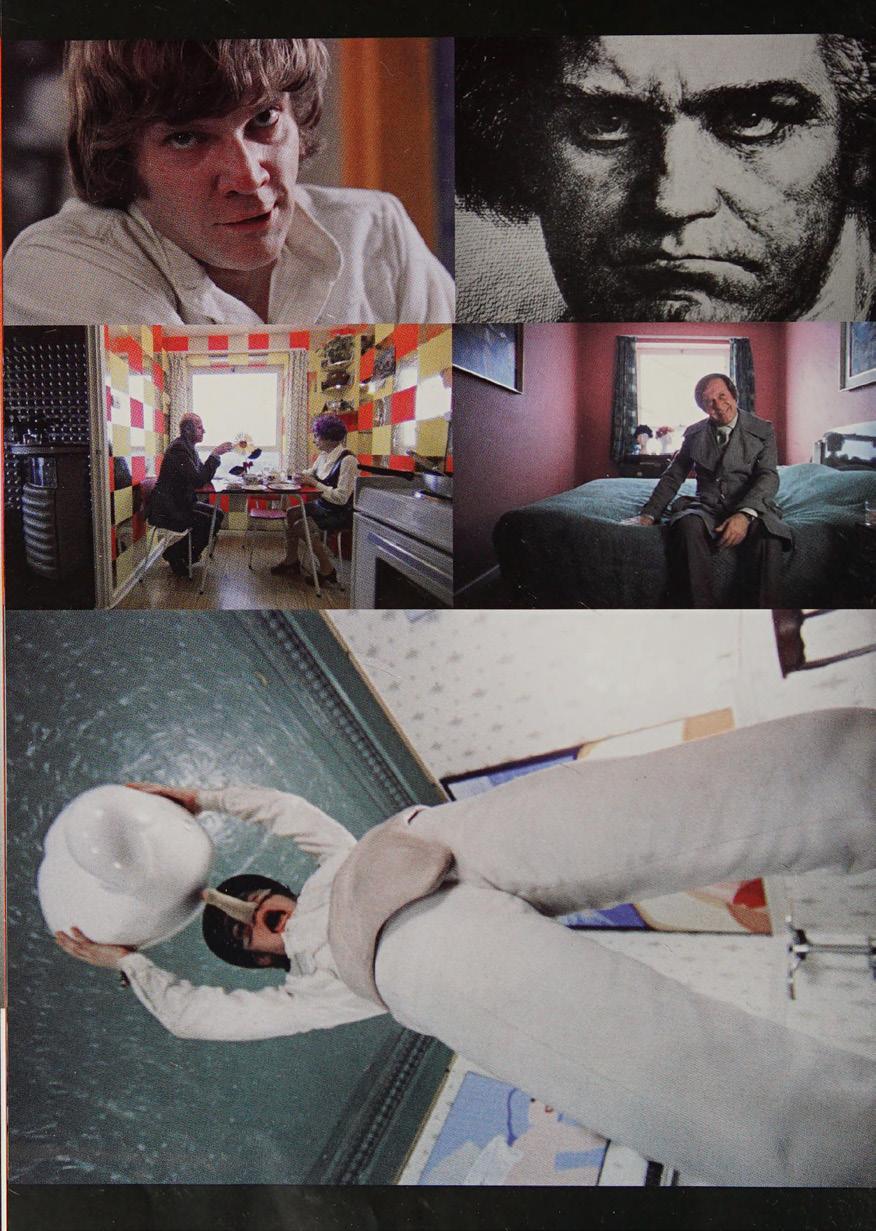

This fragility is present not only in public spaces but also in private designs. Alex's home, with its minimalistic geometry, appears orderly yet masks deeper violence and conflict. Kubrick’s visual conflict captures the hidden social crisis beneath modernism’s utopian vision, symbolizing the instability and repression lurking within these "pristine" structures. This fragility not only represents architectural vulnerability but also the inability of modernist spaces to cope with social complexities, transforming them into hotbeds for conflict and unease.

In Clockwork Orange, the film's cinematography vividly conveys the anxiety over defensible space. Crime is omnipresent, taking place in the various locations provided by the architecture, creating a sense of unease for the audience. It's not just the streets; even public areas lacking surveillance become lawless zones for these criminals.

The mural celebrating the working class, defaced by crude imagery, the damaged elevator doors, and the garbage-filled lobby all reveal the fragility and decay hidden beneath the seemingly orderly facade of modernist architecture. This vandalized lobby appears to have been abandoned by the residents, turning into a hunting ground for these delinquents. Once again, it illustrates the drawbacks of modernist architecture, which undermines territorial instincts and contributes to the deterioration of the urban environment.

Kubrick emphasizes the fragility of space to highlight the dystopian theme in Clockwork Orange and to critique modernist architecture and its social impact. Modernism, like the writer’s home in the film, may appear solid on the surface, but in reality, it is fragile and vulnerable.

In one of the scenes, a beam of light streaming through a modernist glass window is surrounded by dark branches, creating an immediate sense of vulnerability. This composition suggests the helplessness of the architecture and the looming threat of violence.

In the writer's home, there is a piece of furniture symbolizing fragility—a classic example of pop modernist design—resembling a fragile egg. The glamorous clothing of the writer's wife is on the verge of being torn off. The mirrors lining the walls reflect the sophistication of this capitalist household, yet they are about to be shattered.

What initially appears as an idyllic dollhouse becomes chaotic and ravaged once Alex and his gang invade. It seems as though the space offers no defense; every inch is fragile. This also hints at how, in the obsessive design world of the 1970s, such fragility could attract violence.

By contrasting the apparent solidity of architecture with the underlying fragility of space, Kubrick reveals the delicate nature of social order and the vulnerability of individuals within such settings. This fragility symbolizes the powerlessness of people in a totalitarian society and highlights the flaws of modernist design, particularly its inability to safeguard human freedom and dignity. This technique amplifies the tension and unease throughout the film.

In the film, the shapes of Alex's furniture are mostly simple lines and geometric forms, with a warm color palette and rich, vibrant hues. Symmetrical composition is used to depict both his daily life and inner world. The furniture and decorations in his home are arranged symmetrically, enhancing the sense of order in the scenes. This helps the audience better understand Alex's dual life: at home, he appears as a calm teenager, while outside, he is a violent criminal.

This stark contrast seems to metaphorically suggest that within the idealized utopian vision of modernism, there lies a latent social crisis. Beneath the glamorous exterior, there exists a violent criminal like Alex, threatening to disrupt the fragile balance of the social environment.

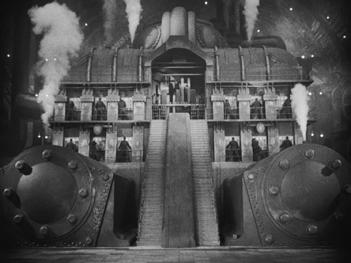

In many films, modernist architecture is used as a symbol of authoritarianism, reflecting a cold and detached society through rigid, rational design. In A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick employs brutalist architecture to embody the authoritarian nature of modernism, showing how such structures suppress human complexity in favor of a rational order. Similarly, J.G. Ballard's HighRise transforms a modernist high-rise into a micro-utopia that collapses into dystopia under the strain of class conflict and human complexity. These works reveal modernism’s limitations in addressing emotional and social complexities, as its controlled, rational structures amplify social tensions and reduce individual freedom, becoming metaphors for authoritarianism.

Authoritarianism is often seen as a flaw of modernism, with civic modernism serving as a clear example. Governments forcibly relocated the working class from their homes into buildings designed according to modernist principles, using purely rational straight lines devoid of complex ornamentation to dictate people's way of life.

Much like the prison in Clockwork Orange, these cold, rational lines and squares confined the prisoners, mirroring how modernist architecture restricts urban life. Modernism, through these buildings, proclaimed the idea that form follows function, subordinating architecture to ideology rather than human emotion.

Kubrick used Brutalist architecture to symbolize authoritarian modernism. The heavy concrete, with its rigid and purely rational lines, rejected the softness and complexity of organic life, forcing these criminals—symbols of human complexity—to submit to reason and order. This process seems to lament the way modernist urban development imposes a tyrannical, simplistic, and unemotional principle to solve all problems, ignoring the complexities of society and individuals.

At this point, Kubrick appears to stand in opposition to the modernist master Le Corbusier’s early 20th-century concept of the "machine for living." While modernist architects originally aimed to improve people's lives and social environments through design, Clockwork Orange uses its scenes to suggest that reality ultimately diverges from their ideals. 2.5

Similarly, in 1975, J.G. Ballard published the dystopian novel High-Rise, which presents a utopian high-rise building symbolizing modernist ideals. This building, containing residences, shops, and entertainment facilities, is envisioned as a self-sufficient micro-society. However, the social stratification and human weaknesses within the building lead to the collapse of its internal order. The core conflict arises from the division of power within the building, which triggers class struggles that spiral into a battle for resources and privileges.

The high-rise in the novel serves not only as a physical space but also as a metaphor for social structure and power dynamics. Architectural elements like elevators are used to symbolize social mobility and class rigidity. The novel explores the complex relationship between architecture and social order. While modernism emphasizes rationality and functionality, High-Rise reveals the fragility of these designs when confronted with the complexities of human nature and society. The chaos and violence within the building expose the irrational behaviors that emerge when humans are placed in extreme conditions.

Both High-Rise and Clockwork Orange use architectural and environmental design to explore issues of social control and order. In High-Rise, the design of the high-rise building was intended to achieve social rationality and order, but it ultimately leads to chaos and collapse. In A Clockwork Orange, the modernist urban environment and architecture reflect concerns about individual freedom and social control.

Figure :https://efsunland.com/2016/02/22/review-high-rise/

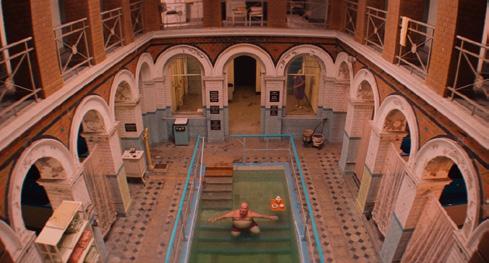

In the film High-Rise, adapted from the novel, the cinematography offers a more profound depiction of this conflict. The once pristine and glamorous interior of the building becomes increasingly dilapidated as the struggles intensify. The modernist ideals, symbolizing a utopian vision, gradually disintegrate under the weight of complex social structures and human nature. Beneath the seemingly indestructible exterior lies decay and ruin. Utopia represents an ideal, while dystopia reveals the harsh truths of the real world.

In Clockwork Orange, the Ludovico treatment, which forcibly eliminates Alex's violent tendencies through aversion therapy, symbolizes the control of individual freedom by authority. The extreme control exerted by the state over personal behavior parallels the impact of modernist architecture and urban planning on society—employing a near-utopian, authoritarian approach to forcibly correct societal issues. High-density tower blocks and functionally driven designs, devoid of human warmth, lead to the fragmentation of communities and a rise in crime rates. These buildings symbolize a social structure that suppresses and controls individual freedom, much like the Ludovico treatment, and are reminiscent of the dreamlike building in High-Rise. The ultimate collapse of Alex, alongside the descent into chaos by the residents in High-Rise, reflects the limitations of modernism in addressing the complexities of societal problems.

The modernist vision for architecture once represented progress, rationality, and societal harmony. Yet, through time, its structural rigidity and imposition of order revealed a profound gap between idealized spaces and the complex realities of human behavior.

As analyzed in films like A Clockwork Orange and High-Rise, modernist architecture’s ambition often clashed with individual freedom, becoming a metaphor for authoritarianism and isolation. These works underscore how the uniformity and control inherent in modernist spaces frequently alienate the very communities they intended to unite, reflecting the limitations and paradoxes of modernism in urban planning.

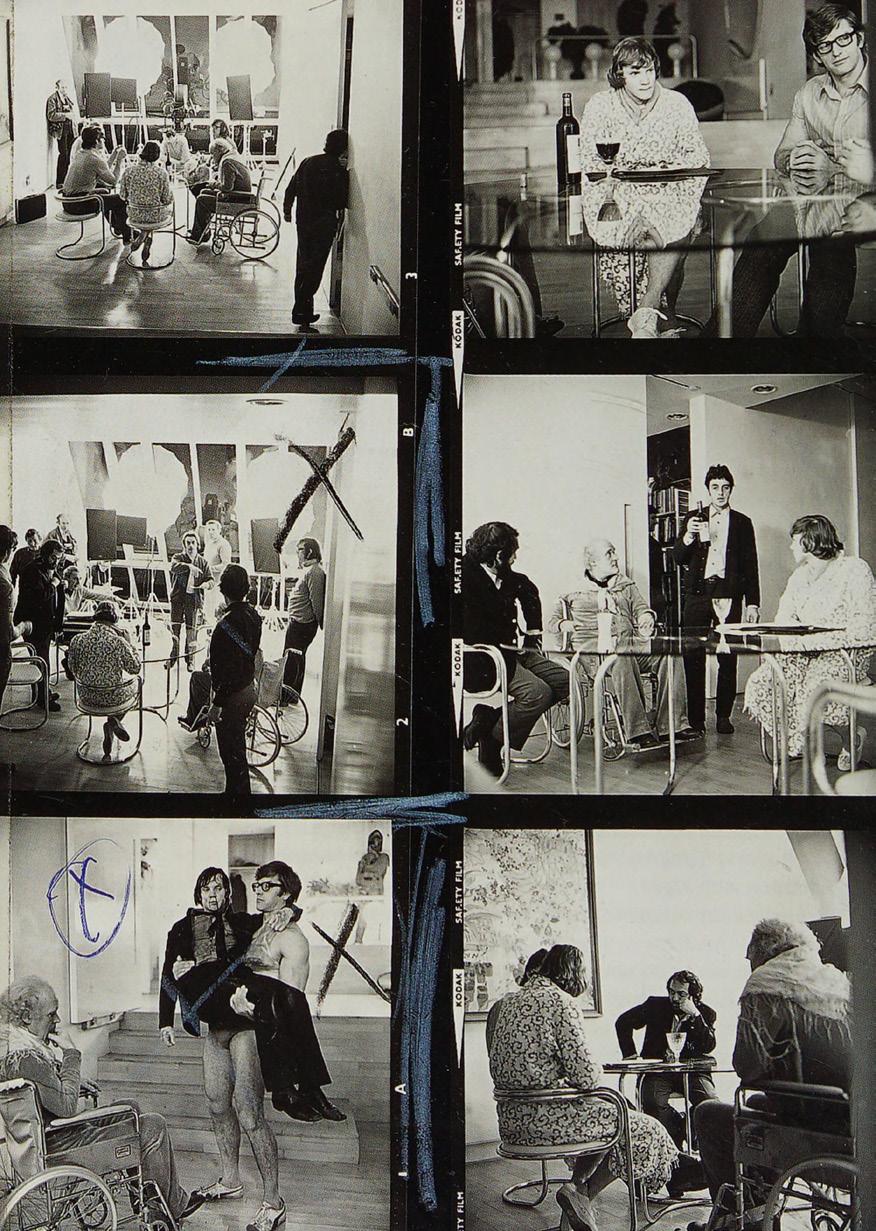

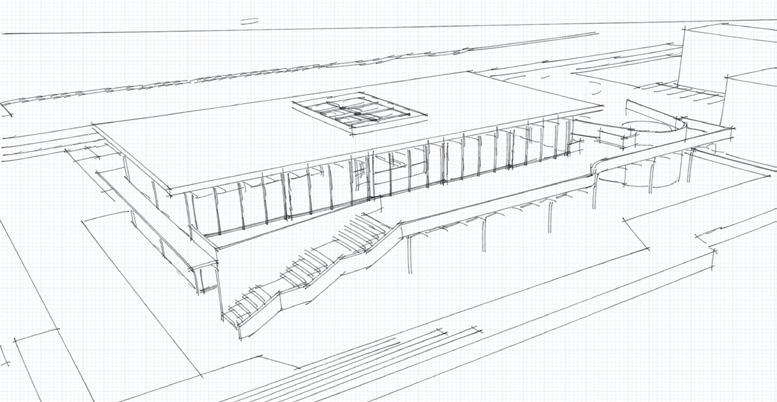

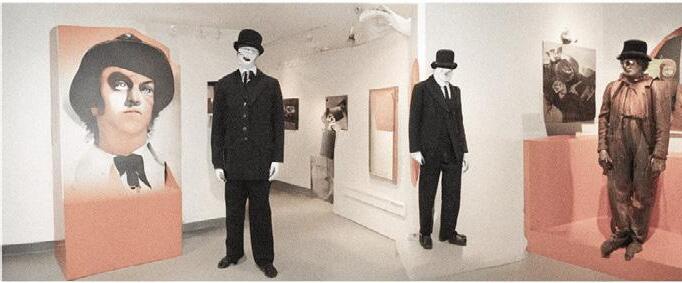

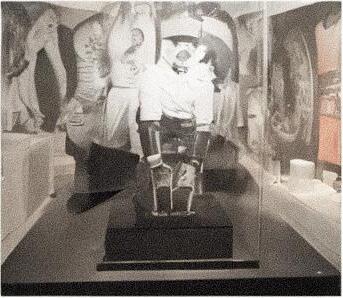

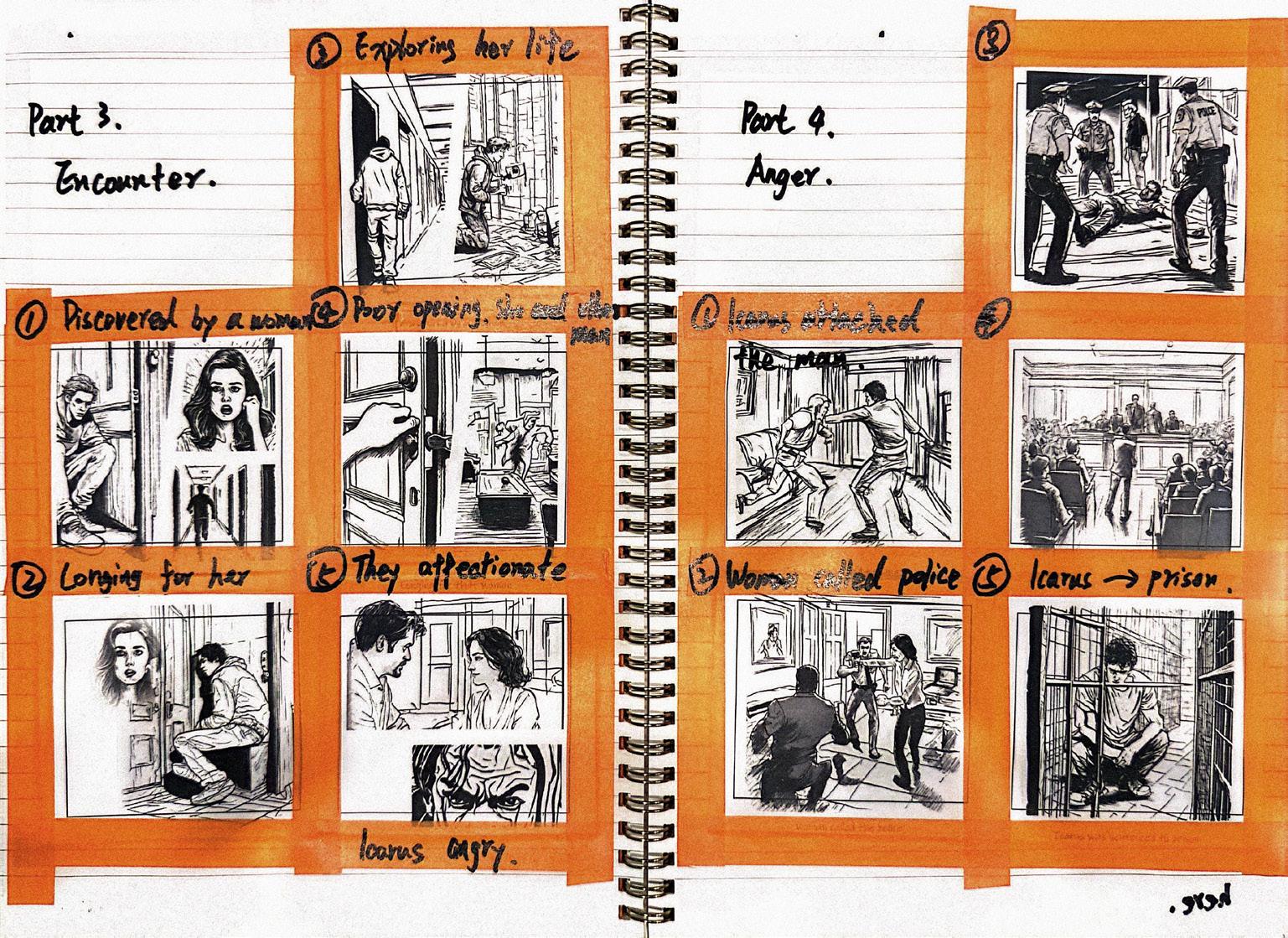

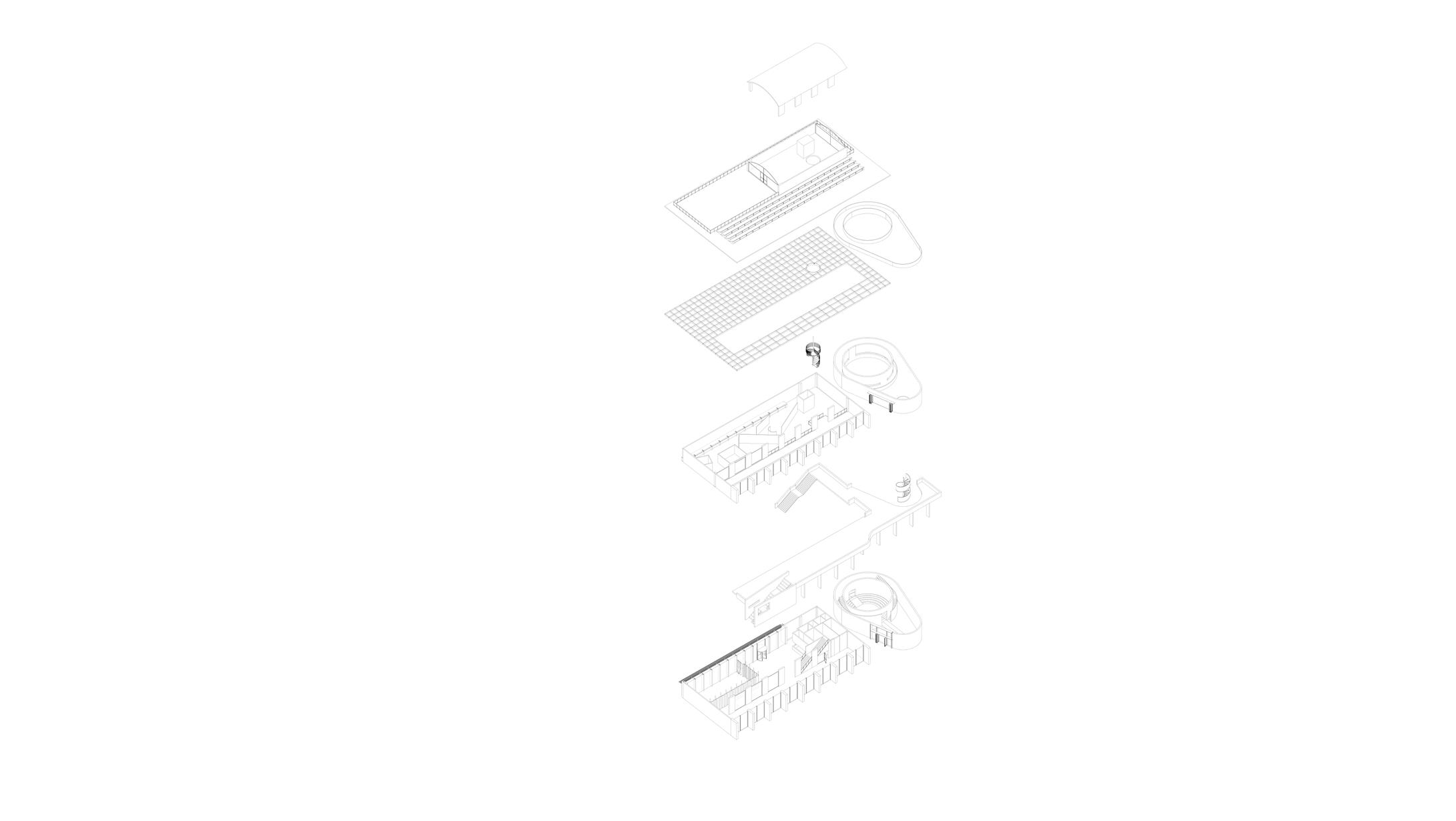

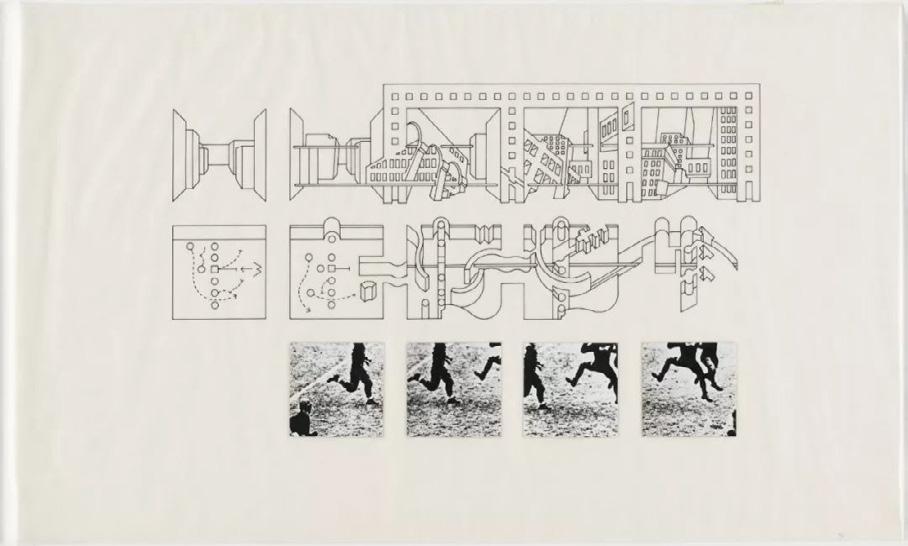

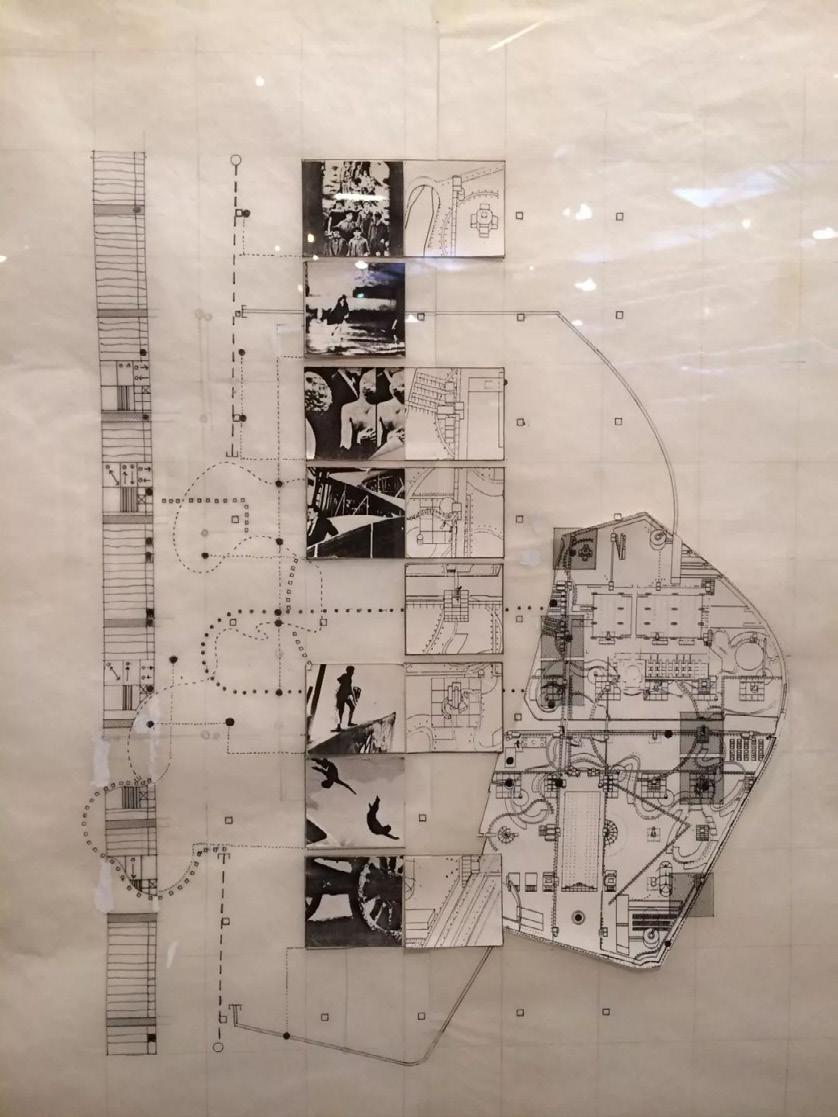

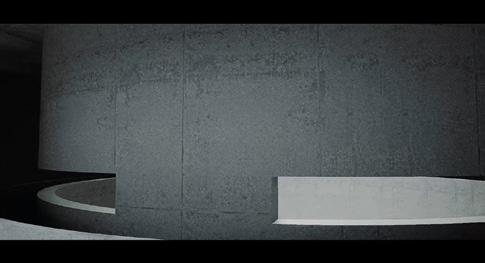

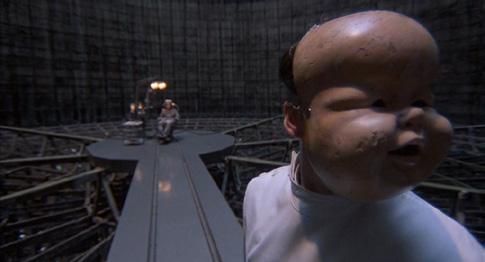

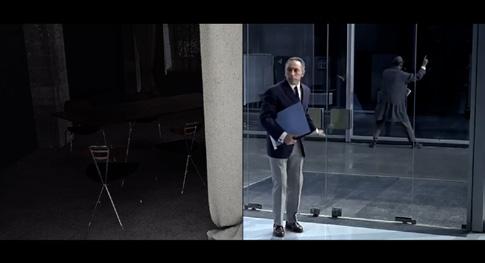

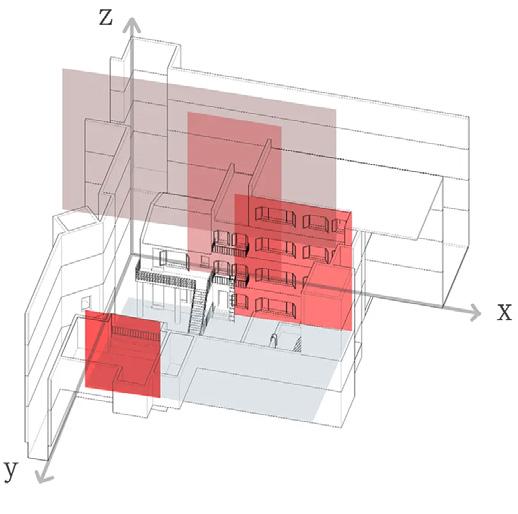

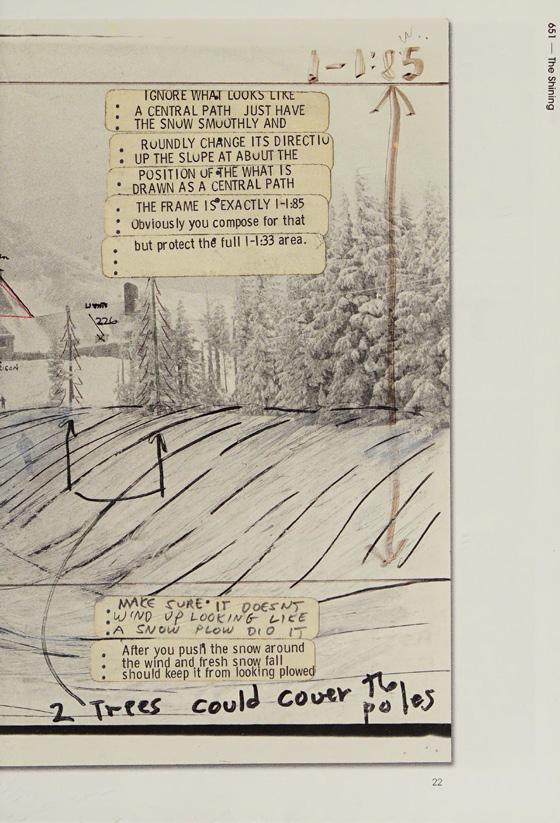

This chapter focuses on the evolution of the project’s design, from concept to final presentation. Initially inspired by Kubrick's A Clockwork Orange, the design mirrors the film's visual language to follow protagonist Icarus's journey, symbolizing modernist architecture’s trajectory from idealized rise to decline and potential redemption. Icarus’s story reflects themes of social control and isolation within urban space, while also exploring personal rebirth. As the design matured, it diverged from Kubrick’s style to develop an independent narrative. The story follows Icarus as a museum cleaner, giving architectural space dynamic, narrative quality. The film collage technique juxtaposes scenes from other works, exposing modernist architecture’s contradictions—its external solidity versus internal fragility. This approach illustrates the project’s interpretation of architecture as a "total work of art," using cinematic language to reframe and deepen understanding of architectural space.

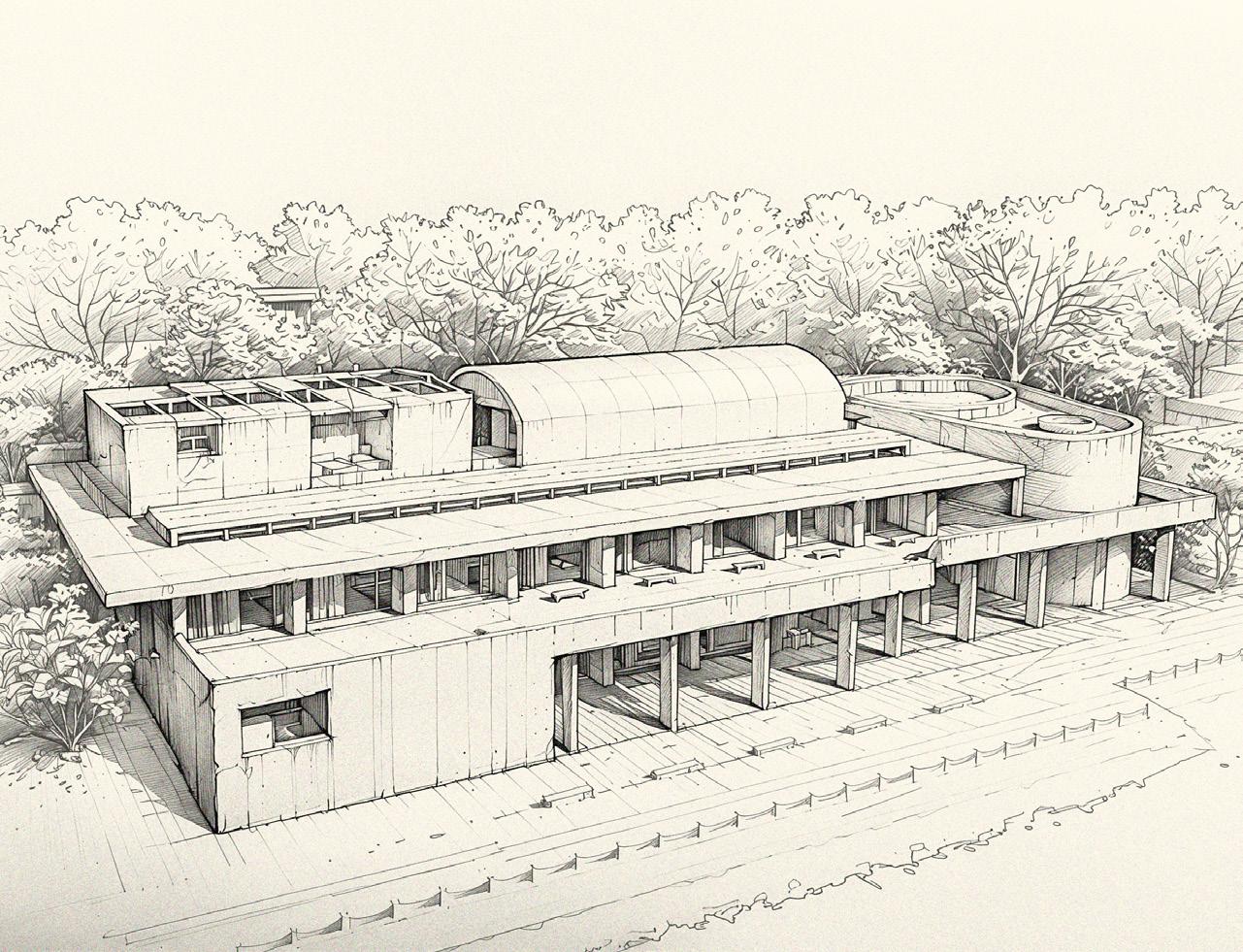

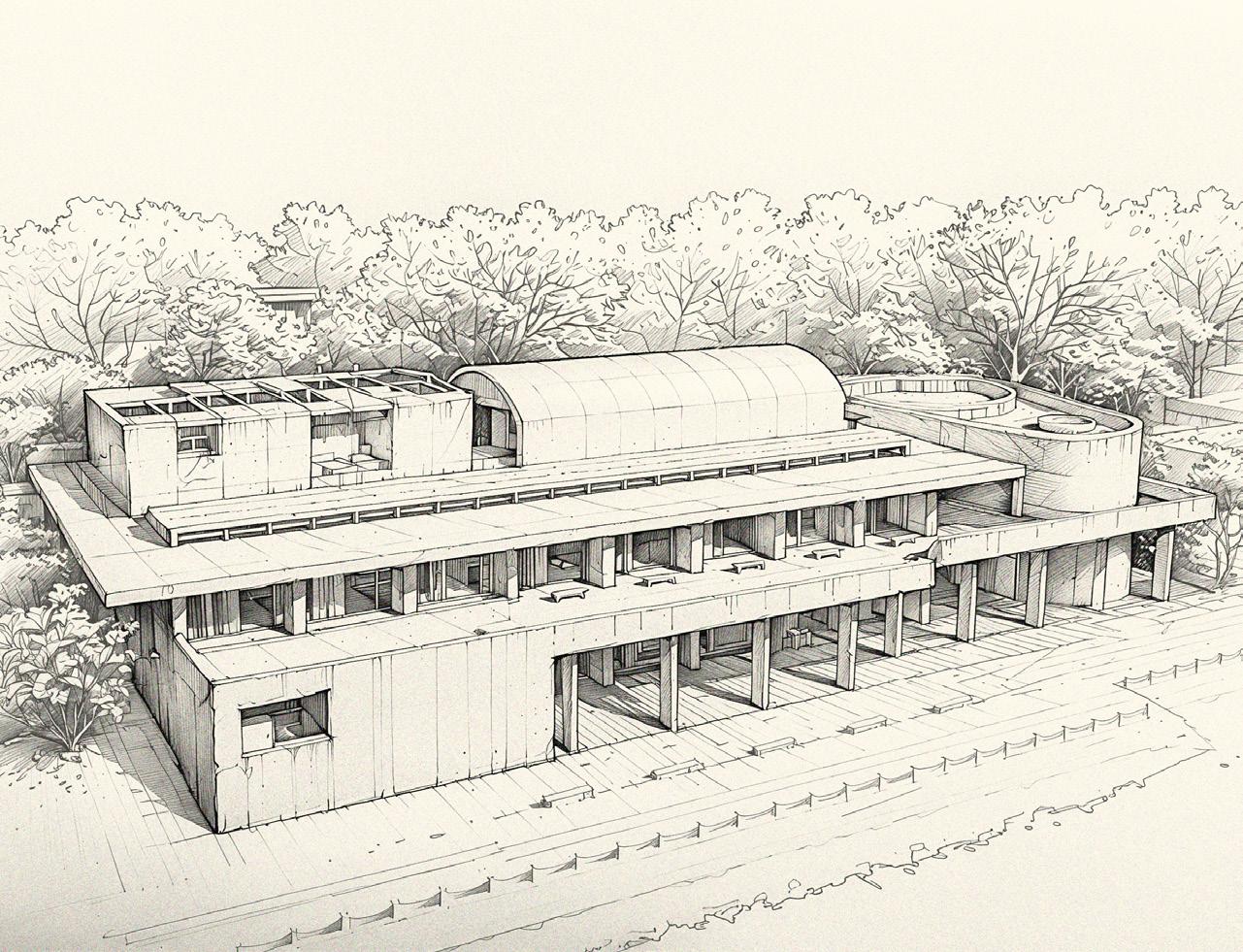

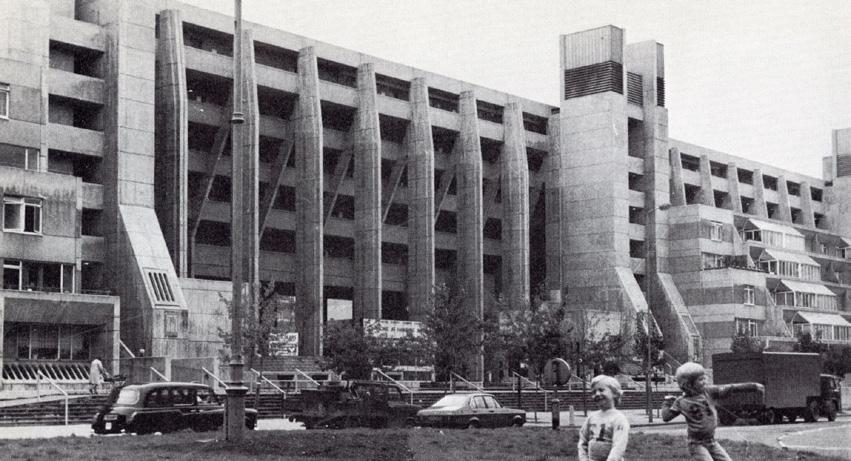

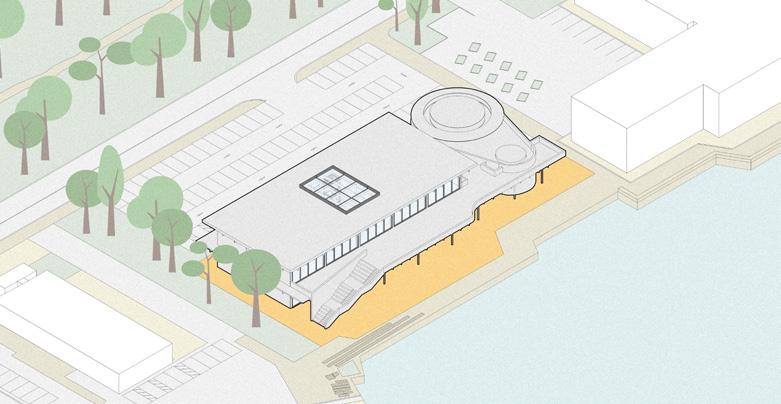

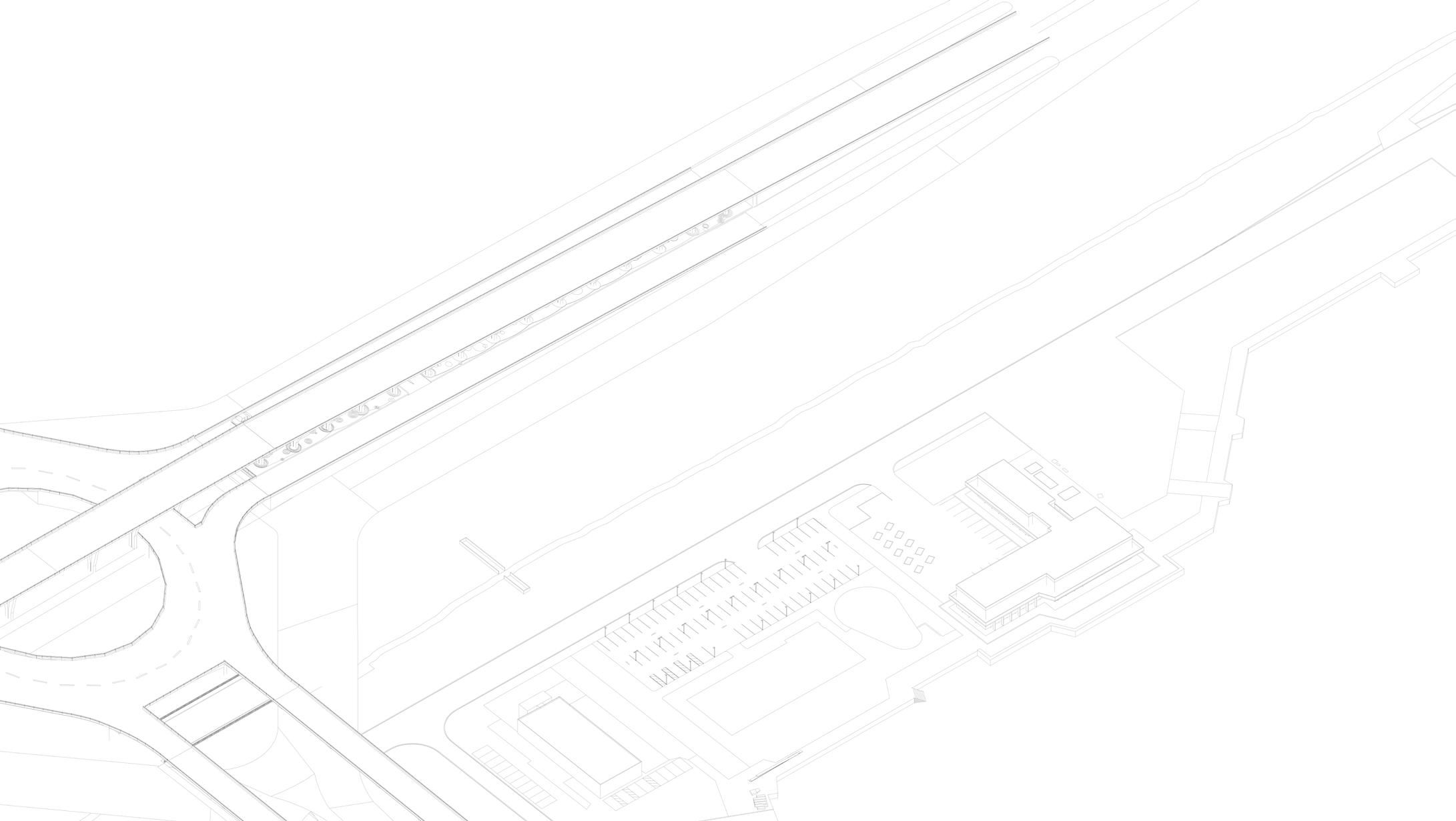

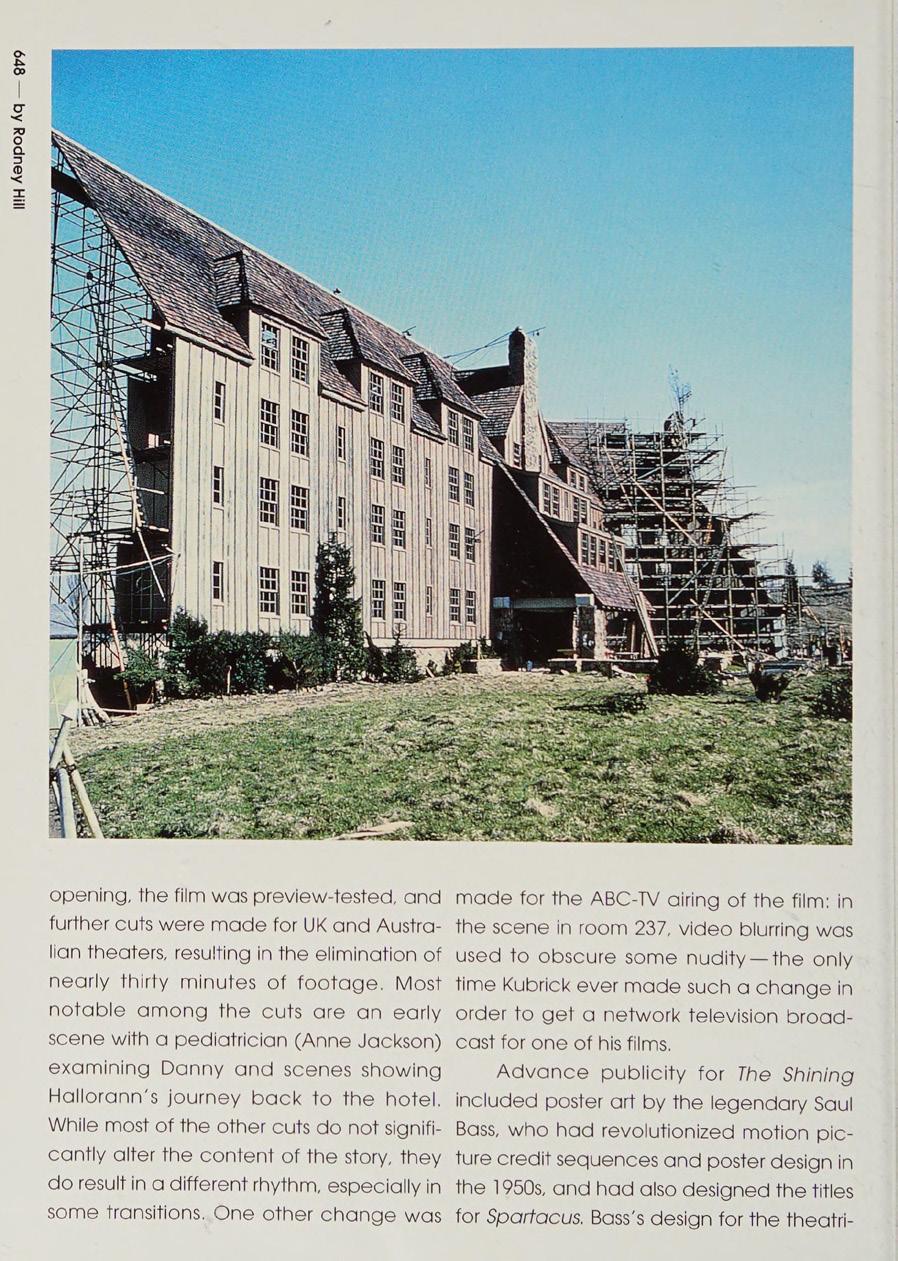

In the conceptual phase, this project critically explores modernism's decline through the lens of Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange, especially its impact on urban planning. Set in 1970s London—a period and place marked by the collision of modernist ideals with social upheaval—the museum is conceived as a virtual space that reflects modernism’s architectural crisis.

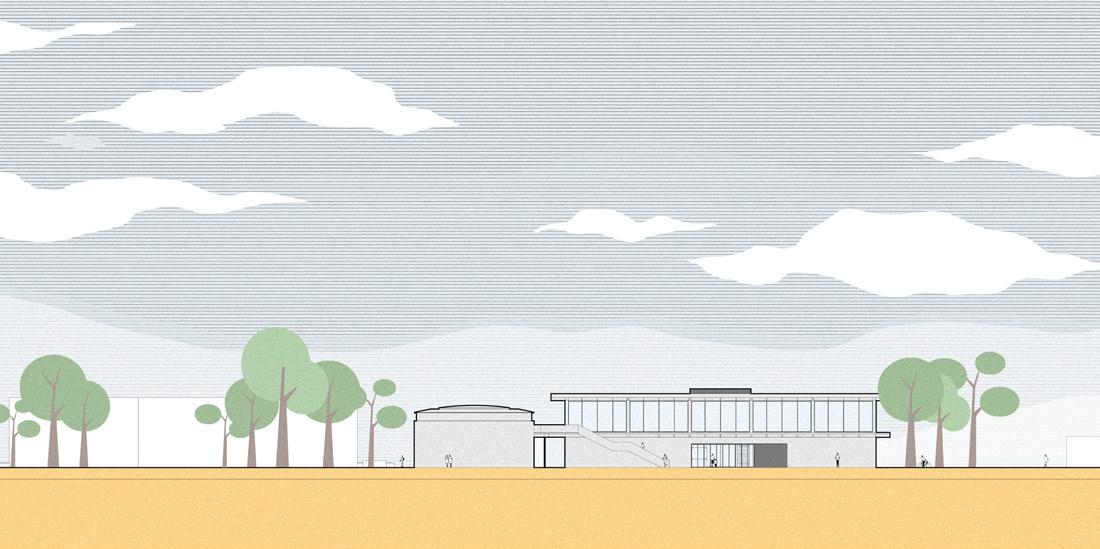

The museum design draws on modernist features, with concrete materials, stark structural lines, and strip windows, symbolizing control and oppression. This evokes the authoritarian themes in Kubrick’s work, casting the museum in a brutalist, dystopian atmosphere. The museum program includes an archive of Kubrick's work, exhibition halls juxtaposing modernist ideals with the dystopian reality depicted in A Clockwork Orange, and a research center. These elements aim to foster an immersive narrative experience where visitors witness the fragile social consequences of modernist visions, provoking reflection on its limitations and relevance to today’s urban challenges.

Initially, I debated whether to apply modernist aesthetics to a project critical of that style. However, given the project’s context, these elements—concrete, bold structures, and stark materials—effectively capture the modernist architectural control, aligning with the oppressive atmosphere found in Kubrick’s narrative. As the design progresses, I intend to refine this ambiance, balancing raw concrete against the softer landscape to enhance a critical, immersive experience. Through this setting, visitors traverse the thematic halls, confronting the societal outcomes of these architectural ideologies.

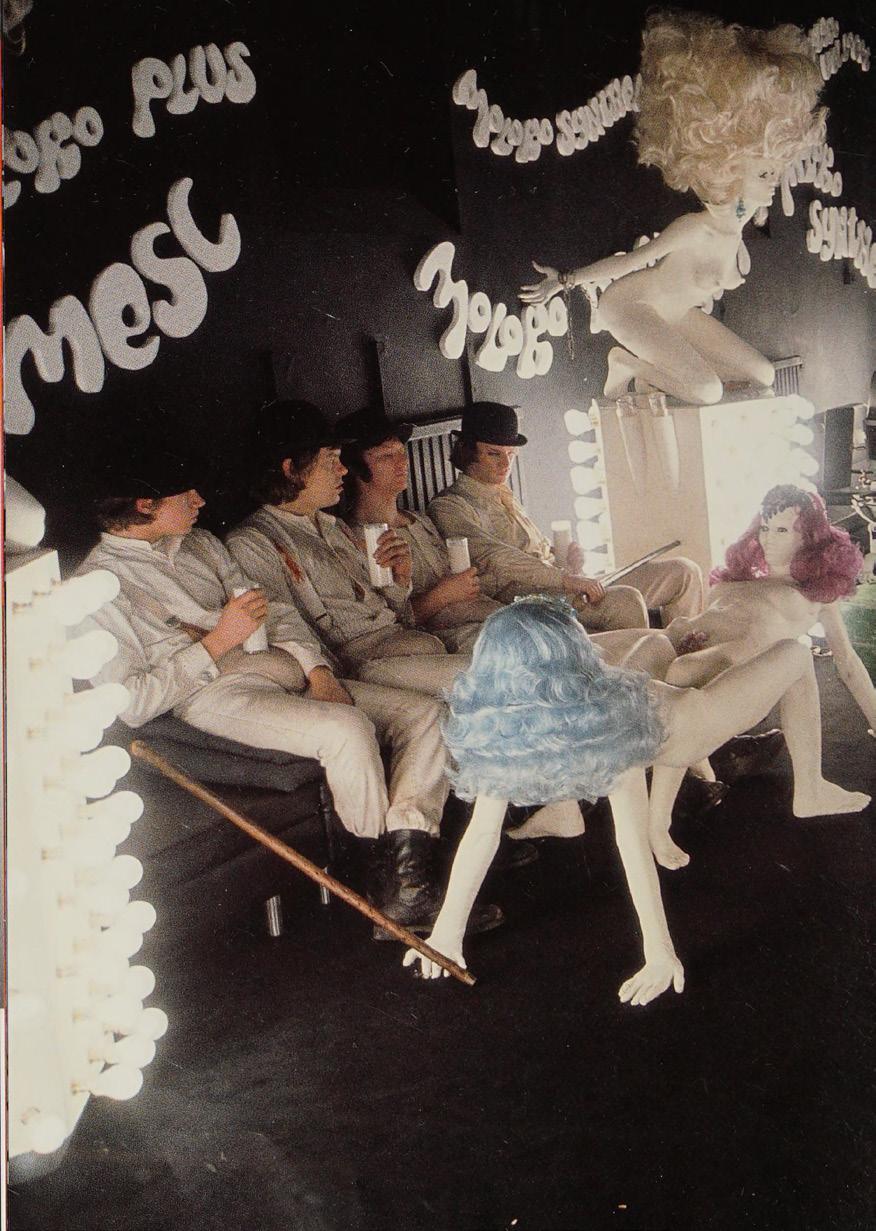

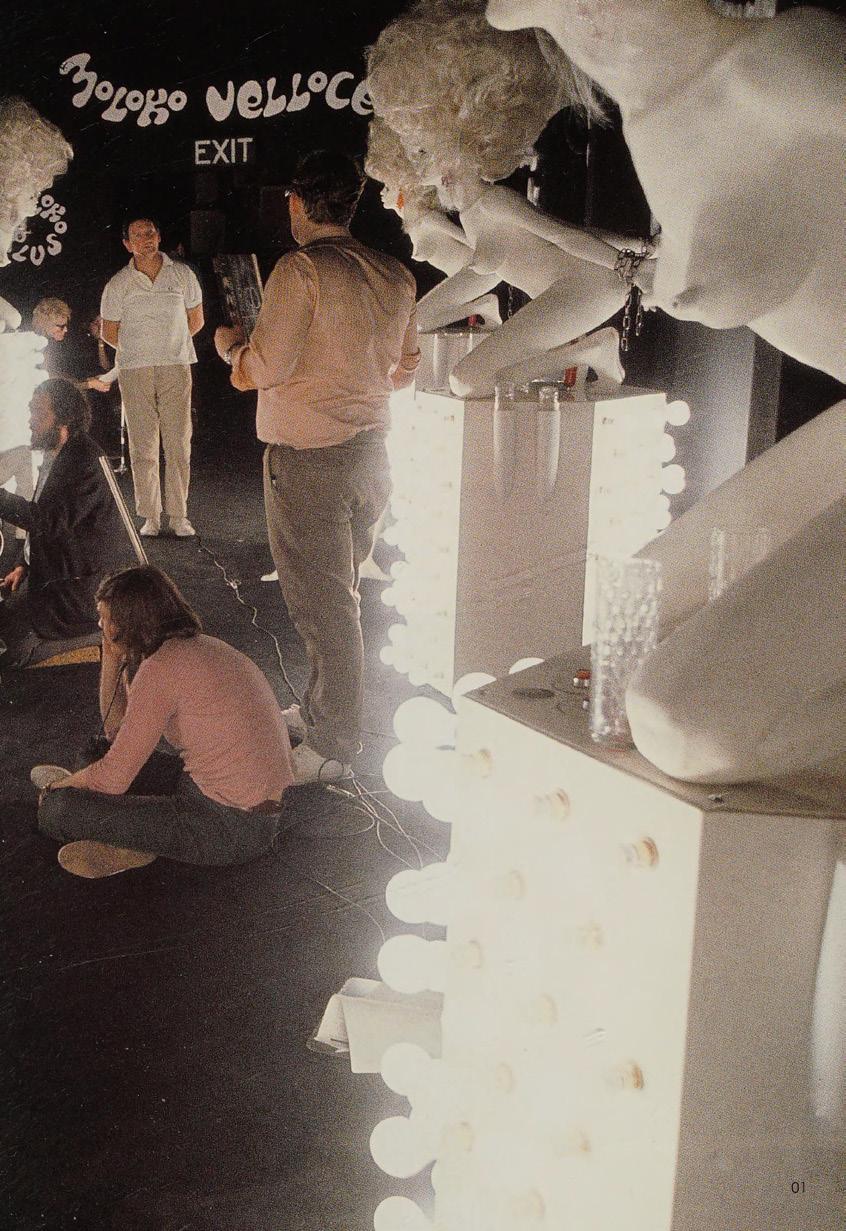

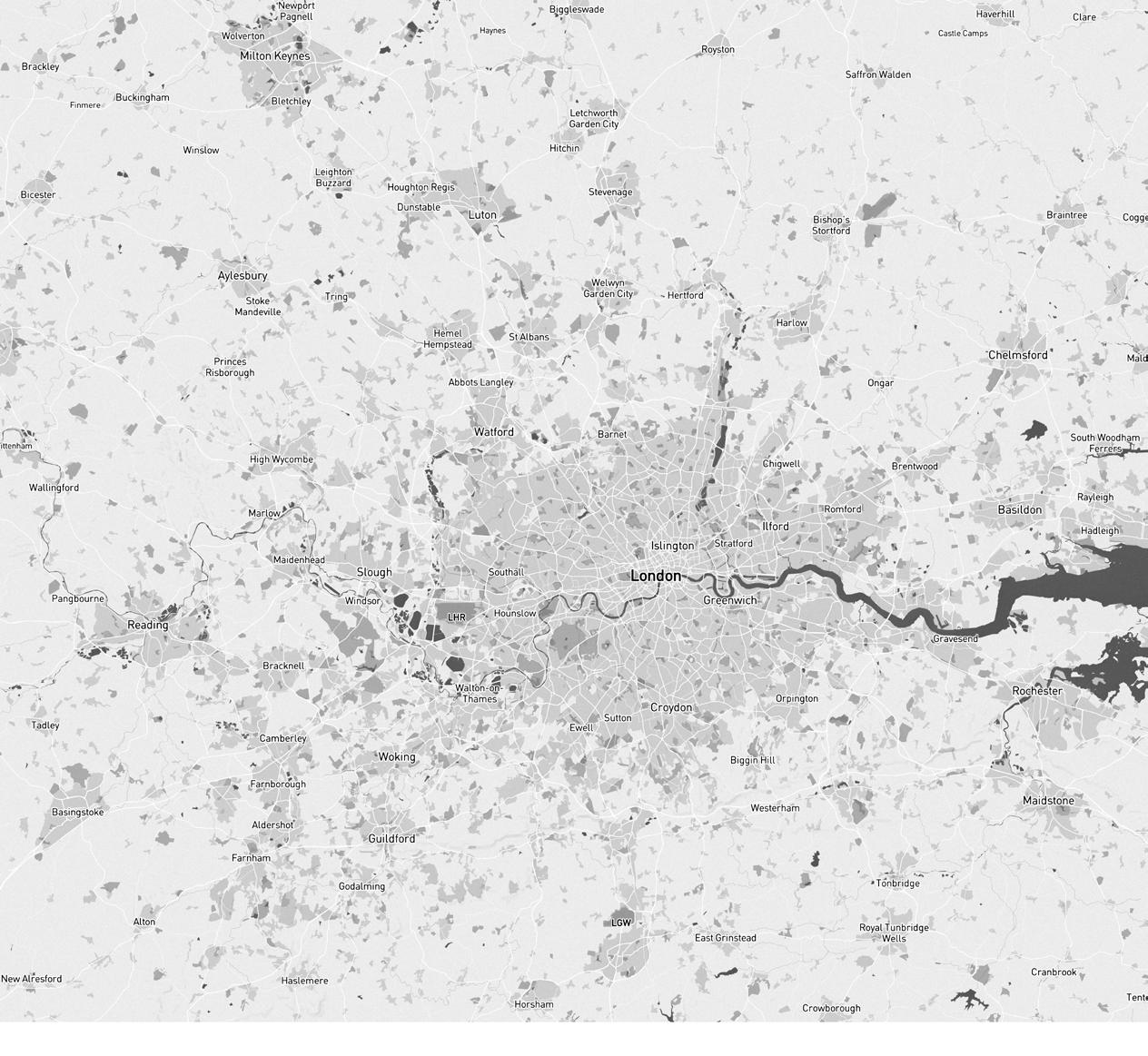

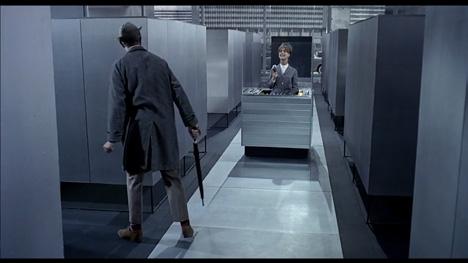

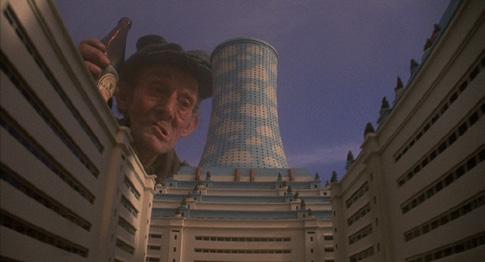

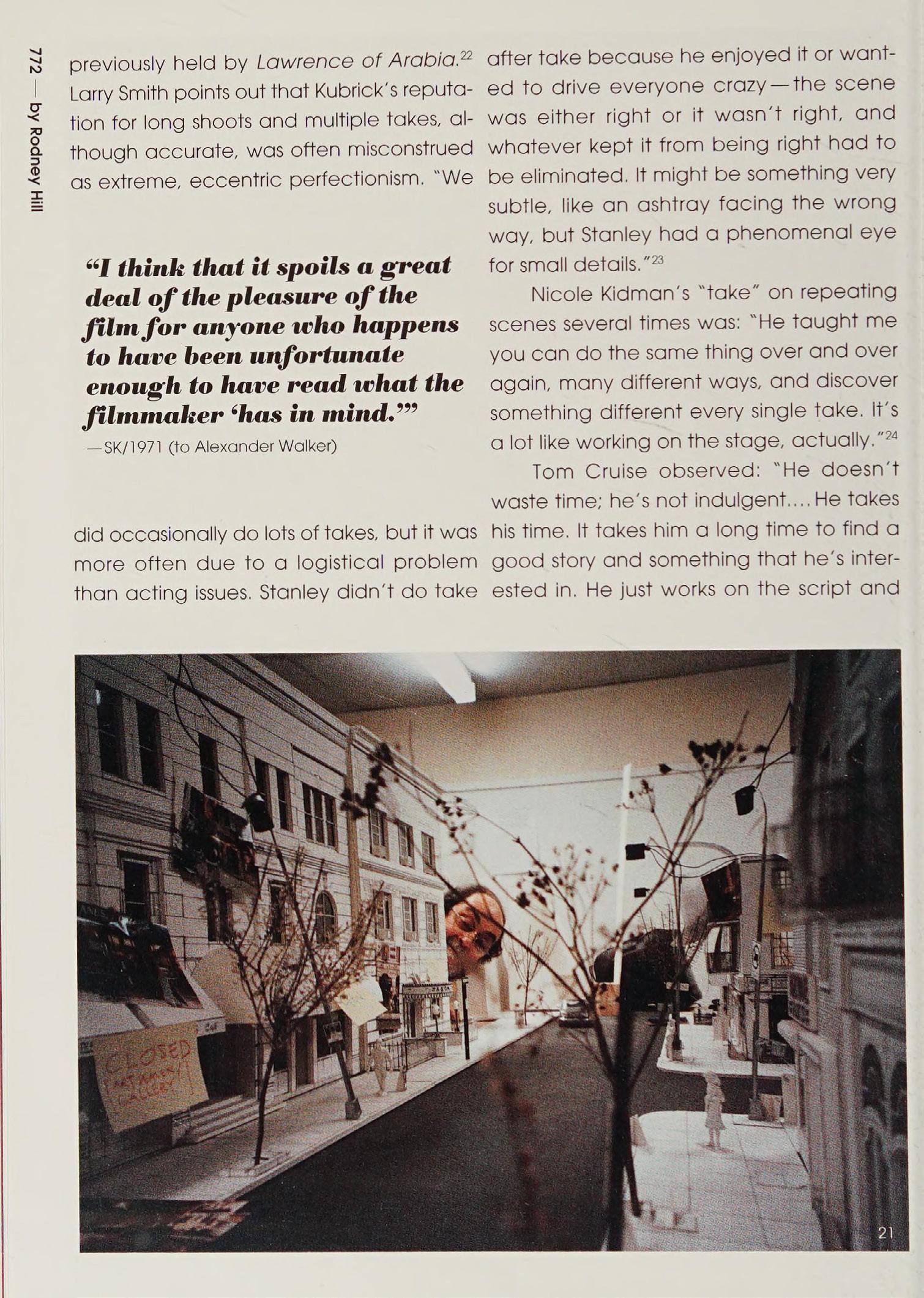

The story of A Clockwork Orange is roughly set in northern England, but the film was almost entirely shot in and around London and the surrounding counties of southeastern England. Stanley Kubrick, known for his aversion to travel, chose filming locations based on architectural guides.

Stanley Kubrick selected futuristic real-world locations for A Clockwork Orange, such as London's Thamesmead Estate, characterized by its Brutalist modernist architecture. These structures symbolized social control and oppression, perfectly aligning with the film's dystopian themes. By using these stark concrete buildings and lifeless urban spaces, Kubrick critiqued the failures of modernist architecture, revealing its suppression of individual freedom and the fragility of social order. These locations intensified the film’s exploration of the tense relationship between modernist architecture and society.

As the primary filming location for A Clockwork Orange, London is filled with traces of modernist architecture. These structures not only showcase the architectural style of the mid-20th century but also reflect the tension between the utopian vision of urban planning and the reality of the time. London’s modernist remnants provide the project with a historically rich, tangible backdrop, perfectly suited for exploring the decline of modernism and its social impact. By incorporating the city’s real architectural heritage, the project conveys the limitations of modernist architecture in dealing with social complexity more deeply, offering visitors an immersive experience of historical and architectural critique.

Weekday

This diagram illustrates the functions and visitor flow throughout the site. Different shapes represent various activities that may occur in the space. The size of the shapes at different times reflects the fluctuations in visitor traffic.

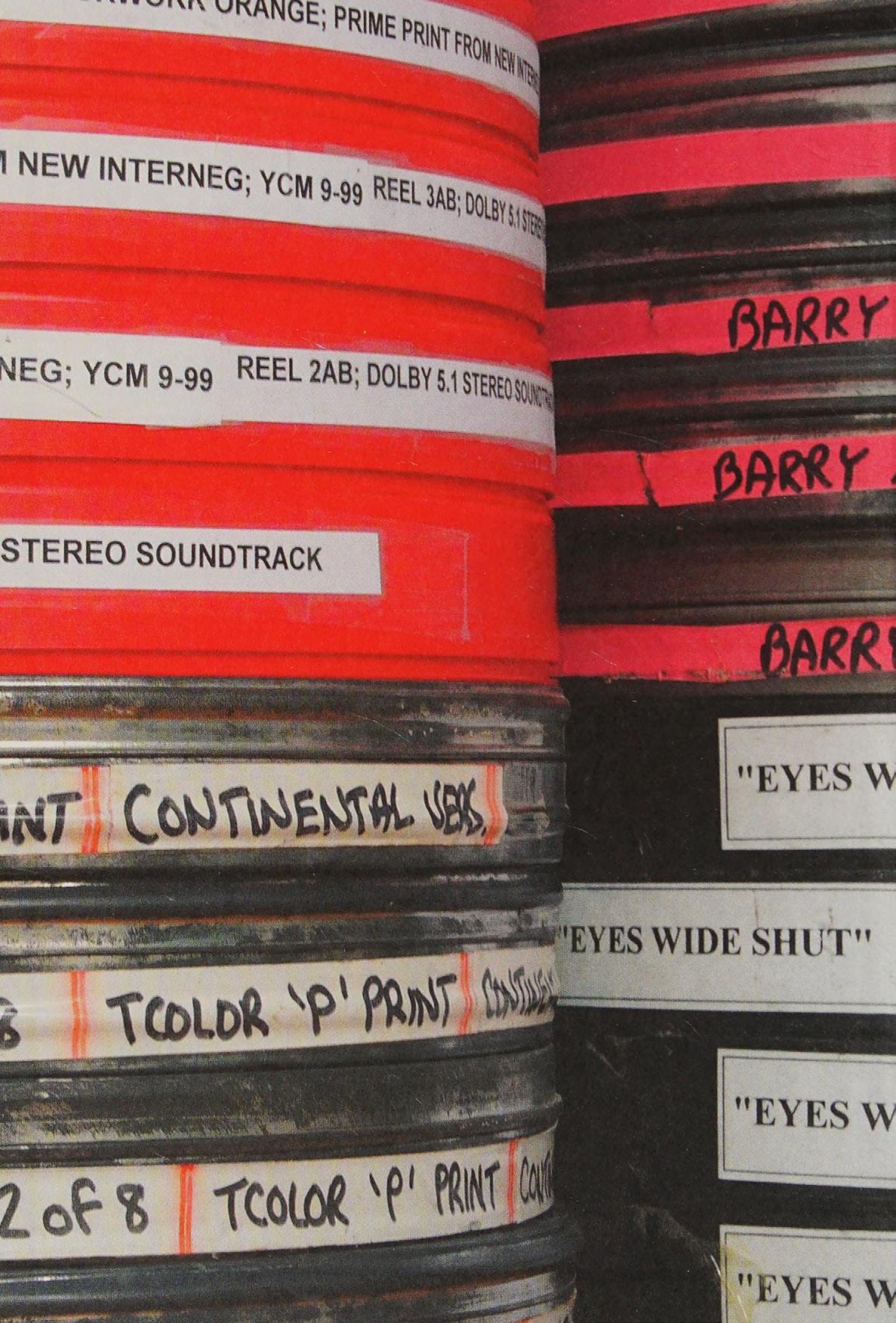

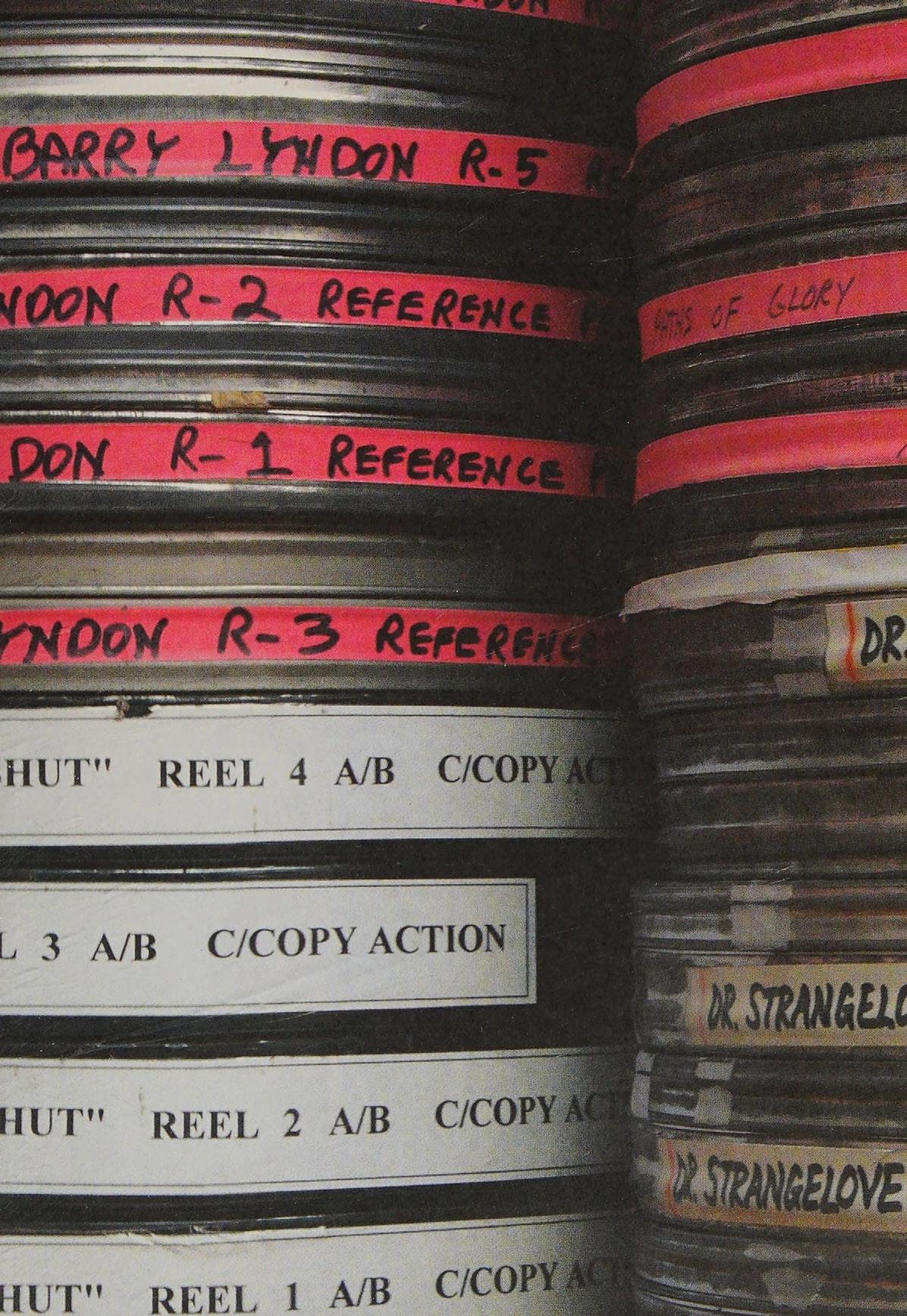

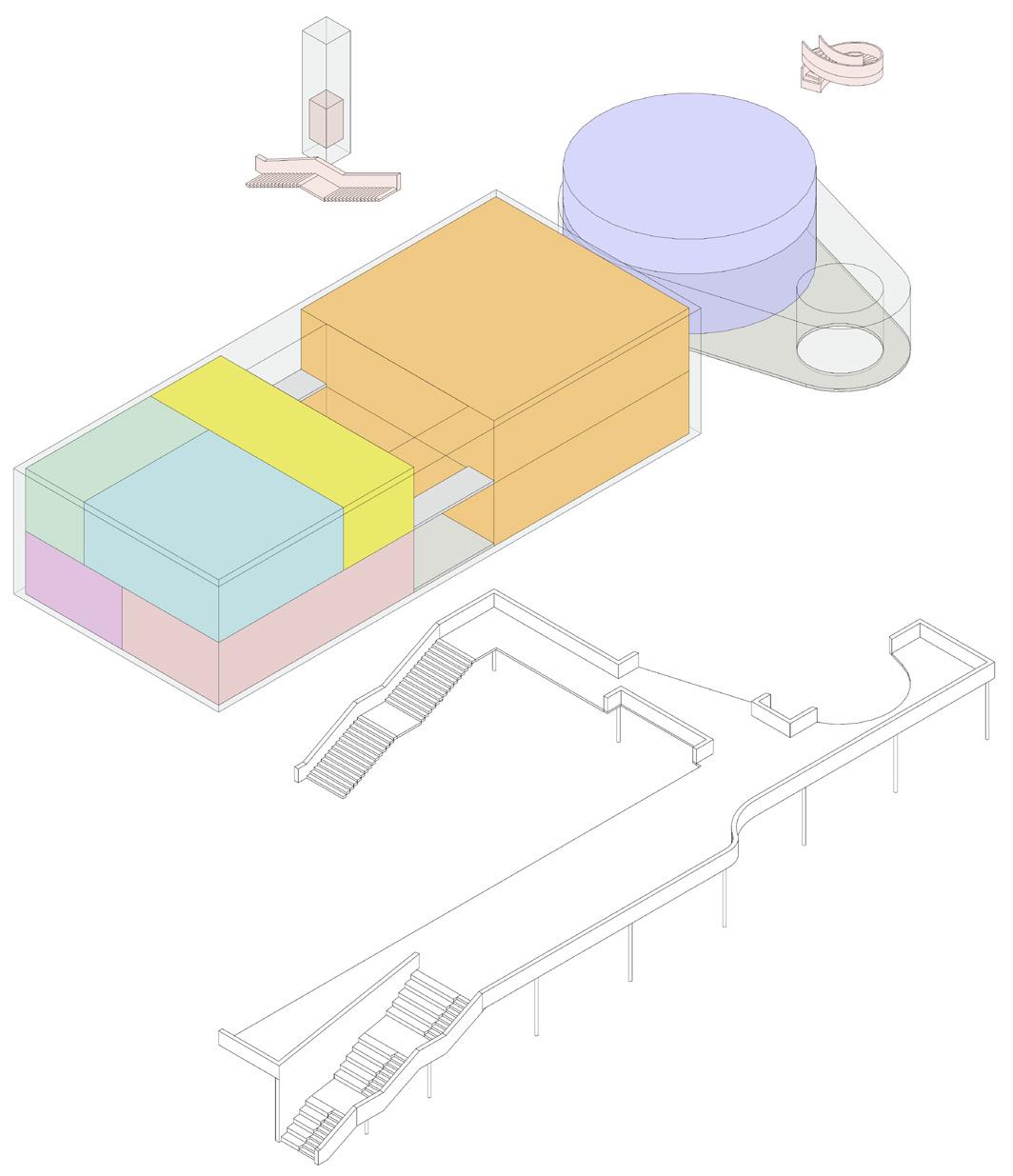

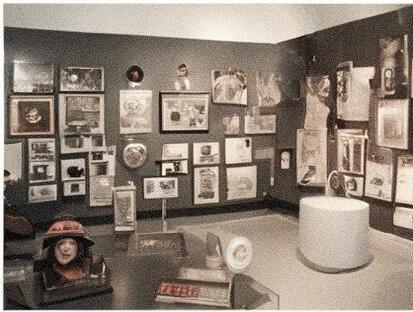

The project includes a Kubrick archive, a multi-functional temporary exhibition hall, a gallery on A Clockwork Orange and modernist architecture, a cinema screening room, and a research center. Exhibits juxtapose modernist utopian ideals with the dystopian reality portrayed in A Clockwork Orange, highlighting modernism’s evolution. Visitors navigate thematic halls that showcase the societal impacts of these architectural visions, like community fragmentation and individual repression, allowing them to reflect on modernism’s limitations and its relationship to urban challenges in a multi-dimensional, narrative-driven experience.

In this design exploration phase, the project centers on the concept of "Total Art," shaping the character of Icarus to reflect the rise and fall of modernist architecture, the symbolism of labor, and a journey of self-redemption. The museum, as a fictional structure in the film, reveals that modernist architecture represents more than form—it encapsulates complex ideals, loss, and rebirth. Icarus’s trajectory mirrors the development of modernism: his imprisonment during its crisis symbolizes the collapse of projects like Pruitt-Igoe, while his release aligns with modernism's resurgence led by architects such as Lacaton & Vassal.

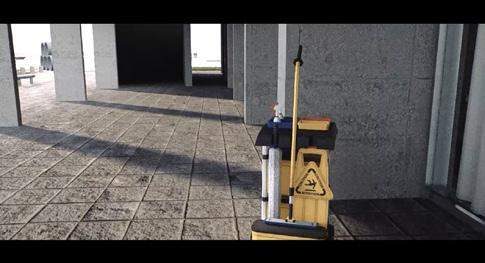

To amplify this narrative, the design adopts Icarus's perspective to render the architectural space, displaying traces of his labor—cleaning tools, handling equipment, and daily scenes in rest areas. This method deepens viewers' understanding of modernism’s dual role, not merely as a functional container but as a vessel for emotion and ideology. It highlights the limitations and renewal potential within modernist architecture, revealing a profound connection between "Total Art" and architectural design's multidimensional expression and artistry.

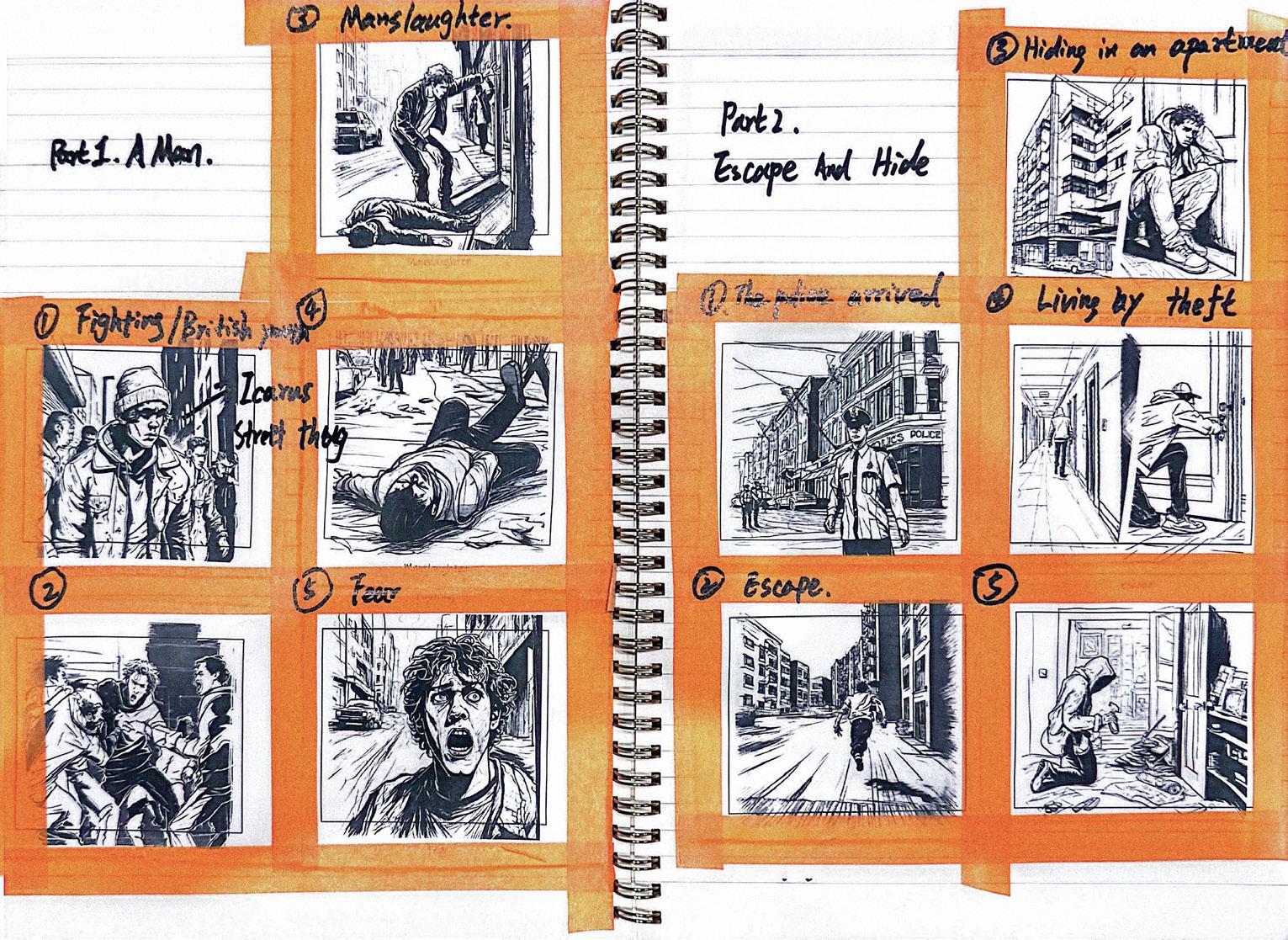

The protagonist's name is Icarus (derived from the Greek myth of Icarus. This name symbolizes the pursuit of freedom and dreams, while also representing the warning against overconfidence and power. Icarus flew too close to the sun, causing his wings to melt, which alludes to the loss and failure of modernist architecture’s utopian pursuits). Icarus is a 20-year-old living in 1970s London, a street thug (similar to Alex from Clockwork Orange). During a street fight, he accidentally kills his victim and, in a panic, flees into an apartment building to hide (this is the location of the project site).

This building resembles Le Corbusier's Unité d'Habitation, containing shops, dining venues, gyms, and gathering spaces (symbolizing the utopian fantasies of modernism). Due to the large number of residents in the building, no one notices this outsider (symbolizing how modernism increases the distance between people, with high-rise buildings weakening the territorial instincts inherent in humans). Icarus hides in an abandoned storage room within the building (since the building is so vast, some spaces have become idle). His experience as a street thug allows him to easily break into others' apartments to steal food, toiletries, and even take a hot bath, carefully tidying up afterward to avoid being discovered.

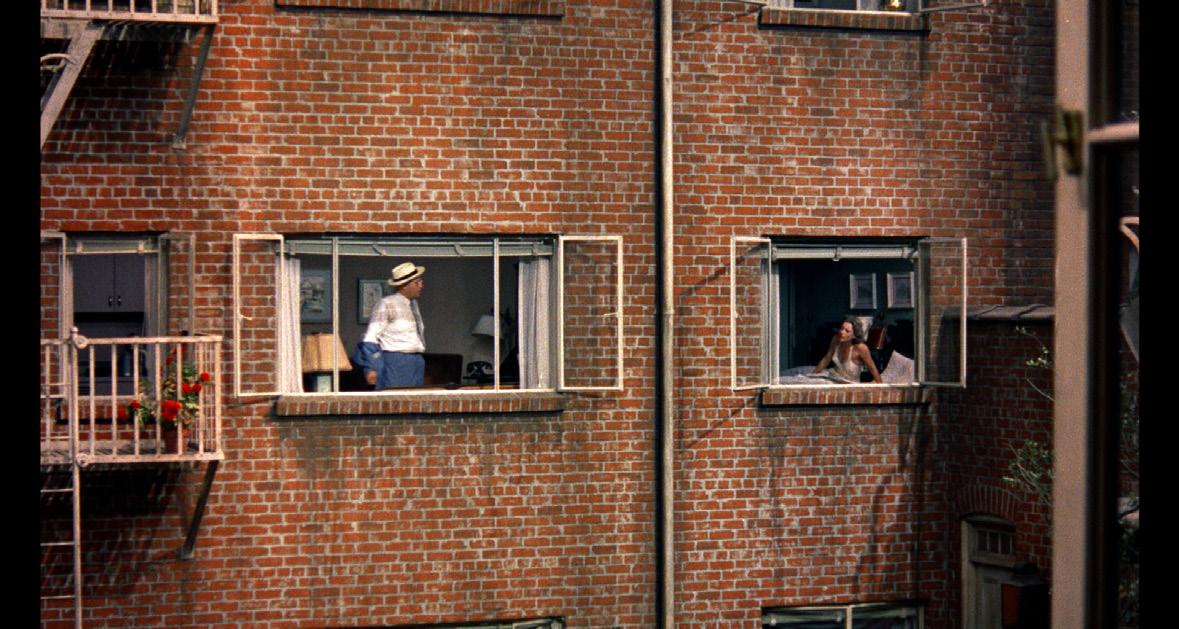

During one break-in, he is discovered by a beautiful woman named Marina who lives next door. She is a mature woman who, not wanting to get involved, doesn’t call the police but instead hurriedly returns to her own home. However, this encounter sparks an obsession in Icarus. Marina's image lingers in his mind (symbolizing the beginning of a longing for the beauty of modernism). He begins secretly watching her from the hallway, sneaking into her apartment when she is away to explore her life. To satisfy his sexual fantasies, he even steals some lingerie from her clothesline. On one such occasion, Icarus sneaks into Marina's home again. Lying on her bed, he fantasizes about living with her in this apartment. He becomes so engrossed in his fantasy that he falls asleep (hinting at the pursuit of utopian ideals at all costs).

Suddenly, the sound of the door opening shatters his dream. Panicking, he hides under the bed. Through the gap under the bed, Icarus sees Marina’s high heels and a man’s polished leather shoes. The two passionately fall onto the bed and begin kissing, the bed frame shaking with their movements. The constant tremors hit Icarus’s back, and as he transitions from initial fear and heartbreak to growing anger, he eventually erupts, crawling out from under the bed and attacking the man. However, due to being malnourished, Icarus is too weak to be a match for the man and is beaten and subdued (modernism’s fragility when faced with the complexities of society, slowly being crushed by reality).

In the end, Marina and the man decide to call the police, and Icarus, pinned to the floor, gazes tearfully at Marina. She, who existed in his fantasies yet was also a real person, is forever out of reach (symbolizing the collapse of modernist utopian dreams, which, like Marina, are real but ultimately fragile and unrealistic).

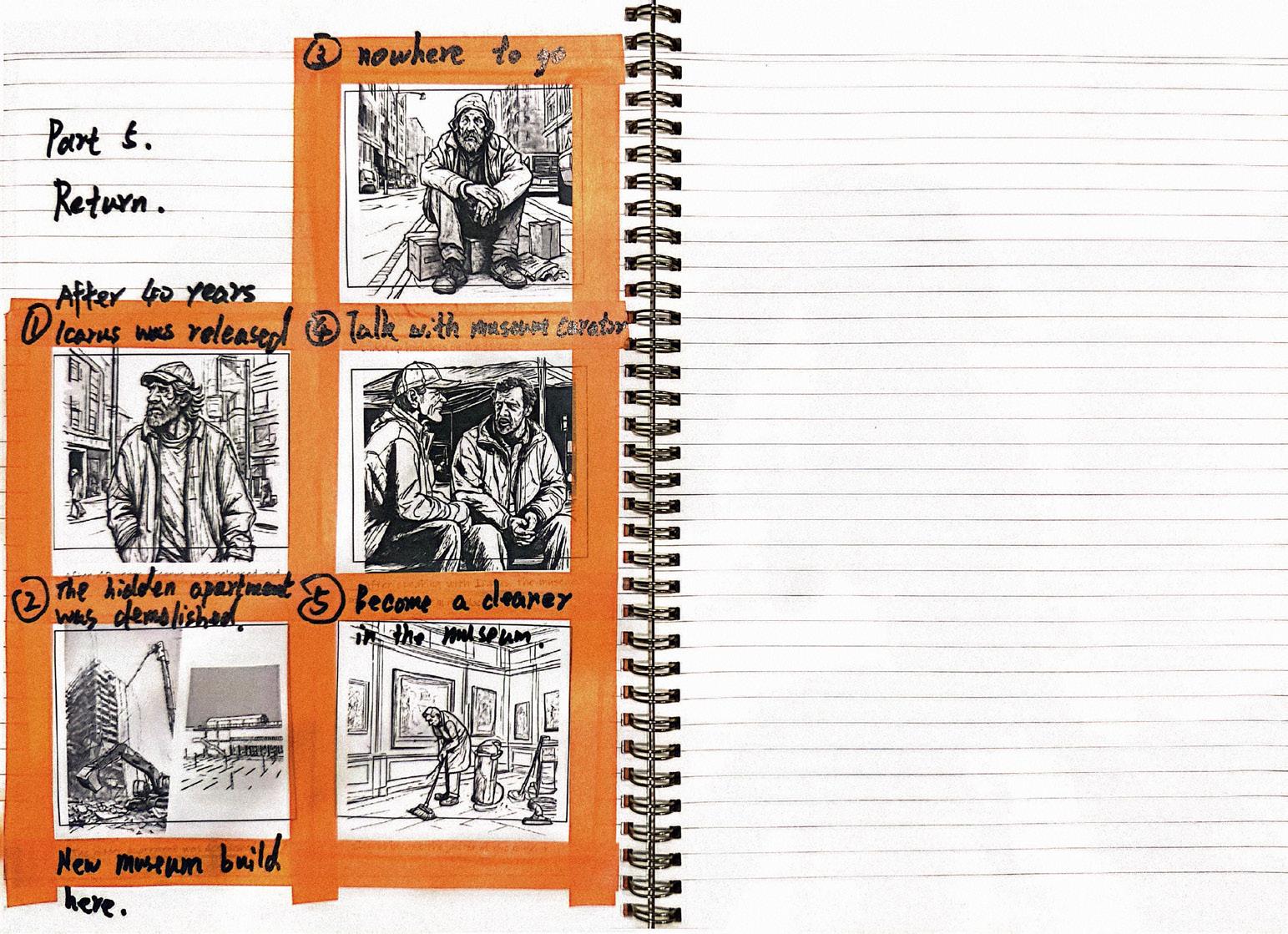

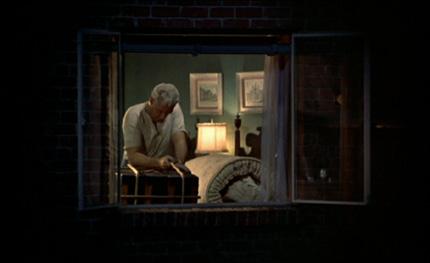

Since Icarus was a fugitive, he is sentenced to 40 years in prison. After his release, now a weathered 60-year-old man, his parents have passed away, and the world no longer resembles the one he once knew. Lacking any skills, he can’t even find a decent job. Aimlessly wandering, he unknowingly stumbles upon the site of the building where he once hid. However, the apartment has long been demolished and replaced by a newly built museum (the project I designed). His heart fills with a sense of irony and selfmockery. He often sits beside the museum, gazing longingly at the place that once brought him brief happiness.

The museum's curator (possibly me, haha) notices Icarus sitting there day after day and approaches him to chat. After learning about his experiences, the curator feels deeply sad and tells Icarus that this museum is dedicated to a movie (Clockwork Orange), and Icarus shares many similarities with the film’s protagonist, Alex. Out of sympathy and compassion, the curator invites Icarus to work as a janitor at the museum, responsible for cleaning. Icarus gladly accepts the offer and spends the rest of his life silently accompanying this place, staying close to Marina, who still lives in his heart, and the beautiful life he once yearned for.

Apartment symbolized the utopian ideals of modernism, representing a promise of a brighter future. However, that promise was shattered when the apartment was demolished, symbolizing the collapse of modernist architectural ideals.

After the apartment's demolition, the newly built museum becomes Icarus's workplace. This spatial transformation reflects Icarus's journey from a young man chasing dreams to a marginalized criminal, and finally to someone who finds redemption through labor. This transformation is closely tied to the trajectory of modernism itself. Modernism, once an idealistic vision, faced realworld disappointments but eventually found renewal through adaptation and reinvention. Icarus's life is a reflection of this process.

The museum, as a symbol of modernism, is given new meaning through Icarus's work. Though modernism’s utopian dreams were shattered in reality, it continues to exist in a different form, serving history and culture through the museum space. Icarus’s story reveals that modernist architecture is more than just a style or form; it carries the weight of personal and societal aspirations, losses, and rebirth.

This fictional building not only represents Icarus's path to personal redemption but also serves as a symbol of the shift from modernist ideals to their real-world manifestations. This dual narrative illustrates how the evolution of modernism intertwines with individual fate, deepening the connection between Icarus and the architecture.

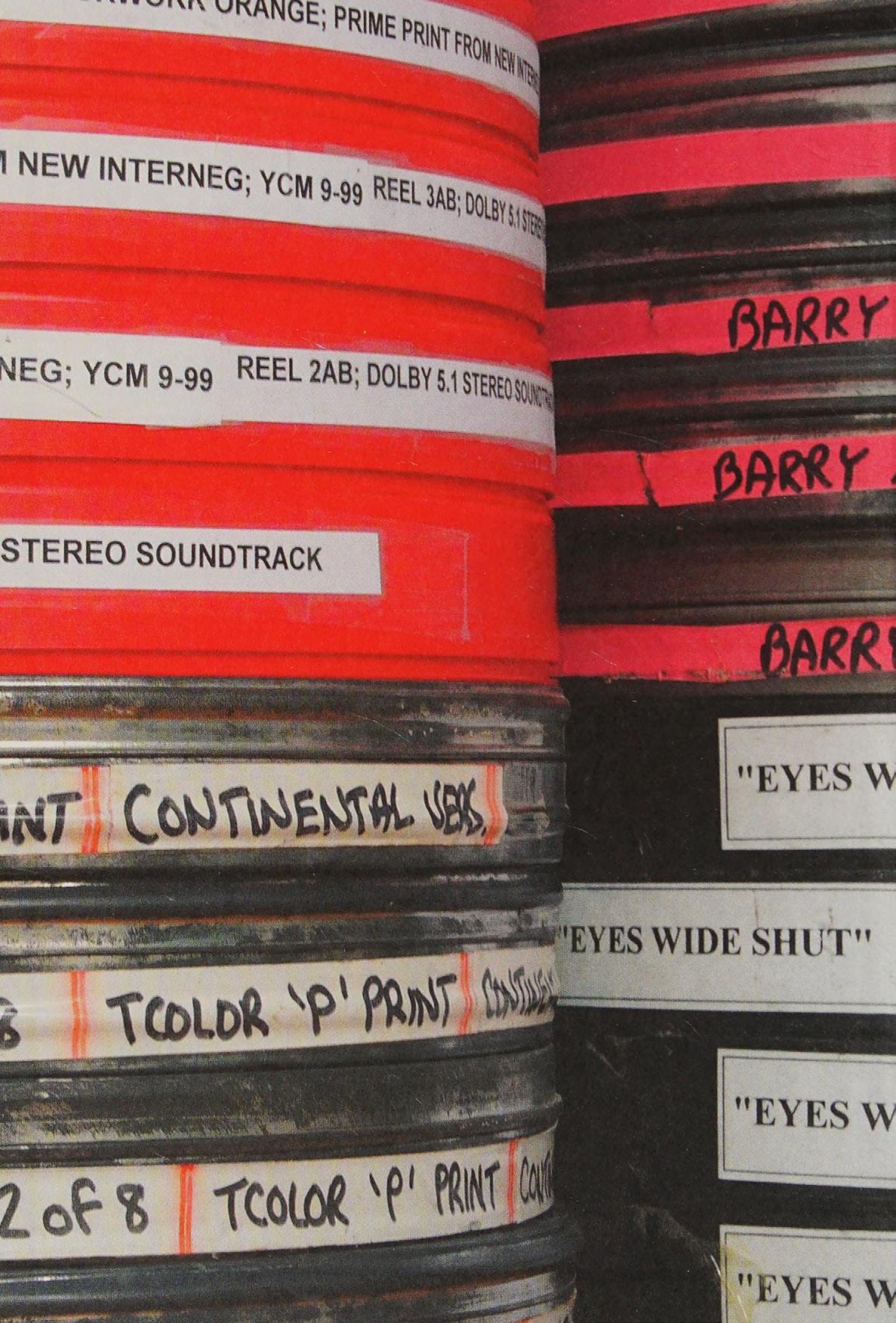

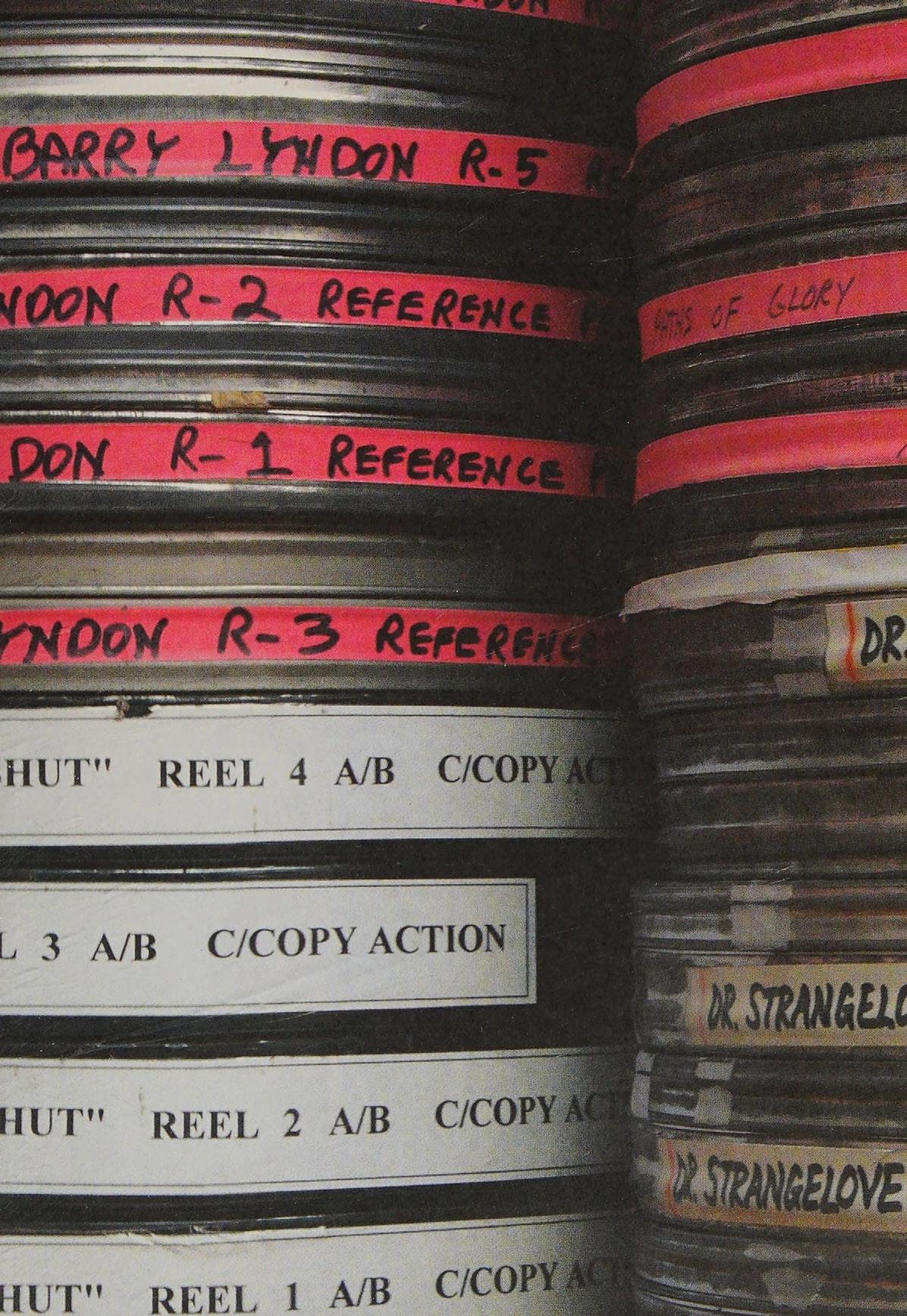

The exhibition will showcase the development, crisis, and redemption of modernist architecture through various mediums such as films, documentaries, photographs, furniture, and models. The exhibits will be displayed alongside scenes and actual furniture from the film A Clockwork Orange, directly connecting the film's narrative with architecture.

Furthermore, the museum reflects the complex relationship between the protagonist and modernist architecture as depicted in the film. The protagonist was imprisoned during the decline of modernism, marked by the collapse of the Pruitt-Igoe project, a symbol of the crisis in modernism. After his release, he witnesses the revival of modernism, driven by architects like Lacaton & Vassal. This historical backdrop intertwines with the protagonist's personal journey, showcasing his transformation from a "prisoner" of modernism to a "witness" of its rebirth.

This narrative closely links the protagonist's story with the development of architecture, illustrating his shift from a "prisoner" trapped in the rigid structures of modernism to a "witness" of its revival. By juxtaposing film elements with architectural history, the exhibition highlights the intertwined fates of the protagonist and modernist architecture.

3.2.2 THE TRANSFORMATION: PAST AND NOW

At first, the protagonist hides in social housing on the fringes of modernism. This social housing symbolizes the original intention of modernist architecture in the mid-20th century—to provide equal living spaces for the masses.

However, as the ideals of modernism gradually crumbled, the crisis of modernist architecture followed. In A Clockwork Orange, Kubrick also uses the chaotic public spaces in modernist buildings to reflect this crisis. At that time, buildings were criticized for being cold and disconnected from human needs, reflecting societal dissatisfaction and unrest.

In my movie. Icarus’s situation mirrors this: social housing is no longer an ideal utopia but rather a space of isolation and deprivation.

Pruitt-Igoe and Robin Hood Gardens are quintessential examples of the crisis in modernist architecture, highlighting the vast gap between idealized design and social realities.

Both projects followed modernist design principles, emphasizing shared public spaces and community cohesion. Pruitt-Igoe aimed to create interactive spaces for residents through wide public corridors and shared facilities, while Robin Hood Gardens sought to strengthen neighborhood ties with its "streets in the sky" concept, incorporating public walkways within high-rise buildings. These designs were intended to improve community atmosphere and quality of life through architectural form.

However, despite the idealistic intentions, these designs failed to achieve their goals in practice. Over time, the public spaces within these buildings not only failed to foster community cohesion but also became neglected areas, breeding grounds for crime and social issues. This reveals the disconnect between design principles and the actual needs of society, as the architecture was unable to adapt to the complex socio-economic changes.

The failure of Pruitt-Igoe and Robin Hood Gardens represents more than just the downfall of individual architectural projects; it symbolizes the limitations of modernist architectural ideals in social practice. While modernism emphasized functionality and community-building, its disregard for the complexities of social realities made it difficult to realize the original visions, leading to the dual collapse of both society and architecture. This demonstrates that architectural design must account not only for form and function but also for the socioeconomic context and its impact on how spaces are used.

Figure: http://www.pruitt-igoe.com/

3.2.2 THE TRANSFORMATION: PAST AND NOW

At the same time, Icarus is sentenced to prison.

Icarus's imprisonment is not only a symbol of his personal predicament but also a metaphor for the broader failure of the social and architectural system. This moment is closely tied to the decline of modernist architecture in the 1970s. Modernist architecture, with its overly rational and cold design principles, was increasingly criticized for being disconnected from human needs. Icarus's imprisonment symbolizes the oppression of individual freedom by this system, much like how many modernist buildings eventually restricted the living spaces of their occupants.

He represents not only a personal tragedy but also the social disintegration caused by modernist architecture. While this architectural philosophy aimed for functionality and order, it neglected human needs and ultimately became a "prison" that limited individual freedom. Icarus's loss of freedom mirrors the fate of modernist architecture, which collapsed under the weight of its failed design concepts, deepening the critique of the relationship between architecture and society.

Through this metaphor, Icarus's imprisonment is not just a turning point in his personal fate but also a symbol of the dual breakdown of society and architecture.

Figure 1: https://www.dezeen.com/2022/07/15/modernisms-death-greatly-exaggerated-opinion/

3.2.2 THE TRANSFORMATION: PAST AND NOW

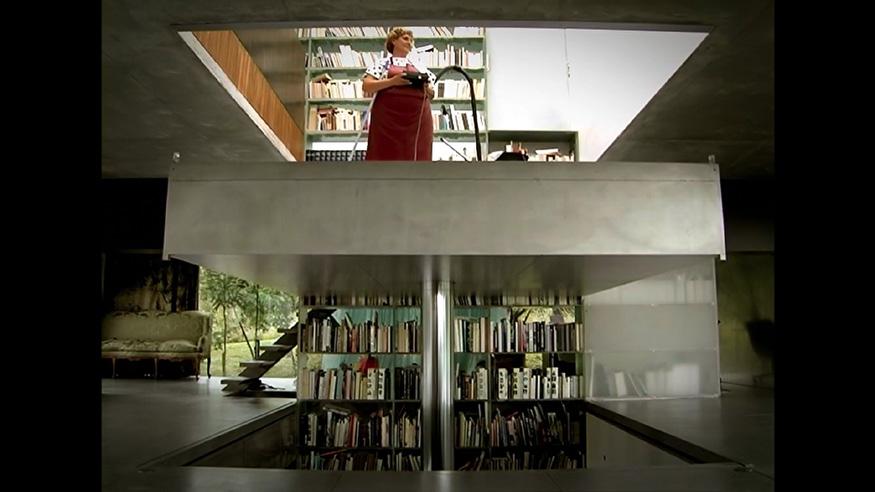

After Icarus is released from prison, his identity undergoes a fundamental transformation. He transitions from a marginalized criminal to a janitor in a museum, re-entering the system of modernist architecture. By cleaning and maintaining the museum—a symbolic representation of modernism—Icarus not only rebuilds his relationship with architecture but also finds a form of redemption through labor within the modernist framework. His work becomes the key to reintegrating into society, reflecting the reshaping of his identity and the mutual influence between him and modernist architecture.

Simultaneously, Lacaton & Vassal were awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize for their approach to modernist architecture, focusing on renovation rather than demolition, giving these buildings new life. Their practice rejects the simplistic idea of tearing down and rebuilding, instead opting to preserve and expand existing structures, allowing them to meet contemporary needs without losing their original value. This approach not only continues the legacy of modernist design but also enables the architecture to serve new social functions.

The revival of architecture parallels Icarus's personal transformation. Lacaton & Vassal’s renovation projects breathe new life into modernist buildings, just as Icarus, through labor, gains recognition within the social and architectural system, reshaping his role within the modernist structure. Both narratives reflect the theme of redemption through transformation rather than destruction: Icarus, as an individual, emerges from the shadows of his past through labor, while modernist architecture, through innovation and adaptation, reclaims its place as a functional part of society.

Figure 1: https://ideasandimages.wordpress.com/2007/12/13/on-the-surface-grit-of-fact-allure-of-fiction/ Figure 2: https://www.archdaily.com/958565/anne-lacaton-and-jean-philippe-vassal-receive-the-2021pritzker-architecture-prize

3.2.2

Icarus's labor forms a deep, interactive relationship with the revival of modernist architecture. His work is not just a means of livelihood but also the key to his personal redemption. Throughout this process, although he remains part of the modernist architectural system—perhaps even a "slave" to it—his labor allows him to reconnect with the architecture on both an emotional and functional level. This reveals a renewed relationship between him and the building, highlighting how modernist architecture shifts from being a tool of control and oppression to a space that serves people.

This transformation mirrors Lacaton & Vassal's approach to renovating social housing projects. By expanding living spaces and improving living conditions, they no longer view architecture as a tool to restrict personal freedom, but rather as a medium for enhancing the quality of life. Instead of demolishing existing buildings, they use innovative design to give these structures new purpose and meaning. This parallels the protagonist's journey of reintegrating into society through labor. Both narratives demonstrate that modernist architecture can be revitalized through adaptation to contemporary needs, just as the protagonist finds redemption through his work.

Figure 2: https://www.lacatonvassal.com/

A Clockwork Orange, Alex ultimately becomes a political tool for the government, symbolizing societal control by the state. His free will is stripped away by externally imposed reform, resulting in the loss of his autonomy and humanity, rendering him a passive instrument of the power structure. This fate reflects the suppression of individual freedom through extreme control in modern society, revealing the alienating effects of the modernist system on people.

In contrast, Icarus’s story presents a different path. While he survives under the modernist system through labor and partially depends on the architectural structure, his work offers him an opportunity to rebuild his identity and reconnect with society. Unlike Alex, who completely loses his autonomy, Icarus finds a new sense of identity and redemption through his labor. His interaction with the architecture becomes key to his self-realization. Although he remains within the modernist framework, he gains personal rebirth and a degree of freedom through his labor. This redemption, brought about through his interaction with architecture, illustrates the potential of modernist architecture to adapt and transform.

The revival of modernism is not just about controlling or manipulating the old system, as Icarus’s story shows. It requires innovative thinking and practical action to re-examine and transform existing architectural structures rather than simply oppressing individual freedom. Lacaton & Vassal’s architectural practice embodies this idea, as they breathe new life into modernism by renovating rather than destroying existing buildings, giving modernism renewed function and meaning. In contrast to modernism’s cold control, postmodern architecture emphasizes decoration and rich visual experiences, addressing psychological needs and breaking free from pure functionalism. This shift towards more human-centered and diverse architectural practices brought greater care and variety to building design.

Postmodernism, through the borrowing of historical symbols and eclectic approaches, broke the uniformity of international style, emphasizing ornamentation and visual diversity. It moved architecture away from the rigid functionalism of modernism toward more humanized and diverse directions. Similarly, Icarus’s labor symbolizes the possibility of seeking redemption through innovation and work within the established modernist framework, demonstrating a reflection on and transcendence of existing systems. This reminds us that true architectural revival is not merely a disruption of form, but a response to and respect for human needs.

Figure 3: https://www.jencksfoundation.org/explore/text/writing-from-the-battlefield-charles-jencks-andthe-language-of-post-modern-architecture

3.2.2 THE RELATIONSHIP: FROM CONTROL TO REDEMPTION

The setting of Icarus's work—the museum—symbolizes the revival of modernist architecture. Here, the protagonist’s role as a laborer is closely tied to the rebirth of modernism. His work is not only about maintaining the building but also about renewing and revitalizing the ideals of modernism. This shift in the relationship suggests that the revival of modernist architecture is not just a change in form, but a redefinition of the function and social significance between architecture and people.

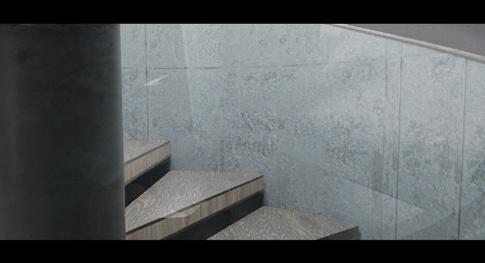

SECTION A 1/200

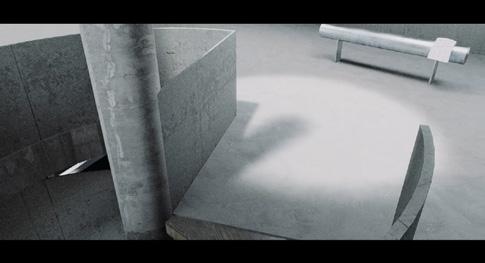

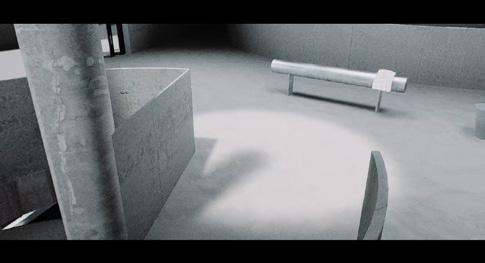

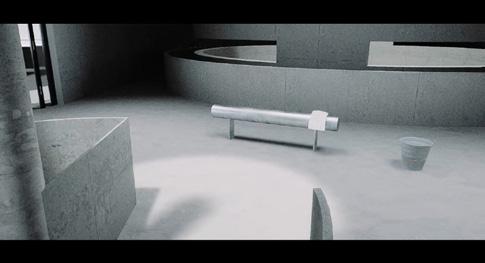

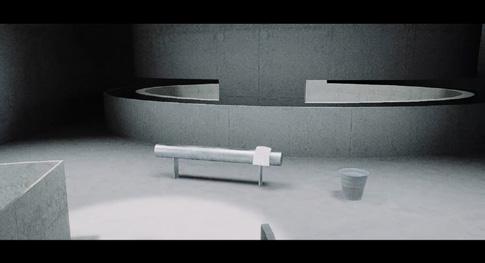

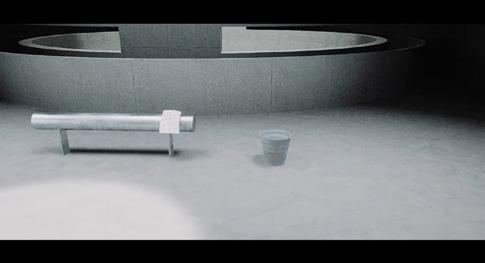

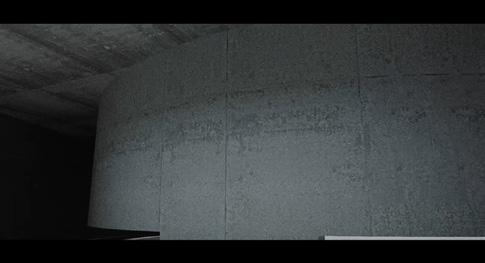

In the rendered design images, the project presents the building's interior from the protagonist Icarus's perspective, using cleaning tools and staged scenes to highlight labor within the space. These visuals depict Icarus preparing for the exhibit’s opening by cleaning and moving items, and show him dining in the break room. Such details enhance viewers' immersion, helping them feel his journey of self-redemption through labor. This progression not only symbolizes personal renewal but also reflects architects’ mature efforts to achieve “redemption” in modernist architectural evolution.

This parallel expresses architecture as more than a functional space; it is a vessel for ideas and emotions. Through form, materials, and spatial storytelling, architecture conveys specific thoughts, feelings, and cultural values. This approach serves as a critical response to modernist architecture and highlights labor's crucial role in modernist revival, illustrating a profound artistic dialogue between “Total Art” and architectural design.

The project ultimately takes form as a film, gradually moving away from Kubrick's style to delve deeply into architectural interior narratives. The film presents Icarus’s experiences as a museum janitor, giving narrative depth to the architectural space. This use of cinematic language expands traditional architectural representation beyond drawings, engaging in a cross-disciplinary dialogue between architecture and cinema. It explores how cinematic techniques can be adapted into architectural aesthetics, illuminating the ongoing evolution of modernist architecture.

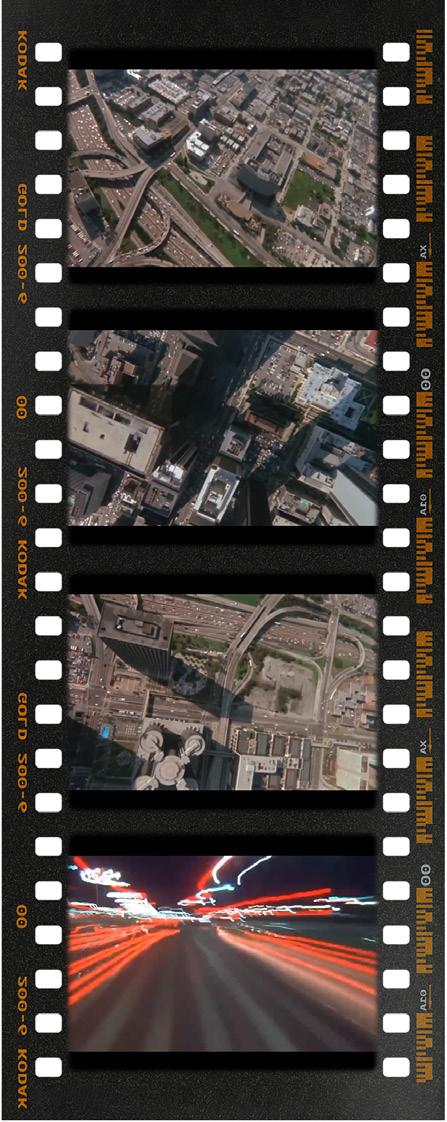

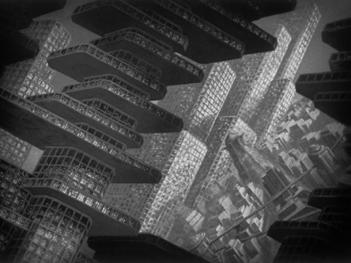

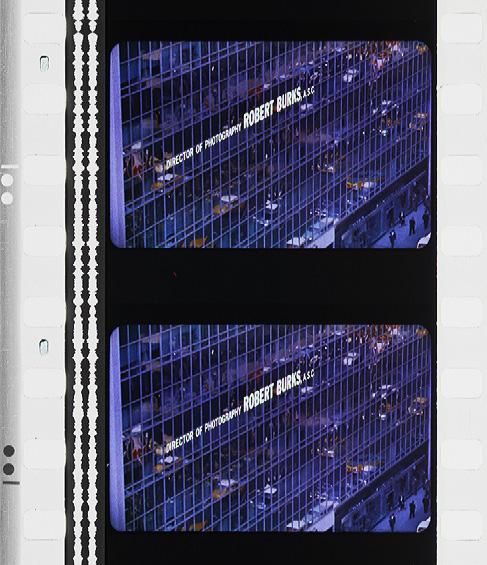

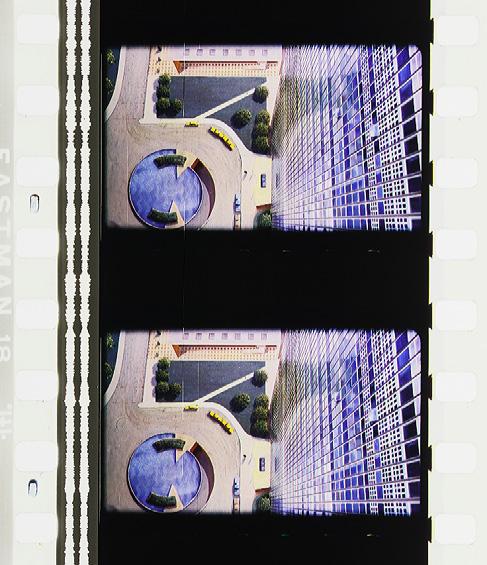

The film opens with a sequence of shots depicting the development of contemporary urban landscapes. The aerial shots convey the vastness and isolation of the city, while the high-angle perspective evokes a sense of unsettling weightlessness. This sequence contrasts sharply with the subsequent scenes of modernist architecture in decline, suggesting a deeper sense of imbalance.

As time flows backward, the scenes transition to the 1970s, where shots of modernist architecture's rise and fall appear in juxtaposition, creating a striking visual contrast. Dirty piles of garbage and leaking rooms seem to narrate the reasons behind modernism’s demise. This aligns with my research findings: the small, isolated spaces of modernist design severed connections between individuals and public spaces, as well as between people and the land, leading these communal areas to fall into disorder, lacking management and structure.

This sequence uses the demolition of the Pruitt-Igoe housing complex to depict the end of modernist architecture. Initially, the project embodied the ideal vision of modernist urban planning, a utopian design aimed at creating a harmonious community. However, it ultimately failed to overcome the complexities of the real-world environment and human nature. Over time, these buildings came to be known as a “nightmare,” and eventually turned into a breeding ground for crime, with residents struggling in unbearable living conditions. Eventually, under mounting public pressure, the government decided to demolish the complex. With the fall of Pruitt-Igoe, Charles Jencks declared this moment as the “death of modernist architecture.”

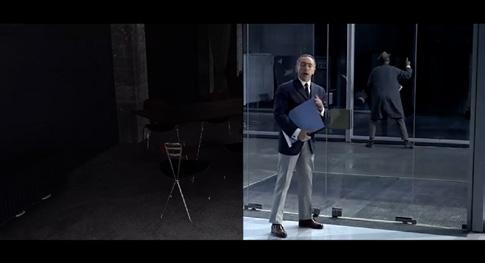

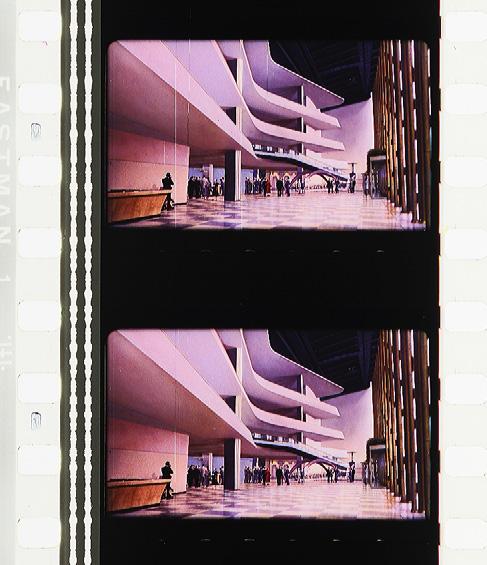

Chapter One primarily depicts Icarus’s first day working at the museum. The automatic opening of the curtains symbolizes the start of a new day and the unveiling of his new life. This automated building feature also foreshadows the increasingly automated labor methods brought by advancing technology.

The camera follows Icarus’s gaze as he surveys the ground floor exhibition hall: cluttered display stands, unopened exhibits, and cleaning tools scattered around — all reflecting Icarus's inner sense of chaos and nervousness. The background music, marked by rapid drum beats, further intensifies this atmosphere of tension.

Having spent a long time in prison, Icarus is clearly out of touch with the outside world, and many ordinary things seem novel to him. When his eyes fall upon a smart control panel, a parallel scene appears, showing people in the last century operating integrated control panels to manage building air conditioning and other appliances. Back then, people operated complex buttons and switches, but still had to manually adjust airflow and temperature. This almost comical scene subtly critiques early modernist limitations. Although modernist building technologies claimed to improve quality of life, they failed to meet basic needs, instead adding new inconveniences and confusion. Now, building technology has become more user-friendly, focusing on practicality and functionality, moving toward modernism’s “self-redemption” by prioritizing comfort and human-centered care over rigid functionalism.

Next, Icarus’s gaze shifts to an automatic floor-cleaning robot. This robot can automatically identify and categorize floor debris, such as solid waste and liquid spills, performing precise cleaning based on the type of dirt. In contrast, the screen displays older cleaning scenes where workers would search for debris with their eyes, even using flashlights to illuminate hard-to-reach corners.

First Day

Icarus’s gaze is drawn to a flying object, and he refocuses his vision with a hint of curiosity and unease, as he doesn’t quite understand what it is. He then begins to scan the hall on the first floor, and the camera meticulously captures the textures on the walls and the scuff marks on the floor, highlighting the intricate details of the building.

A graffiti-covered trash bin catches his eye, bearing strong traces of the industrial era. The graffiti on the bin is not just a form of personal expression; it also reflects the shift in people’s attitudes toward modernist architecture, from a functional focus to a demand for human-centric design—a transition from initial reverence to later skepticism and introspection. Faced with modernism's pursuit of uniformity and simplicity, people grew weary and used graffiti to achieve a sense of personalization and artistic differentiation.

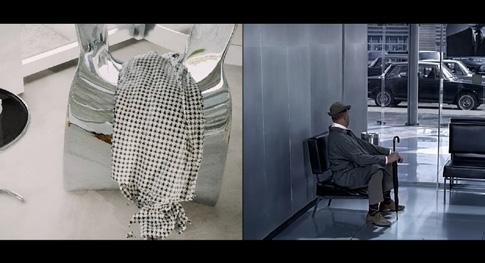

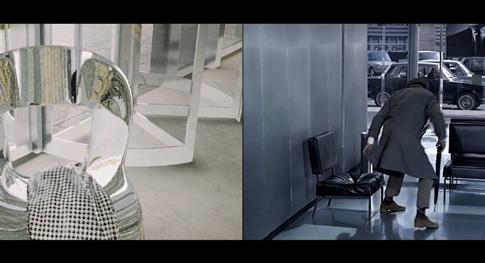

Next, a lightweight, semi-transparent partition blocks Icarus's path, and his attention is drawn to a classic Barcelona chair—a signature piece of modernist design and an iconic example of “form follows function,” exemplifying modernism's commitment to functionalism. The sight of this chair brings Icarus back to his past, to a similar chair in a home he once stole from, a cold and monotonous apartment where he hid from the world. Now, he seems to feel once again the suffocating confinement of those four walls. This is the power of architecture—it carries not only a lifetime but, at times, an entire era.

In sharp contrast to this is the postmodern-style metal chair beside it. This chair emphasizes sensory experience, abandoning “function first” in favor of a focus on unique design and material texture. Its curves and metallic sheen create visual tension, breaking free from the rational constraints of modernism. This design seeks a new balance between aesthetics and utility, embodying postmodernism’s attention to personal expression and emotional needs.

Icarus seems to find his own state of mind between these two chairs—on one side, the cold restraint of the past, and on the other, a future full of possibilities. Modernism continually sought self-redemption through the separation of form and function, while the advent of postmodernism further reminds us: life is not merely an assembly of functions; it also requires a space for emotions.

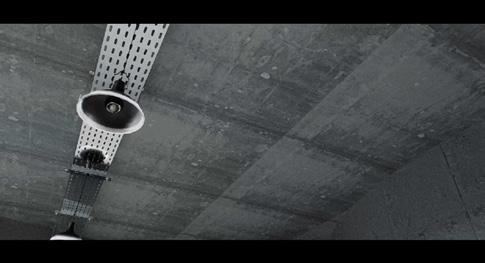

In this chapter, Icarus, with a mixture of excitement and apprehension, begins operating a drone to clean the tall glass walls. It’s his first time coming so close to a piece of technology, and the experience feels surreal, almost dreamlike, as it surpasses his traditional understanding of tools. In his mind, many tools still belong to the modernist era—designed to prioritize functionality, often rigid and lacking in personalization or human-centered considerations.

This scene feels both novel and unsettling, as it shatters his preconceived notions about tools. The drone is not just a tool; it symbolizes the liberation of labor, allowing him to shift from pure physical labor to an active role as an operator, no longer a mere extension of the work. At this moment, technology is not only transforming the way labor is performed but also adding new meaning to it—moving from mechanical repetition to intelligent control. Technology allows labor to become less of a burden and more of a form of engagement and collaboration, giving people greater agency and freedom within their work.

These new machines embody the continuation and transcendence of modernism's "function-first" philosophy. They move beyond single-purpose use to adapt to the diverse needs of people, reflecting a more flexible, inclusive approach to modern architecture and lifestyle.

In this chapter, Icarus is responsible for setting up the temporary exhibition space on the rooftop level. Each quarter, this space hosts an artist who creates works themed around "the decline, death, and rebirth of modernism." This diverse array of artistic displays broadens the public's perspective, moving beyond a focus on the physical architecture itself and encouraging viewers to consider the vast ideological framework and impact of modernism.

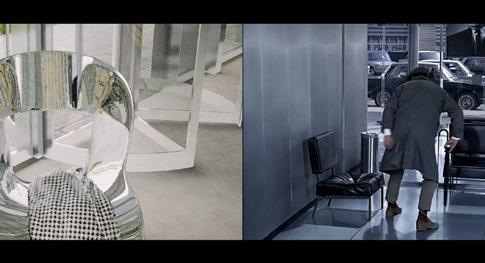

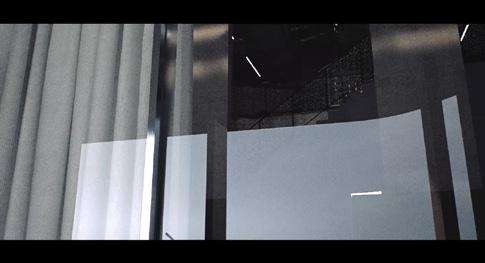

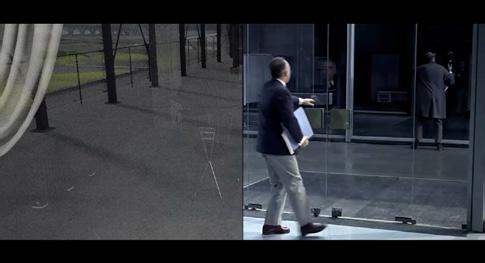

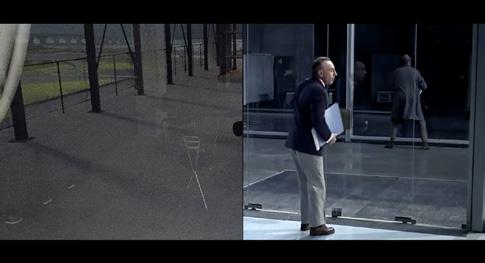

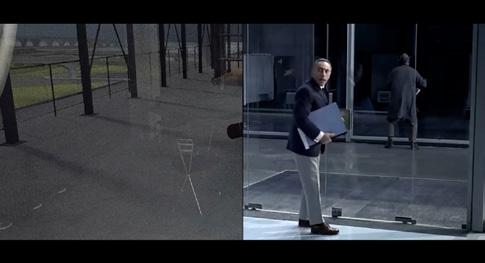

As Icarus approaches the glass, the intense glare prevents him from clearly seeing the interior space. Perhaps he intends to observe the activities inside or determine if cleaning is required, but with the interference of sunlight, he must lean closer to the glass, shading his eyes to glimpse the blurred interior. Meanwhile, a parallel scene plays on the screen: in a subtly satirical video, an elderly man searches for a middle-aged man. Although both are in the same space, the glass reflection misleads the elderly man into thinking the middle-aged man has entered another room.

This misunderstanding caused by architectural design seems to critique the designer's rigid focus on form, their pursuit of rationality and aesthetics, while overlooking the actual needs and experiences of users. This sequence symbolizes modernism’s limitations: the overemphasis on design principles and idealized forms often neglects the complexity and human needs inherent in real-world architectural use. Through this constructed scenario, the film critiques modernism's overly rational tendencies, inviting the audience to question how architecture can balance form and function.

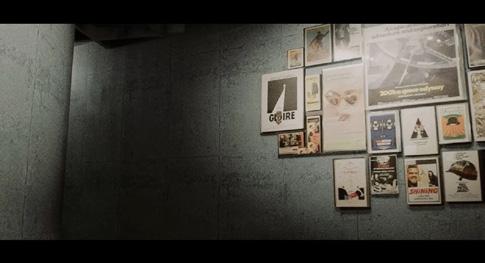

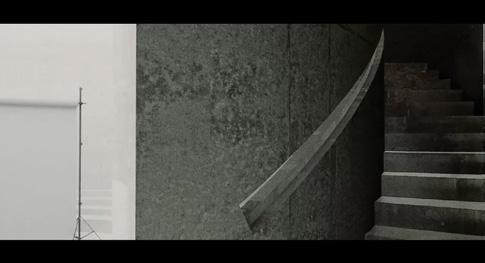

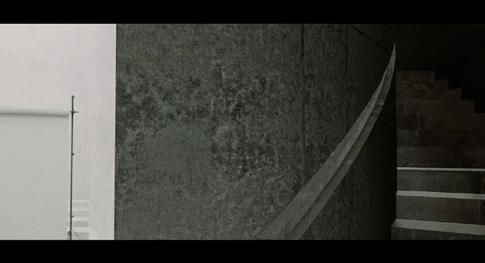

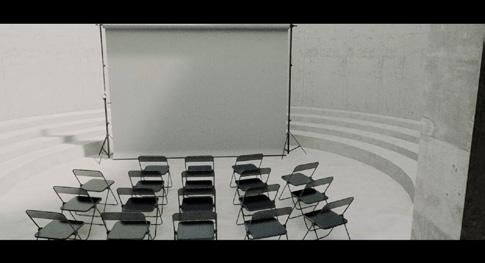

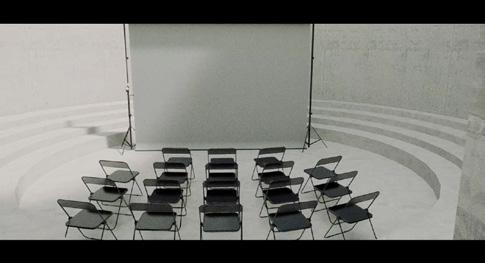

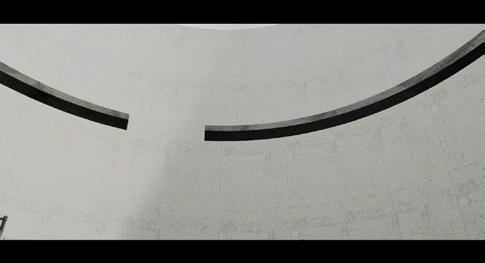

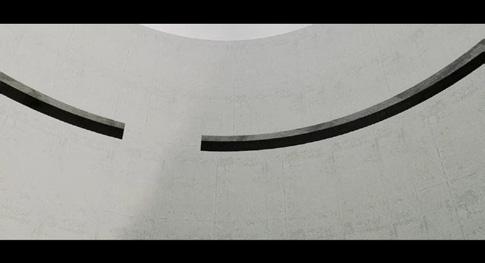

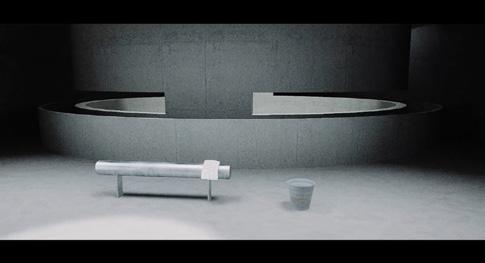

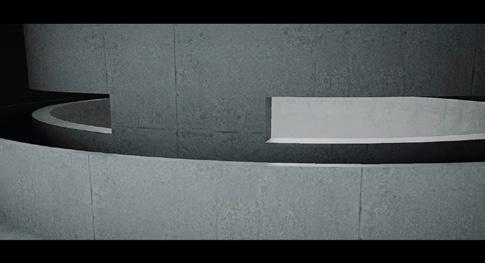

The camera follows Icarus’s gaze to the cinema area, a space primarily dedicated to screening Kubrick’s films as well as documentaries on the evolution of modernist architecture. The cinema’s design is symmetrically structured and symbolically inclined, with an open-air circular layout that breaks away from traditional cinema constraints. Although this design may bring some inconvenience to the viewing experience, it reflects the designer’s attitude toward modernist architecture—a desire to break conventions and explore new possibilities. Much like OMA's famous floating cinema, this design challenges the notion that a cinema must be indoors, with the designer pushing boundaries through a nontraditional approach.

Icarus seems to notice this as well, curiously examining the unadorned cinema and the peculiar wall openings. The minimalist design, coupled with these unusual details, sparks his curiosity, and he begins to wonder about the purpose or symbolic meaning behind these openings. This design is not only a challenge to conventional cinema form but also a critique of the rigidity in modernist architecture, encouraging viewers to appreciate the potential and diversity of space from a fresh perspective.

The film’s ending lingers on a scene of Icarus sitting alone beside a machine, smoking, with an expression that reveals both exhaustion and bewilderment, as if a day of mechanical labor has quietly fused him with his surroundings. He sits silently in this technology-driven space, becoming a silent cog in the functioning of the architecture—symbolizing the way modernist architecture integrates individuals into its functional systems.

As night gradually falls, this scene forms a poignant visual closure with the opening shot of the curtain being drawn open. A day's work comes to a quiet end, while the city continues its unending operation along the tracks of technology. This quiet yet tense moment leaves the audience with ample space for reflection: Has Icarus, through his labor after being released from prison, achieved a form of self-redemption? After its decline, has modernist architecture found a new opportunity for rebirth within this functional framework? These intertwined themes of technology and labor, architecture and life, prompt viewers to consider whether modernist design can truly address the human needs of contemporary society, or whether it continues to discipline the individual, reinforcing a new form of submission.

Moreover, could technology itself be emerging as a new kind of modernist ideology, gradually shaping society into a technologically dominated, mechanized world? This scene hints at a possibility: technology is not merely a tool but is becoming a dominant force, forming a modernist metaphor centered around technology—a society increasingly regulated and shaped by the mechanics of a technological order.

I believe that each person will have their own unique thoughts and interpretations after watching this film. I define this film as a form of art documentary, as it, in a way, captures an imagined architectural space. While it incorporates elements from Playtime and other existing footage, it can also be viewed as an art film—an expanded exploration of architectural expression.

In this film, architecture is not merely the presentation of space; it serves as a narrative medium. Through distinctive visual language and narrative structure, the architecture is imbued with emotion and symbolism, blurring the line between reality and fiction. The spatial experience of architecture transcends its physical form, becoming an extension of visual storytelling. Every step Icarus takes and every touch he makes is not just an exploration of the architecture itself but a search for the relationship between architecture, the individual, and society.

This approach offers a fresh perspective on the value of architecture: it is no longer simply a physical structure for use but a composite of history, culture, and social psychology. Through this film, architecture’s narrative dimension is revealed—not only presenting the physical shell of modernism but also reaching into its underlying ideological framework and human concerns. Here, architecture becomes a vessel for time, evolving through technological advances and experiencing a transition from modernism to postmodernism to the present. The film, within this transition, captures how architecture continually renews itself amidst societal change.

In the final design, I added rendered images of the exhibition layout to reinforce the narrative quality of the design, showcasing the intent and connections of each exhibit within the space to help viewers gain a deeper understanding of the exhibition’s theme. Through the delicate interplay of light and material textures, these renderings enhance the immersive quality of the scenes, allowing viewers to experience the exhibition content as if they were physically present.

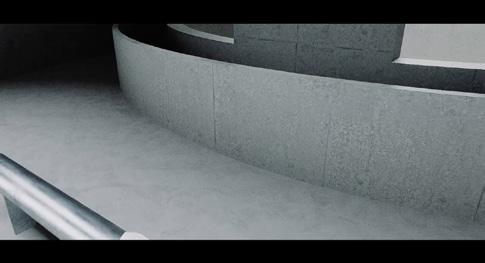

The rough concrete walls contrast sharply with the sleek metal structures, creating a stark industrial aesthetic that reflects the rational beauty of modernist architecture. Traditional walls have been replaced with lightweight transparent partitions and gauze curtains, breaking away from conventional spatial divisions. The transparent partitions have a refined, subtly reflective quality that interacts with the surrounding light, producing soft shadows and adding depth to the space. The gauze curtains, meanwhile, appear semi-transparent and airy under the lighting, forming a blurred boundary that preserves the individuality of each area while fostering subtle connections between them. This design approach makes the space visually open, creating a sense of seamless continuity.

This transparent design language further enhances the theme, organically integrating the architecture with the exhibition content and lending the space a lighter, more rhythmic expression.

This design development takes inspiration from A Clockwork Orange, exploring the themes of modernism's crisis, decline, and rebirth. Icarus, the central character of the narrative, serves as the focal point of the design, allowing us to examine the interplay between space and time, architecture and the individual. By creating a script and producing a film, we not only constructed a virtual architectural space but also explored the intersection of film and architecture as artistic expressions.

In this project, film as an art form provides a unique perspective for expressing architecture. Guided by cinematic language, the materials and spatial qualities of the design are vividly portrayed, infusing the architecture with narrative and emotional depth. Here, architecture exists not only as a physical space but also as a narrative medium shaped by the film’s visual language, enabling viewers to experience the architecture through the flow of time and visually perceive its nuanced materials, spatial composition, and ambiance.

This project attempts to explore how film and architecture complement and intertwine as modes of artistic expression, illustrating how architecture can be reinterpreted through cinematic language and how film can use architectural spaces to convey emotion and themes. This experimental design bridges the realms of film and architecture, allowing architecture to reveal its artistic tension in light and shadow, creating a dialogue between vision and space.

Architecture and Cinema

Gesamtkunstwerk refers to the creation of a unified, immersive aesthetic experience through the integration of multiple art forms. The 19th-century composer Richard Wagner first introduced this concept to blend music and drama; later, the idea expanded to encompass diverse art forms, including architecture and film (Wagner 1981). As distinct art forms, film and architecture each convey space, emotion, and narrative through their unique mediums, creating a complex, symbiotic relationship within the Gesamtkunstwerk framework that allows them to merge and amplify each other's strengths.

Film's multidimensional nature enables it to adopt expressive qualities from other art forms, enhancing its capacity to convey complex emotions and spatial experiences. As Jean-Luc Godard once said, “There are many ways of making a film. Jean Renoir and Robert Bresson make music; Sergei Eisenstein paints; Stroheim writes a novel with silent images; Alain Resnais sculpts; and like Socrates, Rossellini creates philosophy. In other words, cinema can be everything at once, both judge and claimant” (Pallasmaa 2001, 47). This highlights film’s diversity and depth, suggesting an alternative mode of expression: film as architecture. Film’s multidimensionality allows it to reveal the spatial and emotional essence of architecture, creating a relationship that enriches both art forms.

This chapter will explore the ways film and architecture complement each other within the Gesamtkunstwerk framework, examining three aspects: spatial shaping, emotional conveyance, and narrative construction. This interdisciplinary perspective not only reveals the potential for integrating film and architecture within Gesamtkunstwerk but also offers insight into the practical and conceptual limitations of this integration.

Film, as a multidimensional art form, captures and conveys the layers and flow within architectural spaces through dynamic camera language. By utilizing camera movements, angle shifts, and the interplay of light and shadow, it brings a vibrant quality to architectural spaces. Through the lens of cinema, viewers can not only perceive the physical structure of space but also appreciate the layout details, enhancing the atmosphere and emotion created by the film¹ .

4.1 SHAPING SPACE THROUGH DYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE

The following atlas showcases selected frames from my original film Revibloom. These still shots use camera motion and carefully designed perspectives to reveal the structure, depth, and interaction between architectural spaces and their users. This cinematic storytelling approach dynamically presents the design intentions and spatial qualities of the architecture, guiding viewers to gradually form an understanding of the space.

In these frames, techniques like zoom, panning, and tracking shots express the layered and interconnected nature of architectural space. The camera’s movement from distant to close-up allows viewers to “enter” the architecture, starting with an overall view of the structure and then gradually experiencing the details and textures up close. This progressive camera motion not only conveys the functional layout of the architecture but also enables viewers to sensitively perceive material transitions. For example, a zoom shot moves from a spacious gallery into a narrow staircase, gradually revealing the shift from public to private space. This guided experience allows viewers to sense the emotional shifts and layered design logic within the architectural space.

4.1 SHAPING SPACE THROUGH DYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE

Figure 1-2: https://www.archdaily.com/92321/ad-classics-parc-de-la-villette-bernard-tschumi?ad_ medium=gallery

Dennis Gassner, the art director of Blade Runner 2049, believes that architects and filmmakers can cross over into each other's creative fields due to their shared approach to spatial expression. This similarity is evident not only in their handling of external aesthetics and atmospheric control but also in their common ground in spatial narrative and design methodology. Film presents space visually, transitioning, connecting, and blending from one scene to another, much like how architects use spatial layout to tell stories¹. During the editing process, filmmakers reorganize spatial sequences, crafting a series of layered life images that allow viewers to gradually construct a complete understanding of the scene through visual experience and imagination2

Similarly, architects rely on organizing spatial sequences in their designs, using spatial transitions, transformations, and connections to integrate parts into a cohesive whole. Both film and architecture depend on continuity and depth of space to blend separate spatial fragments into a unified experience, creating an immersive effect for viewers. This approach to spatial storytelling brings film and architecture into a state of synergy within the framework of a "total work of art"³ .

4.1 SHAPING SPACE THROUGH DYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE

4.1 SHAPING SPACE THROUGH DYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE

The unique dynamism of cinematic language breaks through the limitations of architectural drawings and static models, presenting space with a multidimensional quality. The camera in film is not merely a container for displaying space statically; rather, it guides and controls the viewer’s experience. By shifting between high-angle, low-angle, and eye-level shots, the camera offers diverse spatial perspectives, allowing viewers to experience architecture beyond two-dimensional or three-dimensional spatial imagination and enter a space of emotional resonance¹ .

The diversity of dynamic shots enhances the spatial experience in architecture. Techniques like zooming, panning, and tracking shots dynamically showcase the relationships between interior and exterior spaces, spatial structure, and flow. These methods help the audience to construct a three-dimensional understanding of the spatial layout on screen. For example, in Playtime, director Jacques Tati uses long takes and panoramic shots to illustrate the open spaces of modernist architecture, revealing the authentic experience of architectural design in everyday life2. This use of dynamic shots enables viewers to gradually understand architectural space from different perspectives, enriching their overall perception.

This dynamic presentation of space allows film to create a fluid spatial experience, liberating architecture from its physical framework. Through camera movement, architectural space becomes flexible and vivid in the viewer’s eyes, with emotions and narratives flowing naturally within the rhythm of the space, achieving an experiential effect that traditional architectural drawings cannot reach³. The dynamic portrayal of architectural space in film intertwines narrative and visual representation, providing an immersive experience for viewers and introducing new perspectives to architectural research and design.

4.1 SHAPING SPACE THROUGH DYNAMIC PERSPECTIVE