FIG.3 [OPPOSITE]

William Bell Scott 1811–1890

Self-portrait, 1861

Watercolour over pencil on paper, 28 × 22.9 cm

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

FIG.4 [ r IGHT]

William Bell Scott 1811–1890

Letitia Convalescing, 1838

Pencil on paper, 23.8 × 20 cm

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

decorate the Palace of Westminster, which was being rebuilt following a devastating fire in 1834. Although he was unsuccessful, his talent was recognised and he was offered the post of Master at the recently founded Government School of Design in Newcastle-upon-Tyne.

Scott soon became a member of the artistic establishment in Newcastle. But his life took a new direction in 1847 when he received a letter from the precocious young poet and painter Dante Gabriel rossetti, complimenting him on his poetry. This marked the beginning of a lifelong friendship, with Scott – or ‘Scotus’ as he was nicknamed –fraternising with rossetti and the Pre-raphaelite circle on his annual

James Drummond 1816–1877

King James I While a Prisoner at Windsor and the Lady Jane Beaufort, 1851

Oil on canvas, 102.4 × 84.5 cm

royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh

John Everett Millais 1829–1896

The Love of James I of Scotland, 1859

Oil on canvas, 104.1 x 53.3 cm

Private collection

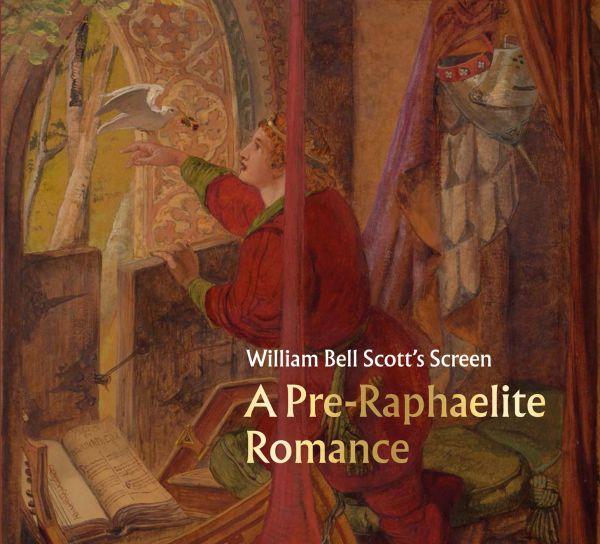

FIG.10 [FOLLOWING PAGES]

William Bell Scott 1811–1890

Old Windsor – Early Morning, from The King’s Quair, 1867–68 Bodycolour, oil paint and glaze on paper, on canvas and wood support, 183.7 × 57.7 × 2.5 cm

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

that publications by the historians Walter William Skeat and William Mackean were planned. He did, however, write a version of the poem in ‘modernised’ English, with the aim of making it more accessible to nineteenth-century readers. He quoted from this in an essay that accompanies a folio of etchings of the King’s Quair mural, which he published privately in 1887 and gave to friends. Excerpts are included in the following descriptions of the screen.18

Old Windsor – Early Morning

The first leaf of the King’s Quair screen, titled Old Windsor – Early Morning, represents the opening verses of the poem [fig.10].19 Here King James recounts how he had been unable to sleep one night while in captivity in Windsor Castle. Instead, he spent the time reading The Consolation of Philosophy (c.524), a work that was written while its author, the roman philosopher Boethius, was also a prisoner. The next day, when James heard a bell toll for morning prayers, he imagined that it was telling him to write down his own story. Scott’s pictorial scheme opens with an inscription in the top left corner of the leaf: ‘Here begins the Story of King James and the Lady Jane / 1420’ [fig.11]. In the foreground, on the left, the work’s title, Scott’s initials and the date ‘1867’ are recorded as if carved in stone, and adorned with stems of foxglove, iris and rose [fig.12]. The lower section of the leaf reads, ‘The bell rings for matins / The warder blows his horn / the night-watch goes h[ome] / King James in his prison calleth upon the nine’, referring to the Nine Muses of poetic inspiration from ancient Greek mythology. These words are decorated with designs of elder, oak and birch.

The scene is set at Windsor Castle, with the river Thames, the rooftops of the town and the bell tower in the middle distance. On the right, King James is portrayed in the window of his cell, writing his poem with a quill on a sheaf of pages. Beneath him is a large bronze statue of Boethius, with his ‘book of consolations’.20 The guards of the night-watch process along the battlements bearing aloft their breakfast. They hold a

heroine of a poem by Edmund Spenser, The Faerie Queene, Part I (1590), who tames a fierce lion with her beauty, Boyd is shown with her dark hair rendered as blonde and accompanied by her pet chaffinch, Bouby.

In July 1860, Scott first visited Penkill Castle, Boyd’s ancestral home [fig.30]. Situated in the Carrick Hills, above a steep wooded glen, approximately three miles from Girvan in Ayrshire, this fortified tower house – a building traditional to the border regions of Scotland – was constructed for the Boyd family around 1532. In the mid-eighteenth century it fell into ruin, but Boyd’s elder brother, Spencer Boyd (1823–1865), who inherited the estate as a child in 1827, determined to restore it. Funded by their maternal grandfather, the Newcastle industrialist William Losh, the roof was replaced and the interior redesigned to plans by the Glasgow architect Alexander George Thomson (1823/24–1904). The most significant addition, completed in 1858, was an impressive circular stair-tower with a crenellated parapet.

The King’s Quair mural

After Scott retired from his teaching post in Newcastle in 1863 and moved with Letitia to London, it was arranged that Boyd should spend the winter months with them, and, in return, they would visit Penkill each summer season. However, when Spencer died unexpectedly in 1865, Boyd became the next laird, or landowner, of Penkill Castle.35 Eager to continue Spencer’s programme of renovation – and now seeking an excuse to spend time with Scott – Boyd requested that he paint a mural on the interior wall of the staircase that spirals from the ground to the top floor of the stair-tower [fig.31]. The subject that they chose was The Kingis Quair. King James’s poem was highly appropriate to

FIG.28 [ABOVE]

Unknown photographer

Alice Boyd (left), William Bell

Scott (centre) and Letitia Scott (right) in the entrance to Scott’s Newcastle studio, 1860 Salted paper print, 18.3 × 13.3 cm

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

FIG.29 [OPPOSITE]

William Bell Scott 1811–1890

Una and the Lion, 1859–60 Oil on canvas, 91.5 × 71.2 cm

National Galleries of Scotland, Edinburgh

that Scott had him in mind when portraying King James. rossetti was one of Scott’s closest friends at this time, as recorded in a photograph of them with the critic John ruskin [fig.34]. Indeed, Scott’s visualisation of James, who was a painter of miniatures as well as a poet, recalls rossetti’s self-portrait of 1847, as he looked when Scott first knew him [figs 31, 35].42 While the figures in the King’s Quair screen are considerably smaller than those in the mural, James Leathart is certain to have understood this allusion to an artist whose work he avidly collected. The conceit may explain an intriguing inscription that appears in the screen, but not in the mural. On the roof above James’s prison window are written the words ‘The Evil Genius’, next to a large black bird [fig.36]. rossetti kept an aviary, including a pet raven. He was also obsessed by the poem The Raven (1845) by Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), producing a series of drawings on the subject. In the poem, the raven – described as a ‘thing of evil’ – invokes the spirit of the narrator’s dead lover, Lenore.43 Around the time that Scott created the screen, rossetti frequently attended séances in the hope of communicating with his wife, the artist Elizabeth Siddall (1829–1862), who had died in 1862. Scott – a sceptic – accompanied him on several occasions, and later referred to a spiritualist medium whom he distrusted as ‘the evil genius’ in his Autobiographical Notes. 44 The inscription, therefore, may be an example of teasing – or ‘chaffing’ as the Pre-raphaelites termed it – which Scott included to amuse Leathart, with whom he shared gossipy anecdotes.

FIG.35 [ABOVE]

Dante Gabriel rossetti 1828–1882

Self-portrait, 1847

Pencil and white chalk on brown paper, 20.7 × 16.8 cm

National Portrait Gallery, London

FIG.36 [OPPOSITE]

Detail of William Bell Scott, Old Windsor – Early Morning, 1867–68 [fig.10]