ConTEnTS

13.

16. Scotch whisky

8 SPIRITS DISTILLED

flame applied. If it caught fire, it was strong enough to be ‘proved’. If it exploded, it was stronger and so described as ‘overproof’. Today the strength of spirit is assessed with much greater accuracy and according to three systems.

1. The historic British system measured alcohol levels in terms of ‘proof spirit’. The old British 100° proof was equal to 57.15% ABV so spirits bottled above that level were described as overproof.

2. In Europe, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the hydrometer was used to measure alcohol content and to determine excise taxes based on the Archimedes principle of displacement. This system expresses alcohol as a percentage of pure spirit. A bottle with 40% on the label contains 40% pure alcohol by volume, measured at 20°C. The Organisation Internationale de Métrologie Légale, or OIML requires all alcoholic drinks sold in the EU to state their alcohol content in this way and since 1 January 1980 the British have conformed to this system, referred to as the Gay-Lussac System or OIML.

3. The American system is different to that used in Europe. Proof spirit is equivalent to the number 100 and pure alcohol, 200. So halving the proof stated on American labels will give the strength in terms of percentage alcohol, the OIML system.

Why is the usual bottle strength 40%?

In 1893, Dmitri Mendeleev, a Russian chemist and inventor was appointed director of the Bureau of Weights and Measures and was directed to formulate new state standards for the production of vodka. He determined that the ideal alcohol content was 38% ABV. As a result of his work, in 1894, new standards for vodka were introduced into Russian law. All vodka had to be sold at 40% by weight, rather than by volume, because, this was then a more reliable system of measurement. At the time, distilled spirits were taxed according to their alcoholic strength and, to simplify the taxation calculations, his 38% was rounded up to 40%.

Dmitri Mendeleev

Today, most spirits are bottled at somewhere between 40% and 45% ABV, as much for reasons of taste as tax. A minimum of 37.5% ABV has been introduced, usually for white spirits but, on occasion, for dark spirits too. Some national spirits are bottled at lower strengths. When alcoholic strength drops below 40% ABV many of the more volatile esters that add character to the finished spirit can be lost. Above 50% ABV the alcohol can begin to overwhelm some of the other tastes and aromas.

Excepting lower strengths that may be permitted for some local or national spirits, any alcoholic product below 37.5% cannot be called ‘spirit’ without adding words such as ‘diluted’.

ThE STILLS

Distillation is the process of concentrating the alcohols already present in a wash. Rectification is the process of removing undesirable components from a distillate. Both these processes can be made to work, to a greater or lesser efficiency, in two different types of still: a

16 SPIRITS DISTILLED

Wood toasting and charring

Wood toasting and charring

Wood comprises the cellulose that holds the wood together, sugars that caramelize when wood is toasted, lignin, from the vanillin family of compounds, and tannin. There are over 250 species of oak, belonging to the genus Quercus, and oak is the dominant wood used in the production of barrels. Most will use American white oak, Quercus alba, or European oak of which there are two distinct species: Quercus robur, the English oak; and Quercus sessilis, the oak found in most French forests.

Toasting the wood staves used in barrel making enables them to be bent, caramelizes the wood sugars, and helps the transfer of colour. This process also activates the vanillin held in the wood and

releases tertiary flavours like coconut and spices.

Charring the wood is a more intense process than toasting and draws more of the sap containing flavours and colour towards the surface, so it lies just below the char. This increases the potential for transfer into the distillate. American oak tends to be charred or heavily burnt while European oak tends to be lightly toasted.

Quercus alba American white oak is grown across North America. Demand has increased in recent years, because bourbon whiskey must always be aged in new wood and because American oak costs less than French oak. It is now the oak most widely used to mature Scotch whisky, rum, tequila and bourbon. Growing tall and straight, Quercus alba is high in vanillin, oak lactones and wood sugars but is relatively low in tannins, which represent scarcely 1% of its mass. Therefore, spirits aged in Quercus alba tend to be lighter in colour and carry sweet notes of vanilla drawn from the vanillin, coconut from the lactones and various spice-like characteristics.

Quercus robur A more porous wood, Quercus robur, is native to most of Europe but France is a significant producer of quality and quantity. It imparts lower levels of vanillin but higher levels of tannin, which can represent almost 10% of its mass. This oak leaches a darker, reddish, mahogany colour along with taste characteristics of cloves and dried fruit.

Maturation in wood performs numerous vital functions. It allows a spirit to breathe through the pores in the wood, in a process called ‘oxidation’, mellowing the raw spirit and making a significant contribution towards a spirit’s final character, quality and texture. The movement of the distillate in and out of the wood causes sugars, flavours, aromas and colours to be absorbed which contributes considerable complexity to the finished spirit. Even if filtration is used later to remove any actual character or colour absorbed from the wood itself, the spirit will still have mellowed during its time in wood. Maturation also promotes esterification, when alcohol oxidizes into aldehydes and then into acids which, in turn, react again with the alcohols themselves.

During maturation more or less is absorbed from the wood, depending on the number of years in the barrel, whether the barrels

9. In pot-still distillation the low alcohol wash is entered into what type of still?

A. Wash still

B. Coffey still

C. Spirit still

D. Patent still

10. What type of still is ideal for gin distillers wanting to capture delicate flavours and aromatics?

A. Pot still

B. Reflux still

C. Carter Head still

D. Spirit still

11. What is the purpose of toasting barrel staves?

A. Enables them to be bent

B. Caramelizes the wood sugars

C. Helps to transfer colour

D. All of these

12. Quercus alba is also known as what?

A. European oak

B. American white oak

C. Monlezun oak

D. English oak

13. The process of pumping spirits over flavourings to extract their character is called what?

A Infusion

B. Maceration

C. Percolation

D. Distillation

ThE PRInCIPLES of DISTILLaTIon

14. Who were the most experienced distillers in sixteenth and seventeenth century Europe?

A. Dutch

B. French

C. Italian

D. Spanish

15. Which of these phrases best describes the process of distillation?

A. The creation of alcohol

B. The rectification of alcohol

C. The concentration of alcohol

D. The measuring of alcohol

16. Which of these raw materials do not require conversion before fermentation?

A. Corn

B. Plums

C. Potatoes

D. Wheat

17. Storage in wood can do what to a spirit?

A. Mellow

B. Add colour

C. Add complexity

D. All of these

18. A hot and dry climate will typically do what to a spirit during maturation in wood?

A. Increase the overall percentage of alcohol

B. Reduce the annual level of evaporation

C. Increase the overall percentage of water

D. Reduce the extracts absorbed from the wood

12. Which of these raw materials would typically generate hints of aniseed in a vodka?

A. Corn

B. Potatoes

C. Rye

D. Wheat

13. To be classified as rectified and neutral, a spirit must exceed what level of alcohol?

A. 92% ABV

B. 94% ABV

C. 96% ABV

D. 98% ABV

14. By what century did vodka production become a commercial practice in Poland?

A. Fifteenth

B. Sixteenth

C. Seventeenth

D. Eighteenth

15. In which country, in microclimates on the banks of the river Vistula, are potatoes cultivated for vodka production?

A. Poland

B. Russia

C. Finland

D. Bulgaria

16. Today, which of the early centres of distillation in Poland remains a major town for wodka production?

A. Gdansk

B. Poznan

C. Krakow

D. Nowy Sacz

17. Which Russian ruler visited the Netherlands to learn more about distillation?

A. Ivan the Terrible

B. Catherine the Great C. Peter the Great D. Nicholas II

18. Which of these raw materials is generally the most costly to use in vodka production?

A. Corn

B. Rye

C. Wheat

D. Potato

Answers

1. D; 2. D; 3. B; 4. D; 5. A; 6. C; 7. B; 8. A; 9. B; 10. C; 11. C; 12. D; 13.

C; 14. B; 15. A; 16. B; 17. C; 18. D

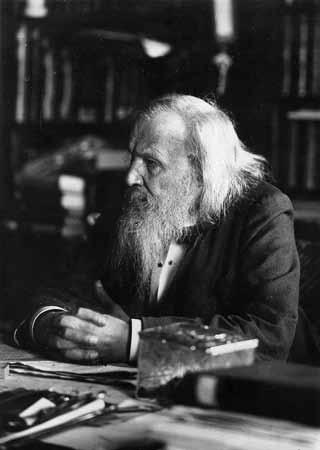

‘Gin Lane’ by Hogarth

Called upon to be patriotic and drink for England, the masses responded enthusiastically. The popularity of gin, the English corruption of the word genever, grew as an escape from disease and degradation. But unfortunately, for all too many, an early death was the only real escape. One sign outside a Southwark inn famously read: ‘Drunk for a 1d. Dead drunk for 2d. Clean straw for nothing.’ By 1750, gin had become the choice of the masses and a source of widespread drunkenness and death because of the lethal ingredients in many of the concoctions. Hogarth sketched vivid records of the

drunkenness and misery. At this time the most popular gin was sweetened, heavily flavoured with juniper and called ‘Old Tom’.

Only the arrival of the continuous still in the 1830s permitted many of the harmful impurities to be removed along with the sugar and glycerine. More subtle and exotic flavourings were used to enhance rather than to mask the raw spirit. Gin’s reputation improved with the emergence of a drier ‘London’ style of gin.

gIn anD ThE RoyaL naVy

Initially, flavourings were introduced into this cleaner and drier spirit as much for their medicinal value as for their taste. The Royal Navy was quick to recognize gin’s potential benefits as protection against disease when sailing the tropics. But still, gin remained relatively unpalatable, at least until the Royal Navy discovered the benefits of lemons. This unfamiliar exotic fruit, originally from the east, not only helped to prevent scurvy but, better still, it improved the taste of gin. For similar reasons, in the nineteenth century, the Royal Navy also adopted Pink Gin.

A German doctor, in the town of Angostura in Venezuela, had perfected a blend of bitters containing bark from the Angostura tree. Sailors added drops of this Angostura to their gin to enjoy the bitters’ medicinal benefit as a cure for stomach ailments. But, again, they found that the addition helped to improve the gin’s taste.

Quinine was another essential part of the sailors’ fight for health. It tasted awful but was key in their battle against malaria. Born in 1740, Jacob Schweppe was an amateur scientist who perfected the process of making mineral soda water. He moved his business from Switzerland to Covent Garden in London, where he met with great success, retiring in 1798. By the second half of the nineteenth century, subsequent owners of the Schweppes company developed and patented a soda water with added quinine which they commercialized as Indian Tonic Water and shipped to the grateful Services. Gin and tonic with a slice of lemon became the beverage of choice throughout the colonies in the East. Returning home, servicemen continued to enjoy their Pink Gins

116 SPIRITS DISTILLED

moLaSSES

Fresh sugar cane is rich in sucrose and so there is no starch needing conversion into fermentable sugars. The cane need only be chopped and crushed by rollers and grinders to extract the cane juice and if this cane juice is fermented and the resulting ‘grappe’ or cane wine is distilled, the rum is called ‘cane spirit’ or rhum agricole on Frenchspeaking islands.

To produce molasses-based rum or what is called rhum industriel on French-speaking islands, this juice must be concentrated through boiling, a process which crystallizes some of the sugars for extraction by centrifugal spinning.

Blackstrap molasses

As the process is repeated, more sugars are removed, leaving behind an increasingly dark, thick, black, treacle-like substance called blackstrap molasses. Molasses still consist mostly of sugar but, unlike refined sugars, they also contain large quantities of vitamins and minerals. Historically, rum producers used the molasses remaining after only two or three spins when still full of aromatic and flavoursome minerals and sugars. When demand for sugar increased, however, more spins were required and so less of these flavourful compounds remained in the molasses destined for rum production.

fERmEnTaTIon

Molasses must be diluted to facilitate fermentation. Then, cultured or natural yeasts are added into the wash to convert the remaining sugars into alcohols. This stage is critical to the character of the finished rum. Depending on temperature, the nature of the yeast and the style of rum required, the process may be short, taking just a few hours or long, taking a number of days: the slower the process, the heavier the style of rum that emerges.

DunDER

When the fermented mash is placed in the still, it contains practically all of the yeast cells, some living and some dead. After the alcohol has been removed by distillation these extracts remain, containing lots of concentrated minerals and other materials. These are collected and stored in a pit or tank under the hot Caribbean sun where the acids are concentrated and the pH level is reduced. Called dunder, these extracts are returned into a later fermentation as nourishment for the new yeast cells, to stimulate their growth and to help them to produce a larger yield. This action also slows down the rate of fermentation, contributing to the creation of a heavier and more pungent quality that is typical of some Jamaican rums.

DISTILLaTIon

Distillation can be in pot and/or continuous stills but, for rum, the spirit must exit the still below 96% ABV. Above that it will be classified as ethyl alcohol or ethanol and not as rum. Usually a pot-still spirit will require two distillations, the first to around 70% ABV to define a rum’s broad character and the second to refine the distillate but only to levels of alcohol which are low enough to retain much of the sugar cane’s character. Typically, pot-still rums will be complex, heavy, pungent, aromatic and oily, usually requiring maturation to mellow before bottling. But much will depend upon the size and shape of the pot.

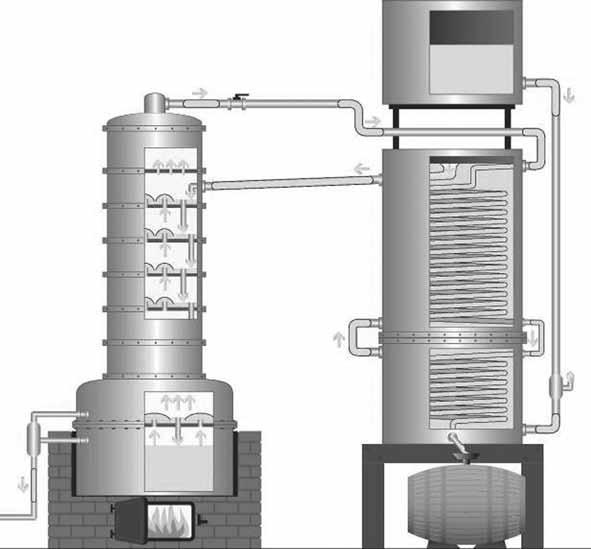

Mobile alambic armagnacais

The lower the ABV percentage off the still, the greater the level of congeners in the spirit and so the greater the need for maturation in wood. At 52% ABV, the distillate contains twice as many congeners as at 60% ABV. A typical spirit drawn from the armagnacais still contains a little more than 50% pure alcohol and just under 50% water. The difference, around 4%, consists of the flavour-giving compounds of esters, acids and congeners. This 4% compares with nearer 2.5% in cognac, 1.5% in whisky and less than 1% in vodka and can be a reason for armagnac being raw and unpalatable without many years of maturation in wood.

This process is costly and full of risk. So, today, few grape growers in the area rely on armagnac alone. Instead, many of the generally small and family-run farms rely more on cattle or other animals or cereals or they produce wine. However, in time, these same compounds oxidize and transform into the aromatic complexity and rich, palate-coating texture so typical of traditional armagnac. What distinguishes armagnac from other brandies is that the wine, drawn from the tank on top of the condensing column, heats as it drops through the perforated plates towards the boiler, turns into steam and evaporates. The vapours rise back up through tubes

in the plates where they are forced into contact with the incoming wine. The vapours become saturated and highly charged with the wine’s fragrance and fruit. They continue to rise before exiting the top of the still, passing over into the adjacent column and flowing through the cold condensing coil to drop as liquid into a barrel. The alambic armagnacais is not able to reach high temperatures so the low alcohol distillate retains many of the esters, acids and congeners that double distillation in a pot still eliminates. Heads are retained for their aromatic qualities unless the wine quality is not good. Tails are less palatable and so they remain, circulating in the system until removed by the distiller. In a pot still the heads and tails exit the still for recycling.

The pot still was banned from 1943 to 1971 when only the single continuous still was authorized. But the pot was authorized again in

Armagnac condenser

11

Eaux-DE-VIE

baCkgR ounD

Eaux-de-vie is the term used for brandies destined to become cognac or armagnac, but it is also the name of the dry, true fruit distillates made from fruits other than grapes, usually bottled at higher strength than liqueurs, between 40% and 45% ABV, and sometimes aged. These are generally classified according to whether made from soft or stone fruit. All eaux-de-vie are unsweetened, clean and fresh in character which means that the fruit used must always be ripe and untainted, which is costly as it takes around 100 kilos of fruit to make five to ten litres of fruit spirit.

The Alpine triangle in Europe is a major area for production of eaux-de-vie. This includes the Black Forest in southern Germany, the Alsace region, the Swiss valleys, Austria and north-east Italy across to the Balkans.

Fermentation is usually as long as nature requires to capture as much flavour as possible. Distillation can be executed in pots to relatively low levels of alcohol to preserve the character of the fruit or in continuous stills to higher levels of alcohol in order to highlight the more fragrant aromatics and to eliminate methanol, levels of which can be significant in some fruits.

Most are bottled immediately to preserve character, resting only if settling is necessary, in glass or stainless steel. They are usually colourless. Generally, only those distilled from stone fruits are aged, for example, slivovitz from the Balkans is made from plums and

ground kernels that are crushed and pressed before fermentation and then distilled and matured in wood to refine the overall quality.

The division between soft and stone fruit reflects the fact that soft fruits, including pear, are low in sugar. They must first be chopped and macerated in neutral spirit to produce sufficient alcohol for distillation. One example is a raspberry flavoured spirit called himbeergeist, which cannot be produced by fermenting raspberries because their low sugar content yields too little alcohol. Instead, neutral alcohol is infused with the raspberries. The mixture is diluted and redistilled. Some may choose not to macerate in this way but to ferment the soft fruit; the results can be excellent but the yield will be very low.

Stone fruits, like cherries, will not need prior maceration as they contain enough sugar to ferment into fruit wine ready for distillation. Some distillers may choose to crack and crush kernels with the fruits to add a pleasant bitterness to the distillate.

aPPLE bRanDy

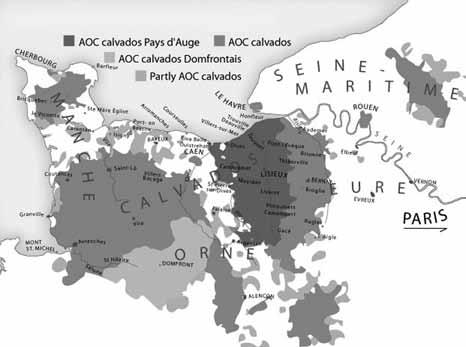

Map of the appellations of calvados

The French apple brandy called calvados, is named after the Normandy region of Calvados and dates back to the sixteenth century. Today, it is