First published in Thailand in 2025 by River Books Press Co., Ltd

396/1 Maharaj Road, Phraborommaharajawang, Bangkok 10200 Thailand

Tel: (66) 2 225-0139, 2 225-9574

Email: order@riverbooksbk.com www.riverbooksbk.com

@riverbooks riverbooksbk Riverbooksbk

Copyright collective work © River Books 2025

Copyright texts © the contributing authors 2025

Copyright photographs © River Books except where indicated otherwise 2025

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electrical or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage or retrieval system without the written permission of the publisher.

Publisher: River Books Press Ltd., Bangkok, Thailand

EU Authorised Representative: Easy Access System Europe Oü, 16879218 - Mustamäe tee 50, 10621 Tallinn, Estonia, gpsr.requests@easproject.com

Editor: Peter D. Sharrock

Text editor: Narisa Chakrabongse

Design: Ruetairat Nanta

ISBN 978 616 451 106 4

Previous page: Dragon head architectural antefix: Terracotta, Hà Nội, Trần Dynasty, 14th century CE H: 62 cm, W: 43.5 cm, BTLS.23210

Cover & Back cover: Emperor’s robe with dragon: Silk brocade,Yellow silk, mid-19th century L: 133 cm, W: 250 cm, BTLS.4381

Printed and bound in Thailand by Sirivatana Interprint Public Co., Ltd

13.

16. Cam ritual objects: Anne-Valéry

17. The South and Nagara Campā: John Whitmore

18. Esoteric Buddhist goddesses of the Campā Vijaya state:

Trần Kỳ Phương & Nguyễn Thị Tú Anh

Opposite page: Avalokiteśvara with child. Gilded and lacquered wood, 19th century.

H: 86 cm, W: 53 cm, D: 41 cm, BTLS.9770

management programme, building canals linking rivers and developing the Delta into a rice bowl. Over time the Nguyễn prospered and the Trịnh declined, and a Nguyễn Dynasty ruled over the whole country under powerful Emperors Gia Long and Minh Mang from 1818-24. The Delta became a major rice producer, which Liên says fed the south, the centre and some of the North Vietnam and still had a surplus for export. South Vietnam was ceded to France in 1867 and renamed Cochinchina, when more canals and a large road system were constructed.

The art of the Nguyễn Dynasty included the construction of the enormous and graceful citadel of Huế, modelled on the Forbidden City in Beijing, and adorned with large dynastic bronze urns carved with landscapes of the empire and defended by giant ceremonial cannons. The yellow silk imperial robe that graces our cover has the emperor represented as a dragon surrounded by clouds and ‘flanking the sun’, all of this rendered in fine, elaborate and continuously variegated silk embroidery. Hoàng Anh Tuấn (Chapter 12) says that as well as symbolising royal power, the aerial dragon also expresses the desire for a favourable environment for agriculture, farmers and artisans. Celebrated ‘bleu de Huế’ porcelains with dragon motifs in bright blue cobalt were manufactured at scale under close supervision by Vietnamese masters at the Jingdezhen imperial kilns in China. Masterpieces in wood include sacred cabinets, inlaid with motherof-pearl and bone, and icons of Buddhas and the female Bodhisattva Quan Am holding a child, some of which achieved special renown for the dramatic roles they played in historical conflicts.

This volume is an output of a collaborative Summer Programme of the SOAS University of London with the History Museum-Hồ Chí Minh City (HCMC), organized to create a new catalogue of the Museum’s growing collection of artifacts recovered from Vietnam’s extensive archaeological programmes. The catalogue From the Red River to the Mekong Delta: Masterpieces of the History Museum-Hồ Chí Minh City is published by River Books, Bangkok, and launched at Hồ Chí Minh City University this year, with a Vietnamese language version to follow shortly thereafter.

The SOAS Southeast Asian Art Academic Programme is generously funded by the Alphawood Foundation in Chicago to bring students from Southeast Asian universities for postgraduate study in London and to annual research Summer Programmes in the Region.

Materials and Object Types

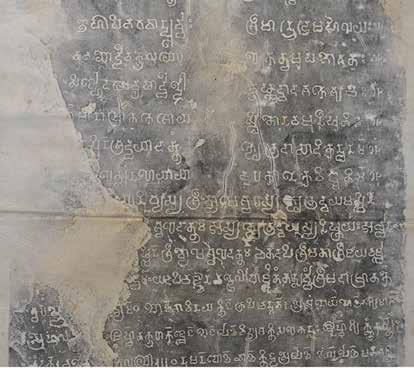

Three exceptional items are a text engraved on gold leaf (K. 1330, 7th-8th century, Long An), a gold coin (K. 1322, 7th century, Ta Keo) and a gold plate (K. 1451, 8th century, Lâm Đồng), but the overwhelming majority of the early inscriptions of the Mekong Delta are engraved on stone artifacts, about 80% of them fashioned from sandstone and about 20% from schist. A brief survey of the whole Khmer epigraphic corpus shows that inscriptions in sandstone far outnumber those in schist, presumably because the former material was not only easier to carve but also more widely available.22 Almost all the inscriptions that are engraved on schist originate from the delta, suggesting that quarries of schist existed in the region.

001817. National Museum of Cambodia, Phnom Penh ( ក 3131).

4

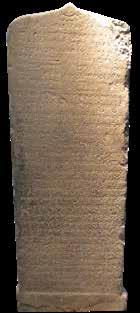

Regardless of the type of stone, the majority of the texts are inscribed on doorjambs, the architectural element of Cambodian temples typically chosen as support for inscription. Some of the stones originally carved as doorjambs have subsequently been reused as lintels in ancient temples (e.g. K. 40, 5th-6th century?, Ta Keo) or as thresholds in modern houses (e.g. K. 875, 5th century, Ta Keo; see fig. 1).23 A fragment of an inscription that may date to the same period (K. 1270, 5th-6th century, Ta Keo), whose original use can no longer be discerned, was reused as a conduit for libations (a so-called somasūtra) in a brick temple that was erected not more than one or two centuries later

from Phú Hựu, Đồng Tháp province, inscription K. 9. Museum of Vietnamese History, Hồ Chí Minh City (BTLS 5548). Fig. 5 The middle segment of EFEO estampage n. 250 for inscription K. 493.

(figs. 6 and 7). The other common object type is the freestanding stela, several of them carved not only with text but also with decorations (see above). Rarer object types include pedestals (e.g. K. 755, 7th century, Ta Keo and K. 884, 7th century, Trà Vinh), slabs of stone (K. 1216, 6th-7th century, Ta Keo and K. 956, 7th-8th century, Prey Veng), a Buddha statue (e.g. K. 820, 7th century, Kompong Speu), a grinding stone (K. 1215, 6th-7th century, Ta Keo) and a baked clay tablet (K. 1355, 7th-8th century, Ta Keo).

Contents

As mentioned above, the Sanskrit inscriptions (as well as those formulated in Prakrit and Pali), with only one partial exception (K. 493), are in verse and the Khmer ones in prose. The inscriptions are relatively short: the Sanskrit texts have an average of five stanzas and the Khmer ones do not on average extend over more than ten lines. The entirely Sanskrit inscription K. 483 with its 29 stanzas and the double-language inscription K. 1247 containing 45 lines in its Khmer text are the longest texts in this corpus. Generally, the Sanskrit inscriptions open with an invocation to one or more gods, give a eulogy and genealogy of kings or other members of the social elites, and declare a work of merit (installing a divine image, etc.), whereas the Khmer texts give details of religious endowments (donations of land, servants, etc.) as already mentioned (see p. 57).24 Often, at the end of the inscriptions, a formula of malediction and benediction is found. One of the earliest examples of a praise of a king is found in the Sanskrit inscription of Prasat Pram Lveng (K. 5, see above p. 104). In addition to the purity of lineage, King Guṇavarman was eulogized for his intelligence and valor. At the end of the inscription, the warning that misuse of the foundation shall be punishable in hell (stanza XI) opposed to the promise that proper use shall be rewarded by attaining the supreme abode of Viṣṇu and felicity (stanza XII) are the first formulae of malediction and benediction recorded to date:

dattaṁ ya[d] guṇavarmmaṇā bhagavate dharmmārtthinā śaktito viprair bhāgavatair anātha-kr̥paṇais tat-karmma-kārais tathā tat sarvvair upayujyatāṁ samayato yair anyathā bhujyate yujyantāṁ narake yamasya patitās te pañcabhiḫ pātakaiḥ // XI // Abhivarddhayatīha yo mahātmā bhagavad-dravyam idaṁ guṇāhva[yas](ya)25 sa tu yat-ku[śa]laṁ labheta viṣṇoḫ paramaṁ prāpya padaṁ mahad yaśaś ca // XII //

‘Whatever is given to the Lord ( bhagavant , i.e. Viṣṇu) by [King] Guṇavarman, with Dharma in view, in conformance with [his] capacity, is to be enjoyed in accordance with the rules by the Bhāgavata Brahmins (or the Bhāgavatas and the Brahmins), those who are poor and without protection as well as those who officiate there. Those who

Fig. 6 Inscription (K. 1270) on a fragment of a schist artifact at Prasat Preah Ko, Ta Keo province. Photograph Dominque Soutif.

Fig.1 Chinese, Wei dynasty standing Buddha, bronze, from Vọng Thê, Thoại Sơn, An Giang province, 6th century, An Giang provincial Museum.

pl.I and fig. 1.1). But probably even more interesting is the bronze image of the Chinese Buddha found in Óc Eo (notice 58, see Malleret 1960a: 202-8 and Malleret 1960b: pl. LXXXV) in which Malleret saw a work dating from the Northern Wei period 北魏 (386-534 CE) but which we agree today to relate to the art of Northern Qi 北齊 (550-77). It was in 1979 that Vietnamese archaeologists also found a second piece of Chinese origin, this time indeed a Northern Wei Buddha, now kept in the An Giang Provincial Museum (Lê Xuân Diệm 1995: 284) (Fig. 1).

The earliest evidence of the adoption of Buddhism in the region and perhaps even throughout the Indochinese peninsula to have been produced locally, is in our opinion, the impressive pillar unearthed in 1994 at the Mount Gò Ông Địa (Mount of the god of the Soil) in the village of Lạc Quới, Tri Tôn district, An Giang province (Fig. 2). This small hillock is one of the few elevations that continue to Phnom Ba Thê, the Phnom Bayang massif in Cambodia, the last buttress of the Damrei mountains. Now lying in the entrance courtyard of the An Giang Provincial Museum, this granite basrelief of very rough appearance but of undeniable power, was studied by Ms. Nguyễn Thị Tú Anh who has shown how its iconography is part of a tradition at the transition between aniconism and the first representations of the Buddha, as they appear in India in the art of Amarāvatī in the 2nd century of our era, and which possibly dating from the 3rd-4th centuries. The particular proportions of the figures and the rustic appearance of the highly expressive sculpture are reminiscent of early Śrīkṣetra Pyu art (see Gutman & Hudson 2012). The large pipal leaf evokes the Bodhi tree (Bodhivṛkṣa), under which the Buddha attained Awakening. The pillar surmounted by the Wheel of the Law (Dharmacakrastambha) recalls the Buddha’s first sermon in the deer park of Sārnath and, if we are to believe the interpretation proposed by Ms. Nguyễn Thị Tú Anh, the lower register represents the teaching of the Doctrine to his mother, which the Buddha made in the Heaven of the Thirty-three Gods (Trāyastriṃśa).

To tell the truth, this pillar, the use of which has yet to be determined (an element of a portal/toraṇa, balustrade/vedikā, column bordering an entrance door or a pillar supporting a wheel of the Law...), is the only architectural fragment that can truly be linked to a Buddhist monument that once stood in the region. All the other remains – wood and stone statuary –are, at best, associated with brick foundations whose superstructures have been levelled and which archaeologists hesitate to identify as ‘tombs’, ‘temples’, or ‘stūpas’, to which are sometimes added wooden pillars whose initial use is not always clear. Like Anna Aleksandra Ślączka (Ślączka 2011), we would, however, like to propose the hypothesis that small fragments of gold sheet are elements of the foundation deposits of Buddhist and Hindu structures. These were unearthed in 1982-3 in Nền Chùa (Hòn Đất district, Kiên Giang province), in 1982, 1993 and 1996 in Gò Tháp (Tân Kiều village,

Tháp Mười district, Đồng Tháp province), in 1985 in Đá Nổi (Thạch Đông village, Tân Hịêp district, Kiên Giang province) and especially in Gò Xoài (Long An province) of which we spoke above. The Buddhist character of the architectural remains of Nền Chùa and Gò Xoài is evident. We can in particular interpret the brick structures with a square plan, unearthed at lower levels in the central part of the remains, which are sometimes described as ‘tombs’ by archaeologists, as chambers for foundation deposits and/or for relics (Lê Thị Liên 2005). Among many examples, we can compare them with the structures unearthed on the site of Nāgārjunakoṇḍa stupa (Andhra Pradesh, India), dating from the 3rd to 4th centuries and that of the 6th century Khin Ba in Śrīkṣetra, central Myanmar (Guy 2014: 78-81, cat. 26-27).

In Malleret’s time, one could still see some architectural remains. In Trung Ðiền, for example, the little Buddha comes from a place where Malleret could still make the following observations: ‘The sanctuary [a small Christian church] is established on a mound strewn with large bricks which seems to correspond to the site of an old Khmer building’. So it is for the Buddha of Hiếu Tử we shall study later: ‘A piece of slab which seems to correspond to half of an ablution tank which remained in the state of a rough outline was lying in the enclosure of the pagoda and would come from a mound located to the east of the enclosure where the sanctuary stands’. Today, the extensive scale of rice cultivation in the Delta no longer allows such observations.

But despite this gradual erasure, the Buddhist statuary unearthed in the Delta since the beginning of the 20th century confirms our point convincingly. The variety of sites in which Buddhist images have been found testifies to the wide spread of Buddhism throughout the Delta, a spread which also appears to have been more abundant than further north, along the coasts of Vietnam, or more upstream along the Mekong in present-day Cambodia. Be that as it may, it is certain that these images of Buddhas and Bodhisattvas in stone and wood are found along the coasts of the Delta, from the bay of Rạch Giá to Cape Vũng Tàu as well as along the banks of the Mekong and its outlets, the Sông Hậu, the Vietnamese continuation of the Bassac and the Cổ Chiên, Hàm Luông and Mỹ Tho rivers. Whether it spread from India or China, or from both of these inputs, Buddhism arrived by water. Some parts of the Delta seem to have been particularly active, such as the present province of Trà Vinh – the ancient Preah Trapeang of the Khmers – where many Buddhist pagodas are still concentrated today and where the modern districts of Trà Cú and Cầu Ngang have delivered the most numerous statuary testimonies.

The stylistic approaches of Pierre Dupont (1955: 189), Louis Malleret (Malleret 1963: 173-87), Jean Boisselier (1966: 262) and Lê Thị Liên (in Guy 2014: 118-9), based on the iconography, the costume, the position of the Buddha or the place of discovery, demonstrate above all a wide variety of production in a chronological framework that is nevertheless relatively limited (the 6th and 7th centuries, essentially). To those we can add a more global

Fig. 2 Gò Ông Địa Buddhist Pillar, Lạc Quới village, Tri Tôn district, An Giang province (H. 238 x 30 x 34 cm), granite, c.4th century (?), An Giang Museum: BTAG. 2773/D

Figs. 11 a, b Types of geometric 12-sided (dodecahedron) gold beads on display at Museum of Vietnamese History Museum

Hồ Chí Minh City. (Photo courtesy of Museum of Vietnamese History Museum

Hồ Chí Minh City)

Fig. 10 Earrings from Óc Eo BTLS.2166, and Pangkung Paruk, Bali. (A screenshot from Calo et al. 2020: 120)

gold beads have been found at Óc Eo sites and many other sites in Maritime Asia [Figs. 11a, b]. This structure was first studied by Greek Pythagoreans in the 5th century BCE. Malleret saw them as local products in emulation of Roman samples (Malleret 1962, III: 73-74, pl. XIV; Demandt 2015: 313-14). Polyhedral beads have been recorded in many sites in Hòa Diêm in central Vietnam; Śrīkestra and Beinnaka in Myanmar; Air Sugihan in Sumatra; Batujaya in Java; Khao Sam Kaeo, Phu Khao Thong and Tha Chana in Peninsular Thailand, where they have been dated to the late 1st millennium BCE (Pryce et al. 2006: 310-11, fig. 17; Bennett 2009; Manguin and Indradjaya 2011; Nguyễn Kim Dung 2017: 326-27; Calo et al. 2020: ibid.).

Michèle Demandt (2015: 321) notes that: ‘Many gold ornaments from the early historical period have been found at sites that participated in longdistance trade and produced their own set of prestige goods such as beads. Examples of this are Óc Eo in Vietnam; U-Thong, Phu Khao Thong, Khao Sam Kaeo, and Khlong Thom in Thailand; possibly Hebu in China’.

The Óc Eo goldsmiths successfully adopted techniques from abroad as can be seen in bivalve casting moulds (BTLS.1896), droplets of gold, workshop tools and unfinished foils and gold objects found at the Óc Eo site (Malleret 1948: 275, pl. I; Malleret 1961, II: 349; Bennett 2009: 103; Demandt 2015). Paul Pelliot (1903: 254, 261) noted that the 6th century Chinese Southern Qishu and 7th century Jinshu (see ‘Funan’ and ‘Zhenla’ in Chinese annals’ in this volume) record Óc Eo habitants as paying taxes in gold, silver, pearls and perfumes. However, the Óc Eo gold was not necessarily of local origin and the jewelry may have been melted multiple times and recast as Calo et al. have suggested (2020: 14): ‘Geological sources for gold are difficult to identify due to possible multiple melting and recasting events and to gaps in our geological knowledge. Our comparative compositional study of gold excavated across Southeast Asia, however, is providing critical data to support or disprove stylistic and technological analyses concerning the origins of imported gold’.

From his work at the Bit Maes and Prohear sites in southern Cambodia,

Andreas Reinecke (2009: 114-56) expressed doubt that the gold resources of the Mekong Delta were sufficient to produce jewelry on the scale found at the Óc Eo cultural sites. Anna Bennett (2009: 100) examined damaged gold items and thought that all had been recycled by goldsmiths to satisfy domestic consumption. Reinecke also suggests that settlements were preferred by product craftsmen rather than proximity to raw material sources.

ʻGold working need not take place near gold mining, but rather near potential consumers, who can order and pay in exchange for the products.

Craftsmen could travel large distances on routes that are not necessarily identical to the gold and silver trade routes. They could also settle with their workshops in trade centers like those at Angkor Borei or Óc Eo in later times. (2015: 158)ʼ

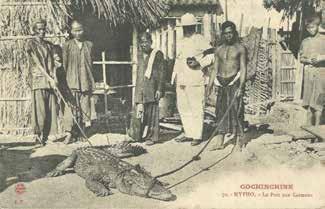

It may also explain why goldsmiths appear to have moved freely from market to market (Tjoa-Bonatz and Lockhoff 2019: 50). Reinecke suggests that local products could have been exchanged to import gold for jewelry. Forest products such as elephant tusks, rhinoceros horns, rosewood, kingfisher feathers, cardamom, gamboge saffron gum resin, lac and chaulmoogra tree oil were exchanged for Chinese gold or silver (Reinecke et al. 2009: 114-56). Caiman crocodiles were also traded and were still photographed in the Delta during the French colonial period in the early 20th century [Fig. 12]. Honey and beeswax were also traded. Malleret noted that the Khmer term Kramwn Sa (‘white-wax market’), used by Chinese residents in Hà Tiên of Kiên Giang province under the 17th-century Mạc dynasty, could derive from the name of an ancient location in Rạch-giá close to Óc Eo (Malleret 1959, I: 20-21). Honey and wax producers were, for example, exempted from other obligations to the court in an 11th-century inscription K. 913 (Cœdès 1937-1966, V: 270) found by Malleret in Tham-mo in the Plain of Reeds. Further study is needed to compare the gold products in the Óc Eo culture with those dated to the 8th-10th century unearthed at the Cát Tiên archaeological sites in Lâm Đồng province, some 150 km northeast of Hồ Chí Minh City (Lê Xuân Diệm et al. 1995: 144-47). The Cát Tiên religious architectural complex, located at the watershed of the Đồng Nai river, may be identified as a hinterland of the Óc Eo culture.

Fig. 12 Cochinchine Vietnam, ‘Le parc aux Caïmans, dans la province de My-Tho’. Collection de Cartes postales 1928. https://www. delcampe.net/en_GB/ collectables/postcards/ vietnam/vietnam-indochinemytho-le-parc-auxcaimans-928429168.html Accessed on 25/7/2020

Fig. 5 Enamel bronze wares of the reign of King Minh Mạng, (1820-1840).

H: 6.0 cm

BTLS.3047.

Fig. 6 Covered bowl depicting dragons amidst clouds with inscriptions “嗣德年造” (Tự Đức niên tạo) ordered in China. 1848-1883

H: 3.8 cm, D: 26.5 cm

BTLS.9363.

were made in the royal workshops, or ordered from abroad (?). They can be confirmed as items for the royal family based on their decoration, and their inscriptions.

3. Collection of ceramics

The Vietnamese blue-and-white porcelain were found in Huế province, central Vietnam, and are known as ‘bleu de Huế’. It is one of the important groups in the Nguyễn dynasty’s antiquities, currently on display at the HM-HCMC (Fig. 6). These porcelains were ordered by the court from the Jingdezhen kilns (Jiangxi, China) with high quality commercial materials: ceramics made of fine kaolin, white and smooth, and bright enamel and blue cobalt. They are rich in types including all kinds of artifacts: bowls, cups, plates, bowls, vases, standings, so on. The differences include the decorative patterns, inscriptions and the king’s reign written on the artifacts, which may also indicate that they were ‘ordered products’ by the courts. Such products are called by the term ‘Đồ sứ ký kiểu’ or ‘Commissioned Patterned Porcelains’ (Trần Đức Anh Sơn 1997: 154-155).

In terms of chronology, the ‘Đồ sứ ký kiểu’ are mainly in white enamel with blue patterns which dating from the reigns of King Minh Mạng (18021940), Thiệu Trị (1841-1847), Tự Đức (1848-1883), all of which were made in pottery kilns in China.

Later multicolored ceramics began to appear under Khải Định’s reign (1916-1925). The decorative themes include images only for royal items such as the motif of ‘a coiled dragon’, a dragon hidden in clouds, two dragons playing with a pearl, chasing dragons, the three immortals or the three wise men, the Four Seasons, pheasants and chrysanthemums, mandarin duck, lotus, and so on.

Although the dragon image is shown on most of the ceramics ordered in China, there is only one vase, marked Acc. no. BTLS 6448 depicting a dragon that resembles image of the Qing Dynasty with Sino scripts saying ‘Minh Mạng niên chế 明命年製’, known as ‘crafted under the Minh Mạng’s reign’. From the Thiệu Trị period onwards, ceramics are depicted with dragon images in the style of the Nguyễn dynasty, with the following characteristics: dragon with thin mane, horn with a small barb, sparse dorsal fin, or a spiral tail (Cadière and Gres 1919: 86).

For further information, only one group of pottery was made in Bát Tràng, in north of Vietnam, marked with Gia Long’s reign, dating to the early 19th century; this group is currently on display at the Hanoi National History Museum. It can be considered the only ceramic collection made in a Vietnamese kiln during the Nguyễn dynasty (?) (Nguyễn Đình Chiến 1995: 211).

Collection of wooden furniture

This collection showcases the style and skills of the carpenters in Huế, and represents a significant number of objects from the Nguyễn dynasty. Typical objects are religious statues, worship cabinets, decorative wooden furniture, utensils, and so on.

Compared to wood products manufactured abroad, Vietnamese wooden furniture has outstanding details such as: using intaglio and cameo woodcarving techniques combined with mother-of-pearl or bone, in which the most prominent is carved latticework (Trần Lâm Biền 1979: 47; Đặng Văn Thắng and Hoàng Anh Tuấn 1992: 71).

The latticework, which is also called ‘Roman lattice’, was a popular technique in decorative wood carving in Huế under the Nguyễn dynasty. Latticework may be functional or purely decorative, or some combination of the two, as can be seen in the wooden interiors on display at the HMHCMC. Examples include a wooden cabinet (Acc.no. BTLS 33451), an altar/ shrine wooden cabinet (Acc.no. BTLS 13311), and a wooden screen (Acc.no. BTLS 4377).

The use of latticework technique employs regular repetition based on the principle of contrast, while still maintaining a visually delicate rhythm. (Nguyễn Hữu Thông 2019: 157).

The craftsmen in Huế were extremely skilled using the latticework technique in woodworking. It may be the major characteristic that the craftsmen aimed for, in order to create their own style of wood carving art in Đàng Trong region (Central Vietnam) under the Nguyễn dynasty (Nguyễn Hữu Thông 2019: 156).

On the subject of decoration, the craftsmen demonstrated royal themes such as: ‘The Four Sacred Animals’ as can be seen on the screen of Acc.no. BTLS.4377; a stylized dragon of a ‘flower transformed into a dragon’, or stylized floral patterns combined with geometric motifs that can be seen on wooden cabinets, and the altar/shrine cabinet marked at Acc.no. cabinet, Acc.no. BTLS 33451, and Acc.no. BTLS 13311 (Fig. 7).

These decorations are not only typical of Eastern styles, they are also cultural and aesthetic symbols of Confucian thought. Images of trees and fruits such as the peach, pomegranate, Buddha’s hand, melon, so on, reflect the artist’s view of nature in daily life, and they also include symbolic meanings such as animals, or inscriptions (Cadière 1919: 75-79).

Fig. 7 Shrine wooden cabinet carved in the Nguyễn Dynasty, H: 97 cm, W: 85 cm BTLS.13311.

Fig. 3 A bowl from the Gannay collection with Chrysanthemums pattern, Việt Nam, 12th-14th century. BTLS.1411. H: 6.5 cm, D: 17 cm.

Fig. 4 A Vietnamese creamy glazed stoneware, 13th-14th century. A lidded storage jar with incised brown enamel design. BTLS.1464. H: 25.5 cm, D: 20 cm.

Vietnamese celadon is similar to that made in the Yaozhou region (Rastelli 2017: 6-8). The two bowls have five spur marks and the base is unglazed, showing the clay color as white. The bowls have floral decorations or an image a child playing with lotus flowers or peony flowers (Truong 2007: 53), motifs common during the Song dynasty. Iconographically, the decorations may suggest a pun on the Vietnamese word ʻliên tử’, which means successively giving birth to sons, also called lien-tzu/蓮子 in Chinese, related to the concept of male heirs in a traditional Chinese family. However, Vietnamese celadon with a baby figure is more realistically depicted with a body that is neither dressed nor adorned, in various poses such as swimming or sitting in the middle of a lotus, sometimes with a pomegranate flower. Truong (2007: 54) argues that Vietnamese craftsmen created different versions of the decoration as the result of artistic interaction between Vietnam and China around the late 13th century. Similar celadons are produced today in pottery kilns in Hống hamlet, Chí Linh town, Hải Dương province, Việt Nam.

Chrysanthemum bowls from moulds, with rims curved slightly inward, were popular under the Lý and Trần dynasties (Fig. 3). The chrysanthemum motif and spur/stilt marks are all found at the kilns in Tức Mặc, formerly Phủ Thiên Trường in Nam Định province, dating back to the Trần dynasty. Pottery called ‘gốm hoa nâu’ in Vietnamese, is carved on its surface and brown or red enamel is inlaid into the design, before a translucent slip is added. This technique first appeared in the 11th-13th centuries. Similar pottery in Japan and China is called ‘inlaid brown/iron brown’ in the western world (Phạm Quốc Quân 2011: 13). For example, an ivory-glazed storage jar (Fig. 4) is a lidded-jar with a lotus petal design incised into the clay and highlighted with an iron wash underglaze. The jar was gifted to the Museum Blanchard de la Brosse in Saigon from the Museum Louis Finot in Hà Nội, in March 1934.

2. Vietnamese ceramics entering the Vietnam National Museum (Saigon) 1956-1975

Fig. 5 Lime pot from the Olov Jansé collection, its handle treated like an areca palm tree and betel nuts. BTLS.3331. Made of green-glazed stoneware, 15th-16th century.

H: 14.2 cm, D: 12.2 cm.

The Vietnam National Museum in Saigon accepted donations from Olov Robert Thure Jansé in 1960-1962, and from Director Trương Bửu Lâm (see BTLS-HS.53/V). 150 artifacts were returned to the Museum by the Peabody Museum and Harvard-Yenching Institute. The lime pot BTLS.3331 is representative of these (Fig. 5). It is thickly potted with a spherical body on an unglazed flat bottom, with a small circle in the shoulder of the jar for filling and/or extracting lime. The heavy strap handle and shoulder decorations

both evoke the betel nut palm tree. The lime pot is considered to be the one of the most original creations of Vietnamese potters (Nguyễn Xuân Hiên 2006: 507-8).

The shapes of these popular wares varied from the 14th-17th centuries (Truong 2007: 145). Fig. 6 shows the skill of Vietnamese potters in reproducing natural forms (2007: 145, pl.113).

3. Vietnamese ceramics from 1975 to present

Vietnamese collector Vương Hồng Sển donated 849 artifacts to the HMHCMC in 1996, including ‘commissioned patterned porcelains’ or ‘Đồ sứ ký kiểu’ Vietnamese designed porcelains manufactured in China (Fig. 7-8). The orders were made by people who served at court under the Lê-Trịnh dynasties (late 17th-late 18th centuries), under the Nguyễn dynasties (1691-1725), and under the Tây Sơn regime (Trần Đức Anh Sơn 2002: 15, 197). The term ‘Đồ sứ ký kiểu’ was coined by Vương Hồng Sển himself (Vương Hồng Sển 1960).

Such ceramics are classified as Vietnamese wares based on the following criteria: 1. The landscape decorations illustrate a specific location in Việt Nam; 2. It has adapted Chinese characters; 3. The objects bear the reign mark of the current Vietnamese emperor’s title such as Hồng Đức, Gia Long, Minh Mạng, Thiệu Trị, Tự Đức, Khải Định; or, the reign mark coincides with the year when the Vietnamese envoys went to China; 4. Although the ware’s decorations were made by Chinese artists, they are in Vietnamese style, using materials such as copper, fabric, paper… of sculpture, architecture and painting that dated from the Lê-Trịnh dynasty to the Nguyễn dynasty; 5. Porcelain products were exclusively for use by Vietnamese mandarins (Trần Đức Anh Sơn 2002: 198).

Vietnamese ceramics from the Hội An shipwreck

In 2000, the HM-HCMC received 4,362 ceramics excavated in 1997-99 on Chàm Island off Hội An town, Quảng Nam province. According to archeological excavation reports (Phạm Quốc Quân, Tống Trung Tín 2000: 94), the Thai ship was on its way back to Thailand from Vietnam, with Vietnamese pottery as the bulk cargo. These were mid-15th century trade wares, according to Scollard (1981: 93). The ceramics were in good shape and of high quality to meet export demand. Vietnamese and Thai ceramics dominated the ‘Chinese’ ceramic export market after the Ming court forbade the Chinese to export or go overseas in the 15th century. These shipwreck ceramics make up more than 50% of the Vietnamese ceramics in the HMHCMC inventory and include blue and white, celadon, or a design like a lithophone instrument also known as ‘hidden carved porcelain’. They were made in Chu Đậu, Mỹ Xá, Hải Dương province (Phạm Quốc Quân and Tống Trung Tín. 2000: 96).

Fig. 6 A lime pot, Bát Tràng pottery, 15th-17th century. A screenshot from ‘The Elephant and the Lotus –Vietnamese ceramics in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’ (Truong 2007: 145, pl.113).

Fig. 7 Plate depicting a dragon amidst clouds with inscriptions “慶春侍左” (Khánh xuân thị tả), blue and white porcelain, BTLS.15139, the Vương Hồng Sển collection.

Fig. 8 Bowl with inscriptions “明命年製” (Minh Mạng niên chế), blue and white porcelain, BTLS.14892, the Vương Hồng Sển collection.

Fig. 12 A Cây-Mai standing ceramic sculpture of the late 19th century, BTLS.30285. H: 95 cm, W: 25 cm, D: 17 cm.

Fig. 13 A lidded ewer in Shiwan style with incised characters ‘萬 應 藥 酒’ (Vạn ứng dược tửu), BTLS.29181 with prunus branch motifs and figural dragon head spout. 19th or 20th century. H: 50 cm, D: 40 cm.

Lái Thiêu town approximately 30 km far from the Cây-Mai region (Huỳnh and Nguyễn 1994: 40), which explains why Lái Thiêu pottery is considered as the later continuation of this artistic achievement (Trần Bạch Đằng 1991: 346; Nguyễn Thị Tú Anh 2014: 5-6).

The Cây-Mai pottery collection in the HM-HCMC

Aesthetically, Shiwan-style pottery looks everyday and heavy-handed compared with porcelain ware made of fine white clay, like Jingdezhen products (Scollard 1978: 101; Scollard 1981: 2). Shiwan-style ceramic products are rarely collected for display in museums. It differs from many other ceramics from the Qianlong dynasty, c.1790 (Scollard 1981: 110).

The facial and flesh areas of figurines are always left unglazed, with only the garment enameled (Fig. 12). Scollard says it was to make flesh seem warmer (1978: 105).

A lidded, pottery ewer (Fig. 13 BTLS.29181) with two handles, albeit slightly chipped, in Shiwan-style has these four incised characters ‘萬 應 藥 酒’, which suggests its function was as a container of herbal alcohol used for massage to improve circulation.

Péralle notes that Cây-Mai potteries were not moulded but were completely handmade, glazed, and dried by craftsmen (1895: 56-57). The weakness of Cây-Mai pottery was the colour that was used. Péralle (1895: 58) said enameled colour details tended to fade, peel or flake off after long use. Scollard (1981: 2) believes various types of Shiwan-style pots were exported to Việt Nam for use in religious buildings, such as the Tianhou temple (Miếu Thiên Hậu) in Hồ Chí Minh City that was constructed in 1760 (Corfield 2014: 13). The presence of Shiwan-style products from the CâyMai region before 1895 (see Péralle 1895: 55, Figs. 14-15) is supported by archaeological research in the 1990s. Péralle (1895: 57-58) notes that Cây-Mai pottery was not only well known in Cochinchine, but also abroad because the products were unique and affordable. Vietnamese Cây-Mai pottery awaits further study to confirm the role of ceramic production in Saigon in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The Lái Thiêu pottery collection in the HM-HCMC

Lái Thiêu pottery, derived from the Cây-Mai pottery region (in Đề Ngạn/ the former Saigon-Chợ Lớn) migrated in the late 10th century to Lái Thiêu, Bình Dương province (Trần Bạch Đằng 1991: 346; Huỳnh Ngọc Trảng et al. 2009: 40). Lái Thiêu has three main style groups: Guangdong, Fujian, and Chaozhou (Huỳnh Ngọc Trảng et al. 2009). These were created by Chinese craftsmen who lived for generations in Saigon. Their products were used in home decór, architectural decór and kitchens. Although simple in design, the products vary widely in size and detail depending on when they

Fig. 14 A pottery kiln in the Cây-Mai area. (A screenshot from Peralle (1895), “Industrie de la poterie en Cochinchine (Cay-Mai)”. In Bulletin de la Société des Etudes Indochinoises, pp. 54, No.1.)

Fig. 15 The products of a pottery kiln in the Cây-Mai area. (A screenshot from Peralle (1895), “Industrie de la poterie en Cochinchine (Cay-Mai)”. In Bulletin de la Société des Etudes Indochinoises, pp. 59, No.1)

were made (Nguyễn Minh Giao 2001: 37-41). A phoenix-shaped lampstand (BTLS.21357 Fig. 16) is one of 42 artifacts from the end of 19th to the early 20th century in the Lái Thiêu section of the museum (Nguyễn Thị Tú Anh 2014: appendix 1&6). The 30 cm lampstand is enameled in ivory color with a 3 cm crest-like cylindrical candle holder on the bird’s head. The wings cling to the body and are decorated with green painted daubs. Such Shiwan-style pottery has almost disappeared in today’s Vietnamese kilns.

Conclusion

This paper introduces the Vietnamese ceramic collections stored at the History Museum-Hồ Chí Minh City. The objects selected represent sections dating from the 11th to the first half of the 20th century from different locations from the north to the south of Việt Nam today. Many of the ceramics mentioned have been little researched and await the attention of those who love them.

References

Adhyatman, Sumarah.1989. ‘Preface’, Vietnamese ceramics miniatures, pp. 5-8. The Collection of Ulrich J. Beck. Switzerland.

Asian Art Museum of San Francisco. 2006. China: The Glorious Tang and Song Dynasties. Online Educational Units in Asian Art. Available at: <http://afemuseums.easia.columbia. edu/cgibin/museums/search.cgi/ one_by_letter?letters=A-B;museum_ id=2641;page=3>. Accessed on 20/2/2021.

Beck, Ulrich J. 1989. ‘Introduction’ [the Collection of Ulrich J. Beck],

Vietnamese ceramics miniatures, pp. 9-15. Switzerland.

Bonhams. 2017. Fine Asian Works of Art Principal auctioneer: Patrick Meade. Bonhams & Butterfields Auctioneers Corp. Available at: < https://images2. bonhams.com/original?src=Images/ live/2017-12/07/S-24265-0-4.pdf >. Accessed 15/0/2021.

Bùi Minh Trí. 2017. ‘Gốm vẽ nhiều màu Việt Nam’ [ʻVietnamese ceramics painted multicolorʼ], Bulletin of Science: 181-221. Hà Nội: Social Sciences Publications.

Bùi Minh Trí, and Kerry Nguyễn

Fig. 16 Lampstand, BTLS.21357. Lái Thiêu ceramics, 19th century. H: 30 cm.

Long. 2001. Gốm hoa lam Việt Nam (Vietnamese Blue & White Ceramics). Hà Nội: Social Sciences Publication. Colomban, P. H., H. Sagon, Nguyen, Q. Liem, Le, Q. H., L. Mazerolles. 2004. ‘Vietnamese (15th century) blue-andwhite, Tam thai and lustre porcelains/ stonewares: Glaze composition and decoration techniques’. Archaeometry 46, 1. University of Oxford: 125-136. Corfield, Justin. 2014. Historical Dictionary of Ho Chi Minh City. Anthem Press, Wimbledon Publishing Company. Du, He Min. 2020. ‘Cultural Creative Product Design from the Perspective of

annex 1: InscrIptIons

Inscription Object Name dedicated to dedicated by Findspot Date

C.143 silver plate

C.144 silver plate śrī Vanāntareśvara

ajñā po: a royal family member La Thọ, Quang Nam 10th century

La Thọ, Quang Nam 10th century

C.145 silver ewer kalaśa śrī Vanāntareśvara Campāpurapatī: a king La Thọ, Quang Nam 10th century

C.118 silver bowl yāṅ pu nagara rāja oṅ śakrānta urāṅ mandāvijaya: a king Po Nagar, Nha Trang 1197 CE

C.205 silver ewer kalaśa śrī Rudrasvayambhuveśvara śrī Rudravarman: a king mid-9th century

C.206 silver incense burner dhūpādhāra śrī Rudravarman: un roi mid-9th century

C.207 silver plate bhājana śrī Bhadraliṅgeśvara son of śrī Bhadravarman: royal family member mid-9th century

C.208 silver incense holder asaṅ yā̆ parameśvarī ciy pãṅ pu dhiḥ urāṅ rupaṅ: royal family member Po Nagar, Nha Trang 1130 CE

annex 2: table of rItual objects IdentIfIed In InscrIptIons wIth names and dates

Objet name gold silver unknown material

ewer kalaśa C.38 of 784 EC; C.90 C of 1080 EC; C.82 of 1114 EC; C.92 A of 1165 EC; C.30 A3 of 1167 EC.

large ewer

ghaṭa C.38 B of 784 CE; C.30 B3 of 1050 CE

pot, vase kumbha

batā, vatā, vat C.30 A1 of 1084 CE

bhṛṅgāra C.38 B of 784 CE

plate bhājana C.31 A2 of 1064 CE; C.30 B3 of 1050 CE; C.92 A of 1165 CE

tray suvauk, suvok C.6.1 of 1244 CE

incense burner asaṅ (dhūpa) dhūpādhāra

C.31 A2 of 1064 CE

C.61 of 892 CE; C.145 end of 9th c.; C.205 end of 9th c.; C.142 B of 908 CE; C.30 B3 of 1050 CE; C.90 of 1080 CE

C.24 B of 801 CE

C.30 A3 of 1183 CE.

C.61 of 892 CE; C.142 B of 908 CE; C.30B3 of 1050 CE; C.31 A2 of 1064 CE.

C.24 B of 801 CE; C.207 end of 9th century; C.142 B of 898 CE and 908 CE; C.31 A2 of 1064 CE; C.30 A3 of 1183 CE.

C.206 end of 9th c.; C.30 A1 of 1084 CE; C.208 of 1130 CE

C.31 A2 of 1064 CE; C.92 A of 1165 CE

annex 3: table of rItual objects classed by date and provenance

Date

late 9th c.

late 9th c.

late 9th c.

late 9th c.

1050 CE

1064 CE

1080 CE

1084 CE

1114 CE

1130 CE

1165 CE

1167 CE

1183 CE

1183 CE

C.205

C.206

Đồng Dương

Đồng Dương

C.207 ?

C.145

C.30 B3

C.31 A2

La Thọ

Po Nagar, Nha Trang

Po Nagar, Nha Trang

C.90 C Mỹ Sơn

C.30 A1

C.82

C.208

C.92 A

C.30 A3

C.31 A2

C.30 A3

1197 CE C.118

Po Nagar, Nha Trang

Mỹ Sơn

Po Nagar, Nha Trang

Mỹ Sơn

Po Nagar, Nha Trang

Po Nagar, Nha Trang

Po Nagar, Nha Trang

Po Nagar, Nha Trang

1244 CE C.6.1 Phan Rang

Bibliography

Anonymous. 1911. ̒Chroniqueʼ. BEFEO 11: 471-2.

Aymonier, Étienne, ‘Légendes historiques des Chame’, Excursions et Reconnaissances XIV n°32 (1890): 145-206.

________________, Les Tchames et leurs religions, Paris, 1891.

Aymonier, Étienne & Cabaton, Antoine, Dictionnaire Cam-Français, Paris, Leroux éd., 1906.

Cabaton, Antoine, Nouvelles recherches sur les Chams, Publications de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient, Paris, 1901.

Claeys, Jean-Yves, ‘Chronique. G. Binh-thuan. Phan-ly cham’, BEFEO 28 N°3(1928): 608-610.

Cœdès, George, et Parmentier, Henri, Listes générales des inscriptions et des monuments du Champa et du Cambodge, 1923, Hanoi, Imprimerie d’ExtrêmeOrient.

Cœdès, George, Inscriptions du Cambodge, vol. 1, Hanoi, 1937.

Durand, Eugène-Marie. ‘Notes sur les Chams. IX. L’Abhisheka cham’, BEFEO VII 1907: 345-351.

Filliozat, Jean, ‘Çivaisme et bouddhisme au Cambodge’, BEFEO LXX, 1981: 95.

Griffiths, Arlo, Lepoutre, Amandine, Southworth, William & Than Phan, ‘Études du corpus des inscriptions du Campā III. Épigraphie du Campā 2009-2010: prospection sur le terrain, production d’estampages, supplément à l’inventaire’, BEFEO 95-96 (2008-2009): 435-97.

Lafont P.-B., Po Dharma & Nara Vija, Catalogue des manuscrits cam des bibliothèques françaises, Publications de l’École française d’Extrême-Orient Volume CXIV, 1977, Paris. Moussay, Gérard, Dictionnaire CamVietnamien-Français, Centre culturel

Quảng Nam

Quảng Nam

Quảng Nam

Quảng Nam

Khánh Hòa

Khánh Hòa

Quảng Nam

Khánh Hòa

Quảng Nam

Khánh Hòa

Quảng Nam

Khánh Hòa

Khánh Hòa

Khánh Hòa

Khánh Hòa

Ninh Thuận

Cham, Phanrang, 1971.

Ner, Marcel, ‘Chronique’, BEFEO 30(1930): 552-76.

Nghiêm Tham, ‘Sơ-lược về các kho-tàng chứa bảo vật vua Chàm’ (Report on the Cham treasures », Việt-nam Khảo-cổ tập san (Bulletin on the Historical Research Institut of Viêt Nam), 1(1957-59) : 151-163.

Parmentier, Henri, ‘Chronique’, BEFEO I, fasc. 4, 1901, p. 409-411.

Parmentier, Henri, ‘Découverte de bijoux anciens à Mi-son’, BEFEO 1903 : 664-5.

Parmentier Henri et Durand EugèneMarie, ‘Le trésor des rois chams’, BEFEO 5(1905) : 1-46.

Phạm Hữu Mý & Vương Hải Yến ‘Collection of Champa artefacts in the Museum of History of Viet Nam – Ho Chi Minh City’ in Sưu tập hiện vật Champa tại Bảo tàng Lịch sử Việt Nam Thành phố Hồ Chí Minh (Champa

of the Medieval Climate Anomaly (leading to the dryer and cooler Little Ice Age), Jaya Siṅhavarman’s active royal development programme brought not only stronger political control, but also needed local economic development.

By 1300 CE, Nagara Campā under the Vijayan kings ruled the Austronesian coast of the mainland’s eastern seaboard. Though contesting its north with the Vietnamese, they controlled the centre, the west, and the south. While factionalism might occur at the royal court, hereafter there appears to have been no further inter-regional conflict along this coast. Thus, I would argue that instead of the dichotomy of one vs. many realms of this land, there was instead a thousand year process (say 300-1300 CE) in which the numerous river valley communities of this coast formed their own realms and then finally, after several efforts, merged into the one realm of Nagara Campā, becoming Cams in the process. The Cams of the Thu Bồn valley emerged as a community, then brought about the realm of Nagara Campā. Indrapura moving north in the ninth and tenth centuries created a greater Campā. Siṅhapura in the eleventh and twelfth centuries merged south and north. Vijaya in the thirteenth century completed this effort. In the south, Kauṭhāra dominated Pāṇḍuraṅga and brought both into Nagara Campā. Nevertheless, it took Vijaya’s ritual and economic efforts to ensure that the south was Cam and came under Nagara Campā’s one umbrella.

References

Griffiths, Arlo and Southworth, William. 2011. ‘Étude du corpus des inscriptions du Campà-II. La stèle d’installations de Sri Ādideveśvara: Une nouvelle inscription de Satyavarman trouvée dans le temple de Hoà Lai et son importance pour l’histoire du Panduranga’. Journal Asiatique, No. 299.1(2011) : 271-317.

Griffiths, Arlo, Hardy, Andrew Geoff Wade, Geoff. 2019. Campā: Territories and Networks of a Southeast Asian Kingdom. Champa: Territories and Networks of a Southeast Asian Kingdom. Paris: École française d’ExtrêmeOrient.

Hardy, And etworks of a Southeast Asian Kingdom. Champa: Territories and Networks of a Southeast Asian Kingdom (eds. Arlo Griffiths, A. Hardy and G. Wade) Paris: École française d’Extrême- Orient: 221-252.

Lieberman, V. & Buckley, B. 2012. ‘The Impact of Climate on Southeast Asia, circa 950–1820: New Findings’. In Modern Asian Studies, Volume 46,

Issue 5, September 2012: 1049-1096. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/ S0026749X12000091

Lepoutre, Amandine. 2013. «Études du corpus des inscriptions du Campā, IV: Les inscriptions du temple de Svayamutpanna: contribution à l’histoire des relations entre les pouvoirs cam et khmer (de la fin du XIIe siècle au début du XIIIe siècle)». Journal Asiatique. 301 (1): 205-278. doi:10.2143/JA.301.1.2994464.

Momoki, Shiro. 1999. ‘The Dry Areas in Southeast Asia: Harsh or Benign Environment?’. In Final Report of a Cooperative Project under the KyotoThammasal Core University Program, Fukui Hayao, Ed, (The Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Tokyo University, March 1999).

Schweyer, Anne-Valérie. 2004. ʻPo Nagar de Nha Trang (1re partie)ʼ, Aséanie 14, December 2004: 109-140. DOI : 10.3406/ asean.20034.1830

Schweyer, Anne-Valérie. 2005. ʻPo Nagar de Nha Trang. Seconde partie : Le dossier épigraphiqueʼ, Aséanie: <https://doi.org/10.3406/ asean.2005.184710.3406/ asean.2005.1847>

Southworth, William. 2012. ‘Religious architecture and irrigation in the plain of Phan Rang’. In Old myths and new approaches: Interpreting ancient religious sites in Southeast Asia (ed. Alexandra Haendel). Australia: Monash University Publishing: 263-283.

Vickery, Michael .2011. ‘Champa revised’. In The Cham in Vietnam: History, Society and Art. Eds Trần Kỳ Phương and Bruce M. Lockhart. Singapore: NUS Press: 363-420.

Zolese, Patrizia .2009. ‘Results of the Archaeological Investigations at Mỹ Sơn G Group (1997-2007)’. In Champa and the Archaeology of Mỹ Sơn (Vietnam) (eds Andrew Hardy, M. Cucarzi and P. Zolese). Singapore: NUS Press: 197-237.