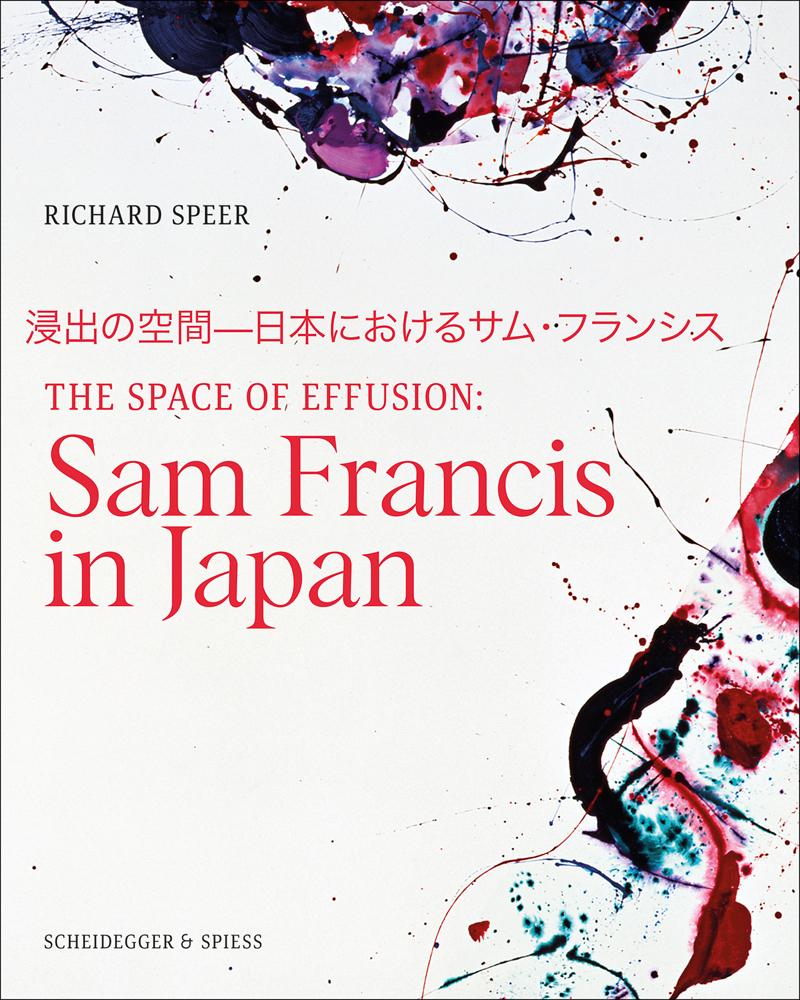

Sam Francis’s engagement with the world, coupled with his fascination and involvement with different cultures, particularly Japan, is explored in Richard Speer’s compelling monograph The Space of Eff usion: Sam Francis in Japan, as well as in the related exhibition “Sam Francis and Japan: Emptiness Overflowing,” scheduled installation for 2020–21 in the Resnick Pavilion at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), California. One of the twentiethcentury’s most profound Abstract Expressionists, Sam Francis was one of the few visual artists who traversed the globe multiple times during the 1950s and 1960s, becoming one of the fi rst post-World War II American painters to develop a truly international reputation. A bit of an outlier, Francis was not rooted to one locale during his five-decade artistic career. He spent time working in France, Mexico, Switzerland, and Japan as well as New York and California, creating thousands of paintings, works on paper, prints, and monotypes. His works reference the places he lived and worked, including nods to the New York School of painters, French Impressionism, Chinese and Japanese art, and his own Bay Area roots. As Speer articulates in his text, with a focus on Japan, the different styles, techniques, and artistic influences Francis encountered through his travels informed the development of his own visual dialogue and unique style of painting. Shūzō Takiguchi, a noted Japanese art critic and poet, described his friend’s wanderlust as almost mystical in nature, seeing Francis as “a colorful unsui —a Zen monk who has no place to live and is destined to

roam the country, his only permanent abode being within himself” (quoted in Tsujii 1987). Agreeing with Takiguchi’s assessment, Takashi Tsujii (aka Seiji Tsutsumi) indicated that he could not think of a more accurate and revealing description of Francis’s characteristics. The spirit of unsui, which loosely translates as “cloud water,” echoes descriptions of Francis drifting like a “free-floating cloud” (the title of a 1980 mural), always on the move and trying to escape limitations. The reference to water is also fitting in regard to Francis and his painting, with its connotations of beginnings, life, and the eternal.

The opportunity for an in-depth exploration of Francis’s ties to Japan arose in 2011 after I read an Art Ltd. magazine review of Francis’s oeuvre by Richard Speer. I was not acquainted with the author but was immediately drawn to his poetic and sensuous response to Francis’s aesthetics. We met, and after a period of general back-and-forth correspondence, the Sam Francis Foundation supported his proposal to write an essay and curate an exhibition focused on the artist’s Japanese influences. What followed was an organic flow of connections with Bruce Polichar, a Sam Francis Foundation board member, who introduced me by email to Hollis Goodall, curator of Japanese art at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Goodall was very enthusiastic about the show’s premise, and soon Leslie Jones, curator of prints and drawings, joined the LACMA curatorial team. The resulting exhibition focuses on the confluence of Francis and Japan by pairing his works with art from historical Japanese

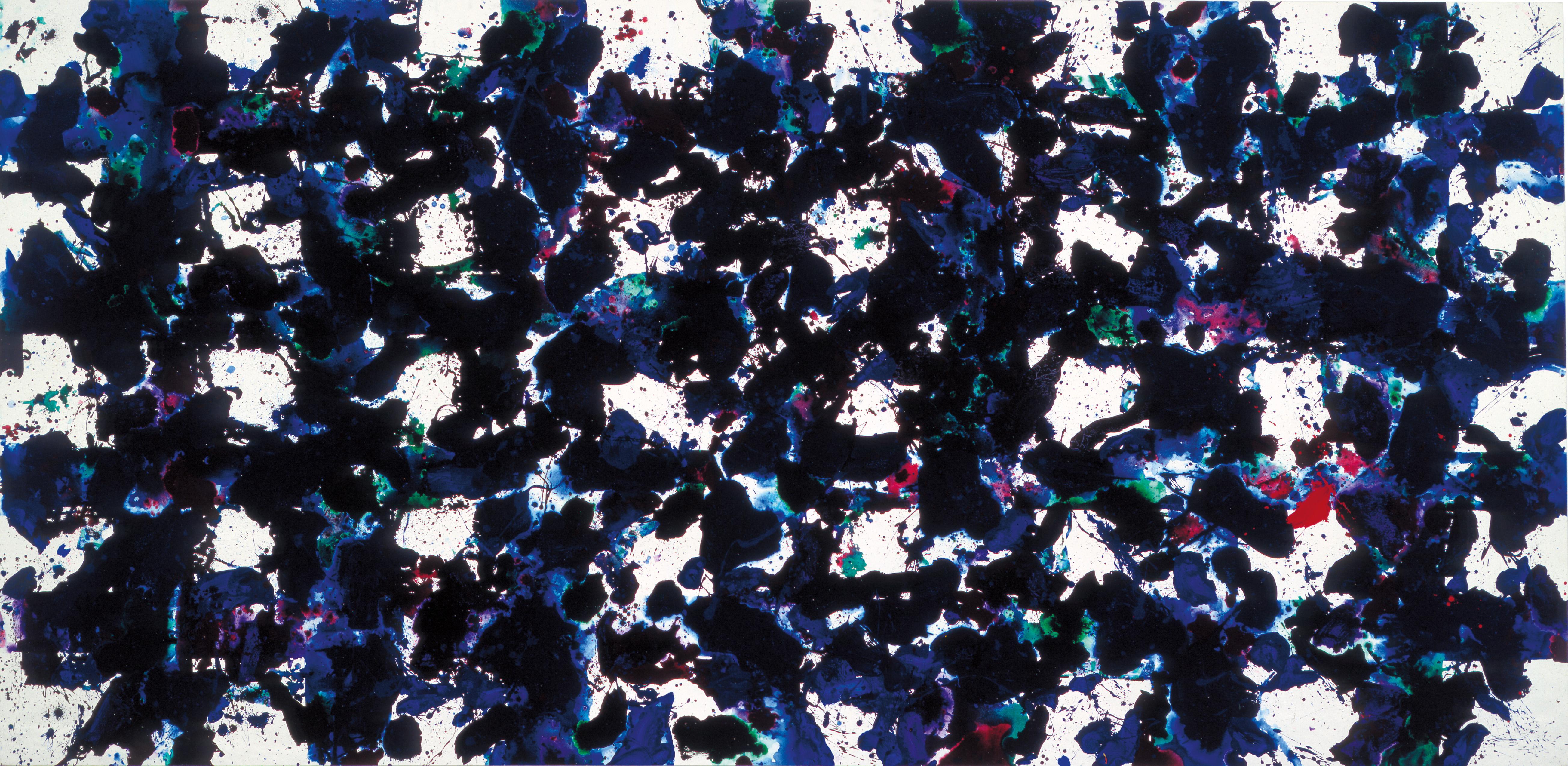

4 Sam Francis, Free Floating Clouds, 1980. Acrylic on canvas, 317.5 x 645.16 cm (125 x 254 in.), created in Los Angeles (Santa Monica). The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens, San Marino, California, Gift of the Sam Francis Foundation, California (A2008.30). Photo by Brian Forrest, Santa Monica.

13 Sam Francis began painting while confi ned in a full-body plaster cast for treatment of spinal tuberculosis. In this partial view, his stepmother Virginia Francis sits behind him as he is hoisted above his hospital bed on a Bradford frame allowing him to paint in a prone position. Fort Miley Veterans Hospital, San Francisco, March 1946. Photo by Acme, San Francisco Bureau.

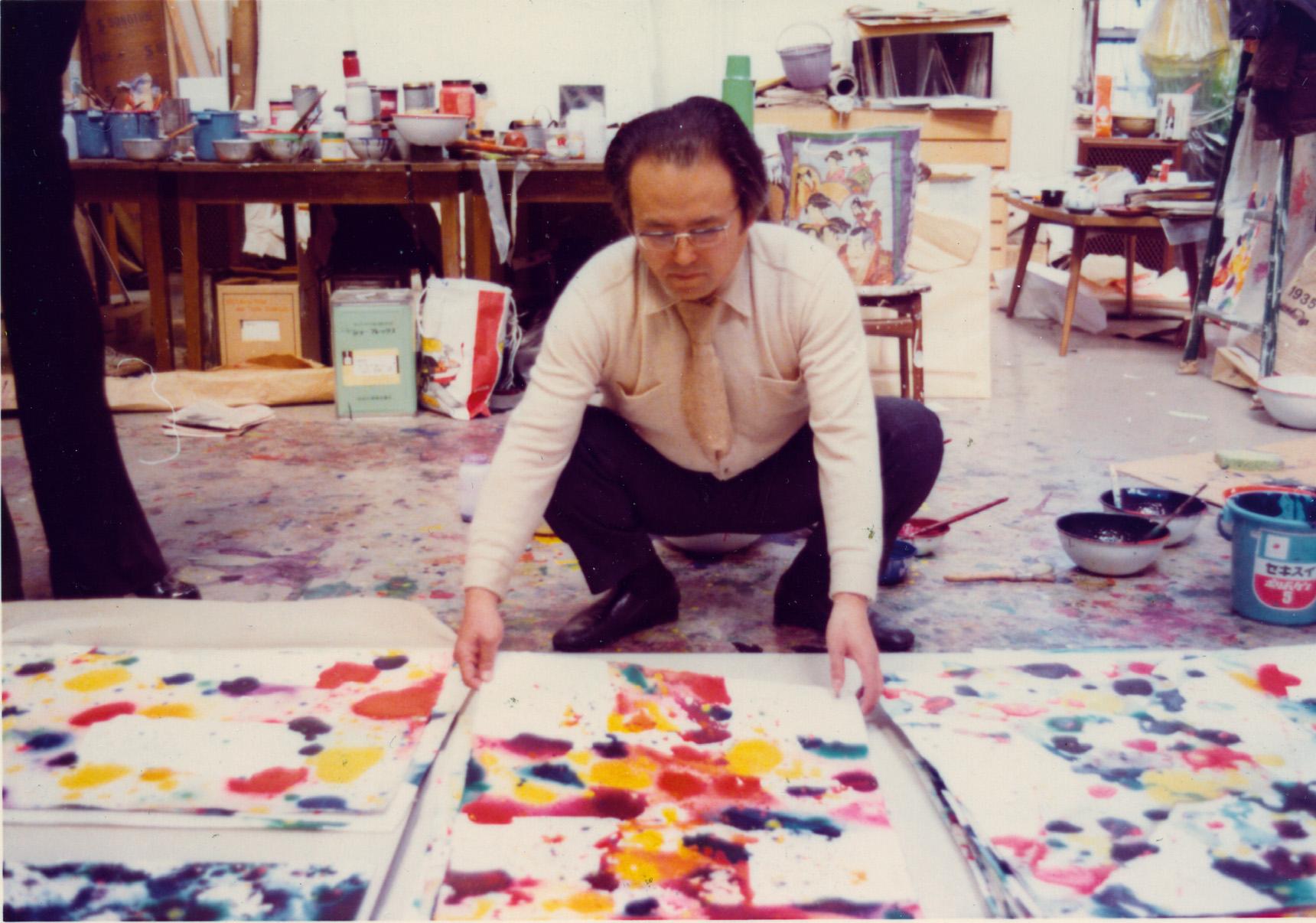

Fig. 26 Sam Francis, Untitled Triptych, 1983. Acrylic on canvas, overall dimensions estimated 243.84 x 852.17 cm (96 x 335 1/2 in.) , created in Los Angeles (Santa Monica). Museum of Modern Art, Toyama, Japan, Gift of The First Bank of Toyama Co. through Nantenshi Gallery, Tokyo (1989). Photo by Brian Forrest, Santa Monica.

Figs. 27–28 Yamaguchi Soken (Japan, 1759–1818), Flowers and Plants of the Four Seasons, Edo Period, late eighteenth–early nineteenth century. Pair of six-panel screens, ink and color on gold leaf paper, each overall 154.3 x 254.1 cm (60 3/4 x 100 1/16 in.). Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA), Japanese Art, Gift of Jerry Louise and Robert Johnson (M.82.149.2a–b). Photo © Museum Associates/LACMA.

Fig. 47 Sam Francis, Water Buffalo, 1964. Lithograph, edition of 50, 49.53 x 38.1 cm (19 1/2 x 15 in.), created in collaboration with poet Makoto Ōoka. Printed by the Japanese Art Association and printer Koyama, Tokyo. Photo courtesy Kanagawa Museum of Modern Literature, Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan.

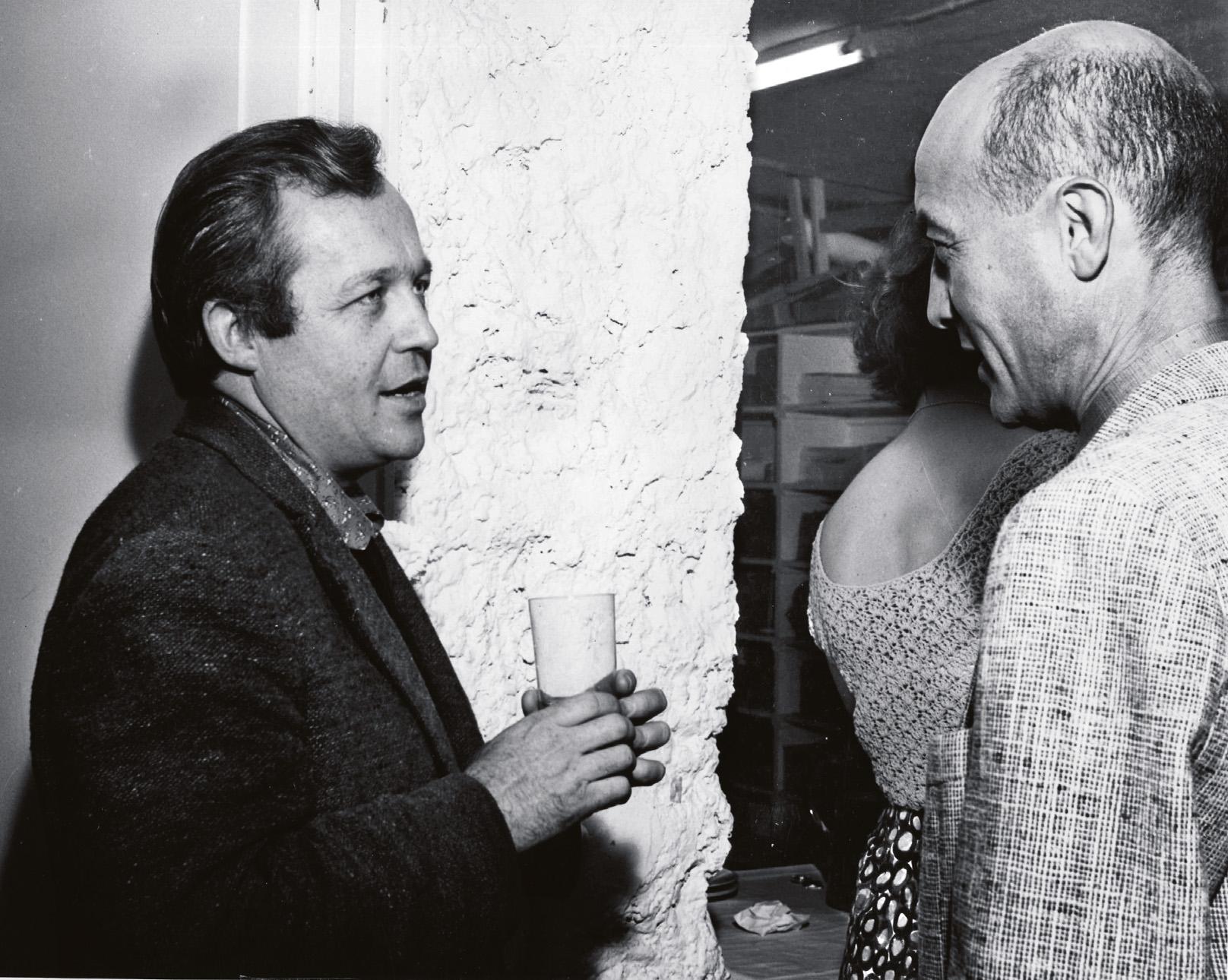

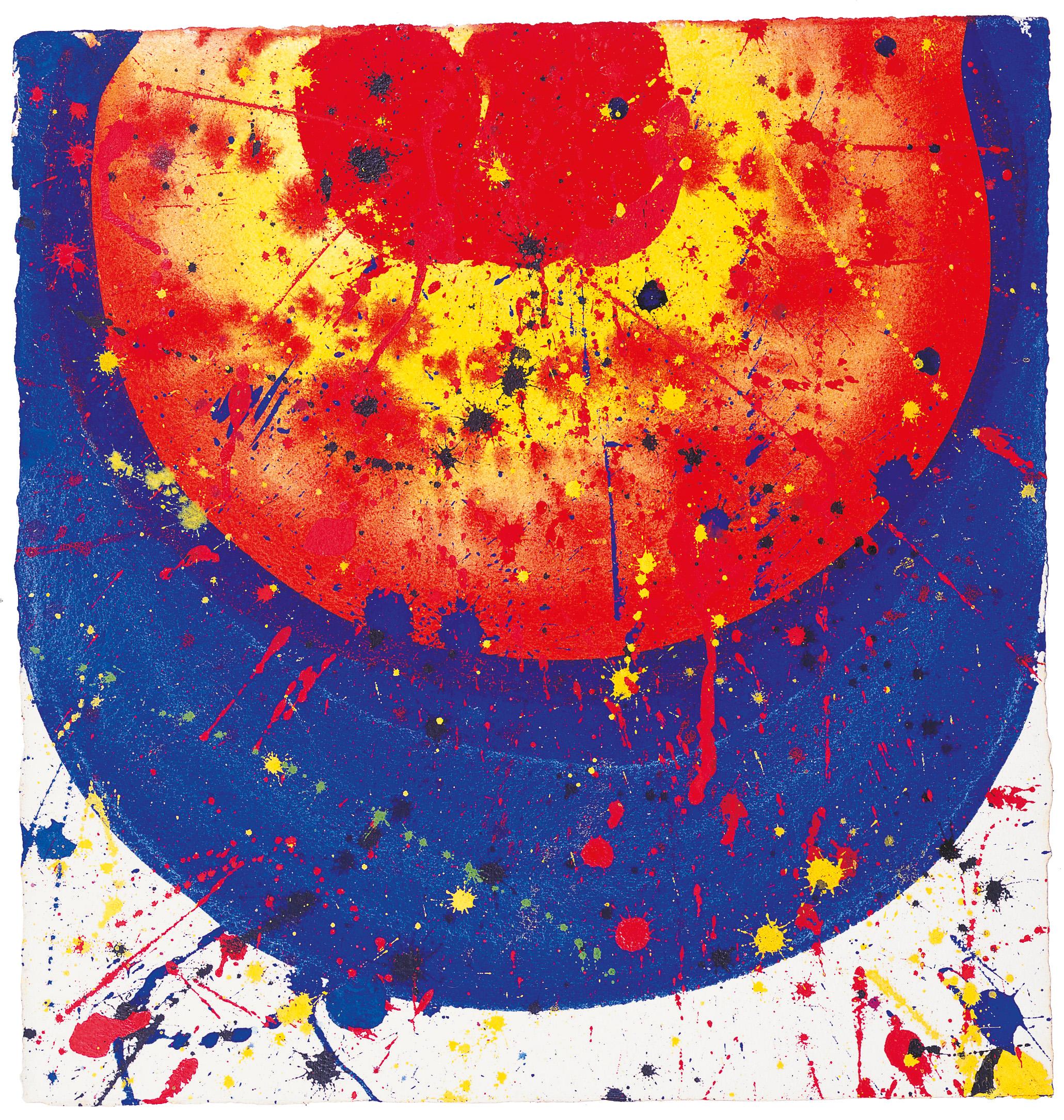

During his many trips to Japan in the early to mid-1960s, Francis made fast friends of the painter-cum-journalist Hideo Kaido (1912–1991), who was cultural chief at the Yomiuri Shimbun newspaper, and the poet/critic Makoto Ōoka (1931–2017), founder of the renshi poetry movement and a page-one columnist for two decades at the leading national newspaper, Asahi Shimbun. Ōoka, who had been a schoolmate of Tōno’s and socialized in the same circles, sometimes translated press materials for Francis’s exhibition space, Minami Gallery, into English. Other times, when the painter needed to write to Japanese business associates, he would call upon Ōoka’s help. During the poet’s long life (he died at age 86), he collaborated with Francis on a number of creative projects. One of the fi rst was a 1964 lithograph of Francis’s, Water Buffalo, after an Ōoka poem of that title. The poem is illustrated by a jaunty, primary-colored composition, with gestures spilling over onto the text, which reads in part: “i too raise in my backyard/ a water buff alo who eats flowers/ people who dare touch him/ always feel that he is too big/ to exist in this world.” It was printed in an edition of 50, with sales benefiting the Japanese Art Association. In 1989–90, when Francis’s health was beginning to fail, Ōoka revised an extraordinary poem he had fi rst written in 1974, a rhapsodic ode to the painter’s fabled white spaces entitled “Dreaming Sam Francis” (1974, n.p. and 1995, 31–33):

Ōoka, Takiguchi, Kawai, Tomioka

One of the painter’s most memorable exhibitions at Minami was the July 1977 show “Sam Francis: 36 KAOS (Faces), 1973–1977,” which later traveled to Galerie Kornfeld in Bern, Switzerland. This was the fi rst showing of his self-portraits, still perhaps his least-known body of work he continued to explore through the 1980s. At the opening, attendees (among them Mako Idemitsu, Arata Isozaki, and Shūzō Takiguchi) posed for photographers in front of the portraits, intimating a kinship between themselves and the images. Deceptively simple in their naïve figuration, they show the artist in a profoundly introspective mode. While some are whimsical, others betray the darker sides of his psyche. Some show him embracing the influence of Sengai; in one Untitled (Self Portrait) (SF62-001) he depicts his visage in an Asian style; in another (SF74-46) he paints himself wearing a Ninja mask. He was also intrigued by Noh masks, and some of his self-portraits show this influence. Art critic and scenester Yvonne Hagen recalled in her memoir, From Art to Life and Back , that in the late 1950s, after his fi rst visit to Japan, he returned to Paris with several Noh masks. One night, there was “a party he gave in a large studio south of Porte d’Orléans.” At one point,

to the delight of his guests, he brought out an “enormous Noh-theater tiger mask, with its hairy head and long mane dragging behind it” (2005, 201–2).

Francis showed at Minami for more than two decades. At the end of the 1970s, during the historic economic downturn known as the 1979 oil crisis, Shimizu found himself beset with major money problems that seemed irresolvable. In 1979, at age 52, he committed suicide. A devastated Francis flew to Japan to attend the memorial service, sitting beside Tōno in the front row. He stayed with Shimizu’s family several weeks afterwards to mourn with them. Later that year he created a Matrix painting entitled Requiem for Shimizu . In 1981 he spearheaded the publishing of Homage to Kusuo Shimizu , a volume of lithographs by artists associated with the gallery, including himself, Christo and Jean-Claude, Jean Tinguely, Claes Oldenburg, and Jasper Johns. On the second anniversary of Shimizu’s death, the folio debuted at an exhibition at Nantenshi Gallery, which Francis migrated to after Shimizu died. Sales of the print portfolio helped fund the dedication anthology, Kusuo Shimizu & Minami Gallery in 1985. The book contains a preface by Makoto Ōoka, with reminiscences and condolences from

135 Sam Francis’s painting gifted to Makoto Ōoka, This is as it is all the Rest is Darkness , ca. 1964. Acrylic and/or gouache on paper, 40.5 x 38.6 cm (15 15/16 x 15 3/16 in.). Ōoka Makoto Kotoba Museum, Mishima, Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan. Photo courtesy Ōoka Makoto Kotoba Museum.