i n t ro d u c e d by D AV I D H E M S O L L

P A L L A S

A T H E N E

by

p. 7

by GIORGIO VASARI

p. 35

List of illustrations

p. 254

DAVID HEMSOLL

The vie w that Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) was the greatest ar tist of his age was a widely shared one in the sixteenth centur y. He was, after all, personally responsible for several of the most ambitious and impressive creations of recent times in painting, sculpture and also architecture, such as the David, the Sistine Chapel ceiling, the Last Judgment and much of the rebuilding of Ne w St Peter’s. This vie w, however, received its fullest and most power ful literar y expression in the biography of Michelangelo forming par t of the Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptures and Architects, a work written by Giorgio Vasari (1511-74) and published in Florence originally in 1550 and again, in expanded form, in 1568. The Lives was itself a monumental enterprise, and one that has since come to be regarded as the prime initiating work of what is known as ar t histor y. Penned by a man who was also one of the most prolific and successful painters and architects of his day, it provides an extraordinar y mass

Opposite: The Crucifixion with the Virgin and St. John, c. 1555-64

of detailed and mostly reliable information about all the main Italian ar tists of the previous three hundred years and all the major works that they produced; and, indeed, it has continued to be fundamental to our knowledge and understanding of Renaissance ar t, as attested to by the sheer number of subsequent editions and translations of the 1568 edition, including the one used for this publication. Vasari’s Life of Michelangelo (‘Michelagnolo’ in the Florentine dialect) which was also issued as a separate booklet just a little later, exemplifies this achievement and supplies a vast multitude of facts about the ar tist’s career and all its many triumphs and, in addition, equips the reader with many ready insights into how his works should be appreciated and provides many instant verdicts on their numerous special merits.

Although Vasari himself declared that the Lives were written for the principal benefit of ar tists, the book was plainly meant to be of value too to connoisseurs and anyone else with a stake or interest in the visual ar ts. It was, admittedly a work of some over t but understandable par tiality towards his adoptive city of Florence but, at the same time, it was also one of some ver y considerable intellectual ambition. Above all, it was conceived in such a way as to elucidate an overall

concept of a gradual but sustained improvement in the visual ar ts, from a low point in the Middle Ages up to a level on a par with – or even surpassing – the achievements of classical antiquity. Vasari did this, in good par t, by organising the book into three par ts, each with an explanator y preface and corresponding to one of three successive periods. The first of these periods, which we now think of as being just prior to the Renaissance, ‘prepared the way and formed the style for the better work which followed’; the second, corresponding to what is now widely termed the Early Renaissance, was one of ‘manifest improvement’; and the third, now thought of as the High and Later Renaissance, was when ar t was finally to reach ‘the summit of per fection’. A fur ther stratagem was to present each of these three periods as having been initiated by individual ground-breaking figures, a schema which ver y notably reflected a Florentine bias and still lingers on in many sur veys of Renaissance ar t today. Thus, for his first period, Vasari identified Giotto as the pioneer in painting although alongside two rather less deser ving Florentines in sculpture and architecture; and, for his second, he dre w justified attention to the Florentines Br unelleschi in architecture, Masaccio in painting and, in par ticular, Donatello in sculpture, whom he said he was minded to place in the third 9

period ‘since his works are up to the level of the good antiques’. For this third period, however, Vasari was less for tunate with the realities of histor y, as is ver y clear from the preface to the third par t, but he still made the best use of it he could, and did so too with one ver y clear final aim ver y much in his mind. He envisaged this period in such a way that it commences rather arbitrarily with the Florentine Leonardo da Vinci as its chief instigator in painting, thereby giving him precedence over such pioneering younger ar tists as Giorgione of Venice and Raphael of Urbino, but he then gave supremacy over them all to Florence’s Michelangelo, whom he judged in both painting and sculpture, although conveniently ignoring architecture at least for the moment, to have eclipsed all others, and therefore to be the greatest ar tist not only of his age but of all time.

Michelangelo’s por trayal in the Lives as the most accomplished of all ar tists, and as the ver y apogee of ar tistic progress, in fact underlies the book’s whole str ucture, although this was much more readily apparent in the original 1550 edition. In this first edition, the three par ts were of much more comparable size, w i t h t h e b i o g r a p h y o f Mi c h e l a n g e l o , w h i c h w a s already by far and away longest, being placed right at the end, and so providing a more balanced and

orderly work with a logical termination. The by now elderly but still ver y active Michelangelo, moreover, was accorded the unique privilege of being only ar tist included who was then still alive. In the revised 1568 edition of the Lives, however, much of this clarity was lost as a result of the book’s third par t being greatly expanded with ne w biographies of those ar tists who had either died since 1550 or who, like Titian, were still living, and with that of Michelangelo, who had since passed away, being now followed by a number of others. Michelangelo’s biography, however, was now substantially longer even than in 1550, to become several times the length of those of his main ar tistic rivals Raphael and Titian. In consequence, it provided an even greater oppor tunity for detailing and explaining Mi c

abilities.

Only in its final form, therefore, was the biography

Arranged ver y much like a classical biography, it consists of a detailed description of his career which is then followed by fur ther material of a more general nature. The account of Michelangelo’s career begins with his auspicious bir th and early training and it chronicles his early works, including the Bacchus ( 1 4 9 6 - 7 ) and the St Peter’s Pietà ( 1 4 9 7 - 9 ) in Rome,

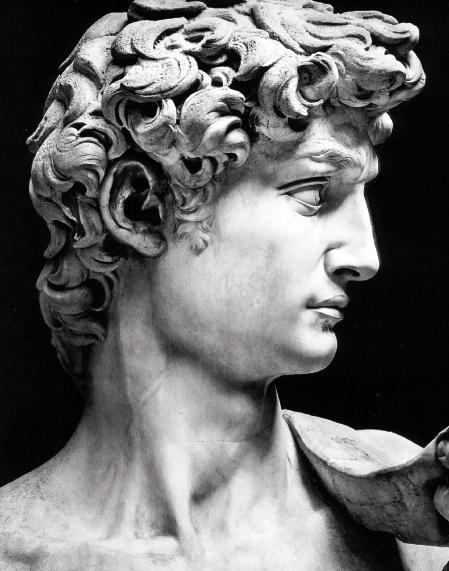

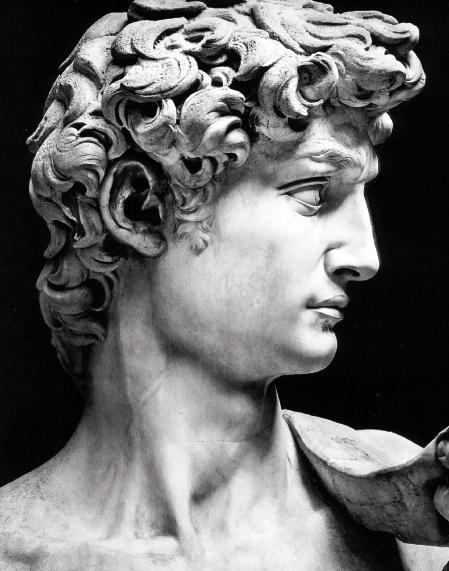

before coming to the colossal and extraordinar y statue of David ( 1 5 0 1 - 4 ) in Florence and his unexecuted scheme for the enormous painting of the Battle of Cascina ( 1 5 0 4 - 5 ). The narrative then turns to Rome and the commission of the ill-fated Julius tomb ( 1 5 0 5 ) and its various sculptures, and to the execution of the remarkable Sistine Chapel ceiling ( 1 5 0 8 - 1 2 ); and then back to Florence to char t the unexecuted project for the façade of S. Lorenzo ( 1 5 1 7 - 2 0 ), the architecture and sculpture of the Ne w Sacristy (from 1 5 1 9 ) and the design of the Laurentian Librar y (from 1 5 2 3 ), togethe r w i t h d e f e n s i ve w o rk s Mi c h e l a n g e l o s u p e r v i s e d before and during the siege of Florence ( 1 5 2 9 - 3 0 ). Michelangelo’s subsequent career in Rome begins with a detailed discussion of the Last Judgment ( 1 5 3 44 1 ) and then continues with coverage, albeit sometimes rather cursor y, of the frescoes in the Pauline Chapel (from 1 5 4 2 ), the Florence Cathedral Pietà (from c. 1 5 4 7 ) and various late architectural works in Rome, including the Capitoline Palaces, the Por ta Pia a n d h

i Fiorentini, although it also devotes a ver y great deal of space to the documentation of his constant labours on Ne w St Peter’s (from 1 5 4 6 ) and to various works of consultation. This par t of the biography then concludes with an account of Michelangelo’s death and

A battle scene, c. 1504.

Probably a study for the background of the Battle of Cascina, painted in rivalr y with Leonardo

with a summar y of the overall nature of his achievement. It is followed, however, with a great deal of further information, not always ver y cogently str uctured, about such matters as his character, his austerity in private life, and his generosity in friendship, which then leads to a digression on his practice of making drawings as gifts, and also about his fondness for witty obser vation and about his health and appearance. The biography finally ends with an account of the surreptitious removal of Michelangelo’s body from Rome to Florence and a ver y lengthy description of his spectacular civic funeral. I n r e d r a f

n g t h e L i f e , Va s a r i m a d e

i v e changes to its content. The original version had traced Michelangelo’s career up until the Last Judgment, and so had terminated before the discussion of St Peter’s and the rest of the late work, and it had done so in a fairly well organised and evenly paced manner. The 1 5 6 8

material, as well as the description of the funeral, which closely follows an account of it first published for the occasion as a pamphlet, and so it became much fuller but rather less well str uctured than before. It was

Opposite: preparatory sketch for The Fall of the Chariot of the Sun (or The Fall of Phæton), a gift for Tommaso de’ Cavalieri; sent to Tommaso for approval, 1533

also markedly different in tone in that, for the first version, Vasari had just used material derived from reliable sources to hand and so with little if any of it coming from Michelangelo directly, whereas, for the revised version, he now made full use of his own more recent acquaintance with Michelangelo, and did so by making frequent reference to his personal dealings with the ar tist, as well as reproducing several actual letters that had passed between them. In this way, the revised Life gained a ne w authenticity and credibility by giving an impression that it had been approved by Michelangelo himself. The 1568 version, however, was not just an extended version of its predecessor. It was also substantially re written to take account of another biography of Michelangelo that had appeared in 1553, a work produced by Michelangelo’s own pupil Ascanio Condivi and containing a great deal of material, much of it gleaned from Michelangelo himself, that Vasari had not originally included. Much of this new information Vasari duly incorporated, including Condivi’s contention that the artist’s ancestral lineage could be traced back to the illustrious and noble Canossa family, as well as a great many new details relating to the protracted histor y of the Julius tomb. Yet Vasari certainly did not consider ever ything in Condivi’s biography to be reliable, as he made abundantly clear when describing

Michelangelo’s ar tistic training in the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio. His original account of this had been explicitly contradicted by Condivi who had insisted instead that Michelangelo had never had any teacher, but Vasari was now to prove his position by publishing the actual official record of Michelangelo’s apprenticeship. This rebuttal of Condivi, however, was not simply a matter of scholarly vindication, since Vasari could not afford, in either 1550 or 1568, to be shown to be factually inaccurate and was, as he put it, making his point in the ‘interests of tr uth,’ in just the same way that he was recording all the rest material in the biography. For this ‘ tr uth’ not only applied to the detail of Michelangelo’s life but also supplied the ver y foundation, as Vasari surely must himself have genuinely believed, to the whole estimation of his ar t.

The Life, in fact, is not a tr ue biography in the strictest sense but, rather, an account of Michelangelo as an ar tistic personality to the exclusion of almost ever ything else. As such, it deals only with his ar tistic career and matters directly impinging on it, such as his close personal relationships with popes and other illustrious patrons. It cer tainly includes many amusing a n e c d o t e s , a m o n g w h i c h a re s e ve r a l i n c i d e n t s o f Michelangelo bettering those who did not sufficiently understand or value his ar t, such as his patron Agnolo

Doni who attempted to acquire the painting of the Holy Family that Michelangelo produced for him at a knock down price only to end up having to pay double the originally agreed amount; or the agent of the duke of Ferrara who made disdainful comments about the painting of Leda Michelangelo commissioned by his master only to see him refuse to hand it over and give it instead to one of his pupils. It also freely acknowledged some of Michelangelo’s more notorious or eccentric working practices, such as his obsession for working in solitude and secrecy or, more personally, his habit of sometimes not getting round to changing his clothes. On the other hand, the Life pays little or no regard to other aspects of Michelangelo’s world. Thus it provides vir tually no insight into his relationships with other members of his family, and no explanation of the animosity borne him by such figures as duke Alessandro de’ Medici, and, famously, it makes no direct mention of his romantic inclinations, or even of whether he ever had any. Nor does it make any reference to events in the wider world, however momentous, unless they had made an immediate impact on Michelangelo’s professional activity, or any

Opposite: The Entombment (unfinished), c. 1501-02

acknowledgement that changes in society had made any effect on his work. The Life, in fact, is not only centred on Michelangelo’s ar tistic career but it does so in such a way as to show it to best advantage. Consequently, it makes little comment on Michelangelo’s recognised abilities as a poet, so as not to detract from his much higher accomplishments in ar t. It also cleverly marginalises some of Michelangelo’s less successful ventures, such as making only the barest mention, inser ted towards the end of the Life, of his time spent in collaboration with the Venetian painter Sebastiano del Piombo, after completing the Sistine Chapel ceiling, when the two were engaged on producing works in direct competition with Raphael.

Vasari conveyed Michelangelo’s ar tistic excellence, to a great extent, by simply asser ting the various special qualities and note wor thy features of his individual works. This technique can be seen to par ticular effect, for example, in the description of the St Peter’s Pietà, where the prose, although flower y, is especially powerful, and the work is described as demonstrating ‘the utmost limits of sculpture,’ with the figure of the dead Christ representing the ‘miracle that a once shapeless

Opposite: Christ at the Column, 1516, prepared for Sebastiano del Piombo’s Flagellation of Christ, S. Pietro in Montorio, Rome

stone should assume a form that Nature with difficulty produces in flesh.’ A similar strategy was followed for many other works, and par ticular so for the preliminar y car toon for the Battle of Cascina, the Sistine Chapel ceiling, and the statue of Night in the Ne w Sacristy, which if completed Vasari says would have s h o w n h

‘

y thought.’ The same strategy is also followed for the Last Judgment, which is ver y much a tour de force of this approach, and here Vasari’s intention was not just to pronounce on the painting’s many merits but to do so in such a way that would flatly contradict many of the contemporar y criticisms, some quite justifiable, that were being levelled at it by detractors such as Pietro Aretino, who had scathingly attacked it in a letter addressed personally to Michelangelo of 1545. Thus, in tacit response to Aretino condemning the nudity as unsuitable to the pope ’ s official chapel, Va

‘

appropriate to such a work;’ and in defiance of the widely held vie w of Michelangelo’s shor tcomings in his representation of women, and in painting’s more demanding refinements, Vasari instead insists on his

Opposite: Angels with instruments of the Passion, St Peter with other saints below, from the Last Judgment, 1534-41

earlier had acquired the body of St Mark for their city. For these devout followers, their faith in him would have been all the more confirmed when his coffin was briefly opened, and his body was found, like many a saint’s, as not showing signs of decomposition but instead, as Vasari recounts, as being untouched in ever y par t and without any bad odour, so that he seemed just ‘ to be quietly sleeping’. For them too, such a faith would sustain their conviction that he had tr uly been ‘the greatest man their ar t had ever known,’ just as a belief in his genius would inspire the ways his achievements would be looked upon by all his ver y many devotees and enthusiasts thereafter.

G I O RG I O VA S A R I

WHILE industrious and choice spirits, aided by the light af forded by Giotto and his follower s, strove to show the world the

t a l e n t w i t h w h i c h t h e i r h a p py s t a r s a n d w e l lbalanced humour s had endowed them, and endeavoured to attain to the height of knowledge by imitating the g reatness of nature in all things, the g reat Ruler of Heaven looked down and seeing these vain and fruitless ef forts and the presumptuous opinion of man, more removed from truth than light from darkness, resolved, in order to rid him of these er ror s, to send to earth a genius univer sal in each art, to show sing le-handed the perfection of line and shadow, and who should give relief to his paintings, show a sound judgment in sculpture, and in architecture should render habitations convenient, safe, healthy, pleasant, in proportion, and enriched with various or naments. He further endowed him with true moral philosophy and a sweet poetic spirit, so that the world should marvel at the singular eminence of his life and works and all his actions, seeming rather divine than earthly.

In the arts of painting, sculpture, and architecture the Tuscans have always been among the best,

Opposite: The Delphic Sibyl, from the Sistine Ceiling, 1509-12

and F lorence was the city in Italy most worthy to be the birthplace of such a citizen to crown her perfections. T hus in 1474 the true and noble wife of Ludovico di Lionardo Buonar roti, said to be of the ancient and noble family of the counts of Canossa, g ave birth to a son at Casentino, under a lucky star. T he son was bor n on Sunday, March 6, at eight in the evening, and was called Michelagnolo, as being of a divine nature, for Mercur y and Venus were in the house of Jove at his nativity, showing that his works of art would be stupendous. Ludovico at the time was podestà at Chiusi and Caprese near the Sasso della Ver nia, where St Francis received the stigmata, in the diocese of Arezzo. On laying down his of fice Ludovico retur ned to F lorence, to the villa of Settignano, three miles from the city, where he had a property inherited from his ancestor s, a place full of rocks and quar ries of sandstone which are constantly worked by stone-cutter s and sculptor s who are mostly natives. T here Michelagnolo was put to nur se with a stone-cutter’s wife. T hus he once said jesting ly to Vasari: ‘What good I have comes from the pure air of your native Arezzo, and also because I sucked in chisels and hammer s with my nur se ’ s milk.’ In time Ludovico had several children, and not being well of f, he put them in the arts of wool and silk.

When Michelagnolo had g rown a little older, he was placed with Maestro Francesco da Urbino to school. But he devoted all the time he could to drawing secretly, for which his father and senior s scolded and sometimes beat him, thinking that such things were base and unworthy of their noble house.

About this time Michelagnolo made friends with Francesco Granacci, who though quite young had placed himself with Domenico del Ghirlandaio t o l e a r n p

i

agnolo’s aptitude for design, and supplied him daily with drawings of Ghirlandaio, then re puted to be one of the best master s not only in F lorence but t h ro u g h o u t I t a l y.

increased daily, and Ludovico perceiving that he could not prevent the boy from studying design, resolved to derive some profit from it, and by the

Ghirlandaio that he might lear n the profession. At that time Michelagnolo was fourteen year s old. As the author* of his life, written after 1550 when I fir st published this work, has stated that some through not knowing him have omitted things worthy of note and stated other s that are not true, and in particular

*Ascanio Condivi

he taxes Domenico with envy, saying that he never assisted Michelagnolo, this is clearly false, as may be seen by a writing in the hand of Ludovico written in the books of Domenico now in the possession of his heir s. It runs thus:

1488. Know this 1 A pril that I, Ludovico di

Tommaso di Cur rado for the next three year s, with the following ag reements; that the said Michelagnolo shall remain with them that time to lear n to paint and practise that art and shall do what they bid him, and they shall give him 24 f lorins in the three year s, 6 in the fir st, 8 in the second and 10 in the third, in all 96 lire.

Below this Ludovico has written:

Michelagnolo has received 2 gold f lorins this 16 A pril, and I, Ludovico di Lionardo, his father, have received 12 lire 12 soldi.

I have copied them from the book to show that I have written the truth, and I do not think that any

Opposite: An old man wearing a hat (The Philosopher), c. 1495-1500, showing the influence of Ghirlandaio. For verso of this sheet see p. 42

one has been a g reater and more faithful friend to him than I, or can show a larger number of autog raph letter s. I have made this dig ression in the interests of truth, and let this suf fice for the rest of the Life. We will now retur n to the stor y.

M i c h e l a g n o l o ’ s p

s s a m a

d D

m e n i c o when he saw him doing things beyond a boy, for he seemed likely not only to sur pass the other pupils, of whom there were a g reat number, but would also frequently equal the master’s own works. One of the youths happened one day to have made a pen sketch of draped women by his master. Michelagnolo took the sheet, and with a thicker pen made a new outline for one of the women, re presenting her as she should be and making her perfect. T he dif ference between the two styles is as marvellous as the audacity of the youth whose good judgment led him to cor rect his master. T he sheet is now in my possession, treasured as a relic. I had it from Granacci with other s of Michelagnolo, to place in the Book of D e s i g n s. * I n 1 5 5 0 , wh e n G i o rg i o s h owe d i t t o M

* Vasari’s collection of drawings. This sheet is lost.

Opposite: Head of a Youth and a right hand, c. 1508-10. These studies similar to those made for the ignudi on the Sistine ceiling, are on the verso of the earlier drawing of the Philosopher (p. 41)

The central section of the Sistine Ceiling, 1509-12

p. 1 Caricatures, detail, British Museum, London

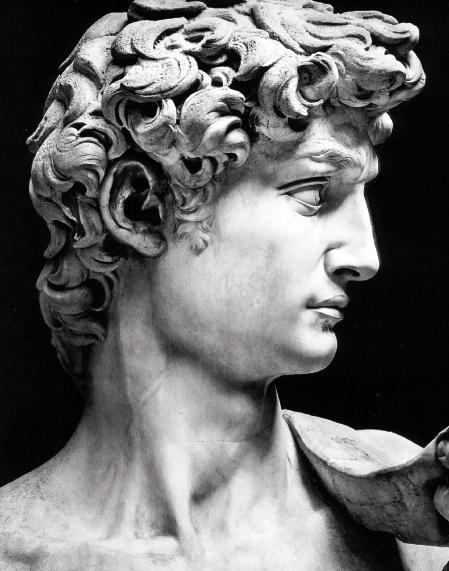

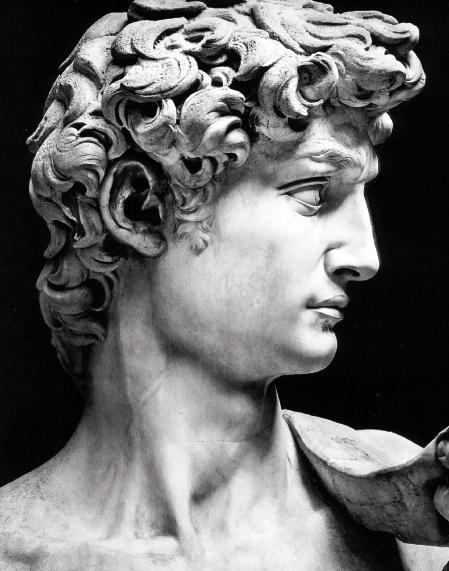

p. 2 David, 1501-4, 517 cm, Accademia, Florence

p. 4 Detail from the Last Judgment, 1536-41, Vatican

p. 6 Crucifixion , c. 1555-64, 41 x 27 cm, British Museum, London

p 13 ‘A battle scene, c 1504, 17 x 25, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

p. 14 The Fall of Phæton, 1533, 31 x 21 cm, British Museum, London

p. 18 The Entombment, c. 1501-02, 162 x 150 cm, National Gallery, London

p. 20 Christ at the Column, 1516, 15 x 14 cm, British Museum, London

p. 23 Angels from the Last Judgment, 1536-41, Vatican Museums

p. 27-28 Recto and verso: Studies for dome of St. Peter’s and figure studies,

39 x 23 cm, Teylers Museum, Haarlem, Nederland

p. 31-32 Recto: Male head and limbs; Verso: God and angels, c. 1511, 29 x 19 cm, Teylers Museum, Haarlem, Nederland

p 35 Introductory print from 1568 edition of Vasari’s Lives p. 36 The Delphic Sybil, from the Sistine Ceiling 1509-12

pp. 41-42 Recto: Old man wearing a hat, c. 1495-1500; Verso: Head of a Youth and a right hand, c. 1508-10, 33 x 21 cm, British Museum, London

p. 47 Man in profile, c. 1500-5, 13 x 13 cm, British Museum, London

p. 53 Bacchus, 1496-98, 203 cm, Museo del Bargello, Florence

p. 57 The Pietà, 1501, 174 x 195 cm, St Peter’s p 60 David, 1501-4, 517 cm, Accademia, Florence

p. 62 Virgin and Child with St John (‘Taddei Tondo’), 1504-05, diameter 107 cm, Royal Academy, London

p. 65 Virgin and Child with St Joseph, (‘Doni Tondo’), 1503-04, diameter 120 cm, Uffizi, Florence

p. 67 Study for a bathing warrior, c. 1504-5, 42 x 28 cm, British Museum, London

p. 71 The Rebellious Slave, c. 1513, 215 cm, Louvre, Paris

p. 72 The Dying Slave, c. 1513, 215 cm, Louvre, Paris

p. 75 Fratelli Alinari, Moise by Michael Angelo, central sculpture of the Tomb of Julius II, 57 × 42 cm, J Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

p. 84 Study for the Libyan Sibyl, c. 1510, 28 x 21 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

p. 88 Ignudo, head of Jeremiah, and feet of God from the Sistine Ceiling, 1509-12

pp. 90-91 The central section of the Sistine Ceiling, 1509-12, Vatican

p. 92 Seated Young Male Nude and Two Arm Studies (recto), c. 1510-11, 27 X 19 cm, Albertina, Vienna

pp 94-95 The Creation of Adam from the Sistine Ceiling , 1509-12, Vatican

p. 97 The Creation of Eve from the Sistine Ceiling, c. 1509-12, Vatican

p. 98 The Cumaean Sibyl from the Sistine Ceiling, c. 1509-12, Vatican

p. 101 The Prophet Isaiah from the Sistine Ceiling, c. 1509-12, Vatican

p. 102 The Libyan Sibyl from the Sistine Ceiling, c. 1509-12, Vatican

pp. 104-05 Judith and Holofernes from the Sistine Ceiling, c. 1509-12, Vatican

p. 107 Haman, 1511-12, 40 x 20 cm, British Museum, London

p. 108 Jonah, from the Sistine Ceiling, 1509-12, Vatican

p. 119 Tomb of Giuliano de’ Medici, with Night and of Day, 1519-33, Basilica of San Lorenzo, Florence

pp. 121-22 Recto: Studies for Night; Verso: Study for Day, c. 1524-5, 25 x 33 cm, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

pp. 128-29 The Holy Family with St John the Baptist, c. 1530, 27 x 39 cm, J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles

p. 135 The Julius Tomb, S. Pietro in Vincoli, Rome

p. 138 The Last Judgment, 1536-41, Vatican

pp 141-42 Recto and Verso: Studies of angels, c 1534-36, 40 x 27 cm, British Museum, London

pp. 146-47 Detail from the Last Judgment, 1536-41, Vatican

p. 151 Lamentation, c. 1530-35, 28 x 26 cm, British Museum, London

p. 158 Study for a window , 1547-49, 41 x 27 cm, Ashmolean Museum

p. 181 The Florence Pietà, 226 cm, 1547-55, Museo dell’Opera del Duomo, Florence

p. 188 Wooden model of the dome of St Peter’s by Michelangelo and assistants, 1558-61, and with later additions, 500 X 400 X 200 cm, Vatican Museums

p. 202 Engraving after model of S. Giovanni Fiorentino, 17th century p. 253 Portrait medal of Michelangelo by Leone Leoni, lead, 1560, 5.97 cm, British Museum, London

Illustrations on pp. 1, 6, 14, 20, 41-42, 47, 67, 107, 141-142, 151 and 253 courtesy British Museum; on p. 2 courtesy Pinacoteca di Brera; on pp. 4, 18, 23, 53, 62, 71, 72, 92, 108, 138 and 146-47 courtesy Wikimedia Commons; on pp 13, 121-22 and 158 courtesy Ashmolean Museum; on pp. 27-28 and 31-32 courtesy Teylers Museum; on pp. 36, 60, 88, 94-95, 98, 101, 102 and 104-05 © Jörg Bittner Unna; on p. 57 © Stanislav Traykov; on p. 65 © Livioandronico2013; on pp. 75, 119 and 128-129 courtesy J. Paul Getty Museum; on p. 84 courtesy The Metropolitan Museum of Art; on pp. 90-91, 97, 135 and 188 © Bridgeman Art Library; on p. 181 © Sailko