Falk

Jaeger

Falk

Jaeger

Fumihiko Maki and the Museum Reinhard Ernst

10 Christoph Zuschlag

Profile and perspectives of the Reinhard Ernst Collection

12 Oliver Kornhoff

Here to stay

14 A star without airs

The life and work of Fumihiko Maki, doyen of Japanese architecture

16 Do you love abstract art? Questions to Fumihiko Maki

20 A site with history

Wiesbaden donates its prime real estate to mre

23 Urban planning, the collection, and the audience

The architectural concept underlying the new building

24 Serving the purpose instead of itself

Fumihiko Maki’s architecture for a collection of abstract art

28 Sun and shade

Spatial inventions of Japanese architecture in the changing light of day

30 Oliver Kornhoff

The marriage of architecture and art

35 Precision and sustainability The schneider+schumacher architecture practice

36 Music and art for a better future The Reinhard & Sonja Ernst Foundation

39 Timeline

41 The construction process

Cross-sections and floor plans

Do you love abstract art?

Generally speaking, yes – but of course, it depends on the artist and the particular painting. The development of abstract art occurred right alongside my own career, so I have followed its trajectory and am familiar with many of the artists in Mr. Ernst’s collection.

What are the correlations between abstract art and architecture? How do you see the relationship between abstract art and expressionist, modern, or postmodern architecture? Where do you see the most equivalents?

I haven’t really thought too much about these correlations. Architecture has to serve so many functions – for the visitor, for the client, for the city – whereas art is more free; it can be experienced or not experienced, depending almost entirely on the individual will. You do not have to go

into the building to see the paintings if you don’t want to, but the building itself will still exist in the city and affect your life. So art and architecture are very different things, and difficult to correlate for me.

In your opinion, how important is the architecture of an art museum with regard to the exhibits? Should it withdraw as much as possible (“white cube” principle)? Or should it develop an autonomous formal intrinsic value?

In developing this museum, it was my intention to create a “world of art”, albeit within a limited site and building. It was important that the visitor experience be enjoyable above all else – this was clear from my conversations with Mr. Ernst. Whatever intrinsic formal values developed are intended

to serve this purpose, rather than existing for their own sake. And the containers for art are, as far as possible, open white spaces where the art itself takes center stage.

In many cases, we have designed museums where we weren’t very familiar with the exhibition content. In Wiesbaden, we knew the collection well from the start, but it is still evolving. Because of that, we thought the galleries should not be too specific. The collection is larger than the museum, so paintings will be rotating in and out of galleries, and the curatorial input is not yet available. So, overall, an abstract, white-cube approach seemed the most appropriate.

What role does natural light play throughout the museum and especially in the exhibition spaces?

We are always enthusiastic to have natural light throughout museums and even in exhibition spaces. This is always tempered by the opinion of the curators, and the need for stricter and stricter regulation of light and temperature to protect the art. The balance struck here is to make the public spaces very open to a sheltered central courtyard, and then introduce “borrowed” light to exhibition spaces via openings to the public spaces (rather than openings directly to the outside). This allows some indirect natural light to enter galleries and creates diagonal views through and across the museum, which Reinhard wanted. A few north-facing openings directly to the exterior were also allowed.

While two of the special exhibition rooms include skylights, most of the gallery ceilings are sealed. Natural light is introduced horizontally and is intended to brighten the spaces rather than the art. The art relies mostly on LED lighting for proper display.

Forced tour or matrix – which organization of the exhibition area do you prefer?

My preference is for a matrix. However, it is good if this matrix has enough clarity so that visitors can create their own route – one that ensures all exhibits are seen. That was our intention in Wiesbaden.

How do you react to the arrangement of the structures in the environment around the building?

As the site is located at the edge of the city center (with its larger institutions) and a more residential area (with individual

Early scheme showing subdivision of the building volume into rooms with different connections to the outside: access zones (dark gray), open atrium (green-gray), rooms with an outside connection (red), and closed hall (blue-gray).

villa-type homes), the museum massing tries to reflect both scales. It starts as a single large volume that preserves the streetlines along Rheinstrasse and Wilhelmstrasse. This volume is then internally articulated to reflect the purpose and respond to the surrounding buildings that are smaller in scale.

You design bigger complexes mostly as a composition of cubes with changing directions and angles. Why did you return to the orthogonal arrangement of the cubes in Wiesbaden?

Because the site of the building is limited, and its context largely orthogonal, it made sense to work within this orthogonal vocabulary as well. Also, as the art collection itself is graphically energetic, we thought it better if the building recedes somewhat, remaining more neutral and formally restrained.

Is your design in the “International Style”, or is there something “Japanese” about your creation for Wiesbaden?

My design is neither purposefully international nor Japanese. Like any building, it is the result of many complex factors. Perhaps it is better for visitors themselves to judge whether it has Japanese influence or not. Certainly, the central courtyard garden is inspired by some traditional materials and ideas, but in other ways the connection is not intentional – though it could perhaps be interpreted that way.

You are not considered to be an architect with a recognizable individual style, but rather you take a new formal approach to every single project. That means a client cannot just order “a Maki” from you, which would have a brand character. Is the individual “handwriting” of the architect not as important as that of the poet or composer?

Every client, context, and development is different, so it seems natural to me that – if one takes these demands seriously –different buildings in different locations and satisfying different needs would not look alike, even if they are by the same architect. At the same time, there are certainly themes that permeate my work, though perhaps they’re not evident at first glance. I work to avoid iconic, overly personal, and highly expressive architecture, choosing instead to focus my energy on developing rich and humane spaces that inspire visitors. I hope that this spatial richness transcends trends and icons and gives my buildings a broader cultural meaning. This is far more important to me than the development of an architectural “brand.”

2016

Proposal for construction of a museum presented to the City of Wiesbaden

2016 07/14 Public par ticipation procedure for use of the site

2017 03/17 Resolution of acceptance by the city council

2017 12/22

Leasehold agreement with the City of Wiesbaden for 99 years

Planning contract awarded to the architect Fumihiko Maki

2018 Building permit

2019 08/30 Laying of the foundation stone

2021 Completion of the shell construction

Installation of the artwork

Pair by Tony Cragg

2022 Start of interior fit-out

Installation of the artworks

Buscando la luz III by Eduardo Chillida

Kraken-Migof by Bernard Schultze

2023

Installation of the artworks

Ein Glas Wasser, bitte by Katharina Grosse

Vertical Highway by Bettina Pousttchi

Wandering Thoughts by MadC

2024 06/23 Opening

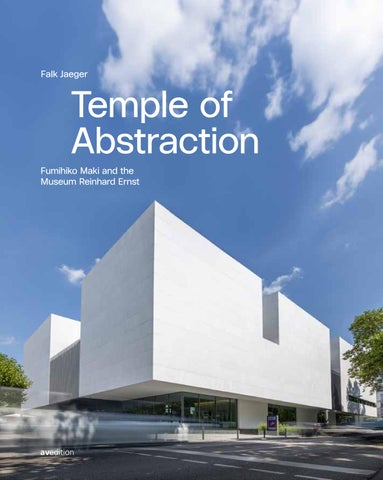

Patron Reinhard Ernst plans a home for his unique collection of abstract art, the City of Wiesbaden provides the site in the heart of the city, and Japanese star architect Fumihiko Maki supplies the plans. The Museum Reinhard Ernst is the final masterpiece by the Pritzker Prize winner and was opened just a few days after his death. The result is an architectural gem, but also a lowthreshold space that welcomes the general public and offers an attraction for international art-lovers.

This richly illustrated book presents the “Temple of Abstraction” with all its architectural aspects and portrays it as an example of a contemporary museum.

The author, Prof. Dr. Falk Jaeger, is a building historian, architecture critic, and publicist living in Berlin. He writes for major daily newspapers and specialist media and has published more than 40 books on architecture, urban planning, and monument preservation.