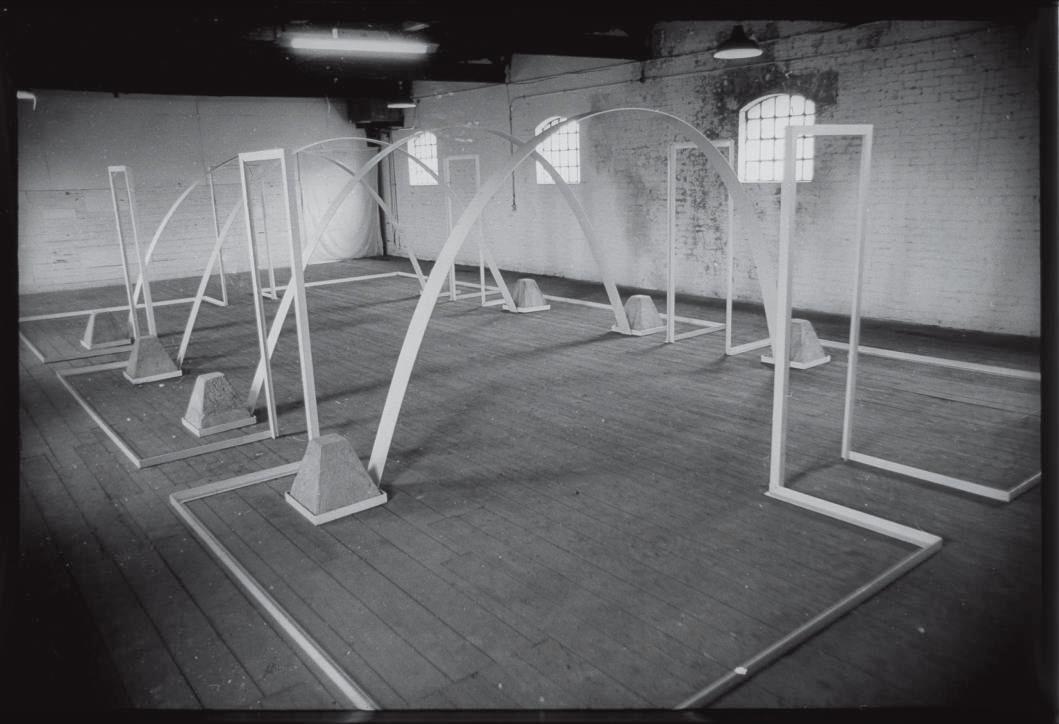

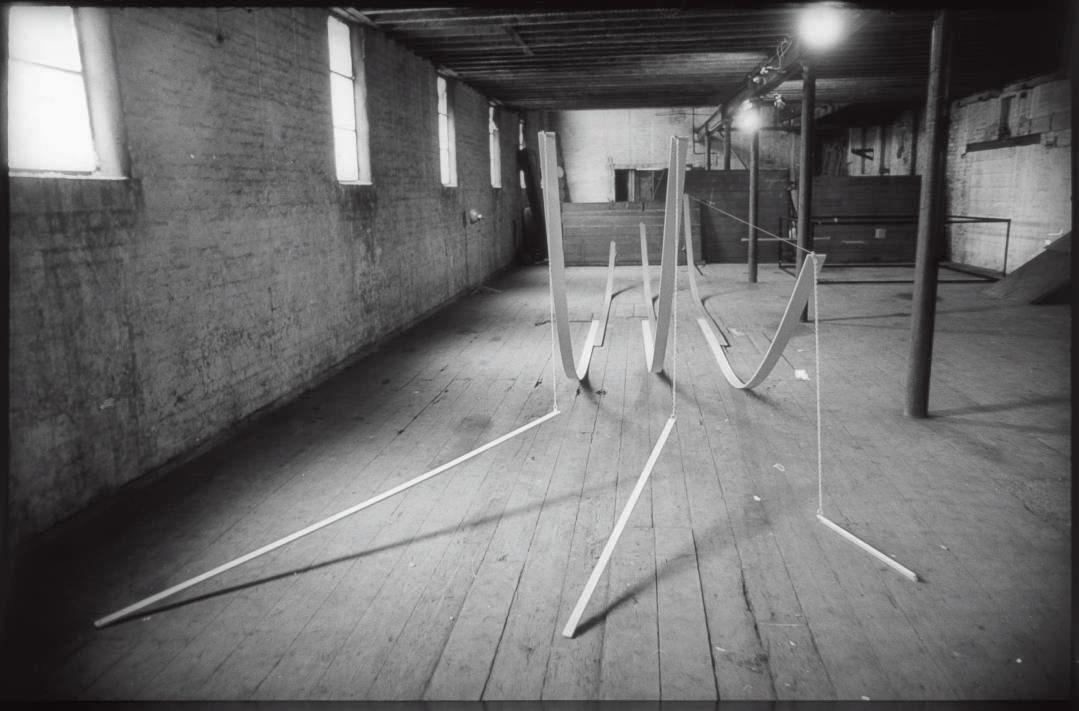

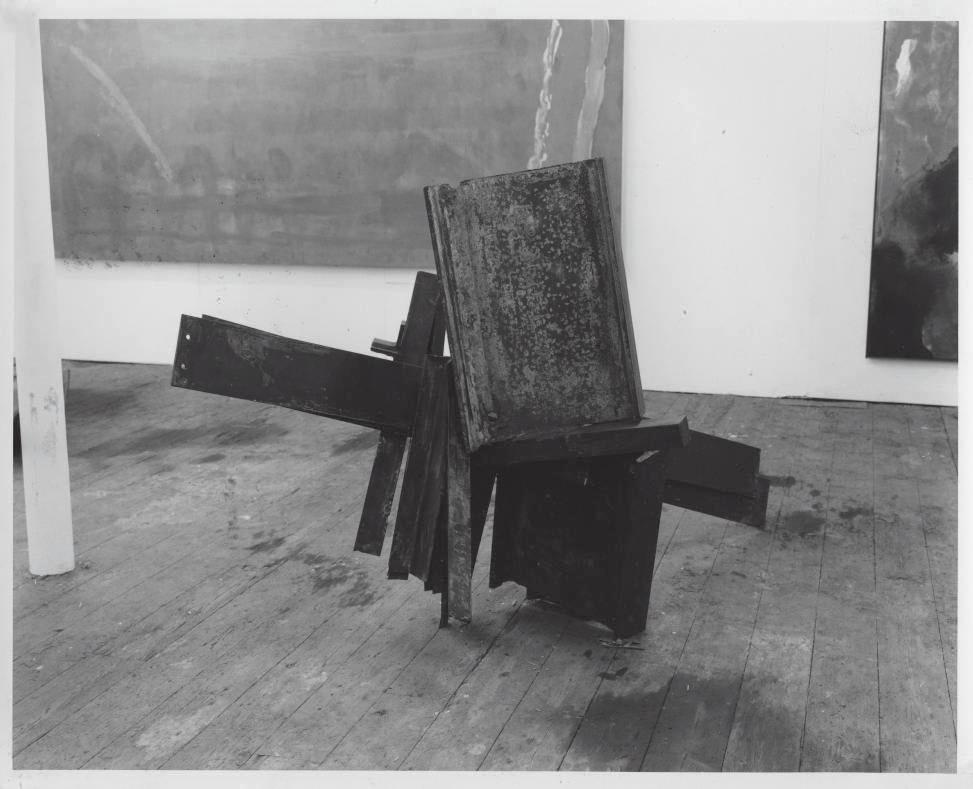

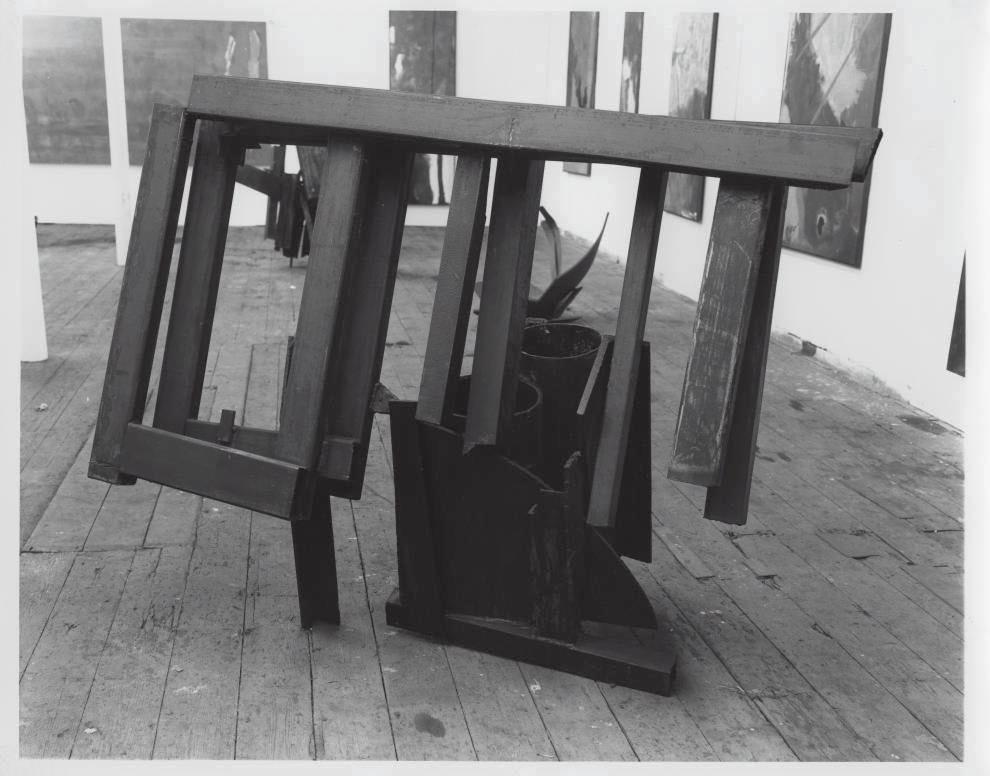

Installation view, Stockwell Depot: Sculpture Exhibition, Stockwell Depot, London, 1968 with Peter Hide, Sculpture Number 2 (1968)

Installation view, Stockwell Depot: Sculpture Exhibition, Stockwell Depot, London, 1968 with Peter Hide, Sculpture Number 2 (1968)

Beyond the End of Modern Sculpture: Stockwell Depot 1967–79

Sam CornishIn the summer of 1967, the Stockwell Depot, a former brewery in south London, was converted into studio space by a group of young artists, almost all of them sculptors associated with St Martin’s School of Art, London. In May 1968 they held their first studio exhibition. These exhibitions became known as the ‘Stockwell Depot Annuals’ – continuing until 1979 – and the studios were occupied until the early 1990s. The Depot stands at the very beginning of the rapidly growing phenomenon of artists grouping together to use London’s large stock of abandoned buildings as studio space. What distinguished the Stockwell studios from the similarly large, gloomy and draughty brick and steel spaces that followed – warehouses, schools, dock buildings and churches – was its sense of purpose, its dedication to the communal project of modernist abstraction. The Depot’s annual exhibitions began at a moment when the assumptions of high modernism were being widely disputed; continuing through a period when many artists and critics thought these assumptions had passed into irrelevance. At the Depot, a succession of young artists were working in and against a changing tide, making art in a ‘bleak’, ‘forbidding’ building that provided the setting for an especially late modernism to play itself out.

The Depot was primarily a sculpture studio. Painters worked there throughout its existence, but even when painting became an important part of the Depot exhibitions, those artists involved did not – for the most part – have studios there. Close connections to St Martin’s also meant that it was in relation to sculpture that the Depot’s contribution was most coherent, complex and ambitious. The sculpture made at Stockwell should be understood in relation to the attitudes that had coalesced at St Martin’s during the 1960s. During that decade, the department had established an international reputation as a radical centre for modern sculpture, led by Anthony Caro and the diverse group of sculptors who studied and taught there, now known as the New Generation after an exhibition at the Whitechapel Art Gallery, London, in 1965.1 Often brightly coloured, in steel or fibreglass, the abstract sculpture produced in and around St Martin’s in the 1960s is a key episode in the history of modernism in Britain. Until at least the early 1980s, work in the department was sustained by a belief that it was the place from where the present

and the future of sculpture would spring. Grasping this sense of importance – of acting on a world stage, and of acting to further not just individual careers, but the future of the discipline – is crucial to understanding sculpture at Stockwell.

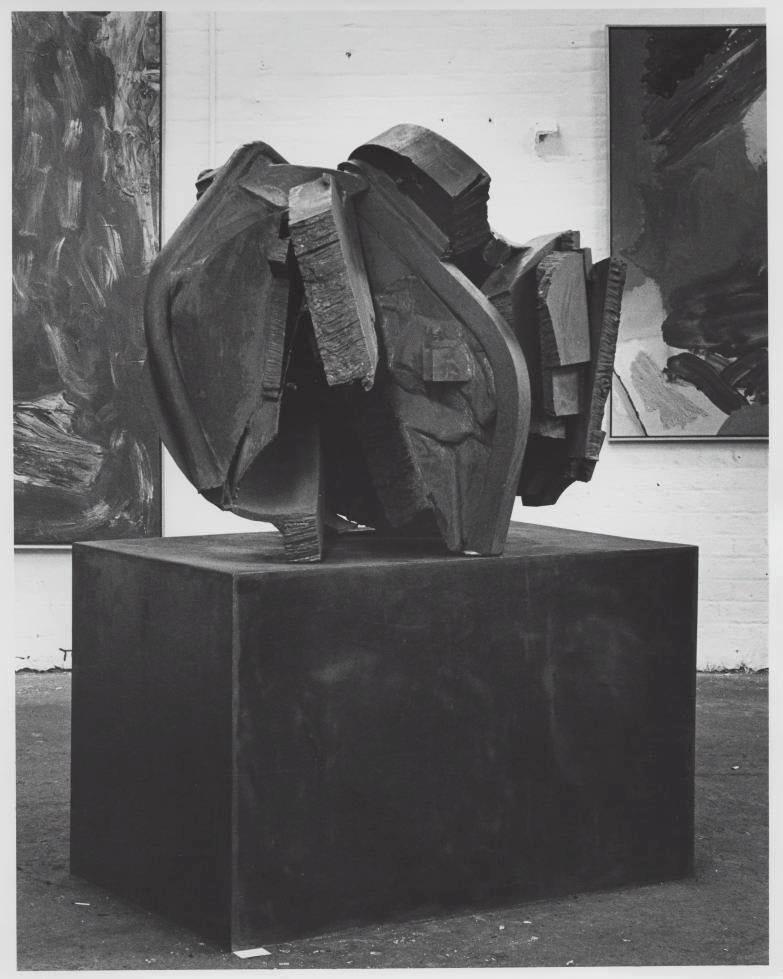

Toward the end of the 1960s, diverse winds of change – from Minimalism and Arte Povera, through to what became known as the ‘expanded field’ – blew through modernist attitudes and aesthetics. In the Depot’s first few years, the spatial extension, succinct and ambiguous objects and colour of New Generation sculpture existed alongside – or sometimes merged with – more self-consciously radical approaches; great importance was placed on a sculpture’s interaction with its environment, and new levels of visual severity or reduction were reached. From around 1972 or 1973, sculptors at the Depot began to question the achievements of the New Generation, not because their definition of sculpture had been too restrictive, but because it was too permissive and invaded by disciplines – primarily painting – which were not considered ‘proper to sculpture’.2 The increasingly heavy steel sculpture that developed, which was widely known as Stockwell Sculpture, attained some prestige and limited institutional backing in the 1970s, and then quickly disappeared from view. Even in its brief heyday, Stockwell Sculpture was widely disliked and misunderstood. It is a moment in recent British art history in need of reappraisal.

Not all of the sculptors at the Depot were involved in the tightly knit arguments about the nature of sculpture, which were essential to the development of Stockwell Sculpture: David Evison, in particular, worked an independent furrow. Stockwell Painting had its own narrative, bound up with changing attitudes to American painting stemming from Abstract Expressionism. An account of Stockwell is further complicated by the fact that not all the artists who showed at the annual Depot exhibitions had studios there, nor were all the artists who did have studios necessarily included. The Depot exhibitions were distinctly not open studios – as became popular in Wapping, Stepney or Butler’s Wharf – in which artists tidied up their own spaces and opened the doors to the public. By the mid-1970s the exhibitions were hung and selected by a self-appointed – if fairly informal – committee which was as concerned with putting across a particular attitude to painting and sculpture as it was in representing the art made at the Depot. This process may now

David Evison

Peter Hide

Studios at Stockwell Depot, London, 1971

David Evison

Peter Hide

Studios at Stockwell Depot, London, 1971

John Golding

Richard James

John Golding

Richard James

David Evison, Gerard Hemsworth, Roland Brener, Roelof Louw, Peter Hide, Roger Fagin and John Fowler, Stockwell Depot, London, 1968

David Evison, Gerard Hemsworth, Roland Brener, Roelof Louw, Peter Hide, Roger Fagin and John Fowler, Stockwell Depot, London, 1968