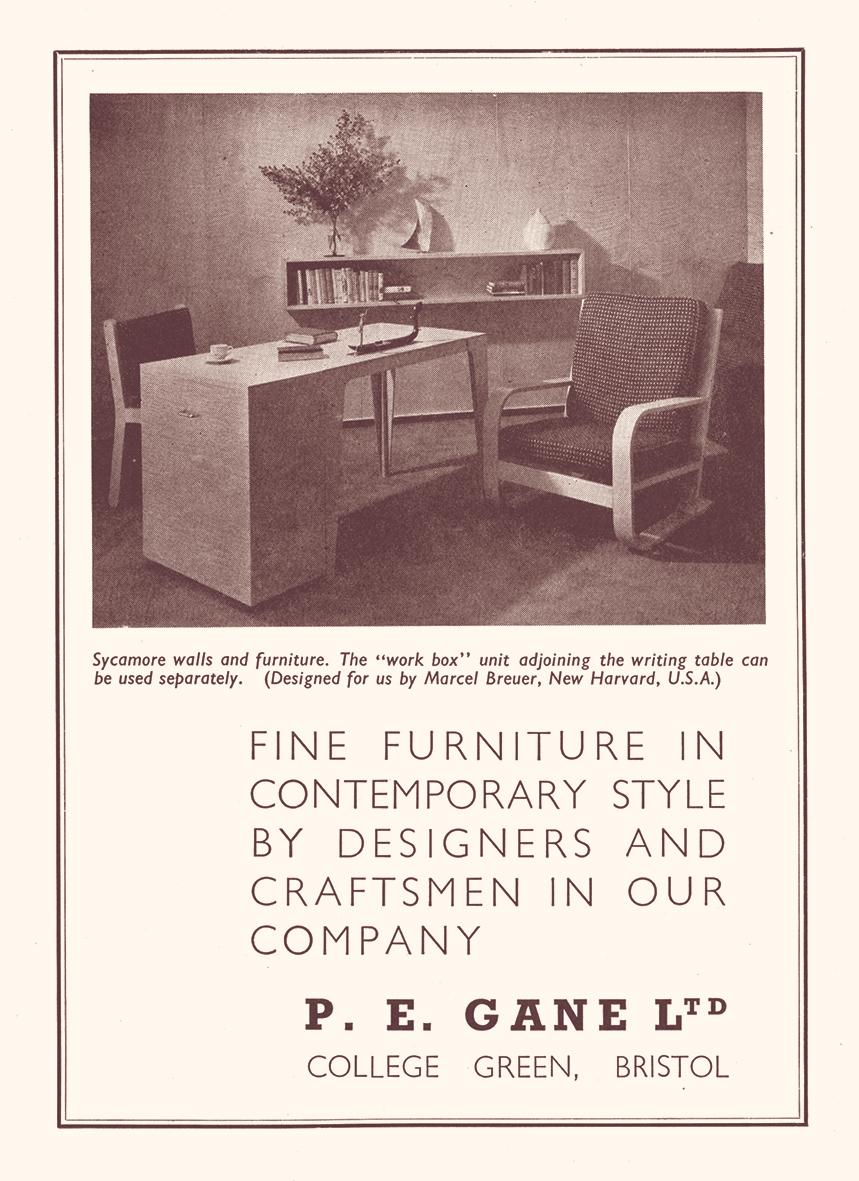

Gane’s press advertisement, mid-1930s.

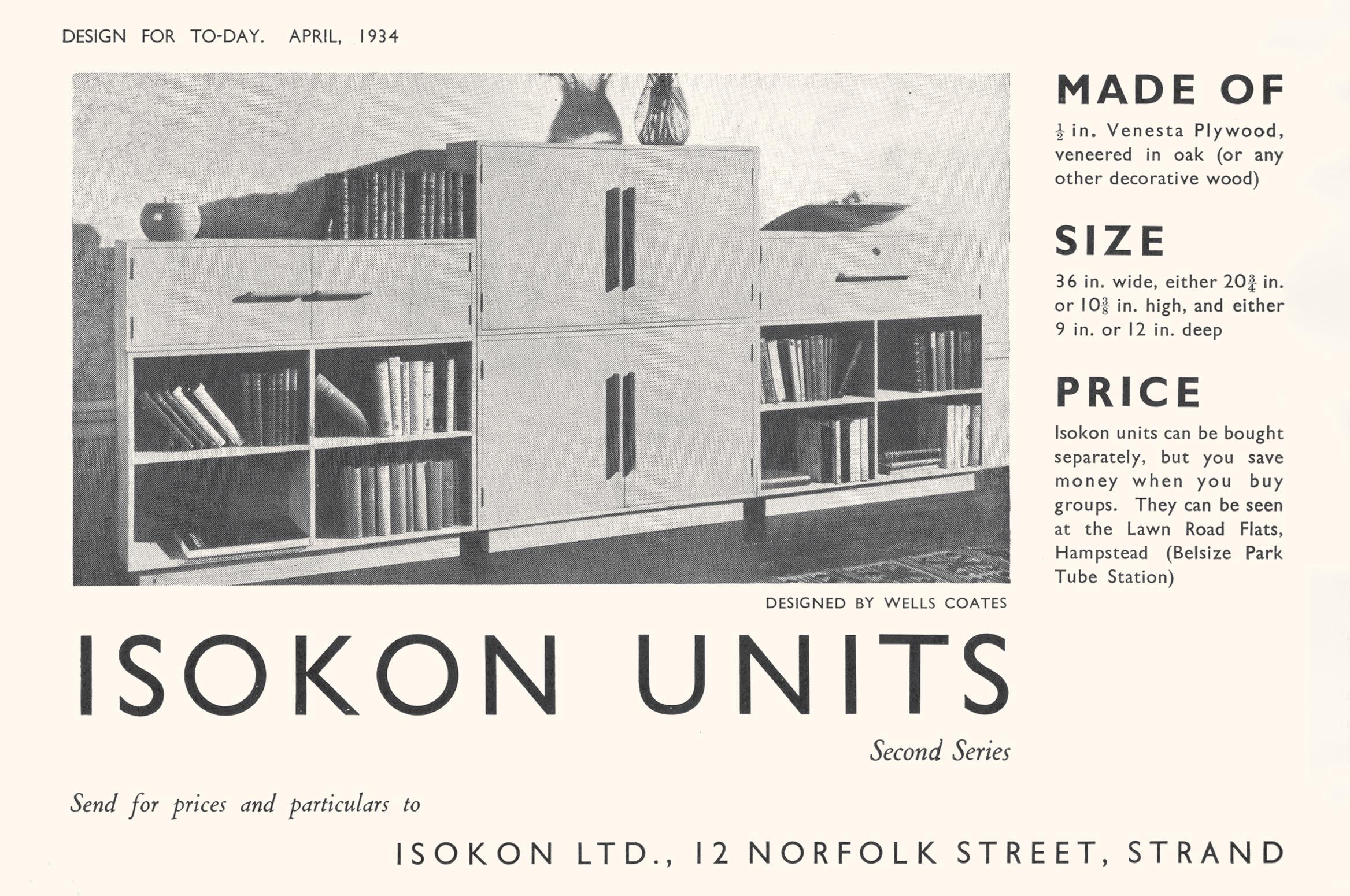

Crofton Gane had contacted Marcel Breuer soon after his arrival in England, and not only commissioned him to design furniture for Gane’s, but to work on interiors, and even design a show pavilion. And Crofton was to continue his commitment to modernism by employing the likes of Wells Coates. Crofton wrote with enthusiasm, ‘we, as craftsmen, are taking part in a new culture which is a spiritual adjustment to the age in which we live’.

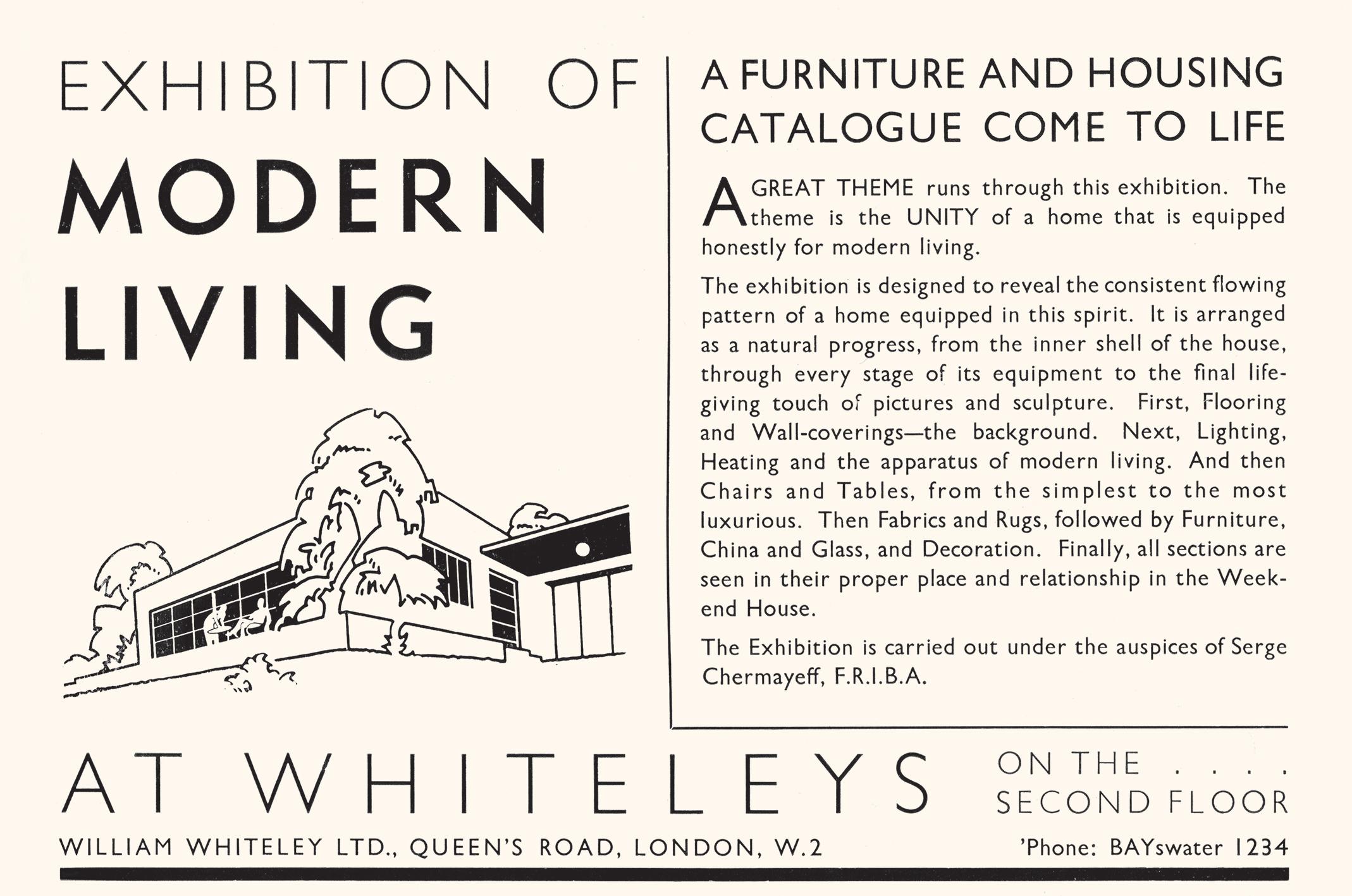

Geoffrey Dunn, himself a furniture designer (known to have done designs for Heal’s), became agent for Isokon, and, as soon as he could, was displaying the furniture designs of Alvar Aalto, Chermayeff, Gordon Russel, and Breuer, the textiles of the Donald Brothers and Edinburgh Weavers. Besides new generations of store owners ‘brushing clean’ in the 1930s, there were in-company personalities with like values working alongside, as H.G. Hayes Marshall, a trained textile designer head of furnishing at Fortnum & Mason, Harry Trethowan, a ceramicist, head of Heal’s pottery and glass department for over thirty years (virtually carrying Heal’s through the decade), J.P. Hully, Gane’s in-house designer, and the like. Ofttimes the actual store buildings proclaimed ‘contemporary’, as with Peter Jones, completed in 1936, and D.H. Evans in 1937. From their actual buildings to their shop windows and to their interior ‘special’ exhibitions, this handful of retailers were 1930s pioneers of modernism. Lee Longland was to show its stand

the left-winger, Lubetkin, was to design The Finsbury Health Centre, with, as he described it, ‘it’s curving façade and out-stretched arms’ welcoming a deprived community.

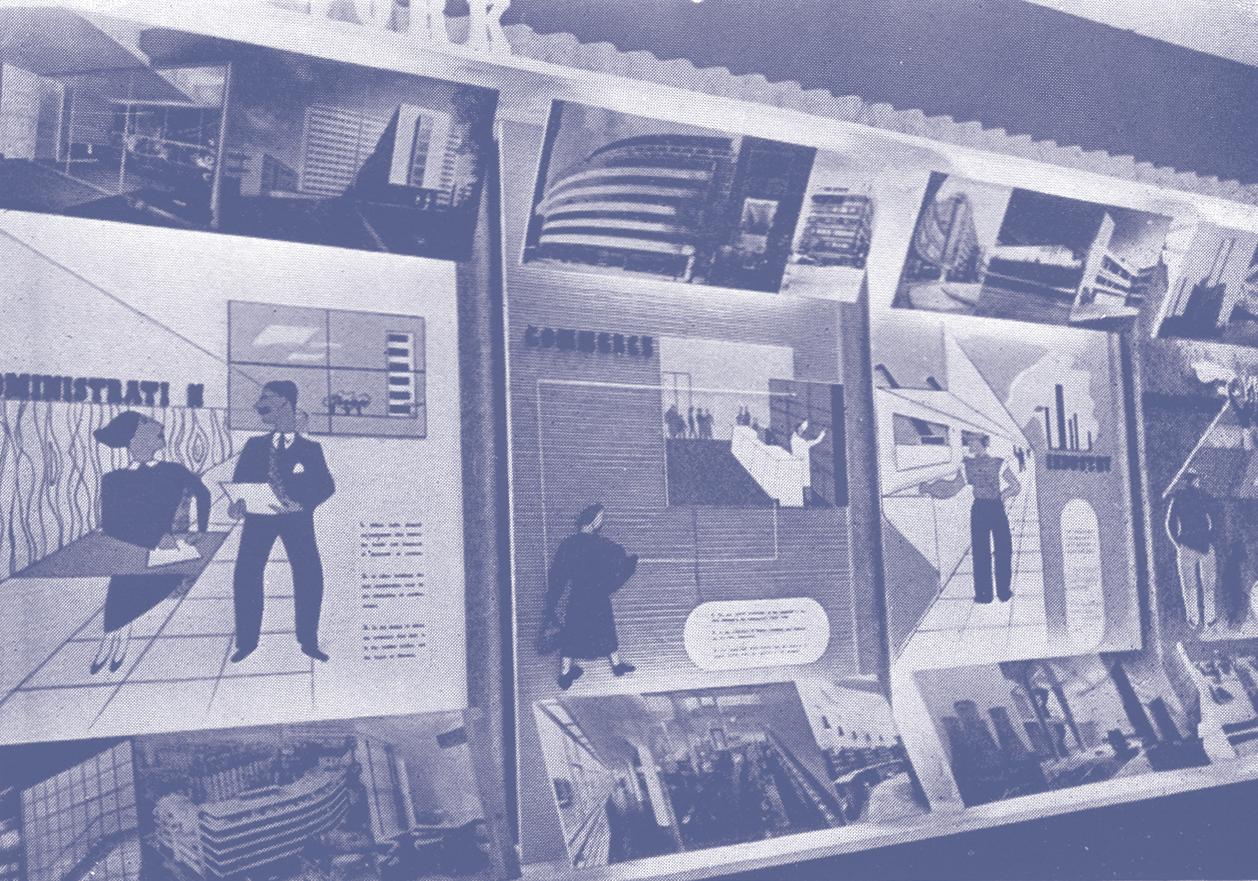

The Royal Institute of British Architecture can hardly be said to have given a lead when it came to modernism, albeit, it did mount an exhibition in 1934 (‘International Architecture 1924–34’) to inform both professionals and the public of what was afloat. It was left to a group of professionals to prove activists for modernism, when Wells Coates, Morton Shand, Maxwell Fry and F.R.S. Yorke founded MARS (The Modern Architectural Research Group), in 1933. Initially this was a rather select band of architects and architectural journalists, but eventually it expanded to some sixty members, all pushing modernist architecture within town planning. MARS is best remembered for mounting its iconic exhibition, ‘New Architecture, an exhibition of the Elements of Modern Architecture’ at the

and actually functioned as a restaurant, a mecca for the Hampstead cultured, including Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, Herbert Read, Nicklaus Pevsner and C.E.M. Joad, with a continuing waiting list for membership. Some of the flats served, initially, as a haven for refugees the Pritchards were helping, as Gropius, Breuer and MoholyNagy, but later were to be occupied by ‘personalities’ as the author Nicholas Monserrat and Philip Harben, the television cook.

But, as with so many idealistic schemes, all did not go smoothly. Jack and Molly liked to be hands-on, and Wells Coates was not the easiest work companion. The relationship was

prickly, not being helped by the need to find the necessary capital. Nevertheless, the building got much press coverage, Pevsner rating it ‘a milestone in the introduction of the modern movement in London’. It was later to be awarded a Grade I listing.

A London ‘white block’ to compete for attention, was Berthold Lubetkin’s High Point. Lubetkin, as the Pritchards, was a committed socialist, but not, as them, merely ‘intellectual ‘, but having the social good as core to his creative motivation. He saw the purpose of his profession, architecture, to be to:

improve by all means at the disposal of technique the living conditions of the people, and to create a language of architectural form which, by being firmly based on the aesthetics of our age, conveys the optimistic message of our time, the century of the common man.

His crusader banner carried the words ‘nothing is too good for ordinary people’!

Lubetkin, a Georgian by birth, studied first art and then architecture, variously across Europe (in Moscow, Berlin, Warsaw and Paris), before coming to England in 1931. He gathered round him a group of young graduates from the Architectural Association and formed the practice Tecton (a shortened form of the Greek ‘architect’ – master builder). Of this group Francis Skinner became his closest colleague and a partner when Tecton closed.

Maxwell Fry coordinated the exhibition, which consisted of rooms as well as individual pieces. Both Fry and Breuer furnished living rooms, O’Rorke a dining room, and so on. Fry and Breuer both had bent wood furniture on display, inevitably Breuer’s bentwood chaise longue proving the main attraction; and, indeed, he was said to have been the only one to have sold some of his designs as a result of the exhibition.

ISOKON

In the mid-1920s, a young Cambridge graduate, Jack Pritchard, unsure of what to do as a career, drifting in and out of jobs, got, in 1925, what may, at first glance, sound to have been a rather run-ofthe-mill position with a firm of plywood importers, Venesta Ltd. His rather ill-defined post – part selling, part publicity, part product development – was magically to harness and challenge the young graduates’ motivation and ingenuity.

Pritchard was already aware of Continental trends in design, and in no time got Corbusier’s practice to design an exhibition stand for Venesta. He, himself, began to experiment with plywood, and when he heard of Wells Coates’s work for the fashion chain Cresta, which involved the use of plywood, he met up with him. Together, with the likes of Raymond McGrath, Serge Chermayeff and

Advertisement for Isokon Units, designed by Wells Coates, 1934.

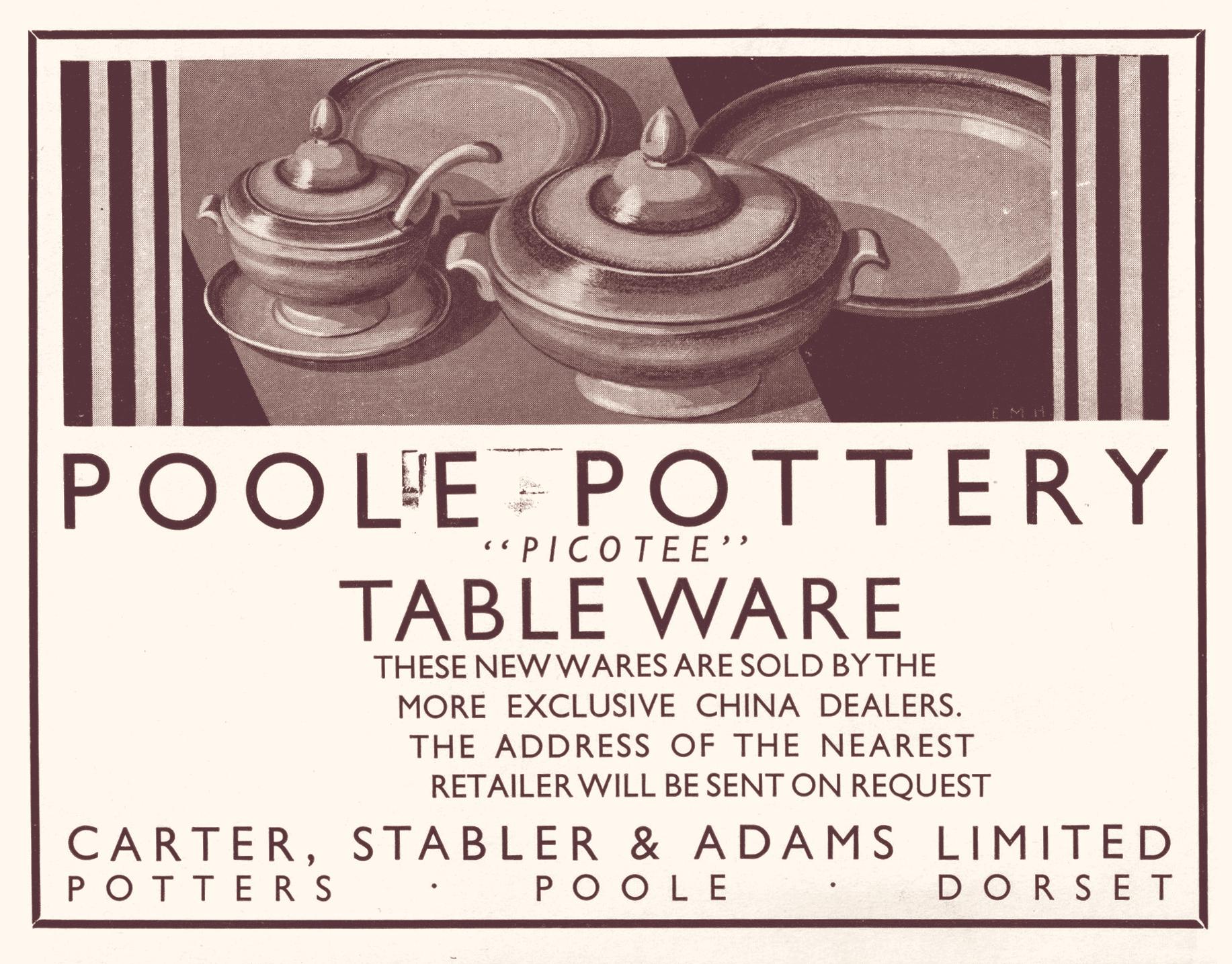

Carter, Stabler & Adams advertisement for Poole Pottery ‘Picotee’ tableware, 1933.

John Adams came from a family of ceramic manufacturers in Staffordshire and had been introduced to experimental glazing in the studio of Bernard Moore, before going from Hanley School of Art to the Royal College of Art in 1908. It was there he met his future wife, Gertrude Sharp (Truda). The pair worked for a time, before WWI, in South Africa, both teaching at the School of Art at Durban Technical College, John its Head.

Curiously it was Truda who was appointed Art Director of the new subsidiary, whereas John was left, presumably relieved to

relinquish administrative responsibilities, to experiment with glazes and shapes. Whereas Truda’s ceramics tended to be decorated with flowers, simplified, rather similar to those of Charlotte Rhead, John brought a strong modernism to the subsidiary – basic shapes, largely undecorated, at the very most with simple coloured bands. The Stablers, Harold and his wife Phoebe, also a potter, seem largely to have contributed decorative figures and birds, albeit there are examples of Harold occasionally designing plain tableware.

The 1930s was when Carter, Stabler & Adams was riding high, much aided by Stabler’s reputation and networking – beside his academic role he was a member of the Council for Art & Industry and on the selection committee for numerous design exhibitions. And it was ensured that the subsidiary’s image was reinforced by typography and display stands of equal modernity. Little seems to have changed by the Adam’s split and Truda’s marriage to Cyril, John working through to his retirement in 1950.

rugs and the odd shop window display and exhibition stand. But it was in the 1930s, when he was appointed consultant to the Bradford printers Lund Humphries that he gained the support and freedom not only to test his own skills, but to demonstrate his generosity to fellow designers who needed work.

Lund Humphries had taken a building in Bedford Square as its London sales office, Peter Gregory to direct the operation. Kauffer was provided with a studio in the basement along with the photographer Man Ray. The ground floor acted as a showroom and it was there that Kauffer was not only to show his own work, but to mount exhibitions for other graphic designers, as Hans Schleger, and typographers. Kauffer had been given the rather vague responsibility for the ‘look’ of the firm, and, in no time, he and his partner, Marion Dorn, were providing the building with modernist furnishings, and upgrading the company’s stationery. In 1935 he rewarded himself by mounting a one man show of his designs, extending across the whole of the ground floor, which led to enthusiastic support from the likes of Roger Fry, and to The Scotsman newspaper titling him ‘The Picasso of Design’. On seeing the exhibition Anthony Blunt wrote:

Mr. McKnight Kauffer is an artist who makes me resent the division of art into major and minor … as I looked round the exhibition of his work at Messrs. Lund Humphries galleries in Bedford Square I was led to think, ‘If he is minor, who then is major at any rate among his English contemporaries.’