Listening we will not automatically get to a better world, or a better philosophy. Sound does not hold a superior ethical position or reveal a promised land. But it will show us the world in its invisibility: in the unseen movements beneath its visual organization that allow us to see its mechanism, its dynamic and structure, and the investment of its agency, which might well be dark and forbidding. A sonic sensibility reveals the invisible mobility below the surface of a visual world and challenges its certain position, not to show a better place but to reveal what this world is made of, to question its singular actuality and to hear other possibilities that are probable too, but which, for reasons of ideology, power and coincidence do not take equal part in the production of knowledge, reality, value, and truth.1

This glass skylight located near the top of the vertical volume is designed to both capture or muffle the ambient sounds of the neighborhood. The resulting soft “sonic breeze” is appropriately located just above the sleeping area. In this location, the associated disc doubles as a satellite dish that is embedded in the south-facing section of the skylight. This captures the signals that allow occupants in the bedroom/den below to connect visually and aurally with the global media, through television and internet connections.

This sonic window facing the backyard is designed like a camera bellows. It includes a translucent glass dish that is fully integrated into the window wall with the ability to rotate freely in three dimensions. Again, the large windows regulate the ambient sounds while the rotating dish focuses on specific activities of the backyard: the birds at the feeder, the children playing in the sandbox, or the dog chewing on his bone.

The curved sliding section of the front sonic window allows residents to hear the ambient sounds of the streetscape. Here, the curved surface doubles as the front door. It can be operated to pick up and highlight the sounds of this locale: guests arriving at the house, the dog greeting the mailman, or the footsteps of the occasional jogger.

The two volumes of the house come together at the center kitchen island, which acts as the audiovisual nerve center of the home and functions as a central command station for operating the sonic windows. From this position the occupants can regulate the various audiovisual conditions associated with the three windows. Each sonic window has a corresponding video screen with regulation controls. The video screen visually records the location of the incoming focused sounds so that the occupants can both see and hear the specific audiovisual condition. This command center, designed into the waterproof kitchen countertop, encourages the occupants to mix these various sounds of their landscapes with other media inputs. For example, the voices of their children playing

3-6 Section through main volume of house showing acoustical connection between living and bedroom areas.

4-9 Group review of student architecture projects that incorporated sound, 2013. [Karen

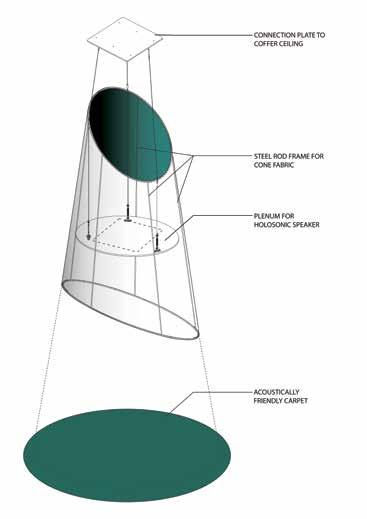

4-10 Faculty and student party offering multiple sound environments using the cones of Sound Lounge, 2013. [Ghazal

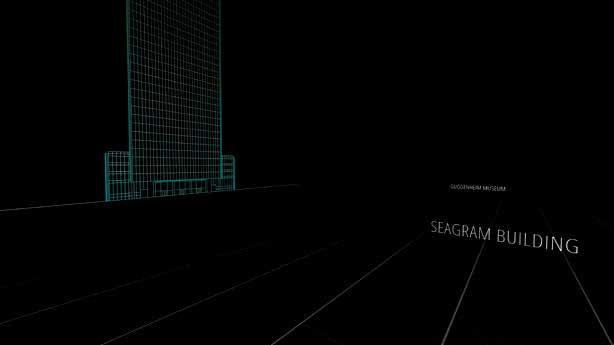

The Seagram Building is an icon of the International Style in architecture, completed in 1958. Designed by Mies van der Rohe for the Bronfman family, owners of the Seagram beverage empire, it stands directly opposite from the New York Racquet and Tennis Club, which was designed by the well-known neoclassical firm of McKim, Mead & White, and completed in 1918. The Seagram Building is as open and transparent as the Racquet and Tennis Club is closed. This 40-story steel frame building, with a tinted glass curtain wall facade, was designed to express a reductive architectural vocabulary with a refinement in details and proportions, distinguishing it as a prime example of the International Style. The building is set back 100 feet from the street by a set of long horizontal stairs that join a granite entry podium. The stairs are bordered by two large water features whose fountains have the effect of creating a sonic gateway to the building plaza and entryway; they mask the traffic sounds of Park Avenue and begin the processional entry into the transparent lobby space. The lobby is enclosed on three sides by full-height glass walls that meet the ceramic tile ceiling. The granite floors extend directly out to the plaza outside, expanding the visual impression of this interior. The banks of elevators on the lobby’s east side are sheathed in Roman travertine. The space is distinguished sonically by its proportions and highly reflective materials. The calling out of a name or the power-walking heels that penetrate the space are so distinctive and crisp that they may sometimes remind us of the racquet sports going on in the club across the street. These sounds are sharp, clear, and immediately reflective.

5-18 Digital street image of the Seagram Building, Soundscape Architecture, 2014. [Karen Van Lengen]

5-19 Photograph of the Seagram Building Lobby, New York City. [Karen Van Lengen]

5-20 Analytical diagram of the Seagram Building Lobby, showing volume, circulation, and materials, 2014. [Karen Van Lengen]

5-25 Drawings