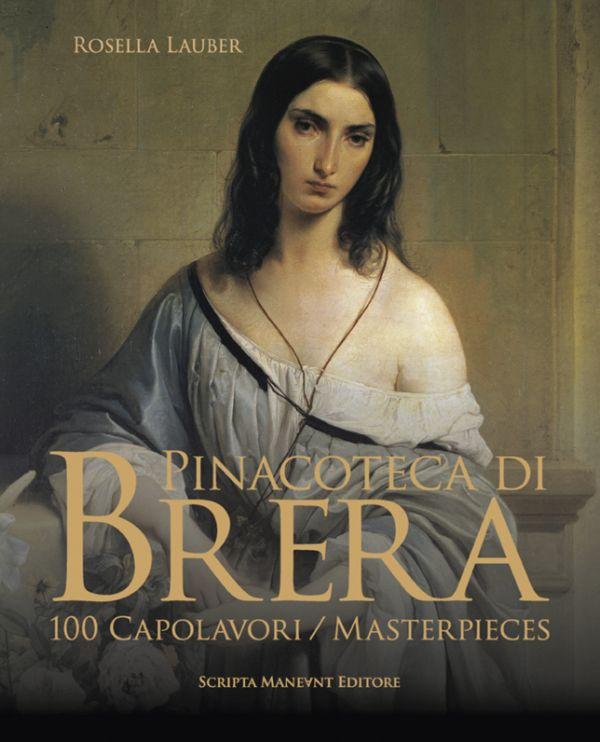

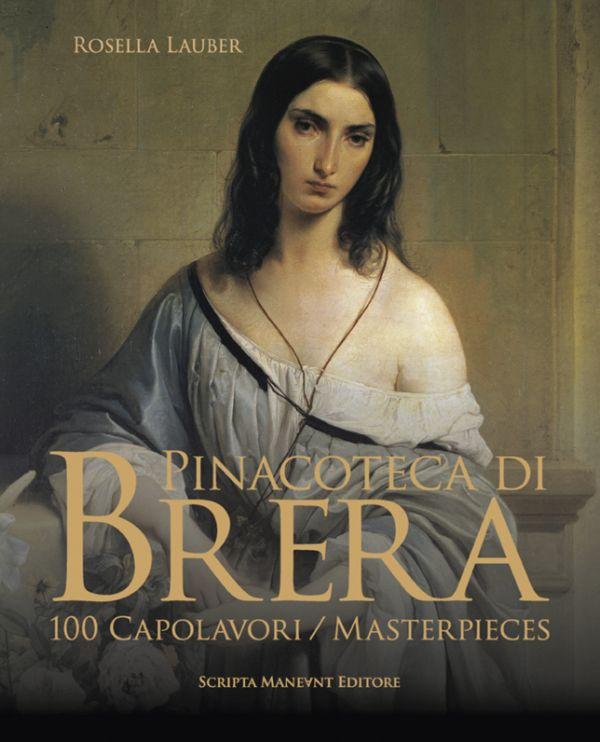

La Pinacoteca di Brera è un museo nazionale, nato nel 1776 come istituzione affiancata all’Accademia di Belle Arti, per volere dell’imperatrice asburgica Maria Teresa d’Austria. Le origini degli insediamenti braidensi risalgono però alla fine del XII secolo, quando la comunità degli Umiliati si trasferì in un territorio incolto (brayda), da cui la denominazione di Brera. Nella seconda metà del Cinquecento, tali possedimenti passarono alla Compagnia di Gesù, che decise di realizzarvi un collegio, ma a seguito dello scioglimento dell’ordine religioso nel 1773, il complesso di Brera divenne di proprietà statale. Sotto il governo austriaco, a Brera furono trasferite nuove istituzioni pubbliche come le Scuole Palatine, con docenti del calibro di Giuseppe Parini e Cesare Beccaria. In seguito all’incoronazione di Napoleone come re d’Italia nel 1805, la galleria braidense divenne fulcro della politica culturale dell’intero Regno Italico, di cui Milano era capitale, e attraverso acquisizioni importanti tra cui lo Sposalizio della Vergine di Raffaello, si impose come museo unico, capace di distinguersi da altre pinacoteche nazionali per il carattere universale delle sue raccolte, non rivolte a una singola scuola locale. Nel 1882 Brera venne riconosciuta come istituzione amministrativa autonoma dall’Accademia e la direzione fu affidata a Giuseppe Bertini che, con l’aiuto di Giovanni Morelli e Adolfo Venturi, si occupò della prima ricognizione dei depositi esterni nelle chiese milanesi.

A Corrado Ricci, invece, si deve il sistematico riordino della pinacoteca secondo il criterio delle scuole regionali, la curatela del primo catalogo del museo, l’istituzione della fototeca e un allestimento che ha fatto scuola nella storia della museografia: illuminazione zenitale e divulgazione dei dati più importanti delle opere attraverso l’introduzione dei cartellini museali. Ruolo fondamentale nella preservazione della collezione, minacciata dalle distruzioni della Seconda guerra mondiale, lo ebbe Fernanda Wittgens, prima direttrice della Pinacoteca di Brera, oltre che prima donna in Italia a ricoprire un ruolo dirigenziale in un’importante istituzione museale. Franco Russoli, padre della museologia moderna, ha traghettato il museo nel nuovo millennio, avvicinando Brera agli standard delle istituzioni internazionali. Fautore di un innovativo coinvolgimento del pubblico e del territorio, ha trasformato il museo in motore della vita pubblica cittadina. Il progetto di ampliamento del complesso museale, da lui fortemente voluto e promosso grazie all’acquisizione del vicino Palazzo Citterio, è stato recentemente rilanciato dalla direzione di James Bradburne. Gli ultimi decenni sono stati caratterizzati da mostre, restauri e donazioni, che hanno permesso a opere iconiche come la Fiu-

The Pinacoteca di Brera is a national museum, founded in 1776 as an institution alongside the Academy of Fine Arts, at the behest of the Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. However, the origins of the Braidense settlements date back to the end of the twelfth century, when the community of the Umiliati moved to uncultivated land (brayda), hence the name Brera. In the second half of the sixteenth century, these possessions passed to the Society of Jesus, which decided to build a college there, but following the dissolution of the religious order in 1773, the Brera complex became state property. Under Austrian rule, new public institutions such as the Scuole Palatine were moved to Brera, with teachers of the calibre of Giuseppe Parini and Cesare Beccaria.

Following Napoleon’s coronation as King of Italy in 1805, the Braidense gallery became the fulcrum of the cultural policy of the entire Kingdom of Italy, of which Milan was the capital, and through important acquisitions, including Raphael’s The Marriage of the Virgin, it established itself as a unique museum, able to distinguish itself from other national picture galleries by the universal character of its collections, which were not aimed at a single local school. In 1882, Brera was recognised as an autonomous administrative institution from the Academy and the direction was entrusted to Giuseppe Bertini who, with the help of Giovanni Morelli and Adolfo Venturi, undertook the first survey of external deposits in Milanese churches.

Corrado Ricci, on the other hand, was responsible for the systematic reorganisation of the picture gallery according to the criteria of the regional schools, the curatorship of the first museum catalogue, the establishment of the photographic library and a layout that set the standard in the history of museography: zenithal illumination and the dissemination of the most important data of the works through the introduction of museum cards.

A fundamental role in the preservation of the collection, which was threatened by the destruction of the Second World War, was played by Fernanda Wittgens, the first female director of the Pinacoteca di Brera, as well as the first woman in Italy to hold a managerial position in a major museum institution.

Franco Russoli, the father of modern museology, brought the museum into the new millennium, bringing Brera closer to the standards of international institutions. A proponent of an innovative involvement of the public and the local area, he transformed the museum into the driving force of public life in the city. The project to enlarge the museum complex, which he strongly desired and promoted through the acquisition of the nearby Palazzo Citterio, has recently been relaunched by the direction of James Bradburne. The last decades have been characterised by exhibitions, restorations

Ercole de’ Roberti

(detto anche Ercole Grandi o de’ Grandi) (Ferrara, 1450 circa - 1496)

Pala Portuense : Vergine in trono con il Bambino, i santi Anna, Elisabetta, Agostino e il beato Pietro degli Onesti 1479-1481

olio su tela, cm 323 × 240 Inv. 203

(Alle pagine seguenti)

Dettaglio del paesaggio marino in burrasca, che rievoca il naufragio scampato dal crociato Pietro degli Onesti (in basso a destra), connesso alla leggenda di fondazione, come ex voto alla Vergine, di Santa Maria in Porto.

Il capolavoro del ferrarese Ercole de’ Roberti è rappresentato dalla cosiddetta Pala Portuense commissionata dai Canonici agostiniani Lateranensi per l’altare maggiore di Santa Maria in Porto Fuori, a Ravenna, al fine di celebrare il fondatore della basilica e dell’ordine, il beato Pietro degli Onesti, scampato miracolosamente a un naufragio nel 1096 in prossimità del porto ravennate, al ritorno da un pellegrinaggio in Terra Santa. Travolto dalla tempesta, Pietro degli Onesti nelle preghiere per la salvezza aveva infatti promesso alla Vergine di dedicarle una grande chiesa: la memorabile veduta raffigurata nella pala, inserita fra la base del piedistallo e la pedana del trono sembra evocare l’episodio miracoloso. Nel secolo XVI l’opera passò nella chiesa di Santa Maria in Porto entro le mura della città, seguendo il trasferimento dei Canonici. I pagamenti riferiti all’opera risalgono al 1481, che si fissa quale terminus ante quem per l’esecuzione della monumentale pala a spazio unificato. Il trono a tabernacolo della Vergine, quasi composto d’un caleidoscopico prisma, si apre a visioni inaspettate, lasciandosi trapassare da un varco, che congiunge lo spazio illusivo della crociera all’affondo mirato sul paesaggio portuense, con una città che si affaccia sul mare mosso dai flutti, immersa in lontananza in brume dorate e minacciata da un cielo corrusco. Colonnine policrome affusolate, marcate da eccentrici elementi di capitello, creano un diaframma in grado di raccordare e sostenere la struttura senza interrompere lo sguardo, che può indugiare nella visione dell’inconsueto motivo paesistico, centrale a livello compositivo e concettuale. La pedana si articola in bassorilievi a fondo oro in cui sono visibili quattro scene a monocromo, fra «moti lancinanti e spiritati» e «azione pietrificata» (Longhi, 1934): Natività (o Adorazione dei pastori), cui si sovrappone il mantello di sant’Agostino a oscurarne una parte, Strage degli innocenti, Adorazione dei Magi e Circoncisione. Sul fronte si delinea anche un motivo di virtuosismo pittorico, con la raffigurazione del tappeto (di tipologia associabile a quelli con un solo “Holbein gul”) le cui frange scendono verso il basso, disegnando una movimentata griglia di mimesi naturalistica, tale da riuscire a cogliere persino la ritorcitura dei fili. Sul podio ottagonale s’innalza una monumentale triade quasi statuaria, composta dalle sante e al vertice dalla Vergine, luminosa nella geometrica volumetria pierfrancescana, mentre sostiene sulla gamba destra il vivace Bambino in piedi, che si sorregge posando la piccola mano sinistra su quella della Madre. Accanto, sant’Elisabetta instaura con il Salvatore un dialogo tanto “affettuoso”, animato dagli sguardi e incentrato sul cardellino, quanto drammatico nel presagio. Sulla destra, sant’Anna in preghiera congiunge le mani inarcandole, come a protezione e prefigurazione, volgendosi verso l’osservatore. La struttura piramidale articolata dai personaggi, con al culmine la Madonna, è serrata alla base da sant’Agostino, patrono dei Canonici Lateranensi, quasi benedicente e con la testa per metà in ombra angolata verso i fedeli, e dal beato Pietro degli Onesti immerso in lettura, con abito da canonico. I due avanzano sul piano proiettando dinamiche ombre, anche sullo zoccolo del piedistallo, dinanzi ai pilastri decorati con rilievi a candelabre anticheggianti sui quali s’imposta l’arco decorato da testine di cherubini variamente disposte, orientate e mosse dal mutare dell’incidenza luminosa. Sotto l’ariosa volta a crociera s’incurva la calotta del trono, sostanziata di vetri trasparenti che riflettono la luce e possono alludere alla purezza della Vergine. L’impianto solenne del baldacchino, da “cattedra ravennate”, s’innalza maestoso tra sfarzose decorazioni a catena e otto lastre sovrapposte di monocromi dorati. Con felici soluzioni e invenzioni prospettiche s’illustrano, da sinistra, nel registro superiore: Fuga in Egitto, Presentazione alTempio, Cristo fra i dottori, Battesimo di Cristo; in quello inferiore: Bacio di Giuda, due episodi (forse Pietà e Cristo al Limbo) parzialmente coperti dalla silhouette della Vergine, e infine Noli me tangere. Ai lati il trono è limitato da colonne analoghe a quelle che schermano il paesaggio marino, tra porfidi e serpentini, mentre lo schienale si modella a nicchia per avvolgere la Madre di Cristo e Mater Ecclesiae. Due scenografici drappi si aprono e s’inarcano raccolti ai lati, a suggerire anche un emblematico proseguimento teso verso l’alto senza soluzione di continuità. Un accordo sfavillante di cromie calde, dal rosso al giallo all’oro, si fonde con mimetici cenni di scultura dipinta, nei bassorilievi che simulano rilievi bronzei e nel tabernacolo, come pure nei pennacchi dell’arco, dove contro auree tessere mosaicate si stagliano e si rannicchiano due ignudi vibranti e severi: a sinistra Sansone con la mandibola d’asino con cui ha sconfitto i Filistei, e a destra il prodigioso Davide con la testa di Golia, che brandisce ancora l’affilata spada a mostrare di scorcio la lama fatale. La sapiente costruzione architettonica è montata in un ambiente al limite fra chiusura e apertura, tra il serrato pavimento marmoreo sulla soglia del primo piano e le lontananze marine e atmosferiche.

La Pala Portuense pervenne nella Pinacoteca di Brera il 26 aprile 1811, in seguito alle soppressioni napoleoniche, prelevata dalla chiesa di San Francesco dov’era stata ricoverata dopo la sconsacrazione di Santa Maria in Porto, avvenuta nel 1798. Andò perduta anche la memoria della paternità, tanto che l’opera fu assegnata a “Stefano da Ferrara”; dopo preziose indicazioni di Cavalcaselle (1871), fu Adolfo Venturi (1887) ad attribuire definitivamente la tela a Ercole de’ Roberti.

Ercole de’ Roberti

(also known as Ercole Grandi or de’ Grandi) (Ferrara, c. 1450 - 1496)

Portuense Altarpiece : Vergin enthroned with Christ Child, Saints Anne, Elisabeth, Augustine and the Blessed Pietro degli Onesti 1479-1481

oil on canvas, 323 × 240 cm

Inv. no 203

(Following pages)

Detail of the seascape in a storm, recalling the shipwreck escaped by the crusader Pietro degli Onesti (bottom right), connected to the legend of the foundation of Santa Maria in Porto as a votive offering to the Virgin Mary.

The masterpiece by Ferrara-born Ercole de’ Roberti is the so-called PortuenseAltarpiece, commissioned by the Lateran Augustinian canons for the high altar of Santa Maria in Porto Fuori, Ravenna, in order to celebrate the founder of the basilica and of the order, the Blessed Pietro degli Onesti, who miraculously escaped a shipwreck in 1096 near the port of Ravenna, on his way back from a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. Overwhelmed by the storm, Pietro degli Onesti in his prayers for salvation had in fact promised the Virgin that he would dedicate a large church to her: the memorable view depicted in the altarpiece, inserted between the base of the pedestal and the throne platform, seems to evoke the miraculous episode. In the sixteenth century, the work passed to the church of Santa Maria in Porto within the city walls, following the transfer of the canons. Payments for the work date back to 1481, which is fixed as the terminus ante quem for the execution of the monumental unified space altarpiece. The tabernacle-like throne of the Virgin, almost composed of a kaleidoscopic prism, opens up to unexpected visions, allowing itself to be pierced by a gap that connects the illusory space of the cross to the focused lunge over the harbour landscape, with a city overlooking the sea moved by the waves, immersed in the distance in golden mists and threatened by a coruscating sky. Tapered polychrome columns, marked by eccentric capital elements, create a diaphragm capable of connecting and supporting the structure without interrupting the gaze, which can linger in the vision of the unusual landscape motif, central to the composition and conceptual level. The platform is articulated in bas-reliefs with a gold background in which four monochrome scenes are visible, amidst ‘excruciating and spirited motions’ and ‘petrified action’ (Longhi, 1934): Nativity (or Adoration of the Shepherds), overlaid with Saint Augustine’s cloak to obscure part of it, Massacre of the Innocents, Adoration ofthe Magi and Circumcision. On the front, a motif of pictorial virtuosity also emerges, with the depiction of the carpet (of a type that can be associated with those with a single Holbein gul) whose fringes descend downwards, drawing a lively grid of naturalistic mimesis, such that even the twisting of the threads can be captured. On the octagonal podium rises a monumental, almost statuesque triad, composed of the saints and, at the top, the Virgin, luminous in her Piero della Francesca’s geometric volumetry, while holding on her right leg up the lively standing Child, who supports himself by resting his small left hand on that of the Mother. Next to her, Saint Elizabeth establishes a dialogue with the Saviour that is as affectionate animated by glances and centred on the goldfinch, as it is dramatic in its foreboding. On the right, Saint Anne in prayer joins her hands, arching them as if to protect and foreshadow, turning towards the observer. The pyramidal structure articulated by the figures, with the Madonna at the apex, is clasped at the base by Saint Augustine, patron of the Lateran Canons, almost blessing and with his head half in shadow angled towards the faithful, and by Blessed Pietro degli Onesti immersed in reading, wearing a canon’s habit. The two advance on the plane, casting dynamic shadows, even on the plinth of the pedestal, in front of the pillars decorated with antique candelabra reliefs on which the arch decorated with cherubs’ heads variously arranged, oriented and moved by the changing incidence of light. Beneath the airy cross vaulting curves the canopy of the throne, substantiated by transparent glass reflecting the light and possibly alluding to the purity of the Virgin. The solemn layout of the baldachin, like an Epischopal Chair, rises majestically amidst sumptuous chain decorations and eight overlapping slabs of gilded monochromes: with felicitous solutions and perspective inventions, they illustrate, from the left, in the upper register Flight into Egypt, Presentation in theTemple, Christ among the Doctors, Baptism ofChrist; in the lower register, Kiss ofJudas, two episodes (possibly Pietà and Christ in Limbo) partially covered by the silhouette of the Virgin, and finally Noli me tangere. On the sides, the throne is limited by columns similar to those shielding the seascape, amidst porphyries and serpentines, while the back is modelled as a niche to envelop the Mother of Christ and Mater Ecclesiae. Two scenographic drapes open and arch gathered at the sides, also suggesting an emblematic continuation stretched upwards without interruption. A sparkling arrangement of warm colours, from red to yellow to gold, blends with mimetic hints of painted sculpture, in the bas-reliefs simulating bronze reliefs and in the tabernacle, as well as in the spandrels of the arch, where two vibrant and severe nudes stand out and crouch against golden mosaic tiles: on the left Samson with the donkey’s jawbone with which he defeated the Philistines, and on the right the prodigious David with the head of Goliath, still wielding the sharp sword to foreshorten the fatal blade. The skilful architectural construction is mounted in an environment on the borderline between closure and openness, between the tight marble floor on the threshold of the first floor and the distant sea and atmosphere.

The PortuenseAltarpiece arrived in the Pinacoteca di Brera on 26 April 1811, following the Napoleonic suppressions, taken from the church of San Francesco where it had been kept after the deconsecration of Santa Maria in Porto in 1798. The memory of the paternity was also lost, so much so that the work was assigned to “Stefano da Ferrara”; after valuable indications by Cavalcaselle (1871), it was Adolfo Venturi (1887) who finally attributed the canvas to Ercole de’ Roberti.

Giovanni Bellini (Venezia, 1430 circa - 1516) Madonna con il Bambino 1510

olio su tavola trasportata su tela, cm 85 × 115 sull’altare a sinistra: «JOANNES / BELLINVS / MDX» Inv. 298

L’invito a contemplare «quei segni dell’eternità nelle gemme del Bellini» fu espresso da Testori nel 1986 in occasione del restauro dei due dipinti di Giovanni Bellini ora a Brera raffiguranti la Madonna con il Bambino. Il quadro datato 1510 è riconoscibile nella descrizione di Oretti del 1769 in Palazzo Monti a Bologna; fu poi di proprietà Sannazari, da cui passò nel 1804 all’Ospedale Maggiore di Milano; nel 1806 fu acquistato per l’Accademia di Brera. Nonostante il trasporto da tavola su tela (attuato nel 1893, ma già Morelli nel 1861 ne lamentava lo stato conservativo), la pittura testimonia la piena ricchezza cromatica distesa da Bellini sull’appunto disegnativo sottostante, contorno compendiario di forme, ravvisabile nella Madre e nel Bambino, «quasi che, giunto al culmine della propria parabola, il maestro vivesse il colore (il colore della luce, ma anche il colore nella luce) come strumento totale», tanto da arrivare in alcuni punti a stendere «la materia direttamente con le dita, come testimoniano l’orme, visibilissime, sul dilontanante paese», nella lettura di Testori. L’intensità luminosa sottolinea il gruppo figurale, rilevato contro un autonomo «drappo d’onore», mentre il paesaggio dal primo piano procede sino all’orizzonte al crepuscolo. Risalta sulla sinistra un animale maculato sovrastante l’ara iscritta con la firma e la data; sulla destra si scalano un pastore con il suo gregge e una pecora isolata, un cavaliere e un uccello intrappolato fra le panie sull’albero. Tra simboli e presagi, s’impongono monumentali la Madre con il Bambino benedicente. Per il ghepardo sull’ara antica, Giovanni Agosti ha richiamato non solo modelli dagli album di Jacopo Bellini, ma anche da taccuini tardogotici. Marcantonio Michiel nel 1530 segnalava «el libretto in quarto in cavretto cum li animali coloriti fu de mano de Michelino Milanese», Michelino da Besozzo, nella collezione veneziana di Gabriele Vendramin, che includeva anche dipinti di Giovanni Bellini, nonché il Libro dei disegni di Jacopo Bellini ora al British Museum di Londra.

Giovanni Bellini (Venice, c. 1430 - 1516)

Madonna and Child 1510

oil on panel transported on canvas, 85 × 115 cm on the altar to the left: ‘JOANNES / BELLINVS / MDX’ Inv. no 298

The invitation to contemplate ‘those signs of eternity in Bellini’s gems’ was expressed by Testori in 1986 on the occasion of the restoration of the two paintings by Giovanni Bellini now in the Brera depicting the Madonna and Child. The painting dated 1510 is recognisable in Oretti’s description of 1769 in Palazzo Monti in Bologna; it was later owned by Sannazari, from whom it passed to the Ospedale Maggiore in Milan in 1804; in 1806 it was purchased for the Brera Academy. Despite being transferred from panel to canvas (carried out in 1893, but already in 1861 Morelli lamented its state of preservation), the painting bears witness to the full chromatic richness spread by Bellini over the underlying drawing, a compendium of forms, recognisable in the Mother and Child: ‘… almost as if, having reached the culmination of his own parabola, the master lived colour (the colour of light, but also the colour in light) as a total tool’, so much so as to go so far as to stretch ‘the material directly with his fingers, as testified by the footprints, very visible, on the distant country’, in Testori’s reading. The luminous intensity emphasises the figural group, raised against an autonomous ‘drape of honour’, while the landscape from the foreground proceeds to the horizon at dusk. Standing out on the left is a spotted animal above the altar inscribed with the signature and date; on the right are a shepherd with his flock and an isolated sheep, a horseman and a bird trapped in the panie on the tree. Between symbols and omens, the Mother with the Blessing Child stands out monumentally. For the cheetah on the ancient altar, Giovanni Agosti drew not only models from Jacopo Bellini’s albums, but also from late Gothic notebooks. Marcantonio Michiel in 1530 pointed out ‘el libretto in quarto in cavretto cum li animali coloriti fu de mano de Michelino Milanese’ ('the booklet made of goatskin with hand-coloured animals by Michelino from Milan'), Michelino da Besozzo, in the Venetian collection of Gabriele Vendramin, which also included paintings by Giovanni Bellini, as well as Jacopo Bellini’s Book of Drawings now in the British Museum in London.

Luca Giordano

(Napoli, 1634 - 1705)

Ecce Homo 1659-1660

olio su tela, cm 158 × 155 Inv. 5112

(A fronte) Particolare.

L’opera rivela influssi figurativi neoveneti e da Mattia Preti. La tela pervenne a Brera nel 1979, per esercizio del diritto di prelazione in occasione di una richiesta di esportazione. A Baltimora (The Walters Art Museum) è conservata un’ulteriore redazione del tema (una cui replica è a Napoli, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte), datata 1650-1655 circa, come il pendant con Cristo davanti a Pilato (Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection). L’esemplare braidense, come il precedente di Baltimora, rappresenta una libera replica dell’ Ecce Homo di Dürer, databile 1498 circa, appartenente al gruppo di otto xilografie giovanili riutilizzate per la serie completa della Grande Passione edita in

volume nel 1511. Nell’animata raffigurazione degli spettatori, compreso il personaggio che si volta con gli occhiali cerchiati à pince-nez (gli stessi che l’artista ostenta in numerosi autoritratti), risalta lo stacco luministico e cromatico di mantello, veste e turbante del memorabile astante anziano, presente anche nel dipinto di Baltimora e ripreso da una stampa di Luca di Leyda del 1510. L’abilità di Luca Giordano nelle esercitazioni sugli antichi maestri trasse in inganno committenti e collezionisti, compreso Gaspar Roomer. Nel 1664 Giacomo di Castro avrebbe messo in guardia don Antonio Ruffo su alcune opere dipinte da Luca Giordano «contrafacendo ora Titiano ora Paolo Veronese… ha fatto buona pratica e poi ci da una tinta antica che non fanno mala vista». Giordano fu detto anche Luca Fa Presto: un soprannome evocativo non solo di rapidità, ma anche di «prestezza» esecutiva, «velocità nel pennello nel dipingere, nel concepire e nel partorire in un fiato medesimo», secondo l’ Abecedario pittorico di Pellegrino Antonio Orlandi del 1704.

Luca Giordano

(Naples, 1634 - 1705)

Ecce Homo 1659-1660

oil on canvas, 158 × 155 cm Inv. no 5112

(Opposite) Detail.

The work reveals figurative influences from the neo-Venetian period and from Mattia Preti. The canvas came to Brera in 1979, through the exercise of the right of preemption on the occasion of an export request. In Baltimore (The Walters Art Museum) there is a further redaction of the theme (a replica of which is in Naples, Museo Nazionale di Capodimonte), dated around 1650-1655, like the pendant with Christ before Pilate (Philadelphia Museum of Art, John G. Johnson Collection). The exemplar from Brera, like its Baltimore predecessor, is a free replica of Dürer’s Ecce Homo, dated c. 1498, belonging to the group of eight early woodcuts reused for the complete series of the Great Passion

published in 1511. In the animated depiction of the spectators, including the turning figure with the circled spectacles à pince-nez (the same spectacles the artist flaunts in numerous self-portraits), the luministic and chromatic detachment of the cloak, robe and turban of the memorable elderly bystander, also present in the Baltimore painting and taken from a print by Luca di Leyda of 1510, stands out. Luca Giordano’s skill in practising the old masters misled patrons and collectors, including Gaspar Roomer. In 1664, Giacomo di Castro is said to have warned Don Antonio Ruffo about some of the works painted by Luca Giordano ‘counterfeiting now Titiano and now Paolo Veronese... he has made good practice and then gives us an antique tint that do not make a bad sight’. Giordano was also called ‘Luca Fa Presto’ (‘Luca Paints Quickly’): a nickname evocative not only of speed but also of executive ‘prettiness’, ‘speed in the brush in painting, in conceiving and giving birth in the same breath’, according to Pellegrino Antonio Orlandi’s Abecedario pittorico of 1704.

L’incredibile

collezione di oltre duemila opere della Pinacoteca di Brera accompagna il visitatore in un viaggio nell’evoluzione del segno e del colore, nella storia gurativa e nella geogra a artistica italiana e internazionale, lungo un arco temporale che si estende dal Duecento al Novecento. In questo ricco ed eterogeneo patrimonio, articolato in 38 sale espositive, le 100 opere qui raccolte propongono un percorso ideale di visita attraverso i tesori fondamentali di Brera, che identi cano iconicamente il museo e ne costituiscono l’identità visiva e culturale da secoli, e piccoli capolavori di artisti condannati all’oblio dall’evoluzione del gusto, ma meritevoli di maggiore considerazione. Una sensazionale immersione nella storia della pittura occidentale, attraverso un itinerario che valorizza le scuole geogra che e la pluralità di generi. / e Pinacoteca di Brera’s incredible collection of over two thousand works takes the visitor on a journey through the evolution of sign and colour, gurative history and Italian and international artistic geography, over a period of time that stretches from the thirteenth to the twentieth century. In this rich and heterogeneous patrimony, articulated in 38 exhibition rooms, the 100 works collected here propose an ideal tour through Brera’s fundamental treasures, which iconically identify the museum and have constituted its visual and cultural identity for centuries, and small masterpieces by artists condemned to oblivion by the evolution of taste, but deserving of greater consideration. A sensational immersion through the history of Western painting, through an itinerary that emphasises geographical schools and the plurality of genres.