Part 1: Worldmaking, Worldbreaking: the World that Colonialism Made

Ananya Kabir

Ananya Kabir

On June 23, 2022, we at the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam, opened our newest semi-permanent exhibition. Titled Our Colonial Inheritance, this exhibition is curated as part of the museum’s ongoing critical reflection on, and intervention in, the growing national and international discussions on European colonialism, its histories and its afterlives in the present. It was part of a project that began several years earlier, which would be the museum’s first full refurbishment in almost two decades. Coming at the end of this refurbishment, Our Colonial Inheritance was, arguably, the most important part of this project, tying the earlier completed displays, for instance Things that Matter, a contemporary reflection on the multiple ways that objects shape and give meaning to people’s lives, to the institution’s colonial history.

As is well known, the Tropenmuseum is the successor of the Colonial Museum. Originally founded in Haarlem in 1864, the museum was established to support the Dutch colonial project. Indeed, for much of its early career, the Colonial Museum would serve as an etalage for the display of the products of a colonialism practiced overseas; an important part of its role being to educate a visiting Dutch public into the ideological underpinnings of colonialism, and to inform them about the “opportunities” of becoming part of the colonial project. As a result of its early successes, the museum would quickly outgrow its premises, leading to its relocation in 1926 to its current location in Amsterdam.

Our entangled histories: how we (un)learn

Our Colonial Inheritance: so who is the ‘we’ implied here? Am I part of this ‘we’?

As I walk through the new permanent exhibition at the Tropenmuseum, I come face to face with a photograph restored from the archives. It is a typical artefact from the early days of colonial photography, during which the camera was used to capture – again –the already captive subjects of capitalism and empire. 5 The remastered image has her rising from the depths of visual imprecision, an unlikely Venus taking shape through the curator’s gaze. She looks back, unflinching, unsmiling. Her straight black hair is tied back in two plaits that remind me of Indian school uniforms. She appears to wear small earrings and a simple necklace. Her eyes give nothing away, except a steely glint.

The information label tells me that she is ‘Elisabeth Moendi’ (who gave her this name?). Born in Bengal c. 1860, she was brought to Amsterdam from Suriname with 27 others to be exhibited at the Colonial Trade and Exports Exhibition in 1883. The photograph was taken for this occasion. She was accompanied by her threeyear-old daughter, Henriette, probably fathered by an indigenous man. But what was this Bengali woman doing in Suriname, and why is an image of someone born as a British subject, in colonial India, exhibited in the Tropenmuseum as part of Our Colonial Inheritance?

Elisabeth Moendi was shipped out from Bengal by the Dutch, who had struck a deal with the British in exchange for favours the Dutch granted the British in Batavia. She was one of approximately 34,000 others, starting with the 399 Indians who disembarked in Paramaribo on the ship Lalla Rookh in 1873. The probable date of her birth means that she might even have been one of those first arrivals.6 She remade her life in Suriname, brought forth a new life there, before being taken to Amsterdam as a prize exhibit of racial capitalism. Interimperial collaboration oiled the wheels of that capitalism.7 Elisabeth Moendi, at 23 years of age, in the 19th century, was a veteran of three sea voyages.

Her life across two oceans, two hemispheres and three continents: I feel it as connected to mine. She and I share a city. The port of Calcutta, through which Elisabeth Moendi left the shores of India, is also where I was born as an Indian in postcolonial India. This is a city that, as our history lessons told me and everyone around me repeated, was the capital of the British Empire. It is a city in whose postcolonial imagining, memories of the Dutch play no role. 8 It is a city whose mirror image I was taught to see in the grand buildings of London (never in Amsterdam). Now Elisabeth Moendi, in one such grand building, looks directly at me.

I found myself standing in front of her image for a long time. The centuries and oceans seemed to dissolve as I engaged in wordless communion with this ancestral spirit, who demands that I enter her story.

as well as generations and cultures.’ Food, and foodways, render the oceans continuous. Nasi from Indonesia and roti from Suriname make me feel at home in Amsterdam.

In India, and in Britain (my two homes), I find rice and roti everywhere. But I won’t find roti and nasi served alongside bami, loempia and pom in a warung. Our Colonial Inheritance is this sensuous education in transoceanic solidarity, where entanglement leads to a shift in received knowledges and the small epiphanies of daily life reopen reified positions and expectations to new modes of scrutiny.

As a literary and cultural critic, I have been fed a conceptual diet of ghosts, hauntings and spectral presences. I am now ready to taste something new. These women and their traces offer me palpable presence in the Tropenmuseum, and they invite me to throw my own weight behind them. This is the heavy weight of history on the emporium of the capitalist world.

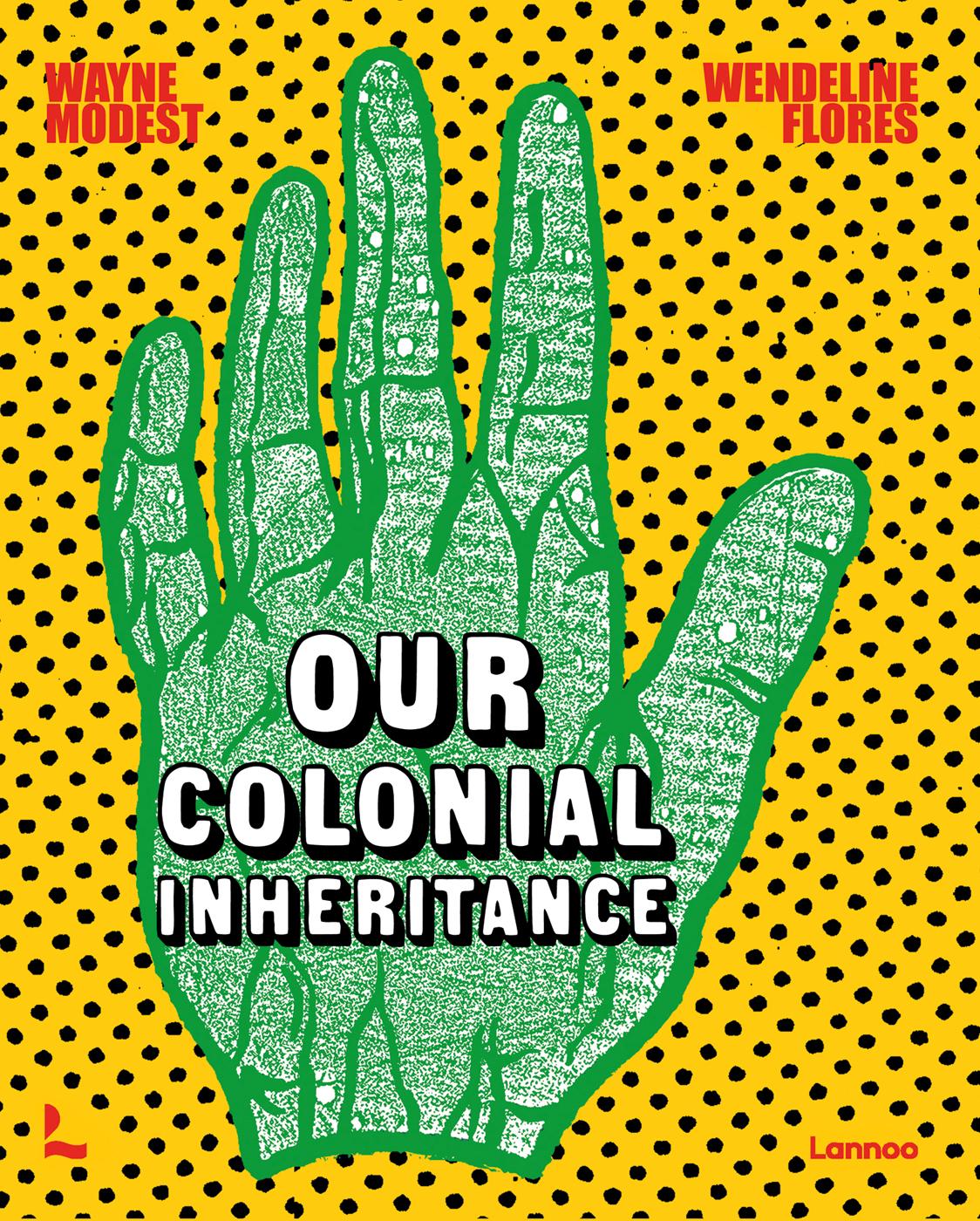

The work of contemporary artist Sarojini Lewis, born in the Netherlands with Surinamese, Indian and Eurasian grandparents, stands in the same space as Elisabeth Moendi’s image – not directly facing it, but at an angle that invites a more complex, multidirectional joining of the dots. Sarojini’s almost-nude body is larger than life. It is smeared with the colours of Holi – a joyous festival but one that also brings into my memory the traumatic realisation that a South Asian woman’s body is always threatened by external forces seeking redress for deep-seated inequities and humiliations. Holi was the time when the protective circle of class and education was dissolved in the mayhem and euphoria, in the midst of which always lurked the sharp edge of madness. But in the decades I have lived outside India and learnt from communities of the indentured labour diasporas, I have come to understand that Holi (re)gains the charge of resistance through collective play, of celebrating the transplantation and creolisation of identity after kala pani. 17

Fig. 9 Room 327: In the Aftermath of Holi #1, #2, #3, #4, #5, #6, #7, #8, Sarojini Lewis, 2016 / 65 × 80 × 0.3cm, photographic paper; colour photography, National Museum of World Cultures collection, inventory no. 7247-1, 7247-2, 7247-3, 7247-4, 7247-5, 7247-6, 7247-7, 7247-8. © Sarojini Lewis. Photography: Pascal Giese

1 Territory Dress, Susan Stockwell, 2018 / 156 × 145 × 225cm, paper (fibre product) wood (standard); printed cotton, computer wire, National Museum of World Cultures collection, inventory no. 7175-1a. © Susan Stockwell

by Susan Stockwell

Daan van Dartel

There she goes, proudly striding towards the centre of the exhibition. Dolores is wearing a beautiful dress, in which we can identify centuries of Dutch imperial operations. It makes us wonder, what was the role of women in these times? When we take a closer look, we see that the dress is made of paper and printed cloth. Not just any paper, but maps, instruments of territorial control of land and people. Through maps, European men governed the bodies of women, and of lands they sought to colonise.

The bodice of this carefully crafted dress is made from an older map of Suriname. A contemporary, late 20th-century map of the Netherlands sits on top, a metaphor for centuries of colonial exploitation. Blood drips down from its sleeves, delineating the motorways and roads mapped upon its surface. Maps are communication devices through which knowledge is gained about otherwise inhospitable lands. They function as a device for opening up possibilities and opportunities. In the hollow of the woman’s abdomen, a small boat sails away from Amsterdam. Its sail is made from an Antillean guilder, worth much less than the Dutch guilder from which it was derived. Where is it going? We do not know, but along the lower part of the dress, destinations abound: from South Africa to Indonesia. Carefully folded into small pleats, as was the fashion in the 19th century – the heyday of colonialism. These pleats look like waves, taking the boat to places unknown, places to be discovered and conquered… while the hollow of the abdomen questions the origins of bodily and national proprietary.

The train of the dress, that looks as if it is moving, passing through space and time, is made from another communication device, so to speak. Angisas are placed on top of one another,

There are many connections that continue to tie together ‘New England’ and the ‘West Indies’ through various kinds of materialities and mobilities that have shaped my own life experiences. I want to trace some of these mobilities and enclosures here, through my personal experiences of travel and tourism, and suggest that people in the Netherlands could do the same. Indeed, the islands and coastal enclaves of New England and the West Indies were central to the colonial ‘scenes of subjection’ that writer Saidiya Hartman has described, and these places are still marked by the histories of racialised (im)mobilities that made the modern world.6

Fig. 3 View of Marigot, Saint-Martin. Photography: Boy Lawson, 1964 / 6 x 6cm, National Museum of World Cultures collection, inventory no. TM-20017549

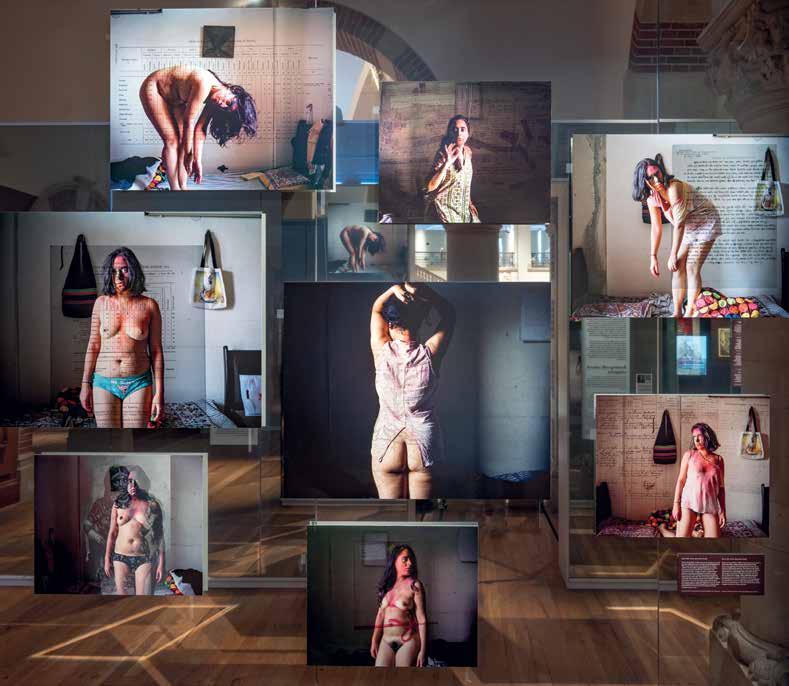

Zico, what incited you to make this work? Where did you draw your visual inspiration from and what led you to choose these motifs within this painting?

In 2015, I saw Basic Values, a work of art by Herman de Vries in the Erasmus Huis in Jakarta. He had never visited Indonesia and listed different types of rice to illustrate the biological wealth

of Java. In Sundanese tradition, this rice carries its own sacred meaning and is commonly used in ruwatan rituals. This triggered me to think more in depth about colonial relations. At school I had learned about the VOC, the plantations and the cruelty of the Dutch. I had heard stories from my family about the colonial past and the complicated struggle after Indonesian independence. My work began with a

Fig. 1 Ruwatan Tanah Air Beta, Reciting Rites in its Sites, Zico Albaiquni, 2019 / ca. 200 × 600cm, oil paint; canvas; synthetic dye; oil painting, National Museum of World Cultures collection, inventory no. 7224-1. © Zico Albaiquni. Courtesy of the artist and Yavuz Gallery, Liefkes-Weegenaar Fonds, Framer Framed & Sadiah Boonstra

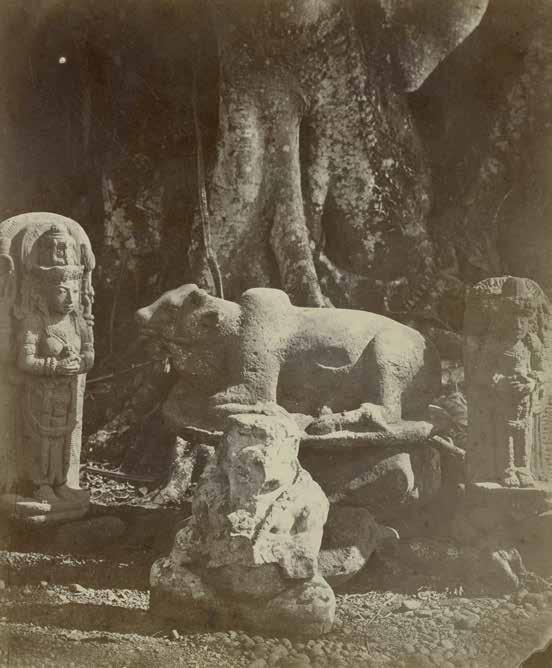

Fig. 2 Four stone statues, including the Nandi and the Ganesha, in the Bogor Botanical Garden, photographed by Isidore van Kinsbergen, 1863 / 23 × 19.5cm, paper; cardboard, pasted on cardboard, National Museum of World Cultures collection, inventory no. RV-1403-3790-1

ceremony called ruwatan, which I held at Kebun Raya Bogor, the botanical garden in Bogor, West Java. Ruwatan in Sundanese tradition is a ritual to cleanse the world from bad omens, reconnect with nature, the spirits of the ancestors, and God. It involves offerings of natural products such as beans, rice, tobacco, and praying on the site. During the ceremony I went into a trance near the old Dutch cemetery and ‘saw’ different objects in the garden that connected with different histories and cultures.

The ruwatan ceremony was a symbolic act to illustrate my clean intention and I used it not only as a metaphysical activity and symbolic ritual but also as an artistic action to reconnect our physical world with our spirituality, activating our own collective memory, transferring our own knowledge, revisiting history and reimagining the future. For only in the future can we know more about the past. So this painting encapsulates my journey and the artistic and spiritual process I underwent during this ruwatan.

The contextual setting of this work plays a key role in our understanding of it. Why did you choose this specific site? I chose Kebun Raya Bogor, Bogor Botanical Gardens, as the site for my work of art for its historical value in Indonesia’s history and especially for its cultural value for the Sundanese people in West Java. I am from Bandung, and my wife’s family is from Bogor. According to Sundanese history, the original site (called Samida) was a man-made forest intended as a botanical conservation area and used by Prabu Siliwangi, a famous Sundanese king (1482–1521), to practise asceticism. So some of the first objects I ‘discovered’ were some stone statues, dating from that early period. I found a photograph of the site in the collection of the National Museum of World Cultures (RV-14033790-1).

One of the statues is that of the bull Nandi. In ancient Sundanese spiritual beliefs (Sunda Wiwitan), this statue is regarded as a representation of Mundinglaya, a prince in Sundanese folklore. Today, the statues have been rearranged and

sionals worked with us: artists, filmmakers, musicians, poets.

As an exhibition developer, you produce many resources for an exhibition: films, interactives, graphics, etc. I usually write those out in great detail, but this time I tried to leave it much more open-ended. That was exciting, because you have no idea of the outcome. But it was also wonderful to do, because such amazing things came out of it that neither we as a museum nor I as an exhi-

bition developer could have thought of on our own.

You can’t say: we’re making an exhibition and in the last room we’ll give an artist the space to reflect – that’s just passing the buck. You have to take responsibility – we’re the ones wanting to make this exhibition, not the artist. So in the end we did take many decisions ourselves. As an institution, it’s your intellectual responsibility to represent the story you want to tell.

We’re increasingly aware that making an exhibition, such as this one, isn’t simply about objectivity and expertise, but it’s also about positionality. Would you like to share something about your own position in terms of this exhibition? How did your role as an exhibition developer shape the final result? And while we hope that this exhibition allows our visitors to think differently about their shared history, did this process also have an impact on you personally?

The museum’s position is crystal clear: there is no good side to colonialism. In the very first text, we name violence, inequality and contemporary racism as its inheritances. A position like that creates enormous clarity, both for us as curators and for the audience. It’s clear from the explicit wording of the exhibition texts. And I think we need to remember that if you take a ‘neutral’ stance, you’re assuming a position that maintains the status quo.

Fig. 2 Photograph of Coloured Drawings, Marlene Dumas, 1997 / 24 drawings measuring 32 × 27.5 × 1cm, East Indian ink drawings; coloured ink and mica paint on 400mg velin arches paper; framed in wooden frames behind micromagic antireflective glass, National Museum of World Cultures collection, inventory no. TM-ib-2013-31-03a. Photography: Kirsten van Santen

Isabelle Romee Best

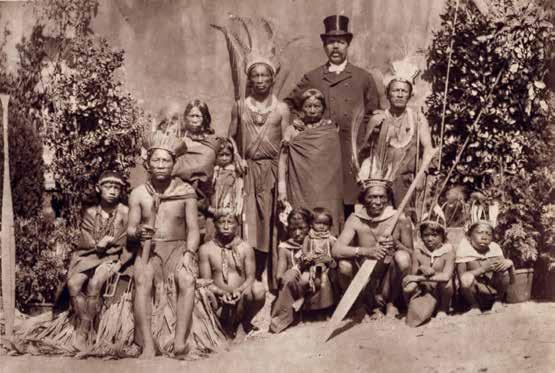

A painted backdrop of a jungle and a number of potted plants add depth and a theatre-like ambience to the static composition of the 13 Kari’na and Lokono, people who were displayed at the International Colonial and Export Exhibition held in Amsterdam in 1883. The image was captured at the exhibition’s department of Dutch Colonies by Photostudio Française, owned by father and sons Amand, and was kept in the photo album ‘Album Suriname’ in the Tropenmuseum’s collections.

The title at the top of the ‘cabinet card’ carefully frames the picture and the people in it as ‘Aboriginals of Suriname’. 1 These Indigenous peoples from Suriname were made to play out everyday scenarios in a circus tent where an international crowd could visit them during the opening hours of the exhibition. Unlike other colonies, the Surinamese presence was privately arranged by the ‘Surinamese Committee’ and carried out by the ScottishKari’na William Mackintosh. The Surinamese Indigenous peoples sold these cabinet cards primarily to cover the costs of the Surinamese participation, and in part to pay their own wages. 2 These cards were collected to be included in photo albums or displayed on cabinets. 3 While the exploitative character of this exchange is evident, these Indigenous peoples also acted upon the complex power relations for their own benefit.

The composition of the picture guides the viewer’s eye to Jean Baptiste Ka-Ja-Roe, the central figure wearing a feathered highreaching headdress and beaded necklaces. Ka-Ja-Roe, together with the figures on the left-hand side, is looking at us. This framing pushes the man, set in stark contrast due to his Victorian attire, into the background. Historian and former employee

Fig. 1 An Indigenous group from Suriname pictured at the Colonial Exhibition held at Museumplein in Amsterdam, photo studio: Photographie Française, Amsterdam, 1883 / 9.8 × 14.2cm, photograph, National Museum of World Cultures collection, inventory no. TM-60002202

responsible for heritage, information and library services at the Royal Tropical Institute (KIT), Paulien Schuurmans attests that the figure in the image is Mackintosh, possibly based on the subconscious biases that arise from connecting skin complexion and colour to race and ethnicity.4

At the time, this colonial imagery was meant to carry an ideological message framed by the 19th century’s construction of civility vs the primitive, respectability vs savagery. The Indigenous peoples in this photograph were understood in terms of a folk type – that is, the ‘noble savage’ – and were deemed innocent, somewhat cultured, and living in harmony with nature, isolated from Western civilisation and development. On the other hand, Mackintosh embodied the possibility of ‘modernising and civilising’ the Indigenous population

seem, I am indeed suggesting that betrayal can serve as an occasional form of solidarity. For whether it is the relationship between Dessalines and Toussaint, or many of the literary fictions that narrate the moment, 39 it is the condition of intimacy – as a space in which crucial information is relayed – and whereby sometimes duplicity becomes the only means to successfully determine the appropriate course of action, no matter how violent – connoted as unnoble or disorderly – betrayal may seem.

In 1904, Jan Musset designed – for the Dutch company Cacao Droste – an image which created a ‘visual loop because of the infinite recursion caused by self-reference on a packet of Droste cocoa […].’40 In Musset’s well-known advertisement, the woman dressed in a nurse’s uniform appears multiple times and faces the viewer. Jean-Louis invokes the Droste effect, only here the woman’s back faces the museum visitor, and the repetition is not of the woman herself, but of the scarred back of Gordon, also referred to as Peter, an enslaved person in Louisiana, who had escaped. Cultural historian Matthew Fox-Amato argues that the photo circulated among abolitionists, with many photos taken of enslaved persons used by pro-slavery advocates to show the supposed civilising mission of slavery.41 To think about Jean-Louis’ artwork alongside Gordon’s real-life experience and Fox-Amato’s historical writing forces us to grapple with the question of how we inherit notions of benevolence, what Africana studies scholar Kaiama L. Glover has referred to as those ‘benign denials’ that regiment our very (hypocritical) notions of goodness.42

In the same way that both the nurse and the cocoa are the focus of the repetition in the Droste advertisement, in Jean-Louis’ piece, by taking up the paintbrush, the woman depicted in her photograph draws the viewer’s attention to the reworking of Gordon’s scars, in the painting in colour, and on her own back as a golden rhizomatic pattern, what the second museum label refers to as: ‘The pattern

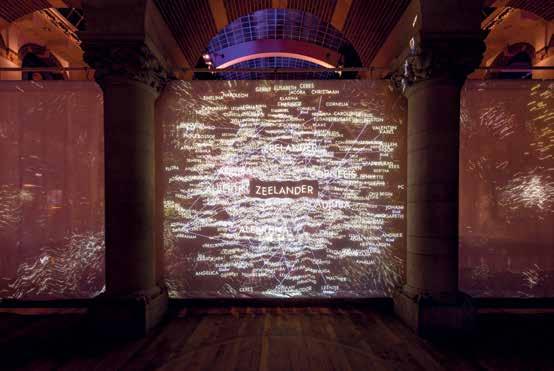

Wendeline Flores

In collaboration with studio AFARAI, Kossmann.deJong, and the exhibition team, visual artist Farida Sedoc created an installation for one of the galleries of Our Colonial Inheritance. Sedoc created a multi-layered visual narrative titled We’ve Been Here Before You Know, which centres on the power and resilience of language and knowledge formation. Each individual will recognise something familiar represented by the prints, patterns and symbols on display. Nonetheless, thanks in part to her use of primary colours and bold graphics, the artist’s signature is clearly visible throughout the space. Traces of colonialism, evident in the numerous languages we speak worldwide, are illustrated by prints of pages from dictionaries, over which a layer of camouflage motifs in black and white is superimposed. Words are powerful and potentially violent. The title of the work is printed repeatedly so that the visitor can read it differently, over and over again. We continued to work together on the design of this publication. During that process, Sedoc shared some thoughts with Wendeline Flores on the legacy of colonialism.

Farida, can you tell us about your artistic practice? What is important to you?

I would call my practice multidisciplinary, with ‘work’ that can take various forms and be expressed through different media and platforms, depending on the time and place. Hopefully, this fluidity doesn’t make my signature any less unambiguous. I want to inspire the viewer to see alternative

perspectives and hope that my work is still accessible and relatable to groups that may have no immediate affinity with the traditional art world.

What do you think is the most important legacy of colonialism?

The realisation that we are all connected. No matter where we live and which social bubble we’re in.

Does this affect your work as an artist as well as your personal life?

It has an impact on my work to the extent that my inspiration can draw on the idea of globalisation, the ongoing process of the international exchange of people, products, money, knowledge, art and culture. This global integration has led to interrelationships between territories, creating prosperity for one group of people and

misery for another. The meaning of life and death, heritage and ancestry are therefore central themes in my work.

You say the legacy of colonialism is something that connects us all. What steps can we take together to move towards a more just world? How do we collectively create a better future and what role can art play in this?

As postcolonial communities have developed into multigenerational and diverse communities, the notions of longing and belonging are shifting too. As more and more people inhabit multiple identities where their ethnic background is concerned, we see an increase in the awareness of and the interest in how different colonial stories connect and play out in present-day Dutch society. The deep colonial roots of present-day global inequalities, also in former Dutch colonies, such as Indonesia and Suriname, are recognised (as they are in Our Colonial Inheritance).

What is changing through the generations is that younger generations are beyond the in-between as a space of doubt, insecurity and apprehension. The in-between for them does not seem to mean that you do not belong anywhere, but that you belong in multiple places. As Moluccan second-generation youth felt that they needed to speak out and act in the 1970s because the Netherlands was NOT their country, the generation of their (grand-)children is speaking out because they consider the Netherlands to ALSO be their country. Instead of ‘either or’, ‘as well as’ has taken centre stage. The protests against racism and racist practices such as Zwarte Piet also voice a sense of belonging.

Postcolonial communities have not faded away or been assimilated into Dutch society. They have been instrumental in pushing for a change in the way Dutch society sees itself and tries to come to terms with its colonial history and the postcolonial present. Different generations have employed different strategies and means, but what is also visible is a growing awareness of the importance of knowledge. The way dominant narratives have been produced and institutionalised, but also how genealogies of resistance and resilience are there to discover and to share in order to work towards a society where belonging does not mean ticking boxes but is an open invitation. The experience of postcolonial communities and individuals can be an important part of that process. As a second-generation child of a Moluccan father and an Indo-European mother, I experienced many of the developments described

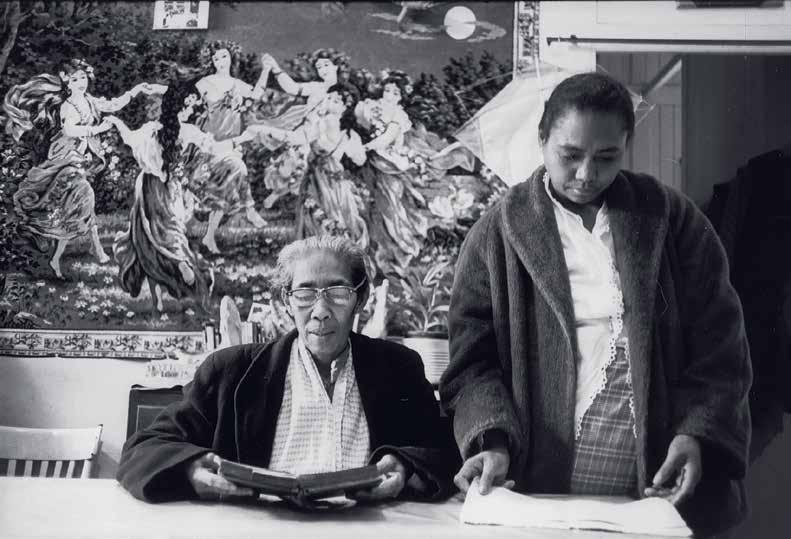

Fig. 5 Moluccan woman from Ambon reading the Bible in her new home in the Netherlands, Leonard Freed, 1962 / 12.6 × 17.7cm, photograph, National Museum of World Cultures collection, inventory no. TM-60059593. © Leonard Freed, Magnum Photos Inc. Friends Lottery (formerly BankGiro Lottery)