light eva fges

PALLAS ATHENE

the sky was still dark when he opened his eyes and saw it through the uncurtained window. He was upright within seconds, out of bed and had opened the window to study the signs. It looked good to him, the dark just beginning to fade slightly, midnight blueblack growing grey and misty, through which he could make out the last light of a dying star. It looked good to him, a calm pre-dawn hush without a breath of wind, and not a shadow of cloud in the high clear sky. He took a deep breath of air, heavy with night scents and dew on earth and foliage. His appetite for the day thoroughly aroused, his elated mood turned to energy, and he was into his dressing room, into the cold bath which set his skin tingling, humming an unknown tune under his breath.

He dressed hurriedly and came back into the bedroom. I’m even ahead of the birds, he thought, standing at the open window one last time, leaning forward with his hands on the sill.

Perhaps there had been a shower in the night, but the air smelled unusually fresh, carrying with it the odour of damp earth and the sweet heavy scent of his roses. No sign of light so far. Good, he thought, I’m ahead of my quarry. Looking down, his garden seemed part of the night, deep in murky shadows, sunk in a dark ocean through which he could just make out the darker outline of trees and shrubs, gathered masses. Below to his left the yew trees were two columns of absolute night, and he could see the ghostly pallor of flowering trellises, bushes, coming through the dark, their colour reduced to nothing. He looked up and saw a last star, it had begun to dim, receding as the sky grew misty, opaque, though dawn was still a long way off. I must go, he thought, noticing a hint of change in the dim luminosity, if I am to catch it. He turned from the window, fumbling in his pocket for cigarettes, and opened his bedroom door. He closed it very quietly, tiptoeing along the passage past his wife’s door, to avoid disturbing her.

He will be gone for hours, she thought, as she heard the floorboard creak outside her room, and then the rhythm of his footfalls down the staircase. It already seemed like hours since she had

first heard him splash about in his dressing room, humming a little tune under his breath, and it would be hours before it was time to get up. No light came through the slats of the shutters, the window was a dim outline. What was the good of him tiptoeing past her room when she had heard him half an hour before through two dressing rooms? When she had told him how she could not sleep? But he forgot everything when he was in a good mood, when he thought the weather promising, both of which she had heard in the sounds which came from his room. She turned in the bed, sighing, slightly peevish and resentful, feeling the empty hours stretch ahead, how the walls and the dark space around her seemed to be closing in, till she felt she could hardly breathe and her head had begun to ache with the pressure. She put her hand to her forehead, now that the familiar throbbing had begun, the little hammer in her skull, I am an old woman, she whispered, moving her hand across her eyes, shutting them, I have begun to outlive my own children, but the soothing dark would not come: what is it about him that gives him the vigour to go off in the small hours as though time had not touched him, as though he was still a young man, no, a child, since he could be as wilful and moody

as a boy? She felt as resentful now, with her head throbbing and her misery, as she had years ago, when she would lie awake worrying in this same bed, several of the children usually sick, and him absent for months on one of his painting trips. She had blamed herself for a fool then, ignoring all the warnings about quitting her class without so much as a wedding ring.

She stared up at the shadowy ceiling, thinking how cruel life is, so very short, but the hours unendurably tedious. Daylight was still far off, but she would not sleep now. Turning uneasily in the bed to stare at a different wall, the irony occurred to her: how had she failed to recognise those bygone years as happy? In spite of all their difficulties, worrying about money, her husband, the endless bouts of measles and feverish colds, Claude going off.

But God was punishing her now. It was back, even though she had tried to put it out of her head. She had been told in confession that it was sinful to think of Him as anything but merciful, but that was the abbé trying to be kind, she felt sure, touching her throbbing head with her fingertips and closing her eyes. She was to blame, she had sinned, and now God was punishing her with this dreadful sorrow.

She stared into the darkness punctured by the sound of a ticking clock. If only she could sleep soundly, she thought, then time would not lie on her as such a heavy burden, weighing on her as her body did, almost all of the time, she must drag it about, it had become heavy as life now, and she would be thankful to lay it down. She closed her eyes to shut out the dim surroundings, and tried to conjure up black, absolute blank, but it would not come.

Now a single bird had begun to call out in the gloom. Hidden on some branch amongst the trees round the garden its sound persisted, echoing through the cool shadowy spaces, rising upward into the dim sky. Soon it was answered by a second cry, more shrill and urgent than the first, and within a short space of time the whole garden was filled with a rising crescendo of birdsong, a frenzy of chirping sound which spilled through the entire valley, still dark, its outline scarcely visible under the sky.

In the kitchen Françoise was a little nervous. This was the first time she had been left to do the master’s breakfast on her own, and she was sure to do something wrong. She tried to go over

the instructions in her mind, but got in a fluster when she could not get the stove to light, even as she heard him moving about in the dining room. Doing everything calmly in the right order, that was the thing, but it would help, my girl, she muttered, if you could get up on time. Cold milk, that was simple enough, and thank God for it, since she had not yet got the knack of making coffee that cook judged drinkable, but had she said he liked his bacon crisp and his eggs a bit soft, or did they have to be cooked right through, with the whites burnt at the edges? Her fingers shook slightly as she tried to catch up on herself. She had been told that he could get in a foul mood if the food was not quite to his liking. Françoise took her hands off the pan handle just long enough to pin back her hair, which had begun to tumble down the nape of her neck, since she had not had time to do it properly when she got up. I must look a sight, she thought. She scooped the curled rashers from the sizzling pan, but one of the eggs broke as she put it on the plate, so that the yoke ran. Merde, she muttered under her breath, but decided it was too late to do anything but take the breakfast in and hope he was in a good mood. Her face flushed, she picked up the tray and took it through to the dining room.

Auguste came up the verandah steps two at a time, tapped on the pane, stood for a moment, knocking his boots for possible traces of mud, and when nobody came, peered through the glass. The kitchen was empty. He knew the door was unlocked without even trying the handle, but he had never yet gone in the house without being asked to do so. Then he saw the new girl come through with an empty tray in one hand, pushing back a strand of hair with the other. She looked a bit flustered, hot and bothered, he thought, with her hair untidy and her cheeks flushed, and she was frowning as she put the tray down and turned to the stove. I don’t suppose she’ll last more than six months, Auguste concluded. He was just about to tap on the glass a second time when she glanced up and saw him outlined against the door. She came to open it, and for the first time noticed the day beginning outside, the dark sky lightening beyond his shoulder, and a din of birds in the trees.

He stood on the verandah and lit his first cigarette, thinking how good it was that the day was only just beginning. The house still lay in shadow, the steep slope of its roof just visible against the fading sky, rows of closed shutters lost in the

dimness, with only his own window open to the indigo sky. So far he could scarcely make out the foliage of the verandah, thick with shadows as it was, but he sensed a different kind of dark in the two yew trees beyond, dense and soft, a texture that seemed to pull all darkness into itself, giving nothing back. They had grown immense over the past few years, but he had been right not to cut them down. Alice’s mood was responsible, when she got over things she would not mind about the yews. After all, it was she who, years ago, had wanted him to keep the two rows of spruce down the central avenue, and if he had the place would have looked like a graveyard by now. No, there was something about those two massive shapes, the inversion of light and colour, a gravity which pinned things down. And if they took too much light from the house, how much time did he spend indoors anyhow? No, he was right, and when she cheered up a little she would see for herself how wrong she had been. If only, he thought uneasily, she would begin to rally.

He flung his cigarette on the gravel. ‘Let’s go,’ he said, seeing the man was ready, equipment slung from both shoulders, in a hurry now, fearful that the light would change before he had got it down. He strode down the path, hearing

his boots crunch on the gravel, with the gardener’s footsteps following behind in an opposing rhythm. He climbed the steps of the footbridge. Below him the railway track gleamed faintly, cutting through the dark land to the far horizon, where the first thin light had just begun to spread upward, no more than a hint of light under the earth. But not enough to touch the surface of the lily pond, it still lay so deep in misty shadows that he could hardly distinguish the outline of the archipelago below. Though he heard his footfalls echo on the bridge, underneath lay a dark unexplored mystery, freshly hidden, between banks he had planned but could not now make out, stretching as far as the willow tree, its curved shape standing out against the sky. He could hear fresh water gurgling through the sluice, a sighing sound run through the long leaves of the willow. He knew, though he could hardly make out their shapes, that the lilies would be closed tight as set pearls in the dark.

He crossed the small wooden footbridge over the narrow stream that marked the bounds of his territory and was out in the open field with the dew now soaking into his trousers as he trod through the high tufted grass. He disturbed a bird which suddenly fluttered up into the dim

sky, startling him, before dipping down out of sight. He had forgotten all about Auguste, trudging behind him, trying to keep up with his load, as he strode through the dim pasture, a world of shadow merging into darker shadow, more obscure shapes. The land fell away to its own secret places, shadow on shadow, fold on fold, whilst the outline of huge trees stood out against the dim sky. He heard only the swish of grasses and undergrowth as his own boots moved through, and the sound of water running in the dark under thick lines of nettle, bramble and willow. He could smell mint now, and damp earth, a cloud of insects swarmed from the reeds as he stepped into the lurching skiff and leaned forward to take the load from Auguste. Then they had pushed off and only the sound of their own movement broke the silence, oars dripping on the smooth surface of the water, the dull grind of the rowlocks, as they glided towards the spot where the studio boat with its cabin was moored.

Once aboard, whilst Auguste began to unpack the canvases, he took stock, glanced round anxiously to make sure nothing had changed. No branches had broken off in the night to change the high outline of trees rising above the riverbanks, or interrupt the smooth surface of the

water. In the bluegrey hush before dawn overhanging trees met their mirror image in still grey water. He thought he had perhaps an hour.

Almost square, a total balance between water and sky. In still water all things are still. Cool colours only, blue fading to mist grey, smooth now, things smudging, trees fading into sky, melting in water. No dense strokes now, bright light playing off the surface of things, small, playful. I have broken through the envelope, the opaque surface of things. Odd that it should have taken so long to reach this point, knowing it, as I did, to be my element. I was blinded, dazzled by the rush of things moving, running tides, spray caught in sunlight. Looking at, not through. The bright skin of things, the shimmering envelope. But now, before the sunrise, no bright yellow to come between me and it, I look through the cool bluegrey surface to the thing itself.

A fish plopped in the stillness, momentarily breaking both the silence and the smooth mirror of the water. Gentle rings rippled outward and died. Auguste, leaning back in the small boat with his hand trailing in the water, wished he could have brought his fishing rod. This was

EVA FIGES, née Unger, was born in 1932 to a prosperous Jewish family in Berlin. Her early childhood was idyllic, but in 1938 her father was sent to Dachau. After his release, the family managed to flee to England, arriving in 1939. She was an avid reader and soon mastered the new language; she graduated in English literature from Queen Mary College, University of London, in 1953, and worked in publishing. Her first novel came out in 1966, and the next year she won the Guardian Fiction Prize with her second, Winter Journey. Another eleven novels followed, including Konek Landing (1969), about a Holocaust survivor unable to come to terms with the present. Her non-fiction included the hugely influential Patriarchal Attitudes: Women in Society (1970), Sex and Subterfuge: Women Writers to 1850 (1982), and an acclaimed trio of memoirs of her early life, Little Eden: A Child at War (1978), Tales of Innocence and Experience: An Exploration (2004), and Journey to Nowhere (2008). Married in 1954, she had two children, the writer Kate Figes and the historian Orlando Figes. Eva Figes died in 2012.

First published 1983

First Pallas Athene edition published 2005. Tis new edition, entirely reset and revised, first published 2024 and reprinted twice in the same year.

Text and punctuation from the original 1983 edition

Pallas Athene (Publishers) Limited

2 Birch Close, Hargrave Park, London N19 5XD

© Te Estate of Eva Figes 1983, 2005, 2024

Te right of Eva Figes to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act

ISBN 978 1 84368 243 1

www.pallasathene.co.uk

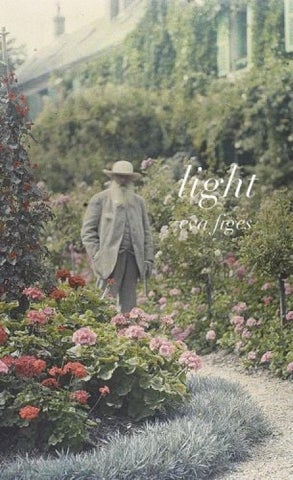

Cover: Colour photograph of Monet in his garden taken in 1921 for L’Illustration magazine by an unknown photographer using the Autochrome process

Printed in England by TJ Books Limited, Padstow, Cornwall