7

FOREWORD: A FEELING OF AFFINITY

Patrick K M Kwok 郭建明

11

KINDRED SPIRITS: JAPANESE CERAMICS IN CHINESE STYLE

Clare Pollard

37

CHINESE INSPIRATION FOR JAPANESE CERAMICS IN THE MEIJI, TAISHŌ AND EARLY SHŌWA PERIODS

Rose Kerr

51

DRAWING FROM THE OLD TO CREATE THE NEW: A CHINESE-STYLE ‘PALACE LANDSCAPE’ VASE BY MIYAGAWA KŌZAN

Clare Pollard

69

SUWA SOZAN I, II AND III: MASTERS OF JAPANESE CELADON Maezaki Shinya 前﨑信也

87

A HISTORIOGRAPHY OF JAPANESE CERAMICS IN CHINESE STYLE: JAPANESE AND WESTERN SCHOLARSHIP Fukunaga Ai 福永愛

103

CATALOGUE: 100 JAPANESE CERAMICS IN CHINESE STYLE

Clare Pollard, with contributions by Patrick K M Kwok, Itō Mitsuko, Maezaki Shinya, Fukunaga Ai and Yamamoto Hiroshi

105 Suwa Sozan I (1851–1922)

162 Suwa Sozan II (1890–1977 )

176 Suwa Sozan III (1932–2005)

179 Miyagawa Chōzō (1797–1860) (Makuzu Chōzō)

182 Miyagawa Kōzan I (1842–1916) (Makuzu Kōzan)

214 Miyagawa Kōzan II (1859–1940) (Miyagawa Hanzan, Makuzu Kōzan)

232 Miyagawa Kōzan III (1881–1945) (Makuzu Kōzan)

239 Seifū Yohei I (1801–1861)

244 Seifū Yohei II (1844–1878)

248 Seifū Yohei III (1851–1914)

260 Seifū Yohei IV (1872–1951)

268 Seifū Yohei V (1921–1991)

271 Itō Tōzan I (1846–1920)

276 Itō Tōzan II (1871–1937 )

281 Itaya Hazan (1872–1963)

285 Miura Chikusen I (1854–1915)

296 Miura Chikusen II (1882–1920)

298 Miura Chikusen III (1900–1990) (Miura Chikken)

305 Kiyomizu Rokubei V (1875–1959)

309 Miyanaga Tōzan I (1868–1941)

314 Miyanaga Tōzan II (1907–1994)

317 Takahashi Dōhachi II (1783–1855) (Nin’ami Dōhachi)

321 Wake Kitei IV (1826–1902)

325 Eiraku Zengorō XIV (1853–1909) (Eiraku Tokuzen)

328 Eiraku Zengorō XIV (1852–1927 ) (Eiraku Myōzen)

330 Eiraku Zengorō XVI (1917–1998) (Eiraku Sokuzen)

335 Katō Keizan I (1886–1963)

340 Inoue Kengo (active 1920 s–1930 s)

343 Kawase Chikushun II (1923–2007 )

CATALOGUE: 100 JAPANESE CERAMICS IN

CHINESE STYLE

Suwa Sozan I (1851–1922)

Incense burner in the form of a shishi lion dog

Porcelain with celadon glaze, moulded and carved

IMPRESSED MARK : 蘇山, Sozan

DATE : c. 1910 –1920

HEIGHT: 18 5 cm

Shen Zhai Collection 1–26 (91)

BOX INSCRIPTION :

青瓷 / 獅子香炉 / 蘇山, seiji shishi kōro Sozan (celadon shishi incense burner, Sozan)

SEAL : 蘇山造之, Sozan kore o tsukuru

This fierce-looking celadon-glazed incense burner is a Japanese interpretation of a classic Chinese subject. Figures of mythical lion dogs, often made in pairs, have traditionally stood as guardians in front of Chinese imperial palaces, tombs, temples and the homes of the rich and powerful. Originally made of stone, celadon examples exist from as early as the Song dynasty. Often strikingly stylised with vigorous modelling, such Song prototypes may have served as inspiration for this Sozan version, although there were also Japanese precedents: the motif had been introduced to Japan in the 12 th century, becoming known as karashishi (Chinese lion dog), and celadon ornaments were made from the 18 th century in Nabeshima and Arita.

This shishi stands tall on straight legs, gazing straight ahead. The figure has been first moulded and then carved to emphasise details such as the luxuriantly curling fur. The entire figure has been glazed except for the claws, which provide a striking contrast. The lid is also made of glazed celadon, rather than out of metal.

Similar works are illustrated in the memorial catalogue Sozan no tōki (1923) and the exhibition catalogue Suwa Sozan sakuhinshū: shodai, nidai, sandai (1971), p. 68

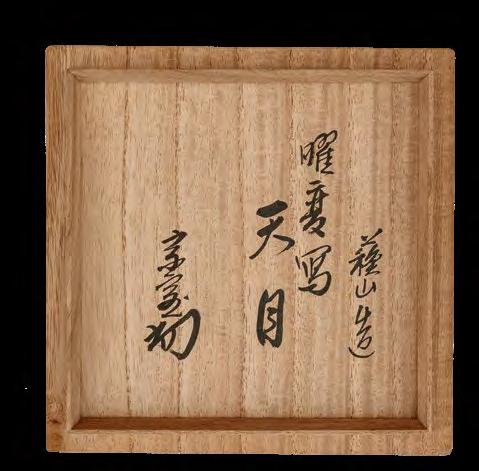

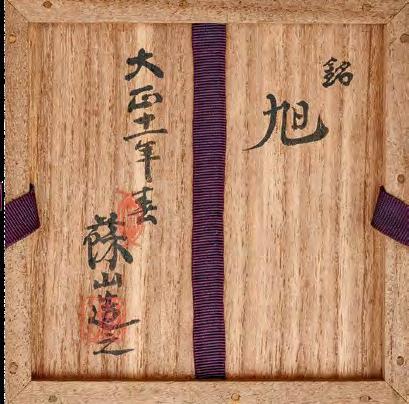

Suwa Sozan I (1851–1922)

‘Asahi’ (Rising Sun), tenmoku tea bowl

Stoneware with tenmoku glaze

IMPRESSED MARK : 蘇山, Sozan

DATE : Spring 1922

HEIGHT: 12 5 cm

Shen Zhai Collection 1–16 (57 )

BOX INSCRIPTION (by Tantansai Mugensai

Sekisō):

VERSO : 蘇山造 / 曜変写 / 天目 / 宗室, Sozan zō yōhen sha tenmoku Sōshitsu (made by Sozan in imitation of transmutation tenmoku [glaze], Sōshitsu)

BASE : 銘 / 旭 / 大正十一年春 / 蘇山造之, mei Asahi Taishō jūichi nen haru Sozan kore o tsukuru (named ‘Asahi’, made by Sozan, spring 1922)

SEALS : 精, sei, and 蘇山, Sozan

INNER BASE : 陽変 / 天目茶盌, yōhen tenmoku chawan (yōhen tenmoku tea bowl)

SEAL : 帝室技芸員, teishitsu gigeiin

This tea bowl for the matcha tea ceremony is decorated with a lustrous black tenmoku glaze, with dramatic pale streaks. While Sozan was best known for his celadon works, he also created a variety of other classic Chinese ceramics, including Songstyle tea bowls like this one. Tenmoku tea bowls were first brought back from Mount Tianmu in China by Japanese Zen Buddhist monks during the Kamakura period and were highly prized by Japanese tea masters for their glossy dark glazes, which provided a pleasing contrast to the green whipped tea. From the 14 th century, Japanese versions were being produced in Seto. This bowl is named ‘Asahi’, or ‘Rising Sun’, likening the iridescent streaks of yōhen transmutation glaze in the interior to rays of sunshine. As Sozan contracted influenza on 5 January 1922 and died on 8 February, this must have been one his final works.

The original Sozan-inscribed box for this bowl has been reconstructed so that its cover has become the base of a new box. The new box is inscribed by the 14 thgeneration master of the Urasenke tea school Tantansai Mugensai Sekisō (1893 –1964), thereby endorsing the tea bowl and honouring its maker.

This bowl is published in the memorial catalogue Sozan no tōki (1923), and a similar bowl, dated to 1921, is illustrated in the exhibition catalogue Suwa Sozan sakuhinshū: shodai, nidai, sandai (1971), p. 63

Miyagawa Kōzan I (1842–1916)

(Makuzu Kōzan)

Incense burner with lid and stand, decorated with sea dragons amidst waves, shishi lion dogs, peonies and hōō birds; standing on a tripod base composed of three elephant heads

Porcelain with moulded decoration and painting in underglaze blue and red

PAINTED MARK (VASE) : 真葛香山製, Makuzu Kōzan sei

PAINTED MARK (STAND) : 真葛香山製, Makuzu Kōzan sei

DATE : c 1900 –1910

HEIGHT: 31 cm

Shen Zhai Collection 7–16 (150)

BOX INSCRIPTION :

RECTO : 香爐, kōro (incense burner)

VERSO : 依雍正年手 / 真葛窯 / 香山造, i yōsei nende Makuzu yō Kōzan zō (based on Yongzheng period style / made by Makuzu Kōzan at the Makuzu kiln)

SEAL : 真葛香山, Makuzu Kōzan

This elaborate lidded jar rests on a tripod base made up of three elephant heads. A series of holes pierced in the lid and perforations in the crown-like finial allow the jar to function as an incense burner. The body of the jar is decorated in underglaze blue in a finely painted design with two roundels, one on the front and one on the back, each containing fullfrontal, four-clawed dragons executed in underglaze copper red among swirling waves of underglaze blue. Around the roundels are shishi lion dogs, peonies and hōō birds depicted in reserve among scrolling foliage, and rows of lappets at the top and base of the jar.

The box inscription states that this incense burner is made in the style of Yongzhengperiod (1723 –1735) porcelain, considered among the finest of all Qing porcelains. The work displays multiple Chinese references. The motif of a red dragon amidst blue waves is a classic imperial Chinese theme, while the handles are topped with moulded taotie monster masks. Even the marks on the base of the vessel and stand are inscribed in the style of the imperial Yongzheng six-character imperial reign mark, within a double circle. The unusual crown-like finial might be Europeaninspired, as the Yongzheng emperor was known to have an interest in the West and collected foreign art objects.

The moulded elephant base alludes to a number of Chinese precedents, going back to Tang white-glazed candle stands and Yuan greenware incense stick holders. Elephants were modelled in bronze as early as the Shang dynasty (c. 1500 –c. 1050 BCE), while gilt bronze censers on three- or five-elephant-head tripod bases were popular during the Qianlong period. The lid, with its lobed finial and rings, also recalls metalwork.

A very similar Kōzan vase, in underglaze blue only, was presented to the Victoria and Albert Museum by Lieutenant Colonel Kenneth Dingwall in 1910 (C.246 to B-1910).

Miyagawa Kōzan I (1842–1916)

(Makuzu Kōzan)

Vase with a dragon in clouds

Porcelain with underglaze red

PAINTED MARK : 真葛窯香山製,

Makuzu gama Kōzan sei

DATE : Mid 1890 s

HEIGHT: 15 8 cm

Shen Zhai Collection 7–12 (126); ex Tanabe Tetsundo Collection

A four-clawed dragon curls around the body of this baluster vase, depicted in dark copper red under a clouded pinkish-red glaze. The dragon is rendered with great animation, and the red pigment of the background has been skilfully applied to create the effect of clouds swirling around the dragon. This would have been achieved by the fukie (blown picture) technique, whereby ink is sprayed over a masked area.

The vase is datable from its mark to the mid 1890 s, when Kōzan was perfecting a range of Qing-inspired porcelain styles in place of the enamelled and modelled works he had produced during the 1870 s and early 1880 s. The use of reduction-fired copper oxide to create red glaze effects was first seen on Chinese stonewares made at the Tonghuan kilns near Changsha towards the end of the Tang dynasty and was developed for porcelain decoration at Jingdezhen during the Yuan dynasty (1279 –1368). Richly glazed copper-red monochrome porcelains were perfected during the Yongle (1403 –1424) and Xuande (1426 –1435) reigns of the Ming dynasty. However, technical difficulties in firing volatile copper pigment made it prone to discolouration and blurring in areas of painted design, and as a result its use was virtually abandoned by the mid 1400 s. Monochrome copper-red vessels were only revived on a grand scale about two centuries later during the Kangxi period (1662–1722), for the Kangxi emperor, who revived the imperial kilns and encouraged the imperial potters to experiment, improve and rediscover. A range of copper-red glazes was developed at the imperial kilns at Jingdezhen by the kiln supervisor Lang Tingji (1663 –1715). These ranged from the deep-red oxblood to the softer peachbloom, achieved by sandwiching a sprayed layer of copper pigment between two layers of clear glaze.

When Kōzan developed his Qing-style copper-red glazes, he was also aware of the current fascination with Chinese monochrome porcelains in the West. Increased diplomatic contact with China and Chinese participation at the international exhibitions made its ceramics more accessible around the world, especially after the looting of the emperor’s Summer Palace in Beijing in 1863 released a large number of Chinese imperial porcelains onto the market. Collectors such as William Walters paid astronomical sums for exquisite Chinese vases, and extensive scientific research into the creation of Chinese glaze effects was undertaken at Sèvres, Limoges, Royal Copenhagen and many other ceramic centres in Europe and the United States during the 1880 s and 1890 s. From Kōzan’s surviving workshop notebooks it is clear that he conducted countless experiments with underglaze red. Although inspired by Chinese originals, a number included imported European chemical ingredients.

Published: Tanabe Tetsundo, Teishitsu gigeiin Makuzu Kōzan (Tokyo: Sōbunsha, 2004), p. 163, no. 129.

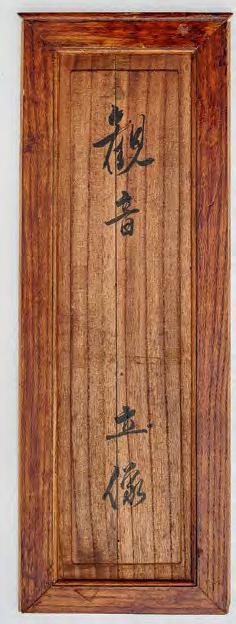

Miyagawa Kōzan I (1842–1916)

(Makuzu Kōzan)

Standing figure of the bodhisattva Kannon, in hakugōrai style

White porcelain, moulded and glazed IMPRESSED MARK : 真葛香山, Makuzu Kōzan

DATE : 1903 –1916

HEIGHT: 43 5 cm

Shen Zhai Collection 7–5 (73)

BOX INSCRIPTION :

RECTO : 観音 立像, Kannon ritsuzō (standing figure of Kannon) VERSO : 白高麗 意 / 真葛香山作, hakugōrai i Makuzu Kōzan saku (made by Makuzu Kōzan, in hakugōrai style)

SEALS : 帝室技芸員, teishitsu gigeiin, and 真葛香山, Makuzu Kōzan

This figure of the bodhisattva Kannon stands serenely on a lotus pedestal, her eyes cast down, with her right hand held up in the mudra of fearlessness and her left hand holding a water jar. On her head she wears a crown decorated with a small image of Amida Buddha. The details of her costume and accessories have been finely carved and applied after moulding.

The figure is inspired by blanc de Chine porcelain examples made at Dehua in Fujian province from the Ming dynasty and exported to Japan in large quantities before the mid 17 th century. A large proportion of these Dehua exports to Japan were Buddhist images and ritual utensils. The bodhisattva Kannon, known as Guanyin in Chinese, was particularly revered in Fujian and was one of the most popular subjects of Dehua porcelain. In Japan blanc de Chine was known as hakugōrai, which can be translated as ‘Korean white ware’ but simply denoted white porcelain from the Asian continent. Japanese versions were soon being produced at the Hirado kilns

and elsewhere. Hakugōrai ivory-white porcelain was introduced to the Makuzu workshop by the potter Itaka Kizan I (1881–1967 ), who had developed the technique at the Izushi kilns in Hyōgo prefecture before becoming apprenticed to Kōzan in 1903 . Indeed, Kōzan’s workshop notes show that he was experimenting with Izushi clay around this time.

The subject of Kannon was one that Kōzan returned to periodically throughout his career. According to his personal history, he displayed an eleven-headed figure of the bodhisattva Kannon at the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition of 1876, while a white porcelain figure of Kannon was shown by Augustus Franks in an exhibition at Bethnal Green in 1878 and is now in the British Museum. An obituary of Kōzan in the trade journal Yokohama bōeki shinpō of 5 July 1916, records that in his final years he was creating a set of reproductions of the eleven-headed Kannon held in Komyōji Temple in Kamakura but died after starting work on the first twenty-five. One of these figures was apparently presented to Komyōji in accordance with Kōzan’s wishes, and the remaining twenty-four, only half finished, were given to family and friends. Hanzan also produced a number of Kannon figures after his father’s death.

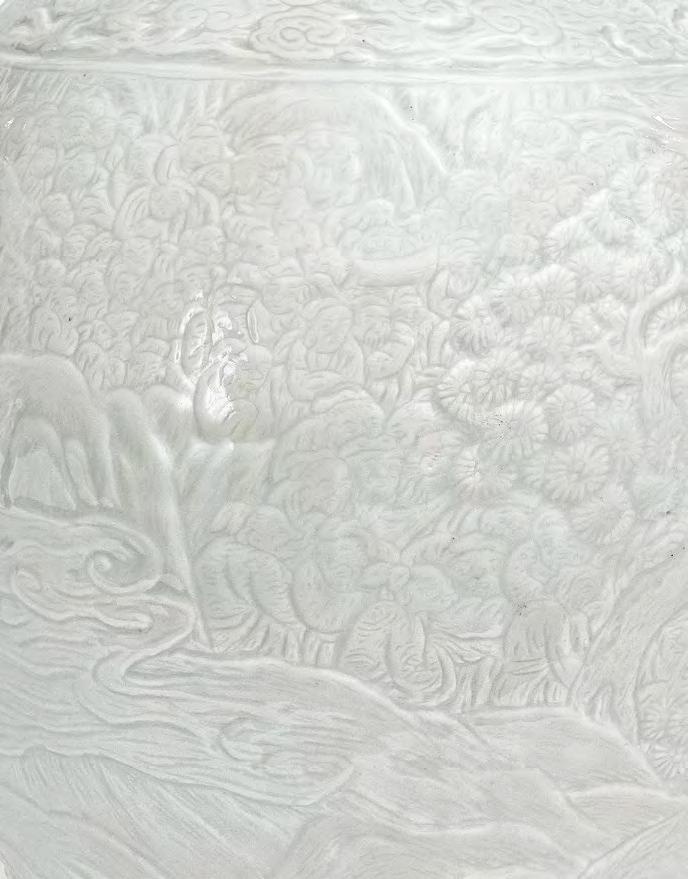

Seifū Yohei V (1921–1991)

Jar with carved figures under trees

Porcelain, moulded and carved, with white glaze

INCISED MARK : 清風造, Seifū zō

DATE : 1971–1991

HEIGHT: 31 cm

Shen Zhai Collection 22–1 (133)

This white porcelain has been moulded and extensively carved with a scene of pine trees sheltering numerous Chinese scholar-like figures before the white glaze was applied. The vase recalls Yohei III’s renowned taihakuji works, such as a famous vase with peonies and butterflies moulded in low relief that was exhibited at the World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago in 1893 and is now in the Tokyo National Museum (G-124). Yohei V may have been inspired by incised Qingbai ‘blue-white’ or ‘green-white’ porcelain of the Song and Yuan dynasties or by 12 th-century Ding ware, with its carved floral designs.

Miyanaga Tōzan I (1907–1994)

Figure of a Japanese ox

Porcelain, moulded, glazed and carved IMPRESSED MARK : 東山, Tōzan

DATE : c 1910 –1930 s

LENGTH : 27 cm

Shen Zhai Collection 20 –2 (85)

BOX INSCRIPTION :

RECTO : 和牛置物, wagyū okimono (ornament of a Japanese ox)

VERSO : 東山, Tōzan

SEAL : 東山, Tōzan

The ox is one of the twelve animals in the Chinese lunar calendar, and three-dimensional oxen and water buffalo (considered the same category of animals in China) have been created by Chinese artists for 3,000 years, whether in bronze and jade during the Shang dynasty, in sancai three-coloured earthenware during the Tang dynasty or in overglaze enamelled porcelain in the 18 th century. Tōzan’s naturalistically modelled version, with its rich, dark-brown glaze, may have been made for an ox year. It is interesting that Tōzan specifies that this is a Japanese ox.

Eiraku Zengorō XIV (1852–1927 )

(Eiraku Myōzen)

Pair of sake bottles with sometsuke Chinese boys (karako)

Porcelain with sometsuke underglaze blue

IMPRESSED MARK : 永楽, Eiraku

DATE : c. 1910 s–1920 s

HEIGHT: 16 cm

Shen Zhai Collection 15 –13 (104)

BOX INSCRIPTION :

染附唐子 / 酒瓶 一対 / 善五郎造, sometsuke karako shubin ittsui Zengorō zō (pair of sake bottles with Chinese boys in sometsuke underglaze blue, made by Zengorō)

SEALS : 永楽, Eiraku, and 悠, Yū

These two sake bottles by Eiraku Myōzen, wife of Eiraku Zengorō XIV, show a modern Japanese interpretation of traditional Chinese styles and motifs. Each bottle shows a pair of karako Chinese boys dancing, depicted in reserve against a karakusa Chinese grasses scroll pattern. The Chinese inscriptions around the neck of the bottles are, appropriately, verses of self-improvement from the ‘Child Prodigy Poem’ by Northern Song-dynasty poet Wang Zhu.