DIRECTOR’S NOTE

In 2024, Museum Plantin-Moretus is devoting special attention to the work of James Ensor. But what does Ensor have to do with Antwerp? And what links Ensor to this particular institution, dedicated to the printing house ran by nine generations of the Plantin and Moretus family, started by Christopher Plantin? The family provided their luxurious printed matter with illustrations of the very highest quality. Today, the museum collects graphic work by important artists from the fifteenth to the twenty-first century, including more than 200 works on paper by Ensor.

By 1550, Antwerp had become the artistic capital of the Southern Netherlands, the “most modern” market in Europe and a trading and export hub for luxury goods, including prints. The work of Antwerp print publishers Hieronymus Cock and Philips Galle is still considered among the best in printmaking today. They published works by Hieronymus Bosch, Frans Floris, Pieter Bruegel and Maerten de Vos, which were distributed to the far corners of Europe and the Spanish Empire. In this, Christopher Plantin played a crucial role. He purchased countless prints from major Antwerp publishers and shipped them, along with his books, to his international clients. In those far-flung corners of the world, they served as inspiration for local artists. Prints were an early form of mass communication. Peter Paul Rubens saw the immense value of prints in positioning himself as a great inventor of dramatic compositions. A painting could only be seen in one place; an engraving reached hundreds of recipients. This graphic work was certainly not dismissed

Iris Kockelbergh, Director Museum Plantin-Moretus

by Rubens as a second-rate product. Making copper engravings was a highly specialised craft, and Rubens worked only with the best engravers, so that the prints would approach the incomparable pictoriality of his paintings. Like Ensor, Rubens was fascinated by the way black and white could capture light: moonlight on the surface of water, a rainbow, or torrential rains.

While engraving is the work of trained craftsmen from start to finish, artists can draw on the prepared surface of an etching plate themselves. For his famous Iconographie, the internationally renowned portrait painter Anthony van Dyck drew portraits of statesmen, scholars and artists, among others, directly on the etching plate. He then had the background finished by an engraver. The most important etcher of the seventeenth century was, of course, Rembrandt. His talent to capture light and shadow, substance and drama in an etching is still unrivalled.

Ensor looked to the examples of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, primarily Bruegel and Rembrandt. He also approached his graphic work as an independent medium within his oeuvre, focusing on landscapes, portraits, cityscapes, drolleries, masks, still lifes and more. In doing so, he continued a great and long tradition of an art form in which the Low Countries have always been strong, and which deserves more attention, both for the oeuvre of all those great masters and for future engravers and etchers. The Print Room of the Museum Plantin-Moretus contributes to this end with projects such as Ensor’s States of Imagination.

KBR – Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels, inv. S.IV 29323 T. 67

plates by Ensor in his possession.27 In 1955, antiquarian Paul Van der Perre (1895–1970) stated that Evely’s estate contained two of Ensor’s prints on satin.28

A hunt for rare prints, which were quite popular among collectors, had sprung up in the nineteenth century in several countries in Europe, starting with France. Artists and their printers capitalised on this by printing small editions, for example, or on special paper, thereby making their prints into unique pieces.29 This obviously served financial ends – after all, artists and publishers could charge a higher price for scarce or unusual prints. Ensor’s prints on special supports, as well as his prints in coloured ink, and even a counterproof (fig. 21) were entirely in step with the times. Due to the diverse supports and inks, each impression has a very different character. (figs. 19, 20 and 22)

A personal path

Ensor wrote in his letters to Mariette that he was especially fond of shades of grey, but also how difficult he found etching them.30 “Without effort, it doesn’t work! Especially in etching,” he wrote. “Experience is lacking and does not come without effort and repeated attempts.”31 Indeed, more than with drawing and painting, he said, a copper plate could be used “for a variety of investigations and processes”.32 And he would only be able to successfully publish the prints, he wrote, after having mastered the difficulties of etching.33

In 1890, Ensor wrote – perhaps not entirely correctly – to the poet Valère Gille (1867–1950) that he knew nothing about the profession of etching: “I can draw and engrave well and then chance takes over. I cannot conform to all the fine, meticulous tricks of the trade.”34 Yet, in a creative process, it is precisely chance that often makes the results so characteristic. Creation does not entail working towards a definite goal, but is a process of trial and error, failure and trying anew, and in this way mastering techniques.35

19

Village Fair at the Windmill, 1889

Etching and drypoint (copper), 135 × 174 mm

State II/II, printed on ivory satin

Collection P.F. T. 72

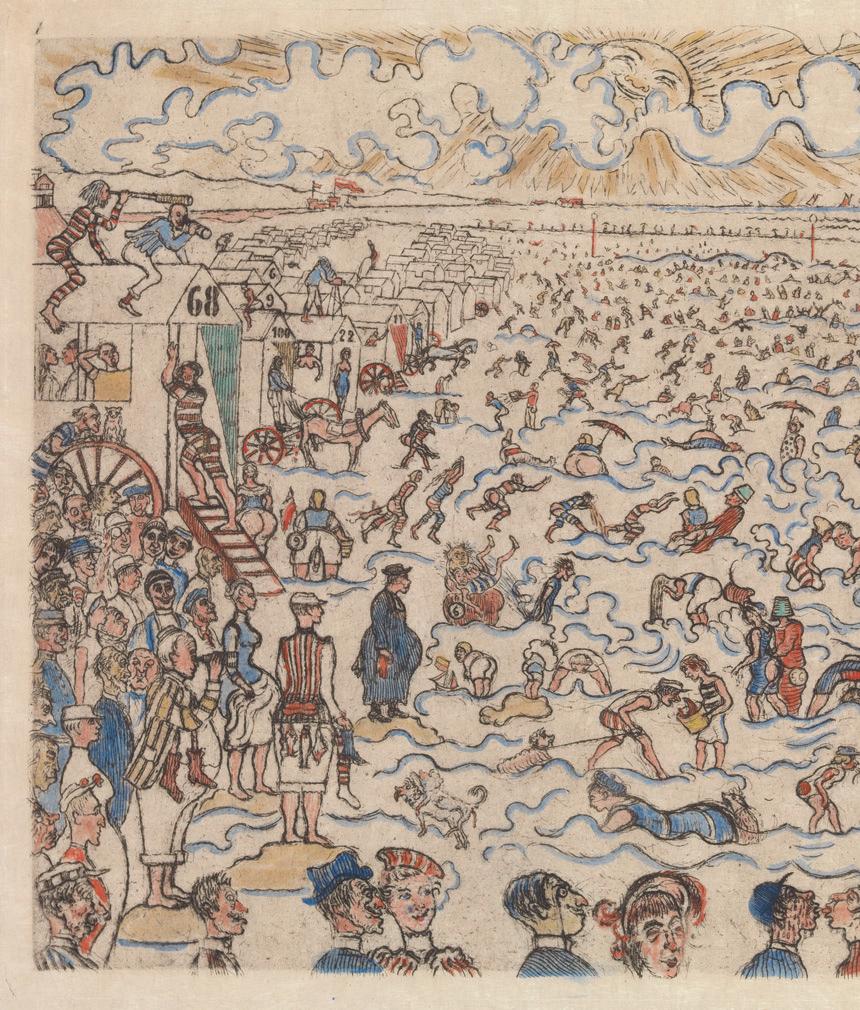

20

Village Fair at the Windmill, 1889

Etching and drypoint (copper), 135 × 174 mm

State II/II, printed in red ink

Collection P.F. T. 72

FIG. 21

Village Fair at the Windmill, 1889

Counterproof, 135 × 174 mm

State II/II

Collection P.F. T. 72

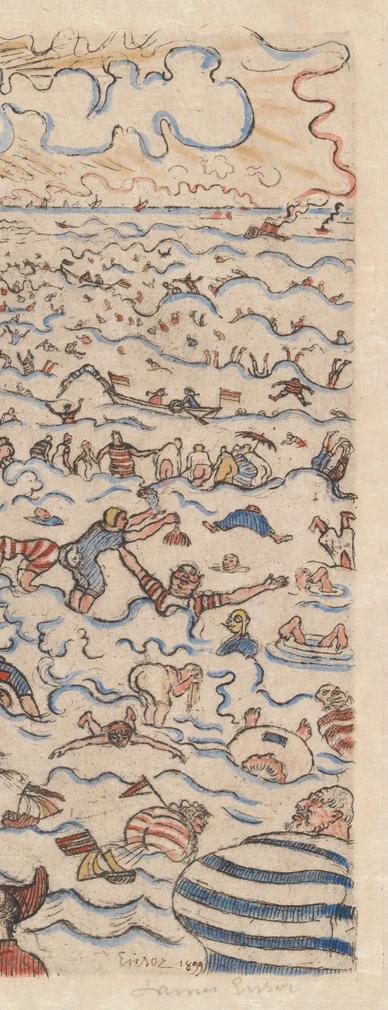

FIG. 22

Village Fair at the Windmill, 1889

Etching and drypoint (copper), 135 × 174 mm

State II/II, hand-coloured with transparent and opaque watercolour

Private collection T. 72

FIG. 31 Pride, 1903 Etching (copper), 93 × 146 mm State III/III, hand-coloured with transparent watercolour Museum PlantinMoretus, Antwerp, inv. PK.MP.04981 T. 122

Ensor continued to draw with drypoint in the sky for the second state (fig. 53), but eventually scraped the burrs off the plate again until only thin grooves remained, and the final state was printed (fig. 54).30

In The Thunderstorm (fig. 55), Ensor used a different tonal technique. After etching the landscape, he cleaned the copper plate, covered the landscape, and obscured the light areas in the sky with stopping-out varnish. Light, slanted stripes can be seen in the upper right (fig. 56) and light horizontal stripes in the upper left. In those areas, the plate had not been properly wiped clean. Therefore, some etching ground still remained in the form of streaks, which was just enough to hold up for a while during the etching process. Ensor etched the plate briefly so that the remaining etching ground still held back the acid. This produced an irregular tone in the print. The bite was shallow; after a few impressions this began to wear off and the tone became lighter (fig. 57)

FIG. 51

Detail of fig. 52, The Stars in the Cemetery, 1888

Aquatint and drypoint (copper), 140 × 180 mm

State I/III

Museum PlantinMoretus, Antwerp, inv. PK.MP.04885

T. 56

FIG. 52

The Stars in the Cemetery, 1888

Aquatint and drypoint (copper), 140 × 180 mm State I/III

Museum PlantinMoretus, Antwerp, inv. PK.MP.04885

T. 56

FIG. 53

The Stars in the Cemetery, 1888

Aquatint and drypoint (copper), 140 × 180 mm

Early impression of state II/III, with extra drypoint lines and still a lot of burr Collection P.F.

T. 56

FIG. 54

The Stars in the Cemetery, 1888

Aquatint and drypoint (copper), 140 × 180 mm

State III/III, with scraped off burrs Museum of Fine Arts, Ghent, inv. 1998-B-56

T. 56

Skaters, 1889 Etching and aquatint with

176

232 mm State II/II Museum PlantinMoretus, Antwerp, inv. PK.MP.09485 T. 65

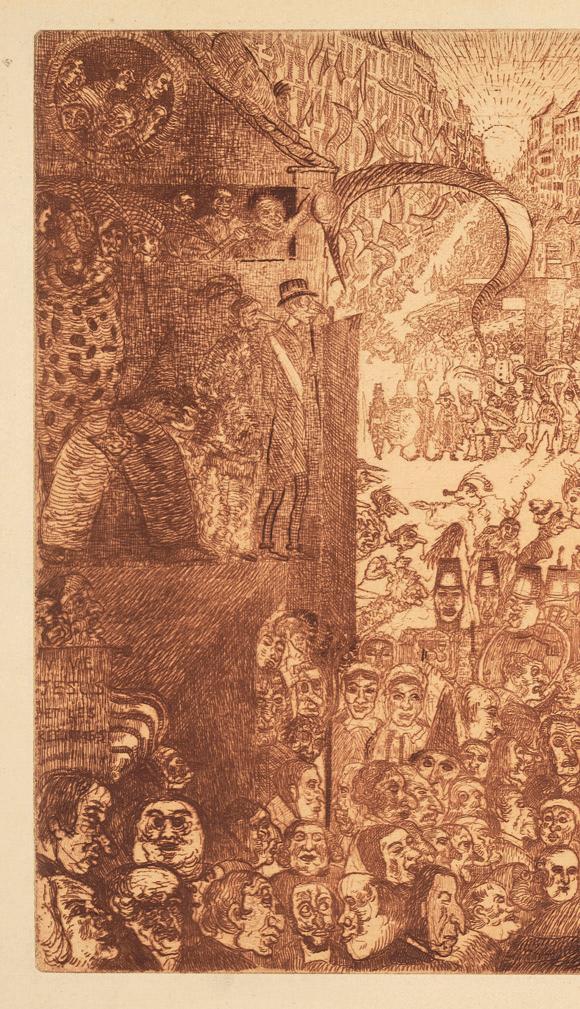

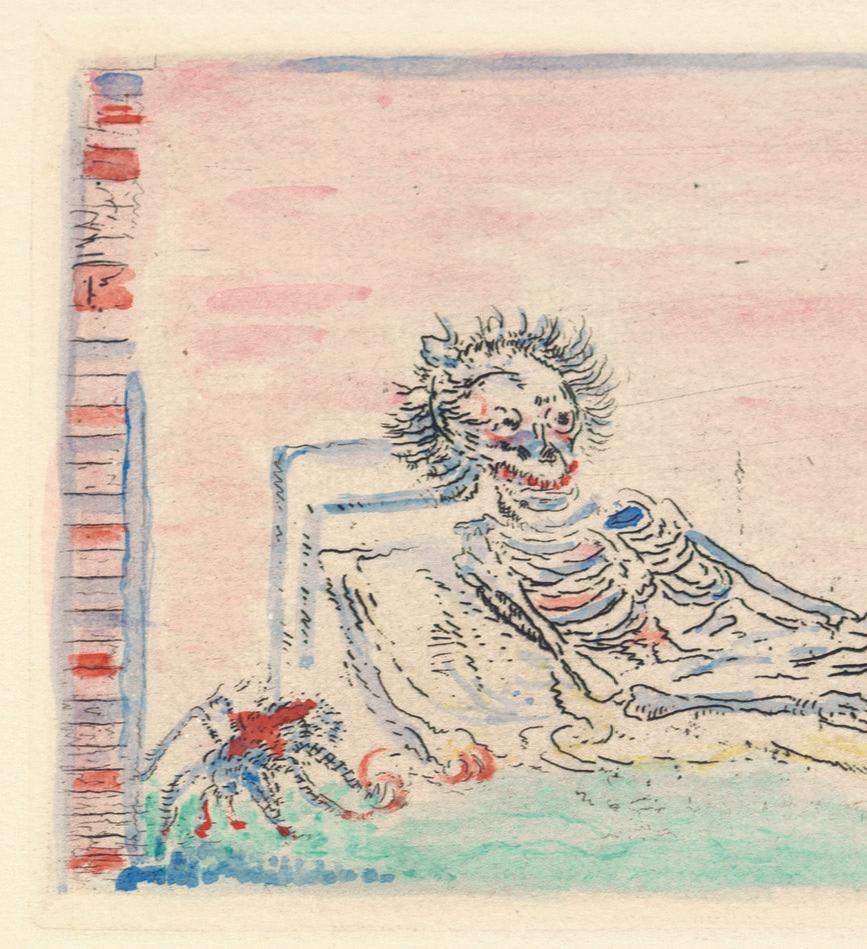

DETAIL FIG. 99

Death Chasing the Flock of Mortals, 1896 Etching (copper), 235 × 175 mm State II/III, hand-coloured with transparent watercolour

Private collection T. 104