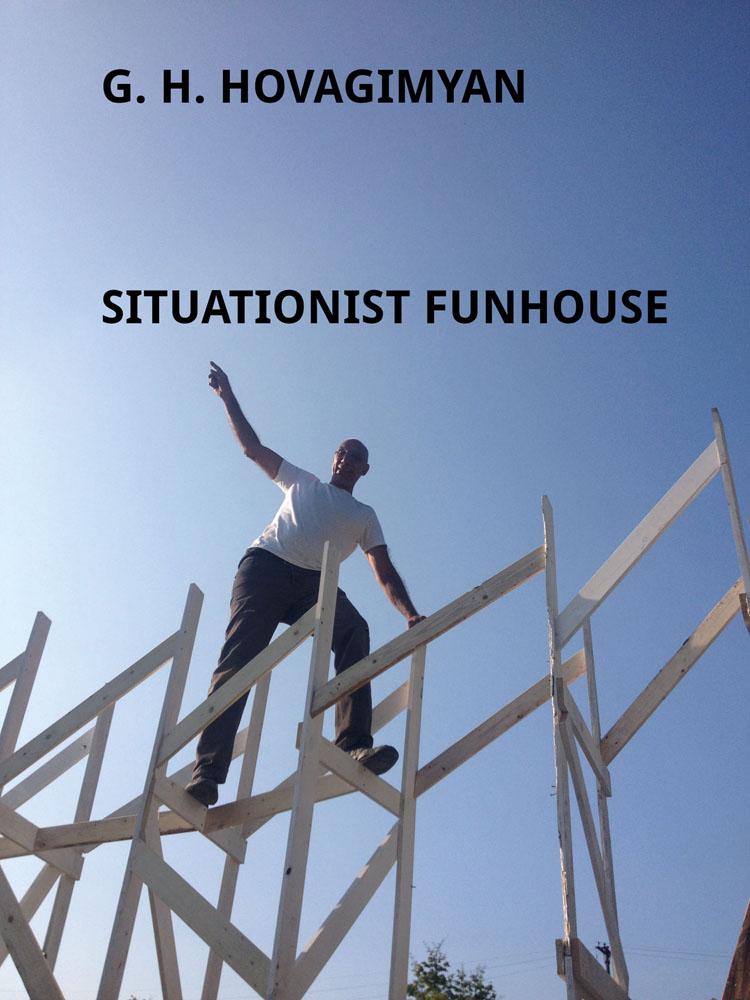

CONTENTS

Foreword by Amanda McDonald Crowley / 8

Introduction / 12

1. Early Collaborations / 16

Rafael Ferrer, Three Leaf Pieces, 1968 / 17

112 Greene Street / 20

Robert Bell and Richard Serra, Prisoner’s Dilemma, 1974 / 22

Gordon Matta-Clark, 1975–76 / 24

Day’s End, 1975 / 25

Conical Intersect, 1975 / 27

Salvatore Ala Gallery and Arche Du Triomphe for Workers (unrealized), Milan, 1975 / 28

Substrait [Underground Dailies], 1976 / 31

597 Group, 1975 / 31

Videotapes and Performances, The Kitchen, February 1975 / 32

Loft Show, 597 Broadway, Spring 1975 / 34

Colab, 1977–79 / 37

The Communists, punk/No Wave band, 1977–1978 / 44

Virtual Garrison Gallery, 19 2nd Avenue at 1st Street, 1984–1985 / 51

2. Early Work / 58

Control Designators, 112 Greene Street, Sep. 21–Oct. 3, 1974 / 59

About 405 E. 13th Street, Apr. 18–21, 1974 & Jun. 10–20, 1975 / 61

Scale 1/1, James Yu Gallery, May 1975 / 63

Thought Models, Idea Warehouse, Jun. 11–12, 1975 / 64

Rubber Room, P.S. 1, Mar. 24–Apr. 10, 1977 / 65

Rich Sucker Rap, Artists Space, 1977/Chant à Capella, Jean Dupuy and Davidson Gigliotti, Museum of Modern Art, 1978 / 67

A Tower at P.S. 1, February 1978 / 69

75 Warren Street, Jan. 6–Feb. 1, 1979 / 70

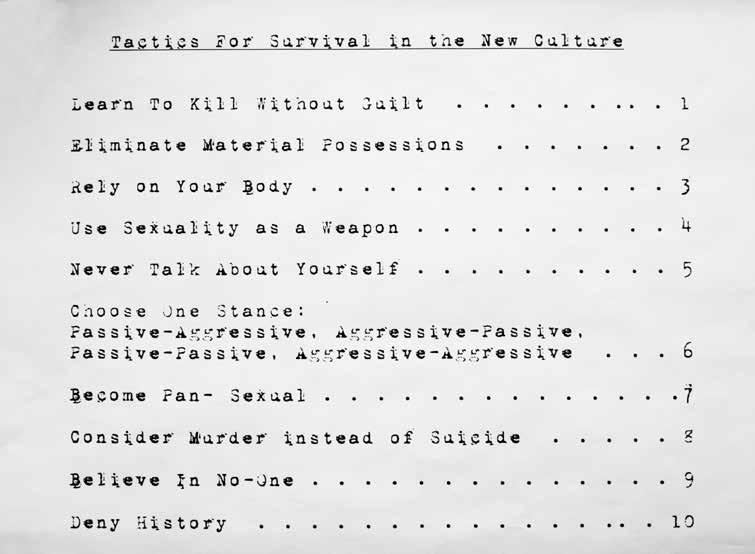

Tactics for Survival in the New Culture, Manifesto Show, Colab, Apr. 1979 / 70

Excerpts from a Novel, 112 Workshop, Apr. 24, 1980 / 73

3. Net Art / 74

BKPC (Barbie and Ken Politically Correct), The Thing, 1993, 1995 / 75

Terrorist Advertising, Bowery & 5th Street, Sep. 23, 1993–Feb. 23, 1994 / 79

Hey Bozo, Use Mass Transit, MTA Arts for Transit & Creative Time, Apr.–May, 1994 / 80

Surveys & Questionnaires, Gallery 128, 1994 / 86

Faux Conceptual Art, artnetweb, 1993-1995 / 92

Art Direct/ Sex Violence Politics, Thing.net/artnetweb, 1995 / 94

Barbie and Ken Politically Correct / 96

Flowers & Ecstasy / 96

Pray for Death / 98

Sacred & Profane / 98

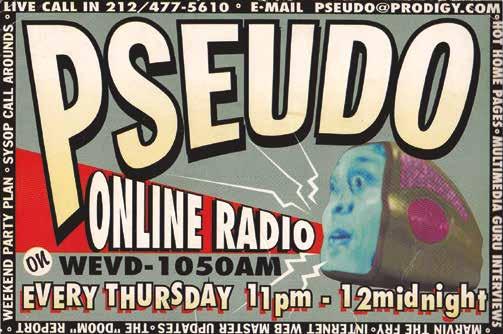

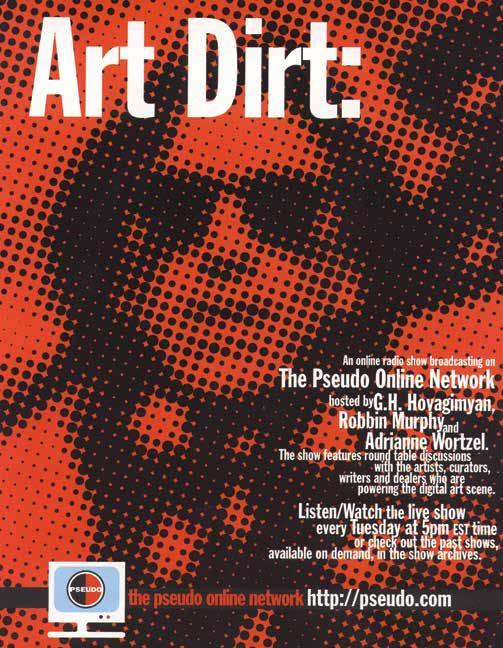

Art Dirt, Pseudo Online Radio/ Collider, The Thing, 1995–1998 / 100

Art Dirt Im-Port, Port MIT: Navigating Digital Culture, MIT List Visual Arts Center, Jan. 25–Mar. 29, 1997 / 105

Complete Art Dirt Im-Port Lineup / 111

4. Multimedia Performances / 112

A Soa(p Op)era for Laptops, 1997–1999 / 113

A Soa(p Op)era for iMacs (with Peter Sinclair), 1999–2005 / 118

Heartbreak Hotel (with Peter Sinclair), 2000 / 122

Shooter (with Peter Sinclair), Eyebeam, 2001–2002 / 125

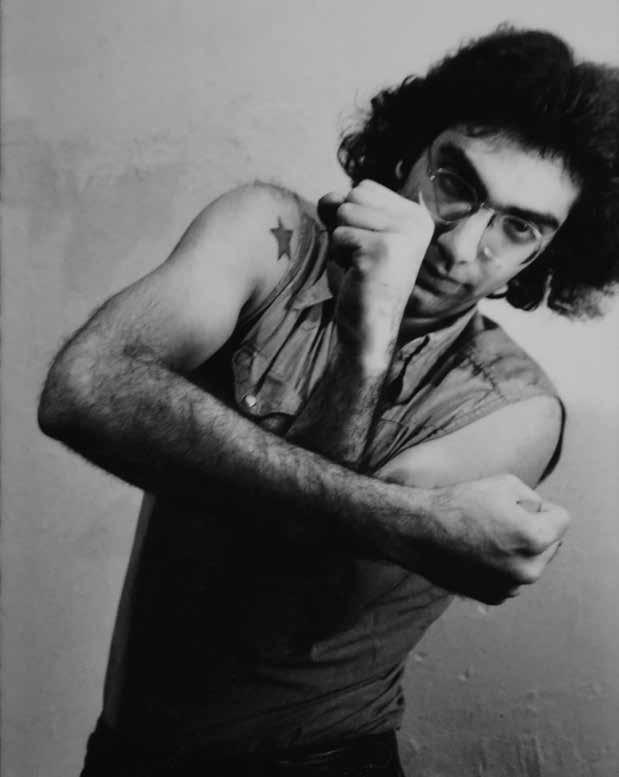

G.H. in 1975. Photo by Scott Billingsley

INTRODUCTION

This project began as a catalog raisonnée of G.H. Hovagimyan, documenting his work over the course of the last 50 years. It evolved into a story spanning five decades of changing media and culture, and seven major periods of activity—a compelling reflection on shifts in technology and consciousness in the last half-century. Hovagimyan’s spirit as a critical and fun-loving observer carries throughout: we find him continually embracing new forms of media and collaboration as a kind of freeform aesthetic research. It’s a position that allowed him to stay on the cusp of the latest media being developed for representation, information distribution, sharing, and computer-generated altered realities, adapting commercial programs for his own purposes in the manner of hacking or détournement, the Situationist method of turning hegemonic cultural products against themselves.

From the start, Hovagimyan had the good fortune to witness and participate in some of the watershed moments, places, and artistic projects of his time. In the early-to-mid 1970s, as a recent graduate of the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of the Arts), having studied with Cynthia Carlson, Rafael Ferrer, Don Roger Gill, and Rhee Morton, he landed at 112 Greene Street in SoHo as the neighborhood was being transformed by ad hoc artistic activity and the ascendency of the live/work loft and gallery scene. He sat the gallery at 112 Greene and became affiliated with post-minimalist artists who were repurposing discarded materials and buildings, altering the perception of spaces and their use. He visited Gordon Matta-Clark’s Splitting in Ridgefield, New Jersey, and assisted him in Day’s End in downtown Manhattan, Conical Intersect in Paris, and several pieces in Milan. He showed his own conceptual work at loft shows organized by Fluxus artist Jean Dupuy and at 112 Greene Street, The Kitchen, Idea Warehouse, and P.S. 1.

In the following years, Hovagimyan played drums in the punk band the Communists, which performed at CBGB and Max’s Kansas City, and in the famous No Wave show at Artists Space. He participated in the formation of Colab, a group of peers who exhibited works in their lofts—borrowed and squatted spaces to compensate for the lack of commercial galleries for young

Collaborations

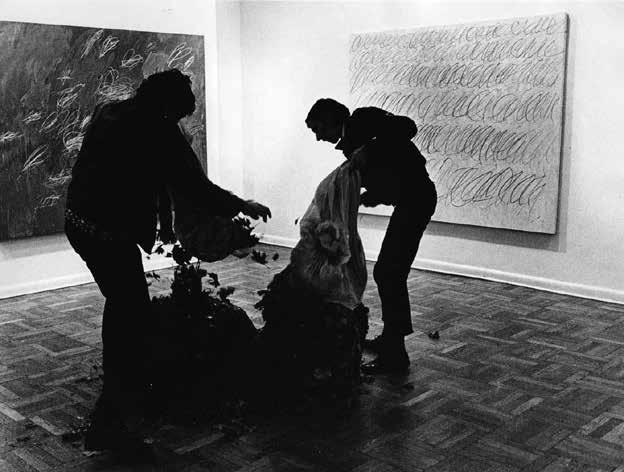

Rafael Ferrer, Three Leaf Pieces, 1968

While studying at the Philadelphia College of Art, G.H. Hovagimyan was introduced to some of the most prominent post-minimalist artists emerging in downtown New York. It was 1968, and Robert Morris’s Anti-Form essay appeared that year in the April issue of Artforum, helping define what become known as process art, an emerging tendency to move away from durable materials and consistency of form toward softer, pliable fabrics, strings, fibers, wires, and natural elements that decomposed and could be installed in a variety of ways depending on the setting.

Along with process art, performance—or what was then being called body art—was also gaining currency. It was a short train ride to New York City, and Hovagimyan took it to see a performance by his Philadelphia teacher Italo Skanga at 98 Greene Street, one of the first SoHo galleries. These were some of his earliest aesthetic influences as a young artist, plunging him straight into the avant-garde of the time.

When I was in art school, I was doing essentially a kind of process art, then I started doing performance. It was something like body works at that time, using your body as a material. It was something between Joseph Beuys and Vito Acconci.1

In 1968, Hovagimyan participated in a staged guerrilla art action by Rafael Ferrer, who would appear the following year in the Whitney Museum of American Art’s annual sculpture exhibition.

At that point Rafael Ferrer was a teacher at the University of the Arts, and there were several other people—Rhee Morton, Cynthia Carlson, Don Roger Gill—who were all pretty hot up-and-coming artists on the New York scene. Rafael was inviting artists in the New York scene like Robert Morris and Gordon Matta-Clark to come down as visiting artists and lecturers, along with several others.2

Rafael Ferrer, Three Leaf Pieces, 1968. Photos by Ron Miyashiro. © 2020 Rafael Ferrer/Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY

With two other students, Hovagimyan joined Ferrer in a truck from Philadelphia carrying large bags filled with leaves. They went to Leo Castelli’s galleries on 108th Street, 57th Street, and 77th Street and emptied the bags in the elevator, on the gallery floor, and in the stairwell. Castelli was at the time the most important gallerist in New York, representing Andy Warhol, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Frank Stella, and Cy Twombly, among other famous artists.

Rafael was invited by Robert Morris to be involved in the Castelli Warehouse show, which was a seminal show for Art Povera/process art that had people like Eva Hesse, Bill Bollinger, Richard Serra, Keith Sonnier, Alan Saret. He invited me and two other students to come with him, loaded up these big garbage bags with leaves in the truck, and we essentially filled the staircase in the Castelli Gallery with leaves. It was a seminal process art show, and that was literally after my first year in art school. I was introduced to the avantgarde art scene.3

The occasion for Three Leaf Pieces was Nine at Castelli, a show of nine post-minimalist artists organized by Robert Morris at Castelli’s 108th Street warehouse. Though they appeared to be ad hoc, the temporary Ferrer leaf installations were organized with the knowledge and blessings of Morris. It became a portal into the hippest quotient of the downtown scene.

We went to the gallerist Barbara Rose’s apartment for cocktails after the opening, and Keith Sonnier was there and Richard Serra and everybody, and I met them all. Then we went to Max’s Kansas City, which is kind of interesting, because Frosty Myers is here in Abrahamsville, Pennsylvania, and he was actually a fixture at Max’s. Mickey Ruskin was his patron, and Frosty designed and built every single one of Max’s bar and restaurants.4

Max’s was a famous hangout scene for artists, and Warhol dominated the back room during the period, with his Factory located around the corner on Union Square. It became a legendary venue for the glam bands that were formative for the emergence of punk. Later, Hovagimyan would play shows at

Top: Colab meeting on the second floor of 597 Broadway in Peter Fend’s loft, 1983. Photo: Albert DiMartino

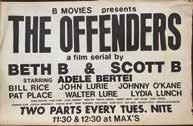

Above: Poster and banner ad, Scott and Beth B., The Offenders, 1979

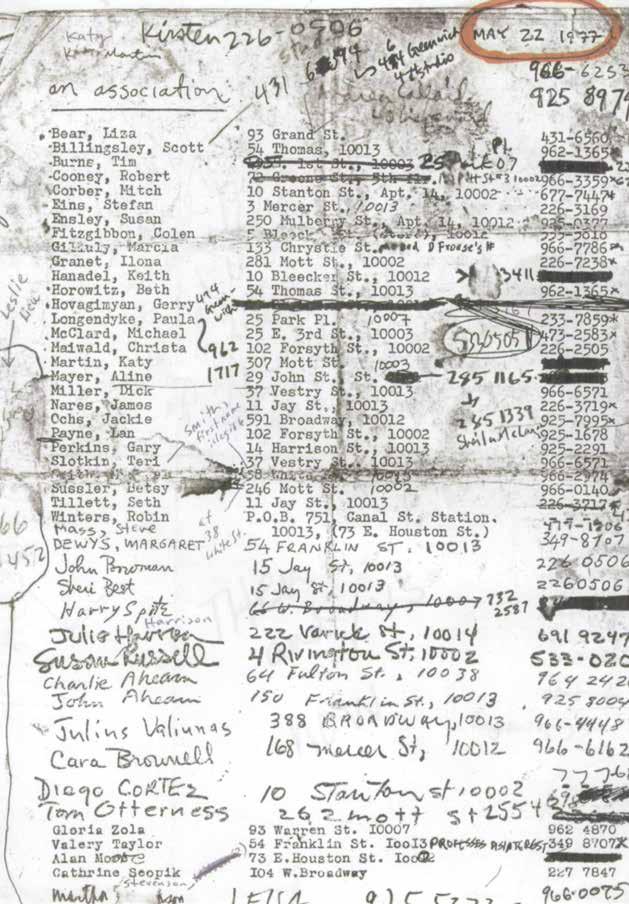

Opposite: Colab member list, May 22, 1977. Courtesy of Alan Moore

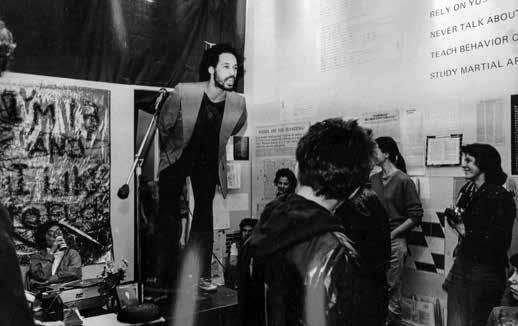

Top: Joe Lewis performing at the Manifesto Show

Photo: Coleen Fitzgibbon

Above: Tactics of Survival in the New Culture, G.H. Hovagimyan, 1979

Right: Postcard for reading at 112 Workshop

Excerpts from a Novel, 112 Workshop, Apr. 24, 1980

In 1979, the cast-iron loft building at 112 Greene Street converted to a cooperative apartment building, renting out the commercial storefront to offset the costs of improvements required to get a Certificate of Occupancy from the city.50 The gallery moved to 325 Spring Street in West SoHo, reopening in February as White Columns.

In April 1980, Hovagimyan read from a work-in-progress, a novel based on remembered dialog from the 1962 film Two for the Seesaw, set in a New York City apartment and starring Robert Mitchum as a lawyer from Nebraska and Shirley MacLaine as a struggling dancer. Hovagimyan had seen the film as a child and reconstructed the movie from memory without looking at the script, interspersing it with street scenes from his life as an artist and things going on with him at the time. Later he got the script and compared it to his memory.

I was trying to get to something. The movie must have made an impression on me. How a movie would influence what I was projecting about life when I was young, being an artist in New York, and the reality of being an artist in New York. Then Bright Lights Big City came out, and it was so similar that I gave up on it.51

Hovagimyan had a literary agent encouraging him to pursue the project, but as he recounted in a conversation, they were doing lots of cocaine together, and the agent’s wife eventually objected to him coming over. That was the end of his short literary career.

Above: Pseudo postcard, c. 1995–1997

Opposite: Art Dirt ad on Pseudo network

Videos and Hacked Interfaces

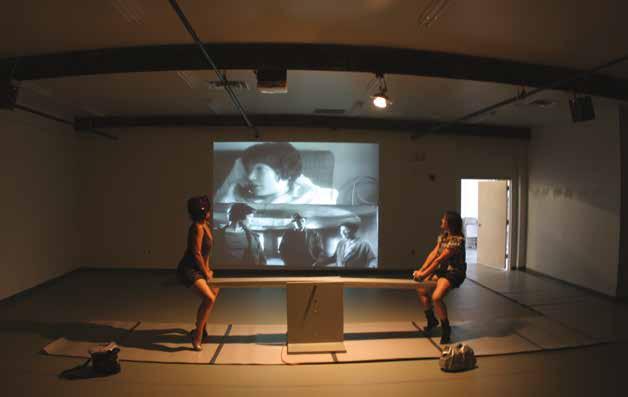

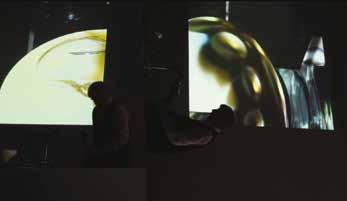

Top: See/Saw installation in use

Above: See/Saw rendering

Right: View of Radios installation

Hovagimyan associated the film with his earliest memories of New York City, and it became a text he continually referred back to, consciously and unconsciously in his work.

When I was in my 20s, I started writing a novel. It was a view of the downtown art scene and club scene interspersed with scenes from the 1962 movie Two for the Seesaw. I never finished the novel and lost the manuscript but revisited the movie 30 years later. That movie and Alphaville sat in the corner of my subconscious as a media dream or a theme. I sometimes think of it as peripheral consciousness, and I believe that’s where my art comes from. It is when I seize these notions floating around on the periphery and explore them that I engage my creative processes. I’ve been thinking a lot about generational narrative. My generation and that of my parents are intertwined in a narrative. The movie deals with my parents’ generations ideas of changing mores and bohemianism à la 1962. It also has a film noir vision of New York City that is very evocative. These create the idea of photography as memory…This is an alternative type of interactivity. When you are on the seesaw, you have a visceral dialog with the person opposite. You also have the kinesthetic sensations of the seesaw. Along with that, you notice you are controlling the projected windows. You try to assemble the jumbled narrative of the scenes you are viewing. This is immersion and deconstruction at the same time. The piece refers to any number of dance performances from the 1960s and 70s, as well as pieces done by Robert Morris. My sculptural references are from Arte Povera and 90s cyber-punk DIY installation.141

Music and sound played a role in Hovagimyan’s art going back to his spokenword rants and drumming for the Communists in the 1970s. The changing media of production and transmission remained a current throughout his early net art and online radio shows up to the multimedia pieces of the 2000s and AR installations in the 2010s. Radios adds the anachronistic component of mp3 chips embedded in old transistor radios playing period music, tapping into a strain of nostalgia also present in See/Saw.

Radios, 2010

Above: Still from video of Boxing Rants performance at Postmasters

Left: Being Event flyer

Opposite, right, top to bottom: Boxing Rants; Boxing Rants performance at Postmasters; Mapped Morphs at Postmasters; Mapped Morphs 3D objects

Boxing Rants

Space Painting 3

I realized that we’re going into space, so we’ve got this different type of consciousness, which is the virtual world’s consciousness, where there’s no up or down, there’s no gravity, there’s no anything…That means that everything—machines, architecture, all object forms, become subjects as well, because they’re now free from their functionality.173

Space Painting 4

In At Home in Space, the theme is objects that you would have in the home, but when you’re out in space, they’re all exploded and blown apart and floating. There’s no up or down or anything, because all of these objects are freed from the post-and-lintel constraints of architecture. So, again, it’s a liberation and a recombination, deconstruction, reconstruction, or decontextualization, loosening them from their intended purposes…it creates a whole other place.174

Space Rug

That goes back to the origination of net culture and computer culture, which flattens everything, because they’re all equal…in other words, the President of the United States is equal to a punk hacker on the web. All words have equal weight; there’s no such thing as media hegemony. By the same token, architecture loses its authority in a certain sense.175

Space Table

Space Table is composed of a printed canvas on a table with representations of things like spoons, a glass, and furniture in assemblage form, and a coiled object placed on the table.

Top: Space Painting 3 viewed through iPad at DVAA

Above: Space Painting 1 at DVAA