friends’ foreword

JEAN ALESI

“My friendship with Ayrton stems from my friendship with Gerhard. Long before we were teammates at Benetton, Gerhard and I had a lot in common through our shared interests and sense of humor! So it was because of him that I became one of Ayrton’s close friends following two personal events with Ayrton.

Phoenix in 1990, just after a semi-season in 1989, I was fighting with Ayrton during more than half a race, and I retook the lead just after he overtook me for the first time. In the end, he finally overtakes me, but the first podium of my life had a special meaning, especially thanks to the congratulations he publicly gave to me. I had the feeling of entering a new world… his.

And Barcelona in 1991, one grand prix, two duels between us. From lap 14 to 29, then in lap 42 to 50, when I climbed on a curb, risking taking both of us out, but… I got through! In both these situations, we really had some fun. And as we sometimes say, ‘It’s a bonding experience.’ Other circumstances and similarities have strengthened our relationship, which is undoubtedly one of the most rewarding I’ve ever had.”

GERHARD BERGER

“The first time I met ‘that guy’ (back then, in F3, everyone was, for the most part, just a new rival with no previous reputation), it was weird, strange! He won, but he wasn’t happy I got the best lap ‘instead of him,’ as he told me on the podium. I didn’t really care about it. I wanted to laugh about it and told him to file a claim. I would have even wanted him to win that thing, as I didn’t care about getting my name on a simple line. Nonetheless, the message was pretty clear: he hated losing and was ready to win at all costs.

Seven years later, we had become friends and teammates in F1 and, in a certain way, the biggest rivals as we had the same materials to work with. And to my surprise, when I was doing better than him, Ayrton was the first to congratulate me! And four years later, I lived something that can easily resume our friendship.

At the start of a race in Italy, as the announcer introduced the drivers on the grid one by one, the audience applauded loudly when my name was announced. Ayrton winked at me from his cockpit, pleased by the ovation. It was our last exchange of glances. It’s engraved forever in my eyes, in my head, in my heart, everywhere inside me, still vibrating on my skin. That was at Imola.”

THIERRY

BOUTSEN

“Sadly, I never had the opportunity to be teammate with Ayrton. And as he didn’t really have any bonds with other drivers, I have fond memories of our friendship. I don’t really remember how it happened. Maybe it was just like discovering a new guy, like a newcomer at the office. Feelings of sympathy and human sincerity quickly prevailed over all others.

On vacation at his place or elsewhere, we shared great moments of exchange and trust and were often in confidence on many subjects, including God, that he was thanking every time he won a race. Some media even claimed that he was doing that for his image. I guarantee you that it wasn’t for that. His sincere faith pushed him, and even if he was naturally a really good driver, it helped him by reinforcing his confidence, putting him on a level no one ever got since then. When my wife Patricia and I asked him to be the godfather of our son, it wasn’t because of our friendship. Knowing he had a really strong faith, we knew he would have been the ideal person for that. He accepted. Unfortunately, Cédric was born three weeks ‘after.’ Ayrton thus never became his godfather, but I am sure that anywhere he is, he is still keeping an eye on him.”

FROM FORMULA 3 TO FORMULA 1

Ayrton Senna’s numerous victories in England, first in Formula Ford, then in Formula 3 (10 victories in 1983), gave him the opportunity to showcase his talent.

Senna’s trial session with Williams, who didn’t want to sign a contract with Senna because they already had contracts with drivers Rosberg and Laffite, may have convinced Ron Dennis of McLaren to learn a tad more about him. However, Dennis had already decided to recruit Alain Prost to form a duo with Niki Lauda, who was aiming for a third world champion title. And while Peter Warr of Lotus would have loved pairing Senna with driver Elio de Angelis, the British sponsors of Nigel Mansell put some pressure in favor of the hotheaded Briton, who ultimately kept his place on Lotus’s racing team that was founded by the late Colin Chapman, who passed away in 1982.

PIQUET’S VETO

With Williams, McLaren, and Lotus unwilling to contract with Senna, only two teams remained open to him: Brabham and Toleman. Since July of 1984, Bernie Ecclestone was aware that Senna was free for the 1984 racing season. There were only two problems: Parmalat, the main sponsor of the team Ecclestone bought in the beginning of the 1970s, would have preferred having

an American driver with Nelson Piquet. The double world champion (1981, 1983) was aware of the potential and the danger coming from his young fellow countryman. He vetoed that decision. In the following years, he would deny it several times, but Herbie Blash, Brabham’s general director at the time, and Christ Witty, the boss of Toleman, were aware, and Ecclestone knew that this wouldn’t work: “Nelson was really irritated when he discovered we wanted to recruit Senna and talked to Parmalat. I told Parmalat that it was stupid to have two Brazilians, that they would never get along. I also explained to Parmalat that Senna was faster than Piquet, therefore he didn’t want him on the team.”

A DEPARTURE CLAUSE AT TOLEMAN’S

Senna thus signed with Toleman, but with a departure clause in his contract. He knew he was going to struggle with his F1 debut. If the car provided by Toleman was not good enough to meet the expectations of the driver, Senna had no problem going forward, so long as he could leave for another team at the end of 1984. The final negotiations happened in

England, with every line, every clause, and every sentence being translated, checked, and validated over the phone by Senna’s lawyers in Sao Paulo.

NO HELMET BIG ENOUGH AT ARAI

In the meantime, Senna, with the assistance of Keith Sutton, founder of the photography agency Sutton Images, was negotiating a sponsorship contract with Arai, a Japanese manufacturer of motorcycle and F1 helmets. The amount Senna asked from this potential new business partner far exceeded the original $60,000. Arai was shocked and simply sent this response to the daring Senna: “Sorry, but we don’t have any helmets that could fit your head.”

LATE PREPARATION WITH NUNO COBRA

Toward the end of 1983, as Senna was preparing for his F1 debut the following year, he thought he was having trouble with his heart. He booked an appointment with Nuno Cobra at the University of Sao Paulo. Their first meeting was not so great. Cobra had never worked with an F1 driver before and thought Senna was “a bit puny,” but ultimately accepted the challenge of “making that young guy stronger” by helping him mentally and physically prepare for F1 racing. The preparations started in the beginning of January 1984, just a few weeks before his grand debut at the Brazil Grand Prix at the Jacarepaguá track.

On March 25, 1984, at the age of 24, young Ayrton Senna officially debuted in F1 with the British Toleman team at the Jacarepaguá circuit in Brazil.

MONACO GRAND PRIX: NOT SO NICE

As he arrives in Monaco, after a new pole position and a withdrawal for running out of fuel, three laps from the end of the race at the San Marino Grand Prix in Imola, Senna is ready for the fight like never before. He goes in pole, again, for the third consecutive time, but his rivals are upset. Alboreto, the Ferrari driver, and Lauda, the running world champion, blame the Brazilian for getting in the way, braking and slowing them down on their fastest lap. “It’s easy to achieve pole in these conditions,” the McLaren driver says angrily, and in revenge, Alboreto also gets in the way of Senna in the Rascasse turn, nearly pushing him into the railings. “A pilot can be faster than the other, but he has to show sportsmanship,” adds the Italian. But as Prince Albert and Princess Stéphanie are invited into the Ferrari stands, he gives up shouting at the Brazilian after the qualifying. On the Sunday, the Brazilian starts off with cold tires due to a short-circuit on his heating blankets, but he still takes the lead until lap 13, when his Renault engine fails. In front of Alboreto and De Angelis, Prost wins in the other Lotus. Eighteen years later, during an interview, the team manager of Lotus at that time, Peter Warr, takes full responsibility for Senna’s behavior during this Monaco qualifying. He says that it was his idea and explains that the Brazilian regretted his attitude right after exiting his cockpit after the qualifying. “Peter, I never want to do that again. If someone is faster than me, then that’s alright,” the pilot said to him.

In 1985, Ayrton Senna claimed the third pole position of his career in Monaco. An engine problem prevented him from finishing the race, but in the following years, he would find solace by making the principality his own.

SENNA AND HIS DRIVING: A MASTER OF THE TURBO

Here’s a question many observers, like his teammates, rivals, engineers and mechanics, asked themselves: what made Ayrton Senna the pilot he was? First of all, it is important to understand how he drove. Many people compared his way of driving to someone dancing Samba because, yes, Senna was a part of an era where sliding was a part of driving, a very aggressive, virulent way of driving that allowed him to get the very small detail that would get him pole position. To understand this, it was important to listen to his car.

Generally speaking, in Formula 1, the attack on a corner is broken down into three acts. First, the driver brakes. Then, he turns the steering wheel to start the curve. Finally, on exit, he gradually re-accelerates. This method is simply called brake–steer–throttle. But the mid-1980s saw the advent of turbocharged engines, and “playing” with the turbo could be very beneficial. Senna was quick to understand this. When braking in a corner and gradually accelerating again, the Lotus driver noticed a slight slowdown in his engine, which is normal. During the time when Senna was not pressing the accelerator pedal, the turbo stopped working. As a result, he had less grip, less power and therefore less speed. In such moments, adapting one’s driving style becomes a necessity.

Senna, however, had an idea. During the corners, the Brazilian didn’t simply push the throttle. He turned and then tapped his accelerator pedal aggressively and repeatedly, right in the middle of a corner. In this way, the turbo continued to be supplied and was always running at maximum rpm, which also gave his car more grip. For the ears and the stopwatch, it was a treat. But for his fuel consumption, it could be troublesome. His car used far more fuel than his rivals who were driving in a more classical way. This explains, partially, why the Brazilian so often ran out of fuel.

Third on the grid at the 1986 British Grand Prix, Senna was betrayed by his gearbox on the 27th lap. The race was won by Nigel Mansell (in the foreground).

DUCAROUGE’S LETTER

Before the Japan Grand Prix, Senna’s penultimate race with Lotus, his main engineer, Gérard Ducarouge, wrote him a lengthy farewell letter. What Ducarouge had not expected was that Senna was going to read it before coming to the track for the first free practice session. Upon his arrival in the pits, Ducarouge sees Senna and realizes that he has already read the letter. Senna is nearly crying and Gérard is also overwhelmed. He immediately regrets having given his driver an emotional shock, particularly when he is about to get in the car and drive at 300 km/h on one of the most grueling circuits on the calendar.

In his letter, Ducarouge, one of the most famous F1 engineers of that era, explains that he has decided not to formally say farewell to his favorite pilot since he does not feel like looking him directly in the eyes. He also says sorry for not giving him a car that was on a par with his talent during these three years and says that this frustration would follow him all his life.

During the 1987 season, Ayrton Senna (Lotus) and Nigel Mansell (Williams) often fought at the front.

CARDS FOLDED AT MCLARENHONDA

Things changed for Senna's third season with McLaren–Honda.

First, Alain Prost left for Ferrari after swapping seats with Gerhard Berger. Berger became the Brazilian's second driver at Woking and caused him far fewer problems.

Second, Ferrari worked well over the winter, following the departure of engineer John Barnard. The new 641 was ready to win it all. Roles were cleverly assigned within the Scuderia: Nigel Mansell was the showman, and Alain Prost wanted above all to win the world title against his great rival in the clean, efficient style (except at Suzuka at the end of 1989) that had already won him three world titles. This duel kept F1 fans on the edge of their seats as the two former teammates got the

season off to a flying start. They won ten of the first 12 races. The McLaren MP4/5B was not as dominant as the two cars that preceded it, but Ayrton won three of the first five Grands Prix on the calendar (Phoenix, Monaco, Montreal). Prost then enjoyed a fine run of three victories (Mexico, France, Silverstone) only to be thwarted by the Brazilian in Germany. After a break in Hungary (2nd), Senna won again (Belgium, Italy) and arrived in Japan doubly armed: a nine-point lead over the Frenchman

(78 to 69), who had just given himself another chance by winning in Spain, and, above all, a desire for revenge still burning one year after Suzuka 1989. The suspense didn't last long: Prost started out in front, and, on the very first lap, Senna charged at him to harpoon the Ferrari. Both cars were in the gravel trap, and the Brazilian was crowned world champion with the 11 best results of the season because Prost would have two points deducted in Australia if he won. No one at Ferrari lodged a complaint, and the race stewards validated the result and, thus, Senna's second world title. His French

rival preferred to remain silent. A silence that honors him, as everyone witnessed this premeditated settling of accounts live one year after Suzuka 1989.

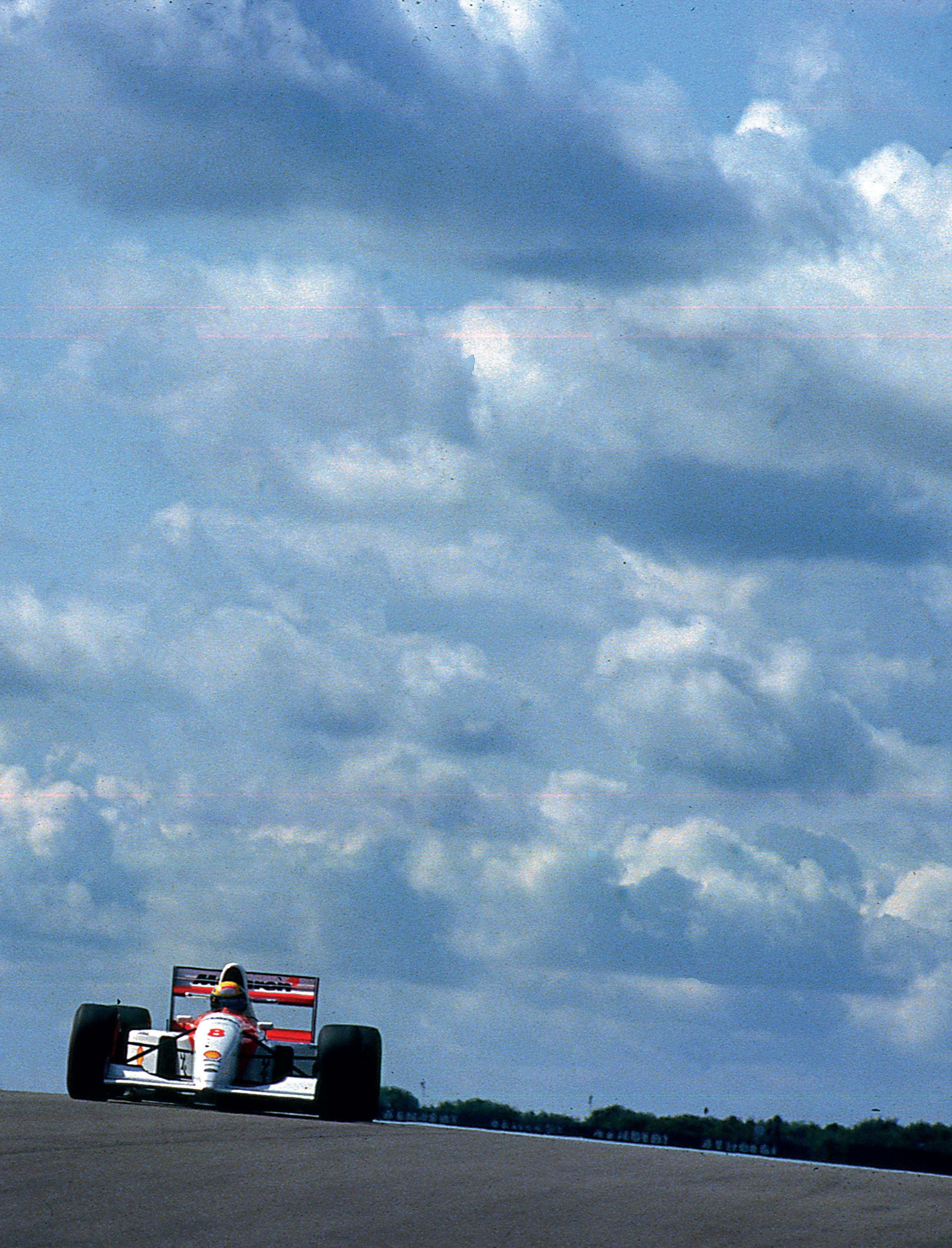

Top: Senna’s McLaren is seen from the rear—a common image the Brazilian’s subdued rivals see throughout the season.

Previus double page: The 1990 Canadian Grand Prix takes place in heavy rain. Not a problem for Senna, who delivers a stellar performance with both the pole position and the victory.

Ayrton Senna’s 1991 season is a benchmark for the Brazilian driver. Between his first win in Brazil and his third World Championship title, he further cements his name in Formula 1 history.

GIOVANNA AMATI AND SENNA, THE GENTLEMAN

Giovanna Amati, the last woman to drive an F1 car during the practice sessions for three Grands Prix—in 1992, in a Judd-powered Brabham— remembers the only driver to greet her on her arrival in the paddock: Ayrton Senna.

“I’d already met him in Monaco in 1985 when he was Elio De Angelis’ teammate at Lotus, and I’d even asked Elio to introduce me to him. After the Monaco GP, a friend who knew I wanted to meet him said to me, ‘If you want, I’ll take him to the heliport in Monaco on Monday morning. Would you like to come?’ I replied, ‘Yes, yes, yes, I’d be happy to keep you company.’ And then, when we got to the heliport [laughs], I said ‘Goodbye Ayrton, bon voyage’ and kept looking at him— because for me, he was an idol, a myth—and took two steps back, not realizing that a suitcase was lying right behind me. I just had time to see the expression on Ayrton’s face, and then I fell backwards. I swore I’d never have an idol in my life again if I lost control like that [smile].”

“[When I joined Brabham in 1992,] the only one who came to say hello was Ayrton. The Brabham team was ‘in the Bronx,’ at the other end of the pit lane, while McLaren was in front, very close to the exit. So, he drove up the whole pit lane and back to Brabham. All the mechanics and engineers were stunned! One mechanic came up to me and asked, ‘What did you do to him?’ I replied that I hadn’t done anything. He insisted, ‘Did you squeeze him on a curve?’ But I hadn’t done anything: I’m very attentive to others, I’m a professional. In the box, they were stunned and didn’t know what to expect. In fact, he simply came over and shook my hand, saying, ‘Welcome, I’m glad you’ve arrived in Formula 1, and I’d like to congratulate you.’ I didn’t know what to say. For him to come and greet me was unique. He was special and he felt the best. That’s why he could welcome someone like me, who was nothing, who was just a beginner.”

In fact, he simply came over and shook my hand, saying, ‘Welcome, I’m glad you’ve arrived in Formula 1, and I’d like to congratulate you.’

giovanna amati

At every Grand Prix weekend, Senna, a fierce competitor at heart, considers all factors that can make him better.

WILLIAMS: THE WINNING TICKET

At the beginning of 1993, Alain Prost emerged from his sabbatical and took the seat he’d been aiming at for several months in Frank Williams’ team: that of Nigel Mansell, who had set out to conquer America in IndyCar, in the CART championship. It suited his muscular, no-nonsense driving style perfectly, and he won it hands down on his first attempt.

Prost’s move to Williams—the best team at the time—was obviously a good one; otherwise, the Frenchman wouldn’t have done everything in his power to get behind the wheel. The 1993 season confirmed that it was the ideal package, with the added bonus of a certain Damon Hill as the second driver, son of Graham and Prost’s perfect lieutenant in a team above the rest, as in 1992. The statistics are crystal-clear: seven wins for Prost in the first ten rounds, then three more for Hill at the end of the season.

Overall: 10 wins for Williams-Renault in 16 rounds, compared with five for Senna (including Brazil and Monaco) and just one for Schumacher. Prost, freewheeling, finished with three 2nd places in a row, including two behind Senna in Japan and Australia. The score was indisputable: 99 points to 73 for the Brazilian, who narrowly avoided a Williams drivers’ double in the World Championship, with a 4-point lead over Hill. Last but not least: Prost now leads Senna 4–3 in the number of world titles, but he’s about to retire for good. The road is open for the Brazilian, who will succeed him at Didcot.

Senna hates driving in the rain but proves formidable when the weather is atrocious.

A

special

hello to my friend ... to our friend Alain. We miss you, Alain.

SAN MARINO GRAND PRIX, IMOLA: THE TRAGEDY

San Marino is the first European round of 1994. Senna is determined to shine and catch up with Schumacher, who leads 20 points to zero. Squeezed into a cockpit he finds too cramped, the Brazilian secures provisional pole on Friday, but his young friend, Barrichello—a Jordan rookie, takes off and crashes into the tire wall at 220 kilometers an hour. He breaks his nose and suffers more from fear than harm. The next day, as Austrian Roland Ratzenberger attempts to qualify, the wing of his Simtek-Ford comes loose a few meters before entering the Gilles Villeneuve curve. At 315 kilometers an hour, he hits the wall, and it’s all over. Death strikes F1 for the first time since May 14, 1986, when Elio De Angelis died on the Paul Ricard Circuit. Senna sees Ratzenberger’s crash from the screen in the Williams pit and goes to the scene. His friend, Dr. Sid Watkins, suggests that he end his race weekend. “Sid, I can’t give up. I’ve got to drive tomorrow,” replies the Brazilian. It’s his 65th pole position, and he’s determined to honor it. The next morning, he is TF1’s luxury consultant for the circuit tour. Before starting, he lets slip a token of his friendship for Alain Prost, who is about to comment on the race: “A special hello to my friend ... to our friend Alain. We miss you, Alain.”

On the grid, before taking the start, Senna looks worried and disturbed. This is unusual for such a meticulous, focused man. The start is marred by a collision between JJ Lehto and Pedro Lamy. The debris and a wheel fly into the crowd, hitting spectators, and the safety car comes out of the pits. When it re-emerges again at the end of lap 5, Senna is ahead of Schumacher. At the end of lap 7, seven seconds after crossing the timing line, he plunges into the Tamburello curve. Senna’s Williams FW16 slams straight into the tire wall. The accident plunges Brazil into grief. And leaves 160 million Brazilians without their hero.

Ayrton senna

Beaten by the Benetton-Ford team, Senna has doubts about the legality of certain elements of Michael Schumacher’s car.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Writing about Ayrton Senna is both a chance and a privilege. This book you are holding could never have come to fruition without the invaluable support of people who are now very dear to us. At Glénat, first and foremost. In pole position, a big thank you to David Kings and Sophie Lecompte. Their advice, guidance, and support during the book’s writing meant a lot to us. A special thanks also to Sophie Legras for the finalization of this work.

I have immense gratitude to the individuals approached for this book who agreed to discuss the man Ayrton Senna was and delved into their memories. At Lotus in Norfolk, Bob Dance and Chris Dinnage. In Italy, thanks to Leo Turrini and Mike Wilson. On the North Carolina side, sincere thanks to Jacques Dallaire and Steve Hallam in California. Also, in São Paulo, eternal thanks to Nuno Cobra. Thanks also to Sidineia Schwarzwalder and Pamela Jansen for the multiple connections.

To Helena Santos Hortz, who has been immensely generous. Her assistance in navigating texts in the language of Vasco de Gama and her help in various interviews in Brazil are priceless. Muito obrigado a você.

To Dominique Leroy, thank you for your trust and collaboration in this adventure. To Richard Micoud from the Automobile Club de Monaco. To Grégory and Loïc, and Formula 1 and fast sports enthusiasts. To our parents, families, friends, and colleagues of Thomas at Silverstone in Monaco, whose support and enthusiasm are unwavering. To Victoria and Sylvain.

Daniel Ortelli et Thomas Woloch

A big thank you to all those who made the realization of this book possible, starting with the drivers with whom I have been able to forge a deep friendship: Jean Alesi, Gerhard Berger, and Thierry Boutsen. Their testimonials published in the preface touch me particularly.

Thanks also to the playmates who accompanied me to conduct interviews with many Formula 1 actors: Jean Claude Azria and Bruno Bonizec.

I want to express my gratitude to the following individuals for their valuable contributions: Patrick Behar, Denis Chevrier, Jean-Jacques Delaruwière, Steve Domenjoz, René Fagnan (especially for the shots in Detroit in 1986), Richard Micoud, Raymond Papanti, Didier Paris, Pierre Van Vliet, Anaïs Monells, Anne Rol, Marion Yvora, Jean-Michel Tibi, Guillaume Zazurca, and Stéphane Zuber. A special thanks to Anne-Laure Chambert-Protat and her daughter Coline.

To my partner, Theresa Revoil, who supported me throughout the stressful moments. Finally, thanks to the Glénat team and my coauthors, Daniel and Thomas, who have taken up the torch so dignifiedly to write a text worthy of this grand champion. Bravo to them!

Special thanks to René Fagnan for the photos on pages 15 (B), 17, and 36; to Renault Sport for the photo on pages 34-35; and to Honda for the photos on pages 72, 73, 105, 109, and 164.

A big thank you to Grand Prix Photo, which has long showcased Dominique Leroy’s work. Except for the photos mentioned above and the photos on pages 4, 5 (M), 14 (T), 27 (T), 48, 63, and 216, all the photos in this book are now available on www.grandprixphoto.com and www.dominiqueleroy.art.

Dominique Leroy