After the midday prayer, three congregants have repaired to the shaded arcade of the mosque founded by Amr ibn al-Aas, the Arab general who conquered Egypt in 640, bringing Islamic rule to Africa. The venerable fortress of Babylon, then under Byzantine command, had swiftly fallen to his besieging forces. According to tradition, he chose the site for his mosque and new capital when he discovered a white dove nesting in his tent in the army’s encampment.

Hundreds of millions of years ago, powerful tectonic forces began separating Africa from the Earth’s other land masses. The resulting uplift, faulting, and subsidence are vividly reflected in the fractured mountains and high plateaus of much of the Horn of Africa. Seismic activity, both past and ongoing, is also evident in the region’s numerous volcanoes, crater lakes, and lava outcrops, as well as in the mineralrich hot springs of the salt flats along

the Red Sea coast. These plains lie at the northern end of the Great Rift Valley, a transcontinental depression observable most dramatically from Ethiopia to Tanzania. The Rift’s Afar section, near Harar, has yielded major finds of fossil hominins, the best known being the skeleton nicknamed “Lucy” (Australopithecus afarensis), among the first of our ancestors to walk upright, some three million years ago.

Ancient Egyptian literature and art show that expeditions to Punt usually went via the Red Sea. In one tale, a shipwrecked sailor is rescued and brought to an island by a magical serpent who calls himself the Prince of Punt. Painted reliefs from the 18th Dynasty depict a royal fleet’s departure, the Puntite king and

queen welcoming the envoys, and the ships taking on cargo for the return voyage. Among the goods were young myrrh trees intended for planting in Egypt. During later periods, ports on the Red Sea became key hubs for commercial routes linking Ethiopia with the Arabian peninsula, the Mediterranean, and India.

Signs of today’s Red Sea trade may be seen in the cowrie shells adorning these bowls displayed on a wall in a Harar house. And in the town’s covered market, sacks bulge with pungent Arabian spices.

Emblems of Ethiopia

On the left, a priest carries a gold-plated cross bearing swastika motifs referring to the supposedly miraculous construction of the rockhewn churches of Lalibela. According to legend, the faithful labored by day, using L-shaped tools, while angels took up the implements and worked through the night. The swastika’s joined Ls neatly evoke this wondrous partnership. The other priest holds a small cross made of plaited fibers, its four equal arms signifying the canonical Gospels interwoven in harmony.

Soon after Christianity was adopted, an Aksumite Bible was produced in Ge’ez, the kingdom’s ancient South Semitic language, making it one of the oldest known biblical translations from Greek. Ethiopian liturgical texts continue to be written in Ge’ez, which early on developed its own alphabetic script. Here, we see a priest supervising the religious education of two young boys. Bibles and other sacred texts are frequently re-bound in sumptuous fabrics, similar to the ones fashioned into priestly raiment for festivals and holy-day processions.

The streetscapes and markets of Ethiopia overwhelm the senses. Here, eight views offer a glimpse of their visual complexity. The first image shows the Kafira market in the Muslim quarter of Dire Dawa. The remaining photographs were taken in Harar, except for that of the schoolgirls in Addis Ababa. The hues are frequently brilliant, sometimes subtle. The details dazzle and intrigue, from the intricate designs woven into baskets and shawls to the exquisite motifs printed on fabrics, from the frieze of vultures in wait above a butcher shop to a tribeswoman’s forehead tattoo. At every turn, the eye is caught by the confident ways in which girls and women layer a stunning panoply of colors, textures, and patterns in their dress.

Persian paradises also blossomed in garden carpets, the earliest known the bejeweled wonder made for the 6th-century CE Sassanian ruler Khosrow, as well as in the opulent blue and turquoise tiles adorning mosques and other buildings from the 15th and 16th centuries on. A new manufacturing technique, involving painting directly on the tiles, as opposed to the older method of assembling the design as a mosaic, soon led to an efflorescence of polychrome floral patterns, as seen here in the Royal Mosque of Isfahan. More simply, petals seem to float in the tiled octagram of this historic hammam (bathhouse) in Yazd, mirroring ceiling insets of colored glass.

As legend has it, Alexander the Great, having conquered the entire Achaemenid realm and beyond, obtained in Persia a magic mirror in which he could view his vast empire. Entering Persepolis in triumph in 330 BCE, he surely saw himself in the highly polished stonework of Darius’s Hall of Mirrors. Indeed, over the centuries mirrors imbued with metaphorical and real properties, as well as the mirroring we have already

observed in gardens and waters, have consistently been significant aspects of Iranian cultural identity and expression. The photographs that follow explore the subject further by pairing mirrors with portraits. We begin in the Kerman bazaar with these displays in adjacent stores, one selling mirrored furnishings, each piece distinctive, and the other headscarves, each mannequin’s face individuated.

During the Qajar period of the 18th and 19th centuries, mirrors played major roles in architectural embellishment. Here, for instance, the Golestan Palace in Tehran confounds with the multiplying illusions of its mirrored walls and ceilings. For their own residences, wealthy merchants of the time introduced mirrors into embrasures of white stucco, as though they were windows. In turn, these reflect actual windows and their colored glass, often arranged in tile-like patterns and sometimes studded with miniature mirrors.

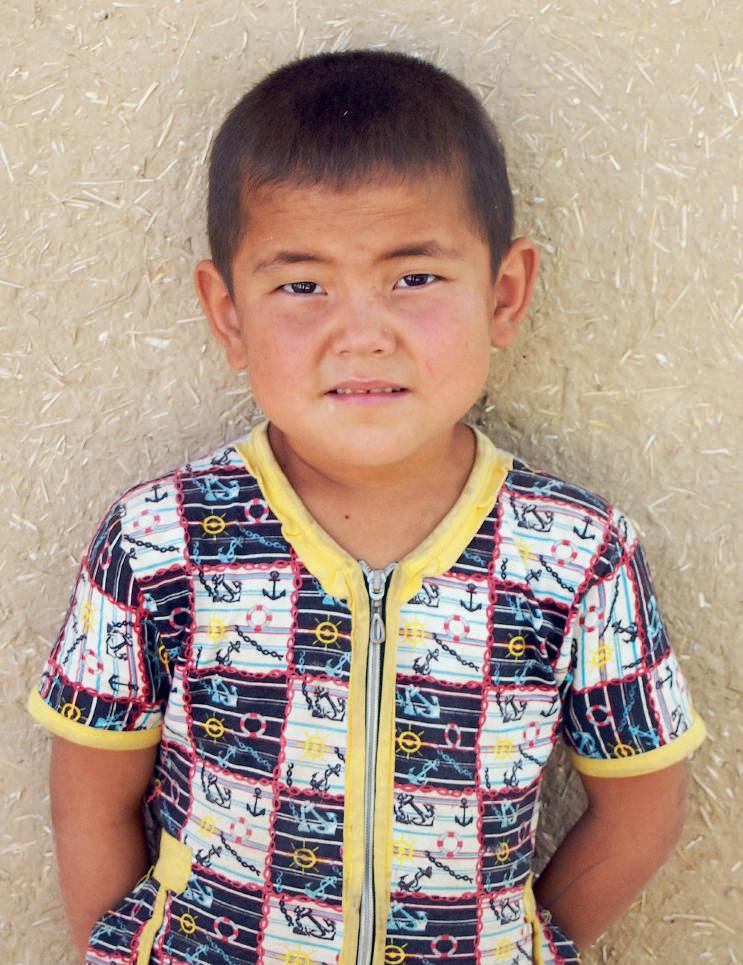

With his classic Mongol features, this boy recalls the warriors who swept across Central Asia in the 13th century under Genghis Khan and his successors. At its height, the Mongol Empire’s extent was larger than any other in history. While the nautical motifs on the boy’s shirt may seem ironic, given his doubly landlocked country of Uzbekistan, the Mongols’ control of coastal areas opened important maritime trade routes from the Sea of Japan to the Red Sea.

The Mongols’ military prowess owed much to their cavalry, mounted on the exceptionally hardy Mongolian horse. Likely from that stock were derived the ancestors of the famed Akhal Teke horse of Turkmenistan. At a breeding farm near Ashgabat, we admire one of these “golden horses,” so named for the sheen of the coat and mane.

This edition © Kulturalis Ltd, 2026

Texts © Karen Polinger Foster, 2026

Photographs © Karen Polinger Foster, 2026

The author has asserted her rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as author of this work.

First edition

First published in 2026 by Kulturalis Ltd

14 Old Queen Street London SW1H 9HP

United Kingdom www.kulturalis.com

ISBN 978-1-83636-041-4

Editor: Ben Goulder

Design & Art Direction: Ben Goulder

Map by Daniel Mugaburu

Reprographics by Opero, Verona

Printed and bound in Turkey

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of the authors and publisher.

Every effort has been made to acknowledge correct copyright of images where applicable. Any errors or omissions are unintentional and should be notified to the publisher, who will arrange for corrections to appear in any future editions.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Cover image: Dome interior, Coptic Museum, Cairo, early 20th century, combining reclaimed materials from the churches of Old Cairo with Middle Eastern architectural elements and Orientalist motifs.