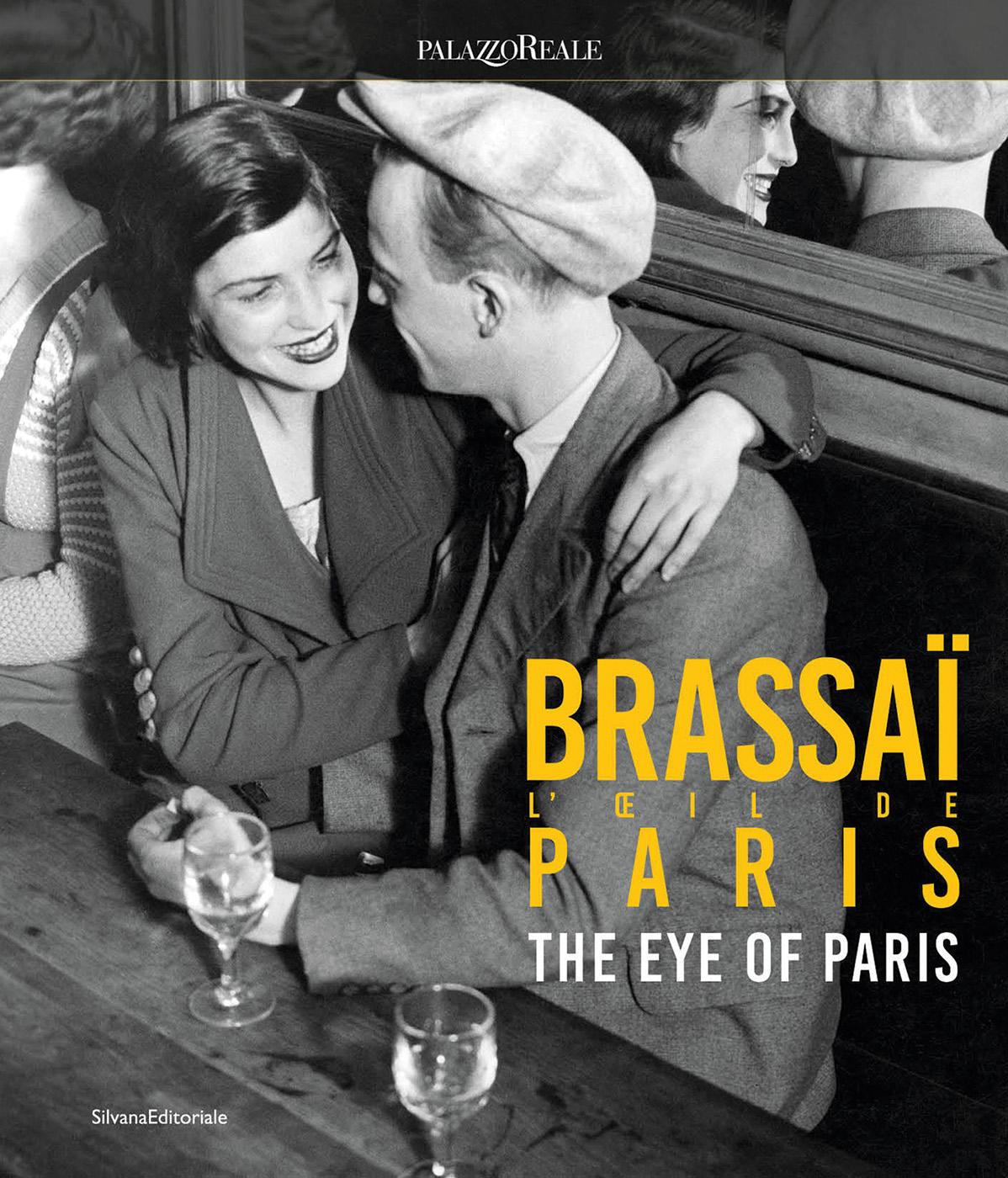

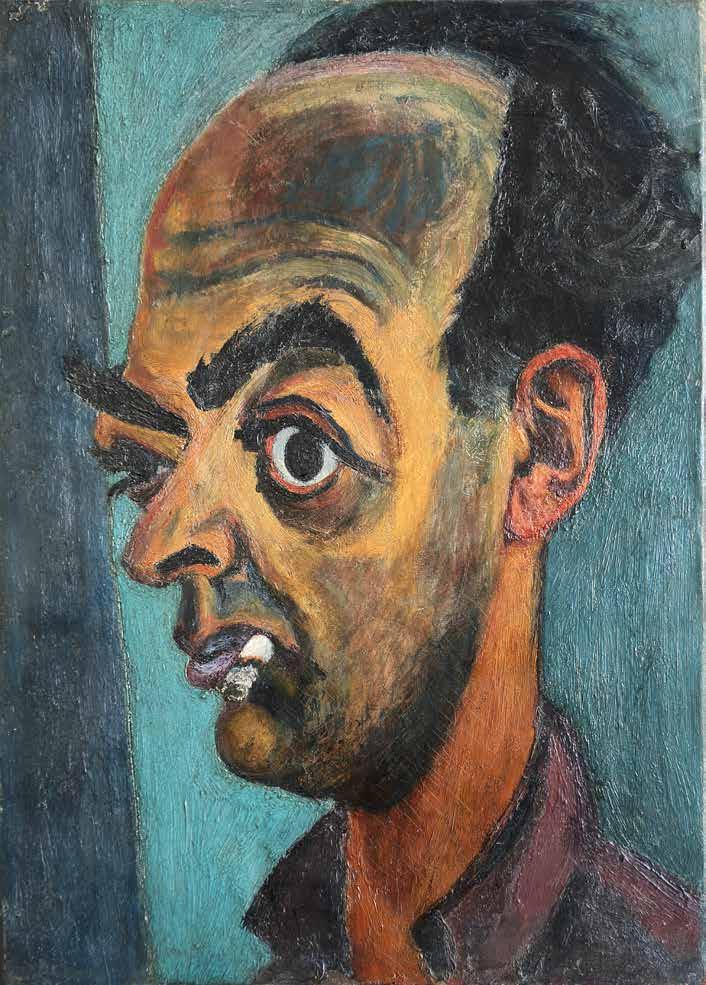

Brassaï, l’œil de Paris

Brassaï, the Eye of Paris

Philippe Ribeyrolles

Brassaï

Brassaï

Silvia Paoli

Gilberte Brassaï: témoignage

Gilberte Brassaï: Testimony

Annick Lionel-Marie

Les débuts / Beginnings

Paris de jour / Paris by Day

Paris de nuit / Paris by Night

Paris secret / Secret Paris

Paris « Illusions » / A Paris of “Illusions”

Graffiti

Le nu : du réalisme à l’onirisme /

Nude: From Realism to the World of Dreams

Mode et soirées, le chic parisien /

Fashion and Soirées: Parisian Elegance

Regards d’artistes - Regard de l’artiste / Artful Gazes – The Artist’s Gaze

Tendre enfance / Tender Childhood

Paradoxes

Biographie / Biography

Gilberte Brassaï

Liste des oeuvres / List of Works

Bibliographie / Bibliography

Annick Lionel-Marie : Brassaï, Gyula Halász de son vrai nom, a tiré son pseudonyme du nom de la ville où il est né, en Transylvanie : Brassó. Pourtant il n’est jamais retourné en Hongrie. Comment l’expliquez-vous ?

Gilberte Brassaï : Effectivement, si ses parents lui ont rendu visite en France à plusieurs reprises, Brassaï lui-même n’est jamais retourné en Transylvanie. Revendiqué par les Hongrois comme par les Roumains, il était souvent sollicité, invité officiellement, mais refusait toujours ces invitations. Il y avait pour une bonne part dans ce refus le souci de garder intacts ses souvenirs d’enfance et de jeunesse, l’appréhension d’être déçu. En outre, il détestait cérémonies et banquets, eût voulu garder l’incognito. Il craignait aussi le régime en place, l’impossibilité, qui sait ? de regagner la France.

Brassaï, malgré son aversion pour tout ce qui était administratif, s’est fait naturaliser français après la guerre, en 1949, et se considérait français à part entière. Mais, à un ami zurichois, le collectionneur Georges Bloch, connu par l’intermédiaire de Picasso et qui avait une propriété à Saint-Moritz, il écrivait en 1976 : « J’ai renoncé avec tristesse à aller vous voir à ces hauteurs. Je suis né dans les Carpates, la montagne et l’altitude restent pour moi l’élément vital (et beaucoup plus que la mer), et je garde toujours la nostalgie des sapins, des mélèzes, des rhododendrons, des edelweiss, des gentianes. C’est mon seul “Heimweh”. »

A L-M : Vous avez connu Brassaï en 1945. Quel était à l’époque le groupe d’amis qui l’entourait ? G B : Brassaï aimait avoir des jeunes autour de lui, et mes amis, tel Roger Grenier, étaient les bienvenus. Brassaï avait le don d’improviser dans un cercle, c’était un conteur. Jamais avare de son temps, il était tout aussi prêt à discuter une après-midi entière avec un jeune photographe ou écrivain. On se retrouvait souvent au Dôme, à la Coupole, à la Closerie des Lilas, ou à Saint-Germain-des-Prés…

Annick Lionel-Marie: Brassaï, born Gyula Halász, took his pseudonym from his native town in Transylvania: Brassó. Yet he never returned to Hungary. Why do think this was?

Gilberte Brassaï: It’s true that while his parents visited him in France on a number of occasions, Brassaï himself never returned to Transylvania. Claimed by both the Hungarians and the Romanians, he was often asked, even officially invited, but he always refused these invitations. Much of this refusal was linked to a desire to keep the memories of his childhood and youth intact, a concern about being disappointed. He also hated ceremonies and banquets, he would have wanted to remain incognito. Lastly, he feared the regime then in power, the possibility that he would be prevented from returning to France. Despite his aversion for all things administrative, Brassaï became a naturalised French citizen after the war, in 1949, he considered himself a full-fledged Frenchman. But to a friend from Zurich, the collector Georges Bloch whom he’d met through Picasso and who had a property in Saint Moritz, he wrote in 1976: “Sadly I have given up the idea of coming to visit you in those lofty climes. I was born in the Carpathians, the mountains and alpine heights remain an essential part of me (far more than the sea), and I still cling to a nostalgia for the fir trees, the larches, the rhododendrons, the gentian. It is my only ‘Heimweh’”.

A L-M: You met Brassaï in 1945. Who were his group of friends at the time?

G B: Brassaï loved having young people around him, and my friends, like Roger Grenier, were always welcome. Brassaï had a gift for improvising when he was with a group of people, he was a storyteller. Always generous with his time, he would spend an entire afternoon talking with a young photographer or writer. We’d often meet at the Le Dôme, La Coupole, La Closerie des Lilas, or in Saint-Germain-des-Prés…

There was Vincent Korda, a very good painter before he was lured away by his brother Alexandre’s film productions, Lawrence Durrell, likable and funny, Hans Reichel, William Hayter, Calder,

4 (3

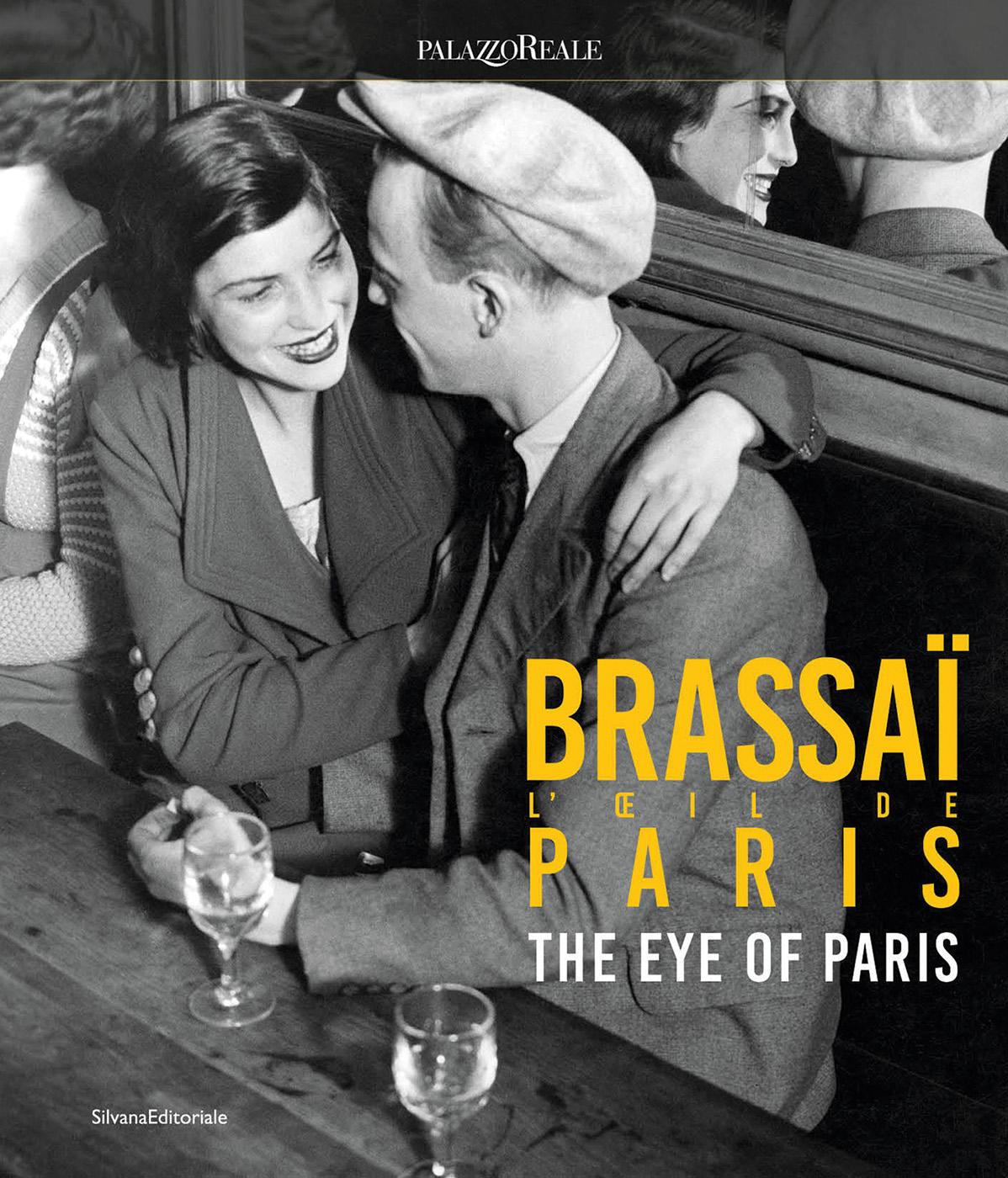

Autoportrait Self-portrait 17 juillet 1952 17 July 1952

5 (4

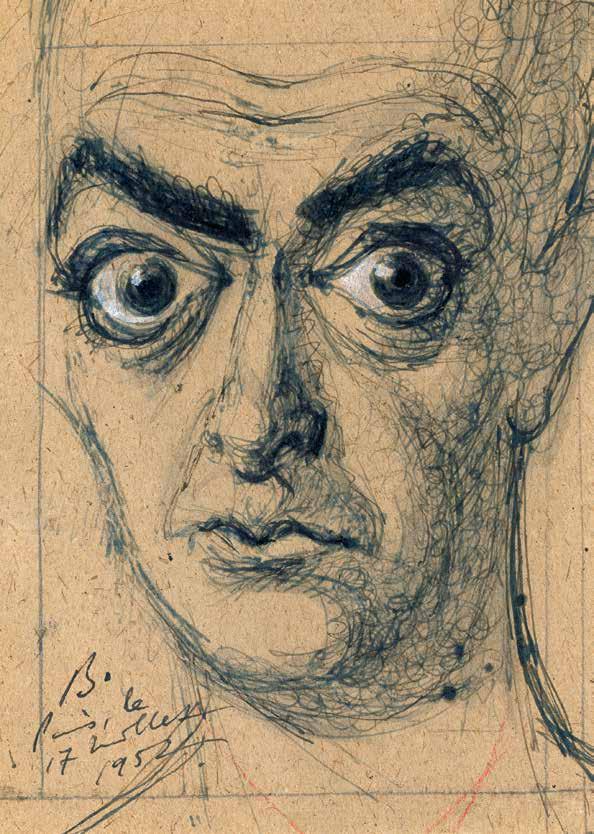

Autoportrait Self-portrait vers 1920 1920 circa

29 (55

La pluie, rue

30 (56 Sous la pluie In the rain vers 1930-1933 1930-1933 circa

41 (29

Le photographe ambulant au parc Montsouris

Itinerant photographer at Parc Montsouris vers 1931-1932 1931-1932 circa

42 (30

La toilette “Washroom” 1931

43 (33

virgolette qui da eliminare oppure da conservare ?

Bougnats livreurs de charbon Coalmen années 1930 1930s

44 (31

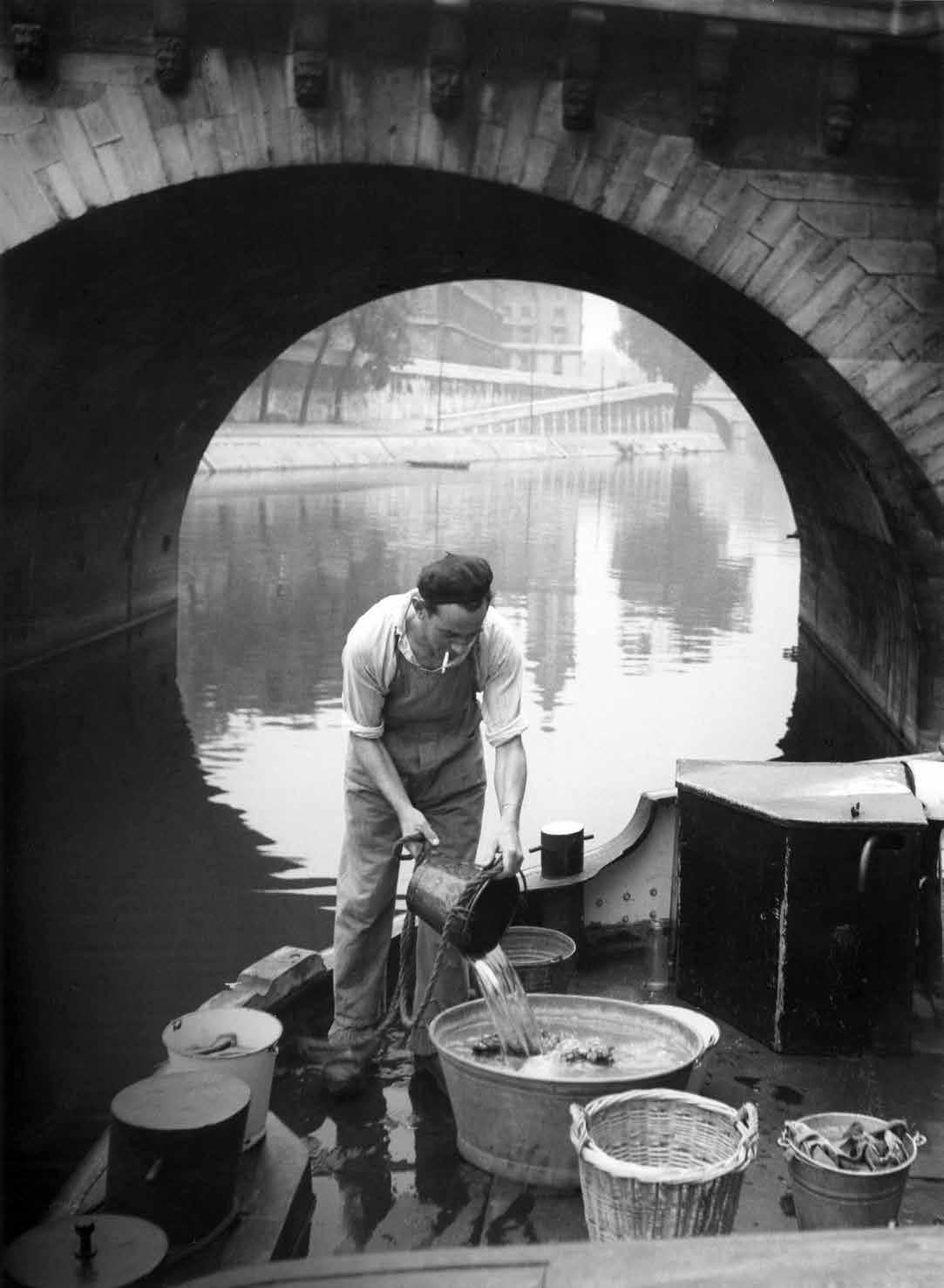

Péniche sous le Pont-Neuf

Barge under Pont-Neuf 1932

75 (131

1932

76 (132

Blanche in Montparnasse vers 1932 1932 circa

« Vous savez ce que Picasso dit lorsqu’il vit mes dessins en 1939 ? “Vous êtes un dessinateur né, Brassaï. Pourquoi ne continuez-vous pas ? Vous avez une mine d’or et vous perdez votre temps à exploiter une mine de sel !” »

“Do you know what Picasso said when he saw my drawings in 1939? ‘Brassaï, you’re a born illustrator. Why don’t you continue? You’ve got a gold mine, yet you waste your time mining salt!’”

146 (211 Suite d’études de femmes nues Studies of female nudes 1er juin 1944 1 June 1944

147 (210 Corps de femme Woman’s Body vers 1931-1932 1931-1932 circa

148 (212 Femme nue de face

Female nude Berlin, vers 1921 Berlin, 1921 circa

Brassaï croyait en la magie de la franchise et de l’immédiateté de la photographie. Il considérait que ce qui est naturel, c’est de ne pas esquiver la présence du photographe, ce dernier devant établir un lien avec ses modèles. Leurs regards, souvent empreints de complicité, en étaient la traduction sinon la meilleure récompense. Pour les objets inanimés, il souhaitait « révéler leur âme ». En les photographiant sous une lumière particulière, par une densité qui est totalement étrangère à leur existence réelle, il a su leur donner une fascinante présence. Passé maître dans l’art de sublimer des perspectives par des contrastes saisissants, il obtiendra des images d’une incroyable richesse visuelle.

Brassaï believed in the magic of a photograph’s sincerity and immediacy. He thought it was entirely natural to elude the presence of the photographer, while the latter sought to establish a bond with his subjects. Their expressions, often full of complicity, were the visual translation of that bond and his greatest reward. As for inanimate objects, he wanted “to reveal their soul”. By photographing them in a particular light, with a photographic density far removed from their reality, he succeeded in turning them into beguiling presences. A master at exalting perspectives through surprising contrasts, Brassaï was thus able to create images of incredible visual richness.

173 (280 Fernand Léger dans son atelier , rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs Fernand Léger in his studio on Rue Notre-Dame-des-Champs 1952

Au fil de leur complicité, les deux artistes se découvrent des goûts semblables, voire des fascinations communes tant pour l’atmosphère dénudée des Folies Bergère que pour celle mystérieuse du cirque, notamment Médrano où Picasso aimait amener Brassaï. Poursuites lumineuses, images plongeantes insolites pour l’un et corps entremêlés pour l’autre, chacun à sa façon marquera de son empreinte ces divertissements populaires qui les avaient liés.

Over the course of their friendship, the two artists discovered they had similar interests, such as a fascination with the uninhibited atmosphere of the Folies Bergère or the mystery surrounding the circus, particularly the Cirque Medrano, where Picasso loved taking Brassaï. For one it was the interplay of lights and the dizzying, unusual images, for the other, the bodies entwined; but each of them, in their own way, left a mark on these popular spectacles that had helped cement their friendship.

196 (296

Gilberte Brassaï

Portrait de Brassaï et Picasso à Notre-Dame-de-Vie à Mougins

Portrait of Brassaï and Picasso at the Notre-Dame-de-Vie estate in Mougins

8 juillet 1966

8 July 1966

197 (292 Scène « Juan-les-Pins », arrière-scène des Folies Bergère Behind the scenes at Les Folies Bergère during the “Juan-les-Pins” show vers 1932 1932 circa

198 (290 « La cage aux fauves », scène aux Folies Bergère “The Animal Cage”, show at Les Folies Bergère vers 1932 1932 circa

Prix de la Société des gens de lettres pour son livre Les artistes de ma vie.

1984

Brassaï vient de terminer la rédaction d’un ouvrage sur Proust, auquel il a consacré plusieurs années de sa vie, lorsqu’il meurt le 7 juillet à Beaulieu-sur-mer, dans la lumière de la Méditerranée. Il repose au cimetière du Montparnasse, au cœur de ce Paris qu’un demi-siècle durant il a tant célébré.

Awarded the Prix de la Société des Gens de Lettres for his book Les artistes de ma vie.

Brassaï has just finished a work on Proust, to which he has dedicated several years of his life, when he dies on 7 July in the Mediterranean light of Beaulieu-sur-Mer. He rests in Montparnasse Cemetery, at the heart of the city of Paris that he had done so much to celebrate for half a century.

Brassaï par Alexander Liberman, États-Unis, 1973 Brassaï in a photo by Alexander Liberman, USA, 1973

Silvana Editoriale

Directeur général / Chief Executive

Michele Pizzi

Directeur éditorial / Editorial Director

Sergio Di Stefano

Directeur artistique / Art Director

Giacomo Merli

Coordination d’édition / Editorial Coordinator

Maria Chiara Tulli

Rédaction / Copy Editing

Valérie Labourdette

Traduction / Translation

Contextus. We Translate Art (Brett Auerbach-Lynn, Riccardo Cristiani, Daniela Innocenti, Cheli Rioboo)

Mise en page / Layout

Serena Parini

Organisation / Production Coordinator

Antonio Micelli

Secrétaire de rédaction / Editorial Assistant

Giulia Mercanti

Iconographie / Photo Editor

Silvia Sala

Bureau de presse / Press Office

Alessandra Olivari, press@silvanaeditoriale.it

Droits de reproduction et de traduction réservés pour tous les pays

All reproduction and translation rights reserved for all countries

© 2024 Silvana Editoriale S.p.A., Cinisello Balsamo, Milano © eventuale

ISBN: 978-88-366-5741-4

Aux termes de la loi sur le droit d’auteur et du code civil, la reproduction, totale ou partielle, de cet ouvrage sous quelque forme que ce soit, originale ou dérivée, et avec quelque procédé d’impression que ce soit (électronique, numérique, mécanique au moyen de photocopies, de microfilms, de films ou autres), est interdite, sauf autorisation écrite de l’éditeur. Under copyright and civil law this book cannot be reproduced, wholly or in part, in any form, original or derived, or by any means: print, electronic, digital, mechanical, including photocopy, microfilm, film or any other medium, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Crédits photographiques / Photo Credits

Silvana Editoriale S.p.A. via dei Lavoratori, 78 20092 Cinisello Balsamo, Milano tel. 02 453 951 01 www.silvanaeditoriale.it

Les reproductions, l’impression et la reliure ont été réalisées en Italie

Achevé d’imprimer par xxxx Finito di stampare nel mese di febbraio 2024

Reproductions, printing and binding in Italy

Printed by xxxx in February 2024