BERLIN DEKO

Central European Furniture from 1910 to 1930

Markus Winter & Don Freeman

The Rediscovery of German Art Deco: Decorative Arts during the Weimar Republic (1918–1933)

What is German Art Deco? The Emergence of a New Period Style.

A Modern Temple of Art: Leo

The Ornament of Our Times

4 Film still, The Golem: How He Came into the World set design: Hans Poelzig, 1920

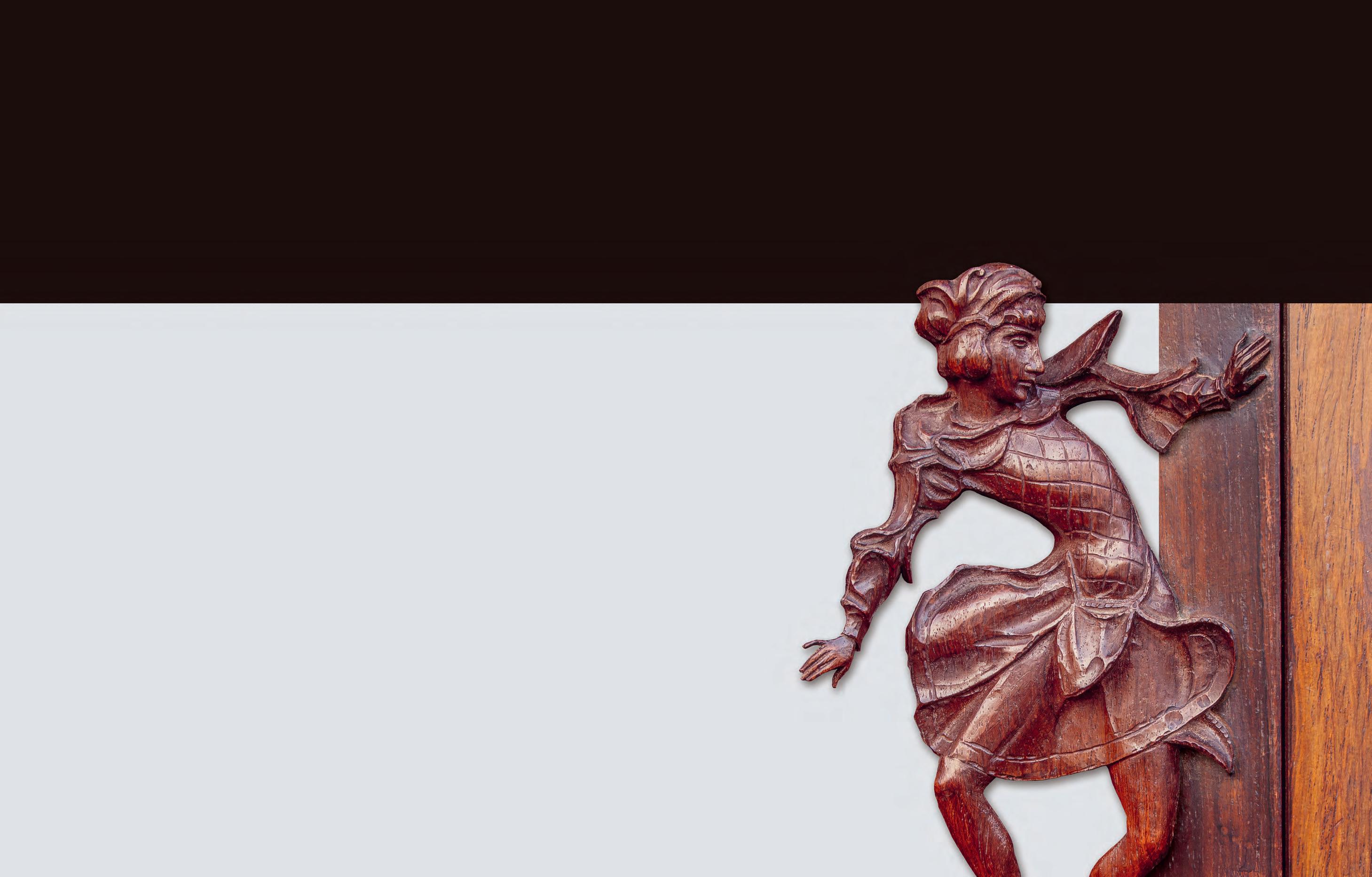

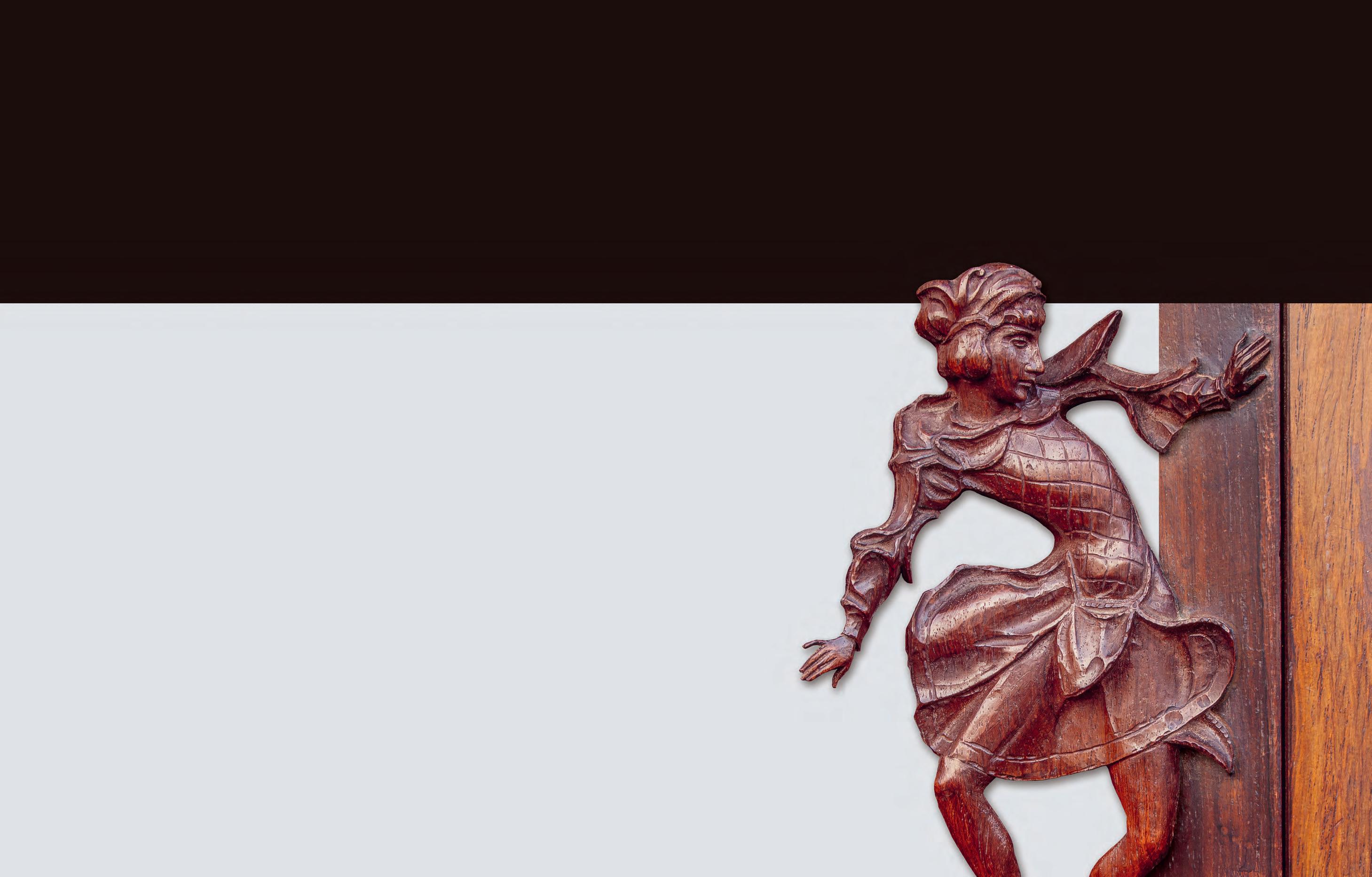

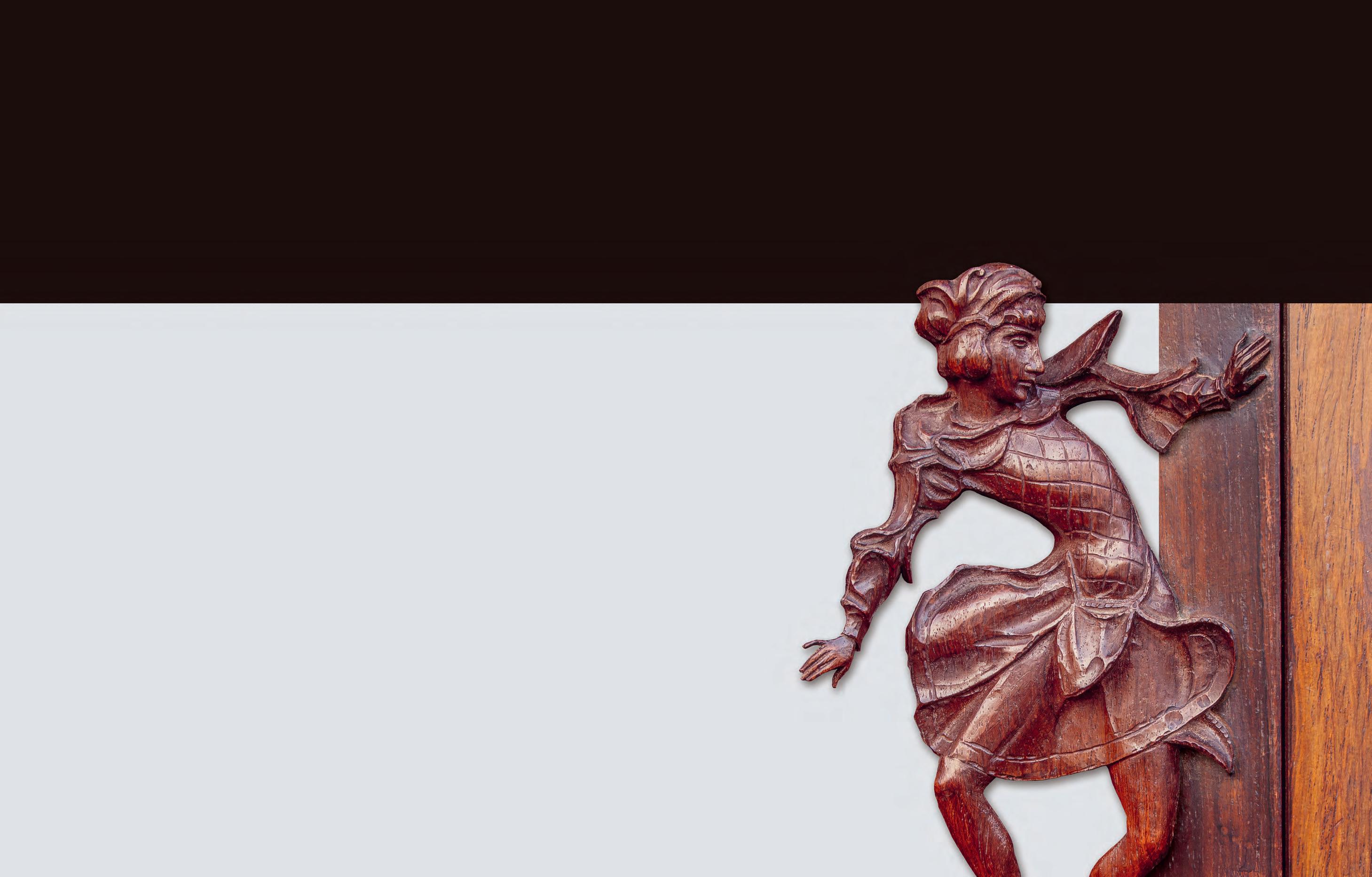

26 Oskar Kaufmann (February 2, 1873–September 8, 1956), dining chair for Villa Leo Lewin in Breslau, carved rosewood, 1917, private collection

The chair combines several sources: Frederick the Great Rococo forms, especially the design of the feet, inspired by the furniture designs of Johann Michael Hoppenhaupt the Elder, 18th century; then again, the shape of the back echoes English Baroque designs. The carvings themselves are of exotic (non-European) flowers: Egyptian, agave or birds of paradise, for example. A fruit skin could be suggested by the fillet that runs down the left and right sides of the chair’s front legs. These exotic flowers are similar to those used by Cesar Klein in his stained glass and mosaic works. On the other hand, there are references to the spirituality of Munich Art Nouveau, such as Bernhard Pankok. It is possible that this chair is the first example of an Expressionist Rococo style. Designers will later look to Kaufman’s exoticizing style for direction.

28

27 Oskar Kaufmann, dining chair for Villa Leo Lewin in Breslau, carved rosewood, 1917, Der Architekt Oskar Kaufmann, 1928

Johann Michael Hoppenhaupt the elder, (1709–after 1755), drawing for a chest of drawers, Berlin, circa 1740

97 Franz Xaver Unterseher (January 25, 1888–April 12, 1954), tabernacle mirror, carved and painted wood, circa 1925, Museum Schloß Wernigerode

Leo Nachtlicht (August 12, 1872–September 22, 1942), vanity table, wood lacquered in RAL 1019 gray beige, circa 1922, private collection, might have been part of a commission together with the side table fig. 24

The concept of the tabernacle mirror alludes to the idea that one must open doors to see one’s true self. The mirror’s alternative use as a picture of Mary may also point to the spiritual aspects of this ritual.

100 view of fig. 97

98 Franz Xaver Unterseher, tabernacle frame, Deutsche Illustrierte Rundschau, 1927

99 Leo Nachtlicht, boudoir in the house of Dr. Schwalbe, Innendekoration, 1922

The central relief depicts a mature woman holding a bowl, reclining in a landscape of Mediterranean architecture and nature, while a separate goblet rests on a plate nearby. Design elements also found in the works of Oskar Kaufmann and Bruno Schneidereit are the pedestals to the left and right of the foot section.

Once owned by the actress Ute Willing in Berlin in the 1980s, this island-like stage can serve for different Hellenistic or Nordic mythological interpretations. The interplay of fertility, sensuality, and transience, captured in a veristic nude, makes this work a significant contribution to the interior design of New Objectivity and Magic Realism. But ultimately, with its children, sleep, and gentle death, the bed is the place where night transpires.

122 Unknown, bed, carved and lacquered wood, Berlin, circa 1922, private collection

148 Fritz August Breuhaus (February 9, 1883–December 2, 1960), library cabinet, carved and veneered walnut, veneered amboyna, partly ebonized, manufactured by Valentin Witt, Munich and Cologne, circa 1914, private collection

The cantilevered table top rests on a square display case with Chinese latticework and large rounded corners in the Roman style.8 Troost also used this corner solution and combined it with sculptural neoclassical carvings as can be seen on furniture by Johann Conrad Bromeis (1788–1855) at Museum Fasanerie in Fulda. It is this very table, by an as of yet unidentified creator, that shows what the impact of Berlin Deko on the shard of time under discussion reads like.

8 Lucien Zinutti, Il Linguaggio del Mobile Antico, Treviso, 2011, p. 340.

163 Paul Ludwig Troost (August 17, 1878–January 21, 1934), buffet in a dining room, Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration, 1911

161 | 162 Unknown, salon table, carved and lacquered wood, Berlin, circa 1913, private collection

176 Jean Krämer (March 11, 1886–January 17, 1943), console table with desk unit, possibly for the reception room at the Otto Bing house, Berlin -Wannsee, walnut veneered, Berlin, 1921, private collection

177 | 178 Jean Krämer, reception room for Otto Bing, Berlin -Wannsee, Innendekoration, 1922

200 | 201 |

202 Oskar Kaufmann (February 2, 1873–September 8, 1956), bathroom for Leo Lewin, Giallo di Siena marble, sculptural works by Franz Metzner (1870–1919), mosaics by Cesar Klein (1876–1954), manufactured by Puhl & Wagner Gottfried Heinersdorf

TheA MODERN TEMPLE OF ART

Leo Lewin’s Villa in Breslau 1

Magdalena Palica

“The house I would like to return to”

Georg Kolbe, 16.03.19212

years of the Great War (1914–1918) took an enormous toll on European culture. Its all-encompassing nature even consumed philosophers, who were recruited to lend their talents to national propaganda programs—an effort dubbed “The War of Philosophers” by Peter Hoeres3 —which painters were then expected to translate into political posters and writers into leaflets. Most of the artists who did not want to support such nationalist endeavors ended up serving in the trenches. By 1917, the war had already destroyed many talented people and more would die within the following year. Even in the midst of such loss to the artistic community, the war at times offered an opportunity for a spectacular Gesamtkunstwerk to emerge. One shining example is the villa that a 36-year-old Jewish entrepreneur named Leo Lewin decided to purchase in Breslau in 1917 and redecorate with the ambitious goal of turning it into a modern temple of art.

A year earlier, the artistic milieu of Breslau had been nearly wiped out with the loss of two personalities vital to its cultural identity: the death of renowned

physician Albert Neisser, whose villa housed a delightful collection of art, and the relocation to Dresden of local architect Hans Poelzig, director of Breslau’s Academy of Art and Design. After Neisser’s death, his villa was converted into a museum and the city lost one of its most important meeting places for artists and their admirers. Poelzig’s predilection for modern artistic movements had exerted significant influence on the rather conservative tastes of the local society, and with his move to Dresden avant-garde art lost an essential supporter in the capital of Lower Silesia.

The income that allowed Leo Lewin to even imagine his project came from the textile company, C. Lewin, which had been founded by his father, Carl Lewin, and was one of a handful of army contractors to benefit from mass orders for military uniforms thanks to the war. By 1916, Leo was co-managing the business, together with his father and two brothers, Salo and Max. The prosperity of such contractors stood in sharp contrast to the vast majority of businesses in Breslau that had been forced to cut

1 T he article is based on my research about Jewish art collectors in Breslau, see: Magdalena Palica, Od Delacroix do van Gogha. Żydowskie kolekcje sztuki w dawnym Wrocławiu (From Delacroix to van Gogh. Jewish Collections of Art in Breslau), Wrocław, 2010, and Magdalena Palica, Von Delacroix bis van Gogh. Jüdische Kunstsammlungen in Breslau, in: Jüdische Leben in Schlesien z wischen Ost und West, edited by Anno Herzig, Göttingen, 2014, pp. 390–406.

2 Note on the page from Leo Lewin guest book. Georg-Kolbe -Museum, Berlin Nachlass Georg Kolbe, Signatur GK.608; 21; 1; 1.

3 P. Hoeres, Der Krieg der Philosophen. Die deutsche und britische Philosophie im Ersten Weltkrieg, Paderborn, 2004.

228 Fritz A. Breuhaus, detail of the chest in fig. 232

FURNITURE IN THE EXPRESSIONIST ROCOCO STYLE

Markus Winter

Atthe beginning of the 20th century, the number of styles available to the designer of a home was seemingly unlimited. They ranged all the way from Assyrian to Cubist. This eclecticism was very much in the spirit of Ulrich, the protagonist from the novel The Man Without Qualities by Robert Musil,1 who seeks to find order in extremes. As a reader, my three favorite examples of this strategy are the following: first, the relationship between the mucous membrane of the lips and that of the intestine; the second, the trajectory from conception to suicide; and the third, the chasm between racial mixing and segregation.

But Musil poses a fourth and final opposition through Ulrich’s experience: the radical difference between life in the country and life in the city. He can no longer return to country life because he has lost what Musil calls “the primitive epic to which private life still clings, although in public, life can no longer be narrated.” The thread of heroic narrative has snapped, leaving existence “to spread out, in an infinitely interwoven surface.”2

In citing Musil’s oppositions, I wish to establish that the furniture discussed here, which falls outside the

1 Robert Musil, Der Mann ohne Eigenschaften, Hamburg, 1952, p. 20.

2 I bid., p. 665.

3 Paul Zucker, Styles in Painting, New York, 1963, p. 6.

construction of the “modern,” was in fact the very pulse of the 1910s and 1920s. Musil’s musings on the “primitive” bookend this article. The furniture at hand not only is evidence of a particular style, but also moves towards a specific cultural horizon. The primitive has been invented by a society that fears being primitive. The scope of this article, however, is limited to examining a type of furniture that embodies a fearlessly cosmopolitan persuasion, not a social critique.

For the architect and art historian Paul Zucker (1888–1971), no one style can be better or worse than any other, for the very nature of styles is comparative rather than progressive.3 Wilhelm Pinder (1871–1947) goes further, asserting that there had never been an orderly historical enfilade of styles.4 Progress, when speaking of design, is merely an academic fantasy that has trickled down to the collective. Instead of a distinct transition from one style to the next, and to the next style after that, style engulfs us in a tidal wave. The Central European architects working from 1910 to 1930 lived out a highly energized dialectic between what may simplistically be called the linear and the painterly, or the static and dynamic.5

4 Wilhelm Pinder, Die deutsche Plastik vom ausgehenden Mittelalter bis zum Ende der Renaissance, Berlin, 1914, p. 119.

5 Heinrich Wölflin, Kunstgeschichtliche Grundbegriffe, Munich, 1915.

Berlin Deko is the first comprehensive English survey of early twentieth-century German and Central European furniture design to move beyond the notion of a linear development of styles between Jugendstil and Bauhaus. It explores the period between 1910 and 1930, revealing a diverse continuum of styles, including the overlooked “Expressionist Rococo” that flourished in Berlin. The book highlights Berlin’s role as a center for furniture and interior design that attracted international artists.

With contributions by the following authors: Ulrich Leben, Michael Mertens, Magdalena Palica, Arne Sildatke, Markus Winter, Paul Zucker.

ISBN 978 -3 - 89790 -741 - 6