Interior as Landscape

In 1985, Hadid worked on several interior concepts in London, such as broadcasting studio Harlech Television (HTV), and private residences Melbury Court and Halkin Place. Through the addition of penthouses, opening-up of floor plans, and introduction of mechanized partition walls and oblique canopies to these 19th- and early 20thcentury structures, her team sought to create landscapes furnished with sofas in irregular shapes, glass and steel tables, rotating beds, and boomeranglike recliners. The furniture shares qualities with mid-century pieces by the Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer and the Danish designer Verner Panton, and would not look out of place in the Jetson family’s living room. In its eclecticism and historicism, including its references to the Soviet avant-garde, the furniture relates to Postmodern design strategies proliferating at the time. Although these interior commissions were never realized, they can be seen as speculative research projects. The archive at the Zaha Hadid Foundation includes drawings that map London interiors, connecting disparate projects to each other and the city at large. The paintings and technical drawings for Halkin Place, for example, present interiors and furniture as forms of

urban intervention. Arguably, this kind of critical engagement allowed Hadid to formulate links between architecture and design. Tellingly, a few years later, technical drawings for an unrealized art and media center at Zollhof 3 in Düsseldorf, Germany (1989–93), an unrealized major urban project, featured furniture originally created for 24 Cathcart Road in London’s Kensington district.

The 24 Cathcart Road commission came from timber heir William Bitar, and the brief was simple: white furniture and no timber surfaces.5

Conceptually, the furniture engaged with ideas of flexibility (the pieces were multifunctional) and dynamism (either by design or construction), and turned the client’s generic 1960s apartment into a site of architectural innovation. Hadid said, “the furniture developed out of the idea of creating an environment.”6 For this project, sketches and model making, instead of Hadid’s Suprematist-styled paintings, were the chief methods for achieving the dynamic shapes. Michael Wolfson, one of the key architects in the early office, designed and developed many of the pieces. A briefing could be a drawing on a Post-it or notepad. For example, the bronze base of the Sperm table derived from a quick squiggle by Hadid.

Zaha Hadid Architects, Halkin Place, Rotations of interior design sketches, 1985

Zaha Hadid’s sketches of Halkin Place use a repertoire of warped walls, oblique canopies, and rotating or boomerang-shaped furniture. These design concepts reoccurred across interiors, furniture, and architectural projects in the 1980s.

Portrait of Zaha Hadid in Studio 9, 10 Bowling Green Lane, London, 1985

This portrait shows Zaha Hadid with her furniture designs, the Whoosh sofa and Sperm table. During this time, fashion and lifestyle magazines became increasingly drawn to her star qualities, making her the ideal architect to feature.

Dean Maltz

The Ethos of Shigeru Ban

Shigeru Ban Architects, Triangular Scale Pen, 2004

Manufactured by ACME Studio, a pen point emerges with a twist from an architectural scale ruler.

Whatever the medium or scale of his projects, Shigeru Ban applies the same design ethos. Mottainai (もっ たいない or 勿体無い)—a Japanese phrase conveying a sense of regret over waste—is at its heart, leading to a method that avoids waste and seeks a low carbon footprint. These principles are brought to bear throughout his practice, from schemes as vast as the 500,000-square-foot (45,000-squaremetre) Swatch and Omega Campus

in Biel, Switzerland (2019), to items as small as the six-inch-long (15-centimeter) Triangular Scale Pen (2004) that doubles as an architect’s ruler. They even apply to the humblest of objects, such as his Square Core Toilet Paper, whose angular core tube both prevents overuse due to accidental unrolling and configures aggregated toilet-paper “rolls” into cuboids, allowing for more efficient packing for shipping.

Having first met Shigeru Ban when they were both students at New York’s Cooper Union in the early 1980s, and later becoming his business partner, Dean Maltz has had a lengthy creative relationship with the practice. Here he discusses Shigeru Ban Architects’ innovative use of materials, and the relationship of the practice’s unconventional furniture to its built projects—a trajectory of exploration that has produced some unique designs for furniture and buildings alike.

Ban’s interest and dexterity in furniture making—often overshadowed by his architecture— first appeared following his time as a student in New York City, where he graduated from the Cooper Union in 1984. One year after his graduation, he designed the Keiko light fixture, which blurred the boundary between building and object. While his later furniture designs emanate from material explorations, Keiko conveys

a preoccupation with architecture and tectonics. Comprising a straight fluorescent tube bulb and a truss frame, its translucent and removable shade is made of Japanese washi paper. It can be installed as a standing fixture or cantilevered from a wall, demonstrating Ban’s commitment to multifunctional design. The blurring of boundaries between architecture and furniture that we see in this early design has

extended throughout his long career. Ultimately, he is an environmentally compassionate designer who adaptively navigates many mediums to support exploration of the potential, limits, and responsibility of architecture in all its forms and sizes—whether products or buildings.

Joyful Curves in the Face of Standardization

CRAB’s curves have expanded since that early fun with a jigsaw. The nobbles and notches have been scaled down to become the practice’s logo, and scaled up to form their building, landscape, and city plans. Rather than a style or type with rules and order, they work more like a language that is learned through immersion, constantly working with hand sketches and models.

A pure expression of this is the Flip-Flop Wall that CRAB designed in 2021 as a piece of street furniture scaled up to the length of a 300-meter (985-foot) street for the public realm of Kai Tak Sports Park in Hong Kong. A curve wobbles in and out, working as a transition between two different levels, and between the scale of stadium crowds that hurry past in their thousands and that of daily life. The flip-flop of the wall-like bench carves out seating, quiet corners, and communal squares along its run. Its undulating elevation creates points of privacy and peeking through, a continuation of the unraveling of the interruptions to the table’s edge, but now interrupting the straight lines and standardized panel façades of its site.

CRAB’s work is often born out of a reaction to standardized design. The original table reacted to another white box room, and the Flip-Flop Wall to the lack of character in the contemporary public realm of commercial Hong Kong developments.

In 1929, the early modernist Eileen Grey and critic Jean Badovici summed up their feelings toward such standardization in a dialogue titled “From Eclecticism to Doubt,” which outlined their entangled concern, hope, and disappointment in the

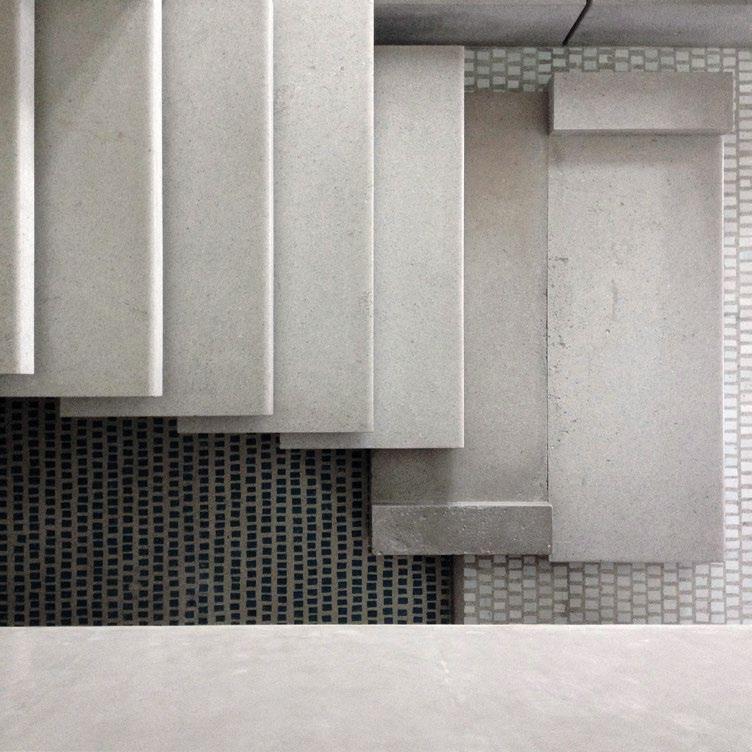

CRAB Studio, Flip-Flop Wall, Kai Tak Sports Park, Hong Kong, 2021

opposite : Part of CRAB’s work on the Arts Masterplan for the sports park, the Flip-Flop Wall is a largescale piece of street furniture.

left : The street furniture design transitions between the higher and lower ground, and between the relaxed pace of daily life and the rush of the stadium crowds through the coves casually nestled in a ribbon-like curve.

direction of modernist and functionalist design. Toward the end of the dialogue, Grey says: “The world is full of living references, living symmetries, difficult to find, but real nevertheless. Their [contemporary designers] excessive intellectualism tends to suppress what is marvellous in life … Their rigid precision has made them neglect the beauty of so many forms: spheres, cylinders, undulating and zigzag lines, ellipsoidal lines and straight lines in movement. Their architecture has no soul.”2

Today, contemporary design practice has become obsessed and consumed with and by standardization and all the rectangular forms within in it. There is of course an important place for this, but there also needs to be a connection to Grey and Badovici’s “living references” and “living symmetries.” Rather than encouraging biomimicry, their intention was instead to encourage designers to look to the world: how people live, how they move, and the shapes the hand sketches when it isn’t intellectualizing every form. In the new absence of ordered ornament, they were calling for marvelous forms full of life that humans can connect with, that make us think about associations, memories, and our bodies as we navigate their curves, nooks, and beauty spots. This is how CRAB Studio began, using just a sheet of ply, some standard legs, a tin of paint, and a jigsaw. 2

Notes

1. Sara Ahmed, Queer Use, Feministkilljoys blog, 2018: https://feministkilljoys.com/2018/11/08/ queer-use/.

2. Eileen Grey and Jean Badovici, De l’eclectisme au doute, Altamira (Paris), 1994, p. 5.

Text © 2025 Axiomatic Editions. Images © CRAB Studio