ORO Editions

NOSEI

AURELIA WIGGINS

INTRO DUC TION ORO Editions

1. Roberto Lambarelli, conversation with Annina Nosei, “Il Faut que tu te transforme en argent,” Arte e Critica no 78 (2014): 60-63; and Roberto Lambarelli, conversation with Annina Nosei, “Il Faut que tu te transforme en argent #2,” Arte e Critica , no. 94 (2019): 46-67.

2. Clement Greenberg wrote to the effect that at the bottom of such cultural phenomena, applicable to such thoroughly different artists, is the pain associated with them: “Why the public is so fascinated by the spectacle of this kind of suffering cannot be discussed here. Suffice it to say that the completeness with which Pollock appears to have exemplified the syndrome of the artiste maudit has invested his legend with a resonance like that of Van Gogh’s and Modigliani’s.” Clement Greenberg, “The Jackson Pollock Market Soars,” The Collected Essays and Criticism, Volume 4: Modernism with a Vengeance, 1957-1969 ed. by John O’Brian (The University of Chicago Press, 1993), 107-114 (114).

The idea of this book arose out of two conversations published in Arte e Critica . The first of these originated in a desire to record Annina Nosei’s account of her activities in the New York art scene of the 1980s. The second, arriving some time later, served to recount her formative years and her professional beginnings.¹ This second conversation was prompted by Nosei’s irritation at an unsettling recent development. In an interview that had appeared in precisely that period, a noted art-world personality had expressed opinions that misrepresented her relationship with Jean-Michel Basquiat. It does not require great familiarity with the vicissitudes of art to know that a fullyfledged mythos has arisen around the figure of Basquiat, a late addition to those myths that every so often cement themselves in the art world. Just as it would suffice to skim through the vast mass of publications fuelling that myth to affirm the importance of Annina Nosei’s role in the painter’s meteoric rise.

The fact remains that in the declarations of that noted personality there once again echoed the old cliché of the artist of genius, the artist at the margins of society, who at some point encounters the bad guy (in this case the white woman) who proceeds to exploit him.²

In Basquiat’s case, the only substance underpinning such a fanciful interpretation is the brutal fact of his story’s epilogue, his tragic death at only 28. But despite the grimness of that end, and while acknowledging the undisputed proof of his talent, one cannot help but recognize that the aspects of his story that have always taken center stage, often speciously, are those best serving the construction of his myth.

The point, however, is that myths fade over time if they are not constantly reinvigorated, continually retold. As Annina knows very well, hailing as she does from a family of philologists, the Greek word mythos means “word” or “story”. For Basquiat, the mainstream press has nurtured and continues to nurture this story, incessantly feeding it while feeding upon

ORO Editions

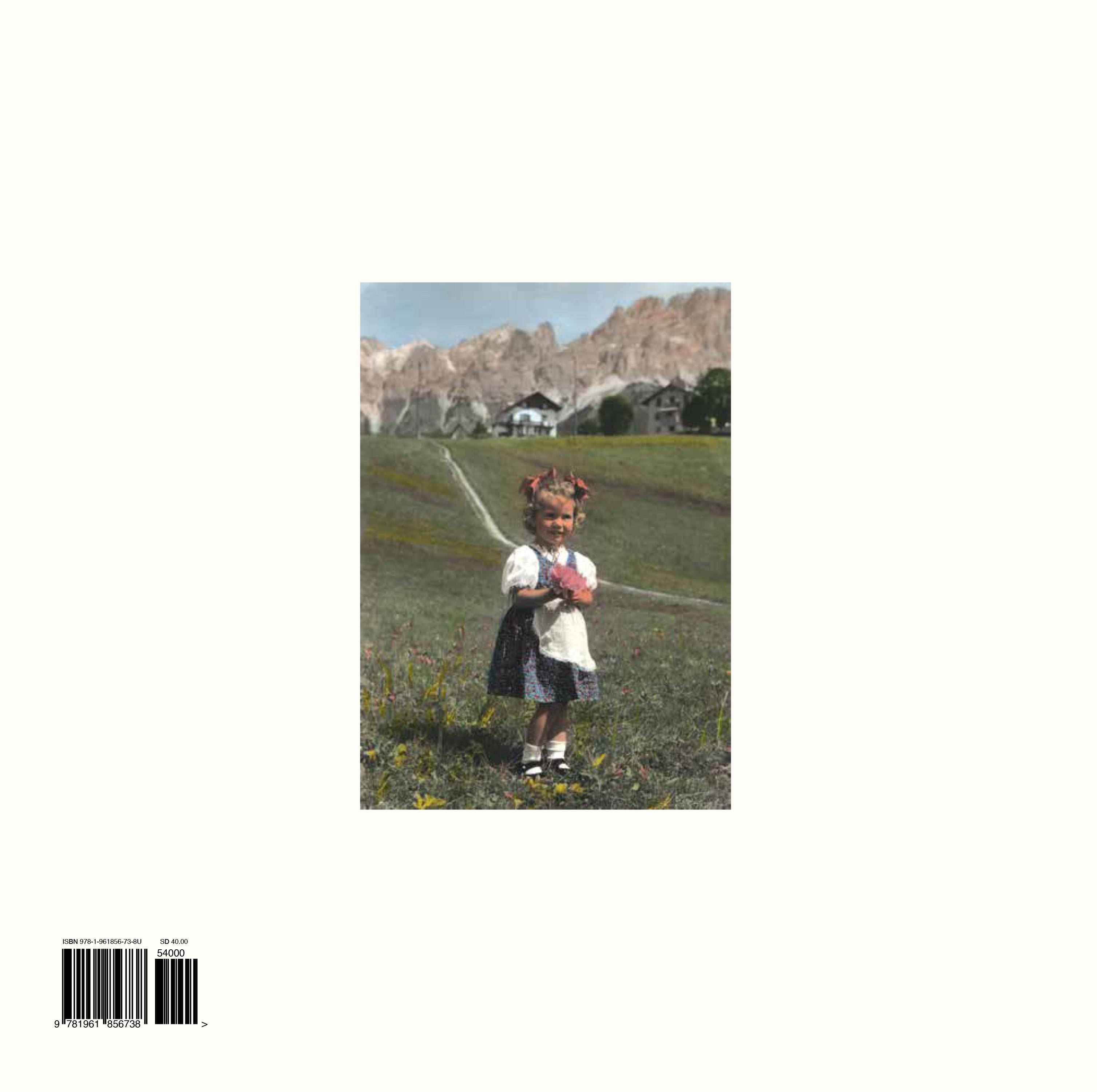

PAOLINA WEBER TO HER MOTHER ANNINA NOSEI ORO Editions

ORO Editions

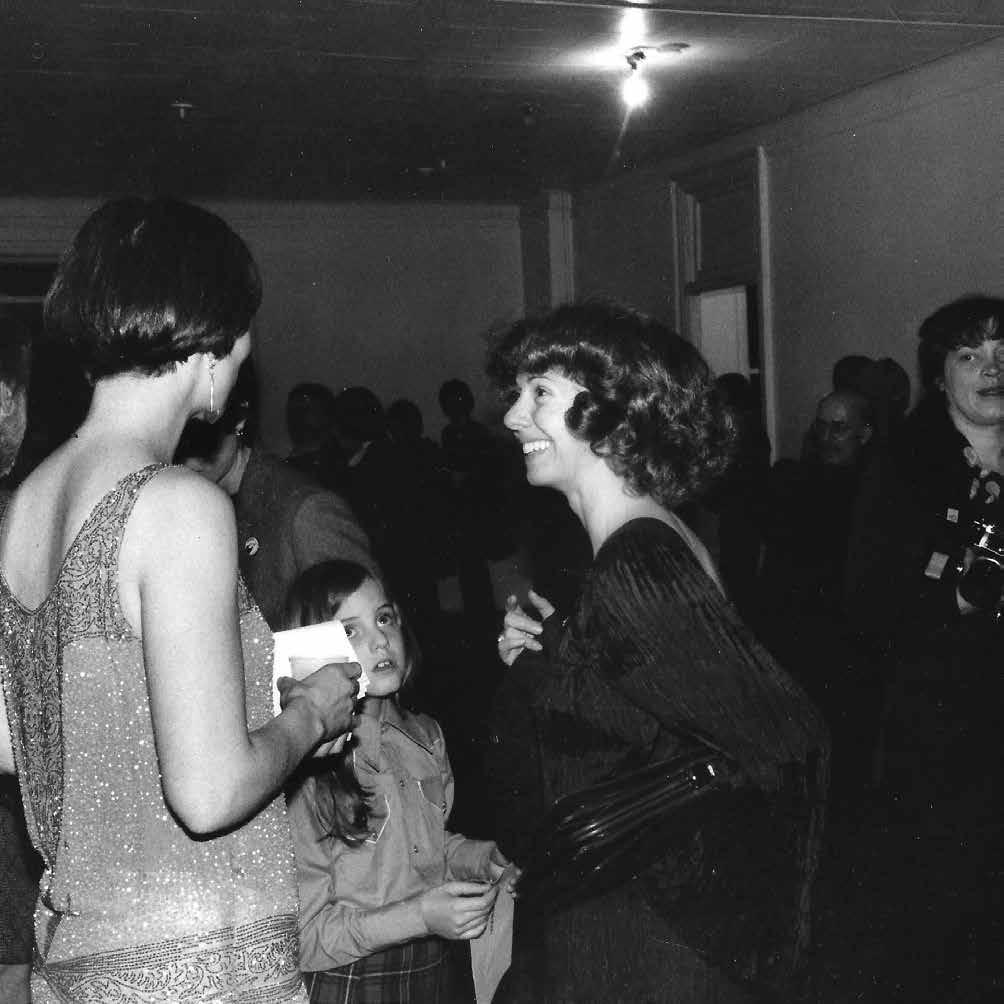

and then participated in Kittyhawk, which was held at the Judson Church in New York. I stayed in Ann Arbor for less than a year, from September ’64 to the summer of ’65. I was hired by UCLA, the University of Los Angeles, in the same year, and during that time I met John Weber, who was director of the Dwan Gallery.

RL: Whom you would then marry... But before that?

AN: Before anything else, I met Carolee Schneemann, who, together with her husband, welcomed me to New York when I arrived on the ship that I had taken in Naples, the Independence . I slipped coming down the catwalk; in short, I arrived in the United States on my backside. Carolee was a great artist. We had always been friends. I had met her in Paris, in Ileana’s gallery, and we had immediately bonded. I had also taken part in a famous Happening of hers, Meat Joy , which was held in Paris and London, and later in New York, at the Judson Church.

RL: Right, that Happening which took place in 1964 as part of the Workshop de la Libre Expression. Schneemann was a standout figure for her work concerning subjectivity, the female body, social questions. So what did you do when you arrived in New York?

AN: For those first few days, before I went to Michigan, Carolee Schneemann hosted me in her loft on 28th Street in New York. I remember that, the morning after my arrival, I went out for a coffee and on my way back a guy followed me all the way into the building. So I grabbed a curling iron and pointed it at him, saying in a firm voice, “This is an Italian gun,” and he ran away.

RL: Circling back to John Weber, how did you meet him?

ORO Editions

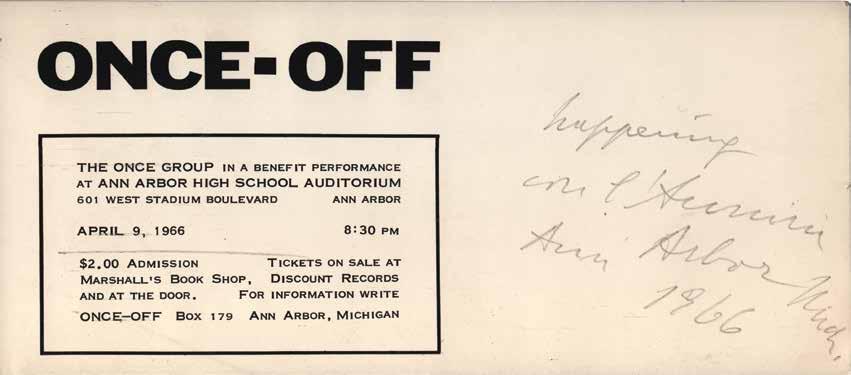

ONCE Group, invitation card to the performance Once-off at Ann Arbor High School Auditorium (9 April 1966).

AN: Rauschenberg introduced us. I had gone to visit him in the gallery, where a Mark di Suvero exhibition was in progress. Actually, the first time I went to the gallery, maybe it was an Ad Reinhardt exhibition on show. The paintings were all black and I thought that it was a tribute to Kennedy’s death.

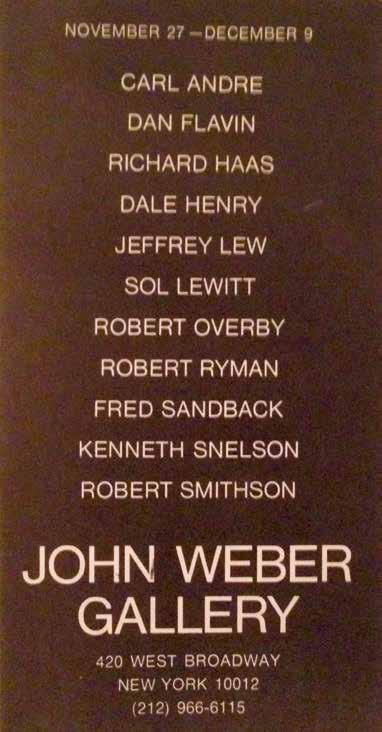

I also saw some wonderful Kienholz works and then the exhibitions of Minimal Art and Carl Andre. I became friends with John and met the artists he worked with. We dated for a year and we were married in October of ’66. We had gone to Italy during the summer.

RL: Tell me something about the wedding.

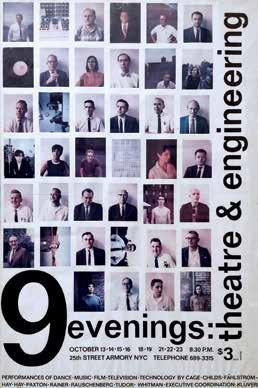

AN: We got married in New York. Christo and Jeanne-Claude organized a big party for us at their home. We also attended an important event during those few days, 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, which Rauschenberg and Billy Klüver had organized along with other artists and engineers at Park Avenue Armory on 69th Street. Dancers like Steve Paxton, the Judson Dance Theater, Robert Whitman, Yvonne Rainer and David Tudor participated. You can imagine how that was for me, the same person who’d taken part in the ONCE Group performances in Ann Arbor and who’d taken part in Ken Dewey’s The Gift in Paris before that; it was a great experience.

RL: While John was organizing important exhibitions at the Dwan Gallery, what were you doing in Los Angeles?

AN: I’d finished my work at the University of Michigan and I’d received an offer to teach at UCLA. I was assistant to a very special professor, Kurt von Meier, who also dealt with music as well as theory and history of art. I held a seminar on Duchamp as part of his course. I was still fresh from

ORO Editions

Poster for the performance program 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering , New York, October 1966.

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

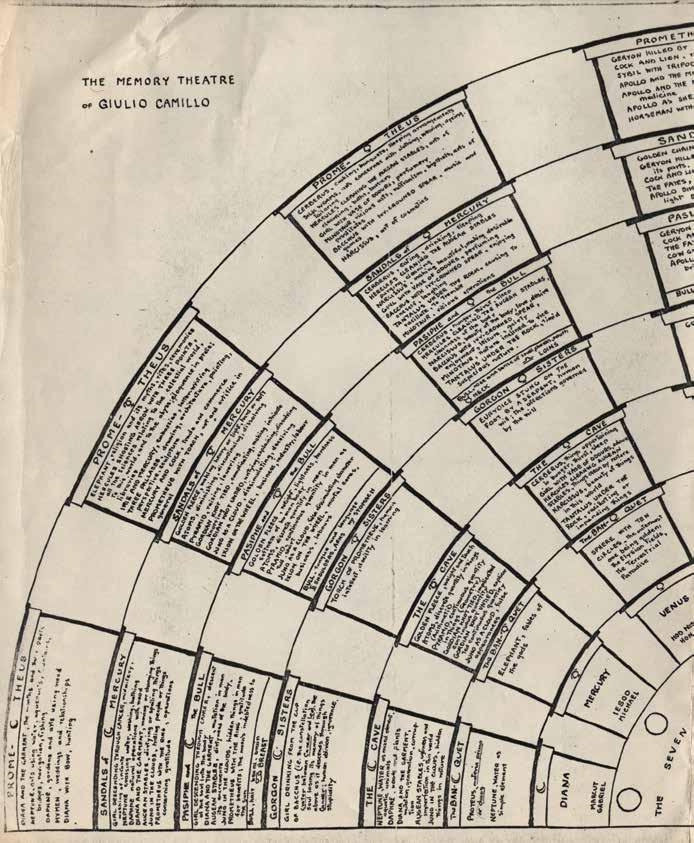

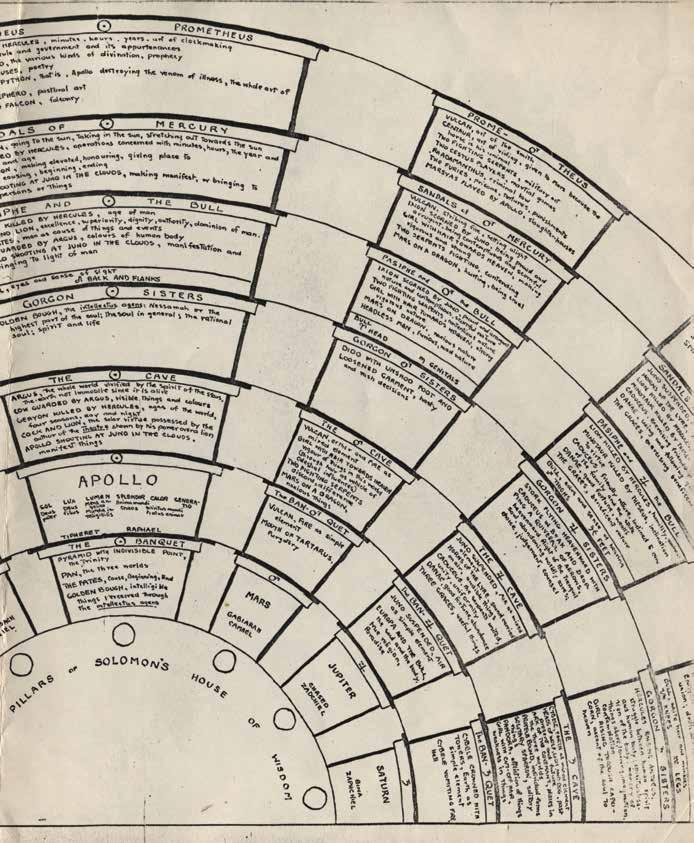

GIULIO CAMILLO’S THEATRE OF MEMORY, USED IN THE POSTER FOR THE EXHIBITION MEMORY AT C SPACE (drawing by Cynthia Chapin) New York, 1977

ORO Editions

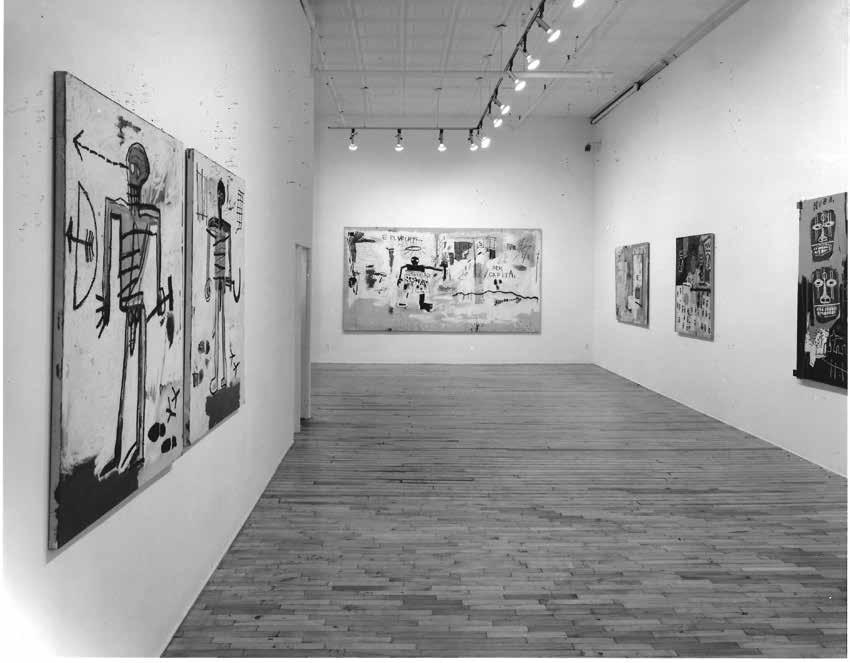

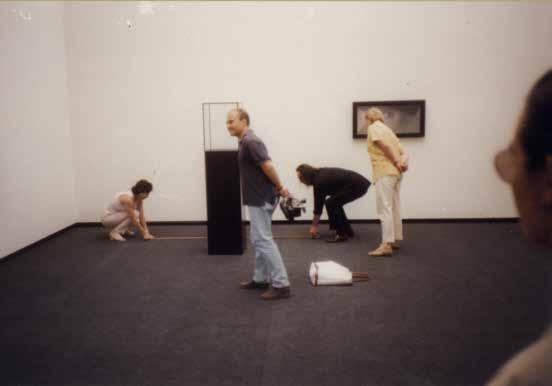

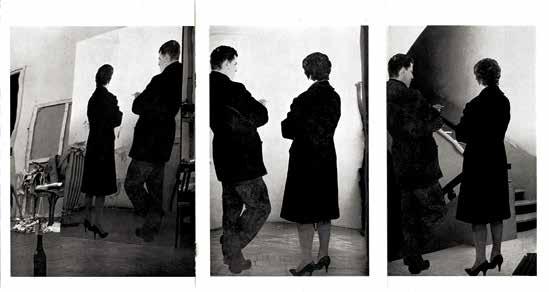

TWO INSTALLATION VIEWS OF THE MEMORIAL EXHIBITION THAT ANNINA DEDICATED TO JEAN-MICHEL BASQUIAT AFTER HIS DEATH.

DECEMBER 1988

ANNINA NOSEI GALLERY, NEW YORK,

ORO Editions

last time I’d done it had been in 2015. I scheduled an appointment and I went. Seeing 5th Avenue completely deserted and the shops closed was striking: it called World War Two to mind and I thought that maybe the Third had begun.

I’d bought the watch in Paris in 1985, as it says on the receipt, which I still have. Over that period I’d given Sabina Mirri the use of my apartment in Via Flaminia, but whenever I returned to Rome I still stayed there regardless. The living room had become her study. Her great friend Gino De Dominicis was often with us. Once we decided to go to Paris together, but Gino didn’t take planes and so we went by train. It was during that trip that I decided to buy a Cartier watch, a purchase that was important to me. When we arrived in Paris, we went to Cartier together and I bought it. Back at the hotel, we arranged to meet at noon the following day at a famous café, Les Deux Magots. The next morning I realized that the watch I’d bought wasn’t what I wanted. It was a round-faced watch when I wanted a Panthère, a square-faced watch. So first I went to change it and then I went to the midday appointment. We sat down for breakfast and Gino asked me if I was happy with the watch and I told him that I’d replaced it with a Panthère, a square-faced watch. Gino started abruptly in his chair and said to me, “Are you crazy? What’ve you done? You’ll never be able to read the minutes, the hand’ll never make it around the corners.” But then again, Gino De Dominicis always had a very particular relationship with squares. His famous video Tentativo di formare quadrati invece di cerchi attorno a una pietra che cade nell’acqua (Attempt to Form Squares Instead of Circles around a Stone Falling in Water) from 1969 shows him throwing stones into the water for the entire duration in an attempt to form squares instead of circles, which is of course impossible. To Gino, it represented proof of the impossibility of forming squares. The first time he showed it to me, he said to me, “See? You can’t create squares, but only and exclusively circles.”

ORO Editions

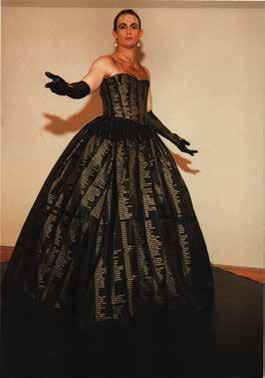

A flyer for Sabina Mirri exhibition and Hunter Reynolds aka Patina du Prey, Annina’s assistant, early 1990s.

RL: Now that you mention it, I don’t know if his was really an aversion to squares. But if so, he also had an aversion toward cubes – I’m reminded of the invisible cube reduced to a square marked on the ground.

AN: Well, continuing to meditate on squares, I recall another episode, linked to one of his works exhibited at the Venice Biennale, I don’t remember exactly in which edition. The work consisted of a glass cube with another cube inside it. A work that had something incredible about it, with the second cube floating within the first. I visited the Biennale before it was open to the public. Rosma Scuteri was with me and we went with Gino to see his space. Gino got furious over the fact that the installation had been set up in such a way as people could touch it. A girl, the room attendant, was on the verge of tears, so I told Gino to calm down. I asked a clerk for some duct tape and I laid it on the floor around the cube so that people would understand that it wasn’t possible to go beyond that point and therefore wouldn’t get too close to the cube. I traced a square, but that time Gino was very happy with it.

RL: The oddities that we talked about with regard to the 1980s stemmed in large part from the attitudes of the artists of the previous generation. Remember when we worked toward a book project on Chuck Connelly?

AN: Of course I remember. By mentioning Connelly, you remind me of an episode involving both him and my assistant at the time, Hunter Reynolds. I don’t know if I’ve ever told you about him. Hunter was an artist who used the stage name Patina du Prey, but I wasn’t aware of that artistic dimension to him, of Patina du Prey. With those very elegant women’s dresses, he slipped into a fantastic character. Performing as Patina du Prey was his job. Over all the time that he worked in the gallery, he never told me. He was a very tall, muscular man, and from his looks you certainly wouldn’t

ORO Editions

Annina and Gino De Dominicis place a square on the floor around the artist’s work during the preview of the Venice Biennale, 1990.

A COSMO POLITAN STORY ORO Editions

ORO Editions

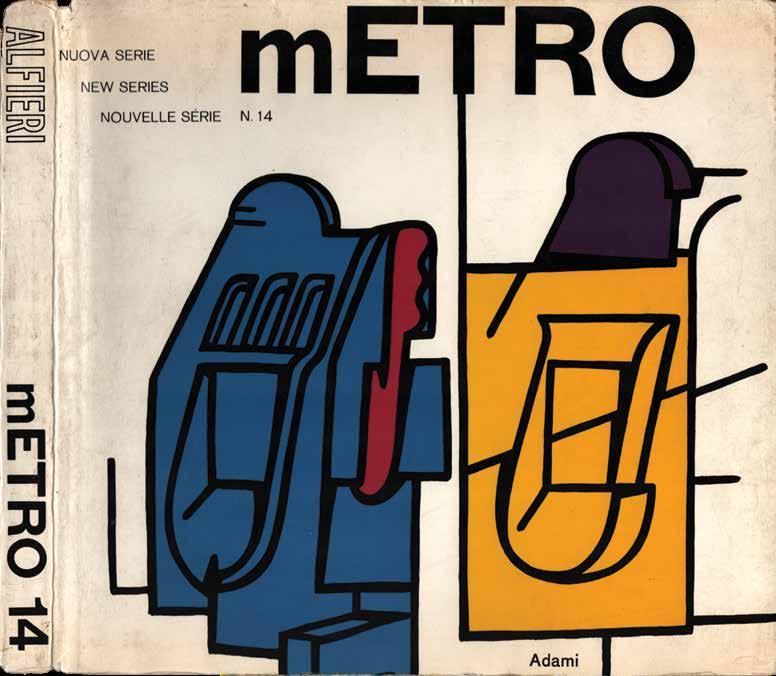

THE SURVEY FOR METRO MAGAZINE

This discussion has continued to make general reference to European artists, which is true to its subject, but it should be clarified that international attention was primarily geared toward French artists even in the late sixties; the preeminent axis reached between the United States and Paris, not to Rome and nor to Berlin. Reflecting this were the activities of the Dwan Gallery, which exhibited the Nouveaux Réalistes in Los Angeles or those that Sonnabend pursued in the French capital, despite the interest that she had shown in Italian artists. Annina was not immune to such an attitude either, as demonstrated by an article-survey that she conducted with Otto Hahn for the magazine Metro . She was charged with procuring and commenting on a series of statements from American artists, while Hahn dedicated himself to their French counterparts.

It was 1968. The developments that distinguished that year also made of it a symbol: a year of protest. There was no longer simply the question of renewing art forms. The challenge, which had become global, was no longer directed only at cultural traditions but was brashly pitched against all institutions.

Already the opening gambit of Annina’s survey left no room for confusion. She asked the artists, “Can the current language of artistic expression in the U.S. be said to challenge the system?” A query that left no loopholes, placing language – that is, the new forms that art had taken over the decade – directly at the heart of the question, and placing it in direct connection to “a challenge to the system”. It therefore addressed artists and their awareness of being called to perform an important function for society, which was to construct an ideological vision that departed from art and included aesthetics, politics, and social concerns.31

The events associated with 1968 decidedly sharpened the tone of the debate. Americans campaigned against the war in Vietnam, against racial discrimination and for the recognition of women’s rights; the French rebelled against the conditions dictated by the Gaullist regime. Young people everywhere sought a radical transformation of society, fighting their fiercest battles for freedom, beginning with free love and liberation from cultural mores, perceived as prerequisites for real renewal. Art had to reckon with the winds of change already betokened by avant-garde art and rekindled by the culture from which Happenings were born. 1968, then, made the taking of positions unavoidable, and it was on this theme that Annina questioned her chosen artists, inquiring whether art could constitute a form and a standpoint from which to challenge the system. Her questionnaire arose amidst a climate of suspicion towards the art system – which is to say, those artists who still responded to market demands. To remain within that system and languish in the rut of tradition, however modern that tradition might have been, was to give a weak, morally indefensible response. If the Metro survey still fell within the prism of Franco-American relations, the circumstances gradually asserting themselves in fact soon eclipsed the question. It was no longer to be a question of subverting

the primacy of Paris, which by that date the Americans had largely achieved through their setting of new worldwide trends (Pop, Op, and Minimal Art), but of facing new balances of power. With 1968, art acquired a greater political and social charge, which reinvigorated European culture and artistic expression. Although, as previously observed, “The end of the old Paris-New York feud resolved itself into a form of internationalism centered on New York but with intense peripheral activity in Germany, Italy, England, and the rest of France,” in practice the American scene opened up to Europeans, who had an edge in terms of ideological rigor.32

“La

del

sulla situazione artistica attuale negli Stati Uniti e in Francia,” Metro n.s., no. 14 (1968): page numbers, 232 in this volume. The artists whom Annina consulted were: Allan Kaprow, Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, Robert Smithson, Dan Graham, Billy Klüver, and E.A.T.

ORO Editions

32. Grégoire Müller, La nuova avanguardia: Introduzione all’arte degli anni Settanta (Alfieri, 1972), 5.

31. Annina Nosei Weber e Otto Hahn,

sfida

sistema: Inchiesta

ORO Editions

COVER OF ISSUE 14 (NEW SERIES) OF THE MAGAZINE METRO (1968), IN WHICH ANNINA AND OTTO HAHN’S INQUIRY WAS PUBLISHED

ORO Editions

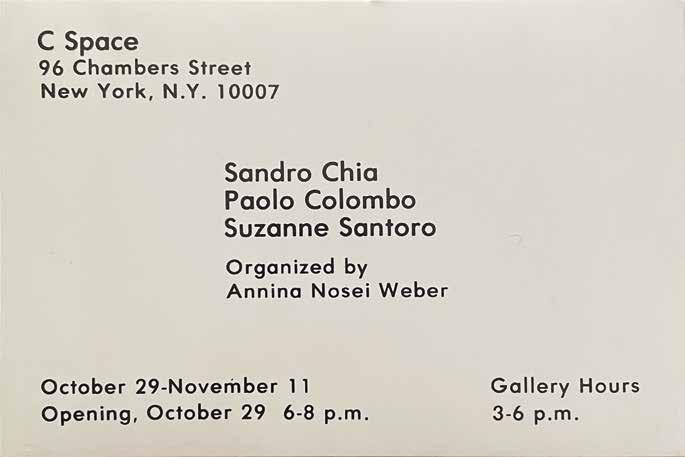

CHIA, PAOLO COLOMBO, SUZANNE SANTORO, CURATED BY ANNINA FOR C SPACE, NEW YORK,

PISTOLETTO

Annina Nosei, “Pistoletto,” Collage , no.2, Palermo, March 1964. Reproduced in the catalogue to the exhibition Pistoletto at the Forte del Belvedere, Florence, 1984. Transcription of the text reproduced in Florence, 1984.

Our every experience, considered in a moment isolated from our lives, in the present, constitutes a point of reference for the past and the future. This point of reference, utterly denuded of all that fills it, is a filter through which to sift through memory and the present. It is in this way that Pistoletto, in the specular surface of his artworks, traps an instant of our vision of the present: an instant that eludes our empirical vision and yet is here frozen, precisely so as to metaphorically embody the visual sieve that corresponds to the fixed mirror of awareness. His works present themselves as naked panels of stainless steel, polished to a mirror-shine. Carefully drawn and finished silhouettes have then been glued to these mirrors, apparently serving the sole function of adapting them to our eye and distinguishing spatial reality from the reality that they reflect. Before this naked visual sieve, we cannot but see our own presence, yet our present is one both unreal and real at once; which is part of a judgement and a narrative. It is through the total sacrifice of every pictorial measure, the abandonment of every pretense at execution (color, gesture, expression) that the painter, trained for an excessive attention to such pictorial means (having begun as a restorer under his father), has succeeded in making his works into that “visual sieve through which to measure past, present and future.”

Here the complete sacrifice of painting has been carried to a metaphysical extent (while it is probably to the Scuola Metafisica that Pistoletto, who lives in Turin, has referred).

It is with extreme austerity that this rejection of every expressive device has been accomplished, if the enterprise is compared to the efforts of other painters who have shared his pursuit of objectivity. In Pistoletto’s case, the revelation is wrought through the simple veil of vision, and the vision in question is that of reality. The most obscure of allegories is rendered transparent though the simplest of stratagems: reality is unraveled from its mirrored identity. The artist repudiates himself as artist and denies the public every projection of artistry; all that remains to us is the reality of ourselves. Ourselves reflected in the artwork, condemned to form a part of it, to be purified and judged through the mirror of our awareness. In observing ourselves and our reality, our metric is necessarily the void. Its silence and freedom cannot be stripped from the dialogue underway, on account of which, space – modified and mystified in the mirror – loses its dimensions, multiplies itself infinitely and catches itself in time. Time within these works thus becomes a dimension of consciousness.

In Luigi Carluccio’s words: “It is possible to convince ourselves that the machination enacted by Pistoletto is a bid for the accomplishment of an absolute example of that commingling of space and time dreamed of by so many of today’s aesthetes.” The point of departure, before giving way to utter reality, is necessarily the void, the naked mirror. All that remains, the qualifying necessity, is the image of a person or an object, attained by the careful pasting onto the panel of a silhouette

ORO Editions

Three pages from the catalogue for Michelangelo Pistoletto’s solo exhibition, Galerie Ileana Sonnabend, Paris 1964.

of outlines derived from photographic enlargements at life scale. The two planes (that of the collage and that of the panel) become fused; they are no more than an initial plane, an unreal division, something between “a simulacrum and the simulacrum of a simulacrum” (in the words of Alain Jouffroy, from his essay for Pistoletto’s March 1964 exhibition at the Sonnabend Gallery in Paris). The pasted silhouettes, however, give the impression of being in the foreground; their life-scale dimensions, their somewhat shadowed, monochrome execution and their opaque radiance all project them outward, beyond the gleaming surfaces. And these surfaces, fixed in the figures, vary continuously elsewhere, reflecting continuously mobile space. The figures become a balance of mobility and spatiality. It is surprising to consider that there can never be a definitive vision of these artworks. Duchamp’s La Mariée comes to mind, the piece that summarizes the artist’s work, constructed from glass, transparent, open to the fluctuations of reality. But a work of Pistoletto is not “a lunar projection of an invisible form, its dimensions necessarily reduced a step, just as a shadow is the projection of a three-dimensional object” (as is the Large Glass ). They are a projection of the visible real – of which, however, the difference, the variation in dimensions, casts a veil of allegorical mystification. In Duchamp’s Mariée , painting invades real space; Duchamp, too, worked through transparency. Here it is the world that invades painting. Alice’s greeting in the mirror remains suspended at the margins of the anonymous, quotidian, aleatoric figures whom Pistoletto presents. Destroying every possibility of Surrealism, he delivers us to the ordinary once more, to our “voie

habituelle.” And that is the truest message of the works of Pistoletto, who does not want us to contemplate but the objectivity of the real world. The objectivity of the random present, of fleeting reality, of naked reality, stripped of its uniform (to cite Duchamp’s Large Glass : the “cemetery of uniforms and liveries”). It is this pursuit of absolute objectivity and this complete immersion in the reality of objects that situates Pistoletto’s works in the same ambit as pop art. Reflected, objects reintroduce themselves as such, in all their banality and vulgarity. As he himself has said: “I cannot make a critical comparison between my work and Pop Art, because the process that I followed to arrive at these works is independent of that followed by the American painters. However, when their work was brought to my attention I was surprised and satisfied to find that their work and that “objectivity” interested me [...]. This objectivity is the consequence of the needs of current art [...]. I do not believe in any form of invention or use of the imagination [...]. An art that expresses personal sentiment does not exist. I am more interested in understanding what I see when I first get up in the morning: my things... a bottle... the things that make me up, the reality around me, rather than to continue my dream of that night [...]. I owe the mirror in my works not merely to my own needs but to a specific position. It is the void in which the entirety of reality dwells... It is the form and the boundary to which I am confined.”

ORO Editions

ORO Editions

DANIELE GALLIANO

forms in a number of his compositions. In Basquiat’s painting, a nail appears to have penetrated the body and similarly the left foot of the figure has a broken chain behind it. Details like these evoke ironworks such as shackles and other torture tools endured by the slaves, which are also found in Vodou rites.

One of Jean-Michel’s late paintings, Riding With Death from 1988, is comprised of a starkly empty background roughly painted in gold, surrounding a lone rider mounted on a skeletal creature. This looming solitude or sudden silence of pictorial space are present in some of the late paintings by Lam, and that economy of visual impact reflects a focus and a clarity that both artists had accomplished, one that most other artists of that time had not, including Picasso. Even in American modern and contemporary art of the time, except for Pop art in the manner of Warhol where there was just a graphic image, there was still a sense of a background that “housed” images or signs. This silence of space surrounding a solitary figure in the mature oeuvre of these two artists is unique to their work and distinguished their practice, now and then.

Over the years of our friendship, Jean-Michel gave me presents here and there; some of them were more meaningful than others. For instance, in 1988 he gave me a cube that had collaged pictures on it, one of which was an image of a mother and child. Underneath it he wrote, “Thank you Anina,” which was intended to show recognition and gratitude, because I had been sort of a mother figure to him. The last time I saw him, in 1988, he gave me a poster showing his portrait which he had signed “To Anina, with love 1988,” which was unfortunately the last time I saw him. But at the very beginning of our working relationship, he gave me two presents, which are still meaningful to me. One was a little booklet on Duchamp, and for a 19 year-old to give me such a sophisticated present, was remarkable. Another present that he liked – and was so amused when giving it to me – was a little African statuette made from wood. It is similar to and perhaps a source for some of his drawings, while reminding us of Lam’s own avid collecting of tribal artifacts such as the many statuettes and masks he gathered at his studio. I will always remember Jean-Michel’s generosity of spirit, his exceptional talent, and unique vision.

AURELIA ORO Editions

This text was published in the catalogue unknown + Galliano: BAD TRIP , Galleria In Arco, Turin, 2014.

My granddaughter Aurelia, when she was six years old, had to say something the first day of school. 14 children on a carpet, she raised her hand and said: “Art does not have to be about something, because there is abstract art.” I guess that Daniele Galliano’s work is not abstract art, it is about “something”: that something is in a way foreign to me, but I found that – in the paintings of Daniele Galliano – instead that something was always strongly “present.” I never was at a “rave” and I do not like pop music, I read Pavese, but I do not know Turin, the people of Daniele’s paintings are probably those with whom I hope Aurelia will not spend time (I hope for more joyful times for her). But each time, in front of those paintings I found myself in a compelling and interesting reality. The actuality of the instant, the insistence of time has been projected into painting through Daniele Galliano’s miraculous ability.