An Instinct to Draw: John Ruskin’s Drawings in the Ashmolean Museum

Copyright © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford, 2021

Stephen Wildman has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this work

British Library Cataloguing in Publications Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-1-910807-45-3

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording or any storage and retrieval system, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher.

Designed by Stephen Hebron

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Gomer Press

Frontispiece: John Ruskin by Sir John Everett Millais, 1853–4. Oil on canvas. WA 2013.67.

Opposite: Study of an Ear of Wheat: Side View (68).

For further details of Ashmolean titles please visit: www.ashmolean.org/shop

In memory of Gerald Taylor (1923–2015), Assistant Keeper in the Department of Fine (later Western) Art, Ashmolean Museum, 1948–1990

Acknowledgements

Catherine Bradley

James Dearden

Colin Harrison

Stephen Hebron

Carrie Hickman

Declan McCarthy

Caroline Palmer

Katherine Wodehouse

Opposite: Detail of Copy of Bernardino Luini’s Fresco of St Catherine of Alexandria (39)

Having written the last of his exhibition reviews, Academy Notes, in 1859 and completed Modern Painters in 1860, Ruskin was able to enjoy wider concerns in the following decade. The hostile reaction to Unto This Last, his denunciation of laissez-faire economics, published as a book in 1862, caused him to contemplate living in Switzerland, occasioning several visits to the Alps in the next few years and a multitude of drawings (48–53). There were also returns to his beloved French cathedrals (25 and 26) and Italian cities, including Venice and Verona (19, 27–9). Significant to these visits, extending into the 1870s, was the study of Old Master painting, especially of the early Renaissance. In 1862 he took Edward Burne-Jones (1833-1896) and his young wife Georgie (effectively his surrogate children) to Milan, where both made copies from frescoes by Bernardino Luini; in Florence he explored the work of artists including Filippo Lippi (38) and in Venice Tintoretto (34) and Carpaccio (33, 40–1). With the exception of Luini’s St Catherine (39), which took him weeks of work and would later preside over the Drawing School, Ruskin took in each case an unconventional view: as in the complementary books and lectures, he chose to focus on telling detail to stand for the significance and humanity of the larger work of art.

Ruskin’s earliest surviving diary, for the continental tour of 1835, contains some drawings, but illustrative only of geological formations, reflecting one of his earliest and most abiding interests. Later, more mature diary notebooks commonly include drawings of many other subjects, as he was ‘interested in everything, from clouds to lichens’.10 Clouds he never tired of observing (56–8), while botany was another lifelong passion, underlying the regular practice of drawing a plant, a leaf or a stone brought in from a walk before breakfast. Although realising that a great artist such as Turner had no time for botanical detail – ‘there is a wide distinction, in general, between flower-loving minds and minds of the highest order’ – Ruskin could not resist the attraction of flowers, either from the view of an enthusiastic amateur botanist or on a more human, even sentimental level; he continued that:

flowers seem intended for the solace of ordinary humanity: children love them; quiet, tender, contented ordinary people love them as they grow; luxurious and disorderly people rejoice in them gathered: they are the cottager’s treasure; and in the crowded town, mark, as with a little broken fragment of rainbow, the windows of the workers in whose heart rests the covenant of peace.11

As he told Clayton, it was at Chamonix in 1842 that he ‘got really rather fond of flowers’, and it was there two years later that Ruskin undertook his first serious botany, assembling a collection of pressed specimens bound as an album, The Flora of Chamouni (Whitehouse Collection, Lancaster University). Association meant everything to Ruskin, so that even a small asphodel became the ‘Wild Hyacinth of Jura’ (62) and a humble strawberry the ‘Rose of Demeter’ (70). Such highly personal ideas colour his most interesting later book, Proserpina: Studies of Wayside Flowers (1875–86).

While he could be regarded as quite a significant amateur in botany, albeit of an idiosyncratic kind, and was a Fellow of the Geological Society, Ruskin’s interest in other aspects of the natural sciences was more occasional. It has been assumed that his election to the Slade Professorship at Oxford in 1870 provided the impetus for many of the drawings that were to fill the cabinets of the Drawing School which he established, but this is not entirely the case. As well as drawing from taxidermy in the Natural History department of the British Museum, before its move to the new Museum in South Kensington in 1881, Ruskin was a frequent visitor to London Zoo, especially in the late 1860s (75 and 76, 81 and 82), often in the company of his painter friend Henry Stacy Marks.

Many new drawings were added after his election, however. Some were identified as lessons (74) and others derived from later visits to the Alps (45) and Italy (31 and 35), even serving as illustrations to Slade lectures (37) before being added to the teaching collection. In the last active decade of Ruskin’s life between his illness in 1878 and a nearly complete physical and mental collapse in 1889, relatively few drawings were made and none has entered the Oxford collection.

The extent to which the collection was used and the number of students who benefitted from it are beyond the scope of this book. Writing in 1883, Ruskin himself bemoaned that ‘I never succeeded in getting more than two or three of them into my school, even in its palmiest days’.12

There were significant exceptions, however. Selwyn Image (1849–1930), artist, designer and successor to Ruskin as Slade Professor of Fine Art from 1910 to 1916, was a student at New College and an early pupil in the Ruskin Drawing School. His recollections expressed exactly Ruskin’s aims:

What little training I had had before was under the old South Kensington system … under that system the thing was to draw hard outlines, hard as nails. Into such hard outlines I did actually have the audacity to translate this splendid drawing of Ruskin’s [a copy of laurel leaves after Baccio Baldini] … He came around and looked. He said only a few quiet words. Then he took the brush into his hand, and showed me what kind of touch was worth having, what kind of line and form was fine and not fine … Whatever small power of Design I may possess, I date the dawn of it from that lesson.13

Minutes of a meeting of the Curators of the University Galleries for 17 March 1870 record Ruskin’s proposal to add to his 1861 gift of Turner drawings a further collection of examples, together with two other sets of drawings, ‘consisting of (a) Standards … to be 100 of architecture, 100 of painting and sculpture… (b) copies for practice – about 50 in number’. A succinct explanation of Ruskin’s plan in establishing this teaching collection to support his Drawing School has been provided by Robert Hewison:

Opposite: Detail of A Lion’s Profile, from Life (81)

Drawing of Turner’s ‘Hospice of the Great St Bernard’, 1857

Verso: three studies of a Gothic Chapel with a Flèche (? Sainte Chapelle, Paris), and a study of reflections (?)

Pencil, pen and ink, watercolour and bodycolour

23.5 × 29.4 cm

Educational Series, 5th Cabinet

First catalogued: Educational Series, 1st Edition, 1871

WA.RS.ED.110

Ruskin had been familiar with J. M. W. Turner’s watercolours since 1839, when his father bought Richmond Bridge and Hill from the Picturesque Views in England and Wales series. By his own account, the young Ruskin’s earliest acquaintance with the artist’s work came from a birthday gift in 1832 of the poet Samuel Rogers’s Italy (1830), with engravings after Turner and others, investing this copy of one of the book’s illustrations with additional significance.

The only original watercolour for the series not forming part of Turner’s bequest to the nation was acquired by Ruskin in 1856. He subsequently passed it on to the American antiquarian Elias Magoon – possibly disappointed that the figures and dogs were the work of Thomas Stothard and Edwin Landseer – but not before making this copy: a diary entry of 26 January 1857 reads ‘Working on Turner’s St. Bernard all the morning, with much more edification than success’.30 The watercolour formed part of a substantial collection purchased from Magoon by Vassar College, Poughkeepsie, New York State, in 1864.

In a manuscript for a proposed re-organisation of the Educational Series, Ruskin described this as

My own copy of Turner’s vignette of the Great St. Bernard, done absolutely as well as I could; which cannot be said of one in a hundred of my drawings. It is interesting as an exercise, because the accidents of Turner’s rapid wash are all facsimilied by laborious stippling … It is quite one of the first pieces of Turner’s central time. Of its sentiment I think I need not speak.31

Ruskin’s sparing but effective use of bodycolour is most notable in the snow, roofs and window bars. The disposition of the figures is clarified in a tracing of the drawing (WA.RS.RUD .150).

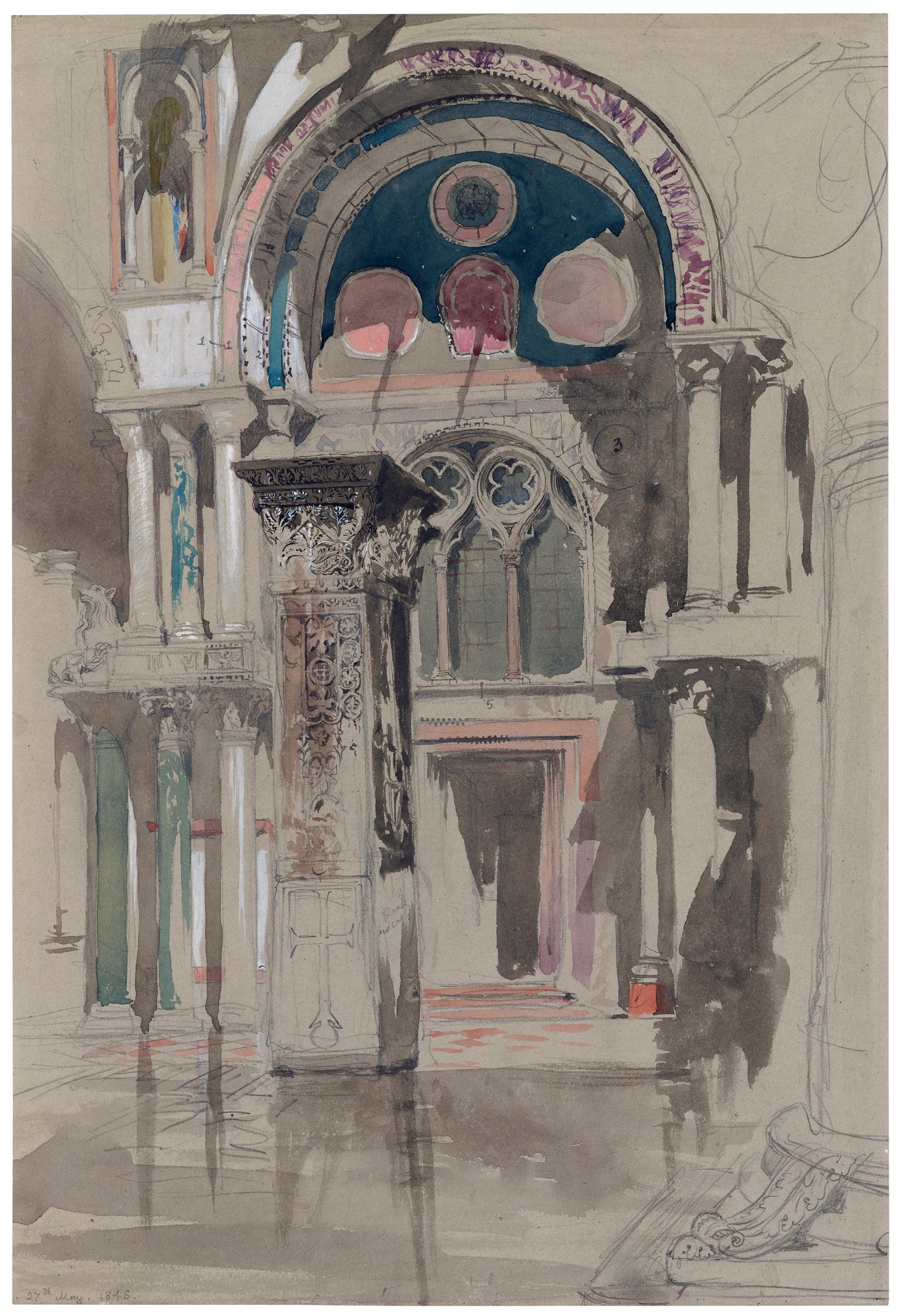

Part of St Mark’s Basilica, Venice: Sketch after Rain, 1846

Pencil, ink, watercolour and bodycolour on grey paper

42.1 × 28.6 cm

Inscribed in pencil: 27th May. 1846.

Educational Series, 9th Cabinet

First catalogued: Educational Series, 1st Edition, 1871

WA.RS.ED.209

Having spent only a week in Venice on their first visit in 1835, Ruskin and his parents enjoyed a longer stay in 1846. The family arrived on 14 May and were to remain until the 28th, travelling to Padua at the start of their return journey. This sparkling watercolour, which Ruskin later called ‘the most beautiful example of Byzantine colour I could give’,53 was made on the day before their departure. There are almost a dozen large architectural drawings from the 1846 tour, featuring sites in Geneva, Verona, Bologna, Florence and Lucca, as well as this sole Venetian subject. They provided a template for the larger individual studies of buildings in Venice made in 1849–50 and now known as ‘worksheets’.

The south façade of St Mark’s Basilica, adjoining the Ducal Palace, became a constant source of interest for Ruskin. Shown here is the lower part of the third bay, behind one of the two sixth-century stone pillars once thought to have come from Acre in Syria but now known to have been part of the church of Saint Polyeuktos in Constantinople, brought to Venice in 1204 as part of the spoils of the Fourth Crusade.

The Baptistery, Florence: Study of the upper Part of the right-hand Compartment on the south-west Façade, 1872

Pencil, watercolour and bodycolour

52 × 34.6 cm

First catalogued: Library Edition, Vol. XXI , 1906

WA.RS.REF.120

One of Ruskin’s most careful and finished architectural studies, this drawing is referred to in the Oxford lecture series of 1874, ‘The Schools of Art in Florence’. Here he describes it as the most exquisite piece of proportion I know in the world … I painted, as you may remember, two years ago one compartment of it with the best care I could – never took more pains with a drawing.92

Adjoining the Duomo in Florence, this ancient building had been encased in marble in the eleventh to twelfth centuries: as Ruskin put it simplifying the whole to a mere hexagonal box, like a wooden piece of Tunbridge ware, on the surface of which the eye and intellect are to be interested by the relations of dimension and curve between pieces of encrusting marble of different colours, which have no more to do with the real make of the building than the diaper of a Harlequin’s jacket has to do with his bones.93

Such a direct focus on the flat planes gives a mesmerically two-dimensional interpretation of three-dimensional architecture. In the course of another lecture of 1872 Ruskin also called the Baptistery ‘one piece of large engraving. White substance, cut into, and filled with black, and dark green’.94 He has not neglected to include breaks and scuffs on the stone in the pediment, and within the exacting precision of this astonishing drawing has used swift strokes of a loaded brush as well as sparing touches of bodycolour for highlights in the mouldings.