Sustainable groundwater

management: how much use is sustainable? And how to best ensure it?

RésEAU Brief no.9

November 2025

management: how much use is sustainable? And how to best ensure it?

RésEAU Brief no.9

November 2025

Dear colleagues,

It is with great pleasure that we present the ninth edition of the RésEAU Brief series, a medium to share SDC’s learnings from water-related projects and programmes at the global level. This edition focuses on sustainable groundwater management

Globally, 49% of water withdrawn for domestic use and 43% for irrigation comes from groundwater (Rodella et al., 2023). As the rather invisible twin sister of surface water, groundwater is equally important for reaching SDG 6, across the target for access to drinking water (6.1), the threats to its water quality (6.3), and its relevance for healthy ecosystems (6.6). Target 6.4 specifically calls for an increase in water-use efficiency and for ensuring sustainable withdrawals to address water scarcity. Groundwater use is part of this equation, making data on recharge and abstraction crucial to assess what makes withdrawal sustainable.

Sustainable levels of groundwater use are relevant for human health, food security, ecosystems, and for managing the risks posed by increasingly variable rainfall under climate change

Over the past decade, it is these climate variations that have turned the attention to aquifers, as vast natural water storage reservoirs, with generally good water quality.

Daniel Maselli

SDC RésEAU Focal Point daniel.maselli@eda.admin.ch

Delphine Magara and Bernita Doornbos, Editors RésEAU Brief and backstoppers to the RésEAU delphine.magara@skat.ch bernita.doornbos@helvetas.org

In 2022, scientists and water managers highlighted its importance under the UN Water Year theme Groundwater: Making the invisible visible

Looking at practice, this brief is largely based on insights from the RésEAU’s Learning Journey on Groundwater in 2025. Through a series of three webinars, development practitioners shared experiences from regions including Central Asia, Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Middle East, addressing issues such as groundwater governance, conjunctive management of surface and groundwater, the data and monitoring required, and the specific challenges of managing transboundary aquifers.

Building on these exchanges, this RésEAU Brief highlights SDC initiatives that support national and local water managers in advancing sustainable groundwater use for resilient local livelihoods. It explores how sustainable levels of water use could be defined, and how water users and managers can work together to ensure these levels are maintained. The initial Learning Journey on Groundwater may gradually evolve into a RésEAU Community of Practice on Groundwater.

We wish you a good read and welcome your feedback and comments!

Your ideas matter!

We are committed to addressing the topics that matter most to you. If there is a subject you would like to see covered in future RésEAU Briefs or if you have insights to contribute, please reach out to us!

Though largely hidden from view, groundwater is an important water source for human prosperity. Groundwater accounts for roughly 30% of the global freshwater (Global Climate Observing System) and provides 49% of the household water consumption worldwide and 43% of water withdrawn for irrigation (Rodella et al., 2023). The source is highly appreciated for being perennial, prevalent across landscapes, and for its relatively reliable quantity and quality, as compared to surface water which is easily impacted by weather and short-term external factors.

Globally, groundwater demand is expected to increase, as total water use is expected to increase by 20 to 30% from now to 2050 while surface water availability is seasonally decreasing. Groundwater is hence a key variable in the response to the continuously increasing water demand, especially in emerging, low and middle income countries, as well as to the adaptation to climate change, as a natural body for water storage and distribution (World Bank, 2023).

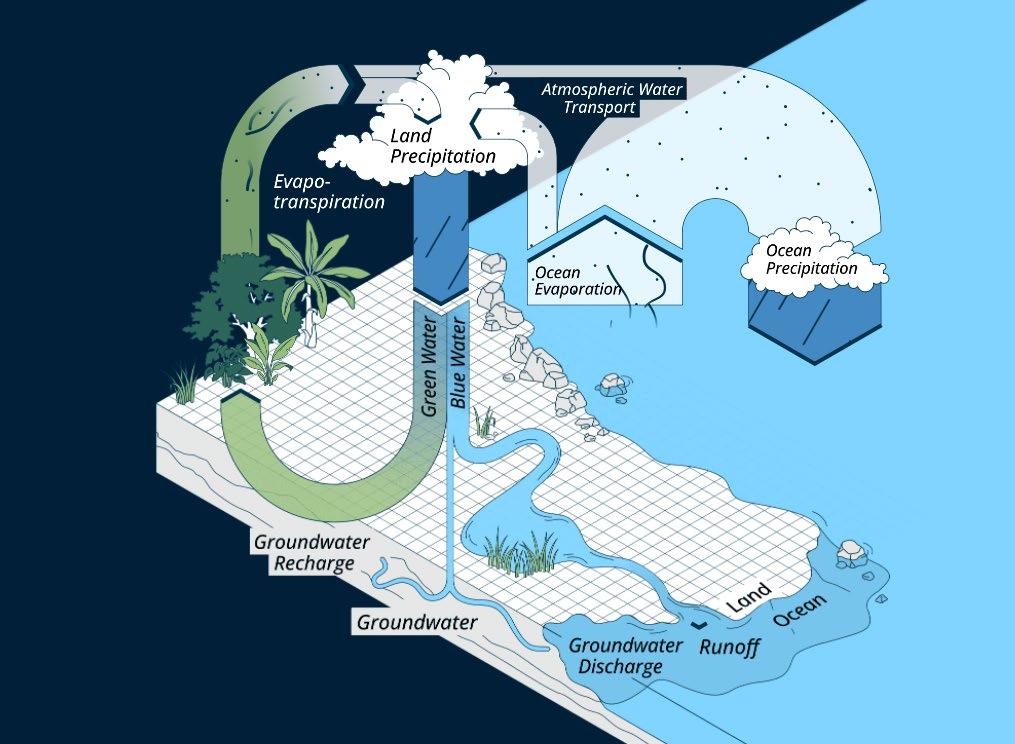

Groundwater and surface water are inherently linked through the hydrological cycle (see Figure 1). Simply put, the freshwater present at the earth’s surface partially originates from groundwater, while surface water allows for aquifers to recharge (Villholth, 2024). Therefore, managing surface water and groundwater must be approached as an integrated system—this is the essence of conjunctive water management (Aureli, 2025).

In contrast to the high stakes associated to this underground resource, insufficient attention is given to its sustainable management, that is: regulating its (over)use to stay within the aquifers’ physical limits. Groundwater abstraction is environmentally sustainable, as long as essential barriers (often groundwater levels) are not transgressed. Sustainable systems cannot support groundwater abstraction exceeding average recharge over a long time (Villholth, 2024).

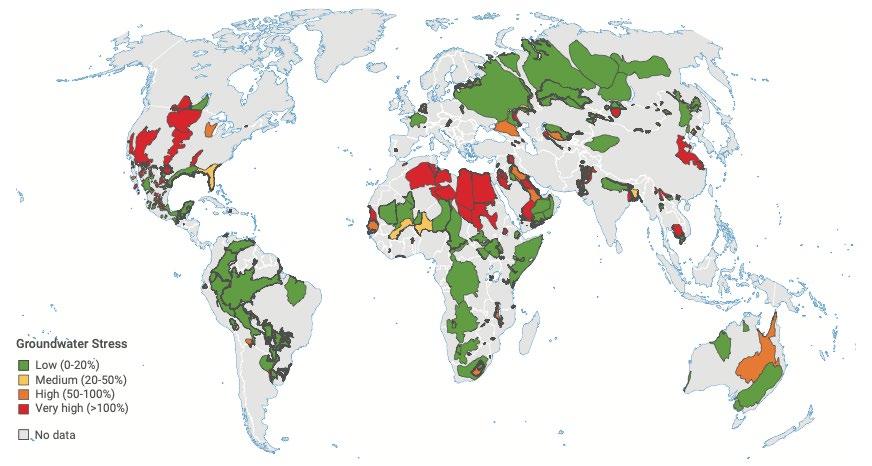

Yet groundwater is under stress globally, and most critically in northern Africa, North America and South and East Asia (see Figure 2). While the global trend points at overexploitation, local circumstances differ widely around the world, with some areas even underexploiting their sources compared to its potential yield, for example in parts of Sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 2: Global water stress of aquifers. Groundwater stress is defined as the ratio of mean annual groundwater withdrawals over the mean annual groundwater recharge ( World Bank , 2023).

The absence of groundwater management has negative and often irreversible consequences. Next to frequently occurring contamination with pesticides, groundwater depletion in particular triggers a chain reaction of salt-water intrusion and land subsidence (World Bank, 2023). To address these problems, the UN Groundwater Summit of 2022 made a Call for action for sustainable groundwater management. The call identified five action areas: securing financing, improving data collection and monitoring, strengthening human and institutional capacity, fostering technological innovations and enhancing groundwater governance1

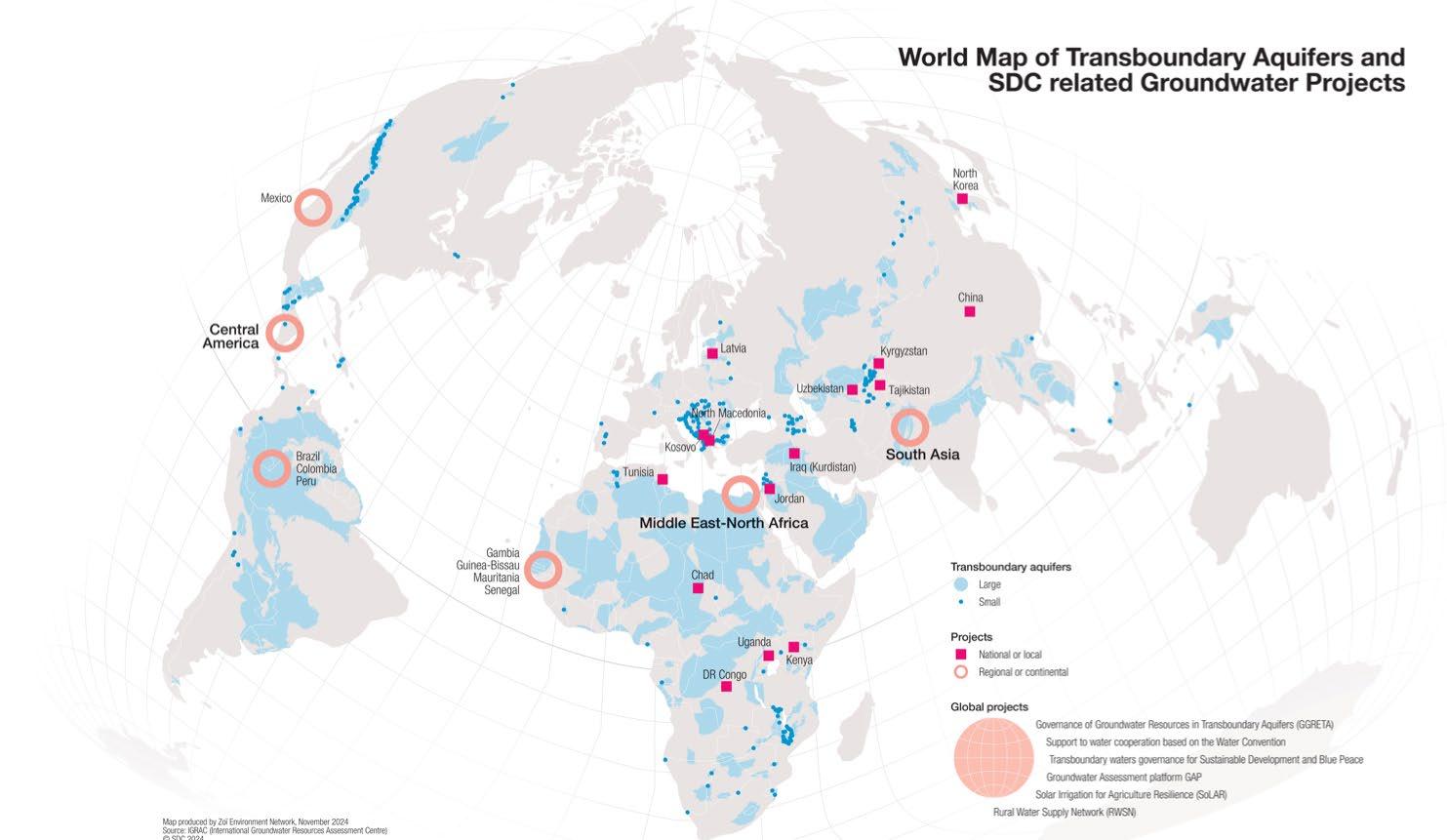

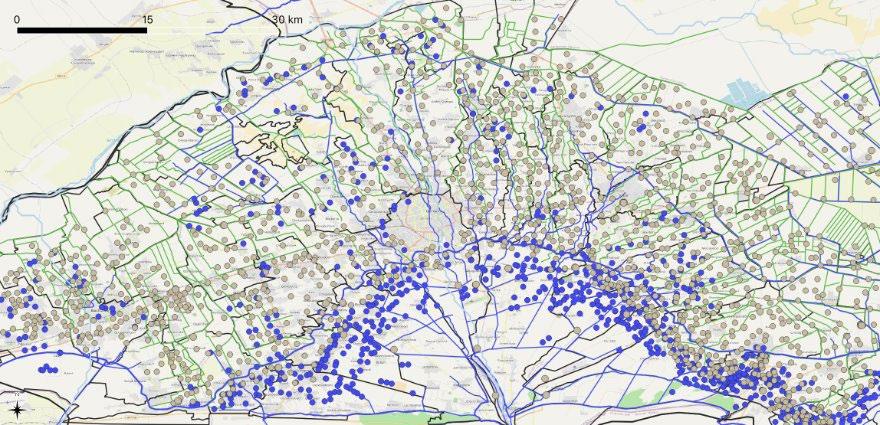

SDC has been actively contributing to good groundwater governance, harnessing the potential of this resource to sustainably deliver water to the most vulnerable people in areas prone to water stress (see Figure 3 for the location of groundwater projects). The following chapters will provide insight into different aspects of sustainable groundwater use, illustrated through examples from recent and ongoing SDC projects. Key questions are how projects can support determining sustainable use levels and how they promote groundwater governance to put sustainable use into practice.

1 Groundwater governance can be defined as the framework encompassing the processes, interactions, and institutions, in which actors (i.e., government, private sector, civil society, academia, etc.) participate and decide on management of groundwater within and across multiple geographic (i.e., sub-national, national, transboundary, and global) and institutional and sectoral levels (Villholth and Conti, 2018).

Figure 3: SDC-related groundwater projects and the world’s transboundary aquifers (SDC , 2024).

Effective groundwater governance begins with the availability of accurate, locally relevant data. Yet groundwater monitoring remains significantly underdeveloped, especially in the Global South (WMO, 2024). Regulating groundwater abstraction requires precise, site-specific data that are regularly updated to determine how much water can be safely extracted from each aquifer.

By measuring the water table levels, groundwater withdrawals and quality at different points of extraction, geohydrologists can assess the type and locations of aquifers, as well as provide indications on how much water can be extracted sustainably over time, without exceeding an aquifer’s long time average recharge (Lictevout, 2025).

As groundwater is an invisible resource with complex flow patterns, monitoring and mapping its key variables are often neglected when establishing extraction points. Its oftentimes challenging accessibility and long residence time as compared to surface water, make assessing groundwater availability at a given location over time both costly and time-consuming (Lictevout, 2025).

SDC programs in Central Asia, Latin America and Sub-Saharan Africa have therefore invested in capacity building and strengthening institutions and tools for mapping and monitoring the hydrogeological landscapes in their intervention areas.

SDC’s initiative El Agua Nos Une (implemented in Peru by CARE Peru and SAVAvida) has developed a comprehensive map for the management of the Rímac river basin in Peru, which includes a groundwater inventory.

As part of this initiative, a measurement protocol and guidelines for interpreting groundwater level and quality data were developed, in collaboration with Peru’s National Water Authority (ANA). A newly developed mobile application allows field specialists to easily collect and monitor water levels and quality in existing wells, verifying geo-references and use licenses, combining different data bases. This innovation has streamlined information management and improved data accessibility across ANA’s departments and its decentralized administrative units at basin level, as well as Lima’s water utility SEDAPAL (Antiporta, 2025).

A cost-effective manner of groundwater abstraction mapping is to use pre-existing boreholes as data measurement and testing points. However, as oftentimes located on private property, they are difficult to access. The SDC-supported program Climate Resilient Integrated Water Resources Management in the Zarafshan River Basin in Uzbekistan addresses this issue by employing remote sensing technologies. Hydrosolutions combines publicly available satellite data on irrigated area with existing locations of groundwater observation points (see Figure 4). This is a practical solution for mapping groundwater use in areas where access to wells for sensor installation, was not feasible (Marti and Siegfried, 2025).

Figure 4: Map of the Zarafshan basin in Uzbekistan illustrating how existing data on groundwater observation points (grey dots, from the Ferghana Basin System Irrigation Administration) and drainage canals (green lines) were combined with remote sensing information on irrigated areas (blue dots) ( Marti and Siegfried, 2025).

The expedient mapping of groundwater in data-scarce humanitarian contexts is challenging yet needed for fast and cost-effective establishment of groundwater-fed supply systems, while preventing overexploitation. With the support of SDC, a Rapid Ground Water Potential Mapping methodology was used in the refugee camp of Bidibidi in Uganda (Bünzli, 2025; Scherrer et al., 2020).

The mapping methodology for locating water extraction points, overlays two variables: groundwater availability (estimated through landscape units) and reservoir capacity or a proxy of hydraulic conductivity (based on geological properties). The overlay is translated into potential groundwater yield ranges, and the corresponding water pump and system size options. Unlike conventional approaches in refugee camps—which often prioritize proximity to users (“drill where the people are”) and result in numerous low-yield boreholes—this method focuses on maximizing water output (“drill where the water is”).

The pilot use of the rapid groundwater potential methodology in Bidibidi shows how a simple geohydrological landscape analysis can guide decisions that lead to fewer boreholes with significantly higher yields. It indicates where the replacement of handpumps with automated, high-capacity systems can be appropriate and where solar-powered pumps can be effective. This light assessment of groundwater availabilities is a potential game-changer for water supply in humanitarian settings—delivering more water, with fewer resources (Bünzli, 2025).

These examples demonstrate innovative approaches to data collection and assessment of groundwater availability and use. However, the cost and complexity of local data remain a barrier in many contexts, underscoring the need for scalable, cost-effective solutions for groundwater data collection and monitoring.

Although recharge volumes exceed extraction at a global scale, it is at the local hotspots of declining groundwater levels, where consequences are real, leading to seawater intrusion, land subsidence, streamflow depletion and wells running dry.

A 2024 global study using groundwater-level data from 170,000 monitoring wells in nearly 1,700 aquifer systems showed that rapid groundwater-level declines (more than 0.5 m per year) are widespread, especially in dry regions with irrigated cropland. This decline has accelerated since 2000 in 30% of the world’s regional aquifers (Jasechko et al., 2024). Groundwater functions as a de facto common-pool resource: it is non-excludable, yet subject to competitive abstraction, such as wealthier farmers who can afford to use deeper wells. Determining sustainable extraction levels is challenging, and subsequent enforcement of usage restrictions is often difficult due to limited monitoring capacity and weak compliance mechanisms (Villholth, 2024).

This section will explore options for the sustainable use of groundwater in terms of quantity, while section 4 will address groundwater quality.

(Fernando, 2016)

Defining the boundaries of what constitutes sustainable use in a particular site is a first key task. Three main options exist, like managing a bank account:

• Sustainable yield: Limit abstractions to no more than the long-term average recharge. “Living off the interest or earnings”

• Mixed strategy: Planned depletion for a limited period followed by abstraction at a sustainable rate. “Spending some of the savings followed by living off the interest or earnings”

• Mining: Long-term progressive depletion, reducing the groundwater reserves over time. “Spending the savings” (UPGrow, 2014).

Defining the sustainable yield option depends on understanding the functioning of the local aquifer and the availability of long-term monitoring data combined with modelling. Yet, it is not only a matter of the science of the resource; it involves decision-making based on the identification of potential consequences of use, and an evaluation of trade-offs and priorities, ideally based on consensus among stakeholders (Villholth, 2024).

“The groundwater in the Jaffna Peninsula is somewhat like the money that is held in a current account in the bank. The rainy season deposits, annually, a fixed amount of water in the limestone aquifer. This is drawn out from the wells during the dry months. The limit for drawing this water is the amount put in the system. Overdrawing leads to disaster.”

Globally, ground water depletion volumes are estimated at 200 km3/year, corresponding to 20% of ground water abstraction. Yet locally this can be up to 100%, where groundwater is mined in non-renewable aquifers (Villholth, 2024).

There are three strategies water users use to cope with depletion:

1. change the water withdrawal efforts: Though slowing down withdrawals makes most sense, in practice water users generally intensify their abstraction by deepening wells and increased pumping.

2. change the use: either by using less water per unit area or by reducing the irrigated area.

3. change the dependence on groundwater, by leaving agriculture (Rodella et al., 2023).

How farmers will react, is linked to the regulatory and incentive structure around groundwater-fed irrigation and agricultural production. This is illustrated by the Sino-Swiss cooperation project Rehabilitation and management strategies of over-pumped aquifers under a changing climate

Agriculture in the Heihe river basin in North China, with only 150 mm rainfall per year, is heavily dependent on irri-

gation. A 1997 policy aimed to reduce surface water use by 50%, inadvertently spurred groundwater use. Policy strategies in response were to a) reduce groundwater abstraction and b) optimize surface water allocation (Wang, 2025).

In 2015, the government, supported by the SDC project on regulating over-pumped aquifers, introduced water fees and metering to quantify and curb water use. A private company was contracted via a public-private partnership, to install and maintain smart meters2 on over 700 wells and manage fee collection. The payment process was streamlined by enabling farmers to pay for water using prepaid cards. Water fees were relatively high and tampering of the smart meters was criminalized.

Initial results showed a 30% reduction in groundwater abstraction volumes between 2016 and 2019. However, by 2020, a rebound effect emerged as farmers expanded their irrigated areas with 13% -despite government prohibitionbringing back use volumes to 2016 levels (Wang, 2025).

This highlights the limitations of fee-based control mechanisms only and the need for a more holistic understanding of water user behaviour. To address this, the project developed a serious game called SavetheWater to simulate farmer responses to different policy scenarios, in combination with farmer surveys (Wang, 2025).

The global spread and reducing cost of new technologies based on solar energy make pumping groundwater affordable to more farmers. Solar power is basically free, so support to solar powered irrigated agriculture risks uncontrolled groundwater depletion. rather than controlling and protecting it (Villholth, 2024).

The Swiss funded Solar Energy for Agriculture Resilience (SoLAR) initiative (implemented by IWMI, 2018-2028) promotes solar energy systems for agriculture in South Asia (Bangladesh and India) and East Africa (Ethiopia and Kenya). The project informs policy frameworks by analysing water-energy-food (WEF) nexus, develops financing mechanisms, and develops capacities, to further scale the use of solar agro-technologies (SDC, 2025).

The project’s first phase has shown that solar irrigation pumps (SIPs) bring many benefits, such as reduced costs and emissions from diesel pumps, and can add 20-35% to farmer income when feeding excess energy into the power grid. Yet, its spread also risks over-extraction of groundwater. The project has therefore analysed the groundwater abstraction behaviour, comparing farmers with and without solar pump systems. The study assessed two implementation models for collective irrigation systems with fee-for-service SIPs in Bangladesh on one hand and grid-connected SIPs in India on the other hand.

In these contexts, solar adoption did not lead to a significant increase in groundwater use compared to diesel pumps. In Bangladesh, operator managed SIPs kept water use in check despite lower costs, though some shift toward more water-intensive dry-season rice was noted. In India, grid-connected SIPs with feed-in incentives reduced water use in alluvial aquifers, while hard-rock systems showed little change. Groundwater impacts are thus context specific and can be avoided with well-designed solar system setup and operative models. When farmers individually own and operate solar pumps, the near-zero marginal cost of water may encourage over-irrigation (Alam et al., 2025).

3.3 Policy options to curb over abstraction and manage recharge

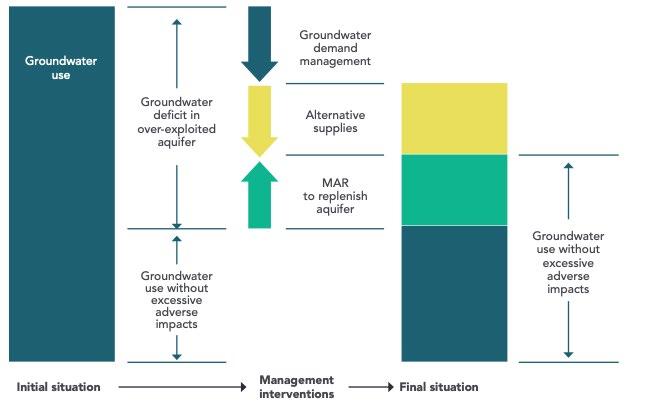

Global analysis shows that groundwater declines can be slowed or reversed through the implementation of groundwater policies (see Figure 6); groundwater demand management, alternative supplies such as surface-water transfers; or the addition of groundwater storage following managed aquifer recharge projects (Jasechko et al., 2024).

Investing in improved data collection, use metering and groundwater monitoring is the basis for managing groundwater. Based on that, several policies can be identified to manage groundwater demand and curb over-abstraction of groundwater:

1. Regulation: establish and enforce regulatory frameworks that limit drilling and abstraction and strengthen permitting and licensing systems.

2. Financial incentives: set pricing mechanisms that reflect scarcity and environmental costs of overuse.

3. Reforming subsidies: review and revise energy and well drilling subsidies to eliminate incentives for over-abstraction (see Rodella et al., 2023).

Figure 6: Combined interventions—demand management, alternative supplies, and Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR)—are needed to move from over-abstraction to sustainable groundwater use ( UNESCO, 2020).

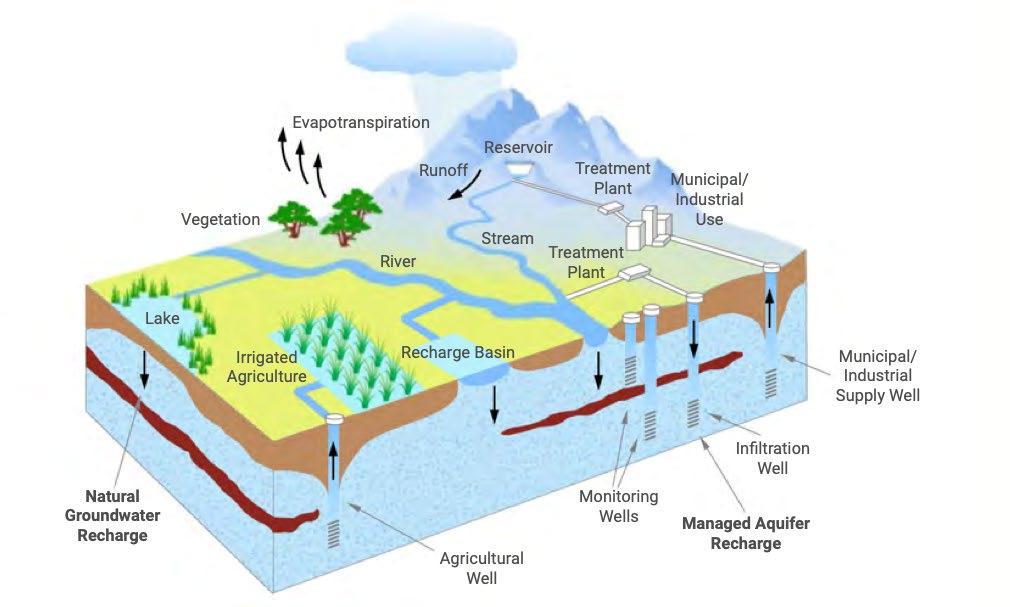

Figure 7: Overview of Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) techniques ( World Bank, 2023).

On the other side of the balance, recharge of groundwater should be enhanced. Nature-based options such as restoring wetlands and forests are paramount. A series of Managed Aquifer Recharge (MAR) techniques exist (see Figure 7), across the range from fully nature-based to human induced recharge methods, applicable from rural to urban areas (World Bank, 2023).

Switzerland has a long history of cooperation supporting integrated watershed management projects aimed at conserving, restoring and managing forest and pasture ecosystems, for water regulation and sustainable local livelihoods.

In various mountain regions, where loss of springs is a disturbing signal of climate change, recharge efforts of

springsheds have been explored and promoted, such as in India (see Climalayas). The Strengthening State Strategies for Climate Action (SCA-Himalaya) project developed a science-based integrated springshed management approach, with guidelines for policy makers and development practitioners (Rathod et al., 2021). In the Andes, the PACC Peru project promoted springshed actions coupled with small earthen reservoirs for water harvesting, both surface storage and to recharge mountain springs as measure to adapt to climate change (PACC Peru, 2014).

Given the promising avenue, yet complex nature of managed aquifer recharge (MAR) methods, RésEAU has produced a dedicated podcast through SDC’s Trend Observatory on Water.

Figure 8: The ‘qocha’ Solimaniyoc in Apurimac, Peru, retains and stores water. Part of the water infiltrates, allowing small springs to maintain and improve their discharge (@Helvetas Peru).

Groundwater quality is as critical as, if not more concerning than, groundwater depletion. Poor quality renders the resource unusable and has multiple environmental impacts. Restoring groundwater quality is costly and requires long-term efforts (Villholth, 2024).

Groundwater pollution has both geogenic (e.g., arsenic, fluoride, and salinity) and anthropogenic causes, the latter being increasingly prevalent and generally preventable. Sources of pollution are ubiquitous. Poorly constructed or maintained on-site sanitation facilities often lead to persistent pathogen contamination of nearby shallow wells, especially in rural areas. Untreated wastewater discharges and seepage from waste sites contaminate urban areas. Agriculture is the primary cause of groundwater pollution in rural areas, through pesticides and fertilizers. Industry, including hydrocarbons and mining, introduces a wide range of pollutants – some of which do not disintegrate and persist in the environment (UN, 2022; World Bank, 2023).

Effective regulation and enforcement to protect groundwater quality are urgently needed across all sectors yet remain rare. Point-source pollution can be regulated through permits and compliance with effluent or

ambient water quality standards. Non-point source pollution requires preventive measures such as land-use regulation and adoption of best agricultural and environmental practices (UN, 2022).

Swiss cooperation efforts on groundwater quality include support to the Swiss Federal Institute of Aquatic Science and Technology Eawag for the Groundwater Assessment Platform. This digital platform shares information and models the presence of geogenic contaminants (fluoride, arsenic) in groundwater globally, with the aim to inform public health risks via drinking water (SDC, 2023:10; SDC, n.d.).

In Jordan, an SDC humanitarian action supported mapping the vulnerability of groundwater quality near five solid waste landfills (SDC, n.d.). Jordan received a large influx of Syrian refugees which increased the volume of solid waste going into landfills. This work informs municipalities about leachate risks when expanding landfills (see Assayed et al., 2023).

The continuation of RésEAU‘s learning journey will further explore experiences with groundwater quality management.

Sustainable use of groundwater relies on good governance which implies groundwater management decisions are made involving different stakeholders in structured processes, on how to use groundwater resources appropriately, across geographical and organizational scales (Villholth and Conti, 2018).

Yet in many regions, groundwater extraction remains poorly governed — often reactively driven by surface water shortages rather than guided by long-term resource strategies. This unplanned use of groundwater and the fragmented institutions around it, overlook the complex interdependencies between groundwater and surface water systems. Given the hydrological linkages, a conjunctive management approach is essential — treating surface and groundwater as components of a single, integrated resource (see UNESCO, 2020 for guidance on conjunctive water management).

This section draws from recent experiences from the Western Balkans and Central Asia, to explore how unplanned groundwater use can be transformed into informed water management systems at national level. Section 6 will then focus on the governance of transboundary aquifers.

5.1 Integrating groundwater in institutions, laws and basin plans towards conjunctive water management

As source of 77% of drinking water, groundwater in North Macedonia is of high strategic importance. Nevertheless, the resource is not adequately used, managed and protected. The SDC-funded Groundwater Management, Use and Protection Programme (GWP, implemented by Skat Consulting and PointPro Consulting 2022-2027) is working towards strengthening the governance of the country’s water resources (SDC 2024). The project aims to 1) strengthen the competencies of stakeholders for integrated and sustainable groundwater management; 2) support ministries towards a harmonized legal and regulatory framework; and 3) enable better planning and groundwater management in the Vardar River basin.

Efforts to harmonize national water legislation with EU directives are being undertaken — aligning on river basins instead of administrative territories. This measure aims to promote a better coordination among North Macedonian ministries. The Vardar River basin serves as a pilot on conjunctive water management through the establishment of a River Basin Management Plan, supporting an integrated approach to managing surface and groundwater resources. Finally, capacity building is provided to key institutions and stakeholders (public utilities, the private sector and municipalities) in order for them to have the necessary skills and knowledge for sustainable groundwater management (SDC 2024).

5.2 National and basin level institutions for evidence-based groundwater governance

In the Syr Darya river basin in Tajikistan, 90% of available water is used for irrigation. As surface water availability is declining, farmers are turning to groundwater to irrigate. This leads to aquifer depletion, coupled with pollution by fertilizers, pesticides and untreated wastewater. Despite a recent water sector reform program (2015–2025), that introduced Integrated Water Resource Management (IWRM) and basin management principles, groundwater management responsibilities are still scattered among various government entities.

The SDC-funded project on Groundwater Management (GWMP, implemented by Helvetas, 2023-2028) aims to address the institutional fragmentation of water governance through interventions at three levels: aquifer, river basin, and national level.

In two pilot aquifers, hydrogeological studies and improved monitoring systems are supported. This includes digitizing existing groundwater data, building capacities and promoting data sharing among institutions. At basin level, a groundwater technical working group has been established to bring previously scattered information on groundwater and surface water to a common platform to enable conjunctive water management. These local and

basin experiences can then serve as reference for future policy dialogue on groundwater governance at national level, focusing on clarifying roles and responsibilities of groundwater management institutions (Szymanowicz and van der Velden, 2025).

In complement to policymakers, water users are essential partners in shaping effective groundwater governance. They play a critical role in the sustainable use and protection of groundwater. The GWMP fosters user participation by facilitating exchanges between water users and the Tajik Syr Darya River Basin Organisation, to engage them in monitoring, decision-making, and resource management. In addition, basin-level awareness raising campaigns will be held on the threats to groundwater, climate resilience, and the role individuals and institutions play in its sustainable management.

To better meet the demands of the sector in the near future, the GWMP will provide assistance in developing groundwater-related higher and vocational education at regional and national levels, and in strengthening the technical capacity of the drilling sector to adhere to regulatory frameworks and contribute to technical and information challenges the sector faces (Szymanovicz and van der Velden, 2025).

In Kyrgyzstan, the Water Use Permits (WUP KG) project (SDC funded, implemented by the International Office for Water OiEau, 2022-2028) is focusing on regulating water demand, including groundwater. The initiative supports the Ministry of Water Resources, Agriculture and Processing Industry in strengthening the national water use permit system, covering surface and groundwater as well as water pollution (SDC, 2024).

The project aims to promote sustainable use of water resources, through three outcome areas: 1) establishing a national system for water resource accounting and planning; 2) developing a national system for water use permitting and pricing; 3) enhancing knowledge on sustainable water use through data management and stakeholder engagement (SDC, 2024).

River basin management plans will be taken as a starting point for creating an enabling environment for a permit system. The project supports the review and update of a management plan for the Chu River Basin. At sub-basin scale, a local management plan will be developed, incorporating quantitative water-saving targets and actions (SDC, 2024). Given the strong interconnection between surface and groundwater in the pilot basin, monitoring of the interannual groundwater level trends emerges as a key indicator to understand the degree of overuse.

As demonstrated in the project examples above, effective groundwater governance requires simultaneously addressing policy development, data and monitoring systems, and strong user engagement as these are mutually reinforcing.

Groundwater governance in transboundary settings shares many of the same components as national management but adds a layer of complexity. Aligning how data are collected, categorized, and shared, and coordinating water use between countries and users requires trust, transparency, and long-term political and financial commitment.

The growing reliance on groundwater is sparking greater political interest in transboundary cooperation. SDG indicator 6.5.2 measures the proportion of transboundary basin areas (rivers, lakes and aquifers) with an operational arrangement for water cooperation in place. Global reporting in 2023 shows a growing proportion of transboundary aquifer area included under these operational arrangements, yet these are non-aquifer specific arrangements, that is, they cover both surface water and groundwater (UN Water, 2024). Globally, there are only 13 aquifer-specific agreements, of which 8 are operational (Demilecamps, 2025).

Groundwater is often more challenging and costly to manage than surface water, prompting countries to seek support for technical and institutional development. To this end, an UNECE expert group is currently developing guidance on facilitating conjunctive water management at the transboundary level. While progress is evident, showcasing successful cooperation models, addressing data gaps and investing in capacity building are key strategies to encourage broader water cooperation across borders (Demilecamps, 2025).

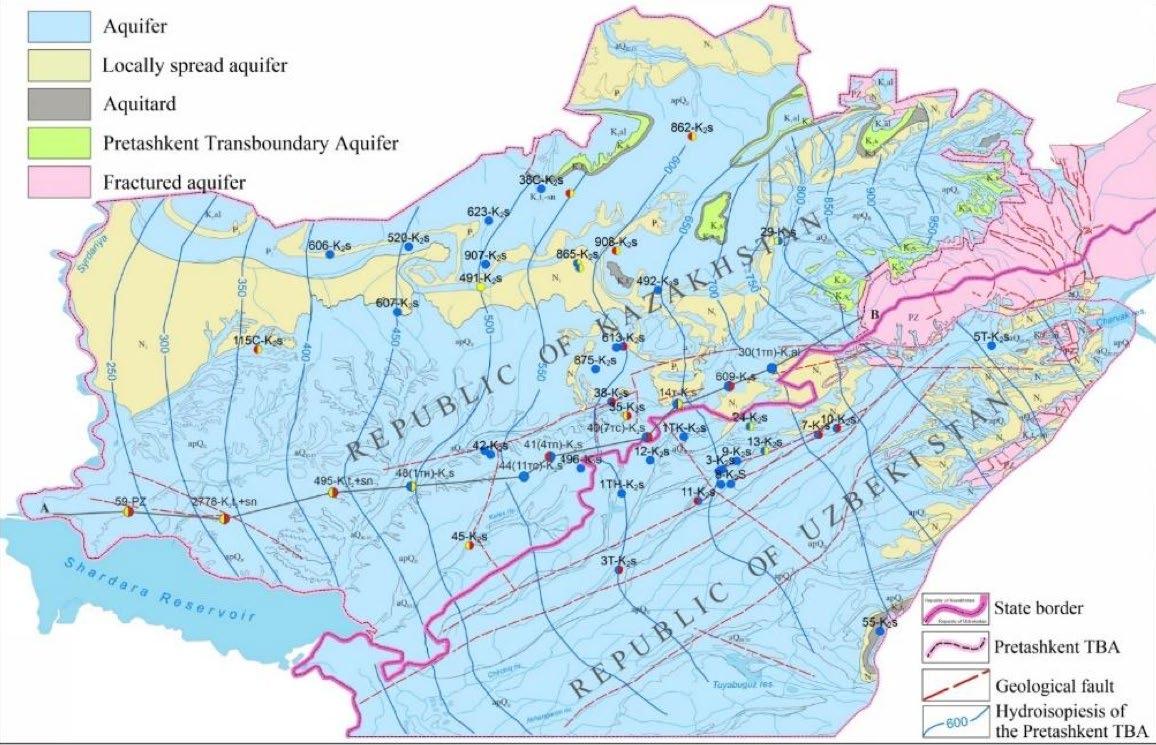

An initiative supported by SDC in Central Asia demonstrates how science-based cooperation can unlock dialogue, build trust, and lay the foundation for transboundary groundwater governance. The Governance of Groundwater Resources in Transboundary Aquifers (GGRETA) project (SDC-funded, implemented by UNESCO-IHP 20152022), focused on the Pretashkent aquifer, a confined and fossil groundwater source shared between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan (Atanov, 2025). The aquifer is vital for economic activities such as health tourism but is overexploited and cannot be naturally recharged. This makes cooperation urgent but politically sensitive.

Against this background, GGRETA’s roadmap for cooperation on the protection and sustainable use of groundwater included improving the legal framework for transboundary cooperation, enhancing monitoring and information exchange, but also strengthening institutions for groundwater governance at the national levels (Atanov, 2025).

GGRETA adopted a science-to-policy approach, mobilizing national research institutes to co-develop a joint hydrogeological model. This model visualized aquifer depletion and helped both countries understand the risks of declining water levels and deteriorating water quality. The project created a platform for scientific exchange of information, enabling the development of transboundary hydrogeological maps and models. Due to legal constraints — such as Soviet-era laws that restrict data sharing— no raw data could be shared across ministries, let alone across national borders. This limitation was overcome by countries sharing processed information and interpretations instead of raw figures.

The project showed that science-policy interfaces can be powerful tools to initiate cooperation, even in politically sensitive contexts.

Groundwater is gaining renewed attention as a high potential yet little-known resource, with growing concerns over depletion and quality deterioration at certain hotspots. Experiences from recent projects show emerging ambitions and directions of change for sustainable groundwater management.

Accurate groundwater data is fundamental for sustainable management, yet monitoring remains limited, particularly in developing countries. Groundwater is a slow but dynamic system, requiring continuous observation and long-term investment in data collection and monitoring Many initiatives began with scarce data and improved over time, but accelerating changes in water levels, withdrawals, and quality now demand robust monitoring to determine aquifer capacity and safe extraction rates. Innovative, cost-effective solutions in data-poor contexts include remote sensing combined with existing water point data and mobile applications for geo-referencing wells and on-site data collection.

Sustainable groundwater use requires defining site-specific abstraction limits and strategies, such as sustainable yield (aligned with long-term recharge) or planned short-term depletion, supported by monitoring and compliance. Policies like water fees and smart metering show mixed results, underscoring the complexity of user behaviour. Solar-powered irrigation offers economic and

environmental benefits but risks uncontrolled pumping unless managed collectively. Groundwater declines can be stabilized through combined measures: demand management, alternative water supplies, and managed aquifer recharge (MAR). Enhancing recharge through naturebased and engineered solutions is critical, alongside robust data systems and watershed management. Groundwater pollution — both geogenic and anthropogenic — threatens usability. Prevention through regulation and land-use controls is essential, as restoration is costly and long-term.

The projects highlighted in this brief demonstrate growing efforts to strengthen groundwater governance worldwide. Most are in early stages, focused on mapping, planning, and monitoring as foundations for future action. However, good governance requires inclusive, structured decision-making across scales and integrated management of surface and groundwater. Core elements include robust data systems, capacity building, institutional strengthening, basin planning, and stakeholder engagement. Governing transboundary aquifers adds complexity, demanding trust, transparent information sharing, and science-policy cooperation.

These steps are essential to address the real impacts of poor management — overexploitation, underuse, and pollution — and to secure groundwater as a sustainable resource for future generations.

Antiporta, Javier (2025)

Alam, M. F.; Varshney, D.; Mitra, A.; Pavelic, P.; Mahapatra, S.; Habib, A.; Krishnan, S.; Sikka, A.; Ravindranath, D. (2025) Does solar irrigation threaten groundwater sustainability? Evidence from India and Bangladesh. Colombo, Sri Lanka: International Water Management Institute (IWMI). 6p.

Building capacity for monitoring and evaluating groundwater data in Peru–El Agua Nos Une project - Peru case. Presentation held for the webinar on Groundwater Data and Monitoring of the RésEAU Learning Journey on Groundwater. May 12th, 2025.

Atanov, Serikzhan (2025)

Governance of Groundwater Resources in Transboundary Aquifers (TBA). Case study: Pretashkent Transboundary Aquifer between Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan (Central Asia). Presentation held for the webinar on Transboundary Groundwater Management of the RésEAU Learning Journey on Groundwater. June 12th, 2025.

Bünzli, Marc André (2025)

Rapid groundwater potential mapping in data-scarce regolithic landscapes: a contribution to hydrogeology in humanitarian contexts. Presentation held for the webinar on Groundwater Data and Monitoring of the RésEAU Learning Journey on Groundwater. May 12th, 2025.

Demilecamps, Chantal (2025)

Global trends in transboundary groundwater management. Presentation held for the webinar on Transboundary Groundwater Management of the RésEAU Learning Journey on Groundwater. June 12th, 2025.

Jasechko, Scott, Hansjörg Seybold, Debra Perrone, Ying Fan, Mohammad Shamsudduha, Richard Taylor, Othman Fallatah & James W. Kirchner (2024)

Rapid groundwater decline and some cases of recovery in aquifers globally. Nature Vol 625. 25 January 2024.

Lictevout, Elizabeth (2025)

Groundwater data and monitoring: A global overview. Presentation held for the webinar on Groundwater Data and Monitoring of the RésEAU Learning Journey on Groundwater. May 12th 2025.

Marti, Beatrice and Tobias Siegfried (2025)

Groundwater & Surface Water Interactions in Central Asia. Presentation held for the webinar on Governance and conjunctive management of surface and groundwater of the RésEAU Learning Journey on Groundwater. March 6th, 2025.

Rodella, Aude-Sophie, Esha Zaveri, and François Bertone (2023) The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Economics of Groundwater in Times of Climate Change. World Bank, Washington, DC.

Szymanovicz, Marian, van der Velden, Thijs (2025)

Groundwater Management Project in the Tajik Syr Darya River Basin -Approaches to Groundwater Governance and Conjunctive Water Management. Presentation held for the webinar on Governance and Conjunctive management of surface and groundwater of the RésEAU Learning Journey on Groundwater. March 6th, 2025.

UNESCO (2020)

Conjunctive water management: a powerful contribution to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. UNESCO, Paris.

United Nations (2022)

The United Nations World Water Development Report 2022 – Groundwater: Making the invisible visible. UNESCO, Paris.

Villholth, Karen (2024)

Global Groundwater Challenges and Solutions. Presentation held for the online launch event of the RésEAU Learning Journey on Groundwater. November 21st, 2024.

Wang, Haijing (2025)

A path towards sustainable use of an over-pumped aquifer: Examples in the Heihe River Basin and the North China Plain. Presentation held for the webinar on Governance and conjunctive management of surface and groundwater of the RésEAU Learning Journey on Groundwater. March 6th, 2025.

World Bank (2023)

What the Future Has in Store: A New Paradigm for Water Storage. World Bank, Washington, DC. 2023.

The Global Groundwater Information System managed by IGRAC: an interactive portal for sharing data and information on groundwater resources around the world. It gives access to map layers, documents, and well and monitoring data. It also contains several thematic map viewers, e.g. on transboundary aquifers, monitoring sites and MAR practices.

The Groundwater Assessment Platform managed by Eawag: Testing groundwater for contaminants like arsenic or fluoride is costly and time-consuming. The GAP hosts prediction maps using machine learning and geospatial data (e.g., geology, soil, climate) which can help target drinking water surveys.

Imprint

Editor:

Federal Department of Foreign Affairs FDFA, Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation SDC 3003 Zollikofen www.sdc.admin.ch

Specialist contact: Section Water E-mail: water@eda.admin.ch

Visuals and infographics: Zoï Environment Network 2025 / © SDC

Cover photo: Groundwater is extracted through a solar-powered tubewell in the district of Rahim Yar Khan, Punjab province, Pakistan © Amjad Jamal/IWMI