Proceedings Journal from the 6th Annual International Conference of the Yale European Studies Graduate Students at Yale University on May 6–7, 2025

26

40

66

PARTICIPANTS PARTICIPANTS

PANEL I: ECHOES OF WAR: EXAMINING THE IMPACTS OF VIOLENT CONFLICTS IN EURASIA

PANEL I: ECHOES OF WAR: EXAMINING THE IMPACTS OF VIOLENT CONFLICTS IN EURASIA

PANEL II: ANTI(IMPERIALIZING) MODERNITY IN LATE IMPERIAL RUSSIA

PANEL II: ANTI(IMPERIALIZING) MODERNITY IN LATE IMPERIAL RUSSIA

PANEL III: IDENTITY POLITICS AND CULTURAL CO-OPTATION IN PUTIN’S RUSSIA

PANEL III: IDENTITY POLITICS AND CULTURAL CO-OPTATION IN PUTIN’S RUSSIA

PANEL IV: SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

PANEL IV: SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

PANEL V: IDENTITY AND RESISTANCE

PANEL V: IDENTITY AND RESISTANCE

PANEL VI: MATERIAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND THE BUILDING OF SOCIALISM

PANEL VI: MATERIAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND THE BUILDING OF SOCIALISM

C O N T E N T S C O N T E N T S T A B L E O F

PANEL VII: EUROPE’S ECONOMIC POLICY, TRADE, AND COMPETITIVENESS IN A CHANGING GLOBAL LANDSCAPE

PANEL VII: EUROPE’S ECONOMIC POLICY, TRADE, AND COMPETITIVENESS IN A CHANGING GLOBAL LANDSCAPE

PANEL VIII: VARIED DIMENSIONS OF LEADERSHIP: CHALLENGES ON THE GLOBAL AND LOCAL STAGES

PANEL VIII: VARIED DIMENSIONS OF LEADERSHIP: CHALLENGES ON THE GLOBAL AND LOCAL STAGES

PANEL IX: REGIONAL AND GLOBAL IMPLICATIONS OF RUSSIA’S INVASION OF UKRAINE

PANEL IX: REGIONAL AND GLOBAL IMPLICATIONS OF RUSSIA’S INVASION OF UKRAINE

PANEL X: INVISIBLE NATION: THE UNTOLD STORIES OF BELARUSIAN CULTURAL EXPRESSION

PANEL X: INVISIBLE NATION: THE UNTOLD STORIES OF BELARUSIAN CULTURAL EXPRESSION

&

Youngresearchersfromaroundtheworldgatheredforthe6thannualEuropeanandEurasianStudies bringingearlycareerscholarstosharetheirresearchandengageindialogueaboutthelivedrealities, histories,societies,andpoliticsofEuropeandEurasia.Theconferenceorganizingcommitteeis primarilycomposedoftheMacMillanCenter’sEuropeanandRussianMAstudents,aimingtofoster greaterexchangeofideaswithinYaleandbeyond,whilealsoenhancinginterinstitutionalconnections withotheruniversitiesintheUSandabroad.Theconferencewastheresultofayear-longjointeffort thatbroughttogether37studentsandresearchersfrom17universities.Overthecourseofthetwo days,10panelsexploredawiderangeoftopics,includingthedestructiveimpactsofviolentconflictin Eurasia,imperialhistories,nationalidentityandwartimepoliticsinPutin’sRussia,theEuropean Union’seconomicpolicy,socialtransformationintheSouthCaucasus,globalandlocalchallengesof leadership,Belarusianculture,andtheregionalandglobalimplicationsofRussia’sinvasionofUkraine.

ThisyearcelebratedtheseventhanniversaryoftheEuropeanStudiesstudentaffiliatesnetworkatYale University,aneffortthathasfosteredagrowingcommunityofjuniorresearchersacrosstheinstitution andnowincludesover100students.WehopethisrecentconferencewillstimulatefutureinterdisciplinarycooperationandcooperativeresearchendeavorsonmodernEuropeandEurasia.We appreciatetheparticipationofallpresenters.Wewouldliketoespeciallyextendourgratitudetothe facultydiscussantsandadvancedresearchersfromYaleandsixacademicinstitutionsforgenerously dedicatingtheirtimetodriveconversationofthesesignificantyetchallengingtopics.

Withsincereappreciationtoalltheparticipantsoftheconferencefromthemembersofthethe PlanningCommittee:

CommitteeChair:VitaRaskeviciute,YaleUniversity

TanyaKotelnykova,YaleUniversity

JacobLink,YaleUniversity

DashaMaliauskaya,YaleUniversity

OliverWolyniec,YaleUniversity

LolaShehu,YaleUniversity

LydiaSmith,YaleUniversity

MikeYork,YaleUniversity

ChristinaAndriotis,YaleUniversity

ManagementandstudentsupportoftheESC

l h o u s e A v e .

8:45 AM

9:30 AM

9:40 AM

Breakfast | Luce Hall, Common Room

Welcome Remarks | Luce Hall, Room 203

PANEL I: Echoes of War: Examining the Impacts of Violent Conflict in Eurasia

Chair: Oliver Wolyniec (Yale University)

Discussant: Prof David Simon (Yale University)

Rowan Baker (Yale University), “Being Homeland: Indigeneity, Power, Decolonization, and Peacebuilding between Georgia and Abkhazia”

10:50 AM

Alice Mee (Columbia University), “The Enemy Within? Collaboration and the Boundaries of National Identity in Wartime Ukraine”

PANEL II: Anti(Imperializing) Modernity in Late Imperial Russia

Chair: Vita Raskeviciute (Yale University)

Discussant: Prof. Sergei Antonov (Yale University)

Mariana Kellis (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign), “Conceptions of Freedom in Serf Memoirs: Imagining Emancipation Before the End of Serfdom”

Roman Osharov (University of Oxford), “Policing and Ethnography in Asian and Russian Tashkent, 1890-1897”

Vita Raskeviciute (Yale University), “Between Nation(s) and Empire(s):

12:05 PM

1:05 PM

Polyethnic Borderland Patriotism in Post-1905 Vil’na Guberniya”

Lunch Break | Luce Hall, Common Room

PANEL III: Identity Politics and Cultural Co-optation in Putin’s Russia

Chair: Dasha Maliauskaya (Yale University)

Discussant: Prof. Peter Rutland (Wesleyan University)

Diana Avdeeva (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign), “Decolonizing Russian Identity: Examining the Role of Non-Russian Ethnic Groups in Putin’s Russia”

Kristofers Krumins (Georgetown University), “Russia’s War Bloggers and the Prospect of Peace: an Assessment of the Perceptions of Ceasefire in Ukraine”

2:45 PM

Adriane Longhurst (Georgetown University), “Russia’s Affinity for Immortality” Anonymous (Indiana University), “From Lament to Loyalty: The Co-optation of Chuvash Recruit Songs in Russian Pro-War Propaganda”

PANEL IV: Social Transformation in the South Caucasus

Chair: Lydia Smith (Yale University) | Discussant: Prof Julie A. George (CUNY)

Salome Mamuladze (Georgetown University), “Managing Displacement: A Policy Analysis of Georgia’s IDP Crisis”

Lori Pirinjian (University of California, Los Angeles), “The Domestic Violence Law of Armenia (2018-2020): A New Era in the Legislation”

Eliška Vinklerová (Oxford University), “Rave Against the Machine: Club

4:00 PM

4:30 PM

Cultures and Queer Activism in Georgia”

Break

PANEL V: Identity and Resistance

Chair & Discussant: Lola Shehu (Yale University)

William Sims (European University Institute), “‘A Page of Italian History ’ The March on Rome told through the Coverage of Local, National, and Diaspora Italian Liberal Newspapers”

Filippos Toskas (Oxford University), “Exploring key political concepts through 1970s queer press: redefining political liberation and Marxism” Yuni Zeng (University of Amsterdam), “Decolonizing Czech Music: Má vlast & the Struggle for Cultural Autonomy from Habsburg Rule to Soviet Influence" H E N R Y R . L U C E H A L L R m 2 0 3 ( 2 n d f l ) | 3 4 H i

8:30 AM Breakfast | Luce Hall, Common Room

9:00 AM PANEL VI: Material Infrastructure and the Building of Socialism

Chair: Jacob Link (Yale University)

Discussant: Dr Nataliia Laas (Yale University)

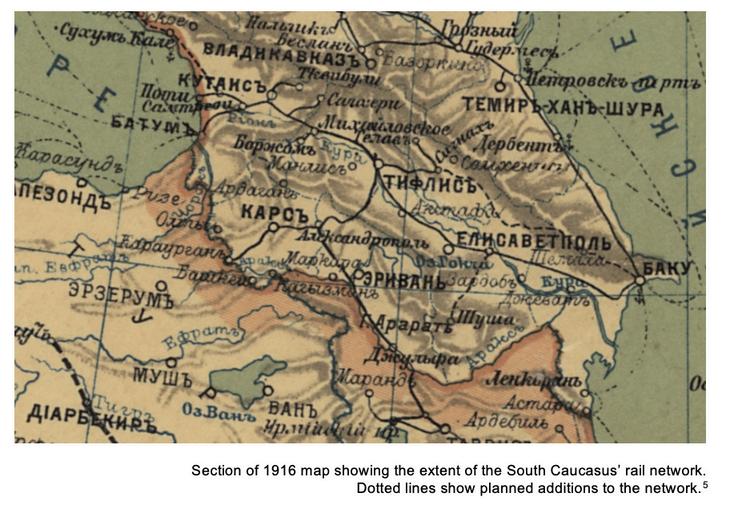

Jacob Link (Yale University), “Red Networks: Technologies of Power in the Red Army’s Conquest of the South Caucasus”

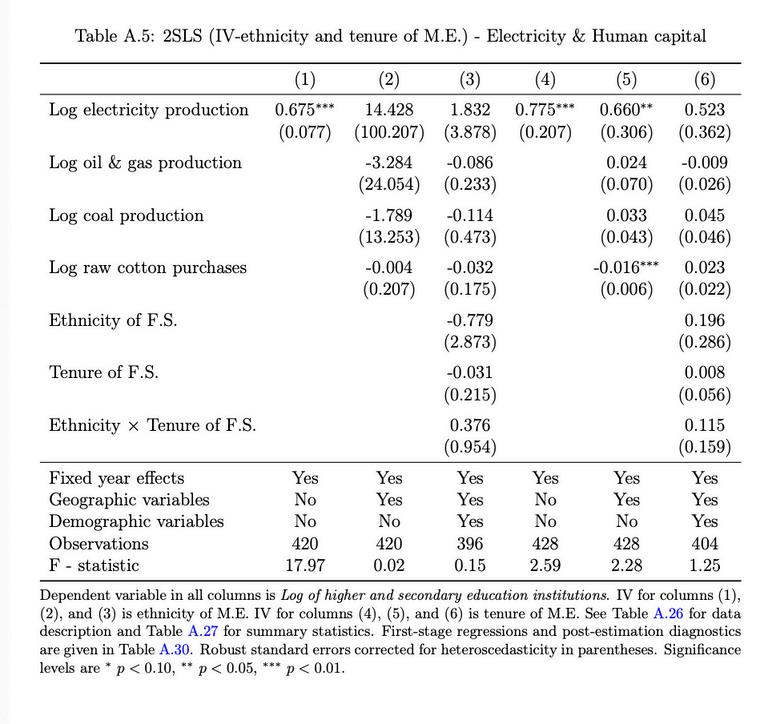

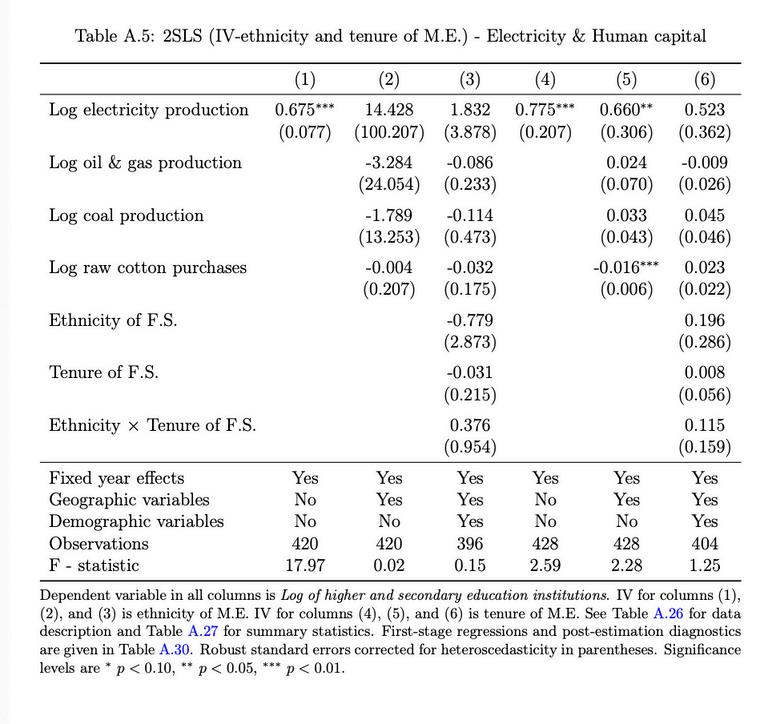

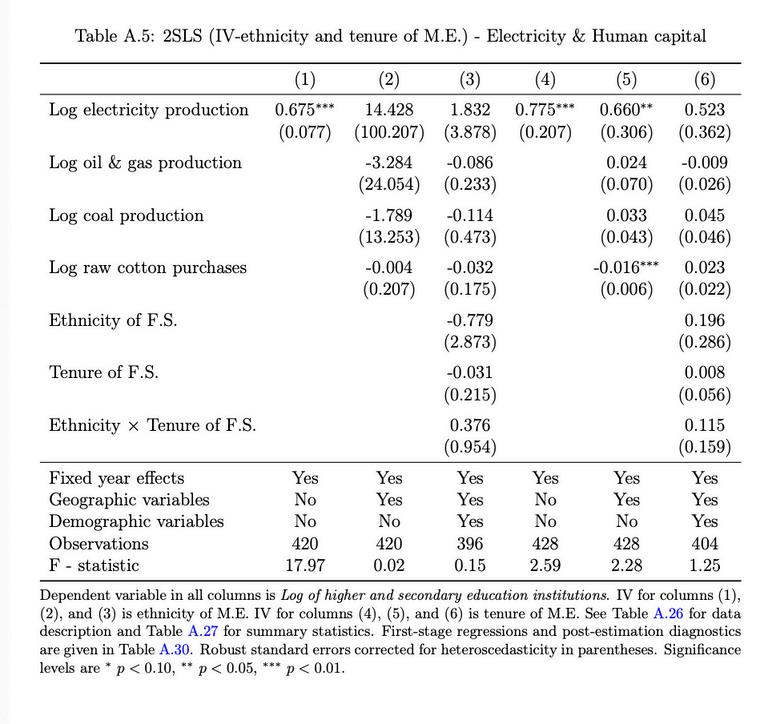

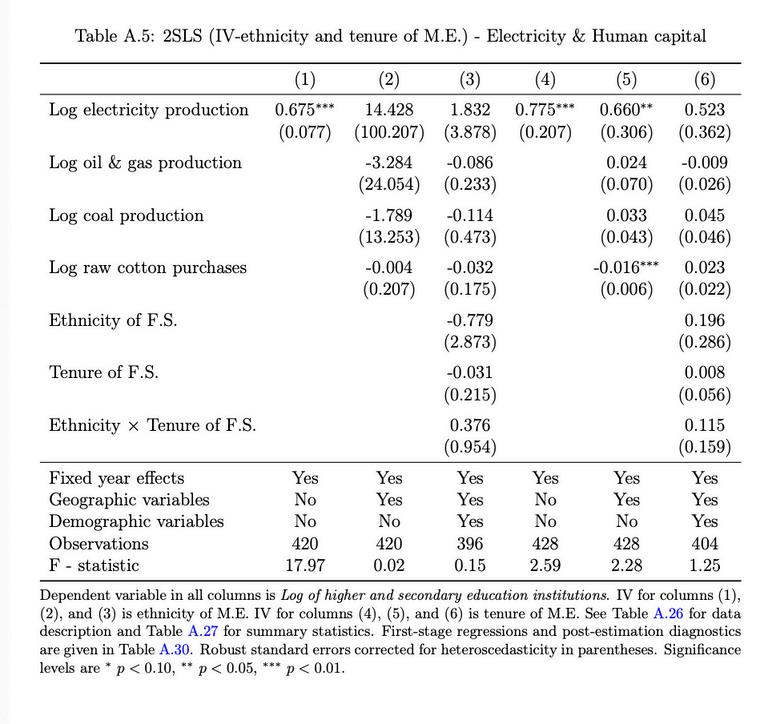

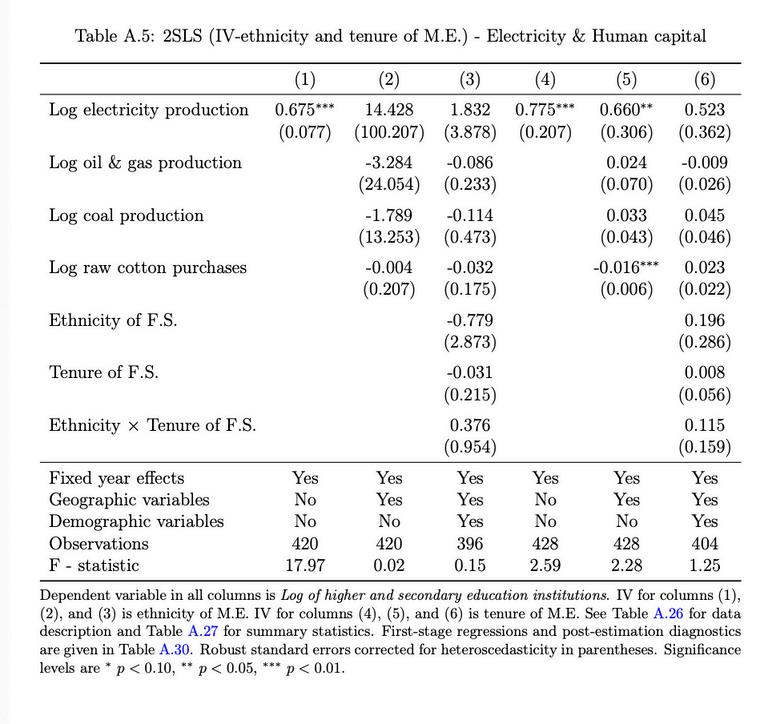

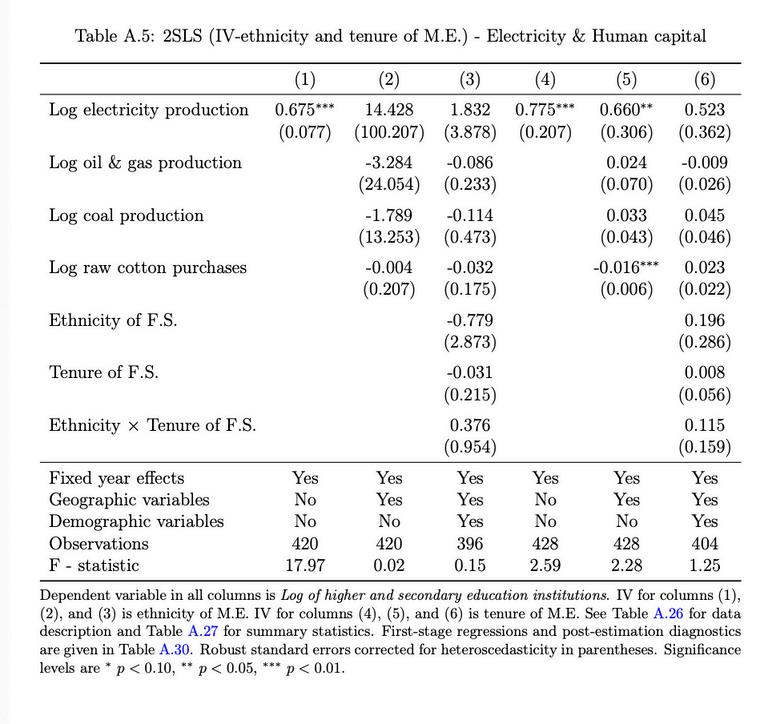

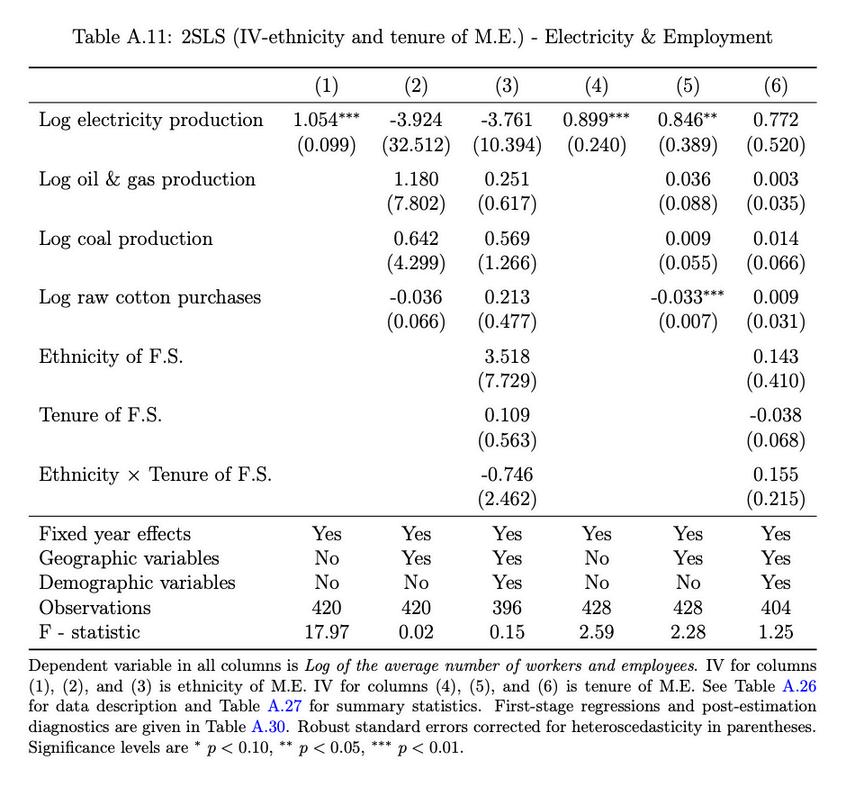

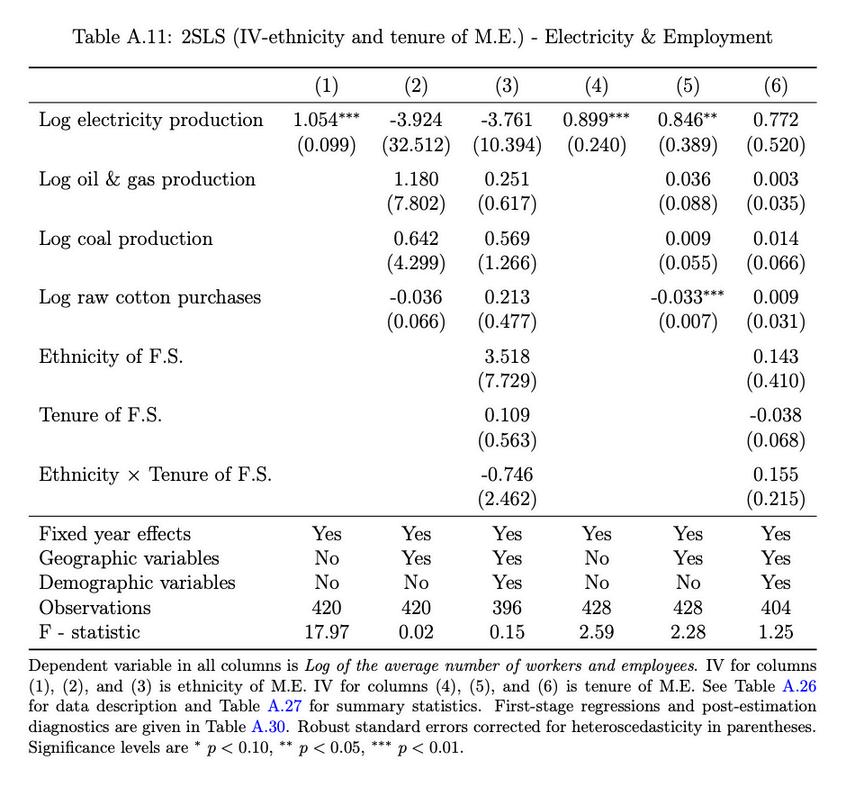

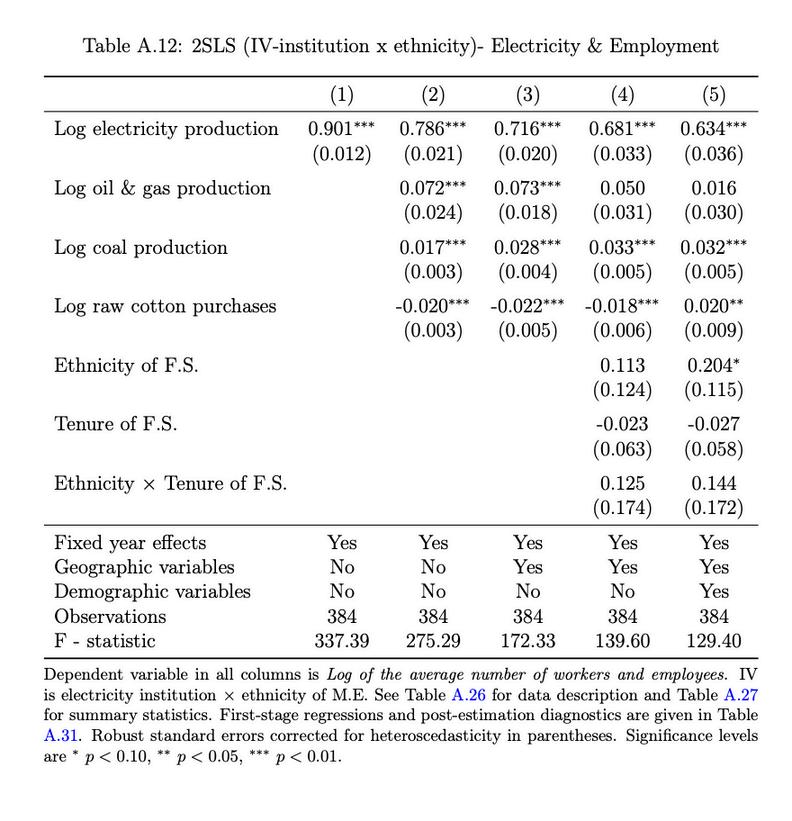

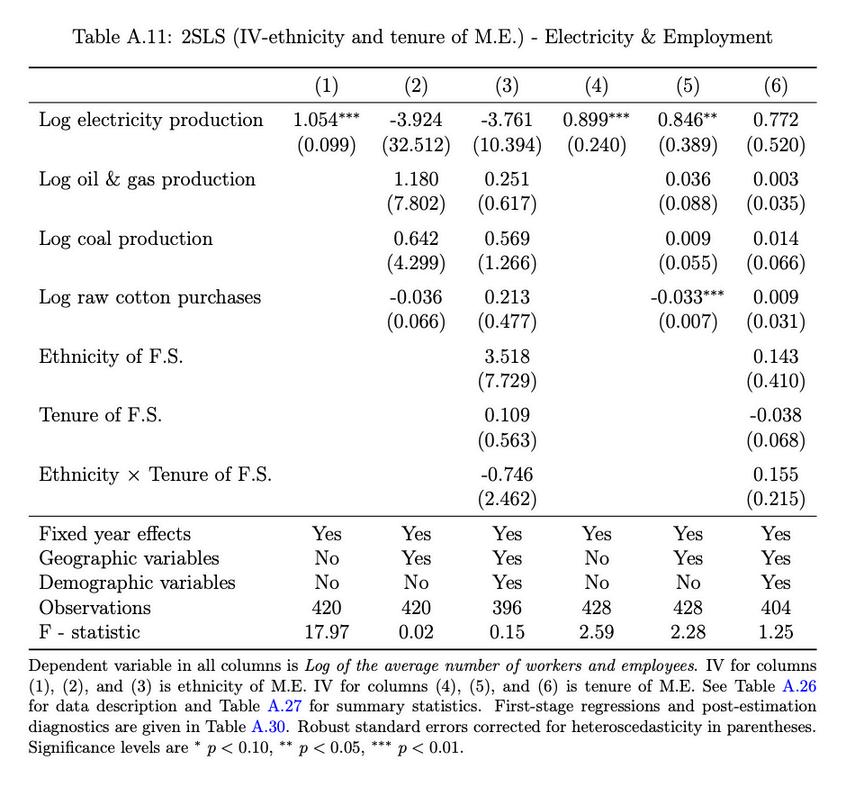

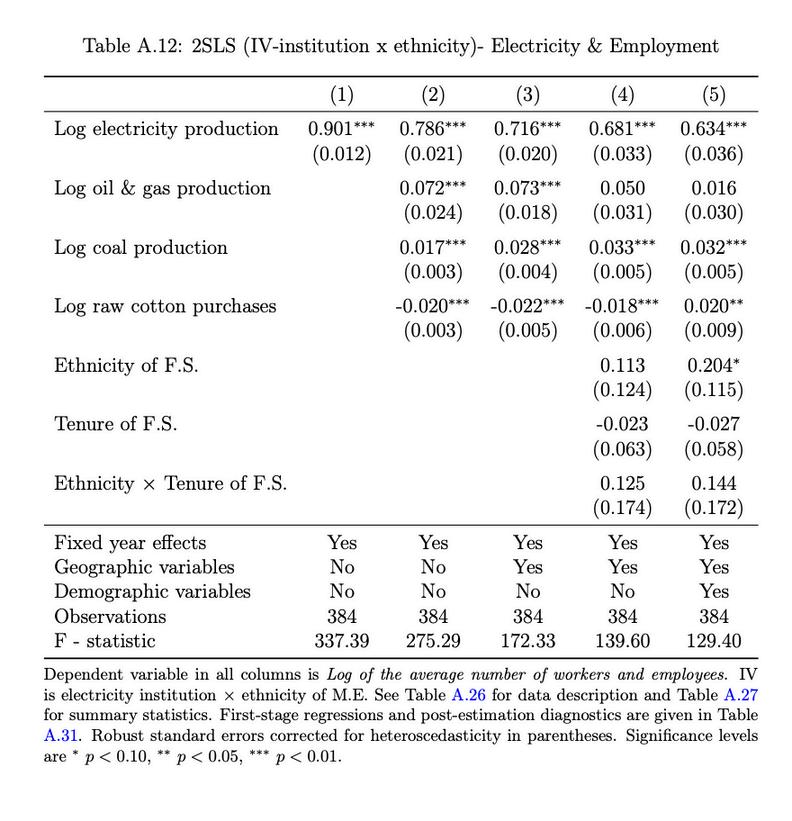

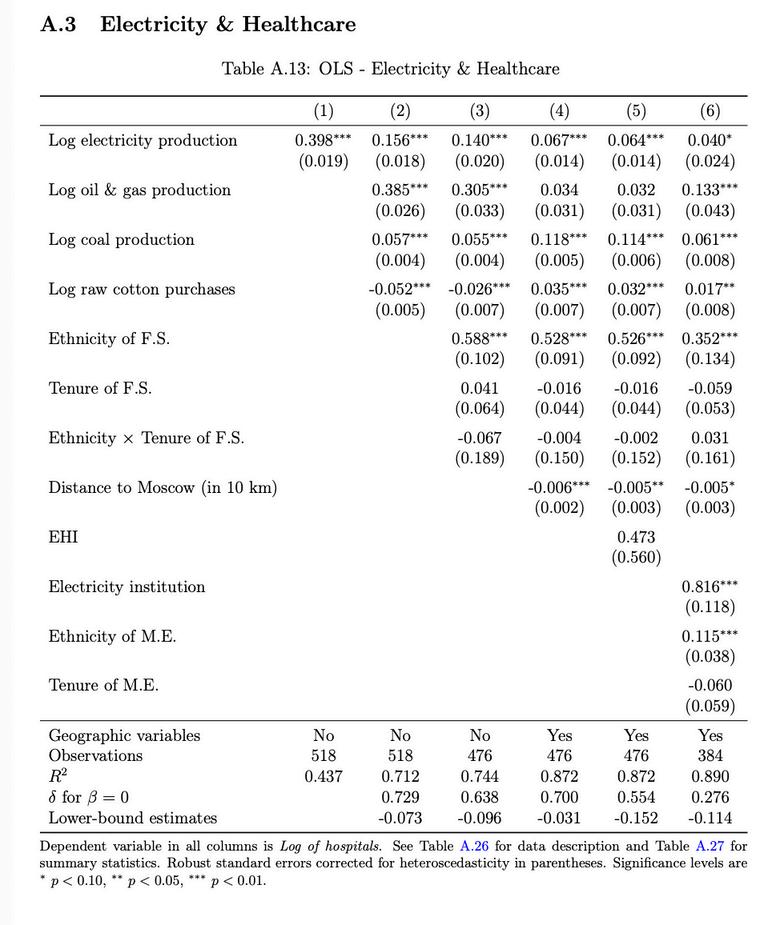

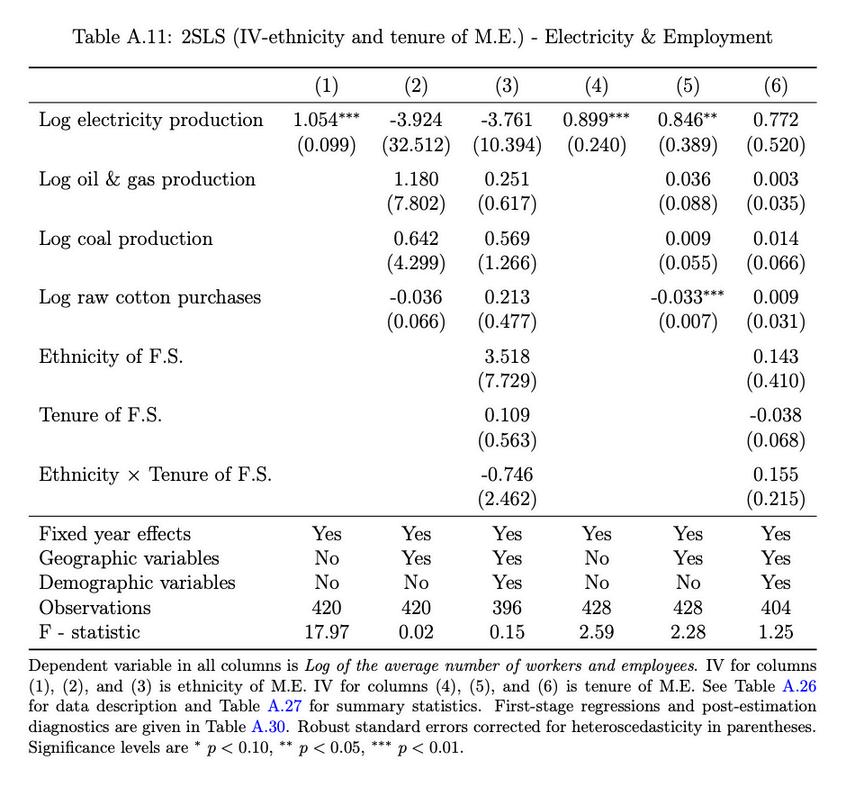

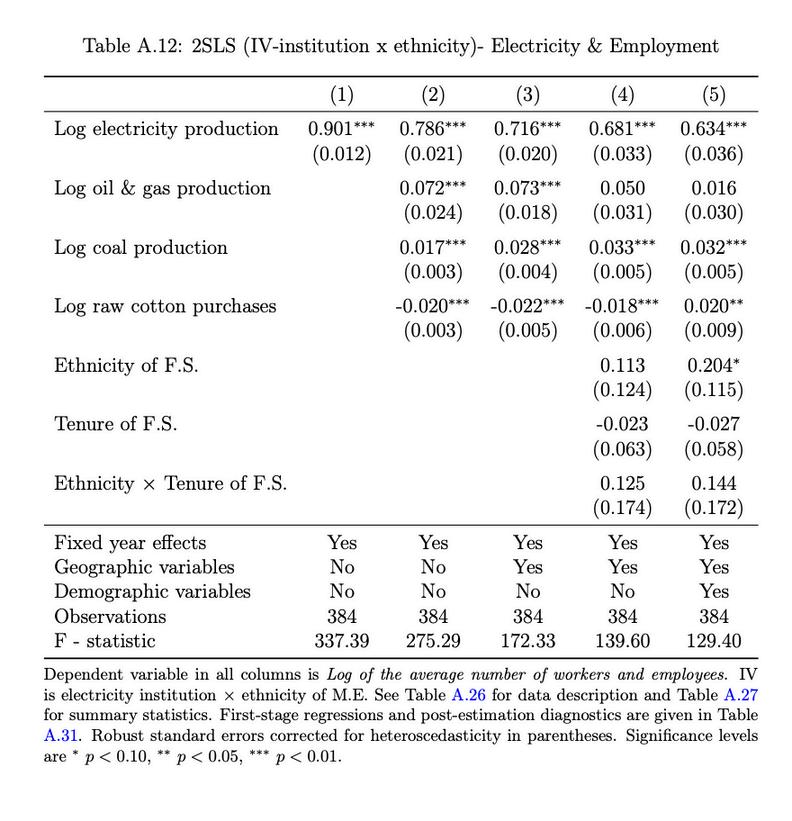

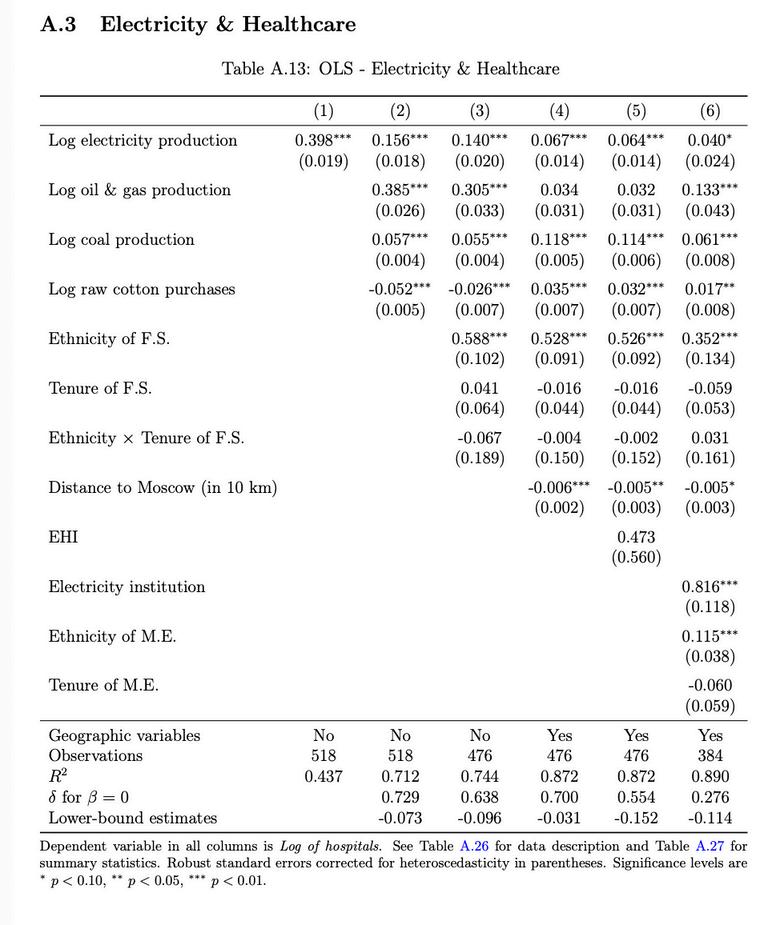

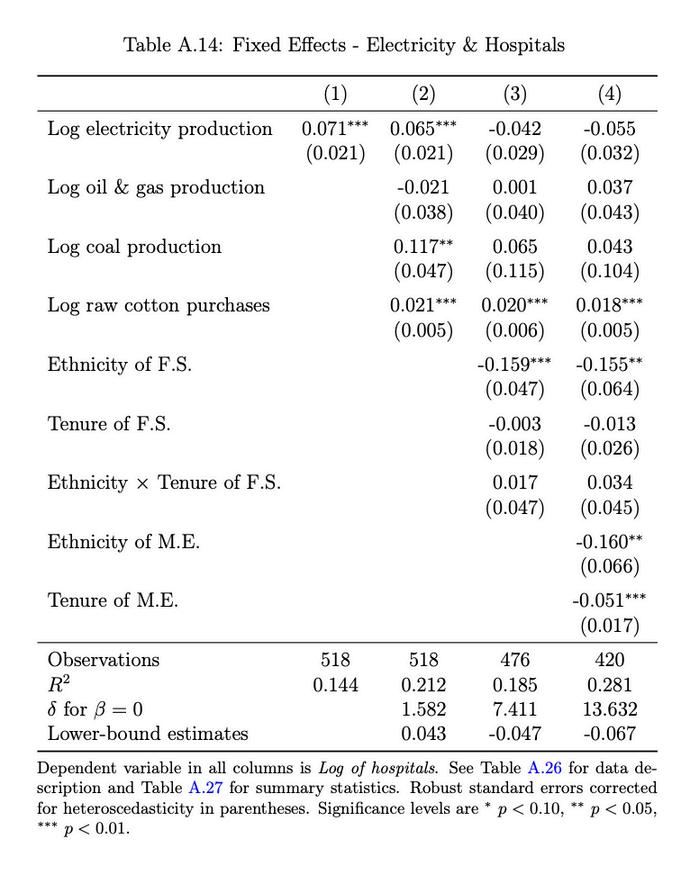

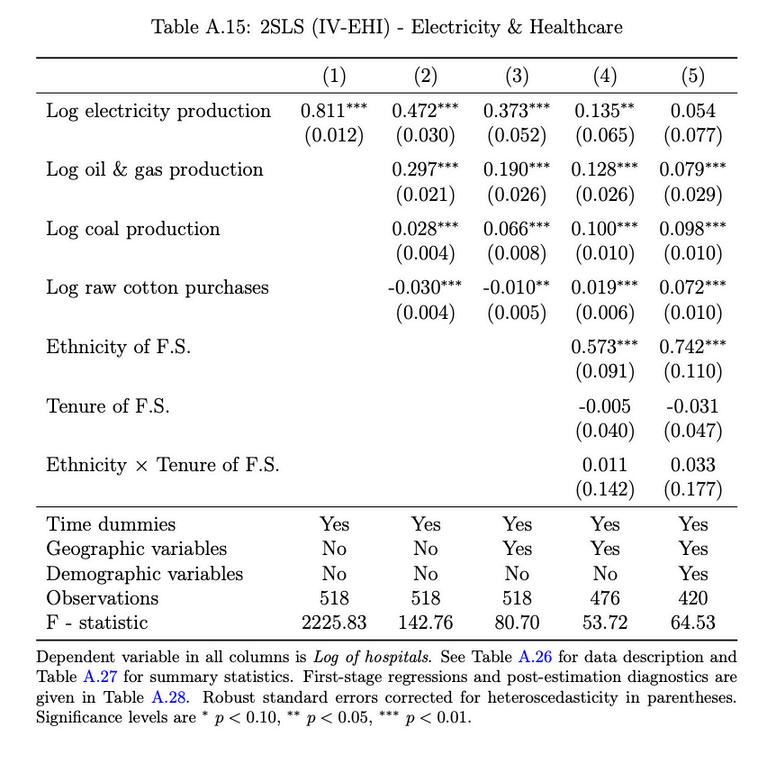

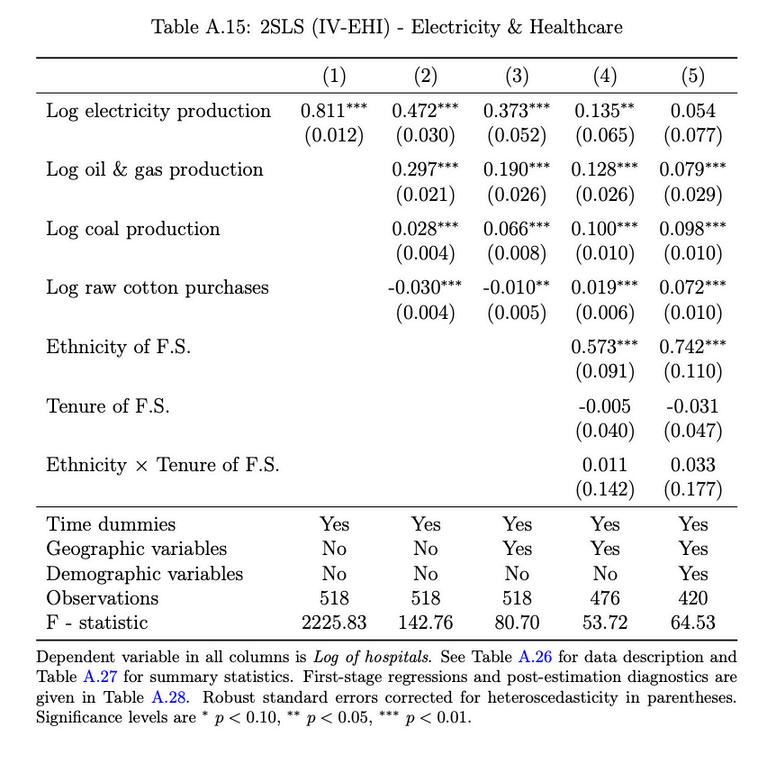

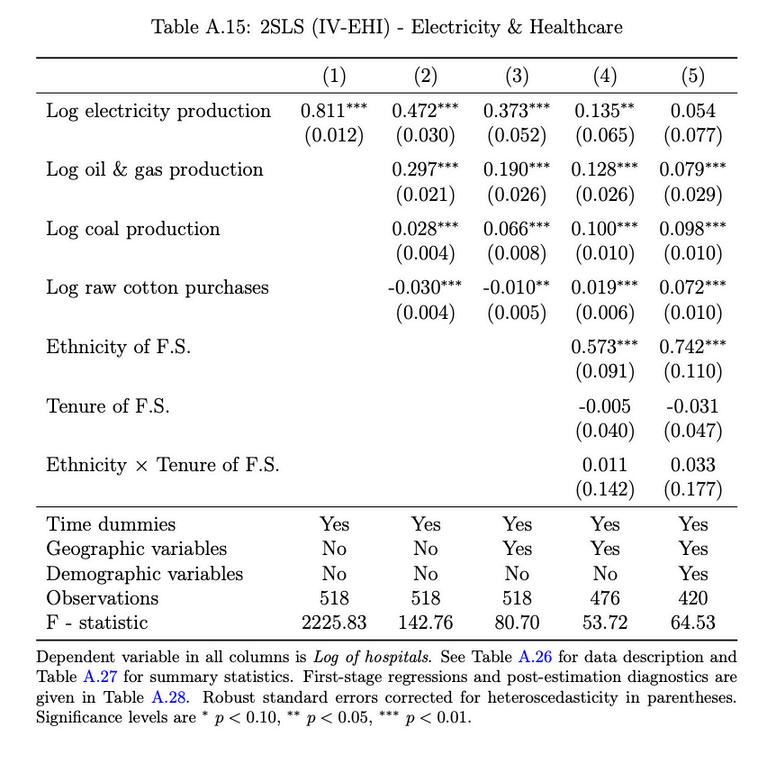

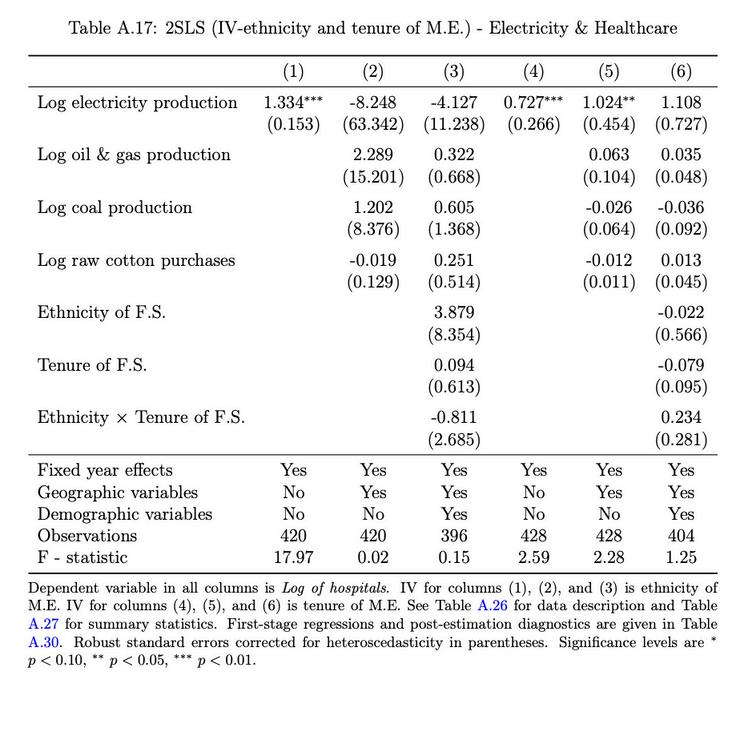

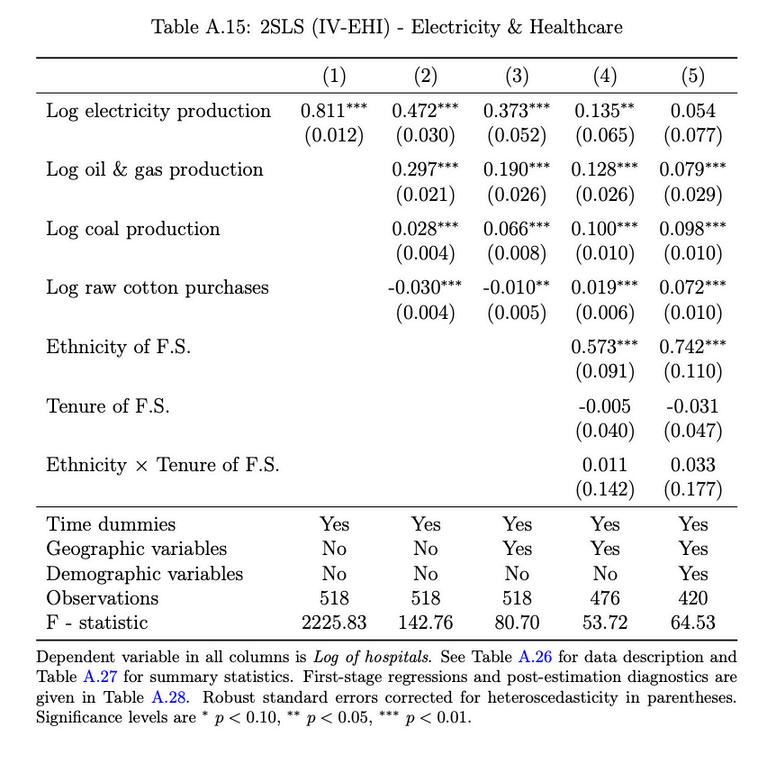

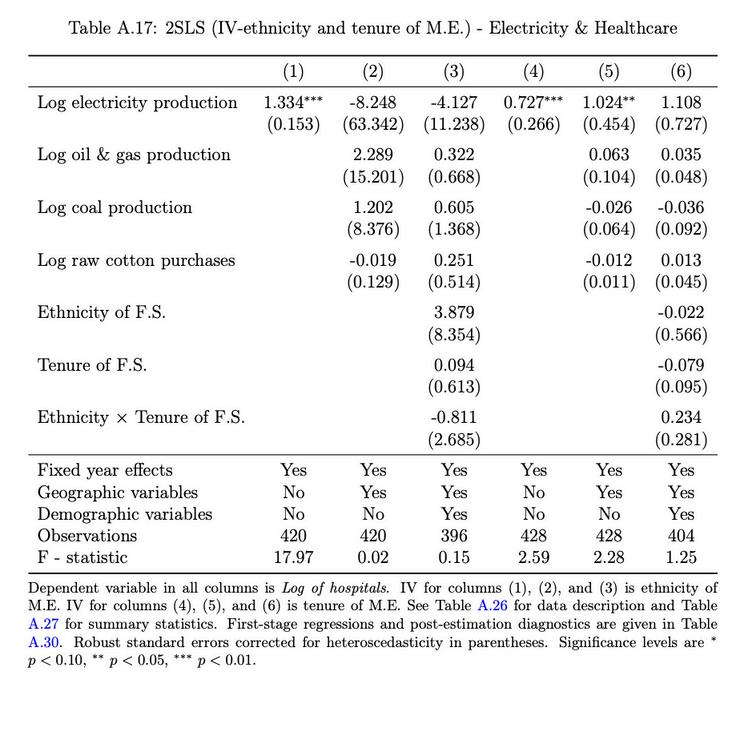

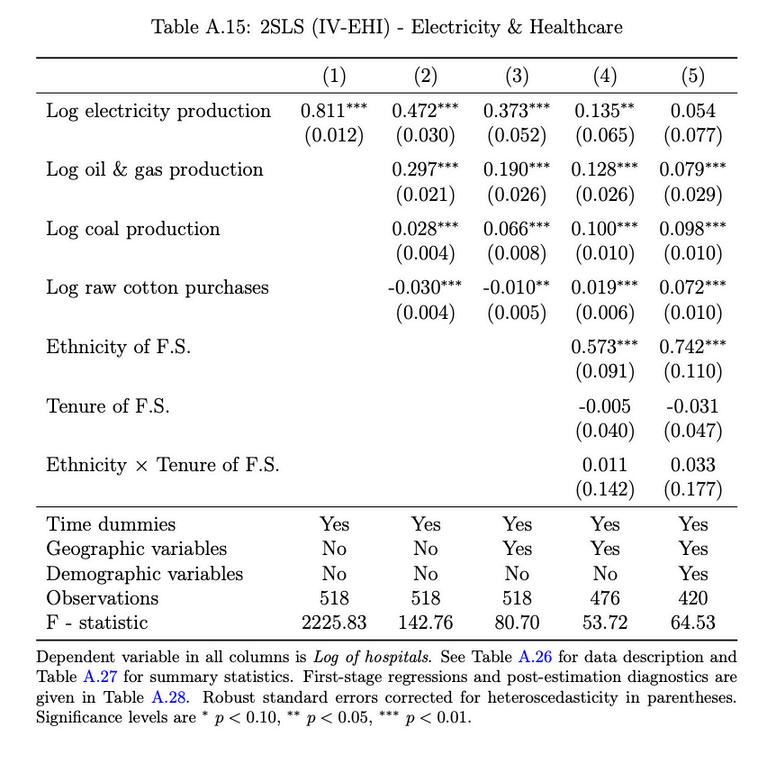

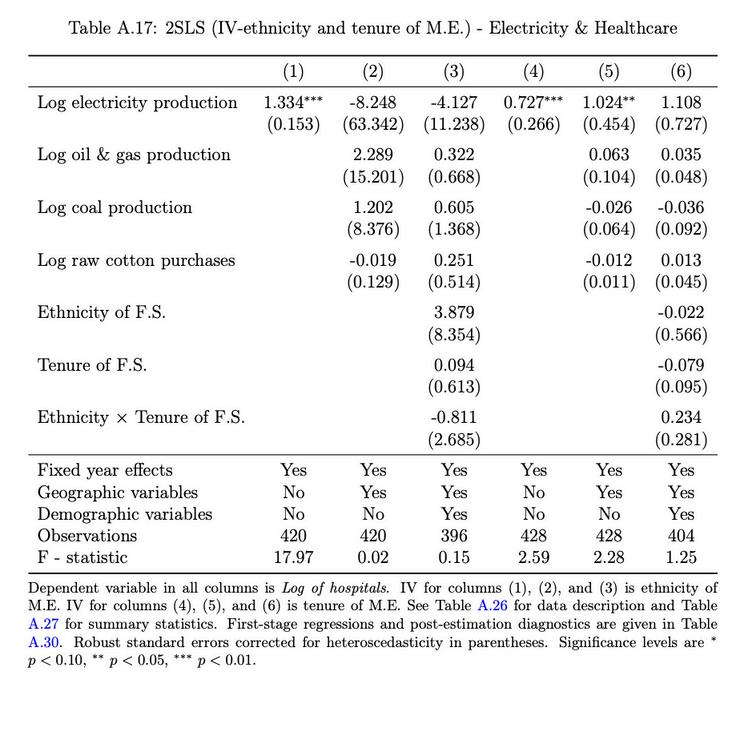

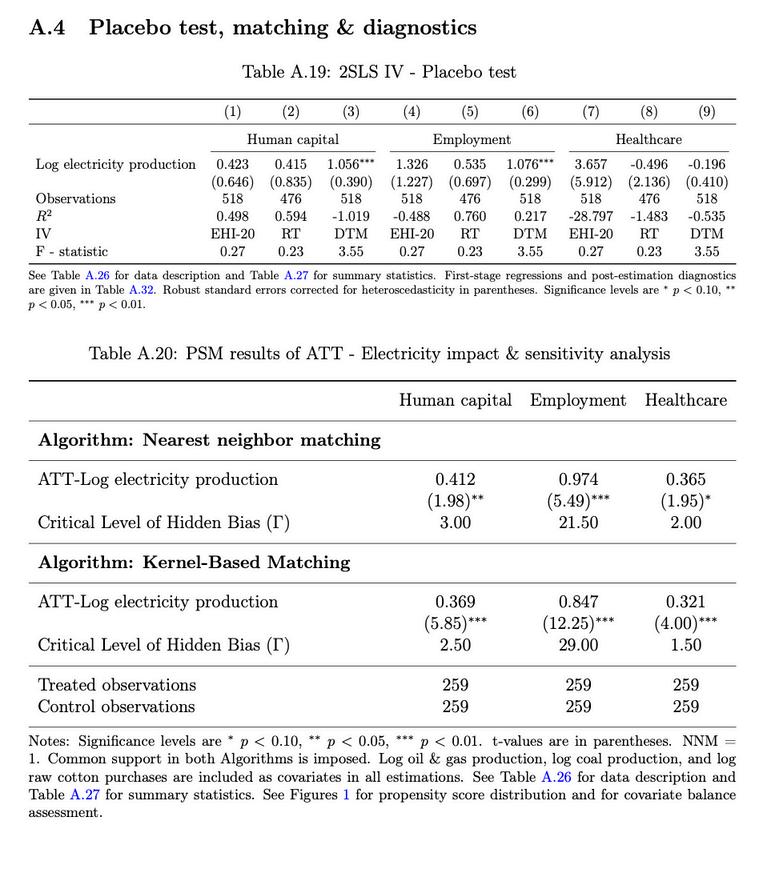

Agzamkhon Niyazkhodjayev (Free University of Berlin), “Electricity & Socioeconomic Performance: Evidence from the Short Soviet Century”

Nicholas Pierce (University of Texas, Austin), ‘Forcing the Gates of the Future’: Dams as Sites of High Modernity in Roosevelt’s United States and Stalin’s Soviet Union” 10:25 AM PANEL VII: Europe’s Economic Policy, Trade, and Competitiveness in a Changing Global Landscape

Moderator: Lili Vessereau (Harvard University)

Carlo Giannone (Harvard University), “EU Trade Policy in the Era of Protectionism: De-risking from US”

Justine Haekens (Harvard University), “How Does Corporate Wealth Translate into Market Power?”

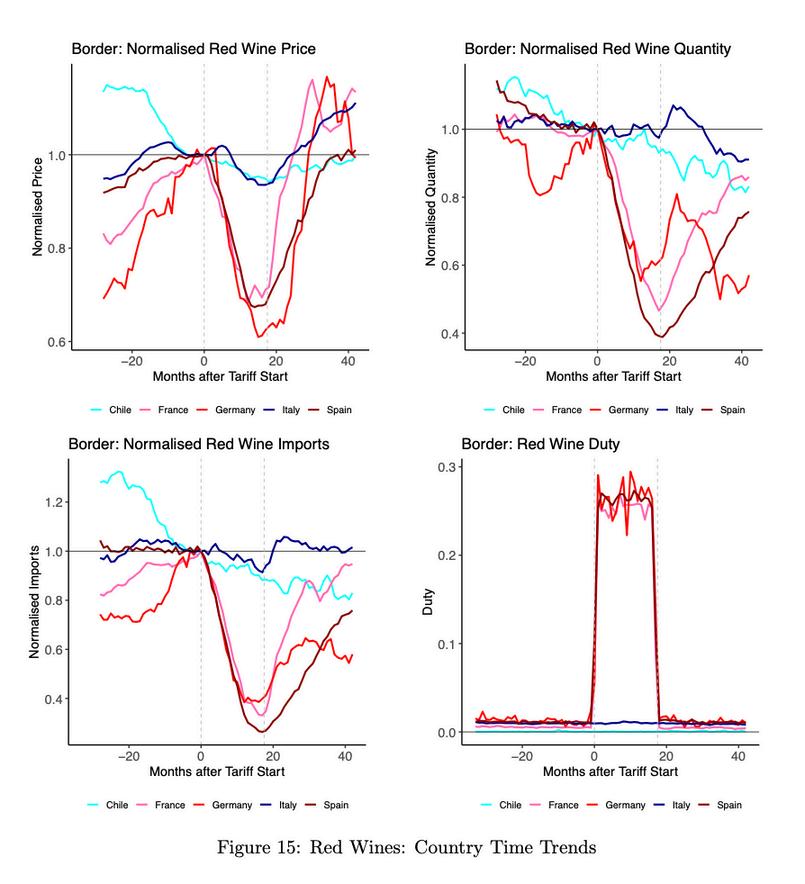

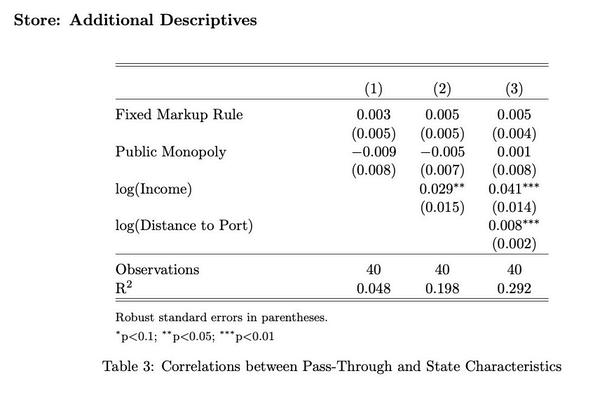

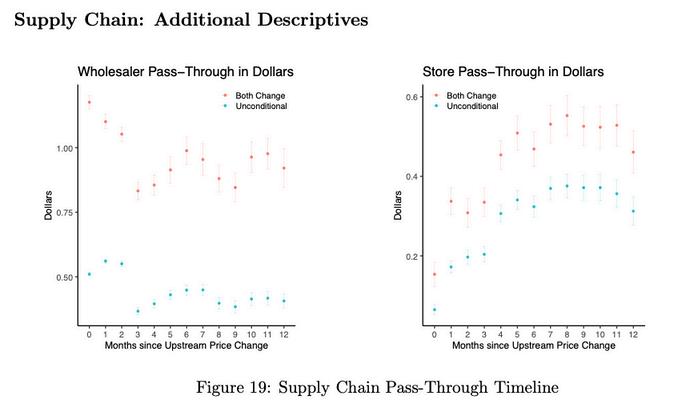

Vanya Klenovskiy (Yale University), “Tariff Pass-Through along the Supply Chain: Evidence from Liquor Industry”

:40

Lunch Break | Luce Hall, Common Room

PANEL VIII: Varied Dimensions of Leadership: Challenges on the Global and Local Stages

Chair: Christina Oh (Yale University)

Discussant: Prof. Jonathan Bach (The New School)

William Hopkinson (University of Melbourne & Yale University), “Climate Hybridity: Norway as both Leader and Laggard”

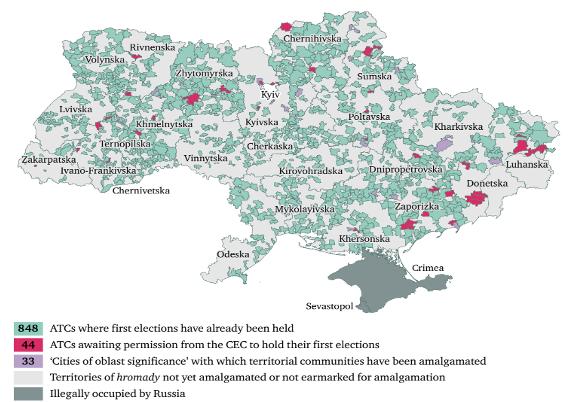

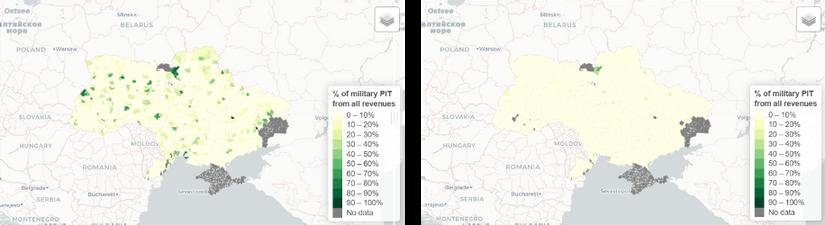

Noah Lloyd (Georgetown University), “The Battle for Local Autonomy: Decentralization Processes in Wartime Ukraine”

Christina Oh (Yale University), “Exporting Repression: Russian Influence Campaigns in Mali and Burkina Faso”

2:05 PM PANEL IX: Regional and Global Implications of Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine

3:30 PM

Chair: Tanya Kotelnykova (Yale University)

Discussant: Prof David Cameron (Yale University)

Valerie Browne (Harvard University), “Accessing National Belonging in Kazakhstan: Russophone Almatyntsy and the Kazakh language learning movment in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine”

Noela Mahmutaj (University of Tirana), “Wartime consequences: The impact of Ukraine war on the Western Balkans”

Łucja Skolankiewicz (University of Oxford), "Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and war in Ukraine. Member States reactions to the Russian invasion"

PANEL X: Invisible Nation: The Untold Stories of Belarusian Cultural Expression

Chair: Mike York (Yale University)

4:30 PM

Discussant: Andrei Kureichyk (University of Chicago)

Maryna Antaniuk-Prouteau (Stanford University), “Language Policy in Belarusian

Cinema: Between Russification and National Revival”

Vesta Svendsen (Brown University), “Transgenerational Trauma and Today’s Belarus”

RECEPTION | Luce Hall, Common Room

4:30 4:30

PresidentVolodymyrZelenskyisdailyspeechestothenationbetween24February2022and23February2024Inthe secondsection,IexaminecourtcasesagainstcollaboratorsinthesameperiodMycourtcaseanalysisisbasedona datasetofoneintenoftheverdictsdeliveredinthistimeframe,equatingto130cases,whichwereselectedateven intervals. Iarguethatnationalbelonginghascometobepredicatedlargelyonunwaveringloyaltytothenation. Moreover, Ihighlightthedetachmentofthenotionofcollaboration cooperationwithenemyforces, arguingthat collaboratorsarepositionedbyUkrainianauthoritiesasanenemyintheirownright. Assuch, Isuggestthatgreater terminologicalnuancemaybeusefultopolicymakers,lawenforcementandthepublicalike.

Oliver Wolyniec is a current M A student in the European and Russian Studies program at Yale He grew up in Minnesota and earned his B.A. in international relations and Russian from Carleton College in 2019. In his junior year, Oliver spent the spring term at Moscow State University on a study abroad program After graduation, he spent several months studying Russian in Nizhny Novgorod through the Critical Language Scholarship (CLS) program before joining the Peace Corps in Montenegro as an English language teacher His time in the Balkans was cut short by the onset of the coronavirus pandemic in March 2020 At Yale, Oliver is focusing on the role of civil society in conflict prevention and peacebuilding efforts in Russia, East Europe, and Eurasia He is especially interested in the ongoing war in Ukraine, the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, and resurgent ethnic nationalism in the Balkans

David J. Simon is the Assistant Dean for Graduate Education as well as a Senior Lecturer in Global Affairs. He also serves as the Director of the Genocide Studies Program at Yale University David’s research focuses on mass atrocity prevention and post-atrocity recovery, with a particular focus on cases of mass atrocity in Africa, including those in Rwanda and Cote d’Ivoire He is co-editor of Mass Violence and Memory in the Digital Age: Memorialization Unmoored (Palgrave-MacMillan, 2020, with Eve M Zucker), and co-editor of the Handbook of Genocide Studies (Edward Elgar, forthcoming, with Leora Kahn). He helped launch the Mass Atrocities in the Digital Era initiative within the Genocide Studies Program (with Nathaniel Raymond) The initiative which recognizes that digital technology has brought about sea changes in all aspects of mass atrocity from the commission of it to the efforts to prevent it to the prospects of holding perpetrators responsible and seeks to bring experts from the fields of genocide studies, international criminal law, and internet data governance in conversation with one another to devise appropriate responses

ROMAN OSHAROV

Roman Osharov is a DPhil Candidate at the University of Oxford’s Faculty of History, where his dissertation examines the Russian Empire's production of knowledge about Central Asia in the nineteenth century, its uses and limits. He began studying the history of the Russian Empire and Central Asia in 2019, building on some of his earlier work done while studying at King’s College London Research for his DPhil has taken him to archives and libraries across Eurasia, including Georgia, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Mongolia, as well as to holdings in the United States and the United Kingdom. During his DPhil Roman has taught on the history of the Russian Empire and Soviet Union course at the Faculty of History and New College, Oxford, and held a teaching fellowship at the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology

"PolicingandEthnographyinAsianandRussianTashkent,1890-1897" ThispaperexaminestheproductionofknowledgeintheserviceoftheRussianimperialpowerbyfocusingontheroleofethnography, andparticularlycensusdata,inTashkentunderRussianrule ItarguesthatethnographywasoneofthekeywaysfortheRussian EmpiretopenetrateCentralAsiancommunities WhentheRussiansfirsttookoverTashkentin1865theydidnotknowhowmany peoplelivedinthecity,andwerefacedwiththeneedtocountthepeopleinthenewlyconqueredregion,inordertoholdelectionsand setupacolonialadministrationYet,reliableinformationonthesizeofthepopulationonlybegantoemergeinthe1890s,whenNil SergeevichLykoshinbecamethefirstRussianpolicechiefandeffectivelyheadoftheAsianpartofTashkentinasweepingpolice reformthatfollowedthe‘cholerariot’ Lykoshin’sappointmentwasanindicatorthattheRussianimperialpowerwasextendingits footprintbytakingoveranareaoflocaladministrationthatsincetheconquesthadbeenleftlargelyinthehandsofCentralAsians

Vita Raskeviciute is currently pursuing an MA in European and Russian Studies at Yale University Born and raised in Lithuania, her interests converge at the crossroads of democratization and the formation of national identity within the post-Soviet landscape Vita obtained her B A in International Relations and Russian and East European Studies from the University of Pennsylvania

"BetweenNation(s)andEmpire(s):PolyethnicBorderlandPatriotisminPost-1905Vil’naGuberniya" TheeraofmasspoliticsandideologicalfermentarrivedinoneofImperialRussia’swesternmostprovincesalmostovernight FollowingTsarNicholasII’sproclamationoftheOctoberManifestoin1905 whichestablishedapopularlyelectedparliament, theDuma,promisedcertaincivilliberties,andeasingofcensorship theethnically,linguistically,andconfessionallydiverse populationofVil’naGuberniyagainedaccess, forthefirsttime, toarelativelyunrestrictedpublicsphereofpolitical organizationandvibrantprintingpressThisnewfoundpoliticalspacepropelledVil’nainhabitantstopubliclynegotiatetheir relationshipwiththeimperialstate,emergingideologies,andtheirneighborsThispaperexaminestheunfoldingoftheDuma electionsinVil’naGovernoratein1905-1912,focusingonhowpoliticalelitesinthisprovinceleveragedimperialreformsand theroomofmaneuvertheyprovidedtoarticulateandpromotecentrifugalpositionalityoftheNorthwesternborderlandwithin theEmpireItarguesthatculturallyPolishelitesinVil’naGovernorateutilizedDumaelectoralcampaignsandpoliticstoassert the distinctiveness and cohesion of the Northwestern provinces of Imperial Russia, constructing a mental map that differentiated these lands from both Congress Poland and the territories deemed primordially Russian (исконно

)

Sergei Antonov specializes in modern Russia after 1800, with particular interest in politics, culture, and society in the late imperial and early Soviet period (ca 1850-1927) His research focuses on the history of Russian law, conceived broadly to include not just legislation and legal doctrines, but ways in which legal norms and institutions impacted the daily practices of ordinary persons, rich and poor, men and women, and served to define and protect private interests, resolve (or perpetuate) interpersonal conflicts, as well as to assert (or challenge) social power and authority

Diana Avdeeva is a graduate student in Slavic Studies at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Originally from Moscow, Russia, her research focuses on Belarus, Ukraine, and Russia, with an emphasis on nationalism and national identity as reflected in artistic production in Russia under Putin Diana's work particularly examines the Russian opposition, the antiwar movement, and the experiences of Russia’s Indigenous peoples. She also explores creative expression in Ukraine and Belarus as a form of opposition to Russia's influence Beyond academia, Diana is a committed antiwar and decolonization activist, working with several major organizations, including those designated as terrorist and extremist by the Russian government "DecolonizingRussianIdentity:ExaminingtheRoleofNon-RussianEthnicGroupsinPutin’sRussia" Thispaperexplorestheroleofnon-RussianethnicgroupsinshapingRussianidentityunderPutin’sregime, challengingthe dominantnarrativesthatcenterethnicRussianswhilemarginalizingindigenousandminoritypopulationsTheKremlin’snationbuildingprojectpromotesahomogenizedRussianidentity, oftenerasingthecultural, linguistic, andhistoricalcontributionsof non-RussianpeoplesAtthesametime,thestateexploitsethnicminoritiesforpoliticalandmilitarypurposes,disproportionately recruitingthemintothearmedforcesandusingtheirregionsforeconomicextractionThispaperreassessesthesedynamics throughthelensofdecolonialtheory, focusingonthewaysindigenouspeoplesofRussiahaveresistedPutin’sregimeandthe full-scaleinvasionofUkrainein2022 Throughactivism, anti-warmovements, culturalrevival, andtransnationalsolidarity, variousindigenouscommunitiesinRussiachallengestate-imposednarrativesandreclaimtheiragencyByincorporatingthese perspectives, thisresearchhighlightsactsofdefianceagainstRussianimperialismandpresentsalternativevisionsofRussian identitybeyondthestate’scontrolUnderstandingtheseformsofresistanceiscrucialfordeconstructingimperialnarrativesand fosteringamoreinclusiveanddecolonizeddiscourseonRussia’sfuture

Kristofers Krumins, originally from Riga, completed his undergraduate degree in politics and government at Sciences Po, while also spending his last year on exchange at Columbia University Some of his academic interests include politics of emotion, identity, and disinformation, especially focusing on events in the Baltics and Ukraine Despite his studies in the US, Kristofers remains tightly connected with Latvia and has pursued many opportunities there, including interning at the NATO Strategic Communications Centre of Excellence in Riga, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and serving as the UN Youth Delegate of Latvia in 2024

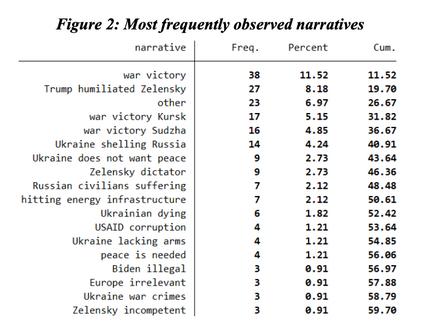

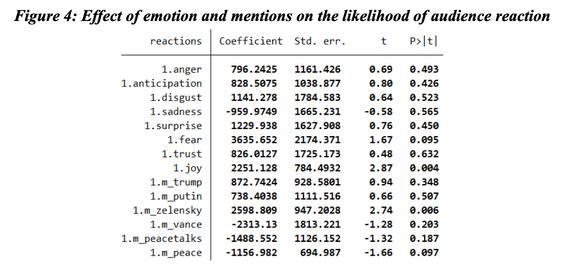

gg g y g g g y monthsof2022(Gerardetal,2024) Withtheonsetofpotentialpeacenegotiationsandastoptothehostilities,thisstudylooks atthemoodamongthetenmostreadRussianTelegramwarbloggingchannelsandassessesthetrendsintheblogospherein late2024andatthebeginningof2025Theresearchpaperanalyzesanoriginaldatasampleanddevelopsacodebooktofilter outspecificemotionalresponsestotheongoingtacticalsituationonthefrontaswellaseventsaffectingthediplomaticrelations betweenRussiaanditsperceivedadversariesImportantly, thepaperaddressesagapinmeasuringthepublicsentimentin RussiatowardsitswarinUkrainebyassessingthepopularityandpublicreactionstothevariouspostssharedbyRussia’swar bloggers

Adriane is an MA candidate at Georgetown University with CERES. After studying both Environmental Biology and Russian in her undergraduate degree, her research concerns the present-day repercussions of the Soviet legacy on science and the region's current environmental, ecological, and bioethical issues, as informed by history, politics, culture and war across Russia, Eastern Europe and Central Asia. "Russia'sAffinityforImmortality"

InFebruary2024, Putinestablishedanewnationalprojectfocusedontransformingthelongevityofitscitizens, aptlytitled “NewHealthPreservationTechnologies” Oneoftheproject'smoreeclecticaimsisextendingRussiancitizens’ lifespans throughthedevelopmentofneurotechnologiesandcellularregeneration. Although, atfirstglance, headlinesaboutPutin’s questforimmortalitymightseemtobeafleetingcuriosityofhisregimeanddesireforpower, Russiahashadaunique obsessionwithimmortalitysincetheearly20thcenturyIconnectRussia’shistoricalrelationshipwiththepursuitofimmortality tothepresent-dayrealityofitsdemographicsandmortalityratestodayRussia’sscientificobsessionwithimmortalitybegana centuryagointhefaceofadevastatingdemographiccrisis, withmillionsdyinginthefewshortyearsofthecivilwarandthe Bolshevikrevolution. Today, asRussia’sbirthratesandadultmortalityspiral, weseeasimilardesiretoextendhumanlife. I investigatenotionsofimmortalityandtheirconnectiontonationalism,withattentiontoparallelsbetweenthe“SovietMan”and whatitmeanstobe “Russian” . ThewayscienceisexploitedtocategorisewhoisandisnotRussianispertinentinthecontext ofRussia’sinvasionofUkraine

Salome Mamuladze is a master's student in Eurasian, Russian, and East European Studies at Georgetown University’s Walsh School of Foreign Service, where she also serves as a Graduate Fellow at CERES. Originally from Tbilisi, Georgia, she earned a B S in Foreign Service from Georgetown University in Qatar, majoring in Culture and Politics with a minor in Government Salome's undergraduate honors thesis explored modern Georgian nationalism and protest culture Her current research interests focus on security dynamics and nationalism in the South Caucasus and the broader Black Sea region. "ManagingDisplacement:APolicyAnalysisofGeorgia’sIDPCrisis" GeorgiahasfacedongoingchallengeswithinternaldisplacementduetoconflictsinAbkhaziaandSouthOssetiasincetheearly 1990s.Asof2023,approximately311,000internallydisplacedpersons(IDPs)remaininGeorgia,presentingsignificantsocialand economicchallenges.ThispaperexaminestheevolutionofGeorgia’sIDPpolicies,withaparticularfocusonhousingassistance.It traceskeypolicydevelopmentsfromthe1990stothepresent,analyzingboththesuccessesandshortcomingsofgovernment strategies Thestudyhighlightsshiftsinapproach,fromaninitialemphasisonrepatriationtolatereffortsaimedatlong-term integration Whilerecentpolicieshaveprioritizedhousingsolutions,inconsistenciesinimplementation,forcedrelocations,and inadequateinfrastructurehavehinderedprogress Drawingonofficialannualreports,thisresearchprovidesacomprehensive overviewofGeorgia’sevolvingIDPpolicies,offeringinsightsintotheireffectivenessandthegapsthatremainByaddressingalack ofEnglish-languageresourcesonthistopic,thestudycontributestoabroaderunderstandingofGeorgia’seffortstosupportIDPs andunderscorestheneedformoresustainableandinclusivepolicysolutions

Lydia Smith (she/her) is a current Masters Student in the European and Russian studies program Her academic interests include the use of AI in combating disinformation, internal displacement in post-conflict zones, the South Caucasus, and the Balkans Her thesis research is on modern policies of internal displacement in Georgia and Armenia Prior to arriving at Yale, Lydia taught English at high schools in Gotse Delchev, Bulgaria and Joinville, France as part of the Fulbright and TAPIF programs. She is originally from Virginia and graduated from the University of Virginia with a degree in Foreign Affairs and minors in French and Russian literature Her undergraduate thesis research was on the efficacy and impact of COVID-19 border closures

Professor George specializes in comparative politics, focusing on ethnic politics, democratization, and state building Her current research focuses on how states undergoing significant transformation and reform address ethnic minorities. Professor George has conducted research in the former Soviet Union, primarily in the Russian Federation and in Georgia, where she was funded by the Fulbright Association Professor George is the author of The Politics of Ethnic Separatism in Russia and Georgia (Palgrave Macmillan, 2009), as well as articles in Europe-Asia Studies, Post-Soviet Affairs, European Security, and Central Asian Survey She has written chapters for inclusion in The Politics of Transition in Central Asia and the Caucasus: Enduring Legacies and Emerging Challenges (Routledge, 2009) and Conflict in the Caucasus: Implications for International Legal Order (Palgrave Macmillan, forthcoming 2010).

Yuni Zeng is currently pursuing her MA degree in European Studies at University of Amsterdam, specializing in the Identity and Integration track Her research interests focus on nationalism in contemporary Europe and the intersection of musical decolonization with identity politics She explores how cultural expressions, such as music, contribute to national and transnational narratives, highlighting the complexities of identity formation and integration With 10 years of experience performing in an orchestra, she brings a unique practical perspective to her academic work, connecting her deep understanding of music to her research on identity. By bridging historical legacies with modern sociopolitical transformations, she seeks to contribute to a deeper understanding of identity within the European context "DecolonizingCzechMusic: Má vlastandtheStruggleforCulturalAutonomyfrom HabsburgRuletoSovietInfluence"

Duringthe19thcentury,CzechcomposersfacedtheculturalhegemonyoftheAustro-HungarianEmpire,whereGermanmusicdominated artisticinstitutionsandintellectualdiscourse.Inthiscontext,BedřichSmetana’sMá vlastemergedasapowerfulmusicalstatementofCzech nationalidentity,challengingtheGermanictraditionsthathadshapedCentralEuropeanmusic.Thisarticlechallengesthebinaryofcolonizervs. colonizedbyapplyingpostcolonialandtransnationaltheoriestoCzechmusicalnationalism.RatherthanviewingMá vlastasamerereaction againstGermanculturalcolonization,thisstudyexaminesitscosmopolitanentanglements fromFranzLiszt’ssymphonicpoemmodeltothe roleofHabsburgculturalpoliciesinfosteringCzechidentity.ThisstudyinvestigateshowCzechcomposersaccumulatedmusicallegitimacyand institutionalinfluencetoassertadistinctnationalidentitythroughPierreBourdieu’sconceptofculturalcapital Thisarticlealsoexamineshow Má vlasttranscendeditsoriginalnationalistcontext,becomingasymbolofCzechresistanceunderNazioccupationandapillarofpostHabsburgculturalheritage ExpandingthisperspectivetotheColdWarera,italsoexploreshowMá vlastfunctionedasasubtleassertionof CzechculturalidentityunderSovietculturaldominance,highlightingitsenduringroleinthereclamationofCzechartisticautonomyacross imperialandpost-imperialEurope

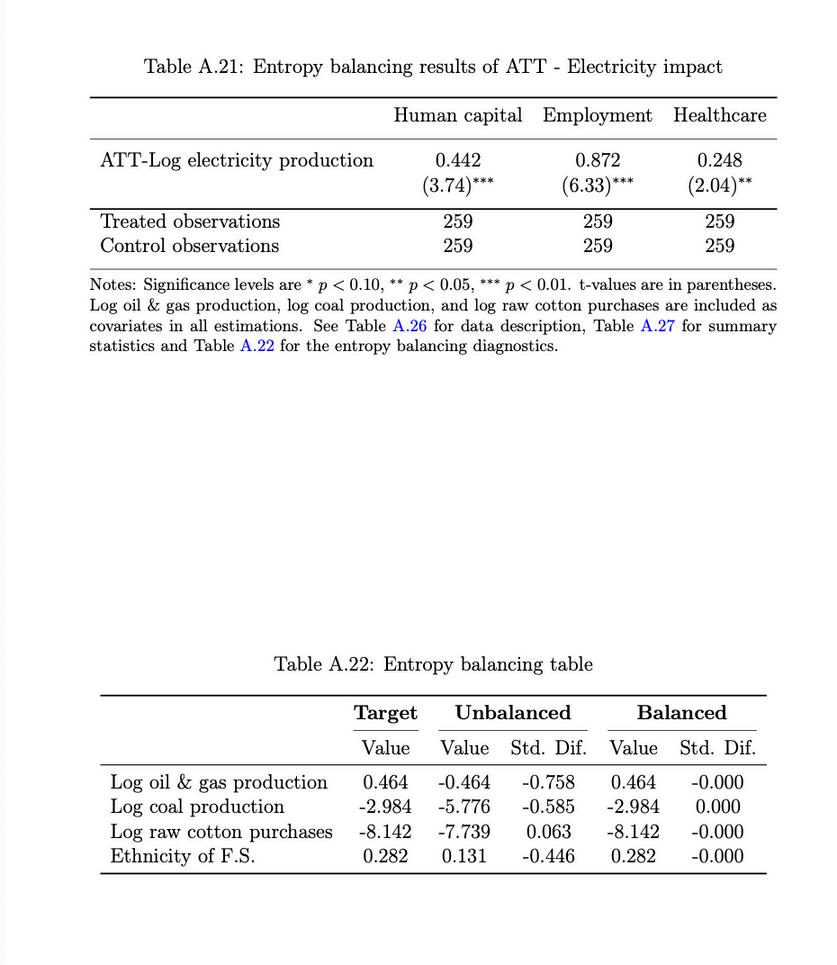

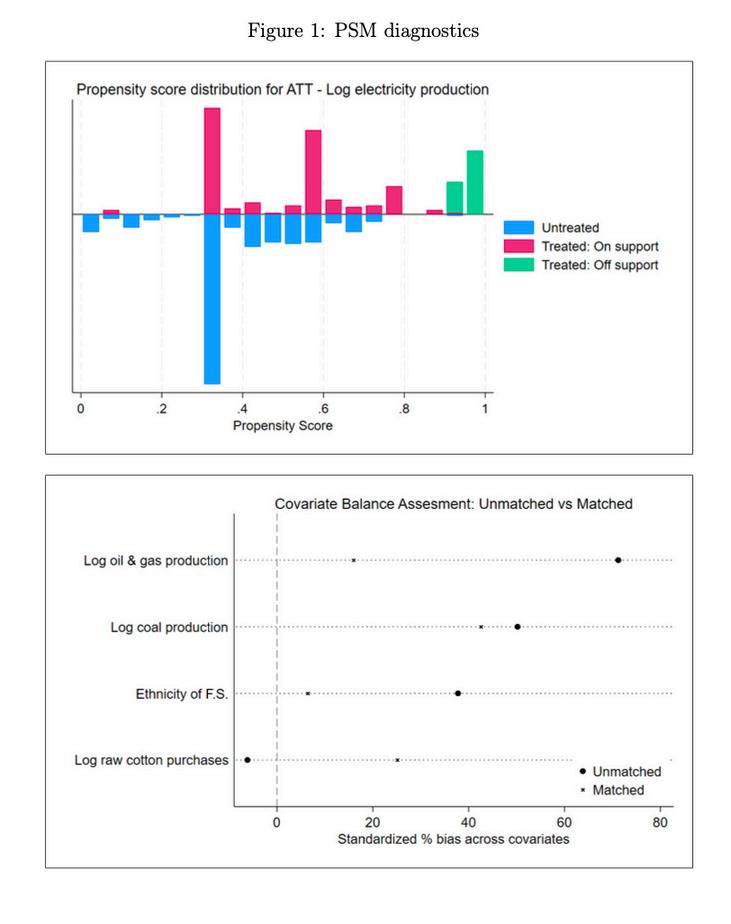

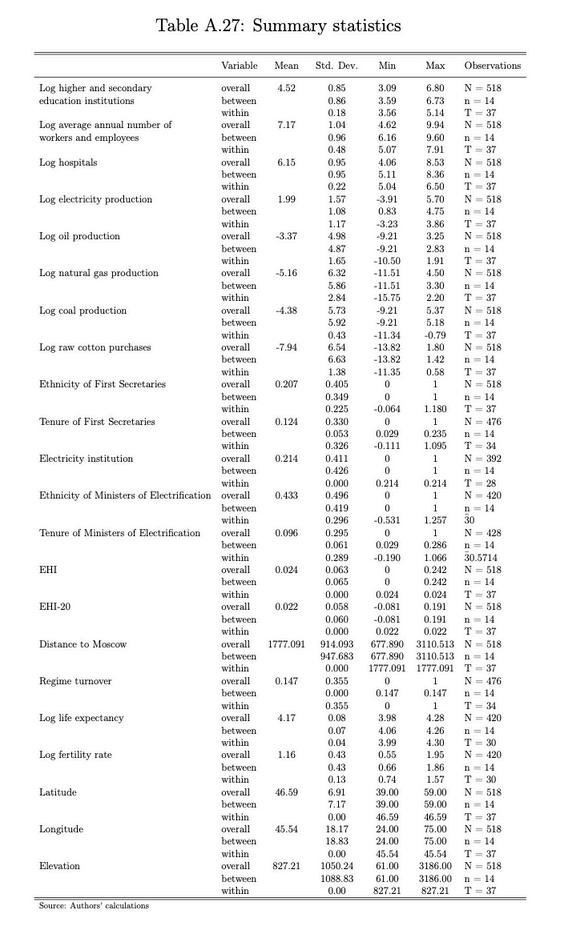

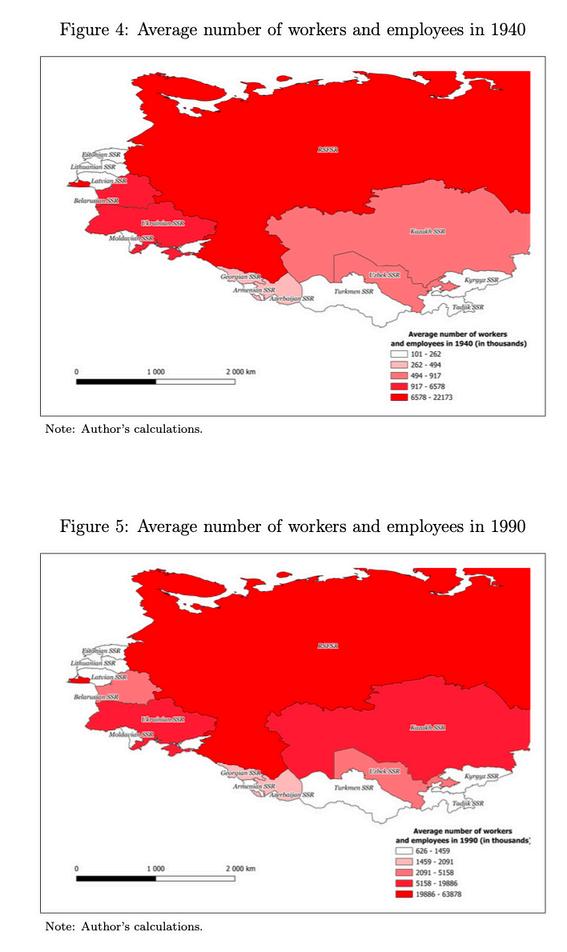

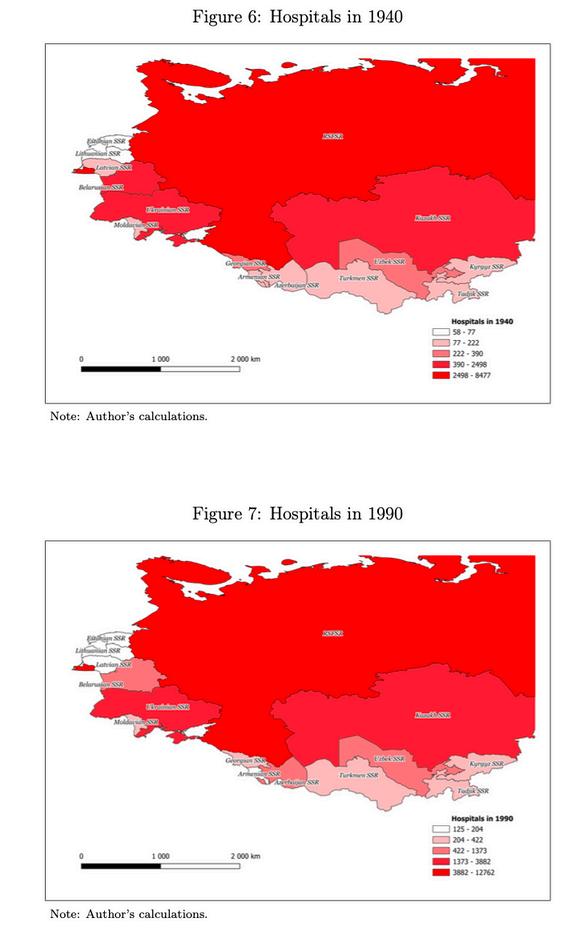

Agzamkhon Niyazkhodjayev is a Ph D candidate in Economics at Institute for East European Studies and School of Business and Economics at Freie Universität Berlin. His research primarily focuses on the economic history and development of postSoviet countries, with a particular emphasis on Central Asia Agzamkhon holds a Master of Science in Applied Economics from Westminster International University in Tashkent and has extensive working experience in the energy sector He is also a scholar of the "El-Yurt Umidi" Foundation initiated by Uzbekistan "Electricity&SocioeconomicPerformance:EvidencefromtheShortSovietCentury" ThisstudyexaminestheimpactofelectrificationoneconomicandsocialdevelopmentintheSovietUnion’snon-Russian unionrepublicsthroughoutthe20thcentury Utilizingofficialstatisticalrecords,thispaperprovidesanovelquantitative analysisoftherelationshipbetweenelectricityproductionandkeysocioeconomicindicators, includinghumancapital, employment,andhealthcaredevelopment Toaddresspotentialendogeneityconcerns,Iemployapproaches,leveraging earlySovietelectrificationpolicies,administrativedecentralizationinstitutions,andtheethnicityofMinistriesofelectrification instruments.Additionally,entropybalancingisusedtoensurecovariatebalanceinobservationaldata,improvingcausal inference. Aplacebotestisimplementedtoverifythattheobservedeffectsaredrivenbyelectrificationratherthan confoundingfactors.ThefindingsrevealthatelectrificationsignificantlycontributedtopublicgoodsdevelopmentinSoviet republics,withclearpath-dependenteffectsinfluencedbyhistoricalpolicydecisions.However,theethnicityofpolicymakers inchargeofelectrificationisinsignificant.Incontrast,theethnicityofFirstSecretariesishighlysignificant,withSlavicleaders receivinggreatereconomicbenefitsandprioritizationfromthePolitburoAdditionally,resourceextractionwassystematically observedinseveralUnionrepublics,reinforcingeconomicdisparitiesbetweenregions

Nicholas Pierce is a second-year graduate student at the Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies at the University of Texas at Austin, where he also received his B A in History and Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies in 2023 His research interests include comparative history between the United States and the Soviet Union/Russia, processes and problems of modernity, comparative frontiers, the history of nomads, and the Russian language His current research is a comparative history of “high modernity” in the 1930s in Roosevelt’s USA and Stalin’s USSR "'ForcingtheGatesoftheFuture':DamsasSitesofHighModernityinRoosevelt’sUnitedStatesandStalin’s SovietUnion"

The1930ssawadecisiveturntostateactionintheUnitedStatesandSovietUnion,wherethestate,buildingonprecedents ofplanningfromWWI,mobilizedphysicalandintellectuallabortoenactfundamentalchange Usingtheframeof“high modernity”asdescribedbyJamesCScott,myworklayoutacomparativeanalysisofthe1930sinthesetwosupposedly opposingsystems,withthegoalofshowingthesimilaritiesandkeydifferencesofAmericanandSoviet“highmodernity”If highmodernitycanbesaidtohaveacentralsymbol,onewouldbehardpressedtopointtoanyotherthanthemassive concreteandsteeldamsthatwereconstructedacrosstheUSandUSSRinthe1930s.FromtheHooverDamtotheTVA,from theDniepertotheVolga,thesestructuresliterallysubmergedthepastintheinterestsofpowergenerationandthecontrolof nature Theyalsochangedthehumangeographyoftheseregions,displacingthepopulationswhowereoftenseenas backwardsorundeveloped Therefore, Ilookatdamsandtheirconstructionsassitesofhighmodernityinpractice, transformingthephysicalandhumanworldtobettersuitanideaofanefficient,modernfuture.

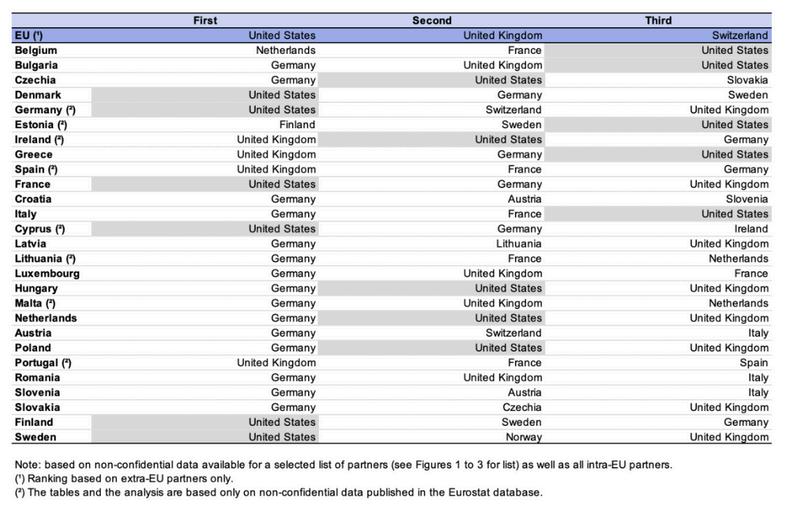

Carlo Giannone is a Master in Public Policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School, sponsored by BCG, Fulbright and Zegna scholarships. He works as Teaching Assistant for Economics Professor Robert Lawrence, former Economic Advisor of President Clinton, and as a Research Assistant for Professor Eric Rosenbach, former Chief of Staff of US Pentagon He is also part of the organizing team of the 2024 EU Conference, one of the most important events on Europe in the US Prior to HKS, he worked as a policy consultant at BCG in Middle East focusing on geopolitics, foreign direct investments, industrial and foreign policy as well as at FleishmanHillard in Brussels focusing on public affairs He holds a bachelor’s in economics from Bocconi University and a master’s degree in international management from the London School of Economics and Bocconi University where he also serves as an elected member of the Board of Bocconi Alumni. Carlo also currently contributes to several Italian newspapers, hosts a top-100 Italian podcast on geopolitics and economics"Finanza, Pizza e Mandolino" , and is a selected ISPI, OECD and Bocconi University Future Leader "EUTradePolicyintheEraofProtectionism:De-riskingfromUS" TheUnitedStatesremainstheEU’slargestexportmarketie, overEUR529BnbetweenNov2023and2024, makingtransatlantictraderelations criticalforEuropeaneconomicstability There-electionofDonaldTrumpandhisadministration'srenewedpushforprotectionistmeasures, includingtherecentlyannouncedtariffsonsteelandaluminum, haveheightenedconcernsacrosstheEUabouttradedisruptions Thispaper evaluatestheEU’sexposuretoUSprotectivemeasuresandassesseswhetherandhowtheEUcouldreduceitsrelianceontheAmericanmarket ThispaperfirstlyanalyzestheextentofEUmemberstates' relianceonUSmarketsforbothgoodsandservicesusingtradedata. Thendrawing fromtheEU’slearningsinreducingdependencyonRussiangas, Iexplorewhethersimilarde-riskingeffortsarenecessaryandfeasibleinthe transatlantictradecontextThroughacombinationofdataanalysisandexpertinterviews, Ievaluatepotentialmarketsandpolicymechanismsto diversifyEUtradeandenhanceeconomicresilienceByexploringthesedimensions,thispaperaimstodemonstratewhethertheEUcanreduceits economicdependenceontheUSmarketandestablishitselfasastrongglobalplayer,regardlessoffuturepoliticalshiftsintheUS

Justine Haekens is currently pursuing her LL M degree at Harvard Law School while simultaneously working on her PhD at the KU Leuven Her dissertation focuses on the concept of market power in EU competition law, on which she has published in Belgian and European academic journals Justine is involved in the Harvard European Law Association and the Belgian Student Society at Harvard, as well as in the Case4EU Project She holds a masters degree from the KU Leuven and has studied at the University of Edinburgh as part of her degree "HowDoesCorporateWealthTranslateintoMarketPower?" CompetitionlawinEurope, asestablishedintheTreatyontheFunctioningoftheEuropeanUnion (TFEU) initsTitleVII, Chapter1, iscrucialforpreservingfairmarketconditions, protectingconsumerinterests, andpromotingeconomicefficiencybypreventing anti-competitivepracticesandensuringalevelplayingfieldforbusinessesBuildingoneconomicstudies, thisresearchaimsto understandwhetherfinancialpowershouldbeastand-alonecriterionwhenestablishingdominanceorevaluatingmergersTodo sothelinksbetweenfirmsfinancialwealthandmarketpower, aswellasitsrelevancetoEUcompetitionlaw Thispaperwill thereforeconsiderthe ‘deeppockets’ theory, whichclaimsthatwealthandresourcesareasourceofpowerThistheoryargues thatextensivefinancialandotherresourcesgivefirmsanunfairadvantageovercompetitors, whichtheycanusetosellbelow costsasastrategytodrivecompetitorsoutofthemarketThistheoreticalframeworkwasdevelopedinthesecondhalfofthe20th centuryandwasrefutedrelativelyquickly. Usingnewempiricaleconomicstudies, thispaperwilldeterminewhetherthelegal theoryhaseconomicrelevanceinthecurrentEuropeanmarket

s a graduate student in the Economics department broadly interested tariff pass-through in supply chains, d platform markets In his job market paper, he is exploring welfare effects of recent protectionist tariffs that mposed on European food products. His other work is focused on incorporating modern ML methods in ughalongtheSupplyChain:EvidencefromLiquorIndustry" tsofa2018tariffonEuropeanliquorproductsalongthesupplychain.Incontrasttorecentwork,wefind attheborderisincompleteandthatmostofthepriceincidencefallsonforeignfirms.Tariffeffects thedomesticconsumerbutwerefurtherabsorbedbyretailerswhodecreasedtheirmarkups.Surprisingly, fcompletepass-throughattheconcentrateddistributiontierofthesupplychainconsistentwiththeuseof s.Pricewasnottheonlyresponsemechanismthataffectedconsumersasretailersalsoreducedthe ductsaffectedbythetariff PriceeffectsatthestorewerehighlyunevenacrosstheUSevenfor sestatesWeshowthatdifferencesinsupplychainstructureinducedbystatelawscouldexplainsomeof s-throughinneighboringstates

Lili Vessereau is the co-chair of the European conference and a Teaching Fellow for Infrastructure finance, Public Finance, and Introduction to Microeconomics at Harvard. She is also a Research Scholar at the Center for International Development, a Research Assistant at the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business and Government, working respectively on green growth and debt restructuring, as well as a Master in Public Policy candidate at the Harvard Kennedy School She is the former Youth Delegate of France to the Council of Europe and a former OSCE Perspective 2030 Fellow. She previously worked for the French Government, the United Nations, and the Center for Strategic and International Studies She holds Master’s Degrees from Sciences Po Paris, La Sorbonne, and HEC Paris

William Hopkinson is a PhD Candidate at the School of Social and Political Sciences at the University of Melbourne His substantive research interests include climate change politics, comparative politics, and set-theoretic methods. As a long-term climate advocate, his PhD research focuses on domestic political processes and the enabling and constraining conditions that shape climate ambition and its change over time His research aims to help scholars, policymakers, and activists better understand how to accelerate more ambitious climate action to meet international climate goals. His work centres on the domestic politics between fossil fuel and green actors over climate policy within OECD member countries In addition to his research, William also works as a teaching associate and research assistant across environmental and international politics at the University of Melbourne. William has a long-standing interest in multi-disciplinary climate approaches and is a member of a collaborative climate research project between the University of Manchester, the University of Melbourne, and the University of Toronto He holds a Master of Geography from the University of Melbourne and a Master of International Politics from KU Leuven.

"ClimateHybridity:NorwayasbothLeaderandLaggard" TomeettheParisAgreement’sgoals,statesmustincreasetheirambitiontomitigateclimatechangeandacceleratetheireffortsasrapidlyaspossible Pavingthewayforthenet-zerotransition,climateleadershipanditsvariousconceptualformshavebeenheavilydebatedbyenvironmentalscholarsYet, environmentalresearchhasdisproportionatelyfocusedonbinaryunderstandingsofleadershipandlaggardshipwhereintheselabelsformafixed historicalattributionInthisarticle,Iadvanceamoredynamicunderstandingofclimateperformancethroughacloserexaminationofdomesticclimate policiesoccurringovertimethatmaydisruptfossilfuelpath-dependenciesByfocusingonNorway,longregardedasaquintessentialleader,Idrawon originaldataandcontentanalysistoanalyseandexplainNorway’srarepositionasbothaclimateleaderandoneofEurope’slargestfossilfuelexporters Inturn,Ichallengethisleadership-laggardshipbinaryandinsteadofferamorenuancedunderstandinginwhichNorwaysimultaneouslyembodies elementsofleadershipandlaggardshipovertimeBeyondtheNorwegiancase,thishybridcomplexityjustifiesre-evaluatingcommonbinary understandingsofleader-laggardsandtheirwiderapplicationinboththeenvironmentalpoliticsliteratureandthepracticesoftheclimateregime

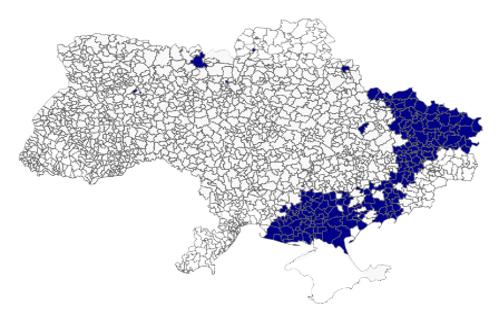

Noah Lloyd is a recent graduate of Georgetown University's Center for Eurasia, Russian, and Eastern European Studies and currently works on the South Caucasus team at the National Endowment for Democracy. Before entering his Master's program at Georgetown, he taught in public and private schools across Eastern Europe and worked as a Russian and Ukrainian translator His academic research has primarily focused on modern Ukraine, specifically issues related to separatism and democratic reform. "TheBattleforLocalAutonomy:DecentralizationProcessesinWartimeUkraine" ThefrontlinesofUkrainerepresentnotonlyastrugglebetweenUkrainiansovereigntyandRussiandomination,orthedefense ofdemocracyagainstautocracy,butalsoacontestbetweentwocompetingmodelsofgovernancewithinUkraineitselfThis paperexaminesthecriticalrolethatdecentralizationhasplayedinUkraine’sresilienceamidRussia’sfull-scaleinvasion, highlightingthewaysinwhichempoweredlocalgovernmentshaveunderpinnedstatestabilityandwartimegovernance.The wartimeheroismofmayorsandlocalofficialsillustrateshowself-governingcommunitieshavebecomevitalpartnersin defendingUkrainianindependenceHowever,martiallawandtheexigenciesofacentralizedwartimecommandstructurehave profoundlyalteredthebalanceofpowerbetweenKyivandtheregions.Localgovernments,oncesemi-autonomousand confident,nowfacegrowingdependenceonthecentralstateSimultaneously,nationaldefenseimperativeshaveconstrained localfiscalautonomy,exacerbatingthesevereeconomicpressuresenduredbyfrontlinecommunitiesMoreover,martiallaw hascurtailedpoliticalpluralismandempoweredKyivwiththeauthoritytoredrawthecountry’spoliticalmap.AsUkrainefights foritssurvival,thefutureofitsmostcelebratedpost-MaidanreformdecentralizationhangsinthebalanceThispaper exploresthesetensions,assessingtheirimplicationsforUkraine’sgovernance,sovereignty,anddemocraticdevelopment beyondthewar

Christina Oh is currently pursuing her M A in European and Russian Studies at Yale She holds a B A in Linguistics with a Minor in Russian from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill At UNC, Christina conducted extensive counterterrorism research, co-publishing one of the first comprehensive databases of right-wing extremist crime in the United States During her senior year, Christina spent the months following the Russian invasion of Ukraine helping organize the volunteer effort Berlin Central Station, where she translated for refugees using language skills gained through the Critical Language Scholarship program At Yale, Christina plans to research the ethics of modern-day diplomacy between the West and Russia, and the role of state-sponsored propaganda in the Russian consciousness "ExportingRepression:RussianInfluenceCampaignsinMaliandBurkinaFaso" AsRussianinfluenceintheSahelgrows, Africanjournalistshavebeenforcedtocensorthemselvesorriskretaliation The relianceonsocialmediaplatformsovertraditionalnewsmediaintheSahelhasallowedRussiatoshapepublicperception throughstate-fundedmediasuchasRussiaToday, andPrivateMilitaryCompanies (PMCs) havefurthererodedtheinformation ecosystemintheregionAlthoughtheKremlin’sdisinformationcampaignsoutsideofRussiahavegrown, thereislittleanalysis analyzingtheaimsofPMCsdistinctlyfromthatofPutin, andthesocio-historicaltaxonomyoftheRussiandisinformationnetwork inAfricaisstillnotthoroughlyinvestigatedintheliteratureThisstudyaimstodistinguishRussia’sAfricaPolicyfromtheaimsof Russia’sprivatesector, andanalyzehowRussiahasexporteditsdomesticrepressioncapabilitiesintoAfricannationsinthe Sahel.TheresearchstudiesRussia’sdomesticmediarepressionapparatusandutilizesacomparativeanalysisofcurrentRussian mediacampaignsinMaliandNigertoprovideinsightintothedomesticrepressionapparatiexportedtoAfrica, andthenovel waysinwhichjournalismisrepressedinthesenations. Thisanalysiswillprovideanewopportunitytoassesshowthese campaignsareinformedbythedomesticRussianpersecutionsystem.

Jonathan Bach is the Interim Dean of SUS and professor of global studies in the Global Studies Program, and faculty affiliate in the Anthropology Department at The New School His recent work explores social change through the politics of memory, material culture, and urban space, with an emphasis on transitions in Germany and China He is the author most recently of What Remains: Everyday Encounters with the Socialist Past in Germany (Columbia University Press, 2017), and co-editor of Re-Centring the City: Urban Mutations, Socialist Afterlives, and the Global East (UCL Press, 2020) with Michal Murawski, and co-editor of Learning from Shenzhen: China’s Post-Mao Experiment from Special Zone to Model City (University of Chicago Press, 2017) with Mary Ann O'Donnell and Winnie Wong His articles have appeared, inter alia, in China Perspectives, The British Journal of Sociology, Memory Studies, Cultural Anthropology, Cultural Politics, Public Culture, Theory, Culture and Society, and Philosophy and Social Science His first book Between Sovereignty and Integration: German Foreign Policy and National Identity after 1989 (St Martin’s Press, 1999) examined questions of normalcy and responsibility in Germany during the early years after unification. He holds a Ph.D. in political science from the Maxwell School at Syracuse University and has held post-doctoral fellowships at Columbia University (ISERP) and Harvard University (Center for European Studies)

Valerie Browne graduated from West Virginia University with a double major in English and Russian studies and a minor in political science As an undergraduate, she served as head research assistant for the West Virginia Dialect Project and was an intern Russian translator with Global Wordsmiths’ Language Access Project Her research centers on the sociolinguistics of the post-Soviet space, exploring ways in which conflict and evolving national identities impact language choices in the region Valerie is a two-time recipient of the Critical Language (Russian) Scholarship, participating in programs online and in Bishkek, Kyrgyzstan She spent the 2022-2023 academic year in Krakow, Poland, teaching English and volunteering with Ukrainian refugees as a Fulbright English teaching assistant "AccessingNationalBelonginginKazakhstan:RussophoneAlmatyntsyandtheKazakhlanguagelearning movementinthewakeofRussia'sfull-scaleinvasionofUkraine" Russia'sfull-scaleinvasionofUkraineonFebruary24,2022reverberatedthroughouttheworld,butithitveryclosetohomeformanyinthepostSovietspaceandwaskeenlyfeltinKazakhstanduetoacomplexinterplayoftheBloodyJanuaryeventsprecedingRussia'sattackonUkraine, previousRussianthreatstoKazakhstan’sterritorialintegrity, andSoviet-coloniallegacies. Russia'sinvasionwithinthecontextofKazakhstan's recentpoliticalturmoilwasamomentofprofoundrupture,sparkinga"crisis"ofnationalidentitythatledmanyRussophoneurbanitesinAlmatyto endeavortolearnormasterKazakh Employingdatafrom23semi-structuredinterviewswithlocalKazakhlanguagelearners, teachers, and activistsfrom4Kazakhspeakingclubs, IanalyzethewaysinwhichthiscrisisofidentityledtoanincreasingdemandforKazakhcontentamong RussophoneKazakhcitizensinAlmaty HighlightingtheroleofKazakhspeakingclubsasapowerfullocusforfulfillingthedemandto "feel Kazakh" , IexplorethewaysinwhichRussophoneKazakhcitizens, regardlessoftheirethnicity, areturningtotheKazakhlanguagefornational self-definitioninwaysthatdestabilizepreviouslyexistingethnicandcivicdichotomies(KazakhvsKazakhstani)

Tanya (Tetiana) Kotelnykova is currently pursuing an MA in Russian, East European, & Eurasian Studies at Yale University. She holds an M A in Human Rights from Columbia University and a B A in Law from Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv Tanya's journey began when she was displaced from her home in Eastern Ukraine in 2014 due to the Donbas occupation. In 2022, she was in Kyiv during the city's encirclement by Russian forces and witnessed the full-scale invasion of Ukraine Tanya is the founder of Brave Generation, a non-profit organization based in NYC, dedicated to uniting and empowering young Ukrainians for post-war reconstruction Additionally, Tanya serves as a project coordinator at the Boris Nemtsov Foundation for Freedom, where her role involves enhancing democracy promotion workshops, and the Nemtsov forum as well as overseeing the management of the scholarships related to Ukrainian students Also, Tanya manages the “Ideas for Russia” project, exploring Russia in the era of non-transparency and isolation

David R Cameron is a Professor of Political Science at Yale and the Director of the Yale Program in European Union Studies He received his B A from Williams College, an M B A from Dartmouth, an M Sc from the London School of Economics and Political Science, and his Ph.D. from The University of Michigan. He teaches courses on European politics and the European Union

He has written about the impact of trade openness on government and, with respect to the EU, the operation of the European Monetary System, the negotiation of the Treaty on European Union, Economic and Monetary Union, the eurozone crisis, the creation of democratic polities and market-oriented economies in central and eastern Europe, the crisis in Ukraine and, most recently, Brexit

Mike York is pursuing an M.A. in European and Russian Studies at Yale University. He earned a B.A. in History from Southwestern University in 2011 and an M A in History from Yale in 2017 Mike retired from the United States Army in 2023, where he deployed in the Infantry, Air Defense Artillery, and as a Civil Affairs officer in Special Operations He served as a civil-military liaison with the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) and has experience coordinating with humanitarian and non-governmental relief organizations. He is interested in the successes and failures of traditional civil society institutions within the context of mass radicalization in interwar Europe, especially the mechanics of societal transformation in Germany Mike is also interested in the reception of refugees and statelessness, as well as violent extremism, the growing appeal of illiberalism, and the war in Ukraine.

Andrei Kureichik, a Belarusian dissident and writer in exile known for his opposition to the authoritarian regime in Belarus, will be engaging in a dialogue and discourse centered around Ales Bialiatsky, a prominent Belarusian political prisoner and recipient of the Nobel Peace Prize 2022 Bialiatsky is currently being detained by the regime of President Lukashenko in a facility with the highest levels of security. In many nations, the defense of human rights transcends mere activism and instead presents a formidable obstacle to the oppressive machinery of the totalitarian regime Belarus and Russia serve as illustrative instances In this discussion, the focus will be on individuals who actively advocate for the protection and promotion of human rights. This discussion pertains to the establishment of the human rights center “Viasna” in Belarus by Ales Bialiatsky, as well as the human rights society “Memorial” in Russia, which has also been recognized with a Nobel Prize 2022

1

2

PANEL I: Echoes of War: Examining the Impacts of Violent Conflict in Eurasia

PANEL I: Echoes of War: Examining the Impacts of Violent Conflict in Eurasia

Chair: Oliver Wolyniec (Yale University)

Chair: Oliver Wolyniec (Yale University)

Faculty Discussant: Prof. David Simon (Yale University)

Faculty Discussant: Prof. David Simon (Yale University)

Rowan Baker (Yale University)

Rowan Baker (Yale University)

Alice Mee (Columbia University)

Alice Mee (Columbia University)

Paradise

Rowan Baker (Yale University)

Rowan Baker (Yale University)

A palm gently swayed in the oceanside breeze, which carried the faintest scent of citrus and eucalyptus. Her bedroom window overlooked the Black Sea coastline, as she sat in the cool, freshly furnished apartment of walnut wood and oak. “Abkhazia is the most beautiful place. It is like Europe. The palm trees and the sea. The fresh fruit It’s paradise ” Eko smiled softly, attentively yet gently looking at a photograph of the Sukhum/i from the 1980’s as she recalled her childhood before the war (Figure 1). Gradually, she trailed off in her words, and her interlude into her childhood bedroom stopped. She paused for ten seconds, her face tensed with anger, and still examining the photograph, “But it was stolen from us It was our territory, and they took it all away. It isn’t the Abkhazians They aren’t from there Abkhazia is

Georgia’s” (1). She had now returned to our conversation in a small courtyard café under the Tbilisi summer sun and hot mountain air. While Eko had lived in Tbilisi for over 30 years, she could never see herself as anyone but a Suhkumchanka (woman from Sukhum/i), “You live in a place, but it is a place that is not yours.” In what context did Eko’s conviction that where she lives is “not hers” come about?

Eko’s connection to the “paradise” of Abkhazia following the 1992–1993 Georgia-Abkhazia War was common among the Georgian-Megrelians displaced from Sukhum/i that I interviewed (2). The sight of the palm trees, the smell of eucalyptus and citrus and the resort buildings reminiscent of “Europe” wove together the histories

1

Rowan

Baker (Yale University)

of “homeland.” She could vividly recall her childhood playing along the stoney sand of the Black Sea, and her mother’s childhood garden in Ochamchire/a, Abkhazia, just 53 kilometers south of Suhkhum/i She could even piece together what she believed her grandmother’s life had been, somewhere between the citrus plantations and the kitchen. However, she could not project her histories before the 1930’s, “I think my great grandmother was from Western Georgia, just north of Zugdidi…” another pause, followed by a quick response to her own words, “But it is all Georgia’s anyway. Abkhazia can only be Georgia. So, it doesn’t matter.”

But just as easily as Eko could recount her positive memories of home, as well as the histories of “homeland” that she herself did not experience, she could pinpoint the pain of her displacement from Abkhazia. She accounted the confusion of her weeks long march from Sukhum/i with her mother and grandmother through the winter mountains of Svaneti, as she observed the others “sleeping” alongside the road. She described the sadness of the remainder of her childhood in displacement, first in Zugdidi, then in Tbilisi, as it was engulfed by her grandmother’s wails for her home and for return, by the blackness of her grandmother’s widowers’ clothes, by the deafening silence of her mother, and by the taunts of her classmates as to her identity of being a refugee.

Despite the weight of her stories, instead of immersing herself in her memories as with her description of Sukhum/i, she distanced herself from her status as the displaced, and from her negative experiences through the consistent use of “you.” Her living memories of herself, her mother, and her grandmother among the palm trees and the citrus plantations. Her experience as the settler in Western Georgia and then in Tbilisi, and as someone displaced from Abkhazia, were instead superimposed onto the “settler” of the Abkhaz, “It is our [Georgians’] homeland They are not from here [Abkhazia] ”

Contrary to Eko, Adgur, an Abkhazian living in Sukhum/i, could no longer see Abkhazia, or Sukhum/i, as a paradise (Figure 2) (3). While he could recount his childhood bug collection 40 kilometers northeast of Sukhumi at his grandmother’s home near Gudauta, and his youth among the walnut and oak trees, his memories as a young adult in Sukhum/i during the war, and the ensuing environmental and subsequent cultural destruction permeated his accounts of life, and his memories, in Sukhum/i, “Our palm trees are dying,

3 What is recognized as present-day Abkhazians are composed of numerous people groups and religions, with ethnicities within the territory including but not limited to Greeks, Armenians, Estonians, Africans and other Circassian peoples To protect the identity of those I interviewed who do not identify as ethnically Abkhaz, given that their respective populations in Abkhazia were drastically reduced during the war from displacement, I will use the term Abkhazian to describe any interviewee that is currently based in Abkhazia

Rowan Baker (Yale University)

and you can no longer smell the sweet oils of the eucalyptus. Our culture is no longer accessible to us.”

Over the span of three decades, he described Sukhum/i’s transformation from a paradise to a paradise lost to war, and then in steady decline from isolation. The onslaught that war brought left the resort buildings burned and in ruin. The sound of the constant fighting and bombing displaced coastal wildlife like dolphins and seabirds from the shores. And the isolation of Abkhazia from the rest of the world system as a separatist state led to massive deforestation in the region’s forests, like those of his childhood, to sustain the local economy after the downfall of the tourist economy. But unlike Eko, Adgur told his story in a linear progression one in which Abkhazia was a paradise of palms and eucalyptus, walnuts and oaks, dolphins and seabirds. This paradise was itself then changed from the war the resorts to disappearing in ash, the dolphins and seabirds to far shores of the Black Sea, the timber exported to Türkiye, and the Abkhazian’s that remained displaced from the only Sukhum/i, the only environment, and only culture they themselves had ever experienced.

These memories and experiences then culminated in the present tense experience of Abkhazians in which their region remained isolated from the rest of the world due to “the mythical idea of Georgian territorial integrity,” and as a result, projected into the future the histories of this decline. Even the downfall of the palm trees and the citrus groves were ultimately felt as an afront to Abkhazians by Georgians, “We now have the palm weevil and that bug [Brown Marmorated Stink Bug]. They are killing our trees [palms and citrus] They [Georgians] do not realize how they have made Abkhazia suffer They killed us, and then they killed our trees We have lost everything What do we have left?” Despite their differences, Adgur and Eko shared a similar lapse in their historical memory: he could not fully account for his family’s histories before the 1930’s. He did, however, draw his connections to the natural environment to his projected memories of village, “The trees have been there for hundreds of years. And my family has been there with them.”

Her stories muffled by cracks of thunder, roaring rain, and the rush of water gushing through the streets of Zugdidi, Nino described her life crossing the Engur/i river, and the border of Abkhazia and Georgia, from Gal/i, to Zugdidi, and back again. Growing up isolated from both capitals two hours southeast of Sukhum/i and six hours northwest of Tbilisi, her understanding of Abkhazia and Western Georgia was not that of a paradise, or a paradise lost She did not connect her memories of herself, of the histories of her family, or of her culture to palms or the sea. Instead, her stories intertwined with that of her family’s farm in Gal/i, and her family’s small room in an abandoned schoolhouse in Zugdidi following the war, “In Zugdidi we had no light. No electricity. And we shared our home with 40 other people. … I don’t

Rowan

Baker (Yale University)

understand why we are fighting. It is Georgia … ” looking out at the rain, she took a breath, and resumed, “But when we felt it was safe for Georgians to return, we would go at night across the border We would go back to our home in Gal/i ” She vividly described the shade of the cornstalks, the fresh smell of mandarins, and the constant clucking of chickens (Figure 3). However, much like Eko and Adgur, she could not recall her family histories before the 1930’s, “My parents are still there. My grandparents are from there. But before that, I don’t think it matters.”

But Nino also explained the inaccessibility of being able to return to Abkhazia with her children as an adult Crossing the Engur/i river is a double threat for those who make their lives between Georgia and Abkhazia specifically from getting caught by border guards, or from drowning, “I understand now that what we did when I was younger was very dangerous. I won’t put my children through that ” But seeing her parents is worth the personal cost, “I go back for them [her parents] of course. They won’t leave our farm or our house. There are too many memories there for them.”

Much like Adgur, her stories were linear. There was no displacement of time as Nino spoke There was no overt assertion as to what land had been taken and by whom But there were three constants in how Nino viewed the Abkhazia of the past and the Abkhazia of the future Firstly, that while her family had lived in Abkhazia from at least the 1930’s, her concerns were not as concentrated in projecting histories beyond the living memory of her parents. For Nino, the region to her and her family, and her memories of home, were based on understandings of village life and agricultural production. In this respect, Gal/i and Zugdidi were nearly identical, and while she may have been displaced by the war, there were no major changes in the natural environment for her, her children, or her family. And finally, that she did not feel the strong desire to return as Eko She viewed the region, both Gal/i and Zugdidi, as homeland, and did not project return to Gal/i into her children’s future.

The histories of Eko, Adgur, and Nino demonstrate their markedly different understandings of the history of Abkhazia They all disagreed with their temporal understanding of Abkhazia and what it represents

Rowan Baker (Yale University)

today. Eko understands Abkhazia as a continued paradise, while Adgur views Abkhazia as a paradise only in distant memory Meanwhile, Nino’s view of Abkhazia was one not of paradise at all, rather a region in which agriculture was a feature of everyday life They also converged in how they viewed Georgians or Abkhazian’s respectively. For Eko and Adgur, they view their respective “other” as an unwanted settler of Abkhazia who has taken away their land and culture. Meanwhile, they assert their claims as rightfully indigenous to Abkhazia.

Critically, Eko, Adgur and Nino could not recall their family histories beyond the 1930’s, and all connected their identities to the natural world. Eko and Nino to the non-native species of Abkhazia—the palms and the citrus plantations respectively. Adgur, meanwhile, also connected his identity to nature, but in his case, it was not just an environment for which he was concerned, but also one of native species such as the walnut and the oak. While Eko did connect her memories of home to the walnut – albeit through the furniture of the home she left behind she and Nino instead conceptualized the symbols of their homeland as non-native palms, eucalyptus, citrus, and farmland introduced to Abkhazia by the Russian Empire and Soviet Union only a century ago Their resorts Their palms Their furniture Their plantations

‘SIGNING YOUR OWN SENTENCE’ (1): UKRAINIAN PRESIDENTIAL DISCOURSE ON COLLABORATORS IN THE FIRST TWO

‘SIGNING YOUR OWN SENTENCE’ (1): UKRAINIAN PRESIDENTIAL DISCOURSE ON COLLABORATORS IN THE FIRST TWO YEARS OF RUSSIA’S FULL-SCALE INVASION

Alice Mee (Columbia University)

Alice Mee (Columbia University)

Introduction

Wartime collaborators occupy an inherently paradoxical position, representing an enemy that also internal to the nation It is this paradox, and its ramifications for national identity, which I explore in this paper

Wartime collaborators occupy an inherently paradoxical position, representing an enemy that is also internal to the nation. It is this paradox, and its ramifications for national identity, which I explore in this paper.

The origins of the ‘collaboration’ perhaps surprisingly, fairly recent. Indeed, it only acquired its contemporary meaning, of working with an during the Second World War, when it came be used in reference Vichy France (1). However, the has in ambiguity, with little consensus on the extent of intent implied in its usage or on its connection to the related concept of treason (2) It is, nevertheless, possible to isolate two characteristics of actions most frequently considered to constitute collaboration: firstly, cooperation with an enemy of one’s country; secondly, such actions are carried under occupation (3).

The origins of the term ‘collaboration’ are, perhaps surprisingly, fairly recent Indeed, it only acquired its contemporary meaning, of working with an enemy, during the Second World War, when it came to be used in reference to Vichy France (1). However, the term has remained mired in ambiguity, with little consensus on the extent of intent implied in its usage or on its connection to the related concept of treason (2). It is, nevertheless, possible to isolate two characteristics of actions most frequently considered to constitute collaboration: firstly, cooperation with an enemy of one’s country; secondly, such actions are carried out under occupation (3)

In case of Ukraine, within weeks of Russia’s invasion in 2022, Ukrainian government laws specifically criminalising collaboration: Articles 111-1 and 111-2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine While a legal discussion of these developments is beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to note that by the two-year anniversary of the full-scale invasion, the Security Service of Ukraine reported over 8,000 against alleged collaborators registered in Ukrainian (5).

In the case of Ukraine, within weeks of Russia’s full-scale invasion in 2022, the Ukrainian government passed laws specifically criminalising collaboration: Articles 111-1 and 111-2 of the Criminal Code of Ukraine. While a legal discussion of these developments is beyond the scope of this paper, it is important to note that by the two-year anniversary of the full-scale invasion, the Security Service of Ukraine reported over 8,000 cases against alleged collaborators registered in Ukrainian courts (5)

President Volodymyr Zelenskyi has long relied on digital means to disseminate his political stances and to speak directly to Ukrainian audiences (6). Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Zelenskyi has published online addresses daily and occasionally more than once daily—to the Ukrainian people on social media and the presidential website. In these videos, Zelenskyi outlines the most pressing issues of the day for the Ukrainian state, including developments in legislation, personnel changes, the status of hostilities and the impact of Russian attacks on Ukraine

Volodymyr Zelenskyi relied on digital means disseminate political stances and to speak directly to Ukrainian audiences (6) Since the start of Russia’s full-scale invasion, Zelenskyi has published online addresses daily and occasionally more than once daily—to the Ukrainian people on social media and the presidential website. In these videos, Zelenskyi outlines the most pressing issues of the day for the Ukrainian including developments in legislation, personnel changes, the of hostilities and the impact of Russian attacks on Ukraine.

In forty-six of these addresses delivered in the first two years of the full-scale invasion, he specifically touches upon collaborators. In the same time frame, he made a further eight speeches published on his administration’s website that mention collaborators in contexts other than these daily addresses. However,

In forty-six of these addresses in the first two years of the full-scale invasion, he specifically touches upon collaborators In the same time frame, he made a further eight speeches published on his administration’s website that mention collaborators in contexts other than these daily addresses. However,

1 Volodymyr Zelenskyi, ‘Shche potribno borotys’ i zavdati vorohu maksymal’noï shkody na vsikh napriamkakh oborony – zvernennia Prezydenta Ukraïny’, President of Ukraine Official Website, 13 March 2022 <https://www president gov ua/news/she-potribno-borotis-i-zavdati-vorogu-maksimalnoyi-shkodi-na-73529>, [accessed December 2023]

>, [accessed 28 December 2023]

2 Jan T Gross, ‘Themes for a Social History of War Experience and Collaboration’, in The Politics of Retribution in Europe: World War II and Its Aftermath, ed by István Deák, Jan T Gross and Tony Judt (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), p 24

2 Jan T Gross, ‘Themes for a Social History of War Experience and Collaboration’, in The Politics of Retribution in Europe: World War II and Its Aftermath, ed by István Deák, Jan T Gross and Tony Judt Princeton University Press, 24

3 States’ of apparent even immediate aftermath of the Second themselves in of

3 States’ differing interpretations of collaboration were apparent even in the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, when they manifested themselves in varying degrees of prosecution

4 Examples of this common framing of collaboration include philosopher Avishai Margalit, On Betrayal (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), p 197, and historian Philip Morgan, Hitler’s Collaborators Choosing Between Bad and Worse in Nazi-Occupied Western Europe (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 1

4 Examples of this common framing of collaboration include philosopher Avishai Margalit, On Betrayal (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University 2017), p 197, and historian Morgan, Hitler’s Collaborators Choosing Between Bad and Worse in Nazi-Occupied Western Europe Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 1

5 Shaun Walker, ‘Jailed as Collaborators: the Stories of Ukrainians Who Ended Up in Prison’, The Guardian, 2 February 2024 <https://www theguardian com/world/2024/feb/02/jailed-as-collaborators-the-stories-of-ukrainians-who-ended-up-in-prison> [accessed 20 February 2024]

5 Shaun Walker, Collaborators: of Who Up in Prison’, Guardian, February 2024 theguardian com/world/2024/feb/02/jailed-as-collaborators-the-stories-of-ukrainians-who-ended-up-in-prison> [accessed 20 February 2024]

6 See, for instance, Joanna Hosa and Andrew Wilson, ‘Zelensky Unchained: What Ukraine’s New Political Order Means for its Future’, European Council on Foreign Relations, 1 September 2019 <https://www jstor org/stable/resrep21659>, [accessed 12 January 2024], p 2

6 for instance, Hosa and Andrew Unchained: What New Political for Future’, European on Relations, 1 September 2019 <https://www jstor org/stable/resrep21659>, [accessed 12 January 2024], p 2

‘SIGNING YOUR OWN SENTENCE’ (1): UKRAINIAN PRESIDENTIAL DISCOURSE ON COLLABORATORS IN THE FIRST TWO YEARS OF RUSSIA’S FULL-SCALE INVASION

‘SIGNING YOUR OWN SENTENCE’ (1): UKRAINIAN PRESIDENTIAL DISCOURSE ON COLLABORATORS IN THE FIRST TWO YEARS OF RUSSIA’S FULL-SCALE INVASION

Alice Mee (Columbia University)

Alice Mee (Columbia University)

the frequency of Zelenskyi’s allusions to traitors varies over time, with the peak arriving in April 2022, when collaborators were mentioned in seven speeches, perhaps with the de-occupation of northern Ukrainian territories and discovery mass human rights violations, such as in Bucha (7) As well as that, the speeches present dynamic variations in the depiction of collaborators, particularly in regard to their relation to the external enemy itself, the Russian military.

the frequency of Zelenskyi’s allusions to traitors varies over time, with the peak arriving in April 2022, when collaborators were mentioned in seven speeches, perhaps in connection with the de-occupation of northern Ukrainian territories and the ensuing discovery of mass human rights violations, such as in Bucha (7). As well as that, the speeches present dynamic variations in the depiction of collaborators, particularly in regard to their relation to the external enemy itself, the Russian military.

this paper, I conduct a thematic discourse analysis of Zelenskyi’s speeches that mention collaborators from the first two of the full-scale invasion, from 24 February 2022 to 23 February 2024, in order to gain insight into rhetorical patterns of official on the subject, and how they vary over time.

In this paper, I conduct a thematic discourse analysis of Zelenskyi’s speeches that mention collaborators from the first two years of the full-scale invasion, from 24 February 2022 to 23 February 2024, in order to gain insight into rhetorical patterns of official discourse on the subject, and how they vary over time.

President Zelenskyi frequently equates the enemy and collaborators in his speeches in the period under study, which is reflected his numerous simultaneous references to Russian military personnel and traitors. The many examples include mentions of ‘countering enemy operations and collaborators’ (8), ‘Russian soldiers, mercenaries and collaborators’ (9), ‘the sabotage activities of Russia and collaborators’ (10), and ‘everything that occupiers and collaborators have done in our Ukrainian land’ (11). Zelenskyi occasionally makes the equation of collaborators and the Russian military explicit, such as his parallel of them on 19 September 2022, when he first states that ‘the Russian military in Ukraine has only two options: escape from our land or be captured’ (12), before adding that ‘collaborators similar options’ (13). A comparable sentiment apparent in that ‘for those Russian soldiers, mercenaries and collaborators who were abandoned in Kherson and other cities of the south [ ] Voluntarily becoming a Ukrainian prisoner is the only option for all occupiers’ (14) In this framework, collaborators are also, notably, occupiers. Zelenskyi thus appears to blur any boundary between invading Ukraine and Ukrainians who betray the interests of Ukraine, hinting at an exclusion of the latter from the national community.

President Zelenskyi frequently equates the enemy and collaborators in his speeches in the period under study, which is reflected in his numerous simultaneous references to Russian military personnel and perceived traitors. The many examples include mentions of ‘countering enemy operations and collaborators’ (8), ‘Russian soldiers, mercenaries and collaborators’ (9), ‘the sabotage activities of Russia and collaborators’ (10), and ‘everything that occupiers and collaborators have done in our Ukrainian land’ (11). Zelenskyi occasionally makes the equation of collaborators and the Russian military explicit, such as in his parallel treatment of them on 19 September 2022, when he first states that ‘the Russian military in Ukraine has only two options: escape from our land or be captured’ (12), before adding that ‘collaborators have similar options’ (13). A comparable sentiment is also apparent in his statement that ‘for those Russian soldiers, mercenaries and collaborators who were abandoned in Kherson and other cities of the south. […] Voluntarily becoming a Ukrainian prisoner is the only option for all occupiers’ (14). In this framework, collaborators are also, notably, occupiers. Zelenskyi thus appears to blur any boundary between Russians invading Ukraine and Ukrainians who betray the interests of Ukraine, hinting at an exclusion of the latter from the national community

7 For more detail on the aftermath of the Russian occupation of Bucha see, for example, ‘Ukraine: Russian Forces’ Trail of Death in Bucha’, Human Rights Watch, 21 April 2022 <https://www hrw org/news/2022/04/21/ukraine-russian-forces-trail-death-bucha>

8 Volodymyr Zelenskyi, ‘Ukraïna dopovniuie svoïmy sanktsiamy mizhnarodni sanktsiini mekhanizmy – zvernennia Prezydenta Volodymyra Zelens’koho’, President of Ukraine Official Website, 23 November 2023 <https://www president gov ua/news/ukrayina-dopovnyuye-svoyimi-sankciyami-mizhnarodni-sankcijni-87229> [accessed 29 December 2023]

9 ‘S’ohodni istorychnyi

8 Volodymyr Zelenskyi, ‘Ukraïna dopovniuie svoïmy sanktsiamy mizhnarodni sanktsiini mekhanizmy zvernennia Prezydenta Volodymyra Zelens’koho’, President of Ukraine Official Website, 23 November 2023 <https://www president ua/news/ukrayina-dopovnyuye-svoyimi-sankciyami-mizhnarodni-sankcijni-87229> 29 December

zvernennia Prezydenta Ukraïny’, President of Ukraine 11 November 2022 president gov ua/news/sogodni-istorichnij-den-mi-povertayemo-herson-zvernennya-pre-79101>

9 Volodymyr Zelenskyi, ‘S’ohodni istorychnyi den’, my povertaiemo Kherson – zvernennia Prezydenta Ukraïny’, President of Ukraine Official Website, 11 November 2022 <https://www president gov ua/news/sogodni-istorichnij-den-mi-povertayemo-herson-zvernennya-pre-79101> [accessed 29 December 2023]

10 Volodymyr Zelenskyi, ‘Tsymy dniamy rosiys’ki vtraty spravdi vrazhaiut’, i same taki vtraty okupanta protibni Ukraïni – zvernennia Prezydenta Volodymyra Zelens’koho’, President of Ukraine Official Website, 20 October 2023 <https://www president gov ua/news/cimi-dnyami-rosijski-vtrati-spravdi-vrazhayut-i-same-taki-vt-86493> [accessed 29 December 2023]

Volodymyr syspil’stvo

10 Volodymyr Zelenskyi, ‘Tsymy dniamy rosiys’ki vtraty spravdi vrazhaiut’, i same taki vtraty okupanta protibni Ukraïni – zvernennia Prezydenta Volodymyra Zelens’koho’, President of Ukraine Official Website, 20 October 2023 [accessed 29 2023]

11 Volodymyr Zelenskyi, ‘Ukraïns’ke syspil’stvo ochikuie spravedlyvosti – Hlava derzhavy pid chas uchasti v urochystomu zasidanni Plenumu Verkhovnoho Sudu’, President of Ukraine Official Website, 15 December 2022 <https://www president gov ua/news/ukrayinske-suspilstvo-ochikuye-spravedlivosti-glava-derzhavi-79893> [accessed 29 December 2023]

Hlava pid chas uchasti v zasidanni Plenumu of Ukraine Official Website, 15 December 2022 <https://www president gov ua/news/ukrayinske-suspilstvo-ochikuye-spravedlivosti-glava-derzhavi-79893> [accessed 29 December 2023]

12 Volodymyr Zelenskyi, ‘Temp nadannia partneramy dopomohy Ukraïni maie vidpovidaty tempu nashoho rukhu – zvernennia Prezydenta Volodymyra Zelens’koho’, President of Ukraine Official Website, 19 September 2022 <https://www president gov ua/news/temp-nadannya-partnerami-dopomogi-ukrayini-maye-vidpovidati-77869> [accessed 28 December 2023]

Volodymyr Zelenskyi, ‘Temp nadannia partneramy Ukraïni maie nashoho rukhu – zvernennia Prezydenta Volodymyra Zelens’koho’, President of Ukraine Website, 19 [accessed 28 December 2023]

13 Ibid

13 Ibid

14 Zelenskyi, ‘S’ohodni istorychnyi den”, 11 November 2022

14 Zelenskyi, ‘S’ohodni istorychnyi den”, 11 November 2022

‘SIGNING

‘SIGNING

Alice Mee (Columbia University)

Alice Mee (Columbia University)

The broad equation of the enemy and collaborators is additionally reflected in Zelenskyi’s statements regarding bringing collaborators to where they consistently suggested merit the same degree punishment as of the Russian He frequently that both Russian soldiers and collaborators will be held accountable, using parallel phrasing, such as his declaration on 13 March 2022 of ‘let the occupiers know, let all the collaborators who they find know, Ukraine will not forgive them

Anyone. For anything’ (15). In this framing, collaborators are positioned as existing outside of the Ukrainian collective; a positioning that also apparent Zelenskyi’s use of the first-person plural ‘we’ to speak on behalf of the nation in his remark that ‘we will identify, find and bring to justice every war and (16). He makes the opposition of and collaborators more explicit still by comparing traitors to artillery and projectiles on 17 July 2022, stating that while it is to count the number of such weapons used against Ukrainians, ‘it is definitely possible to bring all Russian war criminals to justice. Each of the collaborators’ (17). Zelenskyi therefore conveys that collaborators the same punishment as war criminals and soldiers, implying that the damage they have done to Ukraine comparable.