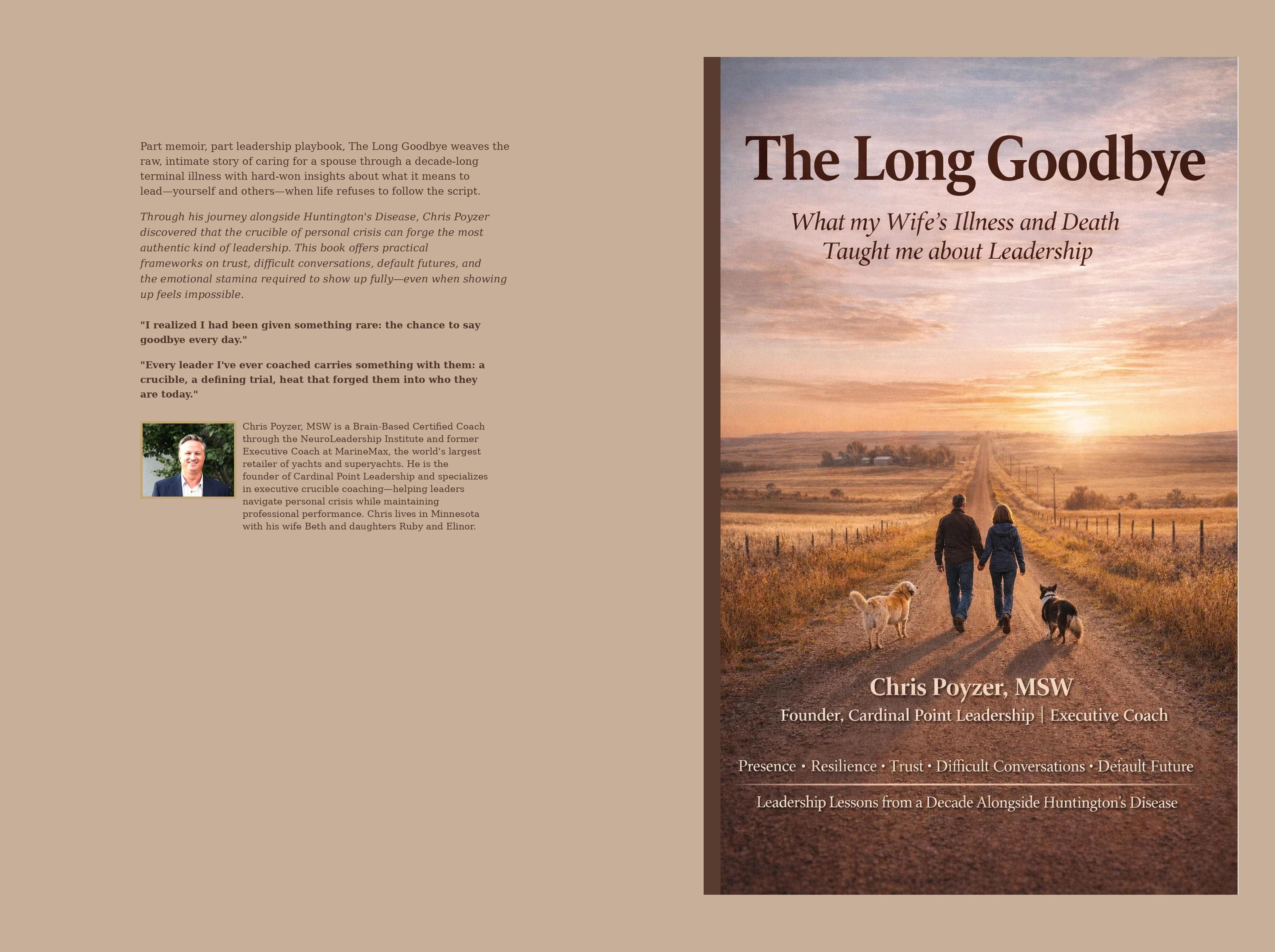

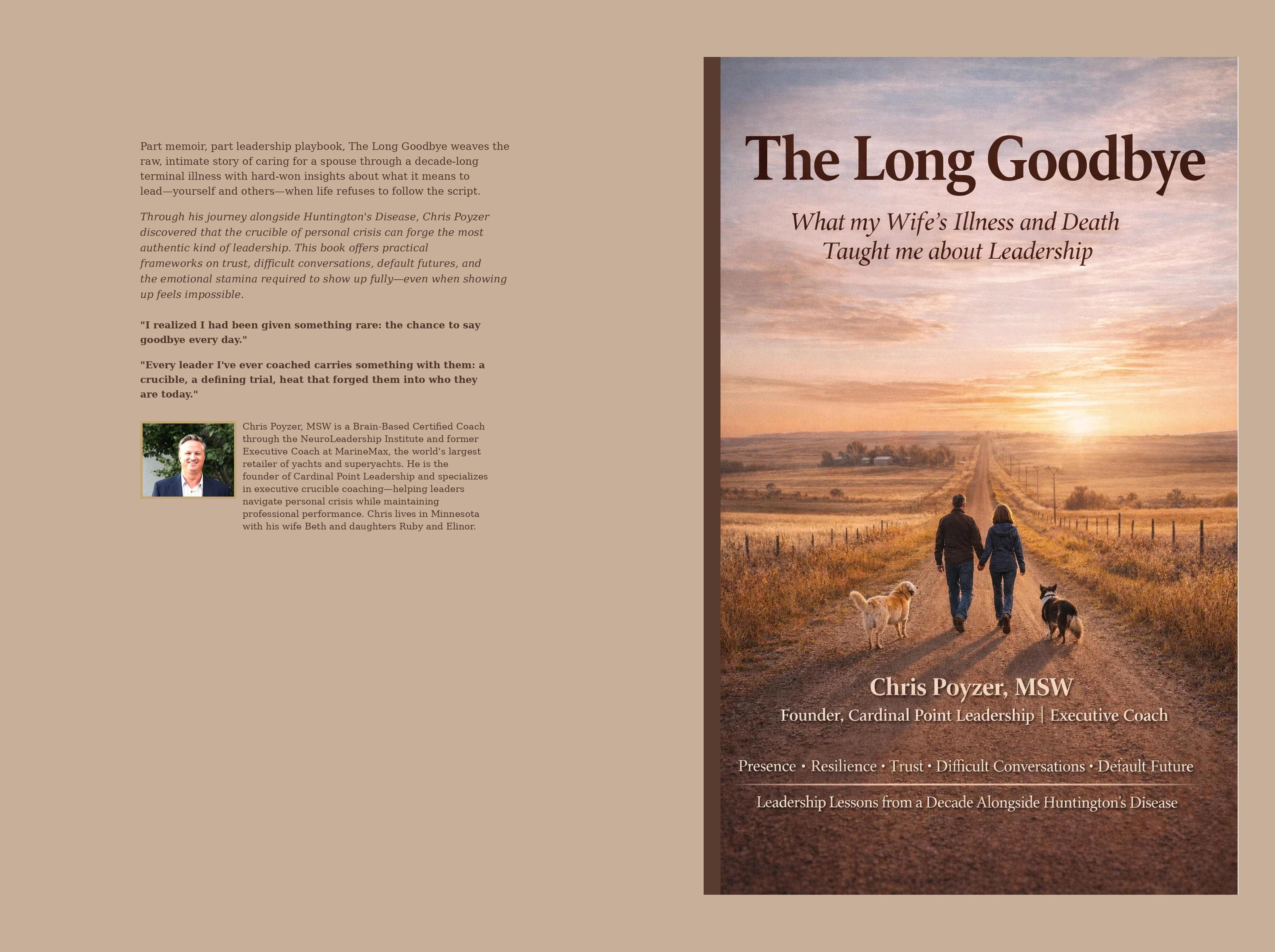

The Long Goodbye

What My Wife's Illness and Death Taught Me

About Leadership

Chris Poyzer, MSW Founder, Cardinal Point Leadership Executive Coach

Copyright © 2026 Chris Poyzer

All rights reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the author.

Published by Cardinal Point Leadership Salol, Minnesota

First Edition

Excerpts

"I realized I had been given something rare: the chance to say goodbye every day."

"Life is grief and joy happening simultaneously"

"The way we lead is shaped by the way we ' ve lived. Our crucibles become our credentials And the stories we ' re most afraid to tell are often the ones that need to be heard."

"What feels like instinct is often just an old ghost at the wheel"

"You don't become a leader by avoiding the fire. You become a leader by taming, channeling, and internalizing the fire"

"Never leave me, okay?"

"The most dangerous default future isn't a bad one. It is mediocre."

"She never complained. Not once. "

"Be careful. And be good to yourself."

"Your crucible isn't something to hide. It's something to integrate. The scar tissue becomes your credential."

Contents

Chapter 1. Introduction: Why This Book Is Different. A sunroom. A dog is watching me. The moment I realized I was going to lose her—and the decade that followed.

Chapter 2. Realization: The Gateway to Growth. What happens when you finally see.

Chapter 3. Crucibles of Leadership: Fires That Forge Leaders. Trials that break you open. Christmas Eve, 2009. Carrying her to the shower.

Chapter 4. Default Future: The Path You're Already On. The life you ' re drifting toward if nothing changes "Why the fuck did I spend seven years in a library getting a doctorate?"

Chapter 5. Trust Repair: Leading After the Break. That night, I left her at a wedding and the deep wound that I did not see "Never leave me, okay?"

Chapter 6. Difficult Conversations: The Words That Change Everything. A medical student with tears in his eyes. The question no one wanted me to ask. Pancakes. November 20th. "It's okay. It's okay."

Chapter 7. Resilience: What It Actually Looks Like When It's Real. She never complained. Not once. A thank you from a wheelchair: what many with leadership potential are missing.

Chapter 8. Be Good to Yourself: What Pressure Did & My Relationship with Alcohol. Crown Royal bags on the floor. A shattered mirror. The six words I've never forgotten.

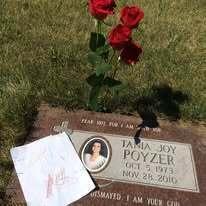

Chapter 9. Releasing: The Hidden Commitment That Keeps You Frozen in Place. The grave I couldn't find. The guilt of loving again. My second wife Beth with daughter Ruby pointing at the sky: "Ta Ta, up there."

Chapter 10. Epilogue: Still Here. A map of the Florida Keys on my wall. Tania's star. The neurologist's question was answered with one word. The long goodbye doesn't have a period

Chapter 1. Introduction: Why This Book Is Different

"Life is grief and joy happening simultaneously" Author Unknown

The Sunroom

One afternoon, I was sitting alone in our sunroom during the summer of 2000. Everything was still. Our dog sat nearby, watching me in the way animals do when they sense something heavy is happening before you can even put words to it.

My wife Tania was only twenty-seven when we first began to suspect something was wrong, Huntington's Disease There was no dramatic moment — no single sentence that landed fully formed. Just a growing awareness that something serious was unfolding, and it appeared to be moving quickly. I knew she had it, and I became more fully aware with each passing day that the clock was ticking on our time together.

Sitting in that sunroom, it hit me.

Not as panic, but as clarity: This was not going to be a single goodbye someday down the road This was going to be a long one. At first, that realization felt cruel. Awaiting death can be gruesome and devastating. Watching loss unfold slowly can feel unbearable. I was scared terrified and I realized that there would be little chance for do-overs. I had no choice but to accept that my time with her was limited, and I began to appreciate how critical my support would be to her. My reaction mattered deeply, there would be no grand gestures, no perfection, just presence, and love.

Over time, I realized I had been given something rare: the chance to say goodbye every day, forever I now realize that those last few years caring for my beloved better half permanently changed every aspect of my life, how I coach, how I parent, how I live, and especially how I feel about leadership.

How This Book Got Written

I've been encouraged to write my story for years. The Long Goodbye that's what I call it. The decade I spent loving Tania as Huntington's Disease slowly took her from me: caregiving, grief, guilt, and finally rebuilding The memories would come to me uninvited: intrusive moments — usually unwelcome, a song, a flash of her face. When they hit, I'd sit down at my computer and start typing, writing the memories down before they disappeared. Some things I just kept for me, for us.

Usually alone, often in the basement, or late at night when everyone was sleeping, I would type, text myself a thought, or email myself an idea for the book. Sometimes I tried to drown the pain in whiskey. Sometimes there were tears, sometimes giggles, often in the same sitting That's how grief works That's how memory works Life is full of grief and joy happening simultaneously — I tell my clients that all the time.

I learned it by living it. I've been writing pieces of this book for the last five years, here and there, in the margins, and was never quite ready to finish it. And then I started writing this leadership book, a playbook for my coaching clients. Frameworks, psychology, and practical tools the kind of thing you'd expect from an executive

coach. But somewhere along the way, something dawned on me: They weren't two separate books. They were the same book.

The Same Book

The topics I chose for this leadership playbook crucibles, resilience, trust repair, difficult conversations, restoration weren't random. They're the chapters of my life. The way I coach is inseparable from what I've lived. My perspective on leadership isn't a theory I learned in a classroom; it's scar tissue.

When I sit across from an executive or high performer who's carrying a lot of weight that no one else can see, I'm not guessing what that feels like. When I coach someone through a decision that has no good options, I'm not working from a textbook. When I help a leader find meaning in suffering, I'm drawing from a well that took a decade to dig. The Long Goodbye has become part of my DNA. It explains why I coach the way I do, why I parent the way I do, and why I see leadership as something that runs a lot deeper than strategy and performance. So, I made a choice: I would weave my story into one book, not two. This book is not about me, but it is an attempt to show you, the reader, who's sitting across from you, to see the coach, the person, behind the frameworks.

What You're Going to Experience

This book moves back and forth between my tragic experience and how I coped, sometimes more successfully than at other times. Occasionally, we need to come up for air because of the emotional arc of the story, which can become quite steep at times. You’ll read about leadership psychology — frameworks, research, and practical tools that you can apply, that’s the core. That's most of what you ' re looking at. But, woven throughout, you'll also find pieces of The Long Goodbye, moments from that decade, stories I've never spoken about with anyone. These experiences taught me invaluable life lessons which I now teach others.

When you come to the chapter on trust repair, you'll hear about the night at a wedding when Tania grabbed my arm and said, "Never leave me, okay," and what I learned about keeping nearly impossible promises under the most difficult circumstances. In the chapter on difficult conversations, you'll hear about the hardest conversation I 4

ever had, telling her family that I had decided to stop the feeding tube, saying goodbye. In the chapter on resilience, you'll hear about learning to survive one hour at a time because looking further ahead was too much to bear. The mash up is intentional. Leadership isn't abstract. It's lived. And the concepts sink deeper when they're grounded in something undeniably real.

I'm Scared to Tell This Story

"There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed."

— Ernest Hemingway

The words that follow can never fully capture the sadness of each moment or the peaks and valleys. Many of these moments I can barely speak about even now, fifteen years later. Words can't describe what we lived through. They can only point at it.

I wrote a poem as an undergraduate in creative writing right after I found out that she had Huntington's Disease. I can't remember the whole thing, but my professor said it was good. One verse has stayed with me for twenty-five years:

Beckon, beckon upon the roots of tongue, who exists, exists despite melancholy cries.

The roots of the tongue I told my professor that this poem was about the power of sensation. The tongue is sensitive, primal, and tied to survival. And the rest of it was what we were living: existing despite every urge to cry out in anger and anguish. We were still here. Still choosing to live. Despite everything calling us to collapse. That was what I was feeling then, after I found out that she had an incurable, deadly disease.

I also realized that leadership books should not be stale, like potato chips sitting in a bag too long; good, but not great: curriculums, checklists, frameworks without soul I didn't want to write another one of those. I wanted to write something that would hold your attention because it's true. Something that earns the right to teach you about resilience by showing you what resilience cost me. I do not just tell you how to have difficult conversations but also 5

provide illustrations from my own real-life experience, especially the hardest conversation I ever had.

This is a leadership book intertwined with a love story, a coaching playbook built on grief, restoration, and practical tools anchored in lived experience. You'll meet Tania. You'll meet Beth, my second wife who saved me. You'll meet Ruby and Elinor, my daughters who water the seeds of recovery every day. And through all of it, I hope you'll see what I've come to believe:

The way we lead is shaped by the way we've lived. Our crucibles become our credentials. And the stories we're most afraid to tell are often the ones that most need to be heard. This book is my attempt to tell my story and maybe help someone by doing so.

I hope it gives you permission to do the same.

Chris

Chapter 2: Realization: The Gateway to Growth

“Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life, and you will call it fate.”

Carl Jung

The Gateway to Growth

In leadership psychology, one of the most powerful turning points isn't a new strategy or a bold initiative it's realization the moment when unconscious patterns become conscious, when leaders finally see what has been driving their behavior beneath the surface not intellectually, but viscerally

For leaders, this isn't an abstract philosophy. It's a lived experience. Under pressure, executives often revert to default scripts written long before their current role. Family dynamics, early career experiences, past failures, and learned survival strategies often hide beneath polished résumés and confident boardroom performances. These scripts quietly shape how leaders respond to feedback, conflict, uncertainty, and stress.

Cardinal Point Nudge: "What feels like instinct is often just an old ghost at the wheel."

Realization is the disruption of that cycle. Neuroscience shows that once a pattern is noticed, a gap opens between stimulus and response the space where choice becomes possible. That gap is the difference between reacting out of habit and leading with intention. Through a psychological lens, realization isn't about shame it's about ownership. Leaders shift from asking, "Why am I like this?" to "What can I do with what I now see?" That shift is where growth accelerates; resilience begins, and authenticity deepens Before we go further, I want to connect this to something you already know.

Back to the Sunroom

Remember the sunroom experience I told you about in the Introduction? That was my moment Not a leadership seminar, nor a 360-degree assessment. A dog watching me in the stillness, and clarity arriving uninvited. This was going to be a long goodbye.

That realization that time was no longer open-ended changed how I thought and how I lived: not perfectly, not without stumbling, but with intent, with presence, cultivating an understanding that how I led myself through this would matter. I didn't know it then, but that sunroom moment was the beginning of everything I now teach, the patterns I help executives uncover, and the default scripts I help them to see The gap between stimulus and response is where choice becomes possible. I learned it first in grief. I now teach it in leadership. That's how the mash up works. Long Goodbye isn't separated from the leadership content it's the foundation. So, as we move through this chapter and this book know that the frameworks aren't abstract. They were forged in something real, something I lived before I ever named it.

Why This Matters for Leaders

Realization is never the end of the journey it's the gateway Imagine turning on a light in a room you ' ve lived in for years. The furniture hasn't moved, but suddenly you see where you ' ve been stumbling in the dark. Now you can rearrange, redesign, and move with intention. The leaders who create lasting impact aren't those who avoid mistakes. They're the ones who notice their patterns, own them, and make choices accordingly. Realization isn't about exposing weaknesses. It's about reclaiming strength. When you choose to see clearly, you choose to lead intentionally. That's where transformation begins.

The Hard Truth About Insight

Realization is a powerful moment. When the lights come on, you finally see the patterns the instincts, the reactions, the old scripts But insight alone doesn't create change. Here's the hard truth I see in coaching: the moment leaders realize what needs to change, they often freeze up. Not because they're weak, but because what needs to shift isn't just a strategy it's a survival pattern. And survival patterns don't let go easily. That's where the next part of the journey begins.

Growth doesn't come from piling on more tools. It comes from releasing what no longer fits. World-renowned coach Marshall Goldsmith put it best in the book I often recommend to clients: What Got You Here Won't Get You There. That one sentence holds a leadership truth we can't afford to ignore.

But before you turn the page, pause! If you feel stuck in the realizing phase.... if you ' re moving too fast...if this feels like too much or not quite enough: Stay Here! Slow down! Go back! Re-read! Talk through it with a coach or trusted advisor. Spend a few extra sessions right here. Because if you skip over this phase, you'll miss the core. And without the core, you'll end up chasing peripheral progress that doesn't stick. Realization is one of the most important stages of the coaching journey. So only move forward when you ' re truly ready.

Reflection

Sit with these questions!

● What behavior patterns can you see emerging when you are under pressure, especially those that you didn't consciously choose? You probably already recognize at least some of your own patterns The people around you do:

● Where did it come from? It protected you once. Is it still protecting you now? Or is it limiting you?

● What are you afraid to see clearly about yourself as a leader? The thing you ' re most defensive about?

Realization isn't the Destination. It's the Gateway.

"The first step is to become aware of what we are. " C.S. Lewis

Once you ' ve seen it, you can't forget it. The patterns become visible. The autopilot becomes obvious. The gap between who you are and who you have become starts to widen. Because seeing clearly is just the beginning. The harder question is: What made you this way? Not the résumé version. Not the polished leadership bio, but the real story. The moments that broke you open. The seasons that demanded everything and left you changed for better or for worse.

Every leader I've ever coached carries something with them: a crucible, a defining trial, heat that forged them into who they are today. Some wear it like a badge. Others bury it so deeply they've forgotten it's there. But it's always a script running in the background shaping decisions, filling in blind spots, and fueling the patterns you are just now beginning to see and understand. You can't lead forward until you understand what has and what continues to shape you. What's the crucible you ' ve been carrying?

Chapter 3: Crucibles of Leadership: Fires That Forge Leaders

"The crucible experience is a trial and a test that forces you to question who you are and what matters." — Warren Bennis & Robert Thomas

The Fires That Shape Us

In metallurgy, a crucible is a container that can withstand extreme heat the vessel where raw metal is melted and transformed into something stronger. The metal doesn't choose the fire, but what emerges from it is forever changed. Warren Bennis and Robert Thomas studied leaders across generations and found that the most effective ones had all passed through what they called ‘crucible experiences’ transformative trials that forced them to question everything they thought they knew about themselves. These weren't just hard times. They were identity-forging fires, moments that cracked open the old self and demanded that something new emerge. The death of a loved one, a devastating failure. a betrayal, an illness, a decision with no good options. The crucible isn't the event itself it's what happens inside you when you ' re put through the fire.

Cardinal Point Nudge: "You don't become a leader by avoiding the fire." You become a leader by what you discover inside as a result of the fire."

What Crucibles Reveal

Bennis and Thomas found that crucible experiences share certain common elements:

1 They force deep self-reflection You can't coast through a crucible. It demands you look at yourself honestly — often for the first time.

2. They challenge your existing identity. The person who enters the crucible is not the same person who exits from it on the other side. Something must die for something new to be born.

3. They require meaning making. The crucible doesn't give you a lesson. You must extract it. The same fire can forge wisdom in one person and bitterness in another.

4. They become part of your leadership DNA. The leaders who integrate their crucibles lead differently. They have a depth that can't be taught in a seminar.

5. The crucible doesn't make you a better leader automatically. But it does create the conditions for transformation — if you ' re willing to do the work.

My Crucible

"What is to give light must endure burning." Viktor Frankl

You already know about the sunroom. The dog is watching. The clarity that arrived uninvited. But the crucible wasn't that single afternoon. The crucible was the decade that followed. After the realization that this was going to be A Long Goodbye — I had choices. I could collapse under the weight of anticipatory grief. And yes, I had moments of collapse. I could spend the next ten years bracing for impact, or I could reframe what I'd been given. That was the crucible not one moment, but a decade of them. What got me through it was consistently choosing presence over despair.

Why This Matters for Leaders

Every leader I coach has had some kind of crucible experience. Some have named it. Most haven't. But it's there— shaping how they respond to pressure, how they treat people, what they're afraid of, and what they're drawn to.

The most successful leaders are those who've integrated their crucibles. They have depth. There's something beneath the surface that people can sense even if they can't name it. They don't panic easily. Once you have been through a real and transformative fire, the quarterly report doesn't shake you up in the same way.

Successful leaders lead with empathy. They know what it's like to carry weight no one else sees, and they can recognize it in others. They value presence over performance. They've learned that showing up really showing up is attainable, while perfection is

not. They have made peace with impermanence. They know that everything ends and how knowledge changes the way they invest their time and attention. The crucible doesn't guarantee any of this, but it does create the raw material. The question is: what will you forge from the experience of the crucible?

Cardinal Point Nudge: "Your crucible isn't something to hide. It's something to integrate. The scar tissue becomes your credential."

The Work That Follows

Some leaders try to bury their crucibles. They compartmentalize, build walls, and feign strength while carrying around unprocessed weight. That approach has a cost. The unintegrated crucible leaks out sideways in reactivity, rigidity, and disconnection. The thing you have failed to face up to, and the process becomes what runs you, ruining many.

Other leaders do the opposite. They integrate. They find language to describe what happened. They extract meaning from the experience and refine it, letting the experience inform their leadership style without allowing it to define who they are. Integration doesn't mean talking about it constantly. It doesn't mean wearing your wounds on your sleeve. It means you ' ve done the internal work. You've faced what happened. You've found a way to carry it forward that doesn't crush you. That's the work. And it's ongoing.

Reflection

Ponder the following questions!

● What is a crucible experience you ' ve survived? Name it!

● How has it shaped you in ways nobody else sees?

● What did it cost you?

● What did it teach you?

● Have you integrated that crucible or are you still carrying it around unprocessed?

Chapter 4: Default Future: The Path You're

Already On

"The best way to predict your future is to create it " Peter Drucker

December 2000. Tania and I were shopping for Christmas presents for our nieces and nephew. She looked beautiful glowing, happy, wearing a black and white tweed coat. Not the cheap thrift store version from when we were struggling students. Now she is a pharmacist. She had arrived. My childhood friend Cooter used to tease her that she looked like Jackie O in that coat with her dark shades. I agreed but found it even more stunning than Cooter, becoming acutely aware of how I had outkicked my coverage.

I Realized I had to Tell Her

The involuntary ticks and subtle personality changes. Everything was pointing toward Huntington's Disease. One problem with early symptoms is that they're involuntary like blinking. You don't notice them yourself until someone points them out.

I don't remember how many days I sat in that sunroom staring at nothing. Tears rolling down my cheeks one by one, knowing what I had to tell her. It wasn't for a few days. It was weeks, maybe longer. Just sitting there with the weight of it, trying to figure out how you tell the person you love most in the world that she's dying.

During that time, I also went back to college to study psychology and social work. I couldn't focus. I couldn't sleep. Looking back, surprisingly, I did not seek refuge as before in drinking. My grades were slipping. I was getting a C in Intro to Psychology my favorite class I came close to dropping out. I had one day when I decided I was going to become a train conductor. To hell with college. Just one day. But it was real. Looking back now, it's kind of funny. At the time, it wasn't. There's no manual to follow for this, no right moment, no perfect words. You just reach a point where carrying it alone becomes heavier than saying it out loud. That's how I finally found the courage to tell her.

What Huntington’s Takes

If you don't know what Huntington's Disease is, consider yourself fortunate It's an aggressive, progressive, neuro-degenerative brain disease. Mitochondrial cells begin shutting down, creating widespread brain damage. They control your movement, your cognition, and eventually everything. Life expectancy after symptoms appeared was twelve to fifteen years. No cure, almost no treatment. Nothing to slow it down. Just the clock ticking.

And it's genetic. If one of your parents has it, you have a 50/50 chance. If you have the gene, you will get the disease. Not if, but when. The average age of onset was in one ’ s forties. But as the neurologist told us, that's just an average some people don't show symptoms until their eighties; some get juvenile HD as children. And because the disease is rare, the sample size is small. The numbers don't tell you much. Tania was twenty-seven when it arrived.

I'd call it a psychological landmine because of the confusion and disorientation it generates. It forces one to realize what is happening. We knew, or at least heavily suspected, that Huntington's might be down the road. But we weren't prepared for it to arrive so soon. Watching someone you love disappear slowly is like watching a magician You know it's a trick You know it isn't possible But you can't figure out how it is happening. One day she laughed, and I forgot she was dying. The next day, she couldn’t swallow, and I can't remember what her voice sounded like before.

My mind kept playing tricks on me, letting me believe, just for a moment, that this wasn't real. That I'd wake up. That the woman I married was still there somewhere, waiting to come back. I wanted so badly for it not to be real.

Here's what they don't tell you about Huntington's: it doesn't just take the person. It takes your sanity, too. Your ability to observe clearly. It messes you up, destroying your ability to cope. It takes away your memories of who the person you loved used to be replacing them with who they are now, until you must fight to remember what they were like before. I used to come home, and she'd run and jump on my lap, giggling. That was her thing. That stopped.

We used to lie in bed laughing until we cried. That was normal. Then that stopped, too. Huntington's took away the laughter, our ability to laugh. It robbed us of the moments that made us, one by one, until I couldn't even remember the sound of her laughter. It took away our dreams of adopting or having our own children. The life we had always imagined together was gone before we could build it.

It pushed our friends away. Not because they didn't care, but because they didn't know what to say. Because watching us was too hard. Because life moves on, while ours stopped. The decade wasn't one long grief I could adjust to. It was a thousand small robberies. Each one took something I didn't know could be taken. Writing this, after she has been gone for fifteen years, I realize better now how much it took from us. At the time, we pushed it to the side. Leaned into each other. Future fed, one hour at a time. That's how you survive something like this. You don't look at the whole thing. You can't. You just take the next hour. And then the next.

Back to More About Huntington’s Disease

Tania knew these odds better than anyone. She had watched her grandfather die from HD Her father was turning the corner into his own decline, rounding third base. She had lost an uncle to HD and a cousin to juvenile HD, the cruelest version, the one that takes children. Her family had already been carved hollow by this disease.

As I write this in 2025, the disease is still killing.

Earlier this spring, Tania's brother, Todd, lost his battle with HD, leaving behind a wife and two amazing teenage boys. Tania's mother Char—the woman who held her family together through decades of loss has now buried her husband and all her children. All to the same disease. Some families are asked to carry weight that defies explanation. The only response I know is to witness it. To refuse to look away.

I Can Only Imagine

But back to that moment. The tweed coat. The dark shades. The glow of a woman who had finally arrived Christmas presents are in the back seat. Tania is beside me, happy, unaware. And I struggled under the weight of what I had to say.

I had spent months in a haze of sadness, struggling to accept what I was seeing. Knowing that my Tania was not going to be around in twelve to fifteen years. And I knew something else: the younger the symptoms appear, the faster the disease progresses. The mutations accelerate. Twelve to fifteen wasn't going to be our window. I did the math and I knew I had at best ten years with her. I got seven.

That night, driving home on a frigid Minnesota road with Christmas presents in the back, I pulled over. Of course, she was playing "I Can Only Imagine” the MercyMe song she always turned to. It was her go-to, especially during Christmas or times of sadness. She'd play it repeatedly on the DVD player.

Seven years later, on November 28, 2010, a local musician played it on the piano and sang it at her funeral in the same church where we had stood hand in hand thirteen years before and made our commitments to each other

I turned to her and said we needed to talk. Beyond words.

No Ideal Backdrop

There's no ideal backdrop for that conversation. I told her what I had been witnessing. At first, she laughed, thinking I was kidding. Then she saw my face. She sat there in silence. Tears started to fall and she looked out the side window. Then she turned around and fell into my arms. We held each other I don't know how long we sat there. We just cried. Her tears mixed with mine, and we became one. Then she shook her head in anger with a strong potency of disgust–and said the only swear word I ever heard from that sweet angel:

"Why the fuck did I spend seven years in a library getting a doctorate? I haven't even traveled. I haven't seen the Grand Canyon or the Eiffel Tower. Now it's too late."

I stopped her and said: "That's not who you are. From the day I met you, you never let Huntington's define you or your dad or your family. You never let it dictate your life. That's not the woman I know." I need to come up for air. And maybe you do too. That's the thing about revisiting these memories it's cathartic, yes, but it's still a lot to swallow. Even now, twenty-five years later.

Even now, writing it down, remembering, and reliving, I still cry as I reflect on it. I still grieve when I allow myself to remember. Still moments of flashbulb sadness. And then I look up. Ruby and Elinor are giggling, jumping on each other loudly and happily, oblivious to the sound they are making, tickling my feet as they walk by, saying I love you Daddy. My angels. Gifts from God, maybe I'm not that religious, but I don't know what else to call them. Beth is on them to get to their homework. My dogs are at my feet, of course. Now cats too. Life is good.

I have so much to be thankful for. Grief doesn't cancel gratitude. But neither gratitude nor happiness cancel grief. We all have our stories. And if you ' re still reading, this may be resonating with you at some level. Maybe you ' ve carried around something you didn't know how to say. Maybe you ' ve sat in your own version of that sunroom, staring at nothing, wondering how to move forward.

Maybe you're in it right now. I think that's why I wanted to weave this story through a leadership book instead of writing it alone. The back and forth from Tania to frameworks, from grief to growth lets me breathe, you too. So, let's breathe! Let's talk about what this means for how you lead.

Two Futures

Most people, especially leaders, have two futures: the one they daydream about, and the one they're already living. The second one, your default future, is the life and leadership you will wake up to twelve months from now if nothing changes. It isn't a prediction. It's a trajectory. It's the silent outcome of your current habits, your internal stories, the assumptions you hold, and the fears that you either face up to or continue to avoid.

In psychology, we call this a self-reinforcing loop. Our brains are wired for efficiency we run habits and narratives on autopilot to save energy. But autopilot comes at a cost: it drives you towards outcomes you never consciously chose. Without disruption, you drift into a future shaped by your past. The good news? You can interrupt this loop. You can rewrite the language that shapes how you see life itself. You can generate a future that pulls you forward instead of holding you back.

Cardinal Point Nudge:

Your default future is what happens when you don't consciously choose. It's not bad; it's just unexamined.

But here's what most leadership books won't tell you: sometimes the default future isn't about drift at all. Sometimes it arrives uninvited a diagnosis, a loss, a reality that rewrites your trajectory whether you ' re ready or not. That's what happened that day in the car. Not because I drifted into it. But because it found me. Even then, you have a choice. Not about what's coming, but about how you will meet it. You can keep ducking it, or you can meet it head on.

One Shot

Years later, when the girls were still little, and when I knew I wanted to make the switch from counseling and mental health to organizational psychology and executive coaching, I enrolled at the University of Missouri. One of the books on our curriculum stopped me in my tracks: The Three Laws of Performance by Steve Zaffron and Dave Logan. It's still my favorite. Not because it's the most comprehensive leadership book I've ever read, but because it spoke directly about what I lived through with Tania. The way language shapes reality tends to lead us into futures that we never consciously choose The way a single conversation can rewrite everything That's why I chose this framework. That's why I'm weaving it throughout this book.

The Three Laws of Performance

Zaffron and Logan's groundbreaking work revealed something profound about how change happens:

Law 1: How people perform correlates to how situations appear to them. Two leaders can face the same market downturn. One sees it as a catastrophe and freezes. The other sees it as a reset and moves on, seizing opportunities. The same situation leads to different perceptions of the challenge and different types and levels of response and performance.

Law 2: Situations arise in language. The way you talk about your challenges shapes how they show up for you and the extent to which you are able to resolve or overcome them "This team is impossible" creates a different reality than "This team hasn't found its footing yet." The words aren't just descriptions; they're blueprints.

Law 3: Future-based language transforms how situations occur to people.

When Tania said, "Now it's too late," she was living in a future of loss. When I reminded her who she'd always been someone who never let Huntington's dictate her path it opened a different future. Not a future without the disease but a future where she still had agency, despite the disease. What does this mean for your leadership? Simply put: The way you describe your situation IS your situation.

The language you use doesn't just describe reality: it creates it. If you keep describing your challenges the same way you have been… If you keep telling the same stories about why things are the way they are... If you keep using the same language in your head and with your people… You will keep living in the same future.

What Huntington’s Couldn't Take

One of my favorite coaching exercises is simple: If you want a different outcome, tell yourself a different story. I tried to do this as much as I could during the long goodbye. By no means was it constant; grief doesn't work that way. But it allowed us not to be bullied by this disease. It helped us to avoid the negative talk that could have consumed every conversation. We always made sure that Huntington's would not get between us. The disease was going to take what it was going to take. But it wasn't going to take us not who we were to each other at least without a fight. That's the power of the story you tell yourself. It doesn't change the facts. It changes what you ' re able to do, despite the facts.

How You Meet It: The cost of a default future isn't missing goals. It is a missed life. It's arriving somewhere you never chose and realizing you can't get the years back. Tania didn't have the luxury of drift the disease made every day a conscious choice. Most of us do have that luxury. Often, however, we waste it.

Cardinal Point Nudge: The most dangerous default future isn't a bad one; it's a mediocre one.

Dreams Deferred

In that frozen car, Tania's first response was to grieve the default future she'd lost Seven years of studying in a small room in the library. Her mind raced to everything that would now be taken from her. That's what default future thinking does when it turns dark. It shows you only what's disappearing, and it can lock you into the story of what you'll never have. But Tania didn't stay there. She never had.

Her whole life, she'd refused to let Huntington’s write her story, watching it as it took away her father, knowing the odds, and still building a life of purpose and joy.

That conversation in the car wasn't the end, but rather a test of her agency. She chose how she would meet what was coming Not with denial, or with despair, but with presence and grace.

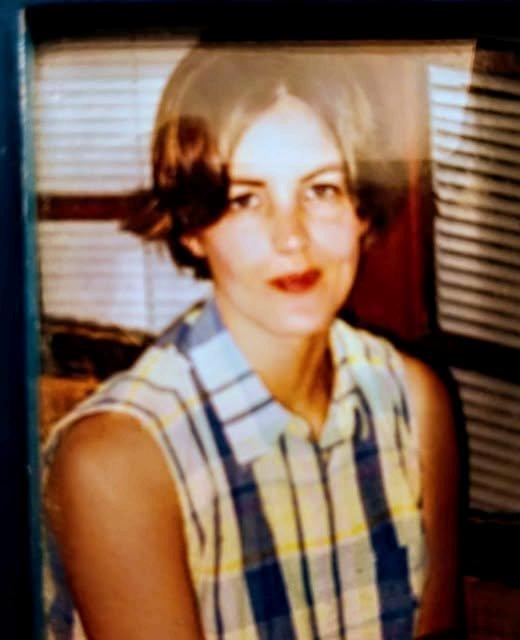

(Dr. Tania Poyzer NDSU, Graduation 1999)

For leaders, this has a special meaning. One can redirect some of the default futures through which one navigates, but some of them, you can't. The question isn't always "how do I change this trajectory?" Sometimes the question is "how do I meet this trajectory with intention instead of resignation?"

That's the deeper work of leadership. Not just steering toward better outcomes when you can but showing up fully even when the outcome isn't yours to control.

Cardinal Point Nudge:

The Future that Awaits You

So, breathe! Picture the future that currently awaits you; if nothing changes, where will you be in twelve months? What will your team look like? What relationships will have eroded? And which ones will blossom? What opportunities will have passed?

Now picture the future you truly want. What kind of leader do you want to be known as? What kind of relationships do you want to build? What kind of team culture do you want to create? And what kind of legacy do you want to leave behind? What's the gap? And what would it take to close it?

That's the invitation Not pretending you control everything but refusing to let autopilot drive when you are still at the wheel. Your default future is waiting. So is the one you could choose instead of the default. The choice is yours.

Reflection

Sit with these questions:

● If I keep leading exactly as I am now, where will I be in 12 months?

● What is the default future I'm currently heading for—the one I haven't consciously chosen?

● What language am I using that may keep me stuck in that trajectory?

● What declaration could I make that might empower me to begin rewriting my future?

Chapter 5: Trust Repair: Leading After the Break

“It takes 20 years to build a reputation and five minutes to ruin it.”— Warren Buffett

None of this works without trust. You can understand how situations occur to you. You can learn how language shapes reality. You can choose presence over autopilot, intention over drift. But if trust isn't there—in yourself, the people beside you—it can matter very little.

A couple can't meet a default future together if you ' re not sure the other person will stay, someone you can trust. I tell coaching clients that trust is like the tides in Florida. It generally rises and recedes predictably, like clockwork. But sometimes they rise and fall just because. You can't always explain it. You just learn to read it and to respect that it's always moving.

Hemingway writing from Key West, the same place Tania told me I should return to someday said it simply:

"The best way to find out if you can trust somebody is to trust them."

The Keys keep showing up in this story. So does trust. Maybe that's not a coincidence. I always trusted Tania. And she trusted me. We built that foundation early through communication, absolute commitment and never failing to show up when it most mattered. Honestly, it wasn't that hard. Some relationships require constant maintenance. Ours not so much. Ours just...held. Trust was the one thing, until the very end, that remained pure and constant. The disease took her movement, her speech, her independence, but could not take away our love and devotion to each other.

But that trust didn't appear out of nowhere. It was forged in a moment I'm not proud of a night early in our engagement when I made a mistake that could have derailed our wedding plans. Looking back through her eyes now, I bet she was thinking. What the hell? Is this your modus operandi now? Every time you ' re uncomfortable, you just bail? That mistake and its resolution became part of the foundation for everything that followed.

The Promise

July 1996. Tania and I had been engaged for just a few months. We were at her cousin's wedding back in her hometown with a sea of relatives, most of whom I had never met, small talk I didn't want to make, and a mood I couldn't explain. I was grumpy, and not for any good reason. I'm normally a social person but something about that day had me wanting to retreat. After a couple of beers, I told Tania I was ready to leave and head back to her parents' farm. She wanted to stay. Looking back, maybe if I'd switched from beer to Crown Royal, I would've stayed put. You'll see later the role Crown played in this long goodbye. I pushed. She pushed back. Then I did something I'm not proud of: I left. Not a dramatic exit; I just walked away, got in the car, and drove back to the farm. I lay on the couch and watched TV, not thinking much about it.

Until the front door burst open and I saw her. You know that scene in My Cousin Vinny where Marisa Tomei goes off? Arms flying, finger pointing, full Italian storm? That was Tania that night. A quiet farm girl from North Dakota pushing me in the chest, furious, hurt, terrified. A version of her I'd never seen or even knew existed.

"You left me! You LEFT me!"

I started to defend myself, explain, justify, trying to make sure she understood why I'd left, that it wasn't a big deal, that I was just tired and needed some space, but something in her voice stopped me. This wasn't about the wedding. This wasn't about a twenty-minute drive to the farm. Nor was it about me being grumpy at a family gathering. This was about Huntington's Disease.

The Fear She Carried

Her father was declining at this point She was watching the disease take him slowly, piece by piece—and she knew there was a coin flip chance she'd face the same fate. The previous summer, she attended her younger cousin Daman’s funeral. He had lost his battle with Huntington's. So, this wasn't abstract for her. It wasn't a statistic or even a maybe. It was all too real. She had seen what the disease did and can do. She had buried family because of it.

She also knew—because she'd seen it in other families—that partners leave. When things get hard, when the disease takes hold, when caregiving becomes relentless...people often leave. And I had just left her at a family gathering because I was in a bad mood. In that moment, every fear she carried with her about love, loss, and abandonment came flooding in. My thoughtless exit had cracked something wide open.

Researchers who study trust talk about the difference between the visible offense and the deeper wound. I thought I'd broken a social contract—you didn’t ditch your fiancée at a wedding. But it was more than that, I'd broken her sense of safety. Her belief that I would stay. That's the part most people miss when trust breaks. The surface issue is rarely the real issue. What's underneath is what matters.

"We suffer more often in imagination than in reality." Seneca

We fought. We cried. At some point, I heard her dad downstairs, laughing by himself. This was a man already having trouble walking and talking; Huntington's was taking him away piece by piece. But he heard his daughter fighting with her fiancé over a dumb exit from a wedding, and he wasn't worried. He chuckled. He knew we'd be fine. He was right.

Then she looked at me and said something I've never forgotten. Holding my hands in hers. "Never leave me, okay?" It was not a demand but a plea, coming from the deepest place inside her. I told her I wouldn't. I told her nothing would tear me away. I made a promise. So, here's the thing about trust repair: the words are just the door. The actions are what repeatedly walk through it.

Promise Kept

I kept the promise. Through fourteen years. Through diagnosis, the progression of the disease, and living in a nursing home for over a year. Through the feeding tube. Through the decision to let her go. I never left. It never crossed my mind to leave, and I would do it all over again. But that promise only meant something because of what happened that July day. Because I understood what my carelessness had cost her. Because I saw the wound I'd opened—not the surface wound, but the deeper one. And because instead of defending myself. I chose to repair the damage.

Actions Not Words

The trust repair didn't happen in a single conversation, but over the years. Every time I proved with action what I'd promised with words. That's how trust repair works. It's not a conversation, but more like a campaign.

Every leader will break trust at some point. Maybe not dramatically but in small ways that accumulate. A promise you couldn't keep. A meeting you missed. A decision that blindsided someone who deserved a heads up. A moment when you prioritized something else over someone who was counting on you. The question isn't whether you'll break trust. It's what you'll do after that.

Many, if not, most leaders resist repair because it requires vulnerability You must acknowledge that you failed, that you hurt someone, that you weren't who you wanted to be. So instead, they minimize:" It wasn't that big a deal." They deflect: "You're overreacting." They justify: "I had no choice." They disappear hoping time will heal what they're unwilling to address. None of it works. The wound festers. The distance grows. And the relationship becomes a shell of what it was before trust was violated.

My instinct that July night was to explain. To contextualize. To make sure Tania understood why I'd left. None of that helped. What she needed was acknowledgment that what I did hurt her period No, "but." No, "because." Just: "I did this and it hurt you. I see that now. " Leaders who rush to explain are signaling that their reputation matters more than the relationship.

Stronger than before

"Never leave me, okay?"

That wasn't a casual commitment. It was a covenant. I made it knowing the road ahead or at least suspecting it. If you ' re going to promise something in the wake of a trust break, mean it. Understand that you ' re now accountable to prove it with action. Broken promises on top of broken trust don't just fail to repair; they make repair impossible.

Research on trust repair shows something counterintuitive: a repaired bond can be stronger than the original. That fight in July might not have ended our relationship; it might have just delayed the wedding, Instead, it deepened us. Tania knew—because she'd tested it, accidentally that I would stay. That knowledge was worth more than naive trust ever could be. You've seen this in organizations too. The leader who breaks trust and then spends years rebuilding it through consistent action that leader often earns more loyalty than the one who never stumbled. Because now people know what you ' re made of. They've got to know you better because of the repair. They've watched you face up to discomfort instead of running from it.

The Good Ones

I didn't repair Tania's trust with apologies. I repaired it by showing up. Day after day. Year after year. Looking back, that July night was one of the best things that happened to us. It taught me what she needed. It taught me what I was capable of. It taught me that a repaired bond can be stronger than the original because now she knew. She'd tested it. And I'd stayed.

The leaders I work with the good ones they've all had their version of that night. The break that became the foundation. But here's what separates them from the rest: they learn from it, they don't keep making the same mistake. The best leaders I coach aren't just good at repairing trust. They stop breaking it in the first place. They show up before they must. They communicate before it's urgent. They care about your interests not just their own.

Researchers call this benevolence. I just call it giving a damn. What's yours? What break became your foundation? And what did it teach you about who you want to be?

Reflection:

● Where have I broken trust not the surface issue, but the deeper wound?

● What would acknowledgment look like without defense?

Chapter 6: Difficult Conversations: The Words That Change Everything

"It's okay It's okay"

The first time, I was weeping in her lap in the hospital, fighting for more time. The second time, I was lying beside her in the nursing home, letting go. Both times, she was comforting me. She was giving me permission to fight, and then to stop fighting. The decade of Tania's illness taught me something about difficult conversations that no leadership book ever could: sometimes they don't stop. They accumulate. You don't get to have one hard conversation and move on. You must keep having them with doctors, with family, with yourself Each one requires something different.

Each one changes you. Every leader knows the feeling. There's something that needs to be said and you ' ve been avoiding it. Maybe it's feedback that will hurt. Maybe it's news that will be devastating. Maybe it's a decision that will change everything. We tell ourselves we ' re being kind by waiting. Finding the right moment, preparing our words carefully. But usually, we're just afraid. Researchers call it the MUM effect, the reluctance to deliver bad news. We delay. We distort We delegate And the longer we wait, the worse it gets Trust erodes. Resentment builds. The gap between what we know and what we ' ve said becomes a chasm that's harder to cross with every passing day. I didn't have the luxury of waiting. The disease sets the clock. And so, I learned to have conversations, not because I was brave, but because there was no other choice.

We were in the inpatient hospital for the second time in the same week. She was declining physically, cognitively, emotionally, and not eating. Things were not looking good. I walked into the room and found our main doctor, Dinesh Bande, with a medical student This future doctor, I wish I remembered his name, was talking to Tania. She was smiling, even giggling. He was super sweet. I said, "Hey honey." He smiled and walked away.

She looked at me and said, "I like him." She was blushing. Of course, he was tall, young, and handsome. I said, "Hey, wait a minute." She giggled. Even then, declining, dying, she still made me laugh.

A few days later, the whole medical team came in. The main doctor. His students. Tall and Handsome too. I could tell immediately what this was. They were prepared gentle, mindful, and reading the room. Soft voices. Attentive. They were here to have the conversation, mostly with me. This was it. Nothing more they could do. End stage. Time to consider a nursing home. Tania was half asleep, not really listening. I nodded with my consent. It was emotional. I could tell the whole team had fallen in love with her amazed by her resilience, how she never complained, and how she said thank you to every nurse, every aide, and every student who walked through that door

Still sweet. Even now. End Stage. I was already ahead of them. That morning, I'd been on the phone with hospice. Looking at nursing homes, making lists, I knew where this was going. In the middle of the doctor's words, I looked up. Tall and Handsome was in the back of the room, head down, with tears in his eyes. Trying not to be seen. I smiled at him, nodding. Then I thanked the doctor. I thanked all of them for everything. I told them we got it. I got it. This was the final lap. They were prepared for denial, rebuttal, or nothing at all—that happens too

They weren't prepared for acceptance. It was a master class in difficult conversations. Not just how to deliver one but how to receive one. And I've thought about it many times since. The way Dr. Bande led that room. The way his students watched and learned. The way you could feel respect in the silence. That's why he leads intern education at UND now. Because he knows that medicine isn't just science. It's presence.

But I wasn't done fighting. A few weeks later, she was back in the hospital. Worse this time. Unable to eat. Unable to maintain weight. She was starting to aspirate, slipping further each week. Her body was giving out. We sat in the room, me, Tania, and her mother. The neurologist stood in front of us and confirmed what Dr. Bande's team had told us: end stage. I looked at Tania. I wasn't even sure she was listening anymore. Her mother was there and I understand it differently now that I'm a parent myself. She didn't want her daughter to suffer.

But I remembered what Tania had told me years before, when we'd talked about what she wanted if things got hard. She said: "Just be smart." So, I asked the neurologist about a feeding tube, a gastric tube they could put in her stomach. She couldn't swallow anymore. She'd been severely constipated and backed up and I'd noticed over the years that her ability to swallow was always connected to that. Maybe if we could get nutrition into her another way, give her system a chance to stabilize... I felt the silence in the room. The quiet judgment. This guy is in denial. He's looking for a miracle. Maybe I was But I wasn't ready to stop fighting I just wanted to have the conversation, ask the question that everyone else had already decided wasn't worth asking. We proceeded. It was my decision. I owned it.

“It's Okay. It’s Okay.”

That night, I looked at her thin, bones visible, IVs dripping, the sound of machines filling the silence. In the dark. I wept in her lap. All the fear and exhaustion, and grief I'd been holding came flooding out. And she even then, I thought she was sound asleep, even in that state gently patted my head and said: "It's okay. It's okay." Like she always did. Comforting me, even when she was the one who most needed comfort.

There's research on this on how we often misjudge the outcomes of hard conversations, expecting far worse than what happens. We brace for rejection and receive grace. We prepare for a fight and find understanding. But you don't need the research to know it's true. You just need to have been in a room where you expected judgment and received love instead.

The next morning, they put it in the gastric tube. And then something happened that no one expected. After getting fluids and nutrition through the gastric tube, her system finally had a chance to stabilize the color came back to her face. I woke up the next morning to her voice: "I'm hungry. Pancakes." I ran down the hall, literally ran, and found some pancakes and chopped them up small enough for her to manage. She ate them all. She was sitting on the edge of the bed, sitting up—when the neurologist came back on his rounds. Tania smiled and said hi. The neurologist was shocked.

That gastric feeding tube—the decision everyone thought was denial gave us a year. We transitioned to the nursing home. She restored some weight. We celebrated Thanksgiving, Christmas, my birthday, then one more birthday for her, one more Easter.

A whole year of memories that almost didn't happen because I decided to ask the question no one else wanted to ask. Sometimes, one must fight for a difficult conversation, advocating for what you believe is right, even when everyone in the room has already decided against it. Even when you can feel the silence pushing back against you.

I've thrown a lot at you. And honestly, this is hard for me too. Every time I write about this, I'm back in that hospital room, the nursing home, back in the silence between decisions. So, let's come up for air. If you ’ re a leader reading this, you might be wondering what feeding tubes and neurologists have to do with your quarterly reviews, your struggling team members, or the conversation you ' ve been putting off with your board, everything. The mechanics are similar. There's something that needs to be said. There's fear about saying it. There's a room full of people who've already made up their minds or who are waiting for someone else to go first. And there's you, struggling to decide whether to ask the question anyway.

Most leadership conversations aren't about life and death. But they often feel that way. The stakes feel enormous your reputation, the relationship, the fallout. And so, we wait. We prepare. We find reasons for the delay. Psychologists call it the avoidance cycle. We avoid something uncomfortable; we feel relief, and the relief reinforces avoidance. Next time, we will avoid it again. And again. What we are avoiding grows a little bigger in our minds, and a little scarier. The loop tightens.

I wanted to hide so many times during those years. Bury my head. Avoid the conversations, the people, and the reality of what was happening. That's normal, human. The brain is wired to move away from threat and difficult conversations register as threat, even when they're not life or death. But here's what avoidance costs: the conversation you ' re not having is still running in the background, taking up space, while trust erodes silently. The thing you haven't said is paying rent in your head.

What I learned in those hospital rooms is that the waiting is almost always worse than the conversation. Fear is almost always bigger than reality. And the grace that shows up when you finally say what needs to be said is almost always more than you expected. So, yes, my conversations were about feeding tubes and hospice and letting go. Yours might be about performance or direction or a relationship that's gone sideways. The content is different. The courage that is required is the same

Letting Go

November 20, 2010.

A year after the pancakes, a year of borrowed time. The disease continued its march. Tania could no longer speak much or barely recognize or respond to most people. The feeding tube that had given us a year was now just keeping her body functioning while the rest of her slipped away.

Then, I made the hardest decision I'll hopefully ever have to make: to stop all treatment and let her go. I spent the day before just lying with her in her bed at the nursing home. Our yellow Lab Darby knew something was wrong and lay on the bed with us she always knew. I kept saying "I love you " . I tried not to cry too much, but she saw. And then—even now, this breaks me—she looked at me and said:

"It's

okay. It's okay."

The same words, one year apart. At the beginning of the feeding tube journey and at the end. She was still comforting me, even then. I told people it was like swallowing glass to make that decision, even though I knew it was right. Even though I'd fought for every day we had. Even though the year of pancakes, holidays, and memories was a gift I'd never trade for anything. I was still the one who had to decide. I was the one who had to say the words. I was the one who had to bear the weight of my choice. Today, many years later, that weight is still with me. Not because I made the wrong choice; I didn't. But because some decisions become part of who you are. You carry them forward into everything that comes after.

I tell you these stories not because your difficult conversations will be like mine. They won't be. God willing, nothing you face will require these kinds of decisions. But here's what the decade taught me: Sometimes, a difficult conversation is the one you must fight for, to ask the question everyone else has given up on, advocating for what you believe is right, even when everyone in the room has already decided otherwise. Sometimes, a difficult conversation is the one to let go. To name what's ending. To make the call that no one else can make. Sometimes you need both in the same season, about the same situation Wisdom is knowing which one the moment requires. And grace shows up in unexpected places. "It's okay. It's okay" twice she said it. Sometimes, the person you're dreading the conversation with will meet you with more grace than you anticipated.

Here's what I've learned sitting with leaders over the years: the conversation you ' re avoiding is the one running your leadership. It's taking up space. It's eroding trust in the silence. It's compounding every day you wait. You don't have to be ready. I wasn't ready in that hospital room I wasn't ready on November 20th But you must be willing. Willing to ask the question when the people in the room have already decided that it isn't worth asking. Willing to name what's ending when no one else will. Willing to feel the discomfort long enough to get to the other side.

The leaders who grow are the ones who stop avoiding. They learn that clarity even when it hurts is kinder than silence. They learn that some conversations are fights, some are releases, and wisdom is knowing which one is needed in that moment. So, wherever you are right now, whatever conversation is weighing on your chest, waiting—know this: you ' re more ready than you think. And the person on the other side might just meet you with grace.

The glass doesn't kill you. You swallow it. It scrapes. And then it passes. And sometimes on the other side there are pancakes. What conversation do you need to have?

Cardinal Point Nudge:

The conversation you ' re avoiding is taxing your advancement as a leader. The longer you wait, the more it costs.

Chapter 7: Resilience: What It Actually Looks Like

When It's Real

Tania never complained once. I need you to understand what I mean by this because it sounds like an exaggeration, but it's not. Over ten years, Tania lost the ability to walk, feed herself, or speak clearly. She had a feeding tube that caused her intense pain at times, and she needed help with every intimate task bathing, toileting, and dressing. She was dying in her thirties from a disease she inherited through no fault of her own. Through all of it, she never once said, "Why me?"

Her empathy never abandoned her. I'd come home from work and talk about the kids I was counseling kids who were struggling to overcome trauma, abuse, and the stuff that keeps you up at night. Tania would lean forward in her wheelchair unable to walk, unable to hold a book, unable to feed herself and she'd say, "Oh no. Oh no. " It hurt her hearing it. She still felt for others. One night, one of my kids went into a crisis. The parent was overwhelmed and called me. Tania saw my face. She said, "Go. I'll be okay." So, I went. That was her. Even when she needed help with almost everything, she was still thinking about everyone else.

And despite needing help with nearly everything, she always tried to comb her own hair, to stand up, and whatever little thing she could still do for herself. Perseverance was in her DNA. She was determined, never giving up, always trying. Researchers call it "ordinary magic," the idea that resilience isn't rare or special, just the normal human response to hardship when the right systems are in place: family, community, meaning, and connection. But I didn't need to read a specialist to understand it. I just watched her.

"You have power over your mind not outside events. Realize this, and you will find strength " Marcus Aurelius

The Presence of Self: What Tania Taught Me About Resilience

I used to think resilience was about toughness, grit, the ability to take a punch and keep standing. White-knuckle your way through. Don't let them see you bleed. Then I watched Tania battle Huntington's for ten years, and I learned I had it wrong. Resilience was in her DNA. If there's an EQ gene, she would have it. She pursued her doctorate while working full-time, living mostly in the library for seven years Our marriage was fantastic for the first two years—even though we seldom saw each other. She was that driven.

I use a term in coaching: cozy. It's what happens when people stop pushing. When they settle. When they surrender to the odds and coast. Tania had a 50/50 chance of inheriting Huntington's Many people would have gotten cozy—why push so hard if I might not be here tomorrow or the next day?

This was us on our honeymoon, lost hiking in Yellowstone (1997), stopping for an old-school selfie.

Why grind through a doctorate if the disease might take it all away? She didn't give up, and that defined her.

And when the disease came, her resilience didn't disappear It just showed up differently. She held me while I cried about losing her. Think about that. She comforted me about her dying. A host of hospital visits, trips to the ER, the exhaustion of it all, and then leaving her home to live in a facility at thirty-six years old. She did it with grace.

One moment has stayed with me. She needed an ultrasound. By then, she was deep into the disease, and everything was hard. I helped her out of the wheelchair. The nurses were trying not to cause her distress, but it was difficult since she had a lot of discomfort and was not physically capable of moving herself. They got her through the procedure and got her back to the waiting room, tucking her back

into the wheelchair as gently as they could. As they turned to walk away, she said in that sweet way she always did:

"Thank you."

They stopped, turned around, and said, "Of course. " You could see it on their faces. They were astonished. That was her.

This photo was taken a year before she died, with her mom and her nephew Westin, at a Friends of Huntington’s Disease golf event. Tania wasn't tough; she was soft, gentle, and quick to laugh. She cried when she needed to cry. But she never complained. Never asked why this was happening to her. She never turned her suffering into a story about injustice. When things went wrong and things went wrong constantly, relentlessly, in ways that would have broken most people her response was a giggle and "Oh no, oh no. " Then she'd wait for us to figure out what to do next.

Notice the problem, handle it, maybe even laugh about it, but move on. That's what she learned growing up on a farm in rural North Dakota, watching her family carry that mantra. That's what she taught me across a decade of watching her refuse to let a disease define her. She knew who she was a wife, daughter, sister, pharmacist, and a person of faith. Huntington's could take her abilities. It could not take her identity. The disease was something that was happening to her, but it wasn't her.

That distinction between what happens to you and who you are is the foundation of everything I now believe about resilience. In the photo to the left, Tania was a couple of years before symptoms started, warm, and strong. Happy.

It's A Mindset

I think about that lesson when I sit with leaders who complain constantly about the board, pay, market, team, and pressure Everybody has got a grievance. Everybody wants you to know how difficult they have it. Here's the thing about complaining: it rewires your brain. Every time you do it, you make future complaining more likely. Complain enough, and your brain starts searching for problems, building a case for grievance. And chronic negativity damages the part of your brain you need for problem-solving.

Complaining doesn't just make you feel worse; it makes you worse at your job. But this isn't about suppressing legitimate concerns or pretending everything is fine There's a difference between raising a problem to solve it and rehearsing a problem to justify your suffering. Name what's wrong clearly, without drama then pivot to what you ' re going to do about it. That pivot is everything.

A Way of Holding your Suffering

I need to pause here and say something important because resilience has become a loaded word. Parul Sehgal called it " a doubling down of old bootstrap logic, where your success or your failure comes down to your character I dream of never being called resilient again in my life. I'm exhausted by strength. I want support. I want softness. I want ease...not patted on the back for how well I take a hit. Or for how many. " That critique is legitimate. But that's not what I'm talking about. I'm talking about what is inside. The thing Tania had that I see missing in a lot of leaders. It's a mindset. A way of holding your suffering without letting it swallow you whole.

Tania had this quiet knowing—that life was hard; that her situation was brutal, and that it could still be worse. It was not denial or fake positivity, just plain truth. She held it without being consumed by it. That's what's missing in most leaders I coach. Not tough. Perspective. You can't manufacture it. But you can recognize when you ' re losing it. You can catch yourself from spiraling downward over something that isn't the tragedy you ' re making it out to be. You can pause and accept the discomfort instead of running from it. Lean into the hard thing instead of allowing it to numb you.

After Tania died, people sent me books. One was about a man who lost his wife, his mother-in-law, and his two children in a van accident. He was driving. I read a few chapters. Then I closed the book and put it on the shelf. No need to read on.

I got it.

Years earlier, I had done a presentation for teenagers on stress and resilience. At the end, I asked them: "What's the core takeaway?" A kid in the back raised his hand:

"Someone always has it worse."

That kid understood something that takes most adults decades to learn not to dismiss their own pain, but to manage it effectively. Your suffering is real, but it's not the worst suffering in the world. Both things are true simultaneously

Meaning

Resilience lives in the space between those two truths. The leaders I work with who burn out fastest are the ones who can't hold that space. They either minimize their struggles until they collapse, or they magnify them until every setback becomes a crisis. The ones who last? They've learned to say: This is hard. I'm struggling. And I'm not the only one who has ever faced something hard. That's not a weakness; it is proportionate. And proportion is important for leadership skills.

Viktor Frankl survived Auschwitz, watching people die all around him, and noticed something: the ones who made it weren't always the strongest or the healthiest. They were the ones who had a reason to live. A "why" that made the suffering bearable.

I ask leaders sometimes: If your title disappeared tomorrow, who would you be? The ones who struggle to answer are usually the ones running on fumes. The role consumes the self. When the role gets hard and it will there's nothing left to draw upon. So, I ask them about their teams: do your people know why their work matters? Not the mission statement on the wall, the real reason, the human impact, the stories that make the grind make sense. Because when things get hard, that's what gets you through to the other side, not perks, stock options, or ping pong tables, but meaning.

41

The Presence of Self

Here's what we need to understand about resilience: it isn't the absence of pain It isn't the mask you wear to look strong It isn't grit, or being tough, or refusing to feel. And it sure as hell isn't something to demand from people while ignoring what's breaking them. Resilience is the presence of self even when everything else is being stripped away.

So, when you ' re sitting across from me, telling me about the stress and the pressure and the market and the team I'm listening, I believe you. Your struggle is real.

But I'm also going to ask you: what’s the pivot? You've noticed the problem. Now what are you going to do about it? I am not trying to elicit a white-knuckle or performative response, certainly not the version that lets your organization off the hook while you grind yourself down.

I am hoping for a version of the issue and its resolution where you stay intact, where you know who you are and can separate that from what's happening to you. I want to hear you hold on to both truths, that this is hard indeed, but also that you are not the only one and keep moving anyway That's resilience and the kind of resilience that can be sustainable.

Strong and Warm

Don't get me wrong; you can be strong and warm simultaneously, in leadership or in life. At MarineMax, I did a coaching exercise called Strong and Warm. Think of the happy warrior, a leader who can hold the line and still make you feel seen and heard. They do not crumble under pressure but also refuse to turn cold.

Tania was strong and warm. She could manage her suffering without complaint, still leaning over in her wheelchair to comfort me, still saying "Oh no, oh no " when I told her about a struggling kid, and still thanking the nurses who just put her through a painful procedure. That's the blend. That's what most leaders miss. Those leaders who fail, who suffer, tend to think it's one or the other, that one can only be tough or soft, stoic or emotional, in control or falling apart. The best ones do both. They lead with strength and stay 42

human. They push through difficult moments or issues but also allow themselves to feel the emotional price tag. They don't let the pressure turn them into someone they don't recognize.

The key is to know when to lean into which, when to hold the line and when to let people in, when to be the rock and when to be the shoulder to cry on. Leadership is situational. That's resilience, not the absence of warmth, but the presence of strength and warmth at the same time.

Cardinal Point Nudge:

And when something goes haywire, stop your downward spiral and find one thing that's absurd about the situation, one thing you might laugh about later. See if you can laugh about it now.

Reflection

● What did you see modeled when you were growing up, when things got hard?

● What are you modeling now for the people watching you?

● When was the last time you laughed during something hard not after, during?

● If someone who genuinely had it worse was watching you, would you be embarrassed?

Chapter 8: Be Good to Yourself: What Pressure

Did & My Relationship with Alcohol

I grew up in a small town in North Dakota. Population eighty, give or take. The bar was at the post office. It was the place where you ate and where you hung out. I played pool there, and Pac-Man high score 82,500, summer of 1982 until someone pulled the plug. I was often at the bar. My brother was not. I was drawn to it. The atmosphere, people, and noise filled the quiet.

My brother and I hit the jackpot with our parents. Absolutely amazing mom and dad. My dad let me go on record was a great dad. Still is. He is kind and never pressured me in sports. I could score forty points or get kicked out on a technical, and he'd say the same thing: "Good game. " Find one thing positive. He treated everyone the same; he was a loyal husband and a good friend to many. He was a Green Beret, Special Forces, the A-Team, and among the first Green Berets that Kennedy gave those hats to. I'm proud of him. My mom would be frustrated about my grades or would get a call from the principal, and he'd shrug and say, "You can always sell real estate." Then he'd laugh, walk away, and add, "You'll be okay."

And I'd think: Will I? But I am my father's son, and we both liked to drink. He never let it become the story. I did. My relationship with alcohol, like childhood friends, was a constant throughout my youth. Drinking became an actor in my long goodbye.

What the hell. Here We Go

This is hard to write. I've worked in chemical dependency, running groups, and counseling people in treatment. Still, even though I was a mental health professional, I continued to drink way too much at times, because I saw it as part of the Long Goodbye. My relationship with alcohol goes back to my early teens. Sneaking some of my dad's whiskey often watering down the vodka to cover my tracks. Driving back roads with friends, sipping, then later bingeing. I was heavy into sports, but the sensation-seeking of a good party still pulled me. I was an enabler of others, and they enabled me.

The picture is of me and my brother Bryan. I’m the smaller one. We're at the kitchen table on my grandpa and grandma’s farm in South Dakota, pretending to smoke his pipes. Bryan was pretending. I wasn’t as much. We were wired differently from the start.

High school wasn't that bad, or so I thought at the time, but it was not entirely true. Me and my buddies Miller or Dubois often shared a liter of vodka before a varsity game. I was 15 years old, a sophomore; I once scored 26 points in a varsity game, mostly in the first half, until the vodka wore off, scoring less in the second half. Boys will be boys. But when I left college, I knew I shouldn't go. I had scholarships for basketball and track, but I wasn't ready. I remember thinking: How am I going to change from May to August? I talked to my mom about joining the Air Force. My buddy Murphy was going. It might have been good for me. But it was February of '91 Gulf Shield had just happened and she started crying, so college it was.

No more Discussion