DELS

b720 | Fermín Vázquez Arquitectos

to architecture, ecology, and civic life in the aftermath of the 2008 economic collapse. Situated in Barcelona, Spain, Mercat dels Encants was designed by the firm b720 Fermín Vázquez Arquitectos, co-founded by Fermín Vázquez (b. 1959) and Ana Bassat, and built between 2009 and 2013. Occupying approximately 8,000 square meters, the market was commissioned by the Barcelona d’Infraestructures Municipals (BIMSA) to relocate and reinvigorate one of Europe’s oldest flea markets into a sustainable civic hub that simultaneously honors local traditions and embraces new urban typologies. In this essay, I will guide you through an introduction to the history of the site. I will proceed to an analysis of the design for Encants Market and then discuss the program and ethos of b720. I will conclude with the project’s goals and will discuss the interplay between the design, designer, and their contexts. From there, I will finish on what can be taken and studied for the future of Landscape Architecture.

Portobello Road in London, El Rastro in Madrid, and Porta Portese in Rome are famous antiques and second-hand markets in Europe. In America we call them flea markets, antiquing, thrifting and flipping – In Texas there is the all-famous Canton Trade Days and Round Top Antiques Fair. And notably in Austin we have Kyle Flea Market and Wimberley Market days – but just winding through hill country rural towns, this culture is alive and well, because it’s a way of economic survival and a way to connect with one’s community in sparse rural/urban habitats. The same way this market arose.

“Over more than five centuries, Encants market has occupied a considerable number of sites in Barcelona but has always kept the same name. It also kept its marginal, sprawling character, which made it difficult to regulate and uncomfortable wherever it settled. This was why, perhaps, in 1928, a year before the city was to be the venue for the World’s Fair, it was moved to the plaça de les Glòries, a square which, despite being the point of intersection of three main roads, never attained the central importance that Ildefons Cerdà believed it would have when he planned the Eixample neighbourhood.” (Bordas, 2018)

After being relocated the to Placa de les Glories, the Market has endured for nearly ninety years. Els Encants operated on a degraded site, It was a fifteen-thousand square meter depression at the western edge of Placa de Les Glòries. Later, the square was restructured as a raised traffic junction before the 1992 Olympics. Preparing for the Olympics was a huge movement within the city, which created a mass of reforms across Barcelona that caused massive areas of displacement and renewal – the city planned a competition for plans to transform the junction into a true metropolitan hub, honoring Cerdà’s original plans, but it stalled. Meanwhile, major cultural landmarks like the National Theatre of Catalonia a neoclassical design, the Museu del Dessiny (Design Museum) and the Agbar Tower both contemporary buildings rose around it. Despite attracting over fifty thousand visitors weekly and ranking among the city’s most cost-effective markets, Els Encants remained in dilapidated facilities, overshadowed by ongoing uncertainty about its future.

Finally, in 2008 the City Council called a European competition for the construction of a new market complex that could become permanent. Close to its former location and to emblematic buildings like the Agbar Tower, the Museu del Dessiny, and Avenidas Diagonal and Meridiana. The new market is set forth as mediating element between the redevelopment of the Plaça de les Glòries and the Meridiana axis, an area known as the Bosquet de les Glòries. (Arquitectura Viva, 2018) – They sunk the road junction underground in order to make space for a future park at

the city scale (like central park) – Encants sits to the south, adjacent to this infrastructural development.

Fig. 2 - 2025 Current development - Encants in Red, Dessiny in Blue, Torre Agbar in purple around capped infrastructure.

With the competition in full swing, the new site proposed was “barely half the size of the old one. It raised serious challenges. It was impossible to continue with the same number of stalls without placing them on different levels, and yet the new Els Encants was to keep its ground-level and open-air market character. Moreover, the nature of small family units which had been dealing in the market for generations had to be respected. The stall holders, many of whom were wary, fearing that they could be excluded with a change in the commercial model, were called to attend meetings and workshops with a view to outlining the programme and obtaining endorsement for the project.” (Bordas, 2018) See Fig. 3

Site Analysis

B720 Rejected the notion to design a building of several stories like an enclosed mall to pull people from the streets inside. (Bordas, 2018) In retaliation to that consumerist architecture, their design favors gently inclined planes that form an uninterrupted loop, facilitating a fluid pedestrian experience similar to strolling through a city street. This design strategy not only accommodates the site’s topographical challenges but also enhances accessibility and encourages exploration. By maintaining the open-air character of the traditional market, the design preserves its historical essence while adapting to contemporary urban needs. (Bordas, 2018).

In order to do that though, they had to convince the shop owners that the slopes would not impact shopping, delivery etc.; b720 explored and studied markets all across Europe and found that most are on some type of slope. A slope encourages the walker to slow down as well as creates multi-level perspectives for passersby to see shop items and wares. In addition, the slopes helped separate a hierarchy between shop operations, delivery and street life. With those studies, the public was convinced to move forward with the design. The firm’s approach is a non formal approach to achieve an architectural solution via client and public input. Through their meetings with the public and stakeholders b720 integrates the market seamlessly into the urban fabric not just physically, but socially as well.

As a part of my study abroad program with Texas A&M in Barcelona 2013, I was able to visit this site first hand just after it was built and experience and participate in its market – which reminded me so much of American flea markets – which we ourselves also push aside or look at shamefully and find usually sequestered to offbeat areas around a city and rural areas. This project looks to change that mentality by giving thrifting and flea markets a beautiful stage in which to operate on in a developing urban center. Just in its vicinity are the Tore Agbar building which has become so iconic to the Barcelona skyline – b720 worked with Jean Nouvel on this project, the Museu del Disseny (Design museum) is adjacent and creates a node between Encants and the Agbar. The museum features a viewing deck that overlooks the new park and the surrounding area. The walk between the Market and the

Agbar was intensive and hot, there were not many street trees established in 2013. The walks in this area are very long because the architecture around it is so massively scaled, which is why the canopy is the size that it is.

We intended to see the Tore Agbar in person and in order to do that we took the metro to Mercat dels Encants. Encants provided much needed shade from an otherwise treeless post-industrial part of the city that was autocentric – this part of the city at the time (2013) was a far cry from what the rest of Barcelona was as a city, it was like being transported back to Houston!

The site converges with the street by bending of the sloped platforms at the perimeter of the site.

This blurs the street and access levels into the market itself almost like an MC Escher illustration, there is no beginning and there is no end. No matter where you enter from the street one will always run into a vendor. This is achieved by placing administration, property & market management, storage and parking below street grade. This leaves space at street level to be a plaza.

The gargantuan floating roofs just feel a part of the space itself as if they had always been there – and when we experienced bartering with the vendors it seemed like they had always enjoyed the space. Yet it was a complete-

ly new architectural typology! The massive roof, held up by slender columns arranged in a grid, protects the market from sun and rain while the ceiling, in all its glittering glory is made of reflective stainless-steel surfaces. Each structural module strip of canopy is divided into triangular facets that each slope differently to reflect light,

the atmosphere and the surrounding scenery. This creates a continuous phenomenon that reflects the people moving within the market, the light and shadows being reflected off the ground, and at its edges, it reflects the city – inviting all into the market. It creates a lasting temporal impression, a kaleidoscope of life.

Beneath the behemoth canopy, market stalls constructed out of metal sheets with pull down garage doors in the form of closets help shop owners prominently display their goods on sale. The slabs that these rest on are just ever so slightly elevated from the walking plane allowing viewers to see shop items while in the market and from the street. These stalls are modular in nature and are linear. Using that linear quality, they gradually wrap and spiral with the slope of the plaza around a wide central space used for early morning auctions. This allows shops to be allocated on multiple levels without losing visuals of the central square or having any kind of walled structure. “Despite the reduction of the market’s surface area, almost ninety-two per cent of the previously registered three hundred and fifteen businesses have continued their activity in the new market.” (Bordas, 2018)

Culture, Biography, Experience and Theoretical/ Professional Frameworks

Analyzing the site is not simply enough in understanding the complexity and nature of the design and how it arose for the city and for b720. In order to that, we must delve into their formation.

Fermín Vázquez co-founded b720 Arquitectos with Ana Bassat in 1997 and has since led some of Spain’s most iconic architectural projects. b720 operates across scales: architecture, landscape, urban design, embracing a collaborative model rather than the “starchitect”

culture that dominated pre-2008 Spain. His work, recognized with numerous international awards, has been exhibited at institutions like the Centre Pompidou and MoMA. A trusted local partner for major global architects,

Vázquez combines practice with teaching, having held positions at the Barcelona School of Architecture, Bordeaux’s School of Architecture and Landscape, and the European University of Madrid. He currently teaches at IE School of Architecture in Madrid and regularly contributes to international architectural publications.

Vázquez came of age during Spain’s post-Franco modernization and Barcelona’s urban renaissance leading up to the 1992 Olympics. He practiced through the economic boom of the early 2000s and the financial crash of 2008, which deeply impacted Spain’s construction industry and shifted architectural culture toward re-use, resilience, and social programming.

Vazquez studied architecture at the Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Barcelona (ETSAB), which is part of the Polytechnic University of Catalonia (UPC). His education emphasized modern architecture and urban design, placing him within a tradition of critical regionalism and urban integration, both central themes in Barcelona’s architectural culture.

Vázquez’s training remained firmly architectural — but his practice evolved to incorporate landscape urbanism, urban ecology, and adaptive reuse post 2008.

In the context of the financial crash in Spain, where economic and environmental considerations prompted a reevaluation of urban development practices; the Mercat dels Encants emphasizes adaptive reuse of materials,

integration with public transportation, and promotion of local commerce which aligns with broader efforts to reinvigorate large infrastructure across the city. By fostering a multifunctional public space that supports economic activity and social engagement, the market contributes to a more inclusive urban ecosystem. Similar projects rising out of the area at the time were Born Market and Cultural Center (2007-2013) by BOPBAA Arquitectura and Sants Market (2008-2015) by Pb2 Both historic heritage spaces adaptively reused for market space while maintaining historic restoration and uniqueness of the sites. The motion to reuse these dead spaces in a new way was happening, and it was hot!

An earlier project that preceded this movement is the readaptation of La Fabrica by Ricardo Bofill. An incredible achievement readapting an old cement factory into a new brutalist residential typology that blends Spanish/Moorish neoclassical with the industrial elements of the old factory. Creating a new vibrant language of spaces and gardens with the use of natural materials so well known to Barcelona. The space is a combined home, office and urban terrace garden. What I’m trying to get at though is this idea of imagining a space and its potential –rather than seeing it as an eyesore. This comes from the heart of the picturesque movement. In this instance, it’s for an abandoned cement factory in an industrialized part of town – not some unaltered natural land. It was these practices and ideas from Bofill amongst others that made a push toward adaptive reuse. A reimagining of spaces for their potential and a criticism on their current state. In 2014, Luis Pradanos writes about the crises Spaniard architects faced after the 2008 financial collapse. He points to a crisis of growth, because in nature things do not grow in perpetuity – It was “critics of capitalism worldwide that emphasized that in the context of a finite biosphere, constant economic growth is a biophysical

impossibility and systemic social and ecological limits to growth can no longer be ignored. The problem is not a lack of growth but rather the globalization of an economic system addicted to constant growth, which destroys the ecological planetary systems that support life on Earth while failing to fulfill its social promises.” (Pradanos 2018, pg. 1)

Emerging within a cultural moment of postgrowth imaginaries—visions of urban life less dependent on the extractive and expansionist logics of late capitalism—b720’s work can be understood not merely as architectural production, but as a form of cultural resistance. Their design approach sought to create a resilient urban ecology: a space that fosters civic economies, social exchange, and environmental accountability at the metropolitan scale. Crucially, the design for Encants was not the product of the architect’s vision alone. It was—and remains—a response to a specific temporal urban condition: the pressures of displacement, infrastructure expansion, and economic uncertainty that shaped the site and its community. Encants is an emergent system, shaped as much by the market’s users and the city’s shifting needs as by b720’s architectural interventions.

As Manuel Castells, Gustavo Cardoso, and others argue in Aftermath, “when there is a systemic crisis, there is indication of a cultural crisis, of non-sustainability of certain values as the guiding principle of human behavior. Thus, only when and if a fundamental cultural change takes place will new forms of economic organization and institutions emerge, ensuring the sustainability of the evolution of the economic system.” (Castells, Caraça, and Cardoso, 13). Encants represents a critical gesture within this cultural shift. Recognizing that Barcelona—and Spain at large—was in a crisis of late capitalist urbanism, grappling with the environmental costs of overconsumption and construction waste, b720 rejected traditional development models. Instead, they envisioned architecture as a regenerative act: transforming heavy infrastructure and economic uncertainty into spaces of human gathering, exchange, and resilience.

b720 developed their ethos based around these issues by taking on methodologies from ecology and environmental studies. The firm has a resoluteness for their commitment to being socially and materially responsible. They work distinctively and selectively with their projects, because they intentionally avoid development of a

particular style or formalistic approach. The firm grounds each project on the premise of ecology and observing emergence. They observe the emergence of a space through the search for a specific solution. That solution is driven by the client and society as inputs or reference points. With those dynamics, each response to program, context, budget, and time constraints is unique and works towards social responsibility.” (Architectuul, 2025)

While there is not a detailed record of Fermín Vázquez’s personal reading, I have found through interviews, lectures, and his firm’s collaborative culture that his intellectual background has been shaped by several key influences; He cites early and ongoing respect for Modernist figures like Mies van der Rohe and Le Corbusier, especially in terms of structural clarity and honest materiality. While within the realm of post-modernism’s Critical Regionalism, He is part of the Barcelona architectural culture that deeply absorbed the lessons of Rafael Moneo, José Antonio Coderch, and Enric Miralles — architects concerned with place, memory, and urban continuity.

Coderch argued that architecture must emerge from local customs, climates, and ways of life. His buildings in Barcelona and the Mediterranean coast often used vernacular materials, emphasized private courtyards, and responded to the slow rhythms of lived experience. His famous 1961 essay “It’s Not Genius We Need Now” critiqued the mechanistic excesses of global modernism and argued for an architecture of human scale, rooted in memory and tradition. Coderch modeled a practice that combined technical rigor with emotional and cultural responsiveness.

Fig. 13 - Coderch - ETSAB Extension- Barcelona

Moneo consistently advocated that architecture should continue and reinterpret the historical narrative of cities rather than rupture it. His projects, like the National Museum of Roman Art in Mérida (1980–86), use material, scale, and rhythm to create conversations between past and present. For Vázquez,

Moneo’s influence is palpable, the idea that new architecture must “speak

to” existing urban memory rather than overwrite it helps explain b720’s restraint at Encants.

Miralles was one of Spain’s most inventive architects, known for treating architecture as landscape, memory field, and experiential sequence. His works — such as the Scottish Parliament Building (1999–2004) and Santa Caterina Market in Barcelona (1997–2005) — weave fragmented geometries that grow organically from site histories and user patterns. Miralles emphasized narrative, temporal layering, and participation, rejecting rigid forms in favor of responsive urbanism. Miralles modeled a practice where architecture could be porous, adaptive, and fundamentally about human experience. At Encants, this is visible in the market’s non-hierarchical paths, blurring of thresholds, and kaleidoscopic reflections — architecture conceived not as a static object but as a living field of interactions.

Educated within Barcelona’s strong tradition of critical regionalism and contextual sensitivity, Vázquez absorbed the lessons of José Antonio Coderch’s humanist regionalism, Rafael Moneo’s historical continuity, and Enric Miralles’s dynamic, landscape-driven urbanism. Each figure emphasized that architecture must be rooted in place, must dialogue with memory, and must support the continuity of urban life—foundations that clearly informed b720’s approach to Mercat dels Encants and beyond.

What is so impressive is that b720 was able to channel and guide that ethos in their professional practice contemporaneously. Every project is driven by their intense ethos which was ingrained in the firm by working in Spain’s post-2008 architectural culture. To carry out those values in the day to day – considering the immensity of going against the grain, the ease of falling back into capitalist culture and the issues that arise in construction

Fig. 17 - Encants Market Street Access

Barcelona Market

and installment, is an astronomical feat to accomplish. I know anyone struggling economically would have a hard time enacting that ethos so there is a question on the architect’s class and what they had to do in order to get the entire project aligned from schematics to construction, which remains elusive.

Vázquez’s projects reveal a philosophical shift toward circular economic models, adaptive reuse, and urban metabolist ideas — even if he does not explicitly reference theorists like Jason Moore or Anna Tsing, the ethos of those ideas are reflected in his practice.

Encants

His fascination with reflective surfaces shows influence from contemporary art — particularly kinetic and optical art from Anish Kapoor or Dan Graham, which play with perception and the viewer’s relationship to space which might’ve had some sort of impact on Encant’s Ceiling.

Through my observations of b720, I’ve found that both founders – while public facing, are elusive people. There is not a whole lot out there on Ana, and I truly had to dig deep to find Fermin’s background – but that’s a part of it all, maintaining a persona that can be attributed in the public sphere while maintaining their private lives. Throughout his career, Fermín Vázquez has operated within a modernist architectural framework rooted in material clarity, structural rigor, and urban integration. Early in his career, Vázquez’s projects reflected late-modernist ideals: precise detailing, a strong relationship to site conditions, and an emphasis on function over stylistic display. Influenced by Barcelona’s post-Olympic boom of the 1990s and early 2000s, his work contributed to the city’s broad efforts to revitalize urban spaces through civic architecture. Some extremely

notable projects that fall in this timeline are Mestre Nicolau 19 Offices(2002), Paseo del Ovalo and Escalinata(2003), Torre Agbar in collaboration with Jean Nouvel(2005), Plaza del Torico(2007), Parc Central del Poblenou(2007). Following the financial crash, Vázquez’s professional approach and market direction evolved in response to Spain’s shifting social and environmental priorities. The firm had to go international to survive. Without formally declaring allegiance to a specific movement, his projects, including the Mercat dels Encants, began to embody the values of landscape urbanism and postgrowth urbanism in a move to foster Urban Ecologies. This evolution emphasized circular economic principles, social sustainability, and the creation of urban ecosystems over isolated architectural gestures. His architecture increasingly incorporated landscape thinking: fluid, interconnected ground planes, public space continuity, and ecological responsiveness at metropolitan scales.

Vázquez’s professional practice is marked by a consistent social commitment which is due to Ana Bassat. She plays a crucial role in shaping the firm’s strategic, cultural, and professional identity. While trained not as a designer but as a business administrator and cultural manager, Bassat’s influence was vital in navigating the complex intersection of architecture, public relations, client engagement, and firm management. Her background provided the structural and strategic foundation that allowed b720 to position itself competitively in both the Spanish and international architectural scenes during periods of economic growth and crisis alike. In many ways, Ana Bassat’s contribution can be seen as the organizational and cultural scaffolding that enabled Fermín Vázquez’s architectural vision to respond dynamically to Spain’s rapidly changing social and environmental conditions.

Rather than approaching architecture as isolated formal invention, he treats it as a form of social infrastructure — a way of addressing economic, ecological, and urban challenges simultaneously. His projects, Fig. 18 - Ana Bassat - b720

especially after 2008, reveal a drive toward efficiency without austerity and a generosity of civic spirit, aligning with broader currents in contemporary European urbanism that value resilience, adaptability, and public life.

Vázquez has contributed essays, lectures, and interviews that articulate a vision of architecture as a catalyst for social interaction and urban transformation. His discourse emphasizes the necessity of designing for public life, ensuring urban continuity, and merging architectural and ecological systems to meet contemporary challenges. Through his practice at b720, Vázquez has aligned with critical regionalism, landscape urbanism, and postgrowth urban ideals, without subscribing to any rigid stylistic brand. His work resists postmodernist irony, technological spectacle, or architectural excess, instead advancing a rational and pragmatic, ecological modernism grounded in flexibility, site adaptation, and civic responsibility.

In essence, Fermín Vázquez’s career represents a deliberate evolution from disciplined modernism to a landscape- and ecology-driven urbanism, reflecting an ongoing engagement with the cultural, economic, and environmental realities of the 21st century.

Conclusion

The Mercat dels Encants stands as a vibrant artifact of Barcelona’s architectural, ecological, and social transformation.. Through its design, its designers, and its context, it embodies a new paradigm of public architecture that challenges extractive, capitalist urban models. The project reveals how architecture can serve as social infrastructure — rethinking the market typology to prioritize adaptability, public space, and resilience. Rather than succumbing to the commercialized language of malls or hyper-designed spectacles, Mercat dels Encants maintains the open-air, flexible spirit of historic European markets while embedding it in a landscape urbanist framework that addresses larger ecological and infrastructural questions. The sloped circulation paths, the kaleidoscopic mirrored canopy, and the seamless merging of street and plaza together foster an urban ecology — one that honors both the cultural memory of the market and the evolving needs of a dense, changing city.

In analyzing the project and the designers behind it, it is clear that Vázquez’s architectural evolution reflects a broader shift in Spain’s cultural consciousness. Educated as a modernist architect but deeply influ-

enced by critical regionalism, postgrowth urbanism, and landscape thinking, Vázquez transformed his practice in response to Spain’s post-crash realities. His work with Ana Bassat — who played a crucial strategic role in maintaining the firm’s ethical focus — resulted in a professional model that values social resilience, environmental stewardship, and collaboration with public voices. Their approach, emerging in dialogue with intellectual frameworks like those of Luis I. Prádanos and Jason W. Moore, treats architecture not as an isolated object but as a living system within a fragile network.

Thus, the Mercat dels Encants is not only a design solution but a cultural expression: it is the crystallization of a society grappling with the aftermath of unchecked growth, searching for sustainable ways to inhabit and reinhabit its cities. The weave between the physical form of the market, the evolving philosophies of its designers, and the broader socio-economic context of post-2008 Spain proves inseparable and essential to its reading. Moving forward, future studies on Mercat dels Encants and b720’s body of work could further investigate how adaptive reuse and landscape urbanism have continued to influence other major urban projects, how informal economies are spatialized within cities, and how architects can foster civic resilience not merely through sustainable technologies, but through cultural, participatory, and spatial frameworks that anticipate human and ecological emergence. Encants Market teaches us that architecture, when deeply attuned to social life, cultural memory, and ecological systems, can become not just a background for urban life but an active catalyst for its renewal.

Bibliography

Ábalos, Iñaki. Atlas of the Contemporary Metropolis. MIT Press, 2000.

Ábalos, Iñaki. Enric Miralles: Works and Projects 1975–1995. Editorial Gustavo Gili, 1995.

Arquitectura Viva. “Encants Market.” Arquitectura Viva, 2018, https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/encants-market.

Architectuul. “b720 Fermín Vázquez Arquitectos.” Architectuul, 2025, https://architectuul.com/architect/ b720-fermin-vazquez-arquitectos.

“A+U: Architecture and Urbanism.” “b720 Fermín Vázquez Arquitectos: Encants Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain 2013.” A+U: Architecture and Urbanism, no. 10529, Oct. 2014, pp. 64–73.

“A+U: Architecture and Urbanism.” “David Chipperfield and b720 Arquitectos: City of Justice - Barcelona and L’Hospitalet de Llobregat, Spain 2002–2009.” A+U: Architecture and Urbanism, no. 477, 2010.

Bordas, Laura. “Els Encants Market, Barcelona.” Arquitectura Viva, 2018, https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/ encants-market.

b720 Fermín Vázquez Arquitectos. “Mercat dels Encants.” b720.com, https://b720.com/b720-projects/encants-market/. Accessed April 2025.

Capelli, Vittorio. “Enric Miralles: The Topography of Memory.” Domus, 1997.

Castells, Manuel, João Caraça, and Gustavo Cardoso, editors. Aftermath: The Cultures of the Economic Crisis. Oxford University Press, 2012.

Coderch, José Antonio. “It’s Not Genius We Need Now.” Architectural Design, 1961.

Cohn, David. “Glitter Bug.” The Architectural Review, no. 1417, 2015, pp. 57–64.

Gómez-Moriana, Rafael. “b720 Corners the Flea Market.” Mark: Another Architecture, no. 48, 2014, pp. 22–23.

“Encants Barcelona, Barcelona, España 2013: b720 Fermín Vázquez Arquitectos.” Arquine: Revista Internacional de Arquitectura = International Architecture Magazine, no. 70, 2014, pp. 98–103.

Fernández-Galiano, Luis. “Rafael Moneo and the Poetics of Architecture.” Arquitectura Viva, 1996.

Moneo, Rafael. Theoretical Anxiety and Design Strategies in the Work of Eight Contemporary Architects. MIT Press, 2004.

Prádanos, Luis I. Postgrowth Imaginaries: New Ecologies and Counterhegemonic Culture in Post-2008 Spain. Liverpool University Press, 2018.

Spoden, Désirée. “Els-Encants-Markt in Barcelona: Entwurf/Design, b720 Fermín Vázquez Arquitectos, ES-Barcelona.” AIT: Architektur, Innenarchitektur, Technischer Ausbau, no. 12, 2014, pp. 102–103.

List of figures

Introduction Image. Mercat dels Encants. Photograph by Rafael Vargas. b720 Arquitectos, https://b720.com/ b720-projects/encants-market/. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 1

Map of the City of Barcelona. Google Maps, maps.google.com. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 2

Bosquet de les Glòries: Depiction of key site and adjacent developments. Google Maps, maps.google.com. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 3

Car-centric old city center and historic Encants market. Photograph by Rafael Vargas. PublicSpace, https:// www.publicspace.org/works/-/project/h078-mercat-dels-encants. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 4

Parti diagrams illustrating design strategies by b720 Arquitectos. PublicSpace, https://www.publicspace.org/ works/-/project/h078-mercat-dels-encants. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 5

Stair access overlooking the new Mercat dels Encants. Photograph by Rafael Vargas. PublicSpace, https://www. publicspace.org/works/-/project/h078-mercat-dels-encants. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 6

Solar diagram section of Mercat dels Encants. Metalocus, https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/mercat-dels-encants-b720. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 7

Site cross-section of Mercat dels Encants. Metalocus, https://www.metalocus.es/en/news/mercat-dels-encants-b720. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 8

Street access to the new Mercat dels Encants. Photograph by Rafael Vargas. PublicSpace, https://www.publicspace.org/works/-/project/h078-mercat-dels-encants. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 9

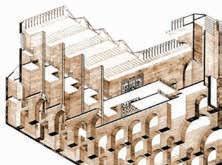

Axonometric site section of Mercat dels Encants. Arquitectura Viva, https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/encants-market. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 10

Site cross-section of Mercat dels Encants. Arquitectura Viva, https://arquitecturaviva.com/works/encants-market. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 11

La Fábrica, Ricardo Bofill’s converted cement factory residence. Photograph by Salva López. House & Garden, https://www.houseandgarden.co.uk/gallery/ricardo-bofill-visions-of-architecture. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 12

Terrace gardens of La Fábrica, Ricardo Bofill’s residence. Photograph by Salva López. House & Garden, https:// www.houseandgarden.co.uk/gallery/ricardo-bofill-visions-of-architecture. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 13

Extension of the Barcelona School of Architecture (ETSAB) by José Antonio Coderch. Arquitectura Catalana, https://www.arquitecturacatalana.cat/en/works/ampliacio-de-lescola-tecnica-superior-darquitectura-de-barcelona-etsab-upc. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 14

Axonometric drawing of the National Museum of Roman Art by Rafael Moneo. Rafael Moneo Arquitecto, https://rafaelmoneo.com/en/projects/national-museum-of-roman-art/. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 15

Mercat de Santa Caterina, Barcelona. Gratis Barcelona, https://www.gratisbarcelona.com/EN/GratisinBarcelona/CiutatVella/SantaCaterinaMarket.html. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 16

Portrait of Fermín Vázquez. Photograph by Rafael Vargas. b720 Arquitectos, https://b720.com/team/fermin-vazquez/. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 17

Street access to Mercat dels Encants. Photograph by Rafael Vargas. b720 Arquitectos, https://b720.com/ b720-projects/encants-market/. Accessed April 2025.

Fig. 18

Portrait of Ana Bassat. Photograph by Rafael Vargas. b720 Arquitectos, https://b720.com/team/ana-bassat/. Accessed April 2025.

Conclusion Image

Conclusion Image. Bird’s-eye view of Mercat dels Encants. Photograph by Rafael Vargas. b720 Arquitectos, https://b720.com/b720-projects/encants-market/. Accessed April 2025.