LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

Dear Readers,

It is a great pleasure to present to you the issue of the Korean Unification from a European Perspective: Lessons from Poland and Europe Supporting Korea in Its Path Towards Unification, Special Report of the Korea Monitor project, funded by a UniKorea grant, financed by the UniKorea Foundation.

The goal of the Korean Unification from a European Perspective: Lessons from Poland and Europe Supporting Korea in Its Path Towards Unification, Special Report based on Polish history and Europe’s experience in unification and building a peaceful continent to create a comprehensive outlook on Korean Unification for an open public, researchers and policymakers.

In the Korea Monitor project, owing to the support of the UniKorea Foundation, we strived to contribute to the discourse on Korean unification through the organization of online discussions and the publication of analytical articles. Over the course of the project, we were able to bring together dozens of experts, researchers and journalists from Europe, and the Republic of Korea, who are committed to the issue of Korean unification and the relationships linking Poland and Europe with the Korean Peninsula. By sharing best practices and accumulated experience, we were able to present paths and processes which, based on European experience, may lead to Korean Unification.

With this Special Report, we would like to extend our gratitude to the UniKorea Foundation, for providing us, through the Korea Monitor project, with the opportunity to explore the European perspective on Korean unification and to the UniKorea team, especially Mr. Jin Seok Kwak and Ms. Jihee Lee, for their continued support.

We deeply believe that through initiatives like Korea Monitor project, by working together and supporting Korea in its efforts towards Unification, we can also contribute to the prosperity and peace of the Central European region.

Liliana Śmiech President of the Board

Photo: Dénes Szilágyi

Szymon Polewka Program Coordinator

KOREAN UNIFICATION FROM A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

친애하는 독자 여러분,

일과 나눔 재단의 지원으로 진행된 코리아 모니터 프로젝트의 특별 보고

서, “유럽의 관점으로 바라보는 한반도 통일: 폴란드와 유럽이 한국의 통

일 여정에 주는 교훈” 을 소개하게 되어 큰 영광입니다. “유럽의 관점으로 바라보는 한반도 통일: 폴란드와 유럽이 한국의 통일 여정에 주

는 교훈” 이라는 이 특별 보고서는, 폴란드의 역사와 유럽의 통일 및 평화로운 대

륙 건설 과정을 바탕으로 연구직 종사자, 정책 입안자들은 물론 일반 대중을 위 한 한국 통일에 대한 포괄적 전망 제시를 목표로 합니다. 바르샤바 연구소는 통일과 나눔 재단의 지원을 받은 코리아 모니터 프로젝트를 통해, 온라인 토론을 진행하고 연구지를 발행함으로써 한국 통일에 대한 담론에 기여하고자 했습니다. 프로젝트 기간 동안

대한민국의 다수의 전문가, 연 구자, 언론인을 한자리에 모아 한반도 통일 및 폴란드 한국 관계, 더 크게는 유럽 한국 관계를 돈독히하는 자리를 마련했습니다 유럽의 선례와 경험을 공유함으 로써, 한반도 통일로 이어질 수 있는 경로와 과정을 유럽의 경험을 바탕으로 하

여 제시할 수 있었습니다

이 특별 보고서를 통해, 코리아 모니터 프로젝트를 통해 한국 통일에 대한 유럽

의 관점을 탐구할 기회를 제공해 주신 것에 대한 깊은 감사를 통일과 나눔 재단 에 전합니다. 특히 곽진석 선생님과 이지희 선생님을 비롯한 통일과 나눔 팀 여러

분의 끊임없는 지원에 감사드립니다 덕분에 많은 도움을 받았습니다

앞으로도 코리아 모니터 프로젝트와 같은 이니셔티브를 통해서 한국의 통일을

위한 노력을 지원하고, 나아가 함께 협력함으로써 중앙유럽의 번영과 평화에도 기여할 수 있을 것이라고 굳게 믿습니다.

릴리아나 스미치 소장

시몬 폴레브카

프로그램 코디네이터

KOREAN UNIFICATION FROM A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE

LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

KOREAN UNIFICATION FROM A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

— SPECIAL REPORT —

© Copyright 2025

The Warsaw Institute Warsaw, Poland

Editorial Team:

Szymon Polewka

Translations:

Gaeun ‘Muriel’ Lee

Printing: www.sindruk.pl

Warsaw Institute

Publisher

Warsaw Institute Wilcza 9, 00-538 Warsaw, Poland

www.warsawinstitute.org

The project is funded by a UniKorea grant, financed by the UniKorea Foundation.

The Kwangju and Poznań Uprisings: Struggles for Freedom and Democracy 9

Professor Grażyna Strnad

Lessons from Systemic Transformation in Poland: Implications for Korean Reunification 25 Sylwia Szyc, Ph.D.

The decommunization of public space as a process of shaping collective memory: the example of the Polish state in the context of the potential unification of the Korean states 42

Karol Starowicz

United in Division: Lessons from German Unification for Korea 58

Monika K. Kwiatkowska

A European model of institutionalization in the process of Korea unification 70 Han-Ul Chang

Professor, Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań, The Faculty of Political Science and Journalism, Vice-President of the Polish Association of Korean Studies

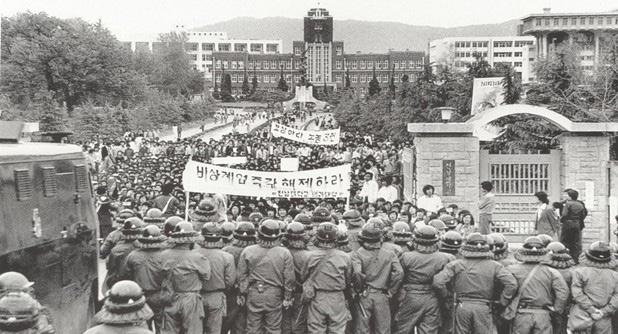

Introduction

The memory of the events of the Kwangju Uprising (May 18-27, 1980) and the Poznań June 1956 Uprising (June 28-29, 1956) is of paramount importance for understanding the political history of Poland and South Korea, shaping their contemporary identity and national memory. Commemorating the events and people who gave their lives in the fight against authoritarian regimes is crucial for understanding the role of rebellion and social resistance during that period. The stories of known and unknown heroes not only remind us of the tragic events, but also have inspired subsequent

generations who fought for freedom, justice, and democratic change in social and political spaces. Monuments, memorial plaques, and museums are among the most visible and lasting ways of commemorating the past. In South Korea and Poland, you can find places dedicated to the memory of these events. For example, the 5-18 Memorial Park in Kwangju, or the Poznań Uprising Museum - June 1956, located in Poznań. These places are a symbolic remembrance of the events and people who gave their lives in the fight for freedom and democracy.

After World War II, communist ideology was imposed across Central and Eastern Europe. The totalitarian communism built in the “people’s democracy” bloc countries led to the elimination of political pluralism and parliamentary democracy. The Communist Party exercised power in these countries through mass terror and intimidation of society, utilizing a widespread security apparatus. In the economic sphere, private property was abolished, collectivization of agriculture and industrialization were introduced, leading to a significant decline in living standards. In the cultural sphere, the cult of Joseph Stalin was imposed, the dominance of Marxist ideology was enforced, and Christian churches and anti-communist ideologies were combated. The transformation of communist systems occurred both from below and above. The basis of grassroots anti-totalitarian movements was the progressive reconstruction of bonds of social solidarity. This led to social revolts, during which demands were made for improved living conditions and the democratization of political life. This top-down de-Stalinization entailed a condemnation of the cult of personality, amnesty for political prisoners, reorganization of the security apparatus, and the introduction of reforms that were intended to safeguard against the “errors” and “distortions” of communism, but without undermining the system’s foundations. In the first years after the end of the war, throughout Polish society communists propagated the belief that the “new” Poland would be a state built on democratic prin-

ciples, while respecting Polish traditions. This was expressed by the existence of “opposition political parties,” such as the Polish People’s Party (Jankowiak, p. 11). In reality, the communists combated all forms of resistance and civil disobedience against the new government. By the early 1950s, almost all areas of political, social, economic, and cultural life were subordinated to communist ideology and the decisions of a single party – the Polish United Workers’ Party (Makowski, p. 14). A planned and centrally controlled economy was introduced, the spectacular success of which was to be the implementation of the Six-Year Plan (1950–1955). The implementation of this plan ignored the increasingly deteriorating material conditions of the population. From 1953 onward, there was a gradual decline in living standards, caused by reduced wages and increased labor standards. Working conditions deteriorated significantly, and problems arose in the supply of food and consumer goods. Such circumstances led to frustration and dissatisfaction among all segments of society, particularly in Poznań and Greater Poland. The collectivization policy in rural areas caused problems for farmers and owners of medium-sized and large farms. This resulted in reduced agricultural production and food shortages in Poznań’s stores. The newly established craft and supply cooperatives did not solve the problem of food shortages, especially meat (Makowski, p. 22). From August 1955 to May 1956, there was a constant shortage of butter and coal available for sale on the market. From July 1953, the Józef Stalin Poznań Works (then known as the Hipolit Cegielski Metal Industry

Plant) systematically raised labor standards, incorrectly calculated payroll taxes, and inefficiently managed the plants. The deepening problems led to growing dissatisfaction among the plant’s employees. The workers attempted to engage in dialogue with the authorities, including trips by employee representatives to Warsaw. The failure of the talks between the Poznań workers’ delegation and the central authorities, held in Warsaw on June 26, 1956, was the direct cause of the Poznań residents’ decision to take to the streets. The events that unfolded on the streets of Poznań on Thursday, June 28, 1956, resonated widely across the country and beyond. This was achieved thanks to foreign journalists who arrived at the 25th Poznań International Fair (Rybak, Reczek, p. 51). The demonstration gradually took on a national, anti-communist, and anti-Soviet character. Slogans included: “We want bread!”, “We are hungry!”, “Down with the exploitation of workers!”, “We want a free Poland!”, “Freedom!”, “Down with Bolshevism!”, “We demand free elections under UN control!”, “Down with the Russians!”, “Down with the communists!”, “Down with the red bourgeoisie!”, “We want God!”, and “We demand religion in schools!” Religious songs were also sung, which fueled patriotic sentiments (Łuczak, p. 3; Makowski, p. 66). News of the arrest of members of the workers’ delegation caused the previously peaceful crowd to launch a physical attack on a prison in the center of Poznań in order to free the supposedly arrested delegates. The demonstrators then entered the building of the City Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party located on Mickiewicz Street. At the same time, some workers marched on Jan Kochanowski Street to the building of the Voivodeship Office for Public Security, a symbol of citizen oppression and a site of widespread terror. The first shots were fired from the office’s windows, igniting street fighting in Poznań. The demonstrators’ seizure of weapons led to an exchange of fire between workers and communist state officials in front of the Voivodeship Office for Public Security, lasting until late

in the evening. On June 29th, most factories in Poznań remained closed. The authorities decided to suppress the workers’ revolt with military force. The pacification of the rebellious city, which lasted for the next two days, was led by Deputy Minister of National Defense, Army General Stanisław Popławski. On the evening of June 29th, Prime Minister Józef Cyrankiewicz, in his famous radio address to the residents of Poznań, said that “any provocateur or madman who dares to raise his hand against the people’s government should be sure that the people’s government will chop it off [...]” (Łuczak, p. 5). Historians disagree on the actual death toll of the Poznań June 1956 events. In 1981, it was estimated that 74 people died. The latest research indicates 57 victims, while the Institute of National Remembrance estimates the number of victims at 58. Scholarly literature describing these events also reported 100 fatalities, but this has not been fully confirmed by sources. The youngest victim of the Poznań June was 13-year-old Romek Strzałkowski. It is also estimated that approximately 650 people were injured in the fighting (Łuczak, p. 5). Participants in the Poznań demonstration were deemed enemies of the state. On the night of June 28-29, officers of the Office of Security and the Citizens’ Militia conducted an arrest operation against the most active participants. The communist authorities launched numerous investigations, during which confessions were extracted by force, before the “guilty” demonstrators were subsequently tried and punished. In 1957, before the first anniversary of the Poznań June uprising, Władysław Gomułka, First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Polish United Workers’ Party, ordered that these events be kept to a minimum in public spaces. Official commemorations of the first anniversary of the Poznań uprising were to be kept understated. However, in June 1957, the Poznań Church, led by the newly appointed Archbishop Antoni Baraniak, commemorated the victims of the Poznań June Uprising during ceremonial services (Zieliński, p. 347). It is also worth emphasizing

POZNAŃ JUNE UPRISING, 1956, SOURCE: HTTPS://UPLOAD.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/WIKIPEDIA/COMMONS/8/8F/POZNAN_1956.JPG

that one of the first initiatives undertaken by members of the newly organized the “Solidarity” Trade Union in Poznań was the project of erecting a monument commemorating the events of 25 years earlier. For this purpose, the Social Committee for the Construction of the Poznań June 1956 Monument was established. The monument was officially unveiled on June 28, 1981, on the anniversary of the events. On June 28, 1981, Archbishop Jerzy Stroba consecrated the monument (the so-called Poznań Crosses), praying with a crowd of the faithful for the victims of communist terror. After martial law

was imposed in Poland on December 13, 1981, the monument became a symbol of remembrance and opposition to the communist regime (Dabertowa, Lenartowski, p. 64). Commemorating the workers’ revolt of June 28, 1956, was one of the most important postulates of the Poznań “Solidarity” Movement. Pope John Paul II, who visited Poznań during his pilgrimage to Poland in 1983, was not permitted by the communist authorities to pray at the Poznań Crosses. Cultivating the memory of the Poznań June 1956 protests became possible only after the fall of the People’s Republic of Poland and the birth of the Third

KOREAN UNIFICATION FROM A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

POZNAŃ JUNE UPRISING, 1956,

SOURCE: HTTPS://ARCHIWUM.IPN.GOV.PL/PL/ARCHIW/ARCHIWALIA/ARCHIWALIA1/31594,POZNANSKI-CZERWIEC-1956-NA-ARCHIWALNYCH-FOTOGRAFIACH.HTML

MONUMENT TO THE VICTIMS OF JUNE 1956, SOURCE: : HTTP://MONUMENTS-REMEMBRANCE.EU/ PL/PANSTWA/POLSKA/416-POMNIK-POZNANSKIEGO-CZERWCA-1956

THE POZNAŃ UPRISING MUSEUM, POZNAŃ, SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.DREAMSTIME.COM/POZNAN-POLANDAPRIL-LARGE-METAL-MONUMENT-OUTSIDE-STONE-MUSEUMBUILDING-COMMEMORATING-POZNA%C5%84-JUNE-PROTESTSOUTDOOR-SCULPTURE-IMAGE374687473

Polish Republic. The struggle of the democratic opposition and the “Solidarity” trade union to commemorate the Poznań June 1956 protests was part of a nationwide process that characterized the years 1976–1989. In the undemocratic state of the Polish People’s Republic, the memory of the past became a site of great political struggle. Ultimately, the Poznań Solidarity Movement, despite adversity and obstacles from the communist authorities, managed to preserve and cultivate the memory of the Poznań June 1956 uprising. The events of 1989 set Poland on a path of fundamental change that forever altered its political, social, and economic landscape. A key event of that time was the Round Table Talks, initiating dialogue between the communist government and the opposition. Representatives from various backgrounds participating in the talks jointly developed a direction for change that would contribute to the construction of a democratic Poland. Over the past three decades, Poland

has undergone a remarkable transformation, from an authoritarian state to a democratic one (Gomułka, p. 7-16). During this turbulent journey to democracy, the memory of the Poznań June 1956 uprisings was preserved, events that became a history lesson for future generations of Poles fighting for human rights, freedom, and democracy. Jan Nowak-Jeziorański, a Polish journalist and political activist, said during his visit to Poznań in 1996: “If there had been no June Thursday in Poznań, there would have been no Polish October. If there had been no revolution in 1956, which without leadership and organization would have limited itself to what could have been won at the time, there would have been neither the workers’ December of 1970, nor August of 1980, nor Solidarity. There would have been no epochal events of 1989–1990, which brought independence, freedom, and democracy to Poland and its neighbors. It all began here” (Kwilecki, p. 276).

The assassination of President Park Chung Hee on October 26, 1979, exposed internal divisions within the military (Strnad, p. 204). It turned out that the South Korean armed forces were divided into two opposing factions. One faction, composed of military leaders, advocated the military’s withdrawal from politics, while the other advocated continuing Park’s policies. The former faction included both officers trained in the Japanese Imperial Army and graduates of the Korean Military Academy (KMA). Generally, these officers shared the inclination of not having participated in the persecution of the opposition during Park’s rule, and therefore, had no need to fear repercussions from the civilian government. The latter faction consisted primarily of politicized KMA officers, most of whom were members of the intelligence and national security services. Most of them had been involved in political repression, investigations, interrogations, and even torture. After Park’s death, fearing reprisals because of their actions, these politicized officers advocated for the continuation of the Yusin system or the introduction of a civilian government under the supervision of military officers. The pro-Yusin group, known as the “New Military,” was headed by Brigadier General Chun Doo Hwan, head of the Defense and Security Command, who was entrusted with investigating Park’s assassination. The New Military also included officers belonging to a private, secret organization known as the One Group (Hanahoe), as well as military commanders loyal to President Park Chung Hee. Ultima-

tely, a surprise coup, orchestrated by Chun Doo Hwan and General Roh Tae Woo, commander of the 9th Army Division, who was based in Seoul, took place on the night of December 12, 1979, ushering in another chapter of authoritarian politics in South Korea. The events of December 12th marked an internal military coup and the seizure of power in the South Korean Army by uncompromising officers. This radically changed the political situation in the country. The pro-authoritarian military faction, led by Chun, staunchly opposed any attempts at democratic change and took actions that perpetuated the continuation of authoritarian system (Strnad, p.

205-207). The New Military quickly began consolidating power. In April 1980, Chun Doo Hwan was elected to be acting director of the Korean Central Intelligence Agency, which sparked a massive wave of student-organized demonstrations demanding Chun’s resignation, the resignation of the prime minister, the lifting of martial law, and a condemnation of the Yusin system. In response to the protests, Chun Doo Hwan accepted the resignation of Prime Minister Sin Hyŏn-hwak and his cabinet and soon established his own government. However, the demonstrations escalated. On May 15, approximately 100,000 students from thirty Seoul universities participated. At the urging of political opposition leaders Kim Dae Jung and Kim Young Sam, fearing military intervention, the students decided to cancel the planned demonstrations. Two days later, concerned about public sentiment, representatives of the New Military also imposed

MAY 18, 1980,

SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.RCPBML.ORG.UK/WWIE-23/WW23-15/WW23-15-02.HTM

martial law on Cheju Island. Political activities were banned, press, radio, and television censorship was imposed, and all colleges and universities were closed. The new military also arrested potential presidential candidates Kim Dae Jung and Kim Jong Pil and placed Kim Young Sam under house arrest. Other anti-government opposition leaders were also imprisoned (Plunk, p. 5). The government’s campaign to “cleanse society” of “pro-communist rebels” was based on authoritarian laws: the National Security Act (1948) and the Anti-Communist Act (1961). Kim Dae Jung’s hometown of Kwangju, located in South Jeolla Province, soon became a center of political action. The events were officially described as a communist plot to overthrow the South Korean government. On the morning of May 18th, a small group of students from Jeonam University in Kwangju demanded the release of Kim Dae Jung and the lifting of martial law, while confronting a contingent of commandos sent to the city by Chong Ho-yong, commander of the Special Forces Division. Kwangju residents also supported the student protest (Katsiaficas , Na,

p. 12). Convinced by their commanders that Kwangju had been taken over by the communists, soldiers armed with bayonets launched a brutal attack on demonstrators and bystanders, wounding and killing many. After two days of devastating clashes, students, aided by Kwangju residents, began to take control of the city. On May 21st, student activities escalated, forcing the commandos to retreat. Anti-government demonstrations began to spread to neighboring cities. During an attempt to negotiate a ceasefire, Kwangju was surrounded by a cordon of thousands of soldiers. The stalemate in the negotiations lasted several days, and on May 27th, South Korean Army forces, acting on order from the New Military, finally pacified the citizen army in Kwangju. According to official figures, 200 people died. However, witnesses to the tragedy claim that over 2,000 city residents lost their lives. The New Military gained increasing control over the state. On May 31, 1980, the Extraordinary Committee for State Security was established, headed by Chun Doo Hwan. Generals Roh Tae Woo and Chŏng Ho-Yong became members

KOREAN UNIFICATION FROM A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

MEMORIAL HALL. PHOTOS OF THE VICTIMS OF THE GWANGJU MASSACRE, SOURCE: HTTPS://WWW.RCPBML.ORG.UK/WWIE-23/WW23-15/WW23-15-02.HTM

MANGWOL-DONG CEMETERY IN GWANGJU WHERE VICTIMS’ BODIES WERE BURIED, SOURCES: HTTPS://COMMONS.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/WIKI/FILE:MANGWOL-DONG-CEMETERY.JPG

KOREAN UNIFICATION FROM A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

MAY 18 MINJUNG STRUGGLE MEMORIAL TOWER, SOURSE: HTTPS://COMMONS.WIKIMEDIA.ORG/WIKI/FILE:MAY_18TH_MEMORIAL_MONUMENT.JPG

of the committee. The committee’s task was to assume complete oversight of all state functions and authorities. Based on one of its decisions, Kim Dae Jung and other opposition activists were tried in a military court for allegedly planning “treason,” and numerous members of parliament and political parties were also banned from political activity. The Kwangju Massacre was a turning point in the long struggle for democracy in South Korea. It was an expression of civic rebellion, opposition to military dictatorship, and a symbol of the courage and sacrifice of

young Koreans (Hwang, Lee, Jeon, p. 215). The Kwangju Uprising is alternatively referred to as the May 18 Kwangju Democratization Movement, the Kwangju Democratization Struggle, or the May 18 Democratic Uprising. The Kwangju Uprising became a catalyst for a full-fledged democratic movement in the 1980s. The Kwangju Uprising has been depicted in South Korean filmography, as a testament to the tragedy of both the individual and society. The most famous production about Kwangju Uprising is the television series The Hourglass, directed by Kim Jonghak.

Korea is far from Poland, however, despite the significant geographic distance, there are historical similarities. The establishment of diplomatic relations between the Republic of Korea and Poland on November 1, 1989, initiated a dynamic development of mutual contacts. Poland recognizes the Republic of Korea as one of its main strategic partners in the East Asian region. South Korea is considered a democratic country, with advanced technology, an innovative economy and an attractive culture. In Korea, there is also an interest in Polish culture, folklore and music. Koreans and Poles are two proud nations that have gone from authoritarian rule to democracy. The democratic transitions of the Republic of Korea and Poland at the end of the twentieth century offer political scientists a rich history suited for comparative study. Scholarly literature on modes of transition is very

diverse. Samuel Huntington’s model of transition, called transplacement, describes cooperative democratization as result of joint action by government and opposition groups. This is the variety exhibited in the political behaviors in both the Republic of Korea and Poland. “Pact,” “negotiated transition” or “compromise” describe the central features of this model of transition. In transplacement, change occurs within and outside the incumbent elite and reforms occur through cooperation between the old elites and the opposition (Strnad, p. 36). In this form of democratic transition, within the government, there is often a balance between those who seek reform and those who are uncompromising. This balance results in conflict within the government, which must be contested, that is pushed and pulled into formal or informal negotiations with the opposition.

Poland’s democratic transition was precipitated by social reactions to economic conditions in the 1970s. Poland’s government raised food prices while wages stagnated. This and other stresses led to the June 1976 protests and subsequent government crackdown on dissent. Labor unions formed an important group within the opposition. In 1979, the Polish economy shrank for the first time since World War II by 2 percent. The foreign debt reached around 18 billion dollars US by 1980. The labor union Solidarity emerged on August 31, 1980 in Gdańsk at the Lenin Shipyards when the communist government of Poland signed the agreement allowing for its existence. On September 17, 1980, over twenty inter-factory founding committees of free trade unions merged at a congress into one national organization. Solidarity officially registered on November 10, 1980. Lech Wałęsa and other opposition leaders formed a broad anti-Soviet social movement ranging from people associated with the Catholic Church to members of the anti-Soviet left. Democratic transition in Poland revolved around Solidarity, which continuously confronted the communist regime during the 1980s. Solidarity advocated non-violence in its members’ activities (Brzechczyn, p. 172). In September 1981 Solidarity’s first national congress elected Wałęsa as the president and adopted a republican program, the “Self-governing Republic”. The government attempted to destroy the union with martial law in 1981. After several years of repression, the government commenced negotiating with the union. In Poland, the Roundtable Talks between

the government and Solidarity-led opposition led to semi-free elections in 1989. The “Round Table Agreement” was signed on April 4, 1989. The most important demands were: (1) legalization of independent trade unions; (2) the introduction of the office of President (thereby annulling the power of the Communist party general secretary), who would be elected to a 6-year term; and (3) the formation of a Senate. As a result, real political power was vested in a newly created legislature and in a president who would be the chief executive. Solidarity became a legitimate and legal political party. Free elections to 35% of the seats in the Sejm and an entirely free election to the Senate was assured. The 4 June 1989 election brought a landslide victory to Solidarity: 99% of all the seats in the Senate and all of the 35% possible seats in Sejm were won by Solidarity (Kowalski, p. 28). General Wojciech Jaruzelski, whose name was the only one the Communist Party allowed on the ballot for the presidency, won by just one vote in the National Assembly. The system that allowed only 35% of the seats to be contested was soon abolished as well, after the first truly free Sejm elections. The founding election in the new Polish democracy was held as a two-part ballot on June 4 and 18, 1989. After a deal worked out with Solidarity’s leader, Lech Walesa, the National Assembly, formed by the Sejm and the Senate, elected General Wojciech Jaruzelski as president. Some years earlier, in 1981, Jaruzelski served as Prime Minister and Secretary of the Polish United Worker’s Party. This was the same General Jaruzelski who had resorted to martial law to put a stop to Solidarity

and avoid the Soviet Union from intervening in Poland as seemed likely at the time. The Round Table sessions were of momentous importance to the future political developments in Poland. They paved the way to a free and democratic Poland as well as the final abolition of communism in Poland (Musiał, p. 1-8). By the end of August 1989, a Solidarity-led coalition government was formed and in December Tadeusz Mazowiecki was elected Prime Minister. One of the greatest sources of support for the opposition movement to the communist regime was the Polish Catholic Church, especially after the visit to Poland in 1979 by the former archbishop of Krakow, Karol Wojtyla, who was Pope John Paul II by then.

When the strike led by Walesa broke out the following year in the Lenin shipyards in Gdansk, the movement that would give rise to Solidarity with ten million members, owed as much to the importance of the Catholic Church in Polish society as to the unique alliance of intellectuals and workers that had put together the Workers’ Defense Committee, after both sides, in 1968 and 1970, had lived through the bitter experience of isolation in their respective confrontations with the regime (Friszke, p. 11). In 1990, Wojciech Jaruzelski left office, and Lech Walesa was elected as the new president in December with the direct votes of the Polish people.

The successful transition to democracy in a country without a democratic tradition made the Republic of Korea one of the more interesting cases of democratic transition among the countries that have undergone the transition to democracy as part of the third wave of global democratization. Historically, despite the trappings of democratic politics during the First Republic, the rather abrupt establishment of a democratic government without significant participation by the South Koreans themselves in 1948 created a superficial character in the representational side of the process (Dziak, Strnad, p. 44-52). The disillusionment with the Rhee Syngman presidency led, in 1960, to a new constitution which provided for a parliamentary form of government with a bicameral National Assembly. With the explicit goal of developing a democratic system that would prevent the abuses of power experienced during the Rhee administration, the new constitution greatly reduced the role of the president while expanding individual freedoms of assembly

and association (Kim, p. 41). The experiment of the Second Republic ended in 1961, replaced by a military junta led by Major General Park Chung Hee, ushering in an extended period of strong military influence in South Korean politics. After a nearly two-year period of transition under the control of a military junta led by Park, the Third Republic was established in 1963. A new constitution with a strong presidential system and a weakened National Assembly was adopted through national referendum. By the end of the 1960s, with Park taking full credit for a rapidly growing economy, a national referendum was held to approve an amendment to the constitution to allow for a third presidential term (Park, p. 110-115). In 1971, Park won the presidential election over Kim Dae-Jung, who was portrayed by the Park campaign as being ‘pro-Communist’. However, the relatively close margin of victory (53.2 to 45.3 percent) was at least a partial motivation for Park to insulate himself, in the name of national security, from ever facing elections again. In October 1972, Park declared martial

law, dissolved the National Assembly, banned political parties and closed all national universities and colleges in the name of “developing democratic institutions best suited for Korea”. Following the declaration of martial law, the constitution was again amended and ratified through a national referendum. The new constitution, which was referred to as Yushin (revitalization), ushered in the Fourth Republic and a new era of repression in which Park became increasingly isolated and indifferent to criticism of the government. By 1979, when Park was assassinated by his KCIA director, the country was once again being torn apart by violent street demonstrations led by students but increasingly supported by a rapidly growing middle class (Dziak, Strnad, p. 145-147). When Park died, there was no viable mechanism to replace him. Therefore, it is not surprising that despite an attempt by the interim government to revise democratic processes and eliminate the more draconian measures of the Yushin system, another military junta, this time led by General Chun Doo Hwan, took control of the central government in the name of ensuring national security. Once again, martial law was declared in the spring of 1980. This resulted in the May 18 Democratic Uprising in the city of Kwangju, which was put down by the New Military. During martial law, the National Assembly was dissolved, and political parties were banned for nearly a year while a new constitution was developed to serve as the basis for the Fifth Republic. With the new constitution completed, a newly formed electoral committee elected Chun as president for a seven-year term and National Assembly elections were held in 1981. In many respects, Chun’s tenure was a shortened replay of the Park era in that the government maintained tight control over both economic development through the conglomerate patronage system and was highly repressive in its attempts to control an increasingly large segment of the population that was resorting to street demonstrations (Suh, p. 109). In the absence of a meaningful system for aggregating political demands, the newly expanded middle class was

more willing to support increasingly violent demonstrations by students and labor unions. One important difference was that from the beginning Chun promised to work towards a peaceful transfer of power at the end of his tenure. Despite attempts by Chun to create a party system that would ensure the ruling party would retain power after the transition, by 1985 the opposition party, the New Democratic Party, led by Kim Dae-Jung and Kim Young-Sam, was receiving impressive levels of public support. Ultimately, emboldened by growing pressure from assertive street protests during June 1-29, 1987, which became known as the June Democratic Struggle, Chun and his handpicked successor and military academy classmate Roh Tae-Woo recognized the need for change. On June 29, 1987, Roh Tae-woo promised to institute direct presidential elections, among other initiatives; this is considered the defining moment in the transition. Indeed, with its spectacular economic growth under the authoritarian regimes of Park Chung Hee and Chun Doo Hwan in the 1970s and 1980s followed by the increase in civil protest supported by the new middle class, South Korea served as a textbook example of the economic preconditions theory of democratic transition. South Korea also represented a classic case for those interested in the cultural aspects of democratic transitions (Im p. 7-8). A new constitutional amendment was ratified by the National Assembly on October 12, 1987, and was submitted to a referendum to the South Korean public on October 27. 93% of voters cast ballots in favor of the amendment, which permitted the direct, democratic election of the President of South Korea. The presidential election was held in South Korea on December 16, 1987. This led to the democratization of the country and the establishment of the Sixth Republic under Roh Tae-woo, ending the military dictatorship that had ruled the country since 1981. Roh won the election with 37% of the vote; voter turnout was 89.2%. The transplacement of ruling authoritarian regimes with democratic systems in both Poland and the Republic of Korea share some

interesting similarities: growing demands and assertiveness of civil society, periods of heavy-handed repression followed by liberalization on the part of the authoritarian governments, and finally, negotiated pacts or agreements between

z Brzechczyn Krzysztof, Transformation, Post-communism, and the Deficiencies of Liberal Democracy in Poland: A Case Study, in: Post-communism, Democracy, and Illiberalism in Central and Eastern Europe after the Fall of the Soviet Union, edited by Daniela Popescu and Matei Gheboianu, Publisher: Lexington Books, 2023.

z Dabertowa Eugenia R., Lenartowski, Pomnik Poznańskiego Czerwca 1956: symbol pamięci i sprzeciwu, Komisja Zakładowa NSZZ Solidarność - H. Cegielski, 1996.

z Dziak Waldemar, Strnad Grażyna, Republika Korei. Zarys ewolucji systemu politycznego, Instytut Studiów Politycznych IPN, Warszawa 2011.

z Friszke Andrzej, Delegalizacja Solidarności i uwolnienie Lecha Wałęsy, IPN “Wolność i Solidarność” nr 9 / 2016.

z Gomułka Stanisław, Transformacja gospodarczo-społeczna Polski 1989-2014 i współczesne wyzwania, „NAUKA” 3/2014.

z Hwang Sok-Yong , Lee Jae-Eui , Jeon Yong-Ho, Gwangju Uprising. The Rebellion for Democracy in South Korea, Verso 2022.

z Im Hyug-Baeg, Politics of Transition: Democratic Transition: from Authoritarian Rule in South Korea, University of Chicago, 1989.

the government and the opposition. Despite the challenges through time, both countries have retained their democratic institutions established after transition.

z Jankowiak Stanisław, Sytuacja społeczno-polityczna w Wielkopolsce w pierwszej połowie lat pięćdziesiątych na tle sytuacji w kraju, w: Poznański Czerwiec 1956 Uwarunkowania – Przebieg – Konsekwencje, pod. Red. Konrada Białeckiego, Stanisława Jankowiaka, Instytut Historii UAM, Poznań 2007.

z Katsiaficas Georgy, Na Kahn-Chae, South Korean Democracy. Legacy of the Gwangju Uprising, Routledge, 2013.

z Kim Choong-Nam, The Korean Presidents. Leadership for Nation Building, EastBridge, Norwalk, CT 2007.

z Kowalski Mariusz, Wybory parlamentarne 1989, w: M. Kowalski, P. Śleszyński (red.), Atlas wyborczy Polski, Instytut Geografii i Przestrzennego Zagospodarowania PAN, Warszawa, https://rcin.org.pl/igipz/ Content/208634/PDF/WA51_242235_ PANB5061-r2018_Wybory-parlamentarne-1989.pdf.

z Kwilecki Andrzej, Poznański Czerwiec 1956-2006, Pamięć i Tradycja, w: Poznański Czerwiec 1956 Uwarunkowania – Przebieg – Konsekwencje, pod. red. Konrada Białeckiego, Stanisława Jankowiaka, Instytut Historii UAM, Poznań 2007.

z Łuczak Agnieszka, Poznański Czerwiec 1956, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej – Archiwum, file:///C:/Users/Dell/

Downloads/Agnieszka-Luczak-Poznanski-Czerwiec-1956.pdf (dostęp: 12.08.2025).

z Makowski Edmund, Poznański Czerwiec 1956 — pierwszy bunt społeczeństwa w PRL, Wydawnictwo Poznańskie Poznań 2001.

z Musiał Filip, 30 rocznica wyborów 4 czerwca 1989 r. – Słodko-gorzki smak zwycięstwa, IPN Oddział w Krakowie, 2019, file:///C:/Users/Dell/Downloads/30__ rocznica_wyborow_4_czerwca_1989_roku. pdf

z Park Chung-He, To Build the Nation, Acropolis Books, NewYork 1971.

z Plunk Daryl M., South Korea’s Kwangju Incident Revisited, “Asian Studies Backgrounder” No. 35, 16 September 1985.

z Rybak Bartosz, Reczek Rafał, Dokumentacja archiwalna dotycząca Powstania Czerwcowego – Przegląd materiałów wypożyczonych z OBUiAD w Warszawie, w:

Poznański Czerwiec 1956 Uwarunkowania – Przebieg – Konsekwencje, pod. Red. Konrada Białeckiego, Stanisława Jankowiaka, Instytut Historii UAM, Poznań 2007.

z Strnad Grażyna, Południowokoreańska droga do demokracji, Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałęk, Toruń 2010.

z Strnad Grażyna, Korea. Polityka Południa wobec Północy w latach 1948-2008. Zmiana i kontynuacja, Instytutu Zachodni, Poznań 2014.

z Suh Dae-Sook, South Korea in 1981: The First Year of the Fifth Republic, “Asia Survey” Vol. 22, No.1, January 1982.

z Zieliński Zygmunt, Polityczne i kościelne ramy życia i działalności arcybiskupa Antoniego Baraniaka, “Ecclesia. Studia z Dziejów Wielkopolski”, tom. 2, 2006.

Sylwia Szyc, Ph.D.

The Historical Research Office

The Institute of National Remembrance – Commission for the Prosecution of Crimes against the Polish Nation (IPN)

At the end of the 1980s, Poland embarked on a path of significant political and economic transformation, leading to a peaceful transition from a communist system with a centrally planned economy to a democracy and a free market. This process demonstrated that profound systemic change is possible through negotiation and social compromise, without resorting to violence. However, this transformation came with severe social and economic costs that have shaped the experiences of Poles for decades, with consequences that are still felt today.

The report outlines the origins and progression of Poland’s systemic transformation—from the debt crisis of the 1970s, through the rise of “Solidarity” and the period of martial law, to the Round Table negotiations and the reforms of 1989. The aim is not only to analyze these events within the context of Polish history but also to assess what lessons and experiences might be valuable for the potential process of Korean reunification, taking into account the different political, economic, and cultural realities.

KOREAN UNIFICATION FROM A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE

LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

In December 1970, following the violent suppression of workers’ protests on the Coast and the resignation of Władysław Gomułka 1, Edward Gierek replaced him as the First Secretary of the Polish United Workers’ Party (PZPR). He announced his vision for “the second Poland”—a modern and prosperous nation that prioritized improved quality of life, increased consumption, and industrial modernization. This ambitious plan was primarily financed through loans from Western countries, along with the importation of technology and affordable raw materials from the USSR. The prevailing policy of détente in East-West relations helped facilitate this strategy, although the assessment of Poland’s creditworthiness was rather superficial 2 .

The early 1970s in Poland saw an improvement in living standards, marked by housing development, greater availability of previously scarce goods, and expanding infrastructure. The slogan “for Poland to grow stronger and for people to live more prosperously” captured the optimism of the early Gierek era. Rapid growth in consumption and investment suggested that Poland was beginning to catch up with Western

countries. However, much of this growth was financed through debt directed at consumption and low-yield investments, while the centrally planned economy struggled with low productivity, inefficiency, and inflexibility 3 .

The economic situation deteriorated during the crises of the 1970s, particularly the 1973 oil shock and rising interest rates. Debt servicing costs surged, and access to new credit became limited, creating a debt trap. Reform attempts, such as the 1976 price increases, triggered widespread social unrest, culminating in strikes and protests 4

In October 1978, Polish Cardinal, Karol Wojtyła, was elected Pope, taking the name John Paul II. His election was unexpected by the communist authorities and increasingly alarming, as a fellow Pole with immense moral authority now led the Catholic Church in a country where religion played a central societal role. John Paul II quickly became a symbol of hope and spiritual support for millions, challenging the party’s ideological monopoly and strengthening oppositional sentiment.

The decade also brought significant ideologi-

1. See also: Zbigniew Branach, Grudniowe wdowy czekają (Wrocław: Europa, 1990); idem, Pierwszy grudzień Jaruzelskiego (Torun: Agencja Reporterska „Cetera”, 1998); Grudzień 1970 w dokumentach MSW, selection, introduction, and ed. J. Eisler (Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2000); Bogumiła Danowska, Grudzień 1970 roku na Wybrzeżu Gdańskim. Przyczyny – przebieg – reperkusje (Pelplin: Wyd. Diecezji Pelplińskiej „Bernardinum”, 2000); Andrzej Głowacki, Kryzys polityczny 1970 roku (Warszawa: Instytut Wydawniczy Związków Zawodowych, 2000); Jerzy Eisler, Grudzień 1970. Geneza, przebieg, konsekwencje, 2nd ed. (Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2012).

2. Aleksandra Komornicka, Poland and European East-West Cooperation in the 1970s: the opening up (London–New York: Routledge, 2024), 44, 56-61.

3. See also: Andrzej Karpiński, “Drugie uprzemysłowienie Polski – prawda czy mit?,” in Dekada Gierka. Wnioski dla obecnego okresu modernizacji Polski, ed. K. Rybiński (Warszawa: Uczelnia Vistula, 2011), 13–26; Paweł Bożyk, “Cywilizacyjne skutki ‘otwarcia’ Polski na Zachód,” in Dekada Gierka..., 5–12.

4. Paweł Sasanka, Czerwiec 1976. Geneza – przebieg – konsekwencje (Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2006).

cal shifts. A new generation of communists, shaped by post-war realities and more focused on pragmatic governance than revolutionary ideals, rose to positions of leadership. Simultaneously, Marxism-Leninism’s role as a legi-

timizing ideology diminished. Bureaucratization, entrenched social inequalities, and the gap between propaganda and everyday experience further eroded the appeal of the official ideology5 .

In 1980, in response to a severe economic crisis and rising prices, Poland experienced a wave of strikes, the most significant of which took place at the Lenin Shipyard in Gdańsk 6 . The workers put forward demands that included not only economic issues, such as wage increases, but also political demands. These included the right to create independent trade unions free from government control, the right to strike, freedom of speech and assembly, and the release of political prisoners 7. The prospect of a general strike became increasingly apparent.

A pivotal development was the creation of the Inter-Enterprise Strike Committee in Gdańsk, which brought together over 250 workplaces and approximately 700,000 workers nationwide 8. At its head stood the charismatic leader Lech Wałęsa.

On August 29, 1980, during a meeting of the Political Bureau, the I Secretary of the Central Committee of the PZPR, Edward Gierek, acknowledged that in this situation “one must choose the lesser evil and then try to get out of it.” 9. The party leadership was aware of the seriousness

WAŁĘSA’S SPEECH, AUGUST 1980: SOURCE: SOLIDARITY AUGUST 1980 GATE OF GDAŃSK, WIKIPEDIA: HTTPS://PL.WIKIPEDIA.ORG/WIKI/WYBORY_ PARLAMENTARNE_W_POLSCE_W_1989_ROKU#/MEDIA/ PLIK:WYBPAR1989.JPG

5. Samuel P. Huntington, The Third Wave: Democratization in the Late Twentieth Century (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 48.

6. See: Andrzej Paczkowski, Droga do „mniejszego zła”. Strategia i taktyka obozu władzy lipiec 1980‒styczeń 1982 (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2002), 20–62; Anna Machcewicz, Bunt. Strajki w Trójmieście. Sierpień 1980 (Gdańsk: Europejskie Centrum Solidarności, 2015).

7. Krzysztof Brzechczyn, Umysł solidarnościowy. Geneza i ewolucja myśli społeczno-politycznej „Solidarności” w latach 1980-1989 (Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance, 2022), pp. 113–.

8. Tomasz Kozłowski, Anatomia rewolucji. Narodziny ruchu społecznego „Solidarność” w 1980 roku (Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2017), 425.

9. Zbigniew Włodek, ed., Tajne dokumenty Biura Politycznego. PZPR a „Solidarność” 1980–1981 (London, 1992), 84.

KOREAN UNIFICATION FROM A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

of the threat to maintaining its power, and the “lesser evil” became accepting the strike demand for the creation of independent trade unions. This solution was also tacitly accepted by Moscow 10 .

On August 31, 1980, the Gdańsk Agreements were signed, leading to the creation of the Independent Self-Governing Trade Union “Solidarity” (NSZZ

The decision to choose the “lesser evil” placed the party authorities in a particularly challenging position. The actions of Solidarity were incompatible with the monopoly held by the PZPR, creating ongoing tensions and undermining the foundation of the existing political order. From the authorities’ perspective, maintaining the status quo required neutralizing Solidarity and reestablishing complete regime control over political and social life.

The domestic situation was further complicated by economic difficulties. By 1981, Poland’s foreign debt had reached levels beyond its repayment capacity, effectively forcing the state to suspend payments to foreign creditors—Poland was, in effect, bankrupt. In 1980, the debt was around $24 billion. In response to the crisis, negotiations with Western creditors were initiated to defer repayment schedules 12

The Soviet Union was determined to prevent events in Poland from spiraling out of control.

Solidarność), the first mass organization in the Eastern Bloc independent of the communist party11. The union quickly gained immense social support, reaching around 10 million members at its peak, including individuals previously associated with the state apparatus.

Moscow exerted political and economic pressure on Warsaw, employing a range of measures— from threatening military intervention and supporting pro-Soviet factions within the PZPR to restricting the supply of raw materials and financial aid. Crucially, the Kremlin’s goal was to compel the Polish authorities to suppress Solidarity and stabilize the country through their own actions, without direct Soviet military involvement, while ensuring that Poland’s political direction remained firmly aligned with Moscow’s interests 13 .

In February 1981, General Wojciech Jaruzelski became Prime Minister while also serving as Minister of National Defense and, starting in October, as First Secretary of the PZPR Central Committee. Under intense pressure from Moscow, the Polish authorities imposed martial law during the night of December 12-13, 1981. Military units were deployed in cities, a curfew was enacted, and thousands of oppo-

10. A. Paczkowski, Wojna polsko-jaruzelska. Stan wojenny, czyli kontrrewolucja generałów (Warszawa: Wielka Litera, 2021), 45-46.

11. The literature on NSZZ “Solidarność” is extensive; see among others: NSZZ „Solidarność” 1980–1989, vols. 1–7, ed. Ł. Kamiński, G. Waligóra (Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2010); Tomasz Kozłowski, Anatomia rewolucji. Narodziny ruchu społecznego „Solidarność” w 1980 roku (Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2017); Marcin Zaremba, Wielkie rozczarowanie. Geneza rewolucji Solidarności (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak Horyzont, 2023).

12. Maciej Bałtowski, Gospodarka socjalistyczna w Polsce (Warszawa: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN, 2009), 243.

13. The economic forms of Soviet pressure on Poland in 1980–1981 are analysed in detail in Tomasz Kozłowski, „Banki groźniejsze niż tanki”. Mechanizmy gospodarczego nacisku Związku Sowieckiego na Polskę (1980–1981), Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość 40, no. 2 (2022): 487–507.

sition activists were interned 14 . Internationally, Poland faced economic and political sanctions from Western nations, further deepening the crisis. Solidarity was initially suspended and later outlawed, although some activists continued underground activities, albeit with diminished social support 15. Society, exhausted by declining living standards, experienced a sense of stagnation and hopelessness, which weakened participation in opposition movements.

While martial law temporarily enabled the authorities to regain control, Poland’s economic situation continued to worsen. Industrial production steadily declined, and inflation rose significantly. Typically, these trends would trigger strong social unrest. However, martial

law allowed the authorities to implement price increases, including a roughly 2.5-fold rise in food prices. Although minimum wages were partially increased, real wages fell by about 25%.

Martial law temporarily subdued social resistance and restored government control, but it did not solve Poland’s economic or political problems. Worsening living conditions and repressive measures weakened opposition activity and deepened public distrust of the regime. When martial law was lifted in July 1983, the country remained in crisis, with growing social and political tensions that would once again bring the authorities into conflict with the opposition in the following years.

In the 1980s, the Soviet Union was sinking deeper into an escalating economic crisis, further exacerbated by the 1986 oil market crash, which deprived the state of a significant portion of its revenues. After assuming the position of General Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union in March 1985, Mikhail Gorbachev initiated a process of limited reforms in the USSR, conducted under the banners of glasnost (openness), perestroika (restructuring), and uskorenie (acceleration).

A key element of the new policy was the decision to reduce economic aid to satellite states, so as not to further burden the Soviet economy, already in

recession. In return, Moscow allowed individual countries the possibility of implementing their own economic reforms, while simultaneously emphasizing the need to maintain close political and economic ties within the Eastern Bloc. At the same time, the Kremlin gradually moved away from the Brezhnev Doctrine, limiting the possibility of direct military interventions in bloc countries. Instead of military threats, measures such as tension de-escalation, improvement of relations with the West, and economic pressure— used as a form of leverage over allies—became more common 16 .

The year 1986 is often regarded as a symbolic beginning of the communist system’s collapse in

14. More about martial law in Poland (1981-1983). See: Andrzej Paczkowski, Wojna polsko-jaruzelska. Stan wojenny, czyli kontrrewolucja generałów, Wielka Litera, Warszawa 2021; Antoni Dudek, „Obóz władzy w okresie stanu wojennego,” Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość 2 (2002): 236–239.

15. A. Dudek, Reglamentowana rewolucja. Rozkład dyktatury komunistycznej w Polsce 1988-1990 (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Znak Horyzont, 2014), 54.

16. T. Kozłowski, „Laboratorium pierestrojki? Generał Jaruzelski na geopolitycznej szachownicy,” Polska 1944/45–1989. Studia i Materiały 20 (2022): 219-244.

KOREAN UNIFICATION FROM A EUROPEAN PERSPECTIVE

LESSONS FROM POLAND AND EUROPE SUPPORTING KOREA IN ITS PATH TOWARDS UNIFICATION

Poland. According to Lech Wałęsa, leader of Solidarity, that year “(…) in many ways emerged as a time of breakthrough. The authorities still, of course, bared their teeth, but numerous signs of decay were already visible in them.” 17 .

Amnesty was granted to some political prisoners, a Consultative Council and the office of the Ombudsman were established. In November 1987, a nationwide referendum was held on economic reforms, which included greater enterprise autonomy, the development of commercial banking, and the issuance of bonds 18 . This represented an attempt to introduce elements of a market economy into a centrally planned

system. The West applied conditional financial pressure on Poland, conditioning debt renegotiation and the granting of new loans on steps toward democratization of political life 19 .

The authorities deliberately liberalized certain areas of social life, such as allowing Western films in cinemas and on television and relaxing social norms, in order to reduce tensions and divert citizens’ attention from economic problems 20 Additionally, travel abroad—for work, tourism, and so-called “tourist trade”—was facilitated, improving the material situation of many families and acting as a “safety valve” for the system 21

In 1987, part of the leadership of the PRL increasingly raised alarms about growing social tensions and the catastrophic economic situation, whose real indicators were far worse than those reported in earlier reports, potentially leading to the “collapse of the current leadership team.” 22 . A package of radical economic and political reforms was seen as a way to prevent the impending crisis. Despite mounting pressure, General Jaruzelski delayed making key decisions 23 .

The situation was somewhat stabilized by a balance of power between the communist authorities and the opposition. Neither side

possessed enough strength to seize full control, which allowed the ruling authorities primarily to maintain the status quo and left room for negotiations 24 . The opportunity for this arose the following year.

On February 1, 1988, the communist authorities introduced the largest price increase since 1982, including a 60% rise in food products. Although citizens were offered partial financial compensation, this did not prevent a surge of social discontent. It is worth noting that at the time, Poland was one of the poorest countries in Europe, with the purchasing power of the average Pole amounting to only one-third of that of a German

17. Lech Wałęsa, Droga do wolności (Warszawa: Editions Spotkania, 1991), 50.

18. Paweł Kowal, Koniec systemu władzy. Polityka ekipy gen. Wojciecha Jaruzelskiego w latach 1986-1989, (Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, Instytut Studiów Politycznych PAN, Wydawnictwo TRIO 2012), 89-95.

19. Patryk Pleskot, Kłopotliwa panna „S”. Postawy polityczne Zachodu wobec „Solidarności” na tle stosunków z PRL (1980–1989), (Warszawa: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2013); Andrzej Paczkowski , Od sfałszowanego zwycięstwa do prawdziwej klęski. Szkice do portretu PRL, (Kraków: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 1999),135–136.

20. P. Kowal, Koniec systemu władzy, 141-146.

21. Dariusz Stola, “Migracje zagraniczne i schyłek PRL,” in Społeczeństwo polskie w latach 1980-1989, ed. N. Jarska, J. Olaszek (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2015), 65-66.

22. A. Dudek, Reglamentowana rewolucja, 87-89.

23. Daria Nałęcz and Tomasz Nałęcz, Czas przełomu, 1989-1990 (Warsaw: Polityka, 2019), 19. 24. Ibidem.

citizen. Polish incomes were also lower compared to other Eastern Bloc countries, with GDP per capita amounting to only half of that in Czechoslovakia 25 .

In the spring and summer of 1988, two waves of strikes swept across Poland. Although not as large as those in 1980, the authorities feared the outbreak of even bigger protests. This situation forced the PZPR leadership to shift its strategy— from confrontation to seeking an agreement with the opposition. Still, questions remained about the scope of concessions and the future role of the opposition in the political system of the PRL.

As Antoni Dudek emphasizes: “The sense of pervasive stagnation and helplessness battled in the minds of PZPR officials with the fear of a forthcoming large social uprising and entirely real layoffs. In such an atmosphere, despite constant resistance and the perception of no real personal or political alternative to Jaruzelski’s team, the party apparatus drifted toward accepting the controlled transformation scenario promoted by the general’s advisors. The political passivity of PZPR functionaries became—alongside the profit-oriented economic activity of some of them— one of the most significant factors accelerating the disintegration of the PRL political system.” 26 .

The talks in Magdalenka, which began in September 1988, served as an unofficial prelude to future negotiations between the PRL authorities and the opposition centered around “Solidarity.” These meetings, held in a small circle of representatives from both sides, helped overcome mutual distrust and discuss key issues for the later negotiations. They addressed the need for economic reforms, the re-legalization of “Solidarity,” and changes to the electoral system. The

authorities sought a way to implement reforms while retaining full control, while the opposition saw the talks as an opportunity to regain legal status and begin the process of democratizing the country. The Catholic Church acted as a catalyst and mediator, bridging both sides and helping to establish preliminary compromises, laying the groundwork for the subsequent Round Table negotiations 27 .

From February 6 to April 5, 1989, the Round Table talks took place in Warsaw. The name derives from the shape of the table, at which representatives of the communist authorities, “Solidarity,” social organizations, and the Catholic Church as mediator sat. The setup was meant to symbolize equality among all parties.

The talks were conducted in three main teams: for political reforms, economic reforms, and trade union pluralism. Key agreements included the re-legalization of “Solidarity” and the establishment of partially free elections to the Sejm and fully free elections to the Senate. It was also agreed to create the office of President of the PRL and implement economic reforms, involving a gradual transition to a market economy 28 .

The agreement reached in the spring of 1989 did not satisfy everyone, drawing criticism from both the ruling apparatus and radical opposition groups, some of which called for a boycott of the upcoming elections 29. Pragmatic considerations, however, led the opposition to see the results of the Round Table talks as opening previously unavailable opportunities—an opportunity to play for winning cards.

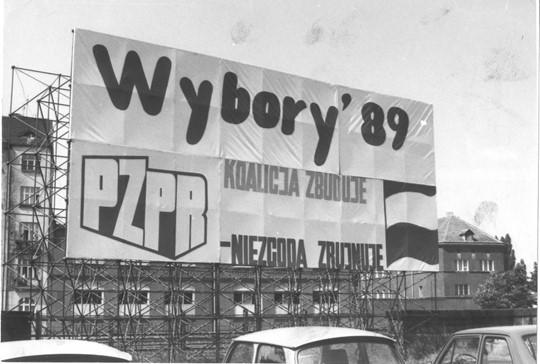

The elections were scheduled for June 1989. According to the adopted electoral law, the op-

25. Marcin Piątkowski, Europejski lider wzrostu. Polska droga od ekonomicznych peryferii do gospodarki sukcesu (Warsaw: Poltext, 2019), 160.

26. A. Dudek, Reglamentowana rewolucja, 179.

27. Ibidem, 153-156; Jan Skórzyński, Revolution of the Round Table (Kraków: Znak, 2009), 163–169.

28. See more: Andrzej Garlicki, Karuzela. Rzecz o Okrągłym Stole (Warsaw: Czytelnik, 2004); Jan Skórzyński, Revolution of the Round Table (Kraków: Znak, 2009), 267-348; Paulina Codogni, Okrągły Stół, czyli polski Rubikon (Warsaw: Prószyński i S-ka, 2009).

29. P. Kowal, Koniec systemu władzy, 467-482.

ELECTION ADVERTISEMENT OF THE PZPR DURING THE ELECTION CAMPAIGN,

SOURCE: REKLAMA WYBORCZA PZPR W TRAKCIE KAMPANII WYBORCZEJ, WIKIPEDIA: HTTPS://PL.WIKIPEDIA.ORG/WIKI/WYBORY_PARLAMENTARNE_W_POLSCE_W_1989_ROKU#/MEDIA/PLIK:WYBPAR1989.JPG

position could compete for 35% of the Sejm seats and all seats in the newly created Senate. The results of the first round on June 4 were devastating for the PZPR—opposition candidates won almost all available seats, and many prominent communist activists were defeated 30

The agreements made at the Round Table and the discussions in Magdalenka established three key safeguards within the system: a parliamentary majority for the PZPR and its allies, which

ensured their control over the government; the election of the president by a majority vote in the National Assembly; and oversight of the military and police. However, the June 1989 elections cast doubt on the majority needed to elect General Jaruzelski as president and made it impossible to form a government led by the PZPR.

In July 1989, the National Assembly elected General Wojciech Jaruzelski as President of the PRL. This was a compromise resulting from the Round Table talks, intended to ensure stability during the transitional period. Although Jaruzelski initially hesitated to accept the nomination 31, his election was supported by both the United States and the Soviet Union, who feared destabilization of the country and the potential for intervention. The White House was concerned that the sudden removal of the entire existing political elite could destabilize the situation. The Soviets allowed limited reforms in Poland, while the United States was uncertain about the limits of its tolerance. The Americans shared the view of some “Solidarity” activists that “if Jaruzelski is not elected president, there is a genuine threat of civil war, which would likely end with a reluctantly but brutally executed Soviet intervention.” 32 . Gorbachev also believed that keeping the current leader in place would bring more benefits than risks. Jaruzelski’s election was therefore part of a transitional political period. He served as president until the end of 1990, when his term ended with the election of Lech Wałęsa in the first fully democratic presidential elections.

According to the agreements, the prime minister was to come from the existing government, but the candidacy of General Czesław Kiszczak 33 faced strong opposition from the opposition. After negotiations, a compromise was reached under the slogan “Your president, our prime minister.” As a result, on September 12, 1989, a government was formed with Tadeusz Mazowiecki, a close associate of Lech Wałęsa, as its head. This was the first cabinet in the Eastern Bloc led by an opposition politician. Mazowiecki’s government included representatives of both “Solidarity” and the PZPR, though the communists retained control over key security ministries34 .

The defeat in the June elections led to a political deadlock within the PZPR. Deprived of popular support, the party lost influence, and its attempts to maintain unity failed. In January 1990, the PZPR was officially dissolved, ending forty years of political dominance 35

However, this did not mean the complete disappearance of post-communists from political life. Many of them established the Social Democracy of the Republic of Poland (SdRP), which took over the assets and structures of the former party. SdRP later became the core of the Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), which, thanks to efficient

31. Ibidem, 320-321.

32. Ibidem, 326.

33. Czesław Kiszczak was a communist activist and close collaborator of General Jaruzelski. From July 31, 1981, to July 6, 1990, he served as the Minister of Internal Affairs.

34. A. Dudek, Od Mazowieckiego do Suchockiej. Pierwsze rządy wolnej Polski,(Kraków: Znak Horyzont, 2019), 29-51.

35. Andrzej Boboli, Martwe dusze. PZPR od czerwca 1989 do stycznia 1990. Próba opisu zbiorowości (Warsaw: Institute of National Remembrance, 2024).

organization and recognizable leaders such as Aleksander Kwaśniewski, regained significant influence, symbolized by Kwaśniewski’s victory in the 1995 presidential elections.

Poland’s economic transformation involved two main stages of reforms. The first step was the so-called Wilczek Act 36 of December 23, 1988 (still during the PZPR period), which introduced the principle “what is not forbidden is allowed,” enabling free enterprise and liberalizing trade.

The second, more radical stage of reforms was the plan introduced by Leszek Balcerowicz, Deputy Prime Minister and Finance Minister in Mazowiecki’s government, on January 1, 1990. The plan aimed to rapidly transform the centrally planned economy into a market-based one. Key measures included: liberalization of prices, which eliminated shortages in stores but caused a sharp rise in inflation; restrictive monetary policy, which stabilized the złoty, trade liberalization, opening the economy to foreign capital and privatization of state-owned enterprises.

Alongside economic reforms, political changes were implemented. In December 1989, the national emblem with the crowned eagle was restored, and the country’s name was changed to the Republic of Poland. References to the leading role of the PZPR were removed from the constitution. In 1990, the first free local elections took place, followed by the first fully free parliamentary elections in 1991, which definitively confirmed the democratic nature of the state.

The enthusiasm for political freedom soon mixed with economic uncertainty. Public opinion became sharply divided—supporters of reforms emphasized their necessity and lack of alternatives, while opponents criticized their radicalism and social costs. This division influenced political moods in the early years of the Third Republic, contributing to a weakening of support for the “Solidarity” camp by the mid-1990s.

The transformation of the communist Security Service (SB) after 1989 was a highly controversial process. In the face of the system’s collapse, officers systematically destroyed documents to conceal evidence of their crimes and the extent of surveillance. Many also removed files from archives, treating them as material for blackmail or as an “insurance policy” for the future – one such file concerned Lech Wałęsa’s alleged cooperation with the SB.

A key element of the changes was the vetting of SB officers who wished to serve in the newly established Office for State Protection (UOP). This process, intended as a symbolic break with the repressive apparatus, ultimately resulted in a significant portion of the old cadre being admitted to the new services. After appeals were considered, 10,439 out of over 14,000 applicants passed the vetting, representing nearly 75% of all former SB candidates 37

36. Mieczysław Wilczek served as Minister of Industry in Mieczysław Rakowski’s government from 1988 to 1989.

37. Tomasz Kozłowski, Koniec imperium MSW. Transformacja organów bezpieczeństwa państwa 1989–1990 (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2019), 87.

An integral part of dealing with the past was also lustration and the provision of archival access. It was not until 1998 that the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN) was established, tasked with collecting SB documents and conducting

lustration proceedings. Despite these measures, the debate over lustration and archive access remained heated for years, dividing both society and politicians.

The systemic transformation of the 1990s radically changed the daily lives of Poles. Shops began to offer goods that were previously unavailable, and public spaces filled with Western cars, advertisements, and symbols of pop culture. However, not everyone benefited equally from these changes – falling real incomes, rising prices, and growing inequalities worsened the living conditions for many families.

The costs of the reforms were particularly felt in smaller towns and rural areas, where the closure of unprofitable state enterprises led to a sharp increase in unemployment, fostering poverty and social exclusion 38. The 1990s also saw a rise in organized crime and the growth of the “grey economy,” which weakened budget revenues and complicated the stabilization of public finances. Although not directly caused by economic reforms, these negative phenomena were their side effects, deepening a sense of social chaos and uncertainty.

One significant problem of the transformation was the so-called “enfranchisement of nomenklatura”, a process in which former members of the communist elite or individuals connected to the party apparatus took over state assets on preferential terms. Thanks to the radical market reforms –especially privatization and deregulation – these individuals were able to exploit their influence and access to information to acquire substantial state-owned assets. Instead of creating an open and fair market, the transformation contributed to the emergence of a new, privileged economic group, which in turn deepened social inequalities and fostered a sense of injustice among citizens 39

38. More about the social costs of the political transformation. See: Piotr Sztompka, The Trauma of the Great Change: The Social Costs of Transformation (Warsaw: Institute of Political Studies, Polish Academy of Sciences, 2000); Elżbieta Mikuła, “Społeczny wymiar transformacji,” Nierówności Spoeczne a Wzrost Gospodarczy 2004, no. 4: 261–274; Katarzyna Duda, Kiedyś tu było życie, teraz jest tylko bieda. O ofiarach polskiej transformacji (Warsaw: Książka i Prasa, 2019).

39. Tomasz Kozłowski, ‘Appropriation Mechanisms: the Functioning of “Nomenklatura Companies” in the Period of Economic Transformation’, Pamięć i Sprawiedliwość, no. 2 (2020), 509–529.

The success of Poland’s systemic transformation was based on a combination of several key factors: the mass, pluralistic social movement of Solidarity, the pragmatism of political elites, the mediating role of the Church, and the willingness of both sides to seek compromise. At the same time, the transformation showed that any profound reform carries significant costs. Economic liberalization led to rapid growth but also to job losses in many sectors and a deepening of social inequalities. Similarly, the vetting of the security apparatus was selective and did not fully satisfy society’s demand for justice, demonstrating that even a successful transformation involves difficult compromises and challenges.

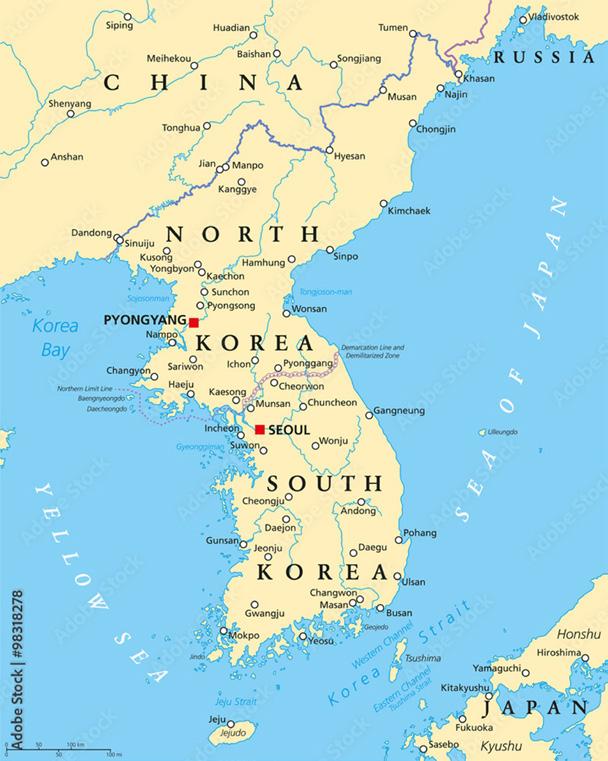

The potential reunification of the two Korean states involves challenges on a scale unprecedented in Central and Eastern Europe after 1989. Among the most serious are the vast economic and technological gap between North and South Korea, the need to integrate millions of people raised under radically different political and ideological systems, and the enormous social and financial costs of the unification process. This process is further complicated by regional security issues and the role of great powers whose geopolitical interests can both support and hinder reunification.

Poland does not serve as a direct model for Korea, but its experience can serve as a point of reference—highlighting proven mechanisms leading to stable change while warning against

potential risks and difficulties.

Despite the internal problems mounting since the 1970s, primarily rooted in the deteriorating state of the Polish economy, it was external rather than internal factors that accelerated Poland’s transformation process. Although the early 1980s saw escalating social unrest, waves of strikes, and revealed weaknesses of the authorities—who were forced to impose martial law—this was not yet a moment of systemic collapse. The Soviet Union remained the glue holding the status quo, ready for possible military intervention and applying various pressures that forced Polish authorities to take radical actions to maintain control. The United States, at this time, adopted a wait-and-see approach toward events in Eastern Europe. Only in the late 1980s, when the USSR became severely weakened economically and politically, and the West increasingly supported democratic processes, did real reforms become possible.

Analyzing the situation in the communist Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea, DPRK), it can be assumed that any systemic change will largely depend on the stance of the two largest powers in the region: China and Russia. Without at least partial consent or at least neutral tolerance from them, the process of Korean Peninsula unification will be extremely difficult to carry out. The chances of success might increase if one of these states weakens significantly, potentially destabilizing North Korea internally and creating space for political change.

At the root of Poland’s internal problems in the 1970s and 1980s lay a steadily deepening economic crisis, limited social system capacity, and rising social expectations. Openness to Western culture during the Gierek decade, along with independent information channels (for example, Radio Free Europe), helped foster greater civic awareness and gradual growth of oppositional attitudes.

In the DPRK, despite extremely low living standards and periodic famines such as the one from 1995–199940, there have been no mass social uprisings on a scale even remotely comparable to Poland’s experience. This results from a combination of extreme informational isolation, long-term indoctrination, and a broad repression apparatus based, among others, on collective responsibility that includes entire families of those deemed disloyal to the regime.

A significant element of Poland’s transformation was the presence of entities capable of mediating between the communist authorities and the opposition. The Catholic Church played a key role, enjoying considerable social support and—crucially—acceptance from both sides at the negotiating table. Within the PZPR, clear divisions existed between “liberals” willing to seek compromise and the so-called “hardliners” favoring a tough political line 41. The combination of these two factors—the presence of a mediator with strong political and moral authority and the existence of a reformist faction within the ruling structures—created conditions for gradually reaching an agreement.

In North Korea, there is no institution comparable to the Catholic Church in Poland, though informal divisions likely exist within the ruling

elite—for example, between technocrats focused on economic development and representatives of the Korean People’s Army who support the current regime’s direction. A potential factor encouraging some elites toward change might be an attractive economic offer similar to Poland’s “Wilczek reforms” of the late 1980s, which allowed parts of the ruling apparatus to enter the market economy legally and gain privileges and wealth in the new reality.

The role of the military differs fundamentally in both cases. In Poland, the army was an instrument of the party and did not act as an independent political actor after 1989. In North Korea, however, the military is a pillar of power, enjoying significant autonomy. The “army first” doctrine (Songun), established by the North Korean regime not only in response to the mid-1990s economic crisis but also to dynastic changes following the death of Kim Il Sung, when Kim Jong Il assumed power, granted the military the status of regime guardian 42 . The military was essential for consolidating his political position, meaning that any attempts at transformation will require its involvement and guaranteed status in the new political and economic order. Without such guarantees, attempts to block reforms by force could occur.