O L V M E

of the

of A R C A N E W O R K S

known as

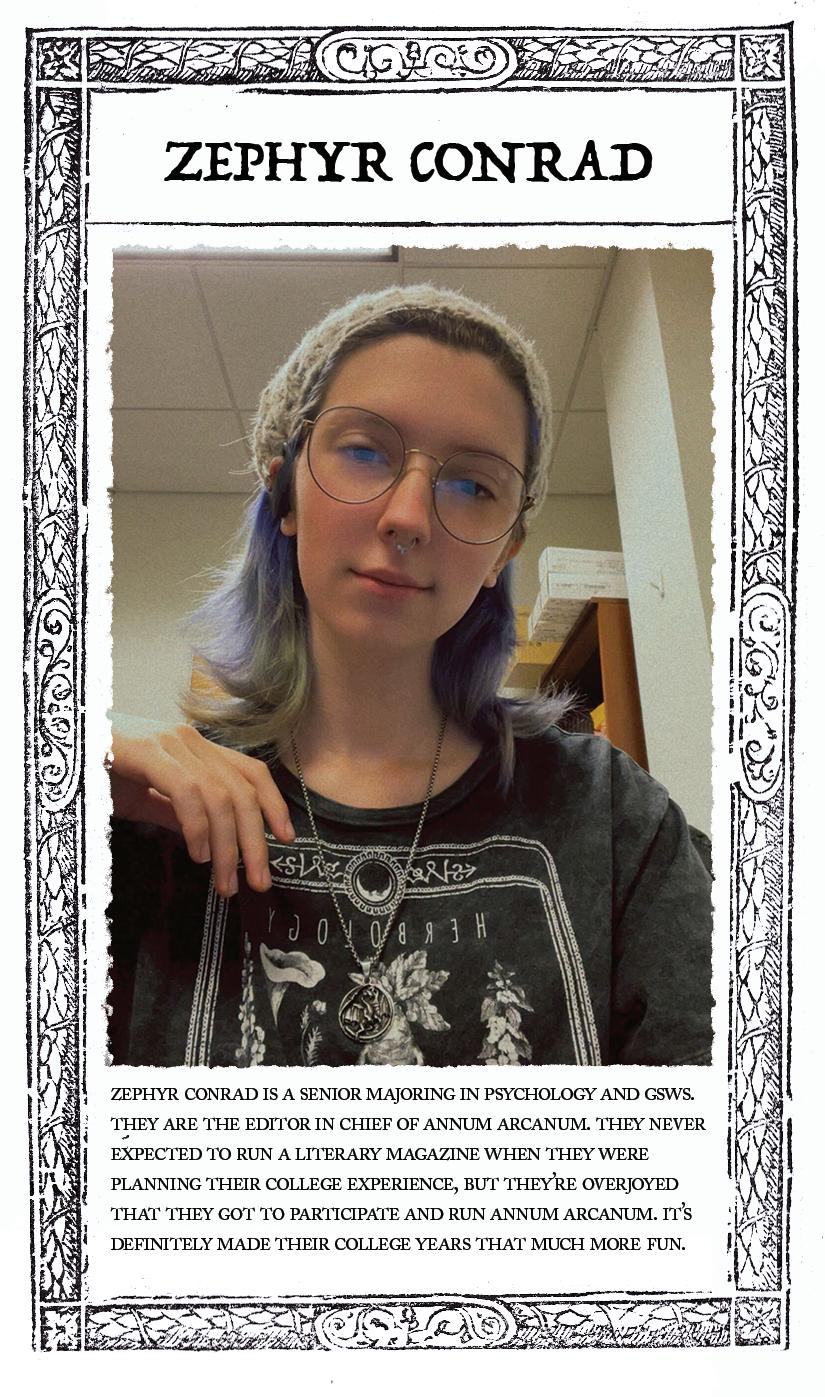

editor in chief zephyr conrad

editor of prose wyatt unrue

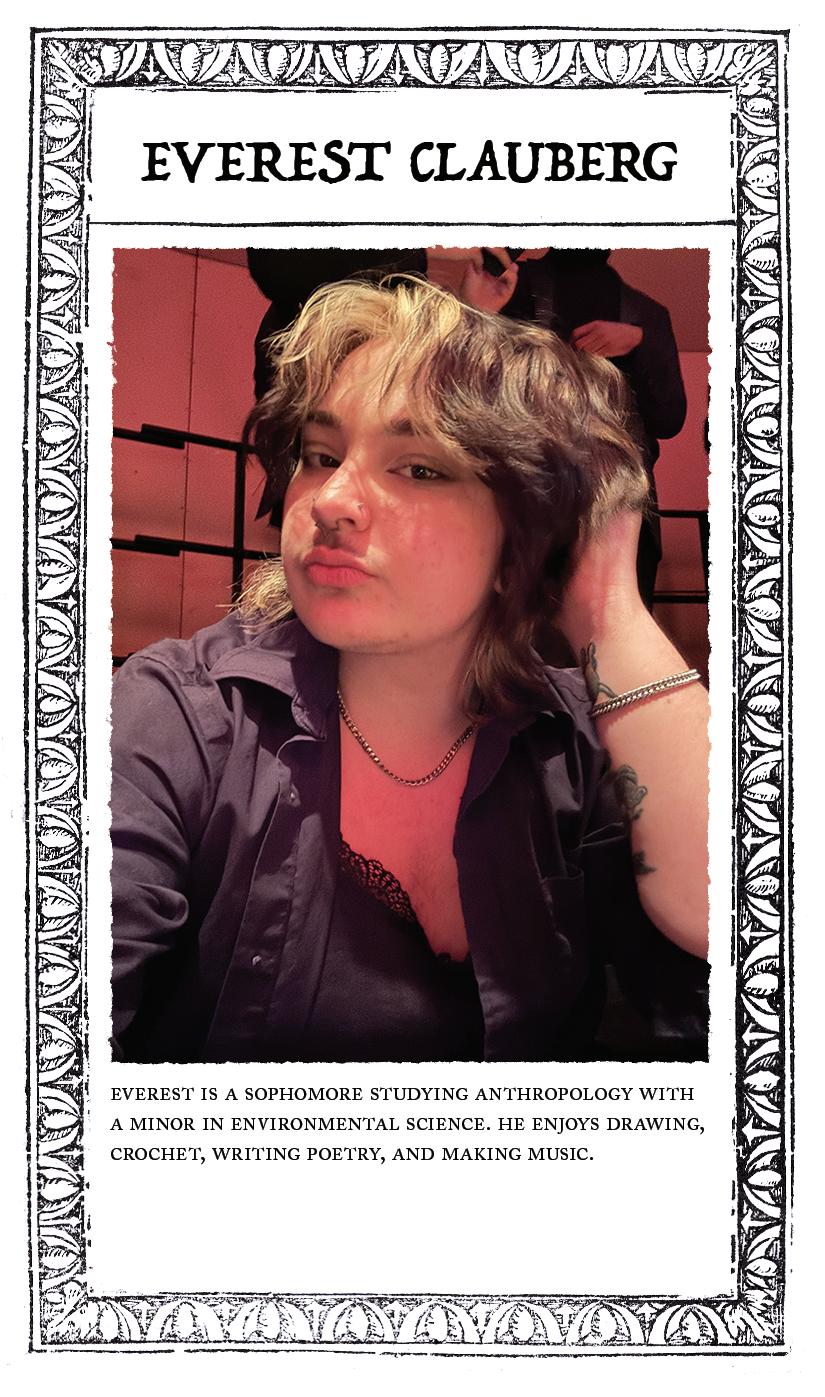

editor of poetry everest clauberg

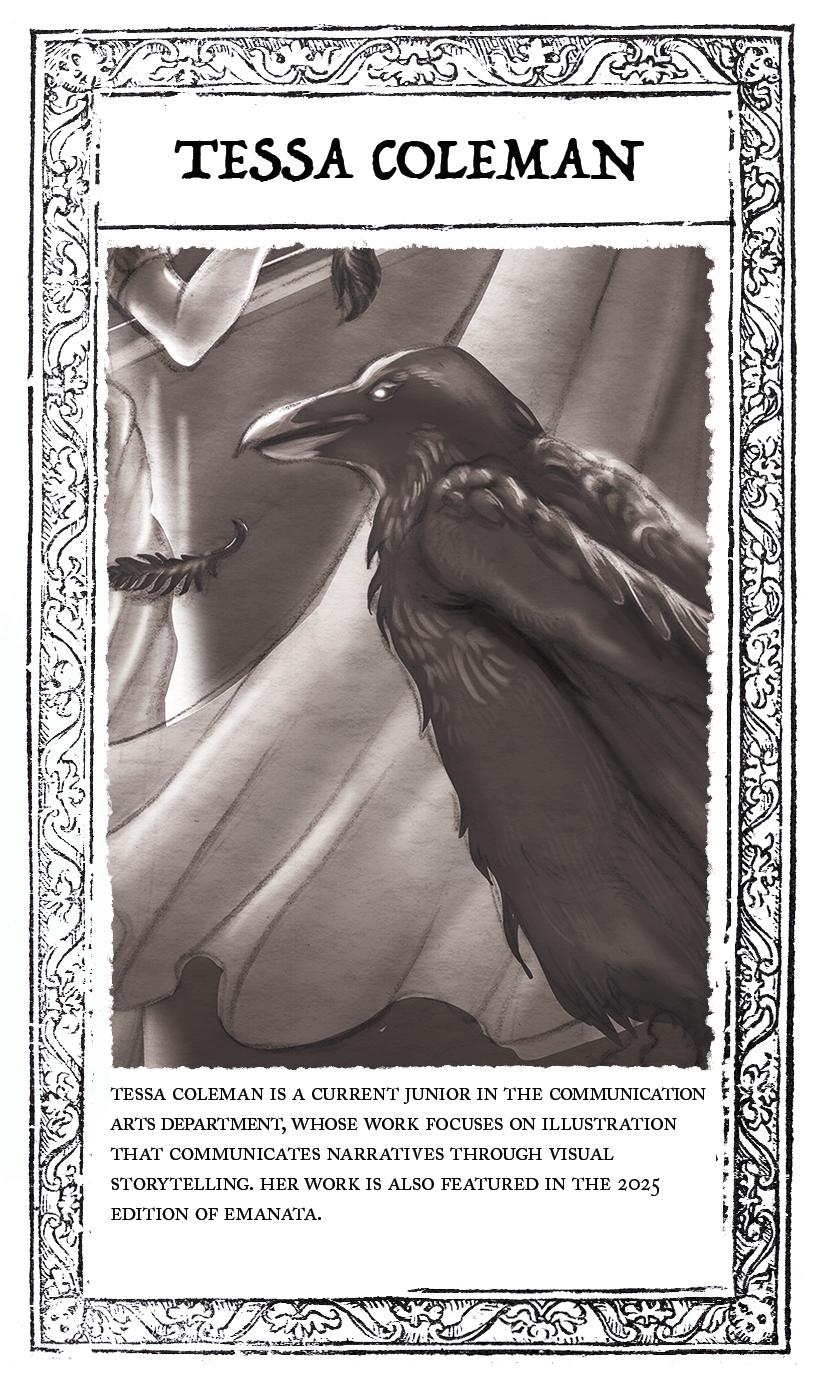

editor of art tessa coleman

publication designer milena paul

general manager zephyr conrad

©2025 annum arcanum

vcu student media center

p.o. box 842o10 richmond, va 23284

annum arcanum is a workshop and annual publication by and for vcu students. check us out online at annumarcanum.org

about volume 1:

We at Annum Arcanum are so excited to bring you our Volume I publication.

Annum Arcanum is still a very new organization, so from the bottom of our hearts we want to give a special thank you to all of the people who submitted pieces, as well as the staff at the Student Media Center for giving us the support we need to be able to publish these student works.

This year has been difficult for many people and students at VCU and Annum Arcanum strives to be not only a place of comfort, but a creative outlet for those who process their feelings through art and writing. This community has meant so much to me and to the entire group of editors.

We look forward to seeing you all again next year and seeing what amazing pieces you all create!

- zephyr conrad

the lady by wyatt unrue

skilken stalker by aliyah robinson

town with the little tin diner by tilden culver

never flitting by tessa coleman

room 102 by janie wright

kudzu by wyatt unrue

from legend to myth by zephyr conrad

a night with the lady by wyatt unrue

wurdurlac by amari louviere

annum arcanum staff

written

The painter had such a look— Painted on his face, When the boy shot his gun. BANG!

I was there, as Always. I had led him to— That field.

I grabbed his Wrist, guided his— Hand Across every sunflower. When that writer— Wrote her last page. She had lost her tears, A long long while ago.

I had wh i sp ered Word after word Into her Ear.

Their t hou ghts, Hitting the floor, the walls, Precious. And it would be— On to the next one.

It is just so fascinating, To lead them all Along.

To pluck out their— Stories, pictures. P re tty little things I make bubble up Inside them.

The little ones I watch, caress— Carefully. Make them sing Colors only they can see.

Listen to them weep, All and every, For their muse, beg for Their Lady.

written by

Ididn’t remember when or why I’d started driving with one hand. It was my left hand, too, which had always been my weak one, and it surprised me every time I noticed that one limp fist on the wheel. My right would be caressing the passenger seat, squeezing where the upholstery was still soft. It hadn’t been touched by anyone else in six months. The less soft patches of fabric, the worn and well-used parts, had been stuck in some purgatory for all that time, a faint, frozen imprint of the one who rode it last. It was a skinny one, just two legs and the bone-outline of hips. They were frailer than I wanted to remember. I had gazed down at them so many times I knew exactly where they started and where they ended, the exact width of each thigh—including how fast they’d shrunk before leaving that final mark—and where in proportion sat her lighter and near-empty cigarette pack. She never smoked the last one.

Both the lighter and pack slid onto the floor when I braked. I had missed my exit. The desert roads were long and winding and red, a snake of heat exhaustion I’d been following for the better half of eight hours, a snake that was shedding now into some amalgam of asphalt and sand that looked the same in every direction. The GPS blinked at me furiously, as if it knew my destination any better than I did, as if it had stakes riding on whether I arrived or not.

The only stake I had was, even to me, delusion. My truck lurched itself around and groaned with the know-how and authority of someone who understood what they were doing. It was an understanding I must have been left out of, because the longer I’d been glued to the driver’s seat for the road-trip I had started, it felt more and more like I was just a passenger out of my league.

The diverging, cracked mountains ahead looked like Earth’s womb; they brought me some semblance of peace, as if the desert was reaching out to reassure me I had a reason to be there. And when the roofs of modest shed-houses began to rise, my expectations rose alongside them.

Harper’s Valley. Birthplace of God.

Houses were indistinguishable from storefronts, storefronts indistinguishable from Cold War relics. They were a breath away from caving in. No mold or ivy grew on them, the desert being too arid for anything like that, and the only sign of life I could see were the weeds sprouting up through cracks in the road. I cruised along at a stable twenty, remarking at nothing in particular but the fact I saw no church or synagogue or mosque breaking up the monochrome desert townscape.

I pulled into a small lot off the side of Main Street— it was called that despite its resemblance to a back country road. There were no lines or designations for parking spaces, but two dirt-caked pickups marked vaguely their places, and I found a spot between them that was just big enough to fit my Tacoma.

Harper’s Valley Diner was a frail building—a trailer more than anything—wrapped tight in tin siding that glistened like sweat under the sun. It smelled like sweat, too, or at least

town with the little tin diner

looked like it should—that dirty look of grease and built-up oil, so thick the corners had long since turned yellow-brown. Its windows stared blankly with the look of cataracts, its shutters hanging loose from their hinges in the way eyelids might sag.

The waitress didn’t greet me. She was pouring one man a coffee as he finished off a beer. I slid into a seat at the counter, four or five to the left of him out of fear of his breath—and the tattoo on his bare scalp, though I would never admit that—and waited. The smell of stale hazelnut seeped out of the walls, mixing with the must of the air vents into some sour concoction. It took five minutes for the lady to come to me, and I only knew that because my watch was all I had as a distraction.

“Need somethin’?”

Her voice was heavy, like a smoker’s. My own voice came out shrunken to compare, muddled further by the banging, thundering of the vents behind her. “Just coffee.”

She slid me a cup. It was cold, the coffee, and tasted vaguely how cat urine smelled, but I took it in with the same thirst that her throat seemed to have when talking. “Oh,” I remembered, “and directions.”

“Just coffee means just coffee,” she said.

“I know. I forgot.” I stopped drinking.

“But I’m actually not from here—”

“I can tell.”

“Yes, well; I’m looking for the birthplace of God. I’d like directions.”

“You’re lookin’ at it.”

I took another sip to fill the void, the tang of it enough to

suppress the discomfort I felt in my gut.

“That’s what I’ve heard, yeah. But…” I looked back at the sun-spotted windows, the dust on the floor and the tattooed man at the end of the bar. “…Is there a memorial or something?”

“No.”

It was a blunt answer, but I could be blunter. “Then tell me where your church is.”

She stayed rigid. She did not show emotion, or inflection, or recognition of my person as anything but an annoyance to hers. “We don’t have one.”

“Any place of worship would work, really.”

The wrinkles on her neck bunched up when she shrugged. “We don’t got any.”

Now my mouth tasted more sour than the coffee. Nothing worth your time, anyway. There was no music playing overhead, making the stew of disappointment all the more loud. “I must be in the wrong place then. My apologies.” I passed my cup back to her and she took it, still half full.

“Well, where’s the right place supposed to be?” The tattooed man from five seats down had slithered up beside me, something I had not heard despite the bulk of his frame. He smelled like spice and tobacco, like he had walked in from some experimental kitchen with a far too heavy hand for sauces. He wore a vest that clung to his skin with sweat, not from activity or exertion, but from the midwestern heat that permeated even the most ventilated—poorly, unfortunately—spaces. The added smell of hot leather seeped out when he hoisted himself onto the stool.

“I was told it was here. Some guy said this place had all tilden culver

the answers.” I took a glance back to the glass doors I’d come through, the barren streets and old houses meeting my gaze with taunting emptiness. “Seems he lied.”

He laughed, though I’d heard nothing particularly funny. “Some answers aren’t meant to be found, you know. But I get it. Certainty is hard to live without.” He took a pack of cigarettes out of his pocket and lit one, the familiar stench of it pulling me close and grabbing my heart through my nose.

“The answers for what?”

My answer didn’t want to voice itself when I told it to, crawling out only in a hushed croak that the man seemed to take hungry pride in hearing. “I want to know what’s out there. After death.”

“A classic,” he said.

“A classic? ” I asked. His attitude was chafing, the way he held his shoulders like a box with no regard to how mine stayed slumped.

He and the waitress shared a look. “We see people roll through here every now and then. Always a little existentialism on their minds, looking for some grand answer from up above. Or down below. Hell, people from all walks of life end up here, all beliefs, all backgrounds. I guess the need for assurance is a primal one.”

My eyes opened wider despite the sting of cigarette smoke. “So I am in the right place?”

“I wouldn’t say that,” the waitress said.

The bald man shook his head in agreement. “Don’t bother. You’re only setting yourself up for trouble.”

“I’ve already dealt with trouble,” I spat. “Two days on the road, eight hours just today, and the money I’ve spent on gas town with the little tin diner

is nothing compared to what I spent just to learn about this place.” I could feel heat building up inside me and I let it out with a short, grating laugh. “And that’s just the start of it. Six months I’ve been driving myself crazy. Six months I’ve been alone, awake at night mulling over death and how unfair it is. Everyone knows it’s unfair; death is hard—it’s always hard—and it’s the one thing we can never really outrun. But god, it hurts. It hurts more for the ones left alive. I think I’d prefer death over one more hour of this uncertainty, of this feeling of being robbed.” I didn’t realize I had stood up in my rambling, legs and chest trembling from the tears I would not cry. “I need to know where my wife is.”

Even the air vent had stopped rattling, submerged in baited silence while my words hung untouched in the room. The waitress kept her eyes on the counter while polishing a single dish in circles. The bald man spoke up: “Your wife. She died?”

“Yep. Esophageal cancer.” I was fixated on every draw he took from his cigarette. “And you know, the hardest part wasn’t the diagnosis. It wasn’t the progression. It was having hope she’d survive. And it came so easy to her. She was convinced that something out there, some higher power or natural force would keep her safe. She didn’t trust doctors. She didn’t trust chemo. She trusted her body, her ‘Earth,’ like they didn’t care she’d smoked half a pack a day for twenty years. And now she’s gone. She left me all alone.”

The cigarette hovered just above his lips. “Man. That’s a lot.” He sucked. He exhaled. Smoke swam around us. I glared at him through it, though the nicotine had done its job and left him looking unfazed.

“A lot,” I echoed. “That’s a way of putting it.”

“No need to get short with me,” he said, finally lowering the stick from his lips and coughing as he looked at me. “You’ve been through some tough shit. I get it.”

“No. You don’t get it. You couldn’t possibly. Don’t act like you do,” I said. “How often are you lost inside your own head? Is it more often than you’re living in the present? Because I can’t remember the last time I’ve really felt truly alive. Do you stare down hallways and street corners when you’re alone, hoping some glitch has happened in the right place, at the right time, for your wife to come walking by? Does it kill you every time a stranger walks by instead? Are your nights taken up praying to gods from texts you’ve never heard of and certainly weren’t raised to read, but your love and grief outweigh your faith and worldview to the point you’re hoping that all you once believed was wrong? See, the reason I know you’ve never felt a fraction of what I do is because you’re trying to stop me. If you got it, you’d know that meeting God—whoever, whatever it is—is the only place I have left to turn. I need it to answer me.”

“And sometimes people have needs that can’t reasonably be fulfilled.”

“I am trying to meet God. I don’t care what’s reasonable.”

He sighed and put his cigarette out on the counter. He did not stand up, but even while seated his head was near level with mine and I could see the resignation seeded across it. “Not like that. You know; some things are beyond our ability to reason. They’re incomprehensible to us. Personally, I think that’s the way those things should stay.”

The flaring of nostrils, long since a self-cooling measure,

did me no good in that little stare-off between us. “Stareoff;” it was more one-sided than anything else, me glaring at the gleam of his bald head where only the fringes of his tattoo were visible. He was still staring at the spot where ash met granite, waiting for my anger to snap back at him. That certainty he sat with did him no favors, the rage already in my gut growing hotter as his interest seemed to cool.

“Riddles!” My face felt bright red. “You’re messing with me? I haven’t been the ass of enough jokes? Do you think I have even an ounce of patience for what you find funny?”

“I’m not making fun of you.”

“Like hell you’re not.” I rammed into his shoulder before I could think about it. And he finally stood up. In the short moment of air I had, I could see the tattoo on his scalp. It was a snake.

My eyes were now even with his neck, and despite the distance I could still feel his breath slinking down mine. I had come to understand in my years that anger could turn a person stupidly brash, so stupid as to blind them of it, and that I was someone who was particularly and frequently affected by this. My wife lovingly called me, at times, a mad idiot. Being pressed against the bald man, close enough to inhale with every breath smoky brew, was enough to shake even that blindness out of me, long enough to see, to blink, to ask myself what it was I thought I was doing. Introspection, she called that. I had recently gotten used to it myself.

But I did like being blind. There was a rush to it. Adrenaline, some kind of drug; it kept me wired and persisting. And what was a proud man if not for persistent? It wasn’t much of a decision at all in the moment—it was a necessary thing, to

town with the little tin diner

persist. I did not step down from the bald man. There was no one on my side to pull me back.

“I think you should leave,” he said, looking at me. “I don’t want to fight you. I don’t want trouble.” He took the sunglasses from his collar and laid them down with force. I felt hot in my gut, slit in my eyes. “I don’t think you want that either.”

“Are you challenging me?” My voice came out rough, grainier than usual. I hadn’t prepared it in my head before I spoke.

He didn’t stir—not at first—taking in my words like a slow drag from a cigarette before coughing, blowing it right back in my face. “Wouldn’t waste my time on it.”

I did not need to size the situation up to know punching him was a bad idea. Bad idea, bad angle; with the height he had on me, my fist had air to cover, and with that same height he had the advantage of watching it fly all the way. Of course, I had opted to be blind; I couldn’t see the agitation on his face or my knuckles make contact with his jaw. I hadn’t fully processed it until I felt his stubble on my skin, sharp like short needles or the pins on a cactus.

“You’re not gonna swing back?” I asked. His hands were clenched shut like he was ready to, trembling like it took real effort to hold still. His inaction, in a way, was more painful than anything he could have done. He didn’t talk, he didn’t say anything, and in the fury of the moment I took his silence as mockery. I punched him again. His jaw, his stomach, his padded gut; I wailed on him with every ounce of anger I had and did not stop when my arms burned from use. If he felt any of it, he didn’t let it show, not flinching or yelling

or shoving me back so that my brain bled when it hit the ground. “Why the hell are you standing there?” I shouted. “Just hit me. Just hit me, goddamnit.”

And then he finally moved. But he did not hit me; he cupped both hands over my fists and held them there, a gentle grip but an unwavering strength that, even if I hadn’t been exhausted, I would not have been able to shake. “No,” he said. He pushed my arms away and I nearly lost my footing from the force of it. “You’re not going to take your anger out on me.”

What was it—anger, frustration, an overwhelming urge to spit and shout and hurt? I couldn’t place it as easily as I could earlier. It sat behind my eyes like tears that wouldn’t fall. “You are not going to stand in my way,” I said, lips pursed and nearly hissing. “You are going to tell me—you are going to take me to God. I don’t care how much you revere him. You are going to watch me ruin him.”

I hadn’t expected him to let out a laugh, not even the sad, breathy one that he did. He turned around and sat back on his stool. “I revere no one,” he said as close to a mutter as he could get, almost like he felt insulted by the mere notion of it—of reverence. He fished out and lit another cigarette from his pocket. “You don’t need me to show you anything. God has a way of making itself known.”

The lady at the counter switched his coffee for a longnecked beer. She glared at me when she looked up, pointing to the door with such force I could hear her wrist bones click together. I didn’t argue; the stench of tobacco had spread so fully through the room that, besides the tension, it was all I could taste, thick and rancid from the desert heat seeping in. tilden culver

town with the little tin diner

I let the doors shut behind me with the same rattled bang they’d made when I first walked in.

But there was another banging there, long after the doors went still, drumming like a hammer trapped underground that now felt determined to dig itself out. I could feel it too, down under my feet, shaking and humming with such rhythm that my shin bones became almost like jelly standing there. I was alone; the diner doors made one last click of a lock and I caught the lady staring out after me while she steadied them shut.

I hadn’t realized my hands were shaking, too, until I went to get in my truck, the key leaving marks around the driver’s side handle. I told myself it was an earthquake—this was earthquake country, after all—though by the time I slid behind the wheel I couldn’t differentiate between tremoring earth and trembling me.

I took off down the road. Every building, every house and business looked like one continuous blur from my windshield, like a shitty mirage at home in a wasteland. The rumbling and banging and shaking didn’t stop when I blew past a stop sign—the only stop sign in town—and in fact grew stronger to the point my keys were swinging like a pendulum from the ignition. No steeple or stained glass stuck out through the mess of clanging shutters, and though I strained my eyes looking I could find nothing holy nor godlike. By the time I had reached the end of Harper’s Valley, I was looking back through my rearview and what I saw was no birthplace of any god or way of thinking. It was a hole in the desert wall.

And then in front of me was an explosion. It was not

nuclear, or atomic, or fiery with a mushroom cloud, but a scrounging eruption of dirt and sand that blanketed my windshield with dark. I slammed hard on the brakes, though I didn’t need to; the truck had already come to a stop on its own.

I reached for the door but it would not open. It felt— and from the window, looked—like it had been buried by some impenetrable mound of rubble, pressed up against so tightly that I could not budge it even an inch with all my weight. My head began to get light, filled with and held up by imaginary smoke; I could not tell whether it was asphyxiation from being buried alive or the adrenaline of what I found myself in the center of. A drowning man would feel the same way.

The dirt eventually lost its grip on my windshield and slid away in chunks, leaving behind a pane adorned with mud spots and chipped glass. But the cracks did not concern me; my eyes went through them and so did the thing on the other side. The thing, a horror.

Two hundred feet tall—no, double it. I stared with no expression, no thought but awe, and could do little more but sit in the driver’s seat with my face glued lamely forward. It came from the ground, from the red dirt like a stem, but it throbbed and pulsed and moved like no real plant at all. At its base it swallowed my vision, thick and banded like the belly of a snake so large it came not from this earth, but a reality of giants and titans long forgotten to literature. The thing shined like platinum but still heaved like organic flesh, and with its height so monstrous I could make out no animal without a monster’s head to gaze back at.

town with the little tin diner

As if it knew this, it lifted me. My truck was propelled into the air by some force below—whether dirt or air or more beast I didn’t know—up a hundred, a thousand feet until I could no longer see the ground the thing had burst from. And then I saw light, a whole sun’s worth of it, all billowing out from where the thing’s face should have been. It came in flares like a sunstorm, wisps of plasma shooting out in every direction but never burning me or melting the window’s glass. I saw eyes in the light—it was all I could see, outside of bright blindness—spattered about with no real reason but to be striking. I could not count the eyes, but there were many, each with a pupil distinct from the other as if ripped from each species on this planet, some slit, some rounded, some haunting in their humanity. The one I stared into was a woman’s. It was blue. In the light, it came to seem like that’s all there was; no truck, no sky, no town below or anywhere. Like a world filled up—wholly and only—by an eye. Unblinking.

“You stare,” it said. I assumed at least; it had no mouth to speak from, and its words bounced around my brain like a fly set on escape. I was staring—how could I not be?—and I had lost the ability to do anything but stare in that moment, locked in a trance by some moth-to-flame entrapment. “You desired,” it said again inside my brain, “to see me. And now you have. And now you are broken.”

I didn’t say anything. I couldn’t.

“Have you no question to ask?” it hissed. “No anger?”

Its words were louder now, like metal on metal clashing. They filled up my skull to bursting, slipping into every wrinkle of my brain and causing it to ache as it stretched.

U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U U

I could barely make out my own inner-voice, it having been buried so deeply beneath its screeching. “What… are you.” It was not a question.

“I am your father and your mother and your master. I am your children unborn and the small shrew that scurries through the desert brush. Do you hear the wind still, child? I am the heat that travels in the breeze, and the star above that birthed it. I am beyond the human mind. Do not mistake me for something like you.” Its blue eye shifted from a woman’s to a goat’s, from a goat’s to something unearthly, two pupils fighting for dominance in the same iris. “I have sculpted countless realities with my will, and yet you have come here in search of talk. Your kind does itself no favors.”

The two pupils merged again into a woman’s eye. It was not the same blue it had started as; the etching inside its iris was soft and familiar, a warm shade of ice, one that struck me cold in the chest like a bullet. It was my wife’s eye. I couldn’t mistake it for anything else.

“You know my wife? You’ve seen her?” All the questions and uncertainties I’d had came flooding back, metastatic cancers of the mind. “How—where is she?”

“Transmuted,” it said.

“Reincarnation?”

“Not quite.”

The surface of the thing’s head began to flare, dance, forming craters like sunspots on a storm-brewing star. From around my wife’s stare sprouted more eyes in rapid, random succession, no pattern to their places or shapes. They did not stay steady for long; the storm drew them around in similar fashion to rotating angelic wheels, spinning tighter and

town with the little tin diner

faster until my head burned just from looking. “What do the eyeless see with no capacity for light? It’s a flawed question. They can’t see; the concept, the word sight means nothing to them. And how does the dead experience pleasures of the living? Knowing, thinking, feeling... Being. It is simply beyond them. Because there is no them. There is me.”

“There is you,” I said. “But what are you?”

And then, with a pop, all the light went away. All the eyes, the incomparable shadow of my dashboard, it disintegrated with a breath. It felt like a cold hand had fallen over me, snuffing out the sting in my head and the thunder running from my heart to my skull. The thing’s voice consumed me; it filled my ears, my head, pressed low to a hiss that felt audibly like gravel. It whispered to me three words. They were words of a nature so vile that I could never bring myself to repeat them, for repetition would require the memory to pass back through me and enter my brain all over again. For it to utter what it did in the moment was enough to pause all thought inside me, to freeze the very liquid in my veins and, for a second that felt like eternity, the beating in my chest. I was thrust into… nothing. It was quick and forever.

“I am alive,” it said.

And when I came to, I was back in my truck on the ground. There was no dirt caked on the windshield, no rock or clay dredged up from Earth’s core. Everything was serene, if not heat-fuzzy, like a placid, desert town, rotting in quiet silence in the blind spot of the world. Untouched. Unroused. Even my wife’s lighter still sat in place. It was almost like nothing had happened at all.

I grabbed the cigarette pack and lighter and got out.

tilden culver

I had never liked smoking. I didn’t like the taste of it and I hated the smell, and feeling the bitterness glide along my tongue just now was something of a horrific reminder. All those years with her and all these months without, yet I never understood what my wife liked so much about cigarettes. It mellowed her out, she said. Put things into perspective. And it seemed, as the nicotine washed over me, some part of that was true; the mellowness, at least. I struggled to put into perspective what I could not perceive. But I was alright with that. I tore off my fuel cap and dropped the cigarette inside.

written by

Every Motel 6 room looks the same; tacky wallpaper, gaudy matching bedding where I’d pin her down and take her.

She looked the same, too–business-woman blazer, sexy tights, brown hair bunched up in a claw clip that she’d take down and shake out.

I liked it this way– we didn’t exchange real names, jobs, or personal details; I knew her as MysticAngel99, she knew me as BigBoss202.

It was during our fifth or sixth encounter where Angel became an incomprehensible, beautiful terrifying creature. While our flesh intertwined hers began to melt, bones creaking and hissing through her multiplying teeth. Stringy viscera

grew over the bed, grew over my nudeness and onto the floor, consuming our clothes, painting the yellow wallpaper With ivory skin and crimson guts.

Wings sprouted from her back, and the comfort I took in her anonymity became her secret weapon.

We became one and I could no longer pretend she was my Angel.

janie wright

written

Shadow, Brimstone,

Down where the sour southern wind blows; Where the Devil’s vine grows. That those poor souls would willing sow, Thinking it would save them.

Each year it would mark, As my momma marked my height, Mark another forgotten post, abandoned lampshaded light or an old worn shed.

Every Day, Another tree, so brutally choked like the ghosts of my friend’s Forefathers.

Each week I would hear, as My daddy drove down past those old decrepit homes— That some things are left buried; Deep down, deep below.

I watch that Green inferno. I watch it take hold Of everything an’ anything As it creeps into the crypts, An’ into my dreams, Swearin’ to send us all to hell.

written

It was late, the room was cold, and I could already feel her beginning to form herself into being. I watched, out of the corner of my eye, as she grabbed hold of dimly lit shadows, blistering computer light, and half-present thoughts. I kept my focus on the screen in front of me, a page filled with nothing but white space.

It was late, my chair was cheap, and I could feel her drawing closer. My upper back began to warm as she leaned over my shoulder, wrapping her arms around me in some phantasmal embrace. An airless breath warmed my cheek, and my chest began to ache.

The time was around 8 p.m. as we walked the streets. The moon was full, sending silver rays down on the empty blocks and crosswalks. She kept beside me, drifting a good four feet off the ground, some lighterthan-nothing kite. I found myself staring at the faces forming in the moon as she broke the silence.

“Hello.”

I glanced over as the nonexistent breeze carried her forth. “Hello,” she said again, questioning the phrase; testing it, tasting the phonetics. “It’s definitely a word, isn’t it?”

I paid no mind answering the question. Our walk continued, and she continued to orbit around me.

“You could kill someone,” she said, landing behind me without a sound, her footsteps then becoming deafening as she matched my pace, “Of course, you won’t. You’d never, what with laws and all that. And repercussions. And basic human empathy. You could though, physically.”

Each word held some unknown tilt to it as she forced herself into view, leaning forward just enough to pop into vision. “You could write about something like that, maybe. No? Hm.”

My joints felt hot, though that was nowhere near the correct term. Cramped, pushed in, yet never willing to crack apart. I wondered if I should see a doctor. I would call one in the morning. I would change my mind before then.

“What’s that belief they have, in Hinduism? Karma? To hurt another is to hurt yourself? What would murder be, then?” she asked, before a smile broke out at her own realization. She sauntered closer, eager to share her discovery. “Murder is suicide. That has a nice flow to it, you should write that,” but I did not respond. I never needed to, after all. A step and she was in front of me, a blink and she was behind. A sudden rush of wind through the leaves, and all went to hell:

How do you describe something that you simply cannot hope to put into words? A color, a feeling. What do you say when the word you need simply does not exist? How do you describe this phantasmal Apollyon, highlighted by the deep blue of a July sky? Waxing and waning like the pearl-white moon above it, raging and whimpering and boiling and freezing and lefting and

righting and— (I forget, I wished to save this monologue). She stood there, feet on the ground, before me. She stagnated, held up by strings of light, 100 feet from the cement sidewalks. Her hair was long, a curtain of shimmering vapor that trailed to her heels. A slight tilt of her chin, and it was cut a razor-blade’s width from her scalp, uniform and unwavering, a close-knit wrap peeking from her head. I spent forever staring at the sight, before, in a nanosecond, it ended.

We turned a corner and continued our walk. The stars blinked above us, as they often do when no one is looking, and when many, many people are.

“Could you count them?” she asked, “Could you make people want to count them? Every single one?”

I did not have an answer, even though I definitely did, and so I chose to say nothing.

“If not you, then someone else,” a viper’s kiss, “if not them, then someone else’s someone else. Oh, aren’t they lovely?”

She nestled into my side, and I noticed the soles of my shoes were worn thin. My feet ached, but I would soon forget the discomfort. I dreaded the chore of getting new shoes.

The time was around 8 p.m., the streets empty as an unfilled cup (I have failed to create an evocative allegory). I wished someone would appear. I wished they would stay barren forever. The mirage glided into the street, and like a spider began to spin her webs out of what empty thoughts were crowding my empty head. A murmur in my ear drew the heavy ache of sleep to my eyes.

“What do you want?” She asked, and I opened my

mouth to respond, but she beat me to it. “Everything, nothing,” she seemed displeased with the answer she had stolen. “Well, that just won’t do, will it? Maybe you can pretend you only want a specific thing... but that would just be boring.”

I nodded along, and again, and again. It was nice out. My body was tired, on the brink of collapse; my mind was awake, refusing to fall asleep.

The specter slipped away on a silver sliver of moonstrung shadow, a slipstream of the summer air; she never moved from my side. My heart lurched as I felt the fantasy of a hand in mine.

“You should finish those songs you wrote.”

The sudden change in topic caused me to make the mistake of looking over. Her eyes caught mine. I was doomed. I had made the grave error of meeting the basilisk’s gaze, my muscles locking up like a neglected mass of cogs and gears. She leaned in, closer. The world behind her, around us, bent and warped, some self-imposed tunnelvision, or vertigo.

She smiled.

Her expression was stoic.

She smiled.

Her expression was stoic.

She smiled, all the while having her face remain unmoving, all the while having her face remain everchanging, all the while having her all the while and all the while having.

She stole something. That, or I gave it up willingly. I know not which.

Eventually, eventually, I was released, and we continued our walk. Eventually, eventually, I would return for whatever part of my brain she had trapped to that singular spot. Of course, I would most likely not.

“What’s that one story you’re writing? ‘The Sky is a Giant’s Skull’?” Her voice returned like the tide, true as blue is orange (not even I understand what is meant by this). I flinched, I wanted to run away, so I stopped moving. I wanted nothing more than for her to stop, to make her stop, immediately, before she said anything more, before she would say what I knew for a fact she was going to say, because I knew that she knew that I knew for a fact that I knew that she knew I knew, and she knew.

Some unseen string pulled her up by the heel, and, the weightless black hole that she was, caused her to flip upside down and into the air right before me. She continued our one-way conversation, despite every fiber in my body doing absolutely nothing to prevent her.

Her smile remained. Pleasant, cruel. Both, neither. “I think it’s worth something. Interesting, at least. Especially that one scene, when he tries to strangle her. You really have a habit of writing characters like them, you know,” she swayed from side to side, her pupils straining to look above her (or below, I suppose) as she pretended to mull over what next to say, “Sad, pathetic, listless guy...” she trailed off, giving me a look, because she knew its payload would be far greater than if she had said the all-too-obvious follow-up.

She continued, as if the pause had never happened, “A psychopompic, imperceptible imperiophile...” she cocked

her head to the side, “I wonder where you get the inspiration for that from,” The vision laughed, silently, louder than anything, as the invisible string released her from its pull. The phantom’s feet hit the pavement beside me, soft as a feather. I said nothing in response.

I checked the time as we turned a corner, then promptly forgot it. I did not bother checking again. From then on, it would be 8 p.m., until such was no longer the case.

I felt like crying, at some point. I would have if I could have, but the tears would not form. All that would come out my eyes was that gentle, longing ache (I feel I use this word far too much). She seemed to notice this, but, shockingly, said nothing about it.

“ It’s a boring life, isn’t it.”

A statement, not a question.

“Beautifully boring, even,” she sighed along with the gentle breeze that passed us by. It sounded like indigo paint.

It sounded like the way chocolate tastes.

It sounded like nothing.

It sounded like everything.

It sounded like a thought.

It sounded just like a thought.

I cannot express it enough; just how much it sounded like a thought.

“This makes for a dreadful story. Oh, don’t look at me like that, it’s dreadful for a reason. I already told you; you don’t want anything. You can’t make a story out of that. A poem, maybe. A painting, but not a story,” she said, so matter-offactly, yet it was in the slight strain of her cordless voice that at the same time, she said something utterly different. It was

a night with the lady

filled with wind-chimes, and cicadas, and soft grass:

“A picture speaks a thousand words. Why can’t you put them in a book?”

But I already knew the answer, maybe. I did not, I think. Maybe. I do not know. I sat down on a bench, it was well made, I think. I wanted something, maybe.

“Everything, nothing,” she reaffirmed. She may have been sitting beside me, or above me, or inside me. It matters not. Wherever she was, she seemed to have found something else tucked away in the radio-static of my head.

“To make something that makes people cry. Well, that certainly is something. What, gonna steal a page from Hemingway? You can’t really get any better than ‘For sale, Baby shoes, Never worn,’” she crooned, “I don’t know if I should call it beautiful or sad. I guess it can be both. Sadly beautiful... beautifully sad. I like that one, I think. Beautifully sad.”

My mind wandered to the left a bit, then staggered to the right. I could tell she was watching it, a cat watching a mouse. I heard her whisper something, a small nothing. “Oh, isn’t it terrible? Tota universitas in capite tuo adhaesit.”

She followed it up with another meaningless murmur, “Oh, isn’t it wonderful? Tota universitas in capite tuo adhaesit!”

I only heard the noise, not the words. I was too distracted to hear them. Too distracted by that feeling you get when nothing is out of the ordinary, no matter how much you want it to be. It passed, however, as all things do.

There was a face forming in the moon. A moon that was so, so clear. So there. A shimmering, winter moon, in a hazy summer sky. I wanted to grab it. I wanted to put it in

my mouth. I reached out for it, idly in muscle, straining in thought, thoughts that continued to spin out and form the words of something else, or someone else.

“A cold spoon. That’s what it tastes like. A slightly wet, cold spoon. Or an ice cube.”

I stood up on the bench and reached further. I kept myself from reaching too far. The face in the moon finally settled, for just a brief, insignificant second, into hers.

My fingers curled, just a bit, as my arm lowered. Her hands were on my shoulders. They were cupping my face. They were grabbing me by the hair. They were holding my own.

She was flying through the air. She was dancing across the street. She was standing right in front of me.

I felt the ache of my joints. I felt the ache of my feet. I felt the ache of my eyes. I felt the absence of what I had left stuck to the sidewalk. I felt the millions of little nothings that all piled up in a mountain of anti-matter inside my skull. I felt the warm, gentle, agonizing summer breeze rush across my body. I saw her, a metaphysical singularity, staring right at me, and at 8 p.m., all went to hell:

How do you describe something that you simply cannot hope to put into words? A color, a feeling. What do you say when the word you need simply does not exist? How do you describe this phantasmal Apollyon, divine Sappho, before me? Highlighted by the deep blue, the blackest blue, of a July sky? Waxing and waning like the pearl-white moon above it, raging and whimpering and boiling and freezing and lefting and righting and everything and nothing all at once. How do you put the conflicting thought that exists, that can ONLY exist

in your mind, to something outside of it? How do you describe the taste that forms in your mouth when you hear the sound of popping embers? The feeling you get in your bones when you smell the salt in the sea? The disconnected ramblings that spontaneously pop into existence when before, there was nothing? How do you transcribe the shifting layers of consciousness?

How do you describe a thought?

“How do you describe the—”

—Fundamental concept? The heavy—

“—Feeling you get in your head?”

I sat back down on the bench. I imagined myself crying, violently sobbing. I imagined stories, all of them different while still managing to be fundamentally the same. I grew bored then, with both the imagined sobbing and the stories, and so I stopped.

I could have said something. I wanted to. I wanted to scream out at the top of my lungs. No one would have stopped me. I could have, but I did not, for nothing formed in my brain to be said, and although the want to cry out was present, my lungs would not suck in the air, and my mouth would not open to force it out. There was nothing I could say, and so she said nothing either.

There are hundreds of thousands of millions of billions of trillions of things that happened after, but they were nothing different than what had already occurred. Eventually, I grew too tired to continue walking the streets. Eventually, the moonlight urged me to go home. Eventually, it was no longer 8 p.m.

It was late, the room had gotten warmer, and my chair was still cheap. It was silent for a bit, before she spoke up. “You should change the way the narrator speaks, it sounds too pretentious,” she said. I felt her embrace tighten, and with it came some sort of longing. I can’t really describe it.

What hubris, to imagine some spirit, god, whatever you’d call it. To allow the shambling fantasies of your head to hold your hand, to let some thought-puppet hold you close. How pathetic, to pretend they’re real.

It was late, I caught my lonesome reflection in the window nearby, and I grew self-conscious of the game I was playing with myself. I stopped imagining her voice, stopped imagining her mind, all of it. I stopped pretending there was some divinity beyond comprehension next to me, and just like that, she was gone.

I’d written enough for tonight, whether any of it was good or not wasn’t important. All subjective anyway, and besides, it was a first draft. Some people might get it, others might not. Again, it didn’t matter. I understood what was meant by it all.

Except that one part about ‘blue is orange,’ I’d change that eventually, probably. Probably not.

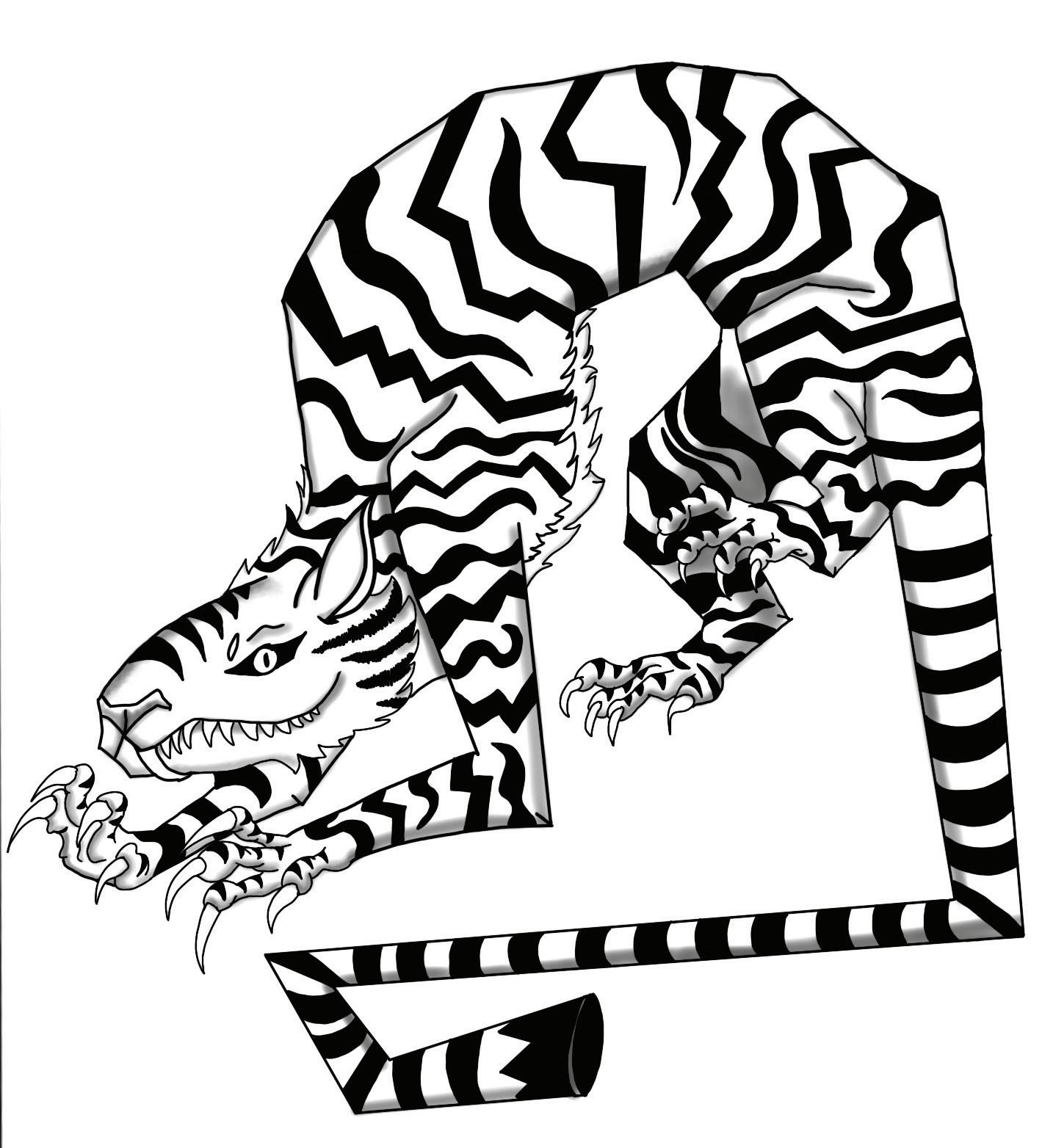

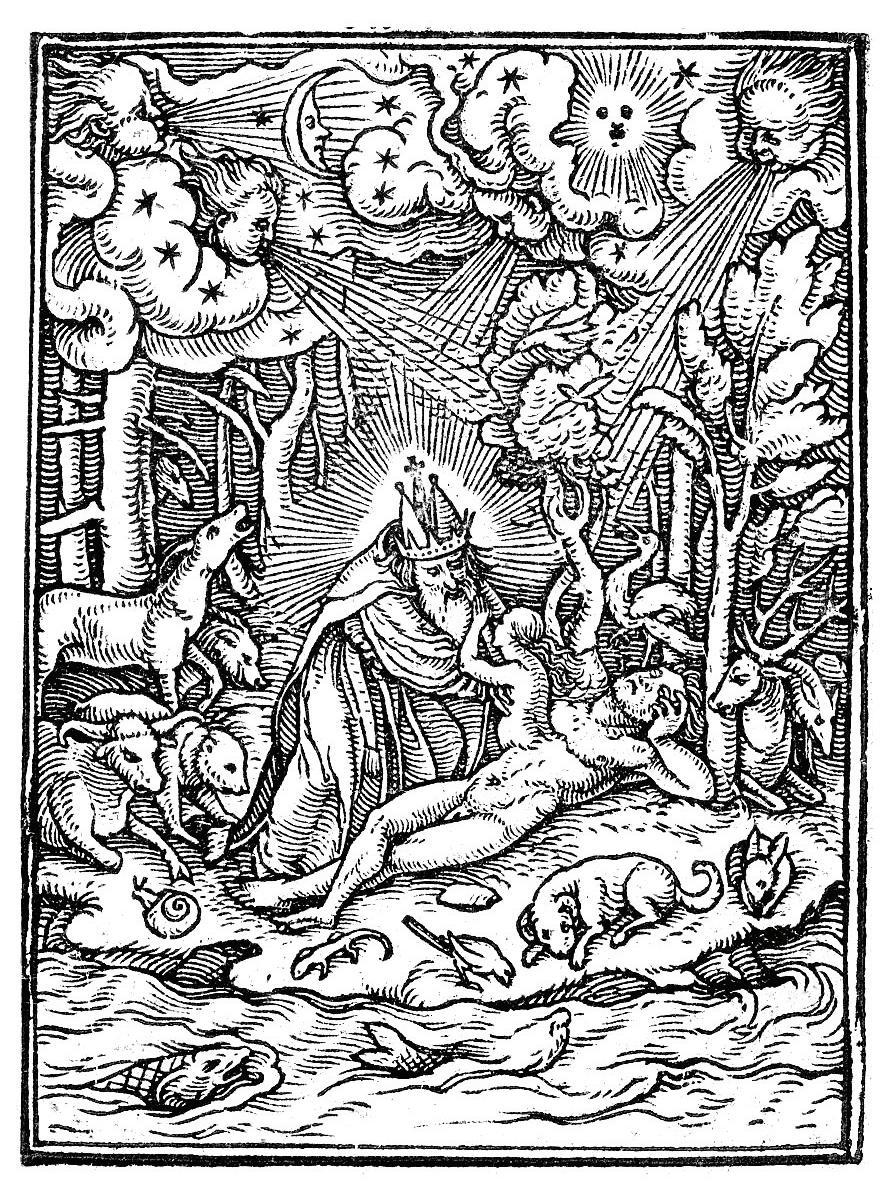

(on previous page)

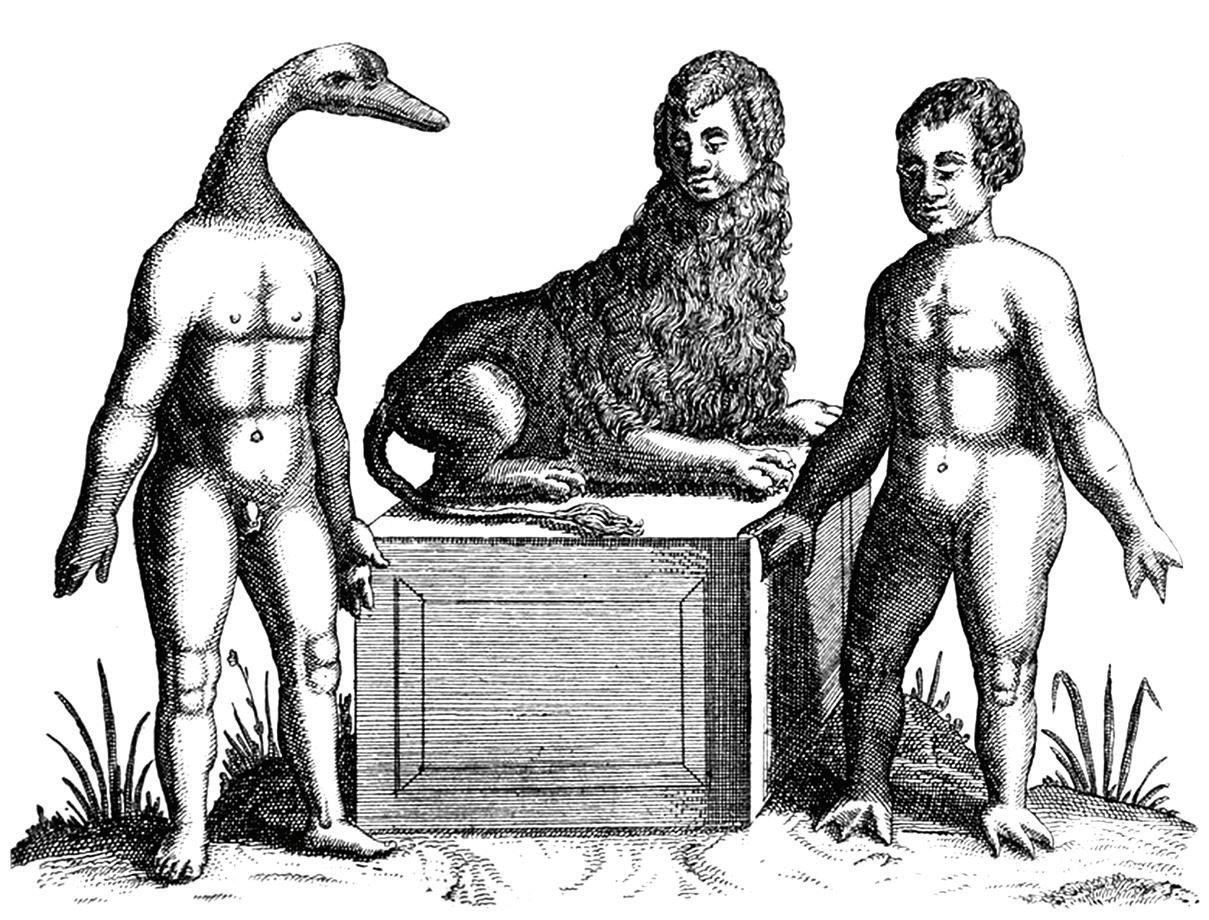

annum arcanum was designed using the adobe caslon pro, r41 gotico, and trattatello typefaces. the decorative images are sourced from the public domain image archive. the cover is printed on neenah classic linen, red pepper, 80lb cover paper. the interior is printed on neenah classic linen, classic natural white 80lb. text paper. printed in richmond, virginia by carter printing company.