PROGRESS TOWARDS DURABLE SOLUTIONS IN UKRAINE

THEMATIC BRIEF

JANUARY 2025

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

CONTEXT AND OBJECTIVES

Nearly three years since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the armed forces of the Russian Federation, extensive and protracted displacement has affected 3.6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 4.3 million returnees, with a further 6.8 million displaced abroad (as of December 2024).

According to IOM's latest General Population Survey (GPS) data from October 2024, a majority of IDPs (59%) have been displaced for over two years. This protracted displacement is becoming more prevalent, with two thirds of IDPs intending to remain in their current location in the medium term (beyond the three months following data collection). In response, the Government of Ukraine and international partners have prioritised early recovery and durable solutions to internal displacement alongside ongoing humanitarian efforts.

This report adopts a durable solutions framework aligned with the Joint Analytical Framework (JAF) proposed at the Data for Solutions Symposium (March 2023). First, it provides information on displaced populations’ perspectives on durable solutions, including the projected stock for each durable solutions pathway. Then, it outlines a narrative analysis of the eight durable solutions criteria across the dimensions of socio-economic integration, security and justice, and community engagement, supplemented by demographic and displacement characteristics to identify vulnerable groups. The analysis draws on key data sources, including IOM’s General Population Survey (GPS) Round 17 (August 2024), IOM’s ‘From place to place: community perception of displacement and durable solutions in Ukraine’ participatory study, and REACH’s 2024 Multi-Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA).1

KEY FINDINGS

1. Displacement Intentions and Pathways

a. Among IDPs, 69 per cent intended to remain in their current location in the medium period, with almost half of these (47%) planning to settle and integrate (estimated 1.2 million individuals). Older IDPs were more inclined to return to their area of origin, while younger individuals and families with children tended to prefer integration in their current location. Fourteen per cent of IDPs aimed to return to their area of origin. However, the majority of individuals in this sub-group (63%) stated they would do so after the war ends.

b. The majority of returnees (87%, estimated 3.8 million individuals) intended to remain in their current location.

2. Priority areas for durable solutions programming

a. Housing: Data highlighted the critical role of adequate accommodation in shaping mobility decisions in the future. 22 per cent of IDPs faced significant challenges accessing adequate housing, compared to 7 per cent of returnees and host populations, which can be predominantly attributed to the cost of renting in areas of displacement. Vulnerable IDP and returnee groups—such as those with disabilities, or with an household income per person below the national subsistance minimum—reported higher housing barriers. IDPs facing strong barriers accessing adequate housing were less likely to

plan to integrate in their current location (28%) compared to those facing no or lower barriers (34%).

b. Employment: Working-age IDPs, especially recent arrivals, reported higher unemployment rates (28% of IDPs displaced for up to three months) compared to returnees (11%) and host populations (10%). Employment status correlated with integration intentions, as IDPs in paid work (37%) were more likely to intend to integrate than unemployed individuals (29%).

3. Displacement-related vulnerabilities

a. Family separation affected 30 per cent of IDPs, compared to 19 per cent of returnees and 15 per cent of non-displaced populations, and correlated with a lower intention to integrate in areas of displacement.

CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

• The findings underscore the critical importance of addressing housing and livelihood barriers to ensure displaced households have the resources and agency to select their preferred durable solution. Facilitating local integration - and preventing unsustainable returns to locations with severe conditions - requires targeted investments in affordable housing and interventions such as vocational training and pre-school care programmes that can enable labour market participation and greater economic resilience among displaced households. Moreover, tailored support for vulnerable groups, including those with disabilities and families facing separation, is essential to ensure equitable progress toward durable solutions.

• This analysis showed the value of interoperable data on durable solutions. It is therefore essential to ensure alignment among stakeholders on the selection and use of indicators. This includes establishing broad-based agreement on contextually relevant indicators that effectively capture the various dimensions of the durable solutions criteria and sub-criteria. Harmonizing these indicators will support the production of consistent, interoperable data and enable more comprehensive and actionable analysis to inform policy and programming.

• In future durable solutions analyses, a comparison of the situation of displaced and non-displaced populations should be included to ensure that displacement-specific vulnerabilities are clearly recognized, as opposed to area-level concerns that should be addressed through a different type of programming.

• To ensure the inclusion of affected populations and adequately capture challenges unique to different vulnerable groups, it is recommended that future durable solutions analyses incorporate diverse data types. This should include qualitative data, expert insights, and perception surveys to provide a more nuanced and comprehensive understanding of the context. Notably, the analysis should adopt a participatory research methodology, as done in the From Place to Place study, to make sure affected populations actively contribute to and are meaningfully engaged in the process.

INTRODUCTION

Nearly three years since the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by the armed forces of the Russian Federation, extensive and protracted displacement has affected 3.6 million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 4.3 million returnees, with a further 6.8 million displaced abroad (as of December 2024).

According to IOM's latest General Population Survey data from October 2024, a majority of IDPs (59%) have been displaced for over two years. This protracted displacement is becoming more prevalent, with two thirds of IDPs intending to remain in their current location in the medium term (beyond the three months following data collection) 2

In response, the Government of Ukraine (GoU) and international partners have increasingly focused on early recovery and durable solutions (DS) for displacement-affected communities while continuing humanitarian efforts. To address challenges in adopting a data-driven approach to durable solutions, national and international technical experts gathered at the Data for Solutions Symposium in Kyiv (March 2023). They recommended developing a Joint Analytical Framework (JAF) for Durable Solutions in Ukraine, aimed at enabling data collectors and users of IDP-related data to generate reliable, interoperable data for both statistical and operational purposes.

The Regional Durable Solutions Secretariat (ReDSS) distinguishes two approaches as complementary methods to assess progress towards durable solutions: progress measurement and criteria analysis.3 This brief adopts the second approach by providing a narrative analysis of durable solutions criteria and their respective sub-criteria, tailored

METHODOLOGY

Data cited in this report were compiled primarily from Round 17 of the General Population Survey (August 2024), which was commissioned by the International Organization for Migration (IOM) and collected by Multicultural Insights through screener phone-based interviews with 40,000 randomly selected respondents and follow-up interviews with 1,488 IDPs, 1,188 returnees, and 1,800 residents, using the computerassisted telephone interview (CATI) method, and a random digit dial (RDD) approach, with an overall sample error of 0.49% [CL95%]. The survey included all of Ukraine, excluding the Crimean Peninsula and occupied areas of Donetska, Luhanska, Khersonska, and Zaporizka Oblasts. When indicated, data from Round 18 (October 2024) were also used in the analysis.

Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) are defined as individuals who have been forced to flee or to leave their homes or who are staying outside their habitual residence in Ukraine due to the full-scale invasion in February 2022, regardless of whether they hold registered IDP status. The term “returnee” refers to all people who have returned to their habitual residence after a period of displacement of minimum two weeks since February 2022, whether from abroad or from internal displacement within Ukraine.

to the Ukrainian context in line with the JAF proposal, using both quantitative and qualitative data4. It intends to complement the progress measurement analysis recommended in the JAF synthesis report by providing an in-depth analysis of each criterion, which can support the interpretation of aggregate data on progress towards durable solutions in Ukraine.

More specifically, the brief addresses the main components of the Durable Solutions Analytical Framework, namely (1) displaced populations’ perspectives on durable solutions, including the estimated stocks for different solutions pathways; (2) the eight durable solutions criteria, organised across three pillars: socio-economic integration, security and access to justice, and community integration and engagement; and (3) core demographic and displacement characteristics, which are used across the brief to identify the most vulnerable groups.5 In addition, the brief includes an overview of IDPs’ and returnees’ use of negative coping strategies to sustain their needs, including reliance on humanitarian assistance.

The analysis draws primarily upon IOM’s General Population Survey (GPS), Round 17 (August 2024);6 REACH’s 2024 Multi-Sector Needs Assessment (MSNA); and IOM’s study ‘From place to place: community perception of displacement and durable solutions in Ukraine’ (2024), a qualitative participatory study focusing on community perceptions of displacement and durable solutions. Given the different methodologies used in the three assessments, the data are not directly cross-referenced but instead used for triangulation and to complement each other.

The questions related to the degree of difficulties accessing adequate accommodation, basic services, food, financial compensation in case of violent incidents, as well as participating in public affairs requested the respondents to score the level of difficulties faced from 0 (no access/ participation at all) to 10 (very easy access/participation). Answers were then aggregated into three severity categories: high (scores 0 to 4), medium (5), low (6 to 10), with ‘high’, ‘medium’ and ‘low’ indicating the level of difficulties in the relevant area. The question regarding security incidents requested the respondents to score the frequency with which they experienced serious security incidents, from 0 (never) to 10 (always). Answers were then aggregated into three severity categories: high (scores 6 to 10), medium (5) and low (0 to 4).

Limitations: Those currently residing outside the territory of Ukraine were not interviewed, following active exclusion. The sample frame is limited to adults that use mobile phones, in areas where phone networks were fully functional for the entire period of the survey. People residing in the Autonomous Republic of Crimea (ARC) or the occupied areas of Donetska, Zaporizka, Luhanska, and Khersonska Oblasts were not included in the survey.

2 The analysis presented in this brief is based on the data collected in Round 17 (August 2024) of the GPS. Population estimates from the latest available data (Round 18, October 2024) are used in the introduction to provide updated information about population movements and intentions.

3 ReDSS, Durable Solutions Framework (2024), available here

4 The Joint Analytical Framework for Durable Solutions in Ukraine has not been endorsed yet. The present brief has been aligned as much as possible with the JAF. However, there remain discrepancies in the structure and wording of criteria and sub-criteria, due to the fact that the JAF had not been finalized yet at the time of the analysis.

5 For more information about the Durable Solutions Analytical Framework see JIPS, Durable solutions analysis guide (2018, available here

6 Rounds 14 through 16 were also used to compile the trend analysis. By contrast, Round 18 is referred to in the introduction and in footnotes throughout the brief as it provides the most updated population figures, however, it is not used in the main analysis as it did not include questions on durable solutions. Data and analysis for Round 18 are available here: Internal displacement report Returns report

KEY FINDINGS

IDP AND RETURNEE PREFERENCES:

More than two-thirds (69%) of IDPs planned to stay in their current location in the medium term (beyond the three months following the interview). Of these, around half intended to settle and integrate (47%, or est. 1,187,000 individuals).

• Kyiv City had the highest proportion of IDPs (48%) intending to remain and integrate, while one-third (33%) of IDPs in Kharkivska Oblast expressed similar intentions.

• Older IDPs (aged 60 and above) more commonly expressed the intention to return to their place of habitual residence. By contrast, younger individuals and IDPs living with children were more likely to intend to remain and integrate in their current location, including to ensure the children’s security. Individuals who had been displaced for more than two years and who reportedly moved to their current location to be closer to family and friends were also overrepresented among IDPs intending to remain and integrate.

In contrast, 14 per cent of IDPs aimed to return to their area of origin and 5 per cent planned to relocate elsewhere. Among those intending to return, the majority (63%) stated they would do so after the war ends.

Among returnees, the majority (87%) intended to remain in their current location.

Durable Solutions Pathways: Approximately 1.2 million IDPs were estimated to be on the ‘integration pathway’,7 while the current stock for the ‘return pathway’8 was estimated at 3.8 million returnees. A further 1 million IDPs had yet to determine a suitable durable solutions pathway as of August 2024.

Support for local integration: Both qualitative and quantitative data collected by IOM highlighted the importance of stable housing and sustainable livelihoods as pre-requirements to achieve integration. Among IDPs planning to integrate, 36 per cent required support to access secure, affordable housing, while 22 per cent mentioned that they needed support for income generation in order to settle in their current location. Additionally, 20 per cent needed support to access healthcare and essential services, reflecting the strain on services in displacement areas. Only 19 per cent of IDPs from this group reported not needing any type of support for integration.

Housing Challenges: IDPs (22%) faced greater challenges in accessing adequate housing compared to returnees and host populations (7% both), which can be predominantly attributed to the cost of renting in areas of displacement. Vulnerable IDP and returnee groups—such as those with disabilities, or with an household income per person below the national subsistance minimum9 reported higher housing barriers. Obstacles to accessing housing were found to correlate with different displacement solutions: IDPs facing strong barriers accessing adequate housing were less likely to plan to integrate in their current location (28%) compared to those facing no or lower barriers (34%). This highlights the critical role of adequate accommodation in shaping mobility decisions in the future.

Employment Disparities: Working-age IDPs, especially recent arrivals, reported higher unemployment rates (28% of IDPs displaced for up to three months) compared to returnees (11%) and host populations (10%). Employment status appeared to be correlated with medium-term intentions, as IDPs in paid work (37%) were more likely to plan integration than the unemployed (29%).

Other displacement-related vulnerabilities: For both IDPs and returnees, frequent experience of security incidents did not correlate with a higher propensity to leave10 their current location. On the other hand, IDPs experienced higher rates of family separation (30%) compared to both returnees (19%) and the non-displaced population (15%). Individuals in separated households less commonly planned to integrate in their current location (28%) compared to respondents in households that were either fully reunited households or had not separated (34%).

1. PROFILE OF THE DISPLACED POPULATION

Displacement affects different groups and individuals differently. Demographic traits such as age, gender and disability, and displacement-related characteristics as, for example, length of displacement may impact the ability of IDPs and returnees to achieve durable solutions, as well as influence

1.1 DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE

Among both IDPs and returnees, the majority (58%) were women. The prevalence of self-reported disabilities among respondents was consistent across both groups at 12 per cent.

1: Among IDP and returnee only households, household age composition

their priorities and preferences. The following sections outline the demographic and displacement profile of the populations of interest and highlight key attributes that are used throughout the brief to identify the most vulnerable groups, with the objective to support efficient targeting.

HOUSEHOLD COMPOSITION

Two per cent of IDPs reported living in households with infants (younger than one year), 14 per cent reported living with children aged 1–5, and 36 per cent reported children aged 6–17. Similar proportions were reported among returnees, with 2 per cent reporting living in households with infants, 13 per cent reporting children aged 1–5, and 39 per cent reporting children aged 6–17.

Fifty-one per cent of IDPs reported having elderly members in their household, compared to 47 per cent of returnees, and 56 per cent among the non-displaced. Thirty per cent of IDPs reported having people with disabilities in their households, the same proportion as among returnees (30%), and slightly higher than among the non-displaced (27%). Forty-three per cent of IDPs reported having chronically ill people in their households, compared to 42 per cent of returnees, and 40 per cent among the non-displaced population. Single-parent households were more prevalent among IDPs (8%) compared to both returnees (4%) and the non-displaced (3%).

1.2 DISPLACEMENT PROFILE

DURATION OF DISPLACEMENT AND TIME SINCE RETURN

A significant majority of IDPs (82%, i.e. approximately 3 million) had been displaced for more than a year as of August 2024. Of these, 64 per cent had been displaced for more than two years.

At the time of return, 10 per cent of returnees had been displaced for a year or longer (425,000). Over two-thirds of returnees (70%) had returned a year or more before the time of interview.

Figure

Figure 3: % of returnees by time since return

Figure 2: % of individuals by type of settlement and displacement status

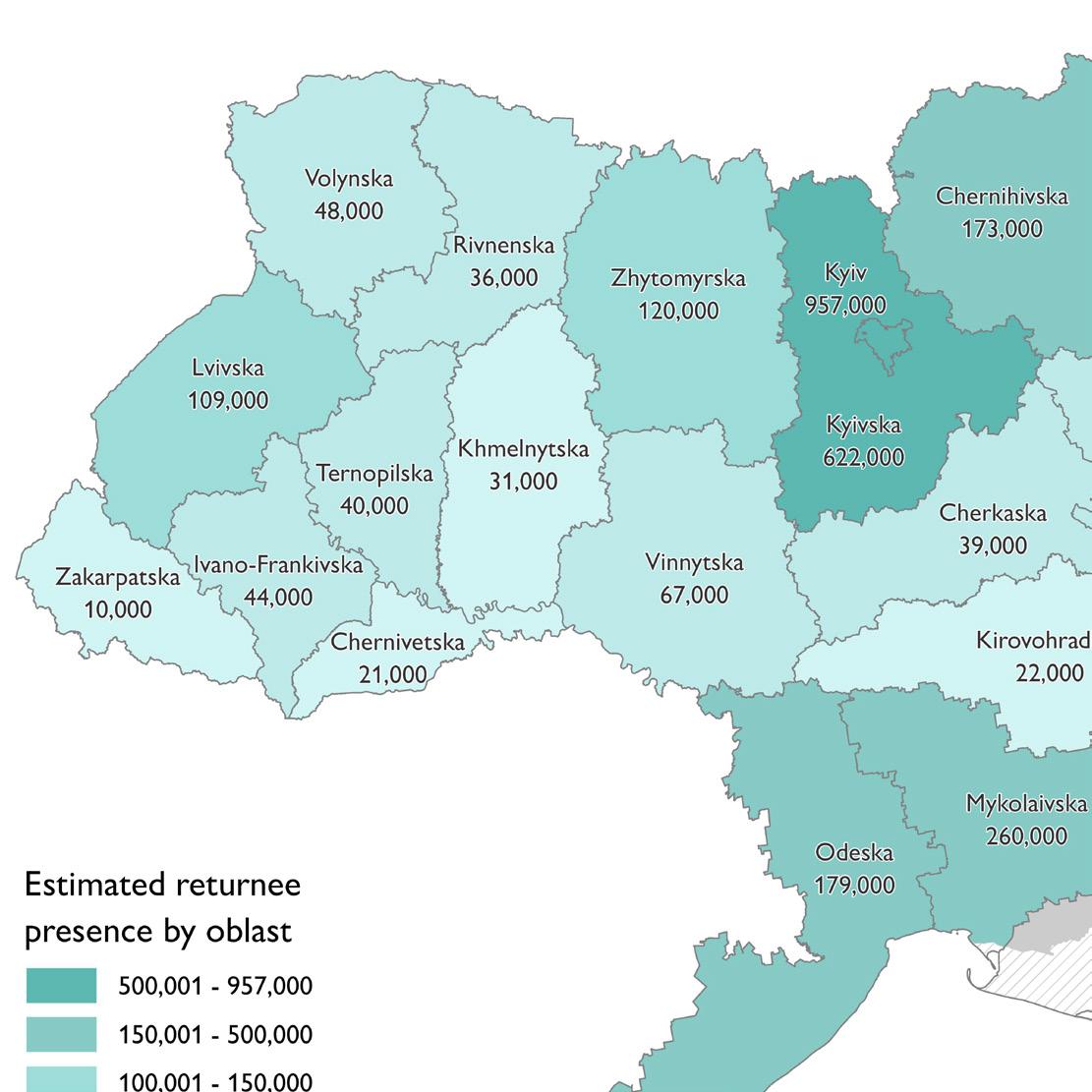

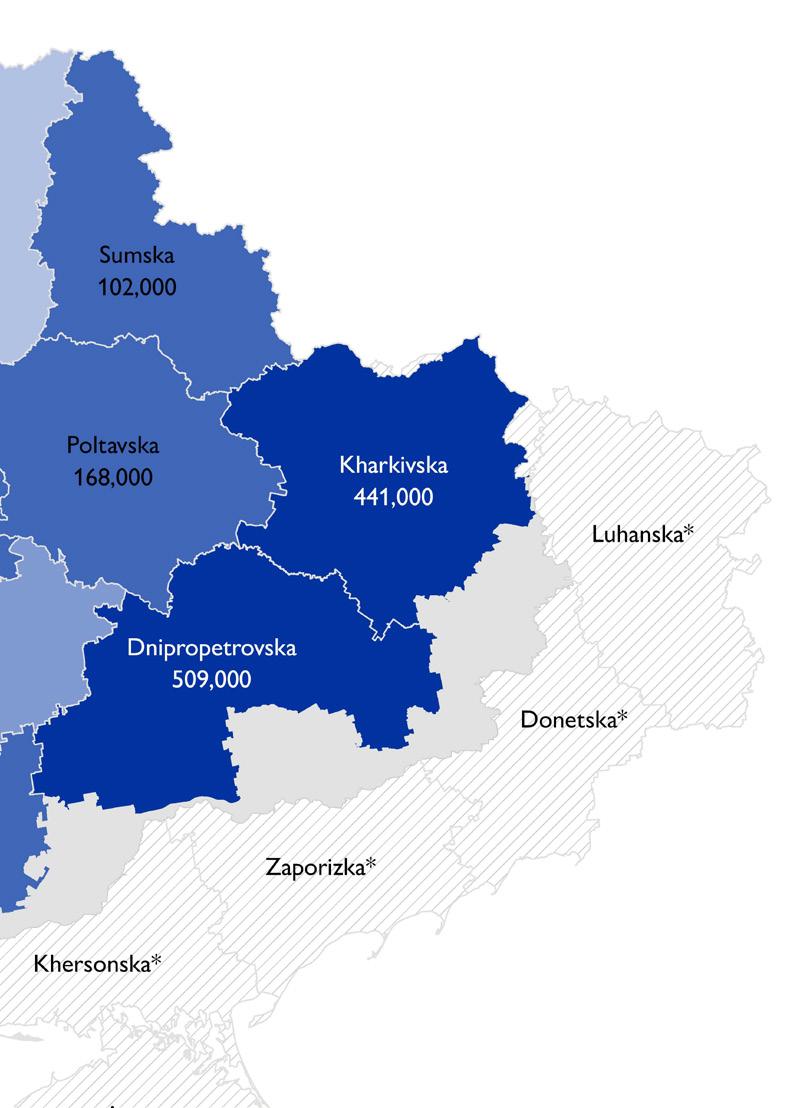

GEOGRAPHICAL DISTRIBUTION OF IDPS AND RETURNEES

The largest numbers of IDPs resided in Kharkivska (467,000 individuals, 13% of IDPs) and Dnipropetrovska Oblasts (455,000 individuals, 12%). Kharkivska Oblast also hosted the second highest share of returnees (16%, 698,000) after Kyiv City (22%, 949,000).

At the time of data collection, 37 per cent of returnees and 30 per cent of IDPs were residing in frontline raions.11

Maps 1 and 2: Estimated de facto IDPs and returnee presence by current oblast, as of October 2024

OBLAST OF ORIGIN

Two-thirds of IDPs (67%) originated from the Eastern macro-region12, followed by 17 per cent from the Southern macro-region13. The main oblasts of origin were Donetska (24%), Kharkivska (20%), Zaporizka (12%), Khersonska (12%), and Luhanska (7%) Oblasts. These oblasts accounted for 75 per cent of the total IDP population, equivalent to approximately 2,757,000 individuals.

REASONS FOR DISPLACEMENT AND RETURN

For IDPs, the security situation was the main driver of displacement (80%) and a key factor in choosing the location of displacement (35%). Other significant reasons for selecting the current place of residence included proximity to family and friends (31%) and livelihoods opportunities, particularly in Kyiv City (17%) and Kharkivska Oblast (15%).14 Male IDPs were more likely to mention livelihoods opportunities as a factor influencing their choice (14%) compared to female IDPs (6%).

DISPLACEMENT TRENDS

The overall IDP and returnee share has remained relatively stable since September 2023, indicating that the displacement crisis in Ukraine has entered a more stable and protracted phase. In 2024, displacement movements have been more concentrated, Intensification in military operations,

Returnees cited sentimental reasons (26%), proximity to relatives and friends (18%), and perceived improvements in security (17%) as primary reasons for returning to their area of origin. When leaving their previous location, returnees were primarily influenced by the inability to earn money or find suitable employment (19%), indicating that lack of sustainable livelihoods is influencing returns, followed by distance from relatives and friends (17%) and lack of affordable accommodation (16%).

indirect fire and long-range attacks have driven several notable waves of displacement - predominantly from and to locations in frontline oblasts. In national aggregate estimates, these displacement movements have been balanced by returns.

2. DURABLE SOLUTIONS PATHWAY PREFERENCES

2.1 DURABLE SOLUTIONS PATHWAY PREFERENCES

DURABLE SOLUTIONS PATHWAY PREFERENCES

More than two-thirds of IDPs (69%) planned to remain in their current location in the medium term (beyond the three months following the interview).15 Of these, 47 per cent intended to settle and integrate there. By contrast, 14 per cent of IDPs indicated the intention to return to their area of origin in the medium term, while 5 per cent planned to move elsewhere. Among IDPs intending to return to their area of origin over the same timeframe, the majority (63%) reported that they would return once the war is over. This underscores the protracted nature of the displacement crisis and reflects the awareness by the displaced populations of the enduring obstacles to return.

A significant share of IDPs (27%) expressed uncertainty about their plans, either regarding whether to remain in the area where they currently reside or not or, in the first case, whether to integrate there.

In comparison, returnees demonstrated greater unanimity in their plans, with 87 per cent expressing an intention to remain in their current location. This group also exhibited lower levels of uncertainty, as only 6 per cent were unsure about the possibility of relocating in the short or medium term.

AN END TO DISPLACEMENT: CHOOSING A PATHWAY

In 2024, IOM conducted a participatory study focusing on community perceptions of displacement and durable solutions (“From Place to Place”). The study highlighted that, regardless of the chosen pathway — return, integration or resettlement — there was a unanimous emphasis on the importance of

12 The Eastern macro-region encompasses Dnipropetrovska, Donetska, Kharkivska, Luhanska, Zaporizka Oblasts.

13 The Southern macro-region encompasses the following oblasts: Khersonska, Mykolaivska, Odeska Oblasts.

14 Representative findings are not available for all oblasts.

Figure 5: Among IDPs considering returning to their place of origin beyond the 3 months following data collection, % reporting when they are thinking of returning

In the next 3-6 months

In the next 3-6 months

In more than one year

In

In more than one year After the

In the next 6-12 months

After the war is over

(I don’t' know yet/Depends on situation)

(I don’t' know yet/Depends on situation)

physical safety, underscored by a collective desire for an end to the war, seen as a ‘victory’, as a foundational element for any solution.

Across generational lines, older IDPs often expressed a stronger desire to return to their original homes. This sentiment aligns with GPS data indicating that older IDPs (aged 60 and above) more commonly expressed the intention to return to their place of habitual residence

15 The phrasing of the question requested the respondent to report their movement intentions beyond the three months immediately following the interview. Throughout the brief, this timeframe is referred to as “medium period”, as it excludes short-period intentions (for the three months following the interview). However, no distinction was made in the questionnaire between intentions in the medium-term and long-term plans (e.g. when the war ends), hence, the expression “medium period” refers to intentions that go beyond immediate plans but do may change in the long period in case of radical changes in the situation (e.g. end of the war). This reflects the current uncertainty among IDPs and their inability in most cases to plan for the long period. In the case of IDPs who express the intention to return to their area of origin in the medium period, a follow up question investigated when they were expecting to return (see next figure).

(see Table 1 below). Meanwhile, younger individuals approached durable solutions from a different perspective, considering factors such as livelihood prospects and the well-being of their children. Notably, IDP families with children cited them as a motivation to stay - predominantly to keep them from harm’s way, which is also reflected in the overrepresentations of this type of households among IDPs intending to remain and integrate in their current location (see Table 1 below).

Although many IDPs intended to return home, they acknowledged the challenges of achieving this aspiration due to the current situation. At

the same time, those considering local integration at their displacement site were as much driven by the absence of alternative options as they were by a sense of satisfaction or belonging in their area of displacement. For IDPs contemplating local integration, establishing a sense of belonging, adapting to their surroundings, finding stability in daily lives, and developing regular routines, including work and education for children, were crucial considerations. According to the same study, those who had made progress towards achieving some of these goals since arriving appeared more likely to opt for this pathway.

Table 1: Profile of IDPs by durable solutions preference

Table 2: Profile of returnees by durable solutions preference

2.2 SOLUTIONS PATHWAY STOCK FIGURES

Table 3: Estimated stock of individuals by displacement status and by current and projected durable solutions pathway (based on reported preferences)

stock: IDPs and returnees

3,669,000 est.18

Current stock: IDPs in displacement and on durable solutions pathways

IDPs in displacement

IDPs on the pathway to durable solutions

IDPs in displacement Integration pathway

IDPs in location of displacement who intend to remain in their current location but not integrate OR intend to leave their current location (but not return to their area of origin) beyond 3 months

IDPs in location of displacement who reported the intention to remain in their current location for at least the next 3 months AND integrate

Individuals in displacement Integration pathway

Returnees who reported the intention to leave their current location after at least 3 months + host population who reported the intention to leave their current location after at least 3 months

NA (no difference between this and the above)

Return pathway

Returnees who reported the intention to remain in their current location for at least the next 3 months

Return pathway

IDPs in location of displacement who reported the intention to return their current location after at least 3 months

2.3 LOCATIONS OF DISPLACEMENT AND SOLUTIONS20

Integration pathway

Kyiv City was the location with the highest proportion of IDPs intending to remain and integrate (48%, equivalent to an estimated 178,000 individuals).

Table 4: % and estimated number of IDPs per top 6 oblasts of displacement, by medium-term intentions, plans to integrate, and presence in frontline raions

B. Return pathway

Regardless of the share of returnees residing there, the oblasts with the highest proportion of returnees intending to remain in the medium period were Odeska (96%), Kyiv (93%), Chernihivska (92%) and Kyivska (91%) Oblasts. Among the top oblasts of return, in August 2024, Donetska had the lowest percentage of returnees intending to stay in the

medium term (63%). As in the case of IDPs, a significant proportion of returnees to Kharviska Oblast (88%) planned to remain in their current location during this timeframe, despite the proximity to the frontline.

Approximately one-fifth of IDPs from Khersonska (22%) and Kharviska (20%) oblast reported the intention to return to their area of origin in the medium term.21

Table 5: % and estimated number of returnees per top 8 oblasts of return, by medium-term intentions and presence in frontline raions

The analysis in this brief focuses on the following five regions: Kyiv City, Kyivska, Dnipropetrovska, Kharkivska, Odeska and Lvivska Oblasts. This list encompasses the three top locations per proportion of IDPs (Kharkivska and Dnipropetrovska Oblasts and Kyiv City) and returnees (Kyiv City, Kharkivska and Kyivska Oblasts), as well as Odeska Oblast, as the location with the highest percentage of IDPs intending to integrate in the medium-term. Additionally, Lvivska Oblast was included in the

RETURNS TO KHERSONSKA OBLAST

Khersonska oblast was the fourth highest oblast of origin per proportion of IDPs (12% of all IDPs, or 432,000 individuals). In August 2024, it hosted only 2 per cent of all returnees, or approximately 100,000 individuals.

Among IDPs who reported the intention to return to Khersonska Oblast beyond the three months following the interview, the majority (63%) intended to return once the war is over. However, 14 per cent expressed the intention to return within the six months following data collection (estimated approximately 13,000 people). Almost

21 To be noted that data for this indicator were non-representative for most oblasts.

22 The margin of error for the analysis presented in this section was 13%.

analysis as the location with the highest returnee and IDP populations in the Western macro-region and a high proportion of returns from abroad (53%). The achievement or not of integration in Lvivska Oblast is more strictly connected to cross-border movement compared to the oblasts mentioned above, hence the inclusion of this region allows the brief to provide a more comprehensive picture of the displacement crisis in Ukraine.

40 per cent of IDPs from Khersonska oblast who intended to return in the medium term were residing in Odeska (20%) and Mykolaivska (17%) Oblasts at the time of the interview.22

Khersonska Oblast remains acutely conflict-affected with areas under the temporary occupation by the armed forces of the Russian Federation. It is not considered a feasible location for sustainable return and reintegration and is therefore not included in the analysis, despite the relatively high proportion of IDPs who reported the intention to return at some point in the future.

2.4 SUPPORT FOR SOLUTIONS (INTEGRATION PATHWAY)

Approximately one-third (36%) of IDPs planning to settle and integrate in their current location in the medium term reported that they needed support to access secure and affordable housing, while one-fifth mentioned needing assistance to increase their ability to generate income from paid work or business (22%). Additionally, 20 per

cent mentioned needing support to access healthcare or other essential services (20%), reflecting the increased pressure on the service system in areas of displacement, while 18 per cent of IDP households with children requested support to enable access to education. Finally, 13 per cent expressed a need for psychosocial assistance. 23

6: % of IDPs planning to settle and integrate in their current location beyond the three months following the interview, by top 3 support needs and macro-region24

don’t' know yet/Depends on situation)

Support to access secure and affordable housing Assistance increasing the ability to generate income from paid work or business

Consistent with these findings, IOM’s From Place to Place study highlighted the importance of stable housing and sustainable livelihoods as pre-requisites to achieve integration and highlighted their interlinkage in the Ukrainian context. Participants in the study notably emphasized

Support to access healthcare and/or other essential services

stability as a central theme in discussions about livelihoods, stressing the importance of secure employment for achieving integration. In addition to providing financial security, stable jobs were perceived as essential for re-establishing a sense of normality.

COMPOUNDING FACTORS INFLUENCING THE SUPPORT NEEDED FOR IDP INTEGRATION

In certain areas, IDPs’ length of displacement was found to be correlated with different levels of support needed for integrating in the current location. Remarkably, 26 per cent of IDPs displaced for up to a year expressed a need for support in accessing basic services (as opposed to 19% of those displaced for longer), which may indicate that relatively recently arrived individuals lack information or documentation to access services. By contrast, the level of support required to find housing was found to increase with the length of displacement, from 25 per cent of those displaced for up to a year to 38 per cent of those displaced for longer, possibly pointing at difficulties finding permanent housing solutions.

Among those crossing back from abroad but remaining in internal displacement in Ukraine, individuals who intended to integrate in their current location displayed a different support profile

compared to those internally displaced. Notably, among this subset, assistance to increase their ability to generate income from paid work or business was the most reported type of support needed (33%, compared to 21% of those who were displaced within the country), while housing assistance was only the second most reported type of support needed (31%, compared to 36% of those who were displaced within Ukraine).

Reported support needs were also found to vary significantly based on the type of settlement, with IDPs in large cities reporting a disproportional need for housing (44%). However, if individuals in rural settlements were less likely to report needing support in this area (19%), they more commonly mentioned needing support for winterization (25%), indicating that accommodation may be accessible but not necessarily adequate.

23 The question presented the respondent with a set of pre-defined assistance needs, hence it is possible that some categories of support were not captured. 24 Data for Kiyv City were not representative.

Central macro-region: Cherkaska, Kirovohradska, Poltavska, Vinnytska Oblasts. Western macro-region: Chernivetska, Ivano-Frankivska, Khmelnytska, Lvivska, Rivnenska, Ternopilska, Volynska, Zakarpatska Oblasts. Northern macro-region: Chernihivska, Kyivska, Sumska, Zhytomyrska Oblasts.

Figure

Center East North South West

Figure 7: % of IDPs reporting support needed to integrate in their current location, by type of support (top 5 most reported options) and type of settlement (I

Center East North South West

No major variations were observed based on the macroregion of current residence of IDPs. Conversely, IDPs from different oblasts of origin tended to report different levels of support with regards to housing. Looking at the five top oblasts of origin of IDPs,25 the prevalence of reported needs in this area was lowest among respondents from Kharkivska Oblast (24%) and highest among respondents displaced from Luhanska (50%) and Donetska (48%) Oblasts. This may reflect the different displacement patterns from these regions, as well as the correlation (described earlier in this section) between lengthier displacement and higher need for housing support. Indeed, virtually all IDPs from Luhanska Oblast (99%) had spent more than a year in

displacement at the time of data collection, as opposed to 75 per cent of IDPs from Kharviska Oblast.

Levels and types of support required did not vary meaningfully between men and women, with the exception of support needed for winterization (reported by 15% of women and 7% of men) and to enable children’s access to education (10% of women and 5% of men).

By contrast, age correlated with significant differences in the reported levels and type of needs, with almost a third (29%) of elderly respondents highlighting a need for support in accessing healthcare and other essential services.

While reported needs for support to secure housing decreased among the oldest group, it should be noted that women aged 60+ reported needs in this area almost twice as often as men (30% and 17% respectively).

Households with children were significantly less likely to state that they would not need any support to integrate in their current location (13% as opposed to 24% of households without children). Remarkably, this type of household expressed higher needs for support with access

3. CRITERIA ANALYSIS

When comparing the situation of IDPs and returnees with that of the non-displaced population for each of the sub-criteria listed below, the most important percentage variation was found with regards to housing (criterion 1.1). Indeed, IDPs were more than three times (214%) more likely to face a high degree of difficulties accessing accommodation compared to the non-displaced population, highlighting this as a key displacement-related vulnerability. The prevalence of family separation (criterion 7.1) also appeared to be intimately connected with displacement, with IDPs being 100 per cent more likely to report that their household had not reunited yet compared to the

to housing (40% compared to 32% of households without children), an area where single-parent households also reported significantly higher needs for support to integrate (52% compared to 34% of non-single parent households).

As can be expected, the need for support to access healthcare and other essential services was particularly high among households with at least one elderly individual (26%), as well as with people with disabilities (28%) and chronic illnesses (30%).

non-displaced population. Finally, the unemployment rate appeared to vary significantly based on displacement status, as IDPs were 50 per cent more likely to report being unemployed compared to the non-displaced.27

Returnees’ outcomes across the sub-criteria were similar to those of the non-displaced population, indicating a limited prevalence of displacement-driven vulnerabilities among this group. Nevertheless, returnees appeared to be disproportionally affected by war-related security incidents (reported by 45% more returnees than nondisplaced).

25 Donetska, Kharkivska, Khersonska, Luhanska, and Zaporizka Oblasts.

26 Results for the age group 18-24 were not included as non-representative.

27 While the sub-criteria related to lack of sufficient food also saw notable percentage variations between the displaced and non-displaced, this information should be considered carefully given the self-reported, subjective character of the indicator.

Figure 8: % of IDPs reporting support needed to integrate in their current location, by type of support (top 5 most reported options) and age of respondent26

Table 6: Outcomes across durable solutions sub-criteria; by displacement status

Criterion 1: Adequate standards of living

Pillar 1:

Socioeconomic integration

Criterion 2: Livelihoods

Criterion 3: Security and protection

Criterion 4: Access to remedies

Pillar 2:

Security and access to justice

Pillar 3: Community integration and engagement

Criterion 5: Access to effective mechanisms to restore HLP

Criterion 6: Access to documentation

Criterion 7: Voluntary reunification

Sub-criterion 1.1: High level of difficulties accessing adequate accommodation29

Sub-criterion 1.2: High level of difficulties accessing basic services30

Sub-criterion 1.3: Reported lack of access to sufficient food31

Sub-criterion 2.1: Unemployment32

Sub-criterion 2.2: Income below national subsistance minimum (up to UAH 7,064)33

Sub-criterion 3.1: Frequent experience of serious war-related security incidents34

Sub-criterion 4.1: High level of difficulties accessing financial compensation if affected by war-related violence35

Sub-criterion 5.1: No access to HLP compensation (among those who applied, the application was rejected)36

6.1: Lack of personal documentation37

Sub-criterion 6.2: lack of IDP registration38

Sub-criterion 7.1: Incidence of family separation39

Criterion 8: Community engagement and social cohesion Sub-criterion 8.1: High level of difficulties participating in public affairs40

8.1: Social cohesion

Legend:

The variation compared to the host population is below 25 per cent

The variation compared to the host population is between 25 and 49 per cent

The variation compared to the host population is between 50 and 74 per cent

The variation compared to the host population is 75 per cent or higher

28 For more information on how the scores for indicators in this table were calculated, please refer to the methodology section at the end of the brief.

29 ”How easily can you access adequate accommodation?”.

30 “How easily can you access basic services, such as drinking water, sanitation, health care, schooling, communication networks, etc.?”.

31 ”Do you currently lack sufficient food to meet your basic needs?”. It should be noted that the question did not specify the meaning of ’basic needs’, hence it is possible that respondents over-reported needs for food.

32 ”How would you describe your employment status in the last seven days?”. The unemployment rate is only calculated for the population of working age (18 to 60).

33 ”Please tell me which of these intervals corresponds to the total monthly income of your household now since the beginning of the war?”; the indicator is calculated by using the national subsistance minimum of (UAH 7,064).

34 “How often do you experience serious security incidents as a result of the war?”.

35 ”How easily can you access financial compensation if you have been directly affected by violence during the war?”.

36 ”Have you or anybody in your household applied for the government’s e-Restoration (e-Vidnovlennia) scheme?”, followed by ”To the best of your knowledge, what is the status of your application?’

37 ”Can all members of your household access their official personal documents such as national passports or personal ID cards if needed?”.

38 ”Do you have a valid registration (certificate) of an internally displaced person?”.

39 Composite indicator based on the questions: ”Has your household stayed together during the war?” and ”Has your household already reunited?”.

40 ”How easily can/could you participate in public affairs /resolving community issues?”.

41 ”Please let me know if in the last 30 days, you or your household members currently living with you had to do any of the following (list of startegies) in order to meet your household basic needs?”.

Among both IDPs and returnees, different preferences appeared to be correlated with different vulnerability profiles, based on the eight IASC durable solutions criteria. Thus, for example, returnees who planned to remain in their current location in the medium term

7: Outcomes across durable solutions sub-criteria, by displacement status

Pillar 1: Socio-economic integration

Criterion 1: Adequate standards of living

were significantly more likely to report a household income per person below the national subsistance minimum, highlighting the importance of livelihoods interventions targeting this population group.

Sub-criterion 1.1: High level of

1.3:

Criterion 2: Livelihoods Sub-criterion 2.1: Unemployment

Sub-criterion 2.2: Income below national subsistance minimum (UAH 7,064)

Criterion 3: Security and

Criterion 4: Access to remedies

Pillar 2:

Sub-criterion 3.1: Frequent

Sub-criterion 4.1: High level of difficulties accessing financial compensation if affected by war-related violence

Criterion 5: Access to effective mechanisms to restore HLP Sub-criterion 5.1: Lack of access to HLP compensation (application is rejected)

Criterion 6: Access to documentation Sub-criterion 6.1: Lack of personal documentation

Sub-criterion 6.2: No IDP registration 24% 15% - -

Pillar 3: Community integration and engagement

Criterion 7: Voluntary reunification

Criterion 8: Community engagement and social cohesion

Sub-criterion 7.1: Incidence of family separation

Sub-criterion 8.1: High level of difficulties participating in public affairs

Sub-criterion 8.2: Social cohesion

42 Any results with a higher margin of error were excluded (denoted as ‘-’).

Table

3.2 CRITERIA

PILLAR 1: SOCIO-ECONOMIC REINTEGRATION

CRITERION 1: ADEQUATE STANDARDS OF LIVING

SUB-CRITERION 1.1 HIGH LEVEL OF DIFFICULTIES ACCESSING ADEQUATE ACCOMMODATION

Displacement status and profile

Access to adequate accommodation presented significant challenges for IDPs (22%) compared to returnees and the host population (7% each). The length of displacement was not found to correlate with meaningful variations in the level of difficulty accessing adequate accommodation. By contrast, registration as an IDP was associated with a higher level of difficulties, which may reflect the fact that the registration rate is lower among higher-income individuals (72%, compared to 87% among IDPs with a household income per person below the subsistance minimum).

Among both IDPs and returnees, those living in rural areas were more likely to report facing strong challenges accessing housing (29% of IDPs and 15% of returnees), compared to those living in large cities (19% and 4% respectively). While a similar pattern was observed for the non-displaced population, the proportion of individuals reporting these challenges in the two types of settlements (10% and 4%) was lower compared to both IDPs and returnees.

The prevalence of obstacles accessing accommodation appeared to be consistent across the country for both population groups, with the exception of Kyiv city and the Northern macro-region, where lower levels were recorded (13% and 19% of IDPs respectively).

By demographic characteristics:

Among IDPs, individuals with self-reported disabilities (30%), as well as those living in households with chronically ill members (26%) were significantly more likely to report high levels of difficulties in this area compared to IDPs without disabilities (20%) and with no chronically ill family members (18%), indicating the importance of specifically targeting these categories with housing support. Additionally, both IDPs (24%) and returnees (11%) living in lower-income families appeared to struggle with accessing adequate accommodation at a significantly

higher proportion compared to those reporting a household income per person above the subsistance minimum (16% and 2% respectively).

By durable solutions preference and location:

Obstacles to accessing housing were correlated with lower propensity to remain in the current location for both IDPs and returnees. Indeed, 28 per cent of IDPs facing a high degree of difficulties accessing accommodation reported the intention to remain and integrate in their current location, as opposed to 34 per cent of those encountering few or no difficulties in this sense. This highlights the critical role of adequate accommodation in shaping medium-term decisions and reflects the importance attributed to housing by participants in the From Place to Place study, who emphasized how the provision of housing would substantially influence their decision to remain in the current location.

“Housing provides permanence, a kind of certainty that this is yours and is your home” 43

Other indicators

The majority of respondents to the MSNA reported living in individual accommodations occupied by a single household, including 82 per cent of IDPs and 94 per cent of returnees. However, 17 per cent of IDP respondents resided in shared dwellings, collective accommodations, or were hosted by relatives or friends. Ownership of housing was limited among IDPs, with only 13 per cent living in owned accommodations, while 68 per cent rented and 19 per cent were hosted for free. Concerns about eviction were prevalent among IDPs, with 12 per cent indicating they were at risk of eviction and an additional 31 per cent uncertain about their risk. In contrast, these figures were notably lower among returnees, at 5 per cent and 9 per cent, respectively.46

Kharkivska Lvivska Odeska

Figure 10: % of individuals reporting a high level of difficulty accessing adequate accommodation, by oblast and displacement status44

Trend analysis:

Figure 11: % of individuals reporting a high level of difficulty accessing adequate accommodation,

SUB-CRITERION 1.2 HIGH LEVEL OF DIFFICULTIES ACCESSING BASIC SERVICES

Displacement status and profile

The level of difficulties accessing basic services varied marginally by displacement status, with IDPs being 4 percentage points more likely to report facing high or medium obstacles in this sense compared to the non-displaced population. Among IDPs, recently displaced people reported the highest difficulties accessing basic services.47 By contrast, returnee respondents who had returned within the previous year presented similar levels of difficulties accessing services (4%) than those who had returned earlier (3%).

While IDPs generally reported consistent access to services across the country, returnees residing in the Southern macro-region were significantly more prone to encounter barriers (14%, compared to 5 per cent in the Eastern macro-region, the second per level of reported barriers). This high proportion was driven by returnees in Mykolayvska Oblast, where 25 per cent of respondents reported facing strong barriers accessing basic services, followed by Khersonska Oblast (11%).

Among both IDPs and returnees, respondents living in rural settlements more often reported struggling to access basic services (15% and 11% respectively), compared to those living in large cities (2% and 3% respectively). While the non-displaced population presented a similar pattern, the proportion of individuals facing obstacles was lower in both settings (7% in rural areas and 4% in large cities).

By demographic characteristics:

Elderly IDPs and returnees generally reported stronger difficulties in accessing basic services. This variation was particularly important in the case of returnees, with 7 per cent of respondents over 60 years old struggling to access services, compared to 1 per cent of individuals in the youngest age group (18-24). This is consistent with elderly IDPs

Figure 12: Average self-reported level of difficulty accessing basic services, by displacement status

and returnees being approximately 10 percentage points more likely to report lacking sufficient access to healthcare specifically, compared to individuals aged 18-24.

By durable solutions preference and location:

Among both IDPs and returnees, individuals who reported facing strong challenges accessing basic services were less inclined to remain in their current location in the medium term, indicating that inability to access essential services may contribute to the decision to leave the location of displacement or return. Indeed, 23 per cent of IDPs who reported struggling to accessing services intended to remain and integrate in their current location in the medium term, as opposed to more than a third (34%) of those experiencing few or no difficulties in this sense. Similarly, returnees who encountered few or no difficulties were more likely to plan to remain in their current location (88%) compared to those who faced stronger barriers (80%).

Other indicators:

Eleven per cent of IDP respondents to the MSNA had not been able to obtain healthcare when they needed it in the 3 months prior to data collection, with elderly individuals (18%) and IDPs living in rural settlements (16%) being most likely to report this inability. Among the displacement-affected individuals (IDPs and returnees) who accessed healthcare, 28 per cent reported that the cost of medicine was a key obstacle, while 16 per cent mentioned the high price of treatment, indicating the importance of addressing access to services in connection with livelihoods interventions.

Figure 13: % of individuals reporting a high level of difficulty accessing basic services, by oblast and displacement status

SUB-CRITERION 1.3 REPORTED NEED FOR FOOD

IDPs were 74 per cent more likely to report having unmet food needs compared to both returnees and the non-displaced population. Notably, they were twice as likely to be in need of food than the non-displaced population in both Kyivska (37%) and Kharkivska (36%) Oblasts.

While the length of displacement was not correlated with meaningful variations in the reported food needs of IDPs, returnees who had been displaced for more than one year before returning were almost twice as likely to report lacking access to sufficient food (32%) compared to those who had been displaced for a shorter period (18%). Additionally, food needs were found to decrease with the time spent in the location of return, with 17 per cent of returnees who had returned more than one year prior to the interview reporting being in need of food, compared to 24 per cent of those who had returned more recently. While IDPs displayed similar levels of needs across all macro-regions (with the exception of Kyiv city), returnees in the Eastern and Southern macro-regions (26% both) had significantly higher needs compared to the rest of the country.

By demographic characteristics:

For both IDPs and returnees, needs were correlated with gender and disability. Among returnees, women (21%) and persons with self-reported disabilities (27%) were respectively 40 and 50 per cent more likely to report lacking sufficient food compared to men and persons without disabilities. Household-level vulnerability factors were also associated with different levels of needs, as demonstrated by approximately half (45%) of IDPs in single-parent households having food needs.

Needs were found to be inversely correlated with income, with 38 per cent of IDPs with a household income per person below the subsistance minimum reporting being in need of food, compared to 21 per cent of those reporting higher levels of income, indicating that affordability represents a key barrier to food.

By durable solutions preference and location:

Among both IDPs and returnees, food needs did not appear to be strongly correlated with solutions preferences. Notably, the proportion of those intending to remain in their current location was found to remain stable regardless of the level of reported food needs.

Trend analysis:

Other indicators:

Reducing the quality or quantity of the food consumed was commonly reported by IDPs and returnees as a strategy to cope with insufficient means. Indeed, 63 per cent of IDPs and 55 per cent of returnees reported their household to have switched to cheaper food during the previous month to be able to meet basic needs, while 50 per cent of IDPs and 40 per cent of returnees reported that it reduced the quantity of food consumed. Notably, more than half of IDPs (56%) and returnees (52%) with a household income per person below the subsistance minimum reported that members of their household had reduced the quantity of food consumed, compared to 37 per cent of IDPs and 24 per cent of returnees reporting a higher income.

Figure 15: % of individuals reporting experiencing a lack of food to meet basic needs, by displacement status

Figure 16: % of individuals reporting experiencing a lack of food to meet basic needs, by oblast and displacement status

Figure 17: % of individuals reporting experiencing a lack of food to meet basic needs, by displacement status and GPS Round

CRITERION 2: ACCESS TO LIVELIHOODS AND EMPLOYMENT

SUB-CRITERION 2.1 UNEMPLOYMENT (WORKING-AGE POPULATION)

Displacement status and profile

Working-age IDPs were more likely to report being unemployed (15%) or out of the workforce49 (22%) compared to both returnees and the non-displaced population. Unemployment was higher for individuals who had been displaced (24%) or had returned (19%) within the year prior to the interview, compared to 13 per cent of IDPs and 7 per cent of returnees who had been in their current location for more than a year.

The geographical prevalence of unemployment differed between the IDP and returnee populations, with the former recording the highest unemployment rate in the Southern macro-region (21%) and the latter in the Eastern macro-region (18%). Additionally, returnees living in frontline areas were more than twice as likely to be unemployed (17%) compared to those residing in other parts of the country. While the unemployment rate of returnees and the non-displaced remained stable regardless of the type of settlement, unemployment among working-age IDPs was notably higher in rural areas, with 25 per cent unemployed, compared to 11 per cent among those residing in large cities.

By demographic characteristics:

Gender differences in employment rates were significantly higher among IDPs compared to other groups, with the share of employed IDP men being 48 per cent higher (71%) compared to IDP women (48%). Conversely, a quarter (25%) of working-age IDP women reported either being on parental leave or being engaged full-time in housework and care work, including childcare, as opposed to 3 per cent of IDP men. Among both IDPs and returnees, respondents with self-reported disabilities were significantly less likely to be employed,

Figure 18: % of working-age individuals (18-60) reporting employment status in the 7 days prior to data collection, by displacement status

with 37 per cent of IDPs with disabilities and 55 per cent of returnees with disabilities being employed, compared to 58 per cent and 70 per cent of IDPs and returnees without disabilities respectively.

By durable solutions preference and location:

The proportion of individuals intending to integrate in their current location was higher among those who were in paid work (37%) than the unemployed (29%), highlighting the importance of job stability as a factor supporting integration. By contrast, individuals who identified as self-employed or business owners least often expressed the intention to remain and integrate (24%), possibly due to the presence of established businesses in the area of origin. Finally, IDPs who reported engaging in full-time childcare also intended to remain and integrate to a notable extent (36%), which could be linked to the desire to offer children stability and security, as well as to the integration opportunities created by school.

Trend analysis:

Other indicators:

IDPs and returnees reported higher rates of informal work (16% of IDPs and 14% of returnees) compared to the non-displaced population (11%). Additionally, in Round 16 of the GPS (April 2024), half of IDPs in paid work reported having worked without a contract during the previous year (49%, as opposed to 38% of returnees and 42% of non-displaced), suggesting a higher vulnerability of IDPs to exploitative practices. While respondents generally reported similar challenges to finding a job regardless of displacement status, 9 per cent of IDPs mentioned that their search for a job was hindered by discrimination based on displacement status.

Figure 19: % of individuals reporting being unemployed at the time of data collection, by oblast and displacement status50

Figure 20: % of individuals reporting being unemployed at the time of data collection, by displacement status and GPS Round

SUB-CRITERION 2.2 INCOME BELOW THE NATIONAL SUBSISTANCE MINIMUM

Displacement status and profile

Levels of income below the subsistance minimum appeared to be more prevalent among IDPs (69%) compared to both returnees (56%) and the non-displaced population (64%).

IDPs displaced within their oblast of origin more often reported a household income per person below the national subsistance minimum (80%) compared to those displaced to other oblasts (65%). This reflects the vicinity of the frontline, as IDPs residing in frontline raions were both more likely to have displaced within their oblast of origin and to report lower income levels. However, this may also indicate the need for low-income individuals to remain closer to the area of work, as well as the lack of sufficient funds to move farther.

No clear correlation emerged between the length of displacement and income levels for IDPs. However, IDPs who had been displaced by three months or less were most likely to report a household income per person below the subsistance minimum (75%). By contrast, among returnees, both the length of displacement and the time since return influenced income levels, as individuals who had been displaced for more than a year prior to return and those who had returned to their area of origin within the twelve months prior to data collection were more likely to report income levels below the subsistance minimum (71% and 67% respectively), compared to those who had been displaced for shorter periods (54%) or had returned earlier (52%).

By

demographic characteristics:

Households with vulnerable members generally reported lower income levels than the general population, with a significant share of IDP and returnees in households with children (80% and 65% respectively),

Figure 21: % of individuals in HHs with income per person below the national subsistance minimum (UAH 7,064), by displacement status

elderly (78% and 67%), people with disabilities (77% and 70%) and chronically ill members (75% and 63%) reporting an available income per person below the subsistance minimum.

By durable solutions preference and location:

Income levels appeared to be correlated with durable solutions preferences for IDPs. Indeed, 39 per cent of IDPs reporting a household income per person above the subsistance minimum intended to remain and integrate in the current location, as opposed to 31 per cent of those with a lower income. The importance of financial stability in this sense was also underscored by participants in the From Place to Place study, who stressed how the revision of the IDP allowance criteria in March 202451 and its anticipated impact in terms of vulnerable IDP household’s ability to meet basic needs influenced durable solutions preferences, with IDPs previously committed to integrating now contemplating relocating abroad.

Trend analysis:

Other indicators:

Almost one-third (31%) of IDPs reported facing a high level of difficulties covering basic expenses, compared to 21 per cent of returnees and 26 per cent of the non-displaced population. Notably, IDPs who were officially registered more often reported this (33%) compared to unregistered IDPs (25%), reflecting the higher proportion of individuals reporting an available income per person below the subsistance minimum (73%) among the first group. This may indicate that income levels play a role in the decision of whether or not to register as an IDP.

Figure 22: % of individuals reporting a household income per person below the national subsistance minimum (up to UAH 7,064), by oblast and displacement status

Kharkivska Odeska Dnipropetrovska Kyivska Lvivska Kyiv

Figure

PILLAR 2: SECURITY AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE

CRITERION 3: SECURITY AND PROTECTION

SUB-CRITERION 3.1 FREQUENT EXPERIENCE OF SERIOUS WAR-RELATED

Displacement status and profile

Exposure to war-related security incidents was correlated with displacement status, with returnees being 28 per cent and 45 per cent more likely than IDPs and the non-displaced population respectively to report experiencing such incidents at a high frequency. Reported incidents were highest in the Eastern macro-region, where 83 per cent of returnees and 67 per cent of IDPs mentioned experiencing serious security incidents with a high frequency, followed by the Southern macro-region (76% and 56% respectively).

By demographic characteristics:

Among returnees, women were significantly more likely to report experiencing war-related security incidents at a high frequency (74% compared to 52% of men), which may reflect a stronger female presence in the public space, due to relatively high concerns related to mobilization among returnee men.52,53 The same pattern was observed among the non-displaced population, while no meaningful variation was recorded among IDPs.

By durable solutions preference and location

IDPs and returnees who frequently experienced security incidents as a consequence of the war did not appear to be significantly more inclined to leave their current location, compared to those

SECURITY INCIDENTS

individuals

they

who either did not experience such incidents or experienced them less often. Indeed, IDPs reporting frequent incidents were only 3 percentage points more likely to plan to return to their area of origin in the medium term (15%) compared to other IDPs (12%). At the same time, among IDPs considering returning in the medium term or not knowing what they would do, a disproportionate share felt relatively unsafe in their current location (58% of both groups), compared to those who intended to remain in their current location in the medium term, regardless of whether they intended to integrate (50%) or not (47%).

Trend analysis:

Other indicators:

According to the 2024 MSNA, the most prevalent factor affecting the sense of safety of IDP and returnee households was conflict-related violence (reported by more than half of respondents in both groups), notably in relation to its impact on civilians (54% of displaced individuals overall), private infrastructure (58%) and public infrastructure (56%). However, when asked about factors affecting the sense of security of men specifically, among returnee households, the most reported factor was conscription (reported by 55% of returnee households, as opposed to 36% of IDP households).

52 16% of returnee men actively looking for a job mentioned concerns about mobilization as a barrier to employment, compared to 10% of IDP men.

53 This variation could also result from men’s tendency to underreport security incidents.

54 The data for this indicator for the non-displaced population are only available for Round 17.

Figure 24: % of

reporting frequency with which

experience serious security incidents as a result of the war, by displacement status

Figure 25: % of individuals reporting they experience serious security incidents as a result of the war with a high frequency, by oblast and

Kharkivska Dnipropetrovska

Odeska Kyiv

Kyivska

Lvivska

Figure 26: % of individuals reporting they experience serious security incidents as a result of the war with a high frequency, by displacement status and GPS Round54

CRITERION 4: ACCESS TO REMEDIES

SUB-CRITERION 4.1 HIGH LEVEL OF DIFFICULTIES ACCESSING FINANCIAL COMPENSATION IF AFFECTED BY WAR-RELATED VIOLENCE55

Displacement status and profile

While access to financial compensation for war-related violence was limited for all population groups, IDPs most often reported difficulties in this sense, compared to returnees and non-displaced individuals. The length of displacement was not found to correlate with levels of difficulty accessing financial compensation among IDPs and returnees, nor a clear association could be identified between the degree of difficulties and the time spent in the location of return. Being registered as an IDP also did not seem to correlate with lower or higher levels of difficulties. However, IDPs in Kiev were significantly more likely to report barriers accessing financial compensation for conflict-related violence (67%) compared to the rest of the country.

By demographic characteristics:

Individuals aged between 36 and 59 years more commonly reported facing high levels of difficulties accessing compensation among both IDPs (55%) and returnees (46%), while those belonging to the youngest age group (18-24) were least likely to report obstacles (36% and 26% respectively). By contrast, no clear correlation was found between the gender of the respondents and the difficulty of accessing compensation.

By durable solutions preference and location:

Difficulties accessing financial compensation for conflict-related violence did not appear to be associated with a lower propensity to remain in the current location for either IDPs or returnees.

Other indicators:

Approximately one-fifth of IDPs (22%) and returnees (21%) reported facing strong barriers preventing them from accessing legal consultation and other types of support if directly affected by violence during the war.56 However, this proportion was found to be consistent with what was reported by the non-displaced population, among which 22 per cent mentioned they were also facing strong barriers in this area. Hence, this seems to point to general limitations to access to remedies in the case of conflict-related violence that are not displacement-specific.

Figure 28: % of individuals reporting degree of difficulty accessing financial compensation if they have been directly affected by violence during the war, by oblast and displacement status

Kyiv Odeska Dnipropetrovska Lvivska Kyivska Kharkivska

Figure 29: % of IDPs reporting degree of difficulty accessing financial compensation if they have been directly affected by violence during the war, by top 5 oblasts of origin

Luhanska Donetska Zaporizka Khersonska Kharkivska

CRITERION 5: ACCESS TO EFFECTIVE MECHANISMS TO RESTORE HOUSING, LAND AND PROPERTY (HLP) OR TO PROVIDE COMPENSATION

SUB-CRITERION 5.1 ACCESS TO MECHANISMS FOR HOUSING, LAND AND PROPERTY (HLP) RESTITUTION/COMPENSATION

Displacement status and profile

IDPs were significantly more likely to report either having applied to the government’s e-Restoration (e-Vidnovlennia) programme (18%) or not having applied despite being potentially eligible (27%), for a total of 45 per cent of IDPs indirectly reporting having conflict-related issues with their housing, compared to 18 per cent of returnees and 10 per cent of non-displaced individuals. Among IDPs, the proportion of individuals who applied to this scheme was at least ten percentage points higher in the Eastern macro-region (26%) compared to any other areas in the country. Additionally, registered IDPs were significantly more likely to have applied to this program (20%) or not to have applied despite being eligible (28%) compared to unregistered IDPs (9% and 19% respectively), who more commonly reported not being eligible as their housing had not been damaged (64%, as opposed to 42% of registered IDPs).

Of those who applied, 14 per cent of IDPs and 30 per cent of returnees received compensation, while in 20 per cent and 15 per cent of cases respectively the application was rejected.57 IDPs who had been displaced within their oblast of origin were significantly more likely to report that their application had been processed and compensation received (23%), compared to those displaced outside of it (9%). Conversely, the second subset more commonly reported that their application was still being processed (46%, compared to 29% of IDPs displaced within their oblast of origin).

By durable solutions location:

scheme, by displacement status

Yes (applied) Could apply but have not No, not applicable (no issues with housing) Not aware about this program

Don't know/refused to answer

Among both IDPs and returnees who applied to the program, more than half reported facing a high degree of difficulties accessing compensation or assistance for damaged housing, with this proportion reaching two-thirds of respondents in the case of IDPs (67%, compared to 52% of returnees). Vulnerable IDP households who applied to the scheme were also found to encounter strong difficulties, as reported by 73 and 71 per cent of respondents living with chronically ill people and persons with disabilities respectively.

Other indicators:

Figure 30: % of individuals reporting their household to have applied for the government’s e-Restoration (e-Vidnovlennia)

Figure

Dnipropetrovska Kharkivska Odeska Lvivska Kyivska Kyiv

Figure 32: % of IDPs reporting their household to have applied for the government’s e-Restoration (e-Vidnovlennia) scheme, by top 5 oblasts of origin

Donetska Kharkivska Luhanska Khersonska Zaporizka

Figure 33: % of individuals reporting HLP concerns, by most reported concerns and displacement status (Source: MSNA)

Kharkivska Luhanska Khersonska Zaporizka

CRITERION 6: ACCESS TO AND REPLACEMENT OF PERSONAL AND OTHER DOCUMENTATION

SUB-CRITERION 6.1 LACK OF PERSONAL DOCUMENTATION

Displacement status and profile

The ability to access personal documentation did not seem to be strongly correlated with the displacement or demographic profile of the respondents, with limited variations based on individual or householdlevel characteristics. However, the inability to access essential documents seemed to be reflected in more unsustainable livelihoods: 11 per cent of IDPs in households using emergency coping strategies and 15 per cent of IDPs in households whose main source of income was irregular earnings reported not being able to access their official personal documents.

Figure 34: % of individuals reporting all household members to be able to access their official personal documents such as national passports or personal ID cards if needed, by displacement status

Figure 35: % of individuals reporting some household members being unable to access their official personal documents such as national passports or personal ID cards if needed, by oblast and displacement status

Kyivska Dnipropetrovska Kyiv Odeska

Figure 36: % of IDPs reporting some household members being unable to access their official personal documents such as national passports or personal ID cards if needed, by top 5 oblasts of origin

Donetska Khersonska Kharkivska Luhanska Zaporizka

SUB-CRITERION 6.2 REGISTRATION

Displacement status and profile

The majority of IDPs (83%) reported a valid certificate as IDPs, while a remarkable 20 per cent of returnees appeared to be still registered as IDPs. Prevalence of registration was found to vary based on time and geography of displacement, with 85 per cent of IDPs displaced for more than one year at the time of data collection and outside their oblast of habitual residence being registered, compared to 73 per cent of those displaced by up to one year and 78 per cent of those displaced within their oblast of origin.

Among returnees, 36 per cent of those who had been displaced by more than a year prior to return and 24 per cent of those who had returned within the year prior to the interview were still registered as IDPs. Among IDPs, the prevalence of registration was consistent across macro-regions, with the exception of Kyiv (76%) and the Northern macro-region (74%) where it was lower.

By demographic characteristics:

Among IDPs, registration rates were higher among women (88%, compared to 74% of men) and increased with age, with 89 per cent of elderly IDPs holding a valid certificate, compared to 71 per cent of those aged 18 to 24. By contrast, returnee men were more likely to be registered as IDPs (24%) compared to women (18%).

Socio-economic vulnerabilities of IDP households were also correlated with different prevalence of registration, with individuals in households with children, chronically ill persons (both at 86%), and elderly (85%) being more likely to be registered, as well as those living in single-parent households (90%) and households only composed of women and children (87%).

By durable solutions preference:

No

know)

Registration appeared to be strongly correlated with durable solutions preferences, with almost half of unregistered IDPs intending to remain and integrate in their current location (47%) compared to less than a third of IDPs holding a valid certificate (30%). This difference may be driven by the specific profile of registered IDPs, who tended to be older (31% were aged 60 years or above, compared to 18% of unregistered IDPs), less often employed (41% against 57% of unregistered IDPs), and to have a lower income (73% lived in households with an income per person below the subsistance minimum, as opposed to 50% of unregistered IDPs), all variables correlated with a reduced propensity to integrate.

Figure 37: % of individuals registered as IDPs, by displacement status

Figure 38: % of IDPs reporting not having a valid certificate (registration) as IDPs, by top 5 oblasts of origin

Kharkivska Khersonska Zaporizka Donetska Luhanska

CRITERION 7: VOLUNTARY REUNIFICATION