MEDICINE

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE HEALTH SCIENCE CENTER

Advancing Care and Discovery in Tennessee

Dear Friends and Colleagues,

The University of Tennessee Health Science Center’s College of Medicine has long been a vital force for the health of our state. For generations, we have trained physicians who serve Tennesseans with skill, compassion, and integrity. I continue to be filled with optimism about the extraordinary opportunities that lie ahead.

That optimism begins with leadership. We are proud to welcome our new Executive Dean of the College of Medicine, Dr. Michael Hocker, whose vision and energy will guide us into our next chapter. With a deep commitment to education, research, and clinical care, his leadership will strengthen our mission and expand our impact across Tennessee.

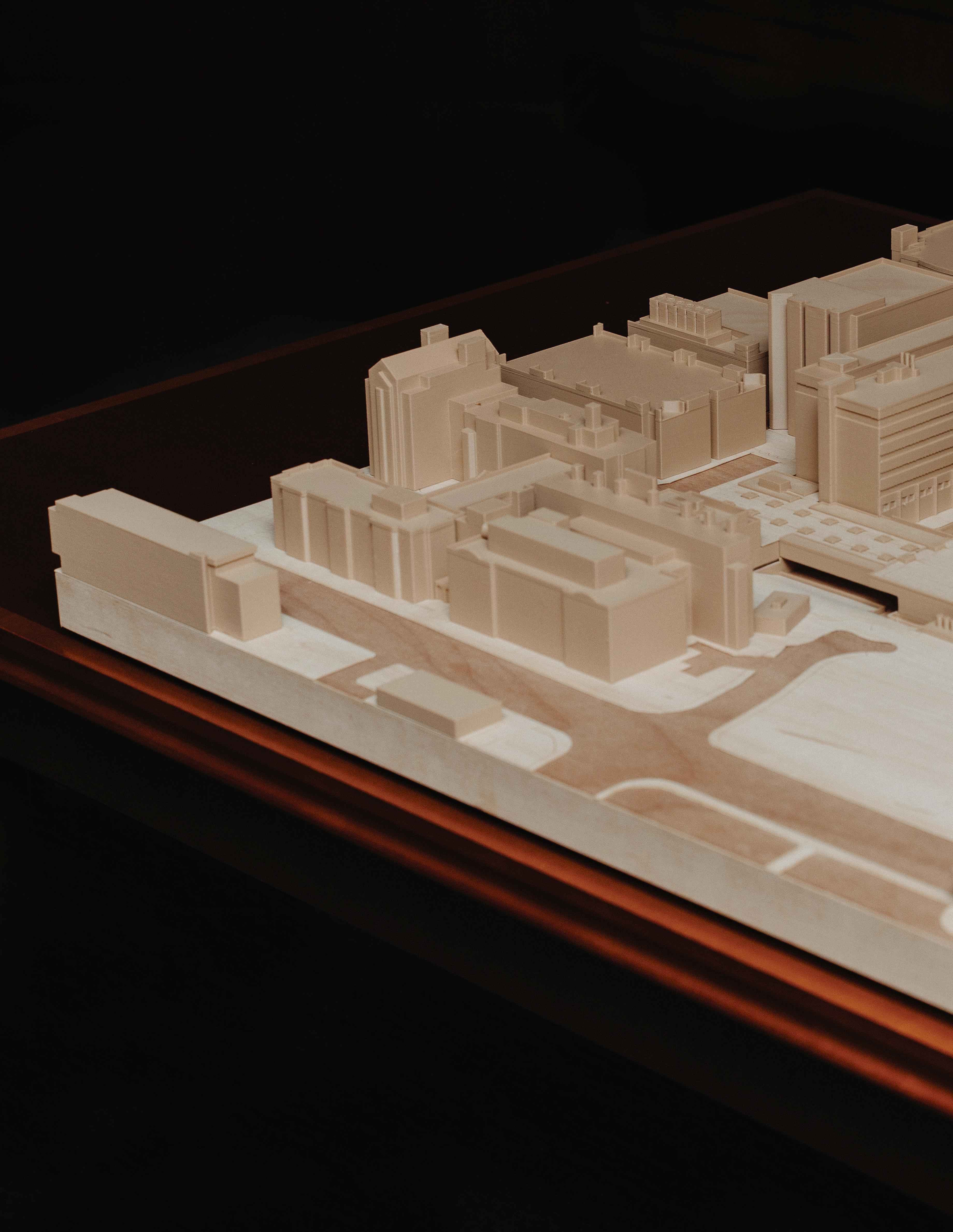

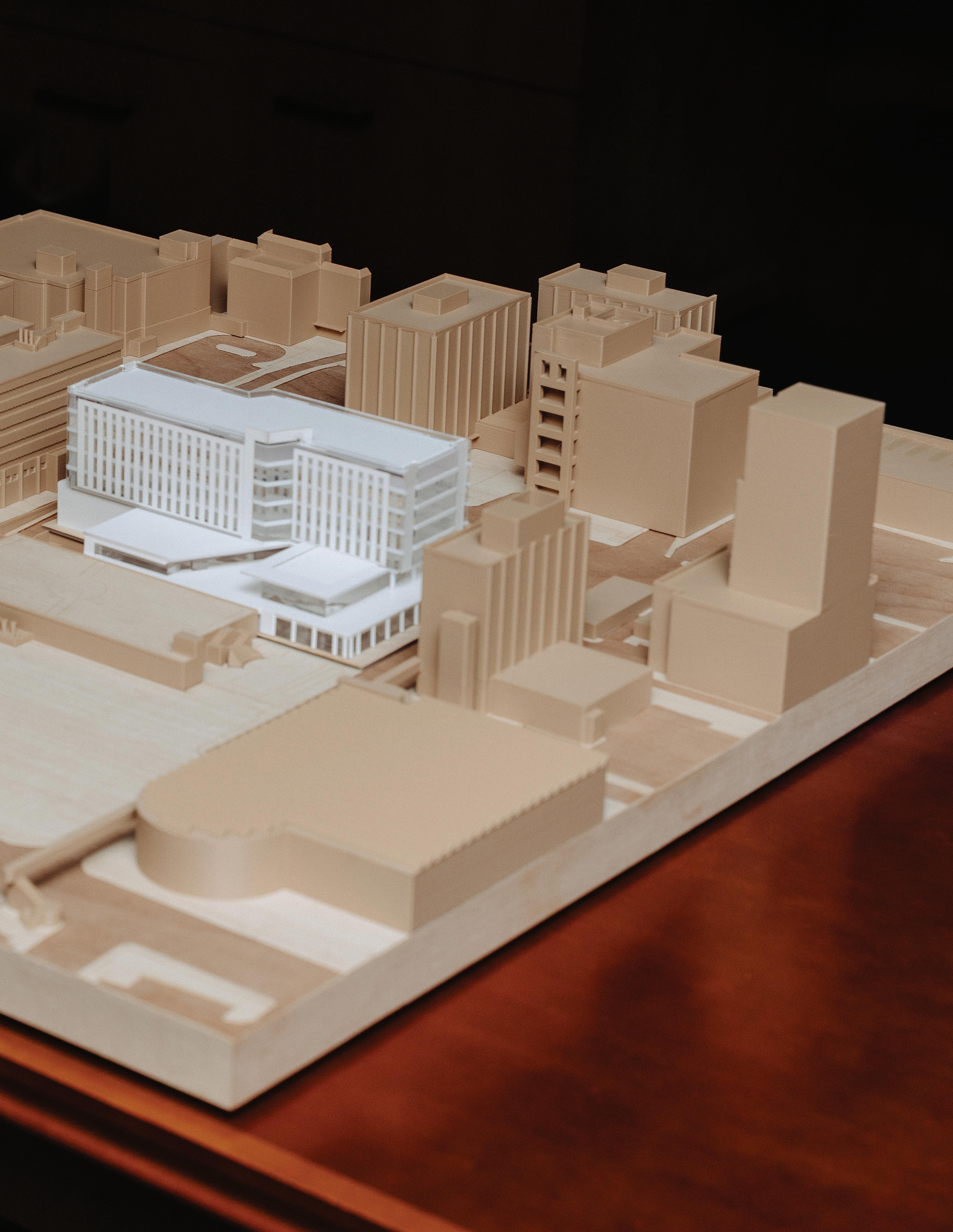

Equally exciting is the possibility of a new interdisciplinary building for the College of Medicine. More than bricks and mortar, this facility would symbolize our commitment to collaboration and innovation. Imagine a space where physicians, scientists, nurses, pharmacists, and other health professionals learn and work side by side, advancing solutions to the most pressing health challenges of our time. Such a building would enhance our educational environment and accelerate discoveries that improve lives across our state.

The future of health care in Tennessee depends on our ability to adapt and innovate. With new leadership and the promise of expanded facilities, we will be even better equipped to confront chronic disease, address health disparities, and train physicians who serve with both skill and humanity. Our partnerships with hospitals, clinics, and communities will ensure that every Tennessean benefits from our work.

The horizon is bright. Together, we will honor our legacy while embracing innovation, ensuring that Tennesseans today and tomorrow have access to the very best in medical education, research, and care.

With gratitude and anticipation,

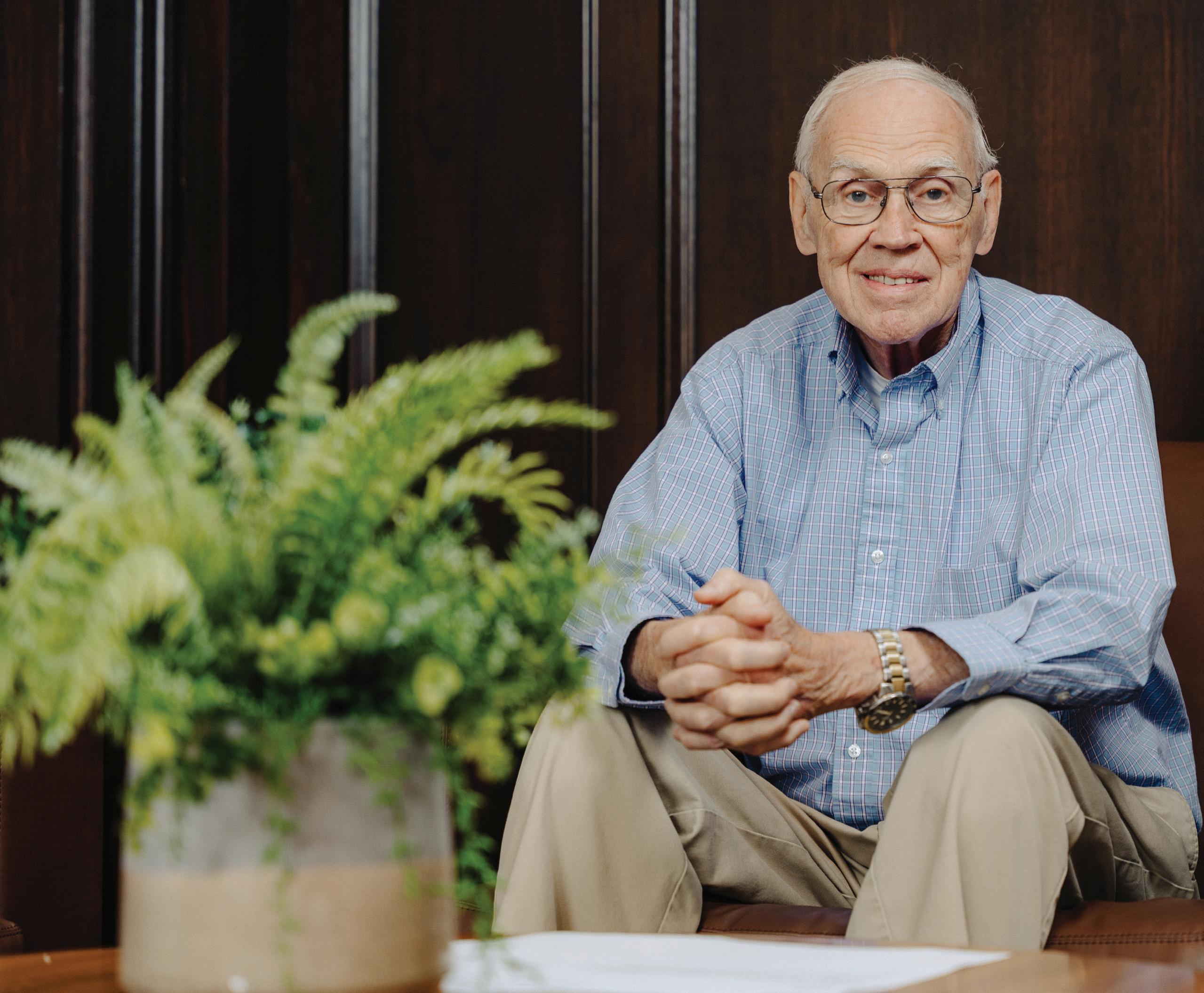

Peter Buckley, MD Chancellor of the University of Tennessee Health Science Center

The First 90 Days and Beyond

Education = Prevention A Legacy of the Heart

Leading the Fight One College of Medicine RESEARCH AND INNOVATION Jaw in a Day

Chancellor

Peter Buckley, MD

Executive Dean of the College of Medicine

Michael Hocker, MD, MHS

Dean, College of Medicine – Chattanooga

James Haynes, MD, MBA, FAAFP

Dean, College of Medicine – Knoxville

Robert Craft, MD

Associate Dean of Clinical Affairs and Graduate Medical Education – Nashville

A. Brian Wilcox, Jr., MD

Vice Chancellor for Advancement

Brigitte Grant, MBA

Assistant Vice Chancellor for Alumni and Constituent Engagement

Chandra Tuggle

Executive Director of Development College of Medicine

Kelly Davis

Editors

Chris Green

Peggy Reisser, MASC

Writers

Lee Ferguson

Chris Green

Aly Lawson

Aimee Chazal McMillin

Haley Overcast

Peggy Reisser

Designers

Adam Gaines

Shunjie (Jason) Zhang

Photographer

Caleb Jia

On The Cover: College of Medicine

researchers are using innovative technology to explore ways to combat certain deadly brain infections. (Page 30)

All qualified applicants will receive equal consideration for employment and admissions without regard to race, color, religion, sex, marital status, parental status, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, disability, age, genetic information, veteran status, or any other characteristic protected by federal or state law.

Eligibility and other terms and conditions of employment benefits at The University of Tennessee are governed by laws and regulations of the State of Tennessee, and this non-discrimination statement is intended to be consistent with those laws and regulations.

In accordance with the requirements of Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, The University of Tennessee affirmatively states that it does not discriminate on the basis of race, sex, or disability in its education programs and activities, and this policy extends to employment by the University.

Inquiries and charges of violation of Title VI (race, color, national origin), Title IX (sex), Section 504 (disability), ADA (disability), Age Discrimination in Employment Act (age), sexual orientation, or veteran status should be directed to the Office of Compliance, 920 Madison Avenue, Suite 825, Memphis, Tennessee 38163, telephone 901.448.7382 (V/ TTY available). Requests for accommodation of a disability should be directed to the ADA Coordinator at the Office of Compliance. 70-700302(001-260671)

‘Our

Is Really

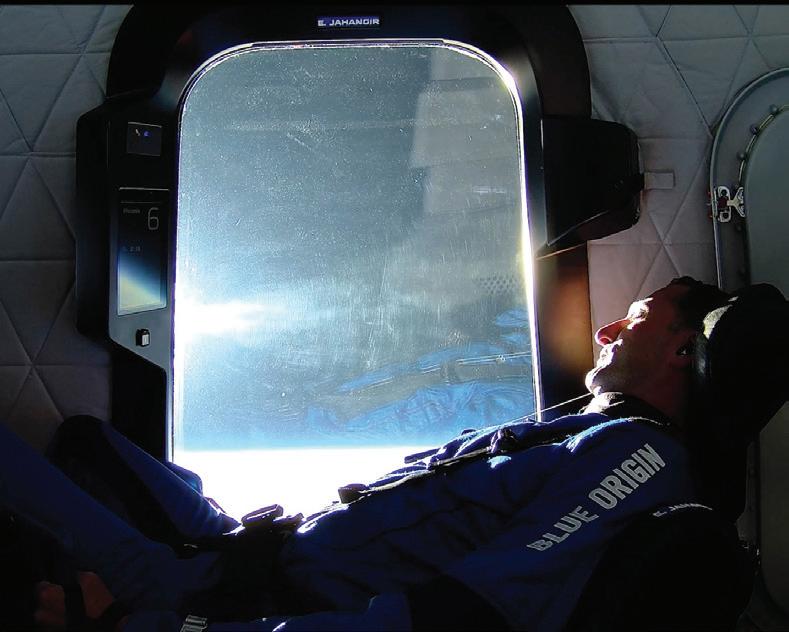

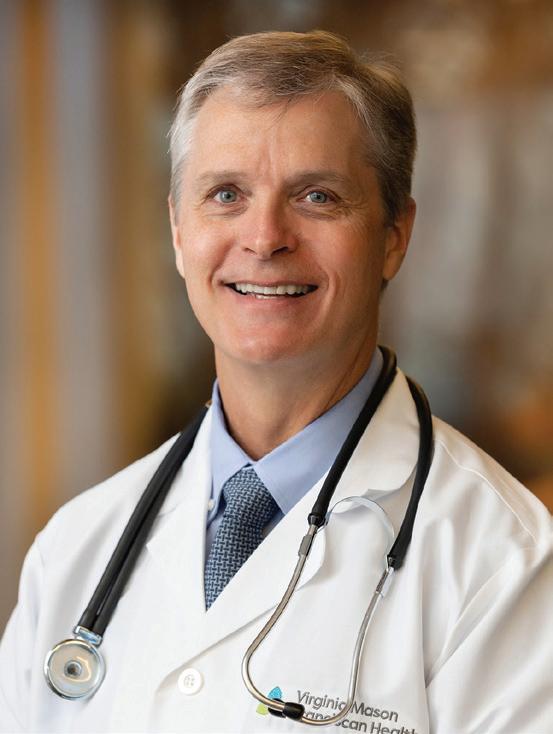

Michael Hocker, MD, assumed the role of executive dean of the College of Medicine in July 2025. As he completed his first 90 days, he reflected on his time at UT Health Science Center and shared his exciting vision for the college as it trains the state’s future physician workforce, cares for the people across Tennessee, and researches the cures of the future.

AQYou’ve been here roughly three months. What has struck you the most about the College of Medicine?

The incredible quality of our students, our staff, our faculty, and the impact they’re having, not in just one region, but throughout the state. It’s incredible to hear the alumni talk about the experience they’ve had here, but I also get to see firsthand what the faculty are doing. And I think the thing that I’m really excited about is our why is really strong. And as I look at how our vision of Thriving Communities. Healthy Tennesseans really resonates with our people. Whether I’m here in Memphis, Chattanooga, Knoxville, Nashville, Jackson, East Tennessee, everyone has the same vision and mission, and we’re all driving toward that.

QWhat drew you to UT Health Science Center?

AI wanted to come here because it’s a wellestablished medical school with a long history of excellence, and the opportunity to lead that with a statewide presence was really important for me, not just personally, but professionally. And to know that medicine can have an impact, not just at the hospital or the region you’re in, but also within the state, where the health indices are not what they should be. I think at the core of what I do as an emergency physician is improving health and access to care. And again, I think that’s where academic medicine is strong here at UT Health Sciences, and it’s strong throughout the state. It’s not just in one hospital or one region.

“When

I look at the students who are entering our medical school, they would be competitive at any medical school in the country.”

–

Executive Dean Michael Hocker, MD

QIs there anything that has surprised you?

AI wouldn’t say surprised. I would say that the complexity of what we’re doing is a challenge, but it’s also an opportunity. Dr. Buckley and the team really did a good job of making sure I understood where the challenges and opportunities were. One thing that I’m delighted to hear moving forward was discussed at the time I was getting recruited. There was discussion about a new College of Medicine Interdisciplinary Building, but I wasn’t sure if that was a pipe dream or really could become reality, knowing the size and scope of that project. I’m not surprised, but I’m just thankful that the leadership team here, from the president through the chancellor and all the vice chancellors, really have rallied around the need for a new College of Medicine building, which I think is really going to have, not just a short-term, but a long-term impact on how we grow medicine and move medicine forward in this state through class size expansion, both in our MD program, PA program, and the interdisciplinary work we’ll be able to do in the building.

AQYou mentioned challenges and opportunities. We just talked about operating a College of Medicine across an entire state. What else would you mention?

I would say the challenges of medicine right now, with the landscape, both at the state and federal level, and the uncertainty of so many things in medicine. I look at this as a great opportunity as a leader. One of my philosophies is to adapt, improvise, and overcome. We are leaders in our state, and as the federal government and state shift, we as leaders have to be adaptable and have to lead our people through that. The people who are going to come out on the other side of that stronger are organizations like us that work together as a UT System, that have a bigger mission, and that have really strong leaders who aren’t afraid to look at innovative ways to change education, to change clinical practice, and to adapt to ever-changing research needs. And so, I really look at that as an opportunity.

AQWhat would you want people to know about the proposed new College of Medicine Interdisciplinary Building?

It’s not just a building. This really represents a history of medicine that started in 1911 (when the university was founded) and has endured so many changes throughout the decades. This will be a home, where we train the next generation of leaders in medicine. When I say home, I don’t know what we’ll look like in four or five years, as we expand our regional sites, which we’re going to need to do, and we need to grow our class size. This new building will allow interprofessional education. This new building will allow class expansion, which is much needed. By 2035, there’s predicted to be a shortage of 6,000 physicians in Tennessee. As Tennessee’s statewide public medical school, the state needs us to make sure that we are filling that pipeline of future physicians for the state of Tennessee.

If we increase the class size, we also need those students to have opportunities locally and regionally and within the state. We will continue to push residency expansion, not just in urban areas, but also rural opportunities. And so, equally as important is increasing the number of residents or on-the-job training. But one will help drive the other.

AQIs there anything else you’d like to share?

In the first 90 days, I’ve been to every part of this state. Everybody’s been welcoming. Everyone is passionate about our mission of training the next generation of health care leaders, taking care of patients and providing high-quality clinical care, and conducting life-changing discoveries and research. And we have people across the state doing that. Everyone is passionate about our mission of commitment and dedication and service that we provide in each one of our communities.

The other thing I would say is about the students coming into our medical school class. When I look at the students who are entering our medical school, they would be competitive at any medical school in the country. That’s a good sign for us, and when I look at the other metrics of success for our students and residents, all the quality indicators are some of the top in the country.

Our medical school is recruiting good, really wellqualified candidates. And the product that comes out, they’re well-trained; they’re viewed as some of the best students, and then ultimately some of the best residents, and they can get jobs anywhere. We need to make sure that that pipeline continues to get full. I’d say one of the things that I want to bring to the college is, we’re going to continue to do what we do well and continue to be innovative in our pipeline programs, our early admission programs, our three-plus programs, where we work to get students and residents through programs and out into the workforce in an expedited, but still high-quality fashion, with a focus on filling the need in Tennessee.

By Chris Green

“There’s going to be a need for continual improvements in our space as we continue to strive to put forward technology and educational experiences for all our learners.”

– Jarrod Young

When the Center for Healthcare Improvement and Patient Simulation (CHIPS) opened in 2018, it transformed how the University of Tennessee Health Science Center prepared students for clinical care. With a recent round of major technology upgrades, CHIPS is again redefining what is possible, making high-quality simulation training more accessible, flexible, and forward-looking than ever.

Over the past year and a half, CHIPS has undergone a major upgrade to its audio-visual systems, a transformation that not only enhanced the quality of simulation recordings but also expanded the center’s reach far beyond the Memphis campus.

“We began an assessment to look at upskilling our audio-visual equipment,” says Jarrod Young, director of Operations, Technology, and Business Development at CHIPS. “This technology helps us be able to support medical education by capturing simulation activities, whether it’s manikin scenarios or encounters with standardized patients.”

These recordings are critical for both assessment and self-reflection. Students can review their performances to identify areas for improvement, and instructors can evaluate clinical competencies with precision. “It allows us to have a one-stop shop, basically, for all learners to come through, pull up their account, and either see the evaluations or self-assess their performance,” Young says. But the upgrade wasn’t just about sharper cameras and clearer audio. It marked a strategic shift from a fixed, on-site system to a cloud-based model that dramatically increases flexibility, scalability, and longevity.

“The new upgrade helps with the volume of information we must store, enhanced speed for accessing simulation recordings, and better integration of assessment tools and data metrics for individual students or aggregate performance of groups. The performance of the technology itself is superior in many ways,” says Tara Lemoine, DO, executive director of CHIPS. “All that can fundamentally streamline our faculty’s workload and provide a better experience for students.”

More importantly, Dr. Lemoine says, the technology now allows for simulation-based education in locations outside the Memphis campus. From anywhere with internet access, students can use their handheld devices to record simulations and push the recordings into the cloud for faculty review. “You could be in your house or out of the country, and we could have you log into your phone or another device, remotely activated by us, and do a simulation in real time,” she says.

Developing remote capabilities will be especially valuable for students and instructors across the statewide campuses. “We can capitalize on this technology to incorporate engagement of more programs across the state and create a more robust simulation footprint for learning,” Dr. Lemoine says. “For example, audiology students could participate in interprofessional simulation with students from other colleges or have access to our expertise here at CHIPS for their educational experiences. We can do things in ways never before possible for all our UT Health Science Center students, no matter where they are located.”

Young emphasizes that the upgraded system was retrofitted directly to the center’s needs and represents “the top-of-the-line system that’s available on the market.” The investment, he says, was a testament to senior leadership’s commitment to advancing education.

That commitment is reflected in CHIPS’s standing among peer institutions. In January 2025, Becker’s Hospital Review included CHIPS in its list of “64 simulation and education programs to know.” The introduction to the list reads, “By leveraging state-of-the-art technology and lifelike simulations, these programs drive better patient outcomes, lower health care costs, and improve patient safety. They provide a secure environment where providers can develop expertise through hands-on practice.”

As an accredited simulation program since 2021, CHIPS adheres to foundational principles of simulation education, including the use of best-in-class technology. But staying at the forefront requires more than a one-time upgrade — it demands ongoing support.

“Just like your laptop or your phone, every couple of years technology advances and changes,” Young says. “There’s going to be a need for continual improvements in our space as we continue to strive to put forward technology and educational experiences for all our learners.”

That includes reinvesting in high-functioning equipment like manikins and staying informed about emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence, augmented reality, and virtual reality. “This field is always changing, so we always have to stay on the front end of assessing what we need to invest in for the future of our learners or what is maybe a catchy, flashy new feature that isn’t worth spending money on,” Young says.

Maintaining and servicing specialized equipment also requires financial and operational support. “We rely on all of our equipment to provide simulation education,” Young says. “So, we have to keep warranties, stay educated on how to troubleshoot and put in corrective maintenance, or know who to call to get this equipment back up and running whenever it breaks or needs service.”

Ultimately, the success of the latest technology upgrade was a collaborative endeavor. “It was a multi-departmental effort between CHIPS, executive leadership, and campus IT,” Young says. “Without all those parties together, we wouldn’t have had such a smooth transition and smooth integration of this technology.”

With the new system fully operational, CHIPS is still exploring how to work with programs statewide to fully leverage the upgraded features to expand opportunities. It is clear, though, that this investment has reinforced the center’s standing among the nation’s best, positioning it to continue leading the way in simulation-based medical education.

To learn more about CHIPS and how you can support it, contact Jay Atkinson, director of development, at jatkin22@uthsc.edu.

By Peggy Reisser

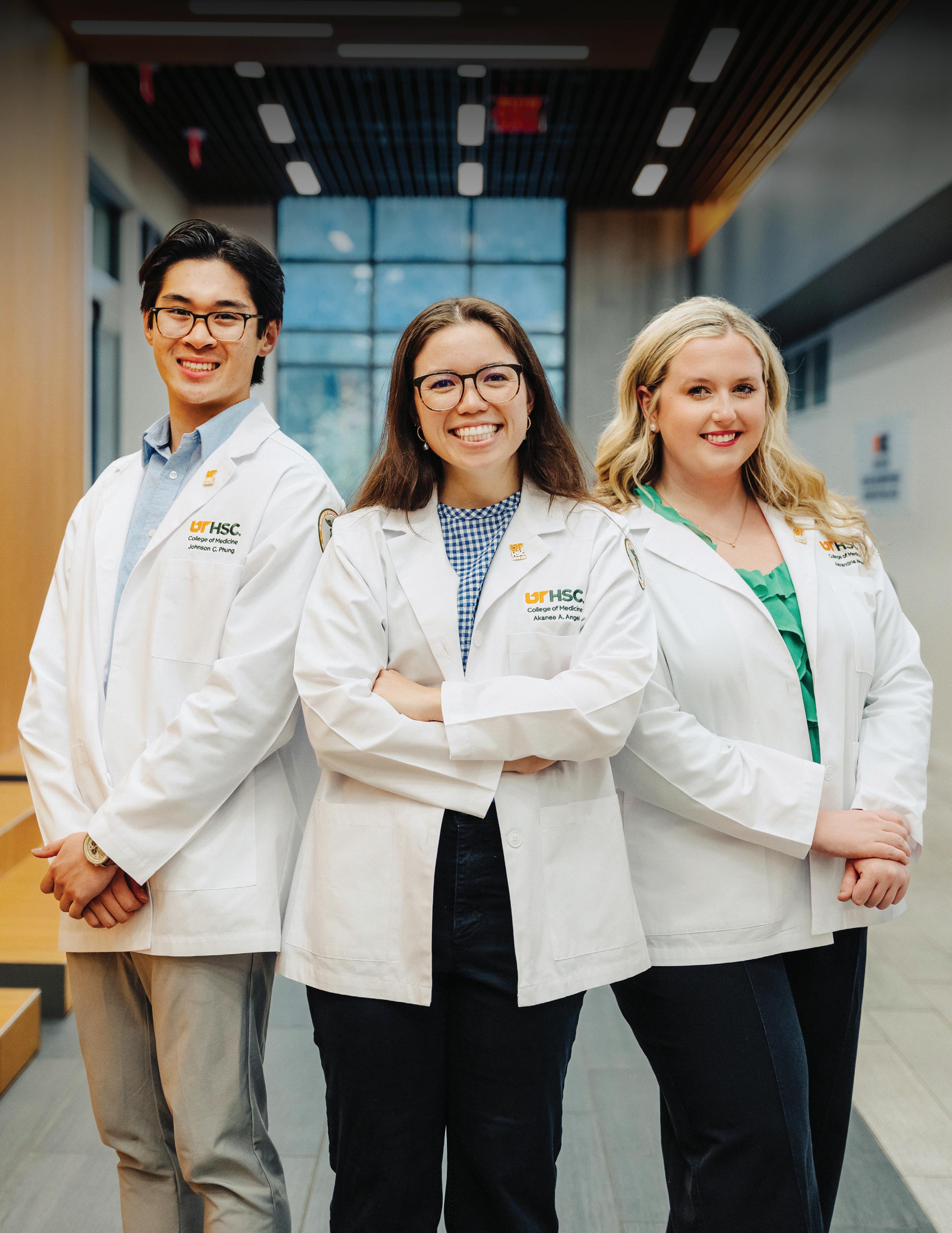

First-year medical student Johnson Phung, 22, aspires to be an internal medicine physician. Akanee Angel, 23, also a first-year medical student, wants to practice family medicine. Both want to stay in Tennessee after they graduate.

Phung and Angel are students in the College of Medicine’s accelerated Three-Year MD Program. Launched in 2021, the program allows highly motivated students committed to practicing in certain fields to complete medical school more rapidly and with reduced cost.

It is available to students who know they want to enter the fields of Family Medicine, Internal Medicine, Medicine-Pediatrics, Pediatrics, Neurology, Pediatric Neurology, and Psychiatry. Participants have a direct pathway to one of these residency programs in the UT Health Science Center system upon graduation from medical school.

“I came into medical school for sure knowing I wanted to do two things,” Angel said. “One was to be a family medicine doctor. I had a whole year of working as a medical assistant in a family medicine clinic, and I knew that it was right for me. I knew that I loved it so much and I couldn’t see myself doing anything else.

“And the other thing I wanted to do was work in Tennessee and stay close to family, stay close to home, and kind of give back to all of these communities that have helped shape me,” Angel, who is from Clarksville, added. “The three-year program, I thought, was a great opportunity to do both of these things and faster than a traditional medical student.”

The accelerated program is special for many reasons, said Catherine Womack, MD, the associate dean of Student Affairs and Admissions at the College of Medicine.

“It is wonderful if students accepted to medical school here know the primary care specialty they are interested in applying to, because they are able to save a year of medical school tuition,” she said. “We need more practicing physicians, as we have a physician shortage, which will only continue to worsen as our population ages. Graduating our students early helps UT Health Science Center increase the number of graduates, helps the student with their debt, and helps our residency programs match excellent students who they know well, as they have mentored and taught them over the three-year program.”

Phung, who is from Lebanon, Tennessee, and Angel graduated from Belmont University and are a couple. “We met during undergrad and are now pursuing our dreams of medicine together at UT Health Science Center,” he said.

In addition to being certain about his future goals, Phung had specific ideas about the institution that would help him achieve them.

“When I was applying to schools, I wanted to make sure I applied to a school that was very collaborative,” he said. “I toured UT Health Science Center twice upon getting accepted and just the environment and the collaboration between the students was probably my favorite thing. Everyone just seemed so ready to support each other instead of competing against one another.

“And then, I also know that I have career goals of staying in Tennessee and practicing in Tennessee,” he said. “I consider Tennessee to be my home state, so it just made a lot of sense to me to train where I was going to eventually practice. And the

three-year program allows me to. First, it’s shorter, so it’s one less year I’m in school, and that’s a year sooner I could get to see patients. Because there’s a conditional match, I get to pour my efforts into things that I want to pour into instead of trying to fill out an application (for residency) or do something just to make sure my application looks good. I get to be a little more particular with my time and point to things I really care about.”

Students in the three-year curriculum achieve the same program objectives and curricular goals as those in the traditional four-year curriculum. The timeline, however, is condensed.

“Because you know what you’re going to want to do, they’re going to give you fewer optional rotations and less elective time,” Phung said. “So, you lose some of your fourth year, and then you also lose, I think, all your summers. Your summers are cut down from two months to two weeks.”

Accelerated programs are increasing at medical schools across the country, said Tina Mullick, MD, an associate professor and the assistant clinical dean for the Three-Year MD Program at UT Health Science Center.

“In terms of national data, we know that people who are in threeyear programs compared to a traditional four-year cohort are equally successful, have equivalent board pass rates, and they do great as physicians,” she said. “And actually, there’s even some data saying they may even be slightly superior in terms of their higher rates of chief residents, for example, amongst the three-year cohorts compared to the four-year cohorts.”

The program has already produced two graduating classes. It began in Memphis, but has expanded to the college’s campuses in Jackson, Chattanooga, Knoxville, and Nashville.

“Probably the biggest thing that I would say for our students and for applicants about this program at an institutional level is that it’s great because hopefully we’re attracting really highcaliber applicants and hopefully we’re keeping these people on as physicians, for certain through residency, but then keeping them beyond as our faculty and as our fellows and as our community physicians,” Dr. Mullick said.

Alex Wood, 22, is from Lexington, Tennessee, and wants to be a pediatrician and practice in West Tennessee as close to her hometown as possible. “Honestly, there is need in all of West Tennessee,” she said.

“Just growing up here, the communities here have always served me. I’m where I am because of the state of Tennessee, and just the kindness of people in my hometown,” said Wood, a UT Knoxville graduate and HOPE and Volunteer Scholarship recipient.

“And so now, I feel like it’s my turn to serve the people of Tennessee back. I just feel like that’s what I was born to do, be a Volunteer.”

To learn how you can support students in the Accelerated MD Program, contact Cameron Mann, director of development, at c.mann@utfi.org.

Match Day 2025 saw nearly half of the College of Medicine’s graduating class match into residencies in Tennessee. Of those 75 students staying in the state, 54 are remaining at UT Health Science Center for their residencies. The numbers speak volumes as UT Health Science Center works to train Tennessee’s future health care workforce.

“This is what we’ve worked for. We have spent hours and hours in hospitals and classrooms and clinics, and we’ve gotten to a point where we get to do what we want to do—be doctors,” said then-fourth-year medical student and class president Grace Anne Holladay, as she awaited the news of where she would spend the next phase of her training to become an OB-GYN.

Dr. Holladay, who earned her MD degree in May, was one of the 168 students who gathered with family and friends on March 21 at Beale Street Landing overlooking the Mississippi River in downtown Memphis for the College of Medicine’s Match Day celebration. When Dr. Holladay opened her envelope, she was thrilled to learn she would be staying at UT Health Science Center for her OB-GYN residency.

“This is exactly where I want to be,” she said. “I feel really blessed to get to stay here and keep training at the place where I fell in love with OB.”

Match Day is a highly anticipated event where medical students nationwide simultaneously discover where they will train for residency. The moment students open their envelopes is often filled with emotion, excitement, and joy as they take the next step in their medical careers. It is a pivotal milestone for medical students, marking years of perseverance and dedication to the field of medicine.

“I want you to hold something in your heart: that you are all amazing people and you are going to be amazing physicians,” Associate Dean of Student Affairs Catherine Womack, MD, told the students moments before the countdown started.

“The reason you are here is that you care about taking care of others. Wherever you go, you will do great things.”

Similar celebrations took place at the College of Medicine’s campuses in Knoxville and Chattanooga. Fourteen students at the Knoxville campus learned their residency placements at a celebration at the Women’s Basketball Hall of Fame. In Chattanooga, six students gathered with their supporters at The Walden Club to learn where they had matched. After a welcome brunch, Dean James Haynes, MD, addressed the group, encouraging students to reflect on their time in medical school and reminding them to support their colleagues in the next phase of their training.

Of the 168 total students who matched:

• 75 (45%) matched to residencies in Tennessee.

• 54 (32%) stayed at UT Health Science Center for residency.

• 76 (45%) matched to primary care specialties

• 61 (36%) matched to non-primary care specialties.

• 31 (18%) matched to surgical specialties.

• 4 (2%) matched to military residency.

By Allyson Lawson

Medical school is hard enough, but students like Avery Dargie add another challenging layer. In Dargie’s last year, the University of Tennessee Health Science Center student leadership funnel led her to Medical Student Executive Council (MSEC) president.

“MSEC acts like an umbrella,” she says, “with numerous committees falling under it that allow for leaders to act as a conduit between the student body and faculty.”

A Memphian from birth, Dargie followed her father’s path to UT Health Science Center. He attended the university and practices emergency medicine locally. After attending Lausanne Collegiate School and

earning her undergraduate degree from the University of Alabama, she returned to Memphis for medical school and is pursuing emergency medicine as well. Her fiancé, Robert “Renn” Eason, also a Class of 2026 medical student, serves as Honor Council president.

“Memphis built us, inspired us, and continues to drive us forward,” she says. “We’re proud to call Memphis our home, and we hope to continue serving this community for many years to come.”

A planning aspect she didn’t anticipate is how she has developed a passion for staying at UT Health Science Center and transitioning into academic medicine to help build the institution.

Students develop within MSEC through four-year elected positions. As president, Dargie serves on the Student Government Association Executive Council, representing the College of Medicine alongside the other five colleges. Dargie’s leadership began as an MSEC representative her first year, then treasurer, vice president, and president.

Class presidents — Ben Finder serves the Class of 2026 — typically hold four-year roles and work closely with MSEC. The council spearheads projects and oversees subcommittees that involve everything from water fountain filters and student resources to security and curriculum changes.

“Once I was elected to MSEC, I was sitting on this committee, voting my peers into these subcommittees, and so that was something I found out on the fly,” she says of her learning curve. “What a great honor and privilege, to get to elect your peers to different subcommittees that really make incredible differences.”

Finder says he basically had no leadership experience before medical school, and the student leaders learn and go through a lot together. While nothing can change the challenge of medical school, he says, it’s much more doable and enjoyable for everyone when you have a network around you. Dargie has worked hard to drive that spirit of community as well as represent the students to administration, he says.

“People like Avery are the ones who step up to the plate and take action when needed.”

Dargie and Finder talk every other day. The executive team shares constant voice notes. Leadership meets monthly; executive leadership weekly. Administration is accessible by text or call. All this while juggling classes and out-of-town rotations.

As medicine evolves, students’ needs change, Dargie says. They strive to address issues with communication and collaboration, so they can accomplish important things efficiently.

“What UT Health Science Center has created is a really good community, where students and faculty come together to make the university the best institution it can be.”

Across student leadership, Dargie has noticed a variety of backgrounds and experiences but a unified purpose.

“Our leaders come up with incredible solutions. I’m fortunate enough to be a sort of bridge for what they want to see happen. We all have different thought processes but always come together to support each other and find solutions.”

The council’s reach spans the breadth of what medical school is, Dargie says.

Curriculum changes go through MSEC subcommittees. Leadership gains student feedback on academic programs and surveys resources students need. For campus life, MSEC worked with the Campus Police Department to increase security before exams. The police now have exam schedules, so students have additional safety during late-night studying.

Student leaders also help fund social events, such as sponsoring the photobooth for the Med Gala. Clubs can request MSEC funding for projects; the council funded holiday baskets for community children through a student organization.

Council members also serve as a positive feedback channel, sharing with administration if an event, effort, or even small thing the dean did was well-liked or successful.

Dargie is busiest as MSEC president during her fourth year, the least demanding academically. This timing by design allows more energy to be dedicated during peak leadership periods. Plus, team members chip in extra when it’s busy.

“I was studying for my second board exam, my VP, who’s a year younger, picked up the slack. It takes a village…We look at the year as a whole and say, let’s do as much as we can to plan for things we know are going to happen.”

The previous president created documentation on what to do and when, and Dargie is building on that for the future. What has become a well-oiled team effort makes balancing academics and governance sustainable, she says.

“Avery is truly one of a kind,” says Alayna Robinson, who also serves on MSEC. “She’s one of the kindest, most genuine individuals I’ve ever met, always the first to lend a hand and support those around her. Avery fosters a culture of positivity, inclusivity, and compassion, and her deep love for this school and its students shines through in everything she does.

“Since M1 year, she has consistently stepped up to volunteer, contribute, and lead. She’s a natural leader, not just because of her dedication and work ethic but also because of her heart. Avery leads by example and sets a standard for what it means to be a servant leader…I genuinely strive to be more like her.”

Physician Called to Educate Public on Disease Prevention

By Peggy Reisser

Here’s how Chinelo Animalu, MD, describes her role as an infectious disease physician:

“We deal with those cases that make everybody else run in the opposite direction,” she says.

An associate professor in the Division of Infectious Diseases in the College of Medicine, Dr. Animalu is the medical director for Infectious Disease and Geographic Medicine for Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare. Her primary clinical practice is at Methodist University Hospital in Memphis.

Born in Nigeria, Dr. Animalu says her early years set the stage for the work that is her passion today.

“Growing up in Nigeria, I was very sickly and had to take medicines for different types of infections,” she recalls. She would see the devastating results, including blindness, disfigurement, and death, from common infections that were left untreated due to a shortage of physicians, a lack of medications, and inadequate health care facilities.

“I used to be traumatized seeing these people,” she says.

“I’m like, ‘Why can’t somebody help them?’ And so, that’s not only what gave me that foundation in medicine, but also the foundation in infectious disease, because what kills us the most in Africa is going to be infections.”

Dr. Animalu earned her medical degree from the University of Nigeria and completed a residency there. She married and immigrated to the United States. An internal medicine residency at St. Joseph Hospital in Chicago followed. She later earned a master’s degree in public health at Tulane University.

“That’s my calling,” she says. “My specialty when I was in Nigeria was actually public health.”

Dr. Animalu moved to Memphis for a fellowship in infectious disease at UT Health Science Center. She joined the College of Medicine faculty as an assistant professor in 2016 and became an associate professor in 2022.

“I do two different kinds of work — my clinical work at Methodist and then my outreach,” she says. The latter role she does as a volunteer because she sees a need that must be met.

Dr. Animalu speaks at meetings, churches, schools, community events, and in the media about the prevention of infectious diseases.

“Based on the experiences back home in Nigeria and in Africa in general, because I’ve been to so many African countries, the problem is still the same — lack of knowledge, people just dying from preventable causes,” she explains.

She is particularly vocal about preventing HIV infections. Memphis has the second-highest rate of new infections in the county, with most new cases among those ages 15 to 24.

“This is devastating, because obviously there’s something we’re doing wrong,” Dr. Animalu says.

“The clinic is for treatment. My own work — what I want us to do is prevention, not treatment.”

Her selfless outreach efforts recently earned her a Health Care Heroes Award from the Memphis Business Journal and the Volunteerism and Community Service Award from the American College of Physicians, Tennessee Chapter.

However, awards are not her goal. Educating the public is.

Earlier this year, she launched a talk show on YouTube, “Medical Class 901 with Dr. Chi,” to do just that. She has educated viewers on antibiotics, HIV, common respiratory infections, and other infectious diseases. The program, also available on Facebook and Instagram, has more than 2,000 followers.

“The whole idea of ‘Medical Class 901’ was just to share information. I have other physicians I invite to come on this show to talk about primary care in whatever their own specialties are,” she says. “Because in Memphis, even though we have major hospitals and health care organizations, the average public, they are lacking so much in terms of health care issues and understanding.”

Dr. Animalu has received numerous awards for her efforts to educate the public about the prevention of infectious diseases.

‘Cancer Care Is All I Ever Wanted to Do,’

By Peggy Reisser

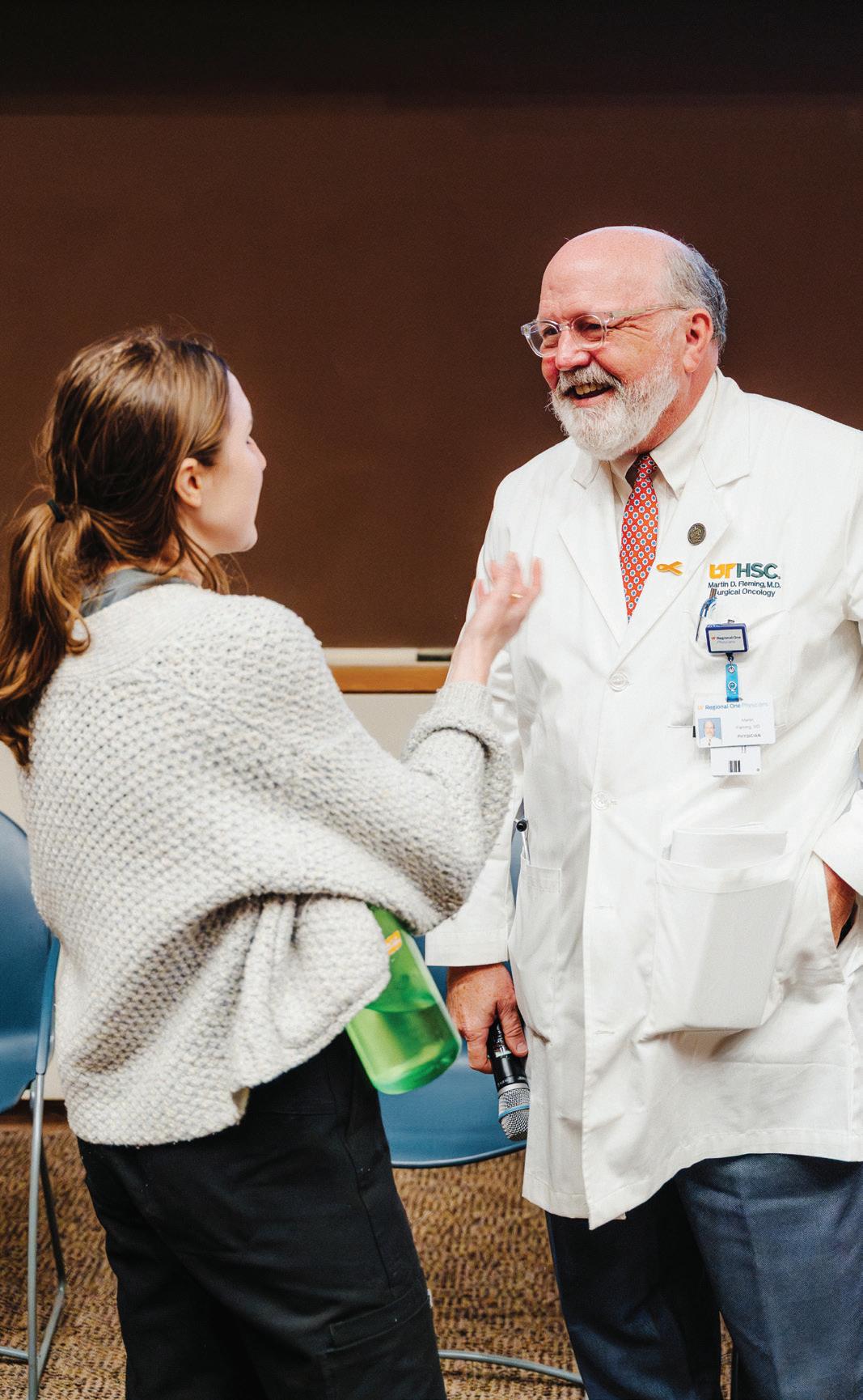

“When we train and teach learners — students, residents, and fellows — at UT Health Science Center, we have an opportunity to keep them here in Tennessee.”

– Dr. Martin Fleming

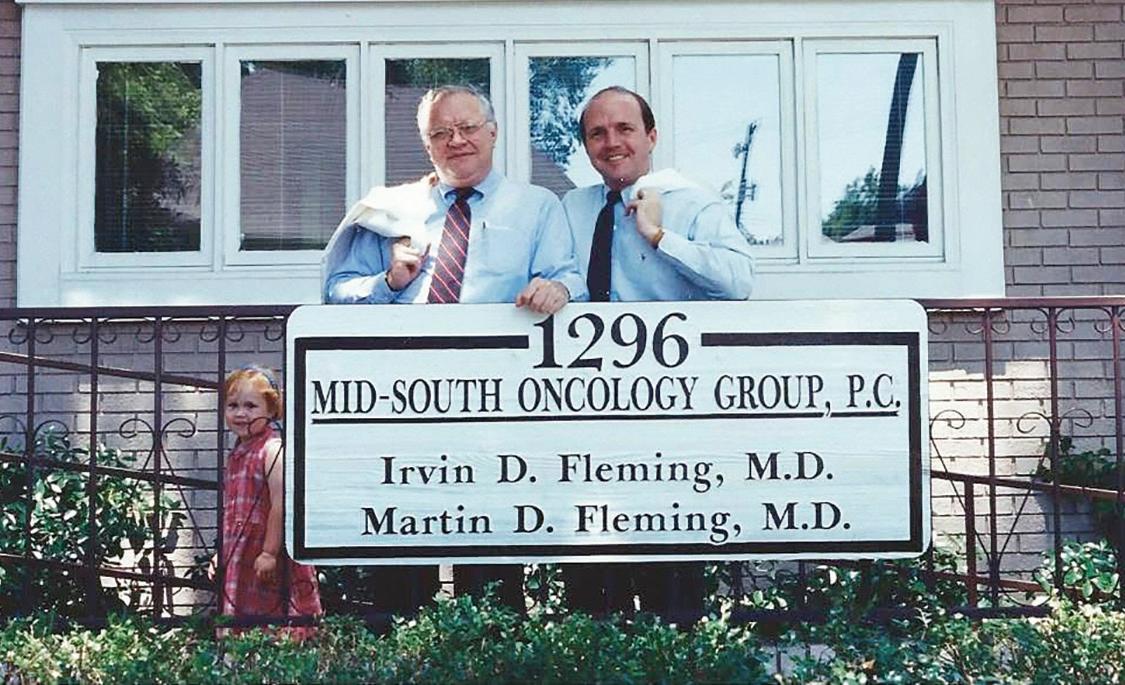

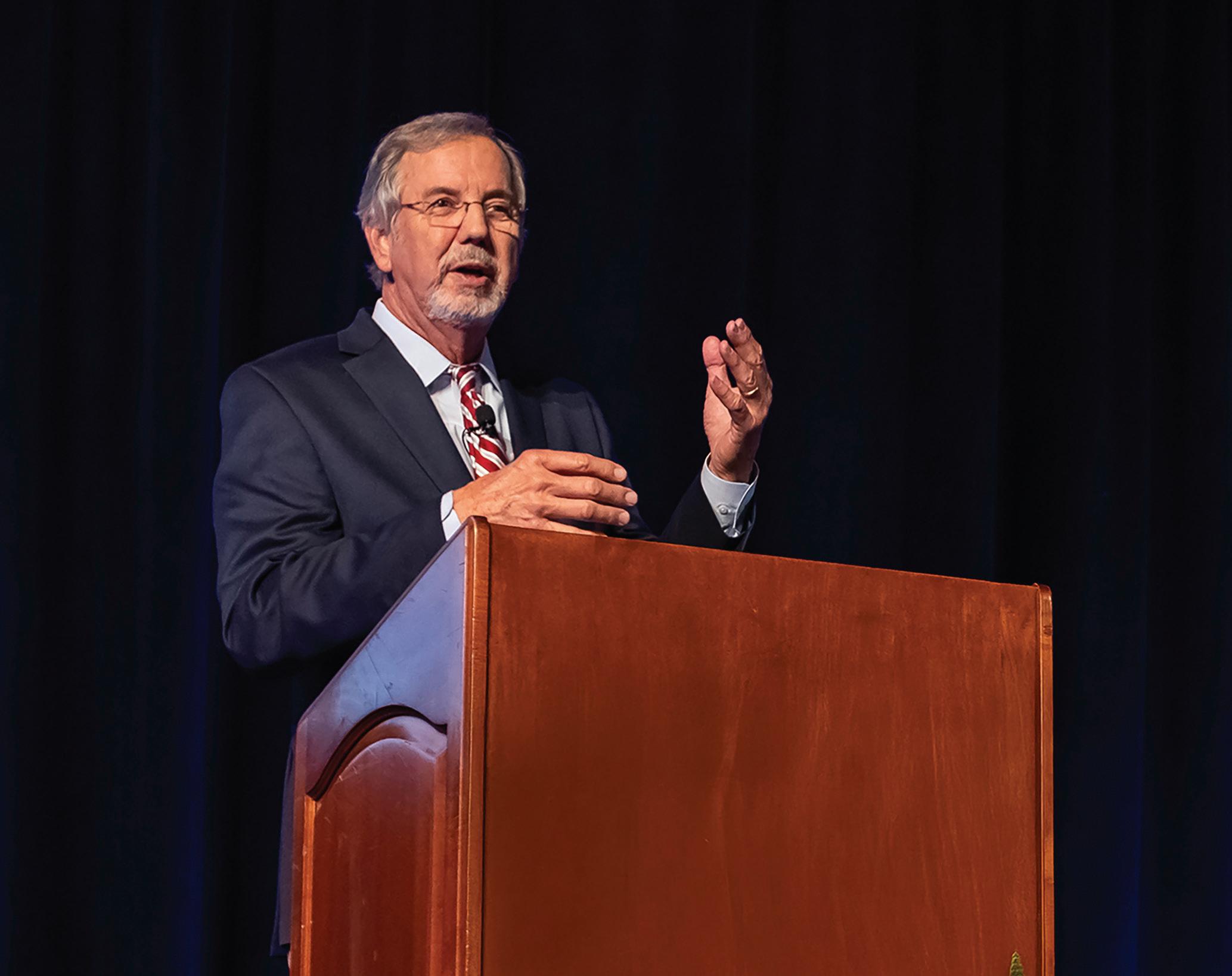

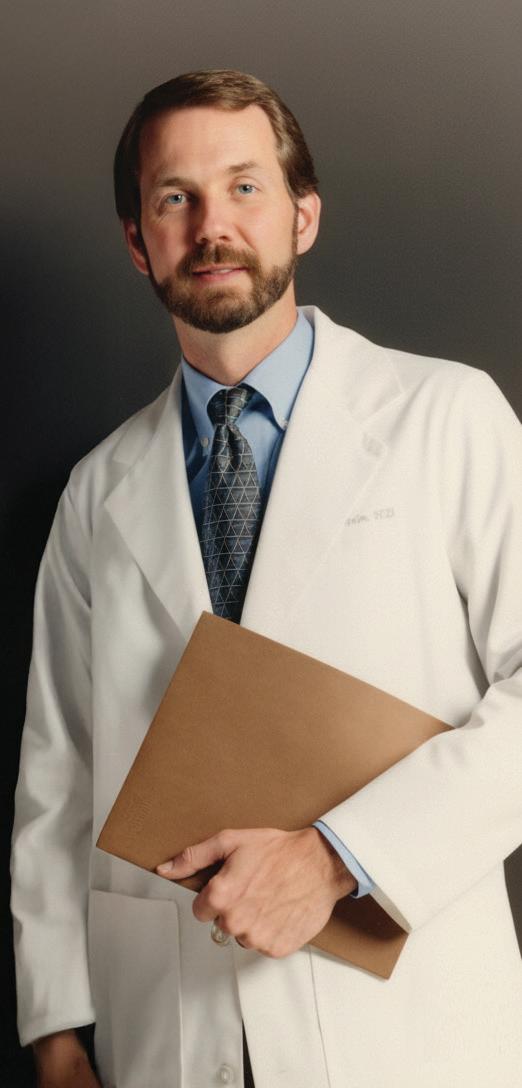

Martin Fleming, MD, chief of the Division of Surgical Oncology in the College of Medicine, remembers going door-to-door in Memphis as early as age 6 or 7 with his mother, a survivor of osteogenic carcinoma, to collect money for the American Cancer Society.

His father, the late Irvin D. Fleming, MD, also a Memphis surgeon and longtime UT Health Science Center professor of surgery, was a pioneer in cancer care and research and spent more than 50 years as a volunteer with the American Cancer Society, serving as its international president in the 1990s.

His son, Andrew Fleming, MD, is one of the chief surgery residents at the College of Medicine and soon to move to Tampa, Florida, to begin a surgical oncology fellowship at Moffitt Cancer Center.

You could say cancer care is a legacy of the heart for all three of these UT Health Science Center College of Medicine alums.

“Cancer care is really all I have ever wanted to do,” Dr. Martin Fleming says. A 1986 graduate of the College of Medicine, he is a nationally recognized authority on the treatment of melanoma, sarcoma, and breast cancer. He completed residency training at the University of Texas Southwestern in Dallas and a surgical oncology fellowship at the Medical College of Virginia. He returned to UT Health Science Center as an adjunct volunteer faculty member in 1993 and joined the faculty full time in 2001.

Since then, Dr. Fleming has made a major contribution in bringing the highest level of cancer care, state-of-the-art research, and treatment options to the people of Memphis and the Mid-South.

He established and leads the Division of Surgical Oncology, which has experienced robust growth and includes nine surgical oncologists. Dr. Fleming is also among the faculty physicians, who under the strong

Dr. Fleming is also dedicated to mentoring future surgeons and surgical oncologists. “Having people who have chosen cancer care as their career path can, and does, transform the care we provide in Memphis and Tennessee.”

leadership of David Shibata, MD, chair of the Department of Surgery, established and operate the Regional One Health (ROH) Cancer Care Program, a collaboration between the university and its clinical partner ROH. Dr. Fleming chairs the program’s Cancer Committee, which links all providers who care for cancer in the hospital.

“It’s really important to have a multidisciplinary approach to each case,” he says. This would include medical oncology, surgical oncology, radiation oncology, and other services.

Earlier this year, the Regional One Health Cancer Care Program earned accreditation as an Academic Comprehensive Cancer Program from the Commission on Cancer, a national organization that recognizes hospital oncology programs that meet the highest standards of patient care.

Accreditation requires many national standards that include a robust tumor board, extensive tracking of screening efforts, and multidisciplinary presentation of cases.

Dr. Fleming, along with oncology program accreditation manager Leslie Stroud, led the initiative.

Sometimes, his teaching even allows him to cross paths with his son in the OR. “I got to operate with him yesterday,” he says proudly.

“One of our main opportunities in our partnership with Regional One Health is impacting the gaps in cancer care across all the populations of Memphis,” he says. “It gives us a unique opportunity to make a difference in the health care in our city.”

Dr. Fleming says accreditation is pivotal to the program. “It demonstrates excellence in cancer care and shows that we offer state-of-the-art, multidisciplinary care for all our patients. It puts us on the map as a place that’s doing it right.”

However, teaching is equally as important as patient care to Dr. Fleming. In his view, the two go hand in hand.

“One of the things I really enjoy is having the opportunity to participate in teaching students, residents, and surgical oncology fellows in the care of cancer patients,” he says.

“One of my first initiatives when I started the Division of Surgical Oncology was to start the process of having a surgical oncology fellowship,” he continues. UT Health Science Center received approval for its fellowship in 2017 and is among 34 accredited surgical oncology fellowships in the U.S. “I thought it important that we have one.”

In addition to instructing surgical oncology fellows and residents on their surgical oncology rotations, Dr. Fleming is the clerkship director, teaching third-year medical students about surgery.

“This is important because our patients deserve the best cancer care we can possibly provide them and to be cared for by physicians who have been trained specifically in that,” he says. “Having people who have chosen cancer care as their career path can, and does, transform the care we provide in Memphis and Tennessee.”

Dr. Fleming is a believer in the statistics that indicate roughly 60% of medical residents stay in the state or region where they trained.

“When we train and teach learners — students, residents, and fellows — at UT Health Science Center, we have an opportunity to keep them here.”

Chelsea Olson, MD, is proof of that. She is from Colorado, went to medical school in Virginia at Virginia Commonwealth University, and trained in general surgery at the University of South Alabama. However, she did her surgical oncology fellowship at UT Health Science Center, and upon completion, recently joined the Division of Surgical Oncology as an assistant professor.

“Dr. Fleming interviewed me, and the whole program was just very welcoming, so I made it my top choice,” she says. “Sometimes when you match into a place, it’s not what you think, but it pretty much lived up to all the expectations I had when I was interviewing, and I was excited to start the fellowship, especially with Dr. Fleming leading it.”

She says Dr. Fleming is careful to ensure everyone involved in a case has a role.

“He’s always making sure that people are involved in his cases and they’re learning something,” Dr. Olson says. “And the environment at UT Health Science Center is all about learning, and I couldn’t help but fall in love with that.”

By Chris Green

When Kenneth Ataga, MD, talks about his work, his focus is always on his patients. He has spent more than two decades caring for people with sickle cell disease and searching for better treatments for the condition that often causes unpredictable pain, threatens organs, and shortens lives.

“I was attracted to medicine because I wanted to help people,” says Dr. Ataga, the Plough Foundation Endowed Chair in Sickle Cell Disease, director of the Center for Sickle Cell Disease, and chief of Hematology at UT Health Science Center. “When I began to understand sickle cell disease and how it affects every aspect of a person’s life, I knew this was where I could make a difference.”

Dr. Ataga grew up in Nigeria, which has the highest number of people living with sickle cell disease in the world. He says he didn’t go to medical school planning to specialize in hematology or sickle cell disease. His original goal was to become a cardiologist.

“When I moved to the U.S. many years ago and started my residency training in Syracuse, New York, I realized that I no longer liked cardiology quite that much,” he says. “But the place where I trained had a very good group of hematologists and oncologists, and it was very easy to be inspired to want to be like them.”

During his training at the University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill, he met the late Eugene Orringer, MD, who became a mentor and helped shape his career. “He was a hematologist who focused on sickle cell disease, and he pretty much changed my life,” Dr. Ataga says. “His enthusiasm was so infectious that I chose to go to Chapel Hill to work with him.”

At Chapel Hill, Dr. Ataga dedicated his clinical and research fellowship, and later his faculty career, to advancing care and understanding of sickle cell disease. He rose to the rank of tenured professor and served as director of the UNC Comprehensive Sickle Cell Program. While his initial interest in Memphis came from a career opportunity for his wife, the city’s large sickle cell population helped him decide to make the move in 2018.

“I knew that if I was going to leave Chapel Hill and go someplace else, it had to be a place where I could take care of patients but also perform the research I do,” he says.

At UT Health Science Center, Dr. Ataga leads a team that provides care for patients across the region at the university’s partner hospitals, including the Regional One Health Diggs-Kraus Sickle Cell Clinic and the Methodist Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center. His focus is on improving patient outcomes, expanding access to care, and developing new treatments.

“Patients with sickle cell disease experience lots of challenges, typically from when they are very young,” he says. “They have unpredictable episodes of pain, which are often referred to as pain crisis, and they experience fatigue. Sickle cell disease can affect pretty much every organ system, so patients are at risk of complications such as stroke, lung problems, kidney problems, and they have a shorter life expectancy than the general population, about 48 years on average. There just aren’t adequate treatments to help prolong their survival to match the general population.”

Over the years, Dr. Ataga has become an international leader in sickle cell research and treatment. He served as the lead investigator on the

clinical trial for crizanlizumab, a drug now approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to reduce pain crises in people with sickle cell disease.

“I presented the initial results at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology in front of thousands of people,” he says. “Whenever I read that paper, I’m always pleased that I played a small role in making this drug available for patients, but I’m also reminded that we have a lot more work to do.”

Dr. Ataga’s team continues to be involved in several clinical studies and trials aimed at developing new therapies that can make the disease less severe. While some sickle cell patients can be cured through bone marrow transplant or gene therapy, most do not have access to those options due to the financial burden or health risks. Instead, their conditions are managed with medications to improve their quality of life and hopefully increase life expectancy.

“We do the best that we can. We want to be available as doctors who understand the problems they have and be advocates for these patients as well,” he says. “So, we try and provide medical care to help them live as normal a life as possible. That’s always the goal.”

While he has led successful studies and trials, Dr. Ataga is proudest of his ability to help patients regain stability and independence. He remembers one patient who was struggling through college because of his illness. Thanks in part to medical management by Dr. Ataga and his team, he not only finished college, but he went to medical school and now works as a sickle cell researcher and advocate.

“We often have patients referred to us because they have been experiencing lots of complications from their disease. Then they come see us, we start them on disease modifying therapies, and they get better. They get well enough that they’re able to go to school or go to work sustainably, and that changes their lives.”

After more than two decades as a hematologist, Dr. Ataga says his patients have also taught him a great deal. “It gives you patience,” he says. “Because they have pain as a common manifestation of their disease, and that’s not something you can objectively measure, it helps you to be even more empathetic. You have to believe them.”

Much like Dr. Orringer was to him, Dr. Ataga tries to be a visible mentor for younger faculty as well as students, residents, and fellows who rotate through his clinics and research programs. He often invites students to work with him, and many have served as co-authors on papers. “I think they find it gratifying,” he says. He hopes the next generation of physicians will continue to push the field forward and make improvements for patients.

“What gives me hope are the people who come after us,” he says. “I think about the enthusiasm that they have and the fact that they want to improve on the work that has already been done in the sickle cell space. That’s what give me hope.”

College of Medicine’s Knoxville Campus Embraces New Name in Line

By Chris Green

The College of Medicine – Knoxville has expanded its undergraduate medical education mission in recent years, allowing more students to train there.

For the last several years, the University of Tennessee Health Science Center’s medical campus in Knoxville operated with a name it had outgrown, according to the campus’s dean. On October 1, that changed.

Now officially the College of Medicine – Knoxville, the campus has stepped into a new identity that reflects its expanding role in undergraduate medical education as it grows to meet the needs of the statewide academic system.

The previous name, UT Graduate School of Medicine, reflected a historic focus on graduate medical education (GME), training residents and fellows. But as its undergraduate medical education (UME, training medical students) and research footprint grew, so did the need for a name that matched its evolving mission.

“Although training residents and fellows will always be core to our campus mission, we have significantly expanded our role within the statewide UT Health Science Center system,” says Robert M. Craft, MD, dean of the Knoxville campus. “Training medical students and doing groundbreaking research are increasingly important aspects of our mission. We are clearly now a College of Medicine.”

The College of Medicine – Knoxville, shortened to CoM-Knoxville, joins its counterparts in Memphis, Chattanooga, and Nashville to form the college’s statewide network of medical education. The updated name reinforces Knoxville’s expanded role in education and brings it into alignment with the naming conventions of the College of Medicine – Chattanooga, which was referred to as simply the Chattanooga Unit until approximately 15 to 20 years ago, and the College of Medicine – Nashville. According to Michael Hocker, MD, executive dean for the College of Medicine, who oversees all the college’s campuses, this consistency strengthens the connection between all campuses and aligns them more clearly with UT Health Science Center’s broader mission to serve communities across Tennessee.

The Knoxville campus’s former name dates to the 1990s, when University Health Systems began operating UT Medical Center — where the campus is housed — in concert with the college’s education and research missions. “‘Graduate School of Medicine’ was chosen because GME was the majority of our academic mission at the time. Our campus mission is now much broader,” Dr. Craft says.

The dean credits UT System President Randy Boyd’s “Be One UT” initiative and the leadership of Chancellor Peter Buckley, MD, for helping drive the change. “There was a change in vision by both the president of the university and by the chancellor of the Health Science Center to get the entire university system working together,” Dr. Craft says.

“We

are moving away from functioning in silos and moving toward leveraging each campus’s strength and best practices, growing together, and collaborating in tangible ways.”

That collaboration is already visible in the Knoxville campus’s growing clinical footprint. Grounded by its affiliation with

the 710-bed UT Medical Center and complemented by new partnerships, including one with East Tennessee Children’s Hospital, the campus now has a similar clinical capacity to the partner hospitals adjacent to the Memphis campus: Regional One Health, Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare, Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital, and the Lt. Col. Luke Weathers, Jr. VA Medical Center.

CoM-Knoxville’s UME offerings have also expanded dramatically. Since 2012, students from the College of Medicine have been able to complete their third and fourth years entirely in Knoxville. The campus now hosts around 60 medical students at any given time, alongside 290 residents and fellows. Dr. Craft says that combination is beneficial for both medical students and graduate trainees.

“Integrating medical student training alongside residents and fellows in an academic medical center is optimal,” he says. “There’s a lot to be gained by the students from the residents’ perspectives, and the residents become teachers, which helps them solidify their own knowledge base. We often learn particularly effectively from people who are just up the experience ladder from us, so that’s another advantage from medical students learning with residents.”

Dr. Craft says the Knoxville campus is growing by “leaps and bounds, in every way.” In addition to larger medical student class sizes, CoM-Knoxville has laid the foundation for 25% growth of its GME programs from 2022 to 2027, and it is already halfway toward that goal. This growth, Dr. Craft says, is vital for the state.

According to Executive Dean Hocker, Tennessee needs additional physicians, and the state is projected to have a deficit of 6,000 physicians by 2030. “The College of Medicine and each of its campuses must be integral in ensuring that the state has enough physicians who can provide high-quality care to patients throughout the state,” he says.

The College of Medicine – Chattanooga is also increasing the number of physicians it produces. The campus is on track to expand its resident and fellow cohorts by 20% over three years. With 219 currently training in partnership with clinical partner Erlanger, the campus has already achieved 12% of that growth. Additionally, the number of third- and fourth-year medical students completing all their clinical training in Chattanooga increased this year to 24, up from a historical average of six to 10 annually. A total of more than 100 UT Health Science Center students rotate through the campus each year.

The College of Medicine – Nashville is also experiencing growth. What began with one residency program in partnership with Ascension Saint Thomas roughly 10 years ago, has blossomed with residency and fellowship program growth across multiple specialties, research collaborations, and rural care initiatives. The college is poised for future growth to serve the people of Middle Tennessee.

“With the name change in Knoxville, we’re reinforcing the fact that medical education in Tennessee is a team effort,” Executive Dean Hocker says. “This alignment connects our Knoxville campus even more closely with our colleagues in Memphis, Nashville, and Chattanooga. It opens the door to new opportunities for collaboration and helps us serve our learners and communities with even greater strength.”

By Chris Green

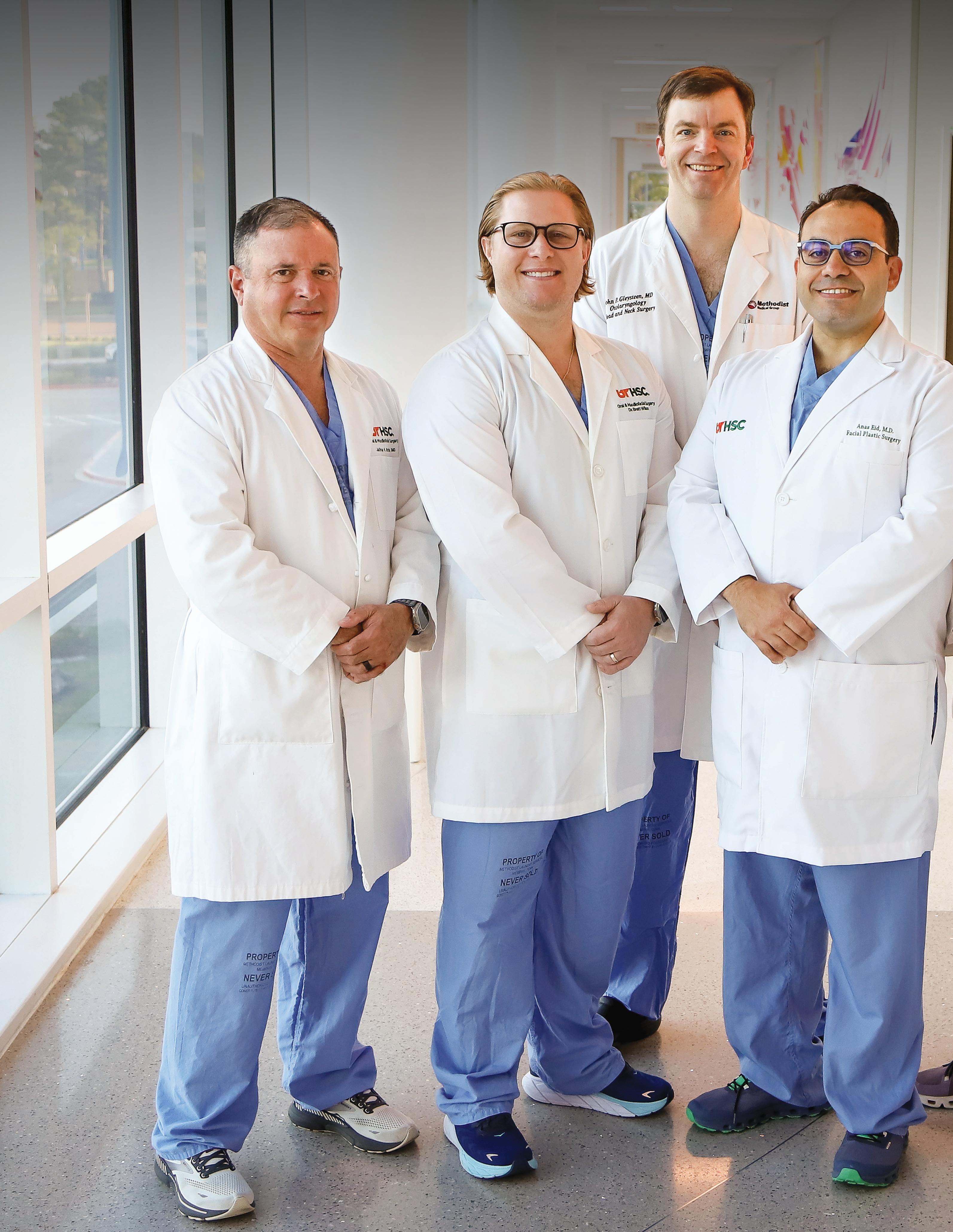

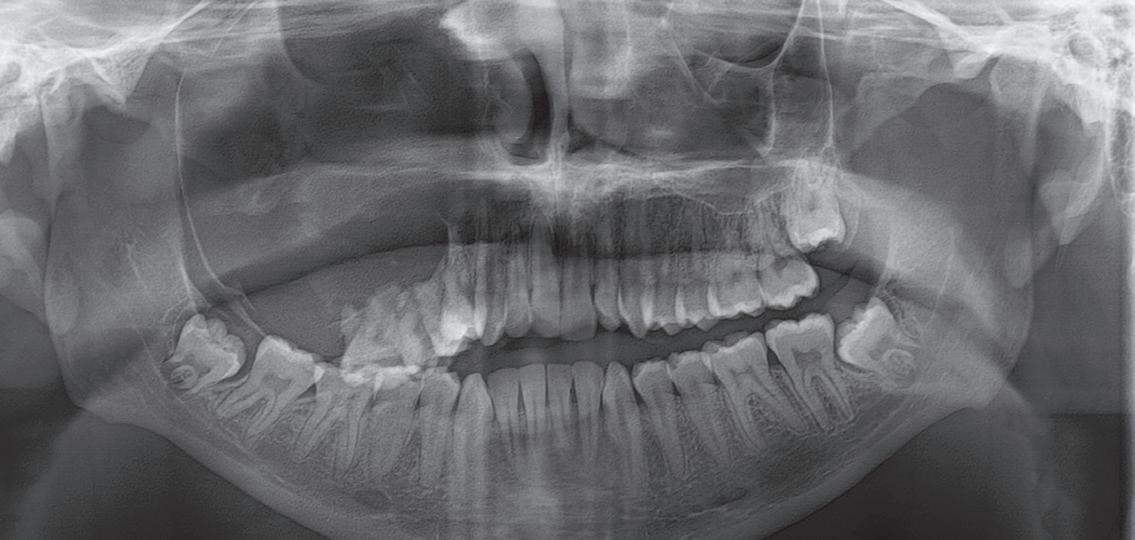

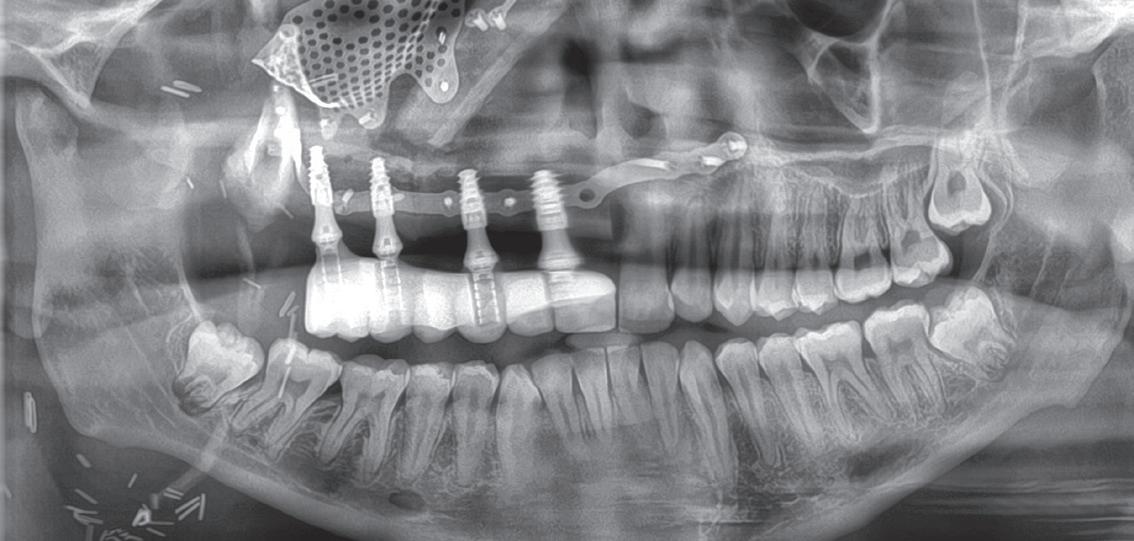

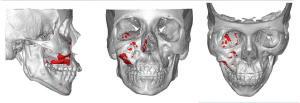

On an April morning in Memphis, James Wynn, then 17, prepared for a surgery that would change his life and make history in Tennessee. Diagnosed with a tumor destroying his jaw and facial bones, James became the first patient in the state and the Mid-South to undergo a groundbreaking “Jaw in a Day” procedure.

In a single operation at Methodist University Hospital, a multidisciplinary team of surgeons from the UT Health Science Center College of Medicine and College of Dentistry removed the tumor, rebuilt James’s facial bones and jaw using his leg bone, and placed custom dental implants and prosthetic teeth. The single-day approach dramatically shortened what would normally take months or years of procedures.

“Traditional methods could take several months, sometimes even years, to complete. In contrast, this procedure enables patients to receive a functional jaw in just one day,” said Anas Eid, MD, chief of facial plastic surgery and leader of the Jaw in a Day team.

For James, who was diagnosed with the tumor a few months earlier, the news that it could all be done in a single day brought relief. His mother, Alysha Wynn, recalled her nervousness before the operation but said her son’s resilience impressed her. “I was surprised by how good he looked, even though he was still kind of swollen,” she said. “I’m just thankful that he actually went through it and came out.”

The operation was the result of years of planning and collaboration across multiple specialties. In addition to Dr. Eid, the team consisted of the Department of Otolaryngology’s Assistant Professor C. Burton Wood, MD, and Associate Professor John Gleysteen, MD, along with the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery’s Chair and Professor Jeffrey Brooks, DMD, and Program Director and Associate Professor Brett Wilson, DDS. Using 3D models, custom hardware, and meticulous coordination, the surgeons united their skills to achieve a life-changing outcome.

“This surgery involves multiple steps from multiple surgeons that essentially build on one another,” Dr. Wilson said. “Each surgeon has to execute their part to set the next surgeon up for success, so the stakes can be high for everyone involved to bring the entire plan to fruition.”

The success of the surgery earned the Jaw in a Day team recognition beyond the operating room. In August, the Memphis Business Journal honored the group at its 2025 Health Care Heroes Awards, where four of the five winners and more than half of the 25 finalists were affiliated with UT Health Science Center.

Front row from

Brooks,

professor and chair of the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; Brett Wilson, DDS, associate professor and program director for Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery; Anas Eid, MD, chief of Facial Plastic Surgery and lead surgeon; C. Burton Wood, MD, assistant professor of head and neck surgical oncology in the Department of Otolaryngology. In back, John Gleestyn, MD, associate professor in the Department of Otolaryngology. Photo by Natalie Clay

“Receiving the Health Care Innovations Award for our novel singlestage facial reconstruction technique was deeply gratifying,” Dr. Eid said. “It not only recognizes the novelty of our method, but it also underscores how a cohesive team of highly talented and specialized surgeons, through precise and orchestrated intervention, can dramatically improve patient outcomes and quality of life.”

The award also underscored how innovation in Memphis is shaping health care across Tennessee and beyond. “Innovations of this caliber are a direct product of the supportive and collaborative environment fostered by institutions like the University of Tennessee Health Science Center,” Dr. Eid said.

Since James’s surgery, the team has completed additional Jaw in a Day cases, proving the procedure’s success and reaffirming Tennessee’s leadership in advanced care. Each new patient benefits from lessons learned in the operating room and from the close partnerships that made the first case possible.

“In the state of Tennessee, this achievement sets a new benchmark for head and neck reconstructive procedures,” Dr. Eid said. “Our institution takes great pride in being a pioneer in this area, contributing significantly to the improvement of health care services in our state.”

For James, the impact was both immediate and long-lasting. He left the hospital within a week and quickly returned to daily life with only small scars as evidence of what he endured. His restored smile is a reminder not only of his own courage, but of what Tennessee’s health care teams can achieve when they work together.

Dr. Eid and Dr. Wilson during surgery (top-left). James’s smile at the completion of surgery (top-right). The “Jaw in a Day” team included surgeons, residents, and a supporting staff of scrub technologists, nurses, clinic staff, and prosthodontists (bottom).

By Lee Ferguson

If clinical trials are the engine that drives new treatments and medical breakthroughs, then Giuseppe Pizzorno, PhD, PharmD, is the master mechanic working under the hood.

At Erlanger Health System in Chattanooga, he has quietly built the complex machinery — research teams, contracts, processes, and support systems — that allows dozens of cutting-edge trials to run without a hitch. Most patients never see this work, and many physicians simply rely on it in the background, but without it, those discoveries would stall before they ever reached the bedside. Now, after years of operating out of the spotlight, Dr. Pizzorno is being recognized for the vital role he plays with a Champions of Health Care Award from the Chattanooga Times Free Press.

Through his visionary leadership, Dr. Pizzorno, chief research officer at Erlanger and associate dean for Research at the UT Health Science Center College of Medicine – Chattanooga, has built a strong collaborative bridge between the two institutions. Under his guidance, Erlanger’s research program has grown into a powerhouse, supporting more than 50 physician-investigators in 11 therapeutic areas. Together, they are enrolling participants in roughly 40 active clinical trials, with another 25 to 30 in follow-up, advancing discoveries that span nearly every corner of modern medicine.

“We’ve created an environment where clinical research can thrive without disrupting clinical care,” Dr. Pizzorno says. “Physicians here don’t have protected research time, so our team supports them every step of the way — coordinators, regulatory staff, nurses — so that they can participate in high-impact research while continuing to care for patients.”

That model is working. Research conducted at Erlanger, in partnership with UT Health Science Center, has led to faculty publications in the New England Journal of Medicine, the Lancet, and other top-tier journals. Clinical trials span nearly every specialty, from AI-assisted colonoscopies in gastroenterology to advanced cardiac devices and phase 1 urology drug trials. “For some patients, participating in a clinical trial means getting the best care they’ve ever had,” he says. “That’s the kind of impact that motivates me every day.”

Dr. Pizzorno describes his own role in the process as “a little bit like Match.com,” pairing the right investigator with the right clinical trial and ensuring that each study is financially sustainable, scientifically rigorous, and operationally feasible.

“The clinical trial business is a $40 billion industry, and it’s going to double in the next five years,” he says. “We have to treat it like the serious business it is. That means negotiating contracts line by line, down to every needle and Band-Aid, and making sure our teams are delivering clean, usable data that sponsors can count on.”

One of his biggest innovations has been workforce development. Facing challenges recruiting experienced research coordinators, Dr. Pizzorno launched a pipeline program for local college graduates taking gap years before medical or graduate school. These young professionals receive foundational training in clinical research and contribute meaningfully to trial coordination, gaining critical experience and often, strong letters of recommendation, as they prepare for careers in medicine.

“We’ve had students from UT Chattanooga, Lee University, Kenyon College, and even Baylor University join our team,” he says. “Now we’re seeing some of them go off to medical school, and others are staying in clinical research. It’s become a real pipeline.”

Dr. Pizzorno also emphasized the unique advantages Chattanooga offers for clinical research: a high-volume, a varied patient population, engaged physician faculty, and a geographic position that bridges urban and rural communities, many of whom benefit from access to cutting-edge trials.

Jessica Snowden, MD, vice chancellor for Research at UT Health Science Center, also points to Chattanooga as a powerful example of why access to clinical trials matters statewide. “Clinical trials aren’t just about advancing science. They’re about ensuring that every patient has access to the very best care,” she says. “If we only reach urban centers, we miss the chance to serve the people who need these treatments most. Dr. Pizzorno’s work highlights the best of UT Health Science Center’s mission of bringing ’Healthy Tennesseans. Thriving Communities.’ to all corners of our state through cutting-edge science and exemplary care.”

While honored by the Champions of Health Care Award, Dr. Pizzorno remains focused on what’s next: advancing early-phase clinical trials, expanding academic collaborations, and giving every trainee, coordinator, and physician the chance to contribute to something meaningful.

“When you give people opportunities,” he says, “that’s when they shine.”

“For some patients, participating in a clinical trial means getting the best care they’ve ever had. That’s the kind of impact that motivates me every day.”

– Dr. Giuseppe Pizzorno

By Lee Ferguson

Inside a lab at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, a transparent chip no bigger than a stick of gum could be changing the way scientists study the human brain and how they fight some of the world’s most dangerous viruses.

Colleen Jonsson, PhD (right), Harriet S. Van Vleet Chair of Excellence in Virology and director of UT Health Science Center’s Regional Biocontainment Laboratory and Institute for the Study of Host Pathogen Systems, is leading a project that pushes the boundaries of biomedical research.. Together with her graduate student, Walter Reichard, she is using a human brain-on-a-chip to explore how deadly brain infections take hold and how to stop them.

Venezuelan and Eastern equine encephalitis viruses (VEEV and EEEV) are rare but devastating infections that can cause fatal brain inflammation, particularly in children and older adults. “They infect children and older adults and cause lethal disease,” Dr. Jonsson said simply. “The brain is extremely well protected, and these viruses can still find a way in.”

To understand and combat them, scientists have traditionally relied on mouse models. But Dr. Jonsson’s lab is testing a revolutionary alternative — a miniature, three-dimensional system that replicates the function of the human brain. Known as a brain-on-a-chip, the technology represents what the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) have been calling the future of non-animal research, or “NAMs,” new-approach methods.

“This is novel technology to advance biological and therapeutic discovery,” Dr. Jonsson said. “The human brain chip allows us to do testing in humans. Whereas otherwise, we’re limited to doing our preclinical research with mice.”

Reichard, who is completing his PhD under Dr. Jonsson, has spent months troubleshooting and optimizing the system to make sure it behaves as similarly to a brain as possible. The device consists of two microscopic channels separated by a porous membrane. “You have these pods on a rack that go into an instrument called a ZOE CM2,” he explained. “That system controls the flow rate of media — basically, the blood — through the chip.”

One channel contains human vascular cells, the kind that line blood vessels. The other holds neurons, astrocytes, microglia, and pericytes — key cell types that make up the brain’s structure and immune defenses. Fluid flows continuously through the system, mimicking blood circulation and creating a tight barrier between the two chambers. That barrier, just like the real blood-brain barrier, carefully filters what can and cannot enter the brain.

“The virus we study is able to sneak through this barrier and get into the brain,” Dr. Jonsson said. “The chip recapitulates this tight barrier between our brain and our body. It’s a 3D representation of the brain.”

The human cells used in the model are de-identified and commercially obtained from deceased adult donors. In Jonsson’s lab, these living tissues form an intricate, dynamic environment, one that can be infected, treated, and observed under near-realistic conditions.

While the system offers extraordinary promise, Dr. Jonsson is careful not to overstate its capabilities. “We’re at really early stages,” she said. “This is exploratory research to determine the ability of the human brain chip to bridge the gap from mouse to human.”

She doesn’t yet call it superior to animal models, but she believes it could dramatically accelerate translation to human medicine. “I don’t know if we’ll ever get rid of animal models, but having human cells to look at how our drug is working gives us better insight into translation.”

Cost is not the main advantage — Dr. Jonsson admits the technology isn’t cheaper — but the potential precision is. “It gets us right to whether or not the drug could be effective for humans,” she said.

Early tests in the Jonsson lab have been promising. The team has already shown that their antiviral drug candidates — developed in collaboration with Bernd Meibohm, PhD, distinguished professor and associate dean for Research in the UT Health Science Center College of Pharmacy, and Jennifer Golden, PhD, associate director of the Medicinal Chemistry Center at the University of Wisconsin — can protect mice from encephalitic virus infection. Now, they are using the brain-on-a-chip to see whether those same drugs inhibit viral replication in human brain tissue.

“We can see antiviral efficacy in this chip,” Dr. Jonsson said, referring to a recent proof-of-concept experiment using one compound called Badger 49. “This is a really promising series of antivirals that treat encephalitic infections.”

Reichard finds the system just as thrilling from a research standpoint. “I’d be most excited to see how the virus crosses into the brain channel,” he said.

“When we got our first data, we were instantly brainstorming all the things we could do next. There was a lot of excitement when we first started.”

The implications extend well beyond viral encephalitis. “This technology could be used for Alzheimer’s drugs, Parkinson’s, even brain cancer,” Dr. Jonsson said. “The system is being used elsewhere in the country for different applications, but when we started, we were a little ahead of the game.”

For Dr. Jonsson, the success of the project comes down to both innovation and mentorship. “You can have all the ideas and dreams,” she said, “but without the right student, it’s not going to go anywhere. Walter has really been the driver behind the project.”

Though Reichard had never worked with organ-on-a-chip systems before, he was willing to take on the challenge. “I had a lot of cell culture experience but not with this technology,” he said. “It’s been a big learning experience.”

Dr. Jonsson smiled. “I’ve always worked with a lot of different technologies,” she said. “I’m usually an early technology embracer.”

The project “Evaluation of Antiviral Efficacy using a Blood Brain Barrier Model” is being funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

Meet the UT Health Science Center faculty members serving as the new executive co-directors of the Heart Institute at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital: Chief of Pediatric Cardiology Jason Johnson, MD (left), and Chief of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Bret Mettler, MD (right).

“There will be times when we have to make challenging decisions for the institution, for the health system, for the medical school, or for me personally, but I think if we always keep patients at the center, we will always lead to making the right decision.”

– Dr. Bret Mettler

By Chris Green

Long before he became a leader in pediatric cardiac surgery, Bret Mettler, MD, entered medicine through a love of science and discovery. But it was the moments at the bedside, where he saw the difference his care made in the lives of children and their families, that gave his career its true meaning.

“I kind of meandered my way into pediatric cardiac surgery,” Dr. Mettler says. “I fell in love with the technical sophistication, the complexity of the operations, and the range of pathology we see, but as important was being able to make a difference to someone for potentially a whole entire life — not just a few years of life, but 60, 70, 80, 90 years of life.”

That passion for making a lasting impact led Dr. Mettler to Memphis and the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, where he is chief of pediatric cardiac surgery, the Susan and Alan Graf Endowed Chair in Pediatric Heart Surgery, and executive co-director of the Heart Institute at Le Bonheur Children’s Hospital, the university’s primary pediatric partner. In addition to the professional opportunity, what brought him here was a convergence of personal roots, institutional vision, and the promise of growth.

Dr. Mettler came to Memphis from Johns Hopkins Children’s Center in Baltimore, Maryland, where he served as director of pediatric cardiac surgery and co-director of its heart center. Before that, he was director of cardiac transplantation and mechanical circulatory support at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville.

Because his move to Johns Hopkins happened during the COVID-19 pandemic, his family stayed in Tennessee and deepened their ties to the Volunteer State. “My family got used to being in Tennessee, and we went back and forth to see each other,” he says.

With a southern wife and two daughters who have only ever been Tennesseans, the chance to return felt like coming home. “We love being back in the South. We like the warmth, the openness, the inquisitiveness. I prefer to be back down in an environment with that southern hospitality, which is what we’ve known our whole lives and our daughters have grown up in,” he says.

But the move was about more than geography. Dr. Mettler was drawn to the unique opportunities at UT Health Science Center and Le Bonheur. Under the leadership of the previous executive co-directors — Chief of Pediatric Cardiac Surgery Christopher Knott-Craig, MD, and Chief of Pediatric Cardiology Jeffrey Towbin, MD — the Heart Institute advanced into a top 10 program. Additionally, U.S. News & World Report has named Le Bonheur one of the nation’s “Best Children’s Hospitals” for 15 consecutive years, and the hospital recently completed a $95.4 million expansion, much of which is dedicated to caring for children with congenital cardiac disease.

“There was a rich history of congenital cardiac care here, started by visionary leaders, and an administration who had desires to not only maintain but to grow a pediatric heart institute to levels which hadn’t been realized before,” he says.

For Dr. Mettler, this environment created the ideal conditions for both clinical excellence and innovation. “It’s an exciting place for someone like me, who wants to provide excellent clinical care and research to work our ideas and foster the next generation of ideas.”

That work is supported by UT Health Science Center and the Methodist Le Bonheur Healthcare system, which together foster a collaborative environment where new programs and research initiatives can thrive.

For Dr. Mettler, being part of the academic medical setting at Le Bonheur, where most physicians are affiliated with UT Health Science Center, has been critical. In addition to the resources the College of Medicine provides for obtaining and administering research grants, the academic environment brings together like-minded faculty committed to advancing their field.

“We have a mission as faculty members at an academic institution for scientific discovery and to improve care for the next generation. We take that responsibility in the Heart Institute and pediatric cardiac surgery extraordinarily highly,” he says. “Our mission is to continue to advance discovery within pediatric cardiac surgery across all parts of the Heart Institute, whether it be pediatric cardiology, pediatric cardiac critical care, or pediatric anesthesia.”

Since arriving in late 2024, Dr. Mettler has wasted no time building on this foundation. He recruited a partner from Johns Hopkins, Associate Professor Danielle Gottlieb Sen, MD, MPH; launched a pediatric cardiac research institute; and set ambitious goals for the future, including establishing subspecialty centers for complex conditions and advancing research in remote and device monitoring for children. Additionally, a top priority is to grow a program for adults born with heart disease.

“There are now more adults alive with congenital heart disease than kids. That tells us that we’ve gotten better at our job,” Dr. Mettler says.

“We have a bunch of these patients who are now adults, who have adult problems that need pediatric-type operations. That’s one of the things we do as congenital cardiac surgeons — care for adults with congenital heart disease.”

As a surgeon and a leader, Dr. Mettler says he has two main responsibilities. He strives to help the faculty reach their full potential, fostering their curiosity and ideas, and giving them the space to lead in clinical care. At the heart of it all, though, is a responsibility to patients and families, focused on excellent care and outcomes.