Court of Conscience respectfully acknowledges the Bedegal, Gadigal and Ngunnawal Peoples as the custodians and protectors of the land where each campus of UNSW is located

Court of Conscience respectfully acknowledges the Bedegal, Gadigal and Ngunnawal Peoples as the custodians and protectors of the land where each campus of UNSW is located

It is with immense pride that I introduce to you, dear reader, Issue 19 of Court of Conscience

The theme of this year’s issue, Beyond the Ivory Tower: Bridging the Gap Between Theory and Practice, is deliberately meta in its approach to academic discourse.

The term ‘ivory tower’ is often used to describe the perceived detachment of academia and its seemingly esoteric pursuits from the tangible needs of society. In the legal profession, the term is sometimes directed by practitioners and policymakers at the legal scholar, whose theoretical work is deemed ‘of little use’, if not completely abstract and irrelevant, to understanding ‘everyday law’.1 This perspective, however, fails to recognise that the law does not operate in a vacuum. From its formulation to its application, the law interacts with the society it governs. It is not immune to the ramifications of shifting social attitudes, political tensions, economic inequalities, or technological developments.

Legal academia is the response to the realisation that legal governance is more complex and difficult in practice than in theory. The need to assess the real-world impact of legal decision-making amid evolving socio-economic conditions underscores its importance. By bridging the gap between the law’s theoretical purpose and its practical function, legal academia also plays a crucial role in advancing social justice and systemic law reform.

In light of this perceived divide, Issue 19 contains 14 diverse yet incredibly topical articles that critically examine areas where tensions exist between what the law should do as compared to what it does. Each piece demonstrates, in its very existence, the reformative impact legal scholarship can have on the law, if only we heed its advice and ponder its reflections.

As my tenure as Editor-in-Chief draws to a close, I would like to take this opportunity to express my heartfelt gratitude to all who have been involved with the publication this year. First, I thank each of the authors who contributed to this issue, including Professor Rosalind Dixon, who kindly drafted the foreword. Thank you for entrusting our publication with your work and for sharing my vision for this year’s thematic. It has been an honour seeing your articles through to publication, and I hope you all share the immense pride I feel for this issue.

* Court of Conscience Editor-in-Chief.

1 Richard Brust, ‘The High Court vs the Ivory Tower’ (2012) 98(2) American Bar Association Journal 50, 52.

I also extend my sincere thanks to the anonymous peer reviewers who generously gave their time and expertise in reviewing the pieces; your input has been invaluable to the development of this issue.

As an entirely student-led publication, Court of Conscience would not have been possible without our hard-working and dedicated Editorial Board. It has been incredibly rewarding to work alongside each of you, and I thank you for your sustained diligence, insight, and friendship. In particular, I would like to thank Kayla Quang and Anonna Das for their endless support and camaraderie. You have continuously reminded me that no challenge is insurmountable, and that truly, the greatest reward in any endeavour are the friends made along the way.

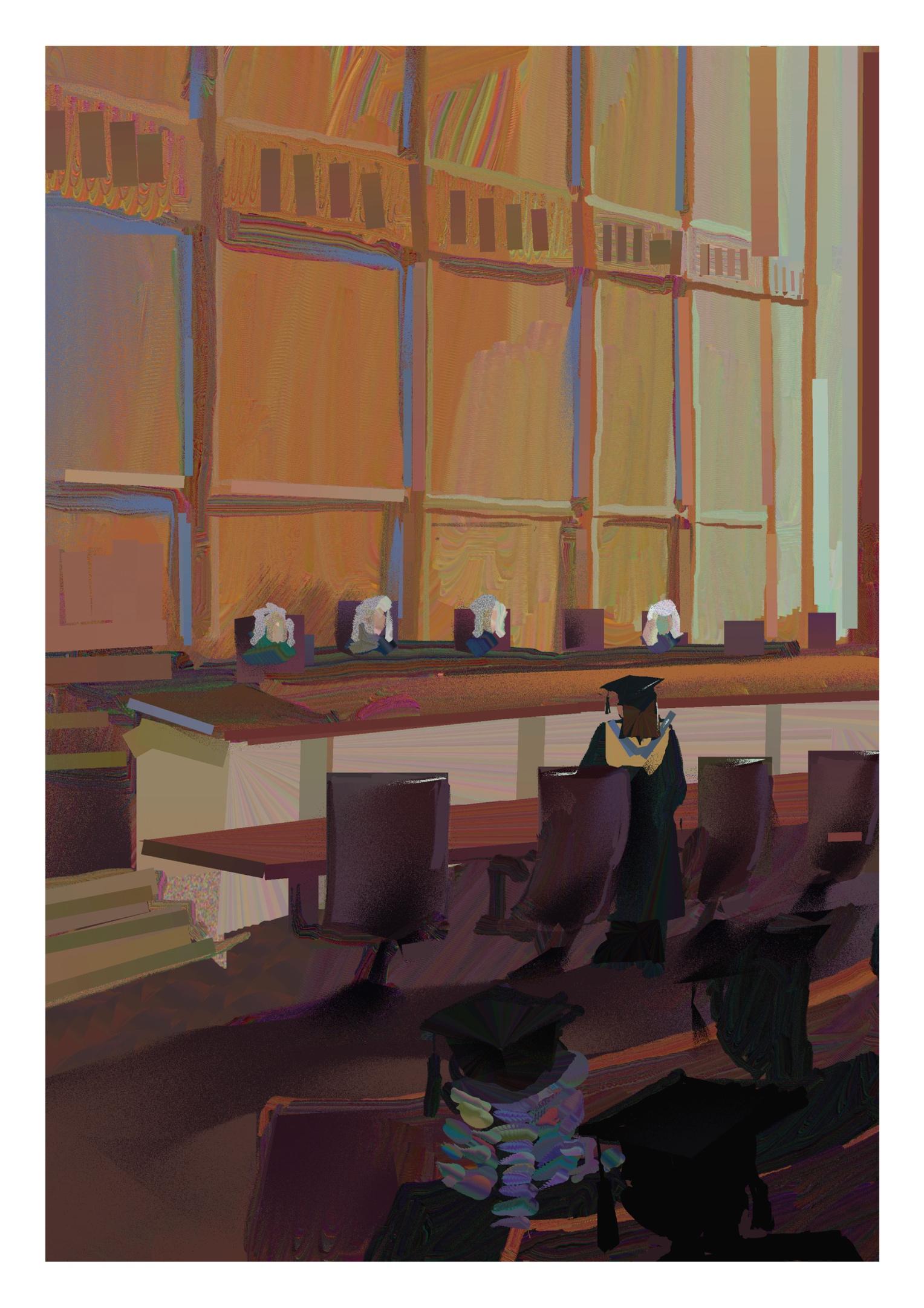

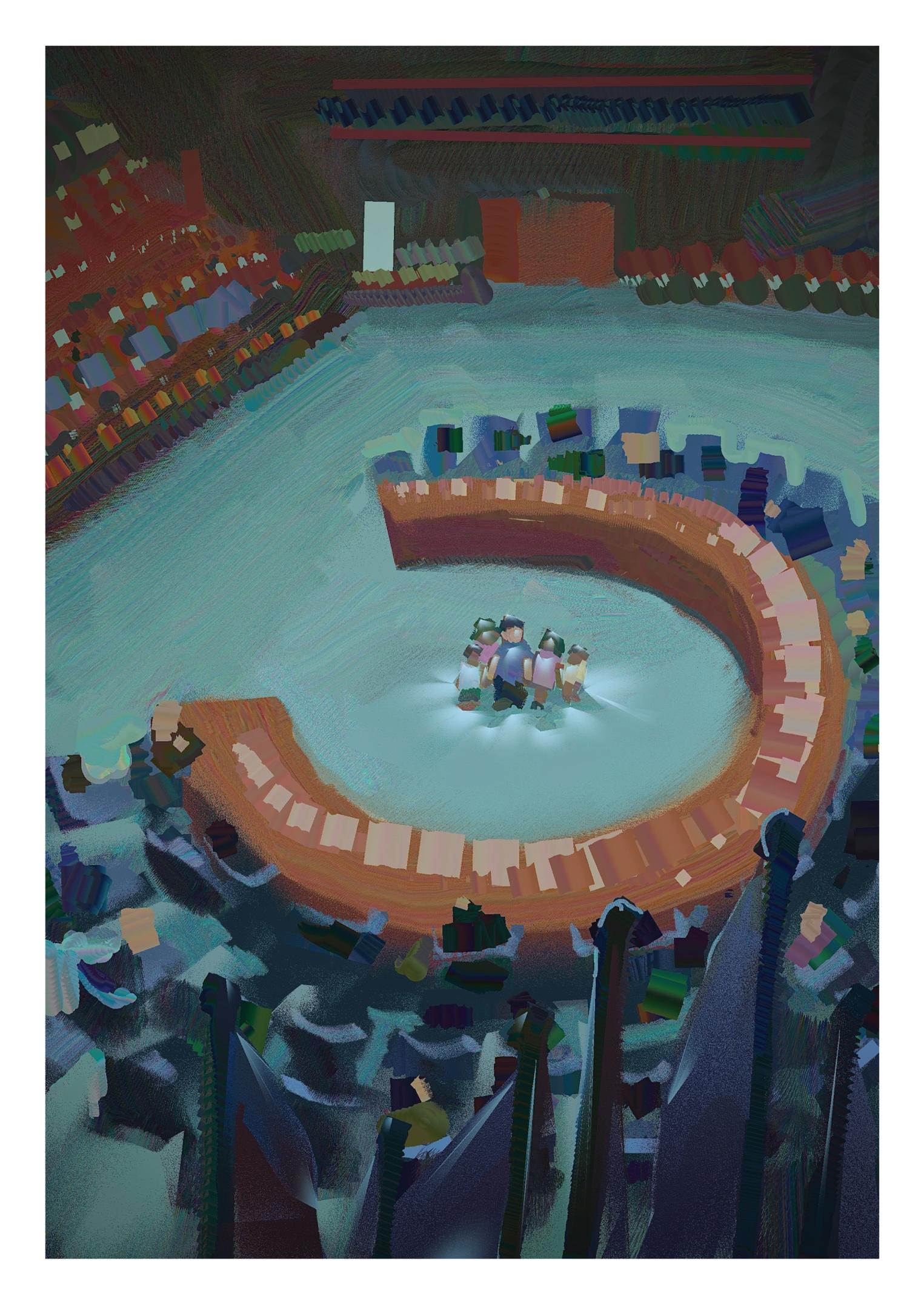

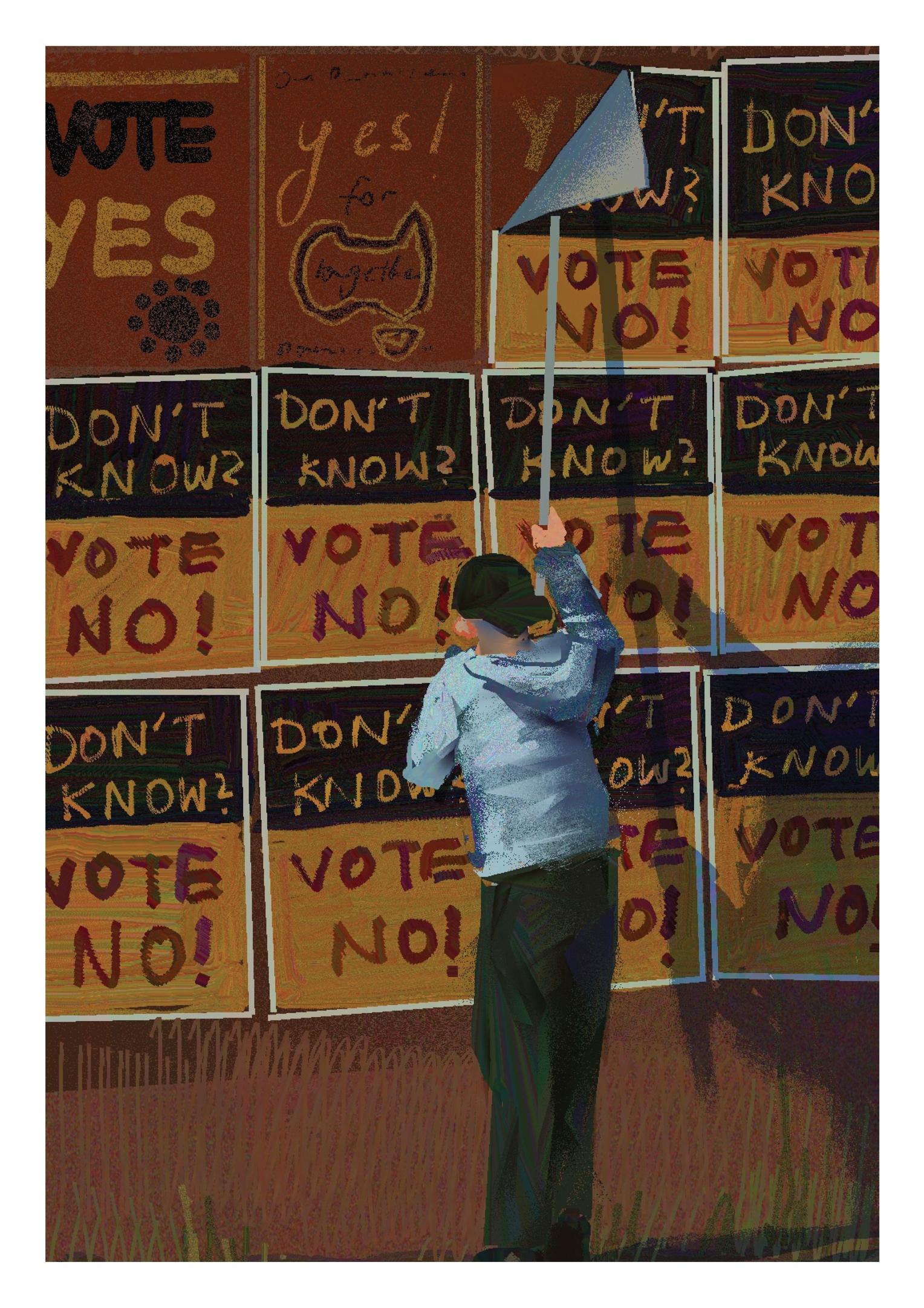

I also thank our artist, Darshni Rajasekar, for the beautiful illustrations that appear throughout the issue, and our graphic designer, Helaina Clare, for putting together this year’s publication.

Finally, I extend my gratitude to the UNSW Law Society for facilitating this publication and for allowing Issue 19 to be the latest in a series of progressive issues.

I hope you enjoy this issue, and that it resonates with you both as a source of practical guidance and theoretical reflection after all, it is possible (and critical) for academia to do both

ROSALIND DIXON*

Court of Conscience has a long tradition of publishing outstanding scholarship on issues of social justice and the law’s operation ‘on the ground’ not just on the books. This symposium on law ‘beyond the Ivory Tower’ continues this tradition. I am thus especially pleased to be invited to introduce the articles in the symposium, many of which are authored by friends and colleagues as well as the next generation of emerging legal voices.

But what does this call to go ‘beyond the Ivory Tower’ and bridge the gap between legal theory and practice really mean? How should we understand its implications for legal research, practice and teaching?

Universities play a critical role in conducting basic research, and teaching the next generation of students to understand both the logic of this research and the tools needed to continue it in the future. Going beyond the Ivory Tower, therefore, cannot mean destroying that tower or downplaying the significance of basic ‘blue sky’ research as the basis for later social, economic and political progress. Indeed, some contributors expressly note the dangers posed to social and environmental progress by universities adopting too short-term a focus, driven by the imperatives of the competitive grant cycle and university engagement priorities.1

Instead, what it can, and should, mean is the attempt to encourage research and teaching that constructs a bridge between this kind of foundational knowledge and the practical challenges of legal practice and reform in current socio-political conditions. A bridge of this kind can also be understood to have four key elements, or (in bridge design language) ‘foundations’: first, a commitment to orienting legal scholarship towards addressing the ‘dramas’ of pressing social, economic and political challenges; second, a commitment to studying law ‘in action’ or on the ground and not just on the books; third, a concern to orient some if not all legal scholarship and teaching towards a concrete project of legal reform; and fourth, a commitment to teaching law in a manner designed to encourage and support these other goals.

The four goals are clearly interrelated. To press for change, we must first seek to document and understand what is lacking in the legal status quo. To make change in a democracy, we must orient reform efforts towards actual real-world problems capable of motivating citizens and their

* Rosalind Dixon is Anthony Mason Professor and Scientia Professor in the School of Global & Public Law, UNSW Sydney.

1 Faith Gordon, ‘Beyond the Ivory Tower: How Academia Can Support Youth Climate Activism in Australia’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 115.

representatives to seek change. And to achieve true change, we must teach future lawyers the skills needed to make this change real in practice, as well as on the books. However, it is still useful to distinguish each goal as distinct elements of the project of bridging the theory-practice divide. Doing so also helps situate the rich and diverse contributions to the symposium itself.

Almost all contributors to this issue bridge the theory-practice divide by focusing on pressing issues of social justice in Australia today. The Honourable Robert French focuses on issues of First Nations justice, especially current debates over the idea of a treaty with First Nations peoples.2 Jill Hunter adopts a similar focus, albeit within the context of issues of criminal justice, culpability and sentencing.3 Ingrid Mathews and Sandra Schmutter do the same: together, they employ a rich and distinctive dialogic narrative style to highlight the challenge of achieving justice for First Nations citizens in a settler colonial society such as Australia, which has yet to fully grapple with its colonial history.4

Helen Gibbon and Ben Mostyn focus on the issue of drug regulation and criminalisation, specifically through the lens of statutory ‘deeming’ provisions in New South Wales’ drug laws.5 Aaryan Pahwa focuses on the challenge of creating an effective and accessible administrative review system in Australia,6 whereas Peta Spyrou explores what it means to create an effective and accessible model of disability rights protection.7 Beth Nosworthy likewise adopts a disability rights focus, exploring the challenge of creating ‘supported’ rather than substitute decision-making for those with intellectual disabilities and the intersection between this challenge and current understandings of the corporate form.8

Rebecca Dominguez and Catherine Renshaw grapple with the challenge of training effective but also resilient Australian lawyers capable of meeting the increasingly complex challenges of legal practice,9 while Mark Giancaspro is concerned with the challenge of training lawyers capable of meeting the challenges of practice in an increasingly complex and challenging professional environment.10

2 Robert French, ‘Native Title, Justice and the Evolution of the Unwritten Law’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 3.

3 Jill Hunter, ‘“Bugmy,” You Know’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 19

4 Ingrid Matthews and Sandy Schmutter, ‘Shared Histories and the Colonial Present: A Message to Law Students and Teachers’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 9.

5 Helen Gibbon and Ben Mostyn, ‘The First Casualty of War is Truth: Legal Fictions and NSW Drug Laws’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 25

6 Aaryan Pahwa, ‘Accessibility in the ART: Clear on Paper, Blurred in Practice’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 49

7 Elpitha Spyrou, ‘Navigating the Legal Labyrinth in Education: The Challenges of Resolving Disability Discrimination Complaints’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 33

8 Beth Nosworthy, ‘Incorporated Support Structures: The Role of Conscience for the Individual and for the Law?’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 41

9 Rebecca Dominguez and Catherine Renshaw, ‘Bridging the Divide between Theory and Practice: The Transformative Impact of Experiential Legal Education’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 67.

10 Mark Giancaspro, ‘Donning the Chancellor’s Cloak: How Equity’s Playbook Can Help Reshape Legal Education in Australia and Fell the Ivory Tower’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 57.

Other contributors explore pressing issues of truly global concern. These include the challenge of addressing climate change (Faith Gordon),11 the rise of AI (Jeannie Marie Paterson),12 broader threats to the rule of law and democracy (Nikki Chamberlain),13 and the rights of children in conflict zones such as Gaza (Noam Peleg).14

But within this broad focus, contributors also adopt differing foci or emphases. For instance, in focusing on the challenge of delivering justice for First Nations Australians, Chief Justice French focuses on showing support for the idea of a treaty using the history of common law decision-making in this area,15 whereas Hunter focuses on the representation of First Nations peoples as criminal defendants, arguing that lawyers must have the skills needed to operationalise legal principles (such as the Bugmy principles on leniency in sentencing) when accounting for offender background and disadvantage.16 Chief Justice French likewise focuses the history of First Nations justice on the books and in practice, whereas Hunter focuses on a call for improved legal education aimed at developing future lawyers’ ‘soft’ skills in engaging clients and hard, but non-legal, skills in amassing and presenting statistical evidence.17

Gibbon and Mostyn are concerned with ‘law on the books’ and a contextual analysis of the international and political context for Australian courts’ harsh approach to the interpretation and enforcement of drug laws (including apparently ‘balanced’ evidentiary deeming provisions).18 They also suggest that this has implications for legal reform and education.19 Nosworthy focuses on studying models of supported decision-making on the ground, but as the basis for a call for legal reform.20 Pahwa and Spyrou focus on law in action, again with a view to reforming existing models of administrative review and anti-discrimination protection.21

Giancaspro critiques existing legal education with a view to offering concrete suggestions for more practical, experiential forms of legal education.22 Dominguez and Renshaw likewise emphasise the value of clinical and experiential forms of learning as a response to the challenges of practitioner skill and wellbeing they identify.23 Matthews and Schmutter call for greater engagement with narrative history, which represents one of the many ways for education lawyers to better understand their role in

11 Gordon (n 1).

12 Jeannie Marie Paterson, ‘Understanding AI Transparency and Literacy: Lessons from Consumer Credit Regulation’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 107

13 Nikki Chamberlain, ‘When Assaults on the Rule of Law, Separation of Powers and Access to Justice Become a Present-Day Reality’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 83

14 Noam Peleg, ‘Children, Gaza and the Relevancy of International Law’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 91

15 French (n 2).

16 Hunter (n 3).

17 French (n 2); Hunter (n 3).

18 Gibbon and Mostyn (n 5).

19 Ibid.

20 Nosworthy (n 8).

21 Pahwa (n 6); Spyrou (n 7).

22 Giancaspro (n 10).

23 Dominguez and Renshaw (n 9).

the representation of First Nations clients and the challenging of injustice in a settler colonial society.24 And Paterson examines the challenges of financial literacy education on the ground, through the lens of helping guide and inform the design of a realistic model of AI literacy training.25

A fifth and final element of bridging the theory-practice divide involves public advocacy by scholars. Some forms of media and public advocacy will almost always be an important part of closing the theory-practice divide. And scholars will often have a combination of expertise and authority in advocacy of this kind.

Of course, not all scholars will have the time, interest or capacity to engage in such advocacy nor will they have the time, interest or capacity to work on topics that lend themselves to this kind of advocacy. But many scholars will; and as Faith Gordon notes, scholars can play a role in supporting broader advocacy in civil society such as by youth climate activists through their approach to research and teaching.26

The challenge is simply to ensure that a role of this kind is not abused by broader political actors.27 This is a danger that Joe McIntyre and Liz Hicks identify and label the problem of ‘ivorywashing’.28 A leading recent example is also arguably a Deloitte report that cites academic work by my colleagues Nina Boughey and Lisa Burton, and hence purports to draw on academic expertise in support of the position it advances. However, it relies on AI-generated versions of citations that do not in fact exist.29

The solution, proposed by McIntyre and Hicks, is also to insist on a sharper distinction between scholarly evidence and opinion and that scholars using their expertise to advance an opinion do so in a way that is ‘consistent with the ethical and methodological constraints of the profession’.30 One could view this as consistent with existing calls for appropriate scholarly care and self-reflection,31 which have arisen in response to the general concern about scholarly activism or ‘scholactivism’.32

This, of course, is one concern that could be raised in response to a volume of this kind. However, all contributors go to great lengths to meet the requirements set out by McIntyre and Hicks of scholarly rigour and reflexity33 or of offering scholarly ideas in a fair-minded and nuanced way.

24 Matthews and Schmutter (n 4).

25 Paterson (n 12).

26 Gordon (n 1).

27 Cf Rosalind Dixon and David Landau, Abusive Constitutional Borrowing: Legal Globalization and the Subversion of Liberal Democracy (Oxford University Press, 2021).

28 Joe McIntyre and Liz Hicks, ‘Ivory-Washing or Expertise? The Responsibilities of Legal Academics in Political Discourse’ (2025) 19 Court of Conscience 97

29 Krishani Dhanji, ‘Deloitte to Pay Money Back to Albanese Government after Using AI in $440,000 Report’, The Guardian (online, 6 October 2025) <https://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2025/oct/06/deloitte-to-pay-money-back-to-albanesegovernment-after-using-ai-in-440000-report>.

30 McIntyre and Hicks (n 28) 97.

31 See Liora Lazarus, ‘Constitutional Scholars as Constitutional Actors’ (2020) 48 Federal Law Review 483; Adrienne Stone, ‘A Defence of Scholarly Activism’ (2023) 13(1) Constitutional Court Review 1.

32 See, eg, Tarunabh Khaitan, ‘On Scholactivism in Constitutional Studies: Skeptical Thoughts’ (2022) 20(2) International Journal of Constitutional Law 547.

33 McIntyre and Hicks (n 28).

For that, and for the breadth of their work and vision, I commend them all as well as the student editors for conceptualizing and implementing this important project.

Martin Luther King said that ‘the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice’.1 Roscoe Pound, writing in The Spirit of the Common Law in 1921 spoke of a ‘world-wide movement for socialisation of law, the shifting from the abstract individualist justice of the past century to a newer ideal of justice …’2 The optimistic observer of the Australian legal system may see a step-wise evolution linked to changing societal perspectives.

The worldwide movement of colonisation of inhabited territories by the United Kingdom brought the common law to those territories. That which was imported into Australia did not bring with it just engagement with the First Peoples of the Australian colonies. That is despite official instructions along the lines of those from the Imperial Government to Arthur Phillip in 1787. He was required ‘to endeavour by every possible means to open an Intercourse with the Natives and to conciliate their affections, enjoining all Our Subjects to live in peace and amity with them’ 3

In 1833, the Supreme Court of New South Wales described the first peoples of that colony as ‘wandering tribes … living without certain habitation and without laws [who] were never in the situation of a conquered people…’4 The land being ‘settled’ was the property of the Crown from the time of annexation.5 That was still the position in 1889 in the Privy Council in Cooper v Stuart6 where Lord Watson described the colony of New South Wales, and thereby the Australian colonies generally, as ‘a tract of territory practically unoccupied, without settled inhabitants or settled law, at the time when it was peacefully annexed to the British dominions’ 7 Cooper v Stuart solidified a historical fiction into a quasi-constitutional principle. It was necessarily followed by Sir Richard Blackburn in the first Australian native title case Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd (‘Milirrpum’) 8 in which the Judge rejected a claim by the Yolngu people seeking

* The Hon Robert S French AC is the former Chief Justice of Australia (2008–2017).

1 Martin Luther King, ‘Remaining Awake Through a Great Revolution’ (Speech, Washington National Cathedral, 31 March 1968)

2 Roscoe Pound, The Spirit of the Common Law (Marshall Jones Company, 1921) 7

3 Historical Records of Australia, Governor Phillip’s Instructions, 25 April 1787 (UK) 15.

4 McDonald v Levy [1833] 1 Legg 39, 45.

5 Attorney-General v Brown [1847] 1 Legg 312; Williams v Attorney-General (NSW) (1939) 16 CLR 404.

6 [1889] 14 App Case 286.

7 Ibid 291; see also Re Southern Rhodesia [1919] AC 211, 233–4; Amodu Tijani v Secretary, Southern Nigeria [1921] 2 AC 399 which seemed to establish some form of sliding scale for society whose laws and customs were cognisable by the common law.

8 (1971) 17 FLR 141 (‘Milirrpum’).

orders invalidating the grant of mineral leases at Gove on the basis of customary indigenous ownership of the land. It was he said ‘… beyond the power of this Court to decide otherwise than that New South Wales came into the category of a settled or occupied colony’.9 The evidence before him told a different story, as he recognised, showing:

a subtle and elaborate system highly adapted to the country in which the people led their lives, which provided a stable order of society and was remarkably free from the vagaries of personal whim or influence. If ever a system could be called ‘a government of laws and not of men’, it is that shown in the evidence before me.10

Between the Milirrpum judgment in 1971 and the Mabo (No 2)11 decision in 1992, significant changes occurred in societal and judicial perspectives.

The Commonwealth Government established a Royal Commission headed by Justice Edward Woodward which proposed land rights legislation for the Northern Territory providing for the grant of statutory titles to traditional owners based upon inquiry and recommendation by an Aboriginal Land Commissioner.12 The moral perspectives informing the scheme were reflected in its objectives as proposed by Woodward J, which included ‘[t]he doing of simple justice to a people who have been deprived of their land without their consent and without compensation’.13

Much litigation ensued between applicants for the statutory titles and the Northern Territory Government. Thirteen cases under the Act came before the High Court before its epochal common law decision in Mabo (No 2) in 1992. In those cases, the Court was exposed repeatedly to the statutory concepts of traditional ownership.14 As appears below, it was not the only example of reactionary Territory and State governments assisting the development of a more just relationship between First Peoples and Australian society generally by their dogged resistance to it.

An event that had its impact on the effectiveness of the ultimate common law recognition that came with Mabo (No 2) in 1992 was the 1967 Constitutional Referendum. That Referendum amended the power conferred by s 51(xxvi) to make special laws for the people of any race. It removed the exclusion from that power of ‘the Aboriginal race in any State’.15 By removing that exclusion it extended the power of the Parliament so that it could make laws for Aboriginal people. That power underpinned the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (‘Native Title Act’), which created the statutory framework for common law recognition of native title effected by the Mabo (No 2) decision. It was that power which the High

9 Ibid 244.

10 Ibid 267.

11 Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 (‘Mabo (No 2)’).

12 Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth).

13 Aboriginal Land Rights Commission, Parliament of Australia, Woodward Royal Commission of Inquiry into Aboriginal Land Rights in the Northern Territory (Parliamentary Paper No 69, April 1974) 2 [3] (‘Woodward Commission’).

14 See generally Robert French, ‘The Role of the High Court in the Recognition of Native Title’ (2002) 30(2) University of Western Australia Law Review 129.

15 Australian Constitution s 51(xxvi) (‘Constitution’).

Court invoked in 1995 in its finding, against a challenge by Western Australia, that the Native Title Act was a valid law of the Commonwealth.16

Another important development which was to provide protection for common law recognition of native title, was the enactment of the Race Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth) (‘Race Discrimination Act’). That Act gave effect to Australia’s obligations under the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 17 The validity of the Act as an exercise of the external affairs powers of the Commonwealth was challenged by Queensland in 1982 in Koowarta v Bjelke-Petersen. 18 It was said to be a valid exercise of the power by a 4–3 majority.

The Racial Discrimination Act underpinned the framework protective of native title recognised under the Native Title Act. It meant that no State Government could, by law or administrative action, extinguish or impair native title rights or interests without compensation, i.e. on terms less favourable than those available to other persons faced with compulsory acquisition of their land under State law. That was because of the paramount provision, s 109 of the Constitution, rendering State laws inconsistent with a Commonwealth law invalid to the extent of the inconsistency. Past acts of uncompensated extinguishment which had occurred after the passage of the Racial Discrimination Act were validated by the Native Title Act enacted in 1993, but subject to an entitlement to compensation.

The Mabo (No 2) litigation was instituted in 1982 in the original jurisdiction of the High Court. In 1985, Queensland tried to pull the rug from under the feet of the plaintiffs by passing an Act extinguishing native title throughout the Torres Strait.19 In 1988, in Mabo v Queensland (No 1), 20 the High Court, by majority, held the Queensland Coastal Islands Declaratory Act 1985 (Qld) (‘State Act’) to be invalid for inconsistency with the Racial Discrimination Act. The question whether native title could be recognised at common law awaited determination. That determination came four years later in the historic decision of the High Court in Mabo (No 2).

Recognition of historical injustice pervaded the majority judgments. Brennan J observed of past precedent, with the agreement of Mason CJ and McHugh J, that ‘no case can command unquestioning adherence if the rule it expresses seriously offends the values of justice and human rights (especially equality before the law) which are aspirations of the contemporary Australian legal system’.21

The common law recognition of native title rights and interests represented what was later described as a ‘constitutional shift’ in the common law.22 Nevertheless, it had shortcomings when viewed through the lens of ‘simple justice’ of the kind that informed the Aboriginal Land Rights

16 Western Australia v Commonwealth (1995) 183 CLR 373.

17 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, opened for signature 7 March 1966, 330 UNTS195 (entered into force 4 January 1969).

18 (1982) 153 CLR 168.

19 Queensland Coastal Islands Declaratory Act 1985 (Qld) (‘State Act’).

20 (1988) 166 CLR 186 (‘Mabo (No 1)’).

21 Mabo (No 2) (n 11) [29].

22 Wik Peoples v Queensland (1996) 187 CLR 1, 182 (Gummow J).

(Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth) in the Northern Territory.23 The new rules established in Mabo (No 2) provided for the mapping of communal rights and interests arising under traditional laws and customs into rights and interests in the domain of the common law. The mapping was effected by what could be called rules of recognition. They embodied conditions including continued connection with the relevant country dating back to the time of colonial annexation. They would not apply where a valid law or dealing affecting the land disclosed a clear and plain intention to extinguish that native title. This was developed into a test of inconsistency between the allegedly extinguishing act and native title rights and interests at common law.

To much consternation, the High Court of Australia in Wik v Queensland in 1996 held that the grant of a pastoral lease was not necessarily inconsistent with the continuance of common law native title rights and interests underlying it. The High Court was criticised stridently for its decision and there was a degree of legislative backlash with amendments to the Native Title Act in 1998.

Ultimately, calm returned as the sky did not fall in on pastoral leaseholders. And ultimately mere inconsistency with native title rights was held not to necessarily evidence a plain and clear intention to extinguish them.24

That said, it is of some importance to bear in mind that extinguishment was a common law concept embodied in the rules of recognition of native title at common law. It did not and could not have any operation within the systems of traditional law and custom followed by First Peoples’ societies.

Behind the moving wavefront of claims for native title recognition under the Native Title Act has come the developing law of compensation for extinguishment. As noted above, compensation is payable under the Native Title Act for past acts, validated by the Native Title Act, of uncompensated extinguishment which postdated the Racial Discrimination Act. The measure of compensation assessed by the High Court decision in its historic Timber Creek Case25 covered both economic and noneconomic loss. The latter was assessed by reference to the cultural or spiritual aspects of the impact of extinguishment.

In 2025, a further important decision was delivered by the High Court. The Court found that pre-1975 extinguishments by the Commonwealth were capable of constituting acquisitions requiring just terms compensation under s 51(xxxi) of the Constitution. That was Commonwealth v Yunupingu 26

The Mabo (No 2) decision involved no compromise with the notion of crown sovereignty over the land and waters of the colonies which was emphatically asserted by the High Court in 1979 in Coe v Commonwealth 27 An attempt to revisit the sovereignty issue was rejected in a number of subsequent

23 Woodward Commission (n 13) 2 [3].

24 Queensland v Congoo (2015) 256 CLR 239.

25 Northern Territory v Griffiths (2019) 269 CLR 1.

26 (2025) 99 ALJR 519.

27 (1979) 24 ALR 118; 53 ALJR 503.

decisions of lower courts.28 That rejection does not involve a rejection of the concept of two concurrent systems of law, the general Australian constitutional legal system and systems of the kind acknowledged by Blackburn J in Milirrpum.

This has implications for the concept of treaty. It does not involve a compromise of constitutional principle by relying upon a premise of competing sovereignties. Where connection is maintained, traditional authority in relation to land and waters continues under traditional law and custom. The general Australian legal system cannot affect that traditional authority. Nor can that traditional authority change the authority of the Crown over land and waters save to the extent that the common law and/or statute creates rights and interests reflective of it.

The conception, derived from the common law of native title, of parallel systems in areas where traditional law and custom survives, is applicable to the development of a treaty, compact or agreement between Commonwealth, State and Territory governments and First Peoples. The question is not one of constitutional law, but of political will in the pursuit of ‘simple justice’.29

Australian society has come a long way since 1901. It still has a long way to travel in its recognition of and interaction with its First Peoples. Despite fits and starts and reversals, we can say that the arc of the moral universe tends, albeit slowly, towards justice.

28 See generally Nyangpul v State of New South Wales [2025] NSWCA 119 and cases cited therein.

29 Woodward Commission (n 13).

Nan Sib would put on a hairnet, or a scarf, she always covered her head, and go into town [the mission is five miles from town, the reserve about 20 miles] when we was all in town with nan she’d say ‘c’mon now darlins we have to be civilised now’. And we’d listen to her, we respected her. And we’d say okay nan.

What did that mean, ‘being civilised’, when you went into town?

It meant behaving ourselves in front of white people.

Ingrid: I love this story. I have heard it many times. I picture Nan Sib, a twinkle in her eye, teaching her grandchildren to navigate surveillance by white society and its law. From stories like this one, I have come to wonder at what we are taught is civilised: the brutal reign of colonial violence that founds a penal colony like New South Wales.1

There remains a considerable gap between what law students are taught and what lawyers representing Aboriginal clients need to know for effective advocacy. In a settler colonial state, we are all exposed to false narratives, harmful stereotypes, deficit discourses, presumed criminality, and other distortions of Aboriginal life through the colonial lens.

Preparing students to effectively represent Aboriginal peoples must therefore embrace a wider truth-telling function,2 including the foundational identity of colonial (‘common’) law on Country.3 Laws of the colonising power are enforced against sovereign Aboriginal people on their unceded lands

* Ingrid Matthews is a white academic living and working on unceded Dharug lands

# Sandy Schmutter is an Aboriginal grandmother and great-grandmother raising children on Country.

1 Learning from story is a characteristic of human societies, and law students continue to learn foundational concepts through parable and allegory. See, eg, Lon Fuller, ‘The Case of the Speluncean Explorers’ (1949) 62(4) Harvard Law Review 616; Donahue v Stevenson [1932] AC 562, 580, invoking the Book of Luke 10:29.

2 Bridget Cama and Corey Smith, ‘Responding to Uluru Statement’s Call for Truth’, Australian Pro Bono Centre (Web Page, 15 December 2024) <https://www.probonocentre.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Pro-Bono-Voco-Dec-2024_JEC.pdf>.

3 The law of the colonising power is a law of the land elsewhere England but not the law of the land here.

and waters without consent.4 In contrast, the law of the land, also called First Law5 and Raw Law6, is universal and eternal, because the land is the source of the law 7 Law of the land embodies connections and obligations to culture, kin, and Country. In this article we mix together our connections and obligations with personal and scholarly accounts of colonial laws.8 We ask legal educators to draw on a framework of legal pluralism to critique re/presentation of the common law as paramount. When negotiating white society and its colonial laws, Aboriginal people deserve legal representatives with a shared understanding of our shared history, law of the land, and the colonial present.

On a long summer day in December 2013, the authors sat down to discuss teaching law students about working with Aboriginal people. This was in the formative years of the Indigenous Knowledges Graduate Attribute. Our conversation focused on a foundational Bachelor Laws (LLB) course.9

If you could say one thing to future lawyers about Aboriginal people and the law, what would it be?

Give the benefit of the doubt. Treat everyone equally. Give us the benefit of the doubt 10

This quote was later placed at the top of a new chapter in the first-year textbook.11 It was chosen to encapsulate a gaping maw between lofty ideals and brutal racism of the criminal law. Here, we reflect on another gap, between our shared history and the colonial present. The gap is refracted across social spheres and institutions, from parliaments to police stations, in churches and board rooms. Law schools are no exception. At the same time, we honour long struggles by elders and ancestors creating opportunities fulfilled by later generations. We celebrate Land Back and Blak excellence, and

4 Irene Watson, ‘There is No Possibility of Rights Without Law: So Until Then, Don't Thumb Print or Sign Anything!’ (2000) 5(1) Indigenous Law Bulletin 4, 4–7.

5 See Anne Poelina, ‘First Law a Gift to Healing and Transforming Climate and Just Us!’ (2024) 14(5) Journal of Cultural Heritage Management and Sustainable Development 767.

6 See Irene Watson, Aboriginal Peoples, Colonialism and International Law: Raw Law (Routledge, 1st ed, 2015).

7 See C F Black, The Land is the Source of the Law: A Dialogic Encounter with Indigenous Jurisprudence (Routledge, 1st ed, 2011).

8 For this article, we chose ‘mixing together’ as a lay term, rather than implying a more formal methodology. Contemporary Indigenous methodologies describe this type of ‘mixing’ in various ways, including (in English) weaving, braiding, cultural interface, two-way seeing, and the Yolηo concept Ganma. See, eg, Eddie Synot et al, ‘Weaving First Peoples’ Knowledge into a University Course’ (2021) 50 Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 222; Courtney Ryder et al, ‘Indigenous Research Methodology Weaving a Research Interface’ (2020) 23(3) International Journal of Social Research Methodology 255.

9 In late 2008, the (then) University of Western Sydney (UWS) was allocated $900,000 by the Department of Education, Employment and Workplace Relations from the Diversity and Structural Adjustment Fund for the project Embedding an Indigenous Graduate Attribute: Bernice Anning, ‘Embedding an Indigenous Graduate Attribute into University of Western Sydney’s Courses’ (2010) 39 Australian Journal of Indigenous Education (2010) 40, 44. See also Australian Government, ‘Review of Higher Education Access and Outcomes for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander People’ (Final Report, Department of Education, July 2012) <https://www.education.gov.au/download/2658/review-higher-education-access-and-outcomesaboriginal-and-torres-strait-islander-people/3703/document/pdf>; Marcelle Burns, ‘Are We There Yet? Indigenous Cultural Competency in Legal Education’ (2018) 28(2) Legal Education Review 1.

10 Micheal Head, Scott Mann and Ingrid Matthews, Law in Perspective: Ethics, Critical Thinking and Research (UNSW Press, 3rd ed, 2015) 345

11 Ibid.

Indigenous people doing truly transformative work. There are more Indigenous lawyers and legal scholars than ever, and more Aboriginal graduates leading organisation established by and for Aboriginal people.12

These achievements co-occur with increasing criminalisation and incarceration of Aboriginal people under harsh and punitive state crime policies. Closing the Gap, as a policy framework, is comprehensive and aspirational.13 Yet the colonial gap, between non-Indigenous and Aboriginal life at the margins, is getting wider. Aboriginal children are still being stolen from their families, by police and child removal officers.14 In unsentimental terms, increasing Aboriginal participation in law schools and the legal profession cannot counter harsh and punitive policies and practices that invariably and therefore purposefully cause the same outcomes every time.15

It is in this context that we submit our personal perspective on what is at stake. We are two women who have dealt extensively with police and child removal officers disrupting our family life. Our children are first cousins, and we take our Aunty obligations seriously. Sandy is a Black grandmother and great-grandmother raising children on Country. Ingrid is a white woman and academic who moved (back) to Sydney, raising her Aboriginal children on Dharug lands. Over some thirty years, a recurring theme has been raising our children in their culture. We especially want to share our perspective with law students who will represent Aboriginal people, and their teachers.

12 The first free shop front legal service in the country was established in Redfern in 1970, during the post-1967 referendum inertia that characterised coalition (the Holt, Gorton, and McMahon) governments. This was a time of prominent land rights struggles, including the Tent Embassy in Canberra, leading to a (brief) period of substantial federal reforms under the Whitlam government (1972–75). See Gary Foley, ‘White Police and Black Power’, Aboriginal Legal Service (Web Page, 9 July 2021) <https://www.alsnswact.org.au/white_police_black_power_1>.

13 The history of Close The Gap/Closing the Gap has become somewhat muddied by the Rudd government decision to announce CtG policy commitments alongside his National Apology to the Stolen Generations and their descendants. Closing the Gap remains a substantive, evidence-based policy framework and the annual report is tabled each year on the anniversary of the Apology (13 February). One of the worst performance areas every year is the criminal law: Australian Government, ‘Closing the Gap Targets: Key Findings and Implications’ (Research Report, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2025) <https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/indigenous-australians/closing-the-gap-targets-key-findings-implications/contents/criminaljustice>.

14 Ingrid Matthews and Lynda Holden, ‘The Colonial Logic of Child Removal’ (2023) 29(3) Australian Journal of Human Rights 551.

15 The rate at which First Nations children are incarcerated is even more ‘disproportionate’ (more than half of all incarcerated children in every jurisdiction) than Indigenous adults (around a third of the prison population, nationally): see ‘Youth Detention Population in Australia 2024’, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (Web Report, 13 December 2024) <https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/youth-justice/youth-detention-population-in-australia-2024/contents/summary/the-numberof-young-people-in-detention>; Australian Government, ‘The Health and Wellbeing of First Nations People in Australia’s Prisons 2022’ (Publication, Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 29 May 2024) 1 <https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/9e2c34861c45-40e6-883f-ed2d3e329da2/aihw-phe-342-The-health-and-wellbeing-of-First-Nations-people-in-Australia-s-prisons2022.pdf?v=20240508153645&inline=true>. It is worth noting that a majority of incarcerated children are presumptively innocent at law. According to the NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research, in December 2024 there were 225 incarcerated children and young people in New South Wales, and 129 are Aboriginal (57%). More than three quarters, or 172 incarcerated children and young people, were on remand (53 were sentenced). The ‘increase since December 2023 is mainly due to an increase in young people on remand’: ‘Youth Custody Numbers in NSW up by Almost a Third Since 2023 Due to a Rise in Bail Refusal’ NSW Bureau of Crime Statistics and Research (Web Page, 18 February 2024) <https://bocsar.nsw.gov.au/media/2025/mrcustody-dec2024.html>.

Figure 1 (left): Rainbow Serpent Mosaic (the Mill Hole, Walcha) designed with Aboriginal local people and by Waanyi artist Gordon Hookey.

Figure 2 (right): Road signs reflect colonial norms of the wealthy ‘New England’ pastoral district. British authorities conducted ‘musters’ of colonial-settler people and stock. Records of Aboriginal people were called blanket returns 16

I’m from Walcha. My dad was born in Gunnedah and his mum Nan Sib was born in Woolbrook. Pop [maternal grandfather], he’s from Taree and Gran Morris [maternal grandmother] she’s from Tingha. They always say to follow the maternal side. So that’s what I do. And it still goes down, that linage, those stories and songlines

[Ingrid asks for clarity about Country].

People ask me, are you Dunghutti, are you Anaiwan? I say ‘I’m a bitzer’. When Blackfellas bicker between themselves about who owns what, they can’t see eye to eye and come together as one. And if we did [come together as one] that Pauline Hanson wouldn’t have a leg to stand on

We go directly to the topic of representing Aboriginal clients.

Own what you’re going to do. Own the courtroom. Be aware what you’re going to go in there to do. Don’t go in there and get torn to pieces. A lot of these lawyers go in there and stumble

16 Until 1967, s 127 of the Australian Constitution prohibited counting Aboriginal people as people in the census. A collection of NSW ‘blanket lists’ can be viewed at the Museums of History NSW website: ‘Records of 19th Century Blanket Lists and Returns of Aboriginal People’ Museums of History New South Wales (Web Page, 2025) <https://mhnsw.au/guides/19th-century-blanketlists-and-returns-of-aboriginal-people/>.

17 This sub-heading references Irene Watson: Irene Watson, ‘First Nations Stories, Grandmother’s Law: Too Many Stories to Tell’ in Heather Douglas et al (eds) Australian Feminist Judgments: Righting and Rewriting Law (Hart Publishing, 2014) 41, 50.

on what they can do for you and what they can’t do for you. They need to know what they’re going in there for. Do your homework. Do your ground work. Go into bat for people with confidence.

This is excellent general advice, but it is also context specific. In Aboriginal communities, and particularly among repeatedly criminalised Aboriginal people, legal representation often provided by overworked junior solicitors is infamously underwhelming.

The government lawyers, they only do what the government pays them to and that’s all. They don’t go any further than that. They don’t get you out of the situation you’re in. Or you get probation and parole and then if you miss an appointment [the lawyer] says you did the wrong thing. You might be sick and you still have to go to some training program or whatever, or if they’re too white, or with someone you don’t get along with. Then if you don’t go they send you to be re-assessed, to be re-herded (sic), or back to gaol. Then you’re a repeat offender You feel like you’re worth nothing Every time, Blackfellas will get the raw end of the stick Look at the statistics, more Blackfellas get sent back to gaol than white. Probation and parole wouldn’t have a job if nobody went to gaol

This leads to talking about ‘presumed criminality’ of Aboriginal people as a colonial (dominant white cultural) norm,18 but first, Sandy shares this memory.

I remember a probation officer, probation and parole, he was really nice. When they got locked up they would come in him and his wife and he’d make sure they were okay. Any time a Blackfella got locked up he’d go to see them.

Ingrid: He probably saved a few lives.

Sandy: He did.

Returning to lawyers, we think about how the legal profession and legal academy can become more aware of ingrained ‘prejudice’.19 On judgement and pre-judgement prejudice and presumed criminality, Sandy says:

Someone says oh you gotta go see a lawyer. I want that lawyer to say what do you need to see me for? To listen. You pour everything out for them on the table and they turn around and move to another place. Then another lawyer comes in and they think they’re above you and

18 See Amanda Porter, ‘Decolonising Policing: Indigenous Patrols, Counter-policing and Safety’ (2016) 20(4) Theoretical Criminology 548; Ingrid Matthews and Nigel Stobbs, ‘Affirmative Consent and Patriarchal Paradigms of Power in the Criminal Law’ (2025) 48(2) University of New South Wales Law Journal 474.

19 In many local usages, ‘prejudice’ signals ‘racism’ in Aboriginal English. As the reader can see, the article moves between formal, conversational, and Aboriginal English throughout. All the italicised text is direct quotes from Sandy, with small edits for clarity.

don’t listen to a word you say. They’re judging, trying to judge what the person is like, or what that person has done, before they do the homework. Judging me before you even know what I’m about. Or don’t want to hear what I have to say. A lot of lawyers say ‘you just do this’ and put your head on a chopping block.

This is difficult terrain. How can lawyers find out what the person is like? It is also a structural problem: if the lawyer is not from the local area, how can they know community? Long histories and deep connections are overlaid by colonial disruption and widely different and highly traumatic experiences such as segregation, forced removal and assimilation, and exemption.20 How can a lawyer speak on Country, on behalf of Aboriginal people, without ‘background work’ without being, quite literally, grounded in place?

You go in there [the court] and someone just cuts the lawyer down and then they don’t say no more. So you gotta know what you’re gonna say. You have to own it. Do your background work so you know exactly what you’re gonna go in and do. Otherwise you’re just looking at papers and saying ‘you’re charged with this you’re charged with that’. Lawyers with no idea what background [Aboriginal clients] have, or who they are. You need to know.

We talk about choosing the Walcha town sign photo for this article, invoking colonial musters and blanket lists.

That’s what they used to do, herd Blackfellas up and put them onto reserves like cattle and sheep. They used to put arsenic in the sugar and the flour. They gave out tents, and them government blankets. That’s what they give you in the cells too. Them old itchy grey government blankets

As with ‘prejudice’ (pre-judge) and ‘background’ work (connection to earth),21 we notice the homonym herd/heard. Being herded and not being heard is too often how Aboriginal people experience colonial law, including processes the system itself calls a hearing. The courtroom conversation moves to this memory from the 1980s:

This one time [cousin and her now-husband] came down to Walcha. We were at the New England [hotel]. This whitefella came over and told them quiet down. I said whoo up they’re not doing anything wrong. He called me a Black something, I don’t remember, so I said you can go and get fucked you white C. He had me charged for it. The police came and they took

20 Exemption certificates, a policy of forced assimilation, required Aboriginal people to sever all ties with their families, language, and culture. Police and other authorities could demand an Aboriginal person moving through white-controlled spaces produce the exemption certificate at any time. See, eg, Lucinda Aberdeen and Jennifer Jones (eds) with Aunty Judi Wickes and Aunty Kella Robinson, Black, White and Exempt: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Lives Under Exemption (Aboriginal Studies Press, 2021).

21 Many Aboriginal cultural ways ceremonially mix dirt or earth to put or rub on skin, thereby literally and symbolically creati ng connection to Country.

me to the police station. To charge me. I went to court over it. It was so white white white. I got fined. And the judge turned around and said ‘well Miz Schmutter that was a very racist remark’. I didn’t say nothing.

In ‘Grandmother’s Law: Too Many Stories to Tell’, Tanganekald Meintangk Portuwutj and Bunganditj Distinguished Professor Irene Watson writes of laws not repealed, nor overturned, but buried.

Patriarchy was imposed, and with it came another law way, one which buried the laws of the land and the laws of women.22

The land is holding the law, buried beneath patriarchy and concrete that are smothering Country. At the heart of this article are just a few of these ‘too many stories’. We want to make visible the ways colonial law functions to sanction to separate and punish Aboriginal people. Separation and punishment operates to sever connection to kin and Country, and this is the colonial project.23

I tell my students, ‘when you get these jobs that you have been so brilliantly trained for, just remember that your real job is that if you are free, you need to free somebody else. If you have some power, then your job is to empower somebody else’.24

Non-Indigenous people from colonial, settler, and migrant communities powerfully benefit from the continuing forced displacement of First Peoples away from Country, displacement into poverty, foster homes, police cells, and prisons.25 Here, we advocate for recognition of colonial law’s violence.26 In sharing the our perspectives, we recognise Grandmothers and their law, knowledgekeepers and truth-tellers, and students and teachers we meet along the way.27

Listen to what the client has to say. When they’re judging you they don’t want to hear what I have to say. If you don’t get that point across, it stays the same, nothing will change. If someone

22 Watson (n 17) 50.

23 Sandy O’Sullivan, ‘The Colonial Project of Gender and Everything Else’ (2021) 5 Genealogy 67; Chelsea Watego, Another Day in the Colony (University of Queensland Press, 2021).

24 Interview with Toni Morrison (Pam Houston, O Magazine, November 2003).

25 Ingrid Matthews and Lynda Holden, ‘The Colonial Logic of Child Removal’ (2023) 29(3) Australian Journal of Human Rights 551.

26 Maria Giannacopoulos, ‘Law's Violence: The Police Killing of Kumanjayi Walker and the Trial of Zachary Rolfe’ in Chris Cunneen et al (eds) International Handbook of Decolonizing Justice (Routledge, 2023) 81.

27 The authors thank the reviewer who shared this perspective, which we add with permission while maintaining anonymised peer review protocol: The demand whether explicit or implicit as in nan here relating to her grandchildren in town is something I have experienced and most Blakfullas would have. It’s an experience that is a link to so much of the experience of the legal system and colonial society more broadly, beyond what people might first read and think. It’s not because we aren’t civilised of course, but because of how the system sees and treats us that to behave in a way otherwise to even have fun and experience love can be held against us. So, we police ourselves because of the effect of the system which doubles down itself despite changes.

goes into bat for them, then they might turn their life around. Good lawyers out there can make a difference and change a few things. Someone could pick it up and say ‘this is exactly right’

Law schools teach their students from cases and statute. Ideally, students become skilled in statutory interpretation, legal method and lawyers’ ethical obligations. They learn other things argument and critical analysis, and communication skills all typically in a formal or doctrinal context. Learning these things may not always be an exciting process but they are fundamental to building a lawyer. But preparing for real-world legal practice takes more.

To illustrate my point, I am going to discuss what are often called ‘soft’ skills, and specifically interpersonal communications in challenging contexts, such as with a vulnerable cohort of clients. These skills tend to be solely learnt on the job a dynamic that can come at substantial human cost. I rely on the practical application of the law to issues addressed in the 2013 High Court of Australia case of Bugmy v The Queen (‘Bugmy’) 1 In Bugmy, the High Court accepted that for the purposes of sentencing someone convicted of a crime, a court must consider their relevant history of disadvantage and deprivation when assessing their moral culpability.2 However to apply that principle, evidence must be put before the court regarding the offender’s relevant subjective circumstances, that is their background. Further, ‘[b]ecause the effects of profound childhood deprivation do not diminish with the passage of time and repeated offending, it is right to speak of giving “full weight” to an offender’s deprived background in every sentencing decision.’3 A background of deprivation does not need to be causally linked to the offence.4 Instead, in the sentencing exercise the weight of the evidence is a matter for individual assessment. Justice Simpson (as she then was) observed that as a matter of ‘[c]ommon sense and common humanity’ a person with a ‘tragic and dysfunctional’ upbringing ‘will have fewer emotional resources to guide his (or her) behavioural decisions’ than someone from an advantaged background.5 These elements of the Bugmy ruling are often referred to as ‘Bugmy principles’.

Bugmy is typically part of Australian law schools’ criminal law curriculum. Students learn that the Bugmy principles are particularly relevant to the lives of First Nations people. Typically, law students will be also exposed to Closing the Gap statistics that reveal the extreme disadvantage suffered

* Jill Hunter (BA LLB (UNSW), PhD (London)) is a Professor in the Faculty of Law & Justice, UNSW Sydney <https://www.unsw.edu.au/staff/jill-hunter>. Professor Hunter thanks the Australian Institute of Criminology and the Indigenous Justice Research Program for their generous support and funding of Jill Hunter, ‘A Case Study of New South Wales Sentencing Courts and First Nations Offenders A “Difficult Kind of Dance” with Bugmy v R’ (Research Report, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2025) (forthcoming), and for permitting a portion of the research to be included in Court of Conscience. She also thanks the reviewers of this article for their generosity in reviewing and enhancing this article.

1 (2013) 249 CLR 571 (‘Bugmy’).

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid 571 [44] (French CJ, Hayne, Crennan, Kiefel, Bell and Keane JJ) (emphasis added).

4 Ibid 591 [34].

5 R v Millwood [2012] NSWCCA 2 [69] (Simpson J).

by First Nations Australians.6 As Mick Gooda, former Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner observed, ‘[t]he high rate of imprisonment is occurring in the context of poor health, inadequate housing, high levels of family violence, and high levels of unemployment’.7 Overrepresentation in prisons continues and grows despite the Australian Law Reform Commission’s (ALRC) recommendations made in Pathways to Justice Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, 8 Closing the Gap strategies9 and the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (RCIADIC).10

However, generally speaking, law schools are unlikely to find room to teach students about the challenges that lawyers face when they seek to invoke Bugmy principles.11 Some law schools may include discussion of the Canadian case of R v Gladue12 in their criminal law curriculum. Typically, such a reference is to the remedial nature of the statute applied in that case. It is designed to ameliorate ‘the serious problem of overrepresentation of aboriginal people in prisons, and … encourage sentencing judges to have recourse to a restorative approach to sentencing’ 13 Gladue reports reflect the Canadian courts’ obligation to recognise that ‘[aboriginal] offenders’ lives show the consequences of colonialism … that have destroyed their culture and communities’…’.14 These reports ‘tell a shortened life story about the criminalised Indigenous person before the courts’,15 including relevant family, social, health and cultural profiling. They are composed following multiple interviews with the defendant, their family and community members so that courts are presented with evidence of the intergenerational impacts of colonialism and with recommendations, such as diversionary options. In the Australian context, Gladue’s case presents an aspirational goal.16

While Canadian lawyers and courts may be able to rely on Gladue reports, what do Australian lawyers do? How do they enliven the Bugmy principle of taking into account the impact of disadvantage, particularly childhood disadvantage? Unlike their Canadian equivalents, Australian sentencing courts cannot take judicial notice of the systemic background of deprivation and dispossession. A forthcoming

6 See Productivity Commission, ‘Closing the Gap Information Repository’, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Adults are Not Overrepresented in the Criminal Justice System (Web Page) <https://www.pc.gov.au/closing-the-gap-data/dashboard/se/outcome-area10>.

7 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner, Submission No 5 to Senate Finance and Public Administration References Committee, Parliament of Australia, Inquiry into Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Experience of Law Enforcement and Justice Services (27 April 2015) 5 (‘Submission No 5’), quoted in Australian Law Reform Commission, Pathways to Justice: Inquiry into the Incarceration Rate of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples (Report No 133, 1 December 2017) 41 [1.20] (‘Pathways to Justice’).

8 Pathways to Justice (n 7) 9.

9 National Indigenous Australians Agency, ‘National Agreement on Closing the Gap’, Closing the Gap (Web Page, July 2020) <https://www.closingthegap.gov.au/national-agreement/national-agreement-closing-the-gap>.

10 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (National Report, April 1991) vol 1.

11 Law schools vary. For example, at UNSW, the LLB and JD elective Sentencing and Criminal Justice prepares its law students in a number of the ways discussed in this article and Kingsford Legal Centre introduces its students to client interviewing.

12 (1999) 1 SCR 688 (‘Gladue’).

13 Ibid [93], referring to Criminal Code, RSC 1985, c C-46, s 718.2(e).

14 R v Willier [2016] ABQB 241 [6] (Greckol J).

15 Judah Oudshoorn, ‘Theorizing a Way Out of Reformist Reforms: Gladue Reports and Penal Abolition' (2024) 26(2) Punishment & Society 243, 245. See also Patricia Barkaskas et al, Production and Delivery of Gladue Pre-Sentence Reports: A Review of Selected Canadian Programs (Report, 9 October 2019) 50.

16 Yet, as the forthcoming report described in n 17 below indicates, Gladue reports can be highly problematic.

Australian Institute of Criminology (AIC) funded study17 draws on the in-court experiences of 20 lawyers, judicial officers and an Aboriginal support officer to better understand how Bugmy principles apply in practice. This study suggests that translating these principles into practice is often poorly managed. For example, a number of interviewees described observing lawyers making Bugmy submissions to a sentencing court but failing to include factual detail or evidentiary support.18 Instead they merely offer the judicial officer the ‘code’ words, ‘Bugmy principles apply’ or just ‘“Bugmy,” you know’. While lawyers who represent clients will be well-aware of the need to obtain instructions and gather appropriate evidence, the forthcoming empirical study shows that to the lawyer who speaks in code, for some reason, Bugmy principles are (apparently) disconnected from the details of their client’s situation. The inadequacy of giving a case name in the form of a code reveals how poorly legal education has prepared such a lawyer for the real world of representing a disadvantaged client.

I will explain why.

There is no automatic Bugmy discount for uttering a case name as if its mention is a ‘magical’ word. A court needs to be informed of an offender’s subjective case (that is, the factual basis of their disadvantage), and how these circumstances and experiences connect to the decisions for the court. Lawyers who rely solely on the Bugmy ‘code’ in their submissions to a sentencing court reveal that they have failed to absorb what the law expects of them and of the court. Case law, such as O'Hanlon v R19 can also illustrate this point. In O’Hanlon, in submissions based on Bugmy’s case, the applicant’s solicitor failed to place any substantive evidence regarding their client’s subjective case.20 The Court of Criminal Appeal repaired the damage but, appropriately, its focus was on responding to legal issues rather than the broader dynamic of why such failures occur.

The forthcoming AIC-funded study explores the dynamics that offer some explanations for these failures.21 The study shows that it can be difficult for lawyers obtaining such sensitive information from their client because disadvantage intersects in complicated ways on the clientele of Aboriginal legal services and legal aid agencies. For example, one lawyer interviewee represented an Indigenous man who suffered from the consequences of Foetal Alcohol Syndrome Disorder (FASD). He grew up on a mission where the community and his own home were burdened by excessive alcohol use, abuse and violence. Illicit drugs were involved in his offending. The client’s cognitive disability and experience of domestic violence created layers of complexity. During the interview, the lawyer reflected on the impact of disadvantage on this person’s life, observing that it showed ‘a really common sort of schematic that you find, which is [first] the early exposure to violence; the drug use starts…; the

17 Jill Hunter, ‘A Case Study of New South Wales Sentencing Courts and First Nations Offenders A “Difficult Kind of Dance” with Bugmy v R’ (Research Report, Australian Institute of Criminology, 2025) (forthcoming), This research was funded by the Australian Institute of Criminology and the Indigenous Justice Research Program and supported by the UNSW Faculty of Law & Justice and Centre for Criminology, Law & Justice. Research ethics approval for this project was granted by the UNSW Human Ethics Research Committee A (HC230240).

18 Interviewees are de-identified, with ‘ALS’ representing an Aboriginal Legal Service (NSW/ACT) solicitor and ‘LA’ representing Legal Aid (NSW).

19 [2025] NSWCCA 118 (‘O’Hanlon’).

20 Ibid [22], [36].

21 See Hunter (n 17) 5.

homelessness and it all sort of mingles into one and helps to explain how that person got there’ 22 He further explained:

[B]ut where do the drugs come from? Why is this person using ice every day? Well, they're using ice every day, because for the past three years they've been homeless, and they've been homeless … because you know they've never been able to hold down stable accommodation or a job. Why? Well, because they left school in the equivalent of Year 7, because they were constantly in and out of school, for fighting, for stealing. They were getting locked up. Why was that happening? Oh, because they grew up on a mission where there was rampant alcohol and domestic violence. And I will contend that he was basically predisposed to this life path.23

A lawyer, particularly a non-Indigenous lawyer, obtaining this level of factual detail and such insight must meet a number of challenges. They are interviewing a client who is struggling with life.24 The topics are sensitive. The lawyer is likely to be untrained in appropriate interview techniques. They may be juggling numerous files. Nor is there a single best-practice approach.25 As one interviewed lawyer noted, ‘a lot of stuff is private, personal’26, and clients’ attitudes vary as ‘some people feel terrible remorse for terrible things they do. And other people simply don't. It's a wide range, wide range of levels of engagement …’.27 ‘Having [First Nations clients] share their experiences takes time, takes resources that we don't often have. It takes a connection to community [and] that takes years … ’.28 Other issues, such as gender, may also create barriers.29

Even if these hurdles are overcome the lawyer needs to know how to best present in court potentially traumatising evidence. For example, it is clearly difficult for lawyers to address how courts should receive evidence of a client’s exposure as a child to domestic violence or to a home life marked by rampant alcohol-fuelled violence. In particular, a client may prefer that their private and personal matters not be ventilated to strangers or in front of their family sitting in court. In the AIC-funded study some clients instruct their legal representative to avoid submissions placing family members in a poor light ‘because on release they're going back to the Aunty that raised them, or the mum and dad or the community in general and they would rather spend more time in custody than have them…badmouthed’ 30 As one interviewee noted, the best ‘lawyer’s’ outcome may not meet a client’s wishes.31

Dealing with these situations is rarely, if ever, taught in law school. Even if it is, this is not just an exercise in legal processes. It is a public process, in a courtroom that has scale, furnishings and personnel that are incongruous with communicating the personal traumas that are intrinsically raw and intimate and potentially expose a client to shame and humiliation. Two Canadian studies describe the

22 Ibid ALS5, see (n 18).

23 Ibid

24 See further Natalie Gately et al, ‘Complex Lives and Procedural Barriers: Detainees’ “Life Happens” Explanations for Breaching Orders’ (2025) 58(2) Journal of Criminology 299.

25 See Hunter (n 17).

26 Ibid ALS6.

27 Ibid ALS4.

28 Ibid LA1.

29 See, eg, R v Kina [1993] QCA 480.

30 Hunter (n 17) LA1.

31 Ibid.

challenges of in-court engagement with a client’s traumatic experiences. They note that ‘it was often difficult to bring up accused persons’ background information from their Gladue Reports in court, as they may not “want the painful details of their life raised in a forum”’.32

To teach such matters at law school is even more challenging, especially as the coverage of complex legal doctrine squeezes out many of the soft skills of being a lawyer. Galloway and Jones, addressing another context, refer to the need to ‘shift from the adversarial individualistic doctrinal focus of the traditional law degree, to embracing … the “soft” skills called for in the “real” world of work’.33

Finally, even if the court is appropriately provided with specific evidence of subjective disadvantage, the lawyer’s task is not complete. They must inform the sentencing court of the significance of that disadvantage whether it be FASD, homelessness, domestic violence, child abuse or neglect.34 While law schools teach students about obtaining expert evidence, often there will not be funds for an expert, and so lawyers need to learn how to use multi-disciplinary research-based resources like those in the Bugmy Bar Book.35 This resource provides courts and a potential expert with ‘a considerable quantity of social research relevant to various forms of disadvantage and deprivation [that is] undoubtedly a useful compilation of material relevant to understanding the effects of social disadvantage and deprivation’.36 Some law schools, like those at the University of New South Wales and the University of Technology, Sydney, draw some students into the Bugmy Bar Book project but as the AIC-funded study shows, more is required to be a lawyer skilled in presenting strong Bugmyinformed submissions to a real-world court.

The personal consequences of courts failing to make properly informed sentencing determinations are immense. Hench, while it is crucial that law students appreciate the systemic causes of First Nations Australians’ appalling incarceration rates37 and the close relationship between socioeconomic disadvantage and criminal justice involvement,38 more is required of future lawyers. For courts to be well-informed of an offender’s situation and for lawyers to best support a non-custodial sentence, all concerned must have the capacity to appreciate the exceptional complexity created by disadvantage and deprivation particularly in the context of settler/colonial dispossession. Lawyers

32 Department of Justice Research and Statistics Division, ‘Spotlight on Gladue: Challenges, Experiences, and Possibilities in Canada’s Criminal Justice System’ (Research Paper, September 2017) 51, quoting Scott Clark ‘Evaluation of the Gladue Court’ (Research Report, 2016); see also Anna Ndegwa et al, ‘Applying R v Gladue: The Use of Gladue Reports and Principles’ (Research Report, 2023).

33 Kate Galloway and Peter Jones, ‘Guarding Our Identities: The Dilemma of Transformation in the Legal Academy’ (2014) 14(1) QUT Law Review 15.

34 For a comprehensive list of disadvantages, see the Bugmy Bar Book Project Committee, ‘Bugmy Bar Book’, (Web Page, 2019) <https://bugmybarbook.org.au/>.

35 See ibid. The Bugmy Bar Book relies on Evidence Act 1995 (NSW) s 144.

36 Baines v R [2023] NSWCCA 302 [83] (Simpson J).

37 See generally Jennifer Tsui et al, ’Incarceration in Australia Since 1967: Trends in the Over-Representation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples’ (Research Paper, September 2022).

38 For a persuasive examination conceptualising criminalisation and incarceration within the frameworks of social determinates of justice and social determinates of health, see Ruth McCausland and Eileen Baldry, ‘Who Does Australia Lock Up? The Social Determinants of Justice’ (2023) 12(3) International Journal for Crime, Justice and Social Democracy 37, 53.

must build trust and rapport, enabling them to appropriately present the ‘life path’ of the person before the court.

It should be an aspiration for all Australian law schools to expose law students to the practical ways in which they, as lawyers, can ensure that all courts, every day, present the best version of the High Court’s articulation of individualised justice. This is one that recognises and seeks to respond to the social determinants of justice ‘poor health, inadequate housing, high levels of family violence, and high levels of unemployment’.39

39 See Submission No 5 (n 7).

HELEN GIBBON* AND BEN MOSTYN#

Australian law students are introduced early in their criminal law studies to the High Court’s landmark decision in He Kaw Teh v The Queen, 1 a leading authority on interpreting statutory offences. Students learn that the common law has long recognised a presumption in favour of subjective mens rea the principle that a guilty mind must be proven before a person may be convicted of a criminal offence.2 The High Court affirmed that, where a statute is silent on the mental element, courts should presume that Parliament did not intend to punish people who unknowingly engaged in prohibited conduct. This presumption may be rebutted by consideration of the purpose of the statute and an analysis of specific factors, including the nature and seriousness of the offence. In the context of Australian drug offences, He Kaw Teh established that the prosecution must prove, beyond reasonable doubt, that the accused knew or believed they were importing or possessing a prohibited substance. The mere presence of illicit drugs concealed in a traveller’s luggage is insufficient in itself to ground a conviction. This decision marked a significant departure in the interpretation of drug offences from earlier Australian case law.3

Concerns were raised at the time that requiring proof of knowledge would operate as a ‘drug pedlar’s charter’ by imposing an impossibly high bar for the prosecution to establish guilt, and thereby undermine the efficacy of drug law enforcement.4 Sympathy for this apprehension was echoed in the dissenting judgment of Wilson J in He Kaw Teh, who stated, ‘[o]ne cannot lightly dismiss the view … that an offence of absolute liability may be justified by the difficulties that any other conclusion would place in the way of law enforcement officers … in making out a prima facie case’.5

Ultimately, Wilson J preferred to interpret the offences as ones of strict liability, where the accused would be convicted unless they could show an honest and reasonable belief, albeit mistaken, that they were not committing an offence. This construction, he believed, balanced fairness to the

* Associate Professor Helen Gibbon is the Associate Dean (Education) at the Faculty of Law & Justice, UNSW Sydney. She is the co-founder of the UNSW elective LAWS3427 | JURD7527 Drug Law and Policy.

# Dr Ben Mostyn is a Lecturer at Sydney Law School, University of Sydney. He is the co-founder of the UNSW elective LAWS3427 | JURD7527 Drug Law and Policy.

1 (1985) 157 CLR 523 (‘He Kaw Teh’).

2 Sherras v De Rutzen [1895] 1 QB 918, 921, cited in He Kaw Teh (n 1) 528 (Gibbs CJ).

3 See, eg, R v Ditroia and Tucci (1981) VR 247; R v Gardiner [1981] Qd R 394; R v Parsons [1983] 2 VR 499.

4 See discussion in He Kaw Teh (n 1) 580 (Brennan J).

5 He Kaw Teh (n 1) 557 [39] (Wilson J).

accused and ‘the protection of the community from the monstrous evils of the international traffic in heroin and other drugs which are intrinsically nefarious’.6

While He Kaw Teh was heralded as a win for fundamental principles of the criminal law, including that the prosecution bears the burden of proving that the accused performed a guilty act with a guilty mind, statutory doctrines in the Drug Misuse and Trafficking Act 1985 (NSW) (‘DMTA’) demonstrate that the balance between the competing considerations identified by Wilson J is not tipped towards fairness to the accused. Deeming provisions, reverse burdens, and extended definitions (and their broad interpretation by the courts) instead assist law enforcement in the global War on Drugs, creating ‘legal fictions’ that erode these fundamental principles.

It is not the role of practitioners defending individual clients on drug charges to make grand rhetorical statements about the history and broader context in which drug laws operate. However, it is important that law students learn that blackletter law does not exist in a vacuum. Criminal law education should go beyond teaching not only what the law is. As future law reformers, it must also encourage students to question what the law ought to be.

The broad definitions of ‘supply’, ‘cultivation’, and ‘manufacture’ in the DMTA significantly expand the scope of prohibited conduct beyond what is required to establish criminal liability for those offences simpliciter. For example, the offence of supplying a prohibited drug is complete upon the mere ‘offer to supply’; neither actual supply nor intent to supply need be proven.7 Deeming provisions further extend this reach, capturing conduct that might otherwise constitute an attempt or lesser offence. The ‘deemed supply’ provision presumes that a person found in possession of a specified quantity of a prohibited drug is a supplier, thereby reversing the burden of proof: the prosecution need not establish intent to supply, the accused must prove its absence.8 The ‘deemed drug’ provision goes even further, deeming a non-prohibited substance to be a prohibited substance if it is falsely represented as such for the purpose of supply.9 The offence is complete upon the misrepresentation regardless of the accused’s intent or capacity to acquire and supply a prohibited drug.

Our system of parliamentary sovereignty means that these statutory doctrines which create legal fictions and erode fundamental common law principles are rarely noted as exceptional by the courts. Indeed, recent decisions of the NSW Court of Criminal Appeal (‘CCA’) suggest a judicial willingness to interpret drug laws expansively, arguably beyond the original legislative intent and beyond what is necessary by way of principles of statutory construction. This article does not seek to

6 Ibid.

7 Drug Misuse and Trafficking Act 1985 (NSW) s 3 (‘DMTA’).

8 Ibid s 29.

9 Ibid s 40.

canvass all such provisions in the DMTA, but rather to examine two CCA decisions R v Bucic10 and Jenkinson v R11 to illustrate how the practice of law is shaped by broader political and social forces.